Abstract

Aim: The aim of this study was to develop an immunotherapy specific to a malignant glioma by examining the efficacy of glioma tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) as well as the anti-tumor immunity by vaccination with dendritic cells (DC) engineered to express murine IL-12 using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer and pulsed with a GL26 glioma cell lysate (AdVIL-12/DC+GL26) was investigated. Experimentl: For measuring CTL activity, splenocytes were harvested from the mice immunized with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 and restimulated with syngeneic GL26 for 7 days. The frequencies of antigen-specific cytokine-secreting T cell were determined with mIFN-γ ELISPOT. The cytotoxicity of CTL was assessed in a standard 51Cr-release assay. For the protective study in the subcutaneous tumor model, the mice were vaccinated subcutaneously (s.c) with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in the right flanks on day −21, −14 and −7. On day 7, the mice were challenged with 1×106 GL26 tumor cells in the shaved left flank. For a protective study in the intracranial tumor model, the mice were vaccinated with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 s.c in the right flanks on days −21, −14 and −7. Fresh 1×104 GL26 cells were inoculated into the brain on day 0. To prove a therapeutic benefit in established tumors, subcutaneous or intracranial GL26 tumor-bearing mice were vaccinated s.c with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 on day 5, 12 and 19 after tumor cell inoculation. Results: Splenocytes from the mice vaccinated with the AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 showed enhanced induction of tumor-specific CTL and increased numbers of IFN-γ: secreting T cells by ELISPOT. Moreover, vaccination of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 enhanced the induction of anti-tumor immunity in both the subcutaneous and intracranial tumor models. Conclusions: These preclinical model results suggest that DC engineered to express IL-12 and pulsed with a tumor lysate could be used in a possible immunotherapeutic strategy for malignant glioma.

Keywords: Dendritic cell, Interleukin-12, Glioma, Cytotoxic T cells, Anti-tumor immunity

Introduction

Malignant gliomas are the most common primary brain tumor of the central nervous system in adults [1]. The prognosis for patients who are diagnosed with a high-grade glioma is very poor regardless of the conventional treatments including surgical removal, radiotherapy and chemotherapy [2]. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies for these brain tumors are necessary.

Tumor immunotherapy including the dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccine, cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), lymphokine-activated killer cells (LAK), natural killer cells (NK) and cytokines have been studied as potential treatments for malignant brain tumors [3–7]. However, these strategies require further study to improve consistent tumor destruction, extended life span, safety and feasibility for cancer patients.

In order for T cell mediated immune responses against tumor cells to occur, antigen-presenting cells (APC) may be needed to efficiently process and present the tumor antigen to T cells [8]. The central nervous system (CNS) is an immunologically privileged site, which protects the irreplaceable neurons from the potentially destructive immune effector mechanisms. Furthermore, glioma cells are poorly immunogenic because they lack the expression of the B-7 costimulatory molecule and the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines including TGF-β and IL-10, which might inhibit the function of APC [9]. However, several studies have shown that systemic immunotherapy using DC or cytokine is capable of inducing a tumor antigen-specific immunity within the immunologically privileged brain, confirming that the CNS may not be an absolute barrier to DC-based immunotherapy or cytokine-based immunotherapy [10–12]. DC is believed to be essential for stimulating tumor-specific CTL and inducing the protective and therapeutic anti-tumor immunity against cancer cells because of their capacity as potent APC [13]. DC also expresses high levels of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigen and costimulatory molecules.

Many methods for antigen priming aimed at inducing anti-tumor immune responses by DC-based vaccination have been attempted. For example, the DC were either transduced by viral vectors encoding the tumor antigens [14] or pulsed with a tumor cell lysate [15], apoptotic tumor cells [16], synthetic peptide [17] and tumor RNA [18].

Recently, several studies have shown that tumor cell lysates may carry the potential known and unknown antigens. Patient with melanoma was observed to have an increased frequency of MART-1- and gp100-reactive CD8+ T cells after vaccination with DC pulsed with tumor cell lysate [19]. Also, a significant expansion in CD8+ antigen-specific T cell clones against one or more of tumor-associated antigens MAGE-1, gp100, and HER-2 was identified by vaccination with DC pulsed with tumor cell lysate in patients with malignant glioma [20]. Therefore, the tumor cell lysate-pulsed DC should induce CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells, which is not usually achieved by a single, defined CTL epitope. In addition, a tumor cell lysate as a source of an antigen should reduce the ability of a tumor to escape immune recognition when vaccinating with a limited repertoire of tumor antigens [21]. In addition, they can be used without the prior knowledge of the patient’s MHC haplotype. A tumor cell lysate priming strategy has been used in a wide variety of tumor types, including melanoma [22], glioma [23], and renal cell carcinoma [24]. Yamanaka et al. reported that therapeutic vaccination with autologous tumor cell lysate-pulsed DC elicited systemic cytotoxicity detected by IFN-γ expression in response to tumor cell lysate, and intratumoral cytotoxic T cell infiltration in several patients. Yu et al. also reported prolonged median survival of 133 weeks in eight glioblastoma patients who received dendritic cell therapy [20, 25]. The results from these studies suggest that DC pulsed with a tumor cell lysate may be feasible and applicable to cancer immunotherapy.

Several cytokines are also used to cancer immunotherapy to enhance the induction of the anti-tumor immune responses [26, 27]. Among these cytokines, interlukin-12 (IL-12) has been implicated as a central component of the cellular immune response, highlighting the key role of this cytokine in bridging the innate and specific immune responses by activating NK cells, promoting CTL maturation, and biasing the CD4+ T cells toward Th1 differentiation [28]. Therefore, the incorporation of IL-12 or IL-12 inducing agents into a vaccine is expected to enhance the anti-tumor immunity and CTL induction. It has recently been reported that administration of IL-12 following the GL261 RNA-pulsed DC vaccine significantly enhanced the DC vaccine efficacy resulting in complete protection against glioma growth [29]. However, the systemic administration of IL-12 caused significant toxicity in human trials, and RNA is not easy to use on account of its low stability. An alternative approach is to deliver gene-modified DC that is transduced in vitro with the IL-12 gene. Recently, DC engineered to express murine IL-12 and pulsed with a tumor lysate induces specific T cell responses and anti-tumor immunity against a mouse prostate cancer model [30], which suggests that adenovirus-mediated IL-12 gene transduction enhanced the immune responses.

In this study, we demonstrated that vaccination with DC engineered to express IL-12 by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer and pulsed with GL26 tumor cell lysate (AdVIL-12/DC+GL26) enhanced tumor-specific CTL activity and anti-tumor immunity in GL26 glioma models.

Materials and methods

Animals and cell culture

Female mice C57BL/6(H-2 Kb) aged 6–8 weeks were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). A murine (C57BL/6) glioma cell line, GL26, was obtained from Dr John S Yu (Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA). GL26 glioma known as a highly tumorigenic cell in syngenic C57BL/6 mice is an analogue to the GL261 cell line [31]. The CT26 (H-2d) murine colon adenocarcinoma cell line, the EL-4 lymphoma cell line (H-2b) and the YAC-1 lymphoma cell line (H-2a) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA). The cells were used as the control target in the CTL assay. The cell lines were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heated-inactivated FBS, 10 mM Hepes, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine and 5×10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol.

Antibodies

The bone marrow DC surfaces or effector phenotype were characterized by their unique expression of several cell surface associated markers using fluorescently-labeled monoclonal antibodies and quantified on FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cells were stained with the following Abs (PharMingen, San Diego, CA): CD3(145–2C11), CD4(GK1.5), CD8a(53–6.7), CD11b(M1/70), CD11c(HL3), CD14(rmC5–3), CD19(1D3), CD40(HM40–3), CD54(3E20), CD80(16–10A1), CD86(GL1), MHC-class I(SF-1.1), MHC-class II(2G9) and NK-1.1(PK136).

Generation of DC from bone marrow

The primary bone marrow DC was obtained from a mouse bone marrow precursor according to the protocol reported elsewhere [32]. Briefly, the bone marrow was obtained from the tibia and femurs by flushing them with the media. The tissue pieces were minced into a single-cell suspension through a nylon mesh. The erythrocytes were then lysed by resuspending a cell pellet in a hypotonic buffer (9.84 g/l NH4Cl, 1 g/l KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA). The cells were washed twice in serum free RPMI-1640 medium and cultured on a 24 well plate at 1×106 cells/well containing RPMI 1640 medium with 20 ng/ml recombinant murine GM-CSF and 20 ng/ml recombinant murine IL-4 (Endogene, Woburn, MA, USA). On day 7, the non-adherent cells obtained from these cultures were considered to be bone marrow-derived DC. FACScan confirmed the phenotypic markers of DC.

Recombinant adenovirus vector

The recombinant adenoviruses IL-12 (AdVIL-12) encoding the murine IL-12 gene were a kind gift from Dr. Y. C. Sung (Pohang University of Science and Technology, Pohang, Korea). These recombinant adenoviruses were propagated in 293 cells and purified on a CsCl density gradient. Their titers were determined using a plaque assay on 293 cells. The aliquots of the adenovirus solutions were stored at −80°C.

Adenoviral transduction of DC

The DC generated on day 8 were plated at 2×106 cells/well in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS with AdVIL-12 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. After a 2 h incubation at 37°C under 5% CO2 with gentle agitation every 20 min, the BMDC culture medium was replaced with 2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, and the cells incubated for another 48 h at 37°C. The AdVIL-12 transduced DC (AdVIL-12/DC) was harvested, washed twice with PBS, and used for the tumor cell lysate pulsing in vitro.

Secretion of IL-12 by AdVIL-12

1×106 DC was infected with AdVIL-12 at different MOI. After 2 h, the viral supernatant was replaced with the cell culture medium. Forty-eight hours later, the supernatant was collected and tested for mIL-12 by ELISA (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

Bioactivity AdVIL-12/DC in vitro

Splenocytes were harvested from naïve mice, passed through a nylon mesh in order to remove the fibrous tissue, and the RBC were lysed using hypotonic buffer. These cells were resuspended in supernatants recovered from the AdVIL-12/DC, as described above. After 48 h, supernatants of the cultured splenocytes were assayed by ELISA for IFN-γ (Pierce).

Preparation of tumor cell lysates

The tumor cell lysate was prepared from the tumor cell line according to a method reported elsewhere [15]. Briefly, confluent cultures of the GL 26 cell line were incubated with a Trypsin/EDTA solution for 10 min, harvested, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended at a density of 1×107 cells/ml in serum-free medium. The cell suspension was frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then thawed in a 37°C water bath. The freeze/thaw cycle was repeated four times in rapid succession. The larger particles were removed by centrifugation at 600 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was passed through a 0.2 μm filter and an aliquot was stored at −80°C. The protein concentration of the lysate was determined using a commercial assay (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany).

DC vaccination and CTL induction

For tumor cell lysate pulsing, 1×106 of the mock-DC or AdVIL-12/DC was incubated with a lysate of the GL 26 cell line at a final concentration of 100 μg of protein/ml for 12 h at 37°C for protein processing. In order to induce the primary CTL in vivo, the AdVIL12-transduced DC (1×106 cells), which were pulsed with the GL26 tumor cell lysate (AdVIL-12/DC+GL26), generated and treated as above, were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into syngeneic mice at day 0. The control groups were injected either the GL 26 tumor cell lysate-pulsed mock DC (DC+GL26), AdVIL-12/DC, DC or PBS. On day 7, the mice were given a booster vaccination using the same protocol as described above. On day 7 after the booster vaccination, the splenocytes were harvested, homogenized and RBC lysed with an ACK lysis buffer. The non-adherent splenocytes, from which most of the DC and macrophages and monocytes had been removed by adherence to plastic for 90 min, were used as the effector cells. These splenocytes (2×106) were then restimulated with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed 2×105 cells syngeneic GL 26 cells in 24 well culture plates. The cells were then cultured in the presence of 10 U/ml of IL-2 for 7 days at 37°C.

Cytotoxicity assay

The assay for the cell-mediated killing of the target cells was performed in vitro using a standard four-hour chromium assay at various effector/target ratios. Briefly, splenocytes were harvested from the 7 days restimulation cultures and used as the effector cells. The GL26, EL-4, CT26 or YAC-1 target cells were labeled with 100 μCi of [51Cr] sodium chromate/106 cell for 1 h, washed four times, and then added to each well in triplicate of 96-V-bottom well microtiter plates with various numbers of the effector cells. After incubation for 4 h at 37°C, 100 μl of the supernatant of each well was collected, and the radioactivity was counted using a gamma counter. The percentage specific lysis was calculated as described previously [14].

ELISPOT assay

An ELISPOT kit that was purchased from AID (Strassberg, Germany) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the restimulated splenocytes were seeded into a 96-well microplate coated with the anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody at a concentration of 1×105 cells/well in a cell culture medium. The tumor cell lysate-pulsed DC (1×105 cells/well) were added as a stimulus. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. After developing the spots, the reaction was quenched with distilled water, and the plates were inverted and allowed to dry overnight in the dark. The number of spots corresponding to the IFN-γ secreting cells was determined using an automatic AID-ELISPOT-Reader (Strassberg, Germany).

Tumor models

For the protective study in the s.c. tumor model, the mice were vaccinated s.c, with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in the right flanks on day −21, −14 and −7. The control groups of the mice were vaccinated with either DC+GL26, AdVIL-12/DC, DC or PBS. On day 7, the mice were challenged with 1×106 GL26 tumor cells in the shaved left flank and the survival of these mice was monitored. The tumor size was assessed twice a week and recorded as the tumor area (in mm3) by measuring the largest perpendicular diameters with a caliper. For a protective study in the i.c. tumor model, the mice were vaccinated with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 s.c. in the right flanks on days -21, −14 and −7. Fresh 1×104 GL26 cells were inoculated into the brain on day 0.

To prove subcutaneous (s.c.) therapeutic benefit in established tumors, mice were vaccinated s.c. with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 on day 5, 12 and 19 after subcutaneous inoculation of 1×106 GL26 cell. To prove intracranial (i.c.) therapeutic benefit in established tumors, mice were vaccinated s.c. with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 on day 5, 12 and 19 after intracranial inoculation of 1×104 GL26 cell.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as a mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using a Student’s t test, with the exception of the survival data, which was analyzed using the Kaplan and Meier test. Survival data were compared using a log-rank test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

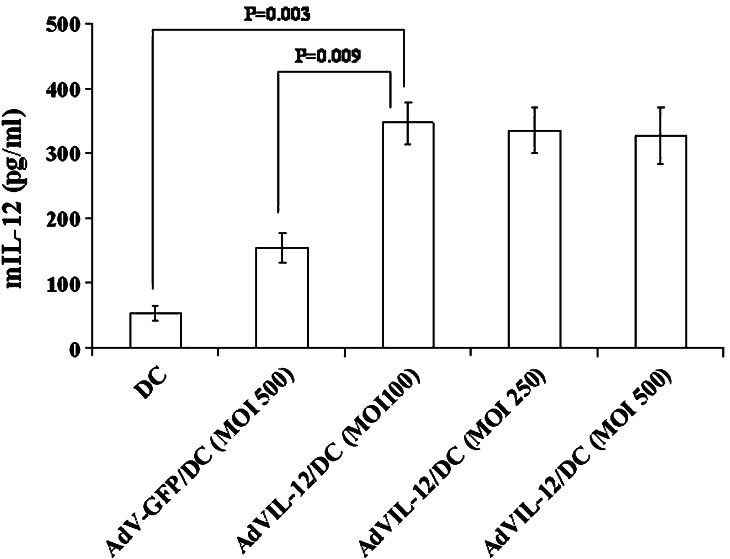

Secretion of IL-12 by transduced DC in vitro

The phenotypic profile of a representative population of bone marrow DC was first determined. These DC were expressed in moderate to high levels of the DC marker CD11c, high levels of MHC class I and MHC class II, moderate to high levels of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80, CD86, CD40, high levels of the adhesion molecule, CD54, and very low levels of CD3, CD19 and CD14 (data not shown). The concentration of the IL-12 released into the culture media 48 h after transduction was measured using ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1, the DC transfected with AdVIL12 at a MOI of 100 showed a significant increase in the IL-12 level above the mock-DC or AdV-GFP/DC (MOI of 500). The DC, when transduced with AdVIL-12 at an MOI of 100, was found to secrete 347 pg/ml/106 cell 48 h after infection. Accordingly, a MOI of 100 was selected for subsequent studies. The cell viability of AdVIL-12/DC 48 hours after the viral transduction (100 MOI) was 70% compared with mock-DC. In addition, the phenotypic changes within the DC induced by AdVIL-12 transduction were examined by phenotypic analysis. Expression levels of CD80, CD86 and MHC class II are enhanced in AdVIL-12/DC compared with the DC (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

IL-12 production by the DC transduced with AdVIL-12. The DC was transduced with various AdVIL-12 doses. Approximately 48 h later, ELISA was used to examine the level of IL-12 production in the DC supernatant. For statistical analysis, paired Student’s t test was performed. The data is representative of two independent experiments. The results are given as mean ± SD

Table 1.

Mean fluorescent intensity of cell surface markers

| Treatment | CD80 | CD86 | MHC class II |

|---|---|---|---|

| DC | 17 | 19 | 145 |

| AdVIL-12/DC | 237 | 172 | 452 |

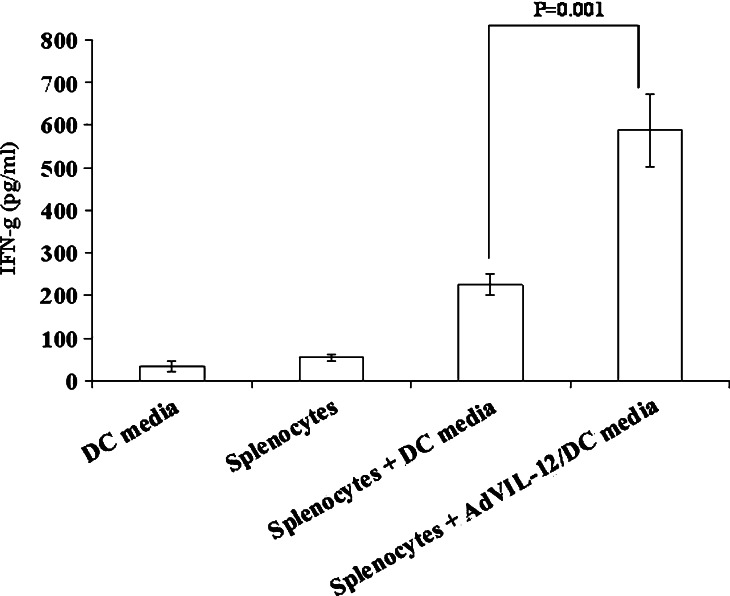

In order to determine if the supernatant of AdVIL-12/DC, which secreted measurable levels of IL-12, were also capable of inducing IFN-γ production, whole naïve splenocytes were incubated in the media from either the AdVIL-12/DC or mock-DC for 48 h, and ELISA measured the IFN-γ level. As shown in Fig. 2, The AdVIL-12/DC supernatant induced dramatic increases in the IFN-γ level compared with the splenocytes in the DC media. DC and splenocytes control measured just above the minimum sensitivity of the assay.

Fig. 2.

IFN-γ production by naïve splenocytes in vitro incubated with AdVIL-12/DC supernatants. Media from DC and AdVIL-12/DC was transferred to fresh naïve splenocytes for 48 h. Supernatants from splenocytes cultures were assayed by ELISA for IFN-γ. For statistical analysis, paired Student’s t test was performed. Data are representative of two independent experiments. The results are given as mean ± SD

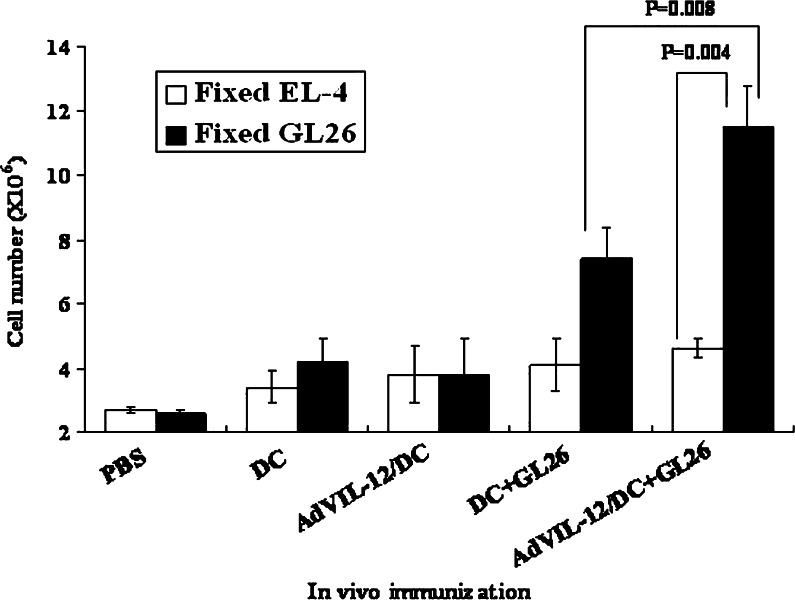

Enhancement of tumor-specific lymphocyte proliferation

Splenocytes from the animals vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 (2×106cells), DC+GL26, AdVIL-12/DC, DC, or PBS, respectively, were examined for their tumor-specific lymphocyte proliferative response. On day 7 after the booster vaccination, the splenocytes were restimulated in vitro for 7 days with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed 2×105 cells syngeneic GL 26 cells. As shown in Fig. 3, tumor-specific lymphocyte proliferative responses were observed when the splenocytes from mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26, and to lesser extent, DC+GL26. In contrast, no lymphocyte proliferative response was observed when the splenocytes were vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC, DC and PBS. Therefore, the vaccination of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 showed a significantly enhanced tumor-specific T cell response. In addition, the antigen specificity to the tumor cells was revealed using EL-4, which is an irrelevant tumor cell that failed to stimulate the lymphocyte from these mice (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

In vitro proliferation of lymphocyte in response to the tumor specific. GL26 tumor cell lysate-pulsed AdVIL-12/DC (1×106 cells), GL26 tumor cell lysate-pulsed DC, AdVIL-12 DC, DC, or PBS, respectively, were injected s.c. into the syngeneic mice. On day 7 after the booster vaccination, the splenocytes were harvested and restimulated with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed syngeneic GL 26 cells or 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed EL-4 for 7 days. The total number of cells obtained from each well was determined using a hemocytometer. For statistical analysis, paired Student’s t test was performed. The data is representative of two independent experiments, three mice each, carried out in triplicate. The results are given as mean ± SD

Phenotype of stimulated splenocytes in vitro

Flow cytometric analysis was performed to determine the phenotype of the population of the splenocytes induced from the vaccinated mice, as shown in Fig. 3. The Table 2 shows that the splenocytes induced by vaccination with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 consisted of 93.3% CD3+ cells, 56.6% CD8+ cells and 38.4% CD4+ cells. In contrast to the high proportion of CD8+ T cells in the CTL population, the control splenocytes induced by vaccination with the DC+GL26 consisted of 86.7% CD3+ cells, 38.7% CD8+ cells and 42.8% CD4+ cells.

Table 2.

Phenotype of the splenocytes induced from each vaccinated mice

| Immunization | CD3+ (%) | CD4+ (%) | CD8+ (%) | NK1.1+ (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | 52.1 | 26.8 | 27.6 | 3.9 |

| AdVIL-12/DC | 56.4 | 26.9 | 25.4 | 3.7 |

| DC+GL26 | 86.7 | 42.8 | 38.7 | 7.7 |

| AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 | 93.3 | 38.4 | 56.6 | 7.9 |

Splenocytes were restimulated with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed syngeneic GL26 cells for 7 days

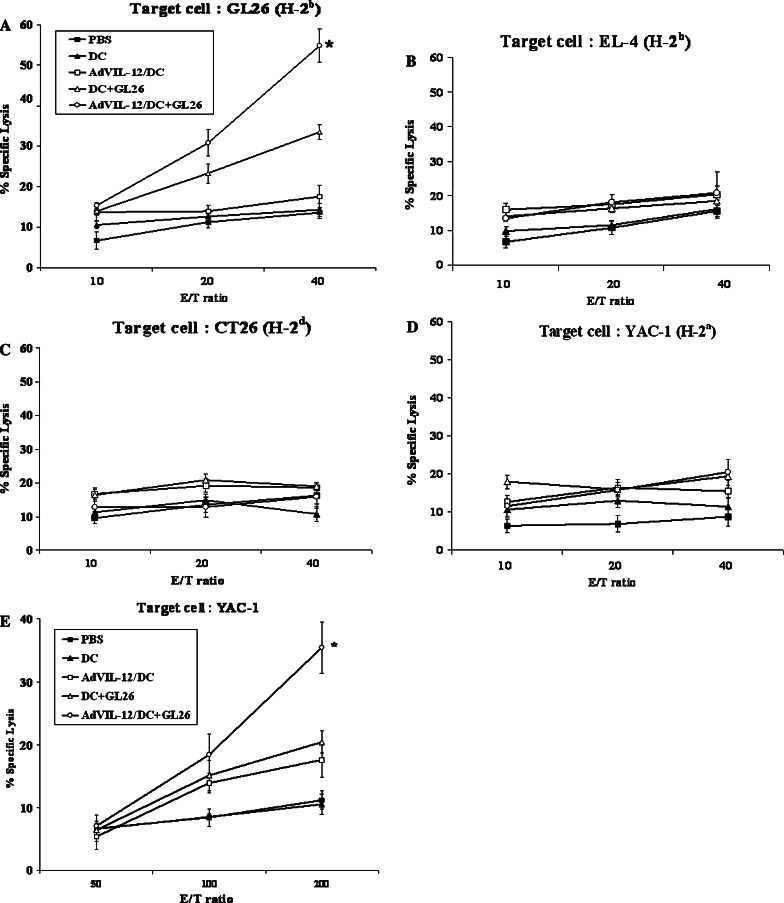

Enhancement of tumor-specific CTL responses

In order to determine if the effector cells from mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 could enhance the tumor-specific CTL responses in vivo, the effector cells from the mice which were immunized with either AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 (1×106cells), DC+GL26, AdVIL-12/DC, DC, or PBS, respectively and restimulated with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed syngeneic GL 26 cells, and examined for their cytotoxic activity on GL26 (H-2b), EL-4 (H-2b), CT26(H-2d) or YAC-1(H-2a) target cells. As shown in Fig. 4a, effector cells from the mice were vaccinated with the DC+GL26 induced killing responses of CTL against the syngeneic GL 26 target cells. Importantly, the effector cells from the mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 exhibited substantially enhanced CTL activity (54.8% specific lysis; E/T ratio=40) than those from the mice vaccinated with DC+GL26 (33.5% specific lysis; E/T ratio=40). In addition, these effector cells did not lyse the YAC-1 target cells (Fig. 4d), which suggests that the killing activity was not mediated by NK-cells. In fact, to test CTL activity, we used the E/T ratio of 10:1, 20:1 and 40:1. Therefore no CTL activity was observed against YAC-1 cells at this E/T ratio. Also, this CTL activity was immunologically specific, in that none of these cells exhibited cytotoxic activity against the irrelevant EL-4 (Fig. 4b) and MHC class-I mismatched CT26 (H-2d; Fig. 4c). No killing activity was observed in the effector cells from mice immunized with AdVIL-12/DC, DC, and PBS. This suggests that a DC+GL26 vaccination induced CTL activity of lymphocyte against the GL26 cells and AdVIL-12 enhanced CTL activity induced by vaccination with the GL26 tumor cell lysate-pulsed DC. In addition, the induction of the innate immune response was measured by examining the NK cell activity. As shown in Fig. 4e, the NK cell activity on the YAC-1 target cells from the mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 was considerably higher than in either the control or in the other immunization groups. Furthermore, the serum obtained from the mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 produced substantially more IFN-γ than from the mice vaccinated with the other control groups (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity of the CTL and NK cells resulting from the vaccinated mice. a–d The splenocytes were harvested from the mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 (1×106 cells), DC+GL26, AdVIL-12/DC, DC, or PBS, respectively, (see Materials and methods). The effector cells were generated by co-cultivation of these splenocytes with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed syngeneic GL 26 cells for 7 days. The target cells (GL26, EL-4, CT26 or YAC-1) were labeled with 51Cr and incubated with the effector cells at the ratios indicated. e The NK activity was assessed by measuring the lysis of the target YAC-1 cells mediated by splenocytes from the vaccinated mice and control mice. The splenocytes used for determining NK activity against YAC-1 cells, were not restimulated with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed syngeneic GL 26 cells. The data is representative of two independent experiments, containing three mice each, carried out in triplicate. The results are reported as a mean ± SD *Statistically significant at P<0.05 using the paired Student’s t test compared to all other groups

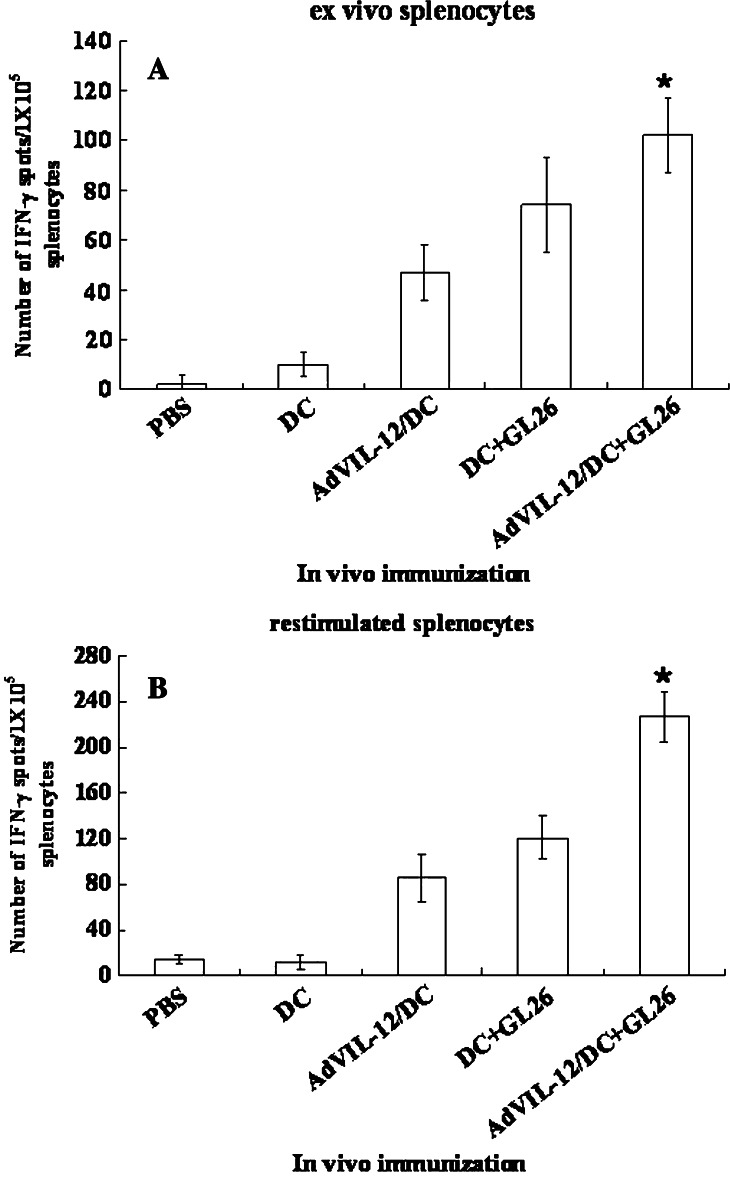

IFN-γ ELISPOT

As described in Fig. 4a, the presence of tumor-specific CTL was also studied using an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay in the splenocytes from the vaccinated mice, because the CTL produce Th1 cytokine IFN-γ in an antigen-specific manner. One week after the final vaccination, the splenocytes were harvested and the IFN-γ secreting T cells were quantified, either immediately (ex vivo effector cells) or after 7 days of restimulation with the syngeneic GL 26 cells, by ELISPOT. As shown in Fig. 5a and b, both the ex vivo effector splenocytes (Fig. 5a) and restimulated memory splenocytes (Fig. 5b) from the mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 showed significantly higher numbers of IFN-γ producing T cells than the splenocytes from the mice vaccinated with the DC+GL26. In contrast, the IFN-γ production level in the effector cells of the mice vaccinated with DC or PBS was negligible. This suggests that a vaccination with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 enhanced the Th1 immune response to syngeneic tumor cells.

Fig. 5.

AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 enhanced the effector and memory T cell responses. A and B, IFN-γ secreting splenocytes from the mice vaccinated, as described in Fig 3, were measured using an ELISPOT assay either ex vivo (a), or after restimulation for 7 days in vitro with 4% paraformaldehyde pre-fixed syngeneic GL 26 cells (b). The results are representative of two separate experiments, and are given as a mean ± SD. *Statistically significant at P<0.05 using a paired Student’s t test compared with all other groups

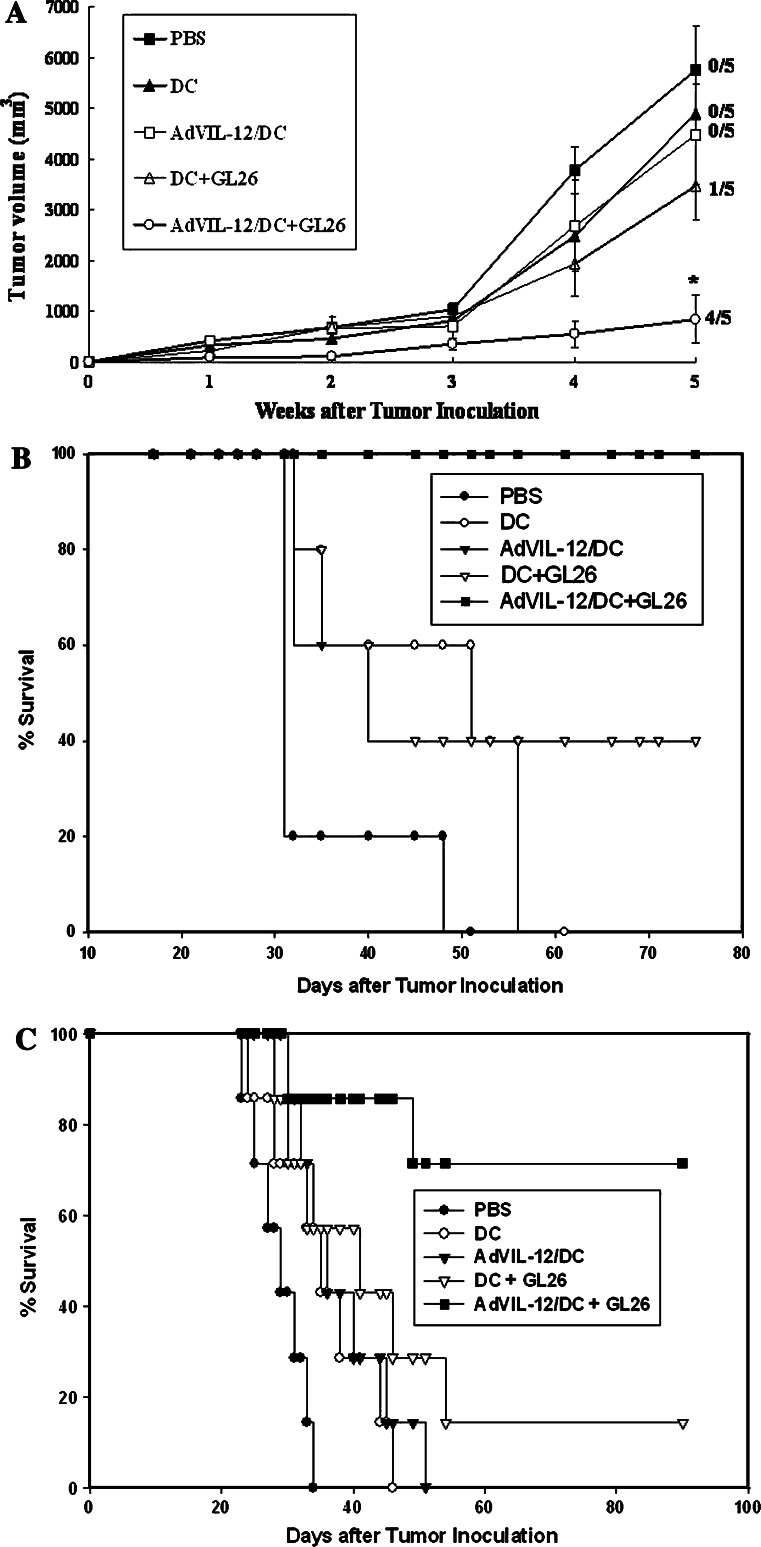

Anti-tumor immunity in protective models

As a result of the superior tumor-specific CTL induced by the AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 vaccination, this study examined whether or not AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 increases the protective potential on subcutaneous (s.c.) GL26 tumor challenged mice. The s.c. AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 vaccination was performed on day −21, −14, and −7 prior to s.c. inoculation of the GL26 cells. One week after the final vaccination, the mice were challenged with s.c. inoculation of the GL26 tumor cells. As shown in Fig. 6a, b, the mice immunized with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 showed significantly retarded tumor growth and prolonged survival compared with the control or other vaccination groups. Vaccination with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 completely protected the tumor growth and resulted in healthy survival in all the mice during the 75-day observation period (Fig. 6b). The mice vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26, DC+GL26 and AdVIL-12/DC showed 100%, and 40% survival rate, respectively, compared with the mice vaccinated with either DC (0%) or PBS (0%).

Fig. 6.

Protective effect of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in a subcutaneous and intracranial GL26 tumor model. The C57BL/6 naive mice were vaccinated with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 (1×106 cell injected on day -21, -14 and -7) and challenged in the opposite flank (on day 0) with 1×106 of the GL26 tumor cells. The tumor size (a) and survival times (b) of each group of mice were monitored. Each group consisted of five mice. *Statistically significant at P<0.05 using Student’s t test compared with all other groups. The survival advantage conferred by the tumor cell lysate-pulsed AdVIL-12/DC was statistically significant compared with either of the control groups (Kaplan–Meier, P<0.05). In the data presented in (a), the significance of differences in the tumor size at 5 weeks (Student’s t test); AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 versus DC+GL26, P=0.0097 and numbers to the right indicate the number of mice complete tumor inhibition per total number of mice in each group. In the data presented in B, the significance of differences (log-rank test); AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 versus DC+GL26, P=0.012. c Protective effects of the intracranial (i.c.) inoculation of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in a mouse brain tumor model. The mice were given s.c. vaccination of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 three times at a 7 day interval. One week after the final vaccination, the mice were challenged i.c, with 104 of the GL26 tumor cells. Each group consisted of seven mice. The survival advantage conferred by the tumor cell lysate-pulsed AdVIL-12/DC was statistically significant compared with either of the control groups (Kaplan–Meier, P<0.05); AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 versus DC+GL26, P=0.021

In order to determine the protective immunity against the i.c. growth of glioma, the mice were given s.c. vaccination of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in a same fashion prior to i.c. inoculation of GL26 tumor cells. As shown in Fig. 6c, 5 (71%) of the 7 animals vaccinated with the AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 survived more than 90 days after the tumor inoculation. In contrast, no mice in each of the control groups survived for the same time.

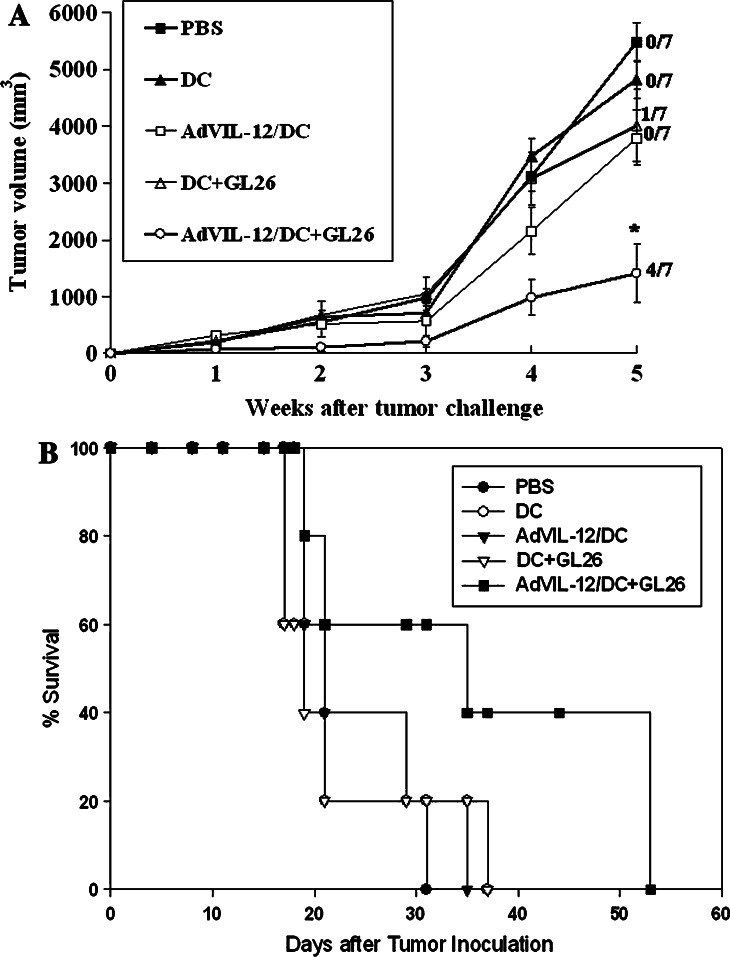

Anti-tumor immunity in therapeutic models

The therapeutic efficacy of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 vaccination was next tested in the s.c. tumor model and i.c. tumor model. The mice were vaccinated s.c. with 1×106 AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 on day 5, 12 and 19 after the inoculation of s.c. (1×106) or i.c. (1×104) GL26 tumor cells, respectively, and then observed for tumor growth and survival.

In the s.c. therapeutic studies, similar to the results from the subcutaneous protective setting, vaccination with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 demonstrated complete tumor rejection in four of seven mice and the tumor growth was significantly inhibited in the remaining three mice compared with that seen in the mice immunized with the other control groups (Fig. 7a). Intracranial (i.c.) therapy with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 appeared to induce the prolongation of survival compared to other control groups, but this did not achieve statistical significant (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Therapeutic effect of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in a subcutaneous and intracranial GL26 tumor-bearing model. a C57BL/6 naive mice were inoculated in the s.c. With 1×106 GL26 tumor cells on day 0 and subsequently immunized in the opposite flanks with 1×106 AdVIL-12/ DC+GL26 at weekly interval X 3 at day 5 after tumor inoculation. Numbers to the right indicate the number of mice completing tumor inhibition per total number of mice in each group. Each group consisted of seven mice. *Statistically significant at P<0.05 using Student’s t test compared with all other groups. The significance of differences in the tumor size at 5 weeks (Student’s t test); AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 versus DC+GL26, P=0.018. b Therapeutic effects of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 in the intracranial tumor-bearing model. Mice were vaccinated s.c with 1×106 AdVIL-12/ DC+GL26 on day 5, 12 and 19 after 1×104 tumor cell inoculation. Each group consisted of five mice. The significance of differences (log-rank test); AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 versus DC+GL26, P=0.067. The survival advantage conferred by the tumor cell lysate-pulsed AdVIL-12/DC was statistically significant compared with either of the control groups (Kaplan–Meier, P<0.05)

Discussion

In this study, we firstly evaluated the in vitro IL-12 expression and phenotypes of the DC transduced with AdVIL-12 at different MOI. The DC transduced with AdVIL-12 at an MOI of 100 showed limited toxicity and maximal production of IL-12 however, an MOI dose could not improve the production level when it reaches more than MOI of 100 (Fig. 1). Because adenovirus itself induces DC maturation [33], DC transduced with AdV-GFP also leads to transient production of IL-12. In addition, the maturation of DC was observed in the DC transduced with an adenovirus vector expressing the Rel homology domain of NFkB [34]. It was found that the adenoviral vector affected the DC phenotype in these experimental systems (Table 1). Recently, Saika et al. [30] reported that the DC transduced AdVIL-12 showed increased levels of the costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86), MHC-class II antigen, compared with the non-transduced DC.

It was observed that the supernatant from the AdVIL-12/DC induced appreciable increases in the IFN-γ level in the naïve splenocytes in culture (Fig 2). These results suggest that the DC produce IL-12 and can promote the development of IFN-γ secreting Th1 T cells. Furthermore, the vaccination of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 can induce a more efficient proliferation of tumor-specific T cell responses in vitro (Fig 3), which consisted of a high proportion CD8+ cells (Table 2). Vegh et al. [35] reported that the tumor cell lysate-loaded cytokine-pretreated DC exhibited an enhanced Th1/Th2 and CTL response, which is essential for achieving an effective, specific anti-tumor response. Splenocytes from the mice vaccinated with the AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 showed enhanced tumor-specific CTL activity and innate immune response by 51Cr release assay (Fig 4a, e) and increased numbers of IFN-γ ?secreting T cells by ELISPOT assay (Fig. 5a, b).

In the in vivo experiment, we s.c. injected DCs in mice with s.c. tumor for easier and more precise monitoring of anti-tumor immunity and tumor volume. We also test whether s.c. injection of DCs in mice with i.c. tumor, can induce anti-tumor responses in brain. Vaccination with AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 showed a potent tumor growth inhibition and a survival benefit in both protection models (Fig 6a,b, c) and therapeutic models (Fig. 7a). From these results, we speculate that injected AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 migrated to lymph nodes leading to growth and prolongation of survival in both the protective model and the therapeutic model. And, we also speculate that AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 migrated to the lymph nodes may activate specific CTL which infiltrate through the blood brain barrier (BBB) to the inflamed brain tumor tissue, resulting in the induction of anti-tumor immunity against brain tumor. However, anti-tumor effect of AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 vaccination did not achieve statistical significance in the therapeutic models inoculated with i.c. GL 26 tumor model (Fig. 7b). Even though the reason for its lower anti-tumor efficacy in this type of experimental models is uncertain, the enhanced anti-tumor activity by the AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 vaccination might be overwhelmed by the very rapid growing rate of the GL26 tumor, limited intracranial space and early neurologic deficit, and immune-barrier environment. In addition to these factors, we consider various optimizations of vaccination protocols including the vaccination timing and scheduling, DC doses, the number of vaccination, and the administration route to improve the in vivo effect of this vaccination strategy.

Taken together, these results suggest that the AdVIL-12/DC+GL26 immunized mice received the full benefit of both the tumor antigen loading as well as DC activation, which increased the in vivo anti-tumor effect of DC-based vaccination. This is consistent with a report showing that immunization with adenovirus-infected DC pulsed with the tumor antigen offered protection against flank tumors in mice and induced a memory immune response [36].

A previous report by Zitvogel et al. [37] indicated that the anti-tumor effect of DC-based vaccination is dependent on the production of the Th1-type immunostimulatory cytokine such as IFN-γ, IL-12. Therefore, the level of IFN-γ production as a result of IL-12 may have an important role in the increased anti-tumor immune responses in vivo.

In conclusion, vaccination with DC engineered to express IL-12 by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer and pulsed with a tumor cell lysate enhances tumor-specific CTL and Th1 immune response and could be developed as an alternative DC-based vaccine strategy against a malignant brain tumors.

Footnotes

Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2004-005-E00001).

References

- 1.Nazzaro JM, Neuwelt EA. The role of surgery in the management of supratentorial intermediate and high-grade astrocytomas in adults. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:331. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.3.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surawicz TS, Davis F, Freels S, Laws ER, Jr, Menck HR. Brain tumor survival: results from the National Cancer Data Base. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:151. doi: 10.1023/A:1006091608586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes RL, Koslow M, Hiesiger EM, Hymes KB, Hochster HS, Moore EJ, Pierz DM, Chen DK, Budzilovich GN, Ransohoff J. Improved long term survival after intracavitary interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells for adults with recurrent malignant glioma. Cancer. 1995;76:840. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950901)76:5<840::AID-CNCR2820760519>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehtesham M, Kabos P, Gutierrez MA, Samoto K, Black KL, Yu JS. Intratumoral dendritic cell vaccination elicits potent tumoricidal immunity against malignant glioma in rats. J Immunother. 2003;26:107. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsuboi K, Saijo K, Ishikawa E, Tsurushima H, Takano S, Morishita Y, Ohno T. Effects of local injection of ex vivo expanded autologous tumor-specific T lymphocyte in cases with recurrent malignant gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishikawa E, Tsuboi K, Takano S, Uchimura E, Nose T, Ohno T. Intratumoral injection of IL-2-activated NK cells enhances the antitumor effect of intradermally injected paraformaldehyde-fixed tumor vaccine in a rat intracranial brain tumor model. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:98. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jean WC, Spellman SR, Wallenfriedman MA, Flores CT, Kurtz BP, Hall WA, Low WC. Effects of combined granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin-2, and interleukin-12 based immunotherapy against intracranial glioma in the rat. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:39. doi: 10.1023/B:NEON.0000013477.94568.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steinman R. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoh J, Lee YB, Kim SU. T cell costimulatory molecules B7–1 (CD80) and B7–2 (CD86) are expressed in human microglia but not in astrocytes in culture. Brain Res. 1995;704:92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Witham TF, Erff ML, Okada H, Chambers WH, Pollack IF. 7-Hydroxystaurosporine-induced apoptosis in 9L glioma cells provides an effective antigen source for dendritic cells and yields a potent vaccine strategy in an intracranial glioma model. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1327. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200206000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutta T, Spence A, Lampson LA. Robust ability of IFN-gamma to upregulate class II MHC antigen expression in tumor bearing rat brains. J Neurooncol. 2003;64:31. doi: 10.1007/BF02700018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada H, Tsugawa T, Sato H, Kuwashima N, Gambotto A, Okada K, Dusak JE, Fellows-Mayle WK, Papworth GD, Watkins SC, Chambers WH, Potter DM, Storkus WJ, Pollack IF. Delivery of interferon-alpha transfected dendritic cells into central nervous system tumors enhances the antitumor efficacy of peripheral peptide-based vaccines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5830. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho HI, Kim HJ, Oh ST, Kim TG. In vitro induction of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte by dendritic cells transduced with recombinant adenoviruses. Vaccine. 2003;22:224. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00569-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert LA, Gibson GR, Maloney M, Durell B, Noelle RJ, Barth RJ., Jr Intranodal immunization with tumor cell lysate-pulsed dendritic cells enhances protective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Candido KA, Shimizu K, McLaughlin JC, Kunkel R, Fuller JA, Redman BG, Thomas EK, Nickoloff BJ, Mule JJ. Local administration of dendritic cells inhibits established breast tumor growth: implications for apoptosis-inducing agents. Cancer Res. 2001;61:228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godelaine D, Carrasco J, Lucas S, Karanikas V, Schuler-Thurner B, Coulie PG, Schuler G, Boon T, Van Pel A. Polyclonal CTL responses observed in melanoma patients vaccinated with dendritic cells pulsed with a MAGE-3.A1 peptide. J Immunol. 2003;171:4893. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu BY, Chen XH, Gu QL, Li JF, Yin HR, Zhu ZG, Lin YZ. Antitumor effects of vaccine consisting of dendritic cells pulsed with tumor RNA from gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:630. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang AE, Redman BG, Whitfield JR, Nickoloff BJ, Braun TM, Lee PP, Geiger JD, Mule JJ. A phase I trial of tumor cell lysate-pulsed dendritic cells in the treatment of advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu JS, Liu G, Ying H, Yong WH, Black KL, Wheeler CJ. Vaccination with tumor cell lysate-pulsed dendritic cells elicits antigen-specific, cytotoxic T-cells in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4973. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones VE, Mitchell MS. Therapeutic vaccines for melanoma: progress and problems. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:349. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(96)10045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimizu K, Thomas EK, Giedlin M, Mule JJ. Enhancement of tumor cell lysate- and peptide-pulsed dendritic cell-based vaccines by the addition of foreign helper protein. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida S, Morii K, Watanabe M, Saito T, Yamamoto K, Tanaka R. The generation of anti-tumoral cells using dentritic cells from the peripheral blood of patients with malignant brain tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2001;50:321. doi: 10.1007/s002620100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurokawa T, Oelke M, Mackensen A. Induction and clonal expansion of tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte from renal cell carcinoma patients after stimulation with autologous dendritic cells loaded with tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:749. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::AID-IJC1141>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamanaka R, Abe T, Yajima N, Tsuchiya N, Homma J, Kobayashi T, Narita M, Takahashi M, Tanaka R. Vaccination of recurrent glioma patients with tumour lysate-pulsed dendritic cells elicits immune responses: results of a clinical phase I/II trial. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1172. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakahara N, Pollack IF, Storkus WJ, Wakabayashi T, Yoshida J, Okada H. Effective induction of antiglioma cytotoxic T cells by coadministration of interferon-beta gene vector and dendritic cells. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:549. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamanaka R, Tsuchiya N, Yajima N, Honma J, Hasegawa H, Tanaka R, Ramsey J, Blaese RM, Xanthopoulos KG. Induction of an antitumor immunological response by an intratumoral injection of dendritic cells pulsed with genetically engineered Semliki Forest virus to produce interleukin-18 combined with the systemic administration of interleukin-12. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:746. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.4.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macatonia SE, Hosken NA, Litton M, Vieira P, Hsieh CS, Culpepper JA, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Murphy KM, O’Garra A. Dendritic cells produce IL-12 and direct the development of Th1 cells from naive CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1995;154:5071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Insug O, Ku G, Ertl HC, Blaszczyk-Thurin M. A dendritic cell vaccine induces protective immunity to intracranial growth of glioma. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saika T, Satoh T, Kusaka N, Ebara S, Mouraviev VB, Timme TL, Thompson TC. Route of administration influences the antitumor effects of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells engineered to produce interleukin-12 in a metastatic mouse prostate cancer model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:317. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ausman JI, Shapiro WR, Rall DP. Studies on the chemotherapy of experimental brain tumors: development of an experimental model. Cancer Res. 1970;30:2394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman RM. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirschowitz EA, Weaver JD, Hidalgo GE, Doherty DE. Murine dendritic cells infected with adenovirus vectors show signs of activation. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1112. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morelli AE, Larregina AT, Ganster RW, Zahorchak AF, Plowey JM, Takayama T, Logar AJ, Robbins PD, Falo LD, Thomson AW. Recombinant adenovirus induces maturation of dendritic cells via a NF-kappaB-dependent pathway. J Virol. 2000;74:9617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.20.9617-9628.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vegh Z, Mazumder A. Generation of tumor cell lysate-loaded dendritic cells preprogrammed for IL-12 production and augmented T cell response. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:67. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0338-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller G, Lahrs S, Pillarisetty VG, Shah AB, DeMatteo RP. Adenovirus infection enhances dendritic cell immunostimulatory properties and induces natural killer and T-cell-mediated tumor protection. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zitvogel L, Mayordomo JI, Tjandrawan T, DeLeo AB, Clarke MR, Lotze MT, Storkus WJ. Therapy of murine tumors with tumor peptide-pulsed dendritic cells: dependence on T cells, B7 costimulation, and T helper cell 1-associated cytokines. J Exp Med. 1996;183:87. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]