Abstract

Tumor-draining lymph node (TDLN) ablation is routinely performed in the management of cancer; nevertheless, its usefulness is at present a matter of debate. TDLN are central sites where T cell priming to tumor antigens and onset of the antitumor immune response occur. However, tumor-induced immunosuppression has been demonstrated at TDLN, leading to downregulation of antitumor reaction and tolerance induction. Tolerance in turn is a main impairment for immunotherapy trials. We used a murine immunogenic fibrosarcoma that evolves to a tolerogenic state, to study the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying tolerance induction at the level of TDLN and to design an appropriate immunotherapy. We determined that following a transient activation, the established tumor induces signs of immunosuppression at TDLN that coexist with local and systemic evidences of antitumor response. Therefore, we evaluated the feasibility of removing TDLN in order to eliminate a focus of immunosuppression and favor tumor rejection; but instead, a marked exacerbation of tumor growth was induced. Combining TDLN ablation with the in vivo depletion of regulatory cells by low-dose cyclophosphamide and the restoring of the TDLN-derived cells into the donor mouse by adoptive transference, resulted in lowered tumor growth, enhanced survival and a considerable degree of tumor regression. Our results demonstrate that important antitumor elements can be eliminated by lymphadenectomy and proved that the concurrent administration of low-dose chemotherapy along with the reinoculation of autologous cytotoxic cells provides protection. We suggest that this protocol may be useful, especially in the cases where lymphadenectomy is mandatory.

Keywords: Tumor immunity, Tolerance, Immunotherapy, Tumor-draining lymph node, Lymphadenectomy

Introduction

Overall cancer remission rates have remained essentially unchanged for the past decades [1]. Increasing evidence in patients and animal models indicating that malignant tissue is potentially immunogenic has led to immunological therapies (IT) to control and eradicate cancer [2, 3]. However, even in the case of proven antigenicity and significant lymphocyte infiltration, therapeutically induced rejection of established tumors is a very unusual event. Consensus exists that an active process of tolerization of the immune system is mounted and maintained by tumor cells [4–6]. In advanced disease, the state of tolerance is not merely the absence of immune response but a widespread immunosuppression that constitutes a major obstacle against the efficacy of immunological trials [5, 6]. Therefore, new insights into the mechanisms governing the establishment of tolerance in tumor hosts are necessary before IT can be successfully applied.

The experimental murine fibrosarcoma MCC is a highly immunogenic tumor induced by 3-methylcholanthrene in a BALB/c mouse [7, 8]. The specific immune response elicited by MCC is not strong enough to reject the growing tumor, and after a certain volume it declines and disappears creating a state of tolerance [7, 9]. The immunological characteristics of MCC, including its rapid growth in vivo, make it a suitable model to study mechanisms underlying early tumor immunity and tumor-mediated immunosuppression.

Among tumor host lymph nodes (LN), those which drain the lymphatic vessels from the tumor site (tumor-draining lymph nodes or TDLN) have been associated with the malignant dissemination, and partial or vast lymphadenectomy is routinely performed for diagnosis, staging and treating cancer [10]. At present, however, the helpfulness of TDLN removal or keeping is a matter of debate [11, 12], and these organs are given greater biological than anatomic relevance since they constitute the physical spot where both the initiation of antitumor immune response [13] and tolerization [14] may occur.

The aim of this work was to study the immunological changes that underlie tumor-generated tolerance at the level of TDLN in order to design an appropriate immunological treatment.

Materials and methods

Mice

Two- to three-month-old male BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice inbred in the animal facilities of the Instituto de Investigaciones Hematológicas, Buenos Aires, and housed according to the policies of the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, were used.

Tumor and tumor lysate

The MCC fibrosarcoma was induced in a BALB/c male by s.c. implantation of a methylcholanthrene pellet. It is maintained by syngeneic transplantation, giving rise to a solid non-metastatic tumor. Studies were performed between passages 20 and 25 in two successive stages of MCC growth: IMM (immunogenic established tumor, volume 100–400 mm3) and ADV (tolerogenic advanced tumor, volume 800–1,200 mm3). In some experiments an early time point (2 days post-tumor cell inoculation “2 days p.i.”) is also shown. Proximal and distal LN remain free from tumor cells along MCC development [8]. Tumor size and volume were assessed every 2 days according to the Attia and Weiss formula. For tumor lysate preparation, MCC cells (1 × 106/ml) were lysed by six freezing–thawing cycles, sonicated for 10 min in a Branson Digital Sonifier and passed through a 0.2 μm filter.

Cells and culture conditions

LN or tumor tissue were aseptically excised and mechanically disaggregated in PBS. Single cell suspensions were cultured in complete medium (CM: RPMI1640, Gibco; 10% fetal bovine serum, Natocor, Argentina; l-glutamine, penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B and 2-mercaptoethanol; Gibco), at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Single spleen cell suspensions were obtained by mechanical dissociation followed by sedimentation over Ficoll (1.09 g/cm3).

Flow cytometry

LN cells (1 × 106) were incubated with appropriate concentration of the following mAb (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA): FITC or PE anti-CD8α (clone 53-6.7), FITC anti-CD80 (clone 16-10A1), FITC anti-CD40 (clone HM40-3), FITC anti-I-Ad (clone AMS-32.1), FITC or PE anti-CD11c (clone HL3), FITC anti-CD4 (clone H129.19), PE anti-CD19 (clone 1D3), PE anti-IFN-γ, PE anti-IL-10, PE-Cy5.5 anti-CD45R/B220 (clone RA3-6B2), PE-Cy5.5 anti-CD25 (clone PC61). Cells were analyzed using a FACS flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and Winmdi software. Irrelevant isotype-matched antibodies were used as controls. Intracellular presence of Foxp3 was detected with PE anti-Foxp3 and the Foxp3 staining buffer set (e-Bioscience); intracellular staining of IL-10 and IFN-γ were detected with above-mentioned antibodies and Cytofix/Cytoperm and Perm/Wash buffer (Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cytokine production

Commercial ELISA kits (e-Bioscience) were used following the manufacturer’s instructions. Secreted cytokines were determined in serum or in cell-free supernatants from tumor or LN cell cultures exposed to tumor lysate (1:1). Cells (2–5 × 106 cells/ml) were cultured for 24 h for determination of TGF-β and IFN-γ or 72 h for IL-10 and IL-12.

Contact sensitivity response (CSR)

A modification of a previous protocol was used [15]. At day 0 mice were painted on TDLN or nTDLN skin areas with 50 μl 1% FITC in acetone–dibutylphthalate (DBF) solution (1:1 v/v) or vehicle. At day 6, animals were challenged with 10 μl 1% FITC onto both sides of one ear. Ear swelling was measured by micrometer before and 48 h after the second challenge.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)

C57BL/6 mouse LN cells (2 × 105) were incubated with 5 × 104 mitomycin C (Sigma)-treated tumor bearing mouse LN cells for 96 h, with a final 18 h pulse of 1 μCi/well [3H]-thymidine (Dupont, NEN Res Products, Boston, MA). Incorporated radioactivity was measured in a liquid scintillation Beta counter (Beckman). 5 μg/ml IL-10 neutralizing antibody (Pharmingen) was added or not at the beginning of the incubation. Proliferation rate standard deviation was calculated by the error propagation method.

Cytotoxicity assays

In vitro cytotoxicity was evaluated through the JAM test [16]. Briefly, tumor-bearing mice LN cells (1 × 106) were incubated with [3H]-thymidine-labeled MCC cells (2.5 × 104) for 8 h. Specific killing was calculated as % = 100 × (S − E)/S, where S is the spontaneous killing and E is the experimental killing. Normal [3H]-thymidine-labeled fibroblasts (target) were used as controls.

Regulatory T cell inhibitory function

T-reg suppressive function was evaluated through a previously described protocol [17]. CD4+CD25+ (T-reg), CD4+CD25− (T-eff) and CD4− were isolated from inguinal lymph node (Normal, IMM, Cy-treated mice) by cell sorting (FACSARIA II). CD4− were irradiated (3,300 rad) and plated onto 96-well plates (105 cells/well). T-eff cells (104cells/well) were then added with or without T-reg (104cells/well). Cells were incubated in CM with a combination of 1 μg/ml of soluble anti-CD3 and 1 μg/ml of soluble anti-CD28 to provide the polyclonal stimulus for proliferation. At day 4, 1 μCi of 3H-thymidine was added for 18 h to assess proliferation.

Ablation of TDLN (LNx)

Inguinal TDLN were surgically removed during IMM or ADV.

Ex vivo activation and expansion of TDLN-derived cells

A previously described method was used [18]. Briefly, TDLN cells were activated with 1 μg/ml immobilized anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11, BD Pharmigen) on 24-well culture plates at 2 × 106/ml CM for 2 days. Harvested cells were further cultured at 2 × 105/ml CM containing 5U/ml rIL-2 (BD biosciences). Three days later cells were resuspended in PBS for adoptive transference or cytometry, or in CM for the JAM test.

Immunotherapeutic protocol: low-dose cyclophosphamide (Cy) + TDLN ablation (LNx) + adoptive transference of TDLN-derived cells (AT)

At day 0, mice carrying IMM tumors were i.p. inoculated with 50 mg/kg Cy (Kampel Martian) and 4 days later, TDLN were removed and cells were cultured with anti-CD3 and IL-2 as explained above. At day 9, donor mice were i.v. injected with 5 × 106 cultured cells/ml PBS. Untreated and partially treated animals were used as controls. Subsequent tumor growth and survival were assessed daily for a period of 4 months.

Statistics

Differences in phenotype were evaluated by Student’s t test. Cytokines levels and tumor growth curves were compared by one-way ANOVA and Turkey’s multiple comparison test. Survival data were analyzed by the log-rank test. Differences in JAM test were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. All tests were interpreted in a two-tailed fashion and p < 0.05 was considered significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to control non-tumor-bearing mice; a p < 0.05, b p < 0.01, c p < 0.001, compared to other experimental groups).

Results

Tumor growth induces changes in the cellular composition of tumor-draining (TDLN) and distal non-tumor-draining lymph nodes (nTDLN)

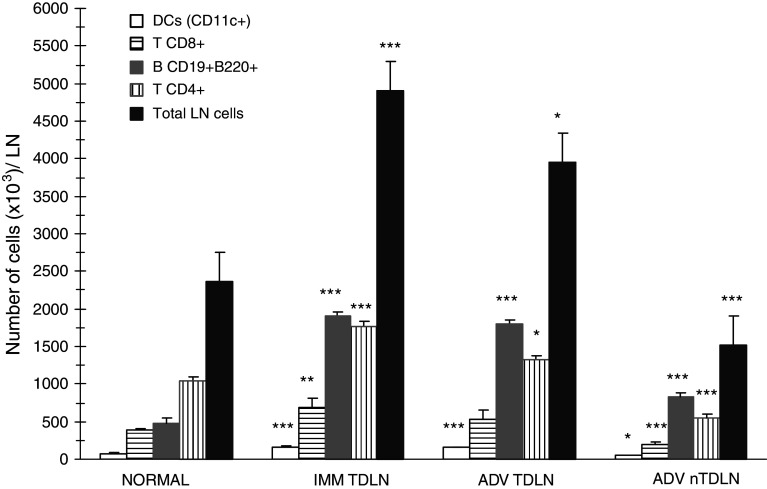

Studies were performed at two separate phases of MCC progression, 15 and 30 days after tumor inoculum, representing (a) an intermediate-volume tumor, which has been proven to elicit specific immunity, “IMM” and (b) an advanced high-volume tumor, to which the host is habitually tolerant, “ADV” [7]. The presence of MCC induced increased total nucleated cell number in the TDLN. When individual immune cell populations were analyzed, CD11c+ dendritic cells (DC), CD8+ and CD4+ T cells and more distinctly, CD19+B220+ B lymphocytes, augmented compared with non-tumor-bearing mice LN (normal). In contrast, no variations occurred in nTDLN until the ADV stage, when every cell type decreased below normal values, except for B cells which augmented (Fig. 1). Interestingly, during ADV, not only the contralateral inguinal nTDLN, but also every LN distant to the tumor site had small size and low cell number compared to normal LN (not shown). Variations in the percentual composition were seen at both LN and comprised increased proportion of B cells and decreased proportion of T cells.

Fig. 1.

The growth of MCC induces an increase in the number of total cells, DC, T and B lymphocytes within the TDLN, and a late decrease of total cells, DC and T cells within nTDLN. Lymph node cells were isolated from inguinal TDLN and contralateral nTDLN and total cell number was determined by hemocytometer. Cell suspensions were then stained with the specific monoclonal antibodies for flow cytometry. Absolute cell number for different cell types at the indicated stages of tumor growth was calculated into the nucleated-viable cell gate. The graphic shows mean number of cells ± SD from a representative experiment, n = 4 mice per group. For total LN cells, cumulative data from 9–24 mice per group is shown

Tumor growth induces changes in the phenotype and function of LN-derived antigen presenting cells (APC)

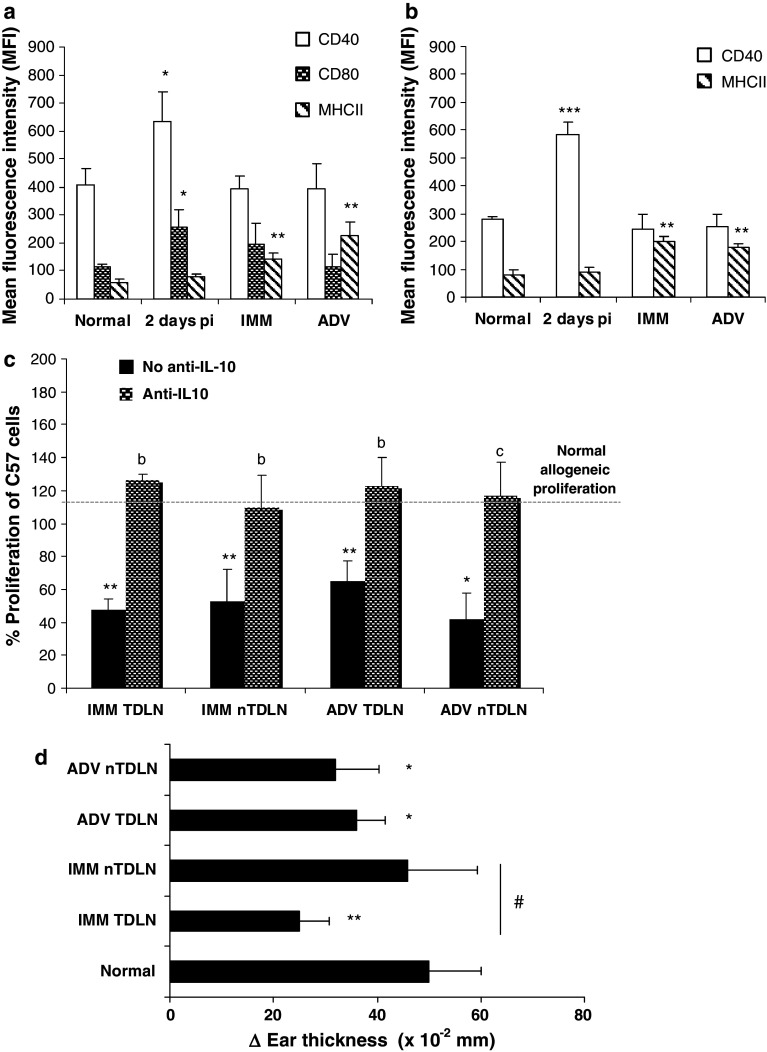

Two days after tumor cells inoculation (2 days p.i.) there was a per cell increase in the expression of the costimulatory molecules CD40 and CD80 on DC and CD40 on B cells at TDLN, denoting an initial, probably non-specific APC activation at the site of tumor implantation. Once the tumor is established, at IMM and ADV stages, APC showed enhanced expression of MHC class II molecules without variation in CD40 or CD80, both in TDLN and nTDLN, suggesting immature/suppressor phenotype [19] (Fig. 2a, b). Among suppressor DC described in mouse LN, a subset of plasmacytoid DC (pDC) that constitutively expresses immunosuppressive molecules and B lineage markers was described [20]. We found that the proportion of these potentially tolerogenic cells increased in IMM and ADV at TDLN and nTDLN (% B220+CD19+ in CD11c+ cells ± SD, normal, 19.2 ± 2.6; IMMTDLN, 44.6 ± 3.5***; IMMnTDLN, 33.0 ± 0.8***; ADVTDLN, 46.2 ± 4.3***; ADVnTDLN, 35.5 ± 1.7***; data from one representative experiment, n = 4 mice/group).

Fig. 2.

MCC growth alters APC phenotype and impairs APC function at TDLN and nTDLN. Lymph node cells were isolated from tumor-bearing mice and the expression of MHCII, CD40 and CD80 on CD11c+ DC (a) and MHCII and CD40 on CD19+ B cells (b) was assessed by flow cytometry. Bars show the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SD from a representative experiment (n = 3–5). c The ability of LN-derived cells to induce allogeneic proliferation was evaluated by MLR using C57BL/6 mice LN cells as a target. The bars show C57BL/6 proliferation (cpm) obtained in the presence of LN cells from tumor-bearing mice, related to that obtained in the presence of LN cells from normal mice (100%). Gray and black bars represent C57 proliferation in the presence/absence of anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody, respectively. One representative experiment is shown (b p < 0.01 and c p < 0.001 vs. non-IL-10-treated wells). d The contact sensitivity reaction (CSR) against the surface antigen DBF-FITC was measured 6 days after the first exposure. Ear thickness was measured before and 48 h after the second challenge. Values represent the mean change in ear thickness ± SD (vehicle, 0–10 × 10−2 mm) from a reproducible experiment, n = 3–5 mice/group (# p < 0.05 IMMTDLN vs. IMMnTDLN)

The function of LN-derived APC was studied by two different assays: first, their ability to induce allogeneic proliferation in a MLR. Despite the high membrane expression of MHCII on DC, LN cells from mice carrying IMM and ADV tumors induced lower allogeneic proliferation than their normal counterparts, suggesting that an inhibitory factor or cellular type might be interfering with proliferation. Since IL-10 production is a widespread inhibitory mechanism for B lymphocytes and pDC in tumors [21–23], we added a blocking concentration of anti-IL10 mAb, and obtained restored MLR response (Fig. 2c). Secondly, we studied the ability of skin Langerhans cells (LC) to uptake a surface antigen, migrate to the nodes and stimulate a T cell response; this method was previously proposed as a way to study the effect of tumor presence on the APC function [15]. We observed enhanced antigen uptake and migration during IMM and ADV, not only when the antigen was applied over the TDLN area, but also distantly. Unexpectedly, most (65–78%) of the FITC-loaded APC that got the LN draining the painted area were B220+ B cells. The contact sensitivity response (CSR) was measured 6 days later. Whereas normal mice showed a strong response, it was largely inhibited in IMM and ADV tumor-bearing mice, first at tumor proximity (IMM) and then systemically (ADV) (Fig. 2d).

Tumor growth induces changes in the phenotype and cytotoxic capacity of LN-derived T cells

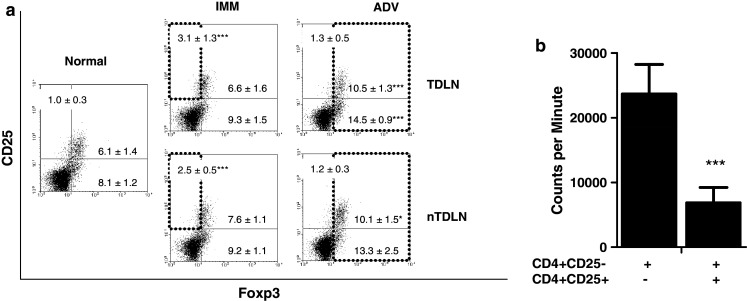

Phenotypically activated T cells (CD4+CD25+Foxp3−) increased among the CD4+ population during IMM and decreased in ADV, both in TDLN and nTDLN. Whereas activated T cells decreased, the proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (T-reg) augmented, reaching significance in ADV, as did the CD4+CD25−Foxp3+ subset, which has been described as a reservoir [24] or dividing T-reg [25] (Fig. 3a). Although in low percentage, CD4+CD25+ T cells isolated from the TDLN during IMM were able to inhibit proliferation of conventional T cells (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

The LN proportion of activated CD4+CD25+Foxp3− T cells increases during IMM, while CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells increase during ADV. Regulatory T cells isolated from tumor-bearing mice LN exhibit inhibitory function. a Dot plots from one reproducible experiment show CD25 versus Foxp3 positive cells, gated within CD4+ cells. Rectangles show increased proportion of activated T cells (CD25+Foxp3−/CD4+) in IMM and T-reg (Foxp3+/CD4+) in ADV. b Bars show the inhibitory effect of T-reg obtained from IMM TDLN on the proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation. Representative data from one of two experiments is shown (n = 6)

On the other hand, the number of CD8+ T lymphocytes expressing CD25 increased during IMM suggesting activation (no. CD25+CD8+ T cells × 103: normal, 21.4 ± 5.6; IMM, 62.4 ± 21.6*; ADV, 28.1 ± 6.6). The expression of Foxp3 in CD8+ T cells was null.

Anti-MCC cytotoxicity was evaluated by studying the ability of LN-derived cells to kill MCC cells in vitro [16]. Cultured TDLN and nTDLN cells from IMM and ADV exhibited enhanced percentage of specific cytotoxicity compared with normal mice (% mean ± SD: normal, 12.3 ± 0.7; IMMTDLN, 29.8 ± 0.7***; IMMnTDLN, 27.8 ± 4.3**; ADVTDLN, 28.5 ± 0.9***; ADVnTDLN, 29.4 ± 3.6**; data from a reproducible experiment, n = 3 mice/group).

Tumor growth induces changes in the cytokine profile of lymph nodes and sera

The local cytokine milieu has a significant impact on immune cell maturation and function (i.e., immune suppressive [21, 22, 26] or stimulatory [27]). To study the involvement of most important cytokines in the immune response to MCC, sera from tumor-bearing mice, and tumor and LN culture supernatants, were examined for the presence of IL-10, IFN-γ, IL-12 and TGF-β. No stimulatory cytokines IL-12 or IFN-γ were detected in tumor bearers’ sera or supernatants at any time point. With respect to suppressive cytokines, significant amounts of IL-10 were secreted by LN cells obtained during IMM and ADV stimulated in vitro with tumor lysate (normal, 235.3 ± 25; IMMTDLN, 367.2 ± 45***; IMMnTDLN, 354 ± 41***; ADVTDLN, 367.2 ± 17***; ADVnTDLN, 310.7 ± 12** pg/ml IL-10), whereas TGF-β was detected in IMM and ADV sera and in MCC culture supernatant (2,883 ± 536; 2,838 ± 610 and 1,988 ± 604 pg/ml TGF-β, respectively) and was undetectable in sera from normal mice (<62 pg/ml TGF-β). Data were obtained from two separate experiments with 5–6 mice per group.

In another set of experiments, intracellular presence of IFN-γ and IL-10 was evaluated in LN-derived T, B and DC. The number of CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes expressing IFN-γ augmented during IMM at both LN (Fig. 4a), suggesting that a potential cytotoxic activity involving effector CD8+ T and helper CD4+ T cells exists during the IMM phase, both near and distant to the tumor site. At the same time, the number of B lymphocytes expressing IL-10 markedly increased in every phase (Fig. 4a, b), probably indicating inhibitory roles for this cell population. No expression of IL-10 by DC and T-reg or IFN-γ by DC was detected at any time point.

Fig. 4.

Tumor induces changes in the intracellular cytokine expression in LN-derived cells. a Figure shows a representative experiment (n = 3–5) showing the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ and B cells expressing IL-10 within LN. b Representative dot plots showing the increase in LN-derived B cells expressing IL-10. Numbers next to the dot plots indicate the percentage of cells positive for B220 and IL-10 within the whole LN

The ablation of the TDLN (LNx) during the IMM phase exacerbates tumor growth

The above data indicated that immunosuppressive elements are present at the LN of mice bearing established IMM tumors. Since TDLN is considered a central place where immunosuppression and tolerance to tumor antigens are originated, and given the fact that systemic anti-MCC immunity is manifested in this stage [7–9], we evaluated the hypothesis that the surgical removal of TDLN (LNx) at IMM would negatively affect tumor progression. On the contrary, LNx induced a marked exacerbation of tumor growth (Fig. 5a), while no differences were obtained in the growth of tumors from intact, sham-operated and mice that underwent LNx during ADV (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Effect of lymphadenectomy, cyclophosphamide and adoptive transference on the tumor growth and host survival. a Mice carrying tumors IMM were subjected to ablation of the TDLN (LNx) or sham-operated. Tumor growth was assessed daily, and experiments were ended at a tumor volume of 2,500 mm3. Representative data from one of four experiments is shown (n = 7–9, b p < 0.01 and c p < 0.001 for LNx vs. Sham). b MCC-bearing mice were administered 50 mg/kg Cy and subjected to LNx or Sham-operation. The excised TDLN-derived cells were ex vivo activated with anti-CD3 and expanded with IL-2, and subsequently re-injected in the donor mouse by i.v. AT. The curves show the growth of tumors that did not undergo complete regression, over a period of 30 days (b p < 0.01 and c p < 0.001 for Cy + LNx + AT vs. untreated). c Survival of 15–32 mice per group was monitored over a period of 80 days. Numbers next to the graph reference indicate the statistical significance versus the untreated group

Administration of low-dose cyclophosphamide (Cy) followed by the adoptive transference (AT) of ex vivo-treated TDLN cells induces tumor regression and improves survival

In view of the LNx-induced tumor exacerbation, we evaluated the helpfulness of supplementing LNx with two procedures: the reduction of endogenous regulatory cells by low-dose Cy and the restoration of cytotoxic cells from the excised TDLN, which had been previously activated and expanded ex vivo with anti-CD3 and IL-2. Remarkably, 19 out of 30 (63%) fully treated mice (Cy + LNx + AT) underwent complete tumor regression with no recurrences, while no regression was obtained either in untreated or partially treated animals (not shown). Additionally, the growth of those tumors that did not regress (11/30) exhibited significantly lower growth compared to the untreated group, as shown in Fig. 5b. It is worthy to mention that neither Cy alone nor adoptive transference of cytotoxic T cells induces regression. Survival rates shown in Fig. 5c indicated that treatments with Cy + LNx + AT and Cy + LNx significantly enhanced survival.

In vivo administration of Cy reduces B and T-reg cell number, while ex vivo exposition to anti-CD3 and IL-2 changes the composition and cytotoxic ability of cultured TDLN cells

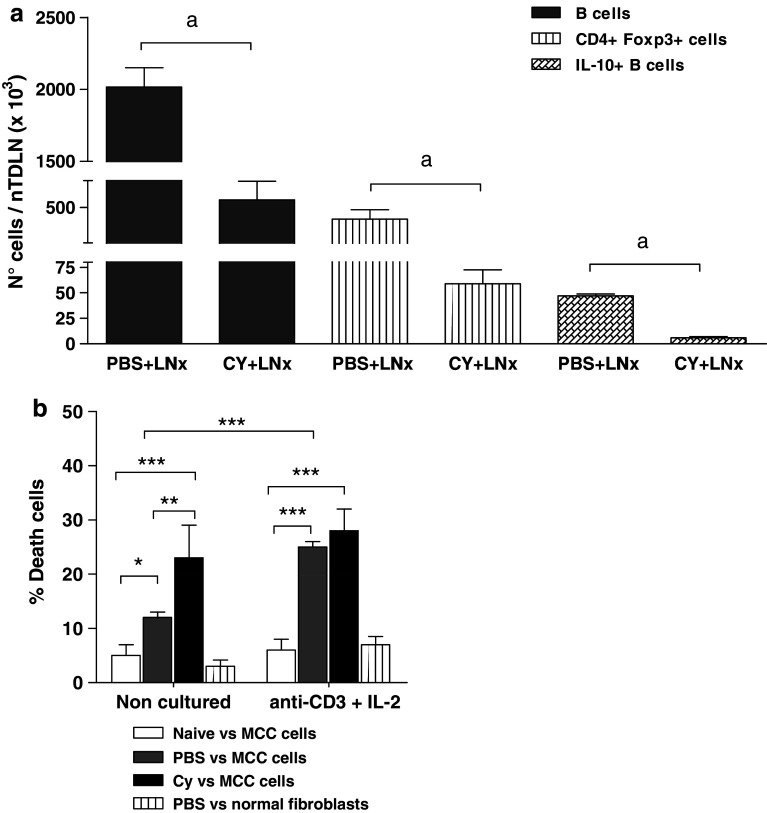

To elucidate the mechanisms operating in the treatment, we evaluated the effects of in vivo administration of 50 mg/kg Cy on day 4 (corresponding to the time point previous to LNx; see methods) and on day 9 (5 days after LNx), on the number of potentially suppressive cells, B and T-reg, present at contralateral nTDLN. A non-significant reduction in the content of total B cells, IL-10-expressing B cells and T-reg was induced by Cy on day 4 (not shown), whereas decreases were significant on day 9 (Fig. 6a). Moreover, isolated T-reg cells from Cy-treated mice did not show inhibitory capacity upon CD4+CD25− T cell proliferation (not shown).

Fig. 6.

In vivo effects of cyclophosphamide and ex vivo effects of anti-CD3+IL-2. a The figure shows the number of total B cells, T-reg and IL-10+ B cells at nTDLN at day 9 after i.p. injection of 50 mg/kg Cy from a representative experiment; n = 4–6. b Tumor-draining lymph node were removed from MCC-bearing mice 4 days after Cy or PBS administration, and resulting cell suspensions were cultured with anti-CD3 and IL-2 for 5 days. In vitro specific anti-MCC cytotoxicity was assessed by JAM test before and after exposure to anti-CD3 and IL-2. Lymph node cells from naïve mice and normal fibroblast were used as controls. One representative experiment is shown (n = 3)

We analyzed the effect of anti-CD3 and IL-2 on cultured TDLN cells before their AT. While freshly harvested cells from Cy-treated mice were mostly composed of B, CD4+T and CD8+T cells, ex vivo exposition to anti-CD3 and IL-2 increased the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+T and strongly decrease B cells (% cells before versus after the culture: B220+CD19+, 44 ± 3 vs 7.3 ± 2***; CD4+, 37 ± 1 vs 74 ± 7***; CD8+, 17.3 ± 0.5 vs 26.8 ± 6**; one representative experiment, n = 6). Additionally, the culture raised the proportion of T cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ (not shown). The anti-MCC cytotoxicity of these cells is shown in Fig. 6b. Lymph node cells from Cy-administered mice showed higher in vitro cytotoxicity than PBS-treated and non-tumor-bearing mice. In turn, culture with anti-CD3 and IL-2 improved the cytotoxicity of cells from PBS-treated mice but did not change the already high cytotoxicity of cells from Cy-treated animals.

Discussion

Tumor progression in normal individuals may reflect a failure of the innate and adaptive immune responses. Immunosuppressive mechanisms elicited by many cancers not only dampen endogenous antitumor responses but also weaken the efficacy of current immunotherapies (IT). Thus, a better understanding of interactions between the immune system and developing tumors is needed in order to reverse tumor-mediated immunosuppression and improve IT for cancer. We used an experimental tumor, MCC, which has been shown to evolve from a state of immunogenicity (IMM) to a tolerance condition (ADV) [7]. During the IMM phase, MCC generates a strong systemic antitumor response, which does not impede tumor progression and progressively declines and disappears [7–9]. Yet, the main aspects referring the cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the changes in tumor immunogenicity remain still unknown. Given that the proximal lymphatic nodes are judged relevant organs in cancer immunity, those draining the tumor zone (TDLN) were chosen to study the tumor-induced changes in the main immune cell components. As a distal counterpart, non-tumor-draining contralateral inguinal lymph nodes (nTDLN) were used.

After transient phenotypic signs of immune activation mainly at tumor proximities (Figs. 3, 4), once the tumor is established, immunosuppression prevails in both LN. Signs of immunosuppression at LN comprised, firstly, variations in APC subsets. The low expression of costimulatory molecules by DC and B cells and the plasmacytoid phenotype of most DC, suggested impaired APC function. In effect, both the ability to induce allogeneic proliferation and evoke a T response to a non-related antigen was deficient in LN cells from mice carrying IMM and ADV tumors. In the second place, there was altered ratio between effector and regulatory cells. Previous studies have shown that immature and plasmacytoid DC generate tolerance to tumors through the induction of T-reg [5, 20], which in turn are a potent suppressor of cytotoxic lymphocytes [28–30]. In our model, the proportion of T-reg increases as activated T cells decrease with tumor progression; moreover, T-reg isolated from TDLN showed inhibitory effect upon conventional T cell proliferation (Fig. 3). In addition to T-reg, an elevated number of IL-10-expressing B cells in TDLN and nTDLN parallels MCC growth in every tumor stage, suggesting an inhibitory role for B cells as well. Accordingly, previous studies in human [31] and animal [21, 22] cancer provided evidence of a regulatory role for B cells, mostly through IL-10 production.

Cumulative data from the cytokine analysis indicate that advanced MCC tumor evokes a late (ADV) suppressive milieu with IL-10+B cells at both LN, while for intermediate tumor volumes (IMM), there were IL-10+ B cells and IFN-γ+ CD4 and CD8 T cells; these are potentially suppressive and stimulatory elements exist simultaneously inside both LN. Since many of the suppression signs were first induced at TDLN, and given their markedly higher cell content, TDLN constitute a more suitable initial and functional focus of inhibition compared with neighboring LN. As previously mentioned, a systemic anti-MCC immune response had been shown to exist in MCC hosts during IMM [7]; we therefore postulated that removing TDLN (LNx) during IMM would impair MCC progression. In contrast, LNx resulted in unexpected acceleration of MCC growth, suggesting that suppressor mechanisms had been activated and/or that important antitumor elements had been subtracted by LNx.

It has been previously documented that low-dose Cy is able to decrease the number and inhibit the function of T-reg, thus enhancing the antitumor response and the efficacy of some IT [32–35]. On the other hand, it is known that high amounts of tumor-reactive CTL can be isolated from TDLN cells cultured with anti-CD3 and IL-2 [18, 36]. In view of these antecedents, we attempted to restore some of the primed cytotoxic cells through the AT of the excised TDLN cells into Cy-administered tumor bearers. With such protocol, decreased tumor growth, increased survival and approximately 60% of tumor remission were achieved. Additional observation of Cy and anti-CD3 plus IL-2 mode of action suggested that the mechanisms accounting for the protection are, at least in part, Cy-mediated T-reg and B cell reduction, and anti-CD3 plus IL-2-induced increase of IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity of TDLN-derived cells. In vivo effects of low-dose Cy have been referred in other tumor models to selectively deplete/inhibit T-reg without affecting conventional T cells. This specificity would rely on the differential expression of foxp3 [37] and/or the reduced intracellular ATP level [38] exhibited by T-reg. In addition to T-reg, our present results suggesting an inhibitory role for B cells bring the possibility that Cy-mediated B cell depletion constitutes another mechanism accounting for low-dose Cy protective effect.

It is important to mention that even when regional lymph node (RLN) adenectomy is routinely performed for studying and treating cancer, the actual convenience of this procedure is questioned by many facts. Firstly, the existence of lymphatic and venous shunts capable of bypassing RLN, allow in many cases the persistence of dissemination [39]. Secondly, RLN can constitute central priming sites [40], act as effective barriers to tumor dissemination [13, 41] and harbor pre-effector cells capable of destroying tumors through AT [34, 39]. Thirdly, clinical and experimental data indicate that LNx not always improves prognosis [42] and in some cases may decrease the effectiveness of immunotherapeutic protocols [43]. In this context, a more conservative behavior toward uninvolved RLN that permits the maintenance of the integrity of the immune system has been suggested to provide benefits.

We demonstrated that TDLN ablation can alter some important endogenous antitumor mechanisms, and showed that a therapeutic approach comprising the reinoculation of activated autologous CTL, preceded by Cy-mediated B cell and T-reg depletion, is able not only to counteract the worsening impact of LNx, but also to improve the antitumor immunity and induce tumor regression. We suggest that such protocol may be useful especially in cases where proximal lymphadenectomy is an inevitable procedure.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica and Fundación “Albert J. Roemmers”, República Argentina. The authors are grateful to Dr. Christiane Dosne Pasqualini for critical discussion of this article.

References

- 1.Bailar JC, Gornik HL. Cancer undefeated. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1569–1574. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705293362206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA. A new era for cancer immunotherapy based on the genes that encode cancer antigens. Immunity. 1999;10:281–287. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krüger C, Greten TF, Korangy F. Immune based therapies in cancer. Review. Histol Histopathol. 2007;22:687–696. doi: 10.14670/HH-22.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumor environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev. 2005;5:263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteside TL. Immune suppression in cancer: effects on immune cells, mechanisms and future therapeutic intervention. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16(1):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vieweg J, Su Z, Daham P, Kusmartsev S. Reversal of tumor-mediated immunosuppression. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:727–732. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franco M, Bustuoabad OD, di Gianni PD, Goldman A, Pasqualini CD, Ruggiero R. A serum-mediated mechanism for concomitant resistance shared by immunogenic and non-immunogenic murine tumors. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:178–186. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bustuoabad OD, Ruggiero RA, Di Gianni PD, Lombardi G, Beli C, Camerano GV, Dran GI, Schere-Levy C, Costa H, Isturiz MA, Narvaitz M, van Rooijen N, Bustuoabad VA, Meiss RP. Tumor transition zone: a new putative morphological and functional hallmark of tumor aggressiveness. Oncol Res. 2005;15:169–182. doi: 10.3727/096504005776367933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiarella P, Vulcano M, Bruzzo J, Vermeulen M, Vanzulli S, Maglioco AF, Camerano GV, Palacios V, Fernández G, Fernández Brando R, Isturiz M, Dran GI, Bustuoabad OD, Ruggiero RA. Anti-inflammatory pretreatment enables an efficient dendritic cell-based immunotherapy against established tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:701–718. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0410-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathanson SD. Insights into the mechanisms of lymph node metastasis. Cancer. 2003;98:413–423. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damle S, Teal CB. Can axillary lymph node dissection be safely omitted for early-stage breast cancer patients with sentinel lymph node micrometastasis? Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3215–3216. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0702-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dzwierzynski WW. Complete lymph node dissection for regional nodal metastasis. Clin Plast Surg. 2010;37(1):113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lores B, Garcia-Estevez JM, Arias C. Lymph nodes and human tumors (review) Int J Mol Med. 1998;1(4):729–733. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.1.4.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munn DH, Mellor AL. The tumor-draining lymph node as an immune-privileged site. Immunol Rev. 2006;213:146–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida T, Oyama T, Carbone T, Gabrilovich DI. Defective function of langerhans cells in tumor-bearing animals is the result of defective maturation from hemopoietic progenitors. J Immunol. 1998;161:4842–4851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matzinger P. The JAM test: a simple assay for DNA fragmentation and cell death. J Immunol Methods. 1991;145:185. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90325-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George JF, Braun A, Brusko TM, Joseph R, Bolisetty S, Wasserfall CH, Atkinson MA, Agarwal A, Kapturczak MH. Suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is dependent on expression of heme oxygenase-1 in antigen-presenting cells. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(1):154–160. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshizawa H, Chang AE, Shu S. Specific adoptive immunotherapy mediated by tumor-draining lymph node cells sequentially activated with anti-CD3 and IL-2. J Immunol. 1991;147:729–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K. Functional roles of immature dendritic cells in impaired immunity to solid tumors and their targeted strategies for provoking tumor immunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma MD, Babak B, Chandler P, Hou D-Y, Singh N, Yagita H, Azuma M, Blazar BR, Mellor AL, Munn DH. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells from mouse tumor-draining lymph nodes directly activate mature Tregs via indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(9):2570–2582. doi: 10.1172/JCI31911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue S, Leitner WW, Golding B, Scott D. Inhibitory effects of B cells on antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7741–7747. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumura Y, Byrne SN, Nghiem DX, Miyahara Y, Ullrich SE. A role for inflammatory mediators in the induction of immunoregulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:4810. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumura Y, Kobayashi T, Ichiyama K, Yoshida R, Hashimoto M, Takimoto T, Tanaka K, Chinen T, Shichita T, Wyss-Coray T, Sato K, Yoshimura A. Selective expansion of foxp3-positive regulatory T cells and immunosuppression by suppressors of cytokine signaling 3-deficient dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(4):2170–2179. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zelenay S, Lopes-Carvalho T, Caramalho I, Moraes-Fontes MF, Rebelo M, Demengeot J. Foxp3+ CD25−CD4 T cells constitute a reservoir of committed regulatory cells that regain CD25 expression upon homeostatic expansion. PNAS. 2005;102:4091–5006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito M, Minamiya Y, Kawai H, Saito S, Saito H, Nakagawa T, Imai K, Hirokawa M, Ogawa J. Tumor-derived TGFβ-1 induces dendritic cell apoptosis in the sentinel lymph node. J Immunol. 2006;176:5637–5643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uemura A, Takehara T, Miyagi T, Suzuki T, Tatsumi T, Ohkawa K, Kanto T, Hiramatsu N, Hayashi N. Natural killer cell is a major producer of interferon gamma that is critical for the IL-12-induced anti-tumor effect in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59(3):453–463. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0764-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallimore A, Godkin A. Regulatory T cells and tumor immunity—observations in mice and men. Immunology. 2007;123:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaput N, Darrasse-Jèze G, Bergot AS, Cordier C, Ngo-Abdalla S, Klatzmann D, Azogui O. Regulatory T cells prevent CD8 T cell maturation by inhibiting CD4 Th cells at tumor sites. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):4969–4978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curiel TJ. Regulatory T cells and treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Di Girolamo V, Laguens RP, Coronato S, Salas M, Spinelli O, Portiansky E, Laguens G. Quantitative and functional study of breast cancer axillary lymph nodes and those draining other human malignant tumors. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2000;19(2):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghiringhelli F, Larmonier N, Schmitt E, Parcellier A, Cathelin D, Garrido C, Chauffert B, Solary E, Bonnotte B, Martin F. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress tumor immunity but are sensitive to cyclophosphamide which allows immunotherapy of established tumors to be curative. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:336–344. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lutsiak ME, Semnani RT, De Pascalis R, Kashmiri SV, Schlom J, Sabzevari H. Inhibition of CD4+25+ T regulatory cell function implicated in enhanced immune response by low dose cyclophosphamide. Blood. 2005;105:2862–2868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ménard C, Martin F, Apetoh L, Bouyer F, Ghiringhelli F. Cancer chemotherapy: not only a direct cytotoxic effect, but also an adjuvant for antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(11):1579–1587. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tangu M, Harashima N, Yamada T, Harada T, Harada M. Immunogenic chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin against established murine carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59(5):769–777. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0797-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka H, Tanaka J, Kjaergaard J, Shu S. Depletion of CD4+CD25+ regulatory cells augments the generation of specific immune T cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. J Immunother. 2002;25(3):207–217. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200205000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roux S, Apetoh A, Chalmin F, Ladoire S, Mignot G, Puig P-E, Lauvau G, Zitvogel L, Martin F, Chauffert B, Yagita H, Solary E, Ghiringhelli CD4+CD25+ Tregs control the TRAIL dependent cytotoxicity of tumor-infiltrating DCs in rodent models of colon cancer. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3751–3761. doi: 10.1172/JCI35890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao J, Cao Y, Lei Y, Yang Z, Zhang B, Huang B. Selective Depletion of CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by low-dose cyclophosphamide is explained by reduced intracellular ATP levels. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):4850–4858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cady B. Lymph node metastases: indicators, but not governors, of survival. Arch Surg. 1984;119:1067–1072. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390210063014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiura T, Kagamu H, Miur S, Ishida A, Tanaka H, Tanaka J, Gejyo F, Yshizawa H. Both regulatory T cells and antitumor effector T cells are primed in the same draining lymph nodes during tumor progression. J Immunol. 2005;175:5058–5066. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abe R, Taneichi N. Lymphatic metastasis in experimental cecal cancer: effectiveness of lymph nodes as barriers to the spread of tumor cells. Arch Surg. 1972;104:95–98. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180010089023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veronesi U, Adamus J, Bandiera DC, Brennhovd IO, Caceres E, Cascinelli N, Claudio F, Ikonopisov RL, Javorskj V, Kirov S, Kulakowski A, Lacoub J, Lejeune F, Mechl Z, Morabito A, Rode I, Sergeev S, van Slooten E, Szcygiel K, Trapeznikov NN. Inefficacy of immediate node dissection in stage 1 melanoma of the limbs. N Engl J Med. 1977;297(12):627–630. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197709222971202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harada M, Tamada K, Abe K, Onoe Y, Tada H, Takenoyama M, Yasumoto K, Kimura G, Nomoto K. Systemic administration of interleukin-12 can restore the anti-tumor potential of B16 melanoma-draining lymph node cells impaired at a late tumor-bearing state. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:400–405. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980130)75:3<400::AID-IJC13>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]