Abstract

Imatinib (IM) has been described to modulate the function of dendritic cells and T lymphocytes and to affect the expression of antigen in CML cells. In our study, we investigated the effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors IM and nilotinib (NI) on antigen presentation and processing by analyzing the proteasomal activity in CML cell lines and patient samples. We used a biotinylated active site-directed probe, which covalently binds to the proteasomally active beta-subunits in an activity-dependent fashion. Additionally, we analyzed the cleavage and processing of HLA-A3/11- and HLA-B8-binding peptides derived from BCR-ABL by IM- or NI-treated isolated 20S immunoproteasomes using mass spectrometry. We found that IM treatment leads to a reduction in MHC-class I expression which is in line with the inhibition of proteasomal activity. This process is independent of BCR-ABL or apoptosis induction. In vitro digestion experiments using purified proteasomes showed that generation of epitope-precursor peptides was significantly altered in the presence of NI and IM. Treatment of the immunoproteasome with these compounds resulted in an almost complete reduction in the generation of long precursor peptides for the HLA-A3/A11 and −B8 epitopes while processing of the short peptide sequences increased. Treatment of isolated 20S proteasomes with serine-/threonine- and tyrosine-specific phosphatases induced a significant downregulation of the proteasomal activity further indicating that phosphorylation of the proteasome regulates its function and antigen processing. Our results demonstrate that IM and NI can affect the immunogenicity of malignant cells by modulating proteasomal degradation and the repertoire of processed T cell epitopes.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukemia, Proteasome, Imatinib, Nilotinib, Antigen processing

Introduction

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is a myeloproliferative disease characterized by the Philadelphia chromosome, which results from an acquired reciprocal translocation of the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22 t(9;22)(q34;q11). This translocation fuses the chimeric BCR-ABL oncogene, which is translated into a 210-kDa chimeric protein that exhibits constitutive tyrosine kinase activity [1]. Currently, the mechanisms of malignant transformation are not completely resolved; however, the BCR-ABL translocation is believed to be the causative event in CML development [2].

IM, a BCR-ABL-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) which leads to a significant prolongation of hematologic and cytogenetic remissions without evoking strong major adverse effects, was introduced as first-line treatment for CML patients [3–7] some years ago.

Nevertheless, the development of novel BCR-ABL mutations is a widespread problem resulting in resistance to the drug. In most cases, point mutations or an amplification of the BCR-ABL gene was shown to be responsible for TKI resistance, although BCR-ABL-independent mechanisms were also found to evolve during TKI treatment. A variety of second-generation TKIs such as NI and Dasatinib circumvent most of the mutations resistant to IM; however, as an example, the multiresistant T315I-mutation presents an as yet unsolved problem in the treatment of CML [8, 9]. Furthermore, while being highly effective, these drugs do not cure the patients and stopping the treatment leads to relapse in most cases.

In several in vitro and animal models, IM treatment was previously shown to inhibit the function of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), T cells and NK cells [10]. Appel et al. demonstrated in vitro that IM treatment of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (mDCs) leads to downregulation of CD1a, costimulatory molecules and HLA-class I and II molecules. In addition, it could be demonstrated that IM inhibits the differentiation of DCs from peripheral blood progenitor cells and monocytes [11, 12]. Another important finding was that IM-treated mDCs failed to elicit antigen-specific CTL responses in vitro [13]. Furthermore, IM is capable of affecting the immunogenicity of CML cells by downregulation of tumor-associated antigens [14]. In addition, NK cells as well as T cells might be affected by this compound. As reported by Salih et al. [15] among others, IM and NI attenuated the expression of ligands for the immunoreceptor NKG2D which resulted in reduced NK cell cytotoxicity and IFNγ production. On the other hand, treatment with IM inhibits proliferation of activated T cells and T cell receptor-mediated T cell expansion [16], but do not induce apoptosis as shown in in vitro and in in vivo mouse models [17].

Therefore, other strategies such as immunotherapeutical approaches, using mostly dendritic cell-based vaccination, have been analyzed in clinical trials [18, 19]. These studies usually target epitopes deduced from the BCR-ABL protein. Several recent reports demonstrated that the currently utilized TKIs have a significant impact on function and differentiation of nonmalignant hematopoietic cells such as antigen-presenting cells or T lymphocytes [11, 12]. Thus, therapeutic approaches using these compounds seem to interfere with the immune system on several levels and modulate its function.

In the present study, we investigated the possible effects of IM and NI on antigen processing and presentation by analyzing the proteasomal activity of CML cells treated with these drugs.

The proteasome consists of a 20S core containing the catalytically active beta-subunits, and two 19S cap complexes. Both together build the 26S proteasome. The 20S proteasome harbors three different proteolytically active sites, the N-terminal threonine residues of the subunits β1, β2 and β5. In this study, proteasomal activity was assessed using an activity-based probe Biotin-Ahx3L3VS (BioALVS) that binds to the threonine residues of the active β-subunits in the 20S proteasome. By dint of the biotin moiety of the probe, the degree of active site labeling and, therefore, the proteasomal activity can be detected by Western blot analysis. In addition, the cleavage and processing of antigenic BCR-ABL-derived peptides was analyzed after degradation by the isolated 20S immunoproteasome under the influence of IM or NI by mass spectrometry.

In our experiments, we were able to show for the first time that treatment with IM leads to a significant downregulation of proteasomal activity in both cell lines and primary patient samples and that it modulates the repertoire of the processed antigenic peptides. Additionally, we found that these immunomodulatory effects of IM and NI on proteasome activity were independent of BCR-ABL.

Materials and methods

Tumor cell lines

The tumor cell line K-562 (CML in blast crisis; American Type Culture Collection), the HLA-A*02:01-transfected cell line K-562-A2 and the acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line NB-4 (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH) were cultured in RP10 medium (RPMI 1640 with glutamax-I, supplemented with 10 % heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, all purchased from Invitrogen). The tumor cell line K-562R [20] (K-562 cell line resistant to low doses of IM, kindly provided by the group of J. Griffin, Dana-Faber Cancer Institute) was grown in RP10 medium supplemented with 0.5 μmol/L IM. All cell lines were characterized regularly, last in May 2012, by PCR or flow cytometry in our institute. As a negative control for BCR-ABL, the BCR-ABL-negative cell line NB-4 was included in several experiments.

Patient samples

Primary leukemia cells were obtained from patients at the Department of Hematology and Oncology, University of Bonn, after written informed consent and approval by the local ethics committee.

Peripheral blood or bone marrow samples from patients with BCR-ABL+ CML were used for the preparation of PBMCs by Ficoll/Paque (Biochrome) density gradient centrifugation as described previously [21, 22].

Reagents

IM and NI were obtained from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland). Sorafenib and sunitinib malate were obtained from Eurasia Chemicals PVT (Mumbai, India).

All TKIs were used in concentrations that are described to correlate with or to be lower than the serum levels of treated patients [23–26]. However, in several experiments, we found that HLA-*A02:01-transfected K-562 cells are more sensitive toward treatment with IM, probably due to previous transfection. Therefore, in experiments with HLA-A2-transfected K-562 cells, we decided to use IM in lower concentrations. LY294002, a specific PI3-kinase inhibitor, was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals and used in the indicated concentrations according to the manufacturers′ data sheet and previous publications.

Additionally, we introduced proteasome inhibitors in our experiments as controls of proteasomal activity. NLVS is an irreversible peptide vinyl sulfone-based proteasome inhibitor [27, 28] that was kindly provided by Christoph Driessen (University of Tübingen) and used in a concentration of 2 mM as published previously by Kessler et al. [29]. NLVS was used as a control in most experiments, with the exception of fluorimetric assays where NLVS could not be utilized due to its pale yellow color. Therefore, NLVS was replaced by the uncolored proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib (Velcade®) in all our fluorimetric assays. Bortezomib was obtained from the pharmacy of the University Hospital of Tübingen and used in a concentration that was previously described [30, 31].

Measurement of apoptosis by flow cytometry

DNA fragmentation in apoptotic nuclei was measured by the method of Nicoletti et al. [32]. First, cells were lysed in hypotonic buffer (1 % sodium citrate, 0.1 % Triton X-100, 50 μg/mL of propidium iodide) to release apoptotic nuclei and subsequently analyzed by flow cytometry on a Cytomics FC 500 (Beckman Coulter) using CXP analysis software. Nuclei to the left of the 2N peak containing hypodiploid DNA were considered as apoptotic.

HLA-class I expression analysis by flow cytometry

HLA-ABC expression was measured by staining K-562-A2-transfected or primary CML cells with FITC-conjugated mouse antibody (anti-HLA-ABC-FITC Clone B9.12.1, Beckman Coulter) raised against MHC-class I. As control, we used FITC-conjugated mouse IgG1 antibody (IgG1-FITC Isotypic Control Clone 679.1Mc7, Beckman Coulter). First, cells were harvested after treatment, washed once in PBS, stained with the antibodies and incubated for at least 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The percentage of HLA-class I-positive cells was measured using flow cytometry on a Cytomics FC 500 (Beckman Coulter) and CXP analysis software.

Active site labeling of active proteasome subunits

Labeling of the active β2- and the β-1/-5 subunits of the proteasome was performed using proteasome-specific affinity probe Biotin-Ahx3L3VS (BioALVS) as described previously [27, 29].

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting

For the preparation of whole-cell lysates, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 0.1× PBS, 5 % Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/mL aprotinin and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The protein concentration of the whole-cell lysates was determined using a BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Perbio Science).

For the protein and proteasome subunits detection, 20 μg of whole-cell lysates were incubated with BioALVS, separated on a 12 % polyacrylamide gel containing SDS and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare). The blots were probed with VectaStain elite Kit (Vector Laboratories) for the detection of the active proteasomal subunits and with antibodies against β2 (mouse monoclonal) and β5 (rabbit polyclonal) (both purchased from Biomol) subunits to detect their expression.

RNA isolation

Total RNA was isolated using an RNAeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturers’ protocol for RNA isolation of animal cells. RNA quantity and purity was measured by UV spectrophotometry. RNA was stored upon use at −80 °C.

RT-PCR

A quantity of 0.5 μg of total RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the Transcription First-Strand cDNA synthesis Kit (Roche) and random primers. A total of 1 μg cDNA was used for PCR analysis. DNA amplifications were performed in a thermocycler (Biometra) with 35 cycles of denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (56–59 °C, 15–30 s depending on primer) and elongation (72 °C, 30 s). As control for RNA integrity and cDNA quality, the actin gene was amplified as control. Primer sequences were deduced from known cDNA sequences: actin fwp 5′–3′ and actin rvp 5′–3′, parts of the MHC-class I heavy chain: HLA fwp 5′-gcggctactacaaccagagc-3′ and HLA rvp 5′-ctccagtgatcacagctcca-3′; β2microglobulin fwp 5′-gggtttcatc-3′ and β2microglobulin rvp 5′-gatgctgcttacatgtctcga-3′, and parts of the antigen-presenting machinery: LMP2 fwp 5′-catcatggcagtggagtttg-3′ and LMP2 rvp 5′-atgctgcatccacataacca-3′; LMP7 fwp 5′-atggagtgattgcagcagtg-3′ and LMP7 rvp 5′-tcacccaaccatcttccttc-3′; TAP1 fwp 5′-gacttgccttgttccgagag-3′and TAP1 rvp 5′-ctgcactggctatggtgaga-3′; TAP2 fwp 5′-aggaggctgcttcacctaca-3′ and TAP2 rvp 5′-cctgtgggctggtacagatt-3′.

Analysis of PCR products was performed using the Qiaxcell (Qiagen) with the corresponding software (BioCalculator®).

Purification of 20S proteasomes

Constitutive and immuno-20S proteasomes were purified as described before from LCL721.174 and LCL721 cells, respectively [33].

In vitro digests of peptides by proteasomes

Two nmol of HPLC purified (>98 %) peptide (NVIVHSATGFKQSSKALQRPVASDFE) was incubated for 2 h with 2 μg of either immunoproteasome or constitutive proteasome in digestion buffer (20 mM HEPES–NaOH; pH 7.6; 2 mM MgAc2; 0.5 mM DTT). The reaction was stopped by adding formic acid to a final concentration of 1 % and freezing the reaction mixture at −80 °C. Before addition of the peptide, proteasomes were preincubated in digestion buffer containing 10 μM of NI or IM for 30 min at 37 °C. Samples were diluted 1:5 before injection into the mass spectrometer.

Analysis of peptide digests by mass spectrometry

Capillary liquid chromatography of the peptide digests was performed with a Waters NanoAcquity UPLC system, equipped with a Waters NanoEase BEH-C18, 100 μm × 10 cm reversed phase column. Mobile phase A contained 0.1 % formic acid in H2O. Mobile phase B contained 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile. Samples (1 μL injection) were loaded onto the column with 3 % mobile phase B. Peptides were eluted from the column with a gradient of 3–60 % mobile phase B over 45 min at 300 nL/min, followed by a 10 min rinse of 90 % of mobile phase B and re-equilibrated at initial conditions for 20 min. Mass spectrometry analysis of peptide fragments was performed using a Waters Q-Tof Premier in positive V-mode equipped with a nano-ESI source after calibration with a fibrinopeptide solution (500 fmol/μL at 300 nL/min) delivered through the reference sprayer of the NanoLockSpray source. For fragment identification and simultaneous relative quantification of the peptide fragments, the instrument was run in MSE-mode [34, 35]. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

Data processing, fragment identification and quantification of LC-MSE data were performed using ProteinLynx Global Server (PLGS) version 2.2. Peptide fragment identification was assigned by searching a database containing the full-length peptide sequences. The mass error tolerance values were typically under 5 ppm.

Application of phosphatases to 20S proteasomes

Isolated and purified 20S proteasomes (Boston Biochem) were incubated with 3 μL of either ser/thr-specific phosphatase PPM1A/PP2Calpha (Biaffin GmbH and CoKG) or 3 μL of tyr-specific phosphatase PTP1B (Jena Bioscience). Additionally, an irrelevant alkaline phosphatase CIP (New England Biolabs), an untreated 20S proteasome sample as well as the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib were used as control. Phosphatase-treated 20S proteasomes were incubated with the substrate SUC-LLVY-AMC (Bachem), and proteolytic cleavage of fluorogenic substrate was measured for 1 h.

Results

Proteasomal activity is reduced upon treatment with imatinib

To analyze the influence of IM on the proteasomal activity in CML cells, we applied an active site labeling of the proteasomal subunits. K-562 cells were treated for 48 h with increasing concentrations of IM (1, 3 and 5 μM). In the first set of experiments, whole-cell lysates from K-562 cells were labeled with the proteasome-specific biotinylated probe BioALVS that binds specifically to the β1/5 and the β2 subunits of the proteasome. As negative control, cells were preincubated with the specific proteasome inhibitor NLVS.

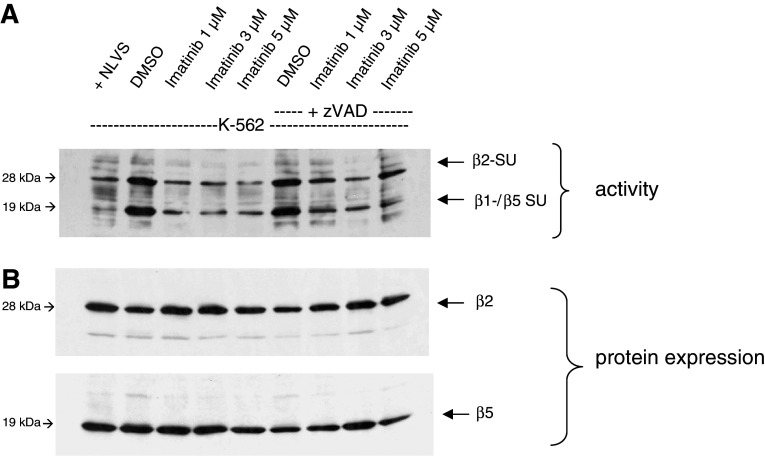

As shown in Fig. 1a, treatment of K-562 cells with different concentrations of IM led to a reduced activity of the proteasomal subunits β1/5 and β2. In contrast, the overall protein expression of these proteasomal subunits was not affected by IM treatment as verified by reprobing the membrane with β2- and β5-specific antibodies.

Fig. 1.

Treatment with IM leads to downregulation of proteasomal activity in K-562 cells. Whole-cell lysates were incubated with Bio-ALVS and separated by a 12 % SDS-PAGE. NLVS, a proteasome inhibitor, was added to one DMSO sample as a control. a Active site labeling of K-562 cells after IM treatment for 48 h with or without addition of 100 μM zVAD-FMK to exclude the influence of apoptosis induction. b Protein expression of the proteasomal subunits β2 and β5

The observed reduction in proteasomal activity was not due to the induction of apoptosis as similar results were obtained when K-562 cells were additionally treated with zVAD-FMK (Fig. 1a). zVAD-FMK is a pan-Caspase inhibitor that blocks Caspase-3 among others, which is responsible for apoptosis induction in the cells. These results indicate that the observed inhibition of the proteasomal activity in K-562 cells by IM was not due to the induction of apoptosis or reduced protein expression.

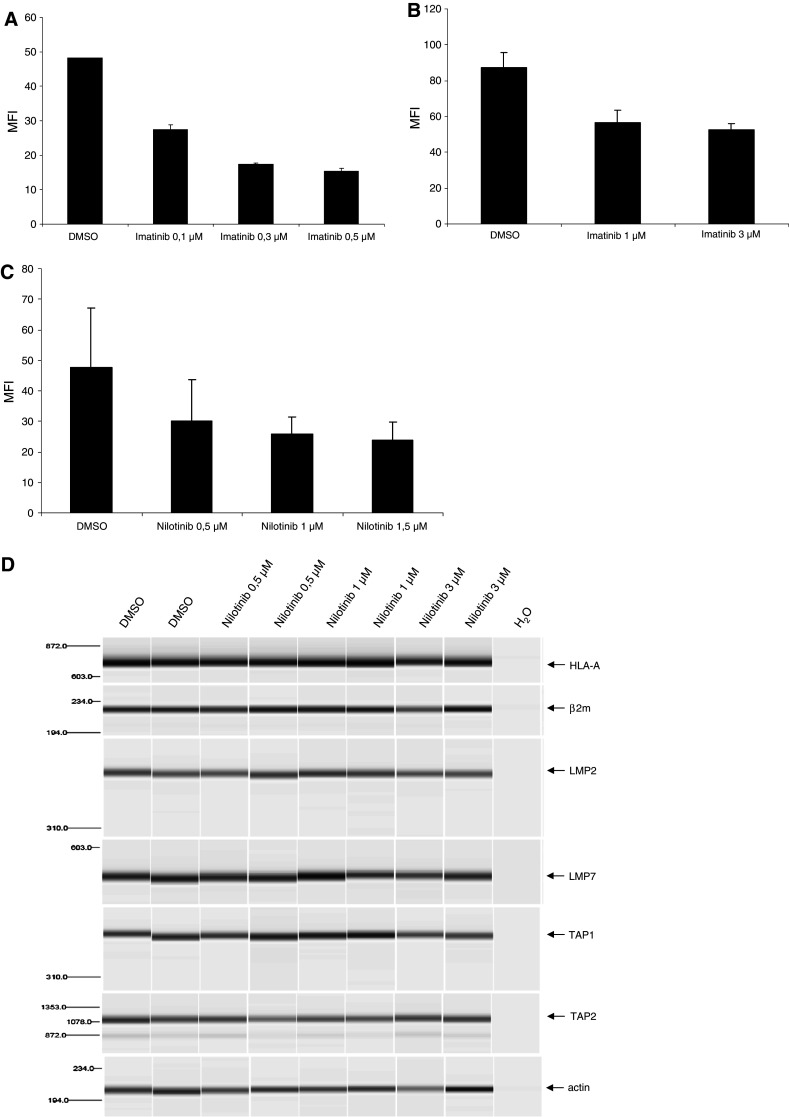

Imatinib and nilotinib reduce the expression of HLA-ABC molecules

Inhibition of proteasomal activity results in reduced generation of peptides that are transported to the endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) and loaded on HLA-class I molecules. Therefore, inhibition of the proteasome should lead to a reduced expression of HLA molecules. To analyze this, we took advantage of HLA-A2-transfected K-562 (K-562-A2) cells as normal K-562 cells express only a few HLA molecules due to a TAP-mutation.

We incubated K-562-A2 cells and primary samples from CML patients with increasing concentrations of IM or NI. HLA-ABC expression on the cell surface was detected using a FITC-conjugated antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2a, treatment of K-562-A2 cells with IM caused a downregulation of HLA-class I molecules on the cell surface. These effects were observed in cells treated with very low concentrations of IM. In order to expand these findings to primary cells, we treated cells from a patient sample with the multiresistant mutation T315I in chronic phase CML with IM (Fig. 2b) and primary cells from a patient without any mutation in chronic phase CML with NI (Fig. 2c). In line with the results of the A2-transfected K-562 cells, treatment of cells with IM and NI reduced the expression of HLA-class I molecules in primary CML cells. Interestingly, this inhibitory effect of the TKIs was detected despite the T315I mutation, suggesting that inhibition of proteasomal activity might be BCR-ABL independent.

Fig. 2.

Treatment of K-562 cells with IM or NI leads to down-regulation of HLA-class I expression. a HLA-A2-transfected K-562 cells were treated with IM. HLA-class I expression was analyzed by flow cytometry using a FITC-conjugated antibody against HLA-ABC. b Primary CML cells extracted from peripheral blood of an untreated CML patient with T315I mutation in chronic phase (CP) were analyzed on HLA-class I expression after incubation with IM. c HLA-class I expression on primary CML cells of a newly diagnosed patient with CP-CML without any mutations after in vitro treatment with NI for 48 h. d RT-PCR analysis of the heavy chain of HLA-A (HLA and β2 m) and parts of the antigen presentation machinery (LMP2, LMP7, TAP1 and TAP2). Actin was used as control for cDNA quality and RNA integrity. Cells were obtained from the patient shown in c that were treated with NI in the indicated concentrations. PCRs were performed using a Qiaxcell analyzer

To further investigate why MHC-class I expression was downregulated after treatment with IM or NI, primary cells of CML patients in chronic phase were treated with either DMSO or TKIs at the indicated concentrations. RT-PCR was performed to analyze these effects of the compounds on molecules involved in the antigen-processing machinery. As shown in Fig. 2d, treatment of primary patient cells with NI had no influence on the mRNA levels of LMP2, LMP7, TAP1, TAP2, HLA-class I and β2-microglobulin.

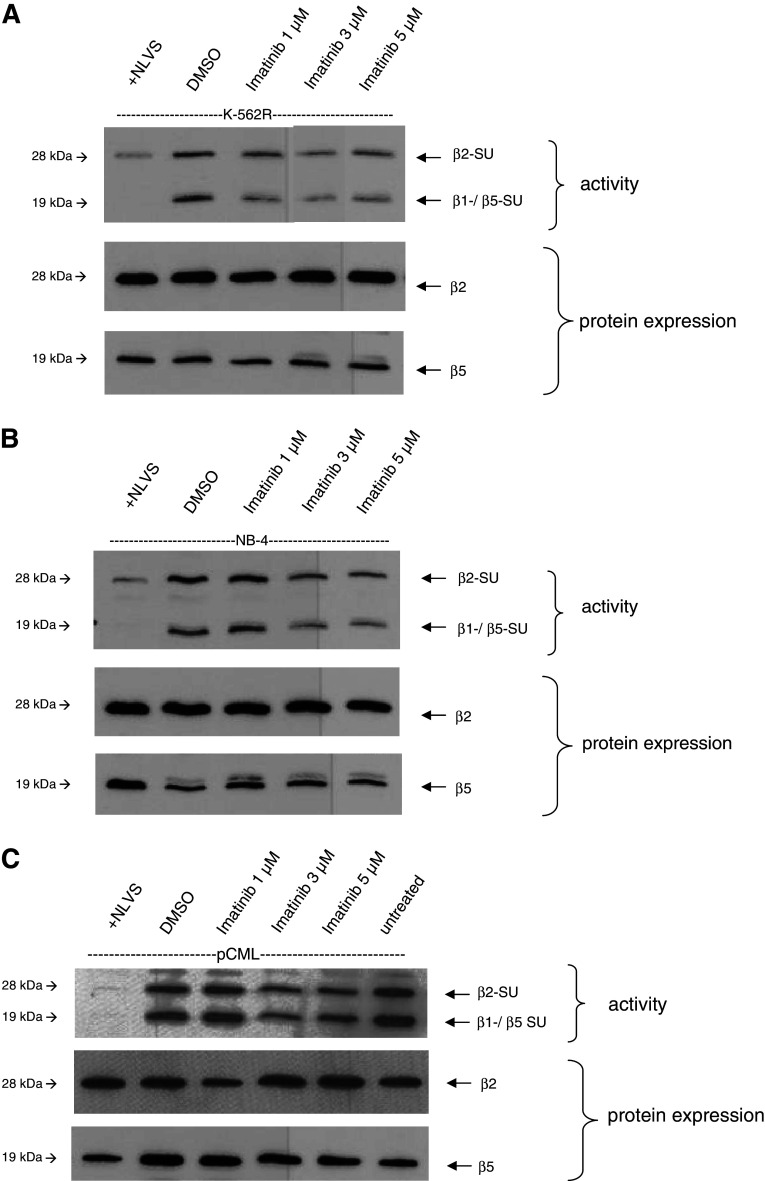

Reduction in proteasomal activity by imatinib is BCR-ABL independent

The previous experiments suggest that the decrease in proteasomal activity after exposure to IM may be BCR-ABL independent. To substantiate this, we first treated IM-resistant K-562R cells with the indicated concentrations of IM for 48 h as described above, and the proteasomal activity in cell lysates was then determined by an active site labeling. As shown in Fig. 3a, proteasomal activity was reduced by IM treatment, which is in line with the results obtained from the IM sensitive cells.

Fig. 3.

The inhibitory effects of IM on proteasomal activity are independent of BCR-ABL. Whole-cell lysates were incubated with Bio-ALVS, separated by SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blot analysis. NLVS served as a control. The single β2- and β5 subunits (SU) act as expression control of the proteasome. a Active site labeling of IM-resistant K-562R treated with increasing concentrations of IM. Incubation of cells with IM resulted in a reduced activity of the β2 and the β1/5 subunits. Protein expression of the subunits is not affected by IM. b Addition of IM to the BCR-ABL-negative cell line NB-4 inhibited the proteasomal activity in treated cells. c Active site labeling of primary CML cells from a patient in blast crisis with IM-resistant mutations Q252H and E255K after treatment with IM. Addition of IM to the cell culture resulted in a decrease in proteasomal activity after IM treatment. The untreated sample was added to exclude possible effects of the in vivo treatment

We next included the BCR-ABL-negative cell line NB-4 in our experiments and were able to detect an inhibition of proteasomal activity in these cells (Fig. 3b). To further confirm these findings, we downregulated BCR-ABL expression in K-562 cells with specific siRNA directed against the fusion site b3a2 (sib3a2_1), as described previously [14], and performed active site labeling. Downregulation of BCR-ABL via siRNA in K-562 cells had no effect on the proteasomal activity (data not shown).

We then repeated these experiments using lysates from a CML patient in blast crisis after IM treatment carrying the IM-resistant mutations Q252H and E255 K. In line with the results from cell lines shown above, we could confirm that IM inhibits the proteasomal activity in primary cells resistant to IM (Fig. 3c). Taken together, these results confirm that the proteasome inhibition by IM is independent of BCR-ABL.

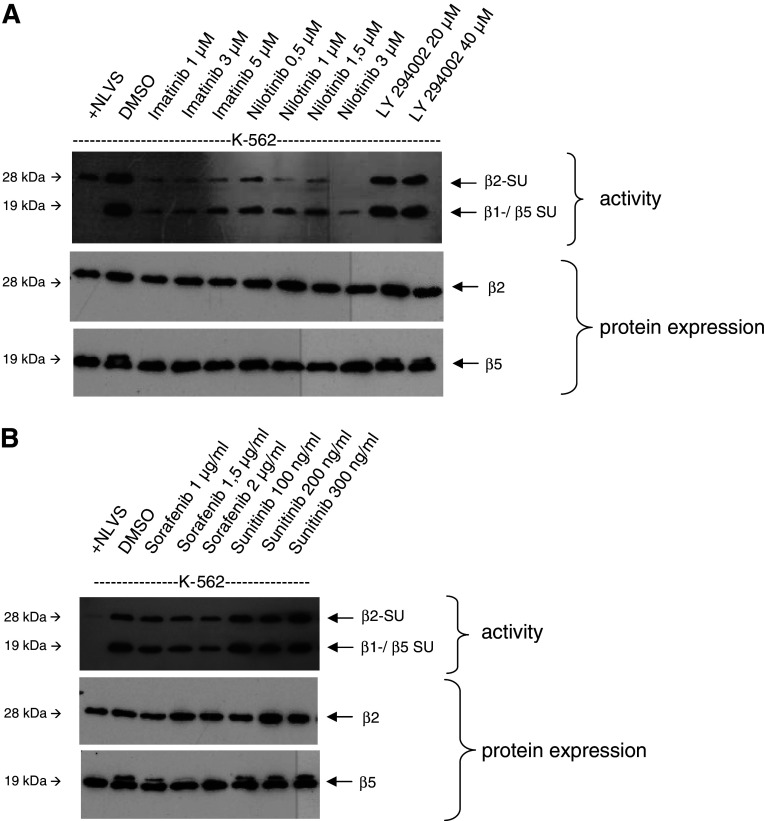

Influence of other tyrosine kinase inhibitors on proteasomal activity

In the next experiment, we examined whether the effect of proteasome inhibition is restricted to IM. Therefore, we repeated the active site labeling using NI, sorafenib and sunitinib, which are both multi-TKIs, as well as LY294002, a PI3-kinase inhibitor, in comparison with IM. Interestingly, we found that in contrast to both IM and NI, sunitinib, sorafenib and LY 294002 had no effect on the proteasomal activity (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

Effects of LY294002, sorafenib and sunitinib on proteasomal activity. Experiments were performed as described above. K-562 cells were treated with PI3K-inhibitor LY294002 (a) or the multi-TKI sorafenib and sunitinib, (b) and the proteasomal activity as well as the protein expression of proteasomal subunits was analyzed as described above

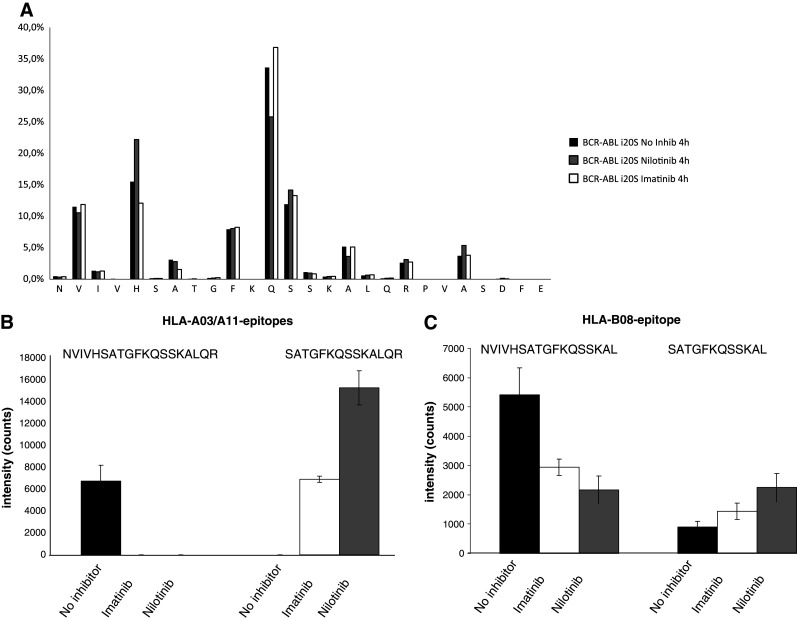

Imatinib and nilotinib modulate the peptide digestion via the i20S proteasome

In the next set of experiments, we analyzed the possible effects of IM and NI on the generation of antigenic peptides after digestion by the 20S immunoproteasome in vitro. To accomplish this, we used isolated 20S immunoproteasomes and pretreated them for 4 h with IM, NI or the solvent as a control. After pretreatment with TKIs, we incubated the i20S proteasomes with the BCR-ABL-derived peptide NVIVHSATGFKQSSKALQRPVASDFE that contains two recently described antigenic HLA-class I-restricted T cell epitopes, KQSSKALQR and GFKQSSKAL, that bind to HLA-A3/11 and HLA-B8, respectively [36]. Both epitopes have been shown to be naturally presented by CML cells [37]. To date, in vitro generation of these epitopes by proteasomal digestion experiments has been shown only for KQSSKLAQR [38]. Here, we show that both epitopes can be generated as N-terminal-elongated precursors in vitro by the immuno-20S proteasome.

In vitro digestion experiments in the presence of NI or IM showed little effect on the observed overall cleavage pattern (Fig. 5a), whereas generation of epitope-precursor peptides was significantly altered in the presence of IM and NI (Fig. 5b, c). Remarkably, while not visible in the overall cleavage pattern, the amounts of epitope precursors differed substantially.

Fig. 5.

In vitro digestion of BCR-ABL peptides by isolated 20S proteasomes. The BCR-ABL-derived peptide (NVIVHSATGFKQSSKALQRPVASDFE) that contains two HLA-class I-restricted antigenic epitopes was incubated for 4 h with the immuno-20S proteasome. The proteasomes were preincubated with either IM, NI or left untreated. Overall cleavage pattern (a) as well as the generation of epitope-precursor peptides for the HLA-*03/*11 (b) and HLA-B*08 (c) epitopes were analyzed by mass spectrometry. Results represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments

IM and NI specifically reduced the production of the long precursor epitopes. In contrast, digestion in the presence of TKIs resulted in a significant increase in the direct HLA-A3/11 and HLA-B8 epitope production by the i20S proteasome.

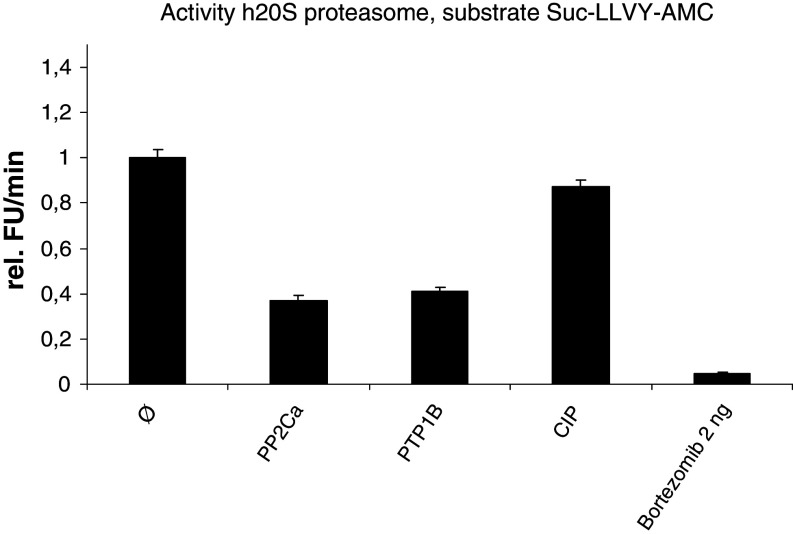

Impact of phosphatases on proteasomal activity

The above results indicate that proteasomal activity might be regulated by phosphorylation that is modulated by TKIs. In order to further analyze these findings, assays with specific phosphatases using isolated 20S proteasomes were performed. We incubated 20S proteasomes with the ser-/thr-specific phosphatase PP2Ca and the tyr-specific phosphatase PTP1B and measured the proteolytic cleavage of the substrate SUC-LLVY-AMC as a kinetic read for 1 h. In line with our previous results from the active site labeling and the peptide digestion, we detected again a strong reduction in the proteasomal activity when the ser-/thr- or the tyr-specific phophatases were utilized. To confirm the measured decrease in proteasomal activity, the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib was used as control. The calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) was included as an irrelevant phosphatase control and had no effect on the activity of the isolated proteasomes (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The modulated proteasomal activity under treatment with NI and IM might be explained by changes in the phosphorylation of proteasomal subunits. Proteasomal activity was analyzed by fluorimetric cleavage of the substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC after treatment of isolated 20S proteasomes with ser-/thr-specific phosphatase PP2Ca, respectively, tyr-specific phosphatase PTP1B. Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor, an irrelevant phosphatase (CIP), and an untreated sample were included as controls

Discussion

The discovery and introduction of TKIs into the treatment of malignant disease opened new perspectives and therapeutic options for patients both with leukemias and solid tumors. However, there is emerging evidence that these compounds might also affect normal, nonmalignant cells. In our previous studies, we have investigated the impact of these novel drugs on the immune system by analyzing the functional and phenotypical modulation of antigen-presenting cells and T lymphocytes, in order to evaluate the possible combination of targeted therapies with immunological approaches such as vaccinations. In doing so, we found that several TKIs currently in use have inhibitory effects on the function and differentiation of human and murine dendritic cells and the generation of primary immune responses[12, 13, 39].

In line with this, one study demonstrated that patients treated with IM showed diminished antigen-specific CTL frequencies in contrast to patients treated with IFN-α. The antileukemic effect of IFN-α treatment is known to be based at least in part upon the induction of immunological responses against malignant cells [40]. The described diminished antigen-specific CTL responses under IM treatment might, therefore, indicate that the observed inhibitory in vitro effects evident in this study might also be effective in vivo.

In the present work, we analyzed the possible effects of BCR-ABL inhibiting compounds on the processing and presentation of T cell epitopes. To accomplish this, we utilized an activity-based probe BioALVS that binds to the threonine residues of the active β-subunits in the 20S proteasome. In addition, we performed in vitro digestion of a BCR-ABL-derived peptide using purified proteasomes and mass spectrometry to analyze the direct effects of these drugs on the generation of antigenic peptides.

We found that incubation of the BCR-ABL-positive CML cell line K-562 with IM or NI results in the reduction in the proteasomal activity, which is not due to diminished protein expression or the induction of apoptosis. In line with these results, reduced surface expression of HLA-A2 molecules was detected when K-562 transfectants were incubated with TKIs. Interestingly, similar results were observed when primary cells from a CML patient with a T315I mutation resistant to IM therapy were analyzed. Taken together, these results indicate that this process might be BCR-ABL independent. This was further confirmed when proteasomal activity was also reduced in cells from an additional IM-resistant CML patient with Q252H and E255 K mutations, as well as in IM-resistant K-562R and BCR-ABL-negative cell lines. The observed reduction in the HLA-class I molecules upon treatment with IM or NI might have some impact on the recognition of CML cells by the T cells. However, the low expression of HLA molecules can result in increased NK-mediated cytotoxic activity. As previously reported by Borg et al. [41], treatment of mice with IM resulted in a higher NK cell-mediated recognition and elimination of malignant cells. In addition, they found that patients with gastrointestinal stroma tumors under IM treatment acquire NK cell activation which seems to correlate with the clinical outcome of these patients.

Our results are in contrast to a recently published work by Crawford et al. [42] demonstrating that the proteasomal activity in CML cells might be linked to BCR-ABL expression. Using fluorogenic substrate analysis and application of an activity-based probe, Crawford et al. showed that modulation of BCR-ABL expression by siRNA reduces to some degree the proteasomal activity. However, the direct effects of TKIs were not addressed.

Besides IM or NI, we did not observe any inhibitory effects on proteasomal activity in response to other TKIs such as sorafenib or sunitinib or the PI3 K inhibitor LY294002 in our experiments. We think that this observation indicates that the effect of IM and NI is specific and suggests that it is due to inhibition of proteasomal phosphorylation. This is further supported by the results shown in Fig. 6 where phosphatases were utilized. The TKIs all have different molecular structures and target specificities, and this fact might explain why we observed different effects on proteasomal activity by the used compounds.

Finally, we wanted to prove that IM and NI may have a direct effect on the function of the proteasome. We incubated isolated 20S proteasomes with both TKIs and performed in vitro digestion analysis of a BCR-ABL-deduced peptide that contains two recently described HLA-class I-binding T cell epitopes to HLA-A03 and HLA-B08.

It has been shown that BCR-ABL-derived breakpoint peptides capable of binding to HLA-class I molecules might exist [36]. In addition, several studies were able to demonstrate that an antigen-specific T lymphocyte response against BCR-ABL deduced peptides that bind to HLA-A3, -A11, B8, or both -A3/-A11 can be elicited in vitro [43]. Yotnda et al. [44] identified a HLA-A2.1-restricted peptide from the b3a2 BCR-ABL junctional region that in vitro stimulated HLA-A2 restricted antigen-specific CTL responses using PBMCs from healthy as well as CML donors.

By applying proteasomal degradation of the BCR-ABL protein, Posthuma et al. [38] demonstrated that only the KQSSKALQR (HLA-A03), but not the HLA-B08-restricted GFKQSSKAL peptide can be generated in vitro from eluates of transduced K-562 cells.

In our study, we now show that both epitopes are generated in vitro by proteasomal digestion of a synthetic peptide. In addition, we found a significant difference in the repertoire of generated peptides when the purified i20S proteasomes are treated with IM or NI. The addition of IM or NI resulted in a massive reduction in the generation of the long precursor peptides for the HLA-A03/A11 and –B08 epitopes while the processing of the short peptide sequences increased. Interestingly, in all performed experiments, NI was more effective as compared to IM.

The strong effects of the TKIs NI and IM on proteasomal activity might be explained by changes in the phosphorylation of proteasomal subunits, which could alter proteasomal activity and/or association with proteasome activators.

Lu et al. [45] reported in a recent study that the function of the 20S proteasome is tuned by covalent modifications, such as phosphorylation, and identified 44 new phosphorylation sites in proteasomal subunits. This theory is now further supported by our experiments in which the use of ser-/thr- and tyr-specific phosphatases inhibits the function of the proteasome while an unspecific phosphatase was ineffective.

Our study provides new insight into how IM and NI may modulate the activity of the β-subunits of the 20S proteasome and hence the immunogenicity of malignant cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Solveig Daecke and Anika Beckers for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (PB), Deutsche Krebshilfe (PB), BONFOR Forschungsförderung (AH) and SFB 704 (PB). Parts of this work were presented on the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) as a poster under the same title.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

S. A. E. Held and K. M. Duchardt contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lugo TG, Pendergast AM, Muller AJ, Witte ON. Tyrosine kinase activity and transformation potency of bcr-abl oncogene products. Science. 1990;247:1079–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.2408149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heisterkamp N, Jenster G, ten Hoeve J, Zovich D, Pattengale PK, Groffen J. Acute leukaemia in bcr/abl transgenic mice. Nature. 1990;344:251–253. doi: 10.1038/344251a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochhaus A, O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, et al. Six-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23:1054–1061. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Imatinib mesylate therapy improves survival in patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in the chronic phase: comparison with historic data. Cancer. 2003;98:2636–2642. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy L, Guilhot J, Krahnke T, et al. Survival advantage from imatinib compared with the combination interferon-alpha plus cytarabine in chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia: historical comparison between two phase 3 trials. Blood. 2006;108:1478–1484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, Kuriyan J. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 2000;289:1938–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snead JL, O’Hare T, Eide CA, Deininger MW. New strategies for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: can resistance be avoided? Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8(Suppl 3):S107–S117. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2008.s.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2531–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heine A, Held SA, Bringmann A, Holderried TA, Brossart P. Immunomodulatory effects of anti-angiogenic drugs. Leukemia. 2011;25:899–905. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appel S, Boehmler AM, Grunebach F, et al. Imatinib mesylate affects the development and function of dendritic cells generated from CD34+ peripheral blood progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103:538–544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balabanov S, Appel S, Kanz L, Brossart P, Brummendorf TH. Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibition using imatinib on normal lymphohematopoietic cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1044:168–177. doi: 10.1196/annals.1349.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appel S, Rupf A, Weck MM, Schoor O, Brummendorf TH, Weinschenk T, Grunebach F, Brossart P. Effects of imatinib on monocyte-derived dendritic cells are mediated by inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and Akt signaling pathways. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1928–1940. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brauer KM, Werth D, von Schwarzenberg K, Bringmann A, Kanz L, Grunebach F, Brossart P. BCR-ABL activity is critical for the immunogenicity of chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5489–5497. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salih J, Hilpert J, Placke T, Grunebach F, Steinle A, Salih HR, Krusch M. The BCR/ABL-inhibitors imatinib, nilotinib and dasatinib differentially affect NK cell reactivity. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2119–2128. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seggewiss R, Lore K, Greiner E, Magnusson MK, Price DA, Douek DC, Dunbar CE, Wiestner A. Imatinib inhibits T-cell receptor-mediated T-cell proliferation and activation in a dose-dependent manner. Blood. 2005;105:2473–2479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dietz AB, Souan L, Knutson GJ, Bulur PA, Litzow MR, Vuk-Pavlovic S. Imatinib mesylate inhibits T-cell proliferation in vitro and delayed-type hypersensitivity in vivo. Blood. 2004;104:1094–1099. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichardt VL, Brossart P. Current status of vaccination therapy for leukemias. Curr Hematol Rep. 2005;4:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi T, Tanaka Y, Nieda M, Azuma T, Chiba S, Juji T, Shibata Y, Hirai H. Dendritic cell vaccination for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Leuk Res. 2003;27:795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2126(03)00011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisberg E, Griffin JD. Mechanism of resistance to the ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in BCR/ABL-transformed hematopoietic cell lines. Blood. 2000;95:3498–3505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appel S, Mirakaj V, Bringmann A, Weck MM, Grunebach F, Brossart P. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit toll-like receptor-mediated activation of dendritic cells via the MAP kinase and NF-kappaB pathways. Blood. 2005;106:3888–3894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appel S, Bringmann A, Grunebach F, Weck MM, Bauer J, Brossart P. Epithelial-specific transcription factor ESE-3 is involved in the development of monocyte-derived DCs. Blood. 2006;107:3265–3270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.le Coutre P, Kreuzer KA, Pursche S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and cellular uptake of imatinib and its main metabolite CGP74588. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:313–323. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2542–2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faivre S, Delbaldo C, Vera K, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel oral multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:25–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strumberg D, Richly H, Hilger RA, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the Novel Raf kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor BAY 43–9006 in patients with advanced refractory solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:965–972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berkers CR, Verdoes M, Lichtman E, Fiebiger E, Kessler BM, Anderson KC, Ploegh HL, Ovaa H, Galardy PJ. Activity probe for in vivo profiling of the specificity of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Nat Methods. 2005;2:357–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogyo M, McMaster JS, Gaczynska M, Tortorella D, Goldberg AL, Ploegh H. Covalent modification of the active site threonine of proteasomal beta subunits and the Escherichia coli homolog HslV by a new class of inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler BM, Tortorella D, Altun M, Kisselev AF, Fiebiger E, Hekking BG, Ploegh HL, Overkleeft HS. Extended peptide-based inhibitors efficiently target the proteasome and reveal overlapping specificities of the catalytic beta-subunits. Chem Biol. 2001;8:913–929. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(01)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nencioni A, Schwarzenberg K, Brauer KM, Schmidt SM, Ballestrero A, Grunebach F, Brossart P. Proteasome inhibitor bortezomib modulates TLR4-induced dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2006;108:551–558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nencioni A, Garuti A, Schwarzenberg K, et al. Proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:681–689. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicoletti I, Migliorati G, Pagliacci MC, Grignani F, Riccardi C. A rapid and simple method for measuring thymocyte apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1991;139:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90198-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenzer S, Stoltze L, Schonfisch B, Dengjel J, Muller M, Stevanovic S, Rammensee HG, Schild H. Quantitative analysis of prion-protein degradation by constitutive and immuno-20S proteasomes indicates differences correlated with disease susceptibility. J Immunol. 2004;172:1083–1091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva JC, Denny R, Dorschel CA, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2187–2200. doi: 10.1021/ac048455k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silva JC, Gorenstein MV, Li GZ, Vissers JP, Geromanos SJ. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2006;5:144–156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500230-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bocchia M, Wentworth PA, Southwood S, Sidney J, McGraw K, Scheinberg DA, Sette A. Specific binding of leukemia oncogene fusion protein peptides to HLA class I molecules. Blood. 1995;85:2680–2684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark RE, Dodi IA, Hill SC, et al. Direct evidence that leukemic cells present HLA-associated immunogenic peptides derived from the BCR-ABL b3a2 fusion protein. Blood. 2001;98:2887–2893. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.10.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Posthuma EF, van Bergen CA, Kester MG, et al. Proteosomal degradation of BCR/ABL protein can generate an HLA-A*0301-restricted peptide, but high-avidity T cells recognizing this leukemia-specific antigen were not demonstrated. Haematologica. 2004;89:1062–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hipp MM, Hilf N, Walter S, Werth D, Brauer KM, Radsak MP, Weinschenk T, Singh-Jasuja H, Brossart P. Sorafenib, but not sunitinib, affects function of dendritic cells and induction of primary immune responses. Blood. 2008;111:5610–5620. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burchert A, Wolfl S, Schmidt M, et al. Interferon-alpha, but not the ABL-kinase inhibitor imatinib (STI571), induces expression of myeloblastin and a specific T-cell response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:259–264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borg C, Terme M, Taieb J, et al. Novel mode of action of c-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitors leading to NK cell-dependent antitumor effects. J Clin Investig. 2004;114:379–388. doi: 10.1172/JCI21102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crawford LJ, Windrum P, Magill L, Melo JV, McCallum L, McMullin MF, Ovaa H, Walker B, Irvine AE. Proteasome proteolytic profile is linked to Bcr-Abl expression. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bocchia M, Korontsvit T, Xu Q, Mackinnon S, Yang SY, Sette A, Scheinberg DA. Specific human cellular immunity to bcr-abl oncogene-derived peptides. Blood. 1996;87:3587–3592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yotnda P, Firat H, Garcia-Pons F, Garcia Z, Gourru G, Vernant JP, Lemonnier FA, Leblond V, Langlade-Demoyen P. Cytotoxic T cell response against the chimeric p210 BCR-ABL protein in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2290–2296. doi: 10.1172/JCI488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lu H, Zong C, Wang Y, et al. Revealing the dynamics of the 20 S proteasome phosphoproteome: a combined CID and electron transfer dissociation approach. Mol Cell Proteomics MCP. 2008;7:2073–2089. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800064-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]