Abstract

The discovery of tumour antigens recognized by T cells and the features of immune responses directed against them has paved the way to a multitude of clinical studies aimed at boosting anti-tumour T cell immunity as a therapeutic tool for cancer patients. One of the different strategies explored to ameliorate the immunogenicity of tumour antigens in vaccine protocols is represented by the use of optimized peptides or altered peptide ligands, whose amino acid sequence has been modified for improving HLA binding or TCR interaction with respect to native epitopes. However, despite the promising results achieved with preclinical studies, the clinical efficacy of this approach has not yet met the expectations. Although multiple reasons could explain the relative failure of altered peptide ligands as more effective cancer vaccines, the possibility that T cells primed by modified tumour peptides might may be unable to effectively cross-recognize tumour cells has not been sufficiently addressed. Indeed, the introduction of conservative amino acid substitutions may still produce diverse and unpredictable changes in the HLA/peptide interface, with consequent modifications of the TCR repertoire that can interact with the complex. This could lead to the expansion of a broad array of T cells whose TCRs may not necessarily react with equivalent affinity with the original antigenic epitope. Considering the results presently achieved with this vaccine approach, and the emerging availability of alternative strategies for boosting anti-tumour immunity, the use of modified tumour peptides could be reconsidered.

Keywords: Superagonist analogues, Heteroclytic peptides, Active immunotherapy, Melanoma, Colo-rectal carcinoma

The use of optimized tumour peptides for enhancing anti-tumour immunity

Although several groups have reported that relevant clinical responses can be obtained in a selected subset of patients using active immunization, anti-tumour vaccines have not so far reached the expected therapeutic success [1, 2]. Multiple causes have been blamed responsible for this limited efficacy, ranging from tumour escape mechanisms to regulatory and suppressive pathways present in tumour-bearing host [3]. However, several evidences suggest that anti-tumour vaccines generally produce the in vivo expansion of low avidity T cells lacking the immunological properties required for a full-fledged tumour rejection. Although high avidity T cells reacting with self tumour antigens such as Melan-A/Mart-1 have been described to persist in peripheral circulation [4], low affinity seems to be a hallmark of anti-tumour T cells, resulting from the depletion of high affinity self-reacting TCRs during thymic selection [5, 6]. Low-affinity anti-tumour T cells are then kept under control by different mechanisms of peripheral tolerance [7], further maintained by immunosuppressive pathways set up by tumour cells in bearing hosts [8].

Indeed, evidence is available to indicate that T cells directed to tumour-expressed self epitopes are rarely engaged in a full-fledged auto-aggressive response, stemming from a true breach of tolerance during spontaneous anti-tumour immune responses. However, break of tolerance could still be achieved by immunizing with antigenic determinants provided in an optimized form. Studies focused on the molecular requirements for TCR engagement during immune responses in general, and autoimmunity in particular, have led to a better appreciation of the factors that contribute to a sustained and effective immunity. Several such studies indicate that qualities of the peptide ligand itself can significantly impact the quality of initiated or existing responses, by providing optimal stimuli that ultimately improve the functional and proliferative capacities of T cells [9–12].

One potential strategy for achieving this goal is thus represented by modified or optimized peptides, also defined as altered peptide ligands (APL). Thanks to the introduction of amino acid substitutions in the anchor residues, these epitopes display higher affinity of binding to HLA class I molecules, thus creating a complex that can interact more efficiently with the cognate TCR. Examples of these optimized epitopes are the MelanA/Mart-1 decamer 26-35 2L [13] and the gp100 209/2M [14], representing the most commonly used epitopes for melanoma vaccines [1]. Alternatively, peptides can also be optimized at their TCR contact interface by inserting amino acid substitutions in the TCR contact residues. Examples of these peptides, also known as superagonists, are the peptide analogue of CEA CAP1-6D, widely utilized in the immunization of patients with CEA-expressing cancers [15, 16], or the singly-substituted 1L-variant analogue of the MART127–35 peptide [17]. It should be noted that all the optimized tumour peptides described and tested in clinical setting so far are HLA-class I-restricted and thus designed to optimized CD8+ T cell-mediate immunity, while comparable analogues of HLA-class II tumour peptides have not been yet identified, likely due to the paucity of CD4 epitopes derived from tumour antigens [18] and the complex and more promiscuous binding features of class II peptides.

The promising idea of triggering stronger antigen-specific T cell expansion by simply introducing single amino acid modification in tumour peptide sequence has prompted over the past decade a broad array of vaccine trials based on the use of APL. Conversely, the clinical testing of natural peptides from major tumour antigens, such as Melan-A/Mart-1, gp100 and CEA was simultaneously almost abandoned, without gaining sufficient information about the actual immunogenicity and clinical efficacy of these native epitopes. Nevertheless, this strategy has not demonstrated so far a superior therapeutic potential as compared with other vaccination approaches [1, 19].

Understanding the reason for this relative failure might obviously be a complex task, clinical efficacy of anti-tumour vaccines being highly dependent from multiple factors such as the existence of immune escape mechanism at tumour cell level, the presence of regulatory/suppressive mechanisms in the host, or simply the usage of ineffective immunization strategies or vaccination schedules. However, it must be underlined that little effort is being made for investigating how alterations of peptide sequence, while enhancing the peptide/HLA interaction, may affect TCR recognition. Similarly, questions remain on how superagonist analogues, such as for instance CAP1-6D, may bias the TCR repertoire of interacting T cells. These unanswered issues raise significant concerns about the ability of T cells triggered by modified peptides to eventually recognize tumour cells with high affinity.

In the present paper we intend to reason on whether APL should still be used in clinical setting or other alternatives for improving anti-cancer vaccine have to be pursued.

The TCR: a flexibility but sensitive structure

Antigen recognition by T cells is triggered by the molecular interaction between the TCR and the HLA/peptide complex, which results in an intracellular signalling cascade leading to functional activation of T cell effector functions. Although antigen specificity is a hallmark of adaptive immunity, TCR is known to exhibit a certain degree of cross-reactivity allowing it to interact with more than one HLA/peptide complex [20, 21]. Such relative cross-reactivity, which still follows set rules of engagement being constrained by the same structural requirements [22], may be important in normal immunological processes such as thymic selection and possibly involved in pathogenic condition such as autoimmunity. The structural adaptability of the TCR, which is the basis of T cell cross-reactivity, results in a functional flexibility of T cell activation. Indeed, T cell recognition, initially considered an ‘all or nothing’ type event leading inevitably to T cell activation when TCR is engaged, can instead be finely tuned in the level and type of response depending on the mode of TCR interaction with the cognate ligand. The TCR is actually a very flexible structure capable of detecting a broad spectrum of HLA/peptide complexes, through a versatile signalling machinery [23]. Thus, the degree of T cell responses, ranging from full activation to partial activation, anergy or even apoptosis, in response to TCR engagement, is modulated by the fine structure of HLA-peptide complexes expressed on target cell surface. Antagonist, partial agonist, full agonist and superagonist peptides define HLA-presented protein fragments capable of hierarchical recruit T cell functions ranging from the block of activation to optimal triggering [24].

However, latest findings are showing that “T cells are not as degenerated as you think, once you get to know them”, for quoting the title of a recent publication by Shih and Allen [22]. This sentence suggests the emerging idea that T cell degeneracy is indeed limited, and that cross-recognition of multiple ligands by the same TCR is actually dictated by specific rules and similar structural requirements. An elegant study based on the use of covalently MHC-linked model peptides and thermodynamic evaluation of specific or cross-reactive TCR, has recently shed new insights into TCR specificity [25]. This work demonstrated that certain amino acid side chains on the MHC/peptide surface can actually disrupt the interaction with the TCR, even though the side chains are not directly involved in TCR binding. For instance, selected amino acids (such as Alanine) may allow other amino acids on the surface of the MHC/peptide complex to rotate more freely or to adopt a different conformation, with consequent changes in the energy of binding.

These new findings imply that the introduction of even subtle amino acid substitutions in a peptide sequence might affect TCR binding to the MHC/peptide complex that is largely unpredictable unless detailed conformational studies are performed. As a result, identifying the optimal structure that a tumour peptide must have to promote heightened immunogenicity and conserved recognition of the natural ligand expressed on tumour cells, may be a more complex and risky task that initially foreseen.

The ideal properties of optimized tumour peptides and the immunological results in preclinical setting

Based on the new knowledge on the TCR features, an optimized tumour peptide should blend different properties: 1. high affinity and stability of binding to HLA class I molecules, or proven more efficient interaction with cognate TCRs; 2. TCR binding features ensuring potent and rapid T cell expansion; 3. high level of TCR cross-reactivity with the parental peptide derived from the natural antigen; and 4. efficient recognition of the endogenously processed epitope expressed by tumour cells.

Most of the studies describing the identification of optimized tumour peptides tried to fulfil these requirements. As previously mentioned, the first attempts to produce tumour APL have been performed with the two most widely expressed melanoma antigens MelanA/Mart-1 and gp100. The first antigen is presented in the context of HLA-A2 through the immunodominant epitopes 27–35 and 26–35 [26], lacking one of the crucial anchor amino acids (leucine or methionine) required for the binding to this allele; modifications have been thus introduced to optimized HLA binding by inserting a leucine in position 2. The resulting 26-35/2L analogue soon resulted to match all the ideal properties of an optimized epitope, showing increased binding to HLA-A2, enhanced immunogenicity in PBMC from melanoma patients and healthy donors, high cross-reactivity of the 26-35/2L-specific T cells with the natural unmodified peptide and efficient recognition of MelanA/Mart-1+ HLA-A2+ melanoma cells, as tested in a large number of patients [13]. However, a sequent analysis showed that even with these promising features, some MelanA/Mart-1-specific T cell clones raised from tumour infiltrating lymphocytes of melanoma lesions could not cross-recognize the 2L analogue, and conversely, 2L-specific T cells did not always react with antigen-expressing tumour cells when analysed at clonal level [27]. These data already suggested that modifications of the HLA/peptide structure, even though conservative, could influence the TCR repertoire in a more complex fashion than expected. Almost at the same time, Rosenberg’s group described the gp100 modified peptides 209–217/2 M and 280–289/9 V, both altered by introducing more adequate amino acids at the anchor positions for HLA-A2 binding [14]. These analogues again fitted all the ideal features of optimized epitopes, and most importantly, generated T cells with convincing tumour recognition. However, the authors also underlined that T cell reactivity against melanoma cells could not be detected in all cases tested, and that several rounds of in vitro sensitizations were often required to detect it. After these two seminal works, attempts to identify optimized analogues were performed with most of the clinically relevant tumour antigens. Analogues with improved immunogenicity were also identified from the dominant HLA-A2-binding peptide 157–165 from antigen NY-ESO-1, one of the most immunogenic determinants of the cancer testis antigen family [28]. Several amino acid substitutions of the cysteine in P9 improved HLA binding, but the introduction of an alanine resulted in the highest immunogenicity and the most efficient recognition of tumour cells [29]. In two additional studies the use of a valine in P9 produced instead the best results in terms of immunogenicity, with a significant cross-recognition of tumour cells by induced T cells [30, 31]. However, the ability of T cells raised with NY-ESO-1 analogues to efficiently cross-recognized tumour cells was either analysed only at T cell clonal level or detected in just a subset of patients tested. More recently, a quite elegant and comprehensive study investigated the structural and kinetic features of TCR recognition of HLA-A2 loaded with the wild type NY-ESO-1157–165 peptide or its optimized analogues using a soluble version of a peptide-specific TCR [32]. This study identified two highly exposed residues, methionine and tryptophan, whose side chains protrude from the central part of the peptide, as the relevant contact sites for TCR. On the basis of these structural data, the authors hypothesised that the introduction of the 9-V substitution, aimed at increasing HLA binding as described above, should not directly influence the interaction of the HLA/peptide complex with the cognate TCR. However, the 9-V analogue appeared to exert not only augmented HLA binding but also, and surprisingly, heightened TCR affinity, likely through subtle repositioning of the peptide main chain and small but significant changes at the HLA/peptide-TCR interface. This resulted in a lower TCR Koff rate, and stronger activation of T cell function without compromising cross-reactivity with the wild-type peptide. These improved features could be detected in a A2-transgenic mouse model as well, whose T cells recognized NY-ESO-1+ tumour cells in a more efficient fashion when primed with the 9-V analogue as compared with the parental peptide. Although these data support the therapeutic potential of the 9-V modified peptide in anti-cancer vaccines, it should be underlined that the structural information obviously refers to a single NY-Eso-1 reactive TCR, while T cell-mediated anti-tumour immune responses usually do not involve restricted or conserved TCR repertoires, even when directed against the same tumour epitope [33]. Furthermore, the ability of the 9-V analogue to induce tumour-reactive T cells was tested only in A2-transgenic mice, and no information in human setting was provided. At the same time, this work highlights the indirect effects of anchor residue substitutions on TCR binding, effects that could influence the TCR repertoire of APL-induced T cells and thus explain the heterogeneous tumour cross-recognition observed with most optimized tumour peptides.

These considerations are even more relevant when tumour epitopes are modified for directly ameliorating TCR contact by the so-called superagonist peptides. A paradigmatic example is provided by CAP1-6D, a superagonist analogue of the native CEA-derived epitope CAP1 (CEA605–613), hypothesised to mediate a better TCR binding thanks to the introduction of an asparagine residue in position 6 [34]. The initial study reported that CAP1-6D was much more effective as compared with the native peptide in the activation of a CAP1-specific CTL line obtained from an HLA-A2+ individual immunized with a vaccinia CEA recombinant [34]. In addition, the agonist peptide was able to generate CD8+ CTL lines that recognized both the agonist and the native CAP1 peptides, and cross-react with CEA+ HLA-A2+ tumour cells in a single reported case.

We recently investigated the immunogenic properties of CAP1-6D with the aim of carefully assessing its ability to induce tumour-reactive T cells [35]. Through a comprehensive analysis in HLA-A2+ healthy individuals and colo-rectal carcinoma (CRC) patients, we found that CAP1-6D specific T cells reproducibly showed a reduced avidity for the native epitope and, most importantly, constantly lacked reactivity against HLA-A2+CEA+ CRC cells [35]. A more detailed characterization demonstrated that T cells primed by CAP1-6D displayed high avidity and CD8-independency for the APL. However, these cells reproducibly interacted with the natural epitope in a CD8-dependent fashion and with low avidity that was likely below the critical threshold required for recognition of tumour cells.

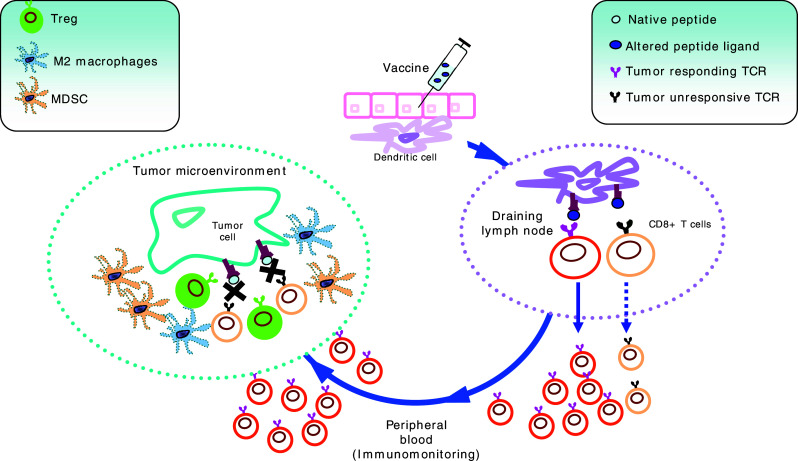

In sum, considering that tumour cells are known to express limited amounts of HLA/peptide complexes (estimated around 10–50 complexes/cell) [36], and to lack co-stimulatory molecules [37], the expansion of high avidity T cells could be a necessary condition for achieving effective T cell-mediated tumour recognition. However, based on the preclinical data reported so far, most optimized peptide do not seem to warrant the activation of a TCR repertoire displaying sufficient affinity for reacting with tumour cells (Fig. 1). Hence, while APL appear to constantly exert heightened immunogenicity and promote prompt and strong T cell expansion, their actual impact in boosting anti-tumour immunity remains largely unclear.

Fig. 1.

Potential weak points of T cell immune responses induced by modified tumour peptides. The vaccine, composed by APL tumour peptides, is injected s.c. or i.d., and the antigenic determinant is picked up by resident DC, subsequently migrating to draining LN. Here antigen-loaded DC encounter CD8+ T cells bearing TCR capable of interacting with the HLA/APL complex. This lymphocyte population usually comprehends T cells efficiently responding to the APL, but only a fraction of effectors may be capable to interact with the natural epitope expressed by tumour cells. These lymphocytes gain peripheral circulation, where they can be detected by immunomonitoring. However, only tumour cross-reactive CD8+ T cells can reach tumour site. Unfortunately, because of their low avidity for the native tumour epitope, their interaction with tumour cells is weak and unstable, and might be more easily overcome by suppressive mechanisms present in micro-environment (including Tregs, MDSC and M2 macrophages)

Are clinical results obtained with APL-based anti-tumour vaccines more convincing?

Despite the abundance of pre-clinical studies and the number of ongoing clinical trials based on optimized peptides as anti-cancer vaccines, clinical data concerning the actual ability of this approach to raise anti-tumour T cell activity are still scanty and yet confusing. As few direct comparisons between the immunological/clinical effects induced by vaccination with modified versus native peptides have been performed so far [38, 39], definitive conclusions about the superiority of this approach cannot be drawn. Furthermore, most studies using vaccines based on modified peptides report immunomonitoring data generally focused on the induction of APL-responding T cells, while the recognition of the native peptide and most importantly tumour cells is often neglected.

In some instances the choice of APL for clinical studies was in a way forced by the lack of valid alternatives among natural tumour peptides. In CRC and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), for example, vaccine trials have been almost exclusively focused on the APL CAP1-6D, because of the absence of highly immunogenic epitopes in these tumour histologies. A study by Fong et al. [15], performed with DC pulsed with CAP1-6D in 12 advanced CRC and NSCLC patients, reported increased frequency of CAP1-6D specific CD8+ T cells in five cases upon vaccination, as detected by tetramer staining. However, measurement with the same approach of T cells specific for the native CAP1 peptide was reported for a single case, showing comparable percentages of CAP-1 and CAP1-6D tetramer+ T cells. Anecdotal data were also provided for the ability of post-vaccine PBMC to lyse HLA-A2+ CEA+ tumour cells after in vitro peptide sensitization. However, the observation of two significant disease regressions suggested that a certain degree of tumour cross-recognition or the in vivo induction of antigen-spreading phenomena [40], could have been achieved.

Babatz et al. [41], who vaccinated a small group of comparable patients with CAP1-6D-pulsed DC and KLH, reported that vaccinated patients developed higher recognition of the modified as compared to the native peptide in their PBMC, as measured by Elispot. One single example of HLA-A2-restricted recognition of CEA+ tumour cells in post-vaccine, but not in pre-vaccine PBMC after in vitro peptide sensitization, was also reported.

Many clinical data available on immunization with tumour APL involve two of the most immunogenic antigens in melanoma, i.e. MelanA/Mart-1 and gp100. Following the reports describing the enhanced immunogenicity of their APL with increased HLA binding [13, 14], and the promising data of the first clinical trial with gp100-209/2 M analogue [38], these two tumour antigens have been constantly tested in vivo in the APL form. However, as mentioned above, limited clinical efficacy of this vaccine approach has been reproducibly reported [2]. Nevertheless, very few attempts have been made to actually evaluate the anti-tumour potential of T cells primed by APL. However, fine immunological studies have been performed in selected instances. For example, Clay et al. [42] reported a pivotal study showing that only 25% of T cell cloids raised from post-vaccine PBMC of patients vaccinated with modified gp100-209/2M peptide actually cross-reacted with the natural epitope, and only 15% could efficiently see HLA-A2+ gp100+ melanoma cells. Similar data were obtained by Stuge and et al. [43], who performed a comprehensive study based on the analysis of more than 200 T cell clones raised from PBMC of melanoma patients vaccinated with modified MelanA/Mart-1 and gp100 peptides. The results of this analysis undoubtedly show a wide range of recognition efficiencies in analysed T cells and globally a quite limited ability to respond to melanoma cells. A recent work by Spieser et al. [39], comparing the immunological effects of vaccination with MelanA/Mart-1-derived modified 26-35/2L versus the native peptide, clearly demonstrated that T cells primed by APL, although higher in frequency, displayed lower avidity for the natural antigen, and reduced effector functions as compared to T cells activated by the parental epitope.

As most scientists working in the field, we also embraced the “APL approach” in a series of vaccine trials based on the use of optimized peptides from MelanA/Mart-1, gp100, NY-ESO-1, CEA and survivin in different tumour histologies (including melanoma, prostate carcinoma and CRC). By extensive immunomonitoring we are evaluating the in vivo expansion of CD8-mediated T cell responses towards APL, natural analogues, and antigen-positive tumour cells (expressing high antigen levels, either spontaneously or after in vitro transfection). With the only exception of MelanA/Mart-1, whose specific T cells significantly cross-react with tumour in most cases analysed, preliminary results are unfortunately showing that T cells recognizing modified gp100, NY-ESO-1, CEA and surviving peptides display lower affinity for the natural analogues and, most importantly, very poor tumour reactivity. A fine characterization of the effector properties of in vivo-primed T cells shows that, even after in vitro peptide-sensitization, these cells mostly display reduced avidity for the natural analogues, and rarely recognize tumour cells, especially when NY-ESO-1 and survivin-specific T cells are evaluated (Filipazzi et al., Belli et al., Marrari et al., manuscripts in preparation). These data shed further doubts about the usage of APL as cancer immunogens, and their ability to provide clinical benefit to a significant fraction of vaccinated patients.

Other potential weak points of APL in cancer vaccination

Preferential in vivo expansion of T cells with low avidity for native peptide could also expose anti-tumour T lymphocytes to competition for antigen on the surface of antigen presenting cells (APC) or tumour targets. In fact, it has been recently reported that regulatory CD4+ T cells (Treg) and effector T cells share common TCR repertoires, suggesting that immunosuppression by Treg might occur through competition for the HLA/peptide complex presented on APC or targets [44]. As CD8+ regulatory T cells have also been described [45], it could be speculated that these cells may compete with anti-tumour CD8+ T cells for DC cross-priming or for interaction with tumour target during the T cell effector phase. If this could occur in vivo, a vaccine-induced development of T cells with low affinity for the cognate epitope would facilitate competition by regulatory T cells (Fig. 1). This potential pathway may represent a further disadvantage of APL, potentially leading to the in vivo expansion of a “weak” T cell population, inefficient in tumour recognition and unable to overcome suppressive pathways.

Do we really need to modify tumour peptides for heightening the clinical efficacy of tumour T cell vaccines or can we pursue alternative strategies?

Conceptually, optimization of tumour epitopes remains an appealing factor for molding TCR repertoire of anti-tumour T cell responses. However, the approach utilized so far rarely took into sufficient account the high sensitivity of the TCR structure and all the potential direct and indirect effects that an alteration of its ligand (introduced by APL) could have on T cell reactivity. Novel and more sophisticated strategies for APL design, based on ameliorated computational algorithms, could be utilized to identify APL with retained activity on anti-tumour immunity [46, 47], that should be readily tested in clinical setting.

Alternatively, native peptides could still represent a valid immunization tool if combined with effective strategies to boost full-fledged anti-tumour immunity. In addition, focusing on naturally presented HLA-associated peptides expressed on tumour cell surface, identifiable in a relatively high number according to the “Tubingen Approach”, should further reduce the risk of generating T cell reactivities functionally irrelevant to tumour control [48].

For improving the poor immunogenicity of natural epitopes, potent immunological adjuvants could be administered to trigger a pleiotropic activation of innate immunity and thus favour a higher, faster and more effective in vivo expansion of specific T cells. TLR agonists (like CpG) [39] have been shown to allow the priming by native MelanA/Mart-1 peptide of T cells with high functional avidity and enhanced effector functions, superior to those induced by analogues given by the same vaccine schedule. Compounds such Alum/IL-12 [49], have been found to favour the expansion of T cells efficiently cross-recognizing the native MelanA/Mart-1 epitope, while novel molecules, like soluble LAG-3 protein, have been recently shown to mediate the boost of potent anti-tumour T cells through APC activation [50].

Another important issue could be represented by the dose of peptide used during immunization. Indeed, administration of reduced amounts of peptide has been shown to favour the in vivo expansion of high avidity T cells in murine models [51] and in vitro experiments [52]. In contrast, immunological and clinical effects of low peptide doses have never been assessed in clinical setting.

According to murine studies, depletion of cells involved in immunosuppressive pathways in tumour-bearing hosts, such as Treg and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, releases natural anti-tumour immunity and improves the immunization effect of vaccination [53, 54]. As the frequency of these cells seem to impair T cell activation in response to cancer vaccines [55], pharmacological strategies aimed at reducing number and function of these regulatory cell components [16, 56–58] could be tested for their ability not only to increase the number of antigen-specific T cells but also to affect their TCR repertoire and the avidity for tumour targets.

Whatever be the strategy followed for identifying more effective protocols of cancer vaccines, it will still be crucial to monitor the behaviour of tumour-recognizing T cells in peripheral blood, draining lymph nodes, tumour or vaccine sites, without assuming that a raise of vaccine-specific cells will automatically result in a significant anti-tumour immunity.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Agata Cova, Paola Squarcina, Francesca Rini and Valeria Beretta, for the skilful work on the immunological monitoring of vaccinated patients. This work was in part supported by grants of Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC, Milan), Italian Ministry of Health-Rome (contracts #70 and 72), the European Community (Cancerimmunotherapy), Istituto Superiore di Sanità-Rome (contracts # ACC2/R2.5 and 7OAF2), and Fondazione Italo Monzino-Milano.

Footnotes

This article is a symposium paper from the conference “Immunotherapy—From Basic Research to Clinical Applications”, Symposium of the Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 685, held in Tübingen, Germany, 6–7 March 2008.

References

- 1.Parmiani G, Castelli C, Santinami M, Rivoltini L. Melanoma immunology: past, present and future. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:121–127. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32801497d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivoltini L, Canese P, Huber V, Iero M, Pilla L, Valenti R, Fais S, Lozupone F, Casati C, Castelli C, Parmiani G. Escape strategies and reasons for failure in the interaction between tumour cells and the immune system: how can we tilt the balance towards immune-mediated cancer control? Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2005;5:463–476. doi: 10.1517/14712598.5.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zippelius A, Pittet MJ, Batard P, Rufer N, de Smedt M, Guillaume P, Ellefsen K, Valmori D, Lienard D, Plum J, MacDonald HR, Speiser DE, Cerottini JC, Romero P. Thymic selection generates a large T cell pool recognizing a self-peptide in humans. J Exp Med. 2002;195:485–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprent J, Lo D, Gao EK, Ron Y. T cell selection in the thymus. Immunol Rev. 1988;101:173–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1988.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huseby ES, White J, Crawford F, Vass T, Becker D, Pinilla C, Marrack P, Kappler JW. How the T cell repertoire becomes peptide and MHC specific. Cell. 2005;122:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marincola FM, Jaffee EM, Hicklin DJ, Ferrone S. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv Immunol. 2000;74:181–273. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60911-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marincola FM, Wang E, Herlyn M, Seliger B, Ferrone S. Tumors as elusive targets of T-cell-based active immunotherapy. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:335–342. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers PR, Grey HM, Croft M. Modulation of naive CD4 T cell activation with altered peptide ligands: the nature of the peptide and presentation in the context of costimulation are critical for a sustained response. J Immunol. 1998;160:3698–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dressel A, Chin JL, Sette A, Gausling R, Hollsberg P, Hafler DA. Autoantigen recognition by human CD8 T cell clones: enhanced agonist response induced by altered peptide ligands. J Immunol. 1997;159:4943–4951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vergelli M, Hemmer B, Kalbus M, Vogt AB, Ling N, Conlon P, Coligan JE, McFarland H, Martin R. Modifications of peptide ligands enhancing T cell responsiveness imply large numbers of stimulatory ligands for autoreactive T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:3746–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholson LB, Waldner H, Carrizosa AM, Sette A, Collins M, Kuchroo VK. Heteroclitic proliferative responses and changes in cytokine profile induced by altered peptides: implications for autoimmunity. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:264–269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valmori D, Fonteneau JF, Lizana CM, Gervois N, Lienard D, Rimoldi D, Jongeneel V, Jotereau F, Cerottini JC, Romero P. Enhanced generation of specific tumor-reactive CTL in vitro by selected Melan-A/MART-1 immunodominant peptide analogues. J Immunol. 1998;160:1750–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkhurst MR, Salgaller ML, Southwood S, Robbins PF, Sette A, Rosenberg SA, Kawakami Y. Improved induction of melanoma-reactive CTL with peptides from the melanoma antigen gp100 modified at HLA-A*0201-binding residues. J Immunol. 1996;157:2539–2548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fong L, Hou Y, Rivas A, Benike C, Yuen A, Fisher GA, Davis MM, Engleman EG. Altered peptide ligand vaccination with Flt3 ligand expanded dendritic cells for tumor immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8809–8814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141226398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morse MA, Hobeika AC, Osada T, Serra D, Niedzwiecki D, Lyerly HK, Clay TM. Depletion of human regulatory T cells specifically enhances antigen specific immune responses to cancer vaccines. Blood. 2008;112:610–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivoltini L, Squarcina P, Loftus DJ, Castelli C, Tarsini P, Mazzocchi A, Rini F, Viggiano V, Belli F, Parmiani G. A superagonist variant of peptide MART1/Melan A27–35 elicits anti-melanoma CD8+ T cells with enhanced functional characteristics: implication for more effective immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 1999;59:301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novellino L, Castelli C, Parmiani G. A listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells: March 2004 update. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:187–207. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slingluff CL, Jr, Engelhard VH, Ferrone S. Peptide and dendritic cell vaccines. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2342s–2345s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kersh GJ, Allen PM. Essential flexibility in the T-cell recognition of antigen. Nature. 1996;380:495–498. doi: 10.1038/380495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evavold BD, Sloan-Lancaster J, Wilson KJ, Rothbard JB, Allen PM. Specific T cell recognition of minimally homologous peptides: evidence for multiple endogenous ligands. Immunity. 1995;2:663–665. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shih FF, Allen PM. T cells are not as degenerate as you think, once you get to know them. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:1041–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hennecke J, Wiley DC. T cell receptor-MHC interactions up close. Cell. 2001;104:1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloan-Lancaster J, Paul MA. Significance of T-cell stimulation by altered peptide ligands in T cell biology. Curr Op Immunol. 1995;7:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huseby ES, Crawford F, White J, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Interface-disrupting amino acids establish specificity between T cell receptors and complexes of major histocompatibility complex and peptide. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1191–1199. doi: 10.1038/ni1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Sakaguchi K, Robbins PF, Rivoltini L, Yannelli JR, Appella E, Rosenberg SA. Identification of the immunodominant peptides of the MART-1 human melanoma antigen recognized by the majority of HLA-A2-restricted tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:347–352. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valmori D, Gervois N, Rimoldi D, Fonteneau JF, Bonelo A, Liénard D, Rivoltini L, Jotereau F, Cerottini JC, Romero P. Diversity of the fine specificity displayed by HLA-A*0201-restricted CTL specific for the immunodominant Melan-A/MART-1 antigenic peptide. J Immunol. 1998;161:6956–6962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jäger E, Chen YT, Drijfhout JW, Karbach J, Ringhoffer M, Jäger D, Arand M, Wada H, Noguchi Y, Stockert E, Old LJ, Knuth A. Simultaneous humoral and cellular immune response against cancer-testis antigen NY-ESO-1: definition of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2-binding peptide epitopes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:265–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero P, Dutoit V, Rubio-Godoy V, Liénard D, Speiser D, Guillaume P, Servis K, Rimoldi D, Cerottini JC, Valmori D. CD8+ T-cell response to NY-ESO-1: relative antigenicity and in vitro immunogenicity of natural and analogue sequences. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:766s–772s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bownds S, Tong-On P, Rosenberg SA, Parkhurst M. Induction of tumor-reactive cytotoxic T-lymphocytes using a peptide from NY-ESO-1 modified at the carboxy-terminus to enhance HLA-A2.1 binding affinity and stability in solution. J Immunother. 2001;24:1–9. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen JL, Dunbar PR, Gileadi U, Jäger E, Gnjatic S, Nagata Y, Stockert E, Panicali DL, Chen YT, Knuth A, Old LJ, Cerundolo V. Identification of NY-ESO-1 peptide analogues capable of improved stimulation of tumor-reactive CTL. J Immunol. 2000;165:948–955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JL, Stewart-Jones G, Bossi G, Lissin NM, Wooldridge L, Choi EM, Held G, Dunbar PR, Esnouf RM, Sami M, Boulter JM, Rizkallah P, Renner C, Sewell A, van der Merwe PA, Jakobsen BK, Griffiths G, Jones EY, Cerundolo V. Structural and kinetic basis for heightened immunogenicity of T cell vaccines. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1243–1255. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole DJ, Weil DP, Shamamian P, Rivoltini L, Kawakami Y, Topalian S, Jennings C, Eliyahu S, Rosenberg SA, Nishimura MI. Identification of MART-1-specific T-cell receptors: T cells utilizing distinct T-cell receptor variable and joining regions recognize the same tumor epitope. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5265–5268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaremba S, Barzaga E, Zhu M, Soares N, Tsang KY, Schlom J. Identification of an enhancer agonist cytotoxic T lymphocyte peptide from human carcinoembryonic antigen. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4570–4577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iero M, Squarcina P, Romero P, Guillaume P, Scarselli E, Cerino R, Carrabba M, Toutirais O, Parmiani G, Rivoltini L. Low TCR avidity and lack of tumor cell recognition in CD8(+) T cells primed with the CEA-analogue CAP1-6D peptide. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1979–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0342-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purbhoo MA, Sutton DH, Brewer JE, Mullings RE, Hill ME, Mahon TM, Karbach J, Jäger E, Cameron BJ, Lissin N, Vyas P, Chen JL, Cerundolo V, Jakobsen BK. Quantifying and imaging NY-ESO-1/LAGE-1-derived epitopes on tumor cells using high affinity T cell receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176:7308–7316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochsenbein AF, Sierro S, Odermatt B, Pericin M, Karrer U, Hermans J, Hemmi S, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Roles of tumour localization, second signals and cross priming in cytotoxic T-cell induction. Nature. 2001;411:1058–1064. doi: 10.1038/35082583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, Hwu P, Marincola FM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, Dudley ME, Schwarz SL, Spiess PJ, Wunderlich JR, Parkhurst MR, Kawakami Y, Seipp CA, Einhorn JH, White DE. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 1998;4:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speiser DE, Baumgaertner P, Voelter V, Devevre E, Barbey C, Rufer N, Romero P. Unmodified self antigen triggers human CD8 T cells with stronger tumor reactivity than altered antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3849–3854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800080105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lurquin C, Lethé B, De Plaen E, Corbière V, Théate I, van Baren N, Coulie PG, Boon T. Contrasting frequencies of antitumor and anti-vaccine T cells in metastases of a melanoma patient vaccinated with a MAGE tumor antigen. J Exp Med. 2005;201:249–257. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Babatz J, Rollig C, Lobel B, Folprecht G, Haack M, Gunther H, Kohne CH, Ehninger G, Schmitz M, Bornhauser M. Induction of cellular immune responses against carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with metastatic tumors after vaccination with altered peptide ligand-loaded dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:268–276. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0021-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clay TM, Custer MC, McKee MD, Parkhurst M, Robbins PF, Kerstann K, Wunderlich J, Rosenberg SA, Nishimura MI. Changes in the fine specificity of gp100(209–217)-reactive T cells in patients following vaccination with a peptide modified at an HLA-A2.1 anchor residue. J Immunol. 1999;162:1749–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stuge TB, Holmes SP, Saharan S, Tuettenberg A, Roederer M, Weber JS, Lee PP. Diversity and recognition efficiency of T cell responses to cancer. PLoS Med. 2004;1(2):e28–160. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fazilleau N, Bachelez H, Gougeon ML, Viguier M. Cutting edge: size and diversity of CD4+ CD25 high Foxp3+ regulatory T cell repertoire in humans: evidence for similarities and partial overlapping with CD4+ CD25- T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:3412–3416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kiniwa Y, Miyahara Y, Wang HY, Peng W, Peng G, Wheeler TM, Thompson TC, Old LJ, Wang RF. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells mediate immunosuppression in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6947–6958. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tangri S, Ishioka GY, Huang X, Sidney J, Southwood S, Fikes J, Sette A. Structural features of peptide analogs of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen class I epitopes that are more potent and immunogenic than wild-type peptide. J Exp Med. 2001;194:833–846. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Houghton CS, Engelhorn ME, Liu C, Song D, Gregor P, Livingston PO, Orlandi F, Wolchok JD, McCracken J, Houghton AN, Guevara-Patiño JA. Immunological validation of the EpitOptimizer program for streamlined design of heteroclitic epitopes. Vaccine. 2007;25:5330–5342. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singh-Jasuja H, Emmerich NP, Rammensee HG. The Tübingen approach: identification, selection, and validation of tumor-associated HLA peptides for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamid O, Solomon JC, Scotland R, Garcia M, Sian S, Ye W, Groshen SL, Weber JS. Alum with interleukin-12 augments immunity to a melanoma peptide vaccine: correlation with time to relapse in patients with resected high-risk disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:215–222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Casati C, Camisaschi C, Rini F, Arienti F, Rivoltini L, Triebel F, Parmiani G, Castelli C. Soluble human LAG-3 molecule amplifies the in vitro generation of type 1 tumor-specific immunity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4450–4460. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim M, Moon HB, Kim K, Lee KY. Antigen dose governs the shaping of CTL repertoires in vitro and in vivo. Int Immunol. 2006;18:435–444. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang S, Linette GP, Longerich S, Haluska FG. Antimelanoma activity of CTL generated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells after stimulation with autologous dendritic cells pulsed with melanoma gp100 peptide G209-2 M is correlated to TCR avidity. J Immunol. 2002;169:531–539. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Colombo MP, Piconese S. Regulatory-T-cell inhibition versus depletion: the right choice in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:880–887. doi: 10.1038/nrc2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Filipazzi P, Valenti R, Huber V, Pilla L, Canese P, Iero M, Castelli C, Mariani L, Parmiani G, Rivoltini L. Identification of a new subset of myeloid suppressor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with modulation by a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulation factor-based antitumor vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2546–2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schabowsky RH, Madireddi S, Sharma R, Yolcu ES, Shirwan H. Targeting CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T-cells for the augmentation of cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2007;8:1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Santo C, Serafini P, Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Bolla M, Del Soldato P, Melani C, Guiducci C, Colombo MP, Iezzi M, Musiani P, Zanovello P, Bronte V. Nitroaspirin corrects immune dysfunction in tumor-bearing hosts and promotes tumor eradication by cancer vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4185–4190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409783102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nefedova Y, Fishman M, Sherman S, Wang X, Beg AA, Gabrilovich DI. Mechanism of all-trans retinoic acid effect on tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11021–11028. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]