Abstract

Previous studies have shown that there are profuse lymphatic tissues under the intestinal mucous membrane. Moreover, vaccine administered orally can elicit both mucous membrane and system immune response simultaneously, accordingly induce tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte. As a result, the oral route is constituted the preferred immune route for vaccine delivery theoretically. However, numerous vaccines especially protein/peptide vaccines remain poorly available when administered by this route. Nanoemulsion has been shown as a useful vehicle can be developed to enhance the antitumor immune response against antigens encapsulated in it and it is good for the different administration routes. Of particular interest is whether the protein vaccine following peroral route using nanoemulsion as delivery carrier can induce the same, so much as stronger antitumor immune response to following conventional ways such as subcutaneous (sc.) or not. Hence, in the present study, we encapsulated the MAGE1-HSP70 and SEA complex protein in nanoemulsion as nanovaccine NE (MHS) using magnetic ultrasound method. We then immuned C57BL/6 mice with NE (MHS), MHS alone or NE (-) via po. or sc. route and detected the cellular immunocompetence by using ELISpot assay and LDH release assay. The therapeutic and tumor challenge assay were examined then. The results showed that compared with vaccination with MHS or NE (-), the cellular immune responses against MAGE-1 could be elicited fiercely by vaccination with NE (MHS) nanoemulsion. Furthermore, encapsulating MHS in nanoemulsion could delay tumor growth and defer tumor occurrence of mice challenged with B16-MAGE-1 tumor cells. Especially, the peroral administration of NE (MHS) could induce approximately similar antitumor immune responses to the sc. administration, but the MHS unencapsulated with nanoemulsion via po. could induce significantly weaker antitumor immune responses than that via sc., suggesting nanoemulsion as a promising carrier can exert potent antitumor immunity against antigen encapsulated in it and make the tumor protein vaccine immunizing via po. route feasible and effective. It may have a broad application in tumor protein vaccine.

Keywords: Tumor vaccine, Nanoemulsion, Peroral (po.)

Introduction

The tumor-specific antigen (TSA) can generate tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) and damage tumor cells. Today, tumor vaccines based on TSA play an important role in the prevention and therapy of tumor and have been regarded as the most attractive method. The melanoma antigen (MAGE) was the first reported example of TSA. MAGE-1 is an important member of MAGE, which is expressed in most tumors but not in normal tissues except the testes and placenta. Moreover, MAGE-1 antigen has been termed as tumor-rejection antigens because tumors expressing these antigens on appropriate human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules are rejected by host CTLs [39].

As molecular chaperone, heat shock protein (HSP) participates in processing and presenting of tumor antigens and plays an important role in eliciting antitumor immunity. A previous study has shown that HSP70 could be exploited to enhance the cellular and humoral immune responses against any attached tumor-specific antigens [25].

Staphylococcal enterotoxins A (SEA) is a classical model of superantigens. It forms complex with MHC class II molecules on antigen-presenting cells binds to the outside of the antigen binding cleft to stimulate as much as 20% of the T-cell repertoire via V β-specific elements of the T-cell receptor [42]. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been shown to proliferate in response to these superantigens [16]. Furthermore, this massive activation of T cells is accompanied by an increased production of cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ).

As a member of nano-delivery system, nanoemulsion is considered superior due to its small size, higher protection and absorption of water-soluble drugs or peptides/proteins following intraduodenal administration, and elegant compatibility with tissues as well as with protein. Our previous study [18] indicated that vaccine approach using nanoemulsion carrying the tumor-specific antigen can be developed to enhance the cellular and humoral immune responses against antigen encapsulated in it. Another work (data unpublished) has shown that nanoemulsion encapsulated MAGE1-HSP70/SEA complex protein vaccine as NE (MHS) produced better MAGE-1-specific cellular immune response and antitumor effect, and the best ratio is 100:1, at which ratio the maximal antitumor effect and the minimal toxicity or tolerance be exerted.

There are profuse lymphatic tissues under the intestinal mucous membrane and vaccine administered orally can elicit both mucous membrane and system immune response simultaneously, leading to the inducement of tumor-specific CTL, therefore the oral route is constituted the preferred immune route for vaccine delivery theoretically [13, 19]. However, for some vaccines, especially protein/peptide vaccines, following peroral administration is mostly impossible, because the enzymatic barriers and absorption barriers imposed by gastrointestinal tract are harder to deliver protein/peptide to APCs successfully. We hypothesized that the novel artificial protein delivery system-nanoemulsion may be used as vehicle to protect complex protein vaccine from enzymatic and absorption barrier of gastrointestinal tract forcefully, accordingly to enhance the immune response. To test this hypothesis, we described the antitumor immune responses induced by NE (MHS) following peroral administration route and compared them with NE (MHS) sc. injection. We attempted to detect the otherwise benefit of this new nanomaterial, and to simplify immune route, imultaneously promote immune effect.

Materials and methods

Animals

The C57BL/6 mice (6–8 week old) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi’an, China). Mice were housed in microisolation in a dedicated, pathogen-free facility, and all animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki or NIH guidelines.

Cell lines

The B16 cell line and the B16-MAGE-1 cell line [45] were conserved in our lab. On the day of tumor challenge, the B16-MAGE-1 cells were harvested and finally resuspended in one time PBS for injection.

Encapsulation of vaccine

The MAGE1-HSP70 fusion protein and SEA was constructed, purified and conserved in our lab. Soybean oil, Pluronic 188 and Span-20 were obtained from Sigma (Sigma Chemicals, Saint-Louis, MO, USA). Water was bidistilled. All chemicals and solvents were used without further purification. MHS nanoemulsion was prepared using magnetic ultrasound method. Briefly, 1.0 ml 0.1% (w/w, 1 mg) MHS protein (The ratio of MAGE1-HSP70 to SEA was 100 mol:1 mol) was added to solution containing 18% (v/v) Pluronic 188 and 8% (v/v) Span-20. Soybean oil 0.6 ml was introduced to this system and mixed, and the oil phase was obtained by adjusting the mixture volume to 2.5 ml with bidistilled water. Afterwards, the oil phase was added dropwise into the 7.5 ml bidistilled water while aqueous phase was stirred under magnetic power (3,000 rpm). Then the mixture was put into the vacuum high-speed sheering emulsification device (FM600, Fluko Inc., Germany), sheared with 23,000 rpm under 0.7 kpa vacuum pressure for 40 min at the temperature no higher than 80°C, followed by process with ultrasound generator (20 kHz, 75 W Cole-Parmer International Inc., USA) at 0°C, 5 min, 3 times. Finally, we got a half-transparent fluid with the concentration of 100 μg/ml MHS. MAGE1-HSP70 and SEA not encapsulated within nanoemulsion were removed by dialyzing using 90 KD dialyser and were quantitated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The encapsulation efficiency was determined by the following formula: Encapsulation efficiency = (Total drug concentration-Free drug concentration)/Total drug concentration × 100%. The morphology of NE (MHS) was evaluated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HITACHI S-520, Tokyo, Japan) observations. Five hundred nanoemulsions were taken for examination of the average size and size distribution. NE (-) was prepared adding 1.0 ml bidistilled water instead of MAGE1-HSP70/SEA complex protein. All products were stored at 4°C before use.

Immunization regime

Thirty-six C57BL/6 mice were divided into six groups: 150 μl/mouse NE (-) via sc. route, 150 μl/mouse NE (-) via po. route, 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse MHS (diluted in PBS) via sc. route, 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse MHS via po. route, 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse NE (MHS) via sc. route, and 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse NE (MHS) via po. route. Each mouse was immunized three times every 10 days. The splenocytes were harvested and pooled 10 days after the boost.

IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay

Mouse IFN-γ ELISpot assay was performed in PVDF-bottomed 96-well plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) by using a murine IFN-γ ELISpot kit (Diaclone, Besancone, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, plates were coated overnight at 4CC with anti-IFN-γ capture antibody and washed three times with PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween20). Plates were blocked for 2 h with 2% skimmed dry milk. Splenocytes of 5 × 105 cells/well were then added together with the indicated number of lethally irradiated (10,000 cGy) B16 or B16-MAGE-1 cells (5 × 104/well, respectively) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Cells were then removed and a biotinylated IFN-γ detection antibody was added for 2 h. Free antibody was washed out, and the plates were incubated with streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at 37°C, followed by extensive washing with PBST, and with PBS. Spots were visualized by the addition of the alkaline phosphatase substrate BCIP/NBT. The number of dots in each well was counted using a dissection microscope. The number of MAGE-1-specific T-cell precursors in splenocytes was calculated by subtracting the IFN-γ+ spots of splenocytes on B16 stimulating cells from that on B16-MAGE-1 cell.

Cytotoxicity assay

The CytoTox 96 non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay (Promega Inc., WI, USA) was performed to determine the cytotoxic activity of the splenocytes in mice vaccinated against B16-MAGE-1 tumor cells, according to the manufacturer’s protocol with minor modification. Briefly, splenocytes of vaccinated mice were cultured in the presence of human IL-2 (40 U/ml) and irradiated B16-MAGE-1 cells. After 3 days, B16 and B16-MAGE-1 target cells were plated at 1 × 104 cells/well on 96-well U-bottomed plates (Costar), then the splenocytes (effector cells) were added in a final volume of 100 μl at 1:5, 1:20 and 1:80 ratio, respectively. The plates were incubated for 45 min in a humidified chamber at 37°C, 5% CO2, and centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min. 50 μl aliquots were transferred from all wells to a fresh 96-well flat-bottom plate, and an equal volume of reconstituted substrate mix was added to each well. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and protected from light. Then 50 μl stop solution was added, and the absorbance values were measured at 492 nm. The percentage of cytotoxicity for each effector:target cell ratio was calculated from the equation: [A (Experimental) − A (Effector Spontaneous) − A (Target Spontaneous)] × 100/[A (Target maximum) − A (Target spontaneous)]. Percentage of MAGE-1-specific lysis was calculated by subtracting the lysis percentage of splenocytes on B16 from that on B16-MAGE-1 target cells.

In vivo tumor treatment experiment

Thirty-six mice were sc. challenged with B16-MAGE-1 tumor cells (1 × 105 cells/mouse, respectively) in the right legs (D0). Seven days later (D7), all mice were randomly divided into six groups (six per group): 150 μl/mouse NE (-) via sc. route, 150 μl/mouse NE (-) via po. route, 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse MHS via sc. route, 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse MHS via po. route, 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse NE (MHS) via sc. route, and 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse NE (MHS) via po. route, and were vaccinated the first time. One week (D14) and 2 weeks (D21) later, these mice were immunized with the same regime as the first vaccination. Tumor volumes (length × width2 × π/6) were measured for each individual mouse and were plotted as the mean tumor volume of the group (±SEM) versus the days post tumor planted. Once tumors became palpable, measurements were taken twice a week.

Tumor challenge assay

Sixty mice (ten per group) were vaccinated respectively with 150 μl/mouse NE (-) via sc., NE (-) via po., 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse MHS via sc., MHS via po., 150 pmol/150 μl/mouse NE (MHS) via sc., or NE (MHS) via po. route. After 1 and 2 weeks, the immunization regime was repeated 2 times. On the eighth day after the last immunization (D0), all mice were sc. challenged with B16-MAGE-1 tumor cells (1 × 105 cells/mouse, respectively) in the right legs. Once tumors became palpable, observations were taken twice a week. The ratio of tumor-free mice was recorded and Kaplan–Meier curves were generated.

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA was performed to determine differences of immune response among the various immunization groups. Newman–Keuls tests were preformed as post hoc analysis for one-way ANOVA. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of nanovaccine

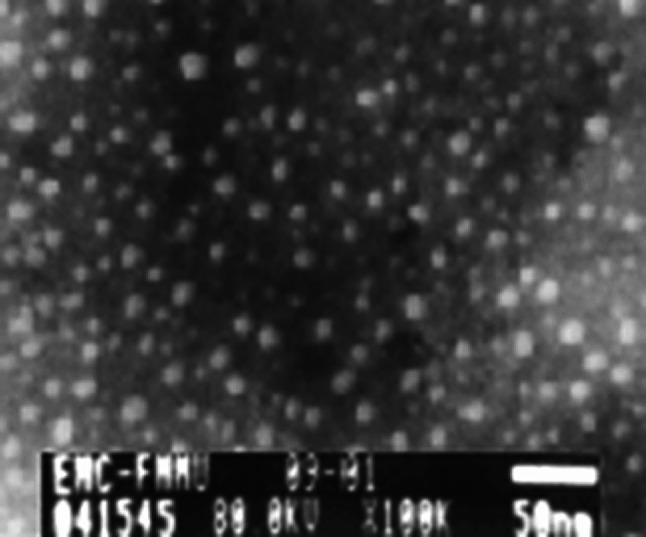

NE (MHS) was a milkiness translucent equal colloid. Transmission electron microscopy showed that the nanovaccine was sphericity, and the average diameter was 20 ± 5 nm, as shown in Fig. 1. There was no delamination even after they were kept undisturbed at room temperature for a period of 6 months or centrifugating at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. The encapsulation efficiency was 87%.

Fig. 1.

The photo of nanoemulsion taken by transmission electron microscope (100,000×). One drop of diluted NE (MHS) nanovaccine (1:100) was dropped onto copper sieve, stained by 0.3% tungsten phosphate, and then observed under TEM when it dried. The vesicles in nanoemulsion showed approximately global shape with similar diameter, ranging from 15 to 25 nm

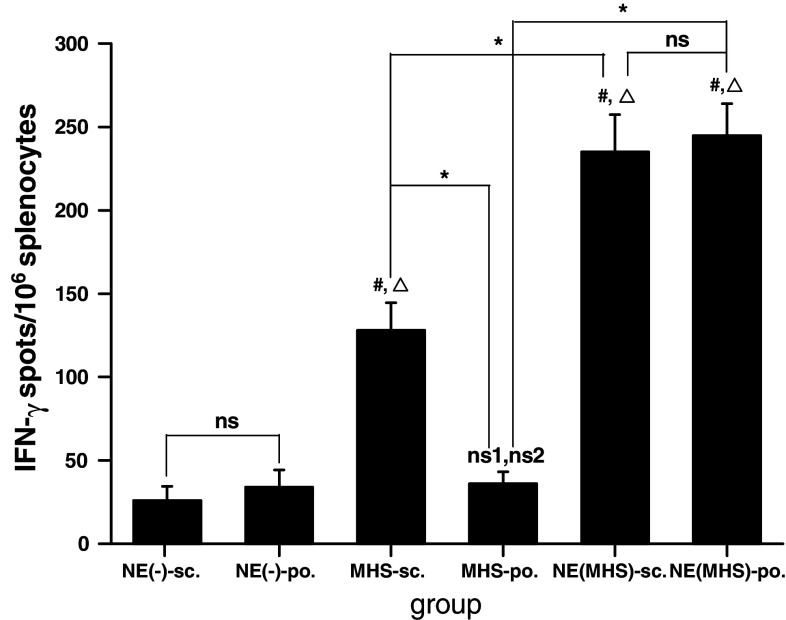

The MAGE-1-specific T-cell-mediated immune responses induced by vaccination with the NE (MHS) following peroral administration route

The CD8+ CTL is one of the most crucial components among antitumor effectors [28]. To determine the MAGE-1-specific CD8+ T-cell precursor frequencies generated by NE (MHS) following po. route, ELISpot and cytotoxicity assays were performed. ELISpot is a sensitive functional assay used to measure IFN-γ production at the single cell level. As shown in Fig. 2, the numbers of spot-forming T-cell precursors specific for MAGE-1 in the splenocytes from mice po. or sc. vaccinated with NE (MHS) were about one time statistical greater than that from mice sc. injected with MHS alone, and five and more times greater than NE (-)-sc., NE (-)-po. and MHS-po. group. The level of MAGE-1—specific IFN-γ—producing T cells/106 splenocytes derived from mice sc. injected with MHS complex protein vaccine were 2–3 times greater than that from mice peroral administrated with MHS alone and sc./po. vaccined with NE (-). Compared with the NE (MHS)-sc. group, the numbers of IFN-γspots/106 splenocytes from the mice of NE (MHS)-po. group were no significant difference.

Fig. 2.

ELISpot assay of MAGE-1-specific T-cell precursors from the splenocytes of vaccinated mice. C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated with NE (-), MHS or NE (MHS) via sc. or po., respectively. Each mouse was immunized three times every 10 days. Mice were terminated on tenth day after the last immunization and splenocytes were isolated. Data shown represent averaged results obtained from six mice ± SEM. All analyses were done in duplicates. One-way ANOVA was performed for statistical analysis. ns denotes no significantly difference between the two groups. ns1 denotes no significantly difference from NE (-)-sc. group. ns2 denotes no significantly difference from NE (-)-po. group. A value P < 0.05 was considered significant. # denotes significantly different from NE (-)-sc. group, Δdenotes significantly different from NE (-)-po. group, and * denotes significantly difference between the two groups

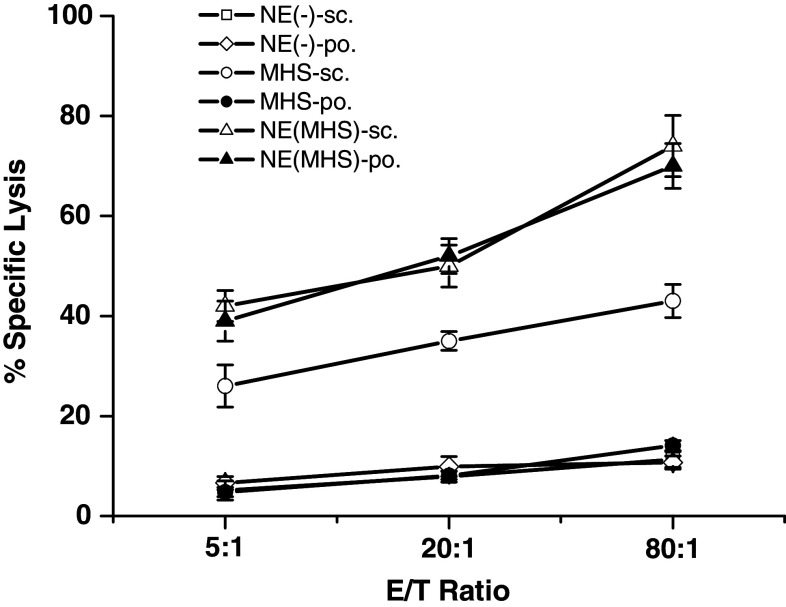

We also performed cytotoxicity assays to determine the MAGE-1-specific lysis of MAGE-1-expressing cells by CTLs induced by vaccination with NE (MHS) via peroral route. As shown in Fig. 3, the MAGE-1-specific lysis of CTLs from mice sc./po. vaccinated with NE (MHS) was greater than that from mice sc. injected with MHS alone, and the latter was significantly higher than that of peroral administrated with MHS or sc./po. vaccinated with NE (-). Moreover, there were no statistical difference between NE (MHS)-sc. and NE (MHS)-po. group. The same results were observed between any two ones of NE (-)-sc., NE (-)-po. and MHS-po. group. The results were consistent with the data from ELISpost.

Fig. 3.

MAGE-1-specific lysis against B16-MAGE-1 cells by CTLs induced by vaccination with NE (MHS) via peroral immunization route. Mice were vaccinated as described in the Fig. 2. The splenocytes of mice were harvested and restimulated with irradiated B16-MAGE-1 cell. The percentage of specific lysis of CTLs on B16-MAGE-1 target cells was determined by a cytotoxicity assays. The percentage of MAGE-1-specific lysis was calculated by subtracting the percentage lysis of CTLs on B16 from that on B16-MAGE-1 target cells. Data shown represent average results obtained from six mice ± SEM. All analyses were done in duplicates. The MAGE-1-specific lyses of CTLs from mice sc. and po. vaccinated with NE (MHS) was the highest two in six groups, and those sc. vaccinated with MHS protein alone were higher than NE (-)-sc., NE (-)-po., and MHS-po. group. Moreover, there was no statistical difference of the MAGE-1-specific lysis of CTLs between NE (MHS)-sc. and NE (MHS)-po. group

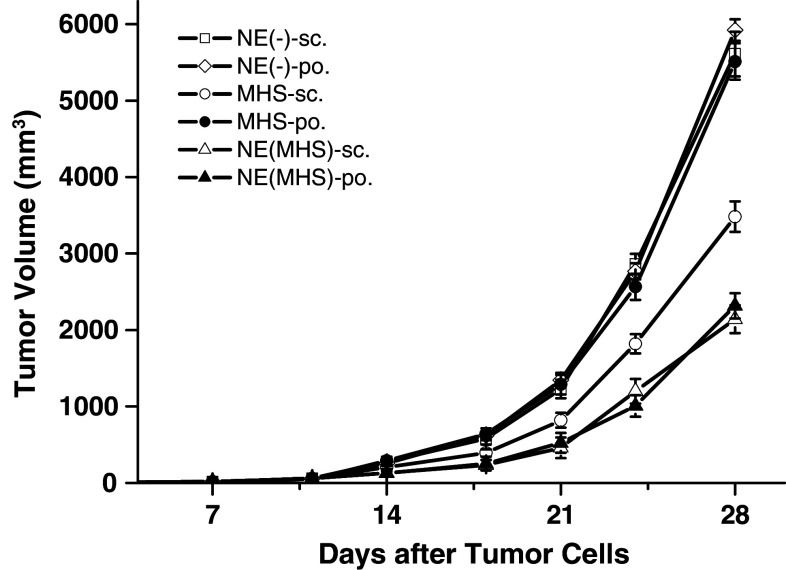

The treatment effect of NE (MHS) vaccination following peroral administration route

Thirty-six C57BL/6 mice were sc. challenged with B16-MAGE-1 tumor cells in the right legs. One week later, tumor masses could be touched in 86.11% mice and all mice were randomly divided into six groups and the mice were vaccinated 3 times according to the different regimes respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, from 14 days, especially 18 days after the B16-MAGE-1 tumor challenge, compared with peroral administration with MHS or sc./po. with NE (-), sc./po. with NE (MHS) or sc. with MHS significantly delayed tumor growth in B16-MAGE-1 tumor model, and there were no statistical differences between NE (MHS)-sc. and NE (MHS)-po. group. Compared with the forenamed two NE (MHS) groups, the mean tumor volume in MHS-sc. group was significantly larger at any observation point. For example, when the average tumor volumes in the NE (-)-sc./po. and MHS-po. mice had reached about 5,500 mm3 on 28 days after the B16-MAGE-1 tumor challenge, it was 2,141, 2,315 and 3,488 mm3 in the NE (MHS)-sc., NE (MHS)-po. and MHS-sc. vaccination, respectively.

Fig. 4.

The immunotherapy effect of challenged B16-MAGE-1 melanoma with the tumor vaccine. Mice were sc. inoculated with B16-MAGE-1 tumor cells (1 × 105 cells/mouse, respectively). Seven days later, they were randomly divided into six groups (n = 6 mice/group) and vaccinated as described in the Fig. 2. Data presented are mean ± SEM. Vaccination with NE (MHS), whether via sc. route or po. route, significantly delayed tumor growth compared with vaccination using MHS or NE (-), and there were no statistical differences between NE (MHS)-sc. and NE (MHS)-po. group at the observation points

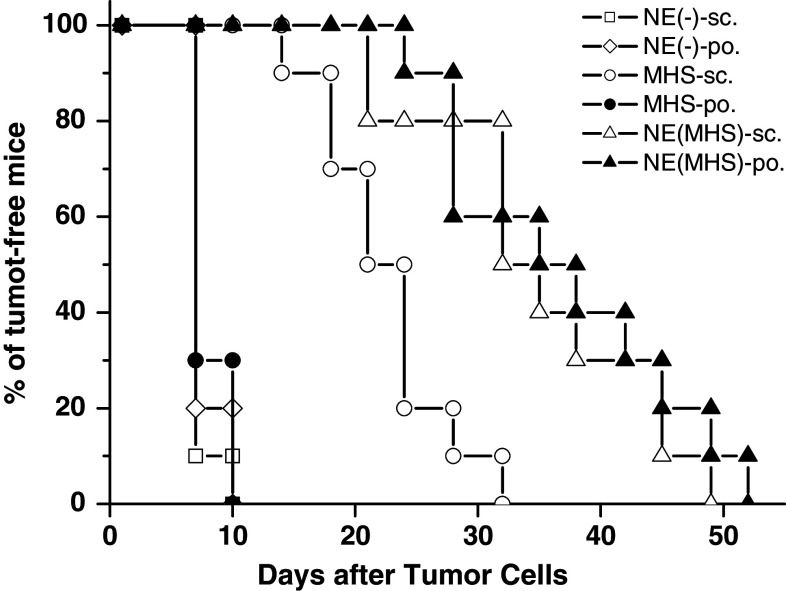

The protection effect of NE (MHS) vaccination following peroral administration route

To test the protection effect of the NE (MHS) administrated via peroral route, in vivo tumor challenge experiments were performed. The tumor-free mice were recorded as the percentage of mice surviving from tumor after the tumor challenge. As shown in Fig. 5, from 7 days after the B16-MAGE-1 tumor challenge, compared with vaccination using NE (-)-sc./po. and MHS orally, sc. vaccination with the MHS and sc./po. administration with NE (MHS) nanovaccine could significantly delay the tumor occurrence in B16-MAGE-1 tumor model. Moreover, we found the ratio of the tumor-free mice at the observation points in the NE (MHS)-po. group was almost same to that in the NE (MHS)-sc. group and both of them were significant higher than that in the MHS-sc. group.

Fig. 5.

The preventive effect of challenged B16-MAGE-1 melanoma with the tumor vaccine (n = 10 mice/group). The tumor-free rates of C57BL/6 mice inoculated with NE (MHS) vaccine via different routes showed no statistical differences at anytime of observation after tumor cells. Compared with the mice of the other groups, the tumor occurrence time was significantly suspended in the mice sc. or po. vaccinated with NE (MHS) nanovaccine

Discussion

In this study, we successfully encapsulated MAGE1-HSP70 and SEA complex protein vaccine in nanoemulsion, which was of uniform and nanometer-level size, high stability and encapsulation efficiency. When immunization with NE (MHS) nanoemulsion vaccine, compared with sc. group, we did not found any statistical significance in po. group both in cellular immune responses against MAGE-1 and in treatment or protection effect, but MHS unencapsulated administration orally could not elicit the homologous antitumor immune responses to that via sc. injection. Therefore, the nanoemulsion carrier we found is important implication for tumor therapy and prevention.

In fact, the oral delivery of labile drugs is becoming the focus of growing attention, particularly as many of the new therapeutic agents in development are hydrophilic drugs such as protein/peptide or oligonucleotides. Since parenteral drug administration especially in chronic conditions is not well accepted by patients and may lead to issues with compliance [13, 19, 44]. Besides that, some novel and charming researches have shown that there are profuse lymphatic tissues under the intestinal mucous membrane and vaccine administered orally can elicit both mucous membrane and system immune response simultaneously, leading to a inducement of tumor-specific CTL, so the oral route is constituted the preferred immune route for vaccine delivery theoretically [13, 19]. But due to the the poor bioavailability, numerous vaccines, especially protein/peptide vaccines following peroral administration were impossible. One major barrier of this limitation is the potential for antigen degradation in the gastrointestinal tract prior to immune priming, and other reasons include: (1) low mucosal bioadhesion for the vaccine, (2) permeability restricted to a region of the gastrointestinal tract, (3) low or very low solubility of the compound which results in low dissolution rate in the mucosal fluids and elimination of a fraction of the drug from the alimentary canal prior to absorption. Those barriers make orally delivery peptide/protein to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) ineffective [13, 19, 38, 44].

In order to circumvent those analogous problems of the peptide/protein drug, researchers have attempted to associate drugs with nanoparticulate systems (or small particles in the micrometre size range). And different oral administration experiments on animals have been reported that nanoparticulate systems helped to improve the pharmacokinetics of several drugs [1–4, 9–12, 20, 24, 27, 32], suggesting a high potential of nanoparticles as peroral drug delivery system [34]. For instance, the studies reported that insulin incorporated into nanocapsules of poly (isobutyl cyanoacrylate) is unlikely to be degraded by gastrointestinal tract enzymes and therefore decreased glycemia by 50% in diabetic rats, which would otherwise be achieved through traditional oral administration [10, 11]. Data obtained after oral immunization by microencapsulated antigens have been reviewed by Mutwiri et al. [29]. In general, ovalbumin, peptides, bacterial toxoids, inactivated bacteria, and DNA plasmids entrapped in PLGA microparticles was proved well protected from degradation by digestive enzymes and induced both mucosal and systemic immune responses following oral or intragastric administration [5, 15, 22, 23, 26].

To date, nanometer-sized drug delivery system is becoming a focus as a delivery formulation for peptide/protein and DNA drugs because it can protect labile drugs, increase drug solubility and bioavailability, control drug release and improve the bioadhesion and biopermesability when via po. administration [17, 34]. Nanoemulsion is a system of water, oil and amphiphile, which is a single optically isotropic and thermodynamically stable liquid solution smaller (diameter is 1–100 nm) but more efficient. In particular, nanoemulsion has become an important choice of protein/peptide antigen drug delivery system because of its long circulation time and propensity to be phagocytosed more efficiently by antigen presenting cells to induce immune response [30, 43]. Moreover, nanoemulsion of 100 nm diameter can be phagocytosed by reticulo-endothelial system from the blood, and that of 50 nm diameter or less can easily cross hepatic endothelium, reach spleen and bone marrow through lymphatic, and even reach tumor. Furthermore, it is good for iv. ia. ip. or po. [21, 30, 43]. But up to now, the nanoemulsion as the carrier of the tumor protein vaccine following peroral administration route was rarely reported. In our present study, we used this novel artificial drug delivery system as vehicle of oral tumor protein vaccine in order to exert nanoemulsion’s excellent biocharacteristics, further stirred both mucous membrane and system immune response simultaneously and accordingly enhanced the immune response.

Indeed, our present research indicated that MHS, only using nanoemulsion as vehicle, immunization through the po. and sc. route did not produce significant difference both in cellular immune responses against MAGE-1 and in treatment and protection effect. This result suggested that it is nanoemulsion, which makes the protein tumor vaccine administration orally doable. Except the characteristics of the nano-delivery system, we speculated several conceivable reasons.

First, nanoemulsion can protect protein vaccine successfully incorporated into the dispersed aqueous phase of w/o microemulsion droplets where they are afforded some protection from enzymatic degradation when administered orally [36, 37]. Furthermore, the presence of surfactant and in some cases cosurfactant, for example, medium chain diglycerides in many cases served to increase membrane permeability thereby increasing drug uptake [6–8, 35, 36, 40, 41].

Moreover, nanoemulsion can facilitate APCs uptaking tumor antigen. When nanoemulsion vaccine administered orally, lymphatic uptake [33] by the M cells of the Peyer’s patches appeared to be a major site of translocation [31], and subsequent passage of nanoemulsion into mesenteric lymph nodes seems to be attributable to an uptake by macrophages [14]. In addition, the nanoemulsion delivery system is characterized by passive targeting to lymphatic tissues, long circulation time and sustained-release the tumor antigen inside it, which facilitating tumor antigens uptaked efficiently and adquately.

Although the fact of nanoemulsion as a carrier endowing the tumor protein vaccine some new uses and merits is unassailable, the mechanisms for undiminished immune response to MAGE-1 induced by NE (MHS) orally administration is not entirely clear and need be further studied. Additionally, we only found the protein vaccine following peroral administration route using nanoemulsion as delivery carrier can induce the same, but not stronger antitumor immune response to following NE (MHS) subcutaneous injection. But we think the oral nanovaccine might have a broad application in tumor protein vaccine. Because oral vaccination, compared to systemic administration, would avoid pain and risks of infection associated with injections, lead lower costs and make large-population immunization more feasible. Even though, more attempts on the modification of this oral nanovaccine to gain stronger antitumor immune response are still necessary in the future.

Besides, this protein nanovaccine was designed for human cancer immunotherapy. To support further clinical investigation in human body, we set up the mouse model using human MAGE gene transfection. Also we have used this model in several provious studies and obtained solid antitumor immunity [18, 25, 45]. We think the current model is acceptable in testing human antigen induced tumor rejection in mouse.

In summary, the NE (MHS) nanovaccine can induce stronger cellular response and enhance more significant potency against the MAGE-1-expressing tumor than MHS complex protein alone. Moreover, the peroral administration of NE (MHS) could induce approximately similar antitumor immune responses to that via sc. route, but MHS unencapsulated administration orally could only elicit antitumor immune responses same to NE (-) control groups, suggesting nanoemulsion as a promising carrier make the tumor protein vaccine immunizing via po. feasible and effective. It might have a broad application in tumor protein vaccine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from China National Natural Science Foundation (No. 30271464, No. 30700994).

Abbreviations

- APCs

Antigen-presenting cells

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- HPLC

High performance liquid chromatography

- HSP

Heat shock protein

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- MAGE

Melanoma associated antigen

- MHS

MAGE1-HSP70/SEA complex protein

- NE

Nanoemulsion

- NE (-)

Nanoemulsion-encaupulated nothing

- NE (MHS)

Nanoemulsion-encaupsulated (MAGE1-HSP70/SEA complex protein)

- po.

Peroral

- sc.

Subcutaneous

- SEA

Staphylococcal enterotoxins A

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- TSA

Tumor-specific antigen

References

- 1.Alpar HO, Field WN, Hayes K, Lewis DA. A possible use of orally administered microspheres in the treatment of inflammation. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1989;41(Suppl):50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammoury N, Fessi H, Devissaguet JP, Dubrasquet M, Benita S. Jejunal absorption, pharmacological activity, and pharmacokinetic evaluation of indomethacin-loaded poly(d,l-lactide) and poly(isobutyl-cyanoacrylate) nanocapsules in rats. Pharm Res. 1991;8:101. doi: 10.1023/A:1015846810474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck PH, Kreuter J, Müller WEG, Schatton W. Improved peroral delivery of avarol with polyalkylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1994;40:134. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonduelle S, Carrier M, Pimienta C, Benoit JP, Lenaerts V. Tissue concentration of nanoencapsulated radiolabelled cyclosporin following peroral delivery in mice or ophthalmic applications in rabbits. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1996;42:313. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challacombe SJ, Rahman D, O’Hagan DT. Salivary, gut, vaginal and nasal antibody responses after oral immunization with biodegradable microparticles. Vaccine. 1997;15:169. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinides PP, Lancaster CM, Marcello J, Chiossone DC, Orner D, Hidalgo I, Smith PL, Sarkahian AB, Yiv SH, Owen AJ. Enhanced intestinal absorption of an RGD peptide from water-in-oil microemulsions of different composition and particle size. J Control Rel. 1995;34:109. doi: 10.1016/0168-3659(94)00129-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Constantinides PP. Lipid microemulsions for improving drug dissolution and oral absorption: physical and biopharmaceutical aspects. Pharm Res. 1995;12:1561. doi: 10.1023/A:1016268311867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Constantinides PP, Scalart JP, Lancaster S, Marcello J, Marks G, Ellens H, Smith PL. Formulation and intestinal absorption enhancement evaluation of water-in-oil microemulsions incorporating medium-chain glycerides. Pharm Res. 1994;11:1385. doi: 10.1023/A:1018927402875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damgé C, Aprahamian M, Balboni G, Hoeltzel A, Andrieu V, Devissaguet JP. Polyalkylcyanoacrylate nanocapsules increase the intestinal absorption of a lipophilic drug. Int J Pharm. 1987;36:121. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(87)90146-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damgé C, Michel C, Aprahamian M, Couvreur P, Devissaguet JP. Nanocapsules as carriers for oral peptide delivery. J Control Release. 1990;13:233. doi: 10.1016/0168-3659(90)90013-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damgé C, Michel C, Aprahamian M, Couvreur P. New approach for oral administration of insulin with polyalkylcyanoacrylate nanocapsules as drug carrier. Diabetes. 1988;37:246. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.37.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damgé C, Vonderscher J, Marbach P, Pinget M. Poly(alkyl cyanoacrylate) nanocapsules as a delivery system in the rat for octreotide, a long-acting somatostatin analogue. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:949. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.des Rieux A, Fievez V, Garinot M, YJs Schneider, Préat V. Nanoparticles as potential oral delivery systems of proteins and vaccines: a mechanistic approach. J Control Release. 2006;116:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devissaguet JP, Fessi H, Ammoury N, Barratt G (1992) Colloidal drug delivery systems for gastrointestinal application, In: Junginger HE (eds) Drug Targeting and Delivery-Concepts in Dosage Form Design, Ellis Horwood, New York, 71

- 15.Esparza I, Kissel T. Parameters affecting the immunogenicity of microencapsulated tetanus toxoid. Vaccine. 1992;10:714. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(92)90094-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleischer B, Schrezenmeier H. T cell stimulation by staphylococcal enterotoxins Clonally variable response and requirement for major histocompatibility complex class II molecules on accessory or target cells. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1697. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.5.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galindo-Rodriguez SA, Allemann E, Fessi H, Doelker E. Polymeric nanoparticles for oral delivery of drugs and vaccines: a critical evaluation of in vivo studies. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carr Syst. 2005;22:419. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v22.i5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge W, Sui YF, Wu DC, Sun YJ, Chen GS, Li ZS, Si SY, Hu PZ, Huang Y, Zhang XM. MAGE-1/Heat shock protein 70/MAGE-3 fusion protein vaccine in nanoemulsion enhances cellular and humoral immune responses to MAGE-1 or MAGE-3 in vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:841. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0073-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamman JH, Enslin GM, Kotzé AF. Oral delivery of peptide drugs: barriers and developments. BioDrugs. 2005;19:165. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200519030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hubert B, Atkinson J, Guerret M, Hoffman M, Devissaguet JP, Maincent P. The preparation and acute antihypertensive effects of a nanocapsular form of darodipine, a dihydropyridine calcium entry blocker. Pharm Res. 1991;8:734. doi: 10.1023/A:1015897900363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jores K, Mehnert W, Drechsler M, Bunjies H, Johann C, Mader K. Investigations on the structure of solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and oil-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles by photon correlation spectroscopy, field-flow fractionation and transmission electron microscopy. J Control Release. 2004;95:217. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung T, Kamm W, Breitenbach A, Hungerer KD, Hundt E, Kissel T. Tetanus toxoid loaded nanoparticles from sulfobutylated poly(vinyl alcohol)-graft-poly(lactide-co-glycolide): evaluation of antibody response after oral and nasal application in mice. Pharm Res. 2001;18:352. doi: 10.1023/A:1011063232257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SY, Doh HJ, Jang MH, Ha YJ, Chung SI, Park HJ. Oral immunization with Helicobacter pylori-loaded poly(d, l-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles. Helicobacter. 1999;4:33. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.09046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maincent P, Le Verge R, Sado P, Couvreur P, Devissaguet JP. Deposition kinetics and oral bioavailability of vincamine-loaded polyalkyl cyanoacrylate nanoparticles. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75:955. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600751009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma JH, Sui YF, Ye J, Huang Ya-Yu, Li Zeng-Shan, Chen Guang-Sheng, Qu Ping, Song Hong-Ping, Zhang Xiu-Min. Heat shock protein 70/MAGE-3 fusion protein vaccine can enhance cellular and humoral immune responses to MAGE-3 in vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:907. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0660-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maloy KJ, Donachie AM, O’Hagan DT, Mowat AM. Induction of mucosal and systemic immune responses by immunization with ovalbumin entrapped in poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles. Immunology. 1994;81:661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathiowitz E, Jacob JS, Jong YS, Carino GP, Chickering DE, Chaturvedi P, Santos CA, Vijayaraghavan K, Montgomery S, Bassett M, Morell C. Biologically erodible microspheres as potential oral drug delivery systems. Nature. 1997;386:410. doi: 10.1038/386410a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melief CJ, Kast WM. T-cell immunotherapy of tumors by adoptive transfer of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and by vaccination with minimal essential epitopes. Immunol Rev. 1995;145:167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1995.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mutwiri G, Bowersock TL, Babiuk LA. Microparticles for oral delivery of vaccines. Expert Opin Drug Del. 2005;2:791. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niidome T, Huang L. Gene therapy progress and prospects: nonviral vectors. Gene Ther. 2002;9:1647. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Hagan DT. Intestinal translocation of particulates—implications for drug and antigen delivery. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1990;5:265. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(90)90020-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ottenbrite R, Zhao R, Milstein S. A new oral microsphere drug delivery system. Macromol Symp. 1996;101:379. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pappo J, Ermak TH. Uptake and translocation of fluorescent latex particles by rabbit Peyer’s patch follicle epithelium: a quantitative model for M cell uptake. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;76:144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponchel G, Irache JM. Specific and non-specific bioadhesive particulate systems for oral delivery to the gastrointestinal tract. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1998;34:191. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(98)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pouton CW. Formulation of self-emulsifying drug delivery systems. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1997;25:47. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(96)00490-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarciaux JM, Acar L, Sado PA. Using microemulsion formulations for drug delivery of therapeutic peptides. Int J Pharm. 1995;120:127. doi: 10.1016/0378-5173(94)00386-J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Storni T, Kundig TM, Senti G, Johansen P. Immunity in response to particulate antigen-delivery systems. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2005;57:333. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Streatfield SJ. Mucosal immunization using recombinant plant-based oral vaccines. Methods. 2006;38:150. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudo T, Kuramoto T, Komiya S, Inoue A, Itoh K. Expression of MAGE genes in osteosarcoma. J Orthop Res. 1997;15:128. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swenson EC, Curatolo WJ. Intestinal permeability enhancement for proteins, peptides and other polar drugs: mechanisms and potential toxicity. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1992;8:39. doi: 10.1016/0169-409X(92)90015-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swenson ES, Milisen WB, Curatolo W. Intestinal permeability enhancement: efficacy, acute local toxicity and reversibility. Pharm Res. 1994;11:1132. doi: 10.1023/A:1018984731584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torres BA, Kominsky SL, Perrin GQ, Hobeika AC, Johnson HM. Superantigens: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226:164. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vinogradov SV, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV. Nanosized cationic hydrogels for drug delivery: Preparation, properties and interactions with cells. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2002;54:135. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vyas SP, Gupta PN. Implication of nanoparticles/microparticles in mucosal vaccine delivery. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2007;6:401. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye J, Chen GS, Song HP, Li ZS, Huang YY, Qu P, Sun YJ, Zhang XM, Sui YF. Heat shock protein 70/MAGE-1 tumor vaccine can enhance the potency of MAGE-1-specific cellular immune responses in vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:825. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0536-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]