Abstract

Expression of ligands of the immunoreceptor NKG2D such as MICA and MICB has been proposed to play an important role in the immunosurveillance of tumors. Proteolytic shedding of NKG2D ligands from cancer cells therefore constitutes an immune escape mechanism impairing anti-tumor reactivity by NKG2D-bearing cytotoxic lymphocytes. Serum levels of sMICA have been shown to be of diagnostic significance in malignant diseases of various origins. Here, we investigated the potential of soluble MICB, the sister molecule of MICA, as a marker in cancer and its correlation with soluble MICA. Analysis of MICB in sera of 512 individuals revealed slightly higher MICB levels in patients with various malignancies (N = 296; 95th percentile 216 pg/ml; P = 0.069) than in healthy individuals (N = 62; 95th percentile 51 pg/ml). Patients with benign diseases (N = 154; 95th percentile 198 pg/ml) exhibited intermediate MICB levels. In cancer patients, elevated MICB levels correlated significantly with cancer stage and metastasis (P = 0.007 and 0.007, respectively). Between MICB and MICA levels, only a weak correlation was found (r = 0.24). Combination of both markers resulted only in a slightly higher diagnostic power in the high specificity range. The reduction of MICA and MICB surface expression on cells by shedding and the effects of sMICA and sMICB in serum on host lymphocyte NKG2D expression might play a role in late stages of tumor progression by overcoming the confining effect of NK cells and CD8 T cells. While MICB levels are not suited for the diagnosis of cancer in early stages, they may provide additional information for the staging of cancer disease.

Keywords: MICB, NKG2D, MICA, Serum, Cancer, Diagnosis

Introduction

Recent evidence indicates that the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D expressed on CD8 T cells and NK cells plays an important role in the immunosurveillance of tumors. NKG2D costimulates T cells and potently activates NK cells even overcoming inhibitory signals by MHC class I molecules [1, 2]. The NKG2D ligands (NKG2DL), MICA and MICB, have been shown to be induced by genotoxic stress which is associated with malignant transformation [3]. MIC molecules are also broadly expressed by epithelial and hematopoietic tumors, but not in healthy tissue [4, 5]. Several studies demonstrated that, NKG2DL-expression by tumor cells strongly stimulates anti-tumor immunity in mice, and that rejection of NKG2DL-expressing tumors is mediated by NK cells and/or CD8 T cells in vivo [6–9]. However, recent evidence suggests that there exist several immune escape mechanisms by which tumor cells evade NKG2D-mediated immunosurveillance. Besides down-regulation of NKG2D by TGF-β, a recently described putative inhibitory receptor for MICA expressed on proliferating T cells might counter NKG2D-mediated immunity [10–12]. We demonstrated recently that human tumor cells reduce NKG2DL surface levels by proteolytic shedding of MICA from the cell surface [13]. Since NKG2D-mediated immune responses are critically depending on NKG2DL surface levels [6], down-regulation of NKG2DL-expression levels by shedding is likely to promote the immune escape of tumor cells. In addition, soluble NKG2D ligands were also reported to cause systemic down-regulation of NKG2D surface expression thereby impairing lysis of tumor cells by human CD8 T cells [14]. However, since soluble NKG2DL can be detected in sera of patients with various malignancies [5, 13, 14] the question was raised whether soluble NKG2DL are of diagnostic value in patients with malignancies [15]. In a comprehensive study, we demonstrated very recently that sMICA levels are significantly elevated in cancer diseases compared with healthy controls as well as with benign diseases, and correlate with cancer stage and metastasis [16]. However, up to now it is not known whether soluble MICB can similarly be used as a tumor marker or add to the diagnostic value of MICA. We also were interested in sMICB analysis, since in contrast to MICA, the in vivo expression of MICB by epithelial tumors is largely unknown. Therefore, we here analyzed sMICB levels in sera of cancer patients and compared them with sMICB levels of patients with matched benign diseases and of healthy individuals. Furthermore, we correlated sMICB with tumor stage as well as with sMICA levels determined previously [16] to elucidate the potential diagnostic benefit of a combination of both markers.

Patients and methods

Patient sera

Serum samples were from 512 individuals including 62 healthy donors, 154 patients with benign diseases, and 296 patients with malignant tumors. The group with benign diseases included 72 patients with benign gastrointestinal disorders (adenoma, polyposis, colitis, Crohn’s disease, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, pancreatitis, cholecystolithiasis, and others), 37 with lung disorders (tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, allergic, autoimmune and infectious lung diseases, and others), 37 with gynecologic (ovarian cysts, endometriosis, uterus myomatosus, and others), and 8 with other benign diseases (nodular goiter, lipoma, and others). Serum samples were obtained at time of diagnosis or at acute stage of disease before start of the respective therapy, i.e., prior to surgery, anti-inflammatory or antibiotic treatment, etc.

The group with malignant diseases comprised 88 patients with colorectal cancers and 40 with other gastrointestinal cancers (esophageal, gastric, liver, and pancreatic cancers), 19 with lung cancers, 52 with breast cancers, 43 with ovarian cancers, 19 with other gynecologic cancers (cervical, endometrial, and vulva cancers), 19 with renal cancers, and 16 with prostate cancers. Serum samples from all cancer patients were obtained prior to surgery, which was the most frequent treatment modality, or before start of chemotherapy, or radiotherapy, respectively. The study was approved by the local Ethics committee.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Serum levels of sMICB were determined by our previously described sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [5]. In brief, plates were coated with the capture mAb BAMO1 at 5 μg/ml in PBS, then blocked by addition of 15% BSA, washed and incubated with the standard (recombinant sMICB*02 produced in Escherichia coli) or patient sera. Patient sera were diluted 1:3 in 7.5% BSA. Next, plates were washed, incubated with the detection mAb BMO2 at 1 μg/ml, washed again, and then incubated with anti-mouse IgG2a-HRP (1:8,000 dilution; Southern Biotechnologies, Birmingham, AL, USA). Finally, plates were washed and developed using the TMB Peroxidase Substrate System (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. We earlier reported that this MICB ELISA is highly specific and does not cross-react with MICA [5]. For comparison with sMICB, sMICA levels were determined in the same serum samples using ELISA as described in reference [16].

Statistical analysis

Sera of cancer patients were compared with sera of healthy persons and patients suffering from non-malignant diseases, respectively. For the general comparison of two groups, statistical calculations were performed by Wilcoxon test. Distribution of concentrations across the categories of an ordered variable, as stage and grade, were tested for an upward trend using ANOVA on ranks of values.

To assess the diagnostic potential of the assay, cutoffs were chosen at the 95th percentile of patients with relevant non-malignant diseases and sensitivities for cancer patients were calculated. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC)-curves were established to cover the entire spectrum of sensitivity and specificity. This analysis was also done for the comparison of the diagnostic relevance of sMICB and sMICA for cancer detection for the whole sample of patients. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For all statistics, software of SAS (version 8.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used.

Results

We analyzed the levels of sMICB in serum of 296 patients with various cancers including colorectal and various other gastrointestinal cancers, lung cancer, breast cancer, ovarian and other gynecologic cancers, renal and prostate cancer. In parallel, we analyzed sera from 62 healthy donors and 154 patients with benign diseases that were chosen for investigation according to the most frequent cancer groups and to their relevance for differential diagnosis in clinical practice.

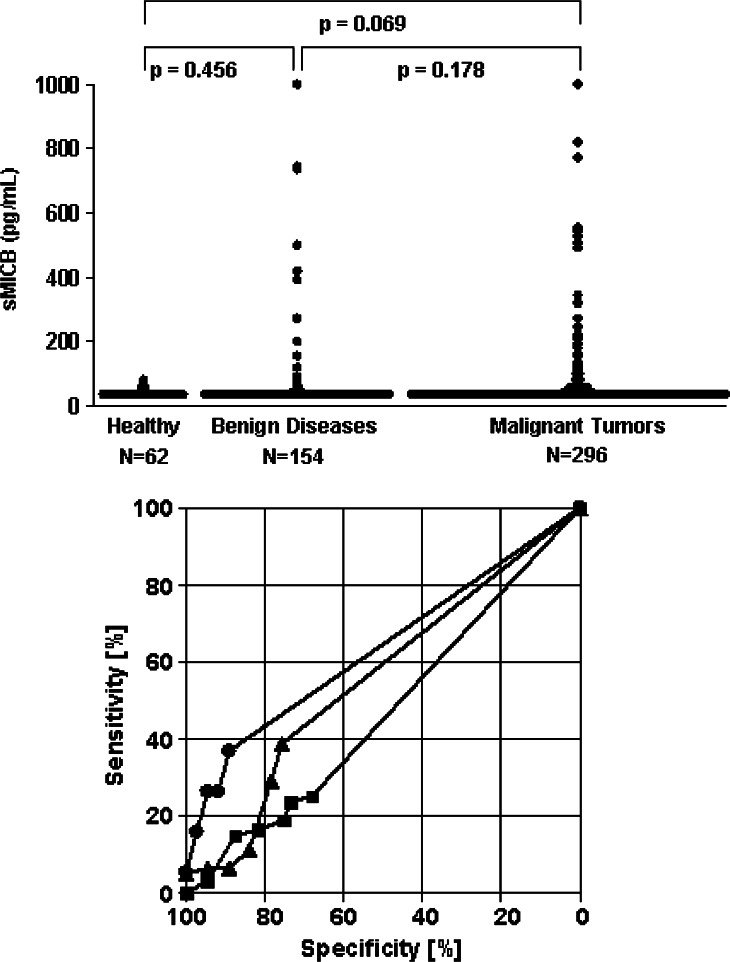

Healthy individuals revealed lower sMICB values (95th percentile 51 pg/ml) than cancer patients (95th percentile 216 pg/ml; P = 0.069), but differences were not significant. In addition, sMICB levels did not differ significantly between healthy individuals and patients with benign diseases (95th percentile 198 pg/ml; P = 0.456) as well as between cancer patients and patients with benign disorders (P = 0.178) that represent the most relevant control group for differential diagnosis (Fig. 1a). Significant differences between healthy controls and cancer patients were only found in the subgroup of gynecologic cancers (P = 0.028) and between benign and malignant diseases for lung cancer (P = 0.022).

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic impact of soluble MICB levels for cancer detection. a Serum levels of sMICB in healthy individuals, patients with benign diseases or patients with malignant tumors. b Receiver operating characteristic-curves illustrating the power of sMICB for discrimination between patients with malignant tumors and patients with the respective benign disorders (filled circle lung diseases; filled triangle gynecologic diseases; filled square gastrointestinal diseases)

sMICB levels higher than the 95th percentile of healthy persons were observed in 15% of patients with benign diseases and in 18% of cancer patients (16% of gastrointestinal cancers, 21% of lung cancer, and 18% of gynecologic cancers, respectively). The high numbers of patients with low sMICB levels in all groups as well as the considerable overlap of sMICB concentrations in the different groups that are relevant for differential diagnosis of cancer are mirrored in the ROC-curves. Best results were obtained in the subgroup of lung diseases with a sensitivity of 26.3% for cancer detection at a specificity of 95% against benign lung diseases (Fig. 1b).

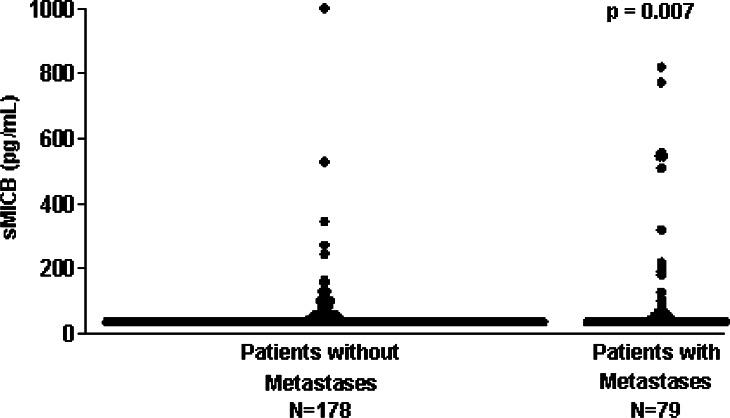

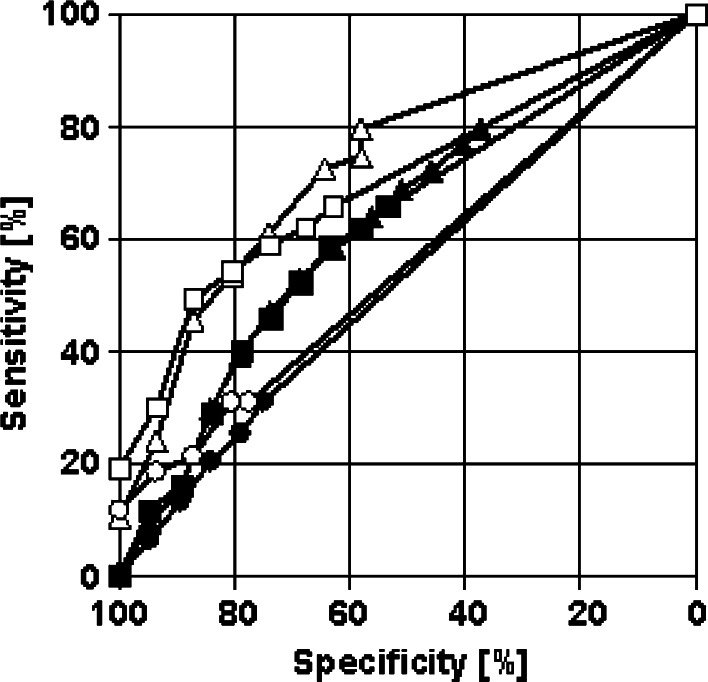

The sMICB levels in cancer patients significantly correlated with the extent of disease (P = 0.007): while there was no association between sMICB levels and tumor size (P = 0.395), cell differentiation (P = 0.656), or lymph node involvement (P = 0.782), sMICB levels correlated significantly with metastasis (P = 0.007) (Fig. 2). Between the NKG2D ligands, sMICB and sMICA, only a weak correlation (r = 0.24) was found. In ROC-curves, a small but not substantial additive effect of both markers was observed in the high specificity range: while at a specificity of 95% against healthy controls the sensitivity for cancer detection was 18.6% for sMICB and 24.0% for sMICA, it reached 30.1% when both markers were combined (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Correlation of soluble MICB levels with metastases

Fig. 3.

Combination of soluble MICB and MICA for cancer detection. Receiver operating characteristic-curves illustrating the power of sMICB (circle), sMICA (triangle), and the combination of both (square), respectively, for the discrimination between patients with malignant tumors and healthy donors (empty symbols) as well as between patients with malignant tumors and patients with benign disorders (filled symbols)

Within healthy individuals, correlation between sMICA and sMICB was r = 0.49, within patients with benign diseases r = 0.25 and within cancer patients r = 0.23. In patients with gastrointestinal diseases, the correlation coefficient of sMICA and sMICB was r = 0.17. At a specificity of 95% against healthy controls the sensitivity for gastrointestinal cancer detection was 16.4% for sMICB, 21.9% for sMICA, and 29.7% for the combination of both markers. In patients with gynecological diseases, a considerably higher correlation coefficient of sMICA and sMICB was found (r = 0.39). At a specificity of 95% against healthy controls the sensitivity for gynecological cancer detection was 17.7% for sMICB, 27.9% for sMICA, and 29.0% for the combination of both markers. A similar correlation coefficient of sMICA and sMICB was obtained in patients with lung diseases (r = 0.35). At a specificity of 95% against healthy controls the sensitivity for lung cancer detection was 21.1% for sMICB, 15.8% for sMICA, and 26.3% for the combination of both markers.

Discussion

Recent findings indicate that a diminished expression of NKG2DL on the tumor cell surface due to enhanced proteolytic shedding constitutes a novel tumor immune escape mechanism [13]. Accordingly, elevated levels of soluble MICA were found in sera of patients with various malignancies [5, 13, 14, 17–19]. These findings were recently extended by our comprehensive study on more than 500 patients revealing that sMICA levels were significantly elevated in cancer diseases compared with healthy controls as well as with benign diseases, and correlated with cancer stage and metastasis [16]. However, so far no thorough evaluation has been performed about the diagnostic potential of serum levels of MICB, the second MIC molecule among the NKG2DL, in various malignant diseases, especially on its additional value in correlation with sMICA.

Here, in a large study including 512 individuals we analyzed sMICB levels in sera of cancer patients and compared these to sMICB levels in patients with the respective organ-specific benign diseases and in healthy individuals. In addition, we addressed the correlation of sMICB with tumor stage and differentiation to evaluate sMICB as a marker in differential diagnosis and staging of cancer. Furthermore, we performed a correlation with the respective sMICA levels in the same patient set.

Analysis of serum samples revealed that healthy individuals had slightly but not significantly lower sMICB values than cancer patients. However, sMICB levels did not differ significantly between healthy persons and patients with benign as well as between cancer patients and patients with benign disorders. The latter ones represent the most relevant control group for differential diagnosis. Thus, sMICB seems not to be helpful for cancer detection—particularly not in early stages. This is in contrast to our findings regarding sMICA which have shown statistically significant differences between MICA levels cancer patients and healthy controls as well as with patients with benign diseases [16]. Presently, little is known about a distinct regulation of MICA versus MICB expression that may be accountable for the lower sMICB levels as compared to sMICA in the investigated patient sera. However, there is experimental evidence that MICB mRNA expression of upon heat-shock or HCMV infection is more tightly controlled as compared to MICA [20, 21]. Since in both sMICB and sMICA levels a notable overlap was seen in all relevant groups, particularly in the low concentration range, determination of MIC molecule levels is not suited for making diagnostic decisions on the single patient level. This is in line with reports on already established tumor markers, such as cytokeratin-19 fragments (CYFRA 21-1) [22, 23] and CA 15-3 [24], which are tumor specific only at very high concentrations, and resembles the remarkable variability among tumors to express and release tumor-associated molecules. However, most tumor markers which are currently in practical use show a higher sensitivity at the 95% specificity against healthy controls and patients with the respective benign diseases than NKG2DL, e.g., for CYFRA 21-1 in non-small cell lung cancer, ProGRP in small cell lung cancer and CA 15-3 in breast cancer [22–25]. Whether determination of sMICA and sMICB can add diagnostic information to these markers will therefore have to be determined in future studies. Nevertheless it has to be stated that many established oncological markers are also elevated in benign diseases such as renal insufficiency or infections which limits their diagnostic specificity [22, 25]. Though this limits the use of tumor markers for screening purposes, they are valuable tools in differential diagnosis and therapy monitoring when potentially disturbing factors are taken into account.

A considerable number among the patients with malignancies was found to be completely seronegative for MICB (69%), which corresponds to the results of immunohistochemical analyses which revealed a significant number of tumors lacking MIC molecule expression [4], and exceeds our previous results showing 20% of cancer patients being seronegative for sMICA [16]. Whereas several studies analyzed expression of MICA/B proteins in tumors, no studies are currently available that systematically address a comparison of the expression of MICA versus MICB in primary tumors. Thus we can only speculate that the lower frequency of sMICB-seropositive cancer patients may be due to a lower rate of MICB expression by primary tumors and/or due to a less efficient shedding activity. Another possible mechanism of reducing MICB surface expression was reported by Raffaghello et al. who showed that MICB preferentially is sequestered into the cytoplasm of neuroblastoma [19].

Similar to the results obtained with MICA, the best diagnostic discrimination between cancer patients and healthy controls using MICB was obtained in lung cancer. This might be due to the specific propensity of lung cancer to release considerable amounts of tumor-related antigens already in early stages [22, 25, 26]. Thus, determination of MIC molecules seems to be particularly well suited for differential diagnosis of this tumor entity, and further studies will have to compare its value with the presently used tumor markers CEA, CYFRA 21-1, NSE, and ProGRP [22, 25–27]. With respect to specific tumor characteristics, we found a clear correlation of sMICB levels with tumor stage confirming the data obtained with MICA. The sMICB levels were particularly elevated in patients with distant metastases, but showed no correlation with tumor size, cell differentiation or lymph node involvement again paralleling our previous results with sMICA [16]. This indicates that these results obtained for both sMICA and sMICB might be due to yet unknown general pathophysiological conditions in systemic manifestation of malignancy differing from those for local tumor extent or differentiation grade. Elevated sMICB levels in metastatic versus localized disease, similarly like MICA levels, may reflect differences in tumor vascularization. However, they may also be a consequence of enhanced shedding of MIC molecules which might impair the confining immunosurveillance by cytotoxic lymphocytes. It is noteworthy, however, that this finding applies for both MIC molecules. In this regard it is surprising that only a weak relation was found between the serum levels of MICB and MICA, particularly in patients with benign and malignant diseases. This suggests that different pathophysiologic mechanism underlie the surface expression and release of MICA versus MICB. Since as to now no data are available regarding a potential association of either MIC molecule with certain pathophysiological conditions or tumor entities, we cannot comment on the responsible mechanisms. However, this finding offers the possibility of a combined use of sMICA and sMICB levels to improve the diagnostic sensitivity. Indeed, a small but not substantial additive effect was observed for the combination of sMICA and sMICB for cancer detection in the high specificity range. Improvement of diagnostic characteristics by the use of marker combination were also seen in the subgroups of gastrointestinal and lung diseases, but not in gynecological diseases. The potential additional role of other soluble NKG2DL in cancer diagnosis like the ULBP proteins, which can also be released in a soluble form [28; A. Steinle, unpublished data], is still to be clarified.

Taken together, our study provides comprehensive information regarding the clinical value of sMICB analysis. sMICB levels were slightly but not significantly higher in sera of cancer patients than in healthy controls and could not distinguish patients with benign and malignant diseases. However, in contrast to sMICA, sMICB levels were elevated in only a minority of cancer patients. The power of discrimination was highest in pulmonary diseases. Within cancer patients, sMICB levels correlate with cancer stage and metastasis similarly to sMICA. Further studies are ongoing to elucidate the value of both sMIC molecules for monitoring response to therapy and their prognostic relevance in malignant diseases.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Krebshilfe (10-1921-Sa, 10-2004-Sa2).

Footnotes

Alexander Steinle and Helmut R. Salih contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Bauer S, Groh V, Wu J, Steinle A, Phillips JH, Lanier LL, Spies T. Activation of NK cells and T cells by NKG2D, a receptor for stress-inducible MICA. Science. 1999;285:727–729. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Randolph-Habecker J, Topp MS, Riddell SR, Spies T. Costimulation of CD8alphabeta T cells by NKG2D via engagement by MIC induced on virus-infected cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:255–260. doi: 10.1038/85321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. 2005;436:1186–1190. doi: 10.1038/nature03884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6879–6884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salih HR, Antropius H, Gieseke F, Lutz SZ, Kanz L, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Functional expression and release of ligands for the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D in leukemia. Blood. 2003;102:1389–1396. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diefenbach A, Jensen ER, Jamieson AM, Raulet DH. Rae1 and H60 ligands of the NKG2D receptor stimulate tumour immunity. Nature. 2001;413:165–171. doi: 10.1038/35093109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerwenka A, Baron JL, Lanier LL. Ectopic expression of retinoic acid early inducible-1 gene (RAE-1) permits natural killer cell-mediated rejection of a MHC class I-bearing tumor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11521–11526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201238598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pende D, Rivera P, Marcenaro S, Chang CC, Biassoni R, Conte R, Kubin M, Cosman D, Ferrone S, Moretta L, Moretta A. Major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain A and UL16-binding protein expression on tumor cell lines of different histotypes: analysis of tumor susceptibility to NKG2D-dependent natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6178–6186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castriconi R, Cantoni C, Della Chiesa M, Vitale M, Marcenaro E, Conte R, Biassoni R, Bottino C, Moretta L, Moretta A. Transforming growth factor beta 1 inhibits expression of NKp30 and NKG2D receptors: consequences for the NK-mediated killing of dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4120–4125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730640100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friese MA, Wischhusen J, Wick W, Weiler M, Eisele G, Steinle A, Weller M. RNA interference targeting transforming growth factor-beta enhances NKG2D-mediated antiglioma immune response, inhibits glioma cell migration and invasiveness, and abrogates tumorigenicity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7596–7603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriegeskorte AK, Gebhardt FE, Porcellini S, Schiemann M, Stemberger C, Franz TJ, Huster KM, Carayannopoulos LN, Yokoyama WM, Colonna M, Siccardi AG, Bauer S, Busch DH. NKG2D-independent suppression of T cell proliferation by H60 and MICA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11805–11810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502026102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salih HR, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Cutting edge: down-regulation of MICA on human tumors by proteolytic shedding. J Immunol. 2002;169:4098–4102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groh V, Wu J, Yee C, Spies T. Tumour-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 2002;419:734–738. doi: 10.1038/nature01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokoyama WM. Immunology: catch us if you can. Nature. 2002;419:679–680. doi: 10.1038/419679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holdenrieder S, Stieber P, Peterfi A, Nagel D, Steinle AL, Salih HR. Soluble MICA in malignant diseases. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:684–687. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doubrovina ES, Doubrovin MM, Vider E, Sisson RB, O’Reilly RJ, Dupont B, Vyas YM. Evasion from NK cell immunity by MHC class I chain-related molecules expressing colon adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2003;171:6891–6899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu JD, Higgins LM, Steinle A, Cosman D, Haugk K, Plymate SR. Prevalent expression of the immunostimulatory MHC class I chain-related molecule is counteracted by shedding in prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:560–568. doi: 10.1172/JCI22206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raffaghello L, Prigione I, Airoldi I, Camoriano M, Levreri I, Gambini C, Pende D, Steinle A, Ferrone S, Pistoia V. Downregulation and/or release of NKG2D ligands as immune evasion strategy of human neuroblastoma. Neoplasia. 2004;6:558–568. doi: 10.1593/neo.04316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welte SA, Sinzger C, Lutz SZ, Singh-Jasuja H, Sampaio KL, Eknigk U, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. Selective intracellular retention of virally induced NKG2D ligands by the human cytomegalovirus UL16 glycoprotein. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:194–203. doi: 10.1002/immu.200390022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groh V, Bahram S, Bauer S, Herman A, Beauchamp M, Spies T. Cell stress-regulated human major histocompatibility complex class I gene expressed in gastrointestinal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12445–12450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schalhorn A, Fuerst H, Stieber P. Tumor markers in lung cancer. J Lab Med. 2001;25:353–361. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stieber P, Hasholzner U, Bodenmuller H, Nagel D, Sunder-Plassmann L, Dienemann H, Meier W, Fateh-Moghadam A. CYFRA 21-1. A new marker in lung cancer. Cancer. 1993;72:707–713. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930801)72:3<707::AID-CNCR2820720313>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stieber P, Molina R, Chan DW, Fritsche HA, Beyrau R, Bonfrer JM, Filella X, Gornet TG, Hoff T, Jager W, van Kamp GJ, Nagel D, Peisker K, Sokoll LJ, Troalen F, Untch M, Domke I. Clinical evaluation of the Elecsys CA 15-3 test in breast cancer patients. Clin Lab. 2003;49:15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molina R, Filella X, Auge JM. ProGRP: a new biomarker for small cell lung cancer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:505–511. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stieber P, Yamaguchi K. ProGRP enables diagnosis of small-cell lung cancer. In: Diamandis EP, Frische HA, Lilja H, Chan DW, Schwartz MK, editors. Tumor markers; physiology, pathobiology, technology, and clinical applications. 1st. Washington: AACC; 2002. pp. 517–521. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molina R, Filella X, Auge JM, Fuentes R, Bover I, Rifa J, Moreno V, Canals E, Vinolas N, Marquez A, Barreiro E, Borras J, Viladiu P. Tumor markers (CEA, CA 125, CYFRA 21-1, SCC and NSE) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer as an aid in histological diagnosis and prognosis. Comparison with the main clinical and pathological prognostic factors. Tumour Biol. 2003;24:209–218. doi: 10.1159/000074432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onda H, Ohkubo S, Shintani Y, Ogi K, Kikuchi K, Tanaka H, Yamamoto K, Tsuji I, Ishibashi Y, Yamada T, Kitada C, Suzuki N, Sawada H, Nishimura O, Fujino M. A novel secreted tumor antigen with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored structure ubiquitously expressed in human cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;285:235–243. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]