Abstract

We have reported that calcitonin receptor (CTR) is widely expressed in biopsies from the lethal brain tumour glioblastoma by malignant glioma and brain tumour-initiating cells (glioma stem cells) using anti-human CTR antibodies. A monoclonal antibody against an epitope within the extracellular domain of CTR was raised (mAb2C4) and chemically conjugated to either plant ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIPs) dianthin-30 or gelonin, or the drug monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE), and purified. In the high-grade glioma cell line (HGG, representing glioma stem cells) SB2b, in the presence of the triterpene glycoside SO1861, the EC50 for mAb2C4:dianthin was 10.0 pM and for mAb2C4:MMAE [antibody drug conjugate (ADC)] 2.5 nM, 250-fold less potent. With the cell line U87MG, in the presence of SO1861, the EC50 for mAb2C4:dianthin was 20 pM, mAb2C4:gelonin, 20 pM, compared to the ADC (6.3 nM), which is >300 less potent. Several other HGG cell lines that express CTR were tested and the efficacies of mAb2C4:RIP (dianthin or gelonin) were similar. Co-administration of the enhancer SO1861 purified from plants enhances lysosomal escape. Enhancement with SO1861 increased potency of the immunotoxin (>3 log values) compared to the ADC (1 log). The uptake of antibody was demonstrated with the fluorescent conjugate mAb2C4:Alexa Fluor 568, and the release of dianthin-30:Alexa Fluor488 into the cytosol following addition of SO1861 supports our model. These data demonstrate that the immunotoxins are highly potent and that CTR is an effective target expressed by a large proportion of HGG cell lines representative of glioma stem cells and isolated from individual patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-017-2013-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Calcitonin receptor, Immunotoxins, Targeting, High-grade glioma cell lines, Glioblastoma

Introduction

Successful treatment of recalcitrant tumours remains one of the great challenges of cancer research. One such recalcitrant tumour, glioblastoma (GBM), is a deadly brain tumour (grade 4 astrocytoma [1]). One of the underlying features of GBM is the invasive potential of brain tumour initiating cells (BTIC) [2] which are regarded as clones of cells with stem-like properties (glioma stem cells) [3, 4]. These cells are considered to have the capacity to differentiate into a variety of cell types [5] including endothelial cells and pericytes, which are essential for the maintenance and expansion of the solid tumour. Thus, it is considered that these stem-like cells provide the malignant basis of glioblastoma and hence represent potentially important targets for treatment.

Conventional chemo- and radiotherapies, cyto-reductive surgery and trialed treatment modalities, including Avastin (anti-VEGF antibody) therapy, have had minimal impact on the mean survival after diagnosis, which remains low at just 14–17 months [6].

The deployment of antibody drug conjugates (ADC) to treat recalcitrant tumours is a relatively recent research strategy in which the number of lead ADCs entering clinical trials has increased rapidly [7–9]. Successful treatment is partly dependent on the properties of the antibody and its target, for efficient delivery of the drug into the tumour cell, as well as the efficacy of the drug itself. Recently, an ADC based on an anti-EGFRvlll antibody (ABT-806) conjugated to monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF) resulting in an ADC (ABT-414) has been demonstrated to be effective in 22% of GBM patients in a phase I study [10].

Immunotoxins made from antibodies conjugated with either bacterial or plant toxins have been investigated for many years and there are examples of the former that have reached clinical trials. However, studies involving plant-based immunotoxins have been less frequent and the development of ADCs for clinical trials is more advanced. However, recent advances in immunotoxin research are beginning to change this preference. Firstly, plant toxins such as the ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIP) dianthin-30 [11] and gelonin [12] (originally extracted from seeds) are now synthesised as functional recombinant proteins. Secondly, when administered in combination with enhancers of lysosomal escape (non-toxic co-factors) such as the triterpene glycoside SO1861 [13], there is a decrease by several orders of magnitude in the effective concentration (EC50) for cytotoxicity. This enhancer is a plant triterpene glycoside, purified from the plant Saponaria officinalis L. [13], with specific structural features that enhance the cytotoxicity of immunotoxins conjugated with RIPs. SO1861 has a triterpenoidal skeleton of oleanane type and two sugar side chains (bisdesmosidic) attached to it at positions C-3 and C-28 [14]. Such enhancers interact at non-toxic concentrations with the immunotoxin within the endosomal or lysosomal compartment of the target cells [14] and promote release into the cytosol [15] where the toxin targets ribosomes.

Our understanding of the role of calcitonin receptor (CTR) in cell physiology has been evolving over the last 20 years with new knowledge of the mechanisms of agonist bias [16] and an increasing appreciation of the broad range of tissues in specific physiological states, in which CTR is expressed. For instance, CTR expression may be transitory in wound healing [17] and in neurons of the gut around birth [18]. It is expressed by activated lymphocytes [19, 20] and during foetal development [21–23]. Recently, we have proposed that CTR is externalised during the pre-apoptotic cell stress response [24].

CTR is a target of interest because it is expressed by malignant tumour cells of the brain tumour glioblastoma [25]. Furthermore, CTR is also expressed in other malignancies including multiple myeloma [26], leukaemia [17], lymphoma [27], bone tumours [28, 29], breast [30] and prostate cancers [31, 32], and medullary thyroid cancers [33]. The function(s) of CTR in the contexts of these different cancers is largely unknown; however, an anti-apoptotic or survival activity has been proposed together with metabolic reprogramming [27].

Important considerations in the design of immunotoxins for the treatment of cancers include the sufficient expression of the target receptor on the surface of BTICs compared to other exposed tissues [34] and internalisation of receptors with the immunotoxin attached. High-grade glioma (HGG) cell lines [35] derived from GBM represent BTICs and include the subtypes, pro-neural, neural, classical and mesenchymal, classified according to gene profiling. Five HGG cell lines (BAH1, JK2, PB1, SB2b and WK1 [36]) out of the 12 originally tested (~40%) were shown to express human CTR (hCTR) on immunoblots and 4 of these plus 2 others from a separate source were included in this study. CTR-positive HGG cell lines represent each of the subtypes listed above. These HGG cell lines, when injected intracranially into immunodeficient mice, form GBM-like tumours [37].

In this study CTR is evaluated as a potential target expressed by HGG cell lines and as an uptake mechanism for internalisation of immunotoxins. For comparison, the efficacies of two anti-CTR immunotoxins based on an anti-CTR antibody conjugated to the plant toxins dianthin-30 and gelonin, and an ADC with monomethyl auristatin E [38], are reported here with and without SO1861. Monomethyl auristatin is included in this study, as it is frequently incorporated into ADCs tested in clinical trials and reported in the literature [7–9] due to its toxicity as an anti-microtubule agent.

Materials and methods

High-grade glioma cell lines

In total, 7 HGG cell lines out of 14 screened expressed detectable levels of calcitonin receptor as determined by immunoblot. These include four (JK2 [39], PB1 [40], SB2b [41] and WK1 [36, 41]) from the QIMR-Berghofer Medical Research Institute (Brisbane, Australia). Two further cell lines GBM-4 and GBM-L2 [42] were obtained from the Monash Institute of Medical Research (Professor TG Johns). These lines were all grown on Matrigel (Corning, USA)-coated plastic surfaces under serum-free conditions in StemPro® NSC SFM—Serum-Free Human Neural Stem Cell Culture Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with EGF, FGF2 and glutaMAX plus penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and cultured at 37 °C in a 95% humidified air and 5% CO2 atmosphere [37].

The cell line U87MG, described extensively in the literature and derived from glioblastoma, was also included to provide a reference point for other published studies. U87MG was maintained in DMEM-F12/10% FBS plus penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) grown at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. For efficacy studies in the 96-well format and growth in chamber slides for confocal analysis, U87MG cells were cultured on Matrigel under identical serum-free conditions used for HGG cell lines, in StemPro® NSC SFM.

Ribosome-inactivating proteins (RIP) and the drug monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE)

The RIP dianthin-30 [His6] was synthesised as a recombinant protein in E. coli and purified by affinity [nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose] chromatography [43]. rGelonin was a gift from Professor Michael G Rosenblum (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Texas) which was synthesised and purified from E. coli [44]. MMAE (OSu-Glu-VC-PAB-MMAE) was purchased from Concortis Biosystems Corp. (USA).

The enhancer triterpene glycoside SO1861

The extraction and isolation of the enhancer SO1861 from plant roots of Saponaria officinalis L. caryophyllacea has been described [13]. The chemical structure of SO1861 has been solved and will be published in detail elsewhere (Dr Alexander Weng, personal communication). At 3 µg/mL used in the growth assays, SO1861 is slightly toxic resulting in 10% retardation of cell proliferation. For U87MG cells, the concentration used was 1 µg/mL.

Antibodies

These studies involved the use of a mouse monoclonal anti-human CTR antibody (mAb 46/08-2C4-2-2-4 [IgG1]) directed against an extracellular epitope [Welcome Receptor Antibodies (WRA), Melbourne] [24]. MAb1H10 (IgG2A) was raised against a cytoplasmic epitope (mAb 31/01-1H10, WRA, Melbourne; also distributed as MCA 2191 by BioRad, UK). These antibodies have been previously validated (in the supplementary materials linked to [24]) and further data published elsewhere [25].

Conjugation of toxins to mAb2C4

Dianthin-30[His6] or gelonin was conjugated to mAb2C4 using succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio) propionate (SPDP, Thermo Fisher Scientific). This cross-linking procedure introduced a covalent disulphide bridge between the toxins and the monoclonal antibody. In the case of dianthin-30[His6] and mAb2C4, both proteins (molar ratio 1:1) were modified by SPDP and the molar ratios that were considered for their chemical reaction were protein:cross-linker of 1:3, 1:6 and 1:12. In the case of gelonin and mAb2C4, in a first attempt both proteins (molar ratio 1:1) were modified by SPDP at a molar ratio protein:cross-linker of 1:6. In a second and third attempt, only mAb2C4 (molar ratio gelonin:mAb2C4 of 3:1) was modified by SPDP at a molar ratio of protein:cross-linker of 1:3 and 1:6.

In brief, proteins (dianthin-30[His6], gelonin and mAb2C4) were equilibrated in PBS-EDTA buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide, pH 7.5) using a 5 mL Zeba polyacrylamide de-salting columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were modified by the addition of SPDP (20 mM in DMSO) for 60 min at room temperature. Proteins were desalted again using 5 mL Zeba de-salting columns and then SPDP-modified toxin was reduced with the addition of dithiothreitol (DTT, final concentration of 50 mM) for 30 min at room temperature. DTT was removed using a Zeba de-salting column. Monoclonal antibody and reduced toxins (or non-modified gelonin containing one available cysteine) were allowed to react for 18 h at room temperature. The conjugates were stored at 4 °C pending further purification.

Monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE) was conjugated to mAb2C4 via the cross-linker OSu-Glu-VC-PAB as indicated by the manufacturer (Concortis Biosystems Corp., USA). The chemical reaction was performed with a molar ratio mAb2C4:OSu-Glu-VC-PAB-MMAE of 1:7. The antibody was equilibrated in the conjugation buffer 1 (CB1, 50 mM potassium phosphate, 50 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM EDTA, pH 6.5) using a 5 mL Zeba de-salting column. The antibody was modified by the addition of OSu-Glu-VC-PAB-MMAE (10 mM in DMA). Further organic solvent was added up to 10% (v/v) DMA and the cross-linking reaction run for 18 h at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by exchanging the CB1 with the conjugation buffer 2 (CB2, 50 mM sodium succinate, pH 5.0) using a 5 mL Zeba de-salting column. Antibody–drug conjugate was stored at 4 °C pending further purification steps.

Purification of immunotoxins and the ADC

MAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6]

The first step in purification involved chromatography with a nickel-NTA agarose matrix (Life Technologies).

In brief, 20 mM imidazole in buffer [50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM sodium chloride (pH 8.0)] was added to the crude cross-linked reaction mix, mixed with nickel-NTA agarose (3 mL bed volume) and equilibrated with inversion at 25 °C for 60 min. The bound matrix was poured into a 10 mL column, with gravity feed and washed with three column volumes of binding buffer (as above). The bound products were eluted with 250 mM imidazole in buffer. The eluted proteins (mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6] and dianthin-30[His6]) were dialysed against PBS overnight at 6 °C.

The second step of purification was achieved with chromatography on a peptide affinity column (thiopropyl Sepharose 6B, prepared by Mimotopes, Clayton, Australia) using the peptide sequence (CSGS-PSEKVTKYCDEKGVWFK, synthesised by Mimotopes) equivalent to the extracellular epitope of human CTR that binds mAb2C4. This step excluded antibody products in which the binding determinants for the peptide sequence had been compromised during the conjugation step. The dialysed material was passed down the affinity column, washed in three volumes of 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), eluted with 100 mM glycine (pH 2.2) and the fractions neutralised with 10% of the collected volume with 1 M TRIS (pH 9.0). These fractions were dialysed overnight in PBS and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filters (10 kD cut off). The yield of conjugated material after purification was approximately 8%, compared to the initial amounts of dianthin-30[His6] and mAb2C4 used in the conjugation.

MAb2C4:gelonin

The conjugated crude product mAb2C4:gelonin was purified in a two-step process, firstly with the affinity column described above. The second chromatographic step was dependent on the binding of the product to HiTrap Blue HP matrix (GE Healthcare) [44, 45] and elution with sodium chloride. The yield of the final product (mAb2C4:gelonin) was similar to that of mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6].

MAb2C4:MMAE

The conjugated crude solution of mAb2C4:MMAE was also purified by two chromatographic steps, firstly with the peptide affinity column described above. This purification step eliminates inactive binding products of mAb2C4:MMAE that might have been generated during the conjugation as they pass through within the void volume. The second step in purification was chromatography on a hydrophobic interactive matrix (HiTrap Phenyl HP, GE Healthcare) and the active fraction was eluted with a reverse ammonium chloride gradient.

Growth/cytotoxicity assays in the 96-well format

For efficacy studies in the 96-well format all cell lines were grown on Matrigel (Corning, USA) under serum-free conditions in StemPro® NSC SFM (Life Technologies/Thermo Fisher Scientific) with growth factors and seeded at 2500 cells per well. 2–3 h after plating the cells, additions such as SO1861 and immunotoxins (mAb 2C4:dianthin-30[His6], mAb2C4:gelonin) or ADC (mAb2C4:MMAE) were made. Control plates included mAb2C4 with SO1861 or immunotoxin without SO1861. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 days (U87MG) or 6 days (HGG cell lines). Measurements of total lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, lysed cells) and residual LDH (non-lysed samples) were performed in triplicate. LDH was measured using an LDH cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche) and read on a FLUOstar OPTIMA (BMG Labtech).

Confocal microscopy of HGG cell lines and immunofluorescence with multichannel detection

The confocal analysis of the uptake of mAb2C4 into HGG cell lines was accomplished with mAb2C4 labelled with Alexa Fluor 568 (AF568, Thermo Fisher Scientific) using conjugation of lysines with NHS succinimidyl esters of AF568 [24].

HGG cell lines were cultured (described above) to 50–80% confluence on four-well glass slides (Lab Tek II chamber slides, NUNC) coated with Matrigel (Corning, US) in a humidified incubator (5% CO2) at 37 °C and then washed with media without growth factors. MAb2C4:AF568 (1 µg/mL) was added to 1 mL of fresh growth medium and the chamber slides incubated for 24 h in the incubator.

Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 30 min and then washed twice with PBS. Cells were blocked with 5% normal goat serum/1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h.

Slides of fixed cells were incubated overnight at 6 °C with rabbit anti-LAMP1 antibody (Cell Signalling) that detects lysosomes. The secondary antibody used was goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (4 µg/mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The samples were then mounted using DAPI aqueous mount (Prolong Gold, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to visualise the nuclei and dried at RT for several days in the dark. The samples were imaged by confocal microscopy (objectives 20× and 63×) on a Zeiss Imager Z1/LSM 510 Meta confocal laser scanning system using Zen software. Images (LSM format) were captured in a single focal plane (optical sections of 0.7 µm nominal thickness) or using the Z-series feature where ~15 optical sections were compressed (devolution using LSM Image Browser, Zeiss) to create a single plane image (TIFF format) equivalent to approximately 10 µm tissue thickness.

Live cell imaging

U-87 MG (ATCC® HTB-14™) cells were seeded (2000/dish) in Ibidi µ-Dishes (35 mm, low, Martinsried, Germany) and cultured in 2 mL Dulbecco’s MEM supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. After 92 h, the medium was removed and 1 mL fresh culture medium was added. Dianthin:AF488 (100 nM) was added and cells were incubated overnight for an incubation period of 18 h. Dianthin was labelled beforehand with Alexa Fluor 488 5-TFP ester (Life Technologies) as described previously [46].

The live cell imaging marker pHrodo™ Red Dextran (final concentration 40 µg/mL, Life Technologies) was added 6 h before the end of the incubation period. pHrodo™ Red Dextran is a live cell imaging marker for acidic intracellular compartments such as lysosomes. Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) was added 30 min before the end of the incubation period. Cells were washed with PBS (3×), covered with 1 mL live cell imaging solution (Life Technologies), supplemented with 1% FBS and 20 mM d-glucose and analysed using an LSM780 laser scanning microscope, Axio Observer Z1 with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 Oil Objective (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Cells were maintained at 37 °C throughout the experiment. Cells were continuously monitored (supplementary video) and 36 s after the start of the analyses SO1861 was added to a final concentration of 5 µg/mL. To determine the SO1861-induced endosomal escape of dianthin:AF488 into the cytosol, regions of interest were assigned for individual cells and the increase of intensity was determined off-line using ZEN 2.3 lite software (Carl Zeiss).

Results

The principal aim of this study was to synthesize conjugates of mAb2C4 antibody including the immunotoxins mAb2C4:dianthin-30, mAb2C4:gelonin and the antibody:drug conjugate (ADC) mAb2C4:MMAE, for comparison of their efficacies to promote cell death in high-grade glioma cell lines and U87MG. The validation of mAb2C4, which binds to an extracellular linear epitope (epitope 4) of human CTR, has been presented elsewhere [24].

Expression of calcitonin receptor protein was determined by immunoblot

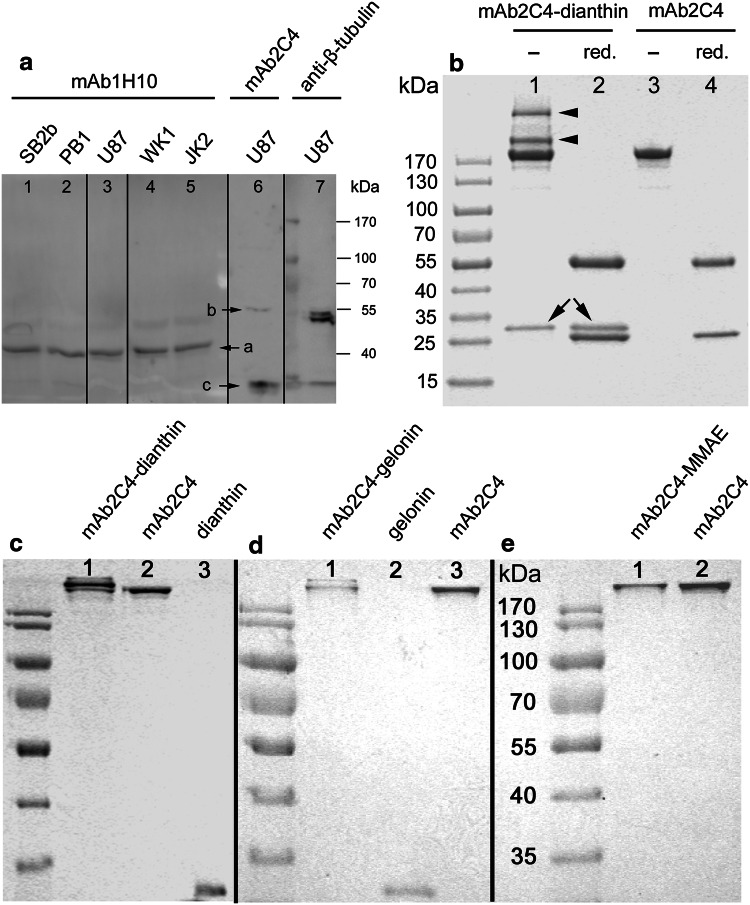

In Fig. 1a is shown expression of CTR protein by HGG cell lines and the cell line U87MG, probed with the antibody mAb1H10 which recognises an intracellular epitope (band ‘a’). In U87MG cells probed with mAb2C4 (band ‘b’), the target of MW ~55 kD is shown. Band ‘c’ is a product of degradation of CTR.

Fig. 1.

Expression of CTR by different cell lines, gel electrophoresis of samples taken during conjugation of mAb2C4 to dianthin-30[His6] and final products for the syntheses of mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6], mAb2C4:gelonin and mAb2C4:MMAE. a Immunoblot of whole cell lysates prepared from SB2b (lane 1), PB1 (lane 2), U87MG (lane 3), WK1 (lane 4) and JK2 (lane 5) stained with mAb1H10 anti-human CTR antibody and U87 stained with mAb2C4 (lane 6); U87MG stained with anti-β-tubulin antibody (lane 7). It is likely that band ‘b’ represents the full length hCTR protein without glycosylation and band ‘a’ the N-terminal truncated form with the absence of epitope 4 to which mAb2C4 binds. Band ‘c’ represents the extracellular domain (~14 kD) cleaved from the 40 kD protein. b Samples were assayed following the conjugation reaction (the molar ratio of proteins:cross-linker SPDP was 1:6 and the molar ratio of activated dianthin-30[His6] and mAb2C4 was 1:1). The sample was non-reduced (lane 1) or reduced (lane 2), and for controls mAb2C4 was non-reduced (lane 3) or reduced (lane 4). The mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6] conjugates are indicated with an arrowhead and dianthin-30 with arrows. c Purified mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6] (lane 1) compared to mAb2C4 (lane 2) and dianthin-30[His6] (lane 3). d Purified mAb2C4:gelonin (lane 1) compared to gelonin (lane 2) and mAb2C4 (lane 3). e Purified mAb2C4:MMAE (lane 1) compared to mAb2C4 (lane 2)

Syntheses and purification steps for immunotoxins and ADC

Chromatography with the peptide affinity column, constructed with the peptide sequence used for immunization and the cloning/expression of mAb2C4, was used for purification of each conjugate (immunotoxin or ADC), and mAb2C4:AF568 (see Fig. 3) as the bound material retains the capacity to bind to epitope 4 of CTR. Any antibody with compromised binding capacity passes through in the flowthrough during chromatography.

Fig. 3.

Typical uptake of mAb2C4:AF568 (red) by HGG cell lines and intracellular localisation in relation to the distribution of LAMP1-positive (green) lysosomes within the cytoplasmic domain and to nuclei stained with DAPI (blue). a Merged image following the uptake of mAb2C4:AF568 (red) by cell line JK2. b Merged image following the uptake of mAb2C4:AF568 by the cell lines SB2b. c Image of PB1 (red channel). d Merged image of PB1. e Image of U87MG (red channel). f Merged image of U87MG. A subset of fluorescence in the red channel coincides with LAMP1 staining (green in the merged images in e, f) as shown in yellow (overlap). The calibration bar in f represents 40 µm in a, 6 µm in b and 10 µm in c–f

Figure 1b–e shows the images of SDS-PAGE gels which represent the stages of synthesis [Fig. 1b, crude product, lane 1 and lane 2 (reduced) compared to mAb2C4 alone] and the purified mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6] (Fig. 1c), following chromatography on nickel-NTA column and the peptide affinity column. Figure 1d shows the profile of purified mAb2C4:gelonin following chromatography on the peptide affinity and HiTrap Blue HP columns, and in Fig. 1e, purified mAb2C4:MMAE following chromatography on a peptide affinity column and HiTrap Phenyl HP. Further details of the purifications of mAb2C4:dianthin, mAb2C4:gelonin and mAb2C4:MMAE can be found in supplementary Figs. 1, 2 and 3.

The comparative potency of immunotoxin versus ADC in HGG cell line SB2b and cell line U87MG

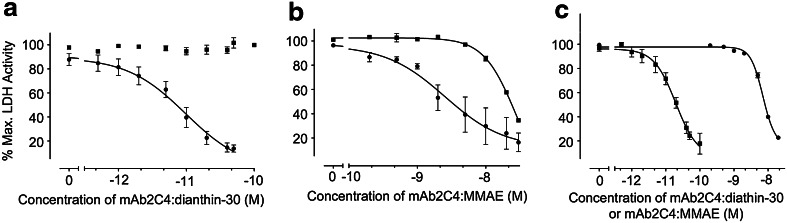

Figure 2a, using the HGG cell line SB2b, shows the graphical displays from the results of multiple experiments with mAb2C4:dianthin (n = 4) with and without SO1861, compared to mAb2C4:MMAE (n = 4) (Fig. 2b with and without SO1861). With SO1861 the negative logarithm of the half maximal effective concentration (pEC50) for mAb2C4:dianthin was calculated, using a three-parameter logistic equation as −11.0 ± 0.14 (EC50, 10.0 pM) and for mAb2C4:MMAE as −8.6 ± 0.20 (EC50, 2.5 nM), which is approximately 250-fold less potent (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

a The comparative toxicity profiles of the immunotoxin mAb2C4:dianthin-30 with (filled circle, 3 µg/mL, n = 4) and without (filled square) SO1861 (n = 4), and b the ADC, mAb2C4:MMAE with (filled circle, n = 3) and without (filled square, n = 4) SO1861 in the HGG cell line SB2b. c The comparative toxicity profiles of the immunotoxin mAb2C4:dianthin-30 (filled square, n = 3) and the ADC, mAb2C4:MMAE (filled circle, n = 3) in the cell line U87MG with 1 µg/mL SO1861. In any one 96-well experiment to measure lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity, each data point represents the nett LDH activity in which the nett LDH is calculated from the difference between the mean total LDH (three lysed cell samples) minus mean residual LDH (three unlysed cell samples). Each experiment was repeated n = 3 or n = 4 as indicated above. Values were normalised against the mean of LDH activity in untreated cells that results in % maximal LDH activity. The EC50 values are listed in Table 1

Table 1.

EC50 values derived from Fig. 2 are listed with different cell lines using immunotoxins mAb2C4:dianthin-30[His6], mAb2C4:gelonin and the ADC mAb2C4:MMAE in the LDH release assay as described for Fig. 2

| Cell line | Immunotoxin/ADC | Addition of SO1861 (µg/mL) | Independent experiments (n) | Log EC50 | EC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB2b | mAb2C4:dianthin | Nil | 4 | ND | ND* |

| mAb2C4:dianthin | 3 | 4 | −11.0 ± 0.14 | 10.0 pM | |

| mAb2C4:MMAE | Nil | 4 | −7.6 ± 0.23 | 25.1 nM | |

| mAb2C4:MMAE | 3 | 3 | −8.6 ± 0.20 | 2.5 nM | |

| U87MG | mAb2C4:dianthin | 1 | 3 | −10.7 ± 0.11 | 20.0 pM |

| mAb2C4:MMAE | 1 | 3 | −8.2 ± 0.02 | 6.3 nM | |

| mAb2C4:gelonin | 1 | 3 | −10.7 ± 0.1 | 20 pM | |

| JK2 | mAb2C4:dianthin | 3 | 4 | −11.0 ± 0.33 | 10.0 pM |

Each determination represents data from n independent experiments. Also included are data derived from supplementary Fig. 4

ND no curve could be determined from data over the tested range 1–100 pM, ND* the EC50 could be estimated from supplementary Fig. 6 as approximately 10–20 nM

In the HGG cell line SB2b, SO1861 increased the potency of mAb2C4:dianthin-30 by 3 log values (from supplementary Fig. 7) and mAb2C4:MMAE by 1 log value (Fig. 2b). With the HGG cell line JK2 treated with mAb2C4:dianthin and SO1861 (supplementary Fig. 5), the EC50 was 10.0 pM (Table 1), similar to the value calculated for SB2b.

We tested the biological activity of mAb2C4:dianthin-30 and mAb2C4:MMAE in the cell line U87MG as a reference cell line for comparison with other studies reported in the literature. In the presence of SO1861 (Fig. 2c), the EC50 was 20.0 pM and 6.3 nM (Table 1), respectively, which is 300-fold less potent. The EC50 for mAb2C4:gelonin was similar to that for mAb2C4:dianthin-30, namely 20 pM (Table 1).

The potency of each immunotoxin versus ADC in a range of GBM cell lines

The EC50 values in several high-grade glioma cell lines are listed in supplementary Table 1 after one experimental determination. The values for mAb2C4:dianthin-30 in the presence of SO1861 are close to 10 pM for SB2b, JK2, GBM-4 and GBM-L2, approximately 50 pM for WK1, but PB1 is quite resistant to both mAb2C4:dianthin-30 and mAb2C4:gelonin (supplementary Figs. 6, 7; supplementary Table 1).

The uptake of mAb2C4:AF568 into HGG cell lines and U87MG

Figure 3 shows the images of the uptake of mAb2C4:AF568 by cell lines JK2 [low (20×) magnification], and at higher (63×) magnification, SB2b, PB1 and U87MG. Fluorescence associated with mAb2C4:AF568 is present on the cell membranes as well as concentrated in the perinuclear region. Some of the latter fluorescence coincides with LAMP1 staining (green in Fig. 3d, f) as shown in yellow (overlap), although the extent of LAMP1 positivity varies considerably between the cell lines. LAMP1 is commonly used to identify the late endosomal/lysosomal compartments.

Of note, PB1, which is relatively resistant to mAb2C4:dianthin-30, showed uptake of mAb2C4:AF568 following live staining for 1 h.

Triterpene glycoside SO1861 promotes the release of dianthin into the cytosol

The release of toxin with enhancer SO1861 from intracellular compartments was tested by pre-loading the U87MG cells with Alexa Fluor 488-labelled dianthin (dianthin:AF488) prior to real-time imaging. In Fig. 4a–d, U87MG cells were incubated with the nuclear stain Hoechst 33342 (Fig. 4a), pHrodo™ Red Dextran (Fig. 4b), which is a marker for endosomes and lysosomes, and dianthin:AF488 (Fig. 4c; merged image Fig. 4d). Dianthin:AF488 was detected in intracellular vesicles (Fig. 4c) and co-localisation with pHrodo™ Red Dextran was observed (white arrows), indicating that dianthin:AF488 was transported into endosomes/lysosomes.

Fig. 4.

Intracellular localisation of dianthin:AF488 and release into the cytosol in the presence of SO1861. a U87MG cells were stained with the membrane-permeable dye Hoechst 33342 (blue nuclei), b pHrodo™ Red Dextran (red), c dianthin:AF488 (green); d merged image. Co-localization with pHrodo™ Red Dextran and dianthin-30:AF488 was partly observed (white arrows), indicating accumulation in endosomes/lysosomes. e The increase in the fluorescence intensity with the release of dianthin:AF488 into the cytosol in cell 1 (green trace) and cell 2 (blue trace). Regions of interest were defined for affected cells and the SO1861-mediated intracellular release of dianthin:AF488 was analysed off-line by Carl Zeiss ZEN 2.3 lite software. The sudden increase of the intensity indicates the release of dianthin:AF488 into the cytosol. f–i Images taken from the supplementary video show the time series of SO1861-mediated intracellular release of dianthin:AF488 from two cells in a field, in which merged images at different time points are shown, of U87MG cells loaded with dianthin:AF488. f t = 36 s; 5 µg/mL SO1861 was added. g t = 136 s; no change. h t = 180 s; high-intensity green fluorescence is evident in cell 1, which indicates the SO1861-mediated intracellular release of dianthin:AF488 into the cytosol. At 500 s, the leakage of dianthin:AF488 into the supernatant was restricted by the plasma membrane and is approximately 25% over 5 min (green trace). i t = 504 s, high-intensity green fluorescence is evident in cell 2, which indicates the SO1861-mediated intracellular release of dianthin:AF488 into the cytosol. The calibration bar in a represents 20 µm

In further real-time experiments, SO1861 was added to the cells to investigate the SO1861-mediated intracellular release of dianthin:AF488 into the cytosol. This is quantified in Fig. 4e. The complete video sequence can be found in the supplementary video. The cytosolic fluorescence indicates the release of dianthin:AF488 from intracellular compartments, a process that is mediated by SO1861. Figure 4f–i show images taken from the supplementary video 1: panel (f) at 36 s when 5 µg/mL SO1861 was added, panel (g) at 136 s (no change), panel (h) at 180 s when dainthin:AF488 was released into the cytosol of cell 1 and panel (i) at 500 s when dainthin:AF488 was released into the cytosol of cell 2.

Discussion

CTR was found to be expressed in a high percentage of human biopsies of glioblastoma [25] and, as reported here, by approximately 50% of HGG cell lines that were available to us. These cell lines are considered to represent glioma stem cells. In view of their role in the rapid expansion of the tumour and the relative resistance glioma stem cells confer to conventional therapies, we chose to target CTR and compare the efficacies of antibody:conjugates representing two immunotoxins and an ADC. Part of the reasoning was the current popularity of ADCs being tested in clinical trials and our own interest in the potency of enhancers to improve the efficacy of RIP-based immunotoxins. Thus, the question we addressed concerned the comparison of the efficacies of immunotoxins and a related ADC tested on HGG cell lines in vitro.

The opportunity for this study began with our identification of the expression of CTR in glioblastoma and the validation of the antibody mAb2C4 which specifically binds an extracellular epitope of hCTR [24].

The first step was the synthesis of immunotoxins from mAb2C4 and the RIPs, dianthin-30 [43] and gelonin [44], and the drug MMAE [38] with a linker, together known as vedotin. A range of protein (antibody or toxin) and cross-linker SPDP molar ratios were tested and the optimal 1:6 for both were conjugated and further purified as described. One important step in the purification for each synthesis employed chromatography using a peptide affinity column which selected moieties that were capable of specifically binding the target sequence of hCTR located in the extracellular N-terminal domain and excluded modified antibody conjugates that no longer retained affinity for CTR.

Following the purification steps, we determined with statistical accuracy the efficacy of treatment with mAb2C4:dianthin compared to mAb2C4:MMAE, which involved 96-well assays to determine nett LDH and these were repeated four times (data shown in Fig. 2a–c). With the HGG cell line SB2b, in the presence of SO1861, the EC50 for mAb2C4:dianthin is 10.0 pM and for mAb2C4:MMAE 2.5 nM, which is approximately 250-fold less potent. Similarly with the cell line U87MG, in the presence of SO1861, the EC50 for mAb2C4:dianthin is 20.0 pM and for mAb2C4:MMAE 6.3 nM, which is approximately 300-fold less potent.

To further explore the underlying biological variation that might be expected between patients, we pooled the data for all HGG cell lines tested (data not shown) and U87MG treated with either mAb2C4:dianthin or mAb2C4:gelonin (EC50 for both, 8 pM), but excluded the data derived with the HGG cell line PB1, which was resistant to both the immunotoxins. A comparison with the pooled for the ADC (EC50, 10 nM) demonstrated the immunotoxins were greater than 3 logs more potent. These pooled data demonstrate a remarkably similar sensitivity to both immunotoxins in a range of HGG cell lines. This observation adds weight to the claim that CTR is a potential target for the treatment of glioblastoma, as a high proportion of lines that express CTR were sensitive to the immunotoxins and were isolated from individual biopsies.

MAb2C4:MMAE was consistently less potent, with EC50 in the nM range for both SB2b and U87MG, which is 250–300 times less potent than mAb2C4:dianthin-30 and mAb2C4:gelonin in the presence of SO1861. Controls with unconjugated antibody (in the higher nM range) showed little effect on cell death. In the absence of SO1861, mAb2C4:MMAE is tenfold less potent and mAb2C4:RIPs were relatively ineffective (1000-fold less potent), such that their potencies are similar at approximately 10–20 nM (Table 1; supplementary Fig. 6). These data demonstrate that the enhancer SO1861 has a high degree of specificity for the RIP. The EC50 data for these cell lines with mAb2C4:RIPs as described above is consistent with data published recently for cetuximab:dianthin-30 (5.3 pM), panitumumab:dianthin-30 (1.5 pM) and trastuzumab:dianthin-30 (23 pM) co-administered with SO1861 [43].

The HGG cell line PB1 was resistant to mAb2C4:RIPs, although it expressed CTR as determined by immunoblot (Fig. 1a) and accumulated mAb2C4:AF568 (Fig. 3). This demonstration of resistance by PB1 alone compared to other cell lines supports a mechanism in which uptake of immunotoxin is receptor mediated, rather than being some non-specific mechanism of internalisation. The possible explanations for resistance in this cell line include that CTR is not efficiently internalised to reach the lysosomal compartment or the immunotoxin is not cleaved in the lysosomal compartment or that the RIP is not released into the cytosol. We note the significant difference in the intracellular distribution of mAb2C4:AF568 in PB1 compared with SB2b and U87MG. The large concentration of antibody suggests stalling and localisation in a perinuclear structure, perhaps the microtubule organising centre, with little access to the lysosomal compartment.

Seck et al. [47] originally proposed that CTR was embedded in the endosomal membrane and that this structure was bound to the cytoskeleton through the intermediate filament filamin. We have extended this idea [24] in which carboxyl terminal arginines, together with a PDZ docking site, are identified in CTR from all species and are predicted to be important sites of binding to tubulin. We proposed that the mechanism of uptake of mAb2C4 conjugates was driven by receptor-mediated endocytosis with endosomes trafficked along the microtubules driven by molecular motors as reviewed [48]. When immunotoxins are transported by these endosomes, which subsequently become transformed into lysosomes (at low pH), the enhancers induce the release of cleaved RIPs as illustrated in Fig. 4 and supplementary video 1. During this release, the RIP does not breach the plasma membrane in significant amounts, but remains concentrated within the cytosol, consistent with the actions of enhancers in the release of RIP into the cytosol.

The relatively recent description of the powerful additional effects of enhancers and prior inefficient escape of RIPs from intracellular compartments in their absence might be a major reason why plant immunotoxins have not yet achieved acceptance for clinical studies. With successful animal studies this situation is likely to change.

Recent unpublished studies in mice by our group have investigated the toxicity of mAb2C4:dianthin with SO1861. The mice tolerate the highest serum concentration tested, namely 300 pM immunotoxin, with no apparent effects on health (unpublished results). Given the EC50 in vitro is approximately 10 pM, this provides a potential therapeutic window. From these observations of tolerance, it seems that CTR-neural circuits, the expression in distal tubules, thyroid and elsewhere, may escape exposure to the immunotoxin. Any depleted population, perhaps osteoclasts, might be replenished from bone marrow progenitors. These results are also consistent with the lack of significant penetration of the vasculature in which endothelial cells are CTR negative and supports the view that the uptake of this immunotoxin into cells is a receptor-mediated process.

As far as we are aware, this is the first published study in which an anti-G-protein coupled receptor antibody has been employed to target cancer stem cells. In view of the expression of CTR by a range of tumour types, it seems likely that this technology could be included in strategies for the treatment of other cancers (or subtypes) including breast, bone, prostate cancers and others (see “Introduction”). We ask the question: Is there a link between expression of CTR in cancer stem cells and expression in the pre-apoptotic cell stress response as proposed elsewhere [24]? In other words, do some cancer cells exist in a state equivalent to the pre-apoptotic cell stress response?

In clinical trials, immunogenicity associated with RIPs has been overcome with T cell epitope depletion, for instance in the case of deBouganin [49]. When combined with improved potency afforded with triterpene glycosides, this is likely to create a powerful and effective combinational therapy for recalcitrant tumours.

In summary we have demonstrated that an anti-CTR antibody conjugated to an RIP can be deployed to target glioma stem cells (HGG cell lines). These cells form the basis for resistance to chemotherapy and expansion of the deadly tumour glioblastoma. The immunotoxins studied here are 250–300 times more potent than an equivalent ADC in a range of HGG cell lines and suggests that more potent, aggressive treatment regimens can be configured than are currently being investigated in clinical trials. This improved efficacy may be important for the successful treatment of recalcitrant tumours such as GBM, and such strategies should be investigated with clinical trials as the next step to improve patient outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Dr Furness was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (Program Grant 1055134 and Project Grant 1061044). Dr Gilabert-Oriol was supported by an Endeavour Research Fellowship (Australian Government). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors are grateful for the gift of rGelonin from Professor Rosenblum of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Texas, USA. Confocal microscopy was performed at the Biological Optical Microscopy Platform, The University of Melbourne (http://www.microscopy.unimelb.edu.au) and the Leibniz-Institut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP), Campus Berlin-Buch, Berlin, Germany. Thanks go to the team at the Antibody Facility (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Bundoora) for production of the anti-CTR antibodies.

Abbreviations

- ADC

Antibody–drug conjugate

- BTIC

Brain tumour initiating cell

- CTR

Calcitonin receptor

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- EDTA

Ethylene diamine tetra acetate

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- FGF

Fibroblast growth factor

- GBM

Glioblastoma multiforme

- hCTR

Human calcitonin receptor

- HGG

High-grade glioma

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MMAE

Monomethyl auristatin E

- NTA

Nitrilotriacetate

- RIP

Ribosome-inactivating protein

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Dr Wookey is a Director of Welcome Receptor Antibodies Pty Ltd (Australia) which developed the anti-CTR antibodies. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Roger Gilabert-Oriol and Sebastian G. B. Furness contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, Scheithauer BW, Kleihues P. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, Cipelletti B, Gritti A, De Vitis S, Fiocco R, Foroni C, Dimeco F, Vescovi A. Isolation and characterization of tumorigenic, stem-like neural precursors from human glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fomchenko EI, Holland EC. Stem cells and brain cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das S, Marsden PA. Angiogenesis in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1561–1563. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1309402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behin A, Hoang-Xuan K, Carpentier AF, Delattre JY. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2003;361:323–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamilton GS. Antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy: the technological and regulatory challenges of developing drug-biologic hybrids. Biologicals. 2015;43:318–332. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Goeij BE, Lambert JM. New developments for antibody–drug conjugate-based therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;40:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ledford H. Weaponized antibodies use new tricks to fight cancer. Nature. 2016;540:19–20. doi: 10.1038/540019a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reardon DA, Lassman AB, van den Bent M, Kumthekar P, Merrell R, Scott AM, Fichtel L, Sulman EP, Gomez E, Fischer J, Lee HJ, Munasinghe W, Xiong H, Mandich H, Roberts-Rapp L, Ansell P, Holen KD, Gan HK. Efficacy and safety results of ABT-414 in combination with radiation and temozolomide in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fermani S, Falini G, Ripamonti A, Bolognesi A, Polito L, Stirpe F. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of two ribosome-inactivating proteins: lychnin and dianthin 30. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1227–1229. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903010680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosur MV, Nair B, Satyamurthy P, Misquith S, Surolia A, Kannan KK. X-ray structure of gelonin at 1.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:368–380. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Mallinckrodt B, Thakur M, Weng A, Gilabert-Oriol R, Durkop H, Brenner W, Lukas M, Beindorff N, Melzig MF, Fuchs H. Dianthin-EGF is an effective tumor targeted toxin in combination with saponins in a xenograft model for colon carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2014;10:2161–2175. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thakur M, Mergel K, Weng A, von Mallinckrodt B, Gilabert-Oriol R, Durkop H, Melzig MF, Fuchs H. Targeted tumor therapy by epidermal growth factor appended toxin and purified saponin: an evaluation of toxicity and therapeutic potential in syngeneic tumor bearing mice. Mol Oncol. 2013;7:475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng A, Manunta MD, Thakur M, Gilabert-Oriol R, Tagalakis AD, Eddaoudi A, Munye MM, Vink CA, Wiesner B, Eichhorst J, Melzig MF, Hart SL. Improved intracellular delivery of peptide- and lipid-nanoplexes by natural glycosides. J Control Release. 2015;206:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furness SG, Liang YL, Nowell CJ, Halls ML, Wookey PJ, Dal Maso E, Inoue A, Christopoulos A, Wootten D, Sexton PM. Ligand-dependent modulation of g protein conformation alters drug efficacy. Cell. 2016;167(739–749):e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wookey P, Zulli A, Lo C, Hare D, Schwarer A, Darby I, Leung A. Calcitonin receptor (CTR) expression in embryonic, foetal and adult tissues: developmental and pathophysiological implications. In: Hay D, Dickerson I, editors. The calcitonin gene-related peptide family; form, function and future perspectives. The Netherlands: Springer; 2010. pp. 199–233. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wookey PJ, Turner K, Furness JB. Transient expression of the calcitonin receptor by enteric neurons of the embryonic and early post-natal mouse. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:311–317. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marx SJ, Aurbach GD, Gavin JR, 3rd, Buell DW. Calcitonin receptors on cultured human lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:6812–6816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Body JJ, Glibert F, Nejai S, Fernandez G, Van Langendonck A, Borkowski A. Calcitonin receptors on circulating normal human lymphocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:675–681. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-3-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jagger C, Chambers T, Pondel M. Transgenic mice reveal novel sites of calcitonin receptor gene expression during development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274:124–129. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tikellis C, Xuereb L, Casley D, Brasier G, Cooper ME, Wookey PJ. Calcitonin receptor isoforms expressed in the developing rat kidney. Kidney Int. 2003;63:416–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tolcos M, Tikellis C, Rees S, Cooper M, Wookey P. Ontogeny of calcitonin receptor mRNA and protein in the developing central nervous system of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2003;456:29–38. doi: 10.1002/cne.10478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furness SGB, Hare DL, Kourakis A, Turnley AM, Wookey PJ. A novel ligand of calcitonin receptor reveals a potential new sensor that modulates programmed cell death. Cell Death Discov. 2016;2:16062. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wookey PJ, McLean CA, Hwang P, Furness SG, Nguyen S, Kourakis A, Hare DL, Rosenfeld JV. The expression of calcitonin receptor detected in malignant cells of the brain tumour glioblastoma multiforme and functional properties in the cell line A172. Histopathology. 2012;60:895–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silvestris F, Cafforio P, De Matteo M, Quatraro C, Dammacco F. Expression and function of the calcitonin receptor by myeloma cells in their osteoclast-like activity in vitro. Leuk Res. 2008;32:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkatanarayan A, Raulji P, Norton W, Chakravarti D, Coarfa C, Su X, Sandur SK, Ramirez MS, Lee J, Kingsley CV, Sananikone EF, Rajapakshe K, Naff K, Parker-Thornburg J, Bankson JA, Tsai KY, Gunaratne PH, Flores ER. IAPP-driven metabolic reprogramming induces regression of p53-deficient tumours in vivo. Nature. 2015;517:626–630. doi: 10.1038/nature13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson GC, Horton MA, Sexton PM, D’Santos CS, Moseley JM, Kemp BE, Pringle JA, Martin TJ. Calcitonin receptors of human osteoclastoma. Horm Metab Res. 1987;19:585–589. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1011887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorn AH, Rudolph SM, Flannery MR, Morton CC, Weremowicz S, Wang TZ, Krane SM, Goldring SR. Expression of two human skeletal calcitonin receptor isoforms cloned from a giant cell tumor of bone. The first intracellular domain modulates ligand binding and signal transduction. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2680–2691. doi: 10.1172/JCI117970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillespie M, Thomas R, Pu Z, Zhou H, Martin T, Findlay D. Calcitonin receptors, bone sialoprotein and osteopontin are expressed in primary breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:812–815. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971210)73:6<812::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu G, Burzon D, di Sant’Agnese P, Schoen S, Deftos L, Gershagen S, Cockett A. Calcitonin receptor mRNA expression in human prostate. Urology. 1996;47:376–381. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas S, Muralidharan A, Shah GV. Knock-down of calcitonin receptor expression induces apoptosis and growth arrest of prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:1425–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frendo JL, Delage-Mourroux R, Cohen R, Pichaud F, Pidoux E, Guliana JM, Jullienne A. Calcitonin receptor mRNA is expressed in human medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 1998;8:141–147. doi: 10.1089/thy.1998.8.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott AM, Wolchok JD, Old LJ. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:278–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Miller CR, Ding L, Golub T, Mesirov JP, Alexe G, Lawrence M, O’Kelly M, Tamayo P, Weir BA, Gabriel S, Winckler W, Gupta S, Jakkula L, Feiler HS, Hodgson JG, James CD, Sarkaria JN, Brennan C, Kahn A, Spellman PT, Wilson RK, Speed TP, Gray JW, Meyerson M, Getz G, Perou CM, Hayes DN, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Day BW, Stringer BW, Al-Ejeh F, Ting MJ, Wilson J, Ensbey KS, Jamieson PR, Bruce ZC, Lim YC, Offenhauser C, Charmsaz S, Cooper LT, Ellacott JK, Harding A, Leveque L, Inglis P, Allan S, Walker DG, Lackmann M, Osborne G, Khanna KK, Reynolds BA, Lickliter JD, Boyd AW. EphA3 maintains tumorigenicity and is a therapeutic target in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pollard SM, Yoshikawa K, Clarke ID, Danovi D, Stricker S, Russell R, Bayani J, Head R, Lee M, Bernstein M, Squire JA, Smith A, Dirks P. Glioma stem cell lines expanded in adherent culture have tumor-specific phenotypes and are suitable for chemical and genetic screens. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Francisco JA, Cerveny CG, Meyer DL, Mixan BJ, Klussman K, Chace DF, Rejniak SX, Gordon KA, DeBlanc R, Toki BE, Law CL, Doronina SO, Siegall CB, Senter PD, Wahl AF. cAC10-vcMMAE, an anti-CD30-monomethyl auristatin E conjugate with potent and selective antitumor activity. Blood. 2003;102:1458–1465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grundy TJ, De Leon E, Griffin KR, Stringer BW, Day BW, Fabry B, Cooper-White J, O’Neill GM. Differential response of patient-derived primary glioblastoma cells to environmental stiffness. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23353. doi: 10.1038/srep23353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tivnan A, Zhao J, Johns TG, Day BW, Stringer BW, Boyd AW, Tiwari S, Giles KM, Teo C, McDonald KL. The tumor suppressor microRNA, miR-124a, is regulated by epigenetic silencing and by the transcriptional factor, REST in glioblastoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:1459–1465. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosein AN, Lim YC, Day B, Stringer B, Rose S, Head R, Cosgrove L, Sminia P, Fay M, Martin JH. The effect of valproic acid in combination with irradiation and temozolomide on primary human glioblastoma cells. J Neuro Oncol. 2015;122:263–271. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1713-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dickinson A, Yeung KY, Donoghue J, Baker MJ, Kelly RD, McKenzie M, Johns TG, St John JC. The regulation of mitochondrial DNA copy number in glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1644–1653. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilabert-Oriol R, Weng A, Trautner A, Weise C, Schmid D, Bhargava C, Niesler N, Wookey PJ, Fuchs H, Thakur M. Combinatorial approach to increase efficacy of Cetuximab, Panitumumab and Trastuzumab by dianthin conjugation and co-application of SO1861. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;97:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenblum MG, Kohr WA, Beattie KL, Beattie WG, Marks W, Toman PD, Cheung L. Amino acid sequence analysis, gene construction, cloning, and expression of gelonin, a toxin derived from Gelonium multiflorum. J Interf Cytokine Res. 1995;15:547–555. doi: 10.1089/jir.1995.15.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cumber AJ, Henry RV, Parnell GD, Wawrzynczak EJ. Purification of immunotoxins containing the ribosome-inactivating proteins gelonin and momordin using high performance liquid immunoaffinity chromatography compared with blue sepharose CL-6B affinity chromatography. J Immunol Methods. 1990;135:15–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90251-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weng A, Thakur M, von Mallinckrodt B, Beceren-Braun F, Gilabert-Oriol R, Wiesner B, Eichhorst J, Böttger S, Melzig MF, Fuch H. Saponins modulate the intracellular trafficking of protein toxins. J Control Release. 2012;164:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seck T, Baron R, Horne WC. Binding of filamin to the C-terminal tail of the calcitonin receptor controls recycling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10408–10416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ross JL, Ali MY, Warshaw DM. Cargo transport: molecular motors navigate a complex cytoskeleton. Curr Op Cell Biol. 2008;20:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cizeau J, Grenkow DM, Brown JG, Entwistle J, MacDonald GC. Engineering and biological characterization of VB6-845, an anti-EpCAM immunotoxin containing a T-cell epitope-depleted variant of the plant toxin bouganin. J Immunother. 2009;32:574–584. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a6981c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.