Abstract

We previously reported peptide vaccine candidates for HLA-A3 supertype (-A3, -A11, -A31, -A33)-positive cancer patients. In the present study, we examined whether those peptides can also induce cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity restricted to HLA-A2, HLA-A24, and HLA-A26 alleles. Fourteen peptides were screened for their binding activity to HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, -A*0207, -A*2402, and -A*2601 molecules and then tested for their ability to induce CTL activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from prostate cancer patients. Among these peptides, one from the prostate acid phosphatase protein exhibited binding activity to HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, and -A*2402 molecules. In addition, PBMCs stimulated with this peptide showed that HLA-A2 or HLA-A24 restricted CTL activity. Their cytotoxicity toward cancer cells was ascribed to peptide-specific and CD8+ T cells. These results suggest that this peptide could be widely applicable as a peptide vaccine for HLA-A3 supertype-, HLA-A2-, and -A24-positive cancer patients.

Keywords: HLA, Peptide vaccine, Immunotherapy, Prostate acid phosphatase

Introduction

The field of peptide vaccines for cancer patients is currently in an active state of clinical investigation [1–6]. Peptide-based immunotherapy, however, is highly restricted by HLA-A alleles, and ongoing clinical trials are mostly limited to HLA-A2- or -A24-positive patients, primarily because of the higher worldwide frequencies of these alleles [7]. Subsequently, cancer patients with alleles other than HLA-A2 or -A24 have been out of the scope of the current peptide-based immunotherapy, and candidate peptides widely applicable to such patients are needed.

It has become clear that approximately 20% of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitope peptides could induce CTL activity restricted to more than one HLA-class IA allele [8]. We recently reported that one HLA-A24-restricted CTL epitope peptide could induce such CTL activity restricted to multiple HLA-class IA alleles [9]. In the present study, we examined whether or not the 14 different peptides that can induce HLA-A3 supertype-restricted CTL activity as reported previously [10–14] can also induce CTL activity restricted to HLA-A2 and HLA-A24 alleles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of prostate cancer patients. In addition, we have reported one such peptide derived from prostate acid phosphatase (PAP) protein, an appropriate target molecule for a cancer vaccine because of its overexpression in prostate cancer and also colon and gastric cancer, as reported previously [15].

Materials and methods

Patients

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from prostate cancer patients who had provided written informed consent. None of the participants were infected with HIV. A total of 20 mL of peripheral blood was obtained, and PBMCs were prepared by the Ficoll-Conray density (1.077 at room temperature) centrifugation method. All of the samples were cryopreserved until used for the experiments. The expression of HLA-A2 and HLA-A24 molecules on PBMCs of cancer patients was determined by flow cytometry using the anti-HLA-A2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and anti-HLA-A24 mAb, while HLA-A2 subtypes of HLA-A2+ patients were determined using DNA-based HLA typing with the Luminex Multi-Analyte Profiling system (xMAP) with the WAKFlow HLA typing kit (Wakunaga, Hiroshima, Japan) [16].

Cell lines

The cell lines used as target cells for cytotoxicity were COLO205 (HLA-A*0101/A*0201) and COLO320 (HLA-A*2402) colon cancer cell lines and PC3 (HLA-A*2402) and LNCaP (HLA-A*0201) prostate cancer cell lines. All of these cell lines highly express PAP antigens, as reported previously [15]. LNCaP cells weakly express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules on the surface [17]. Subsequently, we used COLO205 or COLO320 tumor cells to measure HLA-A2-restricted CTL activity as relevant or irrelevant target cells, respectively. In addition, PC3 and LNCaP tumor cells were used to measure HLA-A24-restricted CTL activity as relevant and irrelevant target cells, respectively. All tumor cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (MP Biomedicals, Inc, Germany). For pulsing a peptide to measure interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by peptide-stimulated PBMCs, as reported previously [15], we used T2 cells (HLA-A2, T-B hybridoma) or C1R-A*2402 cells (HLA-A*2402 gene-stable transfectant of the B lymphoblastoid cell line, kindly provided by Dr. M. Takiguchi, Kumamoto University, Japan), as also reported previously [18]. RMA-S cells were derived from a mouse mutant cell line deficient in antigen processing and that showed decreased cell surface expression of MHC class I molecules. The HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, -A*0207, -A*2402, and -A*2601 genes were also individually transfected into RMA-S cells using the FuGENE transfection reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Stably transfected cloned cells were established from a separate well in the presence of genetecin (0.5 mg/mL). The detailed methods for establishing these transfectants have been reported previously [11].

Peptides

Peptides with more than 90% purity were purchased from Hokkaido System Science (Sapporo, Japan) or Genenet (Fukuoka Japan), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL. Fourteen peptides (Table 1) capable of inducing HLA-A3 supertype (-A3, -A11, -A31, and -A33)-restricted CTL, as reported previously [10–14], were used in this study. In addition, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-derived and HIV-derived peptides were used as controls binding to HLA-A2 and -A24 alleles, as reported previously [19–22]. Furthermore, the positive-control peptide used for HLA-A26 was NS31582–1590 [23].

Table 1.

Peptide sequences used in this study

| Peptide | Amino acids sequence | Binding score (BIMAS) | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A3 | A*1101 | A*3101 | A*3302 | A*0201 | A24 | |||

| SART3511–519 | WLEYYNLER | 24.000 | 0.160 | 4.000 | 9.000 | 0.004 | 0.017 | [12] |

| SART3734–742 | QIRPIFSNR | 2.700 | 0.080 | 4.000 | 15.000 | 0.000 | 0.020 | [12] |

| Lck90–98 | ILEQSGWWK | 60.000 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.300 | 0.067 | 0.015 | [14] |

| Lck449–458 | VIQNLERGYR | 0.120 | 0.080 | 2.000 | 15.000 | 0.002 | 0.015 | [14] |

| PAP248–257 | GIHKQKEKSR | 0.600 | 0.120 | 1.000 | 15.000 | 0.002 | 0.010 | [10] |

| PSA16–24 | GAAPLILSR | 0.540 | 0.240 | 0.800 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 0.014 | [10] |

| IEX147–56 | APAGRPSASR | 0.090 | 0.040 | 0.200 | 3.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | [13] |

| β-tubulin5154–162 | KIREEYPDR | 1.800 | 0.240 | 6.000 | 4.500 | 0.003 | 0.024 | [11] |

| β-tublin5309–318 | RYLTVAAVFR | 0.006 | 0.036 | 3.600 | 4.500 | 0.000 | 1.500 | [11] |

| CGI37-72 | KFTKTHKFR | 0.006 | 0.060 | 0.900 | 0.900 | 0.000 | 0.100 | [11] |

| PAP155–163 | YLPFRNCPR | 4.000 | 0.080 | 2.000 | 9.000 | 0.069 | 0.015 | [10] |

| PSMA207–215 | KVFRGNKVK | 15.000 | 6.000 | 0.900 | 0.150 | 0.007 | 0.020 | [10] |

| IEX61–69 | RSRRVLYPR | 0.135 | 0.024 | 0.600 | 4.500 | 0.000 | 0.028 | [13] |

| Lck450–459 | IQNLERGYR | 0.036 | 0.120 | 2.000 | 3.000 | 0.002 | 0.015 | [14] |

| EBV-A2 | GLCTLVAML | 5.400 | 0.012 | 0.040 | 0.300 | 49.134 | 4.800 | [18] |

| EBV-A24 | TYGPVFMCL | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.024 | 0.500 | 0.006 | 403.200 | [19] |

| HIV-A2 | SLYNTVATL | 9.000 | 0.008 | 0.120 | 0.300 | 157.227 | 4.000 | [20] |

| HIV-A24 | RYLRQQLLGI | 0.003 | 0.036 | 0.144 | 0.150 | 0.012 | 150.000 | [21] |

| NS31582–1590 | DNFPYLVAY | 0.081 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.120 | [22] |

The peptide-binding score was calculated based on the predicted half time of dissociation from HLA-class I molecules, as obtained from a website (Bioinformatics and Molecular Analysis Section, Computational Bioscience and Engineering Laboratory, Division of Computer Research and Technology, the National Institutes of Health)

EBV Epstein-Barr virus, HLA human leukocyte antigen

HLA stabilization assay

Binding of peptides to HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, -A*0207, -A*2402, and -A*2601 molecules was examined using the stabilization assay according to a previously reported method with several modifications [9]. Briefly, RMA-S-A*0201, -A*0206, -A*0207, -A*2402, and -A*2601 (5 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well plate) were cultured at 26°C for 20 h in 500 μL RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) followed by incubation with 500 μL Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) containing 0.1–100 μM peptides and human β2 microglobulin (2 μg/mL) at 26°C for 2 h and then at 37°C for 3 h. After being washed with PBS, the cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with an appropriate dilution of anti-HLA-A24 or BB7.2 supernatant (anti-HLA-A2). After two more washes with PBS, the cells were incubated for 30 min on ice with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen). Peptides that, when incubated with cells at a concentration of 100 μM, gave more than 25% of the mean fluorescence intensity of cells cultured at 26°C, were defined as binding peptides.

Induction of peptide-specific CTLs from PBMCs

The assay for peptide-specific CTLs from prostate cancer patients was carried out according to a previously reported method with several modifications [10]. PBMCs (1 × 105 cells per well in a 96-well U-bottom-type plate) were incubated with 10 μg/mL of each peptide in culture medium in a quadruplicate assay. The culture medium consisted of 45% RPMI-1640, 45% AIM-V medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD), 10% FBS, 100 U/mL interleukin-2, and 0.1 mM MEM nonessential amino acid solution (Life Technologies). On day 15 of culture, cells were separated into four wells. Two wells were used for the culture with the corresponding peptide-pulsed T2 or C1R-A*2402 cells, and the other two wells were used for the culture with the irrelevant (HIV) peptide. After an 18-h incubation, IFN-γ production was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The induction of peptide-specific CTLs was judged to be successful when the P value was less than 0.05 and when the difference in IFN-γ production compared to that of the control HIV peptide exceeded 50 pg/mL.

Cytotoxicity assay

Peptide-stimulated PBMCs were tested for their cytotoxicity against PC3, LNCaP, COLO205, and COLO320 cells, which were pre-pulsed with either a corresponding peptide or the HIV peptide by a standard 6-h 51Cr-release assay [13]. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-activated T cells were used as a negative control. A total of 2,000 51Cr-labeled cells per well were cultured with effector cells in 96 round-well plates at the indicated effector/target ratio. Immediately before the cytotoxicity assay, CD8+ T cells were positively isolated using a CD8-positive Isolation Kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). The specific 51Cr release was calculated according to the formula: %specific lysis = (test sample release − spontaneous release) × 100/(maximum release − spontaneous release). Spontaneous release was determined by the supernatant of the sample incubated with no effector cells, and the total release was then determined by the supernatant of the sample incubated with 1% Triton 100-X (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). In some experiments, 10 μg/mL of either anti-HLA class I (W6/32: mouse IgG2a), anti-HLA-DR (L243: mouse IgG2a), or anti-HLA-B, C (B1-23, IgG2a; kindly donated by Dr. Pierre G. Coulie, Catholique de Louvain University, Brussels, Belgium) were added into the wells at the initiation of the culture.

The specificity of peptide-stimulated CTLs was confirmed by a cold inhibition assay. In brief, 51Cr-labeled target cells (2 × 104 cells per well) were cultured with the effector cells (2 × 104 cells per well) in 96 round-well plates with 2 × 104 cold target cells. T2 or C1R-A*2402, pulsed with either the HIV peptide or a corresponding peptide, were used as cold target cells.

Statistical analysis

The results of the absorption test were analyzed by a two-tailed Student’s t test. All tests of significance were two sided.

Results

HLA stabilization assay

We first screened the binding activity of each of the 14 different HLA-A3 supertype peptides (100 μM) to HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, -A*0207, -A*2402, and -A*2601 alleles, by means of an HLA stabilization assay using RMA-S cells expressing each HLA molecule. Only the PAP155–163 peptide showed binding activity to HLA-A*0201 or -A*0206 molecules, while PAP155–163 peptide and β-tubulin 5309–318 peptide were positive for binding to HLA-A*2402 molecules (data not shown). Subsequently, we focused on the PAP155–163 peptide; the study of the β-tubulin 5309–318 peptide is described in another study.

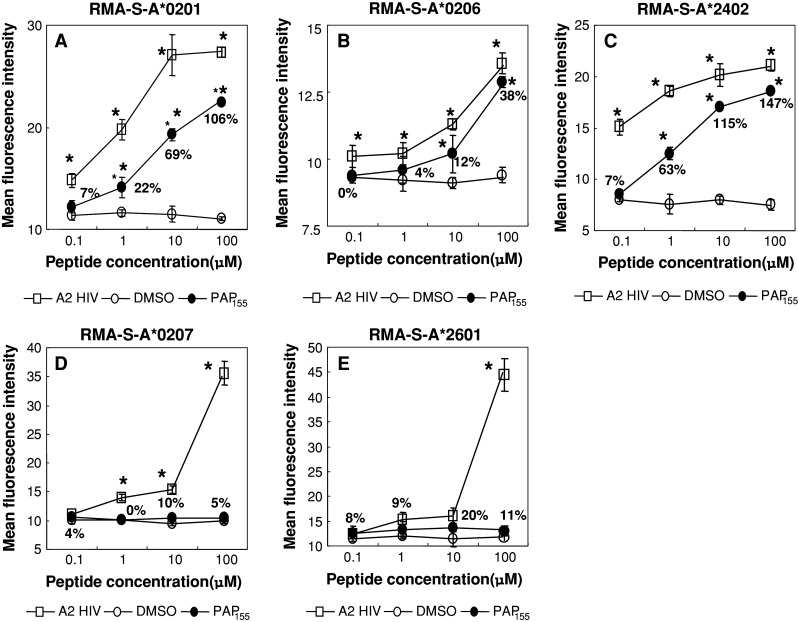

The surface expression of HLA-A*0201 molecules on RMA-S-A*0201 cells was stabilized in a dose-dependent manner when cells were cultured with either a positive control or the PAP155–163 peptide (MFI increases at 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM were 7, 22, 69, and 106%, respectively), whereas the expression was not stabilized when cells were cultured with DMSO alone (Fig. 1a). Similarly, HLA-A*0206 and -A*2402 molecules on RMA-S-A*0206 and -A*2402 cells, respectively, were stabilized when cultured with PAP155–163 peptide (Fig. 1b, c). However, this peptide failed to stabilize either HLA-A*0207 or -A*2601 molecules on RMA-S-A*0207 or -A*2601 cells, respectively (Fig. 1d, e).

Fig. 1.

Stabilization assay of the PAP155–163 peptide for various HLA alleles. The binding activities of the PAP155–163 peptide to HLA-A*0201 and -A*2402 were examined using stable transfectant cell lines RMA-S-A*0201 (a), -A*0206 (b), -A*2402 (c), -A*0207 (d), and -A*2601 (e) with a positive-control peptide and negative control (DMSO). The positive-control peptides used for each HLA were HIV-A2 (a, b), HIV-A24 (c), EBV-A2 (d), and NS3 1582–1590 (e). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was recorded at 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μM of the peptide or DMSO. The MFI increase induced by the PAP155–163 peptide compared with DMSO was calculated and is shown in a, b, and c. However, the MFI levels induced by the PAP155–163 peptide were comparable in degree to DMSO (d), (e). Representative results from at least three separate experiments are shown. Asterisks statistically significant at P < 0.05

Induction of peptide-specific CTL activity

We attempted to determine whether or not the PAP155–163 peptide has the potential to generate peptide-specific CTLs from prostate cancer patients by the IFN-γ production assay. PBMCs with different HLA alleles were stimulated in vitro with PAP155–163 peptide, positive (EBV) control peptide, or negative (HIV) control peptide, followed by measurement of IFN-γ production in response to the appropriate peptide-pulsed cells. As a result, this peptide induced peptide-specific CTL activity from the PBMCs of both HLA-A*0201 (patients 1, 3, and 6) and HLA -A*0206/A*0207 (patient 2) patients among six prostate cancer patients tested (Table 2). Three of the six patients showed CTL activity reactive to EBV-derived peptide but not to HIV-derived peptide. The PAP155–163 peptide-induced CTL activity in four out of six HLA-A*2402 prostate cancer patients tested (Table 2). Three of the six patients showed CTL activity reactive to EBV-derived peptide but not to HIV-derived peptide.

Table 2.

Induction of peptide-specific CTL from prostate cancer patients

| Pt | HLA allele | Target cells | IFN-γ production (pg/mL) in response to | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAP155–163 | EBV-A2 | HIV-A2 | EBV-A24 | HIV-A24 | |||

| HLA-A*0201/A*0206 | |||||||

| 1 | A0201/- | T2 | 50 | 155 | 23 | – | – |

| 2 | A0206/A0207 | T2 | 308 | 10 | 45 | – | – |

| 3 | A0201/- | T2 | 50 | 578 | 29 | – | – |

| 4 | A0201/- | T2 | 30 | 5 | 0 | – | – |

| 5 | A0201/A0206 | T2 | 18 | 126 | 2 | – | – |

| 6 | A0201/A0206 | T2 | 139 | 35 | 22 | – | – |

| HLA-A*2402 | |||||||

| 7 | A2402/- | C1R-A*2402 | 90 | – | – | 71 | 0 |

| 8 | A2402/- | C1R-A*2402 | 51 | – | – | 51 | 0 |

| 9 | A2402/- | C1R-A*2402 | 78 | – | – | 0 | 21 |

| 10 | A2402/- | C1R-A*2402 | 37 | – | – | 14 | 44 |

| 11 | A2402/- | C1R-A*2402 | 13 | – | – | 539 | 1 |

| 12 | A2402/- | C1R-A*2402 | 70 | – | – | 44 | 8 |

The PBMCs from HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, and -A*2402 prostate cancer patients were induced in vitro with PAP155–163 peptide. On day 15, the cultured PBMCs were tested for their reactivity to C1R-A*2402 and T2 cells, which were pre-pulsed with a corresponding peptide or the HIV peptide. The peptide-specific CTL was measured by means of IFN-γ release assay with ELISA. Representative results are shown. Background IFN-γ production in response to the HIV peptide was subtracted from that in response to PAP155–163 peptide

The induction of peptide-specific CTLs was judged to be successful when the P value was less than 0.05 and when the difference in IFN-γ production compared to that of the control HIV peptide exceeded 50 pg/mL. In this table, the value is shown as bold only when there is a significant difference between the two groups

Cytotoxicity assay

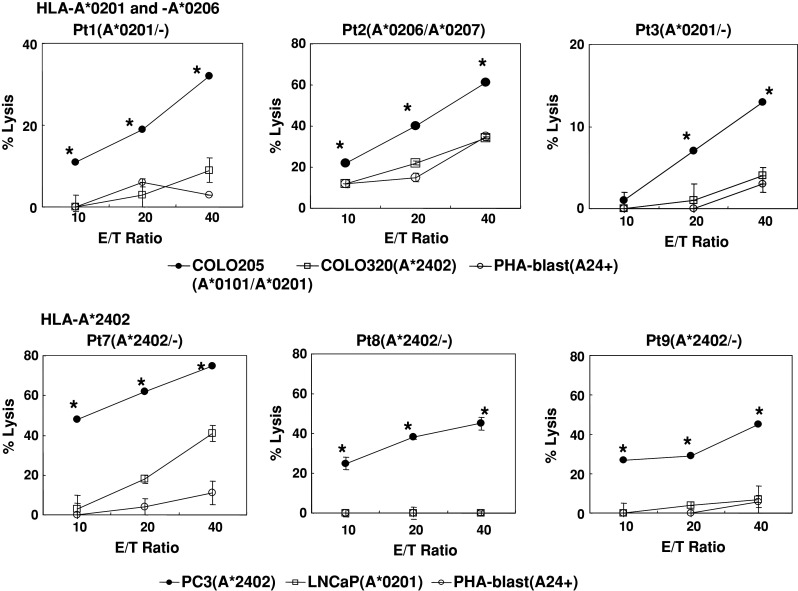

We then determined whether or not the CTLs induced by in vitro stimulation with the PAP155–163 peptide could show cytotoxicity against cancer cells. The PBMCs from HLA-A*0201 (patients 1 and 3) or -A*0206/A*0207 (patient 2) patients, which were stimulated in vitro with PAP155–163 peptide, exhibited significant levels of cytotoxicity against COLO205 cells but not against COLO320 cells or HLA-A2+ PHA-stimulated T-cell blasts. Similarly, the PBMCs from HLA-A*2402 patients showed that this peptide possessed the ability to induce PC3-reactive CTLs from the PBMCs of HLA-A*2402 patients, but not from LNCaP cells or HLA-A2402+ PHA-stimulated T-cell blasts (Fig. 2). We further examined CTL activity by means of the chromium release assay in PBMCs from four patients whose samples responded negatively in the IFN-γ assay, as shown in Table 2. None of the patients showed detectable levels of CTL activity with this assay.

Fig. 2.

Cytotoxicity of peptide-stimulated PBMCs from HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, and -A*2402 prostate cancer patients. Peptide-stimulated PBMCs were tested for their cytotoxicity toward three different targets by a 6-h 51Cr-release assay. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated T-cell blasts were included as HLA-A2+ or -A24+ normal cells. Asterisks statistically significant at P < 0.05

Taken together, these results indicate that the PBMCs stimulated in vitro with this peptide can exhibit cytotoxicity against cancer cells in HLA-A*0201-, -A*0206-, and -A*2402-restricted ways.

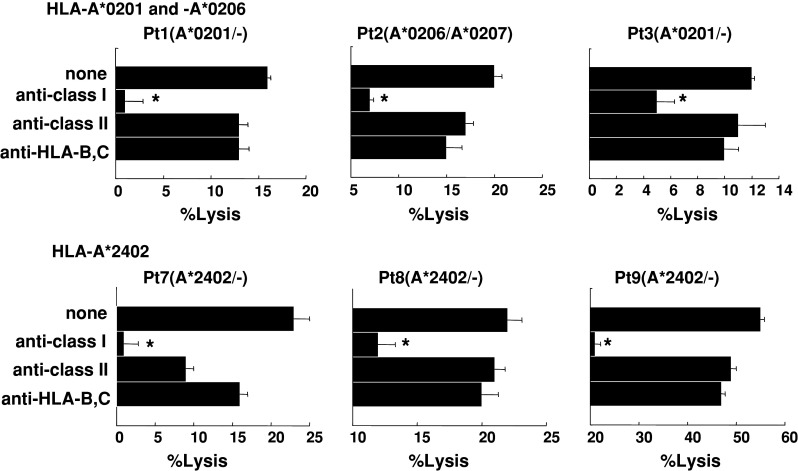

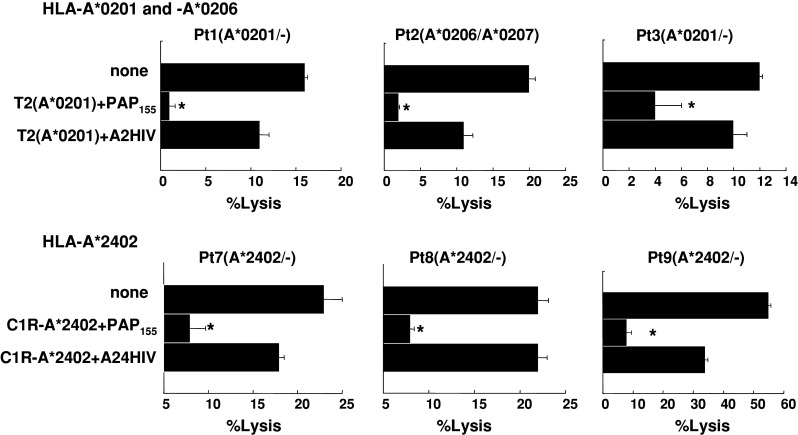

We further attempted to identify the cells responsible for the cytotoxicity of PAP peptide-stimulated PBMCs. Purified CD8+ T cells were used in the following experiments. The cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells purified from the peptide-stimulated PBMCs against PC3 and COLO205 was significantly decreased by the addition of anti-HLA class I mAb (W6/32) but not by the addition of either anti-HLA class II (HLA-DR) or anti-HLA-B,C (B1-23, IgG2a) mAbs (Fig. 3). In addition, cytotoxicity was significantly inhibited by the addition of corresponding peptide-pulsed unlabeled C1R-A*2402 or T2 cells but not by the addition of HIV peptide-pulsed unlabeled C1R-A*2402 or T2 cells. These results suggested that the cytotoxicity of peptide-stimulated PBMCs against PAP-expressing cancer cells depended mainly on HLA class I-restricted and PAP peptide-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition assay of peptide-stimulated PBMCs with Abs. Peptide-stimulated PBMCs from two HLA-A*0201, one -A*0206, and three -A*2402 patients were tested for their cytotoxicity against COLO205 and PC3 cells expressing each of the HLA-A*0201 and -A*2402 alleles, respectively in the presence of the indicated monoclonal antibodies. Asterisks statistically significant at P < 0.05

Fig. 4.

Inhibition assay of peptide-stimulated PBMCs with peptides. Peptide-stimulated PBMCs from six patients were tested for their cytotoxicity against COLO205 and PC3 cells expressing the HLA-A*0201 and -A*2402 alleles, respectively in the presence of unlabeled T2 and C1R-A*2402 cells, which were preloaded with either the corresponding peptide or the HIV peptide. Asterisks statistically significant at P < 0.05

Discussion

Several HLA-class I-A alleles, such as HLA-A1, are relatively dominant outside of Japan. In this study, since we could not obtain HLA-A1+ PBMCs, we were unable to test the ability of HLA-A3 supertype peptides to induce CTLs restricted to those alleles. Also, we could not test the binding activity to HLA-A*2602, -A*2603, or the HLA-A2 subtypes other than -A*0201, -A*0206, and -A*0207 because of the difficulty of obtaining samples. These issues shall be addressed in the near future.

Peptides used as cancer vaccines usually consist of nine or ten amino acids that can bind to particular MHC molecules and activate CTLs reactive to cancer cells or viral infection in a particular MHC-restricted manner. Although peptide–MHC binding was previously thought to be very specific, recent studies have shown that it is neither as narrowly specific nor as unique as originally believed. Sidney and colleagues have pointed out that, among 945 different HLA-A and -B alleles examined to date, over 80% can be assigned to one of the nine subtypes, whereas the remaining alleles might be associated with repertoires that overlap multiple supertypes [8, 24, 25]. The molecular mechanisms of these phenomena are presently unclear, though the stereophonic structure of both the B and F pockets plays a crucial role for binding. Crystallographic studies have revealed that residues 7, 9, 24, 34, 45, 63, 66, 67, 70, and 99 are considered to make up the B pocket, which engages the peptide residue in position 2. The residues that constitute the F pocket, which engages the peptide C-terminal residue, were defined as 74, 77, 80, 81, 84, 95, 97, 114, 116, 123, 133, 143, 146, and 147 [24]. Further studies will clarify these phenomena.

The current results suggest the possibility that one peptide can bind to several different HLA alleles. In fact, this phenomenon has been reported by many other researchers [24]. In this study, we have shown that the PAP155–163 peptide, a previously reported peptide capable of inducing HLA-A3 supertype-restricted CTLs [10], could bind to multiple HLA molecules including HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, and -A*2402, the dominant HLA types in the Japanese population.

The binding scores of HLA-A*0201 and -A24 of PAP155–163 (YLPFRNCRP) on BioInformatics and Molecular Analysis Section (BIMAS) are very low compared to those of the HLA-A3 supertypes (Table 1). However, we showed that the PAP155–163 peptide can bind only to HLA-A*0201-, -A*0206-, and -A*2402-transfected cells. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but the binding of this peptide to HLA-A*0201-, -A*0206-, and -A*2402-transfected cells could be expected; the binding motifs of HLA-A2 binding peptides are characterized by the presence of I or L residues at amino acid position 2 and V, F, or M residues at the C terminus [26]. However, merely belonging to the HLA-A2 genealogy does not ensure belonging to the supertype, as exemplified by HLA-A*0207. Guercio et al. [27] have shown that the HLA-A2 supertype binding peptide does not bind -A*0207. Therefore, the binding motif of HLA-A*0207 could be largely different from that of HLA-A*0201 or -A*0206.

HLA-A24 binding peptides are characterized by the presence of Y or F residues at amino acid position 2 and L, F, I, or W residues at their C terminus [28]. Analysis of published epitopes recognized by HLA-A*2301 suggests that its peptide-binding specificity might overlap with that of HLA-A*2402. Thus, an HLA-A24 supermotif incorporating residues commonly recognized by HLA-A24 supertype alleles may be defined as (FWYLVIMT) and (FIYWLM) [8]. These findings suggest the possibility that the PAP155–163 peptide (YLPFRNCPR) can bind to HLA-A*0201, -A*0206, and -A*2402 molecules and cannot bind to HLA-A*0207.

Prostate acid phosphatase is a prostate-related antigen capable of inducing anti-tumor responses when injected as a cancer vaccine into prostate cancer patients [29]. However, several reports have shown PAP expression in tissues other than those of the prostate and prostate cancer [15, 30–36]. PAP was reported to be immunohistologically positive in neuroendocrine tumors in the pancreas and in small intestine tumors, pancreas endocrine tumors, hindgut-origin tumors, pancreatic islet cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas of the urinary bladder [30–32]. Recently, PAP was suggested to be a tumor marker of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma [33]. We have also reported that PAP is expressed in esophageal and lung squamous cell carcinoma cells and PAP-specific CTLs can show cytotoxicity to these tumor cells [34]. In addition, several reports suggest that PAP is expressed in normal tissues, including the normal anal glands of the male and the urethral glands of both sexes [35, 36]. We incidentally found that normal pyloric glands in gastric mucosa express PAP [15].

Small et al. performed a phase 1 clinical trial for patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer using autologous dendritic cells that were loaded with a recombinant fusion protein consisting of PAP and granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor. They revealed that the specific immunotherapy targeting PAP is safe and the time to disease progression correlates with the development of the anti-PAP immune response [29, 37]. We also reported that a PAP-derived peptide capable of inducing HLA-A24-restricted CTL activity at positions 213–221 was one of the key peptides inducing clinical responses in prostate cancer patients receiving tailor-made peptide vaccines [5, 6]. These results suggest that PAP is one of the appropriate target molecules of a cancer vaccine.

We previously reported that the employed CTL assay with a 14-day incubation with 5× stimulation could not detect CTL precursors by de novo sensitization to PAP [38]. The sensitivity of this CTL assay was 1 out of 3,000 to 1 out of 5,000 CTL precursors. Thus, the immune response against the PAP-155 peptide is suggested to be relatively specific to PAP because naïve T cells from healthy donors are more difficult to induce when compared to those from prostate cancer patients. Indeed, it was relatively easy to induce a PAP-155-specific CTL in prostate cancer patients, although CTL precursors were not detectable in 4 of the 12 patients tested. This failure might be in part due to immune suppression associated with advanced prostate cancer. On the other hand, more than seven attempts were needed to induce CTL in the cases of healthy donors (data not shown).

In conclusion, HLA-A2, -A24, and -A3 supertypes constitute 98% of the Asian population, 74% of Caucasians, 72% of Spaniards, 76% of Asian Indians, and 59% of Black Africans. Thus, this peptide could be useful as a cancer vaccine for the majority (~60%) of prostate cancer patients as well as for colon and gastric cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (no. 12213134 to KI and no. 18591449 to MH), the Research Center of Innovative Center Therapy of 21st COE Program for Medical Science (to KI, SS, and MH), and the Toshi-area program (to KI, SS, and MH).

References

- 1.Barve M, Bender J, Senzer N, Cunningham C, Greco A, McCune D, Steis R, Khong H, Richards D, Stephenson J, Ganesa P, Nemunaitis J, Ishioka G, Pappen B, Nemunaitis M, Morse M, Mills B, Maples PB, Sherman J, Nemunaitis JJ. Induction of immune response and clinical efficacy in a phase II trial of IDM-2101, a 10-epitope cytotoxic T-lymphocyte vaccine, in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;27:4418–4425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampson JH, Archer GE, Bigner DD, Davis T, Friedman HS, Keler T, Mitchell DA, Reardon DA, Sawaya R, Heimberger AB. Effect of EGFRvIII-targeted vaccine (CDX-110) on immune response and TTP when given with simultaneous standard and continuous temozolomide in patients with GBM. Abstract of Annual Meeting of American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA, Smolkin ME, Hibbitts S, Murphy C, Johansen N, Grosh WW, Yamshchikov GV, Neese PY, Patterson JW, Fink R, Rehm PK. Immunologic and clinical outcomes of a randomized phase II trial of two multipeptide vaccines for melanoma in the adjuvant setting. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6386–6395. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noguchi M, Kobayashi K, Suetsugu N, Tomiyasu K, Suekane S, Yamada A, Itoh K, Noda S. Induction of cellular and humoral immune responses to tumor cells and peptides in HLA-A24 positive hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients by peptide vaccination. Prostate. 2003;57:80–92. doi: 10.1002/pros.10276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noguchi M, Mine T, Yamada A, Obata Y, Yoshida K, Mizoguchi J, Harada M, Suekane S, Itoh K, Matsuoka K. Combination therapy of personalized peptide vaccination and low-dose estramustine phosphate for metastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer patients. An analysis of prognostic factors in the treatment. Oncol Res. 2007;16:341–349. doi: 10.3727/000000006783980955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itoh K, Yamada A. Personalized peptide vaccines. A new therapeutic modality for cancer. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:970–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagorsen D, Thiel E. HLA typing demands for peptide-based anti-cancer vaccine. Cancer Immunol Immunotherapy. 2008;57:1903–1910. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0493-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sette A, Sidney J. Nine major HLA class I supertypes account for the vast preponderance of HLA-A and -B polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s002510050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed RE, Naito M, Terasaki Y, Niu Y, Gohara S, Komatsu N, Shichijo S, Itoh K, Noguchi M. Capability of SART3109-118 peptide to induce cytotoxic T-lymphocytes from prostate cancer patients with HLA class I-A11, -A31, and -A33 alleles. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsueda S, Takedatsu H, Yao A, Tanaka M, Noguchi M, Itoh K, Harada M. Identification of peptide vaccine candidates for prostate cancer patients with HLA-A3 supertype alleles. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6933–6943. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takedatsu H, Shichijo S, Katagiri K, Sawamizu H, Sata M, Itoh K. Identification of peptide vaccine candidates sharing among HLA-A3+, -A11+, -A31+, and -A33+ cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1112–1120. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-0797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minami T, Matsueda S, Takedatsu H, Tanaka M, Noguchi M, Uemura H, Itoh K, Harada M. Identification of SART3-derived peptides having the potential to induce cancer-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes from prostate cancer patients with HLA-A3 supertype alleles. Cancer Immunol Immunotherapy. 2007;56:689–698. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsueda S, Takedatsu H, Sasada T, Azuma K, Noguchi M, Shichijo S, Itoh K, Harada M. New peptide vaccine candidates for epithelial cancer patients with HLA-A3 supertype alleles. J Immunotherapy. 2007;30:274–281. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211340.88835.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naito M, Komohara Y, Ishihara Y, Noguchi M, Yamashita Y, Shirakusa T, Yamada A, Itoh K, Harada M. Identification of Lck-derived peptides applicable to anti-cancer vaccine for patients with human leukocyte antigen-A3 supertype alleles. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1648–1654. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Harada M, Yano H, Ogasawara S, Takedatsu H, Arima Y, Matsueda S, Yamada A, Itoh K. Prostatic acid phosphatase as a target molecule in specific immunotherapy for patients with nonprostate adenocarcinoma. J Immunotherapy. 2005;28:535–541. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175490.26937.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoa BK, Hang NTL, Kashiwase K, Ohashi J, Lien LT, Horie T, Shojima J, Hijikata M, Sakurada S, Satake M, Tokunaga K, Sasazuki T, Keicho N. HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 alleles and haplotypes in the Kinh population in Vietnam. Tissue Antigens. 2007;71:127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlsson B, Forsberg O, Bengtsson M, Tötterman TH, Essand M. Characterization of human prostate and breast cancer cell lines for experimental T cell-based immunotherapy. Prostate. 2007;67:389–395. doi: 10.1002/pros.20498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oiso M, Eura M, Katsura F, Takiguchi M, Sobao Y, Masuyama K, Nakashima M, Itoh K, Ishikawa T. A newly identified MAGE-3-derived epitope recognized by HLA-A24-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:387–394. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990505)81:3<387::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steven NM, Annels NE, Kumar A, Leese AM, Kurilla MG, Rickinson AB. Immediate early and early lytic cycle proteins are frequent targets of the Epstein-Barr virus-induced cytotoxic T cell response. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1605–1617. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SP, Tierney RJ, Thomas WA, Brooks JM, Rickinson AB. Conserved CTL epitopes within EBV latent membrane protein 2 A potential target for CTL-based tumor therapy. J Immunol. 1997;158:3325–3334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Hull LK, Utz U, Cunningham B, Zweerink HJ, Biddison WE, Coligan JE. Sequence motifs important for peptide binding to the human MHC class I molecule, HLA-A2. J Immunol. 1992;149:3580–3587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda-Moore Y, Tomiyama H, Miwa K, Oka S, Iwamoto A, Kaneko Y, Takiguchi M. Identification and characterization of multiple HLA-A24-restricted HIV-1 CTL epitopes: strong epitopes are derived from V regions of HIV-1. J Immunol. 1997;159:6242–6252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neumann-Haefelin C, Killinger T, Timm J, Southwood S, McKinney D, Blum HE, Thimme R. Absence of viral escape within a frequently recognized HLA-A26-restricted CD8+ T-cell epitope targeting the functionally constrained hepatitis C virus NS5A/5B cleavage site. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1986–1991. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sidney J, Peters B, Frahm N, Brander C, Sette A. HLA class I supertypes: a revised and updated classification. BMC Immunol. 2008;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torikai H, Akatsuka Y, Miyauchi H, Terakura S, Onizuka M, Tsujimura K, Miyamura K, Morishima Y, Kodera Y, Kuzushima K, Takahashi T. The HLA-A*0201-restricted minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1H peptide can also be presented by another HLA-A2 subtype, A*0206. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2007;40:165–174. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rammensee HG, Flak K, Rotzschke O. Peptides naturally presented by MHC class I molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:213–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guercio MF, Sidney J, Hermanson G, Perez C, Grey HM, Kubo RT, Sette A. Binding of a peptide antigen to multiple HLA alleles allows definition of an A2-like supertype. J Immunol. 1995;154:685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maier R, Falk K, Rotzschke O, Maier B, Gnau V, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Rammensee HG, Meyerhans A. Peptide motifs of HLA-A3, -A24, and -B7 molecules as determined by pool sequencing. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:306–308. doi: 10.1007/BF00189978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Small EJ, Fratesi P, Reese DM, Strang G, Laus R, Peshwa MV, Valone FH. Immunotherapy of hormone-refractory prostate cancer with antigen-loaded dendritic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3894–3903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.23.3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Epstein JI, Kuhajda FP, Lieberman PH. Prostate-specific acid phosphatase immunoreactivity in adenocarcinomas of the urinary bladder. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:939–942. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(86)80645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura N, Sasano N. Prostate-specific acid phosphatase in carcinoid tumors. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;410:247–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00710831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaneko Y, Motoi N, Matsui A, Motoi T, Oka T, Machinami R, Kurokawa K. Neuroendocrine tumors of the liver and pancreas associated with elevated serum prostatic acid phosphatase. Intern Med. 1995;34:886–891. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seki K, Miyakoshi S, Lee GH, Matsushita H, Mutoh Y, Nakase K, Ida M, Taniguchi H. Prostatic acid phosphatase is a possible tumor marker for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1384–1388. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000132743.89349.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue Y, Takaue Y, Takei M, Kato K, Kanai S, Harada Y, Tobisu K, Noguchi M, Kakizoe T, Itoh K, Wakasugi H. Induction of tumor specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in prostate cancer using prostatic acid phosphatase derived HLA-A2402 binding peptide. J Urol. 2001;166:1508–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65821-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamoshida S, Tsutsumi Y. Extraprostatic localization of prostatic acid phosphatase and prostate-specific antigen: distribution in cloacogenic glandular epithelium and sex-dependent expression in human anal gland. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:1108–1111. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90146-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tepper SL, Jagirdar J, Heath D, Geller SA. Homology between the female paraurethral (Skene’s) glands and the prostate. Immunohistochemical demonstration. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:423–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burch PA, Breen JK, Buckner JC, Gastineau DA, Kaur JA, Laus RL, Padley DJ, Peshwa MV, Pitot HC, Richardson RL, Smits BJ, Sopapan P, Strang G, Valone FH, Vuk-Pavlovic S. Priming tissue-specific cellular immunity in a phase I trial of autologous dendritic cells for prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2175–2182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hida N, Maeda Y, Katagiri K, Takasu H, Harada M, Itoh K. A simple culture protocol to detect peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte precursors in the circulation. Cancer Immunol Immunotherapy. 2002;51:219–228. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0273-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]