Abstract

Overexpression of the proto-oncogene c-Myb occurs in more than 80% of colorectal cancer (CRC) and is associated with aggressive disease and poor prognosis. To test c-Myb as a therapeutic target in CRC we devised a DNA fusion vaccine to generate an anti-CRC immune response. c-Myb, like many tumor antigens, is weakly immunogenic as it is a “self” antigen and subject to tolerance. To break tolerance, a DNA fusion vaccine was generated comprising wild-type c-Myb cDNA flanked by two potent Th epitopes derived from tetanus toxin. Vaccination was performed targeting a highly aggressive, weakly immunogenic, subcutaneous, syngeneic, colon adenocarcinoma cell line MC38 which highly expresses c-Myb. Prophylactic intravenous vaccination significantly suppressed tumor growth, through the induction of anti-tumor immunity for which the tetanus epitopes were essential. Vaccination generated anti-tumor immunity mediated by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and increased infiltration of immune effector cells at the tumor site. Importantly, no evidence of autoimmune pathology in endogenous c-Myb expressing tissues was detected as a consequence of breaking tolerance. In summary, these results establish c-Myb as a potential antigen for immune targeting in CRC and serve to provide proof of principle for the continuing development of DNA vaccines targeting c-Myb to bring this approach to the clinic.

Keywords: c-Myb, Colorectal cancer, DNA vaccine, Autoimmunity, Tetanus toxin

Introduction

The development of effective treatments for colorectal cancer (CRC) beyond current cytotoxic chemotherapeutics is an important challenge in oncology. CRC accounts for 10% of cancer-related deaths, with a 5-year survival of 10% for patients with metastatic disease [24]. In the past decade combinatorial 5-fluorouracil and oxaloplatin therapies have increased median survival from 12 to 20 months [19]. This incremental improvement taken together with the deleterious effect of persistent toxic side effects on quality of life, highlights the requirement for more effective, targeted therapies for CRC [19].

c-Myb is a transcription factor and nuclear proto-oncogene which functions as a key regulator of cell growth, differentiation and survival [38]. Regulated expression is essential for expansion of stem and progenitor cells and the survival of differentiated cells in both the haematopoietic and gastrointestinal systems [37, 38] with partial loss of c-Myb expression leading to defects in these tissue compartments [29]. Additionally, mice lacking c-Myb expression die in uterus by day 15 [30] and the forced differentiation of CRC cell lines results in decreased c-Myb expression, cessation of proliferation and an increase in apoptosis [47].

In the disease setting, overexpression of c-Myb occurs in more than 80% of CRC in humans [37]. Additionally, increased expression correlates with disease severity [36] and is more pronounced in secondary tumor sites indicating a role in aggressive and metastatic disease [3]. c-Myb over-expression is also seen in other malignancies including breast cancer [43], oesophageal adenocarcinoma [5] and neuroblastoma [7] and has been successfully targeted using antisense c-Myb oligonucleotides in neuroblastoma [7, 34] and CRC [37]. The elevated expression of unmutated c-Myb in aggressive CRC combined with the tumor-dependent nature of the antigen provides an attractive immunotherapeutic target with greatly reduced potential for tumor escape either as a function of reduced antigen expression or the generation and presentation of mutated epitopes [22, 40]. Such mutation of target epitopes has been detected in p53 of chemically induced murine tumors leading to tumor escape [11], highlighting the benefit of targeting tumor-dependent target antigens such as c-Myb.

DNA vaccination is a powerful and inexpensive modality capable of generating antigen-specific immunity [42]. In addition, DNA vaccine design is very flexible and can draw upon the vast increase in genomic knowledge over the past two decades. Unlike foreign pathogens, tumor antigens, such as c-Myb, are “self” and weakly immunogenic due to immune tolerance. Nevertheless, DNA fusion vaccines that incorporate immunoenhancer elements can break peripheral tolerance by associative recognition, a process whereby a dominant epitope on a fusion protein enhances the response to other epitopes [18] with weak affinity. Two such immunoenhancer elements are the tetanus toxin peptides P2 and P30 [32, 49], which are non-toxic yet highly immunogenic and provide promiscuous Th help to the tumor antigen specific immune response. The promiscuous CD4+ Th help provided by these peptides operates via three mechanisms: (i) by enhancing both CD8+ CTL [1, 9] and CD4+ Th [18] responses to self antigens; (ii) providing the capacity for CD8+ T cell memory [23]; and (iii) by breaking tolerance to self antigens [18]. These peptides have been successfully used to provide T cell help to humoral immune responses targeting cell-surface tumor antigens [27, 39] or foreign pathogens [14, 16]. However, breaking tolerance to a shared antigen poses a concomitant risk of autoimmune pathology of endogenous tissues [51]. Although this danger exists, a number of preclinical and clinical studies have proved that vaccination protocols can generate anti-tumor immunity with little or no autoimmune disease [4, 20, 50].

The primary aim of this study was to determine the utility of c-Myb as a target for immunotherapy in CRC. To this end, we chose a DNA vaccination strategy to utilise active immunity with the potential for lasting T cell-mediated memory rather than repeated passive transfer of engineered immune cells and antibodies. Additionally, many DNA vaccination approaches targeting established tumor antigens, such as Her-2/neu in breast cancer, often co-express [33] or administer cytokines [10] or cytotoxic drugs [25] to develop combinatorial therapeutic strategies. To establish proof of principle of efficacy we conducted our study in the absence of immune adjuvants or cytotoxic agents. Here, we describe a DNA fusion vaccine comprising the proto-oncogene c-Myb and two tetanus toxin peptides, which provides CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated protection against subcutaneous CRC-growth in the absence of autoimmune pathology.

Materials and methods

Mice and cell lines

All mouse experiments were conducted in accordance with the animal experimental ethics committee guidelines of Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (East Melbourne, Australia). C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from ARC (Perth, Australia) with female mice 6–8 weeks of age used for all tumor injection experiments. The MC38 [12] adenocarcinoma cell line (kindly provided by Dr. Jeff Schlom, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and LIM1215 colon cancer cell line [52] were maintained in RPMI, supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum, penicillin, streptomycin and L-glutamine (Gibco) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Western blotting

Protein transfer, antibody protocols and anti-Myb antibodies Mab1.1 and 6.2 have been described previously [35]. Anti-Cox-2 and GRP78 goat polyclonal sera (Santa Cruz) were used at 1:500 and detected using donkey-anti-goat horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Santa Cruz) at 1:2,000. Mouse anti-pan-actin (ICN) C4 was used at 1:2,000 and detected using goat-anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase conjugate (BioRad) at 1:2,000. Bound antibody signal was detected by autoradiography using the NEN/Dupont Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit and Kodak XAR-5 film.

Construction of DNA fusion vaccines

DNA fusion vaccines were generated by amplification of target cDNA sequences in plasmid vectors using PCR primers containing promiscuous tetanus toxin Th epitopes P2 (QYIKANSKFIGITEL) and P30 (FNNFTVSFWLRVPKVSASHLE) [32].

P2-Myb-P30 sense primer: 5′-ctcgagatggcacagtatataaaagcaaattcta aatttataggtataactgaactagcaatggcccggagaccccgaca-3′

P2-Myb-P30 antisense primer: 5′-ctcgagtcattctaaatgactagcagatactttaggaaccctcaaccaaaagctaacggtaaaattattaaacatgaccagagttcgagctga-3′

P2-eGFP-P30 sense primer: 5′-ctcgagatggcacagtatataaaagcaaattcta aatttataggtataactgaagccatggccagcaaagga-3′

P2-eGFP-P30 antisense primer: 5′-caaagtggtgataattttaataatatttttaccgttagcttttggttgagggttcctaaagtatctgctagtcatttagaatgactcgag-3′.

Wild-type c-Myb cDNA (Ensembl Gene ID ENSMUSG00000019982) and enhanced GFP (eGFP) cDNA containing a nuclear localisation signal (NLS) (eGFP-N1, Clontech) were amplified to generate the P2-Myb-P30 and P2-eGFP-P30 DNA fusion genes, respectively. PCR products were ligated into the cloning vector pGEM-Teasy (Promega) and subsequently cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1V5HisTOPO/TA (Invitrogen). Wild-type c-Myb cDNA containing an N-terminal FLAG tag was cloned into pcDNA3.1V5HisTOPO/TA without tetanus peptides to generate the MybFLAG vaccine. For all vaccines, native stop codons were used to prevent the expression of the V5His fusion. DNA stocks were purified using Qiagen maxi-prep plasmid purification kits (Valencia, CA) and resuspended at 15 μg per 100 μl in sterile PBS for injection.

Expression of protein vaccines

Protein expression in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions was demonstrated by transient transfection of HEK293 cells and preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions by hypotonic lysis [35]. Expression of vaccine proteins was detected by Western blotting using anti-Myb (Mab 1.1 [35]) and anti-GFP (sc-8334, Santa Cruz) antibodies.

Mouse immunization and tumor challenge

Mice were vaccinated by tail vein injection with 15 μg of DNA in 100 μl of sterile PBS. Vaccination was performed one, two or three times at fortnightly intervals with a further 2 week interval prior to tumor challenge. MC38 cells for injection were harvested from culture plates, washed once and resuspended at 5 × 106 ml−1 or 5 × 107 ml−1 in serum-free RPMI to observe survival and tumor growth kinetics, respectively. Mice had their lower abdomen shaved the day prior to subcutaneous challenge with 5 × 105 or 5 × 106 MC38 cells in 100 μl of serum-free media, to observe survival and tumor growth kinetics, respectively. Tumor area measurements were taken using callipers and expressed as the product of two diameter measurements. All mice were euthanized when mean tumor area reached a maximum of 1.1 cm2 for control groups except in observation of survival in which individual mice were euthanized at 1.1 cm2.

In vivo depletion of immune cells

Six groups of mice (n = 8–10) were vaccinated twice with P2-Myb-P30 and challenged with MC38 by the standard protocol. Individual groups were then administered with antibodies by intraperitoneal injection to deplete CD4 (100 μg GK1.5, rat IgG2b) and/or CD8 (100 μg 53–6.7, rat IgG2a, Sigma) T cells or NK cells (20 μg anti-asialoGM1 antibody, Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) on days 0, 1 and 7 relative to tumor challenge. Control mice received a mock depletion by injection with 100 μg MAC-4 rat IgG2a (AFRC, Mac4). A further control group was vaccinated with P2-eGFP-P30 and received no antibody depletion.

Detection of specific P2-Myb-P30 vaccine-induced cytotoxic T cells

The cytolytic capacity of T cells from vaccinated mice was determined by 4-h 51Cr release assay, as described previously [13]. Prior to assay, splenic T cells were restimulated in co-culture with irradiated MC38 in media supplemented with 50 U/ml IL-2 for 4 days.

Analysis of peripheral blood

Peripheral blood was taken by retro-orbital eye bleed into 10 mM EDTA in PBS. Absolute white blood cell, platelet and hematocrit counts were performed on an Advia 120 Analyser (Bayer). Blood smears were prepared, fixed in methanol and stained with May-Grunwald (Amber Scientific MG-500) and Giemsa (GMSA-500). Differential white blood cell counts were performed by counting 100 consecutive cells for each blood smear.

Bone marrow stem cell colony assay

High and low proliferative potential colony-forming cells from femoral bone marrow of mice vaccinated three times were assayed in a double layer nutrient agar culture system as previously described [6].

Immunohistochemical staining of gastrointestinal crypts

For immunohistochemical and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, distal and proximal small intestine and colon sections were fixed in methacarn for 2 h, transferred to 70% ethanol, embedded and sectioned. Sections were stained for c-Myb using Mab1.1 and processed as described previously [41].

Flow cytometric analysis of T cell infiltrates, T cell activation status and MHC-I expression

Tumors from day 14 mice (n = 5–9) were digested with collagenase 4 (Worthington, NJ) in DMEM (Gibco) at 37°C for 30 min and passed through a sterile filter (40 μm) to remove cellular debris. Resultant suspensions were washed with FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FCS) and 106 cells stained in the presence of Fc receptor blocker 24G.2 for four-color staining analysis. Samples were analysed using a cytometer (FACS-LSR; Becton Dickinson) with viable cells gated by fluorogold exclusion (Invitrogen). The following antibodies were used: CD4-PE (L3T4, clone GK1.5; eBiosciences), CD8-APC (Ly.2, 53.6.7; eBioscience), CD62L-APC (MEL-14; eBioscience), CD44-FITC (Pgp-1, Ly-24; BD), MHC-I H-kb-biotin (AF6–88.5; BD), CD11b-PE (M1/70; eBioscience) and CD11c-biotin (HL3; BD). Secondary Streptavidin-PerCP (BD) was used in conjunction with MHC-I kb-biotin and CD11c-biotin.

Results

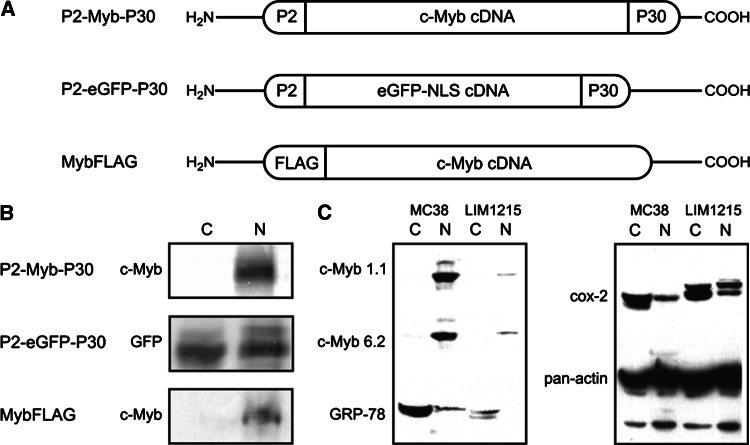

DNA vaccines encoding P2-Myb-P30, P2-eGFP-P30 and MybFLAG express nuclear localised fusion proteins

DNA vaccines P2-Myb-P30, P2-eGFP-P30 and MybFLAG (Fig. 1a) were successfully constructed using the pcDNA3.1V5HisTOPO/TA eukaryotic expression vector and DNA sequenced. Expression of P2-Myb-P30, P2-eGFP-P30 and MybFLAG vaccines was analysed by transfection into HEK293 cells and Western Blot with all expressed proteins of anticipated molecular weight calculated from the constituent proteins and peptides; P2-Myb-P30 80 kDa, P2-eGFP-P30 37.5 kDa and MybFLAG 75 kDa (Fig. 1b). All proteins were detected in the nuclear fraction (Fig. 1b) indicating that the nuclear localisation signal in P2-eGFP-P30 was operating as anticipated, allowing P2-eGFP-P30 to be used as a control vaccine for tetanus peptide-specific immune effects.

Fig. 1.

DNA fusion vaccine structure and expression in HEK293 cells. Schematic diagram indicating DNA fusion vaccine design (a). P2-Myb-P30 and P2-eGFP-P30 vaccines contain full-length cDNA flanked by the P2 and P30 tetanus toxin peptides. P2-eGFP-P30 contains full-length enhanced GFP cDNA with a nuclear localisation signal. MybFLAG vaccine contains full-length cDNA with a FLAG tag at the amino terminus. Vaccine sequences were cloned into the commercial eukaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1V5HisTOPO/TA. Expression of fusion proteins (b) in nuclear (N) and cytosolic (C) fractions of transiently transfected HEK293 by Western Blot using anti-c-MYB and anti-GFP antibodies. Expression of c-Myb and target genes GRP-78 and Cox-2 in MC38 and LIM1215 cells is shown with pan-actin serving as a loading control (c)

Colon adenocarcinoma cell line MC38 highly expresses c-Myb

The murine colon adenocarcinoma cell line MC38 has highly elevated c-Myb expression compared to the human HNPCC cell line LIM1215, as determined by Western Blot analysis (Fig. 1c), and both cell lines express substantially more c-Myb than normal colon mucosa [36]. c-Myb expression was measured using two different anti-Myb monoclonal antibodies; Mab 1.1 and Mab 6.2 and was restricted to the nuclear fraction (N) compared to the cytosol (C) as expected. c-Myb target gene protein expression; Cox-2 and GRP78 are also shown. Actin serves as a loading control. Given the high level expression of c-Myb in MC38 cells they were employed with the expectation that they would serve as a good immunotherapeutic target to use in this study.

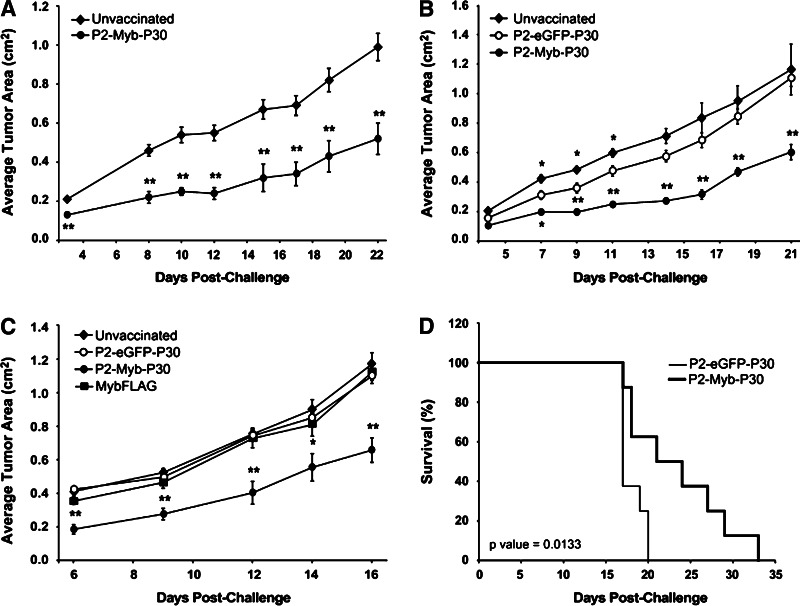

P2-Myb-P30 vaccination induces protective immunity

In general, DNA vaccination protocols in preclinical mouse tumor models have used three vaccinations in a prime-boost-boost regimen to generate maximal anti-tumor immunity [28, 39]. In order to test the requirement for multiple vaccinations and identify minimal effective dosage we performed three experiments using one, two or three vaccinations as described in “Materials and methods”. For these experiments we chose the mouse colon carcinoma cell line MC38 which grows aggressively in syngeneic mice as a subcutaneous tumor and expresses high levels of c-Myb as shown in Fig. 1c. We demonstrated significant suppression of MC38 tumor growth in P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice compared to unvaccinated control mice irrespective of the number of booster vaccinations (Fig. 2a–c). This result indicated that a single vaccination was sufficient for induction of immunity.

Fig. 2.

P2-Myb-P30 vaccination induces marked c-Myb-specific anti-tumor immunity with a single vaccination. Mice were vaccinated once (a, d), twice (b) or three times (c) prior to challenge with MC38 cells. The figures show the average tumor area over the course of the experiment (a-c) or survival (d). The number of animals used per cohort was 5 (a), 6 (b), 10 (c) and 8 (d). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 for P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice by Student’s t test as compared with unvaccinated mice (a) or P2-eGFP-P30 vaccinated mice (b–d). Error bars are SEM

We made use of three control groups to identify the specificity of P2-Myb-P30 immunity for c-Myb. First, an unvaccinated group set a baseline tumor growth rate in the absence of immunity. Second, tetanus peptide specific effects were controlled by linking the peptides to a nuclear antigen not expressed by the host animal (P2-eGFP-P30) and hence, were unable to generate anti-tumor immunity. This vector constitutes an ideal negative control as P2-eGFP-P30 retains all the features of P2-Myb-P30 with the exception of the exchanged nuclear antigen. Third, the requirement for the P2 and P30 peptides to break tolerance against c-Myb was addressed with the MybFLAG control vaccine, which lacks both peptides. Cohorts vaccinated with either the P2-eGFP-P30 or MybFLAG vaccines overall demonstrated no significant tumor protection and were comparable with unvaccinated mice when delivered in a three-vaccination protocol (Fig. 2c). However there was some anti-tumor effect by the P2-eGFP-P30 vaccine between days 7 and 11 following two vaccinations (Fig. 2b), which may be due to some induction of innate immunity as a consequence of CpG motifs in the plasmid backbone. By contrast, the P2-Myb-P30 vaccine induced marked and significant anti-tumor immunity when compared to all three control groups suggesting that the immune response is both specific for c-Myb and dependent on the presence of the P2 and P30 tetanus peptides to break tolerance (Fig. 2a–c). Furthermore, a single P2-Myb-P30 vaccination was sufficient to significantly improve survival of MC38 inoculated mice (Fig. 2d).

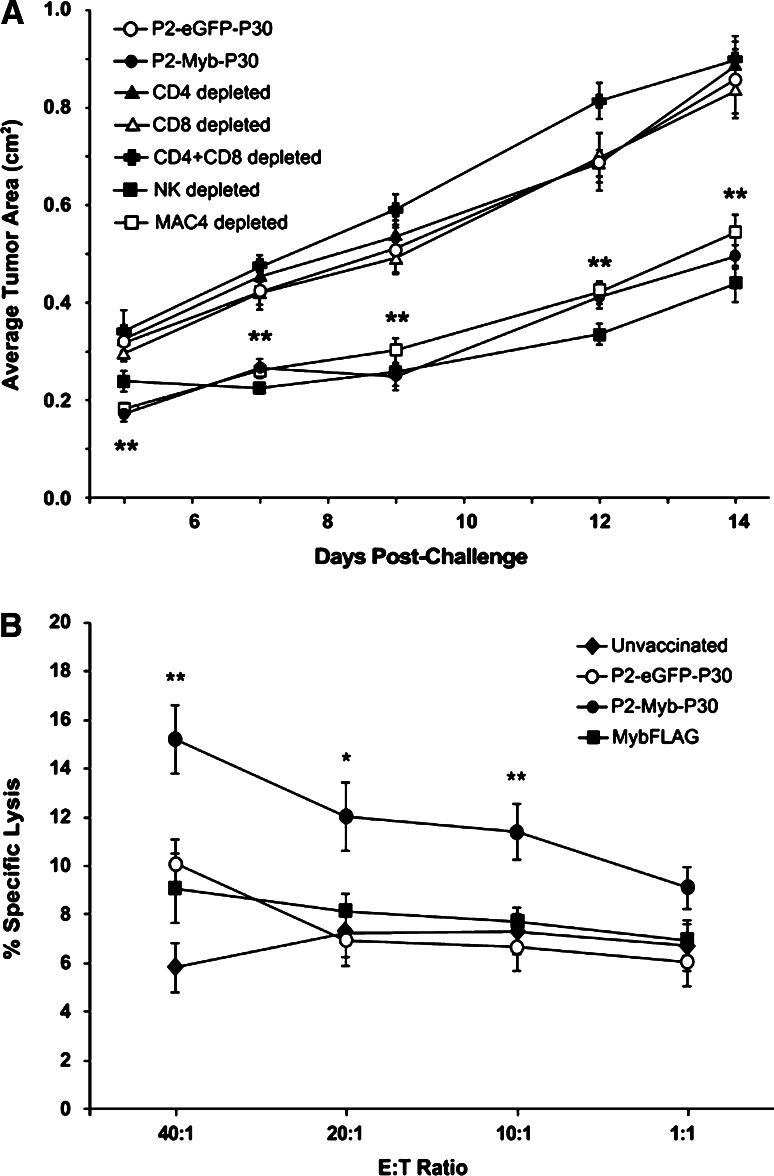

Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are essential for mediating P2-Myb-P30 induced immunity

To identify the specific immune T cell subsets involved in the anti-tumor immune response we performed in vivo depletion experiments. Groups of P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice were treated with MAC-4 control antibody (rat IgG) or antibodies to deplete CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells or NK cells and then challenged subcutaneously with 5 × 106 MC38 tumor cells. As demonstrated previously in Fig. 2, mice vaccinated with P2-Myb-P30 suppressed MC38 tumor growth. By contrast, depletion of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells completely removed protection resulting in tumor growth similar to the P2-eGFP-P30 control group (Fig. 3a). Depletion of NK cells or MAC-4 depleted control mice showed a similar anti-tumor response to P2-Myb-P30 treated mice. Taken together, these data indicate essential roles for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but not for NK cells, in the effector phase of the anti-tumor immune response elicited by P2-Myb-P30 immunisation.

Fig. 3.

P2-Myb-P30 induced anti-tumor immunity is c-Myb specific and mediated by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Mice (n = 8–10) were vaccinated twice with P2-Myb-P30 and selectively depleted of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells or NK cells as indicated. A P2-eGFP-P30 vaccinated group was used as a control for unprotected tumor growth (a). Splenocytes from mice (n = 5) vaccinated twice with P2-Myb-P30, P2-eGFP-P30 and MybFLAG or unvaccinated were used to perform a 4-h51Cr release assay. MC38 target cells were used at a range of E:T ratios and mean percent specific lysis was calculated (b). *p = 0.05, **p = 0.01 for P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice by Student’s t test as compared with P2-eGFP-P30 vaccinated mice. Error bars are SEM

Vaccination generates MC38 specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a P2-Myb-P30 dependent manner

To confirm the generation of T cell-mediated immunity targeting MC38 cells, restimulated splenocytes from P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice were used to perform a 4-h 51Cr release assay with MC38 target cells. A modest but significant increase in specific lysis was seen in P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice compared to all other cohorts (Fig. 3b) indicating the generation of MC38 specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in a P2-Myb-P30 vaccine dependent manner.

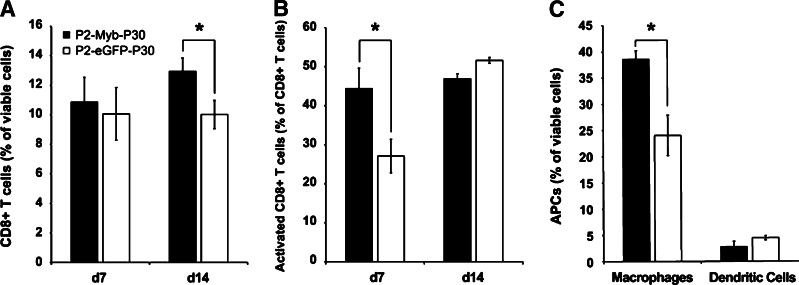

Number and activation state of immune effector cell infiltrates are increased by P2-Myb-P30 vaccination

The number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and APC tumor infiltrates and T cell activation status were determined by flow cytometry. Tumors from mice vaccinated twice were analysed at days 7 and 14 to represent maximal anti-tumor activity and progressively growing tumors, respectively. CD8+ T cell tumor infiltrates from P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice demonstrated increased activation (Fig. 4b) at d7 and a significant increase in numbers at d14 (Fig. 4a). Additionally, a general increase in CD8+ T cell activation status (CD44+, CD62Llow) was observed from d7 to d14 irrespective of treatment (Fig. 4b). P2-Myb-P30 vaccination also led to an increase in macrophage (CD11b+, CD11c−) infiltrate in d7 tumors although dendritic cells (DCs) (CD11b+, CD11c−) were unaffected (Fig. 4c). Surprisingly, given the impact of immunity observed in our depletion studies, CD4+ T cell infiltrate numbers and activation status were unchanged (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

P2-Myb-P30 vaccination increases both CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration and activation and macrophage tumor infiltration. Mice (n = 6–9) were vaccinated twice with P2-Myb-P30 and tumors analysed by FACS for T cell (a) and macrophage (c) infiltration and T cell activation (b) status at days 7 and 14 post-tumor challenge. *p ≤ 0.05 by Student’s t test as compared with P2-eGFP-P30 vaccinated mice. Error bars are SEM

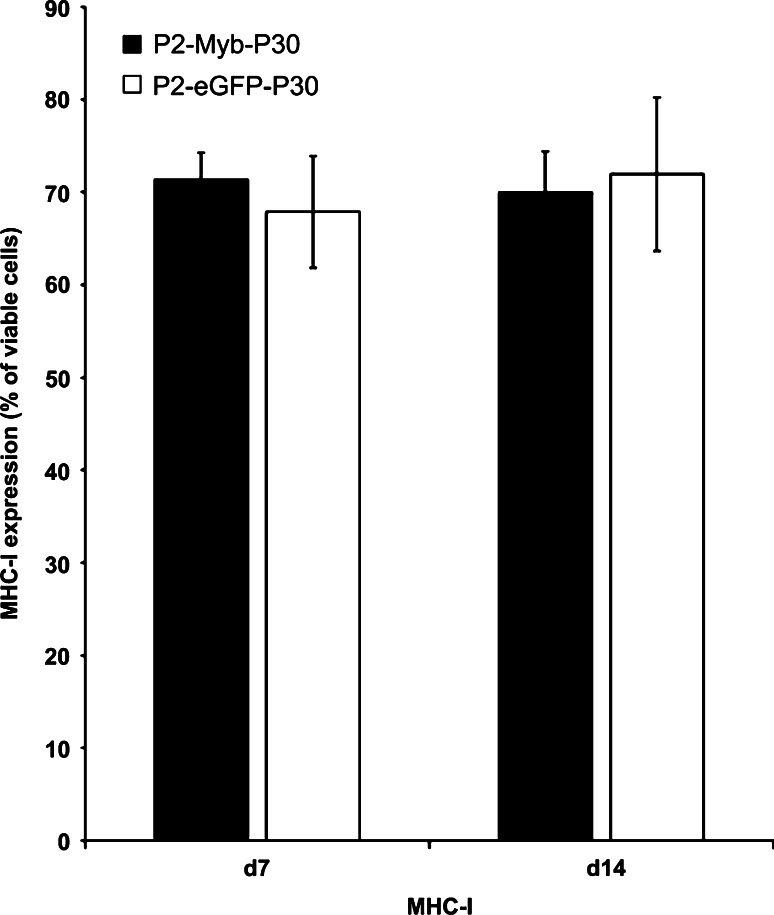

Down-regulation of MHC-I expression as a mechanism of tumor escape is not detected following P2-Myb-P30 vaccination

Our data demonstrated that P2-Myb-P30 vaccination led to a significant slowing in tumor growth kinetics followed by progressive outgrowth at greater tumor volumes. To determine if reduced MHC-I expression by progressively growing MC38 tumors perhaps leads to reduced peptide presentation and hence, reduced immune targeting, MHC-I expression on progressing MC38 tumors was determined by flow cytometry. Our results demonstrated no difference in MHC-I expression in d7 or d14 tumors from P2-Myb-P30 and P2-eGFP-P30 vaccinated cohorts (Fig. 5). These results suggested that factors other than down-regulated MHC-I expression allow the progressive growth of tumors from P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated cohorts.

Fig. 5.

P2-Myb-P30 vaccination does not lead to selection of reduced MHC-I expression in progressively growing tumors. Mice (n = 5–7) were vaccinated twice with P2-Myb-P30 and tumors analysed by FACS for MHC-I expression at days 7 and 14 post-challenge. Error bars are SEM

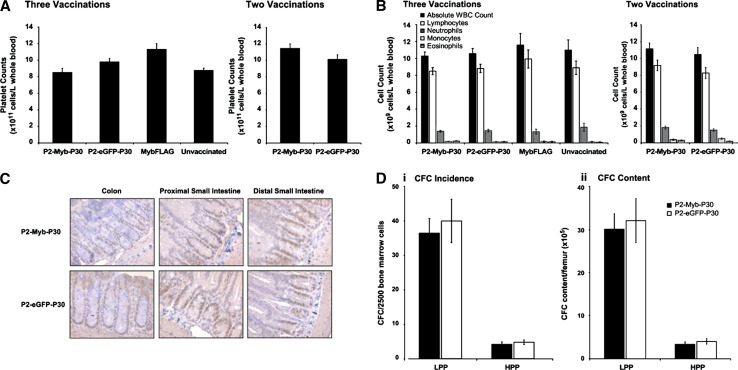

P2-Myb-P30 vaccination does not generate any detectable autoimmunity in endogenous c-Myb expressing tissues

Expression of c-Myb is required for the development and maintenance of a number of normal tissues and as a consequence, immune targeting of this self-antigen poses the potential risk of autoimmune disease. To observe the presence and severity of any autoimmune disease as a consequence of breaking immune tolerance to c-Myb, we analysed three c-Myb expressing compartments following vaccination. This comprised of analysis of (1) cell numbers in peripheral blood, (2) stem and progenitor cell proliferative capacity in bone marrow (BM) and (3) c-Myb expression and length of gastrointestinal crypts. Analysis of peripheral blood showed no significant difference between P2-Myb-P30 and all control cohorts in platelet count (Fig. 6a), percentage hematocrit (data not shown) or white blood cell counts (Fig. 6b) indicating an absence of any detectable autoimmunity in this compartment. Evidence for immune targeting of c-Myb expressing stem cells in gastrointestinal crypts was analysed by immunohistochemical staining for c-Myb and analysis of crypt length. Comparison of P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice to the P2-eGFP-P30 control group indicated no reduction in either the number or intensity of cells stained with c-Myb in crypts of all three lower GI sections analysed (Fig. 6c). Finally, to assess potential autoimmune targeting of c-Myb expressing stem and progenitor cells in the femoral BM, we employed a surrogate assay to observe the status of high proliferation potential-colony forming cells (HPP-CFC) and low proliferation potential colony forming cell (LPP-CFC), respectively [1]. In a result analogous to differentiated hemopoietic cells in peripheral blood, P2-Myb-P30 vaccination had no significant effect on either incidence or total content of both high (HPP) and low (LPP) proliferative capacity cells in bone marrow (Fig. 6d i, ii). Taken together, data from the analysis of three well-characterised c-Myb expressing tissues clearly demonstrated the absence of any detectable autoimmunity following P2-Myb-P30 vaccination.

Fig. 6.

No autoimmune disease was observed in peripheral blood, gastrointestinal crypts or bone marrow of P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice. Peripheral blood from mice vaccinated twice or three times with P2-Myb-P30 as indicated was analysed for platelets (a) and white blood cells (b). Gastrointestinal crypts from mice vaccinated three times were stained for c-Myb and counterstained with Carrazzi’s hematoxylin to observe c-Myb expression (c). Bone marrow from mice (n = 5) vaccinated three times with P2-Myb-P30 were plated under conditions that allow colony formation of cells with low proliferative potential (LPP) and high proliferative potential (HPP) per 25,000 plated cells (i) or per femur (ii) (d). Error bars are SEM

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated efficacy of a P2-Myb-P30 vaccine design in breaking peripheral tolerance and generating effective T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity. Unlike cell-surface antigens [39], adaptive immune responses are limited to cellular immunity when targeting intracellular antigens such as c-Myb, which are not available to the humoral arm of the immune system. To maximise the provision of Th help to c-Myb epitopes we designed the P2-Myb-P30 vaccine to contain both the P2 and P30 peptides at the N and C-termini, respectively. The full-length c-Myb cDNA was incorporated to maximise the number of available c-Myb epitopes, as evidence of immunoediting has been observed as a mechanism of tumor escape using single or restricted epitope vaccines [44]. Vaccine efficacy was assayed in a highly aggressive and weakly immunogenic [48], subcutaneous model of colon cancer (MC38), which expresses elevated c-Myb. This model system used a challenge dosage of MC38 cells considerably higher than published models [21, 46] to ensure complete tumor “take”, and provided very rapid and aggressive tumor progression.

Prophylactic vaccination with naked P2-Myb-P30 DNA effectively and significantly reduced tumor growth demonstrating the ability of the vaccine to induce anti-tumor immunity in the absence of exogenous cytokines or other adjuvants. The extent of protection was similar regardless of vaccination number, a result in contrast with standard vaccination methodology, which routinely employs booster vaccinations. This lack of requirement for booster vaccinations is indicative of the efficacy of the vaccine in achieving anti-tumor activity. To observe the mechanism of vaccine action and provide evidence for the specificity of anti-tumor immunity for c-Myb two control vaccines were used. A MybFLAG vaccine, which lacks both Th epitopes conferred no anti-tumor protection and confirmed the tetanus peptides as essential vaccine components. This result also served to highlight the weak immunogenicity of c-Myb cDNA and, by extension, the endogenous antigen. To address the specificity of the immune response for c-Myb, we employed a second control vaccine in which the cDNA of a foreign nuclear antigen (GFP-NLS) was substituted for c-Myb in the P2-Myb-P30 vaccine. The lack of anti-tumor activity provided by the P2-eGFP-P30 vaccine suggests that the antitumor immunity generated by the P2-Myb-P30 vaccine is c-Myb specific. In Addition, circumstantial evidence for c-Myb specificity was provided by an in vitro 51Cr release assay in which specific lysis of MC38 tumor target cells increased with effector CTL derived from P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice, compared to control cohorts.

In vivo depletion of T cells identified both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as essential mediators of immunity following P2-Myb-P30 vaccination. These results indicate the success of the vaccine design in generating cell-mediated, anti-tumor immunity targeting the c-Myb overexpressing CRC cell line MC38, through the activation of both CTL and Th responses. Analysis of immune infiltrates at the tumor site identified a significant increase in both the activation (d7) and number (d14) of CD8+ T cells and macrophages (d7) in P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice. This increased infiltration of immune effector cells correlated with the anti-tumor activity of the P2-Myb-P30 vaccine. It is unclear at this stage why there was no apparent change in activation state or numbers of CD4+ tumor infiltrate. Nevertheless our depletion studies confirmed an important role for these cells. The importance of immune cell infiltration in CRC prognosis was highlighted by two recent clinical studies; in humans, T cell tumor infiltration was a superior prognostic indicator compared to Duke’s histopathological staging [17] and, increased macrophage infiltration in CRC correlates with improved prognosis [15].

In this study the anti-tumor immunity of the P2-Myb-P30 vaccine significantly slowed tumor growth kinetics although tumors were not arrested and continued to grow progressively. This may be due to an intrinsic quality of the vaccine and model system and/or a result of tumor escape. Mechanisms by which tumors may escape immune surveillance are many and operate by the selection of resistant tumor cells, termed immunoediting [45]. One important example of this is downregulation of MHC-I, which leads to reduced peptide presentation by tumors and the potential for avoidance of immune targeting. Interestingly, analysis of MHC-I expression by d7 and d14 tumors demonstrated that P2-Myb-P30 vaccination did not lead to down-regulation as a consequence of selective pressure. This result provides a basis for improved vaccine design, and administration regimes to augment anti-tumor efficacy.

Targeting of self, tumor antigens by breaking tolerance is a “double edged sword” with the risk of autoimmune disease counter balancing the benefits of anti-tumor immunity. Expression of c-Myb can be detected in the stem and progenitor cells of a number of endogenous tissues and disruption of this expression has severe deleterious effects on tissue integrity [29]. Consequently, potential immune targeting of these cells poses a significant risk to patient welfare. To address this concern, gastrointestinal crypts, peripheral blood and bone marrow from P2-Myb-P30 vaccinated mice were analysed for signs of autoimmune disease. Progenitor cells in gastrointestinal crypts of the proximal and distal small intestine and colon showed normal c-Myb expression with both cell numbers and morphology identical to controls. Furthermore, overall crypt and villus morphology were unaffected by vaccination indicating a lack of detectable autoimmune disease. In peripheral blood, platelet numbers and differential white blood cell counts showed no significant difference between vaccinated and control mice. Elevated platelet counts are an early marker of disrupted c-Myb expression, as identified in c-Myb hypomorph mice [8]. To further extend the analysis, we studied the proliferative capacity of stem and progenitor cells in femoral bone marrow. This compartment comprises a population of c-Myb expressing cells, which represent the most stringent analysis of autoimmunity due to the high sensitivity of these cells to stress. Neither CFC incidence nor content of stem and progenitor cells was significantly affected by P2-Myb-P30 vaccination. Taken together, these results indicated that effective anti-tumor immunity might be uncoupled from autoimmune disease. This finding is in accordance with the majority of DNA vaccination studies targeting self antigens [20], with few exceptions including targeting of TRP1 in melanoma, which resulted in vitiligo [31] as a consequence of melanocyte destruction. There is growing evidence that the differential immune targeting of tumor and endogenous tissues may be a result of related but not identical processes [4, 26] offering the prospect that autoimmune disease is not an irrevocably linked side effect of vaccination targeting self, tumor antigens.

The potential clinical applications of c-Myb DNA vaccination include both prophylactic and therapeutic administration. A common proposal for cancer vaccines in general is the treatment of residual disease after surgical resection of the primary tumor, an application not addressed in our study due to limitations of the model. A more recent proposed application is chemoprevention [26], an approach recommended by the refractory response of many advanced stage cancers to conventional treatments. CRC fits the criteria for chemoprevention as it has high prevalence, mortality and morbidity rates coupled with a long transition from pre-malignant lesion (adenoma) to malignant disease [1]. Patients identified with colorectal adenomas through screening programs may be prophylactically vaccinated to target markers of advanced and/or aggressive disease [26] such as c-Myb to guard against disease progression.

The results of this study demonstrated that a c-Myb DNA vaccine could break peripheral tolerance and generate effective, cell-mediated, anti-tumor immunity targeting a model of CRC which over-expresses c-Myb. Additionally, significant reduction in tumor growth rate was achieved in the absence of combinatorial therapy with cytotoxic drugs or immune adjuvants. Nevertheless, further optimisation of anti-tumor efficacy may be achieved by co-administration of immunostimulatory and/or cytotoxic reagents or refined vaccine delivery regimes. Here we have provided proof of principle upon which this approach may be further developed with a view to clinical application in CRC and other malignancies with elevated c-Myb expression.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and thank the following people for their expert critical input and technical assistance without whom this work would have not been possible; Sally Lightowler, Dr. Jordane Malaterre, Seb Dworkin, Dani Cardozo, Kym Stanley, Mira Liu, Carol Van Puyenbroek, Ralph Rossi, Dr. Jeremy Swann and Duy Huynh. The National Health and Medical Research Council have supported this work and RGR and PKD are the recipients of NHMRC Research Fellowships from this organization.

Footnotes

Phillip K. Darcy and Robert G. Ramsay contributed equally as senior authors.

References

- 1.Arber N, Levin B. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer: ready for routine use? Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:517–525. doi: 10.2174/1568026054201659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertoncello I, Bradford G, Williams B. Surrogate assays for hematopoietic stem cell activity. In: Garand J, Quesenberg P, Hilton D, editors. Colony-stimulating factors, 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biroccio A, Benassi B, D’Agnano I, D’Angelo C, Buglioni S, Mottolese M, Ricciotti A, Citro G, Cosimelli M, Ramsay RG, Calabretta B, Zupi G. c-Myb and Bcl-x overexpression predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer: clinical and experimental findings. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1289–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowne WB, Srinivasan R, Wolchok JD, Hawkins WG, Blachere NE, Dyall R, Lewis JJ, Houghton AN. Coupling and uncoupling of tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1717–1722. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brabender J, Lord RV, Danenberg KD, Metzger R, Schneider PM, Park JM, Salonga D, Groshen S, Tsao-Wei DD, DeMeester TR, Holscher AH, Danenberg PV. Increased c-myb mRNA expression in Barrett’s esophagus and Barrett’s-associated adenocarcinoma. J Surg Res. 2001;99:301–306. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford GB, Williams B, Rossi R, Bertoncello I. Quiescence, cycling, and turnover in the primitive hematopoietic stem cell compartment. Exp Hematol. 1997;25:445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brignole C, Pastorino F, Marimpietri D, Pagnan G, Pistorio A, Allen TM, Pistoia V, Ponzoni M. Immune cell-mediated antitumor activities of GD2-targeted liposomal c-myb antisense oligonucleotides containing CpG motifs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1171–1180. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpinelli MR, Hilton DJ, Metcalf D, Antonchuk JL, Hyland CD, Mifsud SL, Di Rago L, Hilton AA, Willson TA, Roberts AW, Ramsay RG, Nicola NA, Alexander WS. Suppressor screen in Mpl-/- mice: c-Myb mutation causes supraphysiological production of platelets in the absence of thrombopoietin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6553–6558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401496101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassell D, Forman J. Linked recognition of helper and cytotoxic antigenic determinants for the generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;532:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb36325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang SY, Lee KC, Ko SY, Ko HJ, Kang CY. Enhanced efficacy of DNA vaccination against Her-2/neu tumor antigen by genetic adjuvants. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:86–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cicinnati VR, Dworacki G, Albers A, Beckebaum S, Tuting T, Kaczmarek E, DeLeo AB. Impact of p53-based immunization on primary chemically-induced tumors. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:961–970. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbett TH, Griswold DP, Jr, Roberts BJ, Peckham JC, Schabel FM., Jr Tumor induction relationships in development of transplantable cancers of the colon in mice for chemotherapy assays, with a note on carcinogen structure. Cancer Res. 1975;35:2434–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darcy PK, Kershaw MH, Trapani JA, Smyth MJ. Expression in cytotoxic T lymphocytes of a single-chain anti-carcinoembryonic antigen antibody. Redirected Fas ligand-mediated lysis of colon carcinoma. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1663–1672. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1663::AID-IMMU1663>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan AF, Blackman MJ, Kaslow DC. Vaccine efficacy of recombinant Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein 1 in malaria-naive, -exposed, and/or -rechallenged Aotus vociferans monkeys. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1418–1427. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1418-1427.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forssell J, Oberg A, Henriksson M, Stenling R, Jung A, Palmqvist R. High macrophage infiltration along the tumor front correlates with improved survival in colon cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1472–1479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fryauff DJ, Mouzin E, Church LW, Ratiwayanto S, Hadiputranto H, Sutamihardja MA, Widjaja H, Corradin G, Subianto B, Hoffman SL. Lymphocyte response to tetanus toxin T-cell epitopes: effects of tetanus vaccination and concurrent malaria prophylaxis. Vaccine. 1999;17:59–63. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerloni M, Xiong S, Mukerjee S, Schoenberger SP, Croft M, Zanetti M. Functional cooperation between T helper cell determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13269–13274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230429197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg RM. Therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2006;11:981–987. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-9-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greiner JW, Zeytin H, Anver MR, Schlom J. Vaccine-based therapy directed against carcinoembryonic antigen demonstrates antitumor activity on spontaneous intestinal tumors in the absence of autoimmunity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6944–6951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo ZS, Naik A, O’Malley ME, Popovic P, Demarco R, Hu Y, Yin X, Yang S, Zeh HJ, Moss B, Lotze MT, Bartlett DL. The enhanced tumor selectivity of an oncolytic vaccinia lacking the host range and antiapoptosis genes SPI-1 and SPI-2. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9991–9998. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haupt K, Roggendorf M, Mann K. The potential of DNA vaccination against tumor-associated antigens for antitumor therapy. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002;227:227–237. doi: 10.1177/153537020222700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen EM, Lemmens EE, Wolfe T, Christen U, von Herrath MG, Schoenberger SP. CD4+ T cells are required for secondary expansion and memory in CD8+ T lymphocytes. Nature. 2003;421:852–856. doi: 10.1038/nature01441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko HJ, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Chang WS, Ko SY, Chang SY, Sakaguchi S, Kang CY. A combination of chemoimmunotherapies can efficiently break self-tolerance and induce antitumor immunity in a tolerogenic murine tumor model. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7477–7486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lollini PL, Cavallo F, Nanni P, Forni G. Vaccines for tumour prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:204–216. doi: 10.1038/nrc1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund LH, Andersson K, Zuber B, Karlsson A, Engstrom G, Hinkula J, Wahren B, Winberg G. Signal sequence deletion and fusion to tetanus toxoid epitope augment antitumor immune responses to a human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) plasmid DNA vaccine in a murine test system. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:365–376. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo Y, Zhou H, Mizutani M, Mizutani N, Reisfeld RA, Xiang R. Transcription factor Fos-related antigen 1 is an effective target for a breast cancer vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8850–8855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1033132100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malaterre J, Carpinelli M, Ernst M, Alexander W, Cooke M, Sutton S, Dworkin S, Heath JK, Frampton J, McArthur G, Clevers H, Hilton D, Mantamadiotis T, Ramsay RG. c-Myb is required for progenitor cell homeostasis in colonic crypts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3829–3834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610055104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mucenski ML, McLain K, Kier AB, Swerdlow SH, Schreiner CM, Miller TA, Pietryga DW, Scott WJ, Jr, Potter SS. A functional c-myb gene is required for normal murine fetal hepatic hematopoiesis. Cell. 1991;65:677–689. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90099-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overwijk WW, Lee DS, Surman DR, Irvine KR, Touloukian CE, Chan CC, Carroll MW, Moss B, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Vaccination with a recombinant vaccinia virus encoding a “self” antigen induces autoimmune vitiligo and tumor cell destruction in mice: requirement for CD4(+) T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2982–2987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panina-Bordignon P, Tan A, Termijtelen A, Demotz S, Corradin G, Lanzavecchia A. Universally immunogenic T cell epitopes: promiscuous binding to human MHC class II and promiscuous recognition by T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:2237–2242. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830191209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pannellini T, Spadaro M, Di Carlo E, Ambrosino E, Iezzi M, Amici A, Lollini PL, Forni G, Cavallo F, Musiani P. Timely DNA vaccine combined with systemic IL-12 prevents parotid carcinomas before a dominant-negative p53 makes their growth independent of HER-2/neu expression. J Immunol. 2006;176:7695–7703. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pastorino F, Brignole C, Marimpietri D, Di Paolo D, Zancolli M, Pagnan G, Ponzoni M. Targeted delivery of oncogene-selective antisense oligonucleotides in neuroectodermal tumors: therapeutic implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1028:90–103. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramsay RG, Ishii S, Nishina Y, Soe G, Gonda TJ. Characterization of alternate and truncated forms of murine c-myb proteins. Oncogene Res. 1989;4:259–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramsay RG, Thompson MA, Hayman JA, Reid G, Gonda TJ, Whitehead RH. Myb expression is higher in malignant human colonic carcinoma and premalignant adenomatous polyps than in normal mucosa. Cell Growth Differ. 1992;3:723–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramsay RG, Barton AL, Gonda TJ. Targeting c-Myb expression in human disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2003;7:235–248. doi: 10.1517/14728222.7.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramsay RG. c-Myb a stem-progenitor cell regulator in multiple tissue compartments. Growth Factors. 2005;23:253–261. doi: 10.1080/08977190500233730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renard V, Sonderbye L, Ebbehoj K, Rasmussen PB, Gregorius K, Gottschalk T, Mouritsen S, Gautam A, Leach DR. HER-2 DNA and protein vaccines containing potent Th cell epitopes induce distinct protective and therapeutic antitumor responses in HER-2 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:1588–1595. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenthal MA, Thompson MA, Ellis S, Whitehead RH, Ramsay RG. Colonic expression of c-myb is initiated in utero and continues throughout adult life. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:961–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stevenson FK, Ottensmeier CH, Johnson P, Zhu D, Buchan SL, McCann KJ, Roddick JS, King AT, McNicholl F, Savelyeva N, Rice J. DNA vaccines to attack cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(Suppl 2):14646–14652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404896101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su AI, Welsh JB, Sapinoso LM, Kern SG, Dimitrov P, Lapp H, Schultz PG, Powell SM, Moskaluk CA, Frierson HF, Jr, Hampton GM. Molecular classification of human carcinomas by use of gene expression signatures. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7388–7393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun W, Qian H, Zhang X, Zhou C, Liang X, Wang D, Fu M, Ma W, Zhang S, Lin C. Induction of protective and therapeutic antitumour immunity using a novel tumour-associated antigen-specific DNA vaccine. Immunol Cell Biol. 2006;84:440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2006.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swann JB, Smyth MJ. Immune surveillance of tumors. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1137–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka F, Yamaguchi H, Ohta M, Mashino K, Sonoda H, Sadanaga N, Inoue H, Mori M. Intratumoral injection of dendritic cells after treatment of anticancer drugs induces tumor-specific antitumor effect in vivo. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:265–269. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson MA, Rosenthal MA, Ellis SL, Friend AJ, Zorbas MI, Whitehead RH, Ramsay RG. c-Myb down-regulation is associated with human colon cell differentiation, apoptosis, and decreased Bcl-2 expression. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5168–5175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tirapu I, Huarte E, Guiducci C, Arina A, Zaratiegui M, Murillo O, Gonzalez A, Berasain C, Berraondo P, Fortes P, Prieto J, Colombo MP, Chen L, Melero I. Low surface expression of B7–1 (CD80) is an immunoescape mechanism of colon carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2442–2450. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valmori D, Pessi A, Bianchi E, Corradin G. Use of human universally antigenic tetanus toxin T cell epitopes as carriers for human vaccination. J Immunol 1992. 1992;149:717–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Elsas A, Sutmuller RP, Hurwitz AA, Ziskin J, Villasenor J, Medema JP, Overwijk WW, Restifo NP, Melief CJ, Offringa R, Allison JP. Elucidating the autoimmune and antitumor effector mechanisms of a treatment based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 blockade in combination with a B16 melanoma vaccine: comparison of prophylaxis and therapy. J Exp Med. 2001;194:481–489. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber LW, Bowne WB, Wolchok JD, Srinivasan R, Qin J, Moroi Y, Clynes R, Song P, Lewis JJ, Houghton AN. Tumor immunity and autoimmunity induced by immunization with homologous DNA. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1258–1264. doi: 10.1172/JCI4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitehead RH, Macrae FA, St John DJ, Ma J. A colon cancer cell line (LIM1215) derived from a patient with inherited nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;74:759–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]