Abstract

HM1.24 antigen (CD317) was originally identified as a cell surface protein that is preferentially overexpressed on multiple myeloma cells. Immunotherapy using anti-HM1.24 antibody has been performed in patients with multiple myeloma as a phase I study. We examined the expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells and the possibility of immunotherapy with anti-HM1.24 antibody which can induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). The expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells was examined by flow cytometry as well as immunohistochemistry using anti-HM1.24 antibody. ADCC was evaluated using a 6-h 51Cr release assay. Effects of various cytokines on the expression of HM1.24 and the ADCC were examined. The antitumor activity of anti-HM1.24 antibody in vivo was examined in SCID mice. HM1.24 antigen was detected in 11 of 26 non-small cell lung cancer cell lines (42%) and four of seven (57%) of small cell lung cancer cells, and also expressed in the tissues of lung cancer. Anti-HM1.24 antibody effectively induced ADCC in HM1.24-positive lung cancer cells. Interferon-β and -γ increased the levels of HM1.24 antigen and the susceptibility of lung cancer cells to ADCC. Treatment with anti-HM1.24 antibody inhibited the growth of lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen in SCID mice. The combined therapy with IFN-β and anti-HM1.24 antibody showed the enhanced antitumor effects even in the delayed treatment schedule. HM1.24 antigen is a novel immunological target for the treatment of lung cancer with anti-HM1.24 antibody.

Keywords: HM1.24 antigen, Lung cancer, Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, Interferon, Immunotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading world-wide cause of cancer deaths. The care rate remains less than 15% despite improvements in surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy [1, 2]. To prolong the survival of patients with lung cancer, the development of novel therapeutic modalities is of much interest. Recently, drugs targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) including gefitinib and erlotinib have been shown to be effective against advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [3, 4]. Immunotherapy using monoclonal antibodies (mAb) is also expected to be a clinically useful molecular-targeting approach [5]. Recently, the administration of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mAbs (Avastin) together with chemotherapy (paclitaxel and carboplatin) for NSCLC significantly improved median survival (12.3 vs. 10.3 months) and median progression-free survival (6.2 vs. 4.5 months) as compared with chemotherapy alone [6]. A phase II trial of the anti-EGFR mAb (Cetuximab) in patients with previously treated NSCLC showed a 4.5% response rate and 30.3% stable disease, which was similar to that of pemetrexed, docetaxel, and erlotinib in similar groups of patients [7].

HM1.24 was originally identified as a cell surface protein that is preferentially overexpressed on multiple myeloma (MM) cells [8, 9], and later found to be identical to bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 (BST-2) [10]. HM1.24/BST-2 (CD317) is also expressed in terminally differentiated B cells [8]. Immunotherapy with a monoclonal antibody against HM1.24, which induced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), reduced tumor size and improved survival in a MM model in mice [11]. Furthermore, we and others recently identified the antigenic peptides present on HLA-A2 or A24 and effectively generated the cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of both healthy subjects and patients with MM [12, 13]. These results strongly suggest HM1.24 antigen to be a useful immunological target on MM.

Recently, using a large-scale method to identify target genes such as the serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and microarrays, the HM1.24 gene has been found to be overexpressed in several solid tumor cells which exhibited invasive or drug-resistant phenotypes [14, 15]. However, little is known about the expression status of HM1.24 antigen in solid cancer, particularly at the protein level, and its potential as an immunological target for therapy with anti-HM1.24 antibody.

In the present study, we demonstrated the expression of HM1.24 antigen in 42% of lung cancer cell lines as well as primary cultured lung cancer cells from malignant pleural effusions, and that the administration of anti-HM1.24 antibody significantly inhibited the growth of lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen in SCID mice, presumably via ADCC and CDC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The human lung cancer cell lines, SBC-3 and SBC-5, were kindly provided by Dr. Hiraki (Okayama University, Okayama, Japan) [16]. The human squamous cell lung carcinoma RERF-LC-AI and RERF-LC-OK cells were provided by Dr. M. Akiyama (Radiation Effects Research Foundation, Hiroshima, Japan) [16]. The human lung adenocarcinoma cell line PC-14 was a gift from Dr. N. Saijo (National Cancer Institute, Tokyo, Japan) [16]. The human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines ACC-LC-174 and ACC-LC-176 were provided by Dr. T. Takahashi (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan). Other cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville MD). These cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Meiji Seika Kaisha, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), designated as CRPMI1640.

To establish the primary culture of lung cancer cells, a fraction of mononuclear cells from malignant pleural effusion in patients with lung cancer was harvested using density-centrifugation with Lymphocyte Separation Medium (LSM; Litton Bionectics, Kensington, MD), and cultured in CRPMI 1640 to establish tumor cell lines as previously described [16]. The human study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Tokushima and written informed consent was obtained from all the subjects.

Reagents

Recombinant human interleukin (IL)-6, interferon (IFN)-β, and IFN-γ were obtained from R&D systems (Minneaplis, MN). The mouse anti-HM1.24 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (IgG2aκ) was provided by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd, (Shizuoka, Japan). Mouse IgG2a was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA).

Flow cytometry

The expression of the HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells was examined by flow cytometry [17]. Briefly, cells (5 × 105) were resuspended in PBS supplemented with 10% pooled AB serum to prevent non-specific binding to the Fc receptor. The cells were washed with cold PBS and stained on ice for 30 min with the murine, chimeric, or humanized anti-HM1.24 mAb or control IgG. After incubation with the primary mAb, cells were washed with cold PBS and then incubated on ice for an additional 30 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 fragment anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA) or a FITC-conjugated goat IgG fraction to human IgG Fc (Beckman Coulter Inc.). The cells were washed again and resuspended in cold PBS. The analysis was performed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). The mean specific fluorescence intensity (MSFI) was calculated as the ratio of the MFI of anti-HM1.24 mAb to that of control mAb.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as described previously [18]. Lung cancer cells were cultured in the Lab-Tek II Chamber Slide System (Nalge Nunc International Corp., Naperville, IL), fixed in cold acetone for 10 min, and stained with mouse anti-HM1.24 antibody and Alexa fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). These slides were mounted with VECTASHIELD mounting medium containing 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA), and visualized using a fluorescence microscope (OLIMPUS BX61; OLYMPUS OPTICAL Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry

Fresh frozen lung tissues were obtained from patients with lung cancer by trans-bronchial lung biopsy using a flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope (Model 1T20; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan). Fragments of the tissues were covered with OCT compound (Ames, Elkhart, IN), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analyzed. Six-micron sections were dried and fixed in cold acetone for 10 min. Staining was performed using R.T.U. VECTASTAIN Universal Quick Kit (Vector Laboratories) [18]. The sections were incubated in 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min to inhibit endogenous peroxidase, and incubated in blocking serum for 10 min. The slides were then incubated overnight with anti-HM1.24 antibody at 4°C. After washing, sections were incubated in prediluted biotinylated panspecific universal secondary antibody for 10 min, followed by incubation in ready-to-use streptavidin/peroxidase complex reagent for 5 min. Sections were developed with a diaminobenzidine substrate kit (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (MUTO PURE CHEMICALS CO., LTD., Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of effector cells

Splenocytes were harvested from SCID mice as described previously [19, 20]. Briefly, spleens were minced and homogenized in CRPMI1640 and centrifuged after passing through the cell strainer (BD Biosciences, MA). The cell pellet was suspended in RBC lysis buffer (0.83% NH4Cl) and left on ice for 5 min. After two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (−), splenocytes were resuspended in CRPMI1640 and used as effector cells.

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity was determined by conducting a standard 6-h 51Cr-release assay as described previously [17, 19, 20]. In some experiments, effector cells were cultured in CRPMI1640 with or without recombinant IFNs for 24 h, then washed and resuspended in the medium prior to use. Target cells were labeled with 0.1 μCi of Na51CrO4 at 37°C for 1 h. After three washes with RPMI1640 medium, 51Cr-labeled target lung cancer cells (1 × 104) were placed in 96-well plates in a triplicate culture, and various concentrations of anti-HM1.24 mAb or control IgG were added to the wells. Effector cells were then added to the plates at various effector to target (E/T) ratios. After a 6-h incubation, supernatants (100 μL) were harvested and measured in a gamma counter. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated from the following formula: % Specific lysis = (E − S)/(M − S) × 100, where E is the release in the test sample (cpm in the supernatant from target cells incubated with effector cells and test antibody), S is the spontaneous release (cpm in the supernatant from target cells incubated with medium alone), and M is the maximum release (cpm released from target cells lysed with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate). The spontaneous release observed with different target cells ranged from 5 to 15%.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)

Cell lysis with complement was evaluated using a 51Cr-release assay [18]. Target cells were labeled with 0.1 μCi of 51Cr-sodium chromate at 37°C for 1 h. The cells were then washed three times with CRPMI1640. 51Cr-labeled cells (1 × 104) were added into 96-well plates and incubated with serial dilutions of baby rabbit complement (Cedarlane, ON, Canada) and the anti-HM1.24 mAb or control IgG for 2 h. After this incubation, the supernatant from each well (100 μL) was harvested and 51Cr-release was measured using a gamma counter. Percent cytotoxicity was calculated as above.

In vitro proliferation assay

To measure the growth of lung cancer cells, we used the 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay [17, 21]. Briefly, various tumor cells (5 × 103) were incubated in 96-well plates for 72 h with anti-HM1.24 antibody or control IgG, or various concentrations of IFNs. Then, 50 μl of MTT solution (2.5 mg/ml) was added and the cells were pulsed for 1 h and lysed with DMSO. The experiments were performed in triplicate. Absorbance was measured with an MTP-32 Microplate Reader (Corona Electric, Ibaragi, Japan) at test and reference wavelengths of 550 and 630 nm, respectively.

Animal experiments

Eight-week-old SCID female mice were purchased from Charles River Japan Inc. (Yokohama, Japan). The mice were maintained in the animal facility of the University of Tokushima under specific pathogen-free conditions according to the guidelines of our university. Mice were injected subcutaneously into the right flank with 3 × 106 SBC-5 cells on day 0. Tumor size was expressed as tumor area (mm2) (the longest diameter × the shortest diameter). The anti-HM1.24 antibody was administered intraperitoneally, and IFNs were injected into peritumoral areas.

Statistical analysis

A one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.03 for Windows, GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant. All experiments were performed at least three times. The correlation between ADCC activity and HM1.24 expression on target cells was evaluated with Pearson’s rank correlation analysis.

Results

Expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells

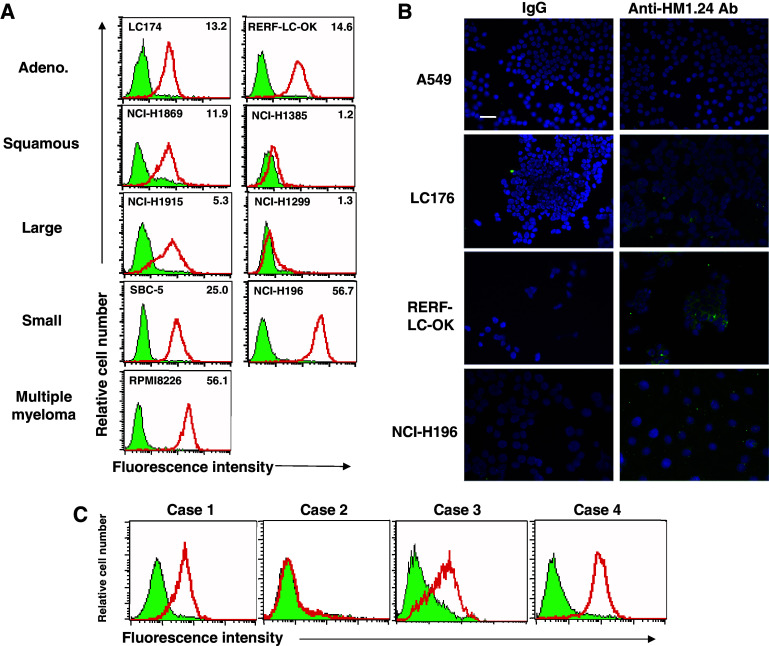

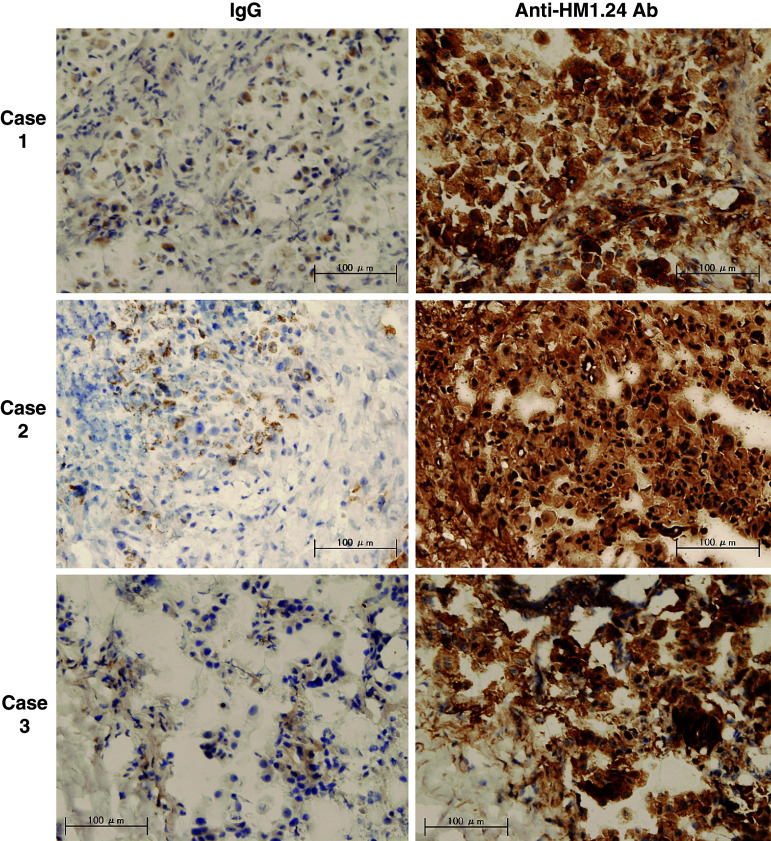

First, we examined whether HM1.24 antigen was expressed on the surface of lung cancer cells using flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1a, various lung cancer cells including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, large cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma cells expressed HM1.24 antigen on their surface at various levels. The level of HM1.24 antigen in NCI-H196 cells was comparable to that in multiple myeloma cells RPMI8226. In summary, 42% (11/26) of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells and 57% (4/7) of small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells were positive for HM1.24 (Table 1). The high level of HM1.24 antigen, which is defined as a ratio of the mean fluorescence intensity of anti-HM1.24 antibody to that of control IgG of more than 10, was observed in 21% of all cell lines. The expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells was confirmed by immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1b). When we examined the expression of HM1.24 antigen in the primary cultured cells derived from malignant pleural effusion due to lung cancer, positive expression was observed in three of four primary cultures (Fig. 1c). In addition, the expression of HM1.24 antigen in tissues of lung cancer was demonstrated by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells. a Flow cytometric analysis of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cell lines. Lung cancer cell lines were stained with anti-HM1.24 antibody (bold line) and control IgG (hatched area). The numbers in the right upper corner in each figure indicate the mean specific fluorescence intensity (MSFI). b Immunofluorescence staining of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cell lines. Various lung cancer cells were cultured in the Chamber Slide system and stained with anti-HM1.24 antibody and Alexa fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) antibody (green fluorescence) and 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; by which nuclei were counterstained) (blue). Immunostaining was visualized usng a fluorescence microscope (×200) (bars 50 μm). c Flow cytometric analysis of HM1.24 antigen in primary cultured cells from malignant pleural effusion due to lung cancer. The primary cultured cells were generated from malignant pleural effusion in four patients with lung cancer. Each of the primary cultured cells was stained with anti-HM1.24 antibody (bold line) and control IgG (hatched area) (color in online)

Table 1.

Expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells

| Histological type | Number of cell lines | Positiveb (%) | Negative (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Highc | Low | |||

| NSCLC | 26 | 11 (42) | 5 (19) | 6 (23) | 15 (58) |

| Adenoca. | 15 | 7 (47) | 4 (27) | 3 (20) | 8 (53) |

| Squamous cell ca. | 5 | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 3 (60) |

| Large cell ca. | 6 | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 4 (67) |

| SCLC | 7 | 4 (57) | 2 (29) | 2 (29) | 3 (43) |

| Total | 33 | 15 (45) | 7 (21) | 8 (24) | 18 (55) |

HM1.24 expression was examined by flow cytometry. The mean specific fluorescence intensity (MSFI) was calculated as the ratio of MFI of anti-HM1.24 MoAb/control MoAb

aThe positive expression of HM1.24 antigen was defined as >1.1

bThe high-level expression of HM1.24 antigen was defined as a MSFI of >10

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of HM1.24 antigen in lung caner. The cancer tissues were harvested by a trans-bronchial biopsy from patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Fresh frozen tissues were sectioned, and stained with control mouse IgG or anti-HM1.24 antibody (×200) (bar 100 μm)

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and complement- dependent cytotoxicity of anti-HM1.24 antibody against lung cancer cells

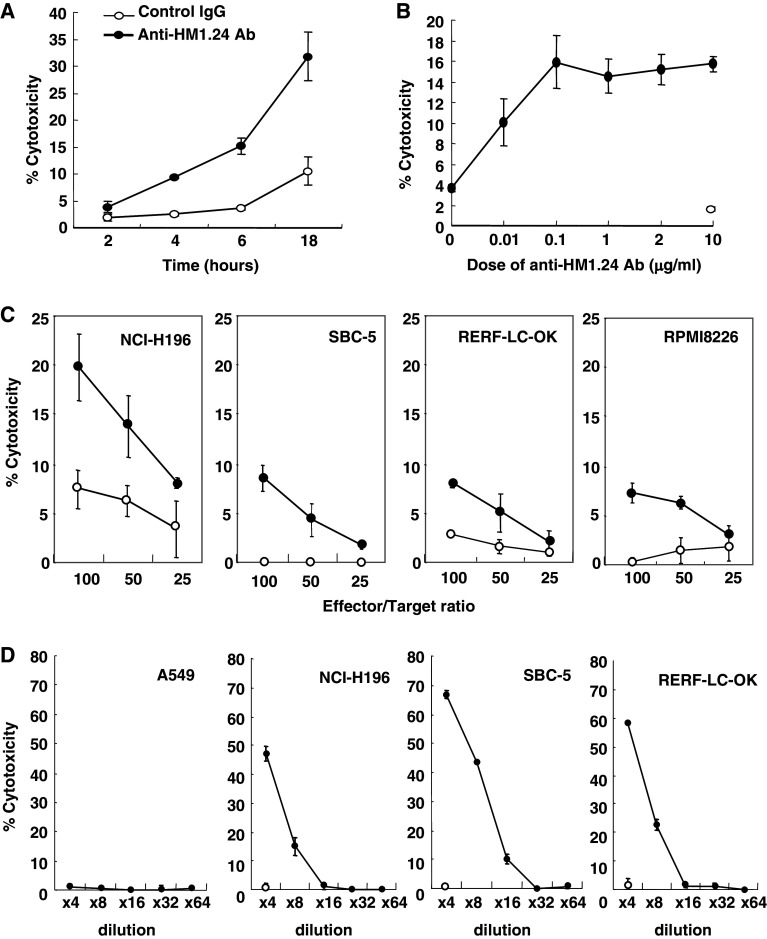

Next, we examined whether anti-HM1.24 antibody can induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) among lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen using splenocytes from SCID mice. Figure 3a showed that the mouse anti-HM1.24 antibody effectively induced ADCC against NCI-H196 cells in a dose-dependent manner. More than 0.1 μg/ml of antibody significantly mediated the optimal level of ADCC activity (Fig. 3b). The levels of ADCC in NCI-H196, SBC-5, and RERF-LC-OK cells are identical to that in RPMI8226 myeloma cells (Fig. 3c). ADCC was not detected when peritoneal macrophages were used as an effector cells (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Antibody-dependent cellular and complement-dependent cytotoxicities of anti-HM1.24 antibody against lung cancer cells. a, b Time- and dose-dependent effects of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) by anti-HM1.24 antibody. Murine solenocytes were harvested from SCID mice and used as effector cells. The ADCC of control mouse IgG2a (open circle) or anti-HM1.24 antibody (filled circle) was evaluated in NCI-H196 cells using a 51Cr release assay at an effector/target ratio of 100. In the time-course experiment, 1 μg/mL of anti-HM1.24 antibody was used. C) ADCC of anti-HM1.24 antibody against various lung cancer cells. The activity of 1 μg/mL of control mouse IgG2a (open circle) or anti-HM1.24 antibody (filled circle) was examined in lung cancer cells including NCI-H196, SBC-5, and RERF-LC-OK cells and in RPMI8226 myeloma cells using a 6-h 51Cr release assay at an effector/target ratio of 100. d Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC). The CDC of anti-HM1.24 antibody (1 μg/mL) was determined using a 2-h 51Cr release assay. The horizontal line indicates the dilution of complement. Open circles indicate the CDC of control IgG2a

We also examined the complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) exhibited by anti-HM1.24 antibody. Figure 3d showed that HM1.24 antigen-expressing lung cancer cells including NCI-H196, SBC-5 and RERF-LC-OK cells, but not HM1.24 antigen-negative A549 cells, were sensitive to CDC.

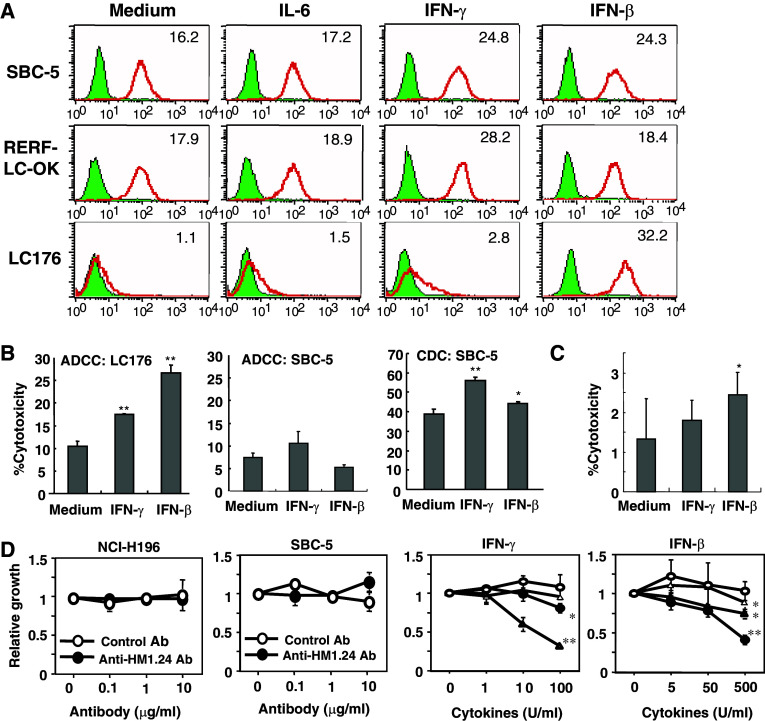

Regulation of expression of HM1.24 antigen by cytokines in lung cancer cells and susceptibility to ADCC of anti-HM1.24 antibody

The analysis of the HM1.24 promoter region showed the existence of a IL-6 response type II element/APRF site, CTGG(G/A)AA (the STAT3 binding site), type I element/NF-IL6 site, T(T/G)NNGNAA(T/G), and IFN response elements IRF-1/2, AAAAG(T/C)GAAA, and ISGF3, AGTTTCNNTTTCN(C/T) [9]. Therefore, we examined the effects of IL-6 and IFNs on the expression of HM1.24. Both IFNs, IFN-β and IFN-γ, but not IL-6, enhanced the expression of HM1.24 in most lung cancer cells (Fig. 4a). However, the level of enhancement was dependent on the cell line. To examine whether the enhancement of HM1.24 antigen by IFN contributes to the augmentation of the susceptibility to the ADCC of anti-HM1.24 antibody, several lung cancer cells were pretreated with IFN-β and IFN-γ for 24 h. In Fig. 4b, ADCC among LC176 cells was enhanced by treatment with both IFN-β and IFN-γ. Although the treatment of SBC-5 cells with IFNs significantly augmented CDC activity by anti-HM1.24 antibody, ADCC was not significantly enhanced. Furthermore, pre-treatment of splenocytes with IFN-β augmented the ADCC against SBC-5 cells (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Effects of interferon on the expression of HM1.24 antigen and susceptibility to the ADCC and CDC of anti-HM1.24 antibody in lung cancer cells. a Effects of treatment of lung cancer cells with interleukin-6 and interferons (IFN-β and IFN-γ) on HM1.24 expression. The lung cancer cells (SBC-5, RERF-LC-OK and LC176) were cultured with IL-6 (100 ng/mL), IFN-β (500 U/mL), or IFN-γ (100 U/mL) for 48 h and examined for the expression of HM1.24 antigen by flow cytometry. b Susceptibility of lung cancer cells to the ADCC and CDC of anti-HM1.24 antibody after treatment with IFNs. LC176 and SBC-5 cells were treated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) or IFN-γ (100 U/mL) for 48 h and used as target cells in ADCC and CDC assays using anti-HM1.24 antibody. *P < 0.05 versus cytotoxicity against cells without IFN treatment, **P < 0.01 versus cytotoxicity against cells without IFN treatment. c Effect of treatment of splenocytes with IFNs on the ADCC of anti-HM1.24 antibody. Murine splenocytes from SCID mice were treated with IFN-β (500 U/mL) or IFN-γ (100 U/ml) for 48 h and used as effector cells in the ADCC assay. *P < 0.05 versus cytotoxicity of splenocytes without IFN treatment. d Direct antitumor effects of anti-HM1.24 antibody or IFNs. Lung cancer cells (5 × 103) were plated in 96-well plates and cultured in various concentrations of anti-HM1.24 antibody or INFs for 72 h. The cell growth was determined using the MTT assay described in “Materials and methods”. In the experiments with IFN, NCI-H196 (open circle), SBC-5 (open triangle), RERF-LC-OK (filled circle), and LC174 cells (filled triangle) were used. *P < 0.05 versus the absorbance of control cells, **P < 0.01 versus the absorbance of control cells

Anti-HM1.24 antibody was not directly cytotoxic to lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen (Fig. 4d). On the other hand, IFN-β and -γ showed the direct growth-inhibitory effects on several lung cancer cell lines in vitro (Fig. 4d).

Antitumor effects of anti-HM1.24 antibody on the growth of lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen in SCID mice

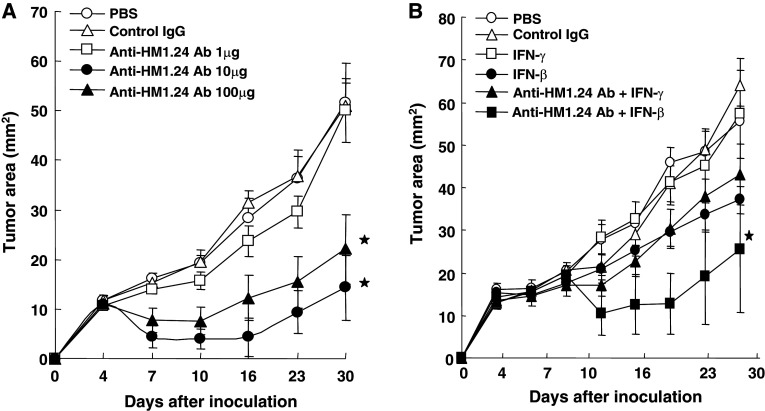

Using lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen, we examined whether anti-HM1.24 antibody show the antitumor effects in vivo. Following our previous study using myeloma cells (11), mice were treated with anti-HM1.24 antibody. As shown in Fig. 5a, administration of the antibody inhibited the growth of SBC-5 cells. More than 10 μg/day of antibody was significantly effective in reducing tumor growth. Even with late treatment, the combined use of human IFN-β, but not IFN-γ, was significantly effective in inhibiting tumor growth (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Antitumor effects of anti-HM1.24 antibody on the growth of SBC-5 in SCID mice. Mice (four mice/group) were inoculated subcutaneously with SBC-5 cells (3 × 106) on day 0. Anti-HM1.24 antibody was injected intraperitoneally. With the early treatment schedule, treatment with various doses of antibody was started when the tumor became palpable on day 4 and injected on days 7 and 11 (a). Tumor size was measured every 3 or 4 days. In the late treatment model (b), interferons (2 × 104 units/injection) was injected into the petitumoral area from day 6 to 11 and from day 13 to 17, and antibody was administered on days 8, 12, 15 and 19 (bars show SEs of the means). *P < 0.05 versus the group with PBS treatment

Discussion

We have demonstrated that human lung cancer cells expressed HM1.24 antigen, and that anti-HM1.24 antibody, which effectively induced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) in vitro, suppressed the growth of lung cancer cells expressing HM1.24 antigen in SCID mice.

There is little data available regarding the expression of HM1.24 antigen in solid cancers, especially lung cancer. Our data showed that more than 40% of lung cancer cell lines expressed the antigen. Using primary cultured cells as well as lung cancer tissues, we also showed the significant expression of HM1.24, suggesting that lung cancer cells can express the antigen in vivo.

Several tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) including MAGE, LAGE, NY-ESO-1, SSX, Her-2/neu, and WT-1 have been reported to be expressed in lung cancer [22–26]. Recent studies using oligonucleotides or tissue microarrays also confirmed the expression of these TAAs in lung caner tissues [27, 28]. Among the most frequently expressed TAAs in lung cancer are the MAGE family, especially MAGE-3A (40–50%). The rate of expression of HM1.24 antigen (45%) in lung cancer cells is comparable to that of MAGE-3A, indicating that HM1.24 antigen might be useful as an immunological target in lung cancer. A correlation between the expression of cancer/testis antigens including MAGE and poor prognosis of cancer patients has been reported [28, 29], therefore the relationship between HM1.24 expression and patient status will be our next topic of study.

Molecular-targeting drugs are divided into two groups, small-molecules and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) [30]. The putative mechanisms of mAb-based cancer therapy can be classified into two categories [30, 31]. One mechanism is direct action to block the function of target signaling molecules or receptors or stimulate apoptosis. The other is indirect action mediated by immune systems including ADCC and CDC. It has been reported that the HM1.24 gene is one of the important activators of the NF-κB pathway [32], suggesting that the signaling from HM1.24 antigen affects the biological responses of HM1.24-expressing cells. However, in the present study, no direct cytotoxic effects by the anti-HM1.24 antibody were observed in lung cancer cells. Therefore, the antitumor effect of the antibody seems to be mediated mainly by ADCC or CDC in vivo. Furthermore, since we found that murine splenocytes, but not macrophages, in SCID mice could mediate ADCC, NK cells was thought to be main effector cells in ADCC induced by anti-HM1.24 antibody.

Finally, we demonstrated that the administration of anti-HM1.24 antibody reduced the growth of SBC-5 cells in SCID mice. The suppressive effects on tumor growth were observed when the treatment was started on day 4. However, if the initiation of therapy was delayed until day 8, the antibody exhibited the reduced antitumor effects (data not shown). These results suggest that it is more difficult to treat large tumors with the antibody alone. To enhance the antitumor effects of anti-HM1.24 antibody, we examined the influence of interferon (IFN). The combination of anti-HM1.24 antibody and IFN-β had significant antitumor effects even when the treatment was started on day 8. These effects might be due to some direct influence of IFN-β on tumor cells, such as the up-regulation of the expression of HM1.24 antigen and suppression of the growth of SBC-5 cells in vitro. Furthermore, another effect that treatment of murine splenocytes with human IFN-β, but not IFN-γ, enhanced the ADCC of anti-HM1.24 antibody might contribute to the combined antitumor effects.

Interestingly, the recent study showed that CD34 ± bone-marrow progenitor cells also express HM1.24 antigen [33], suggesting the possibility of HM1.24 expression in cancer stem cells. To further clarify the mechanisms involved in the antitumor effects of anti-HM1.24 antibody in vivo, this issue should be solved in the next experiments.

In summary, we demonstrated the expression of HM1.24 antigen in lung cancer cells and that immunotherapy with anti-HM1.24 antibody, particularly in combination with IFN-β, effectively suppressed the growth of lung cancer cells in mice. Furthermore, we reported that antigenic peptides derived from HM1.24 antigen induced the formation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [12]. These results suggest HM1.24 antigen to be a useful immunological target in antibody-based as well as vaccine-based immunotherapy for the treatment of lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Tomoko Oka for technical assistance. This work was supported by KAKENHI (18590855), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan.

References

- 1.Hoffman PC, Mauer AM, Vokes EE. Lung cancer. Lancet. 2000;355:479–485. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)82038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiro SG, Silvestri GA. One hundred years of lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:523–529. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200504-531OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackhall F, Ranson M, Thatcher N. Where next for gefitinib in patients with lung cancer? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:499–507. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saijo N. Recent trends in the treatment of advanced lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:448–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egri G, Takats A. Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of lung cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, Brahmer J, Schiller JH, Dowlati A, Lilenbaum R, Johnson DH. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna N, Lilenbaum R, Ansari R, Lynch T, Govindan R, Janne P, Bonomi P. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5253–5258. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto T, Kennel SJ, Abe M, Takishita M, Kosaka M, Solomon A, Saito S. A novel membrane antigen selectively expressed on terminally differentiated human B cells. Blood. 1994;84:1922–1930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohtomo T, Sugamata Y, Ozaki Y, Ono K, Yoshimura Y, Kawai S, Koishihara Y, Ozaki S, Kosaka M, Hirano T, Tsuchiya M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a surface antigen preferentially overexpressed on multiple myeloma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;258:583–591. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishikawa J, Kaisho T, Tomizawa H, Lee BO, Kobune Y, Inazawa J, Oritani K, Itoh M, Ochi T, Ishihara K, Hirano T. Molecular cloning and chromosomal mapping of a bone marrow stromal cell surface gene, BST2, that may be involved in pre-B-cell growth. Genomics. 1995;26:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80171-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozaki S, Kosaka M, Wakatsuki S, Abe M, Koishihara Y, Matsumoto T. Immunotherapy of multiple myeloma with a monoclonal antibody directed against a plasma cell-specific antigen, HM1.24. Blood. 1997;90:3179–3186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jalili A, Ozaki S, Hara T, Shibata H, Hashimoto T, Abe M, Nishioka Y, Matsumoto T. Induction of HM1.24 peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by using peripheral-blood stem-cell harvests in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:3538–3545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hundemer M, Schmidt S, Condomines M, Lupu A, Hose D, Moos M, Cremer F, Kleist C, Terness P, Belle S, Ho AD, Goldschmidt H, et al. Identification of a new HLA-A2-restricted T-cell epitope within HM1.24 as immunotherapy target for multiple myeloma. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter-Yohrling J, Cao X, Callahan M, Weber W, Morgenbesser S, Madden SL, Wang C, Teicher BA. Identification of genes expressed in malignant cells that promote invasion. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8939–8947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker M, Sommer A, Kratzschmar JR, Seidel H, Pohlenz H-D, Fichtner I. Distinct gene expression patterns in a tamoxifen-sensitive human mammary carcinoma xenograft and its tamoxifen-resistant subline MaCa 3366/TAM. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:151–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitani K, Nishioka Y, Yamabe K, Ogawa H, Miki T, Yanagawa H, Sone S. Soluble Fas in malignant pleural effusion and its expression in lung cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:302–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01437.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishioka Y, Yano S, Fujiki F, Mukaida N, Matsushima K, Tsuruo T, Sone S. Combined therapy of multidrug-resistant human lung cancer with anti-P-glycoprotein antibody and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene trasduction: the possibility of immunological overcoming of multidrug resistance. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:170–177. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<170::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishioka Y, Manabe K, Kishi J, Wang W, Inayama M, Azuma M, Sone S. CXCL9 and 11 in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis: a role of alveolar macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;149:317–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishioka Y, Hirao M, Robbins PD, Lotze MT, Tahara H. Induction of systemic and therapeutic antitumor immunity using injection of dendritic cells genetically modified to express interleukin 12. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4035–4041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanibuchi M, Yano S, Nishioka Y, Yanagawa H, Kawano T, Sone S. Therapeutic efficacy of mouse-human chimeric anti-ganglioside GM2 monoclonal antibody against multiple organ micrometastases of human lung cancer cells in NK-depleted SCID mice. Int J Cancer. 1998;78:480–485. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19981109)78:4<480::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrivastava P, Hanibuchi M, Yano S, Parajuli P, Tsuruo T, Sone S. Circumvention of multidrug resistance by a quinoline derivative, MS-209, in multidrug-resistant human small-cell lung cancer cells and its synergistic interaction with cyclosporine A or verapamil. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:483–490. doi: 10.1007/s002800050849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:380–384. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weynants P, Lethe B, Brasseur F, Marchand M, Boon T. Expression of MAGE genes by non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:826–829. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shichijo S, Hayashi A, Takamori S, Tsunosue R, Hoshino T, Sakata M, Kuramoto T, Oizumi K, Itoh K. Detection of MAGE-4 protein in lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:158–165. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wroblewski JM, Bixby DL, Borowski C, Yannelli JR. Characterization of human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines for expression of MHC, co-stimulatory molecules and tumor-associated antigens. Lung Cancer. 2001;33:181–194. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(01)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tajima K, Obata Y, Tamaki H, Yoshida M, Chen Y-T, Scanlan MJ, Old LJ, Kuwano H, Takahashi T, Takahashi T, Mitsudomi T. Expression of cancer/testis (CT) antigens in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:23–33. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugita M, Geraci M, Gao B, Powell RL, Hirsch FR, Johnson G, Lapadat R, Gabrielson E, Bremnes R, Bunn PA, Franklin WA. Combined use of oligonucleotide and tissue microarrays identifies cancer/testis antigens as biomarkers in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3971–3979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolli M, Kocher T, Adamina M, Guller U, Dalquen P, Haas P, Mirlacher M, Gambazzi F, Harder F, Heberer M, Sauter G, Spagnoli GC. Tissue microarray evaluation of melanoma antigen E (MAGE) tumor-associated antigen expression. Ann Surg. 2002;236:785–793. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gure AO, Chua R, Williamson B, Gonen M, Ferrera CA, Gnjatic S, Ritter G, Simpson AJG, Chen Y-T, Old LJ, Altorki NK. Cancer-testis genes are coordinately expressed and are markers of poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8055–8062. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai K, Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nature. 2006;6:714–727. doi: 10.1038/nrc1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams GP, Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy of caner. Nature Biotechnol. 2005;23:1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuda A, Suzuki Y, Honda G, Muramatsu S, Matsuzaki O, Nagano Y, Doi T, Shimotohno K, Harada T, Nishida E, Hayashi H, Sugano S. Large-scale identification and characterization of human genes that activate NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:3307–3318. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vidal-Laliena M, Romero X, March S, Requena V, Petriz J, Engel P. Characterization of antibodies submitted to the B cell section of the 8th human leukocyte deifferentiation antigens workshop by flow cytometory and immunohistochemistry. Cell Immunol. 2005;236:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]