Abstract

Increased numbers of immunosuppressive myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) correlate with a poor prognosis in cancer patients. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are used as standard therapy for the treatment of several neoplastic diseases. However, TKIs not only exert effects on the malignant cell clone itself but also affect immune cells. Here, we investigate the effect of TKIs on the induction of MDSCs that differentiate from mature human monocytes using a new in vitro model of MDSC induction through activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). We show that frequencies of monocytic CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs derived from mature monocytes were significantly and dose-dependently reduced in the presence of dasatinib, nilotinib and sorafenib, whereas sunitinib had no effect. These regulatory effects were only observed when TKIs were present during the early induction phase of MDSCs through activated HSCs, whereas already differentiated MDSCs were not further influenced by TKIs. Neither the MAPK nor the NFκB pathway was modulated in MDSCs when any of the TKIs was applied. When functional analyses were performed, we found that myeloid cells treated with sorafenib, nilotinib or dasatinib, but not sunitinib, displayed decreased suppressive capacity with regard to CD8+ T cell proliferation. Our results indicate that sorafenib, nilotinib and dasatinib, but not sunitinib, decrease the HSC-mediated differentiation of monocytes into functional MDSCs. Therefore, treatment of cancer patients with these TKIs may in addition to having a direct effect on cancer cells also prevent the differentiation of monocytes into MDSCs and thereby differentially modulate the success of immunotherapeutic or other anti-cancer approaches.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-015-1790-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Myeloid derived suppressor cells, Immunomodulation, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Cancer immunotherapy often fails to induce a sufficient immune response that is able to eradicate the targeted neoplasia. Taking into account that immunosuppression is a major contributor toward tumor progression, an ideal immunotherapy should not only induce strong and effective anti-tumor immune responses, but also eliminate suppressive factors. Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are major players in the suppression of the immune system and therefore represent excellent targets to enhance immunotherapy [1–6].

MDSCs are primarily known as negative regulators of the immune system: they accumulate in the blood, bone marrow and spleen of cancer patients and in other pathological settings and promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment [5, 7–9]. They are associated with the suppression of T cell responses, the induction of regulatory T cells and a poor prognosis in cancer patients [10]. MDSCs mediate their immune-suppressive activities through the up-regulation of arginase-1, inducible nitric oxide synthase as well as the production of reactive nitrogen species and reactive oxygen species [1, 11, 12]. MDSCs represent a heterogenic population of myeloid cells that resemble either granulocytes or monocytes. In mice, MDSCs can be defined as CD11b+Ly-6G+Ly-6Clow (Gr-1high) and CD11b+Ly-6G−Ly-6Chigh (Gr-1low), respectively. In humans, MDSCs generally express CD33, however, different types of tumors show distinct MDSC subsets [13]. These can roughly be divided into three groups, LIN−HLA-DR−/low, CD14+HLA-DR−/low and CD15+HLA-DR−/low [14]. However, no uniform classification of MDSCs has been established so far.

To decrease or abolish MDSC-mediated immunosuppression, different strategies are possible, e.g., interference with MDSC expansion, MDSC activation or promotion of myeloid cell differentiation. An increasing number of studies using both in vivo systems like tumor-bearing mice as well as human cancer patients indicate that drugs exploring these distinct strategies are able to decrease not only the number of MDSCs but also increase anti-tumor immune responses and prolong survival [6, 15]. Recently, we were able to induce MDSCs from mature monocytes isolated from healthy donors using activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) [16]. This new model of MDSC induction allows to analyze direct effects on MDSCs and limits further interactions with other cells.

Here we addressed the question whether several treatment strategies already used in clinical settings have an effect on the induction or suppression of monocytic MDSCs. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have become part of the standard treatment of several neoplastic diseases and have significantly changed the course of disease in some of these malignancies, particularly in the case of chronic myeloid leukemia [17, 18]. However, it is well established that TKIs not only exert effects on the malignant cell clone itself but also directly affect immune cells or other healthy cells in these individuals [19–21].

Materials and methods

Isolation of primary cells

Blood was taken from healthy volunteers or patients after obtaining written informed consent. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated using gradient density centrifugation as described previously [22]. CD14+ monocytes were purified using CD14 Microbeads (Miltenyi) and AutoMACS Pro according to manufacturer’s protocol. The purity of CD14+ cells was regularly tested and was about 95 %. CD8 T cells and CD14+ cells were FACSorted using Sony SH800 Cell sorter (Sony Biotechnology Europe, United Kingdom), in some experiments after co-culturing with HSCs.

Cell culture

The hepatic stellate cell line LX2 was cultured in complete medium (DMEM supplemented with 10 % FCS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin). One day before adding CD14+ monocytes, LX2 cells were plated on a poly-l-lysine coated plate (2 × 105 cells/cm2). 5 × 105 monocytes were added to the confluent cell layer and cultured for 3 days. Drugs were added directly to the co-culture on day 0 or at day 2.

Flow cytometry

Apoptosis of HSCs was analyzed using annexin-V staining in combination with 7AAD. The expression of HLA-DR (clone MEM12) on CD14+ cells (clone HCD14), CD44 (clone IM7) on HSCs or proliferation of CD8 T cells (clone HIT8a) was determined by flow cytometry using LSR Fortessa (BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany) or Sony SP6800 (Sony Biotechnology Europe, UK). Specimens were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Suppression assay

CD8 T cells were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with artificial antigen-presenting beads coated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28. Proliferation was measured via the dilution of CFSE. The positive control was defined at 100 % proliferation. Monocytes cultured on HSCs in the absence or presence of drugs were isolated, washed three times and added to the T cells at a ratio of 3:1.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and drugs

Nilotinib was obtained from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), dasatinib from LC Labs, sorafenib from Bayer and sunitinib from Pfizer. Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving the compound in DMSO as follows: nilotinib and dasatinib at 10 mM, sorafenib and sunitinib at 5 mg/ml. Stock solutions were stored at −20 °C. 5-Fluorouracil was purchased from Medac and gemcitabine from Hameln via the University Hospital central pharmacy. Retinoic acid was purchased from Roche, Basel, Germany.

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were prepared as described previously [23]. Protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Perbio Science). For analysis of the activation and/or expression status of p38 or pERK, 20 μg whole-cell lysates were separated on a polyacrylamide gel and transferred on a nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were probed with monoclonal antibodies against actin or p38 as loading control, with pp38 and pERK (all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Leiden, The Netherlands) as described previously [23].

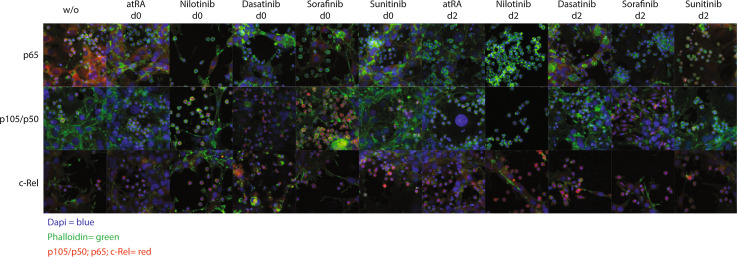

Immunofluorescence

HSCs were cultured on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine and monocytes were added as described in the section “cell culture.” Cells were fixed by adding 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were rinsed twice with PBS supplemented with 5 % BSA and 2 % FCS followed by permeabilization with 0.5 % Triton-X in PBS for 10 min. Cells were stained using anti-NFκB p105/p50 (clone D4P4D), anti-NFκB p65 (clone D14E12) and anti-c-Rel (polyclonal) in PBS supplemented with 5 % BSA and 2 % FCS for 40 min. As secondary antibody PE labeled anti-rabbit IgG was incubated for 40 min. DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) and Phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) were added for 15 min (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Leiden, The Netherlands). Imaging was performed using CLSM700 microscope (Zeiss, Munich, Germany).

Statistics

All experiments were performed with 3–6 donors per group, and results were calculated from three independent experiments and plotted as SEM. Statistical significance was calculated using ANOVA or Student’s t test (*p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001).

Results

Monocytes cultured on HSCs acquire a MDSC phenotype and immune-suppressive function, which can be inhibited by the addition of distinct therapeutic compounds

MDSCs comprise a group of myeloid cells that are known to promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment. While MDSCs can highly confound anti-tumor immune responses, they also exert positive effects in clinical situations where immunosuppression is warranted, e.g., in the setting of graft versus host disease or other autoimmune diseases. It is compelling to define specific protocols that help to induce or to eliminate MDSCs. However, in general, most patients are treated with specific drugs without knowing possible interactions or effects of these compounds on MDSCs. TKIs are currently used in a huge, heterogeneous population of patients and are usually applied over a long period of time. We therefore wanted to investigate a possible modulation of MDSCs mediated by TKIs.

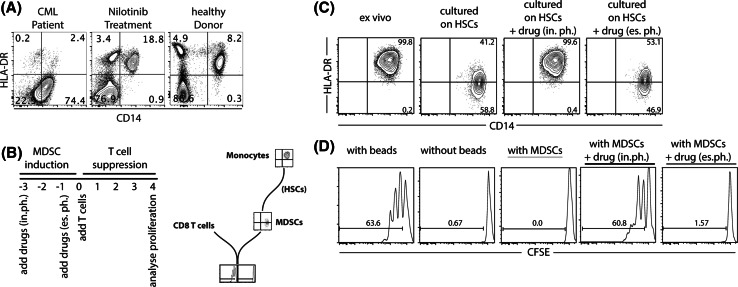

We have repeatedly observed changes in MDSC frequencies in patients under TKI treatment. As seen in Fig. 1a, we have performed a CD14/HLA-DR staining in one exemplary chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patient, in chronic phase without peripheral blasts, just before and 1 week after nilotinib treatment had been initiated and compared the results with a healthy donor. We observed a drastic reduction of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells and a normalization of the plotted cells 1 week after the TKI treatment had been started (Fig. 1a). This observation is similar to reports from other groups who have also described a modulation of MDSCs under TKI treatment [24–26]. Although our data are very limited, our observations provoked the question whether TKIs directly affect MDSCs or whether further effects on other immune or bystander cells occur that rather indirectly modulate MDSC frequencies.

Fig. 1.

Addition of distinct therapeutic compounds to monocytes cultured on HSCs results in modulated MDSC induction. PBMCs from a patient suffering from CML were stained for CD14/HLA-DR just before and 1 week after treatment with nilotinib was initiated and compared to a healthy volunteer (a). Timeline and graphical diagram of the experimental setup. CD14+ cells were cultured on hepatic stellate cell line LX2 for 3 days. Drugs were added directly to the co-culture; (referred to as induction phase, in.ph.) or 2 days after start of co-culture (referred to as established phase, es. ph.) (b). Analysis diagram of MDSC induction: down-regulation of HLA-DR on CD14+ cells as a marker for MDSCs (c) and suppressive capacity of MDSCs (d)

Given the high diversity of human MDSCs, we focused on addressing the modulation of monocytic CD14+HLA-DR−/low MDSCs transdifferentiated from monocytes (diagram Fig. 1b). We have previously shown that human monocytes cultured on HSCs for 3 days down-regulate HLA-DR (Fig. 1c) and acquire the capability to suppress T cells (Fig. 1d). The CD14+HLA-DR−/low phenotype combined with their suppressive potential indicates that these monocytes have differentiated into MDSCs. This new in vitro model of MDSC induction through HSCs allows us to analyze direct effects of TKIs on MDSCs and limits further interactions with other cells.

To test the effect of different therapeutic compounds on MDSC induction, we incubated monocytes from healthy donors on HSCs in the presence of these drugs. We discriminated two different strategies of drug application (Fig. 1b): they were either added on the first day of culture, day 0 (referred to as induction phase, in.ph.) or on day 2 when MDSC induction usually has already taken place (referred to as established phase, es. ph.).

Cells were harvested on day 3 of culture and stained for CD14 and HLA-DR for phenotypic characterization. Functional analysis was performed by co-culturing the isolated, differentially treated CD14+ cells with activated T cells.

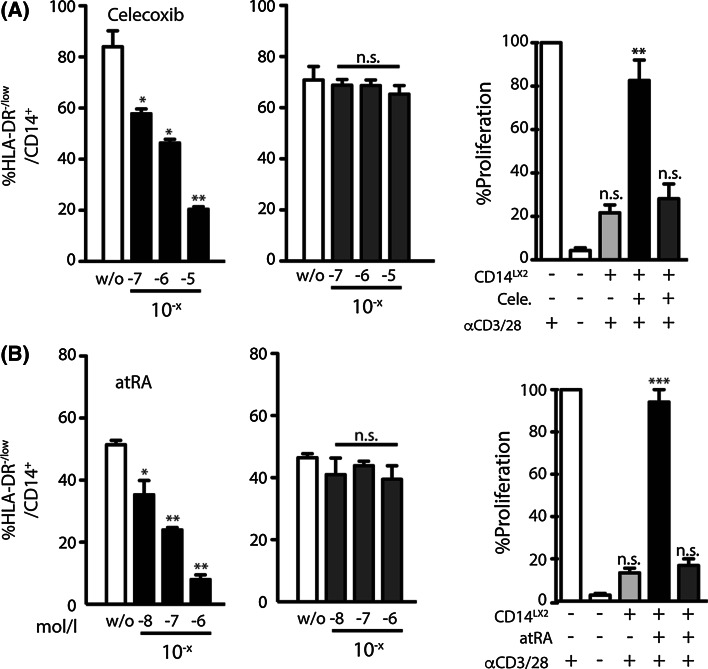

Cyclooxygenase inhibitor celecoxib as well as all-trans-retinoic acid reduce frequencies of HSC-induced MDSCs

It has been reported that the cyclooxygenase inhibitor celecoxib as well as all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) reduce frequencies of MDSCs [11, 27]. Therefore, we tested this effect in our system. Indeed, the addition of celecoxib (Fig. 2a) or atRA (Fig. 2b) resulted in a dose-dependent reduction of HSC-mediated MDSCs induction. However, this effect was only apparent if the compounds were added on day 0 during the induction phase and not observed if the drugs were added at later time points during the established phase. This effect might indicate that during the early induction of MDSCs, monocytes harbor a strong plasticity that is partially lost after initial differentiation signals have been received. We next analyzed the immunosuppressive potential of these differentially cultured cells with regard to T cell inhibition. CD14+ cells harvested from HSC co-cultures in the absence of any of the compounds almost entirely suppressed CD8 T cell proliferation (Fig. 2a, b, light gray columns), whereas cells cultured in the presence of either celecoxib or atRA showed far less T cell suppressive capacity (Fig. 2a, b, black columns). Again, this decrease in T cell suppression was only found when the compounds were added on day 0 and not in the established phase (Fig. 2a, b, dark gray columns).

Fig. 2.

Cyclooxygenase inhibitor celecoxib as well as all-trans-retinoic acid reduce frequencies of HSC-induced MDSCs. Cells were treated as described in Fig. 1. Celecoxib (a) or atRA (b) were added directly or after 2 days (Celecoxib without; 10−7; 10−6; 10−5 mol/L or atRA without; 10−8; 10−7; 10−6 mol/L accordingly). Reduction of MDSC induction was measured by HLA-DR down-regulation with drugs added on day 0 (left graph in black) or on day 2 (middle graph in dark gray). Suppressive capacity of MDSCs treated directly (right graph, back column) or after 2 days (dark gray) was measured by the inhibition of anti-CD3/anti-CD28 activated T cells, whereas T cells alone were set to 100 % (first white column). T cells without stimulation were used as control (second white column). *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant

Taken together, we were able to confirm celecoxib and atRA as compounds that dose-dependently decrease MDSC frequencies.

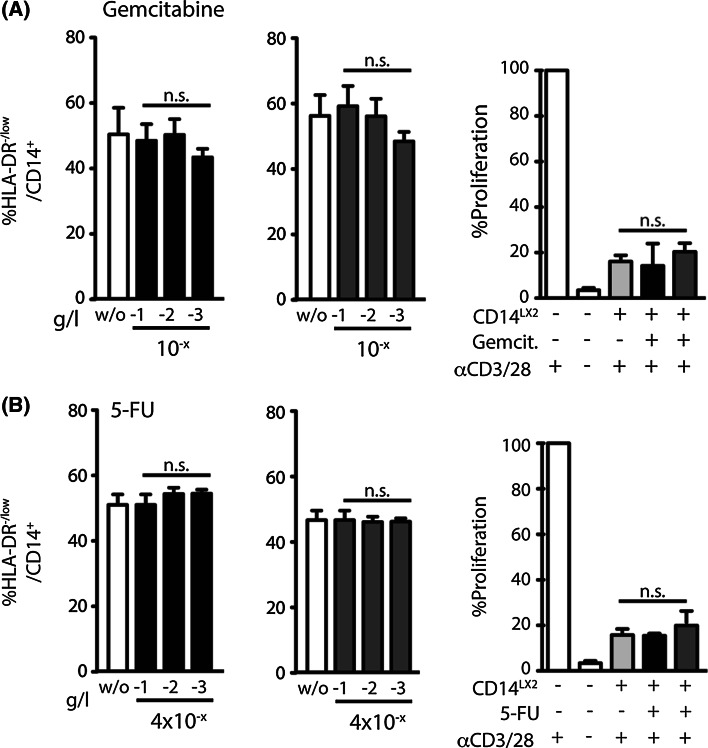

Common chemotherapeutic agents do not reduce HSC-induced MDSC frequencies

We next tested whether chemotherapeutic agents also reduce the frequency of MDSCs in our system. The cytidine analogue gemcitabine (Fig. 3a) and anti-metabolite 5-fluorouracil (Fig. 3b) are two commonly used chemotherapeutics applied for a wide range of tumors.

Fig. 3.

Common chemotherapeutic agents do not reduce HSC-induced MDSC frequencies. cytidine analogue gemcitabine (a) and anti-metabolite 5-fluorouracil (b) were analyzed in the same experimental set-up that was used in Fig. 2. No change in MDSC frequencies or in T cell suppressive capacity was detected for these two drugs (induction phase—black columns; established phase—dark gray columns)

When these compounds were analyzed in the same experimental set-up that was used for atRA and celecoxib, we found no change in MDSC frequencies or in T cell suppressive capacity for any of these two drugs (Fig. 3a, b), indicating that more specific effects rather than simple apoptosis induction by chemotherapy modulate these changes.

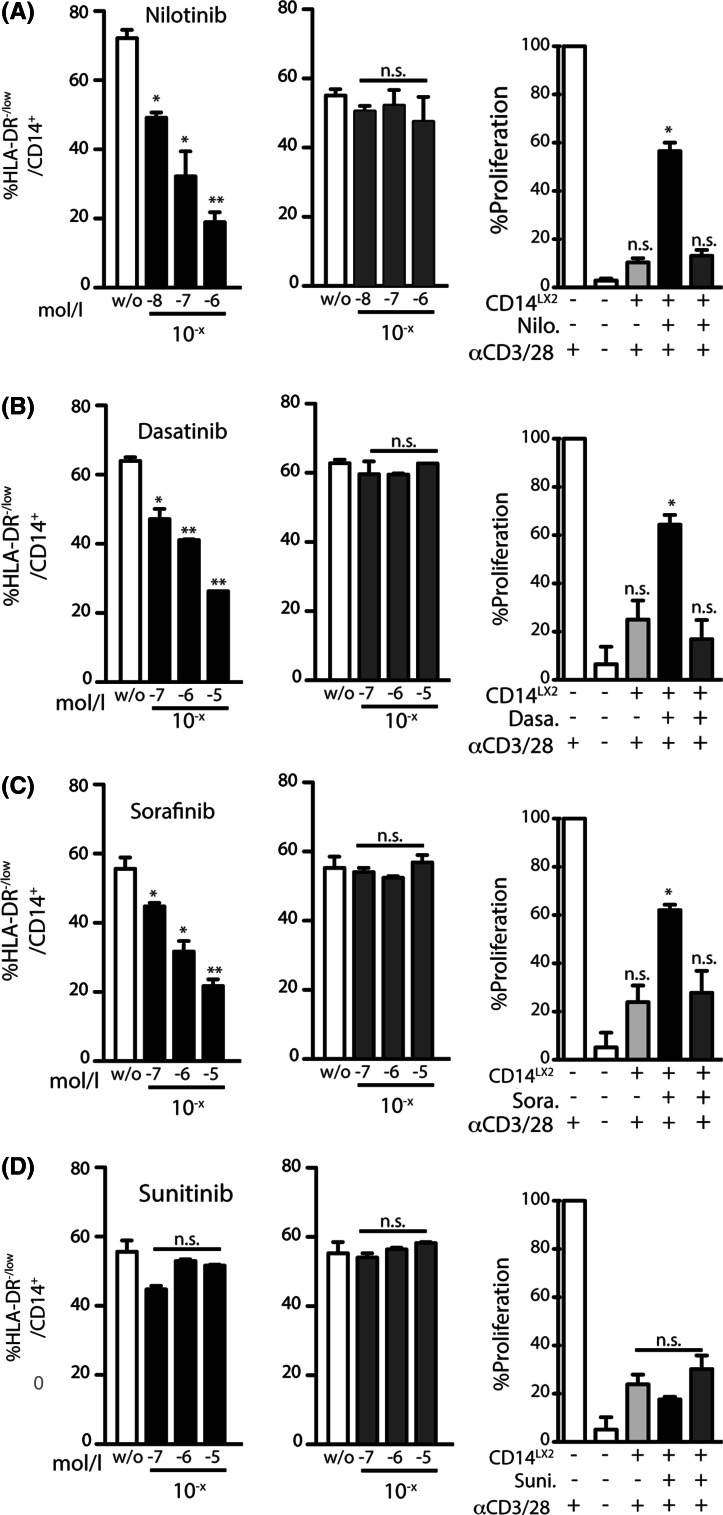

Dasatinib, nilotinib and sorafenib, but not sunitinib reduce frequencies of HSC-induced MDSCs

TKIs are applied as part of standard treatment of several neoplastic conditions and have significantly changed the course of disease in some of these malignancies, particularly in the case of CML. It is well established that TKIs not only exert effects on the malignant cell clone itself but also directly affect immune or other healthy cells. In order to demonstrate that the addition of TKIs modulated the generation of CD14+HLA-DR−/low cells and not simply induced apoptosis, we first performed 7-AAD and annexin-V staining. The addition of TKIs to the co-culture in the highest concentration applied for each compound did not induce more apoptosis than the untreated control, neither in the HSCs nor in the monocytes (<20 % in HSCs and <10 % in CD14+ cells; Supplementary Figure 1A). Hence, live/dead staining revealed no significant induction of apoptosis in monocytes and HSCs using the depicted TKI dosages.

In the next set of experiments, we wanted to determine whether the TKI-induced inhibition of MDSC induction is specific for the mode of MDSC induction in this model. One possible explanation is a contact-dependent inhibition of MDSC induction through CD44, as we have reported previously [16]. Staining for CD44 on HSCs in our experimental setting revealed no TKI-mediated down-regulation of CD44 on HSCs, making this option seem rather unlikely (Supplementary Figure 1B).

To test the effect of TKIs on the induction of MDSCs, we next incubated monocytes on HSCs in the presence of several TKIs. We found that frequencies of MDSCs were significantly and dose-dependently reduced in the presence of dasatinib, nilotinib and sorafenib (Fig. 4a–c). Interestingly, sunitinib had no effect on the induction of monocytic MDSCs in our in vitro culture system (Fig. 4d). Of note, the regulatory effect on MDSC induction was only observed when TKIs were present during the early induction phase of MDSCs (Fig. 4, black columns), whereas already differentiated MDSCs were not influenced by the addition of TKIs (Fig. 4, dark gray columns).

Fig. 4.

Dasatinib, nilotinib and sorafenib, but not sunitinib reduce frequencies of MDSC-induced HSCs. Monocytes were co-cultured on HSCs as described in Fig. 1 in the presence of TKIs as indicated nilotinib (a): without; 10−8; 10−7; 10−6 mol/L; dasatinib (b), sorafenib (c) or sunitinib (d): all without; 10−7; 10−6; 10−5 mol/L. *p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001, n.s. not significant

Mechanistic analysis of the observed effects

In the following experiments, we strived to determine the underlying mechanism of the observed effects. We first assessed the effect of TKIs on intracellular signaling cascades in CD14+ cells cultured on HSCs.

One important pathway regulating myeloid maturation and survival is the MAPK pathway [28–30]. To analyze this pathway, protein levels of ERK, p38 and pp38 were determined in CD14+ cells that had been exposed to dasatinib, nilotinib, sunitinib or sorafenib.

In DCs stimulated with LPS, it is known that sorafenib, but not sunitinib inhibits phosphorylation of p38, whereas levels of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 protein are increased [29]. When assessing MDSCs, we detected that all TKIs decreased the phosphorylation of p38 compared to untreated cells. In contrast to the stable inhibition of pp38, the activation of ERK (pERK) was slightly upregulated under sunitinib treatment (Supplementary Figure 5). We next analyzed whether the NFκB signal pathway is differentially affected by dasatinib, nilotinib, sunitinib or sorafenib. In particular, we were interested to investigate whether sunitinib exerts effects different from the other applied TKIs.

We therefore examined the translocation of proteins involved in the NFκB pathway by immunofluorescence staining for p65 (Rel-A), c-Rel and p105/p50 (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figure 2–4). As described earlier, we again discriminated the two different time points of drug application: addition either on the first day of culture, day 0 (referred to as induction phase, in.ph.) or on day 2 when MDSC induction has already occurred. As for p65, we observed that this precursor protein was markedly higher expressed in HSCs than in monocytes (Fig. 5, upper row). Effects on the translocation of p65 (Fig. 5, top row) or p105/p50 (Fig. 5, top row) into the nucleus were neither detected in the untreated control nor in the atRA treated nor in any of the TKI-treated groups (Fig. 5, top row).

Fig. 5.

Dasatinib, nilotinib, sorafenib and sunitinib do not differentially affect the NFκB signal pathway. HSCs were cultured on poly-l-lysine coated cover slides, and monocytes were added. Cells were co-cultured for 3 days and were left untreated, treated with atRA (10−6 mol/L), with nilotinib (10−6 mol/L), dasatinib, sorafenib or sunitinib (10−5 mol/L) on day 0 or 2. The activation of the NFκB pathway was measured by the nuclear translocation of p65 (Rel-A), p105/p50 or c-Rel. NFκB proteins are depicted in red, the nucleus is stained in blue (DAPI), and cytoskeleton in green (phalloidin)

Taken together, all four TKIs slightly decreased the phosphorylation of p38, whereas no significant changes in the NFκB pathway were detected. Dasatinib, nilotinib, sorafenib and sunitinib have no identical, but rather diverse effects on the NFkB family member p105/50, while RelA (p65) and c-Rel showed no significant effects in nuclear translocation upon treatment with these TKIs. In addition, sunitinib increased the phosphorylation of ERK.

Discussion

We here investigate the effect of several TKIs on the induction of MDSCs that were trans-differentiated from mature human monocytes using a new model of MDSC induction through activated HSCs.

First, we could confirm the results of other groups that treatment with retinoic acid or inhibition of Cox-2 results in decreased MDSC induction [31, 32]. Interestingly, we found that the transdifferentiation of monocytes into MDSCs was blocked, whereas already induced MDSCs were not further affected by these compounds. This observation indicates that the exact timing of adding the compounds to the co-culture is of importance.

It has previously been shown that PGE2-blockade via Cox-2 inhibition impedes MDSC formation [32, 33]. This finding is consistent with our observation that inhibition of Cox-2 prevents the transdifferentiation in early stages, but already induced MDSCs are not affected. In addition, atRA has been shown to up-regulate glutathione synthase [34] leading to an increased level of glutathione that in turn matures MDSCs. Our data suggest that monocytic MDSCs are not matured by retinoic acid, but the further development of MDSCs is somehow inhibited. In contrast to atRA and Cox-2 inhibitors, the addition of standard chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine or 5-fluorouracil did not reduce the induction of MDSCs. Both agents are nucleotide analogs that are integrated into the DNA of dividing cells. Since neither monocytic MDSCs nor monocytes proliferate significantly, standard chemotherapeutic agents might not directly affect these cells; however, a treatment-associated reduced tumor volume might indirectly modulate MDSC frequency and function.

It is well established that TKIs not only exert effects on the malignant cell itself but also directly affect immune cells [19, 21, 29, 35]. These immunomodulatory effects can significantly influence the course of disease in patients. Moreover, treatment regimens combining TKIs with immunotherapeutic approaches, e.g., the sequential use of a TKI with a tumor vaccine or a checkpoint inhibitor in renal cell cancer patients [36–38] are currently being tested in various pre-clinical and clinical studies. These protocols and therapy cascades have to be carefully evaluated with regard to possible immune-mediated interactions and cells, among them MDSCs.

We were next able to show that the addition of nilotinib, dasatinib and sorafenib to our in vitro cell culture system resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in the number of induced CD14+HLA-DR−/low monocytes as well as in a decreased immunosuppressive capacity. To exclude that TKIs have a direct effect on HSCs, e.g., by inducing apoptosis or down-regulation of CD44, we first tested these possibilities and found both to be not the case. Of note, the dose-dependent decrease in the number of induced CD14+HLA-DR−/low monocytes was only observed when the TKIs were added in the early induction phase with the launch of the co-culture, whereas a later addition at day 2 during the already “established phase” did not change MDSC frequencies or function. Thus, transdifferentiation of monocytes into MDSCs through HSCs can be blocked, whereas already induced MDSCs remain unaffected. This effect might indicate that during early induction of MDSCs, monocytes harbor a strong plasticity, which is partially lost after initial differentiation signals have been received. A more detailed characterization of this plasticity is subject of ongoing studies in our lab.

It has been reported that sunitinib can reverse immunosuppression in patients suffering from advanced renal cell cancer. In this study the authors found that sunitinib inhibits MDSC accumulation and thereby restores T cell function [39, 40]. Similar results have been shown in RCC patients, where sunitinib treatment leads to a lower level of circulating MDSCs [41].

However, sunitinib in contrast to nilotinib, dasatinib or sorafenib did not alter the frequencies or function of MDSCs in our in vitro model.

Similar to our results, Hipp et al. [29] demonstrated that sunitinib and sorafenib exert differential effects on monocyte-derived dendritic cells (moDCs) by showing that sorafenib, but not sunitinib affects phenotype and function of moDCs through different modulation of the NFκB and MAPK signaling pathway. Thus, we next tried to identify a differential effect of sunitinib in contrast to sorafenib, dasatinib and nilotinib on different intracellular signaling pathways in MDSCs. We detected a decreased phosphorylation of p38 in CD14+ cells cultured on HSCs and treated with different TKIs in contrast to untreated cells. However, there were no differences in phosphorylation among the different TKIs. Also immunofluorescence imaging of the NFκB pathway revealed no differences induced by TKIs on the translocation of the NFκB proteins c-Rel, p65 and p105/p50 into the nucleus, neither in the induction nor in the established phase model.

Although it has been shown that different TKIs have different effects on monocytic cells via NFκB and MAPK pathway interaction [29], we could not detect any differences in these pathways in MDSCs. The fact that nilotinib, dasatinib or sorafenib, but not sunitinib reduced the frequency of MDSCs suggests that other pathways might be affected which still remain to be determined. Possible candidates could be regulatory associated pathways. Further studies as well as a careful clinical evaluation and observation will be essential in order to determine how and why TKIs modulate MDSCs.

In conclusion, our results indicate that sorafenib, nilotinib and dasatinib, but not sunitinib, decrease the HSC-mediated induction of MDSC frequency and function. We also demonstrate that the exact time point of drug application is of importance. Therefore, concomitant treatment of cancer patients with these compounds could differentially modulate the success of immunotherapeutic or other anti-cancer approaches with regard to their timing.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kati Riethausen, Solveig Daecke and Daniel Schätzlein for the excellent technical support. This study was supported by a grant from BONFOR Forschungsförderung (Annkristin Heine & Bastian Höchst).

Abbreviations

- atRA

All-trans retinoic acid

- CML

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- Cox-2

Cyclo-oxygenase-2

- es. ph.

Established phase

- Gr-1high

CD11b+Ly-6G+Ly-6Clow

- Gr-1low

CD11b+Ly-6G−Ly-6Chigh

- HSC

Hepatic stellate cell

- in. ph.

Induction phase

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharides

- MDSC

Myeloid derived suppressor cell

- MoDC

Monocyte derived dendritic cell

- NFκB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PD-1

Programmed death 1

- TKI

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Annkristin Heine, Phone: 0049228/287-11038, Email: annkristin.heine@ukb.uni-bonn.de.

Bastian Höchst, Email: Bastian.Hoechst@tum.de.

References

- 1.De Veirman K, Van Valckenborgh E, Lahmar Q, Geeraerts X, De Bruyne E, Menu E, Van Riet I, Vanderkerken K, Van Ginderachter JA. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as therapeutic target in hematological malignancies. Front Oncol. 2014;4:349. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz-Montero CM, Finke J, Montero AJ. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer: therapeutic, predictive, and prognostic implications. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:174–184. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escors D, Liechtenstein T, Perez-Janices N, et al. Assessing T-cell responses in anticancer immunotherapy: dendritic cells or myeloid-derived suppressor cells? Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e26148. doi: 10.4161/onci.26148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filipazzi P, Huber V, Rivoltini L. Phenotype, function and clinical implications of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medina-Echeverz J, Aranda F, Berraondo P. Myeloid-derived cells are key targets of tumor immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e28398. doi: 10.4161/onci.28398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich DI. Tumor escape mechanism governed by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2561–2563. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human cancer. Cancer J. 2010;16:348–353. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181eb3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solito S, Marigo I, Pinton L, Damuzzo V, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity in human cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1319:47–65. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagaraj S, Gabrilovich DI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:213–223. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talmadge JE. Pathways mediating the expansion and immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their relevance to cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5243–5248. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lechner MG, Megiel C, Russell SM, Bingham B, Arger N, Woo T, Epstein AL. Functional characterization of human Cd33+ and Cd11b+ myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets induced from peripheral blood mononuclear cells co-cultured with a diverse set of human tumor cell lines. J Transl Med. 2011;9:90. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peranzoni E, Zilio S, Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Zanovello P, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity and subset definition. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wesolowski R, Markowitz J, Carson WE., 3rd Myeloid derived suppressor cells-a new therapeutic target in the treatment of cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2013;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hochst B, Schildberg FA, Sauerborn P, et al. Activated human hepatic stellate cells induce myeloid derived suppressor cells from peripheral blood monocytes in a CD44-dependent fashion. J Hepatol. 2013;59:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Held SA, Heine A, Mayer KT, Kapelle M, Wolf DG, Brossart P. Advances in immunotherapy of chronic myeloid leukemia CML. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2013;13:768–774. doi: 10.2174/15680096113139990086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jabbour E, Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Long-term outcomes in the second-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: a review of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer. 2011;117:897–906. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appel S, Boehmler AM, Grunebach F, et al. Imatinib mesylate affects the development and function of dendritic cells generated from CD34+ peripheral blood progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103:538–544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozao-Choy J, Ma G, Kao J, et al. The novel role of tyrosine kinase inhibitor in the reversal of immune suppression and modulation of tumor microenvironment for immune-based cancer therapies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2514–2522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schade AE, Schieven GL, Townsend R, Jankowska AM, Susulic V, Zhang R, Szpurka H, Maciejewski JP. Dasatinib, a small-molecule protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits T-cell activation and proliferation. Blood. 2008;111:1366–1377. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-084814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heine A, Held SA, Daecke SN, Wallner S, Yajnanarayana SP, Kurts C, Wolf D, Brossart P. The JAK-inhibitor ruxolitinib impairs dendritic cell function in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2013;122:1192–1202. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-484642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heine A, Held SA, Daecke SN, Riethausen K, Kotthoff P, Flores C, Kurts C, Brossart P. The VEGF-receptor inhibitor axitinib impairs dendritic cell phenotype and function. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao J, Ko EC, Eisenstein S, Sikora AG, Fu S, Chen SH. Targeting immune suppressing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowe DB, Bose A, Taylor JL, Tawbi H, Lin Y, Kirkwood JM, Storkus WJ. Dasatinib promotes the expansion of a therapeutically superior T-cell repertoire in response to dendritic cell vaccination against melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2014;3:e27589. doi: 10.4161/onci.27589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Motoshima T, Komohara Y, Horlad H, et al. Sorafenib enhances the antitumor effects of anti-CTLA-4 antibody in a murine cancer model by inhibiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:2947–2953. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez PC, Ernstoff MS, Hernandez C, Atkins M, Zabaleta J, Sierra R, Ochoa AC. Arginase I-producing myeloid-derived suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma are a subpopulation of activated granulocytes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1553–1560. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardeshna KM, Pizzey AR, Devereux S, Khwaja A. The PI3 kinase, p38 SAP kinase, and NF-kappaB signal transduction pathways are involved in the survival and maturation of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96:1039–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hipp MM, Hilf N, Walter S, Werth D, Brauer KM, Radsak MP, Weinschenk T, Singh-Jasuja H, Brossart P. Sorafenib, but not sunitinib, affects function of dendritic cells and induction of primary immune responses. Blood. 2008;111:5610–5620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Q, Kovacs C, Yue FY, Ostrowski MA. The role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase signal transduction pathways in CD40 ligand-induced dendritic cell activation and expansion of virus-specific CD8+ T cell memory responses. J Immunol. 2004;172:6047–6056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iclozan C, Antonia S, Chiappori A, Chen DT, Gabrilovich D. Therapeutic regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and immune response to cancer vaccine in patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:909–918. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obermajer N, Wong JL, Edwards RP, Odunsi K, Moysich K, Kalinski P. PGE(2)-driven induction and maintenance of cancer-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunol Invest. 2012;41:635–657. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2012.695417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li RJ, Liu L, Gao W, Song XZ, Bai XJ, Li ZF. Cyclooxygenase-2 blockade inhibits accumulation and function of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and restores T cell response after traumatic stress. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci. 2014;34:234–240. doi: 10.1007/s11596-014-1264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nefedova Y, Fishman M, Sherman S, Wang X, Beg AA, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism of all-trans retinoic acid effect on tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11021–11028. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heine A, Held SA, Bringmann A, Holderried TA, Brossart P. Immunomodulatory effects of anti-angiogenic drugs. Leukemia. 2011;25:899–905. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailey A, McDermott DF. Immune checkpoint inhibitors as novel targets for renal cell carcinoma therapeutics. Cancer J. 2013;19:348–352. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31829e3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDermott DF, Drake CG, Sznol M, et al. Survival, durable response, and long-term safety in patients with previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2013–2020. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1430–1437. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ko JS, Rayman P, Ireland J, Swaidani S, Li G, Bunting KD, Rini B, Finke JH, Cohen PA. Direct and differential suppression of myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets by sunitinib is compartmentally constrained. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3526–3536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ko JS, Zea AH, Rini BI, et al. Sunitinib mediates reversal of myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation in renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2148–2157. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Cruijsen H, van der Veldt AA, Vroling L, et al. Sunitinib-induced myeloid lineage redistribution in renal cell cancer patients: CD1c+ dendritic cell frequency predicts progression-free survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5884–5892. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.