Abstract

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-secreting tumor cell immunotherapies have demonstrated long-lasting, and specific anti-tumor immune responses in animal models. The studies reported here specifically evaluate two aspects of the immune response generated by such immunotherapies: the persistence of irradiated tumor cells at the immunization site, and the breadth of the immune response elicited to tumor associated antigens (TAA) derived from the immunotherapy. To further define the mechanism of GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies, immunohistochemistry studies were performed using the B16F10 melanoma tumor model. In contrast to previous reports, our data revealed that the irradiated tumor cells persisted and secreted high levels of GM-CSF at the injection site for more than 21 days. Furthermore, dense infiltrates of dendritic cells were observed only in mice treated with GM-CSF-secreting B16F10 cells, and not in mice treated with unmodified B16F10 cells with or without concurrent injection of rGM-CSF. In addition, histological studies also revealed enhanced neutrophil and CD4+ T cell infiltration, as well as the presence of apoptotic cells, at the injection site of mice treated with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells. To evaluate the scope of the immune response generated by GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies, several related B16 melanoma tumor cell subclones that exist as a result of genetic drift in the original cell line were used to challenge mice previously immunized with GM-CSF-secreting B16F10 cells. These studies revealed that GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies elicit T cell responses that effectively control growth of related but antigenically distinct tumors. Taken together, these studies provide important new insights into the mechanism of action of this promising novel cancer immunotherapy.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-007-0315-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cancer immunotherapy, Tumor immunology, Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, Dendritic cells

Introduction

Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a potent cytokine that improves the function of antigen presenting cells (APCs) by the maturation, activation, and recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs), and/or macrophages and monocytes [1, 2]. Treatment with irradiated whole tumor cells genetically modified to secrete GM-CSF was initially shown to generate specific and long-lasting anti-tumor responses against the poorly immunogenic B16F10 tumor [3]. Subsequently, these cancer immunotherapies were shown to generate potent anti-tumor immunity in numerous preclinical tumor models, including lung, prostate, leukemia, lymphoma, glioma, and breast [4–9]. The subcutaneous or intradermal injection of irradiated GM-CSF-secreting whole tumor cells results in a local reaction characterized by the infiltration of DCs, macrophages, and granulocytes [3, 10]. DCs are recognized as the most potent APC within the immune system, and have been shown to efficiently engulf antigens, mature and migrate to secondary lymphoid organs where they prime and activate tumor-specific lymphocytes [11]. GM-CSF is a potent maturation factor in vitro and in vivo, and generates DCs that express high levels of B7-1, B7-2, MHC II, and CD1d [10]. Depending upon the model used, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as natural killer T cells, are required for optimal anti-tumor efficacy elicited by GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies, highlighting the role of GM-CSF-activated DCs in priming a potent tumor-specific humoral and cellular immune response [3, 12].

Recombinant GM-CSF (rGM-CSF) promotes the survival, proliferation, activation, and differentiation of myeloid lineage progenitor cells. Although co-administration of rGM-CSF at the injection site in conjunction with irradiated whole tumor cells is believed to offer a potential alternative to cytokine secreting tumor cells, GM-CSF has a very short half-life in vivo and is therefore expected to rapidly dissipate from the injection site [13]. Thus, frequent or continuous cytokine administration would be required at the immunization sites to overcome these limitations, and is expected to result in a dissimilar pharmacokinetic profile and less durable effect than GM-CSF-secreting cells. These data are consistent with reports demonstrating that immunization with GM-CSF-secreting cells yielded superior anti-tumor efficacy compared to co-administration of rGM-CSF and irradiated, non-cytokine secreting cells [14, 15].

Although GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies have been extensively characterized in animal models, many aspects of their function remain unclear. In this report we further define the mechanism of this therapy. The studies reported here confirm that immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells induces a more potent anti-tumor response than co-injection of rGM-CSF and irradiated tumor cells. Our data show that tumor cells are present and secrete high levels of GM-CSF at the injection site for at least 21 days. Additionally, dense infiltrates of DCs, neutrophils, and apoptotic cells were observed at the injection site only in mice treated with the GM-CSF-secreting B16F10 cells, and not in mice treated with unmodified B16F10 cells with or without concurrent injection of rGM-CSF. Finally, GM-CSF-secreting whole tumor cell immunotherapies elicited anti-tumor responses to multiple antigens, suggesting that they have the potential to control the growth of metastatic lesions that may have lost one or more antigens by genetic drift. In summary, these studies confirm the ability of GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies to elicit durable tumor-specific immune responses specific for a broad panel of tumor antigens that translate to a significant survival advantage in tumor-bearing animals.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and characterization

The murine B16F0, B16F1, and B16F10 melanoma cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The B16 melanoma cell line was generously provided by D. Pardoll (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA). The generation of the GM-CSF-secreting cell line (designated F10GM or F10GM 200), which produces ∼200 ng/106 cells/24 h of mouse GM-CSF, has previously been described [3]. The F10GM 800 cell population expressing ∼800 ng/106 cells/24 h of mouse GM-CSF was produced by infection with a third generation lentiviral vector driving the expression of murine GM-CSF from a CMV promoter [16]. Vectors were generated by transient transfection into 293T cells as described previously [16]. GM-CSF levels were evaluated by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The B16F10 and F10GM cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) were also generated by infection with a lentiviral vector driving the expression of GFP from a CMV promoter.

Tumor model studies

Female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY, USA) and maintained according to National Institute of Health guidelines. Animal studies were initiated when mice were between 8 and 12 weeks of age. Two types of tumor models were utilized. For tumor treatment studies, tumors were pre-established by subcutaneous injection of 2 × 105 live tumor cells at a dorsal site. Immunizations were performed using either 1 × 106 or 3 × 106 irradiated (10,000 rads) tumor cells, which were injected at a ventral site on day 3 after tumor inoculation. In tumor prevention studies, mice were immunized with 1 × 106 irradiated tumor cells on day 0, followed by challenge with 1 × 106 live tumor cells on day 7. In some groups, 200 ng of recombinant murine GM-CSF (R&D Systems) was co-injected with the tumor cells at the first immunization, with three subsequent injections of 200 ng rGM-CSF administered once per day by subcutaneous injection at the same site. In all survival studies, animals were assessed for tumor growth twice weekly, and sacrificed if tumors became necrotic or exceeded 1,500 mm3 in size. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves and median survival time (MST) were evaluated using GraphPad Prism Software (San Diego, CA, USA). Retro-orbital bleeds were performed and serum was analyzed for GM-CSF levels by ELISA. To evaluate the levels of GM-CSF from the immunization site, the hair was removed by dipilation and the site was collected using an 8 mm biopsy punch. Tissue was homogenized in 0.5 ml RIPA buffer (1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 25% sodium dexydrolate, 2 mM sodium vanadate, 50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl) containing Complete protease inhibitor (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Samples were incubated on ice for 45 min and clarified by centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined by spectrophotometry, and normalized samples were evaluated for GM-CSF expression by ELISA. Mouse experiments were performed according to protocols reviewed and approved by the Cell Genesys Animal Use and Care Committee.

Histology

Immunization sites were excised and fixed in 4% neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde (Newcomer Supply Inc, Middleton, WI, USA), infiltrated with 30% sucrose, and frozen in OCT compound (StatLab Medical Products, Lewisville, TX, USA). Cryostat sections (10 μm) were mounted on Histobond slides (StatLab Medical Products), rehydrated in TBS, permeabilized with 0.2% TritonX-100, and blocked for 1 h in 10% normal serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). DCs, apoptotic cells, CD4+ T cells, or neutrophils were visualized using either hamster anti-mouse CD11c (Serotec, Oxford, UK), rabbit anti-active Caspase 3 (R&D systems), rat anti-mouse CD4 (Serotec), or rat anti-mouse neutrophils (Serotec) primary antibodies, respectively. Bound antibody was detected using Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Slides were mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Labs), and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Germany) equipped with a SPOT RT Slider digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Inc., Sterling Heights, MI, USA). Appropriate filter sets (Chroma Corp., Montpelier, VT, USA) were used to capture DAPI, GFP, and Alexa 594.

Immunization site harvest and flow cytometry

C57BL/6 mice were injected with 2 × 105 live B16F10 tumor cells. Three days later, mice were treated with HBSS or immunized with 3 × 106 B16F10 or F10GM tumor cells. The immunization site was collected using an 8 mm biopsy punch and digested in 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma) and 0.1 mg/ml DNase (Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. Dissociated cells were filtered through a 70 μm filter and directly stained with antibodies for phenotype characterization by FACs analysis. The total number of cells was directly evaluated using a Coulter Counter (Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA). With the exception of langerin (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), antibodies were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). Flow cytometry acquisition and analysis were performed on a FACScan apparatus using CellQuest Pro (BD Biosciences).

51Cr release assay

Activity of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) was assessed using the standard 51Cr release assay. Briefly, animals with pre-established tumors were immunized as described above for a treatment study. Mice were treated every other week with HBSS, or with 1 × 106 irradiated B16F10 or F10GM tumor cells. One week post the final immunization, mice were sacrificed and erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes were stimulated in vitro for 5 days with 1 × 106 irradiated B16F10 cells. After 2 days 25 U of recombinant human IL-2 was added to the media. RMAS target cells were pulsed with 5 μg/ml peptide for 60 min at RT. Peptides used were TRP2180–188 (SVYDFFVWL) [17–19], GP10025–33 (EGSRNQDWL) [20, 21], and MAGE-AX169–176 (LGITYDGM) [22]. Peptide-loaded target cells were labeled with 100 μCi Na512 CrO4 (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) at 37°C for 1 h. The labeled target cells were washed three times and added to 96-well round-bottom microtiter plates at a concentration of 5 × 103 cells/well. Effector cells were added starting from an effector:target ratio of 200:1. After a 4 h incubation at 37°C, supernatant from each well was collected and relative radioactivity (counts per minute) was determined. The percent specific lysis was calculated using the following equation: (ER − SR)/(MR − SR) × 100, where ER = experimental release, SR = spontaneous release, and MR = maximum release. The MR was determined following lysis of the target cells with 1% SDS.

ELISPOT analysis

Antigen-specific responses were evaluated using an INFγ ELISPOT (R&D Systems) assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Animals with pre-established tumors were immunized as described above for a treatment study. Mice were sacrificed 14 days post-immunization, and 5 × 105 erythrocyte-depleted splenocytes were stimulated in vitro for 48 h using 1 × 104 irradiated B16F10, B16, B16F0, or B16F1 tumor cells. Spots were counted using an Immunospot analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd, Cleveland, OH, USA).

Statistical analysis and data presentation

Multi-parameter statistics for the Kaplan–Meier survival curves were performed by a log-Rank test using GraphPad Prism Software. Relative differences between groups were also performed using a Student’s t-test and GraphPad Prism Software.

Results

GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy leads to more potent anti-tumor activity than co-injection of recombinant GM-CSF with tumor cells

Numerous preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated the potency of GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies in enhancing anti-tumor immunity [23]. Local administration of rGM-CSF at the injection site provides one potential alternative to treatment with cytokine-secreting tumor cells. In order to compare the efficacy of a GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy to that of rGM-CSF co-injected with irradiated non-GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells, a tumor prevention study was performed. Mice were immunized with either irradiated B16F10 cells that secreted approximately 200 ng/1 × 106 cells/24 h of GM-CSF (F10GM 200), or irradiated unmodified B16F10 (B16F10) cells in combination with subcutaneous injections (once per day for 4 days) of 200 ng of mouse rGM-CSF (B16F10/rGM 200). Mice were challenged 7 days post-immunization with a lethal dose of live B16F10 tumor cells. All control animals injected with HBSS succumbed to tumor burden 32 days post tumor challenge (Fig. 1a). Animals treated with either irradiated B16F10 tumor cells, or B16F10 cells + rGM-CSF demonstrated only a minor delay in tumor growth resulting in survival of only 10 and 20% of the animals at day 60. In contrast, 100% of animals that received the F10GM 200 tumor cell immunotherapy survived at this time point. Treatment with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells also demonstrated greater efficacy in mice with pre-established tumors (Fig. 1b). For this experiment, mice were first challenged with a lethal dose of live B16F10 tumor cells, and treated 3 days later with one injection of the immunotherapies described above. The MST of animals treated with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy of 58 days was greater than the MST of mice treated with either unmodified B16F10 tumor cells (MST = 48 days, P = 0.0045), or with unmodified B16F10 tumor cells coinjected with rGM-CSF (MST = 48 days, P = 0.0115).

Fig. 1.

Immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells leads to increased survival compared to irradiated tumor cells co-administered in combination with rGM-CSF in tumor-bearing mice. a C57BL/6 mice were immunized with HBSS, 1 × 106 unmodified B16F10 cells, GM-CSF-secreting (∼200 ng/1 × 106 cells/24 h) B16F10 cells (F10GM 200), or B16F10 cells in combination with 200 ng of rGM-CSF (B16F10/rGM 200). The rGM-CSF was co-administered at the immunization site by subcutaneous injection of 200 ng once per day for 4 days. Mice (n = 10/group) were challenged 7 days post-immunization with 1 × 106 live B16F10 tumor cells. Animals were assessed for tumor growth twice weekly, and sacrificed if tumors became necrotic or exceeded 1,500 mm3 in size. Data is presented as a Kaplan–Meier survival curve with n = 10 per group. b To evaluate the aforementioned groups in a treatment setting, C57BL/6 mice were challenged with 2 × 105 live B16F10 tumor cells. Three days later mice were immunized with HBSS, 1 × 106 unmodified B16F10, F10GM 200, or B16F10/rGM 200. Tumor assessment and data analysis was performed as described above. c GM-CSF serum levels following immunization with B16F10 cells and rGM-CSF or GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells. C57BL/6 mice (n = 10/group) were immunized with 1 × 106 B16F10 cells in combination with a single injection of 800 ng rGM-CSF, or with 1 × 106 irradiated GM-CSF-secreting (∼800 ng/1 × 106 cells/24 h) F10GM 800 tumor cells. Serum samples were collected 6, 24, 48, and 72 h post-immunization and GM-CSF levels were determined by ELISA. d Mice immunized with F10GM 800 tumor cells had sustained levels of GM-CSF at the injection site. Animals (n = 6/group) were treated as described in panel c. The immunization site was collected at the time points indicated, processed as described in Sect. “Materials and methods”, and evaluated for GM-CSF levels by ELISA. The background of this assay was ∼70 pg/ml based on the levels of GM-CSF obtained from the immunization site of mice treated with B16F10 (non GM-CSF-secreting) tumor cells

These data suggested that the pharmacokinetic profile of GM-CSF secretion at the injection site may be critical for generating potent anti-tumor immunity. To evaluate this hypothesis, GM-CSF levels were measured in the serum and at the immunization site following treatment. Pilot experiments demonstrated that injection of F10GM 200 tumor cells did not yield detectable GM-CSF serum levels by ELISA (data not shown). Thus, for these studies F10GM tumor cells were selected that secreted higher levels of GM-CSF. F10GM 200 cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding GM-CSF, resulting in a cell population (F10GM 800) that secretes 800 ng/1 × 106 cells/24 h of GM-CSF. Immunization with F10GM 800 cells allows for monitoring of GM-CSF serum pharmacokinetics in vivo by ELISA. Importantly, there was no difference in therapeutic benefit provided by immunotherapy cells that secreted 200 or 800 ng/1 × 106 cells/24 h of GM-CSF (data not shown). To evaluate the pharmacokinetic profile of GM-CSF, mice were injected with either F10GM 800 cells, or with unmodified B16F10 cells + single injection of 800 ng rGM-CSF at the immunotherapy injection site and serum GM-CSF levels monitored over time. As anticipated, a single injection of rGM-CSF yielded high but short-lived GM-CSF serum levels (Fig. 1c). The serum GM-CSF levels of animals injected with the cytokine-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy were significantly lower than in animals that received rGM-CSF, but were sustained for at least 72 h post-administration before they fell below the detection level of the assay. Analysis of the injection site of animals injected with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy confirmed that high levels of GM-CSF persisted locally for at least 21 days (Fig. 1d). In contrast, administration of rGM-CSF resulted in a transient local burst of cytokine expression that rapidly fell below the background levels of the assay.

Irradiated GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells persist for at least 21 days at the injection site and recruit high numbers of DCs

The above results suggest that the level and duration of GM-CSF at the immunotherapy injection site are critical factors in eliciting a potent anti-tumor response. The unexpected duration of GM-CSF at the injection site prompted us to evaluate the persistence of the cellular component of the whole tumor cell immunotherapy at the injection site. These and all of the remaining experiments were performed with the original F10GM tumor cells that secrete 200 ng GM-CSF/1 × 106 cells/24 h in vitro which have been used in the past for preclinical studies evaluating this immunotherapy [24–26]. C57BL/6 mice with pre-existing B16F10 tumors were immunized with irradiated B16F10 cells, irradiated B16F10 cells and four injections (once per day for 4 days) of 200 ng of rGM-CSF (B16F10/rGM), or irradiated F10GM tumor cells. All cells were modified to stably express GFP to enable the tracking of the immunotherapy cells in vivo. The injection site was collected for histological analysis at given intervals from day 1 to 28 post-treatment. In contrast to previous reports suggesting that immunotherapy cells remain at the injection site for about 7 days [10, 27–29], GFP-expressing cells were present in all groups up to 21 days post administration (Fig. 2). No GFP positive cells were visible in any of the groups at 28 days post injection (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Tumor cells persist and efficiently recruit dendritic cells to the injection site following immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells. On day 0, C57BL/6 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2 × 105 B16F10 live tumor cells. Three days later, mice were immunized with 3 × 106 irradiated B16F10 cells, B16F10 cells and four subcutaneous injections (days 3, 4, 5, and 6) of 200 ng of rGM-CSF, or GM-CSF-secreting (∼200 ng/1 × 106cells/24 h) F10GM cells. All tumor cells expressed GFP. Injection sites were collected for histological analysis on days 1, 7, 14, and 21 post-immunization, and stained with DAPI (blue, nuclear staining) and CD11c (red, dendritic cells). GFP-positive tumor cells are shown in green. Stained 10 μm sections were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope and are shown at ×20 magnification. Photomicrographs presented are representative of five mice

Bone marrow-derived DCs present in the skin infiltrate into the immunization site, acquire and process tumor cell antigens, and migrate to the lymphoid organs to activate naïve T cells [30]. Immunohistochemical staining of the immunization sites with the DC marker CD11c revealed a massive infiltration of DCs into the injection site of animals that had received the GM-CSF-expressing F10GM immunotherapy cells, but not into the injection sites of animals treated with the cell control (Fig. 2). Consistent with the anti-tumor efficacy previously observed, only weak infiltration of DCs was observed in animals that had been treated with the B16F10/rGM regimen. In contrast to previous reports that focused on days 1–7 post immunization [10, 27–29], high levels of DCs remained clearly visible up to day 21 in animals immunized with F10GM. In this group, the presence of DCs was markedly reduced by day 28 (data not shown). To obtain a qualitative assessment of the early time points of DC infiltration, the injection site was collected and evaluated for DC numbers and subsets by FACs. Since co-injection of unmodified B16F10 cells and rGM-CSF failed to result in a pronounced anti-tumor response and high numbers of DCs at the injection site, this group was excluded from future studies. Mice receiving the F10GM immunotherapy had a dramatic increase in the number of total and CD11c+ cells at day 4 post-immunization relative to the baseline levels of the B16F10 immunotherapy and HBSS-treated mice (Fig. 3a, b). The CD11c+ cells corresponded to Langerhans DCs based on co-staining for Langerin and MHC class II [13, 31]. Increased numbers of total and CD11c+ cells were also observed in the DLN (Supplementary Figure 1a), suggesting that activated DCs migrate from the injection site to the DLN. Furthermore, the CD11c+ DCs obtained from the DLN of mice that received the F10GM immunotherapy expressed increased levels of the activation markers CD40, CD80, CD86, MHC class II, CD1d, and CCR7 compared to mice injected with B16F10 or HBSS (Supplementary Figure 1b). DCs from the DLNs were also tested for their capacity to stimulate in vitro the proliferation of antigen-specific T cells. DCs derived from mice treated with the GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy were potent stimulators of antigen specific T cell proliferation, whereas no significant proliferation was induced by DCs obtained from mice treated with B16F10 cells or B16F10/rGM (Supplementary Figure 1c). Taken together, treatment with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells results in a pronounced increase of activated and functional DCs at the injection site and DLN of mice.

Fig. 3.

Immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells increased the number of DCs at the injection site. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated subcutaneously with 2 × 105 live B16F10 tumor cells. Three days later, mice were immunized with 3 × 106 irradiated B16F10 or F10GM tumor cells. At 1, 4, and 8 days post-immunization, the injection site was collected and stained with CD11c, MHC class II (I-Ab), and langerin. a Histograms demonstrating the qualitative increase in the percentage of CD11c+ and MHC class II+/Langerin+ (gated on CD11c+) cells at the immunization site. The data shown are from day 4 post-immunization. b Qualitative analysis of the total number of cells (top panels), total number of dendritic cells (based on a CD11c+ gate; middle panels), and total number of MHC class II+/Langerin+ cells at the immunization site (bottom panels)

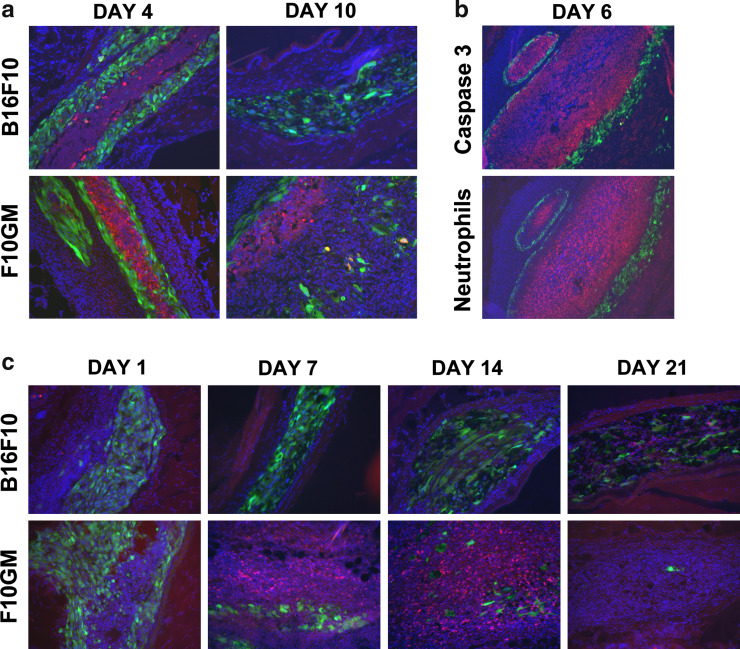

Treatment of mice with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells leads to increased numbers of apoptotic cells as well as CD4 T-cells at the injection site

The immunohistochemistry data revealed a qualitative difference in the number of GFP expressing cells among the groups starting at day 7 post immunization, and was most evident at later time points. Animals injected with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy had fewer GFP positive cells at later time points than animals that received B16F10 either with or without concurrent injections of rGM-CSF (Fig. 2). This decrease in immunotherapy cell number in the F10GM treatment group correlated with increased caspase 3 staining at days 4 and 10 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, no increase of caspase 3 positive cells was observed in B16F10 (Fig. 4a) or B16F10/rGM treated mice (data not shown). Additionally, a dense infiltrate of neutrophils was also observed at the injection site of F10GM treated mice compared to the control groups (Fig. 4b). The caspase 3 positive cells appeared to be comprised of both neutrophils and tumor cells. At the center of the injection site, the neutrophils were encompassed and surrounded by caspase 3 positive cells. Enhanced numbers of apoptotic cells were also observed adjacent to the metabolically active and intact (based on GFP fluorescence) immunotherapy cells. These caspase 3 positive cells most likely reflected apoptotic immunotherapy cells that no longer express GFP. Notably, staining for macrophages revealed dense infiltrates at early time points, but no qualitative differences were observed between the groups. Immunohistochemistry using a CD4-specific antibody showed transient infiltration of CD4+ T cells into the injection site only in animals that had been immunized with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy (Fig. 4c). The peak of CD4+ T cell infiltration was at day 14, and very few CD4+ T cells were found at the immunization site at day 21. Undetectable or low levels of CD4 infiltration were observed in the B16F10 (Fig. 4c) and B16F10/rGM groups (data not shown), respectively.

Fig. 4.

Increased apoptosis was observed at the immunization site of F10GM treated mice. Animals were treated and evaluated as described in Fig. 2. a The injection sites were collected for histological analysis and stained with DAPI (blue, nuclear staining) and caspase 3 (red, apoptotic cells). GFP-positive tumor cells are shown in green. On days 4 and 10 post-immunization, increased numbers of caspase 3 positive cells were observed in the F10GM immunized mice compared to animals treated with B16F10. Sections are at ×20 magnification. b The dense infiltrate of apoptotic cells observed in F10GM mice appeared to be comprised of both neutrophils and tumor cells. The injection sites of F10GM treated mice were collected for histological analysis and stained with DAPI (blue, nuclear staining) and either caspase 3 (red) or neutrophils (red). GFP-positive tumor cells are shown in green. Enhanced neutrophil infiltration was only observed in F10GM treated mice. Sections are at ×10 magnification. c Tumor cells efficiently recruit CD4+ T-cells to the injection site following immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells. Injection sites were collected for histological analysis on days 1, 7, 14, and 21 post-immunization, and stained with DAPI (blue, nuclear staining) and CD4 (red). GFP-positive tumor cells are shown in green. Stained 10 μm sections were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axioplan microscope and are shown at ×20 magnification. Photomicrographs presented are representative of five mice

GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy enhances antigen-specific T and B cell responses

Activated DCs migrate to the DLN and prime naïve T cells. Although this paradigm is well established, the timing of this response has not been documented after immunization with a GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy. To determine the kinetics of T cell activation, mice bearing pre-established B16F10 tumors were immunized with either unmodified B16F10 cells or GM-CSF-secreting F10GM cells. The B16F10 cells used for challenge and the cancer immunotherapy cells were genetically modified to express OVA as a surrogate antigen to circumvent previously encountered technical problems with using an in vivo CTL assay to detect T cell responses specific for B16F10 antigens. Using the OVA modified B16F10 model, T cell responses evaluated at days 11, 14, and 18 post-tumor inoculation revealed a strong in vivo CTL response in both treatment groups (saturating in the F10GM group) on day 11 post-immunization (Supplementary Figure 2a, b). The response gradually decreased from day 11 to day 18 post-tumor inoculation, with a clear trend toward significantly higher OVA-specific T-cell activity in the F10GM-treated group than in the group immunized with B16F10 cells only.

Th1 T cell responses are often associated with cell-mediated immunity, while Th2 responses are essential for antibody-mediated immunity. To evaluate the specific type of immune response elicited by GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy, supernatants from splenocytes re-stimulated with irradiated B16F10 cells were evaluated using a cytokine cytometric bead array (Supplementary Figure 2c). Splenocytes from HBSS or B16F10-injected mice expressed baseline levels of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines, whereas splenocytes from mice immunized with GM-CSF-secreting B16F10 cells expressed high levels of both Th1 (IFNγ, TNFα and IL-2) and Th2 (IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10) cytokines, demonstrating broad Th1 and Th2 immune responses induced by the F10GM immunotherapy.

To evaluate the humoral response to the OVA antigen in tumor-bearing mice, animals were immunized as described for the DC presentation assay, and serum was collected 14 days post immunotherapy for the evaluation of OVA-specific total IgG antibodies. Animals immunized with the GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy had increased titers of OVA-specific antibodies compared to animals that had been immunized with HBSS or B16F10 cells (Supplementary Figure 2d). Taken together, these data demonstrate that GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapies elicit potent T and B cell responses.

GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies elicit T-cell responses against multiple tumor associated antigens

Tumors have been shown to escape immune recognition by altering antigen expression [32]. To evaluate the ability of a GM-CSF-secreting immunotherapy to generate T-cell responses to multiple immunotherapy derived tumor antigens, B16F10 tumor bearing C57BL/6 mice were immunized with either irradiated B16F10 or F10GM immunotherapy cells. Mice received either one or two injections of immunotherapy and splenocytes were evaluated 4 and 12 days after the last immunization using an in vitro CTL assay. The target cells used for this assay were RMAS cells pulsed with peptides specific for TRP2180–188 SVYDFFVWL and GP10025–33 EGSRNQDWL, which have been extensively used with the B16F10 tumor model [18–21, 33]. In addition, the response to a recently identified peptide (MAGE-AX169–176 LGITYDGM) derived from the murine MAGE-A1-3 and MAGE-A5 proteins was evaluated [22] which has previously been shown to generate protective immunity in a B78-D14 melanoma tumor model. Mice immunized once with the F10GM immunotherapy demonstrated low levels of peptide specific CTL activity on day 4 post immunization (Fig. 5a), but on day 12 specific lysis was observed for all three of the peptides evaluated (Fig. 5b). In mice that received two injections of F10GM immunotherapy, peptide specific CTL activity was already observed on day 4 for TRP-2 and GP100, and CTL responses specific for all three peptides were present by day 12 post second immunization. Furthermore, the T-cell responses specific for all three peptides was stronger in animals that received two immunotherapy treatments than in animals that received only one injection of the immunotherapy, demonstrating that repeat immunizations with a GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy results in enhanced T-cell activity specific for multiple tumor-specific antigens.

Fig. 5.

T-cell responses specific for multiple tumor antigens were elicited in mice immunized with a GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy. Mice were immunized bi-weekly with HBSS, or with 3 × 106 irradiated B16F10 or F10GM tumor cells. On day 4 (a) and 12 (b) post the first or second (multiple) immunization, splenocytes were collected and stimulated in vitro for 5 days with irradiated B16F10 tumor cells. Antigen specific responses were assayed by 51Cr release for lysis of peptide pulsed RMAS cells. The peptides used for these studies were TRP2180–188 (SVYDFFVWL), GP10025–33 (EGSRNQDWL), and MAGE-AX169–176 (LGITYDGM)

GM-CSF-secreting immunotherapies can target antigenically related but distinct tumors

Cancer cells are heterogeneous in nature, and for an immunotherapy to be effective in patients with metastatic disease it is critical that the immune response can effectively control metastatic lesions that may have lost particular antigens expressed in the primary tumor. To evaluate the ability of GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies to recognize and destroy genetically and phenotypically different tumors, studies were performed using several related B16 melanoma tumor cell subclones that exist as a result of genetic variation or drift in the original cell line. The four cell lines appear phenotypically different, with variations in cell growth, shape, and pigmentation (data not shown). Mice were immunized with HBSS, B16F10, or GM-CSF-secreting F10GM cells. Seven days post immunization; mice were challenged with a subcutaneous injection of either B16, B16F0, B16F1, or B16F10 tumor cells (Fig. 6a–d, upper boxes). The MST of animals injected with HBSS was 10–15 days, compared to the prolonged survival observed with F10GM treated animals, in which the MST exceeded 68 days. Although limited survival benefit was observed in animals treated with unmodified B16F10 cells, survival of mice challenged with B16F10 (MST = 36) or B16 (MST = 28) cell lines was better than in mice challenged with the B16F0 (MST = 17) and B16F1 (MST = 15) cell lines. Taken together, these data suggest that the two pairs of B16 melanoma cell lines differ in crucial rejection antigens, a limitation that GM-CSF-secreting immunotherapies are able to overcome. To evaluate T cell responses against the different cell lines, mice were immunized with HBSS or either unmodified B16F10 cells or GM-CSF-secreting F10GM cells and seven days later challenged with live B16F10 tumor cells. Splenocytes were harvested 14 days post immunization, and evaluated by INFγ ELISPOT analysis using irradiated tumor cells as stimulators (Fig. 6a–d). Enhanced numbers of INFγ secreting T cells were observed after immunization with GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy, which in all cases correlated with anti-tumor efficacy. Furthermore, moderate ELISPOT responses were observed using irradiated B16F10 and B16 cell lines as stimulators, again consistent with the survival data described above. Overall, these data demonstrate that GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies elicit anti-tumor responses to a broad panel of tumor antigens that can control growth of tumors that are antigenically related but distinct from the primary tumor and the immunotherapy cells.

Fig. 6.

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor cell immunotherapies lead to broad antigen-specific immune response. On day 0, mice were immunized with HBSS, 1 × 106 irradiated B16F10 (B16F10) or GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells (F10GM). Animals were challenged 7 days later with 1 × 106 live cells of the indicated B16 subclones, including B16F10 (a), B16 (b), B16F0 (c), and B16F1 (d). The treatment regimen and median survival time for each group is indicated in the upper box of each panel (n = 10/group). Subgroups of mice from the groups described in panel A were sacrificed 14 days post-immunization. The lower charts show IFNγ ELISPOT analysis of the splenocytes performed using irradiated B16F10 (a), B16 (b), B16F0 (c), and B16F1 (d) tumor cells as stimulators

Discussion

Immunization with autologous or allogeneic tumor cells genetically modified to secrete GM-CSF has been shown to induce anti-tumor immunity in a number of preclinical and clinical studies [12, 29, 34, 35]. Despite extensive studies of such immunotherapies, many aspects of how they generate potent anti-tumor immunity remain to be elucidated. The studies presented here revealed several novel findings. Specifically, that GM-CSF-secreting, irradiated tumor cells persisted and secreted high levels of GM-CSF for at least 21 days at the injection site, resulting in durable recruitment and activation of DCs. In addition, enhanced numbers of neutrophils and CD4+ T-cells, as well as apoptotic cells, were only observed at the injection site of mice treated with a GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy. Furthermore, evaluation of the T-cell response revealed that GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapies yielded responses specific for multiple immunotherapy derived tumor antigens and that these T-cell responses were sufficient to target genetically distinct tumors. Lastly, it could be demonstrated that multiple immunotherapy treatments result in an enhancement of these polyvalent T-cell responses.

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is a potent immune stimulator and an effective adjuvant used in various therapies [1, 2]. Our findings confirm that the pharmacokinetic profile of GM-CSF secreted from whole tumor cell immunotherapies is crucial for effectively recruiting DCs to the injection site and ultimately generating a potent anti-tumor response [14, 15]. This can, in part, be explained by the short half-life (0.92 ± 0.04 min.) of rGM-CSF in vivo [13], although other factors may play a role. One other approach to overcoming this limitation is polyethylene glycol-modified GM-CSF (pGM-CSF) or GM-CSF encoded microspheres. It has previously been shown that pGM-CSF has an increased half-life (15.9 ± 1.5 min.) in vivo, and that administration of pGM-CSF to mice for 5–10 days resulted in an expansion of myeloid derived DCs (CD11b+/CD11c+) that express costimulatory proteins and efficiently capture, process, and present antigens [13]. Another alternative to immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells would be the use of osmotic pumps. However, the cell doses of tumor cell immunotherapies currently used in clinic require injections at multiple sites, which make the use of minipumps impractical if one were to consider delivery of rGM-CSF at close proximity to multiple injection sites. It has also previously been shown that immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells generates superior anti-tumor responses when compared to osmotic pumps or repeated injections [6, 14]. Although systemic GM-CSF levels cannot be detected after day 4 in animal models and patients following injection with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy [36, 37], our studies demonstrate that the gene-modified tumor cells are metabolically active and secrete high levels of GM-CSF in the local microenvironment only, mimicking the natural paracrine biology of cytokine action.

Immunohistochemical data suggest that apoptosis of irradiated tumor cells at the injection site was more pronounced in animals treated with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy than the B16F10 cells. Although controversy still exists as to whether apoptotic or necrotic cells elicit greater anti-tumor responses [38–41], it appears that the timing and/or mechanism of cell death are different between the unmodified and GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy cells, which in the latter group might provide an increased number of tumor antigens or antigens in a preferred form for DCs and thus generate a more potent immune response. Taken together, these data are consistent with previous reports suggesting that GM-CSF matured DCs efficiently capture apoptotic tumor cells and cross-present antigens on MHC class I molecules for recognition by host CD8+ T-cells [10, 11, 13, 42].

Neutrophils are constantly being produced from bone marrow progenitors, and under normal physiological conditions undergo apoptosis to maintain homeostasis [43]. GM-CSF has a well established role as a survival factor for neutrophils by inhibiting caspase 3 mediated apoptosis under pro-inflammatory conditions [44, 45]. These reports are consistent with the pronounced infiltration of neutrophils observed at the injection site of mice treated with the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy. Although the apoptosis of neutrophils also appeared to be enhanced at the injection site, this may reflect turnover of the high numbers of neutrophils present. Given the known crosstalk of neutrophils and DCs in mediating innate and adaptive immune responses [46], studies to evaluate these interesting observations are currently underway.

Our findings are consistent with numerous reports demonstrating that immunization with GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells results in increased numbers of activated DC, as well as potent anti-tumor T cell responses [3, 42]. Although it has been well documented in clinical studies evaluating allogeneic GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies that DCs, macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, and/or lymphocytes are observed at the injection sites [10, 27–29], our data demonstrates that some of the irradiated immunotherapy cells persist long-term at the injection site and secrete GM-CSF locally, resulting in potent and durable infiltration of DCs for at least 21 days in vivo. It has previously been shown that the spatial distribution of the immunotherapy injections is important in maximizing the anti-tumor response. Injections of the GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells at multiple sites has been shown to elicit greater anti-tumor efficacy than when injected at one site only, suggesting that priming of immune responses at multiple DLN increases the total number of activated DCs and T cells [47]. These data suggest that distributing the injections over multiple sites also increases the likelihood of priming T cells against multiple TAA, and thus generating a broader pool of tumor-specific T cells.

Although immunotherapies have been shown to elicit potent TAA-specific T cell responses [48], tumors are genetically heterogeneous and may alter antigen expression to escape an immune response [32, 49, 50]. These effects are most pronounced when an active immunotherapy targets only a single antigen, as was shown in adoptive transfer studies with T-cell clones specific for MART1 to treat patients with metastatic melanoma [51]. This resulted in the selective loss of MART1 expression in relapsing or residual nodules of 3/5 patients. Thus, for an immunotherapy to be most effective long-term, it is crucial to elicit a durable immune response to a broad panel of tumor specific antigens. Whereas previous reports focused on tracking a single antigen only, the studies presented herein demonstrate for the first time that treatment with a GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy generated immune responses to multiple antigens after one treatment. In addition, responses to some antigens (most likely weak antigens) are only elicited after multiple treatments and that the T-cell responses are augmented by repeated cycles of the immunotherapy. These data are consistent with the observation that patients with renal cell carcinoma treated with an autologous GM-CSF-secreting immunotherapy developed immune responses to various antigens [52]. It has previously been shown that bone marrow-derived DCs capture dying cells, process, and present antigens to T cells by cross-presentation [48, 53], and our data suggests that GM-CSF may augment the effective presentation of antigens by professional APCs (e.g., skin Langerhans cells). This is not only critical for initial tumor eradication, but also essential for the eradication of metastatic disease and/or protection against cancer relapse.

In conclusion, data presented here show that GM-CSF-secreting tumor cells persist at the immunization site for at least 21 days, resulting in long-term recruitment of DCs that prime tumor antigen specific immune responses to a broad panel of tumor-specific antigens. These data clearly suggest that the pharmacokinetics of GM-CSF administration is crucial in generating the most effective immune response. Clinical studies evaluating GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapies in prostate cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, acute myelogenous leukemia, and chronic leukemia are currently underway, and these studies facilitate our understanding of these promising new cancer immunotherapies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Harding and P. Working for critical reading of the manuscript, and R. Prell for helpful discussions. B. Batiste, J. Ho, T. Langer, and S. Tanciongo are gratefully acknowledged for their technical assistance.

References

- 1.Chang DZ, Lomazow W, Joy Somberg C, Stan R, Perales MA. Granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor: an adjuvant for cancer vaccines. Hematology. 2004;9:207–215. doi: 10.1080/10245330410001701549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleetwood AJ, Cook AD, Hamilton JA. Functions of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Crit Rev Immunol. 2005;25:405–428. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v25.i5.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, Golumbek P, Levitsky H, Brose K, Jackson V, Hamada H, Pardoll D, Mulligan RC. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3539–3543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrello I, Sotomayor EM, Rattis FM, Cooke SK, Gu L, Levitsky HI. Sustaining the graft-versus-tumor effect through posttransplant immunization with granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing tumor vaccines. Blood. 2000;95:3011–3019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machiels JP, Reilly RT, Emens LA, Ercolini AM, Lei RY, Weintraub D, Okoye FI, Jaffee EM. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel enhance the antitumor immune response of granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor-secreting whole-cell vaccines in HER-2/neu tolerized mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3689–3697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driessens G, Hamdane M, Cool V, Velu T, Bruyns C. Highly successful therapeutic vaccinations combining dendritic cells and tumor cells secreting granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8435–8442. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanda MG, Ayyagari SR, Jaffee EM, Epstein JI, Clift SL, Cohen LK, Dranoff G, Pardoll DM, Mulligan RC, Simons JW. Demonstration of a rational strategy for human prostate cancer gene therapy. J Urol. 1994;151:622–628. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Dranoff G, Weinstein HJ, Ferrara JL, Bierer BE, Croop JM. Gene immunotherapy in murine acute myeloid leukemia: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor tumor cell vaccines elicit more potent antitumor immunity compared with B7 family and other cytokine vaccines. Blood. 1998;91:222–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levitsky HI, Montgomery J, Ahmadzadeh M, Staveley-O’Carroll K, Guarnieri F, Longo DL, Kwak LW. Immunization with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-transduced, but not B7-1-transduced, lymphoma cells primes idiotype-specific T cells and generates potent systemic antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 1996;156:3858–3865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mach N, Gillessen S, Wilson SB, Sheehan C, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Differences in dendritic cells stimulated in vivo by tumors engineered to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor or Flt3-ligand. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3239–3246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang AY, Golumbek P, Ahmadzadeh M, Jaffee E, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. Role of bone marrow-derived cells in presenting MHC class I-restricted tumor antigens. Science. 1994;264:961–965. doi: 10.1126/science.7513904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dranoff G. GM-CSF-secreting melanoma vaccines. Oncogene. 2003;22:3188–192. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daro E, Pulendran B, Brasel K, Teepe M, Pettit D, Lynch DH, Vremec D, Robb L, Shortman K, McKenna HJ, Maliszewski CR, Maraskovsky E. Polyethylene glycol-modified GM-CSF expands CD11b(high)CD11c(high) but notCD11b(low)CD11c(high) murine dendritic cells in vivo: a comparative analysis with Flt3 ligand. J Immunol. 2000;165:49–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi FS, Weber S, Gan J, Rakhmilevich AL, Mahvi DM. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) secreted by cDNA-transfected tumor cells induces a more potent antitumor response than exogenous GM-CSF. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:81–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Golumbek PT, Azhari R, Jaffee EM, Levitsky HI, Lazenby A, Leong K, Pardoll DM. Controlled release, biodegradable cytokine depots: a new approach in cancer vaccine design. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5841–5844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dull T, Zufferey R, Kelly M, Mandel RJ, Nguyen M, Trono D, Naldini L. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J Virol. 1998;72:8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji Q, Gondek D, Hurwitz AA. Provision of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor converts an autoimmune response to a self-antigen into an antitumor response. J Immunol. 2005;175:1456–1463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalat M, Kupcu Z, Schuller S, Zalusky D, Zehetner M, Paster W, Schweighoffer T. In vivo plasmid electroporation induces tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses and delays tumor growth in a syngeneic mouse melanoma model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5489–5494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloom MB, Perry-Lalley D, Robbins PF, Li Y, el-Gamil M, Rosenberg SA, Yang JC. Identification of tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J Exp Med. 1997;185:453–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, de Jong LA, Vyth-Dreese FA, Dellemijn TA, Antony PA, Spiess PJ, Palmer DC, Heimann DM, Klebanoff CA, Yu Z, Hwang LN, Feigenbaum L, Kruisbeek AM, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overwijk WW, Tsung A, Irvine KR, Parkhurst MR, Goletz TJ, Tsung K, Carroll MW, Liu C, Moss B, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. gp100/pmel 17 is a murine tumor rejection antigen: induction of “self”-reactive, tumoricidal T cells using high-affinity, altered peptide ligand. J Exp Med. 1998;188:277–286. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eggert AO, Andersen MH, Voigt H, Schrama D, Kampgen E, Straten PT, Becker JC. Characterization of mouse MAGE-derived H-2Kb-restricted CTL epitopes. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3285–3290. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nemunaitis J. Vaccines in cancer: GVAX, a GM-CSF gene vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2005;4:259–274. doi: 10.1586/14760584.4.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B, Lalani AS, Harding TC, Luan B, Koprivnikar K, Huan Tu G, Prell R, VanRoey MJ, Simmons AD, Jooss K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade reduces intratumoral regulatory t cells and enhances the efficacy of a GM-CSF-secreting cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6808–6816. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prell RA, Li B, Lin JM, VanRoey M, Jooss K. Administration of IFN-alpha enhances the efficacy of a granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor-secreting tumor cell vaccine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2449–2456. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prell RA, Gearin L, Simmons A, Vanroey M, Jooss K. The anti-tumor efficacy of a GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell vaccine is not inhibited by docetaxel administration. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;55:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0116-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simons JW, Jaffee EM, Weber CE, Levitsky HI, Nelson WG, Carducci MA, Lazenby AJ, Cohen LK, Finn CC, Clift SM, Hauda KM, Beck LA, Leiferman KM, Owens AH, Jr, Piantadosi S, Dranoff G, Mulligan RC, Pardoll DM, Marshall FF. Bioactivity of autologous irradiated renal cell carcinoma vaccines generated by ex vivo granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene transfer. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1537–1546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salgia R, Lynch T, Skarin A, Lucca J, Lynch C, Jung K, Hodi FS, Jaklitsch M, Mentzer S, Swanson S, Lukanich J, Bueno R, Wain J, Mathisen D, Wright C, Fidias P, Donahue D, Clift S, Hardy S, Neuberg D, Mulligan R, Webb I, Sugarbaker D, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Vaccination with irradiated autologous tumor cells engineered to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor augments antitumor immunity in some patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:624–630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang AE, Li Q, Bishop DK, Normolle DP, Redman BD, Nickoloff BJ. Immunogenetic therapy of human melanoma utilizing autologous tumor cells transduced to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:839–850. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Randolph GJ, Angeli V, Swartz MA. Dendritic-cell trafficking to lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:617–628. doi: 10.1038/nri1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douillard P, Stoitzner P, Tripp CH, Clair-Moninot V, Ait-Yahia S, McLellan AD, Eggert A, Romani N, Saeland S. Mouse lymphoid tissue contains distinct subsets of langerin/CD207 dendritic cells, only one of which represents epidermal-derived Langerhans cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:983–994. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khong HT, Restifo NP. Natural selection of tumor variants in the generation of “tumor escape” phenotypes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leitch J, Fraser K, Lane C, Putzu K, Adema GJ, Zhang QJ, Jefferies WA, Bramson JL, Wan Y. CTL-dependent and -independent antitumor immunity is determined by the tumor not the vaccine. J Immunol. 2004;172:5200–5205. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soiffer R, Lynch T, Mihm M, Jung K, Rhuda C, Schmollinger JC, Hodi FS, Liebster L, Lam P, Mentzer S, Singer S, Tanabe KK, Cosimi AB, Duda R, Sober A, Bhan A, Daley J, Neuberg D, Parry G, Rokovich J, Richards L, Drayer J, Berns A, Clift S, Cohen LK, Mulligan RC, Dranoff G. Vaccination with irradiated autologous melanoma cells engineered to secrete human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor generates potent antitumor immunity in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13141–13146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soiffer R, Hodi FS, Haluska F, Jung K, Gillessen S, Singer S, Tanabe K, Duda R, Mentzer S, Jaklitsch M, Bueno R, Clift S, Hardy S, Neuberg D, Mulligan R, Webb I, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Vaccination with irradiated, autologous melanoma cells engineered to secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor by adenoviral-mediated gene transfer augments antitumor immunity in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3343–3350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nemunaitis J, Jahan T, Ross H, Sterman D, Richards D, Fox B, Jablons D, Aimi J, Lin A, Hege K. Phase 1/2 trial of autologous tumor mixed with an allogeneic GVAX((R)) vaccine in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13:555–562. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G, Bronte V, Borrello I. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6337–6343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheffer SR, Nave H, Korangy F, Schlote K, Pabst R, Jaffee EM, Manns MP, Greten TF. Apoptotic, but not necrotic, tumor cell vaccines induce a potent immune response in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:205–211. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magner WJ, Tomasi TB. Apoptotic and necrotic cells induced by different agents vary in their expression of MHC and costimulatory genes. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotera Y, Shimizu K, Mule JJ. Comparative analysis of necrotic and apoptotic tumor cells as a source of antigen(s) in dendritic cell-based immunization. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8105–8109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Restifo NP. Building better vaccines: how apoptotic cell death can induce inflammation and activate innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:597–603. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon HU. Neutrophil apoptosis pathways and their modifications in inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2003;193:101–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2003.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colotta F, Re F, Polentarutti N, Sozzani S, Mantovani A. Modulation of granulocyte survival and programmed cell death by cytokines and bacterial products. Blood. 1992;80:2012–2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brach MA, deVos S, Gruss HJ, Herrmann F. Prolongation of survival of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor is caused by inhibition of programmed cell death. Blood. 1992;80:2920–2924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Gisbergen KP, Geijtenbeek TB, van Kooyk Y. Close encounters of neutrophils and DCs. Trends Immunol. 2005;26:626–631. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaffee EM, Thomas MC, Huang AY, Hauda KM, Levitsky HI, Pardoll DM. Enhanced immune priming with spatial distribution of paracrine cytokine vaccines. J Immunother Emphasis Tumor Immunol. 1996;19:176–183. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199605000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas AM, Santarsiero LM, Lutz ER, Armstrong TD, Chen YC, Huang LQ, Laheru DA, Goggins M, Hruban RH, Jaffee EM. Mesothelin-specific CD8(+) T cell responses provide evidence of in vivo cross-priming by antigen-presenting cells in vaccinated pancreatic cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2004;200:297–306. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmad M, Rees RC, Ali SA. Escape from immunotherapy: possible mechanisms that influence tumor regression/progression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:844–854. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0540-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller AM, Pisa P. Tumor escape mechanisms in prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;56:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0110-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16168–16173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou X, Jun do Y, Thomas AM, Huang X, Huang LQ, Mautner J, Mo W, Robbins PF, Pardoll DM, Jaffee EM. Diverse CD8+ T-cell responses to renal cell carcinoma antigens in patients treated with an autologous granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene-transduced renal tumor cell vaccine. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1079–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knutson KL, Disis ML. Tumor antigen-specific T helper cells in cancer immunity and immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:721–728. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.