Abstract

Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) of in vitro expanded autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) has been shown to exert therapeutic efficacy in melanoma patients. We aimed to develop an ACT protocol based on tumor-specific T cells isolated from peripheral blood and in vitro expanded by Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28. We show here that the addition of an in vitro restimulation step with relevant peptides prior to bead expansion dramatically increased the proportion of tumor-specific T cells in PBMC-cultures. Importantly, peptide-pulsed dendritic cells (DCs) as well as allogeneic tumor lysate-pulsed DCs from the DC vaccine preparation could be used with comparable efficiency to peptides for in vitro restimulation, to increase the tumor-specific T-cell response. Furthermore, we tested the use of different ratios and different types of Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 and CD3/CD28/CD137 T-cell expander, for optimized expansion of tumor-specific T cells. A ratio of 1:3 of Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander to T cells resulted in the maximum number of tumor-specific T cells. The addition of CD137 did not improve functionality or fold expansion. Both T-cell expansion systems could generate tumor-specific T cells that were both cytotoxic and effective cytokine producers upon antigen recognition. Dynabeads®-expanded T-cell cultures shows phenotypical characteristics of memory T cells with potential to migrate and expand in vivo. In addition, they possess longer telomeres compared to TIL cultures. Taken together, we demonstrate that in vitro restimulation of tumor-specific T cells prior to bead expansion is necessary to achieve high numbers of tumor-specific T cells. This is effective and easily applicable in combination with DC vaccination, by use of vaccine-generated DCs, either pulsed with peptide or tumor-lysate.

Keywords: T-cell expansion, Adoptive T-cell therapy, Tumor-specific T cells, Dynabeads ClinExVivo CD3/CD28

Introduction

Adoptive cell transfer (ACT) is an attractive strategy to eradicate tumor cells in patients with malignancies [1]. Tumors are often infiltrated by a population of lymphocytes highly enriched of tumor-specific T cells [2]. However, due to the immunosuppressive local environment surrounding cancer lesions, these cells are not optimally equipped to exert their natural antitumor functions. Therefore, isolation, expansion and in vitro T-cell activation before reinfusion provide several advantages. Indeed, this procedure increases the number of tumor-specific T cells and removes them from the immunosuppressive environment. This strategy has been followed in ACT of T cells expanded from TILs from melanoma patients resulting in objective response rates around 50% [3]. However, expansion of TILs is not always feasible, and this treatment is not easily applicable to some malignancies, such as breast and colon cancers, due to difficulties in initiating T-cell cultures from TILs or limited access to tumor material [4, 5]. As an alternative strategy for this group of patients, expansion of tumor-specific T cells from peripheral blood is an attractive approach because of easy access to large numbers of T cells. Expansion of large numbers of T cells from blood (in the range of 1–5 × 1010 T cells) can be achieved by using Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28 [6]. This T-cell expansion system has been applied for generation of large numbers of autologous T cells from peripheral blood used for ACT in various cancers [7–11]. However, direct expansion of T cells using polyclonal stimuli like anti-CD3/CD28-coated dynabeads only expands the few spontaneously induced tumor-specific T cells along with many other non-tumor relevant T cells. Thus, in vivo priming by vaccination to increase the number of tumor-specific T cells appears to be the key to generate high numbers of tumor-specific T cells. Indeed a recent study by Dang et al. [12] showed that patients vaccinated with a HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccine had a >25-fold higher frequency of antigen-specific T cells in peripheral blood compared to unvaccinated patients. Also, inclusion of a peptide restimulation step prior to bead expansion can increase the number of tumor-specific T cells in the final T-cell product [13].

We aimed at developing a protocol for ACT based on tumor-specific T cells from peripheral blood induced by vaccination with dendritic cells (DCs) pulsed with allogeneic tumor lysate and combined with in vitro expansion of T cells using Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28. DCs for vaccination were generated according to established procedures [14]. An efficient in vivo priming of tumor-specific T cells by anti-tumor vaccination is crucial [12]. However, boosting the response in vitro by antigen-specific stimulation prior to unspecific expansion can be an additional option to increase the number of tumor-specific T cells in the final cellular product used for ACT [13]. Therefore, we tested various strategies to enhance tumor specificity of the harvested PBMCs after DC vaccination and prior to bead expansion, and we demonstrate the efficiency and feasibility of including an in vitro restimulation step using the DCs generated for vaccination to boost the anti-tumor-specific T cells prior to bead expansion.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

Patient blood samples were obtained in the context of non-randomized phase I/II clinical trials at Copenhagen University Hospital, Herlev, which included patients with either locally advanced or stage IV malignant melanoma (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00197912) [14] or metastatic renal cell carcinoma (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00197860) [15]. Briefly, patients were treated with autologous monocyte-derived DCs loaded with tumor antigens, and concomitant low-dose IL-2 and IFN-α2b (melanoma patients) or low-dose IL-2 alone (renal cell carcinoma patients). In the melanoma trial DCs were pulsed with autologous or allogeneic tumor cell lysate (WM115, COLO 829 and SK-MEL-28) prior to DC maturation or tumor-associated peptides (dependent on HLA-type) after DC maturation. In the renal cell carcinoma trial DCs were pulsed with allogeneic tumor cell lysate (A-498, Caki-1 and Caki-2) prior to DC maturation or tumor-associated peptides (dependent on HLA-type) after DC maturation. The DCs were cryopreserved and thawed on the day of vaccination. For further details see [14, 15]. PBMCs from patients with DC vaccine-induced tumor-specific responses were selected for restimulation and expansion by dynabeads. Tumor-specific responses were previously detected either by Elispot assay or tetramer staining [14, 15]. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethical committees, Copenhagen County and Danish Medicines Agency, and was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients before study entry.

PBMC collection and processing

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from peripheral blood by gradient centrifugation (lymphoprep, 1.077 g/ml, Nycomed, Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway). Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were cryopreserved in heat-inactivated human AB serum containing 10% DMSO and stored in liquid N2 until use.

T-cell restimulation and bead expansion cultures

T cells were cultured in CellGro® DC serum-free culture media (CellGenix, Freiburg, Germany) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated human serum, 10 mM N-acetylcystein (Mucomyst 200 mg/ml AstraZeneca AS, Norway) plus 20U/ml recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2) (PeproTech, Boston, MA, USA), and 5 ng/ml recombinant human interleukin-7 (IL-7) (PeproTech) for T-cell restimulation or plus 100 U/ml recombinant human IL-2 for T-cell expansion. For restimulation cultures, 2 × 106 PBMCs/2 ml were seeded in 24-well plates with peptides at a concentration of 5 μM or 2 × 105 peptide/allogeneic tumor cell lysate-pulsed DCs, and cultured for 14 days at 37°C, 5% CO2 (when indicated only 7 days). DCs used for restimulation were from the vaccine preparation batch. The peptides used for restimulation were: A2 CMV pp65495–503 (NLVPMVATV), B7 CMVpp65 TPR417–426 (TPRVTGGGAM), A2 EBV LMP2 FLY356–364 (FLYALALLL), A3 EBV EBNA 3aRLR417–479 (RLRAEAQVK), A2 hTERTp988988–997 (YLQVNSLQTV), A2 hTERTp3030–38 (RLGPQGWRV), A2 Sur1M296–104 (LMLGEFLKL), A1 AIM-2AORF (RSDSGQQARY), A1 N-Ras55–64 (ILDTAGREEY), A2 Bcl-2214–23 (WLSLKTLLSL), A2 MAGE-A2250–58 (LVQENYLEY), A2 p53 K9V139–47 (KLCPVQLWV), A2 PRDX5163–172 (LLLDDLLVSI), A2 TRP-2180–188 (SVYDFFVWL), A2 TRP-2185–193 (FVWLHYYSV), A2 HIV-1 Pol476–84 (ILKEPVHGV), and A3 HIV-1 gagp17, 20–28 (RLRPGGKKK), all from Karl Ross-Petersen (Klampenborg, Denmark). For T-cell expansion either Dynabeads® CD3/CD28, Dynabeads® CD3/CD28/CD137 or Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28 T-cell expander (Dynal Invitrogen, Oslo, Norway) was used (as indicated). The T-cell expansion cultures were initiated with 1 × 106 CD3 T cells/2 ml in 24-well tissue culture plates. Dynabeads were added in the beginning of the culture at a ratio of 1:1, 1:3, or 1:10 (Dynabead:T cell). Every 2–3rd day, cells were counted and concentration adjusted to 5 × 105 cells/ml in 12- or 6-well plates. The cells were analyzed for tetramer-specific T cells both prior to and after restimulation, and again after bead expansion. The total number of cells after dynabead expansion was calculated.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

For flow cytometry assays, the following fluorochrome conjugated monoclonal antibodies were used: APC-Cy7 anti-CD8, AmCyan anti-CD3, PE-Cy7 anti-CD3, PerCP anti-CD3, FITC anti-CD4, FITC anti-CD57, PE-Cy7 anti-CCR7, APC-Cy7 anti-CD3, PerCP anti-CD8, APC anti-CD27, FITC anti-CD28, APC anti-CD45RO, Horizon V450 anti-CD62L, APC anti-IFNγ, PE anti-TNFα, and FITC anti-IL-2, all from BD Biosciences (BD Bioscience San José, CA, USA). To discriminate between live and dead cells, 7-actinomycin D (7AAD) was used (BD Bioscience). Relevant phycoerythrin (PE)-coupled major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-tetramers were produced in our laboratory as described previously [16, 17]. For tetramer staining cells were incubated for 15 min at 37°C with tetramers, following addition of antibodies to surface markers and additional incubation for 30 min at 4°C. All stainings were done in PBS + 0.5% BSA. 200.000 lymphocytes were acquired, corresponding to an average number of around 50.000 CD8 positive T cells. The analysis of percentages of tetramer-specific T cells was all done on fresh cells; however, the phenotypic analysis was performed on frozen material. For intracellular cytokine staining, ebioscience fixation/permabilization kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was used, according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, cells were incubated at a concentration of 2–3 × 106 cells/2 ml in 24-well plates for 5 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 with 5 μM peptide (or control peptide), and the last 4 h in the presence of 1 μl/ml GolgiPlug (BD Bioscience). Cells were harvested and stained according to the protocol suggested by the manufacturer (ebioscience). Flow cytometry analysis was acquired on FACSCanto II or LSR II cytometer (Becton–Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and data analyses were conducted using FACSDiva software.

Cytotoxicity determined by chromium release assay

The ability of dynabead-expanded T cells to lyse target cells was analyzed by a conventional 51Cr release assay as described [18]. In brief, T2 target cells were pulsed with hTERTp30 peptide or HIV peptide labeled with chromium and incubated 4 h with dynabead-expanded T cells at 40:1 effector to target ratio.

Telomere length analysis

Thermal stable Qdots and Alexa-Fluor conjugates allow simultaneous fluorescent immunophenotyping and telomere length measurement by Flow-Fluorescent in situ Hybridization (FISH) [2, 19]. TIL cultures were obtained from patients with metastatic melanoma and expanded in vitro, as previously described [2]. Bead expanded T cells were stained with Alexa-Fluor 647 anti-CD8 (BD Bioscience) and Qdot655-coupled tetramers (hTERTp30 or hTERTp988), and TILs were stained with Alexa-Fluor 647 anti-CD8. Antibodies and tetramers were cross-linked to the cell membrane with bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (BS3) (Thermo Scientific), final concentration 2 mM in citrate buffer for 30 min at 4°C. Excess reagent was quenched with 20 mM Tris–Cl pH 8 for 15 min at room temperature, as previously described [20–22]. Cells were then washed with PBS, and subsequently relative telomere length of bead expanded CD8 T cells, bead expanded hTERT-specific T cells, and CD8+ TILs were assessed by using Telomere PNA Kit/FITC, for Flow Cytometry (Dako, Denmark) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The 1301 cell line (European Collection of Cell Cultures) was used as internal standard. Cells were acquired using a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer. On average around, 10.000 CD8 T cells in G0/G1 were acquired corresponding to between 100 and 600 tetramer-positive T cells. Analysis was performed with BD FacsDiva Software on cells in G0/G1 phase. Relative telomere lengths of different subpopulations were compared using a Mann–Whitney U-test.

Results

Direct dynabead expansion of low and high frequent antigen responses

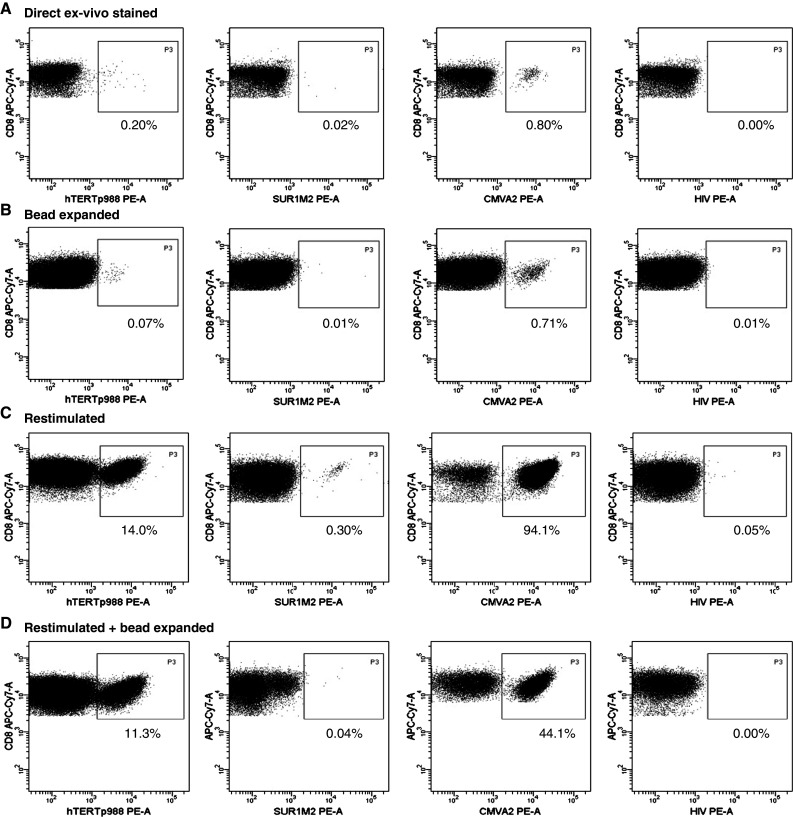

To evaluate the efficacy of “Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander” to expand specific T cells in harvested PBMCs from cancer patients following DC vaccination, we first analyzed direct expansion of (1) DC vaccine-induced tumor-specific T cells (hTERTp988), (2) spontaneously induced tumor-specific T cells (Sur1M2), and 3) virus-specific T cells (CMV) by Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander. By tetramer staining, we were able to detect hTERTp988-specific CD8 T cells (0.20% of CD8 T cells) in a patient with renal cell carcinoma after vaccination with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs (Fig. 1a, left plot). hTERTp988-specific CD8 T cells were still detectable, but at a low frequency (0.07% of CD8 T cells) after expansion with dynabeads (Fig. 1b, left plot). A spontaneous Sur1M2 response that had been detectable by Elispot assay after a 7-day peptide restimulation in a melanoma patient prior to DC vaccination was undetectable by tetramers directly ex vivo and did not appear after dynabead expansion (Fig. 1a, b, middle left plots). In the same patient, a CMV response was detectable both before and after dynabead expansion (Fig. 1a, b, middle right plots). The percentage of CMV-specific T cells remained relatively constant throughout the expansion (0.80% vs. 0.71% of CD8 T cells). These data indicates that both relatively high frequent responses like CMV (0.80% of CD8 T cells) and low frequent responses like hTERTp988 (0.20% of CD8 T cells) may persist after dynabead expansion, but undetectable responses like Sur1M2 do not appear after bead expansion.

Fig. 1.

Enhancement of tumor- and virus-specific T cell by in vitro restimulation and expansion by CD3/CD28 T-cell expander PBMCs from a patient with renal cell carcinoma who previously received vaccination with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs (hTERTp988 response) or a melanoma patient prior to inclusion in DC vaccination trial (Sur1M2 and CMV) were either directly stained with relevant tetramers, bead expanded for 12 days and stained with tetramers, restimulated for 14 days with peptide and stained with tetramers or restimulated with peptide for 14 days + bead expanded for 12 days and stained with tetramer. Shown is percentage of tetramer-specific T cells out of CD8 T cells on a directly ex vivo stained cells, b directly bead-expanded cells, c restimulated cells and d restimulated and bead-expanded cells. Depicted HIV controls are from the melanoma patient. Similar HIV controls were performed on cells from the renal cell carcinoma patient (data not shown)

Inclusion of a restimulation step prior to dynabead expansion increases the frequency of antigen-specific T cells

We investigated the effect of a restimulation period prior to bead expansion to increase the percentage of antigen-specific cells in the harvested PBMCs. We generated a 14-day culture with relevant peptides and analyzed the percentage of tetramer-specific T cells both before and after dynabead expansion. The percentage of hTERTp988-specific T cells increased substantially, from 0.20 to 14.0% of CD8 T cells (Fig. 1a, c, respectively) after 14 days in culture with peptide, and the response was preserved after dynabead expansion for 12 days (11.3% of CD8 T cells) (Fig. 1d). The increase in percentage of hTERTp988-specific T cells after 14 days of peptide restimulation was observed in three individual experiments using cells from the same donor. The percentage of hTERTp988-specific T cells varied between 8.9 and 14.0%. In addition, in the melanoma patient, the Sur1M2 T cell response, previously undetectable by tetramers, was detected as 0.30% of CD8 T cells after the 14-day peptide stimulation (Fig. 1c). However, after dynabead expansion, the Sur1M2 response was lost indicating that responses in this frequency range may not always persist after non-specific dynabead expansion. The percentage of CMV-specific T cells increased dramatically after 14 days in culture (from 0.80 to 94.1%) (Fig. 1a, c, respectively) and after bead expansion the CMV-specific T cells still made up a large fraction of the CD8 T cells (44.1%) (Fig. 1d).

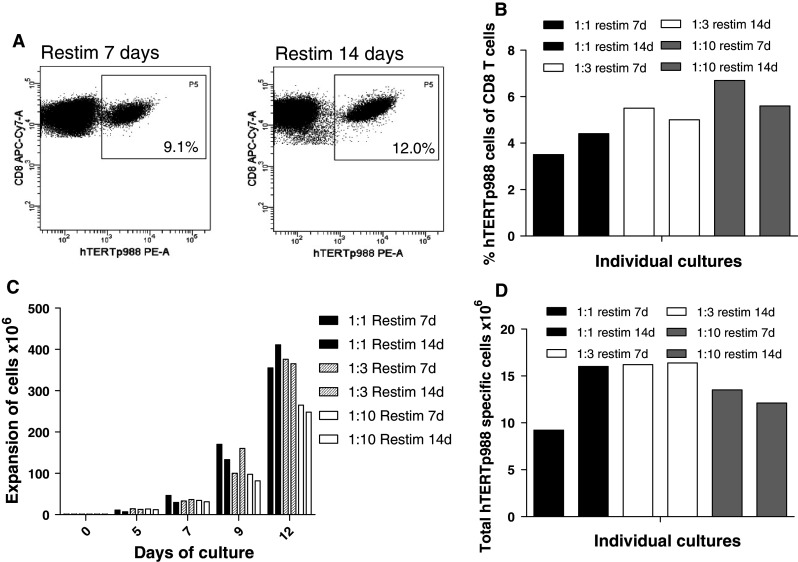

Since we observed a substantial effect of including a restimulation period prior to bead expansion, we next evaluated the effect of varying the time of restimulation. Cells were restimulated with hTERTp988 peptide for either 7 or 14 days, and the percentage of hTERTp988 tetramer-positive cells was analyzed. As demonstrated in Fig. 2a, the percentage of hTERTp988-specific cells increased from day 7 to 14 (9.1–12.0% of CD8 T cells). For both restimulation cultures, we analyzed the percentage of hTERTp988-specific T cells after bead expansion with three different ratios of dynabead to T cell (1:1, 1:3 and 1:10). The percentage of hTERTp988-specific T cells was best maintained in the cultures with lower bead to T-cell ratio (1:3 and 1:10) (Fig. 2b); however the fold of expansion were lower (compared to 1:1) (Fig. 2c). As a consequence, the largest total number of hTERTp988-specific T cells (Fig. 2d) was found in the 1:3 cultures both after 7 and 14 days restimulation and in the 1:1 culture after 14 days restimulation. The effect of restimulating 14 days instead of 7 days was evaluated again in a separate experiment, using cells from a healthy donor. Three viral responses were detected with a frequency of 2.2% (EBV LMP2 FLY), 12.5% (CMVpp65 NLV), and 0.27% (EBV EBNA 3a RLR) of CD8 T after 14 days of culture, while only one response was present after 7 days (9.1% CMV). This underlines the need for a 14-days restimulation period instead of 7 days to efficiently boost the response prior to bead expansion. Finally, in a separate experiment, we compared bead expansion using Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander, Dynabeads® CD3/CD28/CD137 T-cell expander and Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28 to make sure that these beads were equally efficient at expanding tumor-specific T cells. Each of these expansions were performed in duplicates, and no major difference was observed in the fold expansion of T cells, and the frequency of hTERTp988-specific T cells was similar: 1.2; 1.1% (Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander), 1.1; 1.3% (Dynabeads® CD3/CD28/CD137 T-cell expander), and 1.4; 1.6% (Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28) of CD8 T cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Varying the time of restimulation and bead to T-cell ratio in dynabead expansion cultures PBMCs from a patient with renal cell carcinoma who previously received vaccination with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs was restimulated with hTERTp988 peptide for 7 and 14 days and afterward bead expanded for 12 days with Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander at different DB:Tc ratio. a Percentage of hTERTp988 tetramer-specific T cells out of CD8 T cells after 7 day and 14 days of restimulation culture. b Percentage of hTERTp988 tetramer-specific T cells out of CD8 T cells after bead expansion of restimulation cultures (7 and 14 days) with DB:Tc ratio of 1:1, 1:3 and 1:10. c Total number of expanded cells in restimulated and bead-expanded cultures. d Total number of hTERTp988-specific T cells after restimulation and bead expansion

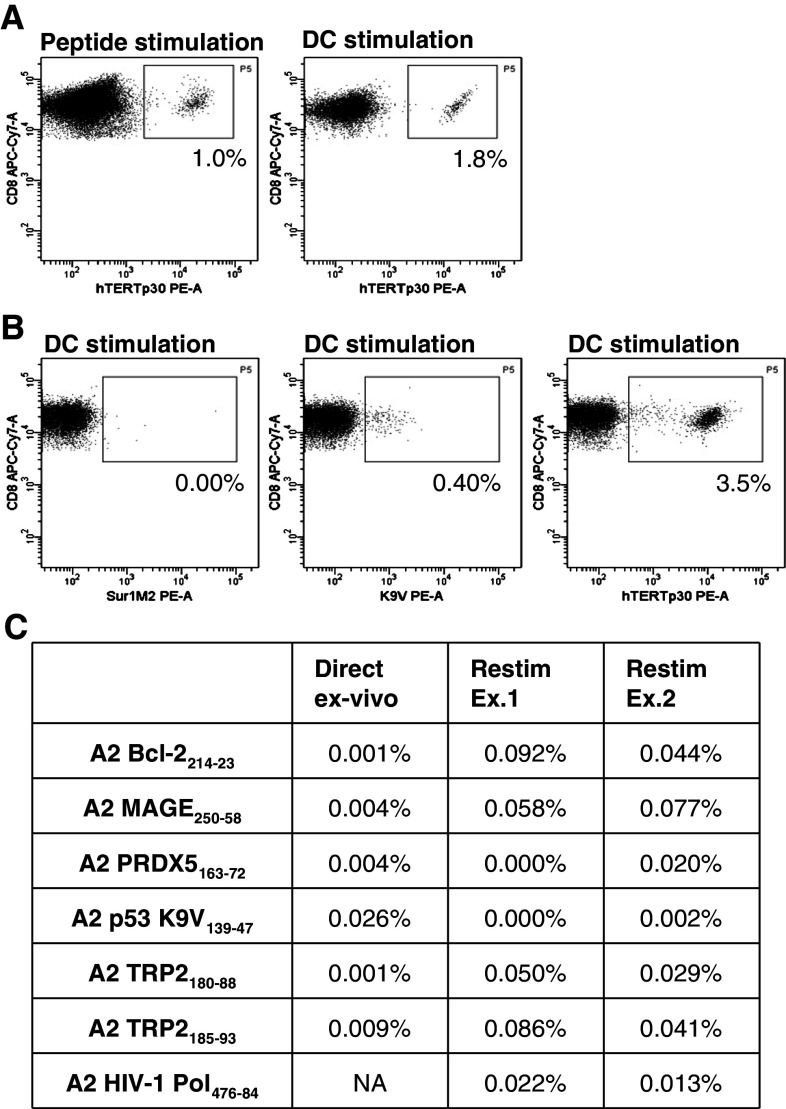

DCs pulsed with either tumor peptides or lysate from allogeneic tumor cell lines can boost the response prior to dynabead expansion

As demonstrated above, inclusion of a peptide restimulation step resulted in preferential expansion of tumor-specific T cells prior to bead expansion. To test whether DCs loaded with tumor antigens can function with similar efficiency as peptides to restimulate the tumor-specific response, we compared restimulation of tumor-specific T cells in cultures with peptide-pulsed DCs to peptides only. We used PBMCs from a patient with metastatic melanoma who previously received vaccination with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs. Responses against hTERTp30, K9V and Sur1M2 were previously detected in PBMCs from this patient using tetramers [14]. In a first experiment, we evaluated the efficiency of peptide-pulsed autologous DCs compared to hTERTp30 peptide-stimulated cells. After 14 days of restimulation, the percentage of hTERTp30-specific T cells was 1.8% versus 1.0% of CD8 T cells in peptide-pulsed DCs and peptide cultures, respectively (Fig. 3a). This illustrates the usability of DCs as stimulators in restimulation cultures. However, the goal of tumor DC vaccination is to induce a broad response based on many T-cell specificities. Thus, in a second experiment using cells from the same patient, we evaluated simultaneous restimulation of both hTERTp30, Sur1M2 and p53 K9V-specific T cells by peptide-pulsed DCs or as controls the individual peptides in separate cultures. As shown in Fig. 3b, we could detect hTERTp30, p53 K9V, but not Sur1M2 after 14 days of restimulation by peptide-pulsed DCs. hTERTp30 and possibly p53 KV9-specific T cells were also detectable after 12 days of bead expansion (2.6 and 0.08% of CD8 T cells, data not shown). The experiment was repeated twice, with variable efficiency showing, respectively, 3.5 or 0.30% hTERTp30 and 0.40 or 0.28% KV9-specific CD8 T cells when using peptide-pulsed DC restimulation. When using individual peptides, the restimulation resulted in 9.9 or 0.28% hTERTp30 and 0.40 or 0.40% K9V-specific CD8 T cells, respectively. This illustrates a variation in the efficiency of the restimulation cultures in both cultures stimulated with peptide and peptide-pulsed DCs. Nevertheless, the responses were always increased by the restimation culture. Finally, we evaluated the possibility of using DCs pulsed with tumor lysate from allogeneic tumor cell lines as restimulators instead of peptide-pulsed DCs. Again, we used both PBMCs and DCs from a patient previous vaccinated with allogenic lysate-pulsed DCs, harboring low frequent tumor-specific responses previously detected by tetramers using multidimensional encoding of T cells [14, 23]. As shown in Fig. 3c, restimulation of PBMCs with DCs pulsed with allogeneic tumor cell lysate, resulted in enhancement of several low frequent responses against A2 Bcl-2214–23, A2 MAGE250–58, A2 TRP2180–88, and A2 TRP2185–93 peptides. However, a number of responses were not enhanced by this restimulation culture, including responses against A2 PRDX5163–72, A2 p53 K9V138–47, A1 AIM-2AORF, and A1 N-Ras55–64 (data from the A1 restricted responses are not shown).

Fig. 3.

DCs can be used in restimulation cultures instead of peptides a PBMCs from a patient with melanoma who previously received vaccination with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs was restimulated with either peptide-pulsed autologous DCs or hTERTp30 peptide for 14 days. Shown are the hTERTp30 tetramer-specific T cells as percentage of CD8 T cells in cultures with peptide-pulsed autologous DCs and hTERTp30 peptide, respectively. b Percentage of Sur1M2, p53 K9V, and hTERTp30 out of CD8 T in one 14 days restimulation culture using peptide-pulsed autologous DCs. c PBMCs from a patient with melanoma who previously received vaccination with allogeneic tumor cell lysate-pulsed autologous DCs was restimulated with the same DCs for 14 days. Shown is the ex vivo percentage of A2 Bcl2, A2 MAGE, A2 TRP2180–188, A2 TRP2185–192, A2 PRDX5, and A2 p53 K9V out of CD8 T cells analyzed by tetramers and the allo-lysate-pulsed DCs restimulated percentage of A2 Bcl2, A2 MAGE, A2 TRP2180–188, A2 TRP2185–192, A2 PRDX5, A2 p53 K9V, and A2 HIV-1 Pol out of CD8 T cells in two individual experiments analyzed by tetramers. NA, not analyzed

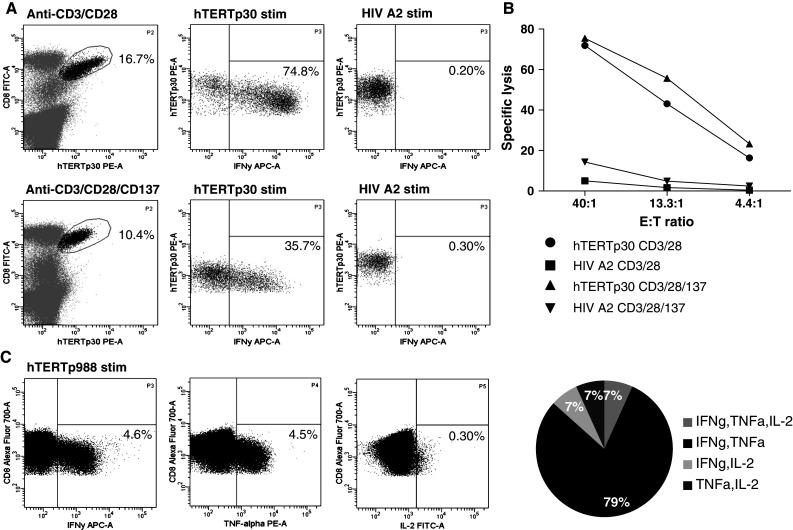

Tumor-specific T cells expanded by dynabeads are cytotoxic and secrete cytokines

To test the functionality of tumor-specific T cells expanded by dynabeads, we analyzed the cytokine secretion upon restimulation with specific peptides and tested the cytolytic capacity toward peptide-pulsed T2 target cells. First, we evaluated the production of IFNγ from hTERTp30-specific T cells expanded either by Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander or Dynabeads® CD3/CD28/CD137 T-cell expander. In a series of duplicate experiments, we analyzed hTERTp30-specific T cells expanded by both bead types and showed that these were able to produce IFNγ (Fig. 4a); however, T cells expanded using the CD3/CD28 Dynabeads®, showed the greatest production of IFNγ. Next, we did chromium release assays against T2 target cells using cultures expanded with both bead types. Specific T cells from both cultures were able to lyse peptide-pulsed target cells equally efficient (Fig. 4b). CD107a, a surrogate marker for cytotoxicity, was also expressed on bead expanded tumor-specific T cells from both cultures (data not shown). Finally, in a separate experiment, we tested the production of IFNγ, TNFα, and IL-2 by antigen-specific T cells in a Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 expanded culture with 5% hTERTp988-specific T cells of CD8 T cells. The majority of the hTERTp988-specific T cells produced either IFNγ (4.6% of CD8 T cells) or TNFα (4.5% of CD8 T cells) after stimulation with peptide-pulsed T2 cells (Fig. 4c). Of the cytokine producing T cells, 79% produced both IFNγ and TNFα, while the percentage of cells producing either IFNγ + TNFα + IL-2, IFNγ + IL-2, or TNFα + IL-2 were equally distributed with 7% in each category (Fig. 4c). Thus, tumor-specific T cells expanded by dynabeads are functional, capable of both cytokine secretion and lysis of target cells.

Fig. 4.

Tumor-specific T cells expanded by Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander are functional dynabead-expanded T cells containing high percentage of hTERTp30-specific T cells were analyzed for ability to secrete IFNγ upon stimulation with hTERTp30 peptide. a Percentage of IFNγ producing hTERTp30 tetramer-specific T cells in cultures expanded by either Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander or Dynabeads® CD3/CD28/CD137 T-cell expander. One representative experiment out of 2 is shown. b Specific lysis of peptide-pulsed T2 cells by expansion cultures (Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander or Dynabeads® CD3/CD28/CD137 T-cell expander) containing high percentage of hTERTp30-specific T cells. One representative experiment out of 2 is shown. c Simultaneous production of IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2 in a Dynabeads® CD3/CD28 expanded culture stimulated with hTERTp988 peptide. Cells stimulated with HIV control peptide did not produce cytokines. One representative experiment out of 2 is shown

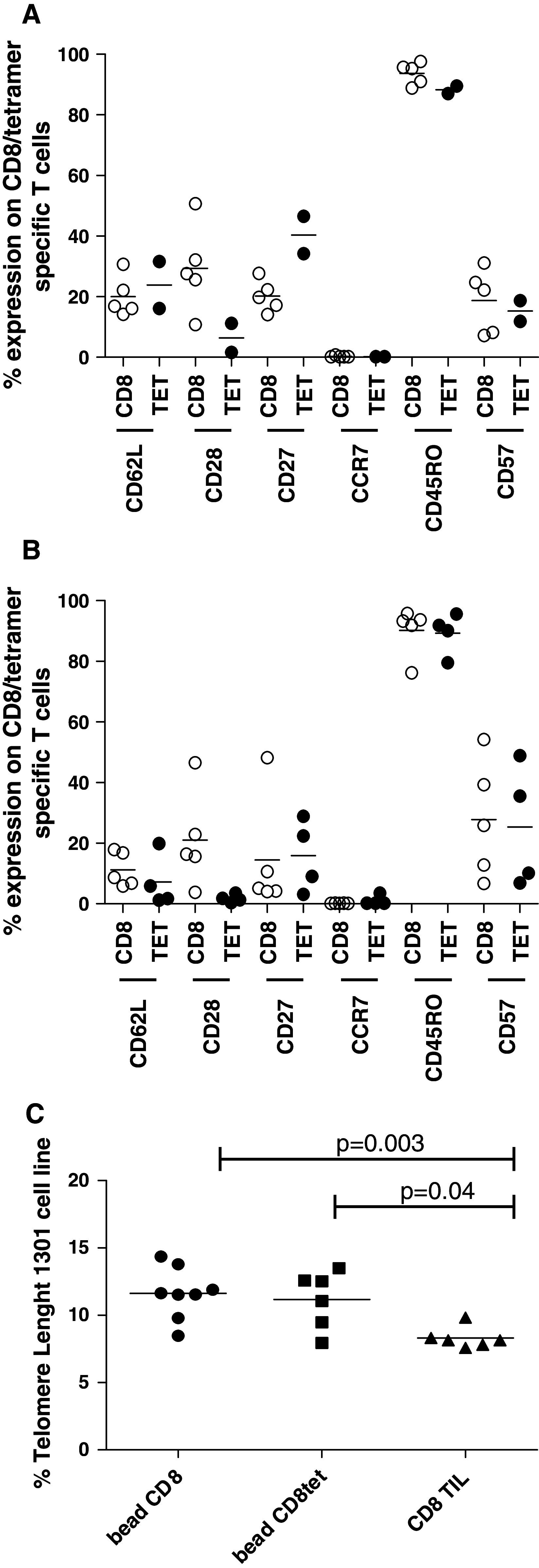

Phenotype and telomere length of T cells expanded by Dynabead® CD3/CD28 T-cells expander

Next, we evaluated expression of various phenotypic markers on CD8+ or tetramer-specific T cells either after 14 days restimulation period or after both 14 days restimulation and 12 days bead expansion. We analyzed restimulation cultures that were stimulated with peptides only as well as cultures stimulated with peptide-pulsed DCs from both a melanoma and a renal cell carcinoma patients. The peptides used for restimulation were hTERTp30, hTERTp988, Sur1M2, and K9V. After 14 days of restimulation, we observed an intermediate expression of CD28, CD62L, CD27, and CD57, a high expression of CD45RO, and a low expression of CCR7 on CD8 T cells (Fig. 5a, open circles). For the tetramer-specific T cells, the expression was similar except for CD28 and CD27, which was, respectively, lower and higher than on the CD8 T cells (Fig. 5a, filled circles). When the cultures were both restimulated (14 days) and bead expanded (12 days), the expression of CD62L, CD27, and CD28 was decreased compared to restimulated cultures (14 days), the expression of CD57 was increased, while CD45RO expression remained constant on CD8 T cells (Fig. 5b, open circles). For the tetramer-specific T cells, again most markers demonstrated similar expression profile; however, the CD28 expression was lower than on total CD8 T cells (Fig. 5b, filled circles). These results indicate that T cells display a more differentiated phenotype after they have undergone bead expansion; however, the majority is still not of late-stage effector T-cell phenotype. To analyze the replication potential of bead-expanded T cells, we analyzed the telomere length of these cells and compared the results with the telomere length of TIL cultures produced by conventional methods. Evaluation of telomere length revealed that PBMC ± bead expansion had significantly longer telomers compared to TILs (pooled data from independent cultures analyzed either before or after rapid expansion) (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, there was no difference in telomere length between the total CD8+ population and the tetramer-specific T cells (hTERTp988, hTERTp30) among the bead-expanded PBMCs, indicating that tumor-specific T cells after bead expansion posses a growth potential comparable to the general CD8+ T cell population (Fig. 5c). Overall, this reflects a superior expansion potential of bead-expanded T cells compared to TILs.

Fig. 5.

Phenotype and telomere length of Dynabead® CD3/CD28-expanded T cells. a Cells were restimulated for 14 days with either peptide only (hTERTp988; 2 individual cultures from the same renal cell carcinoma patient) or peptide-pulsed DCs (hTERTp30, Sur1M2, and K9V; 3 individual cultures from the same melanoma patient) and analyzed for expression of phenotypic markers on CD8 T cell (open circles) and tetramer-specific T cells (filled circles). b Cells were restimulated for 14 days as described above and were afterward expanded by Dynabead® CD3/CD28 T-cell expander for 12 days. Cells were analyzed for expression of phenotypic markers on CD8 T cells (open circles) and tetramer-specific T cells (filled circles). c PBMCs ± bead expansion and TIL cultures before and after rapid expansion were analyzed for telomere length as described in “Materials and methods”. Shown are “bead CD8” (3 samples before and 5 after bead expansion), “bead CD8tet” (2 samples before and 4 after bead expansion), and “CD8 TIL” (4 samples before and 2 after rapid expansion). Results are depicted as mean + range

Discussion

It was previously shown that high numbers of T cells can be generated in vitro for ACT to cancer patients either by expanding TILs or PBMCs [7–11, 13, 24–28], and tumor regression has been observed after adoptive transfer of both in vitro expanded TILs [24, 26, 29] and PBMCs [7, 11]. Here we investigated the possibility of including a restimulation step prior to bead expansion to boost the tumor-specific response generated by in vivo vaccination. We demonstrated that tumor-specific responses can be boosted by peptide or DC stimulation to increase the frequency in T-cell cultures prior to bead expansion. Restimulation led to a considerable increase in total number of tumor-specific T cell after bead expansion. On the contrary, when no restimulation is used many tumor-specific responses will be of very low frequency and likely lost during the bead expansion procedure. Thus, inclusion of restimulation prior to bead expansion serves as a valuable method to boost the in vivo-generated tumor-specific response. This was also demonstrated in a study by Rasmussen et al. [13] showing >100-fold increase in expansion of hTERT-specific T cells when a restimulation step with peptides was included.

For clinical applications, the “breadth” of the response is likely to be important for clinical efficacy, since immune targeting against one antigen may lead to immune escape variants [30]. In a clinical trial treating malignant melanoma patients with autologous DCs pulsed with the MART-127–35 immunodominant epitope, the frequency of IFNγ antigen-specific T cells did not correlate with clinical responses [31]. However, spreading of immune reactivity to other melanoma antigens was evident in a patient with a complete response, indicating that a broad response is preferable for obtaining clinical responses. Moreover, therapeutic vaccination of advanced renal cell carcinoma patients with multiple naturally presented tumor-associated peptides seems to have clinical benefit [32]. Patients with detectable T-cell responses against peptides included in the vaccine had better disease control and overall survival as compared to patients without such response. Therefore, expansion of cultures with multiple specificities is preferable, and we aim to induce a broad response based on many T-cell specificities.

We demonstrate here the feasibility of using DCs, generated for in vivo vaccination, to restimulate the tumor-specific responses. This approach holds a number of advantages: (1) vaccine-generated DCs are GMP grade, and can thus readily be used for restimulation, (2) DCs can present a broad spectrum of tumor antigens simultaneously, and, therefore, potentially boost a broad anti-tumor response; finally, (3) the “prime” and “boost” material will be identical, resulting in optimal restimulation. In this study, we demonstrated that both DCs pulsed with tumor-specific peptides or tumor lysate from allogeneic tumor cell lines can be used as restimulators and that more than one tumor-specific response can be boosted in the same culture. This allow inclusion of both HLA-A2+ and HLA-A2− patients and illustrates that DCs are indeed very suitable as restimulators. In a recent murine study, it was demonstrated that DCs pulsed with tumor lysate can be used to activate leukemia-specific CTLs prior to anti-CD3/CD28 expansion [33]. Adoptive transfer of these cells cured 80% of leukemia bearing mice. Furthermore, in vivo vaccination with tumor lysate-pulsed DCs prior to in vitro splenocyte-DC culture and bead expansion resulted in 2–6-fold increase in specific T cells compared to cells from non-vaccinated animals. In vivo priming of a tumor-specific response by vaccination is important to ensure that a tumor-specific response is available for in vitro restimulation. The importance of this step was also illustrated in a study by Dang et al. [12] in which it was shown that patients vaccinated with a HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccine had a >25-fold higher frequency of antigen-specific T cells compared to unvaccinated patients. However, spontaneous tumor-specific responses could also serve as starting material for restimulation or alternatively tumor-specific T cells could be primed in vitro and afterward expanded by anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation. Here, we demonstrated that both peptide-pulsed and tumor lysate-loaded (allogeneic) DCs can be used in restimulation cultures to boost the tumor-specific response after the response was initiated by vaccination with that particular DC preparation. Most likely, autologous tumor lysate-loaded- and mRNA-transfected DCs can function in a similar way. Thus, the antigen source can be selected depending on the given clinical setting. Importantly, the restimulation and expansion of tumor-specific T cells were performed using cell material from patients with late-stage cancers non-responsive to standard treatment, demonstrating the possibility of expanding T cells from immune suppressed individuals. Also, hTERT and p53 represent highly tolerized antigens illustrating that tolerance toward these antigens can be overcome by this procedure.

We demonstrated that the tumor-specific T cells expanded by dynabeads were functional, possessing cytotoxic abilities and producing IFNy and TNFα. This is in line with earlier demonstrations [34, 35] and shows that T cells expanded by this procedure are indeed functionally competent. The addition of antibodies to CD137 on the expansion beads did not improve the functional capabilities of the tumor-specific T cells, in terms of IFNγ secretion and cytotoxicity, supporting the choice of Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28, which is still not available including CD137 antibodies. Also, we demonstrated that dynabead-expanded T cells have intermediate expression of CD62L, CD28, CD27, and CD57, while the CCR7 expression was low indicating that these T cells are of effector/effector-memory phenotype, but still not very late-stage effector T cells, and do posses the potential to expand in vivo. Furthermore, the telomere analysis revealed a relatively longer telomere length on bead expanded PBMCs compared to TILs reflecting a better expansion potential of these cells after adoptive T-cell transfer. Importantly, we observed no differences in the telomere length between tumor-specific bead-expanded T cells (hTERTp988 and hTERTp30) and the total CD8 population of bead-expanded T cells illustrating that tumor-specific T cells are not more exhausted than CD8 T cells. Telomere length has been shown to correlate with clinical efficacy in adoptive transfer of TILs to patients with metastatic melanoma [36]. Thus, the characteristics described for bead-expanded PBMCs are indicative for the ability of these cells to persist in vivo, making them well suited for adoptive T-cell transfer. The observed differences in telomere length is most likely reflecting differences in the CD8 T cells originating from the different compartments, since the telomere reduction per cell division has been reported to be approximately 60 bp [37], requiring around 17 divisions (equaling 217 = 131072-fold expansion) to measure a 1-Kb reduction in telomere length. This number of expansion is by far exceeding the numbers observed for both TILs and bead-expanded PBMCs.

Finally, we have tested the feasibility of scaling up the restimulation cultures for clinical applications. In two independent experiments, it was possible to simultaneous restimulate PBMCs with up to four different viral peptide antigens in large cultures (up to 40 ml), indicating the feasibility of large-scale restimulations in a future clinical trial.

Taken together, we have demonstrated the feasibility of boosting the anti-tumor-specific T-cells response by an in vitro restimulation culture using either peptides or DCs generated for vaccination—and following expand these cultures using Dynabeads® ClinExVivo™CD3/CD28 to obtain large numbers of functional tumor-specific T cells for ACT.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tina Juanita Seremet for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Danish Council for Strategic Research and the Danish Cancer Society.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Marie Klinge Brimnes and Anne Ortved Gang have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donia M, Junker N, Ellebaek E, Andersen MH, Straten PT, Svane IM (2011) Characterization and comparison of “standard” and “young” tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for adoptive cell therapy at a Danish Translational Research Institution. Scand J Immunol [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Rosenberg SA, Dudley ME. Adoptive cell therapy for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blattman JN, Greenberg PD. Cancer immunotherapy: a treatment for the masses. Science. 2004;305:200–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1100369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pure E, Allison JP, Schreiber RD. Breaking down the barriers to cancer immunotherapy. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1207–1210. doi: 10.1038/ni1205-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neurauter AA, Bonyhadi M, Lien E, et al. Cell isolation and expansion using Dynabeads. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2007;106:41–73. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Porter DL, Levine BL, Bunin N, et al. A phase 1 trial of donor lymphocyte infusions expanded and activated ex vivo via CD3/CD28 costimulation. Blood. 2006;107:1325–1331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rapoport AP, Stadtmauer EA, Aqui N, et al. Restoration of immunity in lymphopenic individuals with cancer by vaccination and adoptive T-cell transfer. Nat Med. 2005;11:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/nm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapoport AP, Stadtmauer EA, Aqui N, et al. Rapid immune recovery and graft-versus-host disease-like engraftment syndrome following adoptive transfer of costimulated autologous T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4499–4507. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rapoport AP, Aqui NA, Stadtmauer EA, et al. Combination immunotherapy using adoptive T-cell transfer and tumor antigen vaccination on the basis of hTERT and survivin after ASCT for myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:788–797. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-299396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson JA, Figlin RA, Sifri-Steele C, Berenson RJ, Frohlich MW. A phase I trial of CD3/CD28-activated T cells (Xcellerated T cells) and interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3562–3570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dang Y, Knutson KL, Goodell V, et al. Tumor antigen-specific T-cell expansion is greatly facilitated by in vivo priming. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1883–1891. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen AM, Borelli G, Hoel HJ, et al. Ex vivo expansion protocol for human tumor specific T cells for adoptive T cell therapy. J Immunol Methods. 2010;355:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trepiakas R, Berntsen A, Hadrup SR, et al. Vaccination with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with multiple tumor antigens for treatment of patients with malignant melanoma: results from a phase I/II trial. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:721–734. doi: 10.3109/14653241003774045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berntsen A, Trepiakas R, Wenandy L, et al. Therapeutic dendritic cell vaccination of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a clinical phase 1/2 trial. J Immunother. 2008;31:771–780. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181833818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toebes M, Coccoris M, Bins A, et al. Design and use of conditional MHC class I ligands. Nat Med. 2006;12:246–251. doi: 10.1038/nm1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodenko B, Toebes M, Hadrup SR, et al. Generation of peptide-MHC class I complexes through UV-mediated ligand exchange. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1120–1132. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen MH, Bonfill JE, Neisig A, et al. Phosphorylated peptides can be transported by TAP molecules, presented by class I MHC molecules, and recognized by phosphopeptide-specific CTL. J Immunol. 1999;163:3812–3818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapoor V, Hakim FT, Rehman N, Gress RE, Telford WG. Quantum dots thermal stability improves simultaneous phenotype-specific telomere length measurement by FISH-flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2009;344:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batliwalla FM, Damle RN, Metz C, Chiorazzi N, Gregersen PK. Simultaneous flow cytometric analysis of cell surface markers and telomere length: analysis of human tonsilar B cells. J Immunol Methods. 2001;247:103–109. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid I, Dagarag MD, Hausner MA, et al. Simultaneous flow cytometric analysis of two cell surface markers, telomere length, and DNA content. Cytometry. 2002;49:96–105. doi: 10.1002/cyto.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmid I, Jamieson BD. Assessment of telomere length, phenotype, and DNA content. Curr Protoc Cytom Chapter. 2004;7:26. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0726s29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadrup SR, Toebes M, Rodenko B, et al. High-throughput T-cell epitope discovery through MHC peptide exchange. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;524:383–405. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-450-6_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dudley ME, Yang JC, Sherry R, et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudley ME, Gross CA, Langhan MM, et al. CD8+ enriched “young” tumor infiltrating lymphocytes can mediate regression of metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6122–6131. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:917–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Robbins PF, et al. Cell transfer therapy for cancer: lessons from sequential treatments of a patient with metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2003;26:385–393. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200309000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pawelec G. Tumour escape: antitumour effectors too much of a good thing? Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:262–274. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0469-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, et al. Determinant spreading associated with clinical response in dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:998–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rini BI, Eisen T, Stenzl A et al IMA901 Multipeptide vaccine randomized international phase III trial (IMPRINT): a randomized, controlled study investigating IMA901 multipeptide cancer vaccine in patients receiving sunitinib as first-line therapy for advanced/metastatic RCC. [abstract] Rini BI, Eisen T, Stenzl A et al. ASCO Annual Meeting 2011; Abstract No: TPS183

- 33.Ghosh A, Wolenski M, Klein C, Welte K, Blazar BR, Sauer MG. Cytotoxic T cells reactive to an immunodominant leukemia-associated antigen can be specifically primed and expanded by combining a specific priming step with nonspecific large-scale expansion. J Immunother. 2008;31:121–131. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31815aaf24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hami LS, Green C, Leshinsky N, Markham E, Miller K, Craig S. GMP production and testing of Xcellerated T cells for the treatment of patients with CLL. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:554–562. doi: 10.1080/14653240410005348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalamasz D, Long SA, Taniguchi R, Buckner JH, Berenson RJ, Bonyhadi M. Optimization of human T-cell expansion ex vivo using magnetic beads conjugated with anti-CD3 and Anti-CD28 antibodies. J Immunother. 2004;27:405–418. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200409000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen X, Zhou J, Hathcock KS, et al. Persistence of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in adoptive immunotherapy correlates with telomere length. J Immunother. 2007;30:123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211321.07654.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rufer N, Migliaccio M, Antonchuk J, Humphries RK, Roosnek E, Lansdorp PM. Transfer of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene into T lymphocytes results in extension of replicative potential. Blood. 2001;98:597–603. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.3.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]