Abstract

Tumor infiltration by lymphocytes is essential for cell-mediated immune elimination of tumors in experimental systems and in immunotherapy of cancer. Presence of lymphocytes in several human cancers has been associated with a better prognosis. We present evidence that individual propensity to tumor infiltration is genetically controlled. Infiltrating lymphocytes are present in 50% of lung tumors in O20/A mice, but in only 10% of lung tumors in OcB-9/Dem mice. This difference has been consistent in experiments conducted over 8 years in two different animal facilities. To test whether this strain difference is controlled genetically, we analyzed the presence of infiltrating lymphocytes in N-ethyl-N-nitroso-urea (ENU) induced lung tumors in (O20 × OcB-9) F2 hybrids. We mapped four genetic loci, Lynf1 (Lymphocyte infiltration 1), Lynf2, Lynf3, and Lynf4 that significantly modify the presence and intensity of intra-tumoral infiltrates containing CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. These loci appear to be distinct from the genes encoding the molecules that are presently implicated in lymphocyte infiltration. Our findings open a novel approach for the assessment of individual propensity for tumor infiltration by genotyping the genes of the host that influence this process using DNA from any normal tissue. Such prediction of probability of tumor infiltration in individual cancer patients could help considerably to assess their prognosis and to decide about the application and the type of immunotherapy.

Keywords: Tumor infiltration by lymphocytes, Host’s genetic control, Gene mapping

Introduction

Capacity of lymphocytes to infiltrate tumors is a limiting factor for tumor destruction [1]. Without tumor infiltration, a systemic presence of even very large numbers of tumor antigen-specific T lymphocytes that are capable of killing the tumor cells in vitro does not prevent tumor growth and progression [2–4]. In human colorectal and ovarian cancers as well as in melanomas, lymphocyte infiltration has been shown to be strongly associated with a better prognosis [5–8].

The capacity of circulating lymphocytes to infiltrate the tumor mass is also critical for immunotherapy of human cancers. One of the important reasons why T cells generated by cancer vaccines fail to destroy solid tumors is the absence of immune cell infiltration in tumors [9]. Therefore, it would be important to assess the probability of tumor infiltration and to understand the factors that determine its presence or absence before starting any immunotherapy. Presently, the known processes underlying tumor infiltration by lymphocytes involve expression of specialized molecules on circulating lymphocytes and vascular endothelium, remodeling of blood vessels in the tumor (reviewed in [10]), and production of cytokines and chemokines regulating the lymphocyte migration. However, as most of these factors can only be measured by a direct ex vivo or in vitro analysis of the tumor and its blood vessels, they do not offer a useable method to predict whether infiltration will or will not occur in individual patients.

We describe a novel feature of lymphocyte tumor infiltration—its control by germline genes of the host. Genotyping of these genes can be done with DNA of any normal cell. Therefore, it can be used to assess the probability of tumor infiltration without requiring analysis of tumor tissue. The host’s control of tumor infiltration has been indicated by finding considerable differences in lung tumor infiltration between mouse strains [11] and subsequently by demonstrating that these strain differences are highly reproducible, largely independent of environment, and statistically highly significant [12]. Here we describe the mapping of four novel genetic loci, Lynf1 (Lynf Lymphocyte infiltration), Lynf2, Lynf3, and Lynf4, that significantly influence the presence and intensity of lymphocyte infiltrates in carcinogen-induced autochthonous lung tumors.

Materials and methods

The induction of tumors and genotyping of mice were performed in the laboratory of P. D. at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam and the experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Ethical Committee of the Institute. The evaluation of lymphocyte infiltration and linkage analysis were performed at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute. The lung tumors that were used for evaluation of the type of infiltrating cells and validation of the reported linkages have been induced at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute under IACUC protocol 905 M.

Mice

Mice received a standard laboratory diet (Hope Farms, Woerden, Netherlands) and acidified drinking water. They were maintained on a strict light–dark regimen. The recombinant congenic strain, OcB-9/Dem has 87.5% of the genome from O20/A strain and 12.5% from B10.O20/Dem strain [13]. Its genetic composition has been described previously [14, 15]. These mouse strains have been previously used to map the genes that control lung tumor number, size, progression, and shape [16–19].

NTX-1 and NTX-16 are recombinant strains derived from a cross between OcB-9 and O20. They are polymorphic at the Lynf1 locus, carrying B10.O20 and O20 alleles, respectively. They were used to validate the Lynf1 locus in an independent experiment.

Carcinogen treatment

For linkage tests, we produced F2 mice between the recombinant congenic OcB-9 strain and the O20 strain and between the strains NTX-1 and NTX-16. The pregnant (OcB-9 × O20) F1 and (NTX-1 × NTX-16) F1 females were given an i.p. injection of 40 mg/kg body weight of ENU (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea) on the 18th day of gestation [16]. The (OcB-9 × O20) F2 and (NTX-1 × NTX-16) F2 offspring of carcinogen-injected F1 females were euthanized at the age of 16 weeks. These groups comprised 197 and 35 mice, respectively. The lungs were removed and fixed in 40% (v/v) ethanol, 5% (v/v) acetic acid, 4% (v/v) formaldehyde, and 0.41% NaCl and embedded in histowax.

Evaluation of lymphocyte infiltration

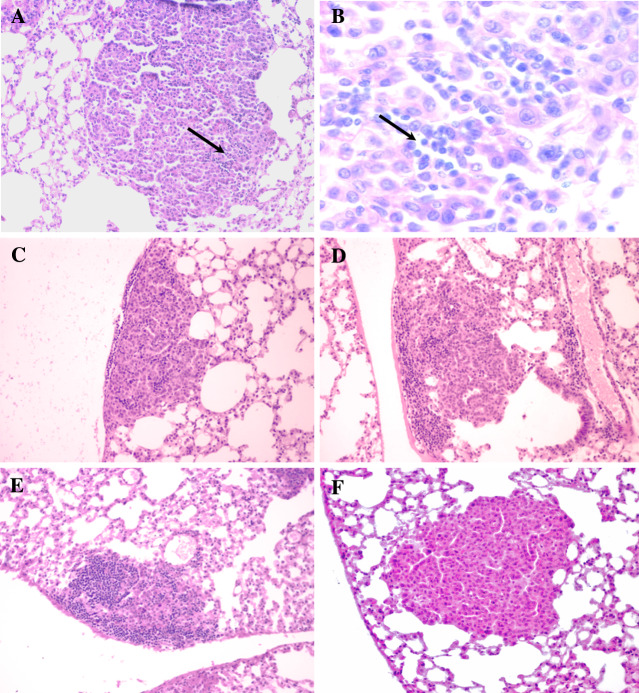

The whole lungs were sectioned semi-serially (5 μm sections at 100 μm intervals; usually about 35 sections per mouse) and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. All sections were inspected by two investigators and tumors in each section were scored for the presence or absence of lymphocyte infiltration. Most tumors were present in several sequential sections. The 197 (OcB-9 × O20) F2 hybrids developed 607 lung tumors that were present in 2,756 sections. Lymphocyte infiltration was evaluated microscopically in the whole extent of each section of each tumor. All fields of all tumor-sections were evaluated at two magnifications (50× and 400×). All instances where lymphocytes were present inside the perimeter of the tumor in direct contact with tumor cells and were spread over a part of the area of a section of the tumor were classified as intratumoral lymphocyte infiltration. The boundaries of tumors were readily defined with very few exceptions. Infiltration in every section of a tumor was scored semi-quantitatively with values of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 depending on the extent of lymphocyte infiltration (Fig. 1). The average of scores obtained for individual sections of a tumor represents the infiltration score of the tumor. Average of scores of all tumors in a mouse represents the infiltration score of the mouse. All evaluations were performed blindly, without knowledge of the genotypes of mice.

Fig. 1.

Different degrees of lymphocyte infiltration in mouse lung tumors. a Score 0.5; b 800× magnification of the part of the section containing infiltrates, arrow indicates the area with infiltration; c score 1; d score 2; e score 3 ; f no infiltration, score 0; (haematoxylin–eosin, 200× magnification on a, c, d, e and f)

Immunohistochemistry

Lymphocytes inside the tumor boundary were characterized by immunohistochemistry on frozen sections of the mouse lung as described previously [20]. Lung tissue was infused via trachea with Tissue Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Inc., Torrance, CA). The whole lung was embedded in Tissue Tek and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Regions containing the tumor were cut at 5–7 μm thickness, fixed in acetone and stored at −20°C. Sections were rehydrated in PBS, pH 7.2. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0.3%H2O2.

To prevent non-specific binding of antibodies, sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum. Sections were stained with monoclonal antibodies for the detection of CD4+ T lymphocytes (GK1.5) or CD8+ T lymphocytes (53–6.72). The antibodies were a kind gift from Prof. W.A. Burman (Dept. of General Surgery, Maastricht University, The Netherlands). After washing, biotin conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Pharmingen San Diego, CA, USA) preincubated with 5% normal mouse serum was applied as the secondary antibody. Control staining was performed by replacing the primary antibody with Rat IgG (Jackson Immuno Research, USA). The signal enhancement was done using a Vectastain ABC Elite kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame CA, USA). Enzymatic reactivity was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine in chromogen substrate buffer (DAB Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria CA, USA). Sections were counterstained with Harris Hematoxylin and mounted.

Genotyping

DNA of F2 hybrid mice was isolated from the tails using a standard proteinase procedure and genotyped for simple sequence length polymorphism (Mouse Map Pairs, Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). The 197 (OcB-9 × O20) F2 hybrids were tested with 15 markers: D2M156, D2M465, D4M158, D6M21, D6M218, D7M32, D7M71, D8M3, D8M65, D10M122, D11M15, D16M9, D18M17, D19M61, and D19M9. These markers were selected because they cover optimally the chromosomal segments at which the OcB-9 strain has genetic material from the B10.O20 strain. They carry different alleles in the two strains, the O20 allele (designated o) and the B10.O20 allele (designated b). The genotyping was done during the previous study [16].

Statistical analysis

The large number of primary ordinal/interval scores permits their treatment as interval values including calculation of the mean [21]. Analysis of variance for the infiltration scores of the individual mice was performed using PROC GLM statement of the SAS 8.2 for Windows. The effect of each marker, sex, and the interactions between markers or between marker and sex, on lymphocyte infiltration was tested. Each individual marker and its interactions with other markers and sex were subjected to ANOVA. A backward elimination procedure [11] was followed wherein the interaction or marker bearing the highest P value (if P > 0.05) was eliminated first. The markers and interactions with P value smaller than 0.05 were pooled for the next round of ANOVA. The backward elimination procedure was repeated till the final set of significant markers and interactions was obtained. The P values corrected for whole genome testing (Pc) were obtained according to Lander and Kruglyak [22].

Results

Detection of Lynf (lymphocyte infiltration) loci

OcB-9 (a low infiltration strain) is a recombinant congenic strain that contains 87.5% of genes from the strain O20 (a high infiltration strain) and a random set of 12.5 % genes from the strain B10.O20 (a low infiltration strain) (see “Materials and methods”). The low level of lymphocyte infiltration in both B10.O20 and OcB-9 tumors indicates that the latter strain has received one or more genes from the B10.O20 strain that are responsible for low degrees of infiltration. Therefore, we scored the presence of infiltrating lymphocytes in lung tumors of F2 hybrids produced from crossing the low-infiltration strain OcB-9 with the high infiltration strain O20. Lymphocyte infiltration in lung tumors in (O20 × OcB-9) F2 hybrids was scored semi-quantitatively (Fig. 1). To evaluate the reliability of scoring, infiltration scores of 29 mice (comprising 88 tumors present in 387 sections) were estimated again. The mean score difference between the two independent scoring steps was 11.0%, median difference 8.8%, thus demonstrating the robustness of the procedure. The individual infiltration scores of 97% of mice were lower than 1.0. We observed only a weak negative correlation between the tumor size and the lymphocyte infiltration score in tested mice (r = −0.0775, not significant).

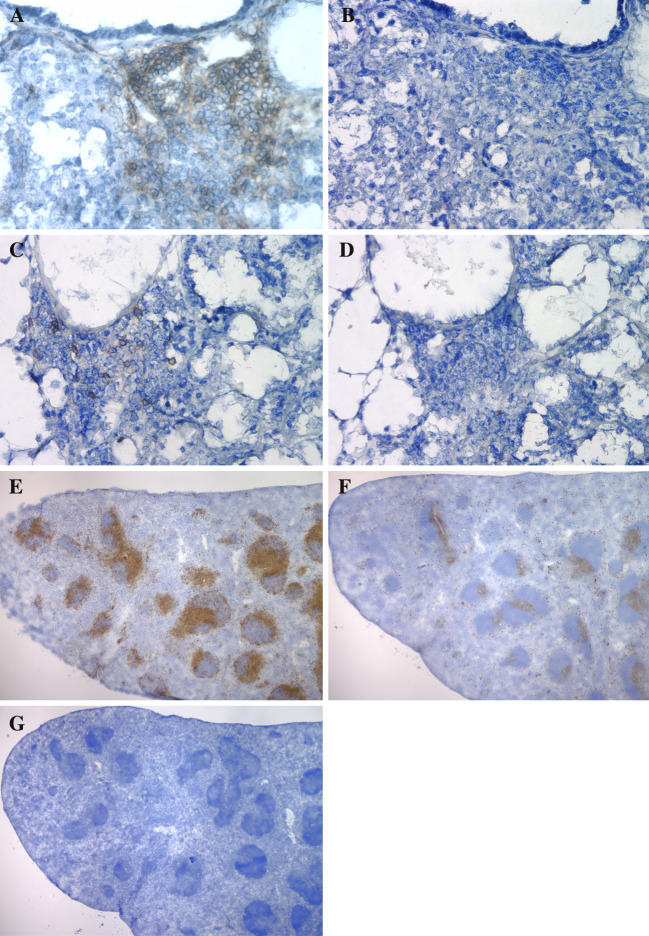

Immunohistochemistry staining indicated the presence of both CD4+ (Fig. 2a) and CD8+ (Fig. 2c) T lymphocytes within tumors (Fig. 2). The specificity of staining is demonstrated by negative staining in controls where primary antibody was replaced by rat IgG (Fig. 2b, d), and by staining of distinct splenic areas by CD4 and CD8 antibodies in sequentially cut spleen sections (Fig. 2e, CD4+; f, CD8+; g, primary antibody replaced with rat IgG).

Fig. 2.

CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltrating lung tumors. a Lung tumor with Rat anti-Mouse CD4 antibody and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies; b consecutive section of the tumor with Rat IgG and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies; c lung tumor with Rat anti-Mouse CD8 and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies; d consecutive section of the tumor with Rat IgG and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies; e spleen section with Mouse anti-Rat CD4 and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies; f spleen section with Mouse anti-Rat CD8 and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies; g spleen section with Rat IgG and biotin-conjugated Goat anti-Rat IgG antibodies

The F2 mice were genotyped for the microsatellite markers polymorphic between O20 and OcB-9. The relationship between the genotype at the microsatellite markers and the degree of lymphocyte infiltration in lung tumors has been determined by analysis of variance. We searched also for two-way interactions of loci that influence the infiltration of lymphocytes. The results of linkage study are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Effects of genotype at the loci Lynf1–Lynf4 on the infiltration score of lung tumors in (OcB-9 × O20) F2 hybrids

The effects of genotypes at Lynf loci, independent and in interactions, on degree of infiltration (infiltration scores) in the lung tumors of (O20 × OcB-9) F2 hybrids. The phenotypic values given for individual genotypes indicate mean and standard errors of the infiltration scores and (in brackets) the number of mice

(B10.O20 allele b, O20 allele o), P = nominal P value, Pc = P value corrected for total genome screen

We detected four genetic loci determining lymphocyte infiltration: Lynf1 linked to D4Mit158, Lynf2 linked to D8Mit3, Lynf3 linked to D6Mit218, and Lynf4 linked to D6Mit21. The effects of these loci on the presence of lymphocyte infiltration (mean and standard error values of each genotype) and the P values of linkage corrected for the whole genome screen (Pc—P corrected; see “Materials and methods”) are given in Table 1. The loci Lynf2 and Lynf4 have independent effects (Table 1A). On the other hand, the loci Lynf1 and Lynf3 interact with each other. Lynf3 also interacts with Lynf2 (Table 1B). The chromosomal regions close to microsatellite markers D8Mit3 (Lynf2) and D6Mit21 (Lynf4) show a significant effect on lymphocyte infiltration with Pc values of 0.0128 and 0.0343, respectively. The mice homozygous for the O20 allele (oo) of D8Mit3 have a higher intensity and frequency of lymphocyte infiltration than mice carrying the B10.O20 allele (bb or bo) of D8Mit3. The mice homozygous or heterozygous for the B10.O20 allele (bb or bo) at the D6Mit21 locus have a higher lymphocyte infiltration in their tumors than mice homozygous for the O20 allele (oo) of D6Mit21.

Interactions between Lynf loci

We detected two interactions between Lynf loci. The Lynf3 locus marked by D6Mit218 interacts with Lynf1 (Pc 0.013) and Lynf2 (Pc 0.00012) that are marked by D4Mit158 and D8Mit3, respectively. In both interactions, the mice homozygous for B10.O20 alleles (bb) both at D6Mit218 and at D4Mit158 or D8Mit3, have very limited infiltration in lung tumors when compared to other genotypes.

Independent validation of Lynf1 locus

(NTX-1 × NTX-16) F2 hybrids transplacentally treated by ENU were genotyped for the marker D4Mit126 that lies close (4 cM ) to the marker D4Mit158, to which Lynf1 has been originally linked (Table 1). We tested 18 mice homozygous for O20 allele (oo) of D4Mit126 and 17 mice homozygous for B10.O20 allele (bb), respectively. The lung tumors of these mice were scored for the presence of lymphocyte infiltration. The average infiltration score for D4Mit26 bb homozygotes was 0.013 and for oo homozygotes 0.076 (P = 0.029, analysis of variance). Seventeen percent (3/17) of bb homozygous mice had at least one tumor with lymphocyte infiltration, compared to 50% (9/18) of oo homozygotes (P = 0.04, Chi-square 1 df). The lower overall level of infiltration in NTX mice as compared with (O20 × OcB-9) F2 hybrids is probably due to their different genetic backgrounds. This independent experiment confirms in different strains the role of the Lynf1 chromosomal region in lymphocyte infiltration of tumors, in spite of different genetic backgrounds and lack of polymorphism at the interacting Lynf3 locus.

Discussion

Detection and mapping of Lynf loci

We detected and mapped four loci, Lynf1–Lynf4, that control the intensity of lymphocyte infiltration in lung tumors. Two loci, Lynf2 and Lynf4 have effects that are not influenced by interactions with other genes (main effects). The homozygosity for the O20 allele of Lynf2 (oo) is associated with about a two fold higher intensity of infiltration than the homozygosity of the B10.O20 allele (bb). In contrast, homozygosity for the B10.O20 allele of Lynf4 (bb) results in about a seven-times higher intensity of infiltration than the homozygosity of the O20 allele (oo). The association of the B10.O20 allele of Lynf4 (that originates from the low-infiltration strain B10.O20) with a high infiltration is paradoxical only seemingly, because a complex quantitative phenotype (such as lymphocyte infiltration) is a result of action of several genes, some with a positive effect and some with a negative effect. So, strains with a “high infiltration” phenotype can contain at some loci alleles determining a “low infiltration” phenotype and vice versa. The Lynf1 locus has been validated in an independent test using different mouse strains. We are preparing Lynf congenic strains that will be used to validate the other Lynf loci.

The loci Lynf1 and Lynf2 seem to be similar, as they both exhibit linkage with lung tumor susceptibility, lung tumor progression, and macrophage and lymphocyte activation [11, 17, 19, 23, 24]. Both Lynf1 and Lynf2 also interact in (O20 × OcB-9) F2 hybrids with Lynf3 in a similar way, mice homozygous for the B10.O20 allele of Lynf3 (bb) and for the B10.O20 allele of Lynf1 or Lynf2 (bb) have virtually no tumor infiltration, but the Lynf3 (bb) mice with one or two O20 alleles (bo or oo) of Lynf1 or Lynf2 have a higher degree of tumor infiltration. It thus appears as if the O20 allele of Lynf1 and Lynf2 loci could compensate for the absence of the O20 allele of Lynf3.

No obvious relation of Lynf loci to other known genes involved in lymphocyte trafficking

Tumor infiltration depends on a number of molecules. Adhesion molecules like selectins and integrins and their ligands play an important role. Their expression is regulated by signals that include several cytokines and chemokines. After diapedesis through vascular endothelium, the migration of lymphocytes into tumors is further guided by chemokines and cytokines produced by tumor cells and resident macrophages or dendritic cells [10, 25, 26]. To ascertain whether any of the molecules that have been previously described to participate directly in lymphocyte trafficking and tumor infiltration, or members of their families, may be encoded by one of the Lynf loci described here, we searched the chromosomal location of such genes in the Mouse Genome Informatics database 3.4 (http://www.informatics.jax.org). These genes were cell surface antigens-Cd34, Cd44, chemokine and chemokine ligand genes- Ccl2, Ccl5, Cxcl12, Ccl4, Cxcr4, Ccr3, Ccl1, Ccl3, Ccl7, Ccl16, Ccl19B, Ccl20B, Ccl21, Ccl22, Ccl27, Cxcl2, Cxcll4, Cxcl9, Cxcl10, Cxcl9, Cxcl13, Ccl19, Ccl17, Cdcl21, Cxcr10, Cxcl12, Cxcl14, Ccl19, Ccl20, cell adhesion molecule genes-Vcam1, Icam1, Icam2, Icam3, Madcam1, Pecam1, Glycam1, Sell (Lselectin), Sele (Eselectin), Selp (Pselectin), Selpl (Pselectin ligand), Fibronectin gene family, Cadherin gene family, integrin genes- Itga4 (Vla4), Itgal (Lfa1), Itgb7, molecules involved in inflammatory pathways- Tgfb1, Vegfa, Nfkb1, Nfkb2, Inos2, Ptgs2 (Cox2), Hif1a, Stat3, Nfe2l2 (Nrf2), Nfat5, Tnf super family, Ifng, cytokine genes-Il1b, Il1a, Il8, Il4, Il10, Il6 Il12, Il12a, Il37, Il5, Il13, Il2, and matrix metalloproteinase genes-Mmp-9, Mmp-3, Mmp-7, Mmp-24, Mmp-2, Mmp-19, Mmp-17, Mmp-16, Mmp-15, Mmp-14, Mmp-12, Mmp-11 (detailed information available on request). We found that none of these genes were mapping into the same chromosomal regions as the four Lynf loci. Therefore, the four Lynf genes likely encode molecules that have not yet been implicated in tumor infiltration.

Type of infiltrating lymphocytes regulated by host’s genome

We have shown (Fig. 2) that the lymphocytes in infiltrated tumors include both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. The dramatic difference between the almost totally absent lymphocyte infiltration in tumors of OcB-9 mice and the frequent infiltration of tumors in O20 mice, as well as the presence of both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in (O20 × OcB-9) F2 hybrids, indicate that the Lynf loci described here control the presence of both the cell types in tumors. We did not establish whether some loci affect preferentially one cell type (CD4+ or CD8+). Lynf congenic strains that are being presently prepared will also be used to investigate whether the Lynf loci may differentially regulate presence of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes. We shall also test whether they affect the presence of the regulatory T cells, B-lymphocytes, granulocytes, and macrophages in tumors.

Lynf loci and tumor growth

Infiltrating lymphocytes can suppress tumor growth and progression. Entry of lymphocytes into the tumor or into its invasive margin is essential for cell-mediated inhibition of tumors’ growth. Human cancers that contain such infiltrates are less prone to recidivation or metastasis [5–8]. On the other hand, chronic inflammation may promote tumor development through mechanisms involving mainly effectors of innate immunity [27]. The strain O20 is more susceptible and has more tumors that are larger and more progressed than the strain OcB-9. However, it is difficult to relate this difference to the role of infiltrating lymphocytes, as these two strains differ in a large number (±9) of lung cancer susceptibility loci on different chromosomes, most of which probably regulate intracellular signaling mechanisms and are not related to interaction with host’s immune system. Therefore the answer to this question awaits tests of tumor susceptibility in Lynf-congenic strains. Interestingly, however, most Lynf loci described here seem to be genetically associated with tumor susceptibility genes.

We mapped previously, at the same two chromosomal locations as Lynf1 and Lynf2 also the lung tumor susceptibility loci Sluc6 and Sluc20, respectively, that control the number and the size of lung tumors [17, 18], and the loci Ltsd4 and Ltsd3, respectively, that control the lung tumor progression [19]. However, it is not possible to assess from the present data whether there is a direct correlation between the effects of Lynf loci and tumor susceptibility, because the Sluc6 and Sluc20 are involved in interactions with other Sluc loci [19] that may obscure the effects of Lynf loci, as these interacting partner Sluc loci may operate through pathways that are not mediated by lymphocytes. Lynf1 and Lynf2 are also linked to Marif1 and Marif2 loci, respectively, that control in vitro activation of macrophages [23], and loci Cinda3 and Cinda5, respectively, that control in vitro activation of lymphocytes [24]. Although this co-mapping of control of five different aspects of tumor growth and immunological functions in two apparently paralogous sets of loci, Lynf1-Sluc6-Ltsd4-Marif1-Cinda3 (chromosome 4) and Lynf2-Sluc20-Ltsd3-Marif2-Cinda5 (chromosome 8), may be co-incidental, it is also possible that these seemingly distinct five types of clustered loci actually reflect the activity of a single gene, and that the primary action of Lynf1 and Lynf2 genes resides in bone marrow-derived cells and modifies their activation and capacity to infiltrate, with subsequent modifications of tumor growth. As the actual genes responsible for the effects of Cinda and Marif loci have not yet been identified, and no in vivo effects of Cinda and Marif loci have yet been described, their possible functional association with lymphocyte infiltration or tumor susceptibility must be elucidated. We are currently engaged in precise genetic mapping and positional cloning of Lynf1 and Lynf2, which will make it possible to resolve their relationship to lung tumor susceptibility and progression, and to macrophage and lymphocyte activation.

Lynf4 is located in a vicinity of several genes involved in inflammation, wound healing or immune response (Pgia19 Proteoglycan-induced arthritis 19;Im4immunoregulatory 4; Stheal5 soft tissue healing 5; Mouse Genome Informatics 3.1). However there is, as yet, no obvious functional link between them and Lynf4.

The mapping of the Lynf loci and the subsequent molecular identification of the candidate genes that are responsible for the genetic regulation of lymphocyte infiltration will also make possible the mechanistic elucidation of their effects on tumor immunity. Although the presence of infiltrating lymphocytes is indispensable for cell mediated anti-tumor response [2–4], it is associated in many human cancers with a better prognosis [5–8], their functional significance and impact may be complex [28, 29]. Extensive literature shows that the anti-tumor effect of CD8+ cells occurs in the context of modifying effects of CD4+ cells, regulatory T cells, and myelomonocytic cells, see for example [30–32]. Our future studies aim to identify to what extent the individual Lynf loci affect specifically infiltration by different sub-classes of immunocytes. We have presently no information about the possible role of the four Lynf loci in tumor infiltration in other organs. Because lymphocyte infiltration has been reported to be a positive prognostic markers in a number of human cancers (for references see [5]), it is important to use the mouse model to establish the generality or organ specificity of the effects of individual Lynf loci, possibly using the Lynf congenic strains.

Potential implications for tumor biology and immunotherapy of cancer

Whereas a large part of the available data on mechanisms of tumor infiltration has been based on in vitro or ex vivo analyses, frequently using transplanted tumors, the phenotype investigated here is based exclusively on studies of in vivo induced primary autochthonous tumors. Hence, it mimics more closely the processes in human cancers. The second important feature of Lynf loci is that their genotype can be determined entirely without any analysis of tumor tissue. Therefore, the genetic factors described here are potentially highly convenient and suitable predictive markers for prognosis and immunotherapy of cancer. It has to be determined whether the loci described here also influence infiltration into other tumors or trafficking in normal tissues. The site of action of the Lynf loci can reside in bone marrow derived cells, or in the capacity of tumor cells to appropriately modify tumor vasculature and attract lymphocytes from circulation after they migrated through the vessels’ wall. To answer this question, we are studying infiltration of lung tumors in bone-marrow chimeras between high and low infiltration strains. Presently, we are also mapping the Lynf loci to very short chromosomal regions in order to identify molecularly by positional cloning the genes that are controlling lymphocyte infiltration. The identification of these genes will help to understand and possibly also to manipulate the critical steps of the immune response to tumors, and to improve the response to cancer immunotherapy and vaccination.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Bonnie Hylander and Ms. Mary Vaughan for useful comments and discussions of immunohistochemical staining, Dr. Min Hou for discussions on pathology of lung tumors, Ms. Mary Ketcham for assistance with preparation of figures, Mr. Michael J Habitzruther for excellent technical assistance.

Refrences

- 1.Ochsenbein AF, et al. Roles of tumour localization, second signals and cross priming in cytotoxic T-cell induction. Nature. 2001;411:1058–1064. doi: 10.1038/35082583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wick M, Dubey P, Koeppen H, Siegel CT, Fields PE, Chen L, Bluestone JA, Schreiber H. Antigenic cancer cells grow progressively in immune hosts without evidence for T cell exhaustion or systemic anergy. J Exp Med. 1997;186:229–238. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganss R, Hanahan D. Tumor microenvironment can restrict the effectiveness of activated antitumor lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4673–4681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganss R, Limmer A, Sacher T, Arnold B, Hammerling GJ. Autoaggression and tumor rejection: it takes more than self-specific T-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1999;169:263–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1999.tb01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galon J, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diederichsen AC, Hjelmborg JB, Christensen PB, Zeuthen J, Fenger C. Prognostic value of the CD4+/CD8+ ratio of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer and HLA-DR expression on tumour cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0388-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato E, et al. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18538–18543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemente CG, Mihm MC, Jr., Bufalino R, Zurrida S, Collini P, Cascinelli N. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg SA. Shedding light on immunotherapy for cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1461–1463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Q, Wang WC, Evans SS. Tumor microvasculature as a barrier to antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:670–679. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0425-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripodis N, Demant P. Genetic linkage of nuclear morphology of mouse lung tumors to the Kras-2 locus. Exp Lung Res. 2001;27:185–196. doi: 10.1080/713846267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horlings H, Demant P. Lung tumor location and lymphocyte infiltration in mice are genetically determined. Exp Lung Res. 2005;31:513–525. doi: 10.1080/01902140590918740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demant P, Hart AA. Recombinant congenic strains—a new tool for analyzing genetic traits determined by more than one gene. Immunogenetics. 1986;24:416–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00377961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stassen AP, Groot PC, Eppig JT, Demant P. Genetic composition of the recombinant congenic strains. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:55–58. doi: 10.1007/s003359900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groot PC, Moen CJ, Dietrich W, Stoye JP, Lander ES, Demant P. The recombinant congenic strains for analysis of multigenic traits: genetic composition. FASEB J. 1992;6:2826–2835. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.10.1634045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fijneman RJ, de Vries SS, Jansen RC, Demant P. Complex interactions of new quantitative trait loci, Sluc1, Sluc2, Sluc3, and Sluc4, that influence the susceptibility to lung cancer in the mouse. Nat Genet. 1996;14:465–467. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fijneman RJ, van der Valk MA, Demant P. Genetics of quantitative and qualitative aspects of lung tumorigenesis in the mouse: multiple interacting Susceptibility to lung cancer (Sluc) genes with large effects. Exp Lung Res. 1998;24:419–436. doi: 10.3109/01902149809087378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tripodis N, Hart AA, Fijneman RJ, Demant P. Complexity of lung cancer modifiers: mapping of thirty genes and twenty-five interactions in half of the mouse genome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1484–1491. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.19.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tripodis N, Demant P. Genetic analysis of three-dimensional shape of mouse lung tumors reveals eight lung tumor shape-determining (Ltsd) loci that are associated with tumor heterogeneity and symmetry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vernooy JH, Dentener MA, van Suylen RJ, Buurman WA, Wouters EF. Long-term intratracheal lipopolysaccharide exposure in mice results in chronic lung inflammation and persistent pathology. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:152–159. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.1.4652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.NormanGR, StreinerDL . Biostatistics, 2nd. Hamilton: BCDecker; 2000. p. 265. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lander E, Kruglyak L. Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet. 1995;11:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fijneman RJ, Vos M, Berkhof J, Demant P, Kraal G. Genetic analysis of macrophage characteristics as a tool to identify tumor susceptibility genes: mapping of three macrophage-associated risk inflammatory factors, marif1, marif2, and marif3. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3458–3464. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lipoldova M, Havelkova H, Badalova J, Demant P. Novel loci controlling lymphocyte proliferative response to cytokines and their clustering with loci controlling autoimmune reactions, macrophage function and lung tumor susceptibility. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:394–399. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:867–878. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butcher EC, Picker LJ. Lymphocyte homing and homeostasis. Science. 1996;272:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha P, Clements VK, Miller S, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Tumor immunity: a balancing act between T cell activation, macrophage activation and tumor-induced immune suppression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:1137–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0703-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baecher-Allan C, Anderson DE. Immune regulation in tumor-bearing hosts. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamaguchi T, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in immune surveillance and treatment of cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostrand-Rosenberg S. CD4+ T lymphocytes: a critical component of antitumor immunity. Cancer Invest. 2005;23:413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombo MP, Mantovani A. Targeting myelomonocytic cells to revert inflammation-dependent cancer promotion. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9113–9116. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]