Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are highly potent initiators of the immune response, but DC effector functions are often inhibited by immunosuppressants such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). The present study was conducted to develop a treatment strategy for prostate cancer using a TGF-β-insensitive DC vaccine. Tumor lysate-pulsed DCs were rendered TGF-β insensitive by dominant-negative TGF-β type II receptor (TβRIIDN), leading to the blockade of TGF-β signals to members of the Smad family, which are the principal cytoplasmic intermediates involved in the transduction of signals from TGF-β receptors to the nucleus. Expression of TβRIIDN did not affect the phenotype of transduced DCs. Phosphorylated Smad-2 was undetectable and expression of surface co-stimulatory molecules (CD80/CD86) were upregulated in TβRIIDN DCs after antigen and TGF-β1 stimulation. Vaccination of C57BL/6 tumor-bearing mice with the TβRIIDN DC vaccine induced potent tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against TRAMP-C2 tumors, increased serum IFN-γ and IL-12 level, inhibited tumor growth and increased mouse survival. Furthermore, complete tumor regression occurred in two vaccinated mice. These results demonstrate that blocking TGF-β signals in DC enhances the efficacy of DC-based vaccines.

Keywords: Dendritic cell, Immuno-gene therapy, Prostate cancer, Receptor, TGF-β, Vaccination

Introduction

DCs are highly potent initiators of the immune response, characterized by their ability to engulf, process, and present antigens to T lymphocytes [1, 2]. In recent years, DC-based anti-tumor vaccines have emerged as promising strategies for cancer immunotherapy [3, 4]. However, the vaccine-induced immune responses achieved to date are not sufficient to induce a robust therapeutic effect in the patient [3–5]. Further improvements are required to enhance vaccine potency and optimize the potential for clinical success.

The insensitivity of established tumors to DC therapy is likely due to factors within the tumor microenvironment that prevent optimal induction of an antitumor immune response [6–8]. Examination of DCs in tumor-bearing animals and in cancer patients has revealed that the cells are functionally impaired in their ability to induce T-cell responses [9, 10]. TGF-β is a suppressive cytokine produced within the tumor microenvironment that might interfere with DC function [11–14]. Human prostate cancer cells and the surrounding stroma produce transforming growth factor-β [15–17]. It has been shown that up-regulation of the TGF-β1 receptor in prostate cancer tissues and high urinary and serum levels of TGF-β1 are associated with a poor clinical outcome, including tumor progression and metastasis [18–22]. High levels of TGF-β produced by cancer cells inhibit the ability of DCs to present antigen, stimulate tumor-sensitized T lymphocytes, and migrate to draining lymph nodes [23], as well as their ability to induce apoptosis [10].

The binding of TGF-β to type II TGF-β receptor (TβRII) results in the formation of a tetramer complex, involving dimers of the type I and II receptors. Type I TGF-β receptor (TβRI) is subsequently phosphorylated by the intracellular serine–threonine kinase domain of the type II receptor [24]. Once activated by phosphorylation, the Smad complexes migrate to the nucleus, where they regulate transcription of target genes, including cell cycle inhibitors such as p21, which mediate the anti-proliferative response [25, 26]. The type II receptor provides a suitable target for disruption of the signaling pathway by using a dominant negative mutant [27] lacking the intracellular kinase domain. Dominant negative TβRII binds type I receptors and forms inactive complexes, resulting in the inhibition of the signaling cascade [24]. Targeted disruption of the TGF-β signaling pathway has been achieved by restricting the expression of a dominant negative type II TGF-β receptor in bone marrow cells [13, 14] and CD8+T cells [28, 29].

In the present study, we engineered a tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DC vaccine and evaluated its antitumor effect in prostate tumor-bearing mice. Mouse TRAMP-C2 prostate cancer cells produce large amounts of TGF-β and were used as an experimental model [28]. Our results demonstrate that blocking the immunosuppressive TGF-β signaling pathway in DC can enhance the efficacy of DC-based vaccines.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

The mouse prostate transgenic adenocarcinoma cell line [30], TRAMP-C2 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), were maintained in complete medium (CM), consisting of RPMI-1640 (Cellgro, Herndon, VA) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.5 μg/ml fungizone, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, St Louis, MO).

Mice

Eight-week old female C57BL/6 mice from the Laboratory Animal Research Center of the Fourth Military Medical University were used in compliance with the regulations of the Animal Ethics Committee of the Fourth Military Medical University of PLA.

Construction of a TβRIIDN-GFP retroviral vector

TβRIIDN was excised from pcDNA3-TβRIIDN by BamHI/EcoRI digestion and inserted into the pMig-internal ribosomal entry sequence-green fluorescence protein (herein designated MSCV-GFP) vector by first linearizing pMig with EcoRI and ligating an EcoRI/BamHI adapter (5′-AATTGGATCCGCGGCCGCG-3′, 3′-CCTAGGCGCCGGCGCTTAA-5′) [13]. These clones were designated MSCV-TβRIIDN and were sequenced to determine correct orientation and number of inserts.

Production of infectious TβRIIDN-GFP retrovirus

Pantropic GP293 retroviral packaging cells (Clontech, San Diego, CA) were seeded at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells in T-25 collagen I-coated flasks (BIOCOAT; BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) 24 h before plasmid transfection in antibiotic-free 10% Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY). A mixture of 2 μg retroviral plasmid and 2 μg vesicular stomatitis virus envelope G protein (VSV-G) envelope plasmid was cotransfected in serum-free DMEM using LipofectAMINE-Plus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, cells were transfected for 12 h followed by the addition of an equivalent volume of 10% DMEM and incubation for an additional 12 h. Afterward, the supernatant was aspirated, the cells were rinsed gently in PBS, and 3 ml of fresh 10% DMEM was added each flask. Twenty-four hours later, virus-containing supernatant was collected and used to infect target cells.

Isolation of bone marrow-derived DCs

Erythrocyte-depleted murine bone marrow cells were obtained from the femurs and tibiae of C57BL/6 mice under aseptic conditions and cultured at 1 × 106 cells/ml in CM supplemented with 1,000 U/ml recombinant murine granulocyte-macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (rmGM-CSF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and 1,000 U/ml recombinant murine interleukin-4 (rmIL-4; PeproTech, London, England) [31]. The medium was replaced on day 2 with additional recombinant cytokines. On day 6, nonadherent DCs were harvested by gradient centrifugation and were further purified with MACS CD11c beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA).

Preparation of tumor lysate-pulsed DC

DCs were pulsed with freeze-thawed tumor lysate at a DC: tumor ratio of 1:3, as previously described [32]. Briefly, TRAMP-C2 tumor cells (1 × 107 cells in 500 μl of RPMI) were lysed by rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen and thawing in a 37°C waterbath three times. Cellular debris was spun down (500 rpm for 3 min) and the lysate supernatants were used to pulse DCs. Pulsed DCs were harvested and cultured with 1,000 U/ml rmGM-CSF and 1,000 U/ml rmIL-4.

Infection of DCs with retrovirus

Tumor lysate-pulsed DCs were infected with the retrovirus containing TβRIIDN or GFP vector. Three types of DC cells were established. The first type was nontransduced DCs, which were tumor lysate-pulsed DCs not infected with the virus. The second type was tumor lysate-pulsed DCs infected with the virus containing the GFP control vector. The third type was tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DCs (tumor lysate-pulsed DCs infected with the retrovirus containing TβRIIDN).

Flow cytometry

Immatured DCs, tumor lysate-pulsed DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DCs, which were cultured for an additional 18 h, were analyzed by flow cytometry, using a panel of Abs specific for MHC class II, CD40, CD11c, CD80, and CD86 (Immunotech, Miami, FL), as previously described [33]. Tumor lysate-pulsed DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DCs cultured with freeze-thawed tumor lysate at a concentration of 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 were evaluated at day 7 for the expression of the surface co-stimulatory molecules (CD80/CD86).

Western blot

Tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DCs were incubated for 24 h with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) to test the TGF-β signaling pathway. Proteins in the cell lysate were subjected to electrophoresis on Novex/10% acrylamide gels and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF). Blots were probed using monoclonal anti-Smad-2 antibody (2.5 μg/ml; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), anti-phospho-Smad-2 antibody (1 μg/ml; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Thymidine incorporation assay

The tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DCs were coincubated in triplicate at 5 × 104 cells/well with rmGM-CSF (1,000 U/ml) and rmIL-4 (1,000 U/ml) with or without the addition of 10 ng/ml murine TGF-β1. After a 72 h incubation, cells were pulsed with 0.037 MBq (1 μCi)/well of 3[H]thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 18 h, and the samples were harvested onto glass fiber filter paper for analysis using the TriCarb 2500 TR scintillation counter (Packard BioScience).

In vivo antitumor analyses

TRAMP-C2 cells (1 × 106 cells per mouse) were implanted subcutaneously (s.c.) into C57BL/6 mice at the right flank (day 0). Tumors developed 10 days later and were approximately 1–2 mm in diameters. At day 10, tumor-bearing mice (n = 10/group) were inoculated s.c. in the right flank close to the preestablished tumors, or in the left flank with a vaccine cell suspension composed of 1 × 106 of nontransduced DCs, tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, or PBS. The vaccination was repeated on day 15. Serum levels of IFN-γ and IL-12 were determined by enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assay (ELISA). Tumor growth and mouse survival were monitored daily post-inoculation. Diameters of the tumors were measured with a digital caliper and tumor volumes were calculated by the formula: v = a × b 2/2 mm3, where a represents the long diameter and b represents the short diameter of the tumor.

Cytotoxicity T Lymphocyte assays

Splenic cells were obtained from the tumor-bearing mice 5 days after the final vaccination and cocultured with X-ray (40 Gy)-irradiated TRAMP-C2 cells (2 × 105) in 24-well plates for 4 days. The activated T-cells were harvested and used as effector cells against 51Cr-loaded TRAMP-C2 target cells. An irrelevant cancer cell line, mouse melanoma cell line, B16-F1 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), was used as a nonspecific control. The standard 51Cr-release assay was performed as previously described [33]. Briefly, the target cells were incubated with 3.70 MBq of 51Cr-sodium chromate for 60 min at 37°C. After three washes with PBS, the cells were seeded into microtiter plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well. The effector cells were also added to the microtiter plate at various ratios. After incubation for 6 h at standard conditions, supernatants were collected and the radioactivity was measured using a gamma counter.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by unpaired student’s t-tests and Mantel-Haenszel logrank tests with commercially available software (Stat-200, BIOSOFT, Cambridge, UK). P < 0.05 was considered as a significant difference.

Results

Isolation of bone marrow-derived DCs and detection of infection efficiency by retrovirus

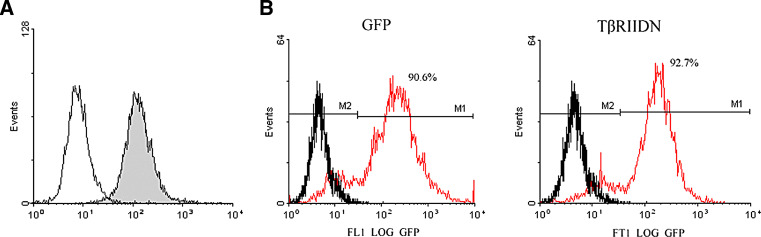

Erythrocyte-depleted murine bone marrow cells were freshly isolated from the femurs and tibiae of C57BL/6 mice. With further maintenance under the detailed culture conditions, cells were harvested by gradient centrifugation at day 6. The purity of bone marrow-derived DC, determined through analysis on CD11c staining by flow cytometry, was 90.8% (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Isolation of bone marrow¨Cderived DCs and detection of infection efficiency by retrovirus. a The purity of marrow¨Cderived DCs was 90.8% (black) as determined by flow cytometry after CD11c staining. Isotype-matched irrelevant FITC-conjugated antibodies (solid lines) were used as controls. b Flow cytometry was used to analyze tumor lysate-pulsed DCs transfected with the TβRIIDN vector (red lines) or the GFP control vector (red lines). Black lines represent untransfected tumor lysate-pulsed DCs. The transfection efficiency was 92.7 and 90.6%, respectively. Similar results were obtained from five independent experiments

Tumor lysate-pulsed DCs were infected with the TβRIIDN-containing or GFP control retrovirus. Flow cytometry was used to analyze these infected DCs. The infection efficiency was determined by flow cytometry analysis. They were 92.7 and 90.6%, respectively, for the TβRIIDN-containing and the GFP control retroviruses (Fig. 1b).

Expression of TβRIIDN did not affect the phenotype of transduced DCs

DC surface molecules MHC class II, CD40, CD11c, CD80 and CD86, were analyzed and compared among immatured DCs, tumor lysate-pulsed DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and TβRIIDN-transduced DCs by flow cytometry (Table 1). The expression of CD86, CD80, MHC class II and CD40 on tumor lysate-pulsed DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and TβRIIDN-transduced DCs was higher than those on immatured DCs (P < 0.01). But when immatured DCs were stimulated from day 7–8 with freeze-thawed tumor lysate, expression of these molecules was increased. No obvious differences were observed among tumor lysate-pulsed DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and TβRIIDN-transduced DCs (P > 0.05), indicating that the transduction of TβRIIDN did not affect the immunophenotype of DCs.

Table 1.

| DC cell | MHC class II | CD11c | CD40 | CD80 | CD86 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immatured | 31.4 | 85.8 | 19.6 | 45.1 | 38.0 |

| Tumor lysate-pulsed | 61.5 | 86.1 | 34.2 | 74.6 | 58.4 |

| GFP-transduced | 63.8 | 89.3 | 36.7 | 76.3 | 55.7 |

| TGF-β-insensitive | 65.1 | 88.6 | 35.3 | 77.2 | 57.9 |

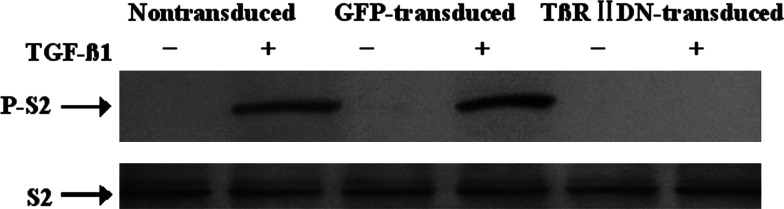

TGF-β signal transduction was blocked in TβRIIDN-transduced DC

Total Smad-2 and phosphorylated Smad-2 were detected by Western blot analysis after the TβRIIDN-transduced or GFP-transduced DCs were treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. The presence of Smad-2 was detected in all DC groups. But, phosphorylated Smad-2 was only detected in nontransduced and GFP-transduced DCs in response to TGF-β1; absence of phosphorylated Smad-2 in TβRIIDN-transduced DCs confirmed that TGF-β signal transduction was blocked by the presence of the TβRIIDN (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Detection of Smad2 and phosphorylated Smad2 by Western blot. Nontransduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, and T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs were incubated for 24 h with 5 ng/mL murine TGF-¦Â1 (+) or without TGF-¦Â1 (−). Smad2 (S2) and phosphorylated Smad2 (P-S2) were detected by Western blot using anti-Smad2 and anti-phospho Smad2 antibodies. Phosphorylated Smad2 was observed in nontransduced DCs and GFPtransduced DCs treated with TGF-¦Â1, but not in T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs

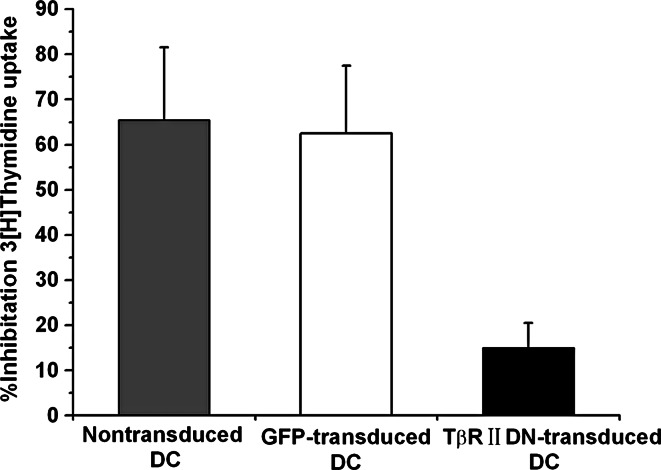

TβRIIDN-transduced DCs were resistant to the antiproliferative effects of TGF-β

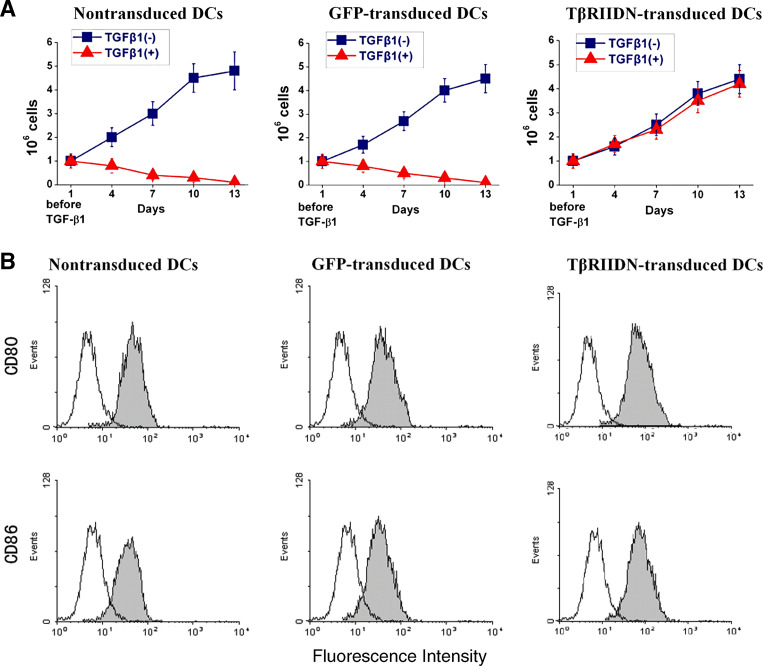

TβRIIDN lacks the intracellular kinase domain, leading to inefficiency in transducing TGF-β signals to downstream molecules in the cells. To confirm whether expression of TβRIIDN in DCs could overcome the antiproliferative effects of TGF-β1, the inhibitory rate of TGF-β on thymidine uptake was compared among the TβRIIDN-transduced DCs, GFP-transduced, and nontransduced DCs after the addition of TGF-β1 for 72 h (Fig. 3). TGF-β1 showed a dramatic antiproliferative effect on the established nontransduced and GFP-transduced DCs, inhibiting uptake by a mean of 62.5% (range, 47–80%) and 65.5% (range, 49–84%), respectively. Whereas the mean inhibitory rate of thymidine uptake by TβRIIDN-transduced DCs was 15% (range, 0–28%), the resistance to the antiproliferative effects of TβRIIDN-transduced DCs was statistically significant when compared with the nontransduced DCs (P = 0.02). Importantly, when cells were maintained under normal growth conditions in the presence of TGF-β1, the nontransduced and GFP-transduced DCs failed to proliferate and died within 15 days. TβRIIDN-transduced DCs, however, continued to proliferate and grow normally, showing significant resistance to the antiproliferative effects of TGF-β1 (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 3.

Thymidine uptake assay: Nontransduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, and T¦ÂRIIDN transduced DCs were cultured with or without murine TGF-¦Â1 (10 ng/mL) for 72 h. After 18 h of incubation with the 3[H] thymidine, the mean inhibitory rate by TGF-¦Â1 was measured in nontransduced DCs (gray), GFP-transduced DCs (white), and T¦ÂRIIDN transduced DCs (black). The graph represents a pooled analysis of the mean inhibitory rate of TGF-¦Â1 on 3[H] thymidine uptake in the ten DC lines tested

Fig. 4.

In vitro proliferation and surface co-stimulatory molecules of DCs following TGF-¦Â treatment. a Nontransduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs were incubated with TGF-¦Â1 (+) or without TGF-¦Â1 (−). Cell numbers were recorded every 3 days. In the presence of TGF-¦Â1, T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs continue to proliferate and grow normally. The figures indicate average results in each group. b After freeze¨Cthawed tumor lysate and TGF-¦Â1 treatment, nontransduced DCs, GFP transduced DCs and T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs were incubated with FITC-labeled antimouse CD80, CD86 antibodies (black) for 2 h at 37U+00AlãC, and then subjected to flow cytometry. Isotype-matched irrelevant FITC-conjugated antibodies (solid lines) were used as controls. Data show representative results from two independent experiments

Up-regulation of costimulatory molecules in TβRIIDN-transduced DC after TGF-β1 stimulation

Nontransduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and TβRIIDN-transduced DCs were cultured with freeze-thawed tumor lysate and 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 7 days. The surface co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, were analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4b). As expected, expression of CD86 and CD80 was higher on TβRIIDN-transduced DCs than on nontransduced DCs and GFP-transduced DCs (P < 0.01) in the presence of TGF-β1.

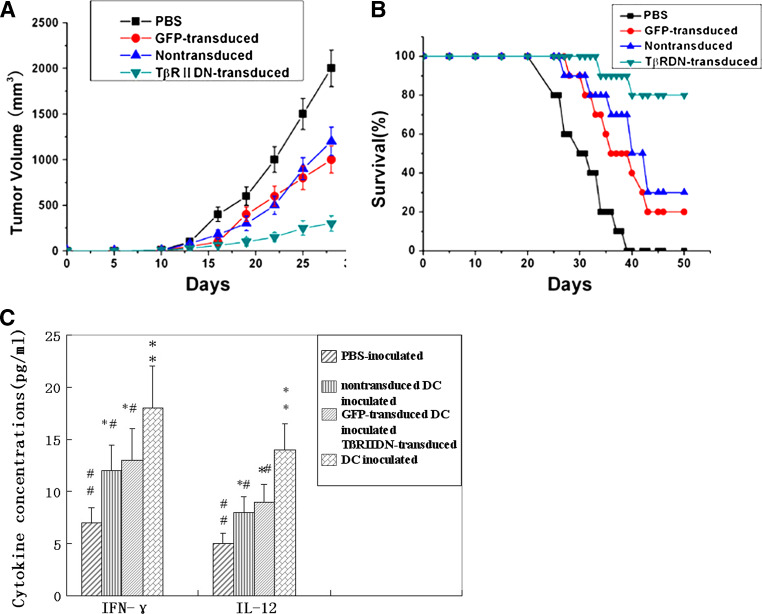

TβRIIDN-transduced DCs suppressed tumor growth and increased survival rate of tumor-bearing mice

To assess the antitumor effect of the TβRIIDN-transduced DC vaccine in vivo, TRAMP-C2 tumors were established in C57BL/6 mice. A suspension of nontransduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, or TβRIIDN-transduced DCs was injected into tumor-bearing mice (n = 10/group). PBS was used as a negative control. These experimental groups were designed to evaluate whether blocking TGF-β signaling alters the efficacy of DC vaccine in inducing anti-tumor immune responses and mortality of the tumor-bearing mice. As shown in Fig. 5a, immunization with TβRIIDN-transduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs or nontransduced DCs significantly suppressed the growth of the tumor (P < 0.01, P < 0.05 and P < 0.05, vs. control, respectively), with the TβRIIDN-transduced DCs showing the more significant inhibitory effect. Complete tumor regression occurred in 20% of TRAMP-C2-tumor-bearing mice that were treated with TβRIIDN-transduced DCs. These results indicated that the tumor lysate-pulsed TGF-β-insensitive DC vaccine had the strongest anti-tumor effect in all the vaccination groups.

Fig. 5.

In vivo anti-tumor activity of T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs. a Tumor growth in mice after different immunization strategies. C57BL/6 mice with TRAMP-C tumors were immunized with nontransduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs, or PBS, respectively. Results are presented as mean tumor volumes in each group. b Kaplan–Meier survival curves of C57BL/6 tumor-bearing mice challenged with tumor lysate-pulsed T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, or nontransduced DCs, or PBS via subcutaneous injection (n = 10/group; P < 0.01 by the log-rank test for the T¦ÂRIIDN group versus GFP or control group). c Circulating levels of IL-12 and IFN-¦Ã in experimental mice. Serum specimens were collected after 20 days following the inoculation of DC cells. IL-12 and IFN-¦Ã production in DC-treated mice was detected in triplicate by ELISA. * P < 0.05 and ** P < 0.01 between PBS-inoculated mice and other groups. # P < 0.05 and # # P < 0.01 between T¦ÂRIIDN-transduced DC inoculated mice and other groups. All experiments were repeated three times with similar results. Bars = SD

Another four groups of ten mice were used to evaluate the survival rate after 50 days. Results showed that survival rate of the untreated, GFP-vector control and nontransduced DCs treated mice was 0, 20 and 30%, respectively, while the survival of the TβRIIDN-transduced DCs treated cohort was 80% (Fig. 5b). Statistical analysis by using the Mantel-Haenszel log-rank test indicated a significant difference between the TGF-β-insensitive-DC and the other two control groups (P < 0.01). The result demonstrates that the TGF-β-insensitive DC vaccine was effective in improving the survival rate in mice bearing TGF-β-secreting tumors.

TβRIIDN-transduced DCs induced higher IFN-γ and IL-12 level in vivo

In animals injected with PBS, there was a basal level of IFN-γ and IL-12. In animals received nontransduced DCs or GFP-transduced DCs, there was a significant increase in levels of both cytokines. A further increase in serum IL-12 and IFN-γ (Fig. 5c) was observed when these cells were rendered insensitive to TGF-β (the TβRIIDN-transduced DCs group), suggesting the increase of activated immune cells in these hosts.

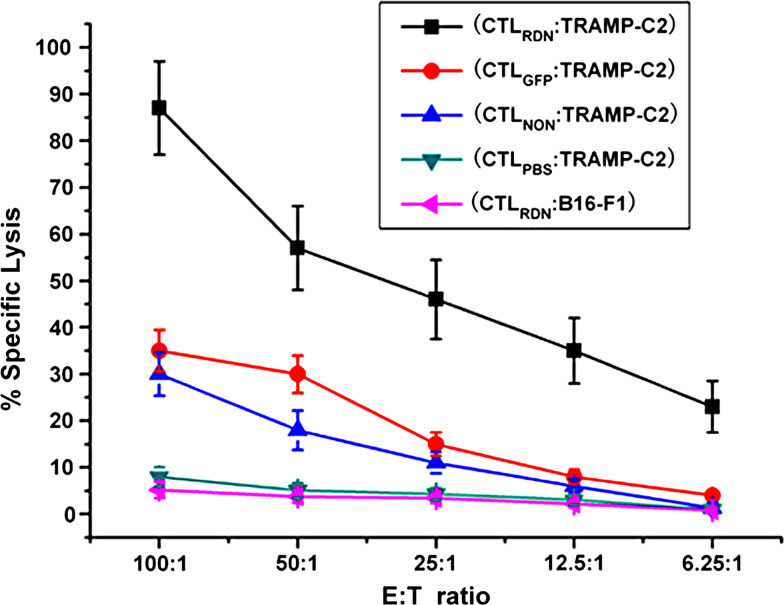

TβRIIDN-transduced DCs induced potent tumor-specific CTL response in vivo

To determine whether the antitumor response induced by TβRIIDN-transduced DCs is tumor-specific, splenic cells were collected from tumor-bearing mice 5 days after the final DC vaccination regimens. The ability of CTLs to lyse TRAMP-C2 cells was assayed in vitro using a standard 51Cr release assay. Compared with the PBS-vaccinated group, mice treated with TβRIIDN-transduced DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, or non-transduced DCs all showed a higher cytotoxicity against the TRAMP-C2 cells. The most potent TRAMP-C2-specific splenic CTL response was induced by the TGF-β-insensitive DCs in the tumor bearer (85% killing activity at an effector:target cell ratio of 100:1; Fig. 6). No apparent lysis was observed against irrelevant B16-F1 cells. This result indicates that tumor-specific cytolysis is generated by blocking TGF-β signaling, which enhances the efficacy of DC vaccines.

Fig. 6.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay: activated CTLs from C57BL/6 tumor-bearing mice 5 days after final vaccination with different DCs and mature CTLs from different treated groups of tumor lysate-pulsed T¦ÂRIIDN DCs, GFP-transduced DCs, nontransduced DCs and PBS. Groups were designated CTLRDN, CTLGFP, CTLnon and CTLPBS respectively, and were used as effector (E) cells, whereas 51Cr-labeled TRAMP-C2 or irrelevant B16-F1 cells used as target (T) cells in 6 h 51Cr-release assays. Each point represents the mean of triplicate cultures, and a representative experiment is shown

Discussion

DCs are professional antigen-presenting cells, and can trigger T cell activation required for the initiation and modulation of immune responses [12, 23, 34]. However, TGF-β can interfere with several DC functions, including downregulation of MHC antigens or molecules on the cell surface, as well as the induction of DC apoptosis in the sentinel lymph nodes [10, 35, 36]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that TGF-β inhibits the antigen-presenting functions and antitumor effect of the DC vaccines [12, 23].

As is a potent immunosuppressive cytokine, TGF-β has been considered as an attractive target for anti-cancer therapy. Systemic administration of an anti-TGF-β antibody and IL-2 shows a significant decrease in number and size of metastatic B16 tumor lesions [37], suggesting that TGF-β immunosuppression can be partially overcome by TGF-β signal blockade. However, the delivery of a soluble therapeutic agent may be insufficient to block high concentrations of TGF-β present in tumor microenvironments.

Dominant-negative mutant is an effective method to block signaling pathway of membrane receptor. As for TGF-β signaling pathway, a dominant-negative mutant of TGF-β type II receptor with a deleted cytoplasmic domain (TβRIIDN) may block its signaling pathway, thus protect cells from the inhibitory effect of TGF-β signaling. The mechanism is: in TβRIIDN-transduced cells, the lack of the intracellular domain prevents phosphorylation of TβRII and abrogates all downstream signaling events, including Smad phosphorylation. By using such a kind of mutant, Shah et al. [14] had reported that murine bone marrow cells were rendered insensitive to TGF-β by retroviral expression of the TβRIIDN construction, which resulted in an absence of Smad-2 phosphorylation. Recently, Zhang et al. [38] reported that a retroviral (MSCV)-mediated TβRIIDN expression can also change tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells to be TGF-β-insensitive [39].

In the present study, we detected the influence of TβRIIDN expression on DCs since DCs’ function can also be impacted by TGF-β. DCs used in our experiment were infected with retrovirus. An attractive advantage of retroviral vectors is that integration of the modified viral genome into the host genome allows the genetic modifications to be maintained through cell division [40]. Thus, cell types that undergo multiple independent maturation steps, maintain expression of the genes engineered into the retrovirus construct. By using a novel retroviral construct, TβRIIDN-GFP retroviral vector, which was developed by Shah et al. [13], we obtained stably and durably transduced DC cells.

In TβRIIDN-transduced DCs, phosphorylated Smad-2 was undetectable in response to TGF-β, indicating the blockage of TGF-β signaling pathway. While in nontransduced and GFP-transduced DCs, TGF-β signaling pathway still existed as indicated by the detection of phosphorylated Smad-2. The blockade of TGF-β signaling pathway also helped the TβRIIDN-transduced DCs to be resistant to the antiproliferative effect of TGF-β (Fig. 4a).

Among the TβRIIDN DCs, GFP-transduced DCs and nontransduced DCs, there is no difference in the immunophenotype, but their function was different after TGF-β stimulation. In TβRIIDN-transduced DCs, the expression of co-stimulatory molecules such as CD80 and CD86 were up-regulated after antigen and TGF-β1 stimulation. Since T-cell sensitization is more effective in mature DCs with enhanced co-stimulatory molecules expression [1, 41], the up-regulation of CD80, CD86 indicated enhanced antigen presentation capacity of TβRIIDN DCs.

Our data also showed that tumor-bearing mice vaccinated with the TGF-β-insensitive DCs had increased survival rates and suppressed growth of autologous tumors. More impressively, complete tumor regression occurred in two vaccinated mice. Further evaluation indicated that CTLs in mice received TGF-β-insensitive DCs had improved cytotoxicity, and increased IL-12 and γ-IFN levels were also detected in these mice. These results indicated that the enhanced anti-tumor activity was induced by the TβRIIDN-transduced DCs.

In summary, our findings indicate that expression of the TβRIIDN construction can convert DCs from tolerogenic to immunogenic, thereby inducing efficient antitumor immunity. Therefore, our results may significantly impact the development of future antitumor vaccines. As the protocols for generating DC vaccines continue to evolve, cancer vaccine strategies will need to incorporate new information to develop highly potent DC-based immunotherapies to fight cancer.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported in part by grants from the Nature Science Foundation of China (Project No. 30471738 and 30300413) and the Technology Plan Emphasis Item of Peking (Project No. D0206011000091). We are grateful to the NIH Fellows Editorial Board for their editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Fu-Li Wang, Wei-Jun Qin contributed equally to this report.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee WC, Wang HC, Hung CF, Huang PF, Lia CR, Chen MF. Vaccination of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells: a clinical trial. J Immunother. 2005;28:496–504. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000171291.72039.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang GC, Lan HC, Juang SH, Wu YC, Lee HC, Hung YM, Yang HY, Whang-Peng J, Liu KJ. A pilot clinical trial of vaccination with dendritic cells pulsed with autologous tumor cells derived from malignant pleural effusion in patients with late-stage lung carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:763–771. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kugler A, Stuhler G, Walden P, Zoller G, Zobywalski A, Brossart P, Trefzer U, Ullrich S, Muller CA, Becker V, Gross AJ, Hemmerlein B, Kanz L, Muller GA, Ringert RH. Regression of human metastatic renal cell carcinoma after vaccination with tumor cell-dendritic cell hybrids. Nat Med. 2006;6:332–336. doi: 10.1038/73193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma S, Stolina M, Yang SC, Baratelli F, Lin JF, Atianzar K, Luo J, Zhu L, Lin Y, Huang M, Dohadwala M, Batra RK, Dubinett SM. Tumor cyclooxygenase 2-dependent suppression of dendritic cell function. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:961–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shurin GV, Shurin MR, Bykovskaia S, Shogan J, Lotze MT, Barksdale EM., Jr Neuroblastoma-derived gangliosides inhibit dendritic cell generation and function. Cancer Res. 2001;61:363–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marincola FM, Jaffee EM, Hicklin DJ, Ferrone S. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:181–273. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aalamian M, Pirtskhalaishvili G, Nunez A, Esche C, Shurin GV, Huland E, Huland H, Shurin MR. Human prostate cancer regulates generation and maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Prostate. 2001;46:68–75. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(200101)46:1<68::AID-PROS1010>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito M, Minamiya Y, Kawai H, Saito S, Saito H, Nakagawa T, Imai K, Hirokawa M, Ogawa J. Tumor-derived TGFbeta-1 induces dendritic cell apoptosis in the sentinel lymph node. J Immunol. 2006;176:5637–5643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorelik L, Flavell RA. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in T cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1118–1122. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kao JY, Gong Y, Chen CM, Zheng QD, Chen JJ. Tumor-derived TGF-beta reduces the efficacy of dendritic cell/tumor fusion vaccine. J Immunol. 2003;170:3806–3811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah AH, Tabayoyong WB, Kimm SY, Kim SJ, Van Parijs L, Lee C. Reconstitution of lethally irradiated adult mice with dominant negative TGF-beta type II receptor-transduced bone marrow leads to myeloid expansion and inflammatory disease. J Immunol. 2002;169:3485–3491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah AH, Tabayoyong WB, Kundu SD, Kim SJ, Van Parijs L, Liu VC, Kwon E, Greenberg NM, Lee C. Suppression of tumor metastasis by blockade of transforming growth factor beta signaling in bone marrow cells through a retroviral-mediated gene therapy in mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7135–7138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wikstrom P, Damber J, Bergh A. Role of transforming growth factor-beta1 in prostate cancer. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;52:411–419. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20010215)52:4<411::AID-JEMT1026>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang EY, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta 1-induced changes in cell migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis in the chicken chorioallantoic membrane. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:731–741. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enk AH, Jonuleit H, Saloga J, Knop J. Dendritic cells as mediators of tumor-induced tolerance in metastatic melanoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:309–316. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971104)73:3<309::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wikstrom P, Stattin P, Franck-Lissbrant I, Damber JE, Bergh A. Transforming growth factor beta1 is associated with angiogenesis, metastasis, and poor clinical outcome in prostate cancer. Prostate. 1998;37:19–29. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(19980915)37:1<19::AID-PROS4>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shariat SF, Shalev M, Menesses-Diaz A, Kim IY, Kattan MW, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM. Preoperative plasma levels of transforming growth factor beta (1) [TGF-beta (1)] strongly predict progression in patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2856–2864. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.11.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry KT, Anthony CT, Case T, Steiner MS. Transforming growth factor beta as a clinical biomarker for prostate cancer. Urology. 1997;49:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adler HL, McCurdy MA, Kattan MW, Timme TL, Scardino PT, Thompson TC. Elevated levels of circulating interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta1 in patients with metastatic prostatic carcinoma. J Urol. 1999;161:182–187. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner MS, Zhou ZZ, Tonb DC, Barrack ER. Expression of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in prostate cancer. Endocrinology. 1994;135:2240–2247. doi: 10.1210/en.135.5.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobie JJ, Wu RS, Kurt RA, Lou S, Adelman MK, Whitesell LJ, Ramanathapuram LV, Arteaga CL, Akporiaye ET. Transforming growth factor beta inhibits the antigen-presenting functions and antitumor activity of dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1860–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porgador A, Snyder D, Gilboa E. Induction of antitumor immunity using bone marrow-generated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:2918–2926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F. Receptor-regulated Smads in TGF-beta signaling. Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1280–s1303. doi: 10.2741/1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moustakas A, Pardali K, Gaal A, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling in regulation of cell growth and differentiation. Immunol Lett. 2002;82:85–91. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2478(02)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen RH, Ebner R, Derynck R. Inactivation of the type II receptor reveals two receptor pathways for the diverse TGF-beta activities. Science. 1993;260:1335–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.8388126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Q, Yang X, Pins M, Javonovic B, Kuzel T, Kim SJ, Parijs LV, Greenberg NM, Liu V, Guo Y, Lee C. Adoptive transfer of tumor-reactive transforming growth factor-beta-insensitive CD8+ T cells: eradication of autologous mouse prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1761–1769. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q, Jang TL, Yang X, Park I, Meyer RE, Kundu S, Pins M, Javonovic B, Kuzel T, Kim SJ, Van Parijs L, Smith N, Wong L, Greenberg NM, Guo Y, Lee C. Infiltration of tumor-reactive transforming growth factor-beta insensitive CD8+ T cells into the tumor parenchyma is associated with apoptosis and rejection of tumor cells. Prostate. 2006;66:235–247. doi: 10.1002/pros.20340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster BA, Gingrich JR, Kwon ED, Madias C, Greenberg NM. Characterization of prostatic epithelial cell lines derived from transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate (TRAMP) model. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3325–3330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kao JY, Zhang M, Chen CM, Chen JJ. Superior efficacy of dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccine compared with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine in colon cancer. Immunol Lett. 2005;101:154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo SC, Kim GY, Lee CM, Moon DO, Kim HK, Lee TH, Moon YS, Park NC, Yoon MS, Lee KS, Park YM. The maturation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells by tumor lysate uptake in vitro is not essential for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:1331–1335. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.12.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Z, Moyana T, Saxena A, Warrington R, Jia Z, Xiang J. Efficient antitumor immunity derived from maturation of dendritic cells that had phagocytosed apoptotic/necrotic tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:539–548. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutella S, Lemoli RM. Regulatory T cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Immunol Lett. 2004;94:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato K, Kawasaki H, Nagayama H, Enomoto M, Morimoto C, Tadokoro K, Juji T, Takahashi TA. TGF-beta 1 reciprocally controls chemotaxis of human peripheral blood monocyte-derived dendritic cells via chemokine receptors. J Immunol. 2000;164:2285–2295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takayama T, Morelli AE, Onai N, Hirao M, Matsushima K, Tahara H, Thomson AW. Mammalian and viral IL-10 enhance C–C chemokine receptor 5 but down-regulate C–C chemokine receptor 7 expression by myeloid dendritic cells: impact on chemotactic responses and in vivo homing ability. J Immunol. 2001;166:7136–7143. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hacker C, Kirsch RD, Ju XS, Hieronymus T, Gust TC, Kuhl C, Jorgas T, Kurz SM, Rose-John S, Yokota Y, Zenke M. Transcriptional profiling identifies Id2 function in dendritic cell development. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:380–386. doi: 10.1038/ni903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strobl H, Knapp W. TGF-beta1 regulation of dendritic cells. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(99)00256-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wieser R, Attisano L, Wrana JL, Massague J. Signaling activity of transforming growth factor beta type II receptors lacking specific domains in the cytoplasmic region. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7239–7247. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Slavin AJ, Tarner IH, Nakajima A, Urbanek-Ruiz I, McBride J, Contag CH, Fathman CG. Adoptive cellular gene therapy of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S1568-9972(02)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellman I, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell. 2001;106:255–258. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]