Abstract

Introduction

There is mounting evidence describing the immunosuppressive role of bulky metastatic disease, thus countering the therapeutic effects of tumor vaccine. Therefore, adjuvant immunotherapy may have a better impact on clinical outcome. In this phase II clinical trial, we aimed to test the feasibility of using a specific mutant ras peptide vaccine as an adjuvant immunotherapy in pancreatic and colorectal cancer patients.

Materials and methods

Twelve patients with no evidence of disease (NED), five pancreatic and seven colorectal cancer patients were vaccinated subcutaneously with 13-mer mutant ras peptide, corresponding to their tumor’s ras mutation. Vaccinations were given every 4 weeks, up to a total of six vaccines.

Results

No serious acute or delayed systemic side effects were seen. We detected specific immune responses to the relevant mutant ras peptide by measuring IFN-gamma mRNA expression by quantitative real-time PCR. Five out of eleven patients showed a positive immune response. Furthermore, the five pancreatic cancer patients have shown a mean disease-free survival (DFS) of 35.2+ months and a mean overall survival (OS) of 44.4+ months. The seven colorectal cancer patients have shown a mean disease-free survival (DFS) of 27.2+ months and a mean overall survival (OS) of 41.5+ months.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that it is feasible to use mutant ras vaccine in the adjuvant setting. This vaccine is safe, can induce specific immune responses, and it appears to have a positive outcome in overall survival. Therefore, we believe that such an approach warrants further investigation in combination with other therapies.

Keywords: Mutant ras, Adjuvant, Immunotherapy, Pancreatic cancer, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

Ras mutations are prevalent in many types of adenocarcinomas including pancreatic (∼90%), colorectal (∼50%), lung cancers (∼30%), and thyroid cancers (∼50%).

Ras is mutated by a single amino acid substitution of codon 12 in 90% of cases [1–3]. Like most proteins in nucleated cells, ras is subject to the endogenous pathway of antigen processing and presentation by both MHC class I or II molecules [4, 5]. The products of mutant ras provide a potential target for cancer immunotherapy due to their peculiar expression in tumor tissue, as compared to normal counterpart. This immune susceptibility is furthermore powered by the ability exerted by T cells to detect single amino-acid substitution.

In vitro priming of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with mutant ras peptides can generate specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cell responses [6–10]. Furthermore, some clinical trials have shown that mutant ras peptide vaccination can generate specific immune response in cancer patients. The peptides used in these studies spanned 10–17 amino-acids in length and vaccinated patients developed both CD8 and CD4 responses in the context of HLA class I (A2, B35) and HLA class II (DR6, DQ2, DP), respectively [11–15].

In a previous phase I clinical trial, our group showed that when administered subcutaneously with adjuvant, the 13-mer mutant ras (aa5–17) peptides reflecting the patients’ mutations, were able to generate CD4+ proliferative responses to the corresponding peptide but not to the wild type. CD8+ responses were also found against a nested HLA-A2 10-mer peptide (aa5–14) in patients who carried the HLA-A2 allele. A dose up to 5,000 μg was well tolerated [12]. Patients on the study had advanced diseases. None of which has demonstrated clinical responses despite the specific immune responses generated.

No vaccine studies in advanced diseases have yet shown a positive effect of tumor response or survival benefit. This may partly due to immunosuppressive effect of tumors [16, 17]. Accordingly, vaccine treatment, when given in the adjuvant setting, may significantly improve the clinical outcome [18–20].

Here, in this phase II trial, we tested the mutant ras peptide immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting in pancreatic and colorectal cancer patients. We have chosen the highest dose administered in our previous phase I to be given subcutaneously in combination with a lipid-based adjuvant. We determined the toxicity spectrum of such peptides given, the immune responses generated, and as a secondary end point we assessed any tumor response that may occur with this adjuvant therapy for future exploration.

Patients and methods

Study design

This is a phase II/pilot study to determine the feasibility of a mutated ras peptide (aa5–17) as adjuvant immunotherapy in colorectal and pancreatic cancer patients with no evidence of disease (NED).

All patients enrolled in this study had histological diagnosis of a solid tumor expressing mutant ras. The ras mutations detected are specific point mutations in codon 12 leading to amino-acids substitution as follows: glycine (Gly) versus cysteine (Cys), Gly versus aspartic acid (Asp), or Gly versus valine (Val).

Patients did not receive any chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy or steroids for at least 4 weeks prior to vaccination. Patients were 18 years and older. NED was confirmed upon entry to the protocol by radiological testing. All patients had ECOG performance status of 0–1, were HIV, hepatitis B, C negative and had no laboratory evidence of organ dysfunction. All patients were tested for the presence of positive skin reaction against common antigens in a skin anergy panel (Candida, Mumps, TB, and Tetanus).

Both the National Cancer institute (NCI) and National Naval Medical Center (NNMC), Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), approved the protocol and the patients’ consent was obtained prior to enrollment.

Determining ras mutation

DNA was isolated from tumor tissue preserved in paraffin blocks. The DNA was PCR amplified by applying a two-stage procedure. K-ras mutations were determined by Bst NI digestion [11, 12].

The sequences of the PCR primers were as follows:

5′-ACT-GAA-TAT-AAA-CTT-GTG-GTA-GTT-GGA-CCT-3′ (forward primer for first and second PCR)

5′-TCA-AAG-AAT-GGT-CCT-GCA-CC-3′ (reverse primer for the first PCR)

5′-TAA-TAT-GCA-TAT-TAA-AAC-AAG-ATT-TAC-CTC-3′ (reverse primer for the second PCR).

The second PCR products were sequenced using the dye terminator method on the 377-sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The specimens were sequenced with the reverse primer from the second PCR and with a shortened version of the forward primer; 5′-ACT-GAA-TAT-AAA-CTT-GTG-GT-3′.

Vaccination

Patients received 13-mer mutant ras peptide, spanning aa5–17, corresponding to mutation carried by their tumor (Multiple Peptide System, CA). The sequences were:

(ras12Cys: KLVVVGACGVGKS; ras12Val: KLVVVGAVGVGKS; ras12Asp: KLVVVGADGVGKS).

Lyophilized ras peptide (5,000 μg) was admixed with 1.5 mL DETOX™. DETOX™ is composed of 250 μg cell wall skeleton of Mycobacterium phlei and 25 μg monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) from Salmonella Minnesota R 595 (Ribi ImmunoChem Research, Inc.Hamilton, Montana). 0.5 mL of the peptide-DETOX™ was injected subcutaneously at each of three separate sites (arms, or thighs). The vaccine was administered every 4 weeks to the maximum of six vaccinations or until disease progression.

Cell collection and preparation for quantitative real-time PCR

At least 5 × 106 PBMCs were collected prior to vaccination and after each vaccination. Ficoll–Hypaque density gradient centrifugation was performed (Lymphocyte Separation Medium; Organon-Teknika, Durham, NC) to isolate PBMCs from heparinized blood. Cells were cryopreserved until use. When needed, PBMCs were thawed simultaneously with similar recovery conditions, washed and 1 × 106 mL−1 were plated in a 96 U-Bottom well plate with 200 μL RPMI complete media [with 5% heat inactivated human albumin (Gemini Bio-Products), 1% MEM sodium pyruvate (Gibco)]. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C (humidity 90%, CO2 5%) to minimize background expression of IFN-γ mRNA due to cell manipulation. PBMCs were then stimulated with different peptides at a final concentration of 5 μg/mL and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. Cells were harvested and total RNA was immediately extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, USA). Accurately, 5 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into c-DNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen).

Quantitative real-time PCR

We used an ABI prism 7900 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA, USA) to measure the IFN-γ gene expression (gene of interest). Primers and TaqMan probes (Perkin-Elmer) were designed to span exon–intron junctions to prevent amplification of genomic DNA and to produce amplicons <150 bp in length, thus enhancing the efficiency of PCR amplification [21].

A reporter dye molecule FAM (6-carboxyfluorecein; emission λ max = 518 nm) was used to label the TaqMan probes at the 5′-end and the 3′-end was labeled with the quencher dye molecule TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine; emission λ max = 582 nm).

We used IFN-gamma as reference gene and b-actin as housekeeping gene. The sequences for primers and probes used in the real-time PCR are as follows:

| b-Actin | FWD 5′-GGCACCCAGCACAATGAAG-3′ |

| REV 5′-GCCGATCCACACGGAGTACT-3′ | |

| Probe 5′-TCAAGATCATTGCTCCTCCTGAGCGC-3′ | |

| IFN-γ | FWD 5′-AGCTCTGCATCGTTTTGGGTT-3′ |

| REV 5′-GTTCCATTATCCGCTACATCTGAA-3′ | |

| Probe 5′-TCTTGGCTGTTACTGCCAGGACCCA-3′ |

For the standard curve, we generated cDNA by reverse transcriptase using the same technique that we used for the preparation of test cDNA. c-DNA for IFN-γ and b-actin genes were amplified by the means of regular PCR using the same primers designed for the TaqMan. After that, the amplified c-DNA was purified and quantitated by spectrophotometry (OD260). We used the molecular weight of each gene amplicon to calculate the number of c-DNA copies and serial dilutions of the amplified gene at known concentration were done and tested by quantitative real-time PCR (q-rt PCR).

The final TaqMan reactions for the standard curve c-DNA and for the test samples c-DNA were conducted using 2 μL c-DNA in 50 μL total volume mixture with primers and probes at optimized concentration (400 and 200 nM, respectively) and 1× TaqMan Master Mix (Perkin-Elmer). Thermal cycler parameters were 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C and 40 cycles involving denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C. All the assays were performed in duplicate and reported as the average.

Statistical analysis

Survival data analyses were performed using the Kaplan–Meier methods and P values were assessed using the exact long-rank test. The confidence intervals for survival probabilities are estimated by the Rothman method [22].

We consider the fold change of specific immune responses from pre-vaccination to post-vaccination as indication for vaccine efficacy. Fold change of IFN-γ was calculated by using the ratio of absolute copies number of IFN-γ obtained by stimulation with mutant ras peptides, relative to absolute copies number of IFN-γ obtained wild type ras peptides stimulation. (IFN-γ copies number were normalized with b-actin copies number with the same stimulant.)

|

|

Two-fold or more increase at any time point post-vaccination in comparison to pre-vaccination was considered a positive immune response.

Results

Patient profiles

Twelve patients were enrolled in this study. The age of patients ranged between 38 and 71. Five patients had pancreatic cancer and seven had colorectal cancer. Two patients carried the ras-12Val mutation (patients 7, 10), while the remaining patients carried the ras-12Asp mutation in their tumors. HLA types varied among patients.

All patients were (NED) at the time of enrollment with varying disease stages at diagnosis. Four of the seven colorectal cancer patients (patients 4, 8, 11, and 12) had stage III at diagnosis, underwent hemicolectomy, and received 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin as adjuvant therapy. The remaining three colorectal cancer patients (patients 1, 2, and 9) had stage IV at diagnosis, and received 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (patient 2), or hemicolectomy plus standard 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin as adjuvant therapy (patient 1) or the same protocol followed by lymph node metastectomy and radiotherapy (patient 9).

Four of the five pancreatic cancer patients, (patients 3, 5, 6, and 7) had stage III at diagnosis while patient 10 had stage II. The pancreatic cancer patients were previously treated with surgery alone (patients 5, and 10) or in combination with radiochemotherapy (patients 3, 6, and 7) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data, clinical characteristics and previous treatments the patients received before vaccination

| Patient | Age/sex | Cancer type | Stage | Ras mutation | Prior treatment | Time from prior Tx to vaccine (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50/M | Colorectal | IV | Asp | Hemicolectomy, 5-FU/LV for 6 months, followed by resection of abdominal wall mass | 10 |

| 2 | 57/F | Colorectal | IV | Asp | 5-FU/LV for 12 months | 5 |

| 3 | 49/M | Pancreas | III | Asp | Whipple, XRT for 1 month, 5-FU/LV for 6 months | 12 |

| 4 | 64/M | Colorectal | III | Asp | Left hemicolectomy, 5-FU/LV for 6 months | 8 |

| 5 | 71/F | Pancreas | III | Asp | Partial pancreatectomy | 6 |

| 6 | 68/F | Pancreas | III | Asp | Whipple with IORT, concurrent XRT/5-FU for 5 weeks, gemcitabine for 6 months | 5 |

| 7 | 49/M | Pancreas | III | Val | Whipple, 5-FU for 1 month, then concurrent XRT/5-FU for 1 month, then 5-FU for 3 months | 4 |

| 8 | 56/F | Colorectal | III | Asp | Hemicolectomy, 5-FU/LV for 6 months | 5 |

| 9 | 38/M | Colorectal | IV | Asp | Right hemicolectomy, camptosar/5-FU/LV for 6 months, cervical lymph node metastectomy, cervical XRT | 1.5 |

| 10 | 67/M | Pancreas | II | Val | Whipple | 1.5 |

| 11 | 57/F | Colorectal | III | Asp | Hemicolectomy, 5-FU/LV for 6 months | 10 |

| 12 | 43/F | Colorectal | III | Asp | Segmental resection of the transverse colon, 5-FU/LV for 6 months | 2 |

M male, F female, Asp patient has the ras mutation in codon 12 Gly to Asp, Val patient has the ras mutation in codon 12 Gly to Va, 5-FU 5-fluorouracil, LV leucovorin, XRT radiotherapy, IORT intraoperative radiotherapy

All patients showed a positive response to at least one of the antigens used in the anergy skin test as a crude measure of cellular immune competency. CD4 counts at entrance to the trial ranged between 90 and 1,228, CD8 counts were between 47 and 450.

Mutant ras peptides: vaccination generated specific immune response

Out of the 12 patients enrolled in the trial; we were able to measure the immune responses in 11 patients. Patient 1 received only two cycles after which he developed partial blockage in the small intestine and was taken off study.

We tested the immunological response by q-rt PCR in all the 11 patients who completed a minimum of three vaccinations. Standard curves obtained for both the reference gene IFN-γ and housekeeping gene b-actin, showed a PCR amplification efficiency >90% as determined by the slope, and the linear regression analysis showed that r 2 for all standard curves was >0.99.

We measured the expression of IFN-γ by detecting the number of mRNA copies isolated from specimens harvested after 3 or 6 h of stimulation with peptides. Due to the fact that IFN-γ m-RNA copy numbers did not differ significantly between the two time points analyzed, the 3-h stimulation was used for the rest of the samples and this result correlates with what was previously reported [23, 24].

Furthermore, a peptide dose titration was performed to obtain the optimum peptide concentration to use for stimulation. We found an increase of IFN-γ mRNA copies when using 5 or 10 μg of the peptide compared to 0.5 or 1 μg; thus, the peptide concentration used was 5 μg.

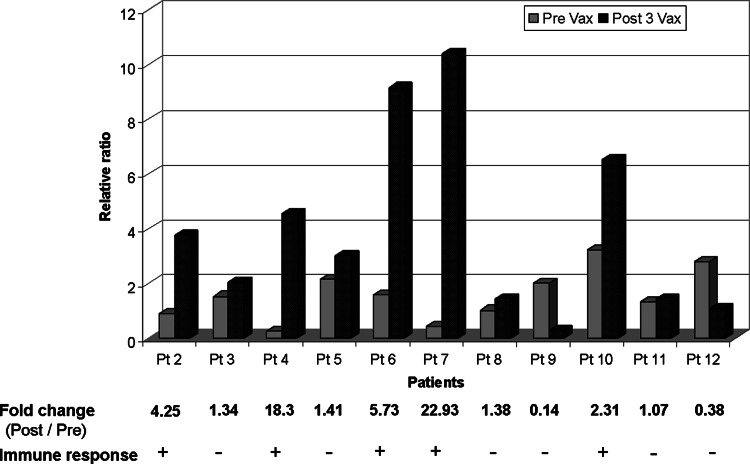

For the 11 patients, PBMCs were stimulated ex vivo with their specific 13-mer mutant ras peptide (ras12Asp/ras12Val), the wild type 13-mer ras peptide (WT, ras12Gly KLVVVGAGGVGKS) or incubated without peptide. Anti-CD3 Ab stimulation was used as a positive control to detect viability and reactivity of the PBMCs. Out of the 11 patients tested (patients 2, 4, 6, 7, and 10) five showed a twofold or more increase in IFN-γ copy numbers accumulation in PBMCs collected post-vaccination when stimulated with the corresponding mutant ras peptide in comparison to PBMCs collected pre-vaccination (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Immune response against the 13-mer corresponding mutant ras. q r-t PCR on PBMCs collected before vaccination (Pre-Vax) and after three vaccinations (Post-3Vax). Y axis values represent ratio of absolute IFN-γ mRNA copy numbers obtained by mutant ras peptide stimulation relative to wild type ras peptide stimulation, normalized with b-actin. Plus symbol indicates twofold increase or more of IFN-γ mRNA copies post-vaccination

In our previous study, we have shown that HLA-A2 patients can generate CD8+ immune response against a nested 10-mer mutant ras peptide (aa5–14) [12]. Here, we have attempted to re-duplicate that observation. Accordingly, we tested PBMCs from one of the HLA-A2 patients (patient 6), who carries the Asp mutation, against the nested HLA-A2 10-mer spanning amino acids 5–14 (ras-12Asp KLVVVGADGV) mutant ras peptide and the 10-mer WT (ras-12Gly KLVVVGAGGV). We found that, by stimulation of PBMCs ex vivo with the 10-mer corresponding peptide, we can detect an increase of 3.8-folds in IFN-γ mRNA copies after three vaccinations (Data not shown).

Side effects

The vaccine was well tolerated among patients; no serious systemic side effects were observed nor have delayed toxicities occurred. We observed Grade I or II injection site reaction in seven patients, which was consistent with the local reactions seen in DETOX™ adjuvant, alone. Also Grade I or II fever was reported in two patients. Three patients developed mild fatigue and one patient had a grade II rash. Other sporadic side effects including diarrhea, constipation, abdominal discomfort, and myalgia were observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Side effects seen in patients and its frequencies

| Side effect | Grade | Number of patients with side effect | Frequency of side effect in total number of vaccine cycle (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Injection site reaction | 1 or 2 | 7 | 25 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 3 | 13 |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 3 | 10 |

| Abdominal discomfort | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Constipation | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Fever | 1 or 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Myalgia | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Rash | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Clinical outcome

Of the 11 evaluable patients, 9 completed six vaccinations. Patient 3 completed three cycles of vaccination and was taken off study because of progressive disease in the form of lung relapse. Patient 9 went off study after three cycles of vaccination due to progressive primary disease. Of nine patients who completed all six vaccinations, seven patients remained NED, patients 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12 for 73+, 64+, 47+, 39+, 36+, 35+, and 35+ months, respectively, from the date of enrollment (first vaccine administration). Two patients progressed 6 and 11 months after enrollment; patient 2 developed liver metastases and patient 5 developed lung metastases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of vaccinations, immune responses, survival and clinical outcome

| Patient | Number of vaccinations | Immune response | DFS | OS | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | NT | 1.5 | 13 | Progressed |

| 2 | 6 | Positive | 6 | 85 | Progressed |

| 3 | 3 | Negative | 18 | 55 | Progressed |

| 4 | 6 | Positive | 73+ | 73+ | Remained NED |

| 5 | 6 | Negative | 11 | 20 | Progressed |

| 6 | 6 | Positive | 64+ | 64+ | Remained NED |

| 7 | 6 | Positive | 47+ | 47+ | Remained NED |

| 8 | 6 | Negative | 39+ | 39+ | Remained NED |

| 9 | 3 | Negative | 4 | 14 | Progressed |

| 10 | 6 | Positive | 36+ | 36+ | Remained NED |

| 11 | 6 | Negative | 35+ | 35+ | Remained NED |

| 12 | 6 | Negative | 32+ | 32+ | Remained NED |

DFS disease free survival (calculated as time from the first vaccination until evidence of cancer progression), OS overall survival (calculated as time from the first vaccination until death), + patient still alive, NED no evidence of disease, NT not tested

The five pancreatic cancer patients have a mean disease free survival (DFS) of 35.2+ months and a mean overall survival (OS) of 44.4+ months. The seven colorectal cancer patients have a mean DFS of 27.2+ months and a mean OS of 41.5+ months. The median potential follow-up in this study was 56.3 months. Furthermore, the estimated DFS probabilities at 5 years were 60% for pancreatic cancer patients (95% confidence interval, 23–88%) and 57% for colorectal cancer patients (95% confidence interval, 25–84%). The estimated OS probabilities at 5 years were 40% for pancreatic cancer patients (95% confidence interval, 8–84%) and 71% for colorectal cancer patients (95% confidence interval, 36–92%).

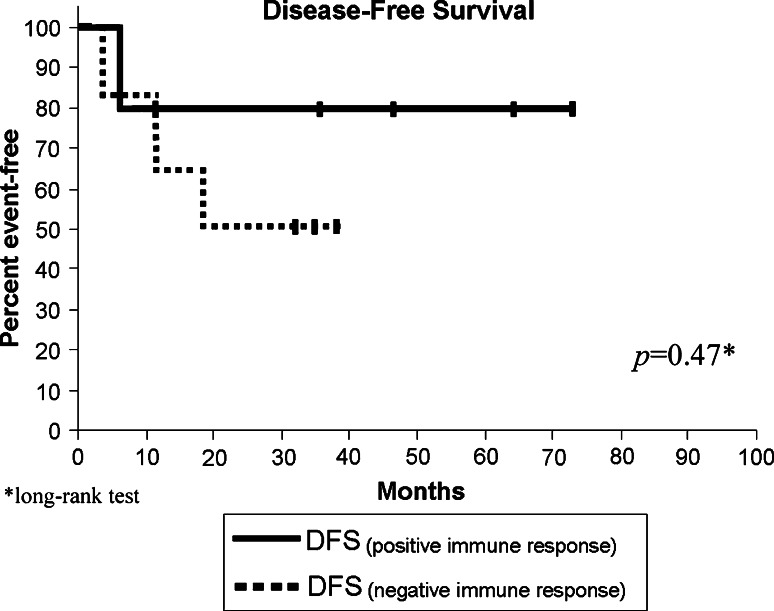

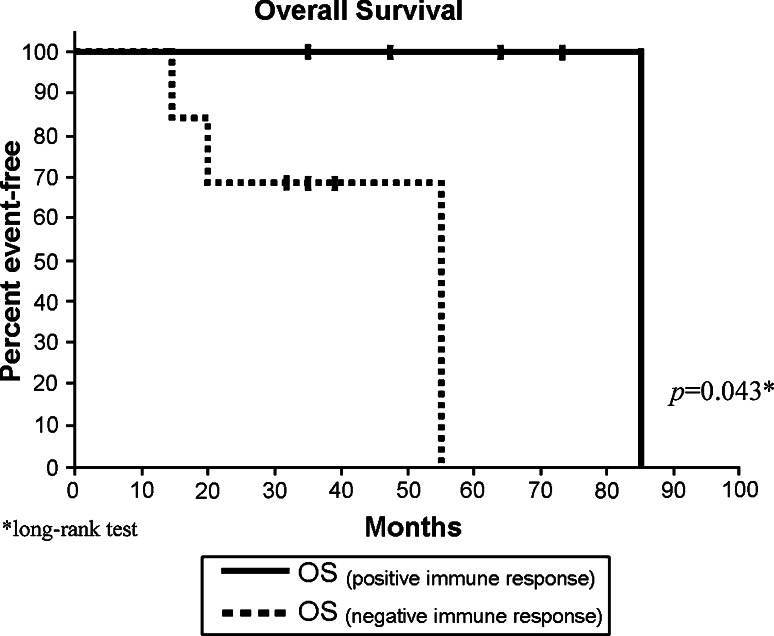

Furthermore, we analyzed the effect of the generation of a positive immune response on the DFS and the OS, Fig. 2 shows Kaplan–Meier estimates for (DFS) for patients with detected immune response compared to patients with no immune response detected, we found no statistical difference between the two groups (P = 0.47). However, when we compared the effect of the generation of immune response on the OS, we found that there is a marginal statistical significance amongst the two groups. Figure 3 shows Kaplan–Meier graph with a P value of 0.043.

Fig. 2.

Disease free survival. Kaplan–Meier, estimated DFS of patients with immune response compared to patients with no immune response. P values were assessed using the exact long-rank test. DFS, disease free survival—calculated as time from the first vaccination until evidence of disease progression. Vertical lines indicate the patient is still alive at last assessment

Fig. 3.

Overall survival. Kaplan–Meier, estimated OS of patients with immune response compared to patients with no immune response. P values were assessed using the exact long-rank test. OS, overall survival—calculated as time from the first vaccination until death. Vertical lines indicate the patient is still alive at last assessment

Discussion

Most of clinical trials utilizing cancer vaccines have been conducted in patients with advanced disease. None of these studies have yet shown any significant tumor response or survival benefit. Others and we believe that it is difficult for vaccine treatment, when given alone, to be able to influence outcome in advanced disease [16, 17]. In contrast, when given in the adjuvant setting, vaccine may have a better chance of improving clinical outcome [18–20]. Here, we aimed to test the feasibility of using mutant ras peptide as immunotherapy in the adjuvant setting.

In a previous phase I study [12], we treated patients with advanced disease with up to 5,000 μg of the 13-mer mutant ras peptide. We generated specific immune responses, and no short-term toxicities have been observed. Accordingly, on this study, we enrolled patients who were NED and treated them subcutaneously with 5,000 μg of mutant ras peptide mixed with DETOX™ adjuvant. Patients received up to six cycles of vaccination.

The vaccine was well tolerated and no serious acute side effects were observed. Being administered in the adjuvant setting, it provided us the opportunity to follow up patients for longer time to assess for delayed toxicities which also were not seen.

Furthermore, we found that specific immune responses were generated in 45% of patients (5 out of 11 tested). Carbone et al. also reported specific immune responses in 38% of patients treated with mutant ras peptides (8 out of 21 tested including 3 patients were treated on adjuvant basis). On that trial, the mutant ras peptides (17aa) were pulsed on autologous PBMCs and administered intravenously [15]. Here, we administered our vaccine subcutaneously. However, we believe the s.c. route we used has the advantages of flexibility in adjusting the peptide dose and ease of preparation compared to pulsed APCs.

In this study, we applied a quantitative real-time PCR assay to test the immune responses generated against class II peptides. We were able to detect an increase in IFN-γ transcript accumulation in T cells obtained after vaccination with only 3 h of in vitro stimulation. In contrast, in our previously reported trial and others’, multiple in vitro stimulations of post-vaccination lymphocytes were required to be able to detect peptide-specific reactivity [11, 12, 14, 15]. Accordingly, we believe this assay may represent a more sensitive method to detect the peptide specific responses and better reflecting the in vivo responsiveness and the efficacy of the vaccine.

Other groups have used vaccine as adjuvant immunotherapy. Gjertsen et al. reported a mean survival of 25.6 months for the ten surgically resected pancreatic cancer patients they treated with a 17mer mutant ras peptide (aa5–21) intradermaly with GM-CSF [14]. Also, Jaffee et al. reported a mean DFS of 13 months for patients with stage II and III surgically resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma vaccinated with GM-CSF secreting tumor-cell vaccine [25]. In this study, although evaluation of the clinical outcome was not a primary objective, we found that the five pancreatic cancer patients have shown a mean DFS of 35.2+ months and a mean OS of 44.4+ months. The seven colorectal cancer patients have shown a mean DFS of 27.2+ months and a mean OS of 41.5+ months. Yet, this study is not designed to make a definitive survival assessment and has small number of patients. And the patients’ longer survival in this study is only an observation that worth highlighting. We also found that four patients (57%) of seven who remain NED generate specific immune responses against the vaccine; only one patient (25%) from the four progressors generates specific immune responses after vaccination. However, this correlation is not statistically significant.

Furthermore, we looked at the correlation between survival and the presence of specific immune response generated after vaccination. We compared DFS and OS in patients who generated an immune response and patients with no detected immune response. Although there was a tendency for DFS to be higher in the positive responders, the difference in DFS between both groups was found to be not significant (P = 0.47). In contrast, The OS was found to be higher in the responders with marginally statistical significance with a P value of 0.043, which may indicate better clinical outcomes for responders.

We believe applying the cancer vaccine as adjuvant has a better chance to generate more adequate and effective immune response and could have a positive impact on patients’ survival. Hence, adjuvant immunotherapy warrants more exploration in this setting alone and in combination with chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The investigators thank Dr. Jay A. Berzofsky, Dr. Scott Abrams and Dr. Walter Urba for the valuable review of the paper.

References

- 1.Hruban RH, van Mansfeld AD, Offerhaus GJ, van Weering DH, Allison DC, Goodman SN, et al. K-ras oncogene activation in adenocarcinoma of the human pancreas. A study of 82 carcinomas using a combination of mutant-enriched polymerase chain reaction analysis and allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization. Am J Pathol. 1993;143(2):545–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li ZH, Zheng J, Weiss LM, Shibata D. c-k-ras and p53 mutations occur very early in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Am J Pathol. 1994;144(2):303–309. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breivik J, Meling GI, Spurkland A, Rognum TO, Gaudernack G. K-ras mutation in colorectal cancer: relations to patient age, sex and tumour location. Br J Cancer. 1994;69(2):367–371. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss S, Bogen B. MHC class II-restricted presentation of intracellular antigen. Cell. 1991;64(4):767–776. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90506-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jardetzky TS, Lane WS, Robinson RA, Madden DR, Wiley DC. Identification of self peptides bound to purified HLA-B27. Nature. 1991;353(6342):326–329. doi: 10.1038/353326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrams SI, Stanziale SF, Lunin SD, Zaremba S, Schlom J. Identification of overlapping epitopes in mutant ras oncogene peptides that activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(2):435–443. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fossum B, Gedde-Dahl T, 3rd, Breivik J, Eriksen JA, Spurkland A, Thorsby E, et al. p21-ras-peptide-specific T-cell responses in a patient with colorectal cancer. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognize a peptide corresponding to a common mutation (13Gly → Asp) Int J Cancer. 1994;56(1):40–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fossum B, Olsen AC, Thorsby E, Gaudernack G. CD8+ T cells from a patient with colon carcinoma, specific for a mutant p21-Ras-derived peptide (Gly13 → Asp), are cytotoxic towards a carcinoma cell line harbouring the same mutation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;40(3):165–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01517348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gedde-Dahl T, 3rd, Fossum B, Eriksen JA, Thorsby E, Gaudernack G. T cell clones specific for p21 ras-derived peptides: characterization of their fine specificity and HLA restriction. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(3):754–760. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Elsas A, Nijman HW, Van der Minne CE, Mourer JS, Kast WM, Melief CJ, et al. Induction and characterization of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes recognizing a mutated p21ras peptide presented by HLA-A*0201. Int J Cancer. 1995;61(3):389–396. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams SI, Khleif SN, Bergmann-Leitner ES, Kantor JA, Chung Y, Hamilton JM, et al. Generation of stable CD4+ and CD8+ T cell lines from patients immunized with ras oncogene-derived peptides reflecting codon 12 mutations. Cell Immunol. 1997;182(2):137–151. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khleif SN, Abrams SI, Hamilton JM, Bergmann-Leitner E, Chen A, Bastian A, et al. A phase I vaccine trial with peptides reflecting ras oncogene mutations of solid tumors. J Immunother. 1999;22(2):155–165. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gjertsen MK, Bakka A, Breivik J, Saeterdal I, Solheim BG, Soreide O, et al. Vaccination with mutant ras peptides and induction of T-cell responsiveness in pancreatic carcinoma patients carrying the corresponding RAS mutation. Lancet. 1995;346(8987):1399–1400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92408-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gjertsen MK, Buanes T, Rosseland AR, Bakka A, Gladhaug I, Soreide O, et al. Intradermal ras peptide vaccination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor as adjuvant: clinical and immunological responses in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2001;92(3):441–450. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carbone DP, Ciernik IF, Kelley MJ, Smith MC, Nadaf S, Kavanaugh D, et al. Immunization with mutant p53- and K-ras-derived peptides in cancer patients: immune response and clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5099–5107. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh CL, Chen DS, Hwang LH. Tumor-induced immunosuppression: a barrier to immunotherapy of large tumors by cytokine-secreting tumor vaccine. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11(5):681–692. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mocellin S, Wang E, Marincola FM. Cytokines and immune response in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother. 2001;24(5):392–407. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mocellin S, Rossi CR, Lise M, Marincola FM. Adjuvant immunotherapy for solid tumors: from promise to clinical application. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51(11–12):583–595. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0308-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoover HC, Jr, Brandhorst JS, Peters LC, Surdyke MG, Takeshita Y, Madariaga J, et al. Adjuvant active specific immunotherapy for human colorectal cancer: 6.5-year median follow-up of a phase III prospectively randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):390–399. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris JE, Ryan L, Hoover HC, Jr, Stuart RK, Oken MM, Benson AB, 3rd, et al. Adjuvant active specific immunotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer with an autologous tumor cell vaccine: Eastern cooperative oncology group study E5283. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(1):148–157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kammula US, Lee KH, Riker AI, Wang E, Ohnmacht GA, Rosenberg SA, et al. Functional analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes by serial measurement of gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor specimens. J Immunol. 1999;163(12):6867–6875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothman KJ. Estimation of confidence limits for the cumulative probability of survival in life table analysis. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(8):557–560. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Provenzano M, Mocellin S, Bettinotti M, Preuss J, Monsurro V, Marincola FM, et al. Identification of immune dominant cytomegalovirus epitopes using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reactions to measure interferon-gamma production by peptide-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunother. 2002;25(4):342–351. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200207000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Provenzano M, Mocellin S, Bonginelli P, Nagorsen D, Kwon SW, Stroncek D. Ex vivo screening for immunodominant viral epitopes by quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) J Transl Med. 2003;1(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaffee EM, Hruban RH, Biedrzycki B, Laheru D, Schepers K, Sauter PR, et al. Novel allogeneic granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic cancer: a phase I trial of safety and immune activation. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):145–156. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]