Abstract

Background

Multiple studies have shown that dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccines can induce antitumor immunity. Previously, we reported that gemcitabine enhances the efficacy of DC vaccination in a mouse model of pancreatic carcinoma. The present study aimed at investigating the influence of gemcitabine on vaccine-induced anti-tumoral immune responses in a syngeneic pancreatic cancer model.

Materials and methods

Subcutaneous or orthotopic pancreatic tumors were induced in C57BL/6 mice using Panc02 cells expressing the model antigen OVA. Bone marrow-derived DC were loaded with soluble OVA protein (OVA-DC). Animals received gemcitabine twice weekly. OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells and antibody titers were monitored by FACS analysis and ELISA, respectively.

Results

Gemcitabine enhanced clinical efficacy of the OVA-DC vaccine. Interestingly, gemcitabine significantly suppressed the vaccine-induced frequency of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells and antibody titers. DC migration to draining lymph nodes and antigen cross-presentation were unaffected. Despite reduced numbers of tumor-reactive T-cells in peripheral blood, in vivo cytotoxicity assays revealed that cytotoxic T-cell (CTL)-mediated killing was preserved. In vitro assays revealed sensitization of tumor cells to CTL-mediated lysis by gemcitabine. In addition, gemcitabine facilitated recruitment of CD8+ T-cells into tumors in DC-vaccinated mice. T- and B-cell suppression by gemcitabine could be avoided by starting chemotherapy after two cycles of DC vaccination.

Conclusions

Gemcitabine enhances therapeutic efficacy of DC vaccination despite its negative influence on vaccine-induced T-cell proliferation. Quantitative analysis of tumor-reactive T-cells in peripheral blood may thus not predict vaccination success in the setting of concomitant chemotherapy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-013-1510-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Vaccination, Dendritic cells, Pancreatic carcinoma, Chemotherapy, Gemcitabine, Survival

Introduction

Chemotherapy with gemcitabine is currently considered standard treatment for patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma, yet resulting in an only moderate increase in survival time compared to 5-fluorouracil treatment [1]. Phase-III trials using gemcitabine in combination with other chemotherapeutic drugs have shown only limited additional benefits [2]. Recently, a combination therapy using oxaliplatin, irinotecan, fluorouracil and leucovorin (FOLFIRINOX) was shown to be superior to gemcitabine in patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. However, therapy was associated with a high incidence of side effects, limiting its use to patients with excellent performance status [3].

There is a need for novel strategies for the treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, such as immunotherapy. It has been shown that tumor infiltration with CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells (CTL) and CD4+ T helper (Th) cells represent independent favorable prognostic factors for patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma [4]. Furthermore, functional tumor-reactive T-cells capable of tumor rejection in vitro and in vivo have been isolated from the blood of pancreatic carcinoma patients [5]. These tumor-reactive T-cell responses can be enhanced by vaccination with tumor antigen-loaded dendritic cells (DCs) [6]. DC vaccination has been shown to induce tumor regression in some cancer patients [7]. Recently, we have shown that antitumor immune responses induced by DC vaccination correlated with better clinical outcome in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer [6].

However, tumor escape mechanisms can render cancer cells insensitive toward CTL-mediated lysis. Combination with other treatment strategies, such as irradiation or chemotherapy, may decrease immune resistance of cancer cells [8]. Our group demonstrated that combination of DC vaccination with gemcitabine increased survival in a murine pancreatic carcinoma model [9]. Gemcitabine has been demonstrated to augment efficacy of other therapeutic strategies such as in vivo CD40 activation [10–12]. Novak et al. [13] were able to show that gemcitabine increases antigen uptake from apoptotic tumor cells by local DCs. Suzuki et al. [14, 15] demonstrated that a population of CD11b+Gr-1+ cells with immune suppressive characteristics, termed myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), is selectively reduced by gemcitabine. These findings indicate that gemcitabine-based chemotherapy may synergize with immunotherapy under certain circumstances.

Little is known about the immunological interplay of DC vaccination and chemotherapy. In this study, we aimed at investigating the influence of gemcitabine on immune responses induced by DC vaccination in a syngeneic pancreatic carcinoma model and to correlate these findings with therapeutic outcome. Furthermore, we aimed to investigate specific treatment variables such as the mode of vaccine application and timing of chemotherapy administration. The purpose of these studies was to facilitate the development of future clinical trials investigating the role of DC vaccination in the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female 8–10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Borchen, Germany). Animal studies were approved by the local regulatory agency (Regierung von Oberbayern, Munich, Germany). OT-1 mice were kindly provided by Prof. Thomas Brocker (Department of Immunology, University of Munich, Germany). CD8+ T-cells of transgenic OT-1 mice possess a T-cell receptor specific for the ovalbumin (OVA) epitope SIINFEKL presented on MHC-I haplotype H2-Kb [16, 17].

Cell lines

The murine pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line Panc02 is derived from a 3-methylcholanthrene-induced tumor in a C57BL/6 female mouse [18, 19]. Panc02 cells expressing the model antigen Ovalbumin (PancOVA) were generated as described and selected in media containing G418 (Sigma, Hamburg, Germany) [20]. Original and OVA-transfected cell lines showed identical growth kinetics.

Peptides

H2-Kb-restricted peptides were synthesized by Jerini Peptide Technologies (Berlin, Germany) according to data from the literature: OVA257-264 with peptide sequence SIINFEKL [21], TRP2181-188 with sequence VYDFFVWL [22] and p15E604-611 with sequence KSPWFTTL [23]. The p15E protein is part of the murine leukemia virus (MuLV) envelope protein that is expressed by Panc02 and thus represents a tumor-associated antigen. The tyrosinase-related-protein-2 (TRP2) epitope was used as negative control peptide for T-cell stimulation assays.

Reagents

Fluorochrome-labeled antibodies against CD11b (clone M1/70), CD11c (clone HL3), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD86 (clone B7-2), Gr-1 (clone RB6-85C) and NK1.1 (clone PK136) were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-CD25 (clone PC61.5) and anti-foxp3 (clone FJK-16s) were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Antibodies against IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2) were purchased from Caltag (Burlingame, CA, USA). Gemcitabine (Gemzar) was purchased from Lilly (Indianapolis, Indiana). Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-4 (IL-4) were purchased from PeproTech (London, UK). LPS, OVA protein and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany).

Generation and antigen-loading of bone marrow-derived DCs

Bone marrow-derived DCs were prepared as described [24]. Immature DCs were loaded with 1 mg/mL OVA protein. After stimulation with 300 ng/ml LPS, cells were harvested. Percentage and maturation status of DCs were examined by flow cytometry.

Tumor inoculation, monitoring of tumor growth and therapy

For subcutaneous tumor cell inoculation, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (Abbott, Illinois, USA) and 106 PancOVA cells resuspended in a volume of 100 μl PBS were injected into the flank. Tumor growth was determined by caliper. Mice were killed when tumor size exceeded 150 mm2. For orthotopic tumor induction, mice were anesthetized and the left flank was opened under sterile conditions. The spleen was mobilized to access the pancreas. A total of 2 × 105 PancOVA cells were injected in a volume of 20 μl PBS into the pancreas. Peritoneum and skin were occluded using sutures. For experiments in tumor-free mice, gemcitabine doses of 25, 50 or 75 mg/kg body weight were used as indicated. Gemcitabine was administered intraperitoneally twice weekly (at days 2 and 5 after DC vaccination) at a dose of 50 mg/kg for subcutaneous tumor experiments or 75 mg/kg body weight for orthotopic tumor experiments.

Isolation of immune cell populations

Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Subcutaneous tumors, tumor-draining inguinal lymph nodes and spleens were removed for further ex vivo analysis. Tumors were dissected using razor blades and digested with 1.5 mg/ml collagenase D and 50 U/ml DNAse (both from Roche) for 1 h at 37 °C.

Intracellular IFN-γ staining and MHC-I pentamer staining

Splenocytes or blood leukocytes were plated in 96-well plates. Samples were stimulated with SIINFEKL, p15E or TRP2 peptide (negative control). Four hours after incubation at 37 °C, 0.1 μg/ml brefeldin A was added to the samples. Four h later, plates were washed and cells were stained with anti-CD8 mAb, then with anti-IFN-γ after permeabilization with 0.5 % saponin for 15 min. The percentage of CD8+ T-cells expressing IFN-γ was determined by flow cytometry. Staining with Pro5-OVA257-264-H2-Kb-PE pentamer was performed for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. After washing, cells were stained with anti-CD8 mAb and the percentage of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Becton–Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Detection of OVA-specific antibodies by ELISA

Ninety-six-well plates were coated overnight with 10 μg/mL OVA in PBS and blocked 1 h with 1 % BSA in PBS. After incubation of serum samples for 1 h, plates were washed with PBS/Tween 20 and goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, or IgG2a, conjugated to horse-radish peroxidase (HRP, Southern Biotechnology Laboratories, Birmingham, AL, USA), was added at 1 μg/mL for 1 h. Plates were washed again and the assay was developed by o-phenylenediamine (Sigma-Aldrich). Reaction was stopped by addition of 1 M H2SO4 and optical density (OD) was measured. Measurements were performed in triplicates.

In vivo cytotoxicity assay

Splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were divided into two populations and loaded with either 2 μg/ml SIINFEKL peptide for one h at 37 °C or no peptide. Cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) at a concentration of 2 μM for peptide-pulsed cells and 0.2 μM for unpulsed cells. After extensive washing, both populations were mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and 107 cells were injected via the tail vein. 20 h after injection, spleen and inguinal lymph nodes were removed and analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of CFSEhigh versus CFSElow cells. Specific lysis in vaccinated mice was calculated:

OT-1 in vivo proliferation assay

Spleen and lymph nodes of OT-1 mice were removed, pooled into a single-cell suspension and labeled with 5 μM CFSE in PBS/0.01 % BSA for 20 min. One week after i.p. OVA-DC vaccination, 107 CFSE-labeled OT-1 cells were injected i.v. in a volume of 100 μl PBS. Seven days after adoptive transfer, proliferation of CFSE-labeled CD8+ OT-1 cells was determined by flow cytometry.

51Chromium-release cytotoxicity assay

Panc02 or PancOVA cells were used as target cells. Tumor cells were incubated for 10 h in the absence or presence of 10 nM or 100 nM gemcitabine. Target cells were incubated with Na512CrO4 (Hartmann Analytic, Braunschweig, Germany) (100 μCi/106 target cells) at 37 °C for 1 h. Cells were washed three times and 5 × 103 target cells/well were cocultured with effector cells in 96-well round-bottomed plates in a volume of 200 μl in different ratios. After 4-h incubation at 37 °C, 50 μl of supernatant was harvested and radioactivity determined by a gamma counter (Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland). Samples were processed in triplicates. Maximum release was defined as the mean cpm released from triplicates of 5 × 103 cells incubated in medium containing 2.5 % Triton X (Sigma, Munich, Germany). Spontaneous release was defined as the mean cpm released from labeled target cells in the absence of effector cells. Specific lysis was calculated according to the formula: specific 51Cr release = {(cpm of sample − cpm of spontaneous release)/(cpm of maximum release − cpm of spontaneous release)} × 100 %.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test was applied to reveal significant differences. A value of P < 0.05 was accepted as the level of significance. Tumor growth kinetics was tested for differences in linear regression curves of tumor growth using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test model. Survival curves were analyzed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (version 5.0f, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

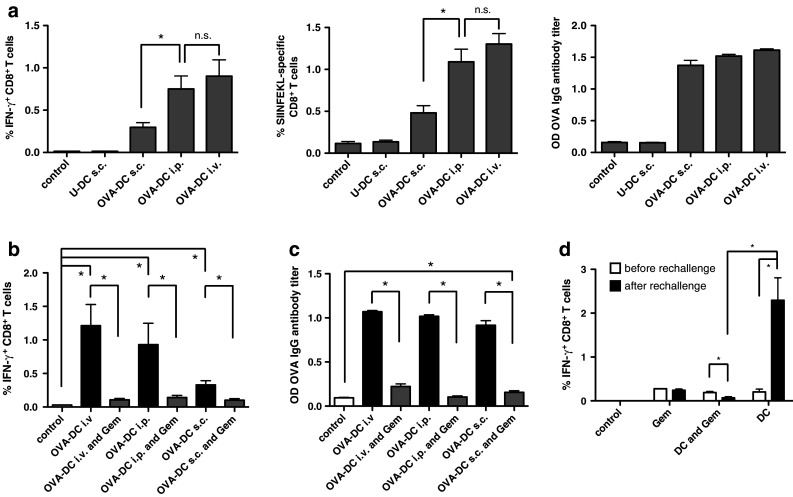

Gemcitabine suppresses DC vaccine-induced T- and B-cell responses

The induction of SIINFEKL-specific CD8+ T-cells in mice vaccinated with OVA-DC was analyzed by pentamer staining and IFN-γ ICS assay. Immune responses correlated significantly with the number of DCs administered (data not shown). Different vaccination routes were tested for their ability to mount an immune response (Fig. 1a). Intravenous (i.v.) and intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections were superior to subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of DCs in regards to CD8+ T-cell priming. For anti-OVA antibody responses, no significant differences were observed for all three vaccination routes. To study the effect of gemcitabine on DC-induced OVA-specific immune responses, mice were immunized two times in weekly intervals with 2 × 106 OVA-DC either s.c., i.p. or i.v. Animals received 75 mg/kg body weight gemcitabine i.p. at days 2 and 5 after DC vaccination. Gemcitabine significantly reduced the frequency of OVA-specific T-cells and antibody titers for all three vaccination routes (Fig. 1b, c). Dose reduction in gemcitabine to 25 mg/kg body weight per mouse did not diminish the level of immune suppression (Suppl. Fig. 1a-d, online resource). As the i.p. route for DC administration was more effective than the s.c. route, we decided to vaccinate mice i.p. in subsequent experiments.

Fig. 1.

Gemcitabine impairs OVA-DC vaccination-induced antigen-specific T- and B-cell responses. a Mice were vaccinated s.c., i.p. or i.v. with 2 × 106 OVA-DC two times in weekly intervals. Control mice were vaccinated s.c. with LPS-activated DCs that had not been loaded with OVA (U-DC). Immunomonitoring was performed 7 days after the second vaccination from peripheral blood by IFN-γ ICS (left) and pentamer staining (middle). Induction of Ag-specific B-cell responses was determined by anti-OVA antibody ELISA (right). Data represent one of the two independent experiments (n = 8 mice per group). *P < 0.05. b Mice were vaccinated twice by s.c., i.p. or i.v. OVA-DC injection in weekly intervals. Subgroups received gemcitabine i.p. twice weekly for a total of four times. The frequency of OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells was assessed by IFN-γ ICS. c OVA-specific B-cell responses after DC vaccination and concomitant gemcitabine treatment were analyzed by ELISA. Data represent one of the three independent experiments (n = 5 per group). d Mice having received OVA-DC vaccination 6 months earlier were split into three groups and rechallenged once with gemcitabine alone, OVA-DC with concomitant gemcitabine therapy or OVA-DC alone. Frequency of OVA-specific CTL was analyzed by IFN-γ ICS. The graph represents one of the two independent experiments (n = 3 per group)

To test the influence of gemcitabine on DC-induced recall T-cell responses in a vaccination setting, mice that had been vaccinated with OVA-DC 6 months earlier were tested for the presence of antigen-specific memory T-cells (Fig. 1d). Animals were divided into three groups with similar OVA-specific CD8+ T-cell frequencies. Two groups were re-vaccinated with OVA-DC. One of these two groups received concomitant gemcitabine therapy at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight. Mice of the group that was not re-vaccinated received gemcitabine alone. Immunomonitoring by IFN-γ ICS assay was performed 7 days after re-vaccination. A single re-vaccination with OVA-DC led to the induction of a profound T-cell response (2.29 ± 0.63 % compared to 0.21 ± 0.11 % before re-vaccination, P = 0.02). Gemcitabine significantly inhibited induction of a recall response. Gemcitabine alone had no influence on the frequency of antigen-specific T-cells. This finding indicates that gemcitabine might act particularly on T-cells during the proliferative phase of an ongoing immune response.

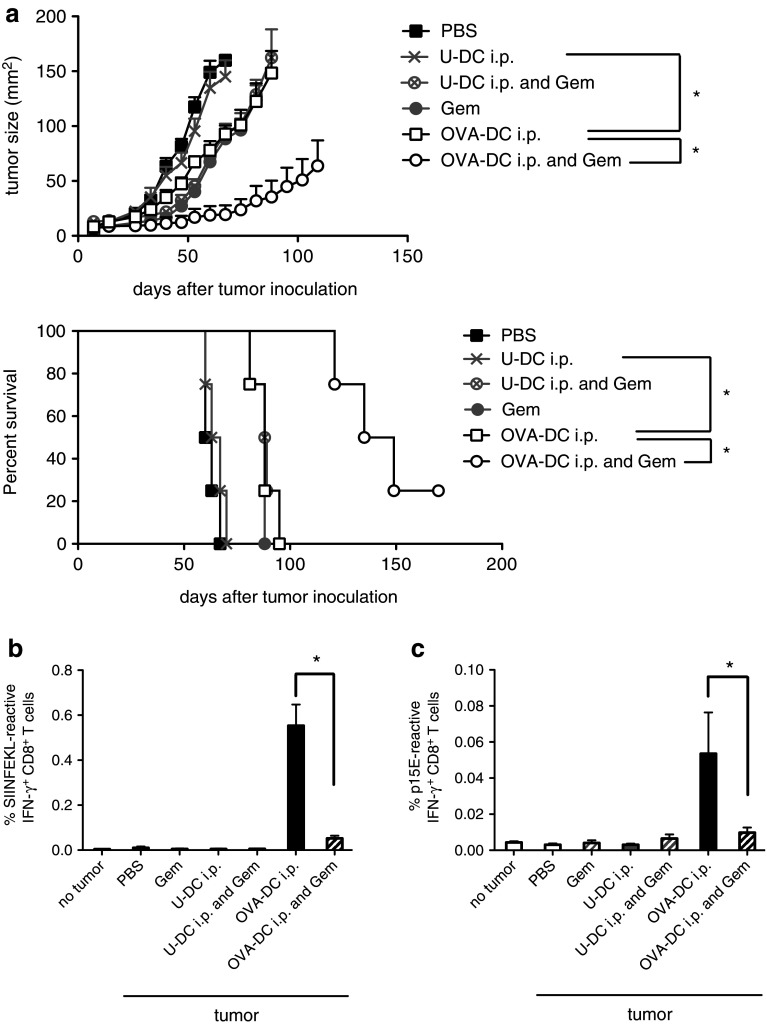

Characterization of DC vaccine-induced anti-tumoral immune responses in the subcutaneous PancOVA tumor model

Previously, we reported a synergistic therapeutic effect of combined gemcitabine and DC vaccination in the subcutaneous Panc02 model [9]. To characterize DC vaccine-induced immune responses against tumor-associated antigens, we injected Panc02 cells expressing the model antigen ovalbumin (PancOVA) into the flank of mice that received or did not receive OVA-DC starting 7 days after tumor inoculation. The frequencies of CD8+ T-cells specific for the OVA epitope SIINFEKL or a tumor-specific but vaccine-unrelated epitope, p15E, were measured in peripheral blood. As expected, mice of the OVA-DC plus gemcitabine group had a significantly better therapeutic outcome than mice in the groups receiving either OVA-DC or gemcitabine alone (Fig. 2a, P < 0.001, OVA-DC vs. OVA-DC and Gem). Vaccination with DCs that were not loaded with OVA showed no therapeutic efficacy, indicating that the vaccine response was antigen-specific in the OVA-DC group (P < 0.001, OVA-DC vs. U-DC). Survival analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model confirmed differences between U-DC- and OVA-DC-treated mice (P < 0.01) as well as between mice treated with OVA-DC alone and mice treated with OVA-DC and gemcitabine (P < 0.01). As previously observed, frequency of OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells was significantly lower in PancOVA tumor-bearing mice as compared to mice without tumors, indicative of tumor-induced immune suppression (Figs. 1, 2b) [20]. Ex vivo analysis found 0.55 ± 0.09 % OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells in mice that had received OVA-DC four times (on day 35 after tumor inoculation). Concomitant gemcitabine treatment led to a further reduction in OVA-specific CD8+ T-cells to 0.05 ± 0.01 % (P < 0.01 compared to OVA-DC alone).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of anti-tumor immune responses and treatment efficacy induced by gemcitabine-based chemoimmunotherapy in the subcutaneous PancOVA tumor model. a Therapy was started 1 week after induction of s.c. PancOVA tumors by administering either OVA-DC, LPS-activated unloaded DC (U-DC) or PBS with a total of six vaccinations. Subgroups received concomitant gemcitabine therapy on days 2 and 5 after DC injection. The graph depicts mean tumor burden in mm2 + SEM (top, n = 4 mice per group). Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrate treatment efficacy (bottom). Mice that had developed tumors >150 mm2 were killed. One of the two independent experiments with similar results is shown. b, c Tumor-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were assessed on day 35 after tumor inoculation by IFN-γ ICS after ex vivo stimulation with SIINFEKL or p15E peptide, respectively. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 4 per group)

Furthermore, stimulation of leukocytes with p15E peptide demonstrated the presence of p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cells in tumor-bearing mice treated with OVA-DC but not with gemcitabine alone (Fig. 2c). Again, concomitant gemcitabine treatment significantly suppressed the induction of p15E-specific CD8+ T-cells. Noteworthy, unloaded DC did not induce p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cells. The presence of p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cells found in OVA-DC-vaccinated animals indicates that DC vaccination is capable of not only inducing a T-cell response against vaccine-related antigens but also to unrelated tumor-associated antigens, a phenomenon termed “epitope-spreading.”

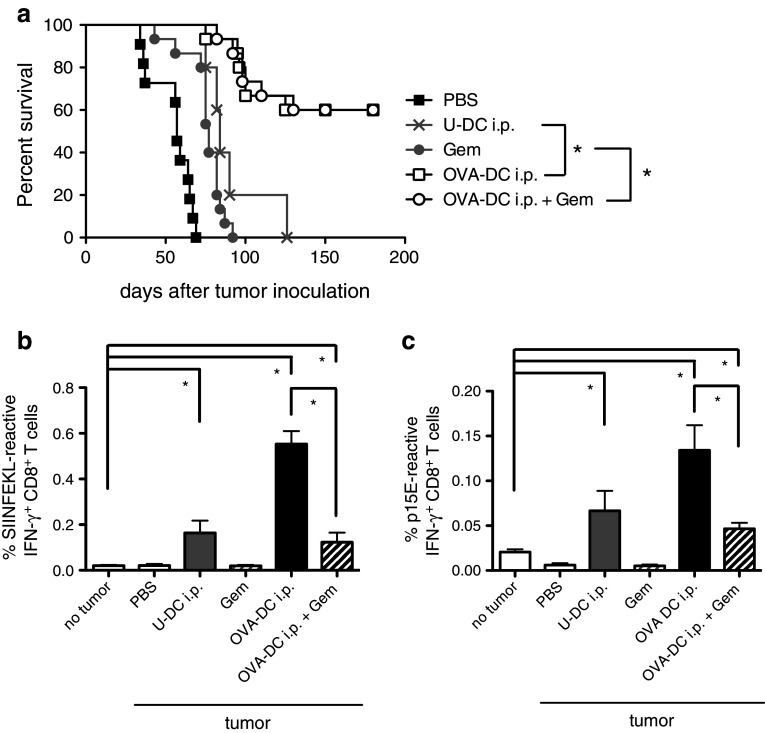

Efficacy of OVA-DC and gemcitabine in an orthotopic pancreatic cancer model

To assess the efficacy of our therapy regimen in a tumor model more closely resembling the biology found in humans, we used the orthotopic PancOVA model. Mice were implanted with orthotopic PancOVA tumors and treated with combinations of DC-OVA i.p. and/or gemcitabine. To control for vaccine antigen-unspecific immune effects induced by DC vaccination, a group of mice receiving unloaded DC (U-DC) and a group of mice receiving PBS sham injections were included (Fig. 3a). Untreated mice (PBS) had to be killed within 65 days due to progressive tumor burden. Gemcitabine treatment alone (Gem) improved survival (P < 0.001, Gem vs. PBS); however, the absolute effect on median survival was relatively small. Of note, treatment with U-DC also demonstrated a limited beneficial effect on survival (median survival 84 days, P < 0.001 compared to untreated mice). Mice treated with OVA-DC, however, showed highly efficient tumor control (P = 0.0015 compared to the U-DC group) with nine out of 13 mice rejecting their tumors leading to long-term survival beyond 150 days. Equally efficient tumor control was observed in the combined treatment group (P < 0.001, OVA-DC and Gem vs. Gem alone).

Fig. 3.

Treatment of mice with orthotopic PancOVA tumors with DC vaccination and gemcitabine prolongs survival despite reduced numbers of tumor-reactive CD8+ T-cells. a PancOVA tumors were implanted orthotopically in the pancreas. Treatment with gemcitabine, unloaded DC (U-DC), OVA-DC or OVA-DC + gemcitabine was started on day 7. Treatment efficacy is blotted as Kaplan–Meier survival curves. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (total of n = 15 mice in the OVA-DC and/or gemcitabine groups). b, c Frequencies of SIINFEKL- and p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cells were determined by IFN-γ ICS 35 days after tumor inoculation. Data are representative of two independent experiments (n = 7 per group). *P < 0.05

In the U-DC group, frequencies of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells were approximately 0.2 % for SIINFEKL and 0.05 % for p15E, which was significantly higher as in untreated mice (Fig. 3b, c). Thus, U-DC facilitated a tumor-specific CTL response, although at lower levels as compared to OVA-DC. OVA-DC led to development of 0.55 % SIINFEKL-reactive CD8+ T-cells, whereas concomitant gemcitabine reduced the frequency to 0.12 % (P < 0.001). Similarly, the frequency of p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cells was reduced by gemcitabine treatment.

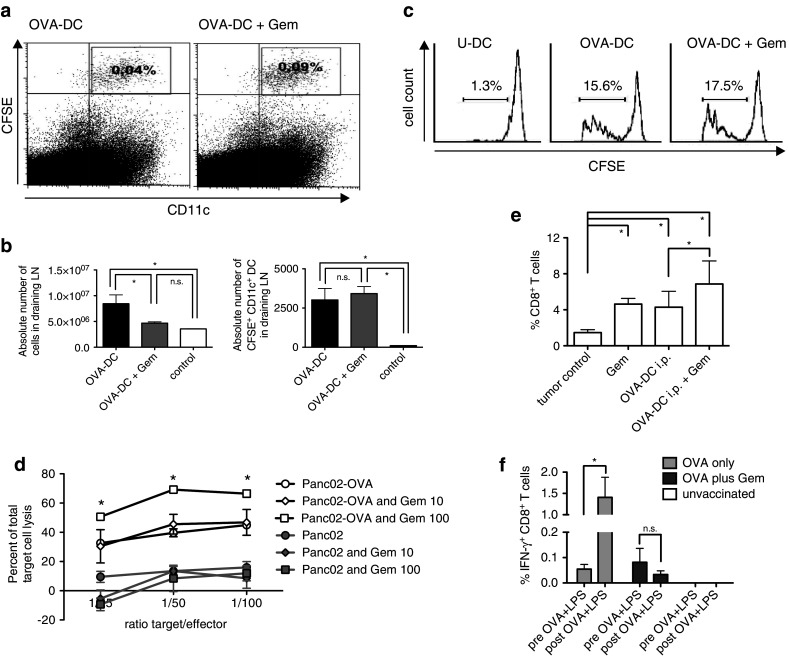

Gemcitabine does not impact DC function but sensitizes tumor cells toward CTL-mediated cytotoxicity

To assess the possibility that gemcitabine affects the function of DCs after injection in tumor-bearing hosts, we examined the influence of gemcitabine on DC migration to draining lymph nodes and antigen presentation in vivo (Fig. 4a–c). Migration and in vivo survival of DCs were tested by s.c. injection of 2 × 106 CFSE-labeled, OVA-DC into the foot pad of mice (n = 5 per group). At day 7, mice were killed and popliteal lymph nodes were analyzed. Interestingly, the frequency of CFSE+ CD11c+ CD11b+ cells was increased in mice treated with 50 mg/kg body weight gemcitabine (Fig. 4a). However, taking into consideration that the cellular content in the draining lymph node almost doubled in the OVA-DC group as compared to the combined group (Fig. 4b, left), gemcitabine treatment did not affect the absolute number of CFSE+ CD11c+ CD11b+ DCs in draining lymph nodes (Fig. 4b, right).

Fig. 4.

Gemcitabine does not impair DC function but sensitizes tumor cells to CTL-mediated killing. a Mice received s.c. injections of CFSE-labeled DCs into the foot pad and DC migration was assessed 7 days later in popliteal lymph nodes by flow cytometry. Representative FACS blots are shown. b Absolute numbers of total cells (left) and CFSE-labeled DCs that had migrated to draining lymph nodes (right) were determined in mice treated with PBS (control), OVA-DC or OVA-DC + Gem. c Mice were vaccinated with OVA-DC i.p. with or without concomitant gemcitabine administered at days 2 and 5. Control mice were vaccinated with unloaded DC (U-DC). CFSE-labeled OT-1 T-cells were adoptively transferred at day 7 and proliferation was analyzed 3 days later (n = 5 per group). d Gemcitabine increased sensitivity of PancOVA cells toward OVA-specific CTL-mediated lysis. PancOVA or Panc02 cells were treated with gemcitabine at concentrations of 10, 100 nM or left untreated and were co-cultured with OT-1 effector CTL. Tumor cell lysis was assessed in a chrome-release assay. Depicted is one of the four independent experiments performed as triplicates ± SEM. e Mice with s.c. PancOVA tumors were treated with four rounds of OVA-DC vaccination with or without Gem. Numbers of tumor infiltrating CD8+ T-cells were determined by flow cytometry (n = 4 per group). f After stratification according to frequency of OVA-reactive CD8+ T-cells in peripheral blood, pre-vaccinated mice (n = 3 per group) were rechallenged with 0.5 mg OVA protein and 1 μg LPS per mouse, given intravenously. Gemcitabine was administered 24 and 72 h after the rechallenge in respective subgroups. 48 h after the second gemcitabine administration, IFN-γ ICS was performed. *P < 0.05

Next, we tested the influence of gemcitabine on antigen presentation and T-cell stimulatory capacity of DCs in vivo by analyzing the proliferation of adoptively transferred CFSE-labeled CD8+ OT-1 T-cells in vaccinated mice (Fig. 4c). OT-1 T-cell proliferation was not affected by 50 mg/kg gemcitabine, indicating that antigen-presenting function, similar to DC migration to draining lymph nodes, was not negatively influenced.

The effect of gemcitabine on pancreatic carcinoma cells was assessed in regard to their sensitivity toward CTL-mediated lysis. Panc02 and PancOVA cells were treated with or without gemcitabine and lysis by OVA-specific CTL from OT-1 mice was studied in vitro using a 51Cr-release assay (Fig. 4d). At an E/T ratio of 100:1, we observed 45 ± 2 % specific lysis as compared to only 16 ± 4 % of Panc02 wild-type cells. Gemcitabine (100 nM) significantly sensitized PancOVA cells toward CTL-mediated lysis with a specific lysis reaching 66 ± 2 % (P < 0.001). Gemcitabine alone at a dose of 100 nM was below the cytotoxic threshold in this assay.

Gemcitabine facilitates recruitment of CD8+ T-cells to tumors, but inhibits DC-induced proliferative T-cell responses

To test whether gemcitabine alters tumor microenvironment in the PancOVA model, frequencies of various immune cell populations in spleen, draining lymph nodes and tumor tissue were analyzed. Interestingly, intratumoral infiltration with CD8+ T-cells (Fig. 4e), CD4+ T-cells and NK cells (Supp. Fig. 2a and 2b, online resource) was increased by DC vaccination as well as gemcitabine when compared to untreated control tumors. Of note, CD8+ T-cell infiltration was additively increased by concomitant DC-OVA and gemcitabine therapy (P = 0.03).

Absolute numbers of splenic B-cells, CD4+ T-cells and CD8+ T-cells were higher in tumor-bearing as compared to tumor-free mice (Supp. Fig. 2c). DC vaccination had no influence on splenic immune cell populations. However, splenic B-cells as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells were significantly reduced by gemcitabine as compared to untreated controls. Gemcitabine showed a trend to reduce CD11b+ Gr-1+ MDSC numbers in the spleen. The suppressive effect, however, was moderate and missed statistical significance. OVA-DC vaccination also reduced MDSC numbers, but again statistical significance was missed (Supp. Fig. 2d, P = 0.075). As previously reported [20], the frequency of Foxp3+ Treg cells among all CD4+ T-cells was significantly increased in spleens and tumor-draining lymph nodes of tumor-bearing mice (Supp. Fig. 2e and 2f). Neither DC vaccination nor gemcitabine had a significant influence on Treg frequency. No significant differences in the percentage of CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ T-cells or B-cells were observed between tumor-draining lymph nodes of tumor-free and tumor-bearing mice (Supp. Fig. 2 g).

Suppression of DC-induced T-cell responses by gemcitabine was further investigated by testing the influence of gemcitabine on T-cell recall responses (Fig. 4f) to eliminate potential influences of gemcitabine on OVA-DC. Similar to the experimental setup shown in Fig. 1d, mice that had been vaccinated with OVA-DC 6 months earlier were stratified into subgroups according to the frequency of OVA-reactive CD8+ T-cells in peripheral blood (0.055 ± 0.019 vs. 0.082 ± 0.058 % IFN-γ+ CD8+ T-cells). Mice were i.v. rechallenged with OVA protein and LPS. 24 and 72 h after the rechallenge gemcitabine at 50 mg/kg body weight was administered or not. Two days after, the second gemcitabine dose IFN-γ ICS was performed. Single re-vaccination induced a significant boost in the T-cell response (P = 0.046). Similar to the suppressive effect demonstrated in Fig. 1d, gemcitabine inhibited induction of a recall response, indicative of a detrimental effect on proliferating T-cells.

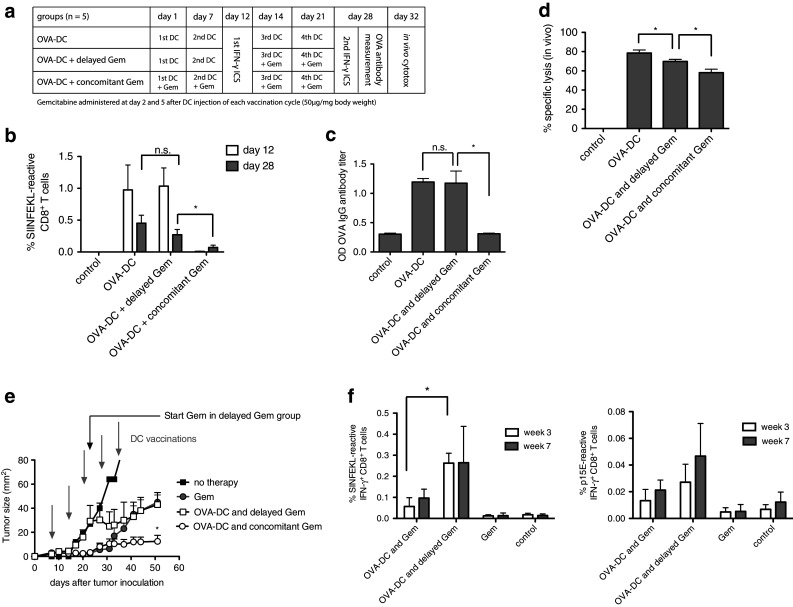

Timing of gemcitabine chemotherapy determines efficacy of DC vaccination

As T-cells are vulnerable toward chemotherapeutic drugs mainly in the exponential phase of proliferation, we hypothesized that modification of the vaccination scheme with a delayed start of gemcitabine therapy could lead to improved immunological outcome. This hypothesis was first tested in mice without tumors. Gemcitabine at a dose of 50 mg/kg body weight was either combined with OVA-DC vaccination from the beginning (“concomitant Gem”) or started after two rounds of vaccination (“delayed Gem”). A control group received OVA-DC only. Treatment regimens are summarized in Fig. 5a. As observed before, “concomitant Gem” significantly suppressed vaccine-induced CD8+ T-cell and antibody responses (Fig. 5b, c). In contrast, no impairment of the vaccine-induced immune response was seen in the “delayed Gem” group. To test whether the “delayed Gem” strategy improved T-cell effector function, we assessed in vivo cytolytic activity using adoptively transferred peptide-loaded splenocytes as target cells (Fig. 5d). Mice treated with OVA-DC showed highly efficient lysis of target cells, whereas concomitant gemcitabine impaired cytotoxic function, correlating with reduced numbers of antigen-specific CTL found in peripheral blood (Fig. 5b). Mice in the “delayed Gem” group exhibited significantly higher cytotoxic function compared to the “concomitant Gem” group (P = 0.02). These data indicate that delaying gemcitabine therapy to a time point when T-cell responses have already been established could be beneficial.

Fig. 5.

Delayed gemcitabine administration avoids chemotherapy-induced B- and T-cell suppression. a Treatment and immune monitoring scheme. OVA-DC-vaccinated mice were divided into three groups: OVA-DC with concomitant gemcitabine treatment (OVA-DC and concomitant Gem), delayed start of chemotherapy (OVA-DC and delayed Gem) and no chemotherapy (OVA-DC). b OVA-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were measured after the second DC vaccination (before the start of gemcitabine in “OVA-DC and delayed Gem” group) and at the end of the experimental protocol after four vaccinations by IFN-γ ICS assay. c Anti-OVA IgG antibody titers were assessed after four cycles of DC treatment. d In vivo OVA-specific CTL-mediated cytotoxicity was examined by measurement of target-cell lysis 20 h after adoptive transfer of CFSE-labeled, SIINFEKL-loaded splenocytes. e Mice were injected s.c. with 106 PancOVA cells and treated with Gem alone or OVA-DC ± Gem. Gray arrows indicate DC vaccinations; a black arrow indicates the start of gemcitabine therapy in the “OVA-DC and delayed Gem” group. f OVA- and p15E-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were determined before the start (white bars) and after the start of chemotherapy (gray bars) in the “OVA-DC and delayed Gem” group. Figure 4e, f represents one of two independent experiments (n = 7 per group)

Therapeutic outcome of “delayed Gem” was examined in the s.c. PancOVA model. As expected, gemcitabine concomitant to DC therapy led to better tumor control than gemcitabine alone (Fig. 5e). The difference between the two groups became evident 35 days after tumor induction, indicating that the DC-induced immune response required time to be beneficial. Mice receiving delayed gemcitabine treatment initially had quicker tumor progression than mice in the groups that had received gemcitabine from the beginning of the treatment. However, after three rounds of vaccination, tumor progression was stabilized. Measurement of SIINFEKL- and p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cell frequencies was performed 3 and 7 weeks after tumor inoculation (Fig. 5f). As observed in mice without tumors, SIIINFEKL-reactive and p15E-reactive CD8+ T-cell frequencies were higher in mice treated with OVA-DC and delayed gemcitabine when compared to mice receiving OVA-DC and gemcitabine concomitantly.

Discussion

Interplay of chemotherapy and immunotherapy has attracted much attention since the demonstration that certain chemotherapeutic regimens stimulate endogenous immune responses against tumors by triggering an immunogenic form of cancer cell death [25, 26]. Over the last years, data accumulated showing that effects of cytotoxic drugs are not limited to cancer cells, but also affect stromal cells and immune cells. Recently, Kang et al. [27] suggested that chemotherapeutic regimens can convert the tumor microenvironment into a highly permissive state for vaccination-induced antitumor immunity, demonstrating a role for DCs and CD8+ T-cells. Kim et al. [28] correlated therapeutic outcome with changes in the immunological microenvironment and T-cell responses in a colon cancer model. However, the influence of chemotherapy on DC vaccine-induced immunity in pancreatic cancer is poorly understood. Here, we show in a pancreatic cancer model that gemcitabine-based chemoimmunotherapy is feasible and highly effective, despite its apparent negative effect on DC vaccine-induced adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, we provide a mechanistic explanation for superior efficacy as compared to either treatment alone and propose a strategy for minimizing the suppressive effects of gemcitabine on vaccine-induced adaptive immune responses.

Gemcitabine has been the mainstay of pancreatic cancer therapy since the study of Burris et al. in the late 1990s [1]. For long, combination of a presumably immunosuppressive therapy like gemcitabine with an immunostimulatory one such as vaccination has been considered counter-intuitive. However, clinical studies demonstrated that gemcitabine can be administered to patients with pancreatic cancer without relevant loss of T-cell and DC function [12]. In fact, several studies have suggested an immunomodulatory function of gemcitabine. Gemcitabine was shown to inhibit Th2- and augment Th1-type immune responses in cancer patients, which is critical for an efficient CTL response [12]. Nowak et al. [13, 29] investigated effects of gemcitabine on immune responses induced by CD40 ligation in a murine model of combined chemoimmunotherapy, finding a mixed pattern of enhanced T-cell but suppressed B-cell responses. Furthermore, gemcitabine has been described to reduce the number of MDSC, a population of immature myeloid cells suppressing T-cell activation, in tumor-bearing animals [14, 15, 30, 31]. This is particularly interesting, as pancreatic cancer leads to MDSC expansion and accumulation in tumor tissue [32, 33]. However, others have found that gemcitabine can trigger cathepsin B release in MDSC thereby promoting tumor growth via activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome [34]. Ghansah et al. [35] recently found that gemcitabine specifically targets granulocytic MDSC. Reduced numbers of MDSC, however, were only associated with increased survival when gemcitabine therapy was combined with DC vaccination, indicating that the beneficial effects of gemcitabine might be at least in part immune-mediated. These data are concordant with our finding of superior tumor control with the combined treatment and preserved cytotoxicity despite chemotherapy-induced numerical suppression of the DC-induced T-cells. Our study also shows a trend toward reduced MDSC numbers by gemcitabine as well as DC vaccination; however, this was not statistically significant. Shevchenko et al.[36] found that low-dose gemcitabine depleted intratumoral Treg and improved survival in the Panc02 model. One explanation might be that Treg are particularly sensitive toward chemotherapy, including gemcitabine [37], possibly due to the higher turnover of these cells as compared to other CD4+ T-cell populations. Concordant with earlier findings [20, 38], we found an increased frequency of Treg in spleen and tumor-draining lymph nodes of PancOVA tumor-bearing mice. However, we could not detect a reduction in Treg frequencies in tumor-draining lymph nodes or spleens of mice treated with either gemcitabine and/or DCs. As numbers do not necessarily reflect Treg function, a more detailed analysis of Treg phenotype, such as CD103 expression, and suppressive activity should be addressed in further studies.

We have previously described efficacy of combining DC vaccination and gemcitabine in a murine pancreatic carcinoma model in regards to tumor control [9]. As immunological mechanisms leading to tumor control were not investigated due to the lack of a defined tumor antigen for immunomonitoring, we modified the tumor model by using OVA-expressing tumor cells. Data presented here indicate that in a setting of DC vaccination concomitant gemcitabine therapy suppresses induction of a vaccine-specific adaptive immune response. Similarly, the response against a vaccine-unrelated tumor antigen, the tumor cell epitope p15E, which was induced as a secondary effect of the vaccine termed “epitope-spreading,” was also suppressed. However, despite the numerical reduction in tumor antigen-specific CTL in peripheral blood, therapeutic efficacy of DC vaccination was improved by gemcitabine. A possible explanation could be more efficient recruitment of T-cells to the tumor site, as combined treatment resulted in increased numbers of intratumoral CD8+ T-cells. In addition, the immunosuppressive effect of gemcitabine was probably balanced by mechanisms augmenting efficacy of immunotherapy, such as sensitization of tumor cells to CTL-mediated lysis. In fact, CTL-mediated killing of target cells in vivo was only mildly impaired by gemcitabine treatment, indicating that lower numbers of tumor-reactive CD8+ T-cells were equally effective when administered under favorable conditions induced by chemotherapy. Our own group described increased cytotoxic activity of CTL when tumor cells were pretreated with gemcitabine [39]. This phenomenon, also termed chemosensitization, has been suggested to be mediated by upregulation of antigenic surface molecules on tumor cells [40, 41]. Recently, Takahara reported that gemcitabine enhances WT1 expression in pancreatic carcinoma cells thereby sensitizing these cells against WT1-specific T-cells [42]. In our study, we could confirm a CTL-sensitizing effect of gemcitabine on PancOVA cells, corroborating data from Ishizaki et al. [43].

An interesting finding of our study is that the negative impact of gemcitabine treatment on vaccine-induced adaptive immune responses can be influenced by the timing when chemotherapy is started. Once the DC vaccine had established an adaptive immune response, addition of gemcitabine in subsequent cycles did not negatively impact the numbers of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells or antibody titers. Concerning therapeutic outcome, an “OVA-DC and delayed Gem” strategy was non-inferior to gemcitabine treatment alone despite lower doses of Gem. Thus, in future clinical trials exploring the efficacy of DC vaccines, e.g., in an adjuvant setting after resection of the primary pancreatic tumor, vaccination should precede gemcitabine-based chemotherapy in order to facilitate the generation of an effective tumor-directed immune response and to control disease recurrence. On the other hand, in a palliative situation, concomitant therapy might be the better option to avoid tumor progression until the immune response has been established.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Christian Bauer, Franz Bauernfeind and Marc Dauer were supported by grants from the University of Munich (FoeFoLe No. 481, Promotionsstudium Molekulare Medizin, Gravenhorst-Stiftung) and the Saarland University (HOMFOR). Max Schnurr was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (Max Eder Research Grant) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SCHN 664/3-1, SCHN 664/3-2 and GK 1202). Transgenic OT-1 animals were kindly provided by Prof. Thomas Brocker (Department of Immunology, University of Munich, Germany).

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

Abbreviations

- CFSE

Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester

- CTL

Cytotoxic T-cell

- DC

Dendritic cell

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- FoxP3

Forkheadbox P3

- Gem

Gemcitabine

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- i.v.

Intravenous

- i.p.

Intraperitoneal

- ICS

Intracellular staining

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MHC-I

Major histocompatibility complex I

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- OD

Optical density

- OVA

Ovalbumine

- OVA-DC

OVA protein-loaded DC

- p15E

Retroviral protein expressed by Panc02 cells

- s.c.

Subcutaneous

- SIINFEKL

Immunodominant MHC-I epitope of the ovalbumine protein

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- Treg

Regulatory CD4+ Foxp3+ T-cell

- TRP2

Tryosinase-related peptide 2

- U-DC

Unloaded but LPS-stimulated DC

Footnotes

Christian Bauer and Alexander Sterzik, and Max Schnurr and Marc Dauer have contributed equally to this article.

This work is part of the doctoral thesis of Alexander Sterzik and Franz Bauernfeind at the University of Munich, Germany.

References

- 1.Burris HA, III, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, Cripps MC, Portenoy RK, Storniolo AM, Tarassoff P, Nelson R, Dorr FA, Stephens CD, Von Hoff DD. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(6):2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louvet C, Labianca R, Hammel P, Lledo G, Zampino MG, Andre T, Zaniboni A, Ducreux M, Aitini E, Taieb J, Faroux R, Lepere C, de Gramont A. Gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a GERCOR and GISCAD phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3509–3516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, Adenis A, Raoul JL, Gourgou-Bourgade S, de la Fouchardiere C, Bennouna J, Bachet JB, Khemissa-Akouz F, Pere-Verge D, Delbaldo C, Assenat E, Chauffert B, Michel P, Montoto-Grillot C, Ducreux M. Folfirinox versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukunaga A, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, Murakami S, Kawarada Y, Oshikiri T, Kato K, Kurokawa T, Suzuoki M, Nakakubo Y, Hiraoka K, Itoh T, Morikawa T, Okushiba S, Kondo S, Katoh H. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes together with CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and dendritic cells improve the prognosis of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2004;28(1):e26–e31. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200401000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Volk C, Z’Graggen K, Galindo L, Nummer D, Ziouta Y, Bucur M, Weitz J, Schirrmacher V, Buchler MW, Beckhove P. High frequencies of functional tumor-reactive t cells in bone marrow and blood of pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65(21):10079–10087. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer C, Dauer M, Saraj S, Schnurr M, Bauernfeind F, Sterzik A, Junkmann J, Jakl V, Kiefl R, Oduncu F, Emmerich B, Mayr D, Mussack T, Bruns C, Ruttinger D, Conrad C, Jauch KW, Endres S, Eigler A. Dendritic cell-based vaccination of patients with advanced pancreatic carcinoma: results of a pilot study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(8):1097–1107. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1023-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banchereau J, Palucka AK, Dhodapkar M, Burkeholder S, Taquet N, Rolland A, Taquet S, Coquery S, Wittkowski KM, Bhardwaj N, Pineiro L, Steinman R, Fay J. Immune and clinical responses in patients with metastatic melanoma to CD34(+) progenitor-derived dendritic cell vaccine. Cancer Res. 2001;61(17):6451–6458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correale P, Aquino A, Giuliani A, Pellegrini M, Micheli L, Cusi MG, Nencini C, Petrioli R, Prete SP, De Vecchis L, Turriziani M, Giorgi G, Bonmassar E, Francini G. Treatment of colon and breast carcinoma cells with 5-fluorouracil enhances expression of carcinoembryonic antigen and susceptibility to HLA-A(*)02.01 restricted, CEA-peptide-specific cytotoxic T cells in vitro. Int J Cancer. 2003;104(4):437–445. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer C, Bauernfeind F, Sterzik A, Orban M, Schnurr M, Lehr HA, Endres S, Eigler A, Dauer M. Dendritic cell-based vaccination combined with gemcitabine increases survival in a murine pancreatic carcinoma model. Gut. 2007;56(9):1275–1282. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.108621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou JM, Liu JY, Yang L, Zhao X, Tian L, Ding ZY, Wen YJ, Niu T, Xiao F, Lou YY, Tan GH, Deng HX, Li J, Yang JL, Mao YQ, Kan B, Wu Y, Li Q, Wei YQ. Combination of low-dose gemcitabine and recombinant quail vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 as a vaccine induces synergistic antitumor activities. Oncology. 2005;69(1):81–87. doi: 10.1159/000087303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nowak AK, Robinson BW, Lake RA. Synergy between chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of established murine solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(15):4490–4496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plate JM, Plate AE, Shott S, Bograd S, Harris JE. Effect of gemcitabine on immune cells in subjects with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54(9):915–925. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0638-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowak AK, Lake RA, Marzo AL, Scott B, Heath WR, Collins EJ, Frelinger JA, Robinson BW. Induction of tumor cell apoptosis in vivo increases tumor antigen cross-presentation, cross-priming rather than cross-tolerizing host tumor-specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(10):4905–4913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki E, Kapoor V, Jassar AS, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. Gemcitabine selectively eliminates splenic Gr-1+/CD11b+ myeloid suppressor cells in tumor-bearing animals and enhances antitumor immune activity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(18):6713–6721. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinha P, Clements VK, Bunt SK, Albelda SM, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells and macrophages subverts tumor immunity toward a type 2 response. J Immunol. 2007;179(2):977–983. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Bevan MJ. The ligand for positive selection of T lymphocytes in the thymus. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6(2):273–278. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC, Heath WR, Howard JL, Bevan MJ, Carbone FR. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corbett TH, Roberts BJ, Leopold WR, Peckham JC, Wilkoff LJ, Griswold DP, Jr, Schabel FM., Jr Induction and chemotherapeutic response of two transplantable ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas in C57Bl/6 mice. Cancer Res. 1984;44(2):717–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt T, Ziske C, Marten A, Endres S, Tiemann K, Schmitz V, Gorschluter M, Schneider C, Sauerbruch T, Schmidt-Wolf IG. Intratumoral immunization with tumor RNA-pulsed dendritic cells confers antitumor immunity in a C57bl/6 pancreatic murine tumor model. Cancer Res. 2003;63(24):8962–8967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs C, Duewell P, Heckelsmiller K, Wei J, Bauernfeind F, Ellermeier J, Kisser U, Bauer CA, Dauer M, Eigler A, Maraskovsky E, Endres S, Schnurr M. An ISCOM vaccine combined with a TLR9 agonist breaks immune evasion mediated by regulatory T cells in an orthotopic model of pancreatic carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(4):897–907. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotzschke O, Falk K, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Walden P, Rammensee HG. Exact prediction of a natural T cell epitope. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21(11):2891–2894. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloom MB, Perry-Lalley D, Robbins PF, Li Y, el-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA, Yang JC. Identification of tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J Exp Med. 1997;185(3):453–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JC, Perry-Lalley D. The envelope protein of an endogenous murine retrovirus is a tumor-associated T-cell antigen for multiple murine tumors. J Immunother. 2000;23(2):177–183. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heckelsmiller K, Beck S, Rall K, Sipos B, Schlamp A, Tuma E, Rothenfusser S, Endres S, Hartmann G. Combined dendritic cell- and CpG oligonucleotide-based immune therapy cures large murine tumors that resist chemotherapy. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(11):3235–3245. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3235::AID-IMMU3235>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins I, Tesniere A, Kepp O, Michaud M, Schlemmer F, Senovilla L, Seror C, Metivier D, Perfettini JL, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Chemotherapy induces ATP release from tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(22):3723–3728. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zitvogel L, Kepp O, Senovilla L, Menger L, Chaput N, Kroemer G. Immunogenic tumor cell death for optimal anticancer therapy: the calreticulin exposure pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3100–3104. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang TH, Mao CP, Lee SY, Chen A, Lee JH, Kim TW, Alvarez R, Roden RB, Pardoll DM, Hung CF, Wu TC. Chemotherapy acts as an adjuvant to convert the tumor microenvironment into a highly permissive state for vaccination-induced antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2013 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HS, Park HM, Park JS, Sohn HJ, Kim SG, Kim HJ, Oh ST, Kim TG. Dendritic cell vaccine in addition to FOLFIRI regimen improve antitumor effects through the inhibition of immunosuppressive cells in murine colorectal cancer model. Vaccine. 2010;28(49):7787–7796. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nowak AK, Robinson BW, Lake RA. Gemcitabine exerts a selective effect on the humoral immune response: implications for combination chemo-immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2002;62(8):2353–2358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le HK, Graham L, Cha E, Morales JK, Manjili MH, Bear HD. Gemcitabine directly inhibits myeloid derived suppressor cells in BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 mammary carcinoma and augments expansion of T cells from tumor-bearing mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9(7–8):900–909. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mundy-Bosse BL, Lesinski GB, Jaime-Ramirez AC, Benninger K, Khan M, Kuppusamy P, Guenterberg K, Kondadasula SV, Chaudhury AR, La Perle KM, Kreiner M, Young G, Guttridge DC, Carson WE., III Myeloid-derived suppressor cell inhibition of the IFN response in tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Res. 2011;71(15):5101–5110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark CE, Hingorani SR, Mick R, Combs C, Tuveson DA, Vonderheide RH. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67(19):9518–9527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Tumor-derived granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(6):822–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruchard M, Mignot G, Derangere V, Chalmin F, Chevriaux A, Vegran F, Boireau W, Simon B, Ryffel B, Connat JL, Kanellopoulos J, Martin F, Rebe C, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F. Chemotherapy-triggered cathepsin B release in myeloid-derived suppressor cells activates the Nlrp3 inflammasome and promotes tumor growth. Nat Med. 2013;19(1):57–64. doi: 10.1038/nm.2999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghansah T, Vohra N, Kinney K, Weber A, Kodumudi K, Springett G, Sarnaik AA, Pilon-Thomas S. Dendritic cell immunotherapy combined with gemcitabine chemotherapy enhances survival in a murine model of pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(6):1083–1091. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1407-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shevchenko I, Karakhanova S, Soltek S, Link J, Bayry J, Werner J, Umansky V, Bazhin AV. Low-dose gemcitabine depletes regulatory T cells and improves survival in the orthotopic Panc02 model of pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(1):98–107. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kan S, Hazama S, Maeda K, Inoue Y, Homma S, Koido S, Okamoto M, Oka M. Suppressive effects of cyclophosphamide and gemcitabine on regulatory T-cell induction in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(12):5363–5369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan MC, Goedegebuure PS, Belt BA, Flaherty B, Sankpal N, Gillanders WE, Eberlein TJ, Hsieh CS, Linehan DC. Disruption of CCR5-dependent homing of regulatory T cells inhibits tumor growth in a murine model of pancreatic cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182(3):1746–1755. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dauer M, Herten J, Bauer C, Renner F, Schad K, Schnurr M, Endres S, Eigler A. Chemosensitization of pancreatic carcinoma cells to enhance t cell-mediated cytotoxicity induced by tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. J Immunother. 2005;28(4):332–342. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000164038.41104.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelbard A, Garnett CT, Abrams SI, Patel V, Gutkind JS, Palena C, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Combination chemotherapy and radiation of human squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck augments CTL-mediated lysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(6):1897–1905. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gameiro SR, Caballero JA, Higgins JP, Apelian D, Hodge JW. Exploitation of differential homeostatic proliferation of T-cell subsets following chemotherapy to enhance the efficacy of vaccine-mediated antitumor responses. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(9):1227–1242. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahara A, Koido S, Ito M, Nagasaki E, Sagawa Y, Iwamoto T, Komita H, Ochi T, Fujiwara H, Yasukawa M, Mineno J, Shiku H, Nishida S, Sugiyama H, Tajiri H, Homma S. Gemcitabine enhances wilms’ tumor gene WT1 expression and sensitizes human pancreatic cancer cells with WT1-specific T-cell-mediated antitumor immune response. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(9):1289–1297. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1033-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishizaki H, Manuel ER, Song GY, Srivastava T, Sun S, Diamond DJ, Ellenhorn JD. Modified vaccinia Ankara expressing survivin combined with gemcitabine generates specific antitumor effects in a murine pancreatic carcinoma model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0923-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.