Abstract

This study was undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness and mechanisms of anti-tumor activity of Baker’s yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, in immunocompetent mice. Swiss albino mice were inoculated intramuscularly in the right thigh with Ehrlich Ascites Carcinoma (EAC) cells. At day 8, mice bearing Solid Ehrlich Carcinoma tumor (SEC) were intratumorally (IT) injected with killed S. cerevisiae (10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells) for 35 days. Histopathology of yeast-treated mice showed extensive tumor degeneration, apoptosis, and ischemic (coagulative) and liquefactive necrosis. These changes are associated with a tumor growth curve that demonstrates a significant antitumor response that peaked at 35 days. Yeast treatment (20 × 106 cells) three times a week resulted in a significant decrease in tumor volume (TV) (67.1%, P < 0.01) as compared to PBS-treated mice. The effect was determined to be dependent on dose and frequency. Yeast administered three and two times per week induced significant decrease in TV as early as 9 and 25 days post-treatment, respectively. Administration of yeast significantly enhanced the recruitment of leukocytes, including macrophages, into the tumors and triggered apoptosis in SEC cells as determined by flow cytometry (78.6%, P < 0.01) at 20 × 106 cells, as compared to PBS-treated mice (42.6%). In addition, yeast treatment elevated TNF-α and IFN-γ plasma levels and lowered the elevated IL-10 levels. No adverse side effects from the yeast treatment were observed, including feeding/drinking cycle and life activity patterns. Indeed, yeast-treated mice showed significant final body weight gain (+21.5%, P < 0.01) at day 35. These data may have clinical implications for the treatment of solid cancer with yeast, which is known to be safe for human consumption.

Keywords: Ehrlich carcinoma, S. cerevisiae, Apoptosis, In vivo, Cytokine

Introduction

Immune modulation and apoptosis are currently receiving great attention as major treatment modalities for the treatment of cancer. Immunotherapy, using biological response modifiers (BRMs), was designed to activate the host immune response to kill cancer cells. Suppression of tumor cell growth was achieved upon stimulation of one or more arms of the immune system such as NK cells [30, 34], CTL [3], macrophages [44, 74] and several cytokines [51, 63, 75]. Apoptosis is an orchestrated form of cell death in which cells commit suicide. It is a gene-regulated pathway to eliminate cells without the initiation of inflammation [2, 37]. The apoptotic cell death program is executed by the activation of intracellular proteinases, caspases, which are synthesized as inactive proenzymes and are activated to exert their role. Although anticancer drug therapies induce apoptosis in cancer cells, they are mostly toxic [48, 50, 61, 62]. Similarly, BRMs that are used for immunomodulation, including IL-2, IL-12, IL-15 and interferons [6, 8, 9, 27, 71], have limited success due to toxicity. Therefore, the search for new cancer therapies with minimal or no side-effects is greatly needed. Several natural products of this sort have been developed, including: (1) MGN-3/Biobran, an arabinoxylan rice bran [13] that exhibits anticancer activity via induction of NK cell activity [14–16] and cytokine production [23, 24]; (2) green tea that contains biologically active flavonoids, catechins, that exhibit inhibition of angiogenesis [59], free radical formation and lipid peroxidation [36, 42]; (3) dietary genistein, a natural isoflavone compound found in soybeans that exhibits anticancer activity [41, 73] by mechanisms that include inhibition of angiogenesis [11] and induction of apoptosis [76]; and (4) the anticancer properties of the supplemental vitamin E [α-tocopherol (α-TOH)] and its derivatives have been well-documented [47, 52] and include induction of cancer cell apoptosis [38], NK activation [29] and antioxidant action [56].

In this study, we utilize the Baker’s and brewer’s yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a potent anticancer agent; it is known to be safe, economical, and acceptable for human consumption. It is a commercially available food supplement and a necessary component for the production of fermented foods (such as bread and beer). Our previous data demonstrate that human solid cancer cells (breast, tongue and colon) undergo apoptosis upon phagocytosis of killed S. cerevisiae in vitro [18–20, 22]. In addition, yeast induced apoptosis in nude mice bearing human breast cancer in vivo [17, 25]. In this study, we evaluate the impact of injecting yeast on the immune system by studying the effectiveness of intratumoral (IT) injection of S. cerevisiae using immunocompetent mouse, Swiss albino, bearing Ehrlich Carcinoma. Results revealed that S. cerevisiae, the baker’s yeast, suppresses the growth of Ehrlich carcinoma-bearing mice. The mechanisms underlying the effect of yeast may involve both apoptotic and immunomodulatory effects of S. cerevisiae. These data may have clinical implications for the treatment of solid cancer.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female Swiss albino mice (2 months old) weighing 19–21 g were used in this study. Mice were housed five per cage at constant temperature (24 ± 2°C) with alternating 12 h light and dark cycles. Mice were fed standard cube pellets and water ad libitum and were accommodated for 1 week prior to experiments. The diet consisted of casein (12.5%), fats (1.0%), wheat flour (80%), bran (3.3%), olive oil (2.3%), dl-methionine (0.5%), vitamins and salt mixture (0.2%) and water (0.2%). The actual food intake was previously monitored and found to be from 4 to 5 g/day/animal weighing (20 ± 2 g).

Ehrlich ascites carcinoma (EAC)

EAC was kindly supplied by the National Cancer Institute, Cairo University, Egypt, and was maintained by weekly intraperitoneal transplantation of 2.5 × 106 cells in female mice.

Preparation of S. cerevisiae

Commercially available baker’s and brewer’s yeast, S. cerevisiae, was used in suspensions that were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). It was then incubated for 1 h at 90°C to kill the yeast and washed two times with PBS. Quantification was carried out using a hemocytometer, and cell suspensions were adjusted to 1 × 108 cells/ml. The yeast was given locally to mice-bearing SEC with 0.1 ml/mouse three times a week for 25 days starting from day 8 of tumor cell inoculation.

Experimental design and tumor transplantation

Tumor transplantation

Forty-one mice were inoculated intramuscularly with 0.2 ml EAC cells (2.5 × 106 cells) in the right thigh of the lower limb at day 0. At 8 days post-tumor cell inoculation, mice bearing a solid SEC tumor mass of ∼100 mm3 were randomly divided into three groups: (1) mice receiving IT injections of PBS (n = 13), (2) mice receiving IT injections of yeast 10 × 106 cells and (3) mice receiving IT injections of yeast 20 × 106 cells (n = 14/group). Yeast injections commenced on day 8 post EAC cell inoculation with continued treatment three times a week for 25 days. Ten animals were kept untreated as the control group for monitoring animal survival. Antitumor activity was assessed at different time intervals by measuring changes in tumor volume (mm3) during the experimental time course. A Vernier caliper was used to collect tumor size data that was plugged into the following formula: TV (mm3) = 0.52 AB 2, where A is the minor axis and B is the major axis. On day 35, mice were sacrificed under light ether anesthesia and blood was removed by direct cardiac puncture using heparinized syringes. The separated plasmas were used for cytokine production analysis and solid tumor tissues were excised and used for tumor weight determination, apoptosis and histopathological studies.

Effect of lower overall dose of yeast injection (10 injections)

Another set of experiments was carried out to examine the effect of lower overall dose of yeast injection (10 × 106 cells) on tumor volume. The protocol of experimental design and tumor transplantation previously mentioned above was followed, except that yeast injection was carried out twice a week and commenced at day 11 of tumor cells inoculation to day 35 (n = 10/group). Changes in tumor volume (TV) were compared with controls bearing SEC tumor and receiving IT injections of PBS at the corresponding time point.

Body weight (BW) changes

Control and yeast-treated mice bearing tumor (injected 3 times/week) were examined for BWs (initial, final and net BWs) at day 35. The net final body weight = Final body weight − Tumor weight.

Histopathological studies

Studies were carried out under a light microscope to evaluate the histopathology changes including apoptotic figures in the tumor-bearing mice treated with yeast (3 times/week) or PBS. At day 35 post-tumor cell inoculation, 2 days past the last yeast injection, animals were killed, tumors were removed, and the tumor tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 h, processed for paraffin sections (4 μm thickness) and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and special stain (PAS).

Apoptosis

Flow cytometry analysis was used to measure the percentage of apoptotic cancer cells in SEC tumor-bearing mice treated IT 3 times/week with PBS and with two different concentrations of yeast (10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells). Dead cells were detected by fluorescein-conjugated annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) technique (Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit, BioVision Research Products, Mountain View, CA, USA). Cells in suspension were prepared as described [68]. Cells were acquired by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed by Cell-Quest software.

Cytokine analysis

Plasma samples collections

Plasma samples were collected on day 35 post tumor cell inoculation from four animal groups: control mice and three groups of SEC-bearing mice IT treated with PBS and yeast (3 times/week) at low and high concentrations. Animals were fasted for 16 h before sampling.

Cytokine concentrations in plasma

Plasma tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) levels were measured via mouse cytokine specific ELISA kits provided by CytImmune Sciences Inc (Rockville, MD, USA) on day 35, post tumor cell inoculation.

Adverse effects of yeast (toxicity)

Animals were monitored to observe potential toxic side effects of yeast treatment. Mice were examined for the following: (a) changes in feeding/drinking and life activity patterns were recorded daily; (b) changes in body weight were recorded weekly; and (c) animal survival for the course of the experiment (35 days).

Statistical analysis

Student’s t test was used for the evaluation of the TV changes of the lower overall dose of yeast injection. All other data were analyzed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc tests for multiple comparisons and expressed as mean ± SE of the mean. Differences were considered significant at the P < 0.05 level.

Results

Histopathology

Sections of the PBS-treated and yeast-treated tumors were carried out to examine the histopathology of tumor, ischemic (coagulative) necrosis and leukocytic infiltrates.

Tumor

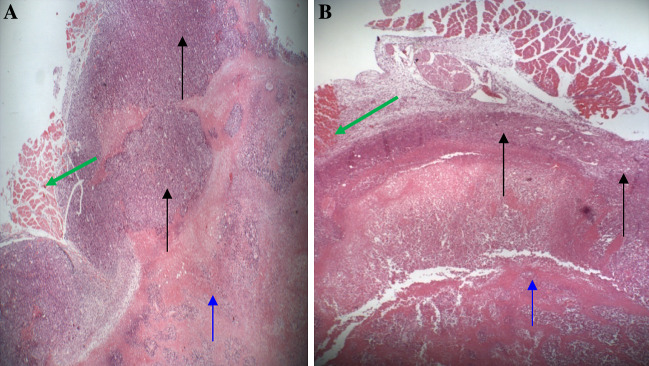

Sections from both the PBS-treated tumor and yeast-treated tumor show poorly differentiated carcinoma infiltrating into the skeletal muscles and adipose tissue. The sections show viable tumor at the periphery and ischemic tumor at the center. The volume of viable tumor from the PBS-treated tumor is greater than the yeast-treated tumor (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Histology of Solid Ehrlich Carcinoma Tumor (SEC). The infiltrating carcinoma invades the skeletal muscle (green arrow) and adipose tissue and were obtained on day 35 post-treatment with yeast. a Section of normal SEC morphology consisting of large viable tumor tissue (periphery) (black arrow) and ischemic (coagulative) necrotic tissue (central) (blue arrows). Data is a representative of three examined slides from different mice. b Section of yeast-treated tumor demonstrates a thin peripheral layer of tumor tissue, while most of the tumor has undergone extensive necrosis. Data is a representative of seven examined slides from different mice (a, and b are stained with H&E ×40)

Ischemic (coagulative) necrosis and degenerative changes

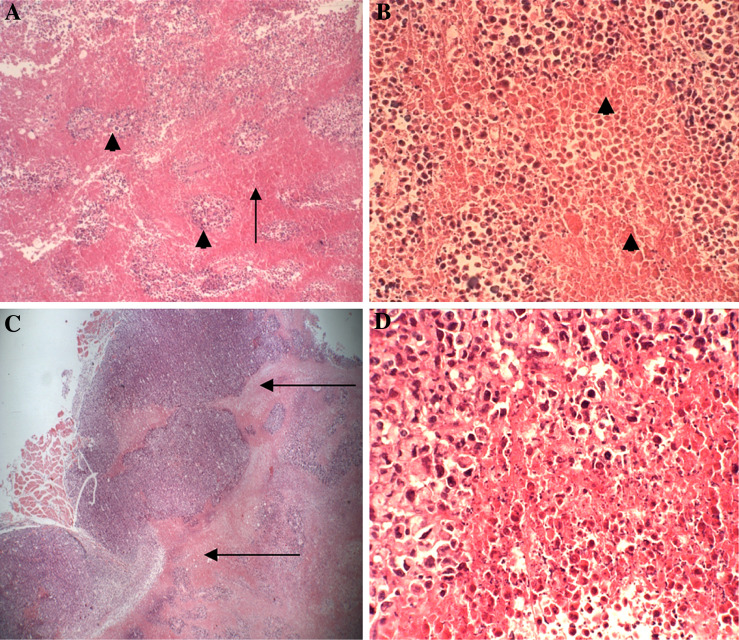

H&E stained sections of the tumor from the PBS-treated tumor and yeast-treated tumor of mice show ischemic (coagulative) necrosis in the center of the tumor; however, there are more residual islands of viable tumor in the PBS-treated group (Fig. 2a, b) than the yeast-treated group (Fig. 3a). Compared to the control mice, the yeast treated tumor also demonstrate tumor necrosis in more advanced stages of degeneration, characterized by more extensive degenerative changes such as karyolysis (fading of chromatin) and karyorrhexis (fragmentation of nuclei) (Fig. 3b–d). In addition, a unique characteristic of yeast-treated tumor is the presence of liquefactive necrosis, especially at the viable-necrotic tumor interface (Fig. 3b–d). Much cellular debris that could represent apoptotic tumor cells, inflammatory cells, or yeast cells are evident (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 2.

Cross sections in the center of the control untreated tumor tissue show ischemic (coagulative) necrosis at 35 days post-treatment with yeast. a Viable islands of tumor cells (arrow head) in between ischemic tumor cells (arrow) (H&E ×40). b Coagulative or ischemic tumor necrosis (arrow heads) with minimal inflammatory cells. (H&E ×40). c The infiltrating tumor showing a clean (minimal inflammatory cells) viable-necrotic tumor interface (arrow) (H&E ×40). d High power view of the viable-necrotic tumor interface showing necrotic tumor cells with minimal inflammatory cells and apoptotic tumor cells (H&E ×400)

Fig. 3.

Cross sections in the center of the yeast-treated tumor tissue that show ischemic (coagulative) necrosis at 35 days post-treatment with yeast. (a–e are stained H&E) a Ischemic necrosis of the center of the tumor showing minimal viable islands of tumor cells (arrow) (×40). b Liquefactive tumor necrosis where the necrotic center is surrounded by many leukocytes (arrow) (×40). c The viable-necrotic tumor interface (arrow head) showing many leukocytes and cell debris (×40). d High power view of the viable-necrotic tumor interface showing much cellular debris, foamy macrophages and other inflammatory cells (×400). e High power view of the viable-necrotic tumor interface showing foamy macrophages. Note the tumor cell in the right corner that is surrounded by macrophages (×1,200)

Leukocytic Infiltrate

The effect of intratumoral yeast injection on the recruitment of leukocytes into the tumors was examined (Fig. 3b–d). Histopathology of PBS-treated tumor shows minimal leukocytic infiltrates (Fig. 2b–d), while yeast-treated tumor shows intense leukocytic infiltrates at the viable-necrotic tumor interface (Fig. 3b–d). Foamy macrophages predominate the infiltrates of all yeast-treated tumor of mice (Fig. 3d, e). They are large cells with central nuclei and large foamy cytoplasm. In some instances, several macrophages are seen attached to one tumor cell (Fig. 3d, e).

Tumor growth

Experiments were carried out to examine whether the above-mentioned histopathology changes induced by yeast are associated with a tumor growth curve that demonstrates a significant antitumor response.

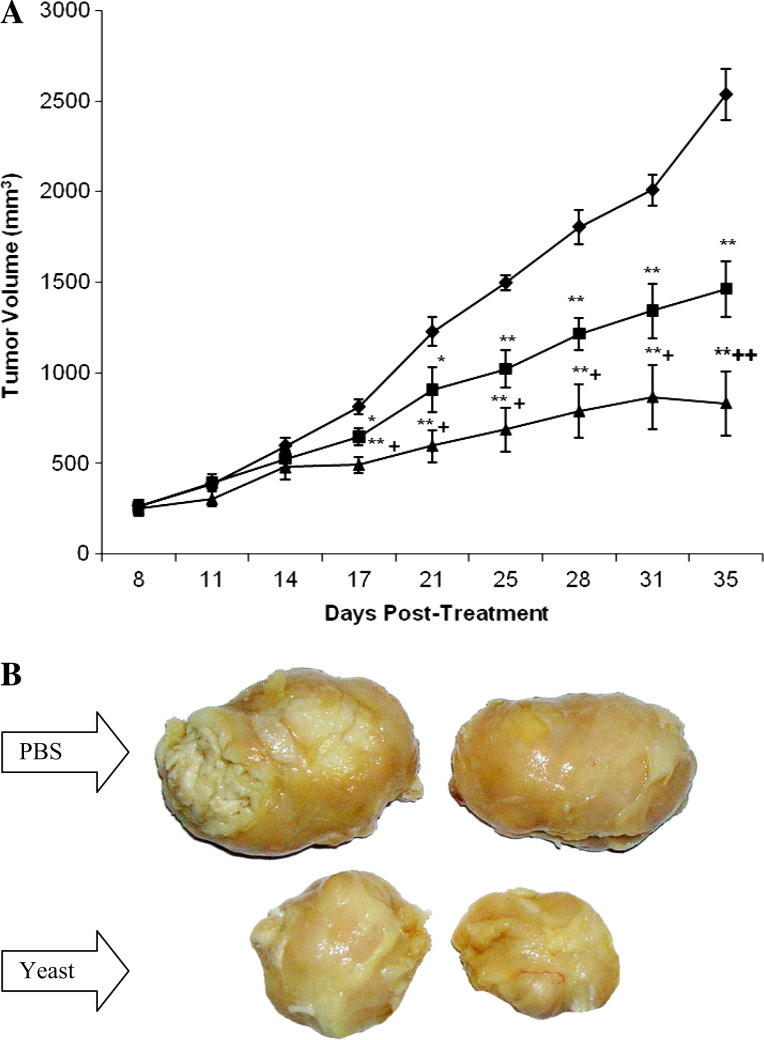

Tumor volume (TV)

Mice-bearing SEC were injected IT three times a week with yeast commencing on day 8 of tumor cells inoculation up until day 35. Antitumor activity was assessed by time interval measurements of changes in TV during the experimental time course. Figure 4a shows that administration of the mice with yeast caused a continuous, highly significant (P > 0.01) delay of TV that was detected as early as day 17 post-tumor inoculation (9 days post treatment with yeast) and maximized at day 35. The effect was shown to be dose-dependent. TV reached 1463.56 ± 153.57 and 833.73 ± 177.13 mm3 in mice treated with yeast at 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells, respectively, as compared to 2537.11 ± 143.52 mm3 for the PBS-treated mice. This represents a 42.31% (P < 0.01) and 67.14% (P < 0.01) decrease in TV as compared to the PBS group. Also, there was a significant difference on the effect of yeast treatment at the high dose as compared to its low dose (P < 0.01). A representative photograph of the SEC tumor isolated from yeast-treated mice (20 × 106 cells) clearly demonstrate significant tumor regression as compared to PBS-treated mice. Similar levels of tumor regression were observed in all animals bearing tumors and treated with yeast (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

In vivo effect of yeast on tumor volume (TV). a Female Swiss albino mice were inoculated in the right thigh with EAC cells. At day 8 after tumor cell inoculation, mice bearing SEC tumor were injected IT three times a week with yeast at concentrations of 10 × 106 cells (square) and 20 × 106 cells (triangle); TV was examined from day 8 to day 35 post-tumor cell inoculation. Results were compared with PBS-treated mice (diamond). Each value represents the mean ± SE from all animals/group (13 for PBS group and 14 for yeast groups). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01: as compared to the PBS group. +P < 0.05, ++P < 0.01: as compared to yeast-treated mice (10 × 106 cells) at the corresponding time point. b Photograph of tumor regression; PBS-treated and yeast-treated mice bearing tumor. Data is representative of all groups examined

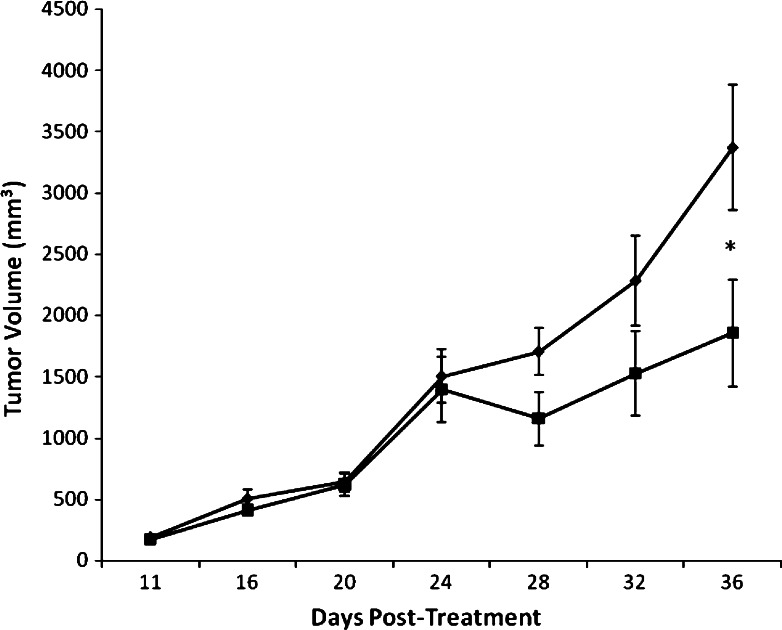

Effect of lower overall dose of yeast injection (10 injections)

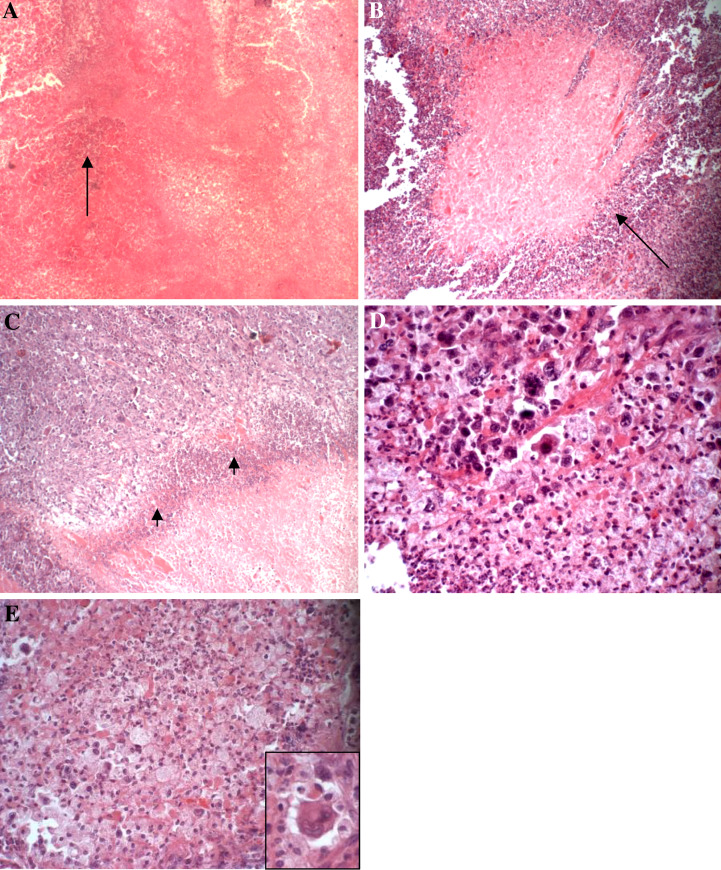

Preliminary experiments showed that lower overall dose of yeast 10 × 106 cells also exerts antitumor activity. Data in Fig. 5 shows that yeast induced a marked and progressive suppression of the tumor growth that was maximized to 44.94%, P < 0.05 at day 35 as compared to the PBS group.

Fig. 5.

Effect of lower overall dose of yeast on tumor volume (TV). Female Swiss albino mice were inoculated in the right thigh with EAC cells. At day 11, after tumor cell inoculation, mice bearing SEC tumor were injected IT twice a week with yeast (10 × 106 cells) (square). TV was examined from day 11 to day 35 post-tumor inoculation. Results were compared with PBS-treated mice bearing tumor (diamond). Each value represents the mean ± SE of 10 mice/group for both PBS-treated and yeast-treated mice. *P < 0.05 as compared to PBS group at the corresponding time point

Tumor weight (TW)

Table 1 shows the effect of yeast injection three times a week on TW at the end of the experiment, day 35. Treatment with yeast resulted in a remarkable decrease in TW and followed dose-dependent responses. TWs were 5.07 ± 0.549 and 2.87 ± 0.498 g at yeast concentrations of 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells, respectively, as compared with PBS-treated mice (6.62 ± 0.38 g). This represents a 23.4% (P < 0.05) and 56.6% (P < 0.01) decrease in TW. Again, there was a significant difference on the effect of yeast treatment at the high dose as compared to its low dose (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

Effect of the administration of two different concentrations of yeast on body weight (g) and tumor weight (g) in mice-bearing Ehrlich solid carcinoma

| Parameters | Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control mice (without tumor) | Tumor bearing mice | |||

| PBS | Yeast (10 × 106 cells) | Yeast (20 × 106 cells) | ||

| Initial body weight (g) (at day 0) | 19.87 ± 0.668 | 20.21 ± 0.466 | 20.76 ± 0.619 | 20.56 ± 0.543 |

| # of mice | 10 | 13 | 14 | 14 |

| Final body weight (g) (at day 35) | 26.62 ± 0.941 | 26.67 ± 0.583 | 26.88 ± 0.481 | 27.84 ± 0.986 |

| # of mice | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 |

| Tumor weight (g) (at day 35) | – | 6.62 ± 0.381 | 5.07 ± 0.549* | 2.87 ± 0.498**,† |

| Net final body weight (g) | 26.62 ± 0.941 | 20.06 ± 0.482*** | 21.81 ± 0.393*** | 24.97 ± 0.766**,† |

| Body weight gain (g) | +6.75 | −0.15 | +1.05 | +4.41 |

| % of change from the initial body weight | (+33.97%) | (−0.74%) | (+5.06%) | (+21.45%) |

Each value represents the mean ± SE. Net final body weight = (Final body weight at day 35) − (Tumor weight at day 35); Body weight gain = (Net final body weight) − (Initial body weight). % of change in body weight from the initial body weight of each group

*,** Significantly different from the PBS group at 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively

*** Significantly different from the control group at 0.01 levels

† Significantly different from Yeast (10 × 106 cells) group at 0.01 levels

Body weight (BW)

Data in Table 1 show changes in initial, final and net BWs at day 35 post administration of yeast three times a week in mice bearing SEC. Administration of a high dose of yeast to SEC-bearing mice recorded a marked body weight gain of +21.5%, P < 0.01, as compared to PBS group.

Apoptosis

This study was undertaken to evaluate the mechanisms of anti-tumor activity of S. cerevisiae. The apoptotic effect of yeast against SEC cells in vivo was evaluated by flow cytometry and histopathology at day 35 post tumor cells inoculation.

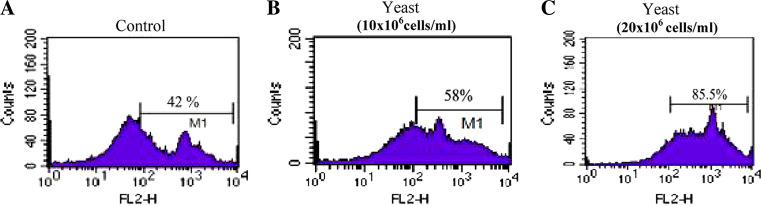

Flow cytometry analysis

Figure 6a displays the flow cytometry analysis of the percentages of apoptotic cancer cells. Yeast treatment three times a week, in a dose-dependent manner, resulted in a significant increase in the percentages of apoptosis: 57.56 ± 2.74%, P < 0.05 and 78.62 ± 4.25%, P < 0.01 at concentrations of 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells, respectively, as compared to the PBS mice (42.61 ± 5.56%). This represents a 35.1 and 84.5% increase in apoptosis post treatment with yeast at 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells, respectively, as compared with PBS group. Additionally, a marked significant difference (P < 0.01) was observed between low and high doses of yeast treatments.

Fig. 6.

A representative dot blot, showing percent apoptotic SEC cells in mice bearing solid tumor of control and yeast- treated mice groups (10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells). The percent of apoptotic SEC cells was determined by flow cytometry using Annexin V and propidium iodide technique at day 35

Percent of early apoptosis

The study showed an insignificant change in the percent of early apoptosis post-treatment with yeast at concentrations of 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells (7.46 ± 3.73 and 9.65 ± 4.66%, respectively, as compared to the PBS mice at 6.25 ± 2.7%).

Histopathology

Cross-sections of SEC-bearing mice showing yeast-treated tumor demonstrate extensive necrosis and apoptosis (Fig. 3b–e), while sections of PBS-treated tumor show that most of the tumor cells are viable except for some areas of ischemic necrosis with few foci of apoptosis (Fig. 2c, d).

Quantification of cytokine levels

The effects of yeast (treated 3 times/week) on the levels of plasma TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 measured on day 35 of tumor cells transplantation are shown in Table 2. Cytokines were assayed in the following four groups: the control mice without tumor (n = 8), the PBS-treated tumor (n = 11) and yeast-treated groups-bearing SEC (n = 13 or 14).

Table 2.

In vivo effect of IP injection of yeast on plasma TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 levels in mice bearing SEC on day 35 post tumor cell inoculation

| Parameters | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control mice (without tumor) | Tumor bearing mice | |||

| PBS | Yeast (10 × 106 cells) | Yeast (20 × 106 cells) | ||

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 1100 ± 10.4 | 1146 ± 16 | 1213.6 ± 17.8* | 1276.5 ± 12.4*,**,*** |

| % changea | – | 4.17 | 10.33 | 16.01 |

| # of mice | 8 | 11 | 13 | 11 |

| IFN-γ (pg/ml) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 158.75 ± 19.8 | 142.2 ± 10.6 | 183.7 ± 15.7 | 288.2 ± 48.7*,**,*** |

| % changea | – | −10.46 | 15.74 | 81.51 |

| # of mice | 8 | 11 | 13 | 11 |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | ||||

| Mean ± SE | 405.5 ± 25.0 | 858.5 ± 140.9* | 519.9 ± 76.8** | 424.2 ± 28.9** |

| % changea | – | 111.71 | 28.21 | 4.61 |

| # of mice | 8 | 11 | 13 | 11 |

Each value represents the mean ± SE from the indicated number of mice

* Significantly different from control group at 0.01 level

** Significantly different from the PBS group at 0.01 level

*** Significantly different from the yeast (10 × 106 cells) group at 0.01 level

aWith respect to the control group

TNF-α plasma level

As we can see in Table 2, no detectable change was observed in the level of TNF-α measured in the control mice when compared with the PBS group. Treatment with yeast to mice bearing SEC significantly elevated TNF-α production with respect to the PBS group. The effect of yeast was dose-dependent: 10.33 and 16.01% for 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells, respectively, as compared to control group (P < 0.01). In addition, the higher dose of yeast was significantly different from the PBS group and the low dose of yeast (P < 0.01).

IFN-γ plasma level

Injection of the low dose of yeast produced no significant increase in plasma IFN-γ level; meanwhile, treatment with the high dose caused marked elevation in plasma IFN-γ levels (P < 0.01) with respect to the control, the PBS group and the low dose of yeast (Table 2).

IL-10 plasma levels

IL-10 concentrations were dramatically elevated in plasma of the PBS-treated mice (111.71%, P < 0.01) over the control group values. Administration of yeast lowered the elevated level of IL-10 plasma to control values. Such restoration was more obvious with the higher dose of yeast (Table 2).

Adverse effects of yeast (toxicity)

Recorded daily examinations of mice showed that injections of heat-killed S. cerevisiae resulted in no adverse side effects as indicated by: (a) normal feeding/drinking and life activity patterns; (b) all animals surviving the 35 day treatment period, and (c) yeast-treated mice showing a significant final body weight gain of +21.5%, P < 0.01 at day 35.

Discussion

We have recently presented in vivo evidence of anticancer efficacy of yeast based upon immune compromised nude mice xenografts bearing human breast cancer [17, 25]. We thought that it would be of particular interest to examine the effects of yeast administration on immunocompetent mouse, Swiss albino, bearing Ehrlich Carcinoma, where the dendritic cells and macrophages will clearly take up the yeast, process it and present it to the immune system, leading to cellular and cytokine mediated effects. Results revealed significant tumor regression post-injection of S. cerevisiae. Yeast-treated tumor bearing mice showed thin layer of viable tumor tissue as compared to a large layer of viable tumor tissue in the control tumor (Fig. 1a, b). Yeast-induced tumor regression was further coupled with extensive degenerative changes in the tumor tissue, such as karyolysis (fading of chromatin) and karyorrhexis (fragmentation of nuclei). Histopathology of the SEC tumor showed ischemic or coagulative necrosis of the central portion leaving viable islands and sheets of tumor cells at the center and periphery. This process is a consequence of inadequate or loss of blood supply secondary to overgrowth of tumor cells. Control tumor bearing mice show many islands of viable tumor cells scattered in between necrotic tissue. However, yeast-treated tumor bearing mice showed many areas of liquefactive necrosis, especially at the viable-necrotic tumor interface, a feature unique to yeast-treated tumor. These changes are associated with a tumor growth curve that demonstrates a significant antitumor response that peaked at 35 days.

Yeast exerts its anti-cancer activity via two independent mechanisms: (1) the apoptotic effect and (2) the immune-modulatory effect. Regarding the apoptotic effect of yeast, we investigated whether or not yeast treatment triggers apoptosis in SEC cells. Flow cytometry and histopathology analysis revealed that treatment with yeast triggers a significant increase in tumor cell apoptosis. Treatment with yeast resulted in 35.1 and 84.5% increase in percent of apoptosis at 10 × 106 and 20 × 106 cells, respectively, as compared with PBS group (see representative dot blot, Fig. 6). The percent of apoptotic SEC cells was determined by flow cytometry using Annexin V and propidium iodide technique at day 35. On the other hand, we noted insignificant changes in the percent of early apoptosis (at P > 0.05) between yeast-treated and control groups, as determined by Annexin V. The reason for the insignificant change may reflect the long-term effect of yeast treatment (35 days), where most of the apoptotic cells were in a later stage.

The unique ability of S. cerevisiae to induce apoptosis in cancer cells, post-phagocytosis, was recently observed in our laboratory. We found the effect to be yeast-specific, as no effect was observed by fungal mycelia [21]. In addition, yeast showed no toxicity against normal cells [20]. It is of interest to note that certain animal viruses were also thought to have the ability to target and kill tumor cells via intratumoral injection. Among them are: adenovirus [32, 46], fowlpox virus [45], vesicular stomatitis virus [1, 4, 64], and bovine herpes virus-4 (BoHV-4) [26]. However, significant obstacles limit their use, such as the limited distribution of the vectors within the tumor mass even after direct intratumoral administration and the fact that BALB/c human primary cells are also targets for apoptosis effect by animal viruses [12, 28, 31, 39, 40, 43, 60, 67]. Our findings suggest the possible use of a different microbe, namely S. cerevisiae, as an alternative to viruses for the treatment of cancer.

With respect to immune-modulatory effects caused by yeast, our results show yeast treatment led to the manipulation of several cytokines’ production. It significantly elevated TNF-α and IFN-γ plasma levels and down-regulated the elevated IL-10 level. TNF-α and IFN-γ cytokines are known to express potent antitumor activity [5, 7, 10] and act synergistically in cancer cell death via apoptotic and necrotic effects [63, 65]. On the other hand, IL-10 is known as an immunosuppressive cytokine because it exerts an inhibitory effect on several cytokines’ synthesis; IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α [58, 70], and IL-12 [57]. In addition, yeast may have an augmentatory effect on NK cell activity. Recent studies showed that β-glucan derived from the cell wall of S. cerevisiae has potent NK enhancement [55]. NK cells represent a major component of innate immunity that plays an important role in immune surveillance against cancer [3, 30, 34].

Another interesting finding of this study is that yeast administration resulted in enhancement of leukocytes infiltrating the tumor. Histopathology of the yeast-treated tumor showed many leukocytes situated at the interface, an effect rarely observed in the control mice. We also detected the presence of macrophages in these infiltrates. Macrophages are thought to be one of the main effectors responsible for antitumor defense. Tumoricidal macrophages can recognize and destroy neoplastic cells, thereby not harming the non-neoplastic cell population [44, 74]. Recent studies have shown that several agents are capable of enhancing the recruitment of a significant number of leukocytes into tumors: the chemokine CCL21 [69], IL-12 gene therapy [33], and histamine H2 receptor antagonist (famotidine) that inhibits stomach acid production [35, 53, 54]. Furthermore, increased infiltration of immune cells has been shown to be associated with the reduction of tumor volume [33] and improvement of disease-free survival [53]. The ability of yeast to enhance recruitment of macrophages into the tumor is superior over other agents because it is a safe and non-toxic product.

Finally, S. cerevisiae has shown no toxic characteristics as manifested by the ability of all animals to survive the 35-day treatment period with normal feeding/drinking and life activity patterns as well as with a significant body weight gain as compared with control mice. S. cerevisiae is viewed as a non-threatening agent by the human population. Brewer’s yeast (S. cerevisiae) is sold as a food supplement for human consumption for constipation [72]. In addition, another non-pathogenic strain of yeast, S. boulardii, has been found to be an effective means of treatment for gastrointestinal infections, such as recurrent Clostridium difficile, colitis, in human subjects [49, 66].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing that IT treatment of heat-killed non-pathogenic yeast, S. cerevisiae, exhibits very efficient oncolytic activity in delaying tumor growth in immunocompetent mice bearing EAC cells. The effect is rapid (9 days) and induced marked tumor growth inhibition (−67%, P < 0.01) 25 days post yeast treatment as compared with control untreated mice. The mechanisms underlying the inhibitory effect of yeast involve both an apoptotic effect against SEC cells and modulation of immune system. These data may establish the foundation for in vivo studies that could have therapeutic implications.

References

- 1.Ahmed M, Cramer SD, Lyles DS. Sensitivity of prostate tumors to wild type and M protein mutant vesicular stomatitis viruses. Virology. 2004;330(1):34–49. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arends MJ, Wyllie AH. Apoptosis: mechanisms and roles in pathology. Rev Exp Pathol Int. 1991;32:223–254. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-364932-4.50010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae SH, Park YJ, Park JB, Choi YS, Kim MS, Sin JI. Therapeutic synergy of human papillomavirus E7 subunit vaccines plus cisplatin in an animal tumor model: causal involvement of increased sensitivity of cisplatin-treated tumors to CTL-mediated killing in therapeutic synergy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(1):341–349. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balachandran S, Porosnicu M, Barber GN. Oncolytic activity of vesicular stomatitis virus is effective against tumors exhibiting aberrant p53, Ras, or myc function and involves the induction of apoptosis. J Virol. 2001;75(7):3474–3479. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3474-3479.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron S, Tyring SK, Fleischmann WR, Jr, Coppenhaver DH, Niesel DW, Klimpel GR, Stanton GJ, Hughes TK. The interferon. Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. JAMA. 1991;266:1375–1383. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.10.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biber JL, Jabbour S, Parihar R, Dierksheide J, Hu Y, Baumann H, Bouchard P, Caligiuri MA, Carson W. Administration of two macrophage-derived interferon-gamma-inducing factors (IL-12 and IL-15) induces a lethal systemic inflammatory response in mice that is dependent on natural killer cells but does not require interferon-gamma. Cell Immunol. 2002;216(1–2):31–42. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00501-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borish LC, Steinke JW. Cytokines and chemokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S460–S475. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson WE, Dierksheide JE, Jabbour S, Anghelina M, Bouchard P, Ku G, Yu H, Baumann H, Shah MH, Cooper MA, Durbin J, Caligiuri MA. Coadministration of interleukin-18 and interleukin-12 induces a fatal inflammatory response in mice: critical role of natural killer cell interferon-gamma production and STAT-mediated signal transduction. Blood. 2000;96(4):1465–1473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson WE, Yu H, Dierksheide J, Pfeffer K, Bouchard P, Clark R, Durbin J, Baldwin AS, Peschon J, Johnson PR, Ku G, Baumann H, Caligiuri MA. A fatal cytokine-induced systemic inflammatory response reveals a critical role for NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;162(8):4943–4951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha SS, Kim MS, Choi YH, Sung BJ, Shin NK, Shin HC, Sung YC, Oh BH. 2.8 A resolution crystal structure of human TRAIL, a cytokine with selective antitumor activity. Immunity. 1999;11:253–261. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farina HG, Pomies M, Alonso DF, Gomez DE. Antitumor and antiangiogenic activity of soy isoflavone genistein in mouse models of melanoma and breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(4):885–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geoerger B, Grill J, Opolon P, Morizet J, Aubert G, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Bressac De-Paillerets B, Barrois M, Feunteun J, Kirn DH, Vassal G. Oncolytic activity of the E1B-55 kDa-deleted adenovirus ONYX-015 is independent of cellular p53 status in human malignant glioma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2002;62(3):764–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghoneum M. Anti-HIV activity in vitro of MGN-3, an activated arabinoxylan from rice bran. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243(1):25–29. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghoneum M. Enhancement of human natural killer cell activity by modified arabinoxylan from rice bran (MGN-3. Int J Immunother. 1998;XIV(2):89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghoneum M, Abedi S. Enhancement of natural killer cell activity of aged mice by modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56(12):1581–1588. doi: 10.1211/0022357044922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghoneum M, Brown J. NK immunorestoration of cancer patients by MGN-3, a modified arabinoxylan rice bran (study of 32 patients followed for up to 4 years) In: Klatz R, Goldman R, editors. Anti-aging medical therapeutics. Marina del Rey: Health Quest Publications; 1999. pp. 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghoneum M, Brown J, Gollapudi S. “Yeast therapy for the treatment of cancer and its enhancement by MGN-3/Biobran, an arabinoxylan rice bran” in Apoptosis review. Hauppague: Nova; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghoneum M, Gollapudi S. Induction of apoptosis in human breast cancer cells by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the baker’s yeast, in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:1455–1463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghoneum M, Gollapudi S. Modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) enhances yeast-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:859–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghoneum M, Gollapudi S. Synergistic role of arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/Biobran) in S. cerevisiae-induced apoptosis of monolayer breast cancer MCF-7 Cells. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:4187–4196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghoneum M, Gollapudi S. Apoptosis of breast cancer MCF-7 cells in vitro is induced specifically by yeast and not by fungal mycelia. Anticancer Res. 2006; 26:2013–20222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghoneum M, Hamilton J, Brown J, Gollapudi S. Human squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue and colon undergoes apoptosis upon phagocytosis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the baker’s yeast, in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:981–989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghoneum M, Jewett A. Production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma from human peripheral blood lymphocytes by MGN-3, a modified arabinoxylan from rice bran, and its synergy with interleukin-2 in vitro. Cancer Detect Prev. 2000;24(4):314–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghoneum M, Matsuura M. Augmentation of macrophage phagocytosis by modified arabinoxylan rice bran (MGN-3/biobran) Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2004;17(3):283–292. doi: 10.1177/039463200401700308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghoneum M, Wang L, Agrawal S, Gollapudi S. Yeast therapy for the treatment of breast cancer: a nude mice model study. In Vivo. 2007;21:251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillet L, Dewals B, Farnir F, de Leval L, Vanderplasschen A. Bovine herpesvirus 4 induces apoptosis of human carcinoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005;65(20):9463–9472. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gollob JA, Mier JW, Veenstra K, McDermott DF, Clancy D, Clancy M, Atkins MB. Phase I trial of twice-weekly intravenous interleukin 12 in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer or malignant melanoma: ability to maintain IFN-gamma induction is associated with clinical response. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(5):1678–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griebel PJ, Ohmann HB, Lawman MJ, Babiuk LA. The interaction between bovine herpesvirus type 1 and activated bovine T lymphocytes. J Gen Virol. 1990;71( Pt 2):369–377. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-2-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanson MG, Ozenci V, Carlsten MC, Glimelius BL, Frodin JE, Masucci G, Malmberg KJ, Kiessling RV. A short-term dietary supplementation with high doses of vitamin E increases NK cell cytolytic activity in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(7):973–984. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0261-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herberman RB. Cancer immunotherapy with natural killer cells. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(3 Suppl 7):27–30. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.33079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hinshaw VS, Olsen CW, Dybdahl-Sissoko N, Evans D. Apoptosis: a mechanism of cell killing by influenza A and B viruses. J Virol. 1994;68(6):3667–3673. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3667-3673.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffmann D, Bayer W, Grunwald T, Wildner O. Intratumoral expression of respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein in combination with cytokines encoded by adenoviral vectors as in situ tumor vaccine for colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(7):1942–1950. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imagawa Y, Satake K, Kato Y, Tahara H, Tsukuda M. Antitumor and antiangiogenic effects of interleukin 12 gene therapy in murine head and neck carcinoma model. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31(3):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalinski P, Giermasz A, Nakamura Y, Basse P, Storkus WJ, Kirkwood JM, Mailliard RB. Helper role of NK cells during the induction of anticancer responses by dendritic cells. Mol Immunol. 2005;42(4):535–539. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapoor S, Pal S, Sahni P, Dattagupta S, Kanti Chattopadhyay T. Effect of pre-operative short course famotidine on tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer: a double blind, placebo controlled, prospective randomized study. J Surg Res. 2005;129(2):172–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katiyar SK, Agarwal R, Mukhtar H. Inhibition of spontaneous and photo-enhanced lipid peroxidation in mouse epidermal microsomes by EC derivatives from green tea. Cancer Lett. 1994;79:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr JFR, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a biological phenomena with wide ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Brit J cancer. 1972;26:239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim DS, Kim SY, Jeong YM, Jeon SE, Kim MK, Kwon SB, Na JI, Park KC. Light-activated indole-3-acetic acid induces apoptosis in g361 human melanoma cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29(12):2404–2409. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kopecky SA, Willingham MC, Lyles DS. Matrix protein and another viral component contribute to induction of apoptosis in cells infected with vesicular stomatitis virus. J Virol. 2001;75(24):12169–12181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.12169-12181.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koyama AH. Induction of apoptotic DNA fragmentation by the infection of vesicular stomatitis virus. Virus Res. 1995;37(3):285–290. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(95)00026-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumi-Diaka JK, Hassanhi M, Merchant K, Horman V. Influence of genistein isoflavone on matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in prostate cancer cells. J Med Food. 2006;9(4):491–497. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee SF, Liang YC, Lin JK. Inhibition of 1,2,4-benzenetriol-generated active oxygen species and induction of phase II enzymes by green tea polyphenols. Chem Biol Interact. 1995;98:283–301. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(95)03652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine B, Huang Q, Isaacs JT, Reed JC, Griffin DE, Hardwick JM. Conversion of lytic to persistent alphavirus infection by the bcl-2 cellular oncogene. Nature. 1993;361(6414):739–742. doi: 10.1038/361739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin EY, Pollard JW. Macrophages: modulators of breast cancer progression. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;256:158–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu A, Guardino A, Chinsangaram L, Goldstein MJ, Panicali D, Levy R. Therapeutic vaccination against murine lymphoma by intratumoral injection of recombinant fowlpox virus encoding CD40 ligand. Cancer Res. 2007;67(14):7037–7044. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lupu CM, Eisenbach C, Lupu AD, Kuefner MA, Hoyler B, Stremmel W, Encke J. Adenoviral B7-H3 therapy induces tumor specific immune responses and reduces secondary metastasis in a murine model of colon cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;18(3):745–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malafa MP, Fokum FD, Mowlavi A, Abusief M, King M. Vitamin E inhibits melanoma growth in mice. Surgery. 2002;131:85–91. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.119191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marty M, Mignot L, Gisselbrecht G, Morvan F, Gorins A, Boiron M. Teratogenic and mutagenic risks of radiotherapy: when and how to prescribe contraception. Contracept Fertil Sex. 1985;13:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, Fekety R, Elmer GW, Moyer KA, Melcher SA, Bowen KE, Cox JL, Noorani Z, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease. Jama. 1994;271(24):1913–1918. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.24.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mills KH, Greally JF, Temperley IJ, Mullins GM. Haematological and immune suppressive effects of total body irradiation in the rat. Ir J Med Sci. 1980;149:201–208. doi: 10.1007/BF02939140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murphy D, Detjen KM, Welzel M, Wiedenmann B, Rosewicz S. Interferon-alpha delays S-phase progression in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inhibition of specific cyclin-dependent kinases. Hepatology. 2001;33(2):346–356. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuzil J. Vitamin E succinate and cancer treatment: a vitamin E prototype for selective antitumour activity. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1822–1826. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parshad R, Hazrah P, Kumar S, Gupta SD, Ray R, Bal S. Effect of preoperative short course famotidine on TILs and survival in breast cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42(4):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parshad R, Kapoor S, Gupta SD, Kumar A, Chattopadhyaya TK. Does famotidine enhance tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer? Results of a randomized prospective pilot study. Acta Oncol. 2002;41(4):362–365. doi: 10.1080/028418602760169415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pelizon AC, Kaneno R, Soares AM, Meira DA, Sartori A. Immunomodulatory activities associated with beta-glucan derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae . Physiol Res. 2005;54(5):557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pfluger P, Kluth D, Landes N, Bumke-Vogt C, Brigelius-Flohe R. Vitamin E: underestimated as an antioxidant. Redox Rep. 2004;9(5):249–254. doi: 10.1179/135100004225006740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahim SS, Khan N, Boddupalli CS, Hasnain SE, Mukhopadhyay S. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) mediated suppression of IL-12 production in RAW 264.7 cells also involves c-rel transcription factor. Immunology. 2005;114(3):313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Raychaudhuri B, Fisher CJ, Farver CF, Malur A, Drazba J, Kavuru MS, Thomassen MJ. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)-mediated inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production by human alveolar macrophages. Cytokine. 2000;12(9):1348–1355. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodriguez SK, Guo W, Liu L, Band MA, Paulson EK, Meydani M. Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor angiogenic signaling by disrupting the formation of a receptor complex. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(7):1635–1644. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rothmann T, Hengstermann A, Whitaker NJ, Scheffner M, zur Hausen H. Replication of ONYX-015, a potential anticancer adenovirus, is independent of p53 status in tumor cells. J Virol. 1998;72(12):9470–9478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9470-9478.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sanderson BJ, Ferguson LR, Denny WA. Mutagenic and carcinogenic properties of platinum-based anticancer drugs. Mutat Res. 1996;355:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Santin AD, Hermonat PL, Ravaggi A, Bellone S, Roman J, Pecorelli S, Cannon M, Parham GP. Effects of concurrent cisplatinum administration during radiotherapy vs. radiotherapy alone on the immune function of patients with cancer of the uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48:997–1006. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sasagawa T, Hlaing M, Akaike T. Synergistic induction of apoptosis in murine hepatoma Hepa1–6 cells by IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272(3):674–680. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stojdl DF, Lichty B, Knowles S, Marius R, Atkins H, Sonenberg N, Bell JC. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nat Med. 2000;6(7):821–825. doi: 10.1038/77558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suk K, Kim YH, Chang I, Kim JY, Choi YH, Lee KY, Lee MS. IFNalpha sensitizes ME-180 human cervical cancer cells to TNFalpha-induced apoptosis by inhibiting cytoprotective NF-kappaB activation. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:66–70. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Surawicz CM, McFarland LV, Elmer G, Chinn J. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis with vancomycin and Saccharomyces boulardii . Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84(10):1285–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takizawa T, Matsukawa S, Higuchi Y, Nakamura S, Nakanishi Y, Fukuda R. Induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis) by influenza virus infection in tissue culture cells. J Gen Virol. 1993;74(Pt 11):2347–2355. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-11-2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tribukait B, Moberger G, Zetterberg A (1975) Methodological aspects of rapid flow cytofluorometry for DNA analysis of human urinary bladder cells. In: Pulse-Cytophotometry, part I. European press, Medicon, Ghent, Belgium, pp 50–60

- 69.Turnquist HR, Lin X, Ashour AE, Hollingsworth MA, Singh RK, Talmadge JE, Solheim JC. CCL21 induces extensive intratumoral immune cell infiltration and specific anti-tumor cellular immunity. Int J Oncol. 2007;30(3):631–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang P, Wu P, Siegel MI, Egan RW, Billah MM. Interleukin (IL)-10 inhibits nuclear factor kappa B (NF kappa B) activation in human monocytes. IL-10 and IL-4 suppress cytokine synthesis by different mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(16):9558–9563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weisfuse IB, Graham DJ, Will M, Parkinson D, Snydman DR, Atkins M, Karron RA, Feinstone S, Rayner AA, Fisher RI, et al. An outbreak of hepatitis A among cancer patients treated with interleukin-2 and lymphokine-activated killer cells. J Infect Dis. 1990;161(4):647–652. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wenk R, Bertolino M, Ochoa J, Cullen C, Bertucelli N, Bruera E. Laxative effects of fresh baker’s yeast. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(3):163–164. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Whitsett TG, Jr, Lamartiniere CA. Genistein and resveratrol: mammary cancer chemoprevention and mechanisms of action in the rat. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6(12):1699–1706. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.12.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whitworth PW, Pak CC, Esgro J, Kleinerman ES, Fidler IJ. Macrophages and cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990;8(4):319–351. doi: 10.1007/BF00052607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yano H, Iemura A, Haramaki M, Ogasawara S, Takayama A, Akiba J, Kojiro M. Interferon alfa receptor expression and growth inhibition by interferon alfa in human liver cancer cell lines. Hepatology. 1999;29(6):1708–1717. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yeh TC, Chiang PC, Li TK, Hsu JL, Lin CJ, Wang SW, Peng CY, Guh JH. Genistein induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinomas via interaction of endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial insult. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73(6):782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]