Abstract

Purpose

Although relatively rare, uveal melanoma is the most common ocular tumor of adults. Up to half of uveal melanoma patients die of metastatic disease. CXCR4, a chemokine receptor, is a prognostic factor in cutaneous melanoma involved in angiogenesis and metastasis formation. The aim of this study was to evaluate the expression of CXCR4 in uveal melanoma.

Methods

CXCR4 was detected by immunohistochemistry in 44 samples of uveal melanoma. Staining was categorized into three semiquantitative classes based on the rate of stained (positive) tumor cells: absence of staining, <50% of cell (+) and >50% (++). Correlations between CXCR4 expression, data on patient and tumor features were studied by contingency tables and the χ2 test. Time-to-event curves were studied using the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate analysis was performed using the log-rank test. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) of hazard ratios were also reported.

Results

Staining for CXCR4 protein was absent in 18 tumors (40.9%), present in <50% of cells in 19 (43.2%) and in >50% of cells in 7 (15.9%) tumors. CXCR4 expression correlated to the epithelioid-mixed cell type (P = 0.030). No statistically significant relation emerged between CXCR4 expression, largest tumor diameter (LTD) and extracellular matrix patterns as evaluated through histological patterns stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). Events occurred in 2 out of 18 patients (11.1%) with negative tumors (2 deaths), in 3 out of 19 patients (15.8%) with <50% of positive tumor cells (2 deaths and 1 occurrence of metastases) and in 1 out of 7 patients (14.3%) with >50% of positive tumor cells (1 occurrence of metastases). The cell type (P = 0.0457) but not CXCR4 showed prognostic value at univariate analysis.

Conclusion

This study shows that CXCR4 is commonly expressed in uveal melanoma and correlates with cell type a well-established prognostic factor.

Keywords: CXCR4, Uveal melanoma, Prognostic factor

Introduction

Even though relatively rare (the incidence is about 0.7/100,000 population per year in western countries including USA) uveal melanoma is the most common ocular tumor of adults. The clinical course of cancer is related to the size of the tumor, the cell type, and the variability of the nucleolar size. The treatment of uveal melanoma depends on the size of the tumor and relies on a multimodal approach. Small melanomas are sometimes treated with an infrared laser often used in combination with other treatments, such as radiotherapy. Medium-sized uveal tumors are often treated with radiotherapy using radioactive seeds, which remains in place for several days before it is removed. Massive uveal melanomas are generally managed by removing the eye (enucleation) [1, 2]. The risk factors are fair skin, lightly pigmented eyes, dark choroidal pigmentation coupled with light iris coloration [1–3]. Up to 50% of uveal melanoma patients die of metastasis, which usually involves hematogenous spread to the liver, despite successful treatment of the primary eye tumor, at which time microscopic metastasis has already occurred.

Metastatic disease usually occurs from 2 to more than 10 years after ocular treatment with a mortality rate of 29% at 5 years, 40% at 10 years, and 45% at 15 years [4–6]. The process relies on the growth of quiescent metastatic clones established before treatment allowing up to 30 tumor cell doublings and the accumulation of a massive tumor burden that is resistant to therapy and causes death within 5–9 months [1–3]. In the biology of the uveal melanoma, mutations in cell-cycle checkpoints and DNA damage response genes have also been speculated to be important, but there is contradictory evidence in this regard [7, 8].

Cell type is a key factor in determining the prognosis of uveal melanoma. In 1931, Callender [3] noted that uveal melanomas often contain epithelioid cells, which were strongly associated with a poor prognosis. In 1992, Folberg [9] discovered that “looping” patterns of extracellular matrix were also associated with metastatic death. Although both epithelioid cytology and looping matrix patterns are now firmly established prognostic factors, neither is practical for clinical decision making because they are subjective and non-quantitative and form a continuous spectrum without clear-cut pathologic stages. Studies of gene expression profiling clustered primary uveal melanomas into two distinct groups, which have been designated class 1 and class 2 [8, 10]. Class 1 tumors were associated with an excellent prognosis, whereas class 2 tumors were associated with epithelioid cytology, looping matrix patterns, monosomy 3, and metastatic death [8, 10].

Based on the clinical and biological features, uveal melanoma appears as an ideal tumor for studying the mechanisms of distant metastasis and the efficacy of treating high-risk patients prophylactically for metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis.

It is known that chemokines play a role in tumor biology affecting migration, angiogenesis and cell growth. Expression of chemokine receptors on tumor cells and their involvement in metastases revealed that these receptors can provide migratory directions to tumor cells [11].

The most widely expressed chemokine receptor among cancer is likely to be CXCR4 described in breast cancer, glioblastoma, pancreatic, prostatic, colon, thyroid cancer, NSCLC [12]. The role of CXCR4 in melanoma has been predominantly studied in cutaneous melanoma where several chemokine receptors have been described. Expression of CXCR3 [13, 14] and CCR7 [15, 16] were mainly correlated to lymphnode metastases, while the expression of CCR10 was mainly detected in skin metastases [17]. CXCR4 was found in melanoma cell lines [15, 18] and its expression in primary cutaneous lesions was able to predict prognosis [19].

The role of the CXCR4-CXCL12 axis was also validated in preclinical models. In mice B16 melanoma cells transfected with CXCR4 produced increased number of pulmonary nodules compared with the lung metastases induced by B16 cells transfected with mock vector [20]. CXCR4 was also detected in human melanoma metastases, detectable and active in melanoma cell lines derived from melanoma metastases and specifically inhibited by the antagonist AMD3100 [18].

Most recently, the expression of CXCR4 and other chemokine receptors has been found in primary uveal melanomas and hepatic metastases [21]. Thus, aim of this work was to evaluate the expression of CXCR4 in uveal melanoma and to explore any clinical significance.

Materials and methods

Cases were selected from 1984 to 2003 at the Pathology Unit of Federico II, University of Naples. The histologic sections were reviewed by two expert pathologists (S.S. and R.F.) to verify the histologic diagnosis of uveal melanoma before performing immunohistochemistry. All patients of this study have been treated with enucleation.

Immunohistochemistry

Two serial 5-μm sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples were stained one by standard H & E and the other by the biotinstreptavidin-peroxidase method (YLEM). Deparaffinized sections were microwaved in 1 mmol/l EDTA (pH 8.0) for two cycles of 5 min each to unmask epitopes. After treatment with 1% hydrogen peroxidase for 30 min to block endogenous peroxidases, the sections were incubated with monoclonal antibodies (anti-CXCR4, clone 44716, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with biotin-labeled secondary antibody (1:30) for 30 min and with streptavidin-peroxidase (1:30) for 10 min. Slides were stained for 10 min with AEC chromogen (DAKO, Milan, Italy) and then counterstained with hematoxylin, washed and mounted in aqueous medium. The dilutions of the monoclonal antibody, biotin-labeled secondary antibody, and streptavidin-peroxidase were made with PBS (pH 7.4) containing 5% bovine serum albumin. All series included positive controls of well-characterized sections (melanomas and breast cancer). Negative controls were obtained by substituting the primary antibody with a mouse myeloma protein of the same subclass, at the same concentration as the monoclonal antibody. All controls gave satisfactory results. Cases were considered positive if 10% of neoplastic cells showed CXCR4 cytoplasmatic and/or membrane immunohistochemical expression. The cut-off level of 10% of tumor cells to score positive a slide was chosen after a consensus was reached among pathologists (RF, ALM, SS, BG, DRG). Macrophage positivity was used as adequate internal positive control for each case, to validate technical procedure.

Staining was categorized into three semiquantitative classes based on the rate of stained (positive) tumor cells: absence of staining, <50% of cell (+) and >50% (++). Topographical expression of CXCR4 was also evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Correlations between CXCR4 expression, data on patient and tumor features, and tumors were studied by contingency tables and the χ2 test. Time-to-event was defined as the time elapsed from the date of initial diagnosis to the occurrence of distant metastasis or death, whichever occurred first. Time-to-event curves were studied using the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate analysis was done with the log-rank test.

Results

Patient and tumor characteristics

Forty-four specimens from uveal melanomas surgically resected from 1984 to 2003, were tested for CXCR4 expression. In all cases, the diagnosis of uveal melanoma was confirmed. Characteristics of all patients are described in Table 1 and summarized in Table 2. Genders were equally represented. Median age was 62 years; 20 patients were over 65 years of age. Nineteen patients had a melanoma with a diameter of <1 cm, 18 with 1–1.5 cm and 6 with >1.5 cm. The neoplasms were classified as spindle melanomas (19 cases), epithelioid (13 cases) and mixed (12 cases). The histology was non-epithelioid for 19 patients and epithelioid for 25.

Table 1.

Detailed characteristics of patients and tumors

| Pt number | Cytotype | Sex | Age | LTD (mm) | Follow-up (months) | CXCR4 expression | PAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | scores | |||||||

| 1 | E | M | 60 | 15 | N(36) | 80 | ++ | S |

| 2 | S | M | 70 | 15 | N(100) | 10 | + | E |

| 3 | S | M | 70 | 15 | N(100) | 20 | + | E |

| 4 | S | M | 71 | Unknown | N(102) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 5 | S | F | 36 | 18 | N(68) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 6 | Mix | F | 84 | 12 | N(30) | 40 | + | NA |

| 7 | Mix | F | 70 | 13 | D(115) | 0 | 0 | TS |

| 8 | E | M | 65 | 13 | D(109) | 20 | + | NA |

| 9 | S | F | 66 | 6 | N(77) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 10 | S | M | 68 | 9.5 | N(56) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 11 | Mix | F | 74 | 16 | N(36) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 12 | Mix | M | 58 | 5 | N(72) | 80 | ++ | E |

| 13 | S | F | 54 | 8 | N(36) | 40 | + | S |

| 14 | E | F | 75 | 9.5 | N(36) | 40 | + | E |

| 15 | S | F | 62 | 18 | N(144) | 40 | + | NA |

| 16 | Mix | F | 82 | 3 | R(89) | 60 | ++ | TS |

| 17 | Mix | M | 78 | 20 | N(40) | 60 | ++ | NA |

| 18 | S | F | 59 | 12 | N(36) | 40 | + | S |

| 19 | Mix | F | 53 | 15 | R(80) | 20 | + | S |

| 20 | E | M | 25 | 9 | N(48) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 21 | E | F | 56 | 9 | N(36) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 22 | S | F | 66 | 8 | N(63) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 23 | Mix | M | 43 | 15 | N(36) | 40 | + | S |

| 24 | Mix | M | 56 | 15 | N(91) | 20 | + | E |

| 25 | E | F | 73 | 9 | N(67) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 26 | Mix | F | 73 | 20 | N(90) | 20 | + | S |

| 27 | S | M | 45 | 9 | N(39) | 20 | + | E |

| 28 | E | M | 73 | 20 | N(90) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 29 | E | M | 77 | 9.5 | N(36) | 60 | ++ | E |

| 30 | Mix | F | 61 | 12 | N(71) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 31 | S | F | 43 | 8 | N(61) | 40 | + | NA |

| 32 | E | M | 61 | 5 | D(92) | 10 | + | TS |

| 33 | E | F | 44 | 8 | D(112) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 34 | E | M | 73 | 5 | N(91) | 80 | ++ | S |

| 35 | S | F | 30 | 9.5 | N(50) | 30 | + | NA |

| 36 | S | M | 69 | 12 | N(48) | 20 | + | NA |

| 37 | S | F | 65 | 12 | N(70) | 30 | + | S |

| 38 | Mix | F | 72 | 13 | N(60) | 90 | ++ | NA |

| 39 | S | F | 52 | 4 | N(95) | 0 | 0 | S |

| 40 | E | F | 41 | 12 | N(70) | 0 | 0 | NE |

| 41 | S | M | 63 | 14 | N(48) | 0 | 0 | E |

| 42 | S | M | 27 | 14 | N(75) | 10 | + | S |

| 43 | E | M | 67 | 6 | N(55) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 44 | S | M | 54 | 12 | N(75) | 30 | + | E |

First column represents patients name initials (Pt)

Tumor histology: E epithelioid, S spindle, Mix mixed. M male, F female, INF infiltration, LTD largest tumor diameter, PAS periodic acid-Schiff. Uveal melanoma-related events: N no evidence of disease, D dead, R relapsed, R tumor blood vessel morphology is on the right column: S spheroidal vessels with intermediate size, E elongated thin vessels, TS tumor-surrounding vessels, NA not available

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients and tumors

| No. | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 21 | 47.7 |

| Female | 23 | 52.3 |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤65 | 24 | 54.5 |

| >65 | 20 | 45.5 |

| Diameter | ||

| <1 | 19 | 43.2 |

| 1–1.5 | 18 | 40.9 |

| >1.5 | 6 | 13.6 |

| Unknown | 1 | 2.3 |

| Histology | ||

| Non-epithelioid | 19 | 43.2 |

| Epithelioid | 25 | 56.8 |

| CXCR4 expression | ||

| Not expressed | 18 | 40.9 |

| ≤50% of cells | 19 | 43.2 |

| >50% of cells | 7 | 15.9 |

CXCR4 expression in uveal melanoma: pattern of expression

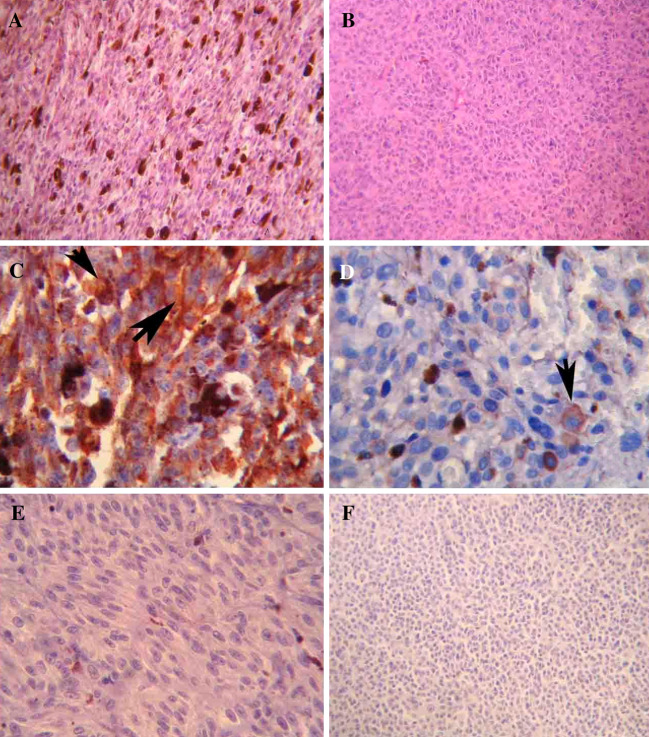

Staining for CXCR4 protein was absent in 18 tumors (40.9%) but present in <50% of cells in 19 (43.2%) and in >50% of cells in 7 (15.9%) tumors. Figure 1 shows a spindle cell (A) and an epithelioid uveal melanoma (B) and two representative positive stainings of uveal melanomas (C, D). A negative case and a negative control (see “Methods”) are also shown (Fig. 1e, f). When present, CXCR4 immunohistochemical staining was observed mainly in cytoplasm and plasmatic membrane (Fig. 1a); rarely only positive plasmatic membrane was observed (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Spindle cell uveal melanoma, 40× HE; b Epithelioid uveal melanoma, 40× HE; c High CXCR4 expression in uveal melanoma: big arrow indicates membrane staining and small arrow indicates cytoplasm staining, 63×; d low CXCR4 expression in uveal melanoma: arrow indicates membrane staining, 63×; e negative staining for CXCR4: note positive inflammatory cells, 63×; f Negative control

CXCR4 expression correlated with the epithelioid cell type

The overexpression of CXCR4 was found to be inversely related to the spindle A/B tumors with good prognosis (P = 0.03). CXCR4 expression was negative in 8 non-epithelioid tumors (42.1%) and present in <50% of cells in 11 (57.9%); none of the non-epithelioid tumors showed staining of CXCR4 in >50% of cells. CXCR4 was negative in 10 epithelioid tumors (40.0%) but positive in <50% of cells in 8 (32.0%) and in >50% of cells in 7 (28.0%) epithelioid tumors. No statistically significant relation emerged among CXCR4 expression classes, gender, age and LTD (Table 3). Neither vascularization, as evaluated through histological patterns stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), correlated to the CXCR4 expression (data not shown).

Table 3.

Associations between CXCR4 expression and clinico-pathological characteristics

| CXCR4 expression | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | ++ | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 7 | 9 | 5 | |

| Female | 11 | 10 | 2 | 0.167 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤65 | 10 | 12 | 2 | |

| >65 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 0.223 |

| Diameter | ||||

| <1 | 10 | 5 | 4 | |

| 1–1.5 | 4 | 12 | 2 | |

| >1.5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0.164 |

| Unknown | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Histology | ||||

| Non-epithelioid | 8 | 11 | 0 | |

| Epithelioid | 10 | 8 | 7 | 0.030 |

CXCR4 expression: correlation with outcome

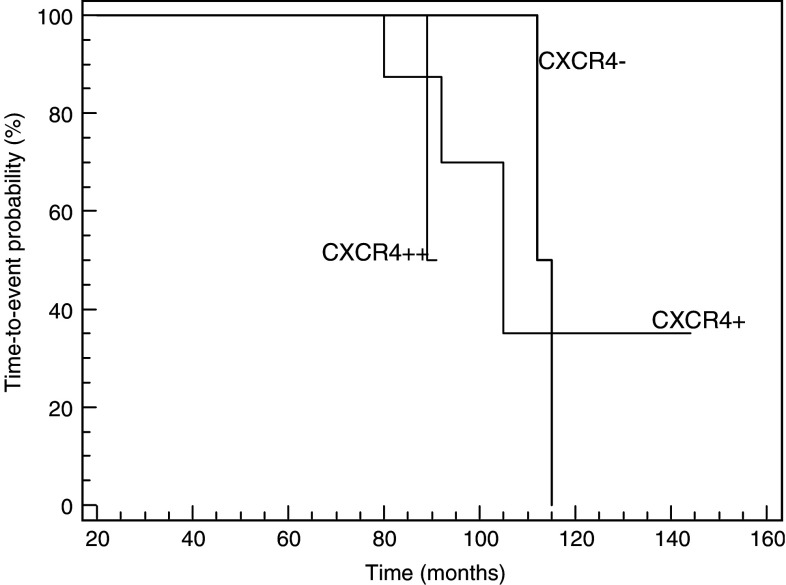

At the time of this analysis, after a median follow-up for live patients of 68 months, 4 patients died (2/4 patients expressing CXCR4), and 2 developed metastases (2/2 expressing CXCR4). The events occurred in 2 out of 18 patients (11.1%) with negative tumors (2 deaths), in 3 out of 19 patients (15.8%) with <50% of positive tumor cells (2 deaths and 1 occurrence of metastases) and in 1 out of 7 patients (14.3%) with >50% of positive tumor cells (1 occurrence of metastases). Univariate analysis of prognostic factors for time-to-event is summarized in Table 4. Out of the evaluated parameters diameter and CXCR4 did not show significant prognostic value. The cell type (non-epithelioid versus epithelioid; P = 0.0457) confirmed a prognostic meaning at the univariate analysis. Time-to-event Kaplan–Meier curves according to CXCR4 expression are shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Univariate analysis for time-to-event

| Events/patients | HR | CI | P (log-rank test) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 2/21 | |||

| Female | 4/23 | 1.07 | 0.14–8.42 | 0.925 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤65 | 4/24 | |||

| >65 | 2/20 | 1.58 | 0.32–7.61 | 0.565 |

| Diameter | ||||

| <1 | 3/19 | |||

| 1–1.5 | 3/18 | |||

| >1.5 | 0/6 | |||

| Unknown | 0/1 | NV | NV | 0.260 |

| Histology | ||||

| Non-epithelioid | 0/19 | |||

| Epithelioid | 6/25 | 0.87 | 0.03–0.96 | 0.0457 |

| CXCR4 expression | ||||

| − | 2/18 | |||

| + | 3/19 | |||

| ++ | 1/7 | 0.73 | 0.16–3.28 | 0.345 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, NV not valuable (i.e., sample size, median survival time, number of events do not allow calculation of HR and CI)

Fig. 2.

Time-to-event Kaplan–Meier curves according to CXCR4 expression

Discussion

CXCR4, a chemokine receptor for the specific ligand CXCL12, is expressed in uveal melanoma as assessed by the immunohistochemical detection of the receptor in 26 out of 44 uveal melanoma. The 26 positive cases were divided into two score classes according to their staining: <50% of tumor cells in 19 cases (43.2%) and >50% of tumor cells in 7 cases (15.9%). The CXCR4 expression correlated to the epithelioid/spindle B melanomas, a subgroup with poor clinical outcome. Noteworthy, all the seven cases with high expression of CXCR4 protein (>50% of tumor cells) were epithelioid uveal melanomas.

We previously demonstrated a prognostic role of CXCR4 in cutaneous melanoma. Patients expressing CXCR4 had a worse prognosis in term of disease free and overall survival [19]. The importance of CXCR4 in the biology of melanoma was then confirmed in human melanoma metastases. CXCR4 was detectable and functional in 52.4% of patients and in human melanoma cell lines [18]. Chemokines and their receptors have emerged as attractive targets regulating the migration of tumor cells in vivo. Chemokine receptors were detected on several cancers and cancer cell lines and the interaction between chemokines and their receptors induce cytoskeletal rearrangement of hematopoietic cell, increase their adhesion and direct them to migrate to a home specific organ. The same mechanisms were demonstrated to be involved in cell growth, survival and metastasis in neoplastic cells.

This study was aimed to evaluate if CXCR4 plays a role in uveal melanoma. Uveal melanoma is defined to be biologically and clinically different from cutaneous melanoma; in uveal melanoma metastatic disease usually occurs from 2 to more than 10 years [4–6] after ocular treatment until a massive tumor burden resistant to therapy suddenly appears causing death within 5–9 months. Therefore uveal melanoma is an ideal tumor for studying the mechanisms of distant metastasis and the efficacy of treating high-risk patients prophylactically for metastatic disease. However this strategy requires an accurate method for identifying high-risk patients.

CXCR4 is expressed in uveal melanoma and correlated with the epithelioid phenotype, which is strongly associated with a poor prognosis [3]. Another established prognostic factor is the ‘‘looping’’ patterns of extracellular matrix associated with metastatic death [9], which did not show to correlate with CXCR4 or to prognosis. It may be thus very helpful to identify prognostic factors in uveal melanoma. In this manuscript the relative small number of patients, the short follow-up and the related small numbers of events occurred could underestimate the CXCR4 prognostic meaning. CXCR4 expression was detected in 43.6% of primary cutaneous melanoma with a prognostic meaning on disease free survival and overall survival [19]; in uveal melanoma we detected CXCR4 expression in a percentage of patients (59.1%) comparable to the percentage registered in primary and metastatic cutaneous melanoma and a significant correlation with the histology, a strong prognostic factor. In addition we are currently evaluating the expression of other chemokine receptors described in primary melanoma such as CCR7 and CCR10 to identify a possible finger print of chemokine receptors for uveal melanoma.

This study shows that CXCR4 is commonly expressed in uveal melanoma and correlates with cell type, a well-established prognostic factor. Further studies are warranted to address its prognostic value.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from AIRC (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro).

References

- 1.Harbour JW. Clinical overview of uveal melanoma: introduction to tumors of the eye. In: Albert DM, Polans A, editors. Ocular oncology. Marcel Dekker: New York; 2003. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmittel A, Bechrakis NE, Martus P, Mutlu D. Independent prognostic factors or distant metastases and survival in patients with primary uveal melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2004;16:2389–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Callender GR Malignant melanotic tumors of the eye: a study of histologic types in 111 cases. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1931;36:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman LE, McLean IW, Foster WD. Does enucleation of the eye containing a malignant melanoma prevent or accelerate the dissemination of tumour cells. Br J Ophthalmol. 1978;62:420–425. doi: 10.1136/bjo.62.6.420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman LE, McLean IW. An evaluation of enucleation in the management of uveal melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87:741–760. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(79)90348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLean IW, Zimmerman LE, Foster WD. Survival rates after enucleation of eyes with malignant melanoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;88:794–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prescher G, Bornfeld N, Hirche H. Prognostic implications of monosomy 3 in uveal melanoma. Lancet. 1996;347:1222–1225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tschentscher F, Husing J, Holter T. Tumor classification based on gene expression profiling shows that uveal melanomas with and without monosomy 3 represent two distinct entities. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2578–2584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folberg R, Pe’er J, Gruman LM. The morphologic characteristics of tumor blood vessels as a marker of tumor progression in primary human uveal melanoma: a matched case-control study. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:1298–1305. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90299-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onken MD, Worley LA, Ehlers JP, Harbour JW. Gene expression profiling in uveal melanoma reveals two molecular classes and predicts metastatic death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7205–7209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy PM Chemokines and the molecular basis of cancer metastasis. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:833–835. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200109133451113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burger JA, Kipps TJ. CXCR4: a key receptor in the crosstalk between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Blood. 2006;107:1761–1767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robledo MM, Bartolome RA, Longo N. Expression of functional chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CXCR4 on human melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45098–45105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawada K, Sonoshita M, Sakashita H. Pivotal role of CXCR3 in melanoma cell metastasis to lymph nodes. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4010–4017. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiley HE, Gonzalez EB, Maki W. Expression of CC chemokine receptor-7 and regional lymph node metastasis of B16 murine melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1638–1643. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.21.1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeuchi H, Fujimoto A, Tanaka M. CCL21 chemokine regulates chemokine receptor CCR7 bearing malignant melanoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2351–2358. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scala S, Giuliano P, Ascierto PA. Human melanoma metastases express functional CXCR4. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2427–2433. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scala S, Ottaiano A, Ascierto PA. Expression of CXCR4 predicts poor prognosis in patients with malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1835–1841. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami T, Maki W, Cardones AR. Expression of CXC chemokine receptor-4 enhances the pulmonary metastatic potential of murine B16 melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7328–7334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moulin AP, Yan P, Rimoldi D (2006) Expression of chemokine receptors in uveal melanoma. Annual meeting of the association for research in vision and ophthalmology, 2006, abstract no. 2215/B958