Abstract

The complexity of tumor biology necessitates a multimodality approach that targets different aspects of tumor environment in order to generate the greatest benefit. IFN-inducible T cell α chemoattractant (ITAC)/CXCL11 and IFN-inducible protein 10 (IP10)/CXCL10 could exert antitumor effects with functional specificity and thus emerge as attractive candidates for combinatorial strategy. Disappointedly, a synergistic antitumor effect could not be observed when CXCL10 and CXCL11 were pooled together. In this regard, we seek to improve antitumor efficacy by integrating their individual functional moieties into a chemokine chimeric molecule, designated ITIP, which was engineered by substituting the N-terminal and N-loop region of CXCL10 with those of CXCL11. The functional properties of ITIP were determined by chemotaxis and angiogenesis assays. The antitumor efficacy was tested in murine CT26 colon carcinoma, 4T1 mammary carcinoma and 3LL lung carcinoma. Here we showed that ITIP not only exhibited respective functional superiority but strikingly promoted regression of established tumors and remarkably prolonged survival of mice compared with its parent chemokines, either alone or in combination. The chemokine chimera induced an augmented anti-tumor immunity and a marked decrease in tumor vasculature. Antibody neutralization studies indicated that CXCL10 and CXCL11 moieties of ITIP were responsible for anti-angiogenesis and chemotaxis in antitumor response, respectively. These results indicated that integrating individual functional moieties of CXCL10 and CXCL11 into a chimeric chemokine could lead to a synergistic antitumor effect. Thus, this integration strategy holds promise for chemokine-based multiple targeted therapy of cancer.

Keywords: Chemokines, Combination regimen, Cancer therapy, Chemotaxis, Anti-angiogenesis

Introduction

Significant advances have been made in cancer therapy during the last decade as our understanding of tumor biology has evolved. It is now clear that tumor cells must escape from immune surveillance and depend on adequate blood supply to grow and progress [1, 2]. Immunotherapy aiming to reverse immune tolerance by recruiting immunocompetent cells and augmenting T cell immunity can subvert tumor growth without harming normal tissues [3, 4]. Anti-angiogenic therapy that target tumor vasculature can prevent or delay tumor growth and even promote tumor regression [5, 6]. Single modality manipulation has significant success in some therapeutic settings; however, the complexity of tumor progression process may often necessitate a multimodality approach that targets different aspects of tumor environment in order to generate the greatest clinical benefit [7]. Since anti-angiogenic therapy targets the tumor vasculature and prevents tumor growth beyond a certain size, whereas tumor immunotherapy targets the tumor cells and is capable of eliminating the remaining tumor mass, combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and tumor immunotherapy could be highly synergistic. In this regard, the chemokines represent promising targets for use in combination therapy, as they play an important role at the interface of angiogenesis and anti-tumor immunity [8, 9].

Chemokines constitute a large superfamily of homologous yet functionally divergent proteins that are involved in leukocyte trafficking and homing, angiogenesis [10], immune regulation, hematopoiesis and organ development [11, 12]. An increasing body of evidence has demonstrated that chemokines could exert antitumor effects via locally attraction and activation of tumor specific lymphocytes as well as suppression of tumor associated angiogenesis [8, 13, 14]. Of particular interest are two CXC chemokines, IFN-inducible T cell α chemoattractant (ITAC)/CXCL11 and IFN-inducible protein 10 (IP10)/CXCL10. CXCL10 and CXCL11 have potential in cancer intervention due to the ability to exert effects with functional specificity. Our previous data showed that forced expression of CXCL11 significantly inhibited tumor growth by recruiting T cells and enhancing immune responses [15]. Intratumoral CXCL10 reconstitution resulted in attenuation of neovascularization and led to reduced tumorigenicity [16]. CXCL11 has the highest agonist potency for CXCR3 and the most potent chemotactic activity for T lymphocytes during cell-mediated immunity among CXC chemokines [17, 18], whereas CXCL10 has a potent inhibitory effect on endothelial cell migration and neovessel formation [19]. Although both CXCL10 and CXCL11 could exert antitumor effects, they have functional superiority in suppressing tumor vasculature and enhancing tumor immunity, respectively.

Considering the functional superiority and distinct target cell compartments of each chemokine, combination of CXCL10 and CXCL11 may allow for integrating neovascularization-inhibiting and tumor-killing activity, thereby generating more effective anti-tumor effects. However, our preliminary data showed that pooling CXCL10 and CXCL11 together did not further enhance antitumor efficacy, even impaired antitumor ability of each chemokine alone. Given that the moieties of chemokines with similar structure were interchangeable [20], we designed a chemokine chimeric molecule, designated as ITIP, by incorporating respective functional moieties of CXCL10 and CXCL11. Here we report that the chimeric molecule had an impressive antitumor efficacy, markedly superior to its parent chemokines either alone or in combination. Further, we investigated the mechanisms underlying ITIP mediated antitumor activity.

Materials and methods

Cells

CT26 murine colon carcinoma, 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma, murine Lewis lung carcinoma (3LL), L929 mouse fibroblast and bEND.3 mouse brain capillary endothelial cell line were cultured in completed RPMI 1640 (GIBCO) medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Activated T cells generated by purifying T cells with CD3 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) from mouse splenocytes, culturing in the presence of Con A (5 μg/ml; Sigma), followed by propagation with IL-2 (100 U/ml; eBioscience) in fresh medium. Cells were used 6–12 days after addition of IL-2, and the medium was exchanged every 3 days. These cells are termed “Con A/IL-2-treated T cells” in the following. Stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing murine CXCR3 (mCXCR3) were generated as previously described [21]. The mCXCR3 gene in pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen) was transfected into CHO cells by electroporation, and selection was performed in G418 (800 μg/ml; GIBCO). Clones were obtained by limiting dilution, selected by their mCXCR3 expression, and are referred to as CHO/mCXCR3.

Animals

Female BALB/c mice (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from the Center of Experimental Animal of Fudan University and housed in the pathogen-free animal facilities of Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University. All animal experiments were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Medical Laboratory Animals (Ministry of Health, P. R. China, 1998) and the ethical guidelines of the Shanghai Medical Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

Design and molecular simulation of ITIP

By analysis the nucleic acid sequence of CXCL10 and CXCL11, there is a common enzyme site of Hind III in CXCL10 and CXCL11 and the sequence before Hind III including the whole sequence of N-terminal and N-loop region of chemokine CXCL11. If the sequence before Hind III of CXCL10 was replaced by the responding nucleic acid of CXCL11, the opening read frame of CXCL10 did not be changed. Then the sequence from N-terminal and N-loop region of CXCL11 and remaining sequence from CXCL10 were input into the computer and analyzed with Insight II work station. And the conformation of new molecule, which was named ITIP, was simulated with computer.

Expression and purification of ITIP

Total RNA was extracted from IFN-γ (1,000 U/ml; R&D) stimulated L929 cell line using Trizol (Invitrogen). The coding gene of CXCL11 before Hind III (Takara) including N-terminal and N-loop region and the coding gene after the Hind III of CXCL10 including β-sheet and C-terminal were amplified by PCR, respectively. The purified PCR products were then digested with Hind III and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Takara). The nucleotide sequence encoding the mature protein region of ITIP was amplified with PCR and then cloned into an expression plasmid pET-32a (Invitrogen). The final recombinant expression plasmid (ITIP-pET32a) was sequenced and subsequently the protein was expressed in E. coli. The recombinant fusion protein was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) using a nickel-chelating column (Pharmacia) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The N-terminal fusion partner was cleaved from the fusion protein with enterokinase (Novagen) according to the protocol supplied by manufacturer. Fractions containing pure ITIP were identified by Tricine–SDS-PAGE and western blotting analysis. The protein concentration was determined by the BCA (Pierce) protein assay with bovine serum albumin as standard. Then ITIP was filter sterilized, also tested for endotoxin, separated into aliquots, and frozen at −80°C.

Western blotting

Proteins were separated using Tricine–SDS-PAGE as described [22]. Separated proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Amersham Biosciences) and blocked with TBST containing 5% (w/v) non-fat milk for 2 h at room temperature. After overnight incubation at 4°C with anti-CXCL10, anti-CXCL11 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-ITIP antibody (Ab), the membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary Ab (DAKO). Signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescent reagents according to the manufacturer’s protocol (GE Healthcare). Polyclonal Ab directed against the purified ITIP protein was raised in rabbits. For priming, 700 μg of protein was used with complete Freund adjuvant and two booster doses of 500 μg each were administered with incomplete Freund adjuvant.

Chemotaxis assay

In vitro chemotaxis assays were performed in 48-well Boyden chamber with 5 μm pores size polycarbonate membranes (Corning Costar). Con A/IL-2-treated T cells that had previously incubated without or with 10 μg/ml mCXCR3-specific Ab or isotype Ab (Invitrogen) were transferred to upper chambers (1 × 105 cells/50 μl). The various concentrations ITIP protein was added in triplicate into the lower chamber. Recombinant CXCL10 and CXCL11 protein (PeproTech) were set for the positive control. After 4 h incubation, the numbers of cells that migrated into the lower chambers were numerated. The chemotactic index (CI) was calculated as the number of lymphocytes that migrated to the sample divided by the number of cells that spontaneously migrated to the negative control medium. In vivo lymphocyte migration assay was measured as described previously with minor modification [23]. Briefly, naïve BALB/c mice were given 1 × 107 Con A/IL-2-treated T cells intravenously, and ITIP or control chemokines (300 ng) were injected intradermally into discrete sites on the skin on the dorsum of the same mice. After 20 h, the skin around the injection sites was collected and sectioned for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The sections were observed using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-S microscope (Nikon) and the cells in stained sections were counted blinded in ten fields at a magnification of ×400.

Receptor internalization

Internalization assays were essentially conducted as reported previously [24]. Briefly, Con A/IL-2-treated T cells or CHO/mCXCR3 cells (4 × 105) were incubated with various concentrations of ITIP, CXCL11, CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 at 37°C for 30 min. After two washings with the ice-cold PBS, cells were incubated with the PE-conjugated CXCR3 Ab (R&D). CXCR3 expression was determined by flow cytometry using a FACScalibur instrument (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star). CXCR3 surface expression was expressed as a percent of baseline expression using the formula: [Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of tested cells/MFI of untreated cells] × 100.

Calcium influx assay

Calcium flux was performed as described previously [25]. Briefly, Con A/IL-2-treated T cells or CHO/mCXCR3 cells were loaded with 10 μM of the Ca2+ indicator fluo3-AM (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at 37°C, and analyzed by flow cytometry at FL1 (linear scale) versus time. Cells were acquired for 50 s before stimulation with agents, and 100 ng/ml stimuli (ITIP, CXCL11, CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11) were added in 50 s intervals to monitor calcium influx.

Wound-healing assay

Inhibition of endothelial cell migration was assayed using in vitro wound-healing assay that was performed essentially as described [26]. Briefly, confluent bEND.3 cells were injured by a deliberate scratch, washed and incubated with medium supplemented with bFGF (10 ng/ml; PeproTech) alone or in combination with the agents as indicated (100 ng/ml). After 48 h, cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde (v/v). Cells in the denuded zone (ten random fields) were quantified by light microscopy under 100× magnification in a blinded fashion.

Matrigel plug assay

Matrigel plug assay was carried out as described previously [19, 26]. Briefly, Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was mixed without, with 150 ng/ml bFGF alone or in combination with ITIP, CXCL11, CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11, each at a final concentration of 400 ng/ml. Matrigel alone or with bFGF, or with bFGF plus the test reagents (total vol 0.5 ml), was injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into the mid-abdominal region of the C57BL/6 mice. On day 14, plugs were removed and sectioned for H&E staining. Erythrocyte-containing vessels in the plugs was quantified by light microscopy under 400× magnification and expressed as the mean of ten random fields.

Therapeutic studies in murine tumor models

To show ITIP modification of tumor growth in vivo, mice were injected s.c. on day 0 with tumor cells including CT26 (1 × 105), 4T1 (1 × 105) or 3LL (5 × 105). Five-day-old established tumors were treated with intratumoral injection of 0.5 μg of ITIP, CXCL11, CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 three times a week for 2 weeks as previously described [27]. The amount of ITIP (0.5 μg) used for injection was determined by the in vitro biological activity data. Maximal chemotactic activity of ITIP for Con A/IL-2-treated T cells was 100 ng/ml. For in vivo evaluation of ITIP-mediated antitumor properties, we utilized fivefold more than this amount for each intratumoral injection. As for neutralization experiments, 24 h prior to ITIP treatment, and then three times a week, mice were injected intraperitoneal (i.p.) with 100 μg/dose of anti-CXCL10, anti-CXCL11 (R&D) or anti-ITIP or appropriate isotype Abs at equivalent doses for the duration of the experiment. The tumor volume was calculated using the formula V = 0.52 ab 2, with a as the larger diameter and b as the smaller diameter.

Immunofluorescence staining

For detection and analysis of lymphocytes infiltrated into tumor in situ, rabbit anti-mouse CXCR3, anti-CD3 (PE conjugate), anti-CD4 (FITC conjugate) and anti-CD8 (FITC conjugate) mAb (eBioscience) were used. FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (eBioscience) were used as secondary Ab for CXCR3 immunofluorescence. Quantitative studies of stained sections were performed independently in a blind fashion. Cell counts were obtained in ten randomly chosen fields. For staining of blood vessels, cryosections of tumors were stained for endothelial cells with a rabbit mAb specific for mouse CD31 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The secondary Ab was FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (eBioscience). CD31-staining vessels were quantified in ten random microscopic fields by an independent observer.

In vitro proliferation assay

Proliferation assay was performed as described previously with minor modification [28]. Briefly, CT26 cells were inactivated with mitomycin C (MMC, 100 μg/ml; Sigma) at 37°C for 1 h and then thoroughly washed before use. Splenocytes were isolated from each of the treatment groups, labeled with 5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen) and seeded in 96-well plates together with MMC-treated CT26 cells. After 72 h, cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytotoxicity assay and ELISA

To assess the ability of intratumoral injection of ITIP to induce tumor specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), splenocytes were isolated 1 day after the last injection into the tumors and restimulated with MMC-treated CT26 cells. After 5 days of culture, the in vitro restimulated splenocytes were quantified using a CFSE/7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; Invitrogen) cytotoxicity assay for their ability to lyse tumor cells as described previously [29]. The formula to calculate the percentage of specific target cell lysis is: % specific lysis = 100 × (% sample lysis − % basal lysis)/(100 − % basal lysis). For cytokine determinations, splenocytes were cocultured with MMC-treated CT26 cells at a ratio of 50:1 in a total volume of 5 ml. After an overnight culture, supernatants were harvested and examined for IFN-γ, IL-12, IL-4 and IL-10 (eBioscience) levels according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between experimental groups were analyzed for statistical significance by unpaired Student’s t test or by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test for the selected pairs using GraphPad Prism version 4.01 (GraphPad Software Incorporated). The survivals were compared by means of the log-rank test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

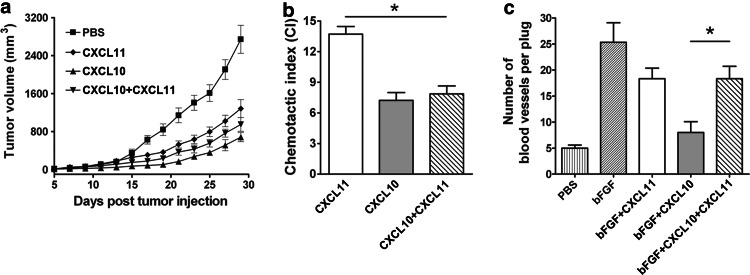

Pooling CXCL10 and CXCL11 together leads to a reduced antitumor effect

We first investigated the therapeutic efficacy of the combination regimen of CXCL11 with CXCL10 in murine CT26 colon carcinoma. As expected, tumor growth was significantly inhibited in CXCL11 or CXCL10 treated mice (Fig. 1a). Two chemokines in combination, however, did not lead to a further reduction in tumor size (Fig. 1a), which indicated that combination of CXCL10 and CXCL11 did not display synergistic antitumor effects. We next analyzed the chemotactic ability in chemotaxis assay and anti-angiogenic ability in Matrigel plug assay. When the two chemokines were used in combination, there was a significant decrease in CI compared with CXCL11 (P < 0.05; Fig. 1b) and an increase in blood vessel number compared with CXCL10 (P < 0.05; Fig. 1c), indicating that pooling of CXCL10 and CXCL11 led to functional impairment of each chemokine alone.

Fig. 1.

CXCL10 and CXCL11 in combination do not generate synergistic antitumor effects. a Growth curves of CT26 colon carcinoma after intratumorally (i.t.) administrating the indicated proteins. Five days after tumor implantation, mice were i.t. administrated with CXCL10 and CXCL11, either alone or in combination, three times per week for 2 weeks. Tumor volume was measured every other day (n = 10). b Chemotaxis index (CI) of Con A/IL-2-treated T cells in response to CXCL11, CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 (100 ng/ml) was assessed. c Blood vessels in the cross-sections of Matrigel plugs resected from mice treated with indicated chemokines 14 days after implantation were counted and averaged (n = 6). Data are representative of three separate experiments. Data represent mean ± SD. *P < 0.05

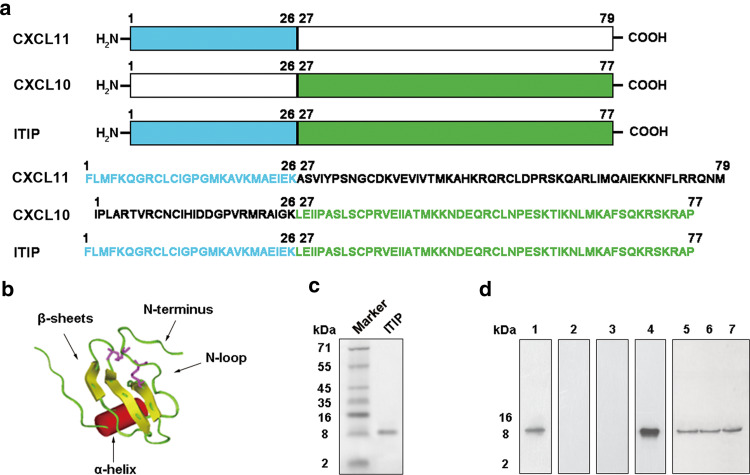

ITIP functions as a chemoattractant and an inhibitor of angiogenesis

A novel chemokine chimeric molecule, designated as ITIP, was composed of N-terminal and N-loop regions of CXCL11 and C-terminal region of CXCL10 (Fig. 2a). Molecular modeling with Insight II showed that ITIP retained the stable conformation of chemokine, including an N-terminus, an N-loop, a three-stranded β-sheet and a C-terminal α-helix (Fig. 2b). Then ITIP protein was produced using a pET-32a prokaryotic expression system in E. coli and purified by nickel chromatography. The purified ITIP protein was demonstrated as a single band with a predicted molecular mass of 8.7 kD by Tricine–SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2c). Western blotting analysis confirmed the presence of N-terminus of CXCL11 and C-terminus of CXCL10 in the purified protein (Fig. 2d). Anti-ITIP polyclonal antibody (Ab) prepared could react with commercial CXCL10 and CXCL11 protein, which further confirmed the right construction (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Construction and characterization of ITIP. a Schematic representation of ITIP and its amino acid sequences. b Dimensional conformation for ITIP. The molecular modeling calculation of ITIP was carried out using the Insight II software package. ITIP formed a chemokine-like conformation, including N-terminus, N-loop, three-stranded β-sheet, and C-terminal α-helix. c ITIP was purified using a nickel-chelating column and assayed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE. d The construction of ITIP was confirmed by western blotting with Abs against N-terminal (lane 1) or C-terminal (lane 2) of CXCL11, N-terminal (lane 3) or C-terminal (lane 4) of CXCL10. ITIP polyclonal Ab was prepared and tested by western blotting against CXCL11 (lane 5), CXCL10 (lane 6) and ITIP (lane 7) proteins

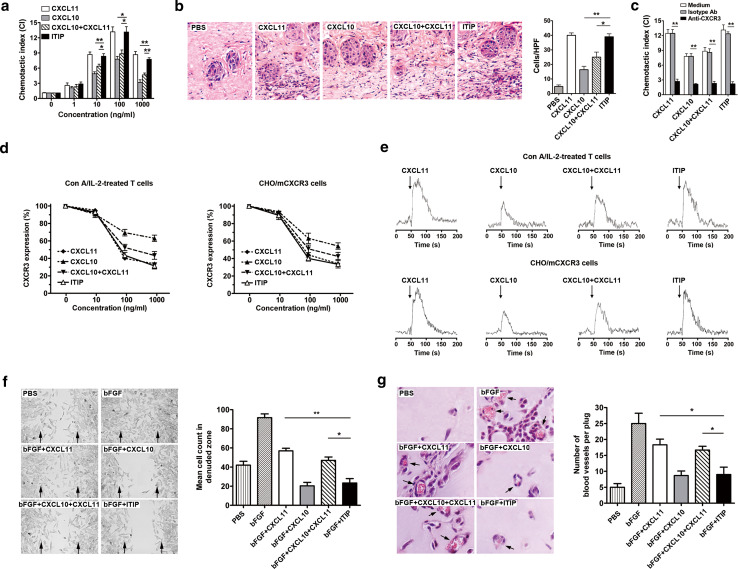

Considering ITIP was composed of functional moieties of CXCL10 and CXCL11, we first determined whether the functional properties were retained in the chimeric molecule. CXCL11 has the most potent chemotactic activity [30–32]. To evaluate whether the similar function was retained in ITIP, the chemotactic activity was determined by transwell chemotaxis and migration assay. We first compared the chemotactic potencies of ITIP, CXCL10 and CXCL11 on Con A/IL-2-treated T cells. A dose-dependent chemotactic response was observed with ITIP with the extent comparable to that of CXCL11 (Fig. 3a). Strikingly, the chemotactic activity of ITIP was more potent than CXCL10 alone or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 at concentration greater than 10 ng/ml (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). Consistently, in vivo migration assay showed that intradermal administration of ITIP and CXCL11 induced pronounced leukocyte accumulation into the skin, while CXCL10, either alone or in combination with CXCL11 were less effective (Fig. 3b). CXC chemokine receptor CXCR3 was the putative receptor for CXCL10 and CXCL11, we therefore assessed whether the chemotaxis process was specific for CXCR3. Con A/IL-2-treated T cells were pretreated with anti-CXCR3 Ab before their incubation with the agents in the transwell chemotaxis assay. Like CXCL10 and CXCL11, the chemotactic potency of ITIP was significantly blocked by CXCR3 Ab (P < 0.01), but not by isotype Ab (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

ITIP displays both chemotactic and anti-angiogenic activities. a Chemotaxis assay of Con A/IL-2-treated T cells in response to the indicated concentration of ITIP, CXCL11, CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 was performed. b Con A/IL-2-treated T cells were injected intravenously followed by the indicated proteins injected into discrete areas on the dorsum of the mouse. After 20 h, skin of the injection sites were collected, sectioned and stained with H&E (×400). Inflammatory cells were counted in ten high-power fields (HPF) and results were expressed as cell number per HPF. c CI of Con A/IL-2-treated T cells pre-incubated with CXCR3 Ab or isotype Ab in response to various chemokines (100 ng/ml) was assessed. d Dose-dependent internalization of CXCR3 on Con A/IL-2-treated T cells (left) or CHO/mCXCR3 cells (right) incubated with the indicated concentrations of stimuli for 30 min. e After the different stimuli (100 ng/ml) were added (arrow), dynamic changes in calcium on Con A/IL-2-treated T cells (top) or CHO/mCXCR3 cells (bottom) were monitored continuously by plotting the shift in the fluo3-AM fluorescence over a 150-s time course. f Effect of ITIP on bEND.3 migration into denuded zone 48 h after scraping. Cells were counted in denuded zone. Arrows indicate the wound edge (×100). g H&E-stained plugs resected from ITIP or its parent chemokines treated mice 14 days after implantation. Erythrocyte-filled blood vessels in sections were indicated by bright red staining (×400). Blood vessels in the cross-sections of Matrigel plugs were counted and averaged. Representative photomicrographs are shown. Individual experiment was conducted three times with similar results (n = 6). Data show the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

The agonist activity of the chimera was next tested by CXCR3 receptor internalization and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization after ligand exposure. Con A/IL-2-treated T cells were analyzed for CXCR3 surface expression by flow cytometry before and after ITIP exposure. As shown in Fig. 3d, left; ITIP induced a dose-dependent loss of CXCR3 expression on the cell surface. To further confirm ITIP-induced internalization of CXCR3, we stably transfected CHO cells with a murine CXCR3 cDNA expression construct, and transfectants were incubated with purified ITIP or related chemokines. A similar attenuated pattern was also found with CHO/mCXCR3 cells (Fig. 3d, right). Notably, at high concentrations (100 ng/ml, 1,000 ng/ml), ITIP exert similar effects on receptor internalization as CXCL11, but more potent than CXCL10 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11, in both cell types (Fig. 3d). CXCL11 is also more potent and efficacious than CXCL10 to induce Ca2+ changes [20]. To investigate whether ITIP could elicit calcium signaling as CXCL11, Con A/IL-2-treated T cells and CHO/mCXCR3 cells were then stimulated with indicated agents. Flow cytometric analysis showed that ITIP and CXCL11 were more efficient to induce Ca2+ influx as compared with CXCL10, or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 on both CXCR3 expressing cells (Fig. 3e). Collectively, these results indicated that ITIP retained high agonist potency as CXCL11.

CXCL10 has long been recognized as a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis [19, 33]. We next investigated whether ITIP retained robust angiostatic effects of CXCL10 in vitro and in vivo. In vitro wound-healing assay was performed by evaluating microvascular endothelial bEND.3 cell migration. Obvious migration of endothelial cells in the presence of bFGF was observed, which was highly suppressed by addition of ITIP and CXCL10 (Fig. 3f). ITIP was a comparable inhibitor as CXCL10, but more potent than CXCL11 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11, revealed by quantitative analysis (P < 0.05; Fig. 3f). To assess the anti-angiogenesis properties of ITIP in vivo, the extent of blood vessel invasion into Matrigel pellets inserted into mouse abdominal walls was examined. Blood vessel formation was apparent in cross-sections of Matrigel plugs after bFGF treatment (Fig. 3g). ITIP administration reduced vessel density by over 50% in the plugs. As shown in Fig. 3g, ITIP has similar angiostatic potency as CXCL10, but significantly higher potency than CXCL11 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 (P < 0.05). These data indicated that ITIP could act as a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis as CXCL10. Together, we obtained a chemokine chimeric molecule ITIP, which retained respective functional superiority of CXCL10 and CXCL11.

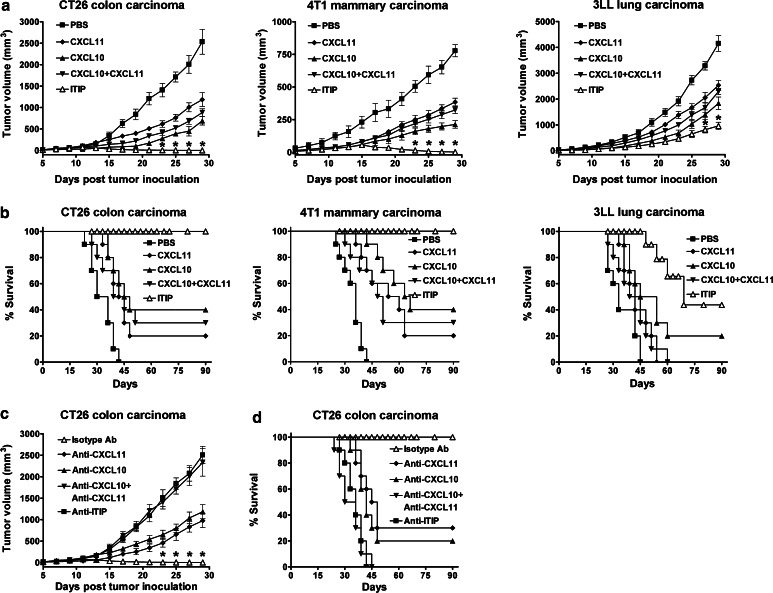

ITIP exhibits higher anti-tumor efficacy than its parent chemokines alone or in combination

We investigated the therapeutic efficacy of ITIP in murine CT26, 4T1 or 3LL tumor models. It was found that subjecting CT26 and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice to CXCL11, CXCL10 or both resulted in significant tumor growth delay. Strikingly, in CT26 and 4T1 tumor-bearing mice, administration of ITIP induced complete tumor regression (Fig. 4a) and significantly prolonged the survival of the animals compared with CXCL10 and CXCL11 treatment, either alone or combined (P < 0.01; Fig. 4b). In the 3LL tumor model, ITIP treatment displayed greater therapeutic efficacy as seen by longer tumor growth delay and survival compared with the parent chemokines (P < 0.05; Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

ITIP exhibits high anti-tumor efficacy. a Growth curves of CT26 colon carcinoma, 4T1 mammary carcinoma and 3LL lung carcinoma after administrating i.t. the indicated proteins. Five days after tumor implantation, mice were administrated i.t. with ITIP or its parent chemokines (0.5 μg/dose/mouse) three times per week for 2 weeks. Tumor volume was measured every other day. b Survival curves of mice bearing CT26 colon carcinoma, 4T1 mammary carcinoma and 3LL lung carcinoma after treatment. Survival was monitored for 90 days. c Growth curves of ITIP treated CT26 tumor after Ab neutralization. BALB/c mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) on day 0 with 1 × 105 CT26 cells. From day 5 on, ITIP protein (0.5 μg) was injected i.t. three times per week for 2 weeks. One day before ITIP administration, mice were given intraperitoneal (i.p.) the indicated Abs. Tumor volume was measured every other day. d Survival curves of ITIP treated CT26 tumor bearing mice after Ab neutralization. Survival was monitored for 90 days. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments (n = 10). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05

To determine the contribution of the respective moieties of ITIP to the antitumor response, their bioactivities were neutralized in ITIP treated mice. Anti-CXCL10 and anti-CXCL11 treatment each significantly yet partially blocked the antitumor effect of ITIP, while anti-ITIP and anti-CXCL10 plus anti-CXCL11 both abrogated the antitumor efficacy in CT26 tumor model (Fig. 4c, d). Together, these results demonstrated that ITIP produced potent anti-tumor benefit and both CXCL10 and CXCL11 moieties were required for ITIP mediated anti-tumor effects.

ITIP suppresses tumor progression via augmenting antitumor immunity and inhibiting angiogenesis

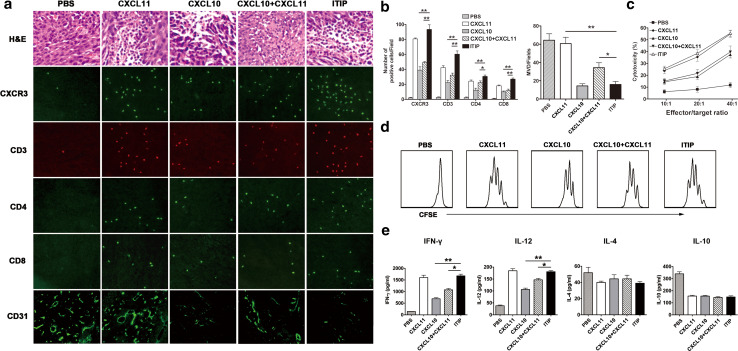

CT26 tumor model was used to elucidate the mechanisms by which ITIP suppressed tumor development. Pathological analysis of the CT26 tumor section 24 h after the last chemokine treatment revealed an obvious inflammatory infiltrate after administration with ITIP, CXCL11, CXCL10, and CXCL10 plus CXCL11, with CXCR3 expression on most of the inflammatory cells (Fig. 5a). To evaluate the infiltrated immune cell subsets, Abs against T cells, Natural Killer (NK) cells, macrophages and dendritic cells (DC) was used in immunofluorescence analysis. As shown in Fig. 5a, CXCR3+ and CD3+ T cells spread widely after ITIP or CXCL11 treatment. Quantitative analysis showed ITIP and CXCL11 attracted a significantly higher number of CXCR3+ and CD3+ lymphocytes than CXCL10 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 (P < 0.01; Fig. 5b), while comparable numbers of NK cells, macrophages, and DC were observed between these groups (data not shown). Further analysis showed that more CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes were recruited into the tumor site after ITIP and CXCL11 treatment (Fig. 5b). Visualization of the microvessels by CD31 immunostaining revealed that ITIP treated tumors had a remarkable reduction in vascular density which was comparable to that of CXCL10, but superior to CXCL11 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 (P < 0.05; Fig. 5a, bottom; b, right). The results demonstrated that ITIP simultaneously acted as an efficacious T cell chemoattractant and a potent angiogenesis inhibitor in the tumor context.

Fig. 5.

ITIP induces anti-tumor immunity and tumor associated anti-angiogenic activity. a BALB/c mice were injected s.c. on day 0 with 1 × 105 CT26 cells. After 5 days, ITIP or other control protein (0.5 μg) was injected i.t. three times per week for 2 weeks. One day after the last injection, tumors were surgically removed and sectioned for H&E staining and immunofluorescence staining against CXCR3, CD3, CD4 and CD8 (×400). Immunostaining with anti-CD31 Ab was used to detect microvessels in CT26 tumor (×200). b Quantification of CXCR3+, CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells (left) and CD31+ blood vessels (right) in CT26 tumors. MVD denotes microvessel density. c Cytotoxicity assay. Splenocytes were isolated 1 day after the last injection, and cocultured with MMC-treated CT26 cells. After 5 days of culture, the in vitro CTL activity of the restimulated splenocytes was assessed against CT26 cells using a CFSE/7-AAD assay. d In vitro proliferation assay. One day after the last injection, splenocytes were isolated and labeled with CFSE, then cocultured with MMC-treated CT26 cells for 72 h and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE dilution. e Cytokine assay. Splenocytes were isolated and cocultured with MMC-treated CT26 cells for 24 h. The cell culture supernatant was analyzed for IFN-γ, IL-12, IL-4 and IL-10 expression by ELISA. The photomicrographs are representative of three independent experiments. An individual experiment was conducted three times (n = 6). Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Next, the cellular immune responses such as T cell proliferation, cytotoxic activity and cytokine secretion after ITIP treatment were examined. As shown in Fig. 5d, when the splenocytes from treated mice were cultured with inactivated CT26 cells, both ITIP and CXCL11 treatment resulted in more vivid specific T cell proliferation than the other chemokines. Splenocytes from ITIP treated mice exhibited more potent specific lysis of CT26 target cells compared to CXCL10 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 treated mice (Fig. 5c). In vitro secretion of IFN-γ and IL-12 from splenocytes of ITIP treated mice when stimulated with inactivated CT26 cells were higher than that of CXCL10 or CXCL10 plus CXCL11 treated mice (P < 0.05), while no significant differences were observed with the production of IL-4 and IL-10 between these groups (Fig. 5e), indicating that ITIP enhanced a Th1-biased immune response. These data demonstrated that ITIP exerted antitumor function via inducing potent Th1 immune response.

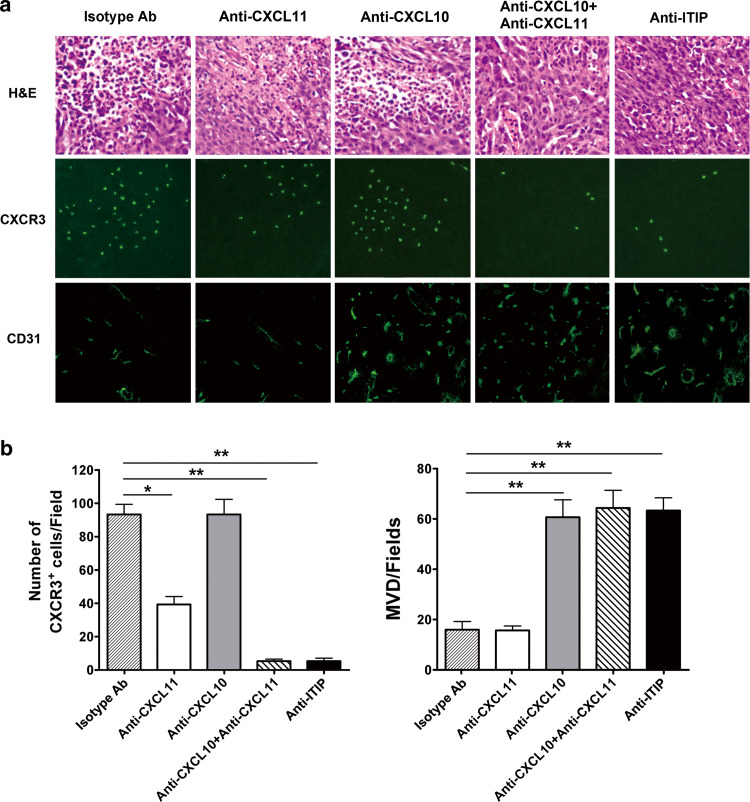

We further evaluate the contribution of the respective moieties of CXCL11 and CXCL10 in ITIP mediated tumor suppression, anti-ITIP Ab or anti-CXCL10 plus anti-CXCL11 Ab was pretreated and resulted in a remarkable decrease in the local inflammatory infiltration, especially an almost complete loss of CXCR3+ cells, and an increase of microvessel density, indicating that both CXCL10 and CXCL11 moieties made its work in ITIP-mediated antitumor activity (Fig. 6a). A significant decrease in CXCR3+ cell infiltration after CXCL11 blockade suggested a critical role of the CXCL11 moiety in chemotaxis, and a pronounced increase in microvessel density after anti-CXCL10 treatment revealed an indispensable role of the CXCL10 moiety in anti-angiogenesis (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6.

CXCL10 and CXCL11 moieties are responsible for the potent antitumor activity of ITIP. a BALB/c mice were injected s.c. on day 0 with 1 × 105 CT26 cells. From day 5 on, ITIP protein (0.5 μg) was injected i.t. three times per week for 2 weeks. 24 h before ITIP administration, mice were given i.p. the indicated Abs. One day after the last ITIP administration, tumors were surgically removed, sectioned for H&E staining (top; ×400) and CXCR3 (middle; ×400) and CD31 (bottom; ×200) immunofluorescence staining. b CXCR3+ cells (left) and microvessels (right) were quantitatively analyzed as above. Three independent experiments were performed, and similar results were obtained (n = 8). Representative photomicrographs of the tumor are shown. Data are expressed as means ± SD. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Discussion

A pool of chemokines may compromise individual antitumor activities if they share the common receptor. Numerous studies of structure–activity relations have shown that the N-loop region is responsible for the receptor recognition, and the NH2-terminal region triggers the receptor. Clark-Lewis et al. [31, 34] show that the amino acid residues in the N-loop region are largely responsible for the higher activity of CXCL11 compared with CXCL10. On the other hand, chemokines exert anti-angiogenic effects directly on endothelial cells via the C-terminal domain [35]. Chemokines adopt a remarkably conserved structure consisting of N terminus, N-loop, three-stranded β-sheet, and C-terminal α-helix [12, 36]. Given that the moieties of chemokines with similar structure were interchangeable [20], we designed a novel chemokine chimera ITIP by substituting the N-terminal and N-loop region of CXCL10 with those of CXCL11. Key findings of the present study include: (1) both building blocks of ITIP retained their functionality after chimerization; (2) administration of ITIP exhibited antitumor effects, and significantly, generated therapeutic efficacy that was substantially greater than that of either of its component parts, either individually or in combination; and (3) the high therapeutic efficacy of ITIP was due to CXCL11 moiety induced CXCR3+ cells chemotaxis and CXCL10 moiety mediated anti-angiogenesis.

We demonstrated that pooling CXCL10 and CXCL11 together led to functional impairment and did not display synergistic antitumor efficacy. The mechanistic explanations remain unclear. It has been well documented that both CXCL10 and CXCL11 act on the chemokine receptor CXCR3 [18, 20, 37]. Gαi2 and Gαi3, two members of the Gαi/o protein family, are involved in CXCR3-mediated signaling, presumably with Gαi2 activating downstream effectors to drive T cell migration. Yet, Gαi3 inhibits Gαi2 activation through competing for or sterically interfering with Gαi2 binding to the CXCR3 receptor. The amplitude of a CXCR3-induced signal is determined by the nature and affinity of the ligands as well as the interplay of Gαi2 and Gαi3 with the receptor [37]. It could be speculated that CXCL10 and CXCL11 in combination provide conditions that might be optimal for Gαi3 binding to the CXCR3 receptor, sterically hindering Gαi2 activation. This might be the reason why CXCL10 and CXCL11 administered together fail to have an additive effect.

A pivotal finding in the present study is that the chimeric molecule proved to be far more therapeutically active in the three tumor models than its component protein parts, when the latter were administered as soluble entities either alone or in combination. In CT26 and 4T1 tumor models, only ITIP induced tumor regression, whereas CXCL11 and CXCL10 individually or in combination prolonged tumor growth delay. We observed that ITIP treatment did not induce tumor regression in 3LL lung carcinoma. Though we could not give a precise explanation, it is of great interest for us to explore the mechanisms in the future as similar phenomena were also observed in several other studies [13, 38–40]. The encouraging results from this study suggest that a multifunctional therapeutic chemokine chimera could perturb tumor environment from multiple angles and achieve a potent anti-tumor therapeutic effect.

While ITIP may hold promise for cancer therapy, certain safety issues need to be solved. Given the chimeric molecule created a new epitope in the junction; we have determined whether Ab was induced after ITIP treatment. No Ab reactive with ITIP in the sera can be determined by ELISA (data not shown). Furthermore, the toxicity of ITIP was also evaluated after long-term administration in a separate study. Gross changes, such as weight loss, ruffling of fur, and changes in behavior were not seen in ITIP treated mice. No significant difference in survival was observed between ITIP and PBS treated mice. In addition, no obvious pathological changes of liver, kidney, lung, spleens, etc. were found by the microscopic examination (data not shown).

In summary, our results indicate that chemokine-based chimera can generate an impressive antitumor effect through the enhancement of Th1 cell-mediated immune response and anti-angiogenesis. The integration strategy of functional moieties represents a promising approach in the treatment of cancer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lin Xu, Zhenggang Jiang, Bo Gao for technical assistance and valuable suggestions, Peng Hu for his help with animal studies and Feng Zhang for FACS advice. This research was funded in part by China NSFC grant (30890141, 30872355), the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (2007CB512401) and Program for Shanghai Outstanding Medical Academic Leader (LJ06011).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039–2049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougan M, Dranoff G. Immune therapy for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Disis ML, Bernhard H, Jaffee EM. Use of tumour-responsive T cells as cancer treatment. Lancet. 2009;373(9664):673–683. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60404-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heath VL, Bicknell R. Anticancer strategies involving the vasculature. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(7):395–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benny O, Fainaru O, Adini A, Cassiola F, Bazinet L, Adini I, Pravda E, Nahmias Y, Koirala S, Corfas G, D’Amato RJ, Folkman J. An orally delivered small-molecule formulation with antiangiogenic and anticancer activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(7):799–807. doi: 10.1038/nbt1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma WW, Adjei AA. Novel agents on the horizon for cancer therapy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(2):111–137. doi: 10.3322/caac.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homey B, Muller A, Zlotnik A. Chemokines: agents for the immunotherapy of cancer? Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(3):175–184. doi: 10.1038/nri748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strieter RM. Chemokines: not just leukocyte chemoattractants in the promotion of cancer. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(4):285–286. doi: 10.1038/86286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerard C, Rollins BJ. Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(2):108–115. doi: 10.1038/84209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen SJ, Crown SE, Handel TM. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:787–820. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fushimi T, O’Connor TP, Crystal RG. Adenoviral gene transfer of stromal cell-derived factor-1 to murine tumors induces the accumulation of dendritic cells and suppresses tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2006;66(7):3513–3522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Struyf S, Burdick MD, Peeters E, Van den Broeck K, Dillen C, Proost P, Van Damme J, Strieter RM. Platelet factor-4 variant chemokine CXCL4l1 inhibits melanoma and lung carcinoma growth and metastasis by preventing angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(12):5940–5948. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu Y, Yang X, Xu W, Wang Y, Guo Q, Xiong S. In situ expression of IFN-gamma-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant in breast cancer mounts an enhanced specific anti-tumor immunity which leads to tumor regression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(10):1539–1549. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0296-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arenberg DA, Kunkel SL, Polverini PJ, Morris SB, Burdick MD, Glass MC, Taub DT, Iannettoni MD, Whyte RI, Strieter RM. Interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) is an angiostatic factor that inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tumorigenesis and spontaneous metastases. J Exp Med. 1996;184(3):981–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meiser A, Mueller A, Wise EL, McDonagh EM, Petit SJ, Saran N, Clark PC, Williams TJ, Pease JE. The chemokine receptor CXCR3 is degraded following internalization and is replenished at the cell surface by de novo synthesis of receptor. J Immunol. 2008;180(10):6713–6724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colvin RA, Campanella GS, Sun J, Luster AD. Intracellular domains of CXCR3 that mediate CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(29):30219–30227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angiolillo AL, Sgadari C, Taub DD, Liao F, Farber JM, Maheshwari S, Kleinman HK, Reaman GH, Tosato G. Human interferon-inducible protein 10 is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;182(1):155–162. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark-Lewis I, Mattioli I, Gong JH, Loetscher P. Structure-function relationship between the human chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligands. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(1):289–295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campanella GS, Lee EM, Sun J, Luster AD. CXCR3 and heparin binding sites of the chemokine IP-10 (CXCL10) J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):17066–17074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212077200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kda. Anal Biochem. 1987;166(2):368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McColl SR, Mahalingam S, Staykova M, Tylaska LA, Fisher KE, Strick CA, Gladue RP, Neote KS, Willenborg DO. Expression of rat I-TAC/CXCL11/SCYA11 during central nervous system inflammation: comparison with other CXCR3 ligands. Lab Invest. 2004;84(11):1418–1429. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauty A, Colvin RA, Wagner L, Rochat S, Spertini F, Luster AD. CXCR3 internalization following T cell-endothelial cell contact: preferential role of IFN-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (CXCL11) J Immunol. 2001;167(12):7084–7093. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dagan-Berger M, Feniger-Barish R, Avniel S, Wald H, Galun E, Grabovsky V, Alon R, Nagler A, Ben-Baruch A, Peled A. Role of CXCR3 carboxyl terminus and third intracellular loop in receptor-mediated migration, adhesion and internalization in response to CXCL11. Blood. 2006;107(10):3821–3831. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang G, Fahmy RG, diGirolamo N, Khachigian LM. Jun sirna regulates matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression, microvascular endothelial growth and retinal neovascularisation. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 15):3219–3226. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillinger S, Yang SC, Zhu L, Huang M, Duckett R, Atianzar K, Batra RK, Strieter RM, Dubinett SM, Sharma S. EBV-induced molecule 1 ligand chemokine (ELC/CCL19) promotes IFN-gamma-dependent antitumor responses in a lung cancer model. J Immunol. 2003;171(12):6457–6465. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng G, Liu S, Wang P, Xu Y, Chen A. Arming tumor-reactive T cells with costimulator B7-1 enhances therapeutic efficacy of the T cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(13):6793–6799. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecoeur H, Fevrier M, Garcia S, Riviere Y, Gougeon ML. A novel flow cytometric assay for quantitation and multiparametric characterization of cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol Methods. 2001;253(1–2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(01)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole KE, Strick CA, Paradis TJ, Ogborne KT, Loetscher M, Gladue RP, Lin W, Boyd JG, Moser B, Wood DE, Sahagan BG, Neote K. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC): a novel non-ELR CXC chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to CXCR3. J Exp Med. 1998;187(12):2009–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proost P, Mortier A, Loos T, Vandercappellen J, Gouwy M, Ronsse I, Schutyser E, Put W, Parmentier M, Struyf S, Van Damme J. Proteolytic processing of CXCL11 by CD13/aminopeptidase N impairs CXCR3 and CXCR7 binding and signaling and reduces lymphocyte and endothelial cell migration. Blood. 2007;110(1):37–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-049072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox JH, Dean RA, Roberts CR, Overall CM (2008) Matrix metalloproteinase processing of CXCL11/I-TAC results in loss of chemoattractant activity and altered glycosaminoglycan binding. J Biol Chem. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800266200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Gomperts BN, Belperio JA, Keane MP. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16(6):593–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox JH, Dean RA, Roberts CR, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of CXCL11/I-TAC results in loss of chemoattractant activity and altered glycosaminoglycan binding. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(28):19389–19399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luster AD, Greenberg SM, Leder P. The IP-10 chemokine binds to a specific cell surface heparan sulfate site shared with platelet factor 4 and inhibits endothelial cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 1995;182(1):219–231. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez EJ, Lolis E. Structure, function, and inhibition of chemokines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:469–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091901.115838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson BD, Jin Y, Wu KH, Colvin RA, Luster AD, Birnbaumer L, Wu MX. Inhibition of G alpha i2 activation by G alpha i3 in CXCR3-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9547–9555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610931200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao JM, Wen YJ, Li Q, Wang YS, Wu HB, Xu JR, Chen XC, Wu Y, Fan LY, Yang HS, Liu T, Ding ZY, Du XB, Diao P, Li J, Kan B, Lei S, Deng HX, Mao YQ, Zhao X, Wei YQ. A promising cancer gene therapy agent based on the matrix protein of vesicular stomatitis virus. FASEB J. 2008;22(12):4272–4280. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-110049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Finger C, Alvarez-Vallina L, Cichutek K, Buchholz CJ. Chronic gene delivery of interferon-inducible protein 10 through replication-competent retrovirus vectors suppresses tumor growth. Cancer Gene Ther. 2005;12(11):900–912. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fushimi T, Kojima A, Moore MA, Crystal RG. Macrophage inflammatory protein 3alpha transgene attracts dendritic cells to established murine tumors and suppresses tumor growth. J Clin Invest. 2000;105(10):1383–1393. doi: 10.1172/JCI7548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]