Abstract

Precise identification of regulatory T cells is crucial in the understanding of their role in human cancers. Here, we analyzed the frequency and phenotype of regulatory T cells (Tregs), in both healthy donors and melanoma patients, based on the expression of the transcription factor FOXP3, which, to date, is the most reliable marker for Tregs, at least in mice. We observed that FOXP3 expression is not confined to human CD25+/high CD4+ T cells, and that these cells are not homogenously FOXP3+. The circulating relative levels of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells may fluctuate close to 2-fold over a short period of observation and are significantly higher in women than in men. Further, we showed that FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells are over-represented in peripheral blood of melanoma patients, as compared to healthy donors, and that they are even more enriched in tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes and at tumor sites, but not in normal lymph nodes. Interestingly, in melanoma patients, a significantly higher proportion of functional, antigen-experienced FOXP3+ CD4+ T was observed at tumor sites, compared to peripheral blood. Together, our data suggest that local accumulation and differentiation of Tregs is, at least in part, tumor-driven, and illustrate a reliable combination of markers for their monitoring in various clinical settings.

Keywords: Human, Melanoma, Regulatory T cells, FOXP3, Flow cytometry

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that a thymus-derived population of natural regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a central role in controlling immune responsiveness to self- and allo-antigens [39].

CD4+ T cells constitutively expressing high levels of the IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25) were found to be enriched for immunosuppressive activity. In mice, absence of these cells leads to early appearance of a combination of multiple autoimmune manifestations, culminating in a wasting disease. Adoptive transfer of animals with CD4+ CD25+ T cells inhibits the development of autoimmunity by suppressing self-reactive T cells in the periphery. Nevertheless, the value of CD25 as a biomarker for regulatory T cells is limited, particularly in humans, since it is also expressed on recently activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

FOXP3, a member of the FOXP family of transcription factors (FOXP1–4), has recently been discovered as a major marker and functional regulator of Treg cell development. This finding brought out the possibility for a better characterization of Tregs in both mouse and humans [16, 47, 51]. Mutations in the foxp3 gene were linked to autoimmune manifestations observed in the Scurfy mouse [9] and in humans with the IPEX syndrome, a lethal X-linked disease characterized by immune deregulation, polyendocrinopathy, and enteropathy [6, 8]. Transfection of FOXP3 in CD4+ CD25− naive T cells can convert them to functionally and phenotypically natural Treg-like cells [22]. Moreover, a recent report on the function of IL-2 in foxp3-expressing cells showed that foxp3+ CD4+ T cells normally develop in IL2−/− and IL2Rα−/− mice, and are fully able to suppress T cell proliferation in vitro [15]. Recent observations suggest that FOXP3 cooperates with NFAT, and physical interaction between these two molecules switches the activation program of a T cell into a suppressor program [50]. These results indicate that FOXP3 is a master control gene for the development and function of natural Treg.

CD4+ T cells play an important, but dual role in regulating host immune responses against cancer. On one hand, the combined and concomitant activation of both helper CD4+ T cells and cytolytic CD8+ T cells greatly potentiate the eradication of tumor cells. On the other hand, the presence of CD4+ T cells displaying suppressive activity at the tumor site may play a significant role in inhibiting anti-tumor immunity [25].

In human cancer, a state of local immune tolerance, concerning both CD8+ T cell activation and function, has recently been reported [2, 21, 53]. Multiple mechanisms have been postulated for being responsible for preventing an efficient anti-tumor response: from the tumor cell side, different escape mechanisms have been described (e.g., down regulation of HLA molecules, loss of expression of tumor-associated antigens, secretion of inhibitory cytokines, lack of costimulatory molecules) [2, 18, 24]. From the immune cell side, the accumulation of lymphocytes with suppressive function could abrogate the anti-tumor cytotoxic response. An increased prevalence of CD25+ CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood or at tumor sites in patients bearing different types of epithelial cancer suggest that these cells are Tregs inhibiting an efficient anti-tumor cytotoxic response [11, 23, 28, 46, 49]. However, the majority of data available to date on FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in human cancers mainly focused on their monitoring by immunohistochemical analysis in biopsy of tissue sections [4, 13, 29–31, 33], with the consequent impossibility of a multiparametric monitoring, an exact quantification of Tregs in different body compartments, and an evaluation of their functionality. Flow cytometric detection of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells at the single cell level has been illustrated in several recent human cancer reports, while the flow cytometric Treg cell monitoring mainly relied on the evaluation of CD4+ CD25+ T cells [14, 20, 26, 42, 48].

The purpose of our study was to directly characterize, by flow cytometry, the population of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in humans, both in healthy donors (HDs) and melanoma patients.

Materials and methods

Tissues and cells

Peripheral blood (n = 42), metastatic lymph nodes (LNs) (tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes or TILN, n = 10), normal LNs diagnosed as tumor free by pathological examination (NLN, n = 10), and non-lymphoid tissue metastases (TIL, n = 3) were obtained from a total of 42 patients (stage III–IV, mean age: men 60.7, women 55.3 years). Informed consent was obtained from all patients (Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland). Peripheral blood was obtained from healthy adult donors at the blood transfusion centre (Lausanne, Switzerland) (mean age: men 44.7, women 45.3 years). Cord blood samples were obtained from umbilical cord veins immediately after delivery of the placenta (University Hospital of Ghent, Belgium). Mononuclear cells were purified and immediately frozen as described previously [35].

Antibodies and flow cytometry

MAbs were from Becton Dickinson (San José, CA; anti-human CD25-PE, CD4-PECy7, CD127 purified, CD27-Alexa750, CD45RA-ECD, CCR7-purified, CTLA-4-APC or CTLA-4-PECy5, GAM-FITC, GAR-APC antibodies), except for anti-human-FOXP3-FITC (clone PCH 101) and CD127-pacific blue antibodies (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA), and were used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Thawed, cryopreserved PBMCs were stained in triplicates for healthy donors or monoplicates for melanoma patients. First, staining for cell surface markers was performed at 4°C. After wash, cells were fixed, subsequently permeabilized with the eBiosciences Kit, and stained intracellularly for FOXP3.

Lymphocytes were gated according to their forward and side scatter characteristics, collected using a FACSCanto or LSRII, and analysis was performed using the CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San José, CA).

Proliferation assay

Proliferation assays were performed using highly pure, flow cytometry-based sorted CD4+ CD25+ CD127− and CD4+ CD25− CD127+ T cells, from PBLs of HDs (n = 4), PBLs from melanoma patients (n = 4), and from TILN of melanoma patients (n = 3). The gating strategy for sorting is shown in Fig. 4d, left panel. Upon re-analysis of the flow cytometry-based sorted populations, purity was >95%. CD4+ CD25+ CD127− and CD4+ CD25− CD127+ T cells were cultured alone or co-cultured at 1:1 ratio in triplicates, with irradiated allogenic PBMCs, in 96-well round-bottom plates in RPMI 1640, with 8% heat-inactivated pooled human serum, for 5 days; [H3] thymidine was added for the last 18 h before harvesting and measuring scintillation counts. Inhibition of proliferation was calculated as follows: [1 − (proliferation of Tresp + Tregs in co-culture)/(proliferation of T responders alone + proliferation of Tregs alone)] × 100.

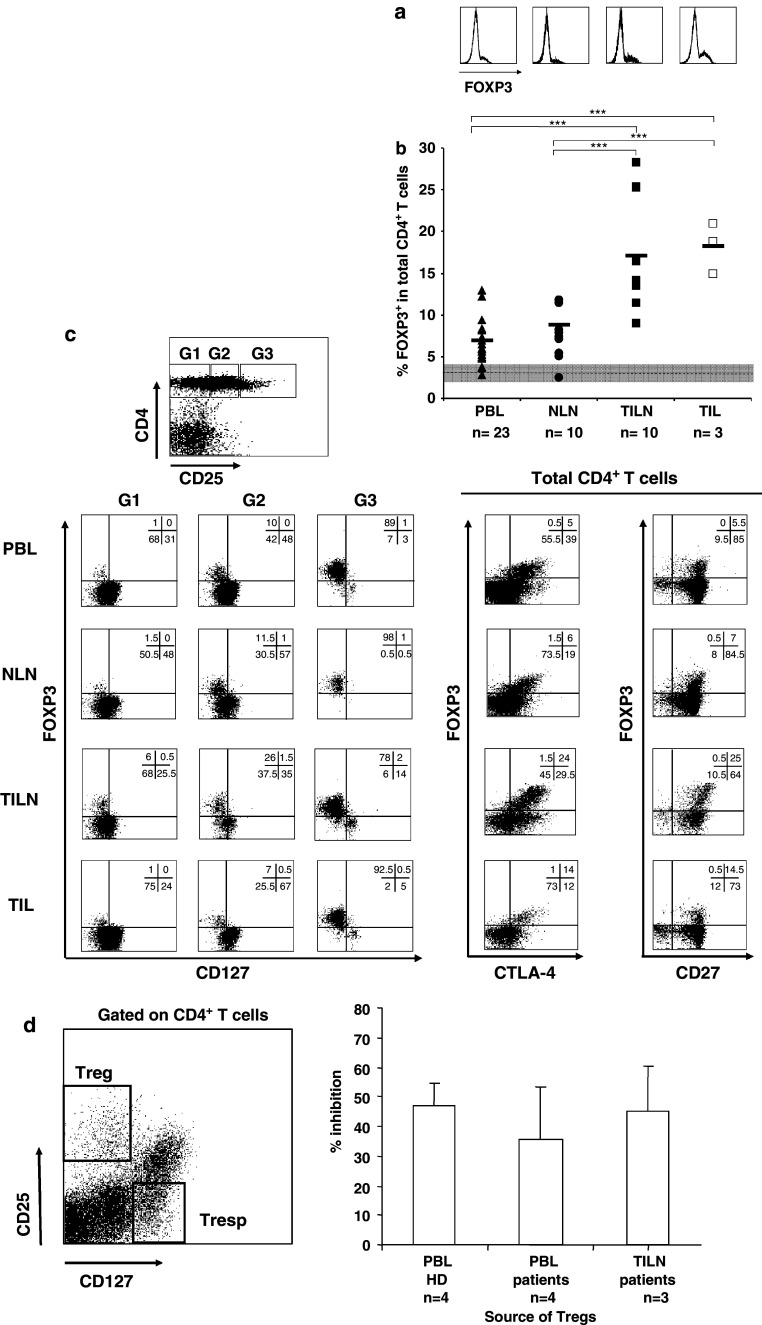

Fig. 4.

FOXP3 expression on CD4+ T cells in melanoma patient tissues. Lymphocytes were purified from PB, NLNs, TILNs, and TILs from melanoma patients (n = 23). Percentages of FOXP3+ in total CD4+ T cells were measured by flow cytometry. a Representative histograms for FOXP3 staining in gated CD4+ T cells are shown for each tissue. b Black lines represent mean percentage values in the different body compartments. Dashed line represents the mean value of FOXP3+ in total CD4+ T cells in HDs (grey area stays for CV). ***P value <0.001. c Rectangular gates (G1, G2, and G3) were drawn on CD4+ T cells according to increasing expression of the CD25 antigen, and expression of FOXP3 and CD127 in each gate is shown in representative dot plots for the different tissues (left dot plots). Expression of FOXP3 and CTLA-4, as well as FOXP3 and CD27, is shown in total CD4+ T cells for the different tissues (right dot plots). Numbers represent percentages of cells in each quadrant. d Purified CD4+ CD25+ CD127− T cells and CD4+ CD25− CD127+ T cells, obtained by flow cytometry-based cell sorting from PBLs from four HDs and four melanoma patients, and from freshly prepared single cell suspensions from three metastatic lymph nodes, were cultured either alone or at 1:1 ratio under allogeneic stimulation. 3[H] thymidine was added on day 5 for the last 18 h. On the left, the gating strategy for sorting, and on the right, the mean percentages and standard deviations of inhibition of proliferation, are shown

Statistical analysis

The significance of the results was determined using the Student t test. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

FOXP3 and CD25 expression in human CD4+ T cells in HDs and melanoma patients

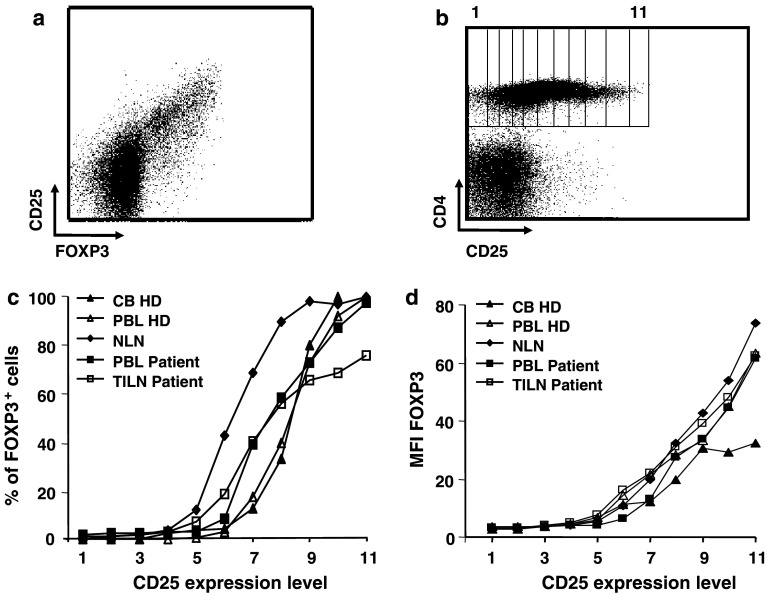

Lymphocytes from cord and peripheral blood of HDs as well as from peripheral blood, normal lymph nodes (NLNs), and TILNs from melanoma patients, were purified and stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 antibodies and, once fixed and permeabilized, with anti-FOXP3 antibody (Fig. 1a). To establish the relationship between the two markers, electronically set gates according to increasing expression of CD25 were drawn on CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1b) and percentages of FOXP3+ cells as well as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of FOXP3 expression were assessed in each subset (Fig. 1c, d, respectively). While a significant number of CD25+ cells expressed the FOXP3 marker, a proportion of FOXP3+ cells was clearly detectable in the CD25 intermediate and low subsets, as previously described for HDs [37]. For instance, in the NLN lymphocyte population, close to 50% of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells expressed a CD25low phenotype. For the same proportion of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells, CD25 expression was greater in the PBL and TILN populations from a cancer patient, and even higher for cord blood and PBL of healthy donor origin. Thus, in samples from melanoma patients (both from peripheral blood and TILNs), high percentages of CD25 intermediate cells were positive for the FOXP3 marker. In contrast, an important proportion of the CD25high cells (up to 30%) did not display any detectable FOXP3 expression, possibly corresponding to a population of recently activated T cells in the tumor-infiltrated tissues. FOXP3 MFI augments with increasing expression of CD25, in a similar manner in healthy donors (HDs) compared to patients. No detectable expression of FOXP3 on CD8+ T cells was observed by flow cytometry, even if some of the cells were CD25 positive. No significant staining was seen using an isotype matched control IgG–FITC (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Correlation between FOXP3 and CD25 expression on different CD4+ human T cell subsets. Human lymphocytes purified from cord blood (CB), peripheral blood (PBL), normal lymph nodes (NLN), or tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes (TILN) were stained using a combination of anti-CD4, anti-CD25, and anti-FOXP3 antibodies. a Representative dot plot for CD25 and FOXP3 staining is shown. Dot plot is gated on CD4+ cells. b Rectangular gates from 1 to 11 were drawn on CD4+ T cells according to increasing expression of the CD25 antigen, as labeled with a PE-conjugated antibody. c Percentages of FOXP3 positive cells were calculated for CD4+ T cells in each gate using CellQuest software. Representative examples for HDs and patients are shown. d Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of FOXP3 is shown for CD4+ T cells in each gate. Representative examples for HDs and patients are shown

Treg kinetics in healthy donors’ peripheral blood

Limited data are available to date on the frequency of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in cord blood and peripheral blood from HDs [17]. We found mean values of 3.5% (n = 4, range 1.6–6.2) and 2.9% (n = 53, range 1.1–5.7) of CD4+ T cells expressing the FOXP3 protein in cord and peripheral blood, respectively.

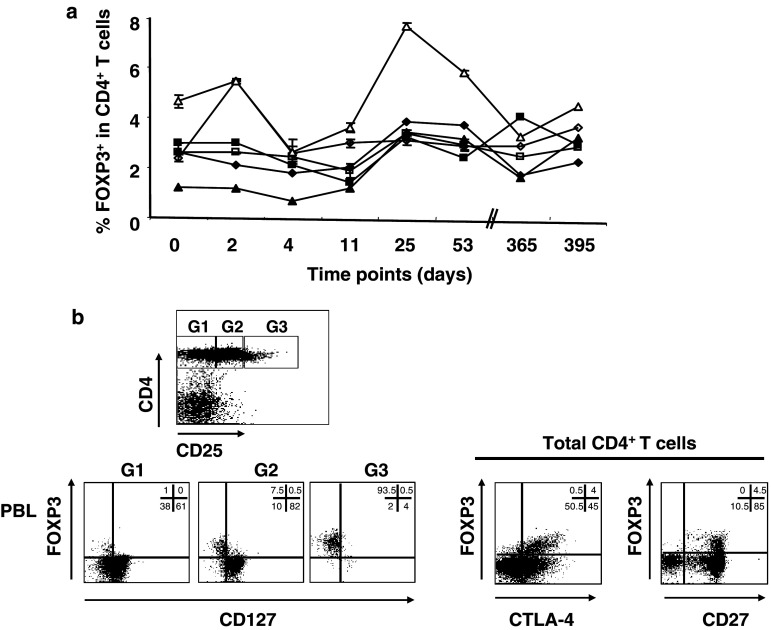

To compare results from HDs and patients, we first conducted a study to assess the variation of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cell number in peripheral blood of HDs over time. In six HDs, three men and three women, the percentages of total CD4+ as well as FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells were monitored over a period of 2 months, with two additional late time points at 12 and 13 months. Overall percentages of total CD4+ T cells were stable over time in all individuals tested. Values ranged from 27.6 to 57.8% in the different donors, with a mean coefficient of variation (CV) over time of 6.9% (range 2.5–14.4) (data not shown).

Mean values of 2.4% (range 0.6–3.8) for men and 3.5% (range 2.4–7.6) for women of FOXP3+ cells in total CD4+ T cells were observed (Fig. 2a). The levels of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in women were higher than those measured in men. The values of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells during the monitoring period showed a higher variability if compared to the percentages of total CD4+ T cells, with a mean CV of 35.3% (range 18.6–59.9). The stability and reproducibility of the assay were tested by repeatedly performing triplicate staining on the individual samples for each donor and each time point, with a mean CV of 6.9% (range 0.7–19). In addition, assessment of the expression of other markers (e.g., CD25, CD127, CTLA-4, CD27) on the FOXP3-positive population confirmed that these cells display a typical Treg phenotype (e.g., CD127−, CTLA-4+, CD27+) (Fig. 2b). Staining for LAP, TGFβ, and GPR83 were consistently negative (data not shown). Thus, in healthy donors, the percentages of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells do show fluctuations within a relatively short period of observation.

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal study of FOXP3 expression on human CD4+ T cells in healthy donor (HD) blood. a Human lymphocytes purified from peripheral blood of HDs, three men (closed symbols) and three women (open symbols), were stained using a combination of anti-CD4 and anti-FOXP3 antibodies, in triplicates. Blood withdrawal was performed over a period of 13 months, on days 0, 2, 4, 11, 25, 53, 365, and 395. All the samples, from all time points, were frozen on the day of blood withdrawal, using the same standard operating procedure, and the staining was performed, in triplicates, on the same day for all the samples collected between days 0 and 4, between days 11 and 53, and between days 365 and 395 in order to reduce possible variations due to processing/staining. Mean percentages of FOXP3+ T cells in total CD4+ T cells, with SE bars for each time point measured, are shown. b Rectangular gates (G1, G2, and G3) were drawn on CD4+ T cells according to increasing expression of the CD25 antigen, and expression of FOXP3 and CD127 in each gate is shown in representative dot plots (left dot plots). Expression of FOXP3 and CTLA-4, as well as FOXP3 and CD27, is shown in total CD4+ T cells (right dot plots). Numbers represent percentages of cells in each quadrant

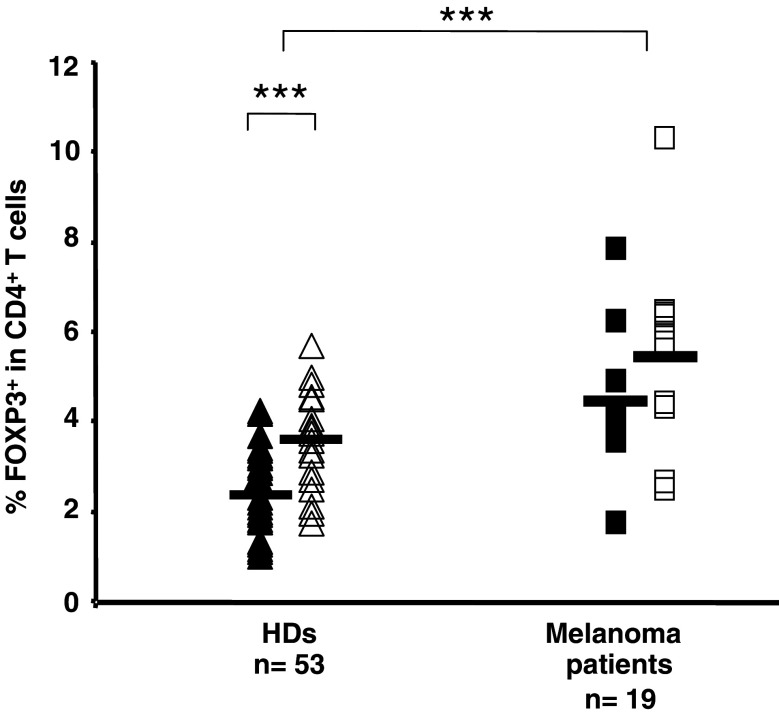

Increased levels of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients

Increased levels of CD4+ CD25+/high T cells have been reported in peripheral blood of cancer patients [11, 23, 28, 29, 42, 46, 49]. However, so far, the flow cytometric assessment of the prevalence and the phenotype of CD4+ T cells expressing the protein FOXP3 in cancer patients have not been explored systematically. First, 19 patients with stage III/IV melanoma, before any treatment, were analyzed with respect to the prevalence of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood. A comparison between values obtained in HDs (n = 53) and this cohort of melanoma patients revealed a 1.7-fold increase of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in patients compared to healthy individuals (Fig. 3). Mean values of FOXP3+ T cells among total CD4+ T lymphocytes in HDs were 2.9% (range 1.1–5.7), compared to 5.05% (range 1.8–10.4) observed in melanoma patients. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001), in contrast to data obtained in a previous report on CD4+ CD25high T cells, where no statistically significant difference was found on comparing the frequency of CD4+ CD25high T cells in peripheral blood of HDs and melanoma patients [46]. Significantly higher percentages of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells were found in healthy women (mean of 3.7%) compared to healthy men (mean of 2.4%, P < 0.001); similarly, among melanoma patients, women showed higher percentages of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells than men, with a mean of 5.5 and 4.5%, respectively. Yet, in the patients group, the observed difference did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 3.

FOXP3 expression on human peripheral blood CD4+ T cells from HDs and melanoma patients, segregated by gender. Lymphocytes were purified from peripheral blood of HDs (n = 53) and melanoma patients (n = 19) and percentages of FOXP3+ in total CD4+ T cells were measured by flow cytometry. Closed symbols represent values in men, open symbols in women. Black lines represent mean percentage values. ***P value <0.001

Increased frequency of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in TILNs and TILs of melanoma patients, compared to peripheral blood and normal LNs

We compared frequencies of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in ex vivo samples from four distinct body compartments: peripheral blood, NLNs, TILNs, and TILs (Fig. 4a, b; Table 1). Paired tissue samples were collected from a series of stage III/IV melanoma patients. The proportion of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells was significantly increased (P < 0.001) in the TILN (mean 17.4, range 9.1–28.3) compared to autologous PBLs (mean 6.9, range 3.7–13.0). An even higher increase was observed in TILs (mean 18.3, range 15.0–21.0, P < 0.001). In contrast, there was no statistical difference between frequencies of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor-free LNs (P = 0.73), suggesting a selective increase of FOXP3 expressing CD4+ T cells in metastatic lesions (P < 0.001 when comparing NLNs vs. TILNs or NLNs vs. TILs) (Fig. 4b; Table 1). Thus, FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells are increased in the tumor microenvironment of melanoma patients.

Table 1.

Summary of the frequencies of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in the 23 analyzed patients, recovered from different tissues

| Patients | PBL | LN | TILN | TIL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.8 | 13.5 | ||

| 2 | 3.7 | 28.3 | ||

| 3 | 12.2 | 16.5 | ||

| 4 | 8.4 | 13.8 | ||

| 5 | 7.4 | 14.2 | ||

| 6 | 7.3 | 11.5 | ||

| 7 | 5.6 | 11.5 | ||

| 8 | 5.9 | 13.7 | ||

| 9 | 13 | 25.4 | ||

| 10 | 13 | 25.3 | ||

| 11 | 6.5 | 7.2 | ||

| 12 | 5.1 | 7.5 | ||

| 13 | 5.2 | 8 | ||

| 14 | 8.2 | 11.9 | ||

| 15 | 5.6 | 9 | ||

| 16 | 4.8 | 8.3 | ||

| 17 | 4.8 | 7.9 | ||

| 18 | 7.3 | 5.4 | ||

| 19 | 6.9 | 5.1 | ||

| 20 | 2.7 | 2.3 | ||

| 21 | 9.4 | 18.8 | ||

| 22 | 6 | 15 | ||

| 23 | 5 | 21 |

Phenotypic characterization in terms of CD25, CD127, CD27, and CTLA-4 of the identified FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in the different samples isolated from all the body compartments did not show any significant difference. However, CTLA-4 expression was slightly increased in a proportion of TILN/TIL samples analyzed, yet not at a significant level if compared to their peripheral blood counterpart (Fig. 4c). Staining for LAP, mTGFβ, and GPR83 were negative in all the samples tested (data not shown).

From one particular patient, we had the opportunity to isolate at the same time point, lymphocytes from peripheral blood as well as from both a clinically progressing and a clinically regressing tumor-infiltrated lymph node. Interestingly, when assessing the percentage of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in these different samples, we detected 5.9% in the peripheral blood, 13.7% in the progressing, while only 10.0% in the regressing lymph node.

Importantly, the detected Tregs, in both peripheral blood and tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes, displayed an efficient inhibitory function on responder T cells. Proliferation of CD4+ CD25− CD127+ T cells was strongly inhibited by autologous CD4+ CD25+ CD127− cells isolated by flow cyotmetry-based cell sorting from PBLs or TILN from melanoma patients (Fig. 4d).

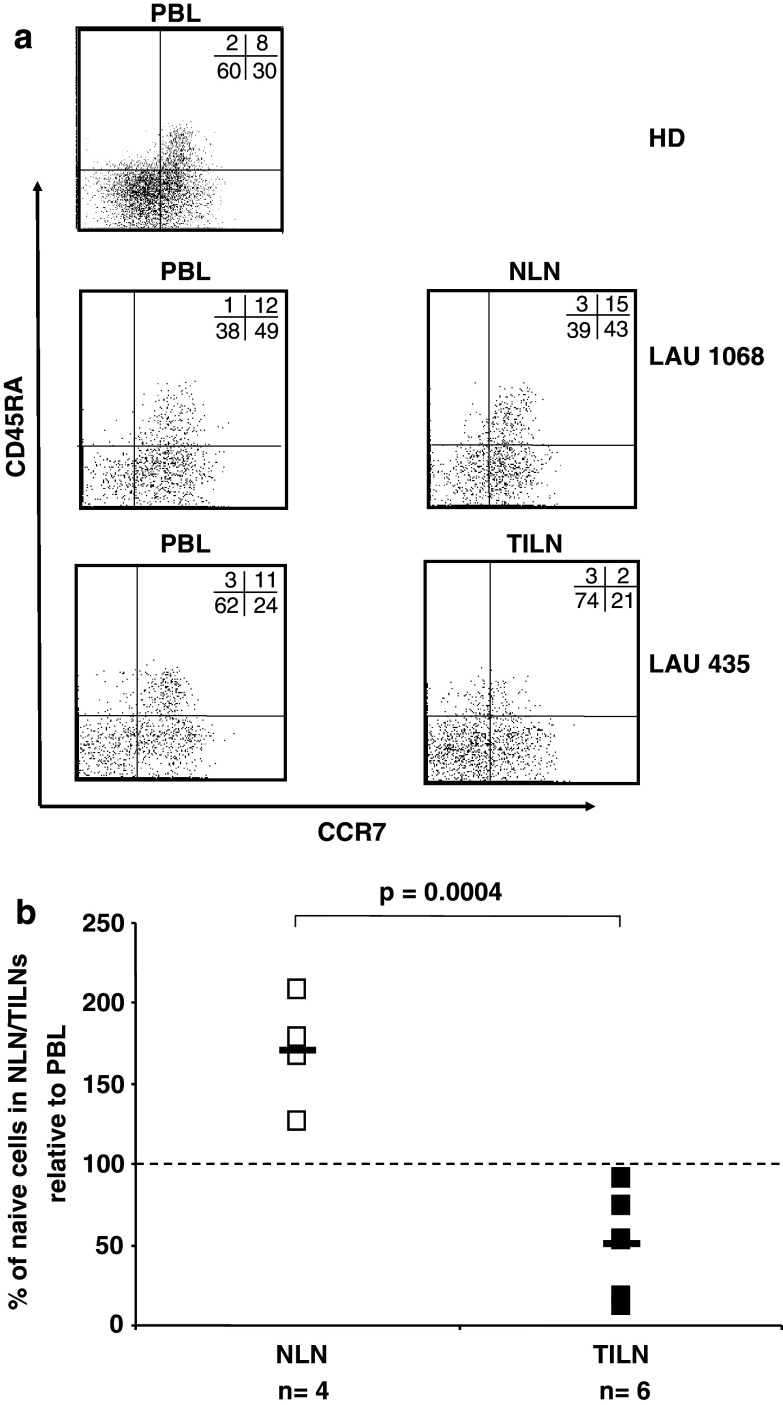

Increase of non-naive phenotype FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymph nodes, but not in normal LNs

Cord blood FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells predominantly display a naive phenotype, with the majority of the cells co-expressing both CD45RA and CCR7 molecules on the cell surface (mean 57.8% of total FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells, data not shown). In the peripheral blood from HDs, on the contrary, CD4+ T cells that are positive for the FOXP3 marker are predominantly comprised of memory cells, with a proportion still being naïve (mean of 9.5% of naive cells in FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells, n = 37) (Fig. 5a, upper panel).

Fig. 5.

Selective decrease of naive FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in TILN of melanoma patients. Lymphocytes were purified from peripheral blood, normal lymph nodes, tumor-infiltrated lymph nodes from HDs (n = 37) and melanoma patients (n = 10). Multicolor flow cytometric analysis was performed using a combination of anti-CD4, anti-CD45RA, anti-CCR7, and anti-FOXP3 antibodies. a Representative dot plots of CCR7 and CD45RA staining on FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in PBLs from a HD (upper panel), PBLs and NLN (middle panels), or PBLs and TILN (lower panels) of melanoma patients LAU 1068 and LAU 435, respectively. Numbers represent percentages of cells in each quadrant. b Percentages of naive cells (CD45RA+ CCR7+) in FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in NLN or TILN of melanoma patients. The level of naive cells in FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in autologous PBLs, are represented by 100%

Phenotypic characterization of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in terms of CD45RA and CCR7 from PBLs, NLNs, and TILNs of melanoma patients revealed a significant decrease in the CD45RA+ CCR7+ FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in TILNs compared to PBLs (Fig. 5a, middle and lower panels). In contrast, comparison of percentages of naive and memory cells among the FOXP3+ T cells in PBLs and tumor-free LNs showed even higher levels of naive Treg cells in the lymph nodes. When the level of naive FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in PBLs was arbitrarily defined at 100%, a mean of 171 and 51% was observed in NLNs and TILNs, respectively (Fig. 5b). In contrast, surprisingly, when comparing the total CD4+ T cell population, similar levels of naive cells were found in both tumor-free- and tumor-infiltrated-lymph nodes, with 102 and 96%, respectively, if compared to peripheral blood (data not shown).

Discussion

The main finding in this paper is the accumulation of highly differentiated and functionally suppressive FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in metastatic tumor lesions obtained from stage III to IV melanoma patients.

First, we determined the correlation between CD25 and FOXP3 expression on human T cells in different body compartments. While in cord as well as peripheral blood from both HDs and melanoma patients, expression of FOXP3 was, as expected, present in the majority of CD25-positive CD4+ T cells, a non-negligible proportion of CD25 expressing cells were FOXP3 negative in tumor lesions, indicating that, besides Tregs, effector T lymphocytes up regulating the CD25 molecule are comprised in this population. Moreover, in CD25int CD4+ T cells, we identified substantial numbers of FOXP3 expressing cells, while in CD25low CD4+ T cells, only low but significant percentages of cells were positive for FOXP3, similar to recent published data [27]. These observations correlate with some recent data generated in our laboratory on human CD4+ T cell clones. When CD4+ T cells were sorted by flow cytometry according to their CD25 expression and cloned by limiting dilution, 60% of the CD25+ CD4+ sorted clones expressed FOXP3, while the remaining clones did not express the protein at a detectable level. The clones generated from CD25− CD4+ sorted cells were 100% negative for FOXP3 (data not shown). Thus, together these data confirm and extend the consensus view that comparability and relevance of data on Treg, defined as CD25+ CD4+ T cells, are difficult and questionable.

For the validation of FOXP3 antigen as a marker identifying Tregs by flow cytometry and for their monitoring in clinical studies, it is important to know the consistency of the assay. In this regard, calculated inter-assay and intra-assay CV were largely acceptable, being 6.9 and 9.7%, respectively. However, inter individual variations in FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells over time showed a mean CV of 35.3%, corresponding to an important fluctuation of Tregs in HDs. The calculated 95% confidential interval (CI) is 1.05–4.8% (mean ± 1.96 SD). These important physiological variations in levels of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in HDs should be taken into account when interpreting past and future reports on the direct impact of different clinical manipulations on Treg frequency [7, 12]. In light of the calculated 95% CI, we propose a threshold value of at least 1.8-fold increase/decrease, when comparing treatment-induced variations in Treg frequencies to be considered significantly different. Moreover, it should be kept in mind that significant differences in Treg levels in the circulation are gender-associated. It might be possible that both observations, gender and time-dependent fluctuations in Tregs levels, reflect regulation by steroid hormones. In this regard, it is very interesting that fluctuations in the levels of Tregs have been very recently reported during the menstrual cycle [5].

Identified FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells also expressed high levels of the cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and CD27, and were negative for CD127, correlating with previous observations [38, 41]. However, FOXP3+ cells did not detectably express some other old and new postulated specific Treg markers such as LAP, membrane bound TGFß or GPR83 (data not shown) [3, 32, 34, 43]. Other specific cell surface markers for characterizing naturally occurring Treg in humans are currently under investigation in our laboratory, including analyses at the T cell clonal level.

In melanoma, recent data from a cohort of patients revealed that tumor progression was correlated with increased levels of circulating CD25+ CD4+ T cells, and that a significant clinical response to IL-2 therapy was only observed in those patients who displayed a decrease in CD25+ CD4+ T cells after treatment [10].

In a previous report on malignant melanoma, increased frequencies of CD25+ CD4+ T cells have been observed in TILN as compared to autologous PBLs, and their ability to inhibit the function of infiltrating T cells has been documented [46]. Similarly, in a patient suffering from melanoma with malignant ascites, despite a massive influx of activated CD8+ T cells in the ascites fluid, tumor progression was observed and CD25+ CD4+ T cells were increased in the ascites fluid and inhibited the function of anti-tumor CD8+ T cells [21]. Since Treg frequency and function in these studies was mostly based on total CD25+ CD4+ T cells, while FOXP3 analysis relied on detection of the product by PCR, we re-examined this issue by specifically monitoring FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry, not only in peripheral blood, but also in tissues. Interestingly, a significant increase of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells was found in PBLs of patients compared to HDs. A recent report on eight metastatic melanoma or renal carcinoma patients [1] and three healthy donors also hinted at such a difference. An even higher prevalence of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells was observed in our set of tumor-infiltrated tissues, while no difference was found in normal LNs, suggesting that the presence of tumor cells induced either the localized proliferation or the selective migration of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells to tumor-infiltrated sites. One possible scenario could be that high levels of cytokines (e.g., IL-2, CCL22, TGFβ) secreted by tumor cells possibly facilitate the attraction and local proliferation of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells, as well as the in situ conversion of CD4+ T cells into Tregs [19, 45, 52, 54]. In this way, tumor cells could favor their growth through a selective expansion of Tregs. Further studies are necessary to dissect these hypotheses in detail.

In agreement with previously published data [17, 44], we found a fraction of naive-phenotype Tregs in PBLs, in HDs, as well as in melanoma patients. Strikingly, we observed a selective decrease in the proportion of naive cells exclusively among FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells in TILN, and not among total CD4+ T cells. This observation points to tumor antigen-driven differentiation of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells. This would imply that certain tumor-associated antigens can possibly influence the balance of helper and regulatory T cell proliferation, homing and differentiation, and thus support a selective enrichment of FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells.

Finally, a parameter correlating with favorable clinical outcome and survival in cancer patients is the CD8+/Treg cell ratio present in the tumor microenvironment [36, 40]. Interestingly, in the group of melanoma patients analyzed here, the highest CD8+/FOXP3+ CD4+ T cell ratios were observed in two patients who showed the best clinical course (ratio of 13.3 and 10.9), while the remaining patients with progressing disease had clearly lower ratios (mean 1.8, range 0.5–3.5). A more accurate evaluation will only be possible once the ratio between CD8+/FOXP3+ CD4+ T cells on antigen-specific level can be calculated. Still, our data suggest a possible role of Treg in anti-tumor immunity and the necessity of further characterizing them in terms of specific marker expression, mechanism of inhibition, and antigen specificity. Thus, novel cancer vaccine formulations aiming to favor the expansion of helper CD4+ T cells, and to limit Treg cell expansion, should be evaluated in conjunction with CD8+ T cells and at the level of antigen-specific immune responses. This may increase the chance to identify correlations with clinical responses, and ultimately achieve increased clinical efficacy through immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Estelle Devêvre, Christine Geldhof, and Céline Beauverd for excellent technical assistance. C.J. was supported in part by an MD–PhD grant from SNF/Oncosuisse (no. 3236B0-108529) and by the NCCR Molecular Oncology program. G.B. and P.R. were supported in part by a grant from the European Union FP6 “cancerimmunotherapy”.

References

- 1.Ahmadzadeh M, Rosenberg SA. IL-2 administration increases CD4+ CD25(hi) Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Blood. 2006;107:2409–2414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anichini A, Vegetti C, Mortarini R. The paradox of T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity in spite of poor clinical outcome in human melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:855–864. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0526-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Liotta F, Lazzeri E, Manetti R, Vanini V, Romagnani P, Maggi E, Romagnani S. Phenotype, localization, and mechanism of suppression of CD4(+) CD25(+) human thymocytes. J Exp Med. 2002;196:379–387. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appay V, Jandus C, Voelter V, Reynard S, Coupland SE, Rimoldi D, Lienard D, Guillaume P, Krieg AM, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Leyvraz S, Rufer N, Speiser DE. New generation vaccine induces effective melanoma-specific CD8+ T cells in the circulation but not in the tumor site. J Immunol. 2006;177:1670–1678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arruvito L, Sanz M, Banham AH, Fainboim L. Expansion of CD4+CD25+and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: implications for human reproduction. J Immunol. 2007;178:2572–2578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacchetta R, Passerini L, Gambineri E, Dai M, Allan SE, Perroni L, Dagna-Bricarelli F, Sartirana C, Matthes-Martin S, Lawitschka A, Azzari C, Ziegler SF, Levings MK, Roncarolo MG. Defective regulatory and effector T cell functions in patients with FOXP3 mutations. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1713–1722. doi: 10.1172/JCI25112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett B, Kryczek I, Cheng P, Zou W, Curiel TJ. Regulatory T cells in ovarian cancer: biology and therapeutic potential. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005;54:369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennett CL, Christie J, Ramsdell F, Brunkow ME, Ferguson PJ, Whitesell L, Kelly TE, Saulsbury FT, Chance PF, Ochs HD. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, Yasayko SA, Wilkinson JE, Galas D, Ziegler SF, Ramsdell F. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cesana GC, DeRaffele G, Cohen S, Moroziewicz D, Mitcham J, Stoutenburg J, Cheung K, Hesdorffer C, Kim-Schulze S, Kaufman HL. Characterization of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients treated with high-dose interleukin-2 for metastatic melanoma or renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1169–1177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, Zhu Y, Wei S, Kryczek I, Daniel B, Gordon A, Myers L, Lackner A, Disis ML, Knutson KL, Chen L, Zou W. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dannull J, Su Z, Rizzieri D, Yang BK, Coleman D, Yancey D, Zhang A, Dahm P, Chao N, Gilboa E, Vieweg J. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Panfilis G, Campanini N, Santini M, Mori G, Tognetti E, Maestri R, Lombardi M, Froio E, Ferrari D, Ricci R. Phase- and stage-related proportions of T cells bearing the transcription factor FOXP3 infiltrate primary melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:676–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fecci PE, Mitchell DA, Whitesides JF, Xie W, Friedman AH, Archer GE, Herndon JE, 2nd, Bigner DD, Dranoff G, Sampson JH. Increased regulatory T-cell fraction amidst a diminished CD4 compartment explains cellular immune defects in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3294–3302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritzsching B, Oberle N, Pauly E, Geffers R, Buer J, Poschl J, Krammer P, Linderkamp O, Suri-Payer E. Naive regulatory T cells: a novel subpopulation defined by resistance toward CD95L-mediated cell death. Blood. 2006;108:3371–3378. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens, immune surveillance, and tumor immune escape. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:346–355. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghiringhelli F, Puig PE, Roux S, Parcellier A, Schmitt E, Solary E, Kroemer G, Martin F, Chauffert B, Zitvogel L. Tumor cells convert immature myeloid dendritic cells into TGF-beta-secreting cells inducing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell proliferation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:919–929. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffiths RW, Elkord E, Gilham DE, Ramani V, Clarke N, Stern PL, Hawkins RE. Frequency of regulatory T cells in renal cell carcinoma patients and investigation of correlation with survival. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(11):1743–1153. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0318-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harlin H, Kuna TV, Peterson AC, Meng Y, Gajewski TF. Tumor progression despite massive influx of activated CD8(+) T cells in a patient with malignant melanoma ascites. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1185–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ichihara F, Kono K, Takahashi A, Kawaida H, Sugai H, Fujii H. Increased populations of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with gastric and esophageal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4404–4408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jager E, Ringhoffer M, Altmannsberger M, Arand M, Karbach J, Jager D, Oesch F, Knuth A. Immunoselection in vivo: independent loss of MHC class I and melanocyte differentiation antigen expression in metastatic melanoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:142–147. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970410)71:2<142::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knutson KL, Disis ML, Salazar LG. CD4 regulatory T cells in human cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:271–285. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0194-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ling KL, Pratap SE, Bates GJ, Singh B, Mortensen NJ, George BD, Warren BF, Piris J, Roncador G, Fox SB, Banham AH, Cerundolo V. Increased frequency of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood and tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Immun. 2007;7:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, Zhu S, Gottlieb PA, Kapranov P, Gingeras TR, de St Groth BF, Clayberger C, Soper DM, Ziegler SF, Bluestone JA. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4(+) T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, Tanaka Y, Herrmann V, Doherty G, Drebin JA, Strasberg SM, Eberlein TJ, Goedegebuure PS, Linehan DC. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:2756–2761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller AM, Lundberg K, Ozenci V, Banham AH, Hellstrom M, Egevad L, Pisa P. CD4+CD25high T cells are enriched in the tumor and peripheral blood of prostate cancer patients. J Immunol. 2006;177:7398–7405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miracco C, Mourmouras V, Biagioli M, Rubegni P, Mannucci S, Monciatti I, Cosci E, Tosi P, Luzi P. Utility of tumour-infiltrating CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cell evaluation in predicting local recurrence in vertical growth phase cutaneous melanoma. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:1115–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mourmouras V, Fimiani M, Rubegni P, Epistolato MC, Malagnino V, Cardone C, Cosci E, Nisi MC, Miracco C. Evaluation of tumour-infiltrating CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in human cutaneous benign and atypical naevi, melanomas and melanoma metastases. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:531–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura K, Kitani A, Strober W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+) CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 2001;194:629–644. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petersen RP, Campa MJ, Sperlazza J, Conlon D, Joshi MB, Harpole DH, Jr, Patz EF., Jr Tumor infiltrating Foxp3(+) regulatory T-cells are associated with recurrence in pathologic stage I NSCLC patients. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2866–2872. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfoertner S, Jeron A, Probst-Kepper M, Guzman CA, Hansen W, Westendorf AM, Toepfer T, Schrader AJ, Franzke A, Buer J, Geffers R. Signatures of human regulatory T cells: an encounter with old friends and new players. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R54. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pittet MJ, Valmori D, Dunbar PR, Speiser DE, Lienard D, Lejeune F, Fleischhauer K, Cerundolo V, Cerottini JC, Romero P. High frequencies of naive Melan-A/MART-1-specific CD8(+) T cells in a large proportion of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2 individuals. J Exp Med. 1999;190:705–715. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Curran MA, Allison JP. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roncador G, Brown PJ, Maestre L, Hue S, Martinez-Torrecuadrada JL, Ling KL, Pratap S, Toms C, Fox BC, Cerundolo V, Powrie F, Banham AH. Analysis of FOXP3 protein expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells at the single-cell level. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1681–1691. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruprecht CR, Gattorno M, Ferlito F, Gregorio A, Martini A, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Coexpression of CD25 and CD27 identifies FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in inflamed synovia. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1793–1803. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sakaguchi S, Toda M, Asano M, Itoh M, Morse SS, Sakaguchi N. T cell-mediated maintenance of natural self-tolerance: its breakdown as a possible cause of various autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:211–220. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sato E, Olson SH, Ahn J, Bundy B, Nishikawa H, Qian F, Jungbluth AA, Frosina D, Gnjatic S, Ambrosone C, Kepner J, Odunsi T, Ritter G, Lele S, Chen YT, Ohtani H, Old LJ, Odunsi K. Intraepithelial CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and a high CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio are associated with favorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18538–18543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509182102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, Zaunders J, Sasson S, Landay A, Solomon M, Selby W, Alexander SI, Nanan R, Kelleher A, Fazekas de St Groth B. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1693–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strauss L, Bergmann C, Szczepanski M, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. A Unique Subset of CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ T Cells Secreting Interleukin-10 and Transforming Growth Factor-{beta}1 Mediates Suppression in the Tumor Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4345–4354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugimoto N, Oida T, Hirota K, Nakamura K, Nomura T, Uchiyama T, Sakaguchi S. Foxp3-dependent and -independent molecules specific for CD25+CD4+ natural regulatory T cells revealed by DNA microarray analysis. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1197–1209. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valmori D, Merlo A, Souleimanian NE, Hesdorffer CS, Ayyoub M. A peripheral circulating compartment of natural naive CD4 Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1953–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI23963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valzasina B, Piconese S, Guiducci C, Colombo MP. Tumor-induced expansion of regulatory T cells by conversion of CD4+CD25− lymphocytes is thymus and proliferation independent. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4488–4495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Viguier M, Lemaitre F, Verola O, Cho MS, Gorochov G, Dubertret L, Bachelez H, Kourilsky P, Ferradini L. Foxp3 expressing CD4+CD25(high) regulatory T cells are overrepresented in human metastatic melanoma lymph nodes and inhibit the function of infiltrating T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1444–1453. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wan YY, Flavell RA. Identifying Foxp3-expressing suppressor T cells with a bicistronic reporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5126–5131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei S, Kryczek I, Edwards RP, Zou L, Szeliga W, Banerjee M, Cost M, Cheng P, Chang A, Redman B, Herberman RB, Zou W. Interleukin-2 administration alters the CD4+FOXP3+ T-cell pool and tumor trafficking in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7487–7494. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woo EY, Yeh H, Chu CS, Schlienger K, Carroll RG, Riley JL, Kaiser LR, June CH. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells from lung cancer patients directly inhibit autologous T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2002;168:4272–4276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu Y, Borde M, Heissmeyer V, Feuerer M, Lapan AD, Stroud JC, Bates DL, Guo L, Han A, Ziegler SF, Mathis D, Benoist C, Chen L, Rao A. FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT. Cell. 2006;126:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yagi H, Nomura T, Nakamura K, Yamazaki S, Kitawaki T, Hori S, Maeda M, Onodera M, Uchiyama T, Fujii S, Sakaguchi S. Crucial role of FOXP3 in the development and function of human CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1643–1656. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang ZZ, Novak AJ, Stenson MJ, Witzig TE, Ansell SM. Intratumoral CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+ T cells in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2006;107:3639–3646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zippelius A, Batard P, Rubio-Godoy V, Bioley G, Lienard D, Lejeune F, Rimoldi D, Guillaume P, Meidenbauer N, Mackensen A, Rufer N, Lubenow N, Speiser D, Cerottini JC, Romero P, Pittet MJ. Effector function of human tumor-specific CD8 T cells in melanoma lesions: a state of local functional tolerance. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2865–2873. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]