Abstract

Therapeutic vaccination holds great potential as complementary treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Here, we report that a therapeutic whole cell vaccine formulated with IL-2 adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide as cytokine-depot formulation elicits potent antitumor immunity and induces delayed tumor growth, control of tumor dissemination and longer survival in mice challenged with A20-lymphoma. Therapeutic vaccination induced higher numbers of tumor’s infiltrating lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and NK cells), and the production of IFN-γ and IL-4 by intratumoral CD4+ T cells. Further, strong tumor antigen-specific cellular responses were detected at systemic level. Both the A20-derived antigenic material and the IL-2 depot formulation were required for induction of an effective immune response that impacted on cancer progression. All mice receiving any form of IL-2, either as part of the vaccine or alone as control, showed higher numbers of CD4+CD25+/highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) in the tumor, which might have a role in tumor progression in these animals. Nevertheless, for those animals that received the cytokine as part of the vaccine formulation, the overall effect was improved immune response and less disseminated disease, suggesting that therapeutic vaccination overcomes the potential detrimental effect of intratumoral Treg cells. Overall, the results presented here show that a simple vaccine formulation, that can be easily prepared under GMP conditions, is a promising strategy to be used in B-cell lymphoma and may have enough merit to be tested in clinical trials.

Keywords: Lymphoma, Vaccine, Interleukin-2, Aluminum hydroxide, Regulatory T cells

Introduction

Patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) respond well to treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but relapses are frequent after a period of months or years with loss of response to treatment. This highlights the need for new therapeutic modalities for these patients. Although therapeutic use of monoclonal antibodies, particularly anti-CD20, has changed significantly the treatment of patients with NHL [1], these diseases still represent a clinical challenge in cancer management. Around 60,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States each year and NHL ranks fifth overall in cancer incidence and mortality (http://www.cancer.gov).

A complementary approach for NHL treatment is active immunotherapy. Induction of tumor-specific adaptive immunity could prevent the relapse after conventional therapies in NHL patients, particularly in the context of minimal residual disease. Active immunotherapy with cancer vaccines could induce humoral and cellular immune responses and the development of immunological memory which may substantially reduce the relapse of the disease [2]. Vaccination has been shown to be effective even in the setting of B-cell depletion induced by rituximab treatment, suggesting that NHL vaccines can be complementary to monoclonal antibody therapy, leading to enhance clinical efficacy [2, 3]. A widely used approach for active immunotherapy in NHL is idiotype vaccination, which has been shown to induce antitumor immunity and clinical response. It has been assessed in several phase 1 and 2 clinical trials and a phase 3 trial is currently ongoing [4–7]. Overall, idiotype protein vaccination has shown benefit, but single protein autologous vaccine preparation is complex and may promote tumor escape.

Alternatively, whole cell vaccines are simple and fast to manufacture and can present different tumor-associated antigens. The use of cellular based vaccine provides an avenue for delivering a diverse repertoire of tumor antigens that include those that are known and unknown. One of the problems of this approach is that tumor antigen’s immunogenicity is relatively weak. Thus, the inclusion of an adjuvant is necessary to stimulate the immune system against tumor cells. Several studies have used different cytokines as adjuvant in vaccines [8].

IL-2 has been widely attempted and showed therapeutic effect in preclinical animal models [9–14] and cancer patients [15–17]. High-dose IL-2 for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Besides, IL-2 is also being used in some phase I clinical trials on lymphoma patients [2, 18–21].

Despite this extensive clinical testing, toxicity associated with systemic administration of large doses of cytokine is a major drawback for clinical application. To circumvent this problem, numerous attempts have been made to direct the activity of the cytokine to the tumor site, mainly by using viral or bacterial vectors for delivery of cytokines [8]. An alternative strategy is to use a system for slow release of the cytokine [20–23]. Aluminum compounds have been used for almost a century as human vaccine adjuvants and it is well known that they work by forming a depot at the site of injection from which adsorbed antigen are slowly released. A recent relevant finding was that aluminum hydroxide can also be used as depot material to which cytokines can be adsorbed for in vivo administration, with decreased toxicity [22]. This system has been evaluated in preclinical models of renal cell carcinoma and melanoma, showing that when IL-2 is administered adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide, much lower doses are required to obtain identical antitumoral effect, as compared with the use of non-adsorbed IL-2 [22].

In this study, we report that a therapeutic vaccine formulated as a whole cell lysate of lymphoma cells combined with IL-2 adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide as depot material, stimulates potent antitumor immunity that impacts on disease progression and survival in a reproducible syngeneic murine model of B-cell lymphoma. This approach may be a valuable strategy to promote local and systemic immunity against a larger number of antigens in B-cell lymphoma with therapeutic value as compared with idiotype vaccination.

Materials and methods

Animals and tumor cell line

Female BALB/c mice, 6–8 weeks old were used for in vivo experiments. All protocols for animal experimentation were carried out in accordance with procedures authorized by the University’s Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation, Uruguay, to whom this project was previously submitted.

A20, a BALB/c cell lymphoma line originally derived from a spontaneous reticulum cell neoplasm, was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Tumor cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented (cRPMI) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL, USA), 2 mM l-glutamine (Sigma), 0.05 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Vaccine preparation

Recombinant human IL-2 (rIL-2) adsorbed to aluminum hydroxide (Rehydragel) was manufactured by PCgen (Argentina), under good manufacturing practices (GMP) conditions and according with a pre-established protocol [22]. Whole cell lysates were prepared by ultrasonic disruption of A20 cells and mixed with the alum-adsorbed IL-2. The vaccine was formulated so as to include the lysate from 1 × 106 A20 cells combined with 1.6 × 105 IU of rIL-2 adsorbed in aluminum hydroxide per mouse dose.

Tumor challenge and therapeutic vaccination

A20 were grown in culture and harvested in log phase, washed and resuspended to a final concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml of RPMI-1640 (without supplements). Groups of mice were injected subcutaneously into the right flank with 1 × 106 cells and were monitored for tumor growth and survival. On days 3 and 7 post-tumor cells inoculation (p.t.i), mice received by subcutaneous injection in the opposite flank, one of the following preparations: whole A20 cell lysate adsorbed with alum combined with alum-adsorbed IL-2 (A20-IL-2); whole A20 cell lysate with alum (A20); alum-adsorbed IL-2 (IL-2-AL); IL-2 alone (IL-2) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as control. Tumors were measured every other day with a microcaliper in three dimensions, and tumor volumes were calculated as length × width × length × 0.5236, as previously described [24]. Mice were euthanized when tumors reached 4,000 mm3 or before if they showed sign of distress. These time points were defined as survival time.

Flow cytometry analysis

Analysis of tumor-infiltrating cells was conducted by flow cytometry on fine needle aspirates (FNAs) taken from tumors at days 20 and 39 p.t.i. Cells were immunostained with the following panel of antibodies: PECy5-conjugated anti-CD3, FITC-conjugated anti-CD4, APC-conjugated anti-CD4, PE-conjugated anti-CD8, FITC-conjugated anti-CD25, PE-conjugated anti-Foxp3 and FITC-conjugated anti-CD49b (all reagents from BD Pharmingen, San Diego, USA). Optimal antibody concentrations were previously defined by titration. For intracellular Foxp3 staining, cells were first stained for CD4 and CD25, then fixed and permeabilized with mouse Foxp3 buffer set (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Cells were washed twice with permeabilization buffer and then incubated with anti-mouse Foxp3 at room temperature for 30 min in the dark, before being resuspended in PBS and analyzed. Flow cytometry data was collected on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer equipped with two lasers (Becton–Dickinson, Oxford, UK). For data acquisition and analysis CellQuest software (Becton–Dickinson) was used.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Tumors were removed from mice at day 26 p.t.i, prepared as a single-cell suspension, pooled within groups and stimulated in 24-well plates with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (50 ng/ml; Sigma) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml; Sigma) in the presence of brefeldin A (10 μg/ml; GolgiPlug; Becton–Dickinson) for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were then harvested, stained with antibodies to surface markers (anti-CD3 and anti-CD4) for 30 min, then fixed for 20 min with 2% paraformaldehyde/PBS and stored at 4°C overnight. Next day fixed cells were permeabilized with saponin buffer and stained with cytokine-specific antibodies (PE-conjugated anti-IFN-γ or PE-conjugated anti-IL-4) at 4°C for 30 min. Samples were analyzed with a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton–Dickinson). A gate was set within the lymphocyte population in the FSC–SSC dot-plot and 10,000 events were collected.

Proliferation assays

Spleens were removed from mice at 26 and 40 days p.t.i and prepared as a single-cell suspension. Splenocytes were labeled with 3 μM carboxy-fluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE), washed three times in cRPMI, counted, and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. CFSE labeled cells were seeded in duplicates into 24-well plates (Nunc, Naperville, IL) at 2 × 106 cells per well in 2 ml of cRPMI with 100 μg/ml penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma). Cells were incubated for 5 days with one of the following: 1 mg/ml of concanavalin A (Con A), 1 × 105 irradiated A20 cells or left without stimuli. After the incubation cells were harvested and labeled with propidium iodide (PI) for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. Cell proliferation was estimated by flow cytometry. FACS data were collected as listmode files and were analyzed using the Proliferation Wizard module of the ModFit software package (Verity Software House, Inc). The standard options were chosen to perform analysis on the gated live lymphocyte population based on FSC and FL-2 profiles. The generation number within the proliferation wizard module was set at 9. The parent generation within the same module was set as the median fluorescence intensity using an unstimulated control sample [25].

Cytokine production by spleen cells

The in vitro production of cytokines was evaluated in supernatants collected from cultures from the proliferation assays conducted with cells obtained at day 40 p.t.i. IFN-γ, IL-6 and TNF-α concentration in the samples were determined by using BDTM cytometric bead array (CBA) mouse cytokine kit (BD Biosciences, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Data acquisition and analysis were carried out on a flow cytometric platform using BDTM CBA software. IL-17A production was determined in the same supernatant using an ELISA kit (e-Bioscience, USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocols.

Statistical analysis

Differences in survival times were determined using Kaplan–Meier and log-rank test. For the in vitro assays, the statistical significance of differences between study groups was analyzed using ANOVA. Proportions of mice with disseminated lymphoma were compared for their difference using the Chi-square test with Yates correction. A value of P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Therapeutic A20-IL-2 vaccination prolongs survival time and reduces tumor dissemination

Groups of mice (n = 10 per group) were inoculated with A20 cells and then treated on days 3 and 7 p.t.i with A20-IL-2, A20, IL-2-AL, IL-2 or PBS as described in “Materials and methods”. As shown in Fig. 1a, therapeutic administration of A20-IL-2 significantly prolonged the survival time on these mice, as compared with mice vaccinated with A20, IL-2 alone or PBS (log rank, P = 0.0001). Differences in survival curves were paralleled by differences in tumor growth kinetics (data not shown). Mice receiving IL-2-AL showed extended survival although to less extent than those receiving A20-IL-2. Nevertheless, Fig. 1a also shows that IL-2 adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide performed better than non-adsorbed IL-2, thus only IL-2-AL was used for further experiments.

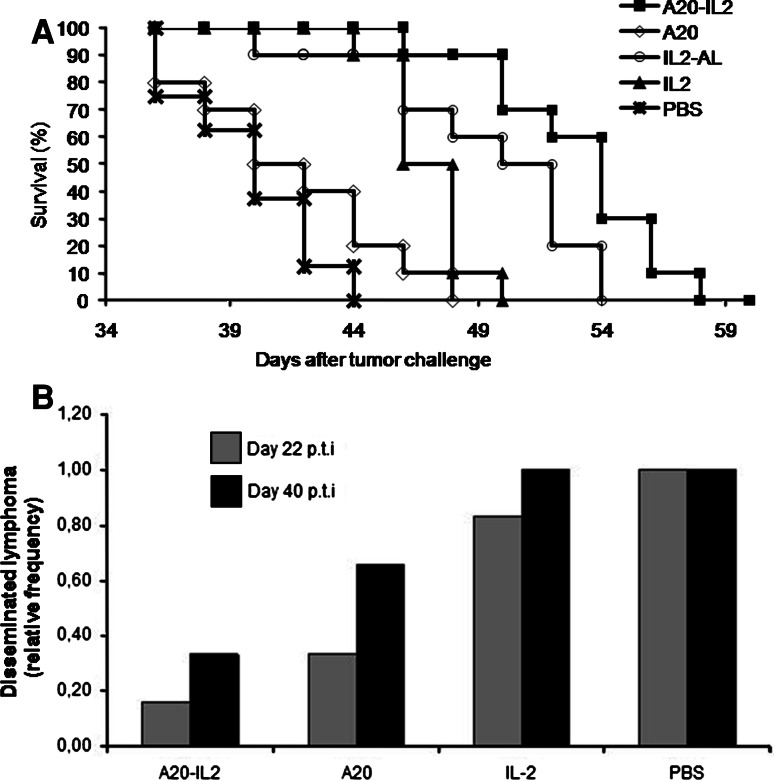

Fig. 1.

Disease progression and survival among the different groups. a Kaplan–Meier plot of mice survival post-tumor challenge (log rank, P = 0.0001). b Groups of mice vaccinated with any of the different preparations were euthanized at days 22 and 40 p.t.i and necropsies were performed to evaluated disease progression. Grey bars represents mice with disseminated lymphoma at day 22 p.t.i (P = 0.009), and black bars represents mice with disseminated lymphoma at day 40. Data shown are given as relative frequencies

In another experiment, 10 mice per group were inoculated with A20 cells and then treated on days 3 and 7 p.t.i as described before with either A20-IL-2, A20, IL-2-AL, or PBS. At days 22 and 40 p.t.i three mice per group were euthanized and necropsies were performed to evaluate disease progression and the presence of metastases. We defined disease progression as localized lymphoma when the primary tumor has only macroscopic metastasis at the draining lymph nodes and as disseminated lymphoma when there was also involvement of other lymph nodes or organs. As shown in Fig. 1b, the progression of the disease differed among the groups at both time points evaluated. The percentages of mice with disseminated lymphoma were high in the groups treated with IL-2-AL or that remained non-treated, and by day 40 p.t.i all mice from these groups showed disseminated lymphoma. On the contrary, lymphoma dissemination was markedly reduced in the group receiving A20-IL-2, i.e., by day 22 p.t.i only 17% of mice with disseminated lymphoma as compared with 33, 83 and 100% in A20, IL-2-AL and PBS groups, respectively (P = 0.009). Mice receiving A20 alone also showed lower occurrence of metastases although to less extent than those receiving the A20-IL-2 vaccine (Fig. 1b).

Overall, these results show that only the combination treatment with A20 cells and IL-2-AL can delay disease dissemination and prolong the survival of lymphoma-bearing mice.

A20-IL-2 depot formulation elicits local and systemic antitumoral immune responses

The immune response induced by the therapeutic vaccination was evaluated at local and systemic level by assessing cell recruitment and profile of cytokine expression in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes as well as by proliferation and cytokine expression assays in splenocytes.

The percentage of intratumoral CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells and NK cells were increased in mice receiving therapeutic vaccination with A20-IL-2

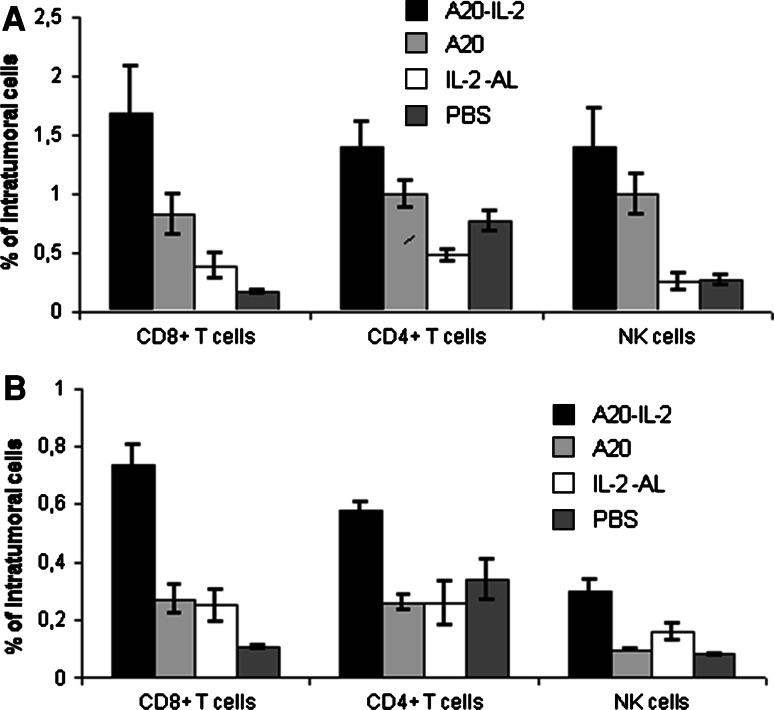

The recruitment of lymphocytes to the tumor site was assessed on FNAs taken from tumors at days 20 and 39 p.t.i. As shown in Fig. 2, a marked increase in the number of tumor-infiltrating CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells and NK cells was observed in FNAs obtained from mice receiving the A20-IL-2 combination treatment at both days evaluated. By day 20, we observed a tenfold increase in the number of CD8+ T cells (ANOVA, P = 0.001), a twofold increase of CD4+ T cells (ANOVA, P = 0.0001) and a fivefold increase of NK cells (ANOVA, P = 0.001) in this group as compared with the PBS control group. Results were similar on sample taken at day 39 p.t.i. The group of mice receiving A20 alone as therapeutic vaccine, showed a transient augmentation of CD8+ T cells and NK cells by day 20 p.t.i that was no longer significant by day 39 p.t.i. Mice receiving IL-2-AL showed higher numbers of intratumoral CD8+ T cells and NK cells at day 39 p.t.i as compared with the PBS control group, although the statistical significance of these differences were not reproducible among different experiments.

Fig. 2.

Percentages of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells and NK cells infiltrating tumor cells. FNAs were taken from tumors (n = 10 per group) at days 20 and 39 p.t.i. and then prepared as a single-cell suspension for flow cytometry analysis. a Tumor FNAs at day 20. CD8+ T cells (ANOVA, P = 0.001), CD4+ T cells (ANOVA, P = 0.0001), NK cells (ANOVA, P = 0.001). b Tumor FNAs at day 39. CD8+ T cells (ANOVA, P = 0.002), CD4+ T cells (ANOVA, ns P = 0.15), NK cells (ANOVA, P = 0.02). Data shown are mean ± standard error

Intratumoral CD4+ T cells are induced to produce type-1 and type-2 cytokines in mice vaccinated with either A20-IL-2 or A20

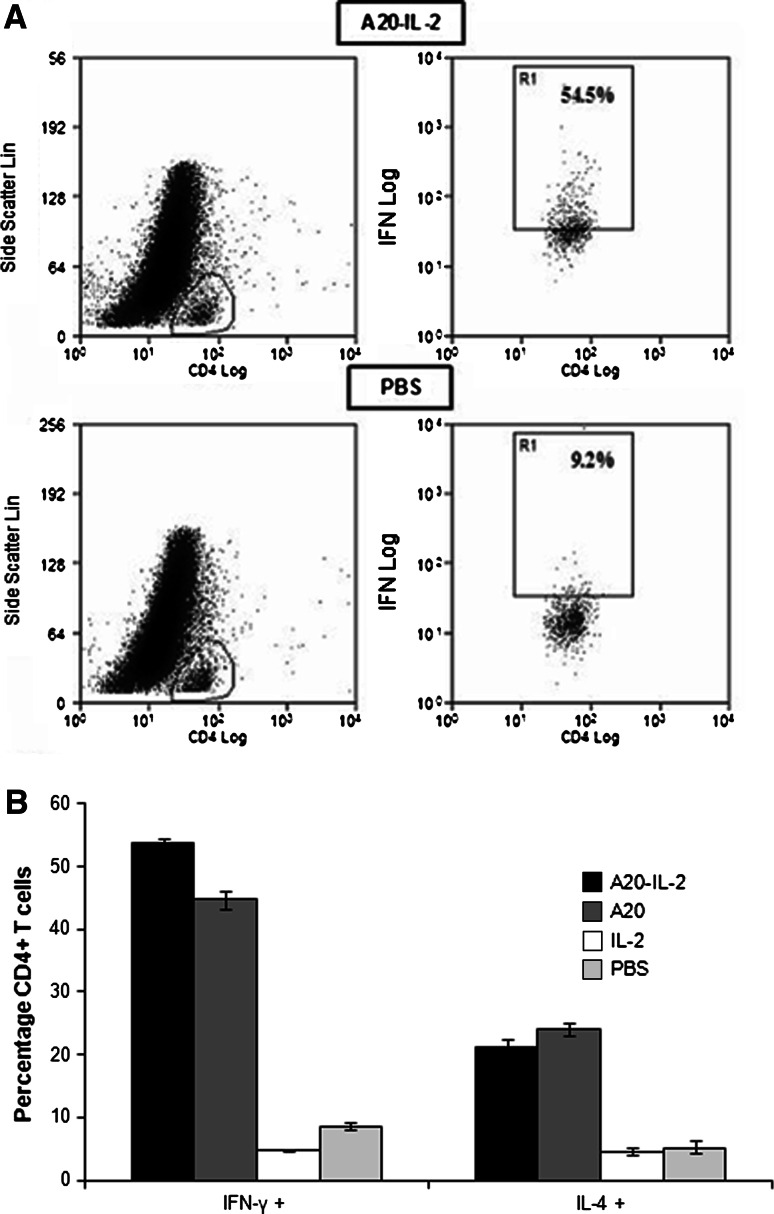

Flow cytometry detection of intracellular cytokines was performed at day 26 p.t.i on CD4+ T cells aspirated from tumors. Intracellular cytokine analysis showed a greater number of intratumoral IFN-γ and IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells in mice vaccinated with A20-IL-2 or A20 alone (Fig. 3). We observed approximately a sixfold increase of activated IFN-γ producing CD4+ T cells in mice treated with A20-IL-2 as compared with the PBS group (ANOVA, P = 0.0001). The number of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-4 was also higher (ANOVA, P = 0.0001), although to a lesser extent.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometric detection of type 1/type 2 cytokine expressions in tumors of vaccinated mice at day 26 p.t.i.. Tumor single-cell suspensions were stimulated with PMA/ionomycin, and stained with cytokine-specific antibodies (IFN-γ-PE and IL-4-PE) and with antibodies against CD4 and CD3 surface markers. a Representative flow cytometric dot plots of cells stained positive for IFN-γ are shown for A20-IL-2 and PBS groups as an example. IFN-γ+ cells are represented in R1. b Percentages of CD4+ T cells expressing INFγ (ANOVA, P = 0.0001) and IL-4 (ANOVA, P = 0.0001). Data shown are mean ± standard error

Systemic antigen-specific responses were detected in splenocytes of mice treated with A20-IL-2

Proliferative responses

The antigen-specific proliferative response was assessed on splenocytes taken at days 22 and 40 p.t.i. Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes from the different groups of mice were labeled in vitro with CFSE and then cultured with irradiated A20 tumor cells, or left non-stimulated. Proliferation was evaluated by flow cytometry as described in “Materials and methods”. As shown in Fig. 4, a strong A20 antigen-specific proliferative response was observed in splenocytes of mice vaccinated with A20-IL-2 at days 22 (ANOVA, P = 0.004) and 40 (ANOVA, P = 0.002) p.t.i. A significant antigen-specific proliferative response was also observed in the group of mice inoculated with A20 alone, but only at day 22 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Splenocytes proliferation in the different group of mice. Splenocytes cell cultures were labeled with CFSE and cultured for 5 days with irradiated A20 cells or left non-stimulated. Cell proliferation was measured by flow cytometry using Modfit software. a Total percentage of proliferation cells at day 22 p.t.i. b Total percentage of proliferation cells at day 40 p.t.i. Data shown are mean ± standard error (n = 3)

Cytokine production

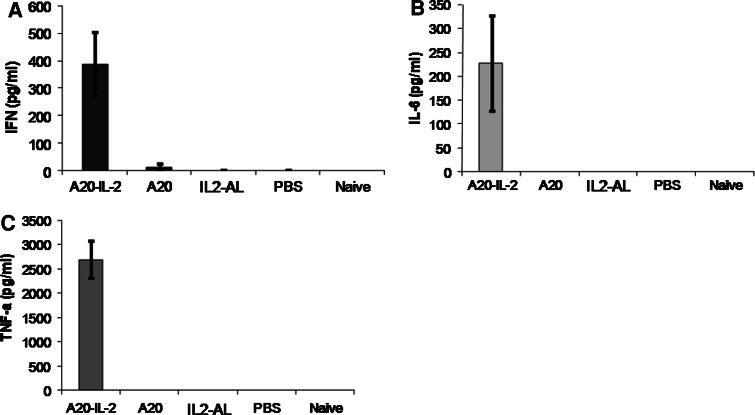

Splenocytes from 3 mice per group were cultured in vitro with irradiated A20 cells, Con A, or left non-stimulated. The supernatants concentration of IFN-γ, IL-6 and TNF-α was assessed by cytometric bead array (CBA). Only splenocytes from mice receiving the A20-IL-2 combination treatment showed a strong tumor antigen-specific production of IFN-γ (ANOVA, P = 0.0019), IL-6 (ANOVA, P = 0.007) and TNF-α (ANOVA, P = 0.005) upon stimulation with A20, whereas none of the other groups produced significant amounts of either cytokine (Fig. 5). IL-17 was also measured in the same supernatants by ELISA, but its concentration was lower than the detection limits of the kit (4 pg/ml) for all samples (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Antigen-specific cytokine responses in splenocytes. Values of cytokine concentration were measured by cytometric bead array (CBA) on the supernatant of splenocytes cell cultures after 5 days of stimulation, and expressed as the value of cytokine concentration in cell cultures stimulated with irradiated A20 cells less the value of cytokine concentration in non-stimulated cultures. Data shown are mean ± standard error (n = 3)

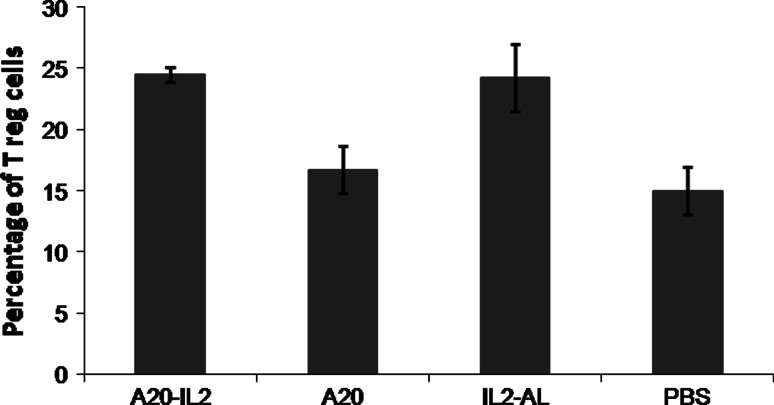

The number of regulatory T cells was higher in tumors from mice vaccinated with any of the IL-2 containing vaccine formulations

The number of CD4+CD25+/highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) was evaluated in FNAs from tumors taken at days 42 p.t.i. As shown in Fig. 6, all groups of mice receiving any form of IL-2 had a significantly higher percentage of Tregs in the tumor as compared with mice receiving the A20 vaccine or PBS (ANOVA, P = 0.002) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Percentage of intratumoral CD4+ Treg cells. FNAs were taken from tumors at days 42 and then prepared as a single-cell suspension for flow cytometry analysis. The population of regulatory T cells (Tregs) was defined as CD4+CD25+/highFoxp3+. Data represent the percentage of cells within CD4+ T cells that express CD4+CD25+/highFoxp3+ Tregs markers (mean ± standard error, n = 4 per group)

Discussion

In this report we assessed the antitumoral potency of a therapeutic vaccine formulated as tumor cells lysate combined with IL-2 adsorbed onto aluminum hydroxide. We used A20 lymphoma as an aggressive tumor model to evaluate the role of vaccination in tumor progression. Our results clearly show that therapeutic vaccination with the combined vaccine (A20-IL-2) elicits strong anti-tumor immunity that is associated with delayed tumor growth, control of tumor dissemination and longer survival in A20-bearing mice. Immune protection correlates with higher numbers of tumor’s infiltrating lymphocytes that produce type-1 and type-2 cytokines, and systemic tumor-specific cellular responses. Both the A20-derived antigenic material and the IL-2 depot formulation are required for induction of an effective immune response that impacts on cancer progression. Therapeutic treatments with either the A20 cells lysate or IL-2 in alum alone were less effective. Vaccination with A20 lysate in the absence of IL-2 elicited a transient immune response that correlated with transient therapeutic benefits, as seen by inhibition of metastases at early time points in A20-bearing mice (Fig. 1b). However, the response elicited was short-lived and weaker than the response elicited by the A20-IL-2 combination vaccine, and did not impact on primary tumor growth and survival time in those mice. Lack of extended survival in mice vaccinated with a cellular A20 vaccine has been previously reported [14]. Here, we extend those results and show that the cellular vaccine alone elicits transient immune responses that allow early and transient control of metastases.

On the other hand, treatment of tumor-bearing mice with IL-2 adsorbed on aluminum hydroxide, but not with IL-2 alone, induced extended survival in lymphoma-bearing mice (Fig. 1a), confirming the superior efficacy of alum-adsorbed IL-2 over the non-adsorbed cytokine. IL-2 has the ability to expand CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells populations in vivo and to increase the effectors functions of these cells [26, 27]. Furthermore, IL-2 stimulates the proliferation and activation of NK cells [27, 28], and previous reports have shown that the use of low-dose IL-2 expanded and activated NK cells in both animals models and cancer patients [18, 19]. We found that treatment with IL-2-AL induced a small increase in the number of intratumoral NK and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2b), thus it is reasonable to speculate that the effect of extended survival in mice receiving this treatment is due to the non-specific proliferation and activation of NK and T cells induced by IL-2 administration. However, this treatment did not elicit specific anti-tumor immune responses, and all mice presented disseminated lymphoma to the same extent than the non-treated control group. Taken altogether, the results presented here suggest that the superior antitumor efficacy of the combined A20-IL-2 treatment is due to the synergistic effect of the efficient non-specific proliferation and activation of T cells and NK cells induced by the aluminum adsorbed IL-2 and the anti-tumor specific response induced both at local and systemic level by A20 antigens.

Similarly, recently published reports showed that a vaccine consisting of IL-2 and tumor-derived antigens incorporated into a liposomal vehicle elicited strong immunity in a mouse B-cell lymphoma model, and that optimal protective immunity required the incorporation of antigens and IL-2 in the same liposomal vesicle [29, 30]. A similar strategy of depot formulation of antigens and IL-2 in a proteoliposomal vehicle is being used by others in a phase 1 clinical trial [2, 20]. Our results, show that aluminum hydroxide used as a slow release system for the IL-2, is highly effective, with the advantage that aluminum hydroxide compounds have been in clinical use for more than 70 years with a high safety profile.

On the other hand, there is now accumulated evidence showing that CD4+CD25+/highFoxp3+ Tregs cells are raised in peripheral blood and in tumors of cancer patients, and have an important role in tumor immune escape mechanisms (revised in [31, 32]). In particular, a recent report showed that when spleen cells depleted of Treg cells are adoptively transferred to Rag2−/− mice subsequently challenged with A20 cells, there is slower tumor growth and extended survival on these mice as compared with mice adoptively transferred with spleen cells with the Tregs population. The authors concluded that those results strongly suggest that Treg cells could be one mechanism by which the B-cell lymphoma evades immune surveillance [33]. However, the relationship of Treg cells and antitumor immunity is still a controversial field as evidenced by a recent report showing improved overall survival in NHL patients that had augmented Treg cells in tumor tissues [34].

It has been demonstrated that IL-2 is required for the development and expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells [35–38]. Administration of IL-2 increased Treg cells pool in patients with melanoma and renal cell carcinoma [27]. Furthermore, clinical studies where IL-2 was used either alone or in combination therapies, have shown that patients achieving an objective clinical response where those that had a significant decrease in the numbers of Treg cells [39]. In another study, it was postulated that the improved antitumoral activity of a combination therapy of IL-2 and a histone deacetylases inhibitor MS-275 was the result of IL-2 acting to increase the number of effector T cells and the administration of MS-275 inhibiting the Treg cells induced by IL-2 [40]. We found increased numbers of intratumoral CD4+CD25+/highFoxp3+ Treg cells in mice that received any form of IL-2, i.e., A20-IL-2 and IL-2-AL (Fig. 6) or non-adsorbed IL-2 (data not shown). Nevertheless, our result also demonstrates that mice receiving the combination A20-IL-2 therapy performed markedly better than all other groups tested here, which could be seen as contradictory with the augmented intratumoral Treg cells in this group. However, a recent report aimed at delineating the role of Treg cells in B-cell lymphoma development, demonstrated that although Treg cells depletion before tumor challenge resulted in slow tumor growth and extended survival, such effect was no longer observed if the depletion of Treg cells was achieved after the tumor is established [41]. Interestingly, the results of this report could be taken to suggest that in our experimental setup Treg cells expansion due to IL-2 administration was achieved after tumor establishment, and thus the effect of this cell population could be less relevant for tumor immune escape. Alternatively, it could be that despite Treg cells expansion, the A20 antigenic stimulation induced anti-tumor specific immune responses that overcome the detrimental effect of augmented Tregs. In this regard, it has been previously reported that tumor-infiltrating Treg cells in B-cell lymphoma suppressed the production of IFN-γ and IL-4 by T cells upon PHA stimulation [42]. We found increased IFN-γ and IL-4 production by infiltrating CD4+ T cells in animals vaccinated with the A20-IL-2, providing further support to the idea that our combined vaccine approach can overcome the immunosuppressor activity of intratumoral Tregs. However, our results also suggest that careful evaluation is required for the use of IL-2 in cancer immunotherapies.

Alternatives to circumvent the increase of intratumoral Treg cells elicited by the combined vaccine, may include the use of IL-15 instead of IL-2, since both cytokines have many similar functions but IL-15 has not marked effect on Tregs [27]. IL-15 also promotes the maintenance of CD8+CD44hi memory T cells and is capable of inhibiting activation-induced cell death, and it has been successfully used in colon and lung cancer models [27] suggesting that IL-15 might be an alternative for this type of vaccine formulation. Work in that direction is currently ongoing.

Overall the results presented here show that the use of this simple vaccine formulation, that can be easily prepared under GMP conditions, is a promising strategy to be used in B-cell lymphoma as well as in other hematological tumor models and may have enough merit to be tested in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a grant from the Comisión Sectorial de Investigación Científica (CSIC). Universidad de la República. Uruguay. S. Grille was funded by a scholarship of ProInBio, Uruguay and CSIC. The authors thank Prof. Dr. Miguel Torres and Tech. Mr. Marcelo Curbelo of the Departament of Radiotherapy, Hospital de Clínicas for technical assistance. S.G. designed and performed the experiments, and analyzed data. D.L. and J.A.C. designed the experiments and analyzed data. A.B. performed the experiments, collected and analyzed data. E.C and F.W.F. contributed with vital reagents (IL-2-AL), and contributed to experimental design. M.N. analyzed the data and S.G., D.L., and J.A.C. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

D. Lens, J. A. Chabalgoity share senior authorship.

Contributor Information

Daniela Lens, Phone: +598-2-4872202, FAX: +598-2-4800244, Email: dlens@hc.edu.uy.

José A. Chabalgoity, Phone: +598-2-4871288, FAX: +598-2-4873073, Email: jachabal@higiene.edu.uy

References

- 1.Marcus R, Hagenbeek A (2007) The therapeutic use of rituximab in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Eur J Haematol Suppl (67):5–14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Neelapu SS, Kwak LW (2007) Vaccine therapy for B-cell lymphomas: next-generation strategies. In: Gewirtz AM, Winter JN, Zuckerman K (eds) American Society of Hematology education program book. Atlanta, GA, pp 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Neelapu SS, Lee ST, Qin H, Cha SC, Woo AF, Kwak LW. Therapeutic lymphoma vaccines: importance of T-cell immunity. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5(3):381–394. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwak LW, Campbell MJ, Czerwinski DK, Hart S, Miller RA, Levy R. Induction of immune responses in patients with B-cell lymphoma against the surface-immunoglobulin idiotype expressed by their tumors. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(17):1209–1215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210223271705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu FJ, Caspar CB, Czerwinski D, Kwak LW, Liles TM, Syrengelas A, Taidi-Laskowski B, Levy R. Tumor-specific idiotype vaccines in the treatment of patients with B-cell lymphoma—long-term results of a clinical trial. Blood. 1997;89(9):3129–3135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmerman JM, Singh G, Hermanson G, Hobart P, Czerwinski DK, Taidi B, Rajapaksa R, Caspar CB, Van BA, Levy R. Immunogenicity of a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding chimeric idiotype in patients with B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62(20):5845–5852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timmerman JM, Czerwinski DK, Davis TA, Hsu FJ, Benike C, Hao ZM, Taidi B, Rajapaksa R, Caspar CB, Okada CY, Van BA, Liles TM, Engleman EG, Levy R. Idiotype-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination for B-cell lymphoma: clinical and immune responses in 35 patients. Blood. 2002;99(5):1517–1526. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.5.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabalgoity JA, Baz A, Rial A, Grille S. The relevance of cytokines for development of protective immunity and rational design of vaccines. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18(1–2):195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caporale A, Brescia A, Galati G, Castelli M, Saputo S, Terrenato I, Cucina A, Liverani A, Gasparrini M, Ciardi A, Scarpini M, Cosenza UM. Locoregional IL-2 therapy in the treatment of colon cancer cell-induced lesions of a murine model. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(2):985–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K, Rosenberg SA. Interleukin-2-independent proliferation of human melanoma-reactive T lymphocytes transduced with an exogenous IL-2 gene is stimulation dependent. J Immunother. 2003;26(3):190–201. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200305000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toubaji A, Hill S, Terabe M, Qian J, Floyd T, Simpson RM, Berzofsky JA, Khleif SN. The combination of GM-CSF and IL-2 as local adjuvant shows synergy in enhancing peptide vaccines and provides long term tumor protection. Vaccine. 2007;25(31):5882–5891. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaage J. Local and systemic effects during interleukin-2 therapy of mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 1987;47(16):4296–4298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bubenik J, Indrova M, Perlmann P, Berzins K, Mach O, Kraml J, Toulcova A. Tumour inhibitory effects of TCGF/IL-2/-containing preparations. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1985;19(1):57–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00199313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meziane K, Bhattacharyya T, Armstrong AC, Qian C, Hawkins RE, Stern PL, Dermime S. Use of adenoviruses encoding CD40L or IL-2 against B cell lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;111(6):910–920. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, Abrams J, Sznol M, Parkinson D, Hawkins M, Paradise C, Kunkel L, Rosenberg SA. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(7):2105–2116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fyfe G, Fisher RI, Rosenberg SA, Sznol M, Parkinson DR, Louie AC. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(3):688–696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher RI, Coltman CA, Jr, Doroshow JH, Rayner AA, Hawkins MJ, Mier JW, Wiernik P, McMannis JD, Weiss GR, Margolin KA. Metastatic renal cancer treated with interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells. A phase II clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108(4):518–523. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-4-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gluck WL, Hurst D, Yuen A, Levine AM, Dayton MA, Gockerman JP, Lucas J, Denis-Mize K, Tong B, Navis D, Difrancesco A, Milan S, Wilson SE, Wolin M. Phase I studies of interleukin (IL)-2 and rituximab in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: IL-2 mediated natural killer cell expansion correlations with clinical response. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(7):2253–2264. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenbeis CF, Grainger A, Fischer B, Baiocchi RA, Carrodeguas L, Roychowdhury S, Chen L, Banks AL, Davis T, Young D, Kelbick N, Stephens J, Byrd JC, Grever MR, Caligiuri MA, Porcu P. Combination immunotherapy of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with rituximab and interleukin-2: a preclinical and phase I study. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(18 Pt 1):6101–6110. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neelapu SS, Gause BL, Harvey L, Lee ST, Frye AR, Horton J, Robb RJ, Popescu MC, Kwak LW. A novel proteoliposomal vaccine induces antitumor immunity against follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2007;109(12):5160–5163. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neelapu SS, Baskar S, Gause BL, Kobrin CB, Watson TM, Frye AR, Pennington R, Harvey L, Jaffe ES, Robb RJ, Popescu MC, Kwak LW. Human autologous tumor-specific T-cell responses induced by liposomal delivery of a lymphoma antigen. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(24):8309–8317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falkenberg Frank W, Krup Oliver C (1999) Compositions and methods for treatment of tumors and metastatic diseases. 261816[6406689]. 18-6-2002. 3-2-1999. Ref Type: Patent

- 23.Krup OC, Kroll I, Bose G, Falkenberg FW. Cytokine depot formulations as adjuvants for tumor vaccines. I. Liposome-encapsulated IL-2 as a depot formulation. J Immunother. 1999;22(6):525–538. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199911000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agorio C, Schreiber F, Sheppard M, Mastroeni P, Fernandez M, Martinez MA, Chabalgoity JA. Live attenuated Salmonella as a vector for oral cytokine gene therapy in melanoma. J Gene Med. 2007;9(5):416–423. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu D, Yu J, Chen H, Reichman R, Wu H, Jin X. Statistical determination of threshold for cellular division in the CFSE-labeling assay. J Immunol Methods. 2006;312(1–2):126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams MA, Tyznik AJ, Bevan MJ. Interleukin-2 signals during priming are required for secondary expansion of CD8+ memory T cells. Nature. 2006;441(7095):890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature04790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waldmann TA. The biology of interleukin-2 and interleukin-15: implications for cancer therapy and vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(8):595–601. doi: 10.1038/nri1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caligiuri MA, Murray C, Robertson MJ, Wang E, Cochran K, Cameron C, Schow P, Ross ME, Klumpp TR, Soiffer RJ. Selective modulation of human natural killer cells in vivo after prolonged infusion of low dose recombinant interleukin 2. J Clin Invest. 1993;91(1):123–132. doi: 10.1172/JCI116161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak LW, Pennington R, Boni L, Ochoa AC, Robb RJ, Popescu MC. Liposomal formulation of a self lymphoma antigen induces potent protective antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 1998;160(8):3637–3641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Popescu MC, Robb RJ, Batenjany MM, Boni LT, Neville ME, Pennington RW, Neelapu SS, Kwak LW. A novel proteoliposomal vaccine elicits potent antitumor immunity in mice. Blood. 2007;109(12):5407–5410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curiel TJ. Regulatory T cells and treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beyer M, Schultze JL. Regulatory T cells in cancer. Blood. 2006;108(3):804–811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heier I, Hofgaard PO, Brandtaeg P, Jahnsen FL, Karlsson M. Depletion of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells inhibits local tumour growth in a mouse model of B cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152(2):381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tzankov A, Meier C, Hirschmann P, Went P, Pileri SA, Dirnhofer S. Correlation of high numbers of intratumoral FOXP3+ regulatory T cells with improved survival in germinal center-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Haematologica. 2008;93(2):193–200. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Almeida AR, Legrand N, Papiernik M, Freitas AA. Homeostasis of peripheral CD4+ T cells: IL-2R alpha and IL-2 shape a population of regulatory cells that controls CD4+ T cell numbers. J Immunol. 2002;169(9):4850–4860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malek TR, Yu A, Vincek V, Scibelli P, Kong L. CD4 regulatory T cells prevent lethal autoimmunity in IL-2Rbeta-deficient mice. Implications for the nonredundant function of IL-2. Immunity. 2002;17(2):167–178. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(9):665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson BH. IL-2, regulatory T cells, and tolerance. J Immunol. 2004;172(7):3983–3988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.3983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cesana GC, DeRaffele G, Cohen S, Moroziewicz D, Mitcham J, Stoutenburg J, Cheung K, Hesdorffer C, Kim-Schulze S, Kaufman HL. Characterization of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(7):1169–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato Y, Yoshimura K, Shin T, Verheul H, Hammers H, Sanni TB, Salumbides BC, Van EK, Schulick R, Pili R. Synergistic in vivo antitumor effect of the histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 in combination with interleukin 2 in a murine model of renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15 Pt 1):4538–4546. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elpek KG, Lacelle C, Singh NP, Yolcu ES, Shirwan H. CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cells dominate multiple immune evasion mechanisms in early but not late phases of tumor development in a B cell lymphoma model. J Immunol. 2007;178(11):6840–6848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang ZZ, Novak AJ, Stenson MJ, Witzig TE, Ansell SM. Intratumoral CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+ T cells in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107(9):3639–3646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]