Abstract

Tumor escape from the host immune response remains the major problem holding the development of immunotherapies for cancer. In this review, congenic mouse lines are discussed that differ dramatically in their ability to respond to tumors tested and, thereby, to survive or to succumb to the tumor and/or its metastases. This ability is under the control of either MHC class I or nontrivial MHC class II β genes expressed in a small subpopulation of antigen-presenting cells. Two hypotheses can explain the results obtained so far: (1) emergence of tumor cell variants that escape the host immune response in morbid mice but are eliminated in survivors, and (2) tumor-induced immunosuppression, which is either efficient or not, depending on the congenic line used. It is argued that further experimentation on these congenics will allow to choose the correct hypothesis, and to characterize the mechanism(s) of elimination of minimal residual disease and prevention of tumor escape by the immune system of survivors as well as the reason(s) for its failure in morbid mice. It is also argued that the use of these models will substantially increase the chance to resolve the controversy of poor correlation of immunotherapy testing in mice with clinical results.

Keywords: Cancer, Immune escape, Macrophages, T cells, MHC, Somatic mosaicism

Introduction: some tumors evade host immune responses

Cancer cells show gene expression profiles that distinguish them from normal cells from which the tumor originated [1]; furthermore, there are reports demonstrating that early tumor stages, which are relatively indolent, and aggressive metastatic tumors may have distinct patterns of expression of multiple genes [2–7]. Consequently, local immune responses may take place against some normal gene products, which are self-antigens (self-Ags) overexpressed by tumor cells [8, 9]. It has also been demonstrated that structural gene mutations occur in tumor cells and that both human and animal malignant tumors display mutated Ags whose epitopes are different from self [10–12]. It has been known for almost half a century that these tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) can be attacked by the host immune system [13–15], providing opportunities for active (vaccination against cancer) and adoptive immunotherapy, and for boosting the antitumor response by various means [16–20]. Studies of regressive human tumors [21, 22] demonstrated that an Ag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response could be efficient against an established tumor. However, the presence of antitumor CTLs is not associated with eradication of the tumor in many human patients, in whom residual cancer cells, i.e. dormant cells and micrometastases (or nodal metastasis), resist immunotherapies [23–30] as well as any other treatment. Their tumors evade host immune responses, a phenomenon known as ‘immune escape’, or ‘tumor escape’. Several hypotheses have been offered to explain tumor escape. Inhibitory mechanisms of antitumor immunity that have been described seem to be responsible for the uncontrolled tumor growth [29–32]. It has been demonstrated that the malignant tumors are genetically unstable, become saturated with random gene mutations [33], and evolve resistant variants under selective pressure from the immune attack [34–37]; these resistant variants are capable to grow in the presence of the host immune response that seems to target a wrong antigen on the tumor cell surface. Recently, a new hypothesis of immunoediting has been proposed, in which the immune response to a developing tumor does not always result in protection but, rather, affects its antigenic makeup and can favor the emergence of resistant tumor cell variants [38, 39]. Despite undeniable advances in our knowledge and understanding of antitumor immunity, the problem—how to prevent tumor escape?—has not yet been solved.

Another unresolved problem of cancer immunology is poor correlation between the results obtained on mice and clinical results. Using mouse models, an impressive variety of techniques have been developed to amplify antitumor immune responses, including natural killer (NK) cells, cytokine administration, genetically engineered cytokine-secreting tumor cells, immunization with tumor-derived antigenic peptides supplemented with various adjuvants, peptide-pulsed dendritic cells, and variations of the above. But, as mentioned, the immunotherapies, which worked well in mice, are rarely effective in humans [40, 41]. This discrepancy has never been adequately explained beyond pointing out that inbred mice are genetically homozygous while humans are heterozygous. However, it is well known that heterozygosity is associated with vigor and that heterozygosity for certain genetic loci may result in improved resistance to diseases [42, 43]. Therefore, heterozygous humans are expected to be more resistant to tumor escape than feeble inbred mice, which is not true. Perhaps, there is a more specific reason for this horrendous discrepancy?

Recently, an ostensibly counterintuitive idea of a gene for resistance to immune escape has been tested, and found true. A simple question was asked, why in some cases the tumor is eradicated by the host’s immune response while in other cases it continues to grow in the face of it? Few studies addressed this question directly in humans because it is difficult to provide a genetically matched control for each case. A possible answer has been suggested by studies in inbred mice [44–48], which showed that a host gene(s) controls the efficiency of the antitumor immune response. Highly unusual genes responsible for resistance/susceptibility to the tumor and/or its nodule metastases have been cloned from mice and characterized [49]. Paradoxically, some alleles of these genes have been found segregating in otherwise genetically homogenous inbred mice; some were fixed in congenics produced from original survivors. Homozygous mice carrying different alleles of these genes have been used to study immune responses to the tumor. Congenic mouse lines that are either resistant or unusually susceptible to certain malignant tumors and/or their nodule metastases appear to be comparable to the two groups of cancer patients, those that survive or die from their disease, correspondingly. If this proposal is correct, genetic factor(s) involved and the mechanism(s) of protective response against minimal residual disease in humans must be defined before any further progress in immunotherapy of cancers can be made. The purpose of this short review is to summarize what is currently known about the protective and the nonprotective immune responses against the tumor in these new mouse models and to discuss their possible future uses.

Mouse gene mutations for resistance or extraordinary susceptibility to tumor escape

Inbred mice succumb to growing malignant tumors, including endogenous (or autologous) and transplantable tumors that originated in a mouse of the same strain. As any biological function, this may change through a gene mutation. Spontaneous gene mutations for resistance or increased susceptibility to a malignant tumor are rare, unpredictable, random, stochastic events. Yet, each event may provide valuable information about the biological function controlled by the gene involved, which otherwise would remain inaccessible. Random gene mutations affecting a specific function have been used for decades in almost every area of biological research, and the results obtained on them proved highly reliable, both in various model organisms and in humans. In immunology, mouse mutants and human ‘variants‘ were used, for instance, to characterize peptide binding regions of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules [50]. Mouse mutations for resistance or unusually high susceptibility to a malignant tumor or its metastases are discussed below.

H2 is the mouse MHC; H2 dm1 is a spontaneous MHC class I mutation found in a B10.D2 (H2 d) mouse because its carriers rejected standard skin grafts [51]. The dm1 mutation resulted in a hybrid gene, containing the 5′ part of the D d (that encodes the antigen-binding groove of the protein molecule), and the 3′ part of the L d genes fused within their third exon while the relatively large chromosomal segment between these two genes is deleted [52, 53]. Mouse D d and L d genes are tightly linked and closely related to each other. The standard B10.D2 (H2 d) and the mutant B10.D2–H2 dm1 strains are a congenic pair on the C57BL/10Sn (H2 b) genetic background. Heterozygous carriers of this mutation, H2 dm1/H2 b, were able to recover from the Friend retrovirus-induced erythroleukemia (Table 1) while the normal heterozygous mice, H2 d/H2 b, died from this disease, and the H2 b/H2 b homozygotes are resistant to the disease [46, 47]. The principal finding with the dm1 was that a germline MHC-I gene mutation could prevent tumor escape in mice. Physical association of the H2–Ld molecule with its ligands (antigenic peptides) is exquisitely specific, contributing to determinant selection by the H2 d haplotype [54]; since the antigen-binding region of the Ld molecule is absent in the dm1 mutant, the resulting alterations in ligand selection and specificity of immune responses to viral tumor antigens may explain the different outcomes of the disease in H2 d/H2 b and H2 dm1/H2 b mice. However, to determine the genetic basis for the resistance with higher precision, the role of each gene located within the chromosome segment deleted by the dm1 mutation should be studied. Unfortunately, the immunological mechanism of spontaneous regression of these tumors in H2 dm1/H2 b mice has not been characterized in full detail.

Table 1.

Mouse gene mutations for resistance to malignant tumors

| Mutant and normal strain | Mutant gene(s) | Resists initial tumor inocul | Spont regres of the tumor | Affects metastasis | Normal skin graft rejection | Immune cells attacking the tumor | Antigen-binding molecule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dm1, B10.D2 | H2-D·L hybrid genea | NA | Yes | NT | Yes | NT | MHC-I |

| SR/CR, BALB/c | NTb | Yes | Yes | NT | NT | MΦ, innate | NT |

| S-31, B6 | Aβ[5·4]s5b* hybrid genec | Yes | No | Yes | No | MΦB, B′, CTL | MHC-II |

| S-27, B6 | Aβ4 b Aβ6 w302*d | Yes | No | Yes | No | MΦB, B′, CTL | MHC-II |

| S-87/2, B6 | Aβmutant not sequencede | Yes | No | Yes | No | MΦB, B′ | MHC-II |

NA not applicable, NT not tested. Mutant, first--, and normal strain (congenic partner), second --; dm1, H2 dm1 ; B6, C57BL/6J; dm1 mutation affected resistance to endogenous Friend retrovirus-induced erythroleukemia; other mutations affected immune responses to transplantable tumors. Mutant genes: H2, histocompatibility-2; Aβ4-6 are nontrivial MHC-II β-chain genes [49]; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; normal B6 mice were Aβ 4 b 5 s5/Aβ 4 b 5 s5 homozygotes; mutants S-27, S-31, and S-87/2 were homozygous for the genes(s)/allele(s) shown; a star (*) indicates molecular instability of the gene(s) in somatic cells of a carrier mouse. Resistance to the initial tumor inoculum: in the SR/CR mutant, resistance to 2×106 sarcoma S180 cells injected into peritoneal cavity (ip) and to eight other tumors of BALB/c origin; in S-mutants, at least a ten-time increase in TD50 (the threshold cell dose for a 50% take) in comparison with the normal strain; tumors: S-31 and S-27, transplantable lymphoma EL4 of B6 mice injected ip; S-87/2, transplantable rhabdomyosarcoma MCA/77-23M (metastatic) of B6 mice, ip. Spontaneous regression of the tumor: the tumor begins to grow rapidly, but then the host destroys it and recovers without any treatment. Affects metastasis: the ability to survive in a spontaneous metastasis assay of the tumor indicated above. Normal skin graft rejection: the ability/inability to reject the indicated congenic partner skin grafts; however, all S-mutants do reject skin allografts from unrelated mice. Immune cells: MΦ, macrophages; MΦB is a subpopulation of MΦ expressing Aβ4, Aβ5 or Aβ6 genes; B′ cell is a small subpopulation of B cells expressing these genes; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes. References: dm1 [46, 47, 51–53], SR/CR [48, 64], S-31, S-27 and S-87/2 [44, 45, 49, 56, 106], and our unpublished results.

aIn the H2 dm1 mutant, a hybrid gene is found containing the 5′ part of the D d and the 3′ part of the L d genes fused within their third exon while the segment between the two genes is deleted [52, 53].

bIn progeny of this mutant resistance segregated as a single locus that remained unidentified.

cThis hybrid gene contains the 5′ part of the Aβ 5 s5 and the 3′ part of the Aβ 4 b genes fused within the stretch of bases between codons 86 and 174 so that the peptide binding region of its product is encoded by the s5 allele; its product is the β chain of a functional MHC class II molecule [49].

dPossibly also the H2-Ab b gene instability [56].

e Aβ gene mutation in S-87/2 mice has been revealed by Southern hybridization with corresponding probes, but the genes involved have not been sequenced

Several mutations for resistance to transplantable tumors in the C57BL/6J (B6) mouse strain were found in screens, specifically designed for the purpose [44, 45]. Mutant mice remained histocompatible with the strain of origin: skin grafts exchanged between mutant and normal mice were not rejected. These mice were designated S-mutants (‘S’ comes from ‘survivors’). The number of tumor cells required for 50% take by the tumor (TD50) was substantially increased in S-mutants as compared to B6 mice while some of these mutants also strongly resisted metastases from the same tumor in a spontaneous metastasis assay (Table 1). It was entirely unexpected, however, that some of S-mutants, which resisted the primary tumor inoculum, have been found to be more susceptible to metastases from the same tumor than the standard B6 mice (Fig. 1). Genes for resistance or susceptibility to the tumor and its metastases in some of S-mutants have been identified—they were novel and single exon MHC-II β genes, designated as Aβ4-8 (8Ψ is a pseudogene). Their protein coding region was similar to or identical with the classical H2-Ab cDNA encoding the β chain of MHC-II molecules [49]; β chain associates with an α chain (genes encoding this α chain have not yet been studied) to form functional MHC-II molecules on Ag-presenting cells (APC). However, promoters and/or signal sequences of Aβ4-7 genes were unrelated to the Ab sequence. For this reason, the expression pattern of these nontrivial MHC-II β genes differed significantly from that of the classical Ab gene: reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) studies revealed that they are expressed at a very low level by a subpopulation of macrophages (MΦs), designated as MΦB, and a small subpopulation of B cells, designated as B′, but not by any other cell type in the body, nor by tumor cells studied. The Aβ4 b antigen was detectable by allele-specific monoclonal antibodies on the cell surface of MΦBs and B′ cells of knockout mice lacking classical MHC-II molecules, albeit at a very low quantity. In resistant mice, MΦBs invaded the tumor and initiated protective antitumor responses. Previous studies indicated that MΦs may contribute to tumor rejection, but, in other cases, they may be bystanders or may promote tumor growth [55]; work by Liu et al. [49] suggested that different effects are attributable to different subpopulations of MΦs and that these effects are genetically determined. Mutant Aβ4-6 genes were shown to be molecularly unstable in somatic cells of mice carrying them, including mutant strains S-27 (genes Aβ4 b 6 w302), S-31 (hybrid gene Aβ[5·4] s5b) and S-87/2 (gene not identified). This instability resulted in somatic mosaicism of nontrivial MHC-II molecules in their APCs; mechanisms of this instability will be discussed later in this review. Some results suggested that the classical H2-Ab b gene was also unstable in somatic cells of the S-27 mutant [56]; another mutant, S-87/1, was found that also carried the Aβ6 w302 gene and was similar to S-27 in responses to tumors while its H2-Ab b gene appeared to be stable [49]. The mechanism of the Ab b gene instability in S-27 and its role in responses to the tumor has not been characterized. No germ line mutations of the Aβ7 gene have been found. In the S-27 mutant, the nucleotide sequence of the protein coding region of a nontrivial Aβ6 w302 gene was very similar to the allele Ab w30.1 born on t Tuw10 chromosome of a wild mouse. Genetic analysis showed that resistance to the EL4 tumor inoculum in mutants S-27 and S-31 maps into the t region on Chromosome 17 [45]; the Aβ 6 w302 gene locus appeared to map also into the t region. Nontrivial Aβ genes in other S-mutants seem to map close to Ednrb, formerly piebald (s), on Chromosome 14, and close to Myo5a, formerly dilute (d), on Chromosome 9. Interestingly, a quantitative trait locus (QTL) associated with the severity of tuberculosis in mice has been mapped to the same region of Chromosome 9, and another QTL was mapped to the t region on Chromosome 17 [57] while mycobacteria are known to evade host immune responses [58]; but, of course, these may be simply coincidences.

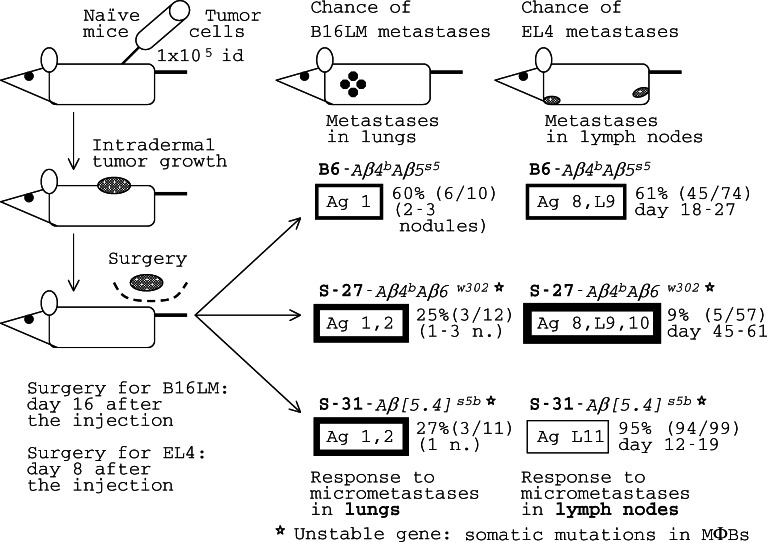

Fig. 1.

Responses of REST congenics to micrometastases are tumor-specific and are under the control of Aβ 4-6 genes. B16LM melanoma and EL4 lymphoma spontaneous metastasis assay; id, intradermal injection. Implied target antigens (Ag) on B16LM tumor cells were designated #1 for B6 immune cells, and 1 and 2 for S-27 and S-31 immune cells. More details of mouse responses to EL4 will be presented in Fig. 6. Fatter frames stand for stronger responses against metastases. Nontrivial Aβ4-6 genes encode the β chain of MHC-II molecules expressed by a subpopulation of macrophages (MΦBs) and a subpopulation of B cells (B′). A star (asterisks) indicates molecular instability of the Aβ gene(s) resulting in somatic mosaicism, that is a mosaicism in the MΦB cell population in a carrier mouse. The resistance to the tumor is attributable both to MΦBs and cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) primed by MΦBs and capable to destroy tumor cells. Based on [44, 45, 49], and our unpublished results

Before Aβ4-6 genes were characterized, Albert et al. [59] PCR amplified an mRNA sequence from a kidney cell line established from a SJL/J (H2 s) mouse that suffered from autoimmune nephritis; subsequently, it has been recognized as being an Aβ5 s5 transcript [49]. Their work suggests that the Aβ5 s5 gene is present in SJL/J mice and can be involved in autoimmune nephritis; on the other hand, neither S-mutants in B6, nor the SR/CR mutant in BALB/c strain (see below) are prone to autoimmune disease.

Cui et al. [48] have found a dominant mutation in BALB/c (Charles River) strain designated SR/CR that enables its carriers to resist the highly aggressive transplantable S180 sarcoma that does not express MHC, as well as some other tumors. Loss or downregulation of MHC-I expression in tumor cells is a well-known mechanism of tumor escape from the immune surveillance [36, 60–63]. A tumor cell that does not express MHC-I fails to present its internally derived peptides to TCR and therefore cannot be detected by CD8+ CTLs. Now, the incredible SR/CR mutation supplies a proof that tumor escape through this mechanism can be prevented by the immune system. The tumor-resistant phenotype of the SR/CR mutant is age-dependant. Younger mice were ‘completely resistant’ (CR) to ascites induction with sarcoma cells. The leukocytes in peritoneal washes from young (CR) mice were mainly those of the innate immune system, including neutrophils, MΦ, and natural killer cells; apparently, T cells were not involved in CR resistance. Older mice were of two groups, some CR while some other mice do develop ascites for the first 2 weeks but then the malignant ascites undergoes a rapid spontaneous regression (SR). Older SR/CR mice that show SR rather than the CR phenotype became immune to repeated injections of S180 cells [48, 64]. Thus, both the dm1 and the SR/CR mutations were responsible for spontaneous regression of established tumors, the former one of a viral tumor [46, 47] and the latter one of a transplantable tumor in old mice [48], raising a cascade of questions about mechanisms of resistance to the tumor in them and the nature of the SR/CR mutation, which await to be answered.

The role of MHC molecules in self/nonself-discrimination

Published data on mouse mutants can be summarized as follows: MHC-I mutation H2 dm1 found using skin grafting technique [51] affected the host immune response to a virally induced tumor [46, 47]; conversely, a number of S-mutations for resistance or susceptibility to a transplantable tumor or its metastases were found to be nontrivial MHC class II β gene mutations that, contrary to expectation, did not affect skin grafting [44]. These data strongly suggest a crucial role of MHC molecules, classical or nontrivial, in antitumor immunity that is unrelated to the transplant immunity. It is therefore necessary to summarize what is known about the biological function(s) controlled by MHC genes before we discuss immune responses to the tumor in each relevant mutant. MHC was discovered by Peter Gorer in the first half of the last century and, since that time, a vast literature on this topic has accumulated. Reviewing this literature is, of course, outside the scope of this paper; rather, the following section is intended as a short overview of the problem of specificity of MHC-peptide binding and its significance to T cell responses, especially responses to the tumor, with some key references only.

MHC is a family of genes [65, 66] for antigen-binding molecules in humans and animals; the human MHC is known as HLA and the mouse MHC, as H2. True to their name, most MHC molecules are strong histocompatibility Ags: foreign tissue and organ transplants that differ from the host by any of these antigens are promptly rejected [67, 68]. Classical MHC heavy chain genes are linked together on a single chromosome in each species studied and tend to be inherited together, comprising what is known as a haplotype. MHC genes encode two categories of Ag-binding molecules, MHC-I and MHC-II, expressed at the cell surface of APC. They, in association with CD8 (MHC-I) or CD4 (MHC-II), present processed Ags (as short peptides) to the T cell receptor (TCR) [69]. The binding association between a certain MHC-I or MHC-II molecule and its peptide is a genetically controlled characteristic, and each MHC molecule has its own allele-specific motif of bound peptides, consisting of thousands of different peptides [70, 71]. Peptide motifs of different MHC alleles may overlap, while they differ. Some of the peptides capable to bind to MHC molecules in a given host may fail to do so in a genetically different host who lacks the required MHC allele [50, 72–75]. Therefore, repertoires of T cell responses to foreign Ags are limited by the assortment of MHC alleles in each individual; there is a certain gap or hole in each individual’s repertoire. On the other hand, in outbred populations in most animals and humans MHC genes are extremely polymorphic [68, 76]. Due to this polymorphism, the repertoire of peptides that can be presented in each species by the full variety of its MHC haplotypes is maximized, providing for resistance to pathogens (and malignant tumors?) in at least some individuals in the population [73], but making organ transplantation between unrelated individuals a difficult task, as already said. In short, MHC molecules are essential for recognition of host (self), tumor (neo-epitopes), and pathogen-derived (nonself, or foreign) Ags by the cellular immune system and for initiation, regulation and maintenance of immune responses.

The MHC-I pathway of exogenous Ag presentation [77] activates CD8+ T cells. MHC-I molecules are ubiquitous in that they are expressed on almost every cell and tissue in the body. Different cells may present different sets of peptides by the same MHC-I molecule while tumor cells may present tumor-specific peptides [78–80]. MHC-I molecules are composed of a heavy chain encoded in the MHC region and a light chain, β2-microglobulin, encoded by a gene not linked to that region. In each species, there are multiple and polymorphic MHC-I heavy chain genes. The heavy chain spans the membrane bilayer. In its extracellular portion, β1 and β2 domains of the heavy chain form a platform that contains an antigen-binding groove, or cleft [50]. For binding, physical and chemical properties of the peptide must be compatible with those of the cleft [73] while their properties depend on their amino acid (AA) sequence. The cleft of the MHC-I molecule limits the length of bound peptides to nine or ten AA. Some AA residues of a peptide are critical for MHC binding; those residues that are turned away from the cleft become available for TCR contact. The combination of both the exposed peptide residues and the solvent-accessible surface of the MHC cleft contribute to specific recognition by TCR. Furthermore, the affinity of the peptide–MHC interaction depends both on the peptide AA sequence and the MHC-I groove sequence. Exceeding a certain threshold of affinity is required for effective presentation to TCR; high affinity of MHC-I-peptide binding seems to correlate with enhanced antigen presentation and immunodominance in the class I-restricted CD8+ CTL response [81, 82]. Many AA residues within the groove are highly variable. A mutation or a ‘variant’ altering one or a few residues within the groove may affect the peptide repertoire of the MHC-I molecule (ligand selection) and/or its contact with TCR. Thereby, recognition of antigens by T cells is altered, resulting in MHC-I allele-specific immune responses both in mice and humans [50, 75]. Another way to look at the same problem is through the studies of evolution of pathogens. For example, AA replacements in CTL epitopes may allow a virus, HIV or SIV, to produce variants that escape detection by CTL because these escape mutants have a lower MHC-I binding affinity [83], thus supporting the evidence for a specific gap in individual’s T cell repertoire rooted in antigen presentation by MHC.

The MHC-II molecules are normally expressed mostly in professional APCs, such as MΦs, dendritic cells, activated B cells, and reticular cells, while inflammatory cytokines, i.e., interferon-γ, can induce their expression in other cell types. The MHC class II pathway processes Ag endogenously; the most obvious function of MHC-II molecules expressed by APCs is to present short antigenic peptides to CD4+ T cells [84]. Those CD4+ T cells that express TCRs capable to recognize autoantigens in the context of MHC-II molecules are eliminated in the thymus and the remaining cells migrate to the periphery. Therefore, MHC-II molecules are critical for thymic selection of the CD4+ T cell repertoire peculiar to each individual, that is for self/nonself-discrimination, and for peripheral activation of Ag-specific cells, as was first suggested by Jerne [85]. CD4+ helper T cells are believed to play a significant role in the induction and maintenance of CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor (and other) responses [86]. MHC-II molecules are cell surface αβ heavy chain heterodimers. The α and the β chains are encoded by different genes that are closely linked to MHC-I heavy chain genes in the MHC region. The Ag-binding groove of MHC-II molecules is composed of α1 and β1 heavy chain domains [87–89]. MHC-II groove is open at both ends allowing for accommodation of peptides of variable lengths, usually containing 12-24 AA residues [90]. Again, many AA residues within the groove are highly variable. The groove features three to five allele-specific pockets distributed along its length that determine MHC-II anchor residue positions of peptides (ligands) and appear to be more degenerate in specificity than in MHC-I. Degenerate to what extent? One estimate has shown that approximately 15–35% of tested synthetic peptides are bound by any single HLA-DR (human MHC-II) allele. Among peptides which were positive binders, about 50% were specific in the sense that they were bound by one out of four DR alleles tested, and only 25% of the peptides showed degenerate binding by all four tested alleles [91]. Positive correlation between the affinity of peptide–MHC-II binding and in vivo immunogenicity in generation of CD4+ T cell responses has been also observed [92]. In humans, some MHC-II alleles have been implicated in predisposition to autoimmune diseases, such as type I autoimmune diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and other; the presentation of a specific peptide population plays a major role in disease predisposition [93, 94]. In the mouse model, the H2-Aβbm12 mutation of a C57BL/6 mouse altered β chain AA residues 67, 70, and 71, all within the antigen-binding groove of the MHC-II molecule, while it did not change any other known gene in that mouse. This mutation completely abolished T cell responses to the envelope glycoprotein of the Friend leukemia helper virus [95]; it also almost completely abolished the CTL response to the male-specific HY Ag [96]. In female mice, immune responses to class I- and class II-restricted HY epitopes of MB49, a tumor that naturally expresses HY, have been demonstrated, as well as tumor escape from these responses [97]. So, despite promiscuity of peptide binding, certain degree of specificity of antigenic peptide–MHC-II binding is evident that may result either in an immune response or in a lack of a response to a foreign Ag.

A recent study suggests that some HLA haplotypes could be predisposing to metastatic melanoma in a human population and that distinct KIR/HLA ligand combinations (KIRs, killer immunoglobulin-like receptors of NK cells) may be relevant to the development of malignancy [98], although contradictory results have been reported in some earlier studies cited in that paper. In contrast with melanocytes, melanomas express HLA-DR constitutively; this may result in tumor Ag presentation and the induction of tumor Ag-specific CD4+ lymphocyte anergy. Through these mechanisms, the MHC-II molecules may participate in melanoma progression and immune escape [99]. In contrast, high levels of MHC class II expression in gastrointestinal cancers are often associated with a better prognosis, showing the involvement of CD4+ lymphocytes in protective immune responses against the tumor [100]. The reason for such controversies has not been determined.

The resistance or extraordinary susceptibility to the tumor (REST) congenics: a tool to dissect tumor-specific immune responses

From what we have already discussed, it is reasonable to suggest that host genes determine the nature of immune responses to TAAs. The effect(s) of host genes on immune responses to TAAs must be characterized if we want to learn why some immune responses are protective and other responses, nonprotective, allowing the tumor to evade them. Since tumor bearers vary in their genomes and TAAs expressed by their tumors differ, many genes may participate, and there is little hope to understand the host response to the tumor by looking at the potpourri of genes involved. The genetic requirement for solving this problem is the isolation of individual genes from that potpourri. The method devised for this purpose was the production of congenic lines. Congenic mouse lines, or simply congenics, were introduced into the field of immunology by George Snell in 1950s and used to analyze histocompatibility [101]. His method turned out to be reliable in various applications, in modern research [102]. Originally, Snell called his lines ‘isogenic resistant strains’ because they resisted or rejected transplantable tumors as well as normal tissues, including skin grafts, of the inbred partner origin, and of each other, but shared their genetic background. More specifically, he defined a congenic (‘isogenic resistant’) line as being genetically identical or almost identical with an inbred partner strain except for the presence of the foreign histocompatibility gene within a short chromosome segment containing that gene. He concluded that each congenic line carried a unique histocompatibility Ag encoded by the gene isolated in this line and assigned different numbers to each Ag defined by this technique. Histocompatibility Ags that he discovered were later confirmed by other methods, immunological and molecular. Several methods of production of congenics have been developed but discussing them is beyond the scope of this review, except one; a detailed description of other production techniques can be found elsewhere [67]. The single relevant method is opportunistic: look for a host gene mutation for resistance to a malignant tumor. Mutants actually found have already been discussed. Individual gene mutations are extremely rare events and, for this reason, it is highly unlikely that more than one gene or a chromosomal region has been affected by a mutation event in a mouse. A point mutation is always confined to one gene only, while a small deletion may result in the absence of a few tightly linked genes. As a consequence, whenever a mutation of a gene, for example, the H2 dm1 mutation, occurred in a mouse, this mouse and its progeny from matings to normal mice of the same strain (in this example, B10.D2, H2 d) remain perfectly congenic with the strain of origin [51, 67]. For this reason, all mutants listed in Table 1 are congenic lines that differ from the corresponding standard mice only at the site of a mutation for resistance or extraordinary susceptibility to the tumor for convenience, it is proposed to call them the REST congenics.

S-mutants are REST congenics on the inbred strain B6 genetic background that differ from the standard B6 mice only by their Aβ4-6 genes (we do not have an Aβ7 congenic), each of them possessing a distinctive combination of alleles of these genes. Furthermore, published data included in Table 1 and Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 demonstrated that each S-mutant responded in a unique way to each tumor tested. Hereafter each mutant/REST-congenic will be designated by both its number and its Aβ4-6 genes, such as S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 and S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b, to supply the information on the gene that defines the range of responses available to the mouse. Standard C57BL/6J mice of the genotype Aβ4 b 5 s5/Aβ4 b 5 s5 will be designated B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5. MHC molecules are supposed to be strong histocompatibility antigens. As an exception to the rule, the cell-surface molecules encoded by the nontrivial MHC-II Aβ4-6 genes are not histocompatibility antigens in the sense that skin grafts exchanged between B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 mice and S-mutants were not rejected; even on S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 mice that rejected the tumor of B6 origin, B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 skin grafts remained unaffected [44]. This was interpreted to mean that histocompatibility antigens expressed by the tumor of B6 origin are not recognized as foreign by Aβ4-6 congenics and are not the targets of the host antitumor responses—only TAAs are targeted in these mice, as briefly mentioned before. The fact that Aβ4-6 REST congenics respond differently to the same tumor is a proof that this response is under control of Aβ4-6 genes.

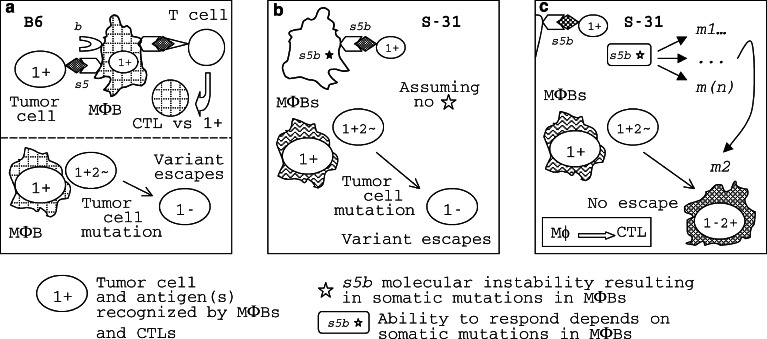

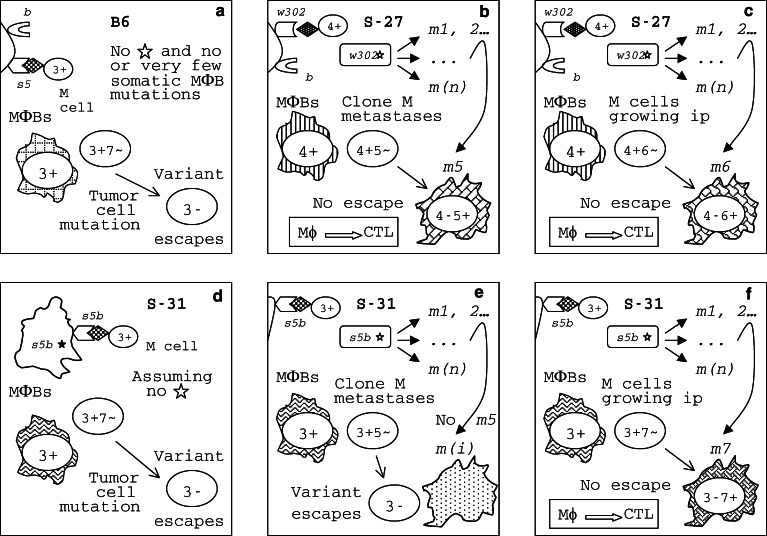

Fig. 2.

A hypothetical mechanism forestalling tumor escape from the host immune response (the ‘shooting session ‘ model). Panel a. MΦBs are principal APCs in responses to micrometastases. B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 MΦBs recognize B16LM tumor cells as foreign because they express MHC-II molecules containing the βs5 chain that bind a 1+ antigenic peptide while the MHC-II(βb) molecules do not bind it. MHC-II(βs5) MΦBs present the 1+ Ag to the immune system and initiate a CTL response against 1+ tumor cells that kills them. However, a metastatic cell may escape this attack through a gene mutation resulting in nonexpression (or low expression) of Ag 1 on its cell surface, a 1− variant [35]. Since tumor escape variants emerge with a certain probability, a B6 mouse may survive without metastases if the B16LM 1− variant did not emerge in it, explaining some 54% survival rate in these mice (see Figure 1). If the 1− variant did emerge, these cells will survive, begin to grow in the face of the immune response and kill the B6 host. Panel b. Since the Ag recognition region of the s5b allele does not differ from that of the s5 allele, S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b mice are also expected to succumb to the 1− variant. Panel c. Unlike the Aβ 5 s5 gene of B6 that is stable, the Aβ [5· 4] s5b* gene of S-31 mice is unstable [49, 106]; its instability results in frequent mutations, such as m1, m2, ... m(n), the heterogeneity and mosaicism in the MΦB population. While most of these mutations will be wasted, one or a few of them, i.e., m2, will enable the MΦB carrying it to recognize another Ag on the cell surface of B16LM metastatic cells, 2+. For this reason, the 1− metastatic cell will be seen as 1− 2+ by the S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b * host in which the MΦB-m2 [or MΦB–MHC-II(βs5bm2)] APCs appeared, the anti-2+ CTL response will be initiated, all tumor cells will be killed, and this mouse will survive

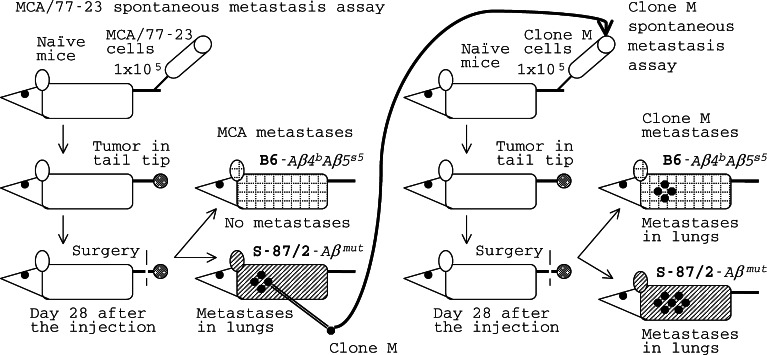

Fig. 3.

A tumor may progress to metastasis only in a genetically susceptible host (S-87/2-Aβmutant) while an established metastatic clone is capable of escaping the host (B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5) immune response even if the original tumor were incapable to do so. The MCA/77-23 (MCA) rhabdomyosarcoma and its clone M spontaneous metastasis assay. The original MCA tumor was not metastatic in B6 mice; a metastatic clone M was derived from it by in vivo selection in highly susceptible S-87/2 mice; the number of dots on a mouse symbol is roughly proportional to the average number of lung metastatic nodules appearing in mice of this strain, based on [45]

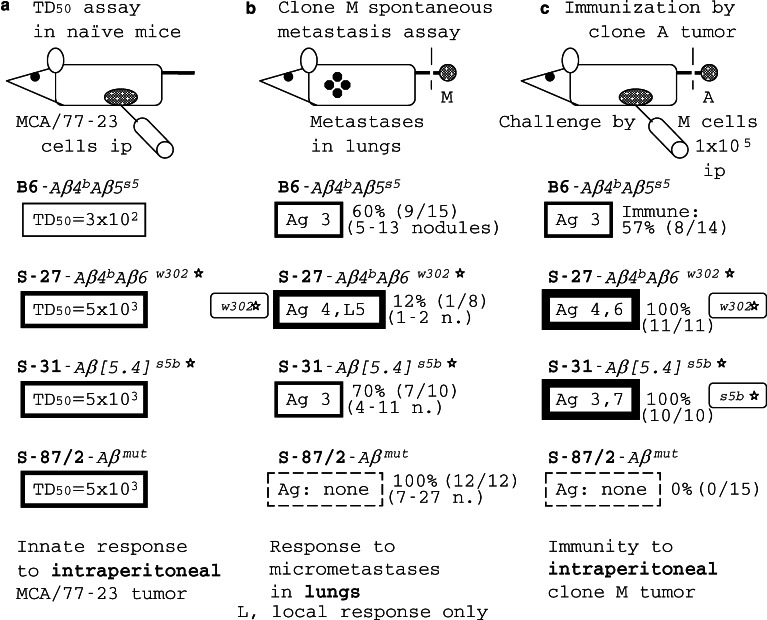

Fig. 4.

The assay bias in responses of REST congenics to MCA/77-23 (MCA) rhabdomyosarcoma. The resistance to the tumor is attributable both to MΦBs and CTLs primed by MΦBs and capable to destroy tumor cells. a In a TD50 assay, a tumor cell dose resulting in tumor growth in 50% of injected naïve mice (50% take) is determined. b In a spontaneous metastasis assay (see Fig. 3), the ability of mice to protect themselves against clone M metastases was determined; metastases occur in lungs. c In the immunity assay, the ability of mice to get immunized against the tumor and to protect themselves against a later ip challenge by clone M cells is determined, based on [45]

Fig. 5.

The MCA sarcoma escape and the REST congenics response/survival patterns are compatible with the “shooting session” model. a B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 MΦBs recognize clone M cells as foreign because they express MHC-II molecules containing the βs5 chain which bind a 3+ antigenic peptide while the MHC-II(βb) molecules do not bind it. Variant 3− escapes the B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 immune response. b S-27-Aβ 4 b 6 w302* MΦBs recognize clone M cells as foreign because they express MHC-II(βw302) molecules which bind a 4+ antigenic peptide; MΦBs initiate an immune response against the tumor. Due to tumor mutation and the immune selection, a 4− tumor cell clone may emerge; due to the w302* molecular instability, a mutant MΦB clone may emerge, m5, capable to recognize another Ag on the cell surface of M metastatic cells in lungs, 5+, and to initiate a protective response against the 4− 5+ clone. Tumor escape is prevented with a high probability. c Similarly, due to the w302* molecular instability, a mutant MΦB clone may emerge, m6, capable to recognize another Ag on the cell surface of M cells growing ip, 6+, and to initiate a protective response against the emerging 4− 6+ clone. Tumor escape is fully prevented in preimmunized mice. d Since the Ag recognition region of the s5b allele of S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b mice does not differ from that of the s5 allele of B6 mice, S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b mice are also expected to succumb to the 3− variant. e Although the Aβ [5· 4] s5b* gene of S-31 mice is unstable, mutations capable to recognize Ag 5 on clone M metastatic cells in lungs cannot be derived from its DNA sequence; for this reason, S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice survive clone M metastases at about the same rate as B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice. f However, the unstable Aβ [5·4] s5b* gene of S-31 mice is fully capable to produce a mutation, m7, enabling their MΦBs to recognize another Ag on the cell surface of M cells growing ip, 7+, and to initiate a protective response against the emerging 4− 7+ clone (or, perhaps, they recognize Ag 6, the same as S-27 MΦBs). Tumor escape is fully prevented in preimmunized mice. The stable s5 gene of B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice does not provide for mutant MΦBs able to recognize Ag 6 or 7 on M cells

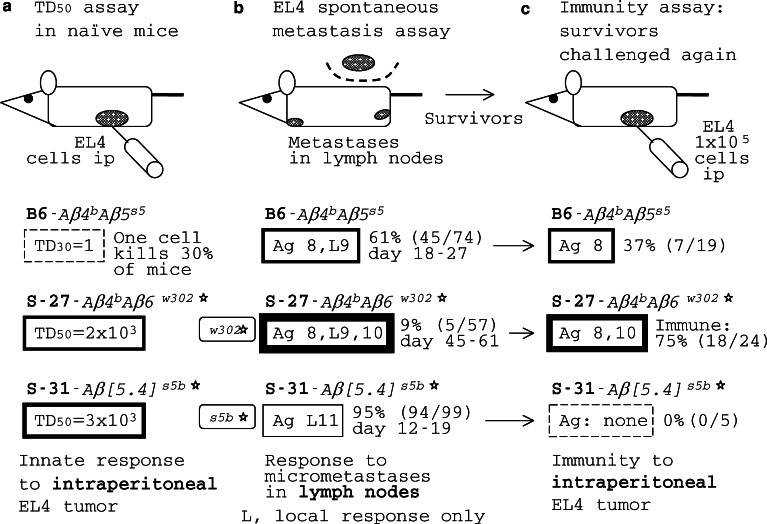

Fig. 6.

The assay bias in responses of REST congenics to EL4 lymphoma. The resistance to the tumor is attributable to both MΦBs and CTLs primed by MΦBs and capable to destroy tumor cells. a TD50 assay in naïve mice. bSpontaneous metastasis assay (see Fig. 1); metastases in lymph nodes. c The immunity assay. In this case, the ability of mice that survived in the EL4 spontaneous metastasis assay to protect themselves against a later ip challenge by the same tumor was determined, based on [44, 45]

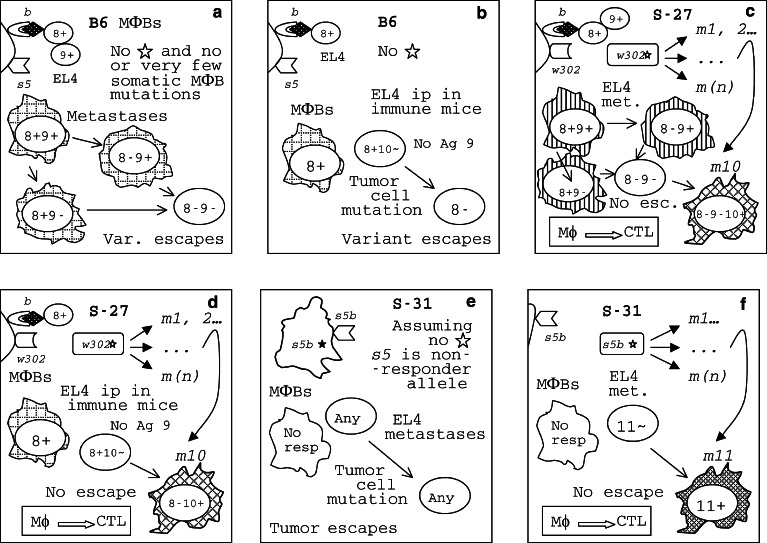

Fig. 7.

The EL4 lymphoma escape and the REST congenics response/survival patterns are compatible with the “shooting session” model. a B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 MΦBs recognize EL4 cells as foreign because they express MHC-II molecules containing the βb chain that bind a 8+ or a 9+ antigenic peptide while the MHC-II(βs5) molecules do not bind it. Metastatic variant 8− 9− escapes the B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 immune response. b EL4 cells growing ip do not express Ag 9 found on metastatic cells in lymph nodes. The 8− variant escapes the response accounting for inability of 63% of immunized B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice that survived in the EL4 spontaneous metastasis assay to protect themselves against the ip challenge by the tumor. c In a S-27-Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mouse, a mutant MΦB clone, m10, may emerge due to the w302* molecular instability. MΦBs that express MHC-II(βw302m10) mutant molecules will be able to bind a 10+ antigenic peptide from tumor cells; these MΦBs initiate a protective response against the 8− 9− 10+ clone; tumor escape is prevented with a high probability and the frequency of metastases is low in these mice. d Similarly, immune S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice are better protected against the ip challenge by the EL4 tumor because of the frequent m10 mutation in their MΦBs that is absent in B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice. e All S-31-Aβ [5·4] s5b mice are expected to succumb to EL4 metastases because they carry a nonresponder allele, s5b. Panel f. However, the unstable Aβ [5· 4] s5b* gene of S-31 mice is capable to produce a mutation, m11, enabling their MΦBs to recognize another Ag on the cell surface of EL4 metastatic cells, 11+, and to initiate a protective response against the tumor. Tumor variant 11− may escape; still, metastases are prevented in S-31-Aβ [5·4] s5b mice in which this variant did not appear by virtue of chance

Responses to the original tumor and to minimal residual disease in REST congenics

Tumor growth was undetectable in unprimed S-mutants injected with a moderate dose of tumor cells of parental strain origin and in young SR/CR mice injected with a high tumor cell dose (Table 1), indicating that their immune system quickly kills the injected cells (a dose-dependent effect). As already said, MΦBs, a subpopulation of MΦs, is the key player in the early protective antitumor response in S-mutant mice [49], and MΦs play a role in the early response of SR/CR mice to the tumor, along with other cells of the innate immune system [48, 64]. So, both groups have found that mutant MΦs are involved in early responses. Furthermore, Cui et al. [48] demonstrated, using nude (foxn1 −/foxn1 −) congenics, that T cells were not involved in early resistance to the S180 tumor in mice of the CR phenotype (older mice that show SR rather than the CR phenotype were not tested). S-mutants were equal to B6-Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice in their ability to kill standard NK targets, YAC-1 and L1210 [44], showing that NK cells are unlikely to be involved in resistance to the tumor in these mice. In mixed cultures in vitro, B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 lymphocytes responded to EL4 tumor cells much stronger than S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 or S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b lymphocytes, demonstrating that these responses were irrelevant to the early protective response against the tumor.

Minimal residual disease [103–105] is a major problem in clinical treatment of cancers; this problem was addressed using S-mutants, which are a subgroup of REST congenics. The immune system of some of these mice effectively prevented the outgrowth of micrometastases from a number of tumors, after the surgical removal of the primary tumor. Most S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 mice that survived in spontaneous metastasis tests of EL4 lymphoma became immunized against subsequent injections of the same tumor; all S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 and S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b mice that survived in spontaneous metastasis tests of the MCA rhabdomyosarcoma became immunized against the tumor [45]. It therefore appears that CTL effectors were involved in protection against the tumor in survivors, although these effectors and the signaling involved remain to be characterized. Dormant tumor cells are another constituent of minimal residual disease [105]. Some very late protective responses against dormant tumor cells have been observed in S-mutants. In some S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 survivors, dormant EL4 tumor cells were present that could be induced to grow and to kill the mouse by a mild stress, such as mating to a stranger mouse of the opposite sex. Dormant tumor cells persisted until day 59 after the injection. After day 59, no dormant tumor cells were detectable in these mice; apparently, they were cleared by the host immune system [ref. 45 and our unpublished results]. These late responses against dormant tumor cells were attributable to tumor-specific effectors, most probably, CTLs.

Antigen-specific responses to micrometastases are under the control of Aβ4-6 genes

Tests of REST congenics in a spontaneous metastasis assay of B16LM melanoma and EL4 lymphoma revealed different patterns of response to these tumors (Fig. 1): standard B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 mice were moderately resistant/susceptible to both these tumors, S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 mice resisted both B16LM and EL4 metastases, and S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b mice strongly resisted B16LM metastases while being highly susceptible to EL4 metastases. These congenics gave yet another pattern of responses against MCA/77-23 (MCA) rhabdomyosarcoma that will be discussed later. Since congenic lines used in these tests were all on the B6 genetic background and differed only at their Aβ4-6 genes, the conclusion was that responses to micrometastases were tumor-specific and that the specificity of the response was under the control of Aβ4-6 genes [49, 106]. Apparently, the protective response of S-31 mice against B16LM metastases was due to the presence in them of the Aβ[5· 4] s5b gene, and the protective response of S-27 mice against B16LM and EL4 metastases was due to the presence in them of the Aβ6 w302 gene, while B6 mice that do not carry these genes were poorly protected.

A simple model explaining host response/nonresponsiveness and the initiation of protective response against micrometastases that forestalls tumor escape

An unresolved question is what factor(s) determines whether an efficient immune response against the minimal residual disease will occur wiping out all tumor cells in a survivor, or the response will be suppressed, the tumor will escape and will grow uncontrollably, in a morbid individual [29–32]. Yet, another problem may complicate the issue. The tumor is a moving target that, through its gene mutations, constantly produces resistant variants capable to escape the immune response against the original tumor [34–37]. The escape variant that lost or downregulated the target TAA(s) will grow in the face of the strong immune response to the original tumor; in the latter case, whether or not the response to the original tumor was suppressed becomes of little importance. What is the crucial difference between a survivor and a morbid mouse? An obvious point to start with is to ask whether or not the antigenic specificity of the response(s) to the tumor differs in survivors and morbid mice belonging to different REST congenic lines. If yes, then the next question is what host gene(s) controls these responses, enabling the immune system of a survivor to respond to a TAA(s) on an emerging tumor variant—and to hinder tumor escape—while a morbid mouse was unable to do so.

The simplest explanation of the results on B16LM metastases (Fig. 1) is that the mice of all three congenic lines recognized the same antigen on B16LM cells, tentatively denoted Ag 1 for the purpose of this analysis, while S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302 and S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b mice also recognized another antigen, tentatively denoted Ag 2, which B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 mice were unable to see. Then, the response of S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302 and S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b mice to two TAAs on tumor cells was stronger than the response of B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 mice because of the additional target recognized by S-27 and S-31 immune cells. Failure of most of S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b mice to respond to EL4 metastases confirms that their response to B16LM was Ag-specific. But why their immune system was able to see TAAs that B6 mice did not see? Let us begin from the opposite end—why a tumor variant goes unseen by the mouse immune system? Due to a gene mutation in a tumor cell, a B16LM tumor cell variant 1− that do not express Ag 1 may appear in a micrometastatic lung nodule of any mouse of Fig. 1. This variant escapes the immune response of B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 mice (Fig. 2, panel a) because their MΦBs do not recognize its cells as foreign: it lacks the only TAA, Ag 1+ that they were able to detect. If genes controlling responses to TAAs were also stable in S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b mice, they would also succumb to the 1− variant (panel b) because the Ag recognition region encoded in the s5b allele is the same as in the s5 allele. However, S-31 mice carry an unstable gene, Aβ[5·4] s5b* (a star will be used to distinguish unstable genes). A highly increased mutation rate of this gene results in somatic mosaicism in the MΦB population in these mice [49], affecting antigen recognition by their MΦBs, which are APCs. One (or a few) Aβ gene mutation, such as m2, may encode an antigen recognition molecule capable to bind another TAA, that is Ag 2, on tumor cells. MΦB clone m2 will be able to recognize the tumor 1− variant as foreign because it is seen as 1− 2+ by this clone (Fig. 2, panel c). In the majority of S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b* mice, these MΦBs were able to initiate a protective response against the metastatic tumor B16LM (Fig. 1). Similarly, S-27–Aβ4 b 6 w302* mice carry an unstable Aβ6 w302* gene and responded to the tumor better than the B6 mice did. MΦBs are APCs. One can say that the probability of emerging of clone m2 within the APC population (large) of a S-31 or a S-27 mouse is considerably higher than the probability of emerging of the clone 1− 2+ within the tumor cell population in micrometastatic nodules (containing small number of cells) in lungs. But the majority of mutant APC clones will not be able to recognize any target on tumor cells and will be simply wasted. Since mutations are random, their effect on the cell or the whole organism can be either deleterious or neutral, and rarely beneficial. Mutations, therefore, create genetic variation at a price, called genetic death; nevertheless, it is the genetic variation that makes natural selection and evolution possible [42]. In responses to micrometastases, the Aβ4-6* molecular instability results in a increased genetic variation in the APC population that makes possible for the immune system to catch every tumor escape variant (Fig. 2, panel c). This may look paradoxical, but it is not: it is simply a game of probabilities.

Another way to interpret the protective response against micrometastases is mechanistic. The tumor starts with the 1+ clone and goes to 1− 2+ in micrometastases; the S-31 immune system contains the vs 1+ and multiple mutant clones, including vs 2+ ; and the B6 immune system contains vs 1+ only. Because of the presence of multiple mutant APC clones, S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b* mice were able to recognize a wider spectrum of TAAs (i.e., Ag 1 and 2, Fig. 1) than B6–Aβ4 b 5 s5 mice (Ag 1 only) and, correspondingly, were able to catch the B16LM escape variant. This scenario is similar to a shooting session: it is easier to hit a moving target (the tumor) using multiple pellets that spread out (the S-31 immune system) than using a single bullet (the B6 immune system).

Mouse B16 melanoma antigens recognized by autologous T cells have been defined that are counterparts of human melanomas, including tyrosinase, gp100, MART, TRP-1, and TRP-2 [107]. It remains to be determined whether the rejection antigen(s) of the B16LM tumor in S-31–Aβ[5·4] s5b* mice (tentatively denoted Ag 2, Fig. 1) is an already known antigen or a new one. Answering this question may help to develop an efficient immunotherapy against minimal residual disease in melanoma patients. It should be noticed, however, that isolation and chemical characterization of a TAA detectable only in a spontaneous metastasis assay will be a challenge.

Another possible explanation of different sensitivity of REST congenics to B16LM metastases involves inhibitory CD4+ CD25+ cells that have been described both in mouse and human tumors [108–112]. Note that B6 mice carried two different copies of nontrivial β genes, Aβ4 b and Aβ5 s5. On the other hand, S-31 mice carried only one gene copy, Aβ[5· 4] s5b*, while they survived B16LM metastases at a higher rate. Despite the difference in responses, the antigen binding region of the s5b allele of S-31 did not differ from that of the s5 allele of B6 (Table 1, footnote). Perhaps, mice of both strains responded only to Ag 1 (suggesting no Ag 2 on tumor cells in Fig. 1), but the response was suppressed in B6 mice due to the presence of the Aβ 4 b gene in them while it was not suppressed in S-31 mice that do not have the Aβ 4 b gene—then this is why S-31 mice survived at a higher rate. Does the Aβ 4 b gene control the inhibitory CD4+ CD25+ cell response to the B16LM tumor? More experiments are required to determine whether or not this is true. One should note, however, that the suppression model does not explain why S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice that also carried the Aβ 4 b gene were resistant to B16LM metastases. Therefore, a better explanation is that an Aβ* molecular instability is associated with stronger responses to micrometastases, as in ‘shooting session’ model (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the results obtained on metastases of the MCA/77-23 tumor are compatible with the ‘shooting session’ model rather than with the suppression model, and the results on the EL4 tumor are also compatible with the first model. These results will be discussed in the next two sections of this paper.

Responses of REST congenics to MCA/77-23 sarcoma metastases

MCA is a methylcholanthrene-induced rhabdomyosarcoma of B6-Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice. The original MCA tumor was neither immunogenic nor metastatic in B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice. However, MCA tumor growing in the tail tip of S-87/2-Aβmutant mice gave lung metastases [45], indicating that these mutant mice were catastrophically susceptible to MCA metastases while the standard B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice were genetically resistant. A metastatic clone M was established from a single lung tumor nodule of a S-87/2-Aβmutant mouse (Fig. 3). If injected into the tail tip, this clone was able to produce lung metastases both in susceptible S-87/2-Aβmutant and in resistant B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice, although in the latter at a slower rate (Fig. 4). In S-87/2 mice, an Aβ gene mutation has been revealed by Southern hybridization with corresponding probes, but the mutant gene has not been sequenced. This experiment clearly demonstrated that this tumor may progress to metastasis only in a genetically susceptible host (that is, the S-87/2-Aβmutant). It also showed that an established metastatic clone is capable of escaping the host (B6-Aβ 4 b 5 s5) immune response even if the original tumor were incapable to do so, as other studies suggested [34–37].

Some of the REST congenics were used to analyze host responses to the MCA tumor and its metastatic clone M. A variety of assays were employed in these experiments. In a TD50 assay (Fig. 4a), a tumor cell dose resulting in tumor growth in 50% of injected mice (50% take) is determined. The TD50 of MCA in B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice was 300 cells injected ip indicating, perhaps, that about one in a hundred MCA cells were cancer stem cells [113]. Mice of congenic lines S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302*, S-31-Aβ [5· 4] s5b* and S-87/2-Aβmutant resisted the inoculation of cells of this tumor better than B6. In untreated S-87/2-Aβmutant mice, the TD50 of the MCA tumor was increased to 5,000 cells, as much as in S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* or S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice. If, in this assay, S-87/2-Aβmutant mice resisted the MCA tumor better than B6, how could they be highly susceptible to its metastasis (Figs. 3, 4b)? Other assays helped to identify their defect. Not surprisingly, S-87/2-Aβmutant mice could not be immunized against this tumor and could not be protected against the challenge by clone M cells. It should be noted that S-87/2-Aβmutant mice did not differ from B6 in their responses to B16LM tumor demonstrating that they were immunocompetent. The TD50 assay (Fig. 4a) reveals the ability of the innate immune system of mice to kill injected tumor cells; innate effectors include MΦs, neutrophils and NK cells [48, 64, 114]. In contrast, in the spontaneous metastasis assay (Figs. 3, 4b), mice get immunized by the surgically excised tumor while metastases appear later in remote sites of the body. Thus, in the latter assay, metastatic cells either survive in the face of the host immune response or get killed by it, at different micrometastatic sites. The effectors that kill metastatic cells are believed to be CTLs. Participation of different effectors in these two assays explains different results obtained in them.

In the immunity assay (Fig. 4c), an immunogenic clone A of the MCA tumor was used to immunize REST congenic mice that were later challenged by metastatic clone M cells, while in the spontaneous metastasis assay (Fig. 4b), M cells were used throughout. In the immunity assay, some 57% of B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice became immunized against the challenge by metastatic clone M cells and survived, while a similar per cent (60%) of B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice survived also in the spontaneous metastasis assay, implying a CTL response to a TAA (i.e., Ag 3 in Fig. 4) which was shared by clones A and M. Apparently, the response to this Ag protected B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice against metastasis of the original MCA tumor and the lack of thereof in S-87/2-Aβmutant mice made the tumor metastatic (Fig. 3). Both S-27-Aβ 4 b 6 w302* and S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice were fully protected against the M clone in the immunity assay, while S-27 were better protected against M metastases than S-31 (Fig. 4c and b, correspondingly). The latter experiment showed that, in this tumor model, no immune suppression occurred attributable to the presence of the Aβ 4 b gene. Other explanations of the differences in the response pattern of REST congenics against the tumor should be considered.

In a proportion of ‘resistant’ B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice, both in spontaneous metastasis assay and in immunity assay, the M tumor was able to escape the ‘anti-3’ immune response through an apparent 3+ → 3− mutation resulting in uncontrolled tumor growth (Figs. 4, 5). Therefore, genetic resistance to metastasis is relative: the host may be able to mount an efficient immune response against the original tumor, including all tumor cell clones that constitute the original tumor; however, there is a certain probability that a mutant tumor cell clone will emerge among metastatic cells that escapes the host response (Fig. 5, panel a). Since S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice were fully protected in the immunity assay they apparently responded to another antigen on tumor cells, denoted 7, as well as to Ag 3. A single mutation 3+ → 3− is quite likely to occur in a large ip tumor cell population while a 3+ 7+ → 3− 7− double mutation must be very infrequent because it involves two independent rare events, 3+ → 3− and 7+ → 7− mutations. The extreme rarity of the 3− 7− escape variant in the ip tumor cell population explains the protection observed in S-31 mice (Fig. 5, panel f). Evidently, the tumor is capable to escape the CTL response to a single but not to multiple TAAs. A remarkably similar conclusion has been reached from immunotherapy trial results in cancer patients, asserting that vaccination against multiple rather than a single TAA is a better strategy against the emergence of antigen-loss variants [115].

Let us see whether a model similar to the one shown in Fig. 2 for the B16LM tumor (the “shooting session” model) may also explain patterns of resistance to M clone metastases of MCA tumor in REST congenics (Fig. 5). Since the s5 allele in B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 and the s5b allele in S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice shared the DNA stretch encoding the antigen-recognition region of the β chain of nontrivial MHC-II molecules [49], these alleles determined the response to Ag 3 while the response to Ag 7 was peculiar to the s5b allele in S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice. However, Ag 7 was undetectable by the spontaneous metastasis assay because S-31 mice survived at the rate (70%) similar to B6 mice; apparently, metastatic cells in the lung do not express this antigen. Since S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice were also fully protected against the challenge by M clone in the immunity assay, they must have also responded to two Ags on ip tumor cells, designated as 4 and 6 (Fig. 5, panel c); since these mice do not carry the s5 allele, their response to these Ags is attributable to the presence of the Aβ 6 w302 gene in them. Now, S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice survived at a lower rate in the spontaneous metastasis assay (88%) than in the immunity assay (100%), suggesting that Ag 6 was undetectable in the former assay while they may have still responded to Ag 4 on metastatic cells in the lung (Fig. 4). On the other hand, in the spontaneous metastasis assay, S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice survived much better than both B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 and S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice that each responded to a single antigen, Ag 3, on metastatic cells. A single mutation 4+ → 4− is as likely to happen in a tumor cell as a 3+ → 3− mutation; if S-27 MΦBs were incapable to see the 4− metastatic cell as foreign, these mice would not survive any better than B6 or S-31; however, they did survive better, indicating that their response to Ag 4 was supplemented by a response to yet another TAA, Ag 5, on metastatic cells. To be able to escape the anti-5+ response, a tumor cell must mutate to 5−, an independent event that should accompany a 4+ → 4− mutation because the anti-4+ response is also there; therefore, a 4+ 5+ → 4− 5− double mutation is actually required for the tumor to escape the host response. By laws of probability, a 4+ 5+ → 4− 5− double mutation must be very infrequent among tumor cells because it involves two independent rare events, 4+ → 4− and 5+ → 5− mutations. Few tumor cells are present at any micrometastatic site; since double mutations are vary rare and few tumor cells are available at each site, the incidence of micrometastatic nodules, capable to escape through the 4+ 5+ → 4− 5− double mutation, must be very low. The host immune system contains a large number of Aβ 4 b 6 w302* MΦBs that are unstable and produce m5 MΦBs, among other types (Fig. 5, panel b). At each micrometastatic site in the lung, the probability of occurrence of the 4− 5− tumor escape variant is low while the probability of appearance of m5 MΦBs (initiating an anti-5 response) is high, while standard Aβ 4 b 6 w302* MΦBs (that give the anti-4 response) are common; therefore, metastases were rare in S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice. While both the Aβ [5·4] s5b* gene in S-31 mice and the Aβ 6 w302* gene in S-27 mice are molecularly unstable, only the latter is capable to produce mutations that result in recognition of Ag 5 on tumor cells (Fig. 5, panels b and e). This is expected because classical MHC-II alleles differ in their peptide binding ability (see the section on MHC molecules). Therefore, it seems that the proposed “shooting session” model explains also the pattern of responses to clone M metastases observed in REST congenics.

The designation of tumor antigens by numbers used above is strictly formal and does not necessarily imply that there are, indeed, two distinct chemically definable MCA tumor antigens recognized by immune cells of S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice and three recognized by S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302*, although there might be; but it helps to highlight the quantitative difference between mice of different Aβ 4-6 congenic lines in their ability to kill tumor cells.

Again, it appears that the crucial event in initiating a protective response to a metastatic tumor (in this case, clone M) is the allele-specific recognition of yet another TAA on each locally emerging tumor variant by MHC-II β-mutant APCs that are overproduced in survivors due to a nontrivial Aβ gene molecular instability. Put simply, the cellular immune system of a survivor is able to outmutate the tumor and to kill all residual tumor cells after the primary tumor was surgically removed. That includes all tumor cell variants evolved under selective pressure from the immune attack initiated by standard APCs that express classical nonmutant MHC-II Ag-presenting molecules. An alternative explanation that antigen 4 induced a stronger CTL response than antigen 3 and that the stronger response restrained clone M metastasis in S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice is unlikely to be correct because in the immunity assay, the response of S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice to M cells appeared to be as strong as that of S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice but it failed to restrain metastasis in them any better than in B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5.

Another proposal [64] is that cancer cells may be eradicated by multiple cell types of leukocytes in both innate and adaptive immune systems. Then to explain the data under consideration (Figs. 1, 3, 4, 6), one must assume that each Aβ 4-6 mutation affected a specific cell type and that none of them affected the same cell type; furthermore, one must assume that the effect of each cell type on the tumor is seen only in one particular assay used; one must disregard the lack of correlation between the TD50 assay results and resistance to metastasis. Too many assumptions had to be made, making this hypothesis [64] hardly applicable to the problem of minimal residual disease.

Responses of REST congenics to EL4 lymphoma metastases

About 30% of naïve B6-Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice were killed by a single cell of the EL4 lymphoma injected ip, indicating (a) that the host failed to respond to the tumor, and (b) that most, perhaps all, EL4 cells in the inoculum were cancer stem cells, as they were defined in recent studies [113]. In naïve S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice, the TD50 (the number of tumor cells required for 50% take) was 2,000 cells, while in S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice, it was 3,000 cells (Fig. 6a). But again the EL4 tumor TD50 score did not correlate with the results of its spontaneous metastasis assay in REST congenic lines of mice.

Some 39% of B6-Aβ 4 b 5 s5, and 91% of S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302*, but only 5% of S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice survived in the spontaneous metastasis assay (Fig. 6b). Since S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice were resistant to B16LM metastases (Fig. 1) and responded well to MCA tumor (Fig. 4), they were immunologically competent. It is known that the presence of the primary tumor usually suppresses T cell responses and that its removal restores immunocompetence [116], suggesting that the inability of S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice to respond against the EL4 metastases after surgical removal of the tumor should be explained in terms of the antigenic specificity of their response. Ags peculiar to EL4 metastatic variant cells were revealed in the spontaneous metastasis assay in each congenic line. They were tentatively designated 8 and 9 in B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5, 8, 9 and 10 in S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302*, and 11 in S-31-Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice. Obviously, the repertoire of responses of S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice to TAAs was skewed.

Mice that survived in the EL4 spontaneous metastases assay were believed to be immunized against the tumor. To test this theory, these survivors were challenged again by the same tumor in the immunity assay. In the latter assay (Fig. 6c), some 37% of B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice survived, indicating that their CTLs killed EL4 tumor cells, protecting the host both in the spontaneous metastasis and the immunity assays. On the other hand, some 63% of B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice died in the immunity assay, suggesting that they were immunized only against Ag 8, but not against Ag 9, in the spontaneous metastasis assay, and that, in them, the tumor escaped the immune response through 8+ → 8− mutation. Therefore, Ag 9 was invisible in the immunity assay. But why? In the spontaneous metastases assay, tumor cells were injected intradermally and metastases appeared in regional lymph nodes while in the immunity assay tumor cells were injected intraperitoneally, that is into a different site. The response to Ag 9 was evident at sites of EL4 micrometastases in lymph nodes (the mice were protected against metastases because of the anti-8+ 9+ response) but not in the peritoneal cavity—meaning that the response to Ag 9 was local, confined to sites of micrometastases. Because more (75%) S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* than B6–Aβ 4 b 5 s5 mice survived, their CTLs apparently responded to two Ags, 8 and 10, rather than to a single Ag, 8, in the immunity assay. A tumor variant capable to escape killing by anti-8+ 10+ CTLs is the 8− 10− cell. As already discussed, the double negative 8− 10− phenotype must be less frequent in the original tumor cell population than either 8− or 10− solo because two rare, independent events are involved in it, 8+ → 8− and 10+ → 10− mutations occurring together, in one cell. The low probability of emergence of the 8− 10− tumor cell variant explains why S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice survived more frequently. Perhaps, the tumor would not be able to escape an anti-8+ 9+ 10+ CTL response. But, again, some 25% of S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice failed to get immunized against another challenge by the EL4 tumor, suggesting that the anti-9+ response was not boosted in the spontaneous metastasis assay. These results can be explained assuming that the EL4 variant expressing Ag 9 was either absent or grossly underrepresented in the original, unselected 8+ 10+ tumor growing intradermally, while it appeared and/or expanded predominantly at sites of micrometastases (Fig. 7). Only a local response to Ag 9 on metastatic cells occurred in these mice, killing micrometastases but allowing the tumor to escape the anti-8+ 10+ CTL response in the immunity assay. While S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice failed to get immunized against any EL4 antigens, the spontaneous metastasis assay revealed yet another local target on EL4 cells, a weak Ag 11 to which only some rare (5%) S-31–Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice responded. The point is that unboosted local (CTL?) responses to TAAs peculiar to metastatic variants were protective against micrometastases from a very aggressive tumor in mice.

Furthermore, antigenic specificity of CTL responses to the EL4 tumor were under the control of nontrivial MHC-II Aβ 4-6 genes (as already mentioned, CTL effectors remain to be characterized). Since B6-Aβ 4 b 5 s5 and S-27-Aβ 4 b 6 w302 * mice share the Aβ 4 b allele, their response to Ags 8 and 9 was determined by this allele; the response to Ag 10 was due to the presence of the Aβ 6 w302 allele in S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice, and the one to Ag 11 was due to the Aβ [5· 4] s5b allele in S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice. The latter allele does not differ from the Aβ 5 s5 of B6 mice within the DNA stretch encoding the antigen-recognition region of the β chain of nontrivial MHC-II molecules [49]; a significant difference between them is that the s5b* is unstable in somatic cells while the s5 is a stable allele. Apparently, this instability allows S-31–Aβ [5· 4] s5b* mice to respond to Ag 11. Thus, the proposed “shooting session” model explains also the pattern of responses to EL4 metastases observed in REST congenics. It is unlikely that the Aβ 4 b -linked immune suppression (see the section on B16LM metastases) may explain variation of responses to the EL4 tumor in REST congenics because S-27–Aβ 4 b 6 w302* mice carried the Aβ 4 b gene but responded efficiently against EL4 metastases while S-31-Aβ [5·4] s5b* mice that did not have this gene were highly susceptible to EL4 metastases.

Does the interpretation of immune responses that has been just given, involving several “implied” tumor Ags, qualify as speculation that goes too far? No, because (a) the ‘implied’ Ags were used simply to provide a measure of the strength of response in each test by each REST congenic line, and (b) the results obtained on congenics are verifiable.

Weak local antigen-driven responses are protective against emerging tumor variants in micrometastatic nodules

In some studies of human cancer patients, identical T cell receptor transcripts were found in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in multiple melanoma metastases and in the primary tumor [117, 118]. However, in mouse models [119, 120] and in many studies in humans [21, 34, 121–123], excessive TCR variability in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) as compared to T cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients was observed that suggested a role for local responses against a tumor. The number and the proportion of local (restricted to TILs) and nonlocal (peripheral blood) T cell clones varied greatly in these studies and the reason for this variability could not be determined from the data presented. One possibility is that genetic variation between the subjects studied may have influenced the response patterns observed while it remained undetected. That is a lot of unknown. Responses to the tumor varying from zero to a strong protective immunity that were linked with the allelic variation of nontrivial MHC-II Aβ 4-6 genes have been demonstrated in experiments with REST congenics discussed in previous sections. Most significantly, a strong generalized response against a single TAA failed to protect some mice against metastasis (i.e., S-31 against clone M metastases, Fig. 4) while, in contrast, a weak local response(s) against another TAA(s) was protective in some cases. For example, local responses to Ags 9 and 11 were protective against EL4 micrometastases in lymph nodes in some mice (Fig. 6); similarly, a local response to Ag 5 was protective against clone M micrometastases (MCA tumor) in lungs of S-27 mice (Fig. 4). Thus, it was the use of mouse REST congenic lines that allowed to show that local antigen-driven responses were able to wipe micrometastases. It must be stressed that we are talking about the ability of the immune system to destroy the minimal residual disease, including dormant tumor cells and micrometastases, rather than the massive primary tumor and bulky metastases.

Resistance to outgrowth of micrometastases is linked to somatic instability and allelic mosaicism of Ag-recognition molecules in APCs

In minimal residual disease, both micrometastases and dormant tumor cells are capable to start growing in the face of the host immune response, that is to escape it; both were destroyed by the immune system in genetically resistant survivors. Therefore, tumor escape was hindered in these survivors, as discussed in sections above. Depending on the tumor used, the resistance was linked either to the Aβ 6 w302* gene in S-27 or to the Aβ [5·4] s5b* gene in S-31 mice. As already discussed, these are nontrivial genes encoding the β chain of MHC-II molecules expressed by a small subpopulation of APCs, such as MΦBs, while they are not expressed by tumor cells. The function of MHC-II molecules on APCs is to present short antigenic peptides to CD4+ T cells. A novel feature of both these genes was their molecular instability that produced de novo allelic variability detectable in somatic tissues down to individual cells of mice that carried these genes. Mutations probably occurred in progenitors of MΦBs, although the cell type in which the event takes place has not been determined. The obtained data strongly suggests that one mechanism of this instability was unequal crossing over between multiple Aβ gene copies [49]. In vitro DNA clones containing a duplicated Aβ 6 w302* gene produced, when replicated, clones containing two copies of the gene and those containing a single copy of the gene; replicating them was mutagenic, producing point mutations and short DNA sequence alterations both in regulatory and in coding regions of the Aβ 6 w302* gene. Another mechanism seemed to be reverse transcription of Aβ mRNA and subsequent Aβ cDNA insertion in a new chromosomal location resulting in a intronless gene. Later, an intron may become inserted in an intronless gene copy [124] and the intron insertion may result in gene conversion downstream in the adjacent exon of the Aβ gene [49, 56]. Gene conversion will result in some limited nucleotide sequence alterations in the Aβ gene. Similar but not identical (‘nontrivial’) Aβ gene copies may therefore be found in variable positions in different cell genomes, consistent with the results of mapping and sequencing of some of these genes in mice, already cited. Most (perhaps, all) of nontrivial Aβ 4-6 gene copies are located in hard-to-clone, unstable DNA regions [125, 126] of the genome, explaining while they were cloned only recently. Unlike the mutator phenotype of tumor cells that produces mutations randomly distributed throughout the genome of the cell [33], mechanisms of the Aβ 6* instability in MΦBs appear to be gene-specific which is restricted to the Aβ gene(s) only. Furthermore, these mechanisms are clearly different from the mechanism of somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes which depends on activation-induced cytidine deaminase [127]. It has been proposed that many, but not all, locations throughout the genome support hypermutation by the latter mechanism [128]. Mechanisms of the Aβ 6* molecular instability require further characterization.

The key event in protection against outgrowth of micrometastases in mice is recognition by APCs of a TAA on each and every emerging tumor variant