Abstract

Aims

To examine the effects of route of administration and activation status on the ability of dendritic cells (DC) to accumulate in secondary lymphoid organs, and induce expansion of CD8+ T cells and anti-tumor activity.

Methods

DC from bone marrow (BM) cultures were labeled with fluorochromes and injected s.c. or i.v. into naïve mice to monitor their survival and accumulation in vivo. Percentages of specific CD8+ T cells in blood and delayed tumor growth were used as readouts of the immune response induced by DC immunization.

Results

The route of DC administration was critical in determining the site of DC accumulation and time of DC persistence in vivo. DC injected s.c. accumulated in the draining lymph node, and DC injected i.v. in the spleen. DC appeared in the lymph node by 24 h after s.c. injection, their numbers peaked at 48 h and declined at 96 h. DC that had spontaneously matured in vitro were better able to migrate compared to immature DC. DC were found in the spleen at 3 h and 24 h after i.v. injection, but their numbers were low and declined by 48 h. Depending on the tumor cell line used, DC injected s.c. were as effective or more effective than DC injected i.v. at inducing anti-tumor responses. Pre-treatment with LPS increased DC accumulation in lymph nodes, but had no detectable effect on accumulation in the spleen. Pre-treatment with LPS also improved the ability of DC to induce CD8+ T cell expansion and anti-tumor responses, regardless of the route of DC administration.

Conclusions

Injection route and activation by LPS independently determine the ability of DC to activate tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo.

Keywords: Rodents, Dendritic cells, CD8+ T cells, Tumor immunity

Introduction

The use of dendritic cells (DC) loaded with tumor antigens or whole tumor cells is a promising approach to tumor immunotherapy [1, 2]. DC are powerful initiators of the immune response and are able to activate CD4+ and CD8+ cells to infiltrate tumors and initiate tumor regression. While only a proportion of the tumor immunotherapy clinical trials carried out so far have yielded positive results, those using DC as carriers of tumor antigen have obtained among the highest rates of success [3]. A variety of DC sources and administration routes have been used, and the optimal protocol of DC administration has not been established.

Several factors are thought to be critical in determining whether immunization with antigen loaded DC will lead to a productive immune response. The activation status of the DC and their route of administration are both recognized to have a significant impact on the resulting immune response. Activation improves the ability of DC to migrate to lymph nodes [4], and also increases their expression of costimulatory molecules which are required for optimal T cell activation. Regarding the route of administration, several studies have reported that DC given subcutaneously (s.c.) or intradermally (i.d.) are able to induce protection against subcutaneous tumors, while DC given i.v. (intravenously) are often ineffective [5–8]. Additional studies measuring in vitro proliferation or cytotoxic activity have also established that DC given s.c. activate specific immune responses more effectively than DC given i.v. [5, 6, 8]. However, studies by other authors have reached opposing conclusions [7, 9–11]. Because some of these studies report only a partial analysis of the effects of DC vaccination, it is not always clear whether the failure to induce an effective immune response may have been due to the inability of the injected DC population to reach lymphoid organs, the inability to activate a response, or to other reasons.

In this study we undertook a systematic comparison of the effect of DC activation and route of injection on the ability of the DC to migrate to lymphoid organs, survive, and induce T cell expansion and T cell-dependent tumor protection. We find that while there is a broad correlation between the numbers of DC recovered from lymphoid organs and their ability to induce T cell responses, the number of DC recovered from secondary lymphoid organs is not by itself sufficient to predict the size of the response induced. Other parameters, especially activation status, also appear to play important roles in the activation of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME. TLR-4−/− [12] mice were kindly provided by Dr. S Akira, Hyogo College of Medicine, Japan. Line 318 mice, which carry a transgenic TCR specific for fragment 33–41 of the Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus glycoprotein (gp33) in association with H-2Db, were kindly provided by Prof H. Pircher, Institute for Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, Freiburg, Germany. Mice were maintained by brother × sister mating and used when 7–12 weeks old. All experimental protocols were approved by the Wellington School of Medicine and Victoria University of Wellington Animal Ethics Committees, and performed according to Institutional guidelines.

In vitro culture media and reagents

All cultures were in complete medium (cIMDM) composed of IMDM, 2 mM glutamax, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercapto-ethanol and 5% FBS (all Invitrogen, Auckland, NZ). The synthetic peptide gp33 (KAVYNFATM) was from Chiron Mimotopes, Clayton, Australia. LPS from E coli was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Castle Hill, NSW, Australia).

Culture of DC

To generate DC, bone marrow (BM) cells from C57BL/6 mice were cultured in complete medium containing 20 ng/ml IL-4 and 10 ng/ml GM-CSF prepared from the supernatant of producing cell lines [13] and tested against commercial cytokine preparations (Biosource, CA, USA). On day 7 cultures typically contained 70–90% CD11c+ cells. LPS to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml was added to the culture medium during the last 16 h of culture; control cultures received no addition. On day 7 DC were harvested and labeled with fluorochrome or loaded with antigen as described below.

FACS® analysis

Anti-FcγRII (2.4G2), anti-MHC II (3JP) anti-CD11c (N418) mAb were affinity purified from hybridoma culture supernatants using protein G-Sepharose (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), and conjugated to biotin, FITC, or APC. Anti-Vα2-PE, anti-Vβ 8.1, 8.2-biotin, anti-CD80-PE and anti-CD86-FITC were from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Expression of CCR7 was revealed using the fusion protein ELC-Ig [14], which was collected from the supernatants of cells transfected with an ELC-Ig expression vector kindly provided by Tim Springer, Harvard Medical School, Boston. PI (BD Biosciences) was added to all samples to exclude dead cells. All samples were analyzed on a FACSort (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) using the CellQuest (Becton Dickinson) or FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Asland, OR) software. Cell sorting was carried out on a FACS-DiVa (Becton Dickinson).

Fluorochrome labeling and in vivo DC migration assays

DC were harvested from culture, washed and resuspended in the appropriate buffer at room temperature. For labeling with carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), DC were resuspended in PBS at 5 × 106/ml, and CFSE was added to a final concentration of 1 μM. After 10 min at 37°C, cells were diluted in five volumes of cold PBS and washed in IMDM. DC were labeled with the orange fluorescent dye chloromethyl-benzoyl-aminotetramethyl-rhodamine (CMTMR, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) by resuspending in pre-warmed cIMDM at 5 × 106 cells/ml and incubating with 10 μM CMTMR at 37°C for 15 min, followed by incubation in cIMDM for a further 20 min. After labeling, equal numbers of CFSE and CMTMR-labeled cells were combined and injected s.c. into the volar aspect of the forelimb, or i.v. into the lateral tail vein of syngeneic mice. At different times, draining axillary and brachial lymph nodes or spleen were removed, digested in collagenase (Invitrogen) and DNase I (Sigma), and analyzed for the presence of fluorescent cells by flow cytometry.

DC immunization and tumor challenge experiments

After 7 days in culture, DC were collected, incubated with 10 μM gp33 peptide for 2 h at 37°C, and washed extensively. Mice were injected with the indicated numbers of gp33-loaded DC either s.c. into the volar aspect of the forelimb, or i.v. into the lateral tail vein. Seven days later mice were challenged into the flank with 106 LL-LCMV tumor cells [15], or 105 B16.gp33 tumor cells [16], which both express the relevant gp33 antigen. Tumor size was assessed by measuring the long and short tumor diameters using calipers, and is expressed as the mean product of tumor diameters ± SD. Tumor measurements for one group were terminated once a mouse in the group had developed a tumor exceeding 150 mm2 and had to be euthanised. Mice were scored as tumor free when the size of their tumors was less than 4 mm2.

Adoptive transfer of TCR transgenic T cells

Single cell suspensions were prepared from pooled lymph nodes and spleens of line 318 mice. Cells were washed in IMDM and the equivalent of about 3 × 106 Vα2+Vβ8+ T cells was injected intravenously into the lateral tail vein of C57BL/6 recipients. The percentage of antigen specific T cells in peripheral blood was determined by FACS staining at the indicated time points.

Results

Phenotype of DC from BM cultures

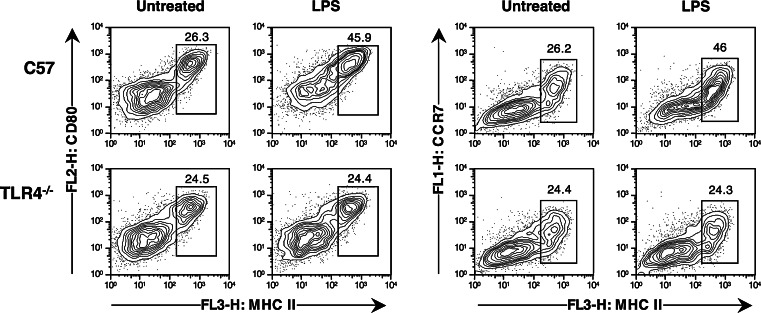

We first examined the phenotype of DC generated in BM cultures and activated in vitro by treatment with LPS. As shown in Fig. 1, DC from day 7 cultures that had not been treated with LPS included a majority of cells with an immature MHC IIlo CD80lo phenotype, while the remaining 20–30% expressed high levels of MHC II, CD80 and CD86 (data not shown). The presence of mature cells in these cultures was not due to potential endotoxin contaminations, as DC cultured from C57BL/6 and TLR4−/− mice displayed a similar mixed phenotype with mature and non-mature cells. Instead, these MHC IIhi CD80hi cells appear to represent a population that has spontaneously matured in vitro. Supplementation of the culture medium with 100 ng LPS/ml during the last 16 h of culture led to upregulation of MHC II and CD80 on all DC, and to an increase in the proportion of MHC II high, CD80 high cells. These increases became more marked if the time of culture in LPS, or LPS concentration, were further increased (data not shown). No similar increases were observed on TLR4−/− DC treated with the same dose of LPS.

Fig. 1.

Phenotype of DC generated in vitro. BM cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. LPS was added during the last 16 h of culture at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. At the end of 7 days, cultured cells were harvested, labeled with the indicated antibodies, and analyzed by FACS. Only PI−CD11c+ events are shown

The migration of DC from tissues to lymph nodes requires expression of the chemokine receptor CCR7 [17], which is acquired by DC upon maturation. We therefore carried out triple staining experiments to examine expression of CCR7 on DC preparations. As shown in Fig. 1, spontaneously matured C57BL/6 and TLR4−/− DC, which expressed increased levels of MHC II and CD80, also expressed increased levels of CCR7. Treatment with LPS increased the proportion of C57BL/6 cells expressing CCR7, but did not detectably increase expression of CCR7 on TLR-4−/− DC.

Migratory ability of DC from BM cultures

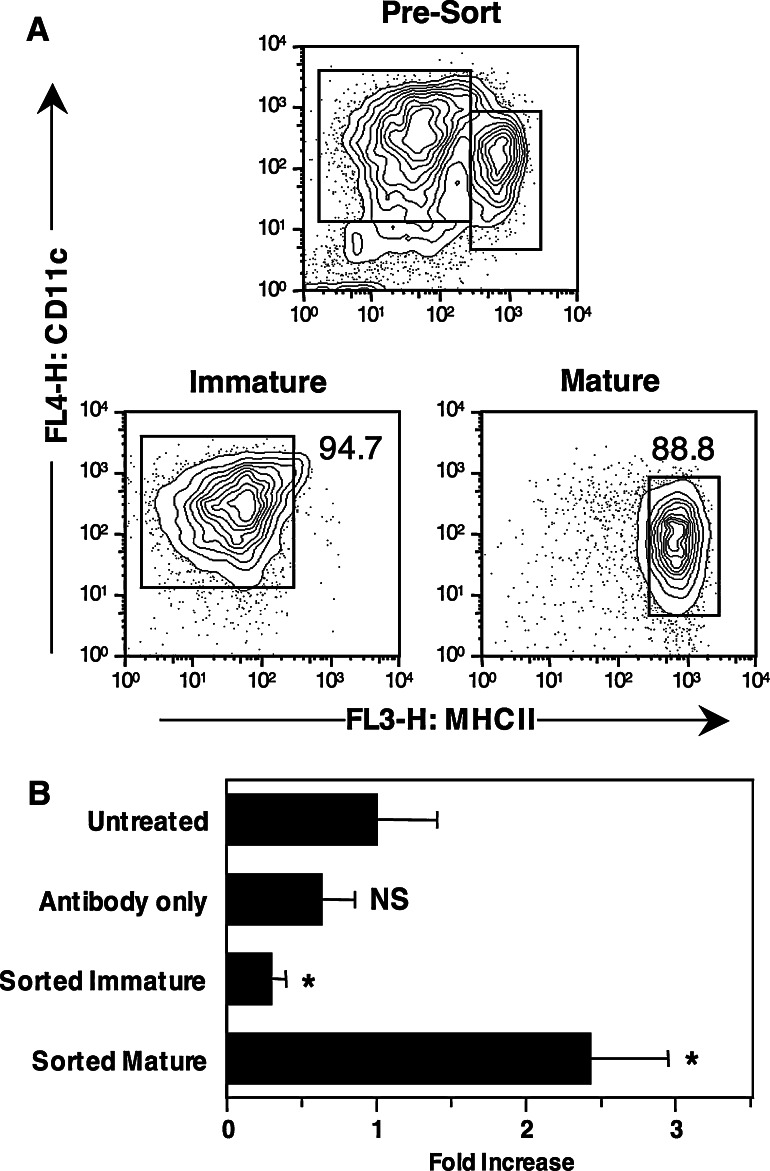

DC generated from BM cultures, labeled with CFSE and injected s.c. into mice can be recovered from the pooled brachial and axillary lymph nodes 1–3 days after injection [18], indicating that these cells are able to actively migrate to the lymph node. Because DC generated in culture were heterogeneous and included mature and immature populations, we wished to establish whether both subpopulations were equally able to contribute to migration in vivo. DC from day 7 cultures were electronically sorted into mature and immature cells on the basis of their expression of MHC II. As shown in Fig. 2a, sorted populations were 88.8 and 94.7% pure, respectively. Each population was then labeled with CFSE and injected s.c. into mice together with a total DC population labeled with CMTMR, which served as an internal reference. To control for the effects of the antibody used for staining on the migration and survival of DC in vivo, pre-sort populations that were or were not labeled with antibodies were also labeled with CFSE and injected s.c. As shown in Fig. 2b, untreated DC populations labeled with CFSE or CMTMR were recovered from the draining lymph node at the expected ratio of approximately one. A small decrease in recovery was observed for pre-sort DC that had been pre-incubated with antibodies, but this decrease was not statistically significant when compared to the untreated group (P = 0.2 by a Student’s t test). In contrast, the accumulation of sorted immature DC in lymph node was markedly lower than the accumulation of the reference population (P = 0.033), while the accumulation of mature DC was about 2.5 times higher (P = 0.031). We conclude that the mature cells present in mixed DC populations are responsible for most of the migration to the lymph node. Our data do not allow us to conclude whether immature DC were able to migrate to the draining lymph node at a limited rate or not at all, as some DC could have spontaneously matured after sorting.

Fig. 2.

Spontaneously matured DC injected s.c. migrate more efficiently to the draining lymph node than immature DC. BM cells were cultured for 7 days in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. At the end of 7 days cells were harvested and labeled with fluorescent antibodies for cell sorting. a Profiles of the pre-sort and sorted populations. Percentages of events falling within the indicated gates are shown. b Sorted populations from A were labeled with CFSE, combined with untreated DC labeled with CMTMR to serve as a reference population, and injected s.c. into recipient mice. Untreated DC, and DC that had been labeled with fluorescent antibodies but not sorted, were also labeled with CFSE, combined with CMTMR labeled cells, and injected into mice to control for the effect of antibody binding on in vivo migration. Cells were recovered from the draining lymph node 48 h after injection. The average ± SE fold-increase in the percentage of recovered CFSE+ cells compared to CMTMR+ reference cells was calculated in groups of four to six mice. NS not significant, *P < 0.05 by a one-tailed Student’s t test

LPS treatment improves the accumulation of DC in the draining lymph node but not in the spleen

Given the preferential ability of spontaneously matured DC to migrate to the draining lymph node, we tested whether maturation by LPS treatment would similarly improve the ability of DC to migrate to secondary lymphoid organs after s.c. or i.v. injection. DC cultures were treated with LPS at 100 ng/ml for 16 h, as longer LPS treatments have been reported to induce DC exhaustion and decreased stimulatory ability [19, 20]. DC were then labeled with CFSE, mixed with equal numbers of non-LPS treated DC labeled with CMTMR, and injected into naïve mice. Extensive preliminary experiments where treated and untreated DC were injected separately or together indicated that mixing the two populations did not affect their ability to migrate in vivo, and that the choice of fluorochrome did not affect the relative ability of the two populations to migrate and survive in vivo (data not shown).

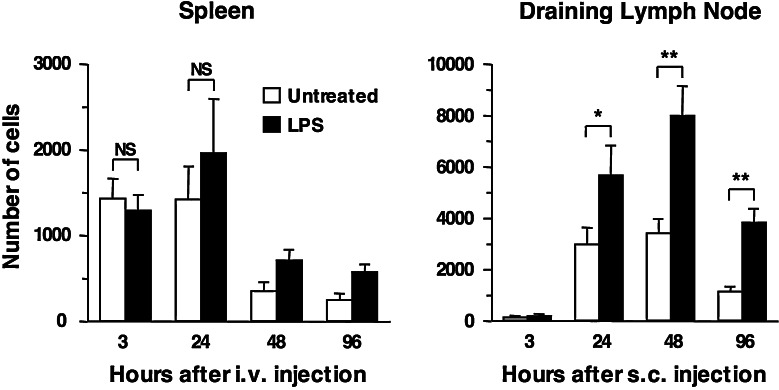

As shown in Fig. 3, LPS treatment improved the ability of DC to migrate to the lymph node, with about twice as many DC being recovered from the draining lymph node at each time point. Although more DC were reaching the lymph node, the kinetics of DC accumulation and survival in the draining lymph node were not altered by LPS treatment. Very few DC were detectable in the draining lymph node at 3 h after injection, maximum numbers of DC were recovered at 48 h, and numbers started to decline thereafter, regardless of LPS treatment. We also tested whether DC injected s.c. could be recovered from other tissues besides the draining lymph node. At 20 h after injection, no labeled DC were recovered from non-draining lymph nodes, spleen, lung or liver of recipient mice, regardless of whether DC had been treated with LPS or not (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Accumulation of untreated or LPS-treated DC in spleen and lymph node after i.v. or s.c. injection. DC were generated and activated with LPS as described in the legend to Fig. 1. At the end of culture, untreated and LPS-treated DC were harvested and labeled with the fluorescent markers CFSE and CMTMR, combined in equal numbers, and injected into recipient mice. Cells were recovered at the indicated times from spleen and lymph nodes of i.v. or s.c. injected mice, respectively. Bars indicate the average number of DC in spleens or draining lymph nodes, ±SE. Combined data from two experiments, each using three mice per group, are shown. *0.01 < P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, NS not significant, as determined by a one-tailed Student’s t test

We also asked whether LPS treatment would similarly improve the migration of DC injected i.v. As shown in Fig. 3, LPS treatment did not affect the ability of DC injected i.v. to accumulate in the spleen. Figure 3 also shows that the accumulation of DC in the spleen appeared to be faster but more inefficient compared to accumulation in the lymph node. The peak number of DC recovered from the spleen after i.v. injection was lower than the number recovered from the draining lymph node after s.c. injection, even if equal numbers of cells were injected. In addition, the number of DC in spleen declined after 24 h. Analysis of other tissues (data not shown) revealed that very few of the i.v. injected DC reached the lung and the lung-draining mediastinal lymph node, while no DC were found in other lymph nodes (e.g., skin-draining lymph nodes).

We conclude that LPS-induced maturation improves the ability of DC to accumulate in the draining lymph node after s.c. injection, while accumulation in the spleen is relatively inefficient regardless of the maturation state of the injected DC.

Induction of CD8+ T cell responses by immunization with untreated and LPS-treated DC

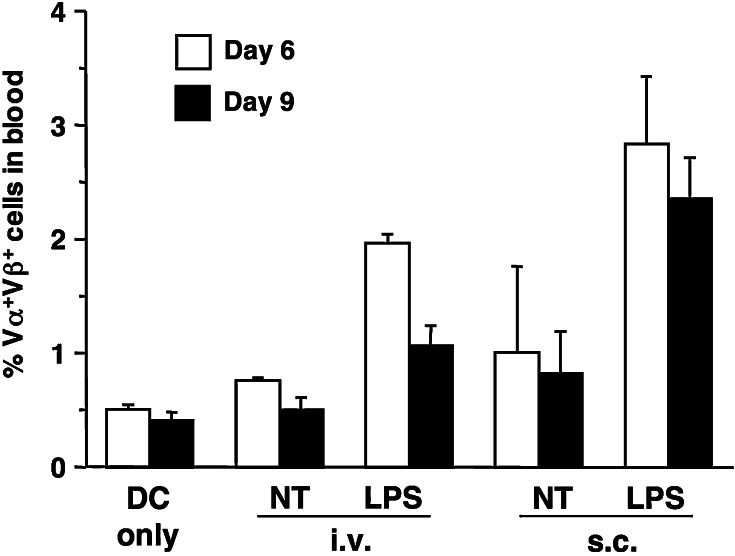

To establish whether the numbers of DC accumulating in lymphoid organs was indicative of their ability to initiate T cell responses, we examined the percentage of adoptively transferred CD8+ TCR transgenic T cells in the blood of mice immunized with 105 gp33 peptide-loaded DC that had been pretreated with LPS for 16 h, or left untreated, and were injected s.c. or i.v. As shown in Fig. 4, there were differences between responses induced by the various immunization protocols: compared to DC injected i.v., DC injected s.c. induced a higher increase in the percentage of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in blood, and LPS-treated DC induced a higher increase than untreated DC. LPS treatment was necessary to obtain a significant increase over background. Although LPS-treated DC injected i.v. could be detected in the spleen for only a short time after injection, they were nonetheless able to induce a clear increase in the percent of antigen specific T cells in blood.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of antigen-specific T cells in the blood of DC-immunized mice. C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with Vα2Vβ8+ T cells from line 318 mice. On the next day mice received 105 DC that had been generated and activated with LPS as described in the legend to Fig. 1. DC were loaded with gp33 peptide and injected as indicated, or left untreated and injected i.v. Aliquots of peripheral blood were collected on days 6 and 9 after immunization, and the percentage of antigen-specific Vα2Vβ8+ T cells was determined by FACS staining. Bars represent the average percentage of antigen-specific T cells ± SE for groups of three mice. Results shown are from one of two experiments that gave similar results

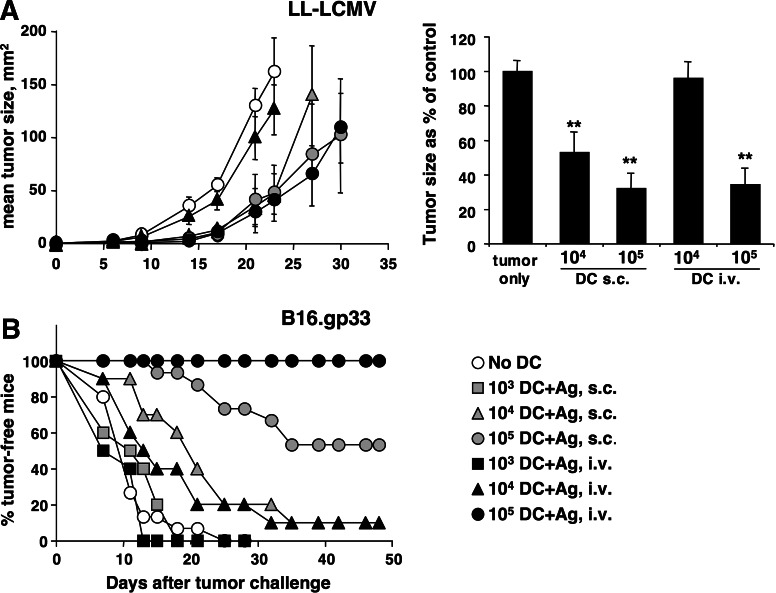

As a further comparison of the CD8+ T cell responses induced by antigen-loaded DC, we examined the ability of DC-injected mice to resist s.c. challenge with tumor cell lines expressing the gp33 epitope. In each experiment, graded numbers of DC were injected in an attempt to obtain a quantitative comparison. Figure 5a shows the results of experiments using DC not activated by LPS, and the Lewis lung cell carcinoma LL-LCMV tumor, which expresses low levels of gp33. Results from one representative experiments are shown in the left panel while cumulated data from three independent experiments are shown in the right panel. DC injected s.c. or i.v. were both able to induce some retardation in tumor growth, however, the response induced by DC given i.v. was weaker. Injection of 104 cells by the i.v. route did not induce a delay in tumor growth, while 104 DC given s.c., and 105 DC given s.c. or i.v., gave clear and comparable delays in tumor growth. Figure 5b shows the result of similar experiments but using a different tumor cell line, the B16.gp33 melanoma. B16.gp33 expresses higher levels of gp33 compared to LL-LCMV [21], and appears more sensitive to immune responses induced by DC immunization. Because B16.gp33 tumors progress very rapidly, data are shown as percent tumor-free mice as, for this tumor, they are more representative of the overall result of the experiment. Again, both routes of DC injection were effective at delaying the growth of B16.gp33 tumors. However, 105 peptide-loaded DC injected i.v. induced a stronger anti-tumor response than the same number of DC injected s.c. When lower numbers of peptide-loaded DC were used, they were as effective or more effective when given s.c.

Fig. 5.

Injection route differentially affects the ability of DC to induce immune responses against s.c. tumors. DC were generated as described in the legend to Fig. 1. At the end of culture cells were harvested, loaded with gp33 peptide, washed, and the indicated cell numbers were injected into recipient mice by the indicated route. Seven days after DC immunization mice were injected with tumor cells s.c. into the flank, and tumor growth was measured regularly thereafter. a LL-LCMV tumors. The left panel shows average tumor sizes in one representative experiment using five mice per group; mean tumor sizes ± SE are shown. The right panel shows cumulated data from three independent experiments: in each experiment tumor sizes were taken on the day when tumor size in the tumor-only control group was closest to 100 mm2 (day 18–24), and are expressed as % of the size in the tumor-only control group. **P < 0.001 by a one-tailed Student’s t test. b B16.gp33 tumors. Percent tumor-free mice were obtained by combining three independent experiments, each using five mice per group

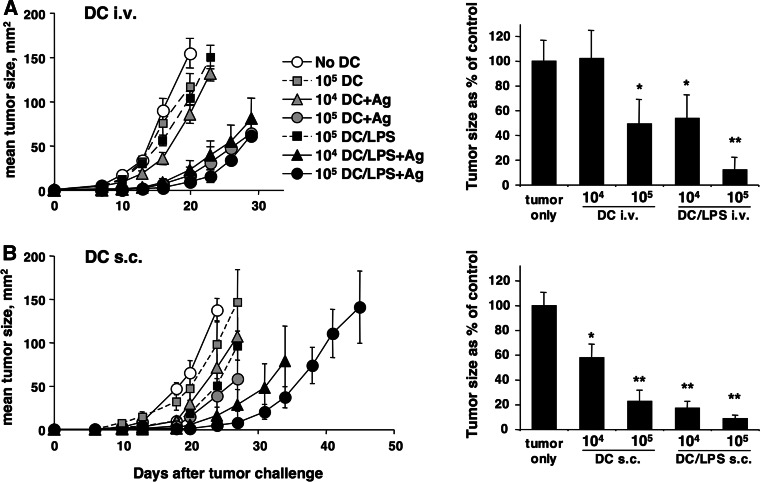

Further experiments were aimed at establishing the effect of LPS activation on the ability of DC to initiate anti-tumor immune responses. The left panel of Fig. 6a shows the results of a representative experiment where graded numbers of untreated or LPS-activated DC were injected i.v. before challenge with LL-LCMV, while the right panel shows cumulated data from two independent experiments. LPS activation considerably increased the ability of DC to induce anti-tumor responses, with 104 LPS-treated DC inducing similar or better responses than 105 DC not treated with LPS. Similarly, Fig. 6b shows that LPS treatment also increased the capacity of s.c. injected DC to induce anti-tumor responses. While untreated DC induced only partial responses in this experiment, 105 LPS treated DC were able to significantly delay tumor growth in immunized mice. Therefore, DC injected s.c. or i.v. are both able to induce anti-tumor immune responses, and this activity is increased if DC are activated by LPS before injection in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Activation with LPS improves the ability of Ag-loaded DC injected s.c. or i.v. to induce anti-tumor immune responses. DC were generated and activated with LPS as described in the legend to Fig. 1. At the end of culture cells were harvested, loaded with gp33 peptide, washed, and the indicated numbers were injected into recipient mice. Seven days after DC immunization mice were injected with LL-LCMV tumor cells s.c. into the flank, and tumor growth was measured regularly thereafter. a DC injected i.v. b DC injected s.c. In left panels symbols represent average tumor size in one representative experiment using five mice per group, ±SE. Right panels shows cumulated data from two (a) or three (b) independent experiments: in each experiment tumor sizes were taken on the day when tumor size in the tumor-only control group was closest to 100 mm2 (day 16–24 in a, and day 20–24 in b), and are expressed as % of the size in the tumor-only control group. *0.001 < P < 0.05, **P < 0.001 by a one-tailed Student’s t test

Discussion

In this paper we describe the effects of injection route and maturation status on the accumulation of DC in secondary lymphoid organs, and on their ability to induce anti-tumor immune responses. While the effects of these parameters on the success of DC vaccination have been examined before, they were studied separately or in the absence of dose-responses, thus precluding a conclusive interpretation of the results.

We have simultaneously examined maturation status and injection route of DC, and related effects on DC homing to secondary lymphoid organs to effects on the DC’s ability to induce anti-tumor immune responses. We report that the s.c. injection route was clearly superior to the i.v. route: DC injected s.c. accumulated in secondary lymphoid organs in higher numbers compared to i.v. injected DC, persisted for a longer time, and induced better anti-tumor immune responses against the LL-LCMV tumor. Therefore, the injection route was important in determining the number of DC that reached lymphoid organs, and the resulting anti-tumor response. In addition, we report that LPS increased the ability of s.c. injected DC to accumulate in the lymph node about twofold, while the DC’s ability to initiate anti-tumor immune responses was increased more than tenfold, as shown by the fact that, compared to untreated DC, tenfold fewer LPS-activated DC were necessary to obtain a similar degree of tumor protection. The accumulation of i.v. injected DC in the spleen was not increased by LPS, but their ability to induce anti-tumor immune responses was again increased by about tenfold. Therefore, DC activation status made a substantial contribution to T cell activation, which was only partially explained by differences in the ability of DC to accumulate in lymphoid organs [22]. This suggests that, on a per-cell basis, LPS-activated DC are much better initiators of anti-tumor immune responses than spontaneously matured DC. Differential secretion of cytokines by spontaneously matured versus LPS-activated DC might be one explanation for this observation [23, 24].

Our studies examining the ability of DC injected via different routes to home to lymphoid organs revealed strong effects of the injection route on both homing kinetics, and in the effects of activation on the ability of DC to accumulate in lymph nodes and spleen. DC injected s.c. required several hours to appear in the draining lymph node, with very few or no DC being detected in the lymph node 4–6 h after injection (data not shown), and almost peak numbers being recovered at 24 h. The numbers of DC in lymph nodes further increased by 48 h, especially when DC had been activated by LPS treatment, and slowly declined thereafter. There was no difference in the rate at which untreated or LPS-activated DC disappeared from lymph node, suggesting that DC survival was not affected. Thus, the main effect of LPS was to facilitate the entry of DC into the lymph node, which correlated with the increased expression of CCR7 on LPS-activated DC. In contrast to the lymph node, accumulation of i.v. injected DC in the spleen did not detectably improve when DC were activated with LPS, indicating that, as suggested by others [25], access to spleen was regulated by different mechanisms compared to access to lymph nodes. The kinetics of DC accumulation in spleen were also very different from the kinetics in lymph node, with numbers of DC recovered from spleen being highest at 3–24 h after injection, and then declining at 48 h. We did not investigate whether this decline was due to spontaneous death of the injected cells, or active elimination. Over several experiments, the total number of DC recovered from spleen was also considerably lower than the number recovered from lymph node, suggesting that i.v. injected DC largely lacked the molecular signals required for spleen homing. A similar observation has been reported by Cavanagh et al. [26], who used semi-purified spleen DC to show that the number of DC in spleen was highest at 4 h and declined thereafter, and that maturation did not increase accumulation of these DC in the spleen.

Despite the small number of DC found in the spleen, and their rapid disappearance, i.v. injection was effective at inducing some CD8+ T cell responses. We assume that these CD8+ responses were directly initiated by the injected DC, as our previous experiments using gp33-loaded DC injected into C57 or bm13 hosts showed that host APC were not required for the induction of a CD8+ response [27]. A second possibility is that the CD8+ response was not induced by injected DC in spleen, but by the DC that had homed to other organs. We did note that a small proportion of the i.v. injected DC could be recovered from the lung and the lung draining mediastinal lymph node, but not from other lymph nodes (data not shown). Because the number of these DC was much smaller than the number recovered from the spleen, we feel that they were unlikely to be significant contributors to the response induced by i.v. injected DC.

Mullins and Engelhard have reported that, 24 h after i.v. injection of DC, about 30% of the injected cells can be recovered from recipient spleens [11, 28]. The same authors also reported that DC injected s.c. migrate to the draining lymph node first, and then the spleen once the lymph node is “saturated”. In our studies, we were unable to demonstrate any DC in the spleen after s.c. injection, and even after i.v. injection the number of DC in spleen remained low. One possible reason for this discrepancy is that our DC were either spontaneously matured or activated with low doses of LPS, while Mullins et al. used DC activated by O/N culture with CD40L expressing cells. It has been reported that DC homing to spleen requires the presence of T cells [25], and it is possible that CD40L signal may decrease or replace this requirement. Our findings are nonetheless consistent with most reports where homing of DC injected s.c. or i.v. were examined [5, 25, 26, 29], and found to be largely restricted to lymph node or spleen, respectively.

Anti-tumor immune responses induced by i.v. injection of DC have been examined by several authors, and reported to be weak or undetectable [5–8]. Over a number of experiments using the LL-LCMV tumor, we observed that DC injected i.v. were able to initiate strong responses, but that about tenfold more DC were required for i.v. injection compared to s.c. injection. I.v. injected DC were also effective at inducing responses against the B16.gp33 tumor. It is possible that our ability to demonstrate anti-tumor responses after administration of DC i.v. was due to the use of a strong antigen such as gp33. We observed that, compared to gp33, induction of a CD8+ response to H-Y requires much higher numbers of DC, and a longer time (K. Matthews and F. Ronchese, in preparation). The i.v. route may not be suitable to reach accumulation of sufficient number of DC when immunizing against antigens such as H-Y.

Lastly, one parameter not often considered in the literature is the type of tumor against which a response is being tested. Most of the experiments we carried out involved sub-cutaneous challenge with the weakly antigenic LL-LCMV tumor [15], and this tumor responded best to DC injected s.c. We were surprised to find that a different tumor cell line, B16.gp33 [16], instead was most responsive to high numbers of DC injected i.v. DC are known to activate NK cells [30], which also mediate potent anti-tumor activity in vivo, and it is possible that non-antigen specific effector mechanisms may have contributed to tumor protection in this case. However, this possibility was not further investigated.

In conclusion, we report that activation and route of injection both substantially contribute to the ability of DC to accumulate in secondary lymphoid organs, and induce CD8+ immune responses in vivo. We also report that the number of DC that reach lymphoid organs is not directly proportional to the anti-tumor response induced, suggesting that other parameters, such as expression of costimulatory molecules and cytokine production, are also critical contributors to the DC’s ability to activate immune responses. Lastly, we show that different tumors may vary in their sensitivity to responses induced using different protocols of DC administration. Thus the design of clinical protocols of DC immunotherapy may need to take into account the sensitivity of individual tumor isolates to different immune effector mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff of the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research for constructive suggestions and advice, and the Staff at the Biomedical Research Unit of the Wellington School of Medicine and Malaghan Experimental Research Facility for animal husbandry and care. This work was supported by a research grant from the Cancer Society of NZ to FR, and from equipment grants from the NZ Lottery Health Board and the Wellcome Trust. Financial support from the Health Research Council of NZ is also acknowledged. The authors declare no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations

- BM

Bone marrow

- CFSE

Carboxy-fluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester

- cIMDM

Complete IMDM

- CMTMR

Chloromethyl-benzoyl-aminotetramethyl-rhodamine

- DC

Dendritic cell

- i.v.

Intravenous/ly

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- PI

Propidium iodide

- s.c.

Subcutaneous/ly

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

References

- 1.Cerundolo V, Hermans IF, Salio M. Dendritic cells: a journey from laboratory to clinic. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:7–10. doi: 10.1038/ni0104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin-Fontecha A, Sebastiani S, Hopken UE, Uguccioni M, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Regulation of dendritic cell migration to the draining lymph node: impact on T lymphocyte traffic and priming. J Exp Med. 2003;198:615–621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggert AA, Schreurs MW, Boerman OC, Oyen WJ, de Boer AJ, Punt CJ, Figdor CG, Adema GJ. Biodistribution and vaccine efficiency of murine dendritic cells are dependent on the route of administration. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3340–3345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fong L, Brockstedt D, Benike C, Wu L, Engleman EG. Dendritic cells injected via different routes induce immunity in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2001;166:4254–4259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert LA, Gibson GR, Maloney M, Durell B, Noelle RJ, Barth RJ., Jr Intranodal immunization with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells enhances protective antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2001;61:641–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serody JS, Collins EJ, Tisch RM, Kuhns JJ, Frelinger JA. T cell activity after dendritic cell vaccination is dependent on both the type of antigen and the mode of delivery. J Immunol. 2000;164:4961–4967. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Schoenberger SP, Drijfhout JW, van Bloois L, Storm G, Kast WM, Offringa R, Melief CJ. Enhancement of tumor outgrowth through CTL tolerization after peptide vaccination is avoided by peptide presentation on dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:4449–4456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi H, Nakagawa Y, Yokomuro K, Berzofsky JA. Induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes by immunization with syngeneic irradiated HIV-1 envelope derived peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 1993;5:849–857. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.8.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullins DW, Sheasley SL, Ream RM, Bullock TN, Fu YX, Engelhard VH. Route of immunization with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells controls the distribution of memory and effector T cells in lymphoid tissues and determines the pattern of regional tumor control. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1023–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karasuyama H, Melchers F. Establishment of mouse cell lines which constitutively secrete large quantities of interleukin 2, 3, 4 or 5, using modified cDNA expression vectors. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:97–104. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manjunath N, Shankar P, Wan J, Weninger W, Crowley MA, Hieshima K, Springer TA, Fan X, Shen H, Lieberman J, von Andrian UH. Effector differentiation is not prerequisite for generation of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:871–878. doi: 10.1172/JCI13296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermans IF, Daish A, Moroni-Rawson P, Ronchese F. Tumor-peptide-pulsed dendritic cells isolated from spleen or cultured in vitro from bone marrow precursors can provide protection against tumor challenge. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1997;44:341–347. doi: 10.1007/s002620050392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prevost-Blondel A, Zimmermann C, Stemmer C, Kulmburg P, Rosenthal FM, Pircher H. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes exhibiting high ex vivo cytolytic activity fail to prevent murine melanoma tumor growth in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;161:2187–2194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohl L, Mohaupt M, Czeloth N, Hintzen G, Kiafard Z, Zwirner J, Blankenstein T, Henning G, Forster R. CCR7 governs skin dendritic cell migration under inflammatory and steady-state conditions. Immunity. 2004;21:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermans IF, Ritchie DS, Yang J, Roberts JM, Ronchese F. CD8+ T cell-dependent elimination of dendritic cells in vivo limits the induction of antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:3095–3101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camporeale A, Boni A, Iezzi G, Degl’Innocenti E, Grioni M, Mondino A, Bellone M. Critical impact of the kinetics of dendritic cells activation on the in vivo induction of tumor-specific T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3688–3694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langenkamp A, Messi M, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Kinetics of dendritic cell activation: impact on priming of TH1, TH2 and nonpolarized T cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:311–316. doi: 10.1038/79758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rawson P, Hermans IF, Huck SP, Roberts JM, Pircher H, Ronchese F. Immunotherapy with dendritic cells and tumor major histocompatibility complex class I-derived peptides requires a high density of antigen on tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4493–4498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labeur MS, Roters B, Pers B, Mehling A, Luger TA, Schwarz T, Grabbe S. Generation of tumor immunity by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells correlates with dendritic cell maturation stage. J Immunol. 1999;162:168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sporri R, Reise Sousa C. Inflammatory mediators are insufficient for full dendritic cell activation and promote expansion of CD4+ T cell populations lacking helper function. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:163–170. doi: 10.1038/ni1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valenzuela J, Schmidt C, Mescher M. The roles of IL-12 in providing a third signal for clonal expansion of naive CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:6842–6849. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Austyn JM, Morris PJ. Migration patterns of dendritic cells in the mouse. Traffic from the blood, and T cell-dependent and -independent entry to lymphoid tissues. J Exp Med. 1988;167:632–645. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavanagh LL, Bonasio R, Mazo IB, Halin C, Cheng G, van der Velden AW, Cariappa A, Chase C, Russell P, Starnbach MN, Koni PA, Pillai S, Weninger W, von Andrian UH. Activation of bone marrow-resident memory T cells by circulating, antigen-bearing dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1029–1037. doi: 10.1038/ni1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie DS, Yang J, Hermans IF, Ronchese F. B-lymphocytes activated by CD40 ligand induce an antigen-specific anti-tumour immune response by direct and indirect activation of CD8(+) T-cells. Scand J Immunol. 2004;60:543–551. doi: 10.1111/j.0300-9475.2004.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullins DW, Engelhard VH. Limited infiltration of exogenous dendritic cells and naive T cells restricts immune responses in peripheral lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2006;176:4535–4542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morse MA, Coleman RE, Akabani G, Niehaus N, Coleman D, Lyerly HK. Migration of human dendritic cells after injection in patients with metastatic malignancies. Cancer Res. 1999;59:56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez NC, Lozier A, Flament C, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Bellet D, Suter M, Perricaudet M, Tursz T, Maraskovsky E, Zitvogel L. Dendritic cells directly trigger NK cell functions: cross-talk relevant in innate anti-tumor immune responses in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:405–411. doi: 10.1038/7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]