Abstract

Innate immune stimulation with Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists is a proposed modality for immunotherapy of melanoma. Here, a TLR7/8 agonist, 3M-011, was used effectively as a single systemic agent against disseminated mouse B16-F10 melanoma. The investigation of the mechanism of antitumor action revealed that the agonist had no direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells tested in vitro. In addition, 3M-011 retained its effectiveness in scid/B6 mice and scid/NOD mice, eliminating the requirement for T and B cells, but lost its activity in beige (bg/bg) and NK1.1-immunodepleted mice, suggesting a critical role for natural killer (NK) cells in the antitumor response. NK cytotoxicity was enhanced in vivo by the TLR7/8 agonist; this activation was long lasting, as determined by sustained expression of the activation marker CD69. Also, in human in vitro studies, 3M-011 potentiated NK cytotoxicity. TLR7/8-mediated NK-dependent antitumor activity was retained in IFN-α/β receptor-deficient as well as perforin-deficient mice, while depletion of IFN-γ significantly decreased the ability of 3M-011 to delay tumor growth. Thus, IFN-γ-dependent functions of NK cell populations appear essential for cancer immunotherapy with TLR7/8 agonists.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-008-0581-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Toll-like receptors, Natural killer cells, Tumor immunity

Introduction

Melanoma is one of the cancers that afflict a relatively young population and that has a tendency to progress rapidly to metastatic disease [5]. At this advanced stage, the prognosis is dismal, as the disease responds poorly to any of the currently approved therapies. Consequently, metastatic melanoma traditionally has been a disease in which many novel systemic treatment options have been proposed and tested [5].

Although rare, there are well-documented instances for spontaneous regression of malignant tumors, including melanoma [30]. In some cases, the mechanism for this regression seems to be immune mediated, suggesting a rationale for using immunotherapy to treat melanoma. Some immune-based therapies are already approved for the treatment of melanoma (IFN-α, Interleukin-2), while others (other recombinant cytokines, adoptive cellular immunotherapy, vaccines) have had limited benefit in the clinic to date [5]. Occasional reports of durable, complete responses [5] bolster the expectation that new and improved immune-based therapies could result in better outcomes.

One such therapeutic approach is based on the control and modulation of the innate immune system. The activation of innate immunity relies on its ability to identify the pathogen as foreign [26] and is based upon the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (or PAMPs) by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). Toll-like receptors (TLRs)—mammalian homologs of Drosphila Toll receptor—and NOD-like receptors are major classes of PRRs that act as sensors for various microbial components, which are highly conserved among broad numbers of pathogens including lipopolysaccharides, lipopeptides, muropeptides, single-stranded RNA and DNA (CpG), and flagellin [27, 34]. To date, more than 10 proteins have been characterized as belonging to the TLR family [14], and they are preferentially, although not exclusively, expressed on cells of the innate immune system (dendritic cells, macrophages, monocytes). Activation of TLRs leads to the general activation of innate immune cells and results in a cascade of effector functions such as secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, upregulation of costimulatory molecules, increased antigen processing and overall activation and migration of antigen-presenting cells such as dendritic cells. This activation eventually results in the induction of specific adaptive immunity and skewing toward a Th1- or Th2-type response [2, 39].

Cancer cells generally lack such foreign (nonself) molecular patterns and escape and even suppress [29, 48] immune recognition, and are thus unable to stimulate an immune response. However, synthetic TLR agonists that emulate the activity of natural TLR ligands [15, 23, 24, 34] may be used to therapeutically modulate and consequently stimulate an immune response to cancer [24]. For example, imidazoquinoline compounds (also called IRMs or immune response modifiers) like imiquimod and resiquimod activate TLR7 and/or TLR8 receptors on diverse immune cells (including dendritic cells) and offer an attractive approach for immune therapy in cancer. Indeed, many investigators have shown that the TLR7 agonist, imiquimod, is an effective anticancer agent [40, 50]. However, imiquimod is approved for local administration only, as a topical 5% cream formulation (Aldara™) for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma and for the treatment of actinic keratosis, a precursor of squamous cell carcinoma. As the most severe cases of melanomas tend to have multiple nodal and visceral metastases in addition to the primary skin lesion or after the removal of the primary tumor site, it is likely that their treatments would benefit more from a delocalized, systemic approach. Having this disease as a potential target disease, the compound 3M-011 was selected from the imidazoquinoline library of 3M compounds as a dual TLR7 and TLR8 agonist that would allow systemic administration. In this article, we report for the first time the observations on the antitumor activity of the systemically administered 3M-011 in a mouse B16-F10 melanoma lung colonization model [3].

Materials and methods

Tumor cells

B16-F10 (#CRL-6475) murine melanoma cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). B16-F10 cells stably transfected with a luciferase reporter vector were obtained from Xenogen Corporation. For in vivo experiments, 5 × 105 cells were inoculated intravenously in mice at the beginning (day 0) of the antitumor efficacy experiments.

For cell viability assays, 105 cells were distributed in each of the wells of a 96-well plate and treated with different concentrations of acetate-buffered saline-formulated compound. The plate was incubated for 24 h and then the number of surviving cells was estimated either by counting the cell surface density in an ArrayScan II instrument (Cellomics) or by using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega), which quantifies the amount of ATP in viable cells.

NK cytotoxicity assays

In vitro, natural cytotoxicity was assayed by measuring the ability of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to lyse 51Chromium-labeled-K562 target cells and by expressing the results as percent lysis [19]. In mice, natural cytotoxicity was assessed in vivo by comparing the survival of CFSEdim wild-type and CFSEbright TAP1-deficient (Tap1tm1Arp) splenocytes transferred into recipient animals [19].

NF-κB activation in TLR-transfected cells

HEK293 cells stably transfected with an NF-κB–luciferase reporter were transiently transfected with a mammalian expression vector encoding human or mouse TLR7 or TLR8. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, the cells were stimulated for another 24 h with different concentrations of 3M-011 formulated in 0.5% DMSO. The cells were lysed and analyzed by measuring luminescence intensity; the results were expressed as fold increase over vehicle control.

Reagents and antibodies

3M-011 is an imidazoquinoline chemically related to imiquimod and resiquimod [17]. The compound was synthesized by the 3M Pharmaceutical’s Chemistry Department (St Paul, MN, USA). For the in vitro luciferase reporter assays, 3M-011 was dissolved in DMSO. For all the other in vitro and in vivo experiments, 3M-011 was formulated in acetate-buffered saline at pH 7.4. CpG1826 (TTCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT) was synthesized at MWG Biotech (Highpoint, NC, USA). Cisplatin was obtained from FloridaInfusion/NationsDrug, Palm Harbor, FL, USA.

Fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies including anti-CD49b (DX5) APC and NK-1.1 (PC136) FITC were purchased from PharMingen/Becton Dickinson (San Jose, CA, USA). Anti-NK1.1 (PK136, #16-5941) and anti-IFN-γ (R4-682, #16-7312) monoclonal antibodies and their matched isotype controls were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). For immunodepletions, PK136 was administered at 100 μg per mouse every 4 days and R4-682 was given at 200 μg per mouse every 3 days.

Mice

Female B6 (C57BL/6J), albino B6 (C57BL/6J-Tyr), scid/NOD (NOD.CB17-Pkrdc scid/J), beige/B6 (C57BL6/6J-Lyst bg-J/J), and perforin-deficient (C57BL/6-Prf1 tm1Sdz/J) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). IFN-α/β receptor-deficient mice, bred on site at 3M Pharmaceuticals, were a gift from Dr. Philippa Marrack (National Jewish Medical and Research Center, Denver, CO, USA). Eight- to twelve-week-old mice were used in these studies. The 3M Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocol that details the use of these animals.

Treatment of mice and measurement of tumor load

For most antitumor experiments, mice were assigned randomly to different treatment groups and injected with 3M-011 or vehicle using an every other day administration schedule for a total of 11 days (or six doses). Before administering 3M-011, the tumor was allowed to establish for one doubling time, which is approximately 24 h for B16-F10 tumor cells. This establishment period ensured that no treatment would affect tumor take, a period of time when the transplanted tumor cells are most vulnerable [13]. Moreover, the tumor load used (5 × 105 cells/mouse) was selected in pilot experiments so as to ensure that tumors would not regress while being treated or following treatment. For the NK1.1 depletion experiment, the 10 mg/kg of 3M-011 or vehicle were given at 48 h after tumor inoculation, to allow for the NK1.1-depleting antibody, administered at 24 h after tumor injection, to become effective.

When used to evaluate the effects of different administration schedules, different dose levels of 3M-011 were given daily, every other day, every 4 days, or every 7 days. For this experiment, the total number of doses was as follows: fifteen doses for mice treated every day; eight doses for mice treated every other day; five doses for mice treated every 4 days; three doses for mice treated every 7 days. The negative control for this study consisted of mice treated with vehicle every day for 15 days. At the start of all the antitumor experiments, 10 mice were assigned to each treatment group.

For experiments where lung mass (in milligrams) was used to evaluate tumor load, mice were sacrificed at day 14 and their lungs were removed, separated from the heart, esophagus, mediastinal lymph nodes and weighed. In an alternate experiment, the lungs were placed under a dissecting scope adapted with a digital camera and their anterior and posterior surfaces were photographed. The digitized picture was opened in Adobe Photoshop as an RGB picture and the pixel intensity histogram was analyzed. Noticing that under the particular illumination conditions used, the contrast between dark and light pixels is maximal in the blue channel, the number of blue pixels with intensities between 0 and 100 was used as an estimate of dark, or black, tumor foci. The sum of dark pixel for the anterior and posterior lung was used as an estimate of tumor load for that particular lung.

For bioimaging, on the day of tumor measurement, the mice were given a 0.2 mL intraperitoneal injection of a 15 mg/mL luciferin solution. Ten minutes later, the mice were anesthetized using isoflurane, and tumor measurements were performed. A Xenogen IVIS 100 System was used to acquire images of the tumor and to measure the tumor load over the thorax in units of surface radiance (photons/second/centimeter2/steradian). The mice were analyzed and compared as groups, and the median for each group at a given observation day was used as an estimate of tumor load for the group. The tumor load, recorded as a function of time, defines growth curves for each group. The degree of separation between the growth curves was estimated by the delay in reaching similar tumor burdens and was used to compare the antitumor activity among the treatment groups.

Because of the variability of the bioimaging data, the statistical procedure chosen to ensure reproducible interpretation of tumor growth delays took advantage of the repeated measurements over time from one single tumor. The selected nonparametric procedure is described in [32] and relies on the ranking of tumor burdens at all measurement times for all the mice in the treatment and control groups. For the actual analysis, a web-based application (http://www.stat.ucl.ac.be/ISpersonnel/lecoutre/Tgca/english/index3.html) was used. For the experiments described in this paper, all differences described as significantly different were statistically significant at the P = 0.05 level.

Measurement of cytokines and 3M-011 in the serum

Mice were injected subcutaneously with different doses of 3M-011 or vehicle. Mouse serum TNF-α levels at 1 h were quantified by ELISA, using reagent kits in accordance with the manufacturer’s procedure (BioSource International, Camarillo, CA, USA). The lowest limit of detection was 20 pg/mL. Mouse serum type I IFN (IFN-α and IFN-β) concentrations were estimated by a cytopathic effect reduction assay using murine encephalomyocarditis virus and L-929 murine fibroblasts (ATCC). Results were normalized to a reference standard of murine IFN-α (PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The minimum level of detection was 1 U/mL.

Analysis of the mouse serum samples for concentrations of 3M-011 following a single subcutaneous dose was done by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

Results

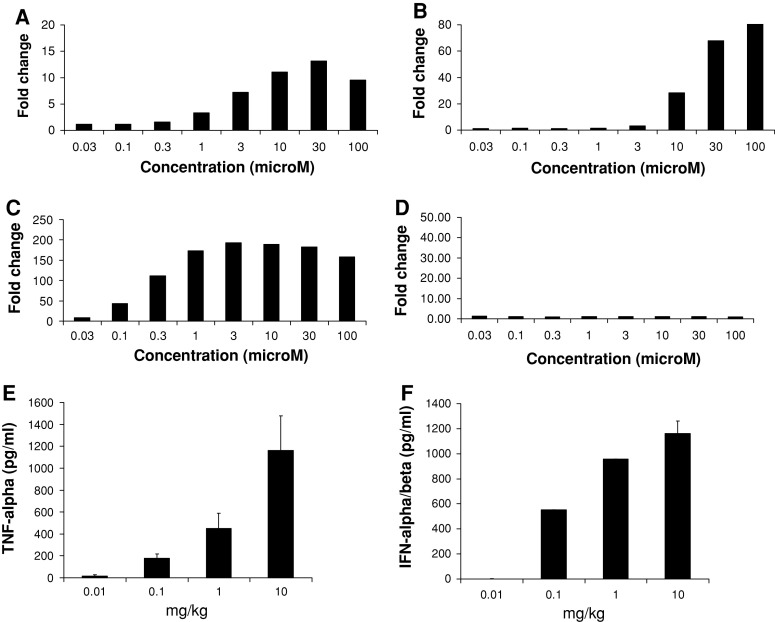

The TLR selectivity of 3M-011 in mouse and human was established using an NF-κB luciferase reporter assay. The NF-κB reporter was stably integrated into HEK-293 cells that were subsequently transiently transfected with human or mouse TLR7 or TLR8 (Fig. 1). With all the TLRs tested, except mouse TLR8, stimulation with 3M-011 resulted in a dose-dependent induction of NF-κB-controlled luciferase activity. Thus, similar to previous reports with other TLR7/8 imidazoquinolines [22, 24], 3M-011 in humans activates both TLR7 and TLR8 (Fig. 1a, b), whereas in mice, 3M-011 activates only TLR7 and not TLR8 (Fig. 1c, d).

Fig. 1.

3M-011 action is mouse TLR7 dependent and it results in increased serum TNF-α and IFN-α/β titers. (a–d) NF-κB activation by 3M-011 in the presence of human or mouse TLR7 or 8. HEK293 cells stably transfected with an NF-κB-luciferase reporter construct were transiently transfected with a mammalian expression vector encoding human TLR7 (a), human TLR8 (b), mouse TLR7 (c), or mouse TLR8 (d). The cells were stimulated for 24 h with various concentrations of 3M-011 or vehicle control. They were then lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. The data are represented as fold increase of luciferase activity over the vehicle control. (e, f) Cytokine induction by 3M-011. Groups of three mice were inoculated with 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 mg/kg of 3M-011 (the amounts are indicated on the horizontal axis). Sera were collected at 1 h for evaluation of the TNF-α concentrations (e) and at 2 h for the evaluation of the amounts of IFN-α/β (f)

To select an effective dose that could be used in the antitumor studies, wild-type C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with different doses of 3M-011, and serum TNF-α and IFN-α/β, cytokines induced by TLR7 and/or 8 agonists [24, 37], were evaluated. As depicted in Fig. 1e, f, 3M-011 induced a dose-dependent increase in serum concentrations of both TNF-α and IFN-α/β.

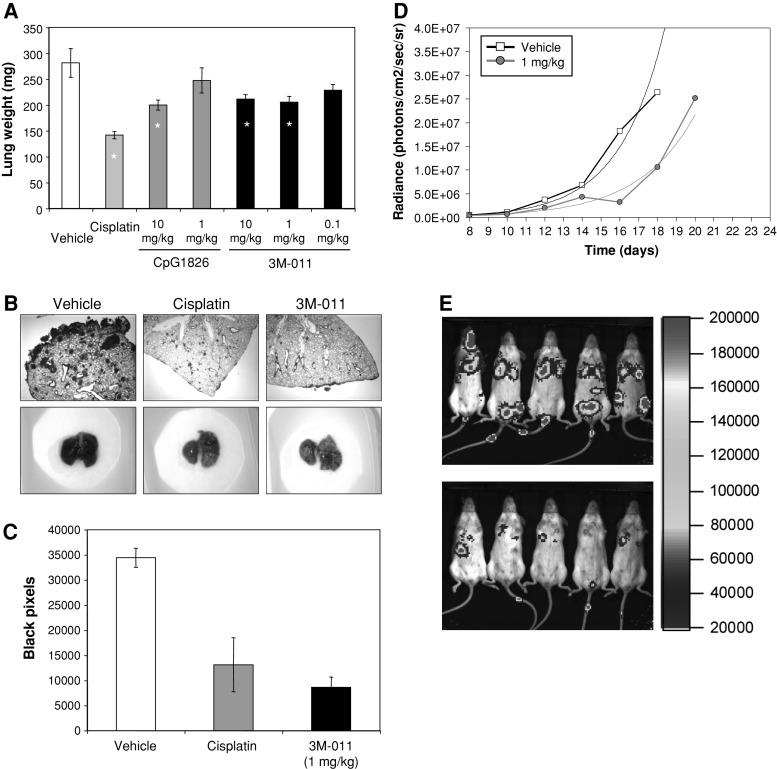

Using the same doses, 3M-011 was tested for its antitumor activity. To this end, B16-F10 cells were inoculated IV and 14 days later the lungs were evaluated by weighing for their tumor burden. In this experiment (Fig. 2a), 3M-011 at different dose levels (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg) was compared to cisplatin (10 mg/kg) and CpG1826 (10 and 1 mg/kg). All compounds were administered six times, every other day. Doses of 1 and 10 mg/kg were biologically active when measured in this system. Moreover, histological analyses (Fig. 2b, top row) as well as simple photographs (Fig. 2b, bottom row) reconfirmed that 3M-011 at a dose of 1 mg/kg has antitumor effects. In fact, the number of black pixels (as a measure of the melanin load in the lungs) in the photographs of the 10 mice in each of the vehicle, cisplatin or 3M-011-treated groups were quantified (Fig. 1c). For the subsequent studies, 1 mg/kg 3M-011 was selected as a biologically active dose and the antitumor potential was tested in a model of bioluminescent B16-F10 disseminated melanoma (Fig. 2d). Groups of 10 mice were inoculated with B16-F10 cells in the tail vein and treated every other day with six doses of 1 mg/kg 3M-011 or vehicle. Tumor burden over the thoracic region was determined as described in “Materials and methods,” with results being presented as medians for the groups. An exponential trendline fitted to the medians was added to facilitate visual comparisons of tumor growth delays. Using the nonparametric statistical test for the differences between the growth curves ([32]), results presented in Fig. 2d show significantly lower tumor burdens in the group of mice treated with 3M-011 when compared to the group treated with vehicle. Figure 2e is a photograph of the tumor distribution as captured by the camera of the Xenogen instrument on day 16 and demonstrates a marked reduction in tumor load in 3M-011-injected mice compared to vehicle-treated mice. More data on the antitumor effects of 3M-011 are included in the Supplemental figures: comparisons to CpG1826 and other imidazoquinolines (like 852) are included in Supplemental Figure 1; antitumor effects of 3M-011 in other tumor models are included in Supplemental Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

3M-011 has antitumor effect in the mouse. (a) Disseminated tumor burden as quantified by lung weight. B16-F10 cells (5 × 105) were inoculated IV, and 1 day later, groups of 10 mice were treated with vehicle, cisplatin (10 mg/kg), CpG1826, and 3 M-011 at the dose levels indicated for six every other day administrations. At day 14, mice were sacrificed and their lungs were weighed. Groups indicated by * are, by t test, significantly different from vehicle. (b) Histology and appearance of lung tumor burden. In a separate experiment, designed identically to the one at point (a), the lungs collected at day 14 were photographed, fixed in buffered formalin, and subsequently stained by H&E. (c) The photographs from the experiment at point (b) were quantified in Adobe Photoshop for the number of black pixels. (d) Quantification by bioimaging of the antitumor effect of 3M-011. Groups of 10 mice were inoculated in the tail vein with 5 × 105 B16-F10–luciferase cells and were treated with six doses every other day of vehicle or 3M-011 at 1 mg/kg. The median tumor measurements over the thorax for each group are plotted as a function of the measurement day. Exponential trend lines are indicated by dotted lines. (e) Visualization of the antitumor effect of 3M-011. The image of light-emitting tumor cells as it was recorded by the camera of the Xenogen apparatus on day 16 of the experiment in (d) for the vehicle control and 3M-011. Only five representative mice of each group of 10 are shown

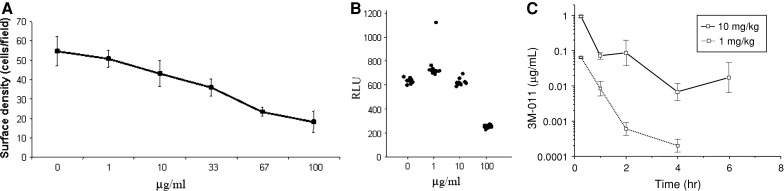

To determine whether the observed antitumor effects could be due to direct activity of the compound on the tumor cells themselves, increasing concentrations of 3M-011 were added to the B16-F10 cells in culture and evaluated 24 h later. A decrease in cell number as a function of dose was quantified by measuring the average cell surface density (Fig. 3a) or by evaluating the amount of intracellular ATP (used as an indicator of cell viability) (Fig. 3b). In either case, only concentrations larger than or equal to 33 μg/mL were noticed to consistently result in measurements below those recorded in the vehicle-treated wells. As a correlation with the concentration of 3M-011 achievable in vivo would help in the interpretation of this observation, a pharmacokinetic experiment was carried out. To this end, 3M-011 was administered at 1 and 10 mg/kg intravenously (to maximize bioavailability) to wild-type C57BL/6 mice, and serum drug concentrations were determined at different times after injection. The data obtained are represented in Fig. 3c. The peak drug concentrations recorded at 15 min following administration of the 1 and the 10 mg/kg doses were 0.08 and 1 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 3c). As systemic 3M-011 concentrations were at least 10-fold below the concentration required to induce toxicity in cultured B16-F10 cells, it was concluded that the direct cytotoxic effect of the drug on the B16-F10 cells (Fig. 3a, b) cannot explain the observed in vivo antitumor effects of the compound.

Fig. 3.

3M-011 can decrease B16-F10 melanoma cell counts only at concentrations unattainable in vivo. B16-F10 cells were distributed at a concentration of 105 per well in a 96-well plate, and 3M-011 was added at the final concentrations indicated. The testing of the vehicle is indicated by a concentration of 0 (zero) μg/mL. Twenty four hours later, one experiment (a) was concluded by automatically measuring the surface density of the cells, and the measurement is depicted as mean ± standard error of quadruplicate wells. In another experiment (b), the cells were lysed and their viability was evaluated by measuring the amount of ATP. Cell viability of 12 replicate wells is illustrated by plotting individual values measured for each dose of 3M-011. (c) Extrapolated C max was no more than 1 μg/mL. Two different doses (10 and 1 mg/kg) of 3M-011 were injected intravenously, and the amount of drug in the blood stream was detected by HPLC at different time points. Using a single compartment model, the C max for 10 mg/kg was estimated to be 0.95 μg/mL and for 1 mg/kg to be 0.065 μg/mL in the serum. The half life was 1–2 h

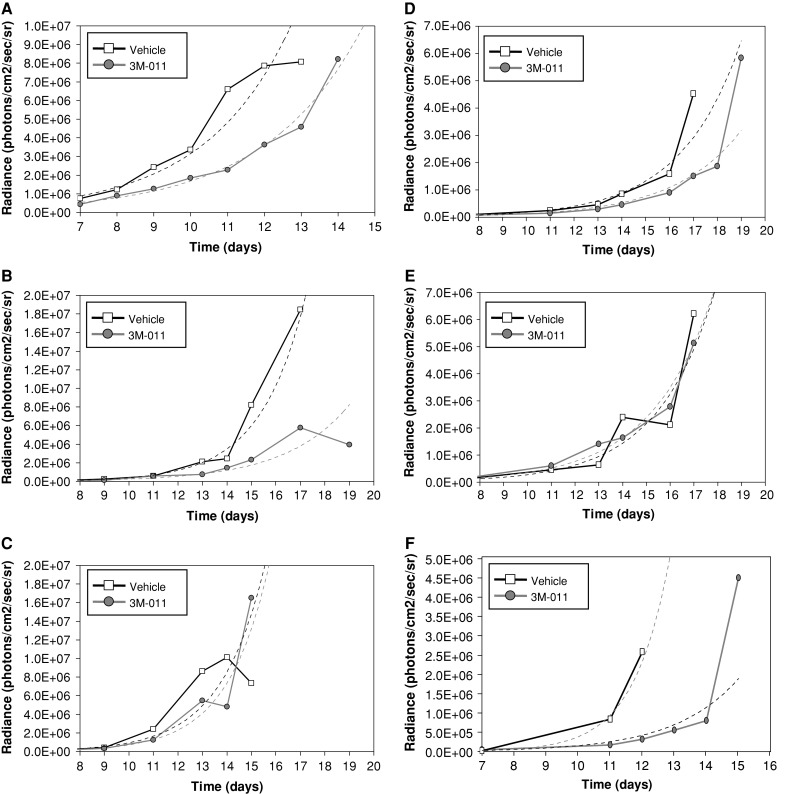

To determine whether immune mechanisms play a role in the antitumor effects of 3M-011, mouse strains with different immunodeficiencies were inoculated with tumor cells and antitumor responses were measured (Fig. 4). 3M-011 was administered at 1 mg/kg for six doses to tumor-bearing nu/nu mice (unpublished data), scid/BL.6 mice (Supplemental Figure 3) or scid/NOD mice (Fig. 4a). Since a delay in tumor growth was recorded as significant in the 3M-011-treated group of each strain, compared to the vehicle-treated group, it was concluded that the cells of the adaptive immune responses [7] do not contribute to the antitumor action of 3M-011. However, when the antitumor effect of 3M-011 was investigated in beige/B6 mice, which have decreased endogenous cytotoxic activity [47], it was found that 3M-011 had largely lost its ability to delay tumor-growth: there was only a small separation between the tumor growth curves of vehicle and 3M-011-treated groups in the beige mice (Fig. 4c) when compared to the sizable, significant separation between the vehicle and 3M-011-treament curves in C57BL/6 wild-type mice observed in the same experimental run (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

The influence of various immunodeficiencies on the antitumor effects of 3M-011. (a) 3M-011 antitumor effects in scid/NOD mice. The scid/NOD mice were inoculated with B16-F10 cells and groups of 10 mice were either treated with 1 mg/kg 3M-011 or vehicle control for six doses given every other day starting 1 day after tumor was inoculated. (b, c) 3M-011 effects on tumor growth in beige/B6 mice. Beige/B6 mice (c) and wild-type, background-matched controls (b) were inoculated with B16-F10 cells IV and treated for six doses, administered every other day, with vehicle or 3M-011 at 1 mg/kg. (d, e) The impact of depletion of NK1.1+ cells on the antitumor effect of 3M-011. After inoculation of 5 × 105 B16-F10 tumor cells on day 0, groups of C57BL/6 mice were subjected to depletion with NK1.1 antibodies or isotype control starting on day 1. After another 24 h, on day 2, treatment was initiated with 3M-011 at 10 mg/kg or vehicle, for six every other day administrations. (d) shows the isotype-depleted mice and (e) depicts the antitumor activity observed in the NK1.1-depleted mice. (f) The effects of IFN type I receptor deficiency on the antitumor activity of 3M-011. Mice deficient in IFN-α/β receptors were inoculated with tumor cells and treated with vehicle or 3M-011 for six every other day at 1 mg/kg doses

As one of the major defects in beige/B6 mice is a defect in NK cell activity, the involvement of this cell type in the antitumor response of 3M-011 was tested directly by depleting the NK cells. Preliminary tests indicated that immunodepletion with anti-NK1.1 antibody prior to tumor inoculation resulted in a better tumor take and shortened the time to terminal tumor loads (unpublished data). Consequently, for the antitumor efficacy experiment, the immunodepletion was started after the tumor take period (for B16-F10, this is 1 day after tumor inoculation). This way it was ensured that 3M-011, with or without immunodepletion, was tested against similar tumor loads. To allow time for the NK depletion to establish its effect, administration of 3M-011 at 10 mg/kg was started 48 h after tumor inoculation. Moreover, the anti-NK1.1 antibody was given every 4 days to maintain the immunodepletion. A parallel experiment (unpublished data) verified that the reduction in NK cells (defined as CD69+ NK1.1+ double positive splenocytes) lasted for at least 4 days following the administration of PK136 antibody. In the antitumor experiment, 3M-011 had the potential to significantly delay B16-F10 tumor growth when mice were administered the isotype control (Fig. 4d), but this delaying effect was lost when anti-NK1.1 antibody was used (Fig. 4e). In essence, the antitumor effect of 3M-011 was eliminated in NK1.1-depleted mice (Fig. 4e) when compared to mice injected with the isotype control (Fig. 4d).

Since enhancement of NK activity by TLR7/8 agonists is known to be mediated in part by IFN-α/β [19], the next set of experiments was performed in IFN-α/β receptor-deficient [25] mice to determine the role of type I IFN in 3M-011-induced antitumor responses. Results from this study (Fig. 4f) indicate that despite the absence of functional receptors for IFN-α/β, 3M-011 was still able to significantly delay the growth of the B16-F10 tumor nodules in the lung, suggesting that this cytokine is not critical for its function.

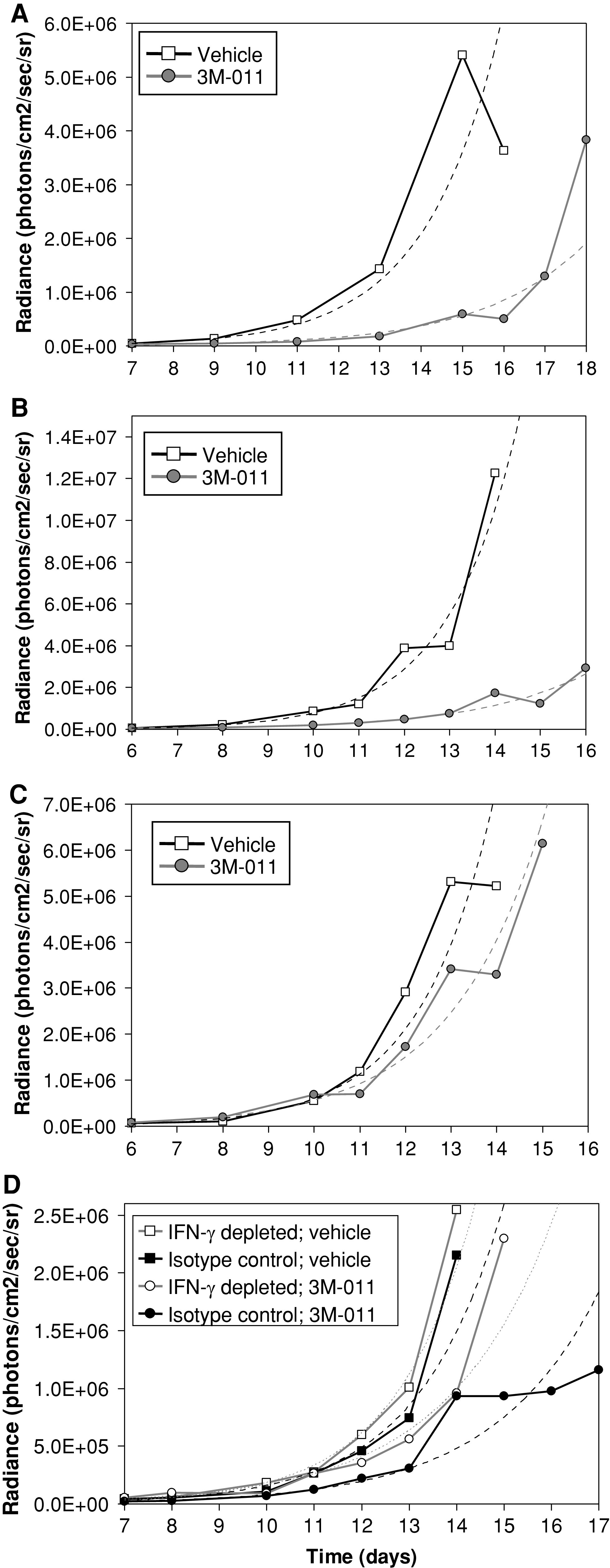

The next set of experiments set out to evaluate NK effector mechanisms critical for 3M-011 antitumor activity. As one of the major mechanisms of cell cytolysis described for NK cells involves perforin [46], the importance of this effector molecule in 3M-011-mediated antitumor activity was evaluated using mice defective in perforin synthesis [8]. Interestingly, 3M-011 maintained its ability to significantly delay tumor growth in the perforin-deficient mice (Fig. 5a). To exclude the possibility of a compensatory mechanism that does not involve NK cells, perforin-deficient mice were subjected to NK cell immunodepletion. As indicated by the results in Fig. 5b, c, while maintaining its antitumor activity in isotype-depleted perforin-deficient mice (Fig. 5b), 3M-011 lost most of its antitumor efficacy in NK1.1-depleted perforin-deficient mice, confirming that in the perforin-deficient mice the antitumor effect of 3M-011 was still dependent on NK1.1+ cells.

Fig. 5.

The influence of perforin and IFN-γ deficiencies on the antitumor effects of 3 M-011. (a) The influence of perforin deficiency on the antitumor effects of 3M-011. Mice deficient in perforin were inoculated with 5 × 105 B16-F10 tumor cells and treated with vehicle or 3 M-011 at 1 mg/kg doses for six every other day. (b, c) Depletion of NK1.1 cells in perforin-deficient mice. Perforin-deficient mice were inoculated with tumor cells at day 0 and then were subjected to depletion with isotype control or anti-NK1.1 antibodies starting on day 1. After another 24 h, on day 2, the treatment was initiated with 3M-011 at 10 mg/kg or vehicle, for six every other day administrations. (b) shows the isotype-depleted mice and (c) shows the NK1.1-depleted mice. (d) The influence IFN-γ depletion on the antitumor effect of 3M-011. After inoculation of 5 × 105 B16-F10 tumor cells on day 0, groups of C57BL/6 mice were subjected to depletion with anti-IFN-γ or isotype control starting on day 1 and administered every 3 days. After another 24 h, on day 2, treatment was initiated with 3M-011 at 10 mg/kg or vehicle, for six every other day administrations

In addition to perforin, NK cells are also a major source of IFN-γ [46]. To investigate the importance of this NK effector mechanism in the antitumor activity of 3M-011, IFN-γ was immunodepleted using R4-682 antibody. C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with B16-F10 tumor cells and 1 day later the administration of the anti-IFN-γ-depleting antibody or its isotype control was initiated. Antibody injections were repeated every 3 days until the end of the experiment. On day 2, 3M-011 was administered at 10 mg/kg, every other day. The results from this study are represented in Fig. 5d. While 3M-011 had a strong antitumor effect in isotype-depleted mice, a substantial loss in this effect was observed when IFN-γ was depleted, thus supporting a critical role for IFN-γ in 3M-011-induced NK activity.

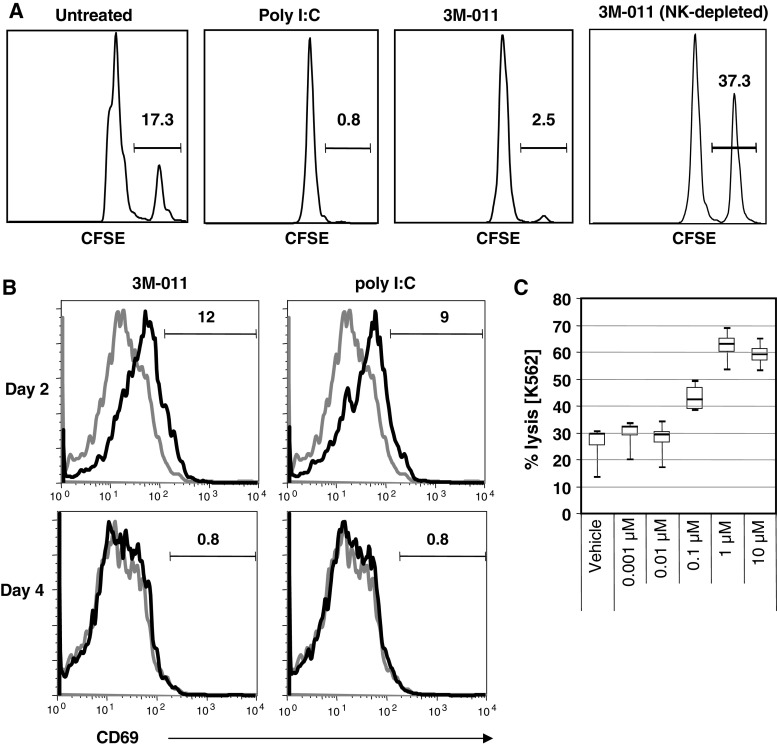

All the data presented above indicate NK cells to play an important role in the antitumor effect generated with 3M-011. To ascertain that 3M-011 treatment can activate NK cells, the in vivo effect of 3M-011 on NK cell activation was assayed by cytotoxicity against known NK target cells. In this experiment, wild-type mice received an adoptive transfer of CSFEbright-labeled, NK-cell-sensitive targets, followed by subcutaneous administration of 3M-011 at 1 mg/kg or 1 mg/kg polyinosinic-cytidylic acid (poly I:C), as a positive control for NK activation (Fig. 6a). Results demonstrate that 3M-011 was as effective as poly I:C in eliminating MHC class I-deficient target cells. To determine how long these NK cells remained activated in vivo, their activation was monitored over time by evaluating the expression of CD69 on splenic and lymph node NK-cells at various times after administration of 3M-011 (Fig. 6b). Elevated levels of CD69 were observed on both splenic (Fig. 6b) and lymph node (unpublished data) NK-cells 2 days after treatment with 3M-011 or poly I:C. By day 4, however, CD69 expression returned to baseline levels. Finally, because of the well-documented differences between mouse and man [22, 24] with regard to TLR expression and activity, the ability of 3M-011 to activate human NK cells was tested. 3M-011 added at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 10 μM to human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures [18] induced cytotoxicity against the NK cell-sensitive target cells, K562, at doses greater than 0.1 μM (Fig. 6c). These data indicate that 3M-011 was not only able to activate NK cells in vivo in the mouse, but this mechanism is also likely to translate to human NK cells as well.

Fig. 6.

3M-011 activates mouse NK cells in vivo and human NK cells ex vivo. (a, b) 3M-011 effects on natural cytotoxicity in the mouse. In (a), CSFEbright-labeled, TAP1-deficient, NK-sensitive cells and CFSEdim-labeled wild-type cells were transferred together and in equal amounts into C57BL6 mice. A group of these mice was subjected to immunodepletion with anti-NK1.1 antibodies. Subsequently, the mice were injected subcutaneously with vehicle, with 1 mg/kg 3M-011 or with 1 mg/kg polyinosinic-cytidylic acid (poly I:C). Relative to the amount of the wild-type cells detected, the percentage of NK-sensitive cells remaining after treatment is specified above the bars. (b) Groups of mice were injected subcutaneously with 3M-011 or poly I:C, and the expression of the activation marker CD69 in splenic NK-cells was assayed 2 or 4 days later. The proportion of CD69 positive cells is indicated. (c) 3M-011 effects on natural cytotoxicity in human cells. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cell cultures were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of 3M-011 and tested for the ability to kill the NK-sensitive target K562

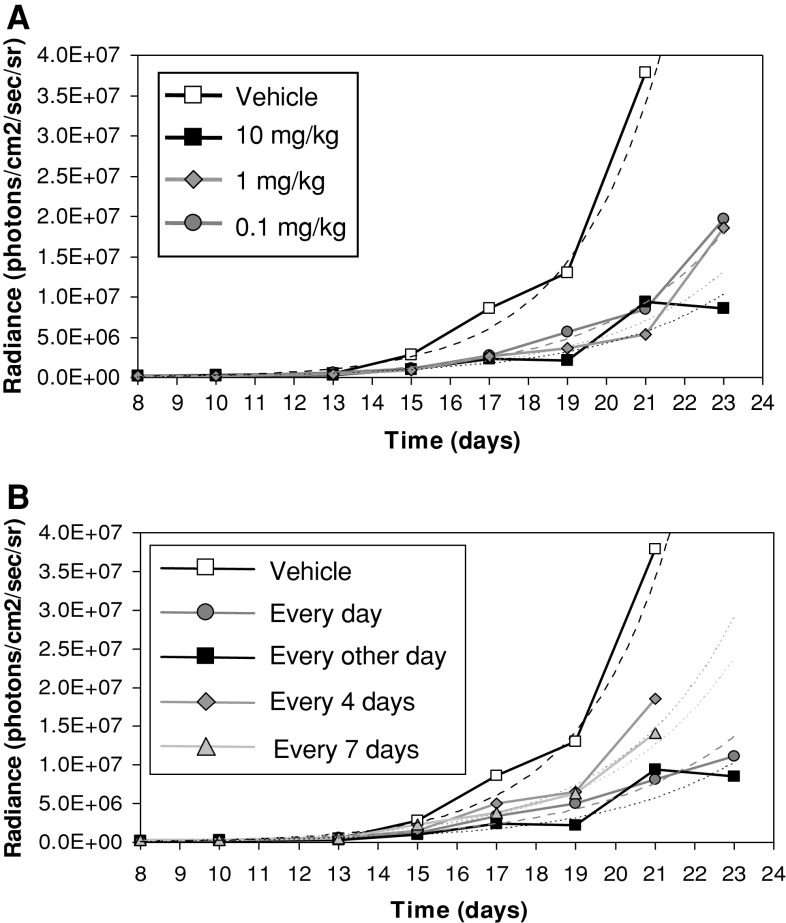

If sustained NK cell activation by 3M-011 is important in the antitumor response of 3M-011, it was plausible that increasing the interval between administration of 3M-011 doses by 2–3 days may still result in measurable antitumor response. To test this hypothesis, different dosage regimens were tested for their influence on the antitumor response of 3M-011. Groups of mice were treated with 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg doses administered daily, every other day, every 4 days or every 7 days. First it was observed that, irrespective of the schedule, there were no major differences between the dose levels tested, as the antitumor effects of doses of 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg of 3M-011 administered every other day delayed tumor growth to a similar extent (Fig. 7a). Figure 7b illustrates the outcome of using a dose of 10 mg/kg administered daily, every other day, every fourth day, or every week. In this experiment, all the regimens tested had the ability to delay tumor growth, although the every 4-day and weekly schedules were less efficient, which is evocative of the time course of NK-cell activation induced by 3M-011.

Fig. 7.

Investigation of dose and schedule dependency on the antitumor effects of 3M-011. (a) 3M-011 dose-effect. Groups of 10 mice were inoculated with tumor cells and treated with different doses of 3M-011 (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg) or vehicle administered every other day for eight doses. (b) 3M-011 administered under different dosage schedules. 3M-011 (10 mg/kg) was administered with different frequencies over a similar time interval: daily, every other day, or weekly, lasting for 15 days, and every fourth day, for a duration of 16 days

Discussion

Various published studies on the antitumor mechanism of different TLR ligands explored the role of these agonists in cell-based vaccine therapy or as adjuvants, thus focusing on the modulation of adaptive immune responses to exogenously administered antigens [1, 34, 42]. Other lines of investigation, however, report on the use of TLR agonists as single agents for cancer treatment [4, 20, 49, 53]. Most of these studies support an important role for innate immune cells, including macrophages [4], NKT, or NK cells [20, 28] for the antitumor effects mediated by TLR agonists.

Here, the antitumor potential of the small molecule TLR7/8 agonist, 3M-011, was evaluated in the B16-F10 murine melanoma model, an aggressive, rapidly growing tumor [3]. The first step in the investigation was to exclude that 3M-011 had any direct antitumor effects other than those mediated via TLR7/8 engagement on immune effector cells.

Although 3M-011 would be expected to be capable of stimulating adaptive immunity [40], the evidence presented in the current study suggests that the antitumor activity of 3M-011 was mediated by the innate immune system for the model investigated in this article. This conclusion is primarily based on the observation that the antitumor activity of 3M-011 was maintained in scid/B6 (Supplemental Figure 3) and scid/NOD mice (Fig. 4) and lost its effect in beige mice. The scid mutation results in the loss of adaptive immunity [7]. Additionally, the scid/NOD strain has an NK cell deficit, but this can be improved by treatment with TLR agonists [36]. The beige mice have defective granulocyte and granular lymphocyte compartments, including NK cells. The loss of activity resulting from impaired natural killer (NK) cell activity was confirmed by immunodepletion of cells positive for NK1.1. Because NK1.1 marker is present on NK and NKT cells, it is possible that any or both of these cell types may be involved in the antitumor effect of 3M-011. However, as 3M-011 maintained its activity in scid mice, which would be missing NKT cells, it is more likely that 3M-011 relies on NK cells for its antitumor effect.

Cytokines like IFN-α/β, IL-15, IL-12, and IL-18 are important for the activation and subsequent survival of NK cells [46]. Immune response modifiers, including 3M-011, are potent inducers of IFN-α/β [40], and therefore, it is plausible to expect that type I interferon is at least in part mediating the antitumor effects of 3M-011. However, when the antitumor response was evaluated in IFN-α/β receptor KO mice [25], 3M-011 was still effective in inducing its antitumor effects. This observation was somewhat surprising, because previous studies demonstrated an important role for IFN-α in imiquimod’s antitumor activity [50].

There are at least two possibilities to explain these findings. One explanation is that 3M-011 can induce IFN-α/β in IFN-α/β receptor-deficient mice (unpublished data and [25]), and this IFN-α/β is able to directly inhibit the growth of B16-F10 cells [6]. As NK1.1+ immunodepletion abolishes 3M-011 antitumor efficacy but most likely does not affect the titers or sensitivity to IFN-α/β, this explanation seems unlikely. An alternate explanation is that although IFN-α/β is important in NK proliferation and NK cytotoxicity, it may not be required for the antitumor effects seen with 3M-011 in the B16-F10 model. This hypothesis is supported by observations reported with murine CMV infection [41] that normally induces NK cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and IFN-γ production. However, the deficiency of IFN-α/β receptors decreased only the proliferation and cytotoxicity, while the IFN-γ secretion by NK cells remained intact. The IRM-induced NK-cytotoxicity is also affected in IFN-α/β receptor KO mice [19]. All these reported observations suggest that the cytotoxic activity of NK cells may not be essential, may not be solely responsible for the antitumor effects in the B16-F10 disseminated melanoma model, or may also indicate that classical NK cells may not be the primary cells involved in the tumor inhibitory activity of 3M-011.

The importance of one of the cytotoxic effector mechanisms of NK cells was tested in perforin-deficient mice [8]. In these mice, 3M-011 still delays tumor growth. Depletion of NK cells from perforin-deficient mice ablated the antitumor effect of 3M-011, again demonstrating the critical importance of the NK1.1+ cells for the TLR7/8 agonist-mediated antitumor activity in this model.

Since perforin did not appear to be the major mechanism for controlling tumor growth by 3M-011, another potential NK effector mechanism that was investigated was IFN-γ [46]. 3M-011 lost a significant portion of its tumor growth delaying effect in tumor-bearing mice immunodepleted with anti-IFN-γ antibody. It is possible that the antibody was not totally effective at neutralizing IFN-γ, which could explain some residual antitumor activity, or that IFN-γ is not the only contributor to the efficacy of 3M-011. In either case, the data indicate that IFN-γ plays a significant role in the antitumor effects observed with 3M-011.

The perforin-independence of different effector mechanisms against tumors has been previously observed [16, 21, 44] in various cancer models, including disseminated B16 melanoma treated by adoptively transferred cytotoxic T cells [44]. In addition to direct killing by perforin, other cytotoxic mechanisms used by NK cells, cytotoxic T cells, or NKT cells include induction of apoptosis in target cells via death receptor signaling (CD95 engagement by Fas ligand) and indirect killing by TNF-α and IFN-γ [35]. The predominant killing mechanism appears to depend on the model. For example, in one model [16], the mechanism of tumor control involved Fas ligand and lymphotoxin-α, while in others [21, 44], IFN-γ secreted by the effector cell was important in opposing tumor growth. While the present studies clearly indicate a role for NK1.1-bearing cells but not for T cells or NKT cells, the final effector mechanism may involve in addition to IFN-γ, death receptor signaling or secretion of other cytokines and involvement of other effector cells including those regulated by IFN-γ. Additional studies are needed to explore these possibilities.

It is important to note that the NK-activating abilities of 3M-011 are expected to be maintained in humans, as this TLR7/8 agonist was able to stimulate the expression of CD69 on human NK cells (unpublished data), to increase their IFN-γ production (unpublished data) and to enhance their cytolytic function in vitro (Fig. 6c). Human NK cells have recently been shown to be activated indirectly by TLR7 and TLR8 agonists [19].

As the activation of NK cells potentially lasts for days (Fig. 6 and [31, 45]), the effect of increasing the interval between doses was evaluated. The data indicated that the antitumor effect was diminished only when the compound was administered more than 3 days apart (Fig. 7). This is similar but not identical to the half-life of NK activation, which as measured by CD69 expression was estimated to be about 2 days (Fig. 6). However, it is possible that CD69 expression, a widely used marker of activation [38] but of uncertain function, may not appropriately specify the type of NK activity at work in our experimental system. Alternatively, tracking the NK activity in the spleen or the lymph nodes may not accurately describe the ability of 3M-011 to mobilize NK-cells into the tumor microenvironment. It may also be possible that the NK cell is only the beginning of a cascade of events that continues after IFN-γ is secreted, which may last for more than 2 days. If this is the case, then the final effector cell, the one directly responsible for eliminating tumor cells, may not be the NK cell but some other cell, such as macrophages, which are known to be activated by IFN-γ and to be involved in the TLR-mediated killing of tumor cells [33]. Finally, it may be possible that only subsets of NK cells are the primary NK1.1+ effector cells. One such subset is the so called “natural killer dendritic cell” (NKDC) [43] or interferon-producing killer dendritic cell (IKDC) subset [9, 52]. These cells secrete type I and type II interferon [9, 43, 52] and may be a major source of IFNγ [12, 52]. They also mediate tumor cell lysis in a TRAIL-dependent manner and were demonstrated to be significantly more effective in eliminating B16-F10 tumors than NK cells in an adoptive transfer model [52]. Presumably, in this context, perforin might be expected to be less critical. This potential antitumor effector may explain the efficacy of 3M-011 in mice lacking IFN-α/β receptors or perforin. It is interesting that IRMs have been previously demonstrated to induce the expression of TRAIL [10]. In addition, because IRMs have the ability to stimulate directly the dendritic cells [18, 22], in contrast to conventional NK cells [19], it is possible that 3M-011 can activate these killer dendritic cells directly and thus may not require IFN-α/β, just like other agents do [9, 11, 43].

It was observed that the effect of 3M-011 appears to plateau at high doses. This may depend on the endogenous “reserve” of potential NK activity, which probably cannot exceed a certain limit that is host dependent. As an extension of this scenario, it is possible that a TLR7/8 agonist might enhance the activity of transplanted NK or LAK cells in an adoptive immunotherapy setting or may enhance the antitumor effects of IL-2 or IFN-α therapies, given that the effects of these two cytokines may also involve the activation of NK1.1+ cells.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence for the ability of the immune system in cancer to select for a distinct defense mechanism from a wide range of TLR7/8-activated immune effectors. Thus, the TLR7/8 agonist 3M-011 has the ability to control tumor growth by modulating the activity of NK1.1+ cells. Perforin and IFN-α/β seem dispensable for this effect; however, IFN-γ production plays a central role.

The focus of this study was on a particular solid tumor, but it would be interesting to verify whether the same mechanism is selected in other settings. This is relevant, because imidazoquinolines have been shown to be effective in other types of cancer, for example in leukemias [51]. Finally, despite the fact that the precise and immediate mechanism of tumor cell killing still requires further investigation, the results of the present study further validate the effectiveness of TLR7/8 agonists in cancer immunotherapy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Footnotes

All authors are or were employed by 3M while this work was being conducted.

References

- 1.Akazawa T, Masuda H, Saeki Y, et al. Adjuvant-mediated tumor regression and tumor-specific cytotoxic response are impaired in MyD88-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:757–764. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez E. B16 murine melanoma. In: Teicher BA, editor. Tumor models in cancer research. Totowa: Humana Press; 2002. pp. 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auf G, Carpentier AF, Chen L, et al. Implication of macrophages in tumor rejection induced by CpG-oligodeoxynucleotides without antigen. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3540–3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch CM, Atkins MB, Sober AJ. Cutaneous melanoma. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 7. Philadelphia: Lippincot, Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1754–1809. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bart RS, Porzio NR, Kopf AW, et al. Inhibition of growth of B16 murine malignant melanoma by exogenous interferon. Cancer Res. 1980;40:614–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blunt T, Finnie NJ, Taccioli GE, et al. Defective DNA-dependent protein kinase activity is linked to V(D)J recombination and DNA repair defects associated with the murine scid mutation. Cell. 1995;80:813–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catalfamo M, Henkart PA. Perforin and the granule exocytosis cytotoxicity pathway. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:522–527. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(03)00114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan CW, Crafton E, Fan HN, et al. Interferon-producing killer dendritic cells provide a link between innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Med. 2006;12:207–213. doi: 10.1038/nm1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaperot L, Blum A, Manches O, et al. Virus or TLR agonists induce TRAIL-mediated cytotoxic activity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:248–255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaudhry UI, Katz SC, Kingham TP, et al. In vivo overexpression of Flt3 ligand expands and activates murine spleen natural killer dendritic cells. FASEB J. 2006;20:982–984. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5411fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhry UI, Kingham TP, Plitas G, et al. Combined stimulation with interleukin-18 and CpG induces murine natural killer dendritic cells to produce IFN-{gamma} and inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10497–10504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbett TH, Polin L, Roberts BL, et al. Transplantable syngeneic rodent tumors: solid tumors of mice. In: Teicher BA, et al., editors. Tumor models in cancer research. Totowa: Humana Press; 2002. pp. 41–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cristofaro P, Opal SM. Role of toll-like receptors in infection and immunity: clinical implications. Drugs. 2006;66:15–29. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, et al. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobrzanski MJ, Reome JB, Hollenbaugh JA, et al. Effector cell-derived lymphotoxin alpha and Fas ligand, but not perforin, promote Tc1 and Tc2 effector cell-mediated tumor therapy in established pulmonary metastases. Cancer Res. 2004;64:406–414. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson SJ, Lindh JM, Riter TR, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells produce cytokines and mature in response to the TLR7 agonists, imiquimod and resiquimod. Cell Immunol. 2002;218:74–86. doi: 10.1016/S0008-8749(02)00517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorden KB, Gorski KS, Gibson SJ, et al. Synthetic TLR agonists reveal functional differences between human TLR7 and TLR8. J Immunol. 2005;174:1259–1268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorski KS, Waller EL, Bjornton-Severson J, et al. Distinct indirect pathways govern human NK-cell activation by TLR-7 and TLR-8 agonists. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1115–1126. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hafner M, Zawatzky R, Hirtreiter C, et al. Antimetastatic effect of CpG DNA mediated by type I IFN. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5523–5528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayakawa Y, Takeda K, Yagita H, et al. Critical contribution of IFN-gamma and NK cells, but not perforin-mediated cytotoxicity, to anti-metastatic effect of alpha-galactosylceramide. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1720–1727. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1720::AID-IMMU1720>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemmi H, Akira S. TLR signalling and the function of dendritic cells. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;86:120–135. doi: 10.1159/000086657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang SY, Hertzog PJ, Holland KA, et al. A null mutation in the gene encoding a type I interferon receptor component eliminates antiproliferative and antiviral responses to interferons alpha and beta and alters macrophage responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11284–11288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptor function and signaling. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawarada Y, Ganss R, Garbi N, et al. NK- and CD8(+) T cell-mediated eradication of established tumors by peritumoral injection of CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2001;167:5247–5253. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K, et al. Tumor-driven evolution of immunosuppressive networks during malignant progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5527–5536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King M, Spooner D, Rowlands DC. Spontaneous regression of metastatic malignant melanoma of the parotid gland and neck lymph nodes: a case report and a review of the literature. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2001;13:466–469. doi: 10.1053/clon.2001.9315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koka R, Burkett PR, Chien M, et al. Interleukin (IL)-15R[alpha]-deficient natural killer cells survive in normal but not IL-15R[alpha]-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2003;197:977–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koziol JA, Maxwell DA, Fukushima M, et al. A distribution-free test for tumor-growth curve analyses with application to an animal tumor immunotherapy experiment. Biometrics. 1981;37:383–390. doi: 10.2307/2530427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krepler C, Wacheck V, Strommer S, et al. CpG oligonucleotides elicit antitumor responses in a human melanoma NOD/SCID xenotransplantation model. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:387–391. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2004.22202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krieg AM. Therapeutic potential of Toll-like receptor 9 activation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:471–484. doi: 10.1038/nrd2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lieberman J. The ABCs of granule-mediated cytotoxicity: new weapons in the arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nri1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin Y, Chen Y, Zeng Y, et al. Lymphocyte phenotyping and NK cell activity analysis in pregnant NOD/SCID mice. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;68:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu YJ. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:275–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marzio R, Mauel J, Betz-Corradin S. CD69 and regulation of the immune function. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 1999;21:565–582. doi: 10.3109/08923979909007126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:135–145. doi: 10.1038/35100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller RL, Gerster JF, Owens ML, et al. Imiquimod applied topically: a novel immune response modifier and new class of drug. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1999;21:1–14. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(98)00068-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen KB, Salazar-Mather TP, Dalod MY, et al. Coordinated and distinct roles for IFN-alpha beta, IL-12, and IL-15 regulation of NK cell responses to viral infection. J Immunol. 2002;169:4279–4287. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamoto M, Furuichi S, Nishioka Y, et al. Expression of toll-like receptor 4 on dendritic cells is significant for anticancer effect of dendritic cell-based immunotherapy in combination with an active component of OK-432, a streptococcal preparation. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5461–5470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pillarisetty VG, Katz SC, Bleier JI, et al. Natural killer dendritic cells have both antigen presenting and lytic function and in response to CpG produce IFN-gamma via autocrine IL-12. J Immunol. 2005;174:2612–2618. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prevost-Blondel A, Neuenhahn M, Rawiel M, et al. Differential requirement of perforin and IFN-gamma in CD8 T cell-mediated immune responses against B16.F10 melanoma cells expressing a viral antigen. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2507–2515. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2507::AID-IMMU2507>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prlic M, Blazar BR, Farrar MA, et al. In vivo survival and homeostatic proliferation of natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:967–976. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raulet DH. Natural killer cells. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental immunology. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincot, Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 365–392. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roder JC. The beige mutation in the mouse. I. A stem cell predetermined impairment in natural killer cell function. J Immunol. 1979;123:2168–2173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schreiber H. Tumor Immunology. In: Paul WE, editor. Fundamental immunology. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincot, Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 1557–1592. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sfondrini L, Balsari A, Menard S. Innate immunity in breast carcinoma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:301–308. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sidky YA, Borden EC, Weeks CE, et al. Inhibition of murine tumor growth by an interferon-inducing imidazoquinolinamine. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3528–3533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spaner DE, Masellis A. Toll-like receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:53–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taieb J, Chaput N, Menard C, et al. A novel dendritic cell subset involved in tumor immunosurveillance. Nat Med. 2006;12:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nm1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Whitmore MM, DeVeer MJ, Edling A, et al. Synergistic activation of innate immunity by double-stranded RNA and CpG DNA promotes enhanced antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5850–5860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.