Abstract

Nectin-4 is a tumor antigen present on the surface of breast, ovarian and lung carcinoma cells. It is rarely present in normal adult tissues and is therefore a candidate target for cancer immunotherapy. Here, we identified a Nectin-4 antigenic peptide that is naturally presented to T cells by HLA-A2 molecules. We first screened the 502 nonamer peptides of Nectin-4 (510 amino acids) for binding to and off-rate from eight different HLA class I molecules. We then combined biochemical, cellular and algorithmic assays to select 5 Nectin-4 peptides that bound to HLA-A*02:01 molecules. Cytolytic T lymphocytes were obtained from healthy donors, that specifically lyzed HLA-A2+ cells pulsed with 2 out of the 5 peptides, indicating the presence of anti-Nectin-4 CD8+ T lymphocytes in the human T cell repertoire. Finally, an HLA-A2-restricted cytolytic T cell clone derived from a breast cancer patient recognized peptide Nectin-4145–153 (VLVPPLPSL) and lyzed HLA-A2+ Nectin-4+ breast carcinoma cells. These results indicate that peptide Nectin-4145–153 is naturally processed for recognition by T cells on HLA-A2 molecules. It could be used to monitor antitumor T cell responses or to immunize breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Nectin-4, Tumor-associated antigen, Tumor vaccine, Epitope, MHC class I, CTL

Introduction

Over the last years, a new modality of cancer treatment has emerged with the remarkable clinical efficacy of several immunostimulatory antibodies [1]. These results have greatly stimulated the interest for cancer immunotherapy at large, demonstrating its clinical potential. The two main other modalities of cancer immunotherapy are adoptive T cell therapy and vaccination. The three modalities rely on the recognition by T lymphocytes of antigens that are present on tumor cells but are absent or present at very low levels on normal cells, so that the specific T cells can destroy tumor cells while sparing normal tissues. The identification of such tumor-specific antigens is key to the development of adoptive T cell therapy and cancer vaccines [2], and useful to monitor antitumor T cell responses in cancer patients treated with all immunotherapies.

We have described a new tumor-associated antigen, Nectin-4, encoded by gene PVRL4 (Poliovirus Receptor-Related 4) [3]. Nectin-4 is a surface protein belonging to a family of four members [4–6]. Nectins are cell adhesion molecules that play a key role in various biological processes such as polarity, proliferation, differentiation and migration for epithelial, endothelial, immune and neuronal cells, during development and adult life [6–9]. They are involved in several pathological processes in humans [10–12]. They are the main receptors for poliovirus, herpes simplex virus and measles virus [13, 14]. Mutations in gene PVRL4 can cause ectodermal dysplasia syndromes [12].

Nectin-4 protein is expressed during fetal development. In adult tissues, its expression is more restricted than that of other members of the Nectin family. Nectin-4 is a tumor-associated antigen in 33, 49 and 86 % of breast, ovarian and lung carcinomas, respectively, mostly on tumors of bad prognosis [3, 15, 16]. Its expression is not detected in the corresponding normal tissues [3, 15, 16]. In breast carcinomas, Nectin-4 is expressed mainly in the triple-negative subtype. In the serum of patients with these cancers, the levels of Nectin-4 increase during metastatic progression and decrease after treatment, and the detection of soluble forms of Nectin-4 is associated with a poor prognosis [3, 15, 16].

Nectin-4 could be a source of tumor-associated antigenic peptides presented to T cells, notably CD8+ cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTLs). The objective of this study was to identify such peptides, which could be used in vaccines or as targets in adoptive T cell therapy. We used a two-step approach: First, a selection of the most relevant candidate peptides using biochemical (iTopia Epitope Discovery System), cellular (T2 cells) and algorithmic methods, and second, a search for CTLs that could specifically recognize these candidate peptides on HLA-A2+ breast carcinoma cells expressing gene PVRL4.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

Human breast carcinoma cell lines MDA-MB-231 (basal) and BT-474 (ERBB2+) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS, 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 g/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. The cells were transfected with expression vector p3XFLR4.C1 containing a PVRL4 cDNA [17]. BT-474 cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10 % FBS, 10 g/ml insulin, 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 g/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. SUM-206 and SUM-159 (basal) breast carcinoma lines were kindly provided by Dr S. P. Ethier (University of Michigan). They were cultured in Ham’s F12 medium with 5 % FBS, non-essential amino acids, 10 g/ml insulin, 1 g/ml hydrocortisone, 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 g/ml streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine. B cells transformed by the Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV-B) cell lines were cultured in Iscove’s medium supplemented with 10 % FBS, 0.24 mM l-asparagine, 0.55 mM l-arginine, 1.5 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 g/ml streptomycin. Human recombinant IL-2 was purchased from Novartis. Human recombinant IL-4, IL-7 and GM-CSF were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Peptides

A library of 502 nonapeptides spanning the entire 510 amino acid sequence of human Nectin-4 was synthesized by JPT Peptide Technologies GmbH (Berlin, Germany). These peptides were numbered according to the position of their N-terminal residue in the Nectin-4 sequence. Nine reference peptides were added that have been validated as naturally processed and recognized by HLA-A2-restricted CTLs. They are listed in Fig. 1 and are derived from proteins GnT-V [18], MAGEA3 [19], MAGEA10 [20], MAGEC2 [21, 22], NY-ESO-1 [23], PRAME [24], Proteinase 3 [25], tyrosinase [26] and Hepatitis B virus core protein [27]. All peptides (purity >80 %) were dissolved at 10 mM in DMSO and stored at −20 °C. Additional control peptides for other HLA class I alleles were supplied in the iTopia Epitope Discovery System kit (Beckman Coulter Inc., San Diego, CA).

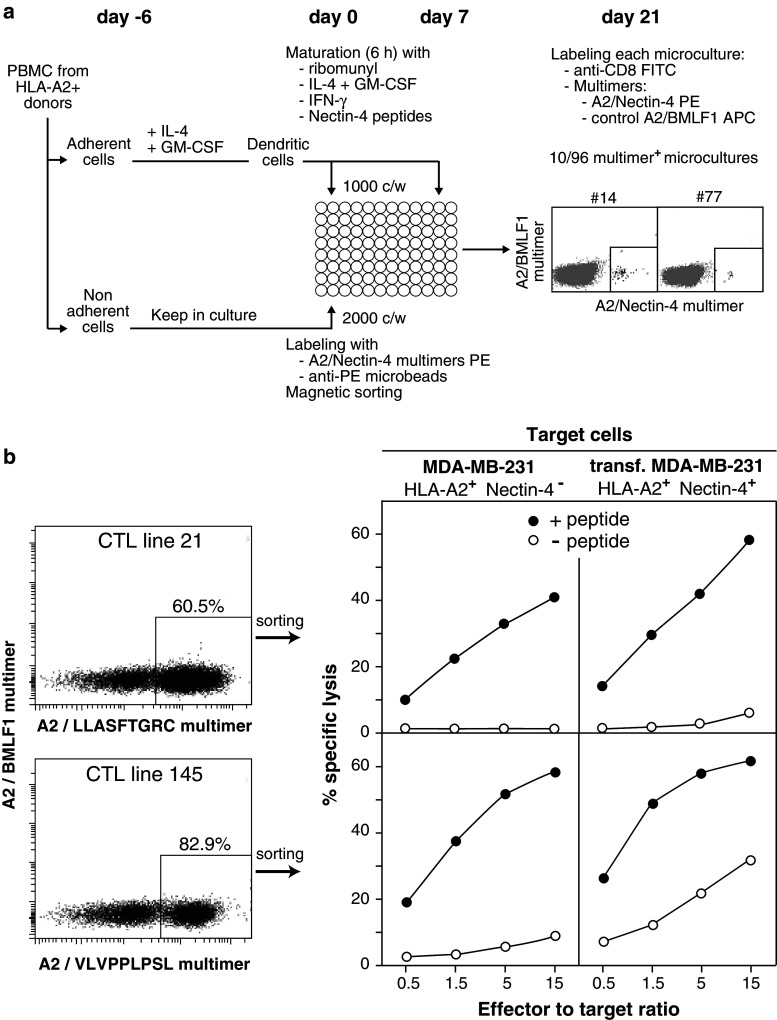

Fig. 1.

Binding curves and off-rates for Nectin-4 peptides selected by iTopia for binding to HLA-A*02:01 molecules. a List of reference peptides used in the study. b Peptide titration curves for selected Nectin-4 peptides. Peptides are named with the position of the first amino acid in the Nectin-4 sequence. c Peptide titration curves for reference peptides. d Off-rate curves for selected Nectin-4 peptides. e Off-rate curves for reference peptides. Assays were carried out in triplicate

HLA/peptide binding assays using iTopia Epitope Discovery System

Peptide binding, affinity and off-rate were evaluated in microwells coated with HLA class I monomers loaded with human β2-microglobulin (β2 m) and a placeholder peptide. The 502 Nectin-4 peptides were first evaluated for their ability to bind to each HLA molecule: The placeholder peptides were stripped from the insolubilized HLA/β2 m/peptide complexes, allowing the HLA class I heavy chains to bind candidate peptides in the presence of human β2 m, over 18 h at 21 °C. Refolding was assessed with a conformation-dependent anti-HLA-A/B/C monoclonal antibody coupled to FITC. The wells were then washed and fluorescence measured with the SpectraMax Gemini fluorimeter (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Peptides displaying a binding >30 % of that of the positive control peptide at a concentration of 100 μM were selected as “binders” and analyzed for affinity (ED50) and off-rate (t1/2). The cutoff was set at 30 % of the positive control because it corresponded to the lowest binding observed in a collection of 40 antigenic peptides that were known to bind to the tested HLA molecules and that were tested alongside the 502 Nectin-4 peptides. The affinity assay was carried out in the same conditions as for the binding assay with peptide concentrations ranging from 10−4 to 10−9 M. Affinity was estimated with the peptide concentration at which half-maximal binding was obtained (ED50). The off-rate assay evaluates the rate of dissociation of peptides incubated first with HLA class I monomers at 21 °C for 18 h, then at 37 °C over 8 h under agitation, with binding measurements at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h. The t1/2 value corresponds to the time in hours required to reach a 50 % reduction of fluorescence intensity. The iTopia software calculates for each peptide the multiparametric iScore, which includes results of binding, affinity and off-rate. Peptides with an iScore >0.50 were considered to be good candidates for HLA-A*02:01 binding. The corresponding graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). We made use of two publicly available algorithms that predict the binding of peptides to various HLA alleles : SYPEITHI (www.syfpeithi.de) and BIMAS (www-bimas.cit.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/).

Cellular binding assay

The CEM.T2 (T2) cell line expresses HLA-A*02:01 is deficient for the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) and is classically used to assess the stability of peptide/HLA-A2 complexes [28]. For HLA-A2 stabilization, T2 cells (2 × 105/well) were incubated with peptides (1, 10 and 100 µM) at 37 °C for 4 h in serum-free RPMI medium (Gibco, France), washed twice with PBS + 1 % BSA and incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-HLA-A2 monoclonal antibody BB7.2 (BD Bioscience Pharmingen, France) at 4 °C for 45 min. After three washes, cells were fixed in PBS + 2 % paraformaldehyde and analyzed with flow cytometry (FACScan, BD Bioscience). The percentage of peptide binding was calculated as follows: % Binding = {(MFIpeptide − MFI Neg contr)/(MFIPos contr − MFINeg contr)} × 100.

Peptide FLPSDFFPSV from Hepatitis B Virus [27] was used as positive control. The negative control was the assay carried out without peptide.

Cellular dissociation assay

The determination of cell surface half-lives of peptide/HLA-A2 complexes was performed as described [29]. Briefly, T2 cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in serum-free RPMI with peptide (50 μM), then Brefeldin A (10 µg/ml), which inhibits the transport of secretory and lysosomal proteins [30] was added and 1 h later the cells were washed three times and incubated at 37 °C in serum-free medium. At the onset of this incubation (T0) and 1 h (T1) and 4 h (T4) later surface levels of HLA-A2 molecules were measured by flow cytometry using FITC-conjugated BB7.2 antibody. The percentage of residual binding at time × (T×) was calculated as follows: 100 − {(MFIpeptide − MFINeg contr)T0 − (MFIpeptide − MFINeg contr)T×/(MFIPos contr − MFINeg contr)T0 − (MFIPos contr − MFINeg contr)T×} × 100

Production of HLA/peptide multimers

Recombinant HLA-A*02:01 molecules were folded with β2 m and Nectin-4 peptides or peptide VSDGGPNLY encoded by the early cytolytic gene BMLF1 of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) [31]. The procedure to obtain the HLA-peptide complexes was described previously [32], based on [33]. Soluble complexes were purified by gel filtration, biotinylated using the BirA enzyme and multimerized with either Extravidin-PE (phycoerythrin) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for the HLA-A2/Nectin-4 multimers or with streptavidin-APC (allophycocyanin) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for the HLA-A2/EBV control multimers.

Generation of anti-Nectin-4 CTL lines from healthy donors

We used dendritic cells to prime naive anti-Nectin-4 CD8+ T cells present in blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HLA-A2+ donors. To generate dendritic cells, PBMCs isolated by Lymphoprep (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) density gradient centrifugation were left to adhere for 1 h at 37 °C in tissue culture-treated flasks, in RPMI supplemented with 0.24 mM l-asparagine, 0.55 mM l-arginine, 1.5 mM l-glutamine, 1 % streptomycin/penicillin and 10 % FBS (complete RPMI). Non-adherent cells were harvested and cultured in Iscove’s supplemented with amino acids as above, 1 % streptomycin/penicillin, 10 % human serum and IL-2 (5 U/ml) for 6 days. Adherent cells were cultured for 5 days with GM-CSF (70 ng/ml) and IL-4 (200 U/ml) in complete RPMI, replacing 1/3 of the medium by fresh medium with cytokines on days 2 and 4. These monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells were incubated for 6 h with 10 μg/ml of a pool of Nectin-4 peptides #21 (LLASFTGRC), #80 (ALLHSKYGL), #145 (VLVPPLPSL) and #351 (VVVGVIAAL), IL-4 (200 U/ml), GM-CSF (70 ng/ml), 1 μg/ml of ribomunyl (Pierre Fabre Medicament, Boulogne, France) and 500 U/ml of Interferon-γ (R&D Systems). Ribomunyl is an immunostimulant containing ribosomal fractions of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes and Haemophilus influenzae, and membrane fractions of K. pneumoniae. It is an efficient clinical-grade maturation factor for dendritic cells [34]. These matured dendritic cells were used to stimulate blood T cells sorted with multimers (Fig. 3a), as described [35]. Multimer-labeled cells were incubated at 4 °C with anti-PE microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany). After three washes, cells were magnetically sorted with the AUTOMACS™ (Miltenyi Biotec). Sorted cells were incubated in U-bottomed microwells (2 × 104/200 μl) in Iscove’s medium containing IL-2 (20 U/ml), IL-7 (10 ng/ml), with 104 peptide-pulsed irradiated autologous dendritic cells. Multimer labeling was performed 2 weeks later, as described [36]. These experiments were carried out with PBMCs from two donors, and anti-Nectin-4 T cells were detected in both of them.

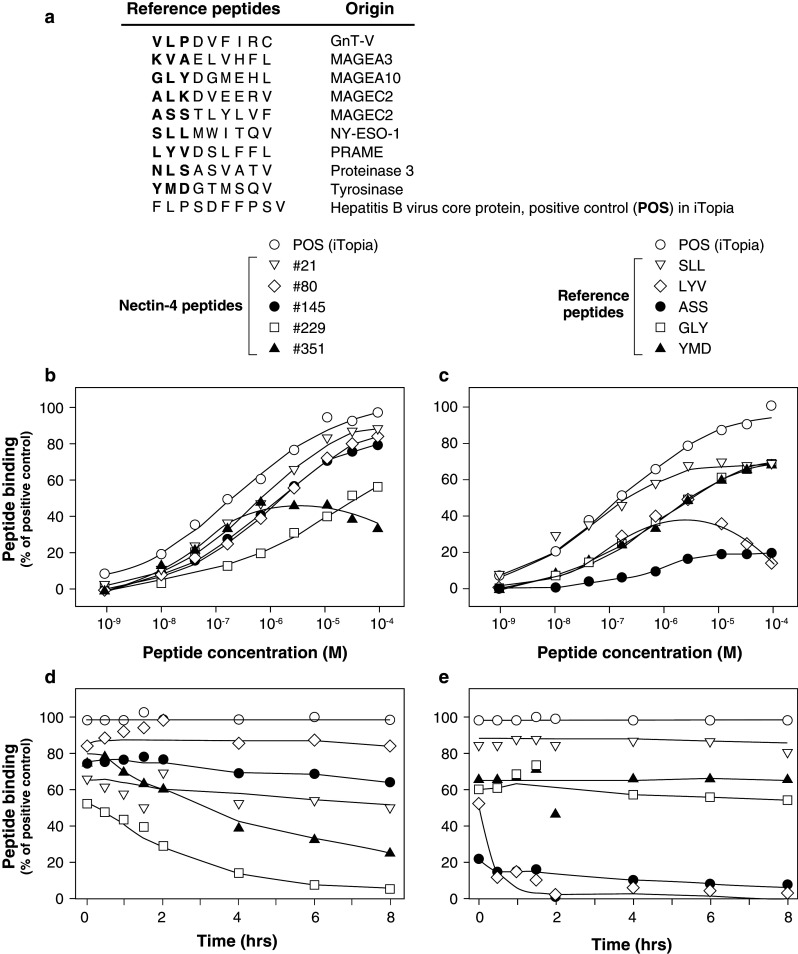

Fig. 3.

Anti-Nectin-4 CTL lines derived from PBMCs of healthy donors. a Overview of the procedure used to isolate and test anti-Nectin-4 CD8+ T cells from healthy donors, and examples of positive microcultures. b Left panels staining of CD8+ T cells of two microcultures with HLA-A2/Nectin-4 multimers loaded with Nectin-4 peptides #21 (top) and #145 (bottom). Right panels lytic activities of the multimer+ cells sorted from these microcultures. Target cells are MDA-MB-231 cells pulsed (10 µM) or not with the relevant Nectin-4 peptides, and MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with a Nectin-4 construct and pulsed or not with the peptides. The results are representative of two experiments performed with PBMCs from two donors

Isolation of CTL clone P88-40

Here, we restimulated the anti-Nectin-4 T cells that could be present in the PBMCs of 26 HLA-A2+ breast cancer patients. Stimulation was carried out in limiting dilution conditions with seven tumor-specific antigenic peptides known to bind to HLA-A2 molecules (Nectin-4 peptide #145 and peptides derived from MUC1, telomerase, HER2, MAGEC2 and NY-ESO-1). Pulsing with peptides was carried out independently for each peptide: One seventh of the PBMCs was pulsed with a given peptide, and the seven pulsed populations were pooled before distribution at 2 × 105 cells/microwell. Stimulation conditions were as described [36, 37] except for the use of seven stimulating peptides. Multimer labeling was performed after 16 days. CD8+ cells stained with the multimer containing Nectin-4 peptide #145 were detected in a single patient, P88. They were sorted and tested for cytolytic activity against the indicated target cells in classical 51Cr-release assays over 4 h.

Results

Identification of Nectin-4 peptides that bind to HLA class I molecules

Nectin-4 is 510 amino acids long. We screened 502 nonapeptides spanning the entire sequence, for binding to eight HLA class I molecules (A*01:01, A*02:01, A*03:01, A*11:01, A*24:02, B*07:02, B*08:01 and B*15:01) using the iTopia Epitope Discovery System™ which allows to measure binding and stability of peptides to HLA class I molecules. It is based on the denaturation/renaturation of immobilized HLA class I heavy chains followed by the detection of peptide-loaded refolded molecules with a conformation-sensitive anti-HLA antibody. Peptide binding was scored with an arbitrary cutoff of 30 % of the binding of a positive control peptide. In the initial screening, the numbers of positive peptides were 5 for HLA-A1, 130 for A2, 24 for A3, 38 for A11, 77 for A24, 28 for B7, 14 for B8 and 40 for B15 (data not shown). Thus, the proportions of binding peptides ranged from 1 to 26 % with the greatest proportions for HLA-A2 (26 %), HLA-A24 (15 %) and HLA-B15 (8 %).

We then focused our study on HLA-A*02:01, the most frequent HLA class I allele in caucasians. To enrich for the best binders, the cutoff value was increased to 50 %, resulting in a selection of 63 peptides.

Binding of Nectin-4 peptide to HLA-A2, affinity and off-rate stability

Analyses of binding affinity and off-rate stability were carried out with the 63 selected peptides alongside nine other peptides derived from various proteins and known to bind to HLA-A2 molecules. These reference peptides are listed in Fig. 1a. The results shown on Fig. 1b, d are only those obtained for 5 out of the 63 tested Nectin-4 peptides.

Nectin-4 peptides #21, #80 and #145 presented affinities close to that of the positive control peptide present in the iTopia kit (Fig. 1b). A comparison with published HLA-A2 binders is shown on Fig. 1c. For the three Nectin-4 peptides, the estimated concentration to reach 50 % maximal binding (ED50) was around 10−6 M (Fig. 1b).

The relative stability of the 63 peptide/HLA-A2 complexes was determined by measuring their dissociation time (t 1/2) over a period of 8 h. Peptides could be classified into three groups: 16 peptides with a t 1/2 > 4 h, 19 with a t 1/2 between 2 and 4 h and 28 with a t 1/2 < 2 h. Representative dissociation curves are represented in Fig. 1d for Nectin-4 peptides and Fig. 1e for reference peptides. Among the 16 Nectin-4 peptides with a t 1/2 greater than 4 h, three (#21, #80, #145) had a t 1/2 over 6 h (Fig. 1d). It is close to the t1/2 of the iTopia positive control peptide and of reference peptides SLL (from NY-ESO-1), YMD (from Tyrosinase) and GLY (from MAGEA10) (Fig. 1e). Nectin-4 peptides #351 (t 1/2 = 3.4 h) and #229 (t 1/2 = 1.7 h) displayed intermediate and low off-rate stabilities, respectively.

The results obtained in the binding and in the dissociation assays were included in the multiparametric iScore calculated by the iTopia software. According to the manufacturer’s recommendations, the 63 Nectin-4 peptides were classified in three groups: 23 peptides with an iScore ≤0.25, 18 peptides with an iScore between 0.25 and 0.50, and 22 peptides with an iScore ≥0.50. The latter peptides were considered to be “good binders” (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of binding to and dissociation from HLA-A2 molecules for Nectin-4 peptides and for reference and control peptides

| iScore Rank |

Peptide # | Sequence | iTopia Epitope Discovery System | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Binding |

t

1/2

(H) |

Affinity (ED50) | iScore | |||

| 1 | SLL | SLLMWITQV | 87 | 8.9 | 4. 10−8 | 1.67 |

| 2 | 238 | HILHVSFLA | 87 | 6.7 | 6.10−8 | 1.43 |

| 3 | VLP | VLPDVFIRC | 91 | 8.4 | 1. 10−7 | 1.34 |

| 4 | NLS | NLSASVATV | 74 | 8.5 | 4. 10−7 | 1.02 |

| 5 | 355 | VIAALLFCL | 59 | 5.2 | 3.10−8 | 0.89 |

| 6 | 354 | GVIAALLFC | 61 | 6.2 | 9.10−8 | 0.85 |

| 7 | 80 | ALLHSKYGL | 87 | 7.8 | 1.10−6 | 0.82 |

| 8 | YMD | YMDGTMSQV | 78 | 9.2 | 9. 10−7 | 0.81 |

| 9 | 351 | VVVGVIAAL | 58 | 3.4 | 3.10−8 | 0.78 |

| 10 | 145 | VLVPPLPSL | 67 | 6.8 | 8.10−7 | 0.78 |

| 11 | KVA | KVAELVHFL | 78 | 6.2 | 4. 10−7 | 0.77 |

| 12 | GLY | GLYDGMEHL | 71 | 7.6 | 8. 10−7 | 0.74 |

| 13 | 21 | LLASFTGRC | 91 | 6.0 | 6.10−7 | 0.73 |

| 14 | 358 | ALLFCLLVV | 53 | 6.1 | 2.10−7 | 0.71 |

| 15 | 347 | SASVVVVGV | 64 | 3.7 | 2.10−7 | 0.71 |

| 16 | 215 | SMNGQPLTC | 81 | 6.8 | 7.10−7 | 0.70 |

| 17 | 359 | LLFCLLVVV | 67 | 7.4 | 5.10−7 | 0.67 |

| 18 | 266 | AMLKCLSEG | 74 | 6.8 | 7.10−7 | 0.67 |

| 19 | 137 | FQARLRLRV | 69 | 7.3 | 8.10−7 | 0.66 |

| 20 | 19 | LLLLASFTG | 75 | 2.1 | 6.10−8 | 0.66 |

| 21 | 345 | LVSASVVVV | 51 | 2.3 | 6.10−8 | 0.63 |

| 22 | 357 | AALLFCLLV | 56 | 3.8 | 1.10−7 | 0.62 |

| 23 | 35 | GTSDVVTVV | 63 | 2.9 | 3.10−7 | 0.54 |

| 24 | 255 | DQNLWHIGR | 62 | 5.4 | 5.10−7 | 0.54 |

| 25 | 244 | FLAEASVRG | 78 | 2.8 | 7.10−7 | 0.53 |

| 26 | 203 | AVTSEFHLV | 64 | 3.5 | 4.10−7 | 0.53 |

| 27 | 433 | RSYSTLTTV | 68 | 2.4 | 3.10−7 | 0.52 |

| 28 | 239 | ILHVSFLAE | 61 | 2.3 | 2.10−7 | 0.51 |

| POS | FLPSDFFPSV | 100 | 8.1 | 1.10−7 | – | |

| NEG | EGEYECRVS | 0 | – | – | – | |

All listed peptides have a calculated iScore higher than 0.50 and are therefore considered to be “good binders” to HLA-A2 molecules. POS and NEG: positive and negative control peptides present in the iTopia kit

Binding to and dissociation from HLA-A2 molecules on T2 cells, and final scoring

T2 cells lack TAP molecules, leading to the presence on the cell surface of HLA-A*02:01 molecules that are not loaded with high-affinity peptides and can be stabilized by the addition of such peptides in the culture medium, which results in a measurable increase in the surface level of HLA-A2 molecules. We used this assay for the 22 “good binders” Nectin-4 peptides.

As shown in Fig. 2a, Nectin-4 peptide #145 lead to an increased level of surface HLA-A2 molecules on T2 cells comparable to that observed with a positive control HBV peptide (Fig. 2b). Peptide #122, with an iScore ≤0.25, did not increase HLA-A2 surface expression (Fig. 2a).

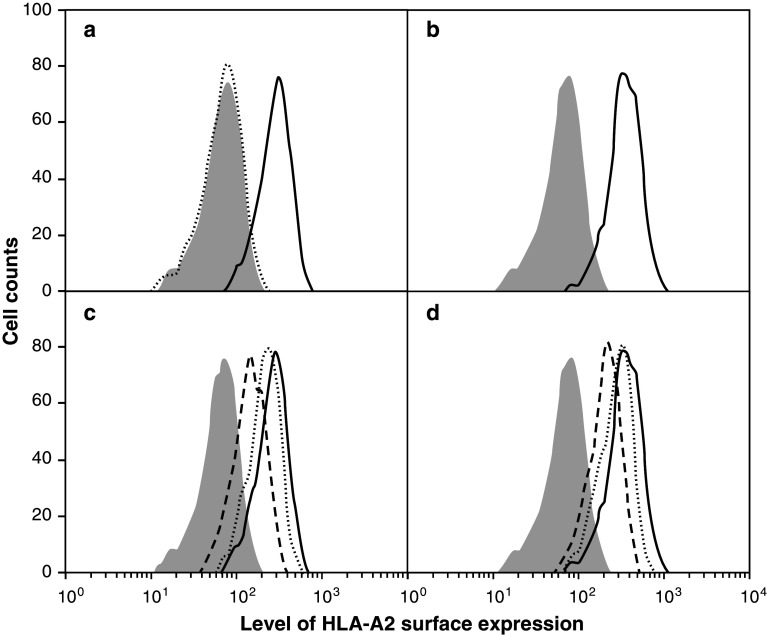

Fig. 2.

HLA stabilization assays using T2 cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Examples of binding and dissociation histograms of Nectin-4 and HBV (positive control) peptides. a Levels of HLA-A2 on T2 cells without peptide (dotted histogram) or with Nectin-4 peptides #145 (solid line) and #122 (gray) at 100 µM. Peptides were tested at 1, 10 and 100 µM; increases of HLA-A2 surface expression were also observed at 10 µM but they were always smaller than at 100 µM. b Levels of HLA-A2 on T2 cells either without peptide (grey histogram) or with the HBV peptide as positive control (solid line). c Kinetics of dissociation of Nectin-4 peptide #145: T0 h (solid line), T1 h (dotted line), T4 h (dashed line). The grey histogram represents T2 cells incubated with Nectin-4 peptide #122, which does not bind to HLA-A2. d Kinetics of dissociation of the HBV peptide. The results are representative of at least three independent experiments

The stability of peptide binding to HLA-A2 molecules was evaluated with dissociation assays performed on T2 cells in the presence of Brefeldin A, as described in Materials and Methods. Results obtained for peptide #145 and control HBV peptide are shown on Fig. 2c, d, respectively. Table 2 shows the T2 binding and dissociation results for the 22 Nectin-4 peptides selected as good binders according to their iScore. Of these, only peptides #80, #145 and #351 had a binding score and a residual binding on T2 cells that were ≥50 % of those of the positive control peptide.

Table 2.

Results of binding to and dissociation from surface HLA-A2 molecules for Nectin-4 peptides and for reference and control peptides

| Peptide# | Sequence | iTopia | T2 cells | Predicted binding to HLA-A2, computed with : | BIMAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iScore | % Binding | % Residual binding | SYFPEITHI | |||

| 19 | LLLLASFTG | 0.66 | 17 | 0 | 16 | 2 |

| 21 | LLASFTGRC | 0.73 | 44 | 86 | 17 | 4 |

| 35 | GTSDVVTVV | 0.54 | 60 | 0 | 20 | 3 |

| 80 | ALLHSKYGL | 0.82 | 53 | 86 | 26 | 79 |

| 137 | FQARLRLRV | 0.60 | 30 | 72 | 13 | 32 |

| 145 | VLVPPLPSL | 0.78 | 76 | 54 | 31 | 83 |

| 203 | AVTSEFHLV | 0.53 | 48 | 0 | 16 | 11 |

| 215 | SMNGQPLTC | 0.69 | 21 | 0 | 16 | 3 |

| 238 | HILHVSFLA | 1.43 | 37 | 66 | 14 | 0 |

| 239 | ILHVSFLAE | 0.51 | 10 | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| 244 | FLAEASVRG | 0.53 | 12 | 0 | 17 | 1 |

| 255 | DQNLWHIGR | 0.54 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 266 | AMLKCLSEG | 0.67 | 31 | 39 | 18 | 0 |

| 345 | LVSASVVVV | 0.63 | 11 | 0 | 22 | 9 |

| 347 | SASVVVVGV | 0.71 | 40 | 0 | 23 | 2 |

| 351 | VVVGVIAAL | 0.78 | 82 | 50 | 24 | 7 |

| 354 | GVIAALLFC | 0.85 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 5 |

| 355 | VIAALLFCL | 0.89 | 18 | 24 | 26 | 66 |

| 357 | AALLFCLLV | 0.62 | 15 | 18 | 20 | 13 |

| 358 | ALLFCLLVV | 0.71 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 242 |

| 359 | LLFCLLVVV | 0.67 | 7 | 23 | 30 | 412 |

| 433 | RSYSTLTTV | 0.52 | 37 | 0 | 17 | 3 |

| SLL | SLLMWITQV | 1.67 | 68 | 70 | 28 | 592 |

| VLP | VLPDVFIRC | 1.34 | 60 | 91 | 12 | 66 |

| NLS | NLSAVATV | 1.02 | 45 | 41 | 28 | 160 |

| YMD | YMDGTMSQV | 0.81 | 63 | 82 | 22 | 212 |

| KVA | KVAELVHFL | 0.77 | 55 | 63 | 25 | 339 |

| GLY | GLYDGMEHL | 0.74 | 55 | 71 | 25 | 315 |

| POS | FLPSDFFPSV | – | 100 | 91 | 24 | 2309 |

| NEG | EGEYECRVS | 0 | 0 | −5 | 0 | |

List of the Nectin-4 peptides selected as “good binders” with the iTopia assay, with the results of binding to and dissociation from HLA-A2 molecules on T2 cells. Peptides are listed according to their position in the Nectin-4 protein. The SYFPEITHI and BIMAS algorithms were used to compute scores of predicted binding of peptides to HLA-A*02:01 molecules

To integrate the results obtained with iTopia and with T2 cells, we defined an F-score, the sum of the peptide ranks for iScore, T2 binding and T2 dissociation. We then ranked the 22 Nectin-4 peptides (Tables 1, 2) and the nine reference peptides (Fig. 1a) according to this F-score and show on Table 3 the scoring of the best five Nectin-4 peptides. Peptides #80, #351, #145 and #238 are ranked to the fourth–seventh positions, flanked by reference peptides known to be presented to T cells by HLA-A2 molecules. These results suggest that these Nectin-4 peptides, if processed in cells, should be presented by HLA-A2 molecules.

Table 3.

Ranking of the best five Nectin-4 peptides selected on the basis of their F-score

| Rank F-score |

F-score | Peptide | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | VLPDVFIRC | GnT-V |

| 2 | 11 | SLLMWITQV | NY-ESO-1 |

| 3 | 18 | YMDGTMSQV | Tyrosinase |

| 4 | 19 | ALLHSKYGL | Nectin-4 #80 |

| 5 | 21 | VVVGVIAAL | Nectin-4 #351 |

| 6 | 22 | VLVPPLPSL | Nectin-4 #145 |

| 7 | 25 | HILHVSFLA | Nectin-4 #238 |

| 7 | 25 | GLYDGMEHL | MAGEA10 |

| 9 | 27 | NLSASVATV | Proteinase 3 |

| 10 | 28 | KVAELVHFL | MAGEA3 |

| 11 | 30 | LLASFTGRC | Nectin-4 #21 |

F-score is the sum of the peptide ranks for iScore, T2 binding and T2 dissociation. Nectin-4 peptides are compared with the reference peptides listed in Fig. 1a

Generation of anti-Nectin-4 cytolytic T cells

The demonstration that an HLA class I-binding peptide is an antigenic peptide present at the cell surface requires either its identification in the pool of peptides eluted from surface HLA molecules, or its recognition by peptide-specific T lymphocytes on cells that express the corresponding HLA allele and antigen-encoding gene. Here, we followed the second approach for Nectin-4 peptides #21, #80, #145 and #351.

We first tried to derive anti-Nectin-4 CD8+ T cells from the PBMCs of healthy donors. As outlined in Fig. 3a, we magnetically enriched PBMCs for T cells labeled with HLA-A2 multimers loaded with the Nectin-4 peptides, and stimulated these cells in limiting dilution conditions with autologous mature dendritic cells pulsed with the peptides. Three weeks later, the cells of all microcultures were labeled with the Nectin-4/HLA-A2 multimers. Examples of positive microcultures that contained small frequencies of multimer+ cells are shown on Fig. 3a. Positive microcultures that contained high frequencies of multimer+ cells are shown on Fig. 3b. From such microcultures, the multimer cells could be sorted and tested for their lytic capacity. Target cells were the HLA-A2+ breast carcinoma cells MDA-MB-231, which do not express gene PVRL4, and MDA-MB-231 cells stably transfected with a PVRL4 construct. It is of note that the level of PVRL4 expression in the transfected cells was below that observed in most breast tumor cell lines (data not shown). The sorted multimer+ cells lyzed the parental MDA-MB-231 cells, provided that the tumor cells were pulsed with the relevant Nectin-4 peptide (Fig. 3b). Only one population, recognizing peptide #145, could lyze the transfected tumor cells without exogenous peptide (Fig. 3b). This result suggested that Nectin-4 peptide #145 was naturally processed from the protein in the tumor cells. However, the multimer+ cells proliferated poorly and we could not derive T cell clones to confirm this result.

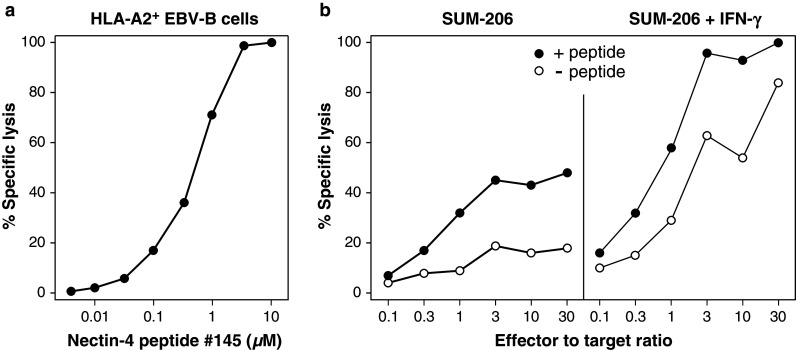

Next, we tried to derive a CTL clone recognizing Nectin-4 peptide #145 by including this peptide in a screening of PBMCs from 26 HLA-A2+ breast cancer patients for anti-tumor CD8+ T cells. The assay consisted in a stimulation of PBMCs over 2 weeks in limiting dilution conditions (2 × 105 PBMCs per microculture) with a pool of seven tumor-specific antigenic peptides known to bind to HLA-A2 molecules, followed by a detection of peptide-specific T cells in all microcultures with multimers. For one patient, P88, 4 out of 150 microcultures contained CD8+ cells stained with the HLA-A2 multimer loaded with peptide #145. Thus, the minimal frequency of blood anti-Nectin-4#145 T cells in this patient was 8.9 × 10−7 of the CD8+ T cells (with 15 % of CD3+CD8+ cells in the PBMCs). The multimer-positive cells were cloned with flow cytometry and restimulated with feeder cells and HLA-A2+ EBV-B cells pulsed with peptide #145. From one cell population that expressed a single TCR and that we named clone P88-40 we obtained enough cells to carry out several lysis assays. CTL clone P88-40 lyzed HLA-A2+ EBV-B cells pulsed with several doses of peptide #145, with half-maximal effect at 500 nM (Fig. 4a). No lysis was observed with peptide-pulsed EBV-B cells that did not express HLA-A2 (data not shown). The clone lyzed cells of the HLA-A2+ Nectin-4+ breast carcinoma cell line SUM-206 (Fig. 4b). This lysis was increased when the tumor cells were pretreated with IFN-γ (Fig. 4b). As expected, lysis was increased when the tumor cells were pulsed with peptide #145 (Fig. 4b). No lysis was observed with HLA-A2- Nectin-4+ tumor cell line BT-474, treated or not with IFN-γ and pulsed or not with peptide (data not shown). These results confirmed that Nectin-4 antigenic peptide #145 can be naturally processed in tumor cells and presented to CTLs by HLA-A2 molecules.

Fig. 4.

Lytic activity of CTL clone P88-40 recognizing peptide Nectin-4 #145. a Lysis of HLA-A2+ EBV-B cells pulsed with the indicated concentrations of Nectin-4 peptide #145. Half-maximal lysis was obtained with the antigenic peptide at 500 nM. Effector to target ratio was 30:1. b Lysis of HLA-A2+ Nectin-4+ breast carcinoma cells SUM-206, pretreated or not over 72 h with 100 U/ml of IFN-γ, and pulsed or not with peptide #145 at 1 µM. These results are representative of at least two experiments. Lysis assays were carried out in triplicate

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify Nectin-4 antigenic peptides that could be presented by tumor cells to HLA-A2-restricted CTLs. We used the high-throughput technology iTopia Epitope Discovery System to screen a library of 502 Nectin-4 nonamers spanning the whole length of the protein. The choice of peptides with nine amino acids is based on experiments of elution of antigenic peptides from HLA class I molecules, in which the majority of peptides contain nine amino acids. However, it would be interesting to carry out iTopia screenings of Nectin-4 peptides with 8, 10 or 11 amino acids, as tumor-specific CTLs have been shown to recognize antigenic peptides of these lengths. We found more “binder” peptides for HLA-A*02:01, HLA-A*24:02 and HLA-B*15:01 than for HLA-A*01:01. This is in accordance with previous data obtained with the iTopia technology [38, 39].

Nectin-4 peptides that were predicted to bind to HLA-A*02:01 were tested with biochemical, cellular and in silico assays. Peptide binding to and dissociation from HLA-A2 were assayed in vitro with iTopia and in cellulo with the TAP-deficient cell line T2. The results were usually concordant. They were combined into an “F-score” and compared with the HLA binding predicted by the SYFPEITHI [40] or BIMAS [41] algorithms (Table 2). There were some discrepancies, even though most of the peptides with a high F-score had a high SYFPEITHI score. Out of 502 peptides, 21 had a SYFPEITHI score ≥20 for HLA-A*02:01. However, for 11 out of these 21 peptides, we could not detect binding to HLA-A2 molecules, neither in the biochemical nor in the cellular assay. Conversely, we found peptides with a low SYFPEITHI score and a high F-score, such as peptide #21 which has a C-terminal Cys residue. These results exemplify the limitations of HLA/peptide binding analyzes based only on algorithmic predictions.

By stimulating blood mononuclear cells from HLA-A2+, healthy donors with four peptides that could bind to HLA-A2, we derived populations of CD8+ T cells that were stained with the relevant HLA-A2/peptide multimer. Thus CD8+ T cells recognizing Nectin-4 peptides are present in the human adult T cell repertoire. We cannot exclude that low levels of expression of gene PVRL4 lead to partial tolerance through the deletion or functional inactivation of high-affinity anti-Nectin-4 CD8+ T cells. Noteworthy, the stimulation protocol that we used in these experiments included mature dendritic cells, which can prime naive CD8+ T cells in vitro. Therefore, the results did not provide any information on the possibility of spontaneous anti-Nectin-4 T cell responses in vivo.

To explore this possibility, we stimulated blood T cells from breast cancer patients with peptide Nectin-4145–153, using a method that does not include dendritic cells and therefore should not prime naive T cells but can restimulate antigen-experienced T lymphocytes. We tested the PBMCs of 26 HLA-A2 patients and detected anti-Nectin-4 T cells in a single patient. The estimated frequency of the anti-Nectin-4145–153 T cells in the blood of this patient, around 10−6 of the CD8+ T cells, is very low. These results suggest that in breast cancer patients spontaneous T cells responses to peptide Nectin-4145–153 are rare and of low magnitude.

From the anti-Nectin-4145–153 T cells of patient P88, we could derive a CTL clone that proliferated enough to carry out several lysis assays. This clone recognized peptide Nectin-4145–153 and lyzed breast carcinoma cells that naturally expressed the HLA-A*02:01 and PVRL4 genes. Thus, peptide Nectin-4145–153 is naturally processed in these cells.

Altogether our results suggest that sufficient numbers of functional anti-Nectin-4145–153 CTLs could mediate regressions of Nectin-4-positive tumors such as breast carcinomas. A few tumor-associated antigens have been described that could be used safely to stimulate antitumor T cells in patients with breast cancer. They include peptides encoded by genes ERBB2 and MUC1, overexpressed in some breast carcinomas as compared to normal breast tissues [42]. Nectin-4 could be an interesting source of antigens in tumors that express neither ERBB2 nor MUC1.

The incidence of spontaneous T cell responses to peptide Nectin-4145–153 is not known. We have screened 26 breast cancer patients with a set of candidate tumor antigens including this peptide and observed specific T cells in a single patient. It would be interesting to look for these cells in patients treated with immunostimulatory antibodies blocking the PD-1 pathway. The spontaneous immunogenicity of peptide Nectin-4145–153 appears to be low. The results warrant trials of active or passive immunization of cancer patients against peptide Nectin-4145–153, combined with immunostimulatory antibodies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from INSERM, Institut Paoli-Calmettes, Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, Institut National du Cancer (AO projet libre, 2008–2010), and Fondation contre le Cancer (Brussels, Belgium).

Abbreviations

- CTL

Cytolytic T lymphocyte

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- EBV-B

B cells transformed by the Epstein–Barr virus

- ERBB2

Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- GnT-V

N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- MAGEA3

Melanoma antigen family A3

- MAGEA10

Melanoma antigen family A10

- MAGEC2

Melanoma antigen family C2

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- MUC1

Mucin 1

- NY-ESO-1

New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1

- PRAME

Preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma

- PVRL4

Poliovirus receptor-related 4

- TAP

Transporter associated with antigen processing

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sliwkowski MX, Mellman I. Antibody therapeutics in cancer. Science. 2013;341(6151):1192–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1241145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, Boon T. Tumour antigens recognized by T lymphocytes: at the core of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(2):135–146. doi: 10.1038/nrc3670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabre-Lafay S, Monville F, Garrido-Urbani S, Berruyer-Pouyet C, Ginestier C, Reymond N, Finetti P, Sauvan R, Adelaide J, Geneix J, Lecocq E, Popovici C, Dubreuil P, Viens P, Goncalves A, Charafe-Jauffret E, Jacquemier J, Birnbaum D, Lopez M. Nectin-4 is a new histological and serological tumor associated marker for breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reymond N, Fabre S, Lecocq E, Adelaide J, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. Nectin4/PRR4, a new afadin-associated member of the nectin family that trans-interacts with nectin1/PRR1 through V domain interaction. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(46):43205–43215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabre-Lafay S, Garrido-Urbani S, Reymond N, Goncalves A, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. Nectin-4, a new serological breast cancer marker, is a substrate for tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (TACE)/ADAM-17. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(20):19543–19550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takai Y, Ikeda W, Ogita H, Rikitake Y. The immunoglobulin-like cell adhesion molecule nectin and its associated protein afadin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:309–342. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takai Y, Nakanishi H. Nectin and afadin: novel organizers of intercellular junctions. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 1):17–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reymond N, Imbert AM, Devilard E, Fabre S, Chabannon C, Xerri L, Farnarier C, Cantoni C, Bottino C, Moretta A, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. DNAM-1 and PVR regulate monocyte migration through endothelial junctions. J Exp Med. 2004;199(10):1331–1341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takai Y, Miyoshi J, Ikeda W, Ogita H. Nectins and nectin-like molecules: roles in contact inhibition of cell movement and proliferation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(8):603–615. doi: 10.1038/nrm2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pende D, Bottino C, Castriconi R, Cantoni C, Marcenaro S, Rivera P, Spaggiari GM, Dondero A, Carnemolla B, Reymond N, Mingari MC, Lopez M, Moretta L, Moretta A. PVR (CD155) and Nectin-2 (CD112) as ligands of the human DNAM-1 (CD226) activating receptor: involvement in tumor cell lysis. Mol Immunol. 2005;42(4):463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuramochi M, Fukuhara H, Nobukuni T, Kanbe T, Maruyama T, Ghosh HP, Pletcher M, Isomura M, Onizuka M, Kitamura T, Sekiya T, Reeves RH, Murakami Y. TSLC1 is a tumor-suppressor gene in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2001;27(4):427–430. doi: 10.1038/86934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brancati F, Fortugno P, Bottillo I, Lopez M, Josselin E, Boudghene-Stambouli O, Agolini E, Bernardini L, Bellacchio E, Iannicelli M, Rossi A, Dib-Lachachi A, Stuppia L, Palka G, Mundlos S, Stricker S, Kornak U, Zambruno G, Dallapiccola B. Mutations in PVRL4, encoding cell adhesion molecule nectin-4, cause ectodermal dysplasia-syndactyly syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87(2):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muhlebach MD, Mateo M, Sinn PL, Prufer S, Uhlig KM, Leonard VH, Navaratnarajah CK, Frenzke M, Wong XX, Sawatsky B, Ramachandran S, McCray PB, Jr, Cichutek K, von Messling V, Lopez M, Cattaneo R. Adherens junction protein nectin-4 is the epithelial receptor for measles virus. Nature. 2011;480(7378):530–533. doi: 10.1038/nature10639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campadelli-Fiume G, Cocchi F, Menotti L, Lopez M. The novel receptors that mediate the entry of herpes simplex viruses and animal alphaherpesviruses into cells. Rev Med Virol. 2000;10(5):305–319. doi: 10.1002/1099-1654(200009/10)10:5<305::AID-RMV286>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derycke MS, Pambuccian SE, Gilks CB, Kalloger SE, Ghidouche A, Lopez M, Bliss RL, Geller MA, Argenta PA, Harrington KM, Skubitz AP. Nectin 4 overexpression in ovarian cancer tissues and serum: potential role as a serum biomarker. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(5):835–845. doi: 10.1309/AJCPGXK0FR4MHIHB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takano A, Ishikawa N, Nishino R, Masuda K, Yasui W, Inai K, Nishimura H, Ito H, Nakayama H, Miyagi Y, Tsuchiya E, Kohno N, Nakamura Y, Daigo Y. Identification of nectin-4 oncoprotein as a diagnostic and therapeutic target for lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(16):6694–6703. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabre S, Reymond N, Cocchi F, Menotti L, Dubreuil P, Campadelli-Fiume G, Lopez M. Prominent role of the Ig-like V domain in trans-interactions of nectins. Nectin3 and nectin 4 bind to the predicted C-C’-C”-D beta-strands of the nectin1 V domain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(30):27006–27013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guilloux Y, Lucas S, Brichard VG, Van Pel A, Viret C, De Plaen E, Brasseur F, Lethé B, Jotereau F, Boon T. A peptide recognized by human cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas is encoded by an intron sequence of the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V gene. J Exp Med. 1996;183(3):1173–1183. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawashima I, Hudson S, Tsai V, Southwood S, Takesako K, Appella E, Sette A, Celis E. The multi-epitope approach for immunotherapy for cancer: identification of several CTL epitopes from various tumor-associated antigens expressed on solid epithelial tumors. Hum Immunol. 1998;59:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(97)00255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang L-Q, Brasseur F, Serrano A, De Plaen E, van der Bruggen P, Boon T, Van Pel A. Cytolytic T lymphocytes recognize an antigen encoded by MAGE-A10 on a human melanoma. J Immunol. 1999;162:6849–6854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma W, Germeau C, Vigneron N, Maernoudt A-S, Morel S, Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde B. Two new tumor-specific antigenic peptides encoded by gene MAGE-C2 and presented to cytolytic T lymphocytes by HLA-A2. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:698–702. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma W, Vigneron N, Chapiro J, Stroobant V, Germeau C, Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ. A MAGE-C2 antigenic peptide processed by the immunoproteasome is recognized by cytolytic T cells isolated from a melanoma patient after successful immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2427–2434. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rimoldi D, Rubio-Godoy V, Dutoit V, Liénard D, Salvi S, Guillaume P, Speiser D, Stockert E, Spagnoli G, Servis C, Cerottini J-C, Lejeune F, Romero P, Valmori D. Efficient simultaneous presentation of NY-ESO-1/LAGE-1 primary and nonprimary open reading frame-derived CTL epitopes in melanoma. J Immunol. 2000;165:7253–7261. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda H, Lethé B, Lehmann F, Van Baren N, Baurain J-F, De Smet C, Chambost H, Vitale M, Moretta A, Boon T, Coulie PG. Characterization of an antigen that is recognized on a melanoma showing partial HLA loss by CTL expressing an NK inhibitory receptor. Immunity. 1997;6(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molldrem JJ, Clave E, Jiang YZ, Mavroudis D, Raptis A, Hensel N, Agarwala V, Barrett AJ. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for a nonpolymorphic proteinase 3 peptide preferentially inhibit chronic myeloid leukemia colony-forming units. Blood. 1997;90(7):2529–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wölfel T, Van Pel A, Brichard V, Schneider J, Seliger B, Meyer zum Büschenfelde K-H, Boon T. Two tyrosinase nonapeptides recognized on HLA-A2 melanomas by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:759–764. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doytchinova IA, Walshe VA, Jones NA, Gloster SE, Borrow P, Flower DR. Coupling in silico and in vitro analysis of peptide-MHC binding: a bioinformatic approach enabling prediction of superbinding peptides and anchorless epitopes. J Immunol. 2004;172(12):7495–7502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nijman HW, Houbiers JG, Vierboom MP, van der Burg SH, Drijfhout JW, D’Amaro J, Kenemans P, Melief CJ, Kast WM. Identification of peptide sequences that potentially trigger HLA-A2.1-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(6):1215–1219. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serody JS, Collins EJ, Tisch RM, Kuhns JJ, Frelinger JA. T cell activity after dendritic cell vaccination is dependent on both the type of antigen and the mode of delivery. J Immunol. 2000;164(9):4961–4967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strous GJ, van Kerkhof P, van Meer G, Rijnboutt S, Stoorvogel W. Differential effects of brefeldin A on transport of secretory and lysosomal proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(4):2341–2347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DiBrino M, Tsuchida T, Turner RV, Parker KC, Coligan JE, Biddison WE. HLA-A1 and HLA-A3 T cell epitopes derived from influenza virus proteins predicted from peptide binding motifs. J Immunol. 1993;151(11):5930–5935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baurain J-F, Colau D, van Baren N, Landry C, Martelange V, Vikkula M, Boon T, Coulie PG. High frequency of autologous anti-melanoma CTLs directed against an antigen generated by a point mutation in a new helicase gene. J Immunol. 2000;164:6057–6066. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.6057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garboczi DN, Hung DT, Wiley DC. HLA-A2-peptide complexes: refolding and crystallization of molecules expressed in Escherichia coli and complexed with single antigenic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(8):3429–3433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boccaccio C, Jacod S, Kaiser A, Boyer A, Abastado JP, Nardin A. Identification of a clinical-grade maturation factor for dendritic cells. J Immunother. 2002;25(1):88–96. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ottaviani S, Zhang Y, Boon T, van der Bruggen P. A MAGE-1 antigenic peptide recognized by human cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 tumor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:1214–1220. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0705-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karanikas V, Lurquin C, Colau D, van Baren N, De Smet C, Lethé B, Connerotte T, Corbière V, Demoitié M-A, Liénard D, Dréno B, Velu T, Boon T, Coulie PG. Monoclonal anti-MAGE-3 CTL responses in melanoma patients displaying tumor regression after vaccination with a recombinant canarypox virus. J Immunol. 2003;171(9):4898–4904. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Godelaine D, Carrasco J, Lucas S, Karanikas V, Schuler-Thurner B, Coulie PG, Schuler G, Boon T, Van Pel A. Polyclonal CTL responses observed in melanoma patients vaccinated with dendritic cells pulsed with a MAGE-3.A1 peptide. J Immunol. 2003;171(9):4893–4897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bachinsky MM, Guillen DE, Patel SR, Singleton J, Chen C, Soltis DA, Tussey LG. Mapping and binding analysis of peptides derived from the tumor-associated antigen survivin for eight HLA alleles. Cancer Immun. 2005;5:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shingler WH, Chikoti P, Kingsman SM, Harrop R. Identification and functional validation of MHC class I epitopes in the tumor-associated antigen 5T4. Int Immunol. 2008;20(8):1057–1066. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thome JJ, Yudanin N, Ohmura Y, Kubota M, Grinshpun B, Sathaliyawala T, Kato T, Lerner H, Shen Y, Farber DL. Spatial map of human T cell compartmentalization and maintenance over decades of life. Cell. 2014;159(4):814–828. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J Immunol. 1994;152(1):163–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vigneron N, Stroobant V, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. Database of T cell-defined human tumor antigens: the 2013 update. Cancer Immun. 2013;13:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]