Abstract

Innate and adaptive immune responses have many interactions that are regulated by the balance of signals initiated by a variety of activatory and inhibitory receptors. Among these, the NKG2D molecule was identified as expressed by T lymphocytes, including most CD8+ cells and a minority of CD4+ cells, designated TNK cells in this paper. Tumor cells may overexpress the stress-inducible NKG2D ligands (NKG2DLs: MICA/B, ULBPs) and the NKG2D signaling has been shown to be involved in lymphocyte-mediated anti-tumor activity. Aberrant expression of NKG2DLs by cancer cells, such as the release of soluble form of NKG2DLs, can lead to the impairment of these immune responses. Here, we discuss the significance of NKG2D in TNK-mediated anti-tumor activity. Our studies demonstrate that NKG2D+ T cells (TNK) are commonly recruited at the tumor site in melanoma patients where they may exert anti-tumor activity by engaging both TCR and NKG2D. Moreover, NKG2D and TCR triggering was also observed by peripheral blood derived T lymphocyte- or T cell clone-mediated tumor recognition, both in melanoma and colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. Notably, heterogeneous expression of NKG2DLs was found in melanoma and CRC cells, with a decrease of these molecules along with tumor progression. Therefore, through the mechanisms that govern NKG2D engagement in anti-tumor activity and the expression of NKG2DLs by tumor cells that still need to be dissected, we showed that NKG2D expressing TNK cells are a relevant T cell subtype for immunosurveillance of tumors and we propose that new immunotherapeutic interventions for cancer patients should be aimed also at enhancing NKG2DLs expression by tumor cells.

Keywords: TNK, NKG2D, Tumors, Immune responses

Introducton

Among the different immune cells involved in the control of human tumors, T cells appear to have a dominant role as suggested by animal studies and, more importantly, by findings of correlation between the function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL; T effectors vs. T regulatory) and prognosis in different types of tumors [1, 11, 13, 22, 43, 46, 55]. A convincing evidence of the defensive role of the immune system against tumors comes also from the studies in which the interaction among T, B and NKT lymphocytes has been examined in different murine models [17, 50] and found to be based on the three steps of eradication, equilibrium and escape [17]. Whether these conclusions are applicable also to the human system is not clear, owing to the lack or paucity of clinical studies where the interaction of these immune effectors and their individual role could be assessed.

Among different immune cells, invariant (i) NKT cells (iNKT) are characterized by an invariant TCR mainly composed of Vα24-Jα14 that recognizes glycolipid-type of tumor antigens within the restriction of CD1d, a HLA-like molecule [6, 26]. When stimulated by the appropriate, though not physiological, ligand (e.g., α-galactosyl-ceramide, α-GalCer) or by physiological molecules deriving from bacteria (e.g., iso-globo-trihexosylceramide, CpG), these iNKT cells can lyse tumors expressing CD1d-restricted molecules, such as in the case of glioblastoma [14]. These cells, therefore, have been tested as therapeutic anti-cancer tools in mice and humans administered either with iNKT cells or with their cognate ligands like α-GalCer. While such a treatment resulted in an efficient anti-tumor activity in animal models [4, 12], no significant therapeutic effects were found in cancer patients given α-GalCer [24] despite expansion of iNKT cells in vivo [9, 12]. iNKT lymphocytes, by modulating the function of other immune cells like dendritic cells (DCs), can also influence the early phase of the immune response. T cells may benefit from the help of the NKT cell [48]. These conflicting results could be explained by the recent discovery of the existence of two types of iNKT cells (type I and II), one of which is endowed with suppressive immune activity [2].

The other subset of lymphocytes that display features of T and NK cells have been defined as TNK since they are T cells, including most of CD8+ and a minority of CD4+ T cells, bearing a regular, polymorphic αβ TCR while expressing also inhibitory and stimulatory NK receptors [5, 31]. Ectopic expression of NKG2D ligands causes rejection of tumor cells by NK and cytotoxic (CTL) T cells in syngeneic mice [8, 15], showing the relevance of NKG2D signaling in immunosurveillance against tumors. Moreover, evidences that NKG2D can mediate anti-tumor activity by T lymphocytes isolated from cancer patients have been obtained [19, 27, 37, 38], highlightening the need to dissect the mechanisms that regulate the NKG2D signaling. The present paper will focus on the characterization of this second type of immune effectors, hereafter defined as TNK.

TNK and their role in the immune response against human tumors

Melanoma

Recent findings indicate that the T cell-mediated immune reaction against tumors in the host may result not only from the recognition of MHC-restricted tumor associated antigen (TAA)-derived peptide complexes, but also from the engagement of NKG2D receptor by stress-induced ligands expressed by tumor cells [27, 28, 58]. However, the mechanisms that govern the different pathways, mediated by activatory, co-stimulatory or inhibitory receptors, involved in the immune-mediated recognition of tumor cell, still need to be dissected. The evidence that both TNK and αβNKT-like (CD3+CD56+) cells infiltrating the tumor (TILs) expressed NKG2D suggested that this receptor can be engaged in the immune response against melanoma, though the effector function of these cells was not assessed [57].

Along this line, our group investigated whether NKG2D can mediate the recognition of melanoma cells by antigen-specifc α/βT lymphocytes. Interestingly, we found that NKG2D expression was associated with CD3+TCR α/β+ TILs and that these cells commonly infiltrated either the periphery or within the tumor mass of primary and metastatic melanoma lesions [38], indicating that indeed NKG2D expressing T lymphocytes are recruited at the tumor site and thus can play an active role in vivo in the immune response against melanoma. This hypothesis was confirmed by the demonstration that freshly isolated TILs from melanoma patients exerted in vitro anti-tumor activity, as evaluated by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay, against the autologous melanoma by engagement of both NKG2D and TCR (Table 1) [38]. In addition, NKG2D expression and engagement, together with TCR, in anti-tumor activity was found in in vitro isolated antigen-specific and MHC-restricted T cell clones derived from these TILs (Table 2) [38]. Of note, NKG2D expression was commonly found in association with the CD8+ T subset, while NKG2D+CD4+ T cells were represented with low frequency among TILs or PBMCs of melanoma patients, as previously reported [5, 52]. An additional demonstration of the relevance of NKG2D in anti-melanoma T cell-mediated immune response was suggested by the observation that lymphocytes from a tumor-invaded lymph node of a melanoma patient, showing oligoclonal specificity for the TAA gp100 [7], secreted specifically IFN-γ upon engagement of both NKG2D and TCR following in vitro stimulation with the autologous tumor (Table 1) [38]. These results are in line with the evidence that in sentinel lymph nodes of melanoma patients the presence of antigen-specific T cells expressing NKG2D and of mature DCs stained for NKG2D ligand (NKG2DLs) could be detected [47], suggesting a relevant function of NKG2D signaling for the induction of tumor-specific T cell responses.

Table 1.

Expression of NKG2D and its engagement in anti-tumor reactivity by TILs or PBMCs isolated from melanoma patients

| T cells | Markera | Receptor engagement in autologous tumor reactivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | CD8 | CD4/NKG2D | CD8/NKG2D | ||

| TILs pt. 7 | ± | + | − | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| TILs pt. 9 | + | + | ± | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| TILs pt.10 | + | + | ± | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| TILNs pt. 15392 | ± | + | − | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| PBMCs pt. 15392 | + | + | − | + | TCR and NKG2D |

TILNs, lymphocytes isolated from tumor invaded lymph node

aExpression of T cell specific markers was evaluated by immunofluorescence and cytofluorimetric analysis. Results are defined as positive (+), weakly positive (±) or negative

Table 2.

NKG2D involvement in tumor recognition by T cell clones isolated from melanoma and CRC patients

| T cell clone | Origin | Patient # | TAAa | Markerb | Receptor engagement in autologous tumor reactivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 | CD8 | NKG2D | |||||

| Melanoma | |||||||

| B1 | TILs | 7 | Unknown | − | + | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| A1 | TILs | 7 | Unknown | + | − | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| TB254 | TILNs | 15392 | gp 10071–78 | − | + | + | TCR |

| D4F12 | TILs | 1200 | gp 100209–217 | − | + | + | TCR |

| G4G10 | TILs | 888 | β-Cat29–37mut | − | + | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| A42 | TILs | 501 | MART-127–35 | − | + | ± | TCR |

| TB515 | TILNs | 15392 | PTPRK667–682 | + | − | − | TCR |

| CRC | |||||||

| M21 | PBMCs | 1869 | Unknown | − | + | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| M23 | PBMCs | 1869 | Unknown | − | + | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| M26 | PBMCs | 1869 | Unknown | + | − | − | TCR |

| M51 | PBMCs | 1869 | Unknown | − | + | + | TCR and NKG2D |

| M83 | PBMCs | 1869 | Unknown | − | + | + | TCR |

| C111 | PBMCs | 1869 | COA-1441–460 | + | − | + | TCR and NKG2D |

TILNs, lymphocytes isolated from tumor-invaded lymph node

aTAAs recognized by T cell clones isolated from melanoma and CRC patients

bExpression of T cell specific markers was evaluated by immunofluorescence and cytofluorimetric analysis. Results are defined as positive (+), weakly positive (±) or negative

Notably, heterogeneous usage of this receptor occurred even with long-term in vitro established specific T cell clones recognizing melanoma-associated antigens. In fact, autologous tumor recognition was independent of NKG2D engagement for two gp100-specific and one Melan-A/MART-1-specific T cell clones, while the reactivity against melanoma cells of a β-catenin-specific CD8+ T cell clone was elicited by activation of both TCR and NKG2D (Table 2) [38].

These data highlight the complexity in the regulation of the engagement of NKG2D in anti-tumor activity, suggesting that the activation state of lymphocytes or the affinity/avidity of TCR for the MHC/peptide complexes could affect the role of multiple receptors and indicate whether or not to engage co-stimulatoy receptors, such as NKG2D, in the anti-tumor immune responses. Recent studies demonstrated that NK cell activity against tumors could be strengthened by HSP70 or a combination of stimulatory signaling involving NKG2D plus cytokine and TLR agonists [20, 25]. Therefore, further investigations are needed to dissect the mechanism that govern multiple activatory signal in T or TNK cells to elicit efficient anti-tumor immune responses.

The expression of the stress-inducible NKG2DLs (MICA/B and ULBPs) has been extensively described in a range of epithelial and other malignancies, including melanoma, [27, 28, 57], rendering cancer cells as attractive target for NK, T and TNK cells through NKG2D activation. Our analysis of the expression of NKG2DLs by melanoma cells showed that the in vivo expression of these molecules was heterogeneous. In fact, metastatic melanoma lesions stained either for a single or two different NKG2DLs, while only the primary lesion expressed significant level of all the analyzed molecules [38]. In addition, only ULBP2 molecule was homogeneously and highly expressed by most melanoma cells within tumor lesions [38]. These data suggest that expression of NKG2DLs by melanoma cells can decrease along with tumor progression. These evidences are in line with previous studies demonstrating that soluble forms of NKG2DLs were detected in the blood of cancer patients and can be released by tumor cells [29, 32, 45, 63], correlating, in some cases, with the prognosis of the disease [32, 45]. NKG2D expression down-modulation by tumor cells has been documented as the result of the activity of proteolytic cleavage or of growth factor, such as TGF-β1, produced by cancer cells [36]. This could represent a mechanism of tumor evasion from immunosurveillance by T lymphocytes or NK cells [34]. In fact, soluble NKG2DLs can down modulate the expression of the activatory receptor onto lymphocytes, leading to the impairment of the anti-tumor immune responses [16, 29, 63]. Furthermore, impairment of cytotoxic activity by NK cells with reduced level of NKG2D has been detected in metastatic melanoma [34]. Recent publications also showed that in melanoma down-modulation of NKG2D by tumor-derived exosomes can occur [10] and, moreover, intracellular retention of NKG2DLs by melanoma cells can confer immune privilege [21].

Along this line, relatively little is known about the factors that can regulate the expression of NKG2DLs by tumor cells; the expression of these ligands in tumor cells harboring genomic aberrations may be due to chronic activation of DNA damage response pathway [23]. A significant diversity in promoter regions of NKG2DL genes that can lead to differential regulation of the expression of these molecules by cells has been documented [15, 18]. In addition, treatment of cancer with some agents, such as histone deacetylase, DNA methyltransferase or protease inhibitors, has been described as a strategy leading to up-regulation of NKG2DLs by tumor cells [3, 54, 56]. Further investigation of this issue should be undertaken to determine the mechanism and the factors that can regulate the expression of these molecules by cancer cells. This information may allow designing chemotherapy plus immunotherapy studies that can lead to efficient antigen expression by tumor cells and to the simultaneous elicitation of an efficacious systemic anti-tumor immune response in cancer patients.

Taken together, the findings discussed in this paragraph highlight that NKG2D+ T cells represent a lymphocyte subset exerting anti-melanoma activity. Thus, though we still need to further dissect the complexity that governs the engagement of multiple stimulatory receptors, as well as the mechanisms that can lead to the expression of NKG2DLs by tumor cells, new immunotherapeutic interventions for melanoma patients should consider the option of augmenting and sustaining the NKG2D+ T lymphocyte-mediated immune response [59].

Colorectal cancer

NKG2DLs have a restricted normal tissue distribution in intestinal epithelium but are over-expressed by epithelial tumors, particularly by colorectal cancer (CRC) [27, 28] and could represent target molecules eliciting efficient anti-CRC immune responses. However, NKG2DL-expressing tumors rapidly progress and develop metastasis, implying that NKG2D signaling is irrelevant or impaired in tumor patients. We investigated the expression of NKG2DLs in a panel of CRC lines, including some fresh in vitro established ones, and found a variable CRC cell surface expression of MICA and ULBP2/3 with a minority of cell lines being also ULBP-1+, whereas MICB was undetectable [37]. Thus, we could conclude that heterogeneous expression of NKG2DLs occurred in CRC cell lines, suggesting the existence of a post-translational regulation of NKG2D ligand in these cells, resembling a mechanism of tumor immune escape as discussed in the previous section. Recent published data confirmed that CRC expressed heterogeneously NKG2DLs [44] and, in addition, that the expression of one of these molecules (MICA) represents a marker of good prognosis of the disease [61]. Therefore, NKG2D signaling can play a relevant role in eliciting anti-tumor immune response in CRC patients; however, the efficiency in the expression of NKG2DLs by tumor cells can affect the resulting effectiveness of the specific immune response. A support for this hypothesis was obtained from the study we performed to evaluate the role of NKG2D in anti-CRC response of tumor-specific T cells [37]. We found that in CRC-specific CD8+ T cell clones, NKG2D mediated the autologous tumor recognition together with TCR, though the reactivity directed at the autologous tumor cells was less affected by blocking with anti-NKG2D mAb than by blocking with anti-TCR or anti-HLA class I mAb. This result correlated with the low availability of NKG2D ligands on the surface of autologous CRC cells, a factor that influences the efficiency of the engagement of NKG2D. Whereas, the reactivity against allogeneic CRCs by these clones was dependent on NKG2D stimulation and on significant levels of expression of MICA and ULBPs by tumor cells [37]. These evidences demonstrated that efficient engagement of NKG2D is strictly dependent on the level of NKG2DLs on the surface of tumor cells and that the recognition of tumor cells by some effectors can be mediated by both TCR and NKG2D, or by only one of these receptors (Table 2). Notably, the analysis of the reactivity of one antigen-specific CD4+ T cell clone, isolated from the peripheral blood of a CRC patient, showed that NKG2D could deliver a co-stimulatory signal together with the requirement of the TCR-mediated stimulation (Table 2) [37]. Thus, also for CD4+ T cells, as shown in the case of melanoma [38], tumor reactivity can be achieved by the delivery of co-stimulatory signal by NKG2D. Though NKG2D+ CD4+ T cells are rare among human T cells, these subset of lymphocytes can play a relevant role in immunosurveillance of tumors.

Of note, NKG2D triggering by human intestinal intraepithelial CD8+T lymphocytes, which show spontaneous cytotoxic activity against epithelial tumors, can lead to FasL-mediated killing of CRC cells, indicating that NKG2D signaling can mediate the in vivo cytotoxic activity by the T cell against CRC [19].

TNK in other human tumors

Several studies have shown that tumor infiltrating and PBMC-derived NK or CD3+ CD56+ “NKT-like” cells display a diminishing number and a compromised functionality also in other human tumors such as breast, prostate and gastric cancer [39, 42, 62]. Responsiveness of these cells correlate with a down-modulation in the expression of NKG2D receptors, which has been demonstrated to be induced by a sustained and prolonged exposure to NKG2DLs constitutively expressed and frequently up-regulated on breast, lung, gastric, renal, ovarian and prostate carcinomas [27, 42, 62, 63]. This may also be due to the trans-acting effect of soluble forms of MICs and ULBPs ligand cleaved by a tumor-associated metalloprotease inducing the endocytosis and degradation of NKG2D. Presence of elevate soluble MICA and MICB levels were found in the serum of solid tumors and leukemic patients [32, 45, 62]. Moreover, a linear correlation between MICs serum level and the diseases progression was demonstrated in ovarian and prostate cancers [60, 63]. Notably, though no difference in soluble MICA between gastric cancer patients and normal controls occurred, reduced NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells was found in tissue with gastric cancer; this down-regulation was induced by direct contact between cancer cells and T cells and soluble factors did not affect NKG2D expression. Therefore, NKG2D down-modulation may represent one of the key mechanisms responsible for immune evasion by tumors and this phenomenon may be mediated by a variety of mechanisms [42]. Other mechanisms for tumors to escape from the NKG2D-mediated immune surveillance could be mediated by different cytokines produced by the tumor itself. An over-expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and the production of TGF-β1 transcriptionally down-regulated NKG2D, impairing NK cell cytotoxicity in ovarian cancer and lung cancer, respectively [35, 36].

iNKT cells versus TNK

The immune defense against tumors is mediated early by the innate immune system (DCs, NK, iNKT cells) and later on by the adaptive immune system (B and T cells). However, there are many interactions between the innate and the adaptive immune system. In fact, innate immune cells, such as DCs, are required for Ag presentation to activate naïve or memory-adaptive populations, and cytokines secreted by innate cells may influence the activity of adaptive responders. Along this line, iNKT cells represent a bridge between the innate and adaptive immune system [2, 6, 26], since these cells can play a regulatory role, representing the major determinant early in the immune response and in the subsequent skewing of the adaptive responses against tumor cells. Notably, increased intratumor type I NKT cells correlating with longer overall and disease-free survival rates was found in CRC patients [53]. Moreover, the administration of a-GalCer plus IL-18 in a mouse melanoma model led to the suppression of metastasis by iNKT-mediated stimulation of NK anti-tumor activity, indicating a relevant role for NKT cells in anti-tumor activity [41]. Interestingly, the NKG2D receptor that plays an activatory/co-stimulatory role in T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity is expressed constitutively by NKT and NK cells. Therefore, as we have shown for T cell-mediated recognition of human melanoma and colorectal cancer, the efficiency of the expression of NKG2DLs by tumor cells can affect also NK [44] and NKT cell stimulation and the subsequent cross talk between innate and adaptive immunity. Since NKG2D signaling can mediate the activation of lymphocyte populations of a variety of subsets (TNK, NK, NKT, NKT-like cells), it may play a relevant role in the cross talk between all these lymphocyte populations. Indeed, the mechanisms that govern the activation of NKG2D and its interactions with other activatory receptors should be dissected in future studies. Of note, a recent publication showed unexpectedly that DAP10, a transmembrane adaptor protein that associates with NKG2D in a multi-subunit receptor complex, can activate Tregs to maintain tolerance against tumors by the resulting dampening of NKT and NK functions [33]. Therefore, it will also be important to assess the relationship between the regulatory and activatory pathway involved in tumor immunosurveillance. This information will allow to determine which lymphocyte population dominates in any given settings. A variety of studies have demonstrated the important role of NKG2D signaling for cancer immunosurveillance. In fact, ectopic expression of NKG2D ligands causes rejection of tumor cells expressing NKG2DLs by NK and cytotoxic T cells in syngeneic mice [8, 15]. Furthermore, this receptor can also mediate an anti-tumor activity by lymphocytes isolated from cancer patients [19, 27, 30 37, 38, 50, 51].

Thus, the activation of cellular immune response against cancer cells and the subsequent protection of the host against tumor depend on the optimal combination of activatory and regulatory signals on lymphocytes. In this scenario, NKG2D represents the “bridge molecule” that can affect the efficiency of the cross talk between a variety of lymphocyte subsets.

Conclusion

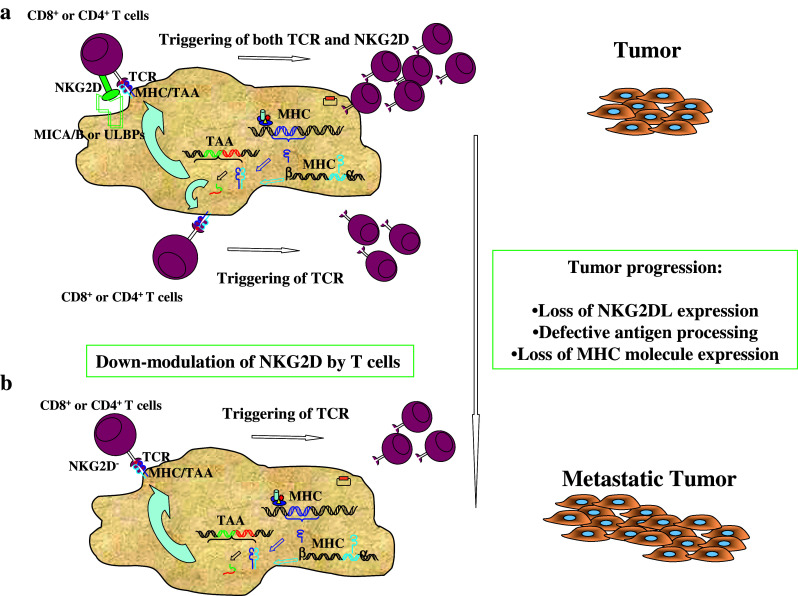

In conclusion, though the role of NKG2D in mediating anti-tumor activity by T cells should be further dissected in cancer patients in relation to tumor progression, evidence has been obtained that TNK are relevant for anti-tumor activity. However, tumor escape mechanisms may lead to down-modulation and secretion of the soluble form of NKG2DLs, resulting, particularly in late-stage tumor patients, in the impairment of NKG2D stimulation of TNK, NK or NKT-like cells (Fig. 1) [16, 59, 62, 64]. Future studies should be focused to determine the role of NKG2D triggering in in vivo anti-tumor response by different lymphocyte subpopulations (TNK, NK and NKT-like) from TILs and PBMCs of cancer patients. Moreover, mechanisms that can increase the immunogenicity of tumor cells, such as augmenting the expression of their ligands for NK, NKT and TNK cells, should be studied further.

Fig. 1.

Role of NKG2D in anti-tumor immunosurveillance. a Triggering of both TCR and NKG2D by MHC/peptide complexes and MIC/ULBP molecules expressed by tumor cells, respectively, can elicit efficient TNK cell-mediated anti-tumor recognition and can lead to the eradication of tumors. b Along with tumor progression, immune evasion mechanisms lead to the failure of expression by tumor cells of NKG2D ligands and/or of some MHC/peptide complexes and by TNK cells of NKG2D receptor, resulting in the impairment of anti-tumor immune recognition. NKG2DLs, NKG2D ligands (MICA/MICB, ULBPs); TAA tumor-associated antigen; MHC/TAA, MHC tumor-associated antigen–peptide complexes

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues Drs. C. Castelli, D. Nonaka, A. Piris, L. Rivoltini (Istituto Nazionale Tumori, Milan), P. F. Robbins (Surgery Branch, NCI, NIH, Bethesda), D. Cosman (Amgen, Seattle), M. C. Mingari, D. Pende (Istituto Tumori Genoa), C. Doglioni, and L. Pilla (San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan) for their valuable collaboration in performing the studies, the results of which are summarized in this work. The authors’ work was supported by AIRC (Italian Association for Research on Cancer, Milan) and the Italian Ministry of Health, Rome.

References

- 1.Alvaro T, Lejeune M, Salvadò MT, et al. Outcome in Hodgkin’s lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1467. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambrosino E, Terabe M, Halder RC, et al. Cross-regulation between type I and type II NKT cells in regulating tumor immunity: a new immunoregulatory axis. J Immunol. 2007;179:5126. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen L, Jensen H, Pedersen MT, Hansen KA, Skov S. Molecular regulation of MHC class I-related chain A expression after HDAC-inhibitor treatment of Jurkat T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:8235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxevanis CN, Gritzapis AD, Papamichail M. In vivo antitumor activity of NKT cells activated by the combination of IL-12 and IL-18. J Immunol. 2003;171:2953. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, et al. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berzowsky JA, Terabe M. A novel immunoregulatory axis of NKT cell subset: regulating tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:1679. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castelli C, Tarsini P, Mazzocchi A, et al. Novel HLA-Cw8-restricted T cell epitopes derived from tyrosinase-related protein-2 and gp100 melanoma antigens. J Immunol. 1999;162:1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cerwenka A, Baron JL, Lanier LL. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible-1 gene (RAE-1) permits natural killer cell-mediated rejection of a MHC class I-bearing tumor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201238598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang DH, Osman K, Connolly J, et al. Sustained expansion of NKT cells and antigen-specific T cells after injection of α-galactosyl ceramide loaded mature dendritic cells in cancer patients. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clayton A, Mitchell JP, Court J, Linnane S, Mason MD, Tabi Z. Human tumor-derived exosomes down-modulate NKG2D expression. J Immunol. 2008;180:7249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemente C, Mihm MC, Bufalino R, Zurrida S, Collini P, Cascinelli N. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crowe NY, Coquet JM, Berzins SP, et al. Differential antitumor immunity mediated by NKT cell subsets in vivo. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1279. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nature Med. 2004;10:942. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhodapkar KM, Cirignano B, Chamian F, et al. Invariant natural killer T cells are preserved in patients with glioma and exhibit antitumor lytic activity following dendritic cell-mediated expansion. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:893. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diefenbach A, Jensen ER, Jamieson AM, Raulet DH. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumor immunity. Nature. 2001;413:165. doi: 10.1038/35093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doubrovina ES, Doubrovin MM, Vider E, et al. Evasion from NK cell immunity by MHC class I chain-related molecules expressing colon adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2003;171:6891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber R. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Ann Rev Immunol. 2004;22:329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagle RA, Traherne JA, Ashiru O, Wills MR, Trowsdale J. Regulation of NKG2D ligand gene expression. Human Immunol. 2006;67:159. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebert EC, Groh V. Dissection of spontaneous cytotoxicity by human intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes: MIC on colon cancer triggers NKG2D-mediated lysis through Fas ligand. Immunology. 2008;124:33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsner L, Muppala V, Gehrmann M, et al. The heat shock protein HSP70 promotes mouse NK cell activity against tumors that express inducible NKG2D ligands. J Immunol. 2007;179:5523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuertes MB, Girart MV, Molinero LL, et al. Intracellular retention of the NKG2D ligand MHC class I chain-related gene A in human melanoma confers immune privilege and prevents NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2008;180:4606. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436:1186. doi: 10.1038/nature03884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giaccone G, Punt CJ, Ando Y, et al. A phase I study of the natural killer T cell ligand α-galactosylceramide (KRN7000) in patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girart MV, Fuertes MB, Domaica CI, Rossi LE, Zwirner NW. Engagement of TLR3, TLR7, and NKG2D regulate IFN-γ secretion but not NKG2D-mediated cytotoxicity by human NK cells stimulated with suboptimal doses of IL-12. J Immunol. 2007;179:3472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzales S, Groh V, Spies T. Immunobiology of human NKG2D and its ligands. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;298:121. doi: 10.1007/3-540-27743-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived γδ T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Groh V, Wu J, Yee C, Spies T. Tumor-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 2002;419:734. doi: 10.1038/nature01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ. NKG2D and cytotoxic effector function in tumor immune surveillance. Semin Immunol. 2006;18:176. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houchins JP, Yabe T, McSherry C, Bach FH. DNA sequence analysis of NKG2, a family of related cDNA clones encoding type II integral membrane proteins on human natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1017. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holdenrieder S, Stieber P, Peterfi A, Nagel D, Steinle A, Salih RH. Soluble MICB in malignant diseases: analysis of diagnostic significance and correlation with soluble MICA. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1284. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0167-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyka-Nouspikel N, Lucian L, Murphy E, McClanahan T, Phillips JH. DAP10 deficiency breaks the immune tolerance against transplantable syngeneic melanoma. J Immunol. 2007;179:3763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konjevic G, Martinovic KM, Vuletic A, et al. Low expression of CD161 and NKG2D activating NK receptor is associated with impaired NK cell cytotoxicity in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24:1. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krockenberger M, Dombrowski Y, Weidler C, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor contributes to the immune escape of ovarian cancer by down-regulating NKG2D. J Immunol. 2008;180:7338. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JC, Lee K-M, Kim D-W, Heo DS. Elevated TGF-β1 secretion and down-modulation of NKG2D underlies impaired NK cytotoxicity in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2004;172:7335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maccalli C, Pende D, Castelli C, Mingari MC, Robbins PF, Parmiani G. NKG2D engagement of colorectal cancer-specific T cell strengthens TCR-mediated antigen stimulation and elicits TCR independent anti-tumor activity. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2033. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maccalli C, Nonaka D, Piris A, et al. NKG2D-mediated anti-tumor activity by TILs and antigen-specific T cell clones isolated from melanoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madjd Z, Spendlove I, Moss R, et al. Upregulation of MICA on high-grade invasive operable breast carcinoma. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno M, Molling JW, von Mensdorff-Pouilly S, et al. IFN-γ-producing human invariant NKT cells promote tumor-associated antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell responses. J Immunol. 2008;181:2446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishio S, Yamada N, Ohyama H, et al. Enhanced suppression of pulmonary metastasis of malignant melanoma cells by combined administration of α-galactosylceramide and interleukin-18. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:113. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osaki T, Saito H, Yoshikawa T, et al. Decreased NKG2D expression on CD8+ T cells is involved in immune evasion in patients with gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:382. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parmiani G. Tumor-infiltrating T cells: friends or foes of neoplastic cells? New Engl J Med. 2005;353:2640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pende D, Cantoni C, Rivera P, et al. Role of NKG2D in tumor cell lysis mediated by human NK cells: cooperation with natural cytotoxicity receptors and capability of recognizing tumor of nonepithelial origin. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1076. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1076::AID-IMMU1076>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salih HR, Antropius H, Gieseke F, et al. Functional expression and release of ligands for activating immunoreceptor NKG2D in leukaemia. Blood. 2003;102:1389. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J, et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favourable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schrama D, Terheyden P, Otto K, et al. Expression of the NKG2D ligand UL16 binding protein-1 (ULBP-1) on dendritic cells. E J Immunol. 2006;36:65. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimizu K, Kurosawa Y, Taniguchi M, Steinman RM, Fujii S-I. Cross-presentation of glycolipid from tumor cells loaded with α-galactosylceramide leads to potent and long-lived T cell-mediated immunity via dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2641. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silk JD, Hermans IF, Gileadi U, et al. Utilizing the adjuvant properties of CD1d-dependent NKT cells in T cell-mediated immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1800. doi: 10.1172/JCI22046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smyth MJ, Godfrey DJ, Trapani JA. A fresh look at tumor immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Nature Immunol. 2001;2:293. doi: 10.1038/86297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smyth MJ, et al. NKG2D recognition and perforin effector function mediate effective cytokine immunotherapy of cancer. J Exp Med. 2004;200(10):1325–1335. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Speiser DE, Valmori D, Rimoldi D, et al. CD28-negative cytolytic effector T cells frequently express NK receptors and are present at variable proportions in circulating lymphocytes from healthy donors and melanoma patients. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1990. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<1990::AID-IMMU1990>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tachibana T, Onodera H, Tsuruyama T, et al. Increased intratumor Vα-24-positive natural killer T cells: a prognostic factor for primary colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7322. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang K-F, He C-X, Zeng G-L, et al. Induction of MHC class I-related chain B (MICB) by 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 2008;370:578. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unitt E, Marshall A, Gelson W, et al. Tumour lymphocytic infiltrate and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2006;45:246. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vales-Gomez M, Chishlom SE, Cassady-Cain RL, Roda-navarro P, Reyburn HT. Selective induction of expression of a ligand for the NKG2D receptor by proteasome inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1546. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vetter CS, Groh V, thor Straten P, Spies T, Brocker E-B, Becker JC. Expression of stress-induced MHC class I related chain molecules on human melanomas. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:60. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Paul P. Lymphocyte activation via NKG2D: towards a new paradigm in immune recognition? Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:306. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(02)00337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang E, Selleri S, Marincola FM. The requirements for CTL-mediated rejection of cancer in human: NKG2D and its role in the immune responsiveness of melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang H, Yang D, Xu W, Wang Y, Ruan Z, Zhao T (2008) Tumor-derived soluble MICs impaired CD3+ CD56+ NKT-like cell cytotoxicity in cancer patient. Immunol Lett (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Watson NFS, Spendlove I, Madjd Z, et al. Expression of the stress-related MHC class I chain-related protein MICA is an indicator of good prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1445. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wiemann K, Mittrucker H-W, Feger U, Welte SA, Yokohama WM, Spies T. Tumor-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. J Immunol. 2005;175:720. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu JD, Higgins LM, Steinle A, Cosman D, Haugh K, Plymate SR. Prevalent expression of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related molecule is counteracted by shedding in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:560. doi: 10.1172/JCI22206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yokoyama WM. Catch us if you can. Nature. 2002;419:679. doi: 10.1038/419679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]