Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and play a central role in the host-antitumor immunity. Since it has been reported that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibits the functional maturation of immature-DCs and impairs DC differentiation, it is important to elucidate the mechanisms of VEGF-induced DC-dysfunction. To investigate the effects of VEGF against human mature DCs, we investigated how VEGF affects mature DCs with regards to phenotype, induction of apoptosis, IL-12(p70) production and the antigen-presenting function evaluated by allogeneic mixed leukocyte reaction (allo-MLR). We generated monocyte-derived DCs matured with lipopolysaccharide, OK-432 or pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktails. As a result, VEGF treatment did not alter the mature DCs with regard to phenotype, IL-12(p70) production and induction of apoptosis. As a novel and important finding, VEGF inhibited the ability of mature DCs to stimulate allogeneic T cells. Furthermore, this VEGF-induced DC dysfunction was mainly mediated by VEGF receptor-2 (VEGF R2). These observations were confirmed by the findings that the VEGF-induced DC dysfunction was recovered by anti-human VEGF neutralizing mAb or anti-human VEGF R2 blocking mAb, and that placenta growth factor (PlGF), VEGF R1-specific ligand, did not have any effect against mature DCs. Some modalities aiming at reversing mature-DC dysfunction induced by VEGF will be needed in order to induce the effective antitumor immunity.

Keywords: VEGF, DC, KDR, OK-432, LPS

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs), which are the most potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs), play a central role in the host’s antitumor immunity. The defective function of DCs in cancer-bearing hosts has been reported by many groups [4, 5, 17, 18]. DCs failed to present tumor-specific antigen [4, 18] and transfer it to the naive T cells in patients with advanced-stage cancer [18], and reduced expression of B7 molecules in tumor-infiltrating DCs was shown [4]. Moreover, the population of DCs was down-regulated and the population of infiltrating DCs was significantly related to poor prognosis in several types of cancer patients, including gastric cancer, lung cancer, colon cancer, esophageal cancer and carcinoma of the uterine cervix [2, 3, 14, 27, 38].

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates the proliferation of the endothelium and acts as an angiogenic factor in vivo [8], is produced by most cancer cells. VEGF production by tumors was reported to be associated with poor prognosis in osteosarcoma [24], gastric cancer [35] and lung cancer [28]. Several soluble factors, including VEGF, have been implicated in defective DC maturation [16]. In particular, it was reported that VEGF inhibits the functional maturation of immature-DCs (im-DCs) [10, 15, 16, 19, 23, 32] and impairs DC differentiation [1, 16, 20, 31], as it was shown that the blockade of VEGF by anti-VEGF neutralizing antibody or anti-VEGF receptor antibodies recovered the function of DCs [10, 16, 23]. Moreover, it has recently been shown that there are differential roles of VEGF receptors 1 (VEGF R1) and 2 (VEGF R2) in DC differentiation [10]. Thus, the inhibition of DC-differentiation and -maturation by VEGF is one of the important events when the tumor burden alters the function of DCs [1, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20, 23, 31, 32]. Clinically, cancer vaccination using matured DCs pulsed with tumor-rejection antigens were under investigation. When immunotherapy using mature-DCs against cancer patients is considered, VEGF-related inhibitory effect of DCs is a crucial point that must be resolved. Although it has been reported that VEGF inhibits the DC-differentiation and the maturation from im-DCs [1, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20, 23, 31, 32], there are no previous reports describing how VEGF affects fully-matured DCs, particularly in human mature DCs. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the effect of VEGF against mature-DCs, which were generated from human blood monocytes and matured with several different kinds of stimulation.

In the present study, we generated monocyte-derived DCs and matured them with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [34, 38, 39], Streptococcal preparation (OK-432) [13, 29] or pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktails (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and PGE2) [9, 22, 39, 40]. Then, we investigated the effect of VEGF on mature DCs with respect to phenotypical changes, IL-12(p70) production, apoptosis and antigen-presenting activity evaluated by allo-MLR. As a result, we demonstrated that VEGF inhibited the antigen-presenting function of the mature-DCs and this inhibition might be predominantly mediated by the VEGF R2 (Flk-1/KDR) receptor.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and cytokines

The following mAbs were used for flow cytometric analysis: FITC-conjugated anti-human CD11c (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), RPE-Conjugated anti-human CD14 (DaKoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), FITC-anti-human CD80 (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA), PE-anti-human CD83 (Becton Dickinson Biosciences), CD86/FITC (DAKO), anti-human HLA-ABC antigen (MHC-classI) (DAKO), anti-human HLA-DR antigen (MHC-classII) (DAKO), FITC-conjugated polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins (DaKoCytomation), PE-conjugated immunoglobulins (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL), Anti-human VEGF R1 (Flt-1)-Phycoerythrin (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), Anti-human VEGF R2 (KDR)-Phycoerythrin (R&D Systems). Anti-human neutralizing VEGF mAb, Anti-human blocking VEGF R1 (Flt-1) and VEGF R2 (Flk-1/KDR) mAbs were purchased from R&D Systems. Mouse IgG1 isotype control and normal goat IgG control were also purchased from R&D Systems.

The following cytokines and reagents were used for cell cultures: granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, Peprotech EC, London, UK) and interleukin (IL)-4 (Peprotech EC), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), prostaglandin (PG) E2 (Sigma), IL-1β (Sigma), IL-6 (Sigma), OK-432 (Chugai Pharmaceutical co., Tokyo, Japan) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma).

Recombinant human vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165) and recombinant human placenta growth factor (PlGF) were purchased from R&D Systems.

T cell preparation

T cells were separated from the peripheral blood used by RossetteSep human T cell enrichment cocktail (StemCell technologies, Vancouver, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells

DCs were generated from peripheral blood monocytes from healthy donors. Briefly, peripheral blood monocytes were separated from the peripheral blood used by RossetteSep human monocyte enrichment cocktail (StemCell technologies, Vancouver) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Monocytes were purified to more than 90% purity, as confirmed by flow cytometry using anti-CD14 monoclonal antibodies (Dako).

These cells, monocytes (2.0 × 105 cells/ml), were cultured in a 6-well flat bottom plate (Becton Dickinson Biosciences) with 500 units/ml of GM-CSF and 500 units/ml of IL-4 in 2 ml X-VIVO (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). On day 4, immature DCs (im-DC) were matured with 100 ng/ml of LPS (LPS-DC), 20 μg/ml of OK-432 (OK-DC) or a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail (10 ng/ml of TNF-α, 1μg/ml of PGE2, 10 ng/ml of IL-1β and 1,000 U/ml of IL-6) (co-DC) as described in previous reports [9, 13, 22, 29, 34, 38–40]. On day 6, LPS-, OK- or co-DC were used for the experiments as mature DCs. Immature DCs were prepared differently from the same donors as the 4 day cultures of monocytes with IL-4 and GM-CSF in each experiment. Both im-DC and mature-DCs were purified to more than 95% purity, as confirmed by anti-human CD11c mAb.

VEGF treatment of DCs

DCs (im-DC, LPS-DC, OK-DC and co-DC 1 × 105/ml) were treated with or without VEGF165 as indicated concentrations in 2 ml of X-VIVO at 37°C for 24 h in combination with mouse anti-human neutralizing VEGF mAb (0.2 μg/ml), goat anti-human blocking VEGF R1 mAb (10 μg/ml) and mouse anti-human blocking VEGF R2 mAb (50 ng/ml). Mouse IgG1 isotype control Abs and normal goat IgG control Abs were used as the negative control. After each treated DCs were washed using X-VIVO two times, we used these cells for experiments.

Allogeneic mixed leukocyte reaction (allo-MLR)

To evaluate the ability of each DC to stimulate the proliferation of allogeneic T cells, an MLR assay was performed. Briefly, after treated DCs, which were described in Materials and methods (VEGF treatment of DCs), were irradiated at 20 Gy, and then these cells were washed using X-VIVO two times. After these treatments, 1 × 105 allogeneic T cells were co-incubated in triplicate with each DC at various ratios in a 96-well U-bottom plate (Becton Dickinson Biosciences). After 96 h incubation, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA) was added to each well. The cells were cultured for 18 h and then thymidine incorporation was measured in counts per minute (cpm).

Flow cytometric analysis of DCs

Phenotypical analysis of im-DC and mature DCs was performed using mAbs by FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson Biosciences), including CD11c, CD14, CD80, CD83, CD86, MHC classI, MHC classII, VEGF R1 (Flt-1) and VEGF R2 (KDR). Unlabeled mAbs (MHC classI, MHC classII) were visualized using FITC-conjugated immunoglobulins. FITC-conjugated immunoglobulins or PE-conjugated immunoglobulins as a negative control were used for immunostaining with flow cytometric analysis.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from monocytes, im-DCs and mature DCs (LPS-, OK- and co-DC) using an RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

RT-PCR experiments were performed with 0.5 μg total mRNA using the QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations and all samples were amplified in the GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA). The primer pairs were as follows: VEGF R2 (KDR) (forward): 5′-GGA CCT GGC GGC ACG AAA TA-3′; (reverse): AGG CCG GCT CTT TCG CTT AC-3′ (619 bp of PCR product size, GenBank accession no.: X61656) and β-actin (forward): 5′-CTA CAA TGA GCT GCG TGT GC-3′; (reverse): 5′-CGG TGA GGA TCT TCA TGA GG-3′ (314 bp of PCR product size, GenBank accession no.: XM004814).

For both VEGF R2 (KDR) and β-actin, the RT reactions were carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations in 1 cycle of 30 min at 50°C for reverse transcription and 15 min at 95°C for the initial PCR activation. For VEGF R2 (KDR) PCR, the cycling conditions were as follows: 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C for denaturation, 1 min at 60°C for annealing and 1 min at 72°C for extension. For β-actin, the protocol was almost the same as that described above, but with 25 cycles.

To evaluate the amount of PCR product, 10 μg of amplified products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel (SeaPlaque GTG Agarose, Cambrex Bio Science Rockland, Maine, USA), visualized using Ethidium bromide and photographed using Polaroid film under UV light.

Quantitative determination of IL-12 (p70 heterodimer) and IL-10

After DCs (im-DC, LPS-DC, OK-DC and co-DC) were washed using X-VIVO two times, each DC (1 × 105per ml) was cultured in 2 ml of X-VIVO with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) at 37°C for 24 h in a 6-well plate. After incubation, the culture supernatants in each DC was collected and tested for IL-12 or IL-10 contents using a human IL-12 (p70) or IL-10 Kit (Becton Dickinson Biosciences).

Apoptosis

After DCs (im-DC, LPS-DC, OK-DC and co-DC) were washed using X-VIVO two times, each DC (1 × 105/ml) was cultured in 2 ml of X-VIVO with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) at 37°C for 48 h in a 6-well plate. After incubation, apoptosis in each DC was measured by staining with FITC-conjugated annexin-V and PI using a MEBCYTO Apoptosis kit (MBL, Nagoya, Japan) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Quantitative determination of phosphorylated p38 MAP Kinase, Akt1, and Erk 1&2

LPS-DC, OK-DC or co-DC (1 × 105 ml) was cultured in 2 ml of X-VIVO with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) at 37°C for 15 min in a 6-well plate in the combination with anti-human blocking VEGF R2 mAb. After incubation, each well was gently washed two times using sterile PBS. DCs were collected and lysed with lysing solution provided in each ELISA kit. Total p38 MAP Kinase and phospho-p38 MAP Kinase were quantified with an ELISA kit purchased from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI). Total Akt, total Erk1&2 and phospho-Erk1&2 were quantified with an ELISA kits purchased from Sigma. Phospho-Akt1 was quantified with an ELISA kits purchased from R&D Systems.

Statistics

To evaluate statistical differences between the two groups, a non-paired Student’s t test was performed. Statistically significant differences were considered to be P values < 0.05.

Results

Phenotypical analysis of monocyte-derived human dendritic cells

The phenotypes of the DCs were analyzed by flow cytometry using a panel of DC markers. As compared with im-DC, mature DCs (LPS-, OK-432- or co-DC) showed a mature phenotype with the up-regulation of CD80, CD83, CD86, MHC classI/-II molecules (data not shown). There were no significant differences in the expression of maturation markers among LPS-, OK-432- or co-DC (data not shown).

VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs evaluated by allo-MLR

To evaluate the effect of VEGF on im-DC, LPS-DC, OK-DC and co-DC, we examined DCs with regards to phenotypical change, the production of IL-12 (p-70) and IL-10, induction of apoptosis and antigen-presenting function evaluated by allo-MLR.

As a result, VEGF treatment did not significantly affect the expression of CD80, CD83, DC86, MHC class I and MHC class II (data not shown). Furthermore, VEGF treatment did not alter the production of IL-12p70 or IL-10, significantly (data not shown). Since it was reported that the apoptosis of DCs was induced by tumor-derived factors [25], the induction of apoptosis was evaluated when treated with VEGF. As a result, exogenous treatment with VEGF did not increase the apoptosis of DCs (data not shown).

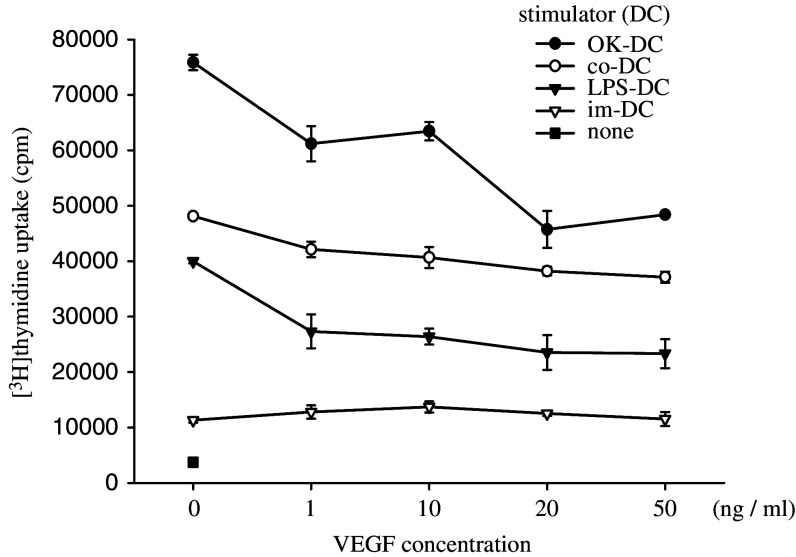

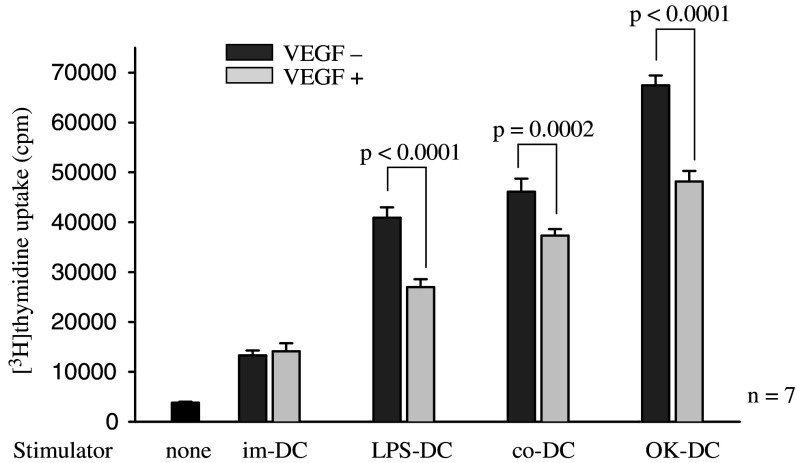

Of note, the abilities of mature-DCs (OK-DC, LPS-DC and co-DC) to stimulate allogeneic T cells were inhibited by the addition of VEGF in a dose-dependent manner, while the ability of im-DC to stimulate allogeneic lymphocytes was not inhibited by VEGF (Fig. 1). Summarized data from 7 different healthy donors confirmed that the ability of mature-DCs to stimulate allogeneic lymphocytes was inhibited by the addition of VEGF (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the VEGF-induced DC inability was observed at various DC to lymphocyte ratios (1:10, 1:50, 1:100) in OK-DC, LPS-DC and co-DC (data not shown). These results indicated that VEGF could inhibit the function of mature DCs presented by allo-MLR.

Fig. 1.

The abilities of mature-DCs to stimulate allogeneic T cells were inhibited by the addition of VEGF in a dose-dependent manner. DCs were cultured in 2 ml of X-VIVO with various doses of VEGF at 37°C for 24 h described in Materials and methods. After incubation, 1 × 105 allogeneic T cells were co-incubated with 2 × 103 irradiated (20 Gy) DCs in a 96-well U-bottom plate. After 96 h incubation, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well. The cells were cultured for 18 h and then thymidine incorporation was measured in counts per minute (cpm). Representative data from four independent experiments is shown. im-DC immature DCs, LPS-DC LPS-matured DCs, OK-DC OK432-matured DCs, co-DC, pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail-matured DCs

Fig. 2.

VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs evaluated by allo-MLR assay. DCs were cultured in 2 ml of X-VIVO with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) for 24 h described in Materials and methods. After the incubation, 1 × 105 allogeneic T cells were co-incubated with 2 × 103 irradiated (20 Gy) DCs in 96-well U-bottom plate. After 96 h incubation, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well. The cells were cultured for 18°h and then thymidine incorporation was measured in counts per minute (cpm). Summarized data from seven different donors were shown. Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t test. im-DC immature DCs, LPS-DC LPS-matured DCs, OK-DC OK432-matured DCs; co-DC pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail-matured DCs

Since the function of mature-DCs was apparently suppressed by the addition of 20 ng/ml of VEGF in vitro, we performed the following assay under this condition (VEGF concentration 20 ng/ml).

VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs through the VEGF receptor2 (KDR)

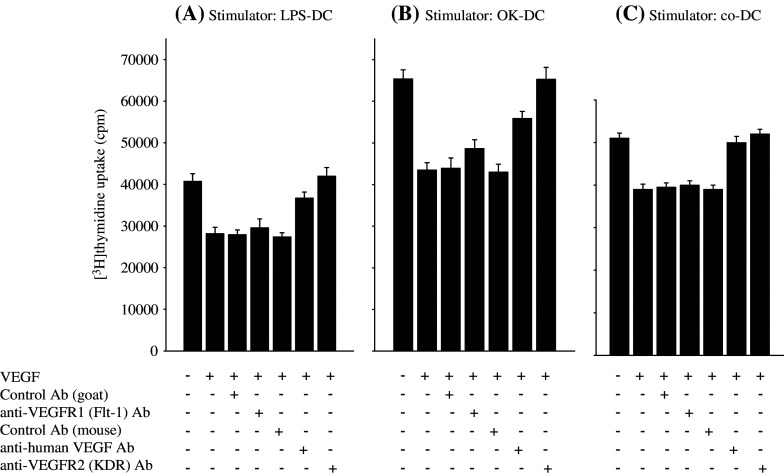

In order to confirm the VEGF-dependency of VEGF-induced deficiency of mature-DC function, the neutralizing anti-VEGF mAb was added to the allo-MLR assay. As expected, the VEGF-induced deficiency of mature-DCs to stimulate allogeneic T cells was recovered by the neutralizing anti-VEGF mAb (Fig. 3), confirmed in OK-, co- and LPS-DC (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs through the VEGF receptor2 (KDR). LPS-matured DCs (LPS-DC, a), OK432-matured DCs (OK-DC, b) and cytokine cocktail-matured DCs (co-DC, c) were cultured with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) in 2 ml of X-VIVO for 24 h in combination with anti-human neutralizing VEGF mAb (mouse IgG) (0.2 μg/ml), anti-human VEGF R1 blocking mAb (goat IgG) (10 μg/ml), anti-human VEGF R2 blocking mAb (mouse IgG) (50 ng/ml) or control Ab (mouse IgG1 isotype control or normal goat IgG control) as the negative control described in Materials and methods. After the incubation, 1 × 105 allogeneic T cells were co-incubated in triplicate with 2 × 103 irradiated (20 Gy) DCs in a 96-well U-bottom plate. After 96 h incubation, 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine was added to each well. The cells were cultured for 18 h and then thymidine incorporation was measured in counts per minute (cpm). Representative data from four independent experiments is shown

It has been shown that there are two functional receptors of VEGF [6, 12, 21, 37]. In order to block the VEGF receptor (VEGF R1 and VEGF R2), the blocking mAb for VEGF R1 (Flt-1) or VEGF R2 (Flk-1/KDR) were added to the allo-MLR assay. The VEGF-induced inability of OK-DC, co-DC and LPS-DC to stimulate allogeneic T cells was completely inhibited by the anti-VEGF R2 blocking mAb, in comparison to the control mAb, while the anti-VEGF R1 blocking mAb did not have any effect (Fig. 3). These results strongly suggest that VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs through the VEGF R2 (KDR).

In order to further confirm the VEGF R2 dependency, PlGF, which is a selective agonist for VEGF R1, was included in the allo-MLR assay. As expected, PlGF did not have any effect against mature DCs, including LPS-DC, co-DC and OK-DC (data not shown). Collectively, these results indicate that VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs through the VEGF R2 (KDR).

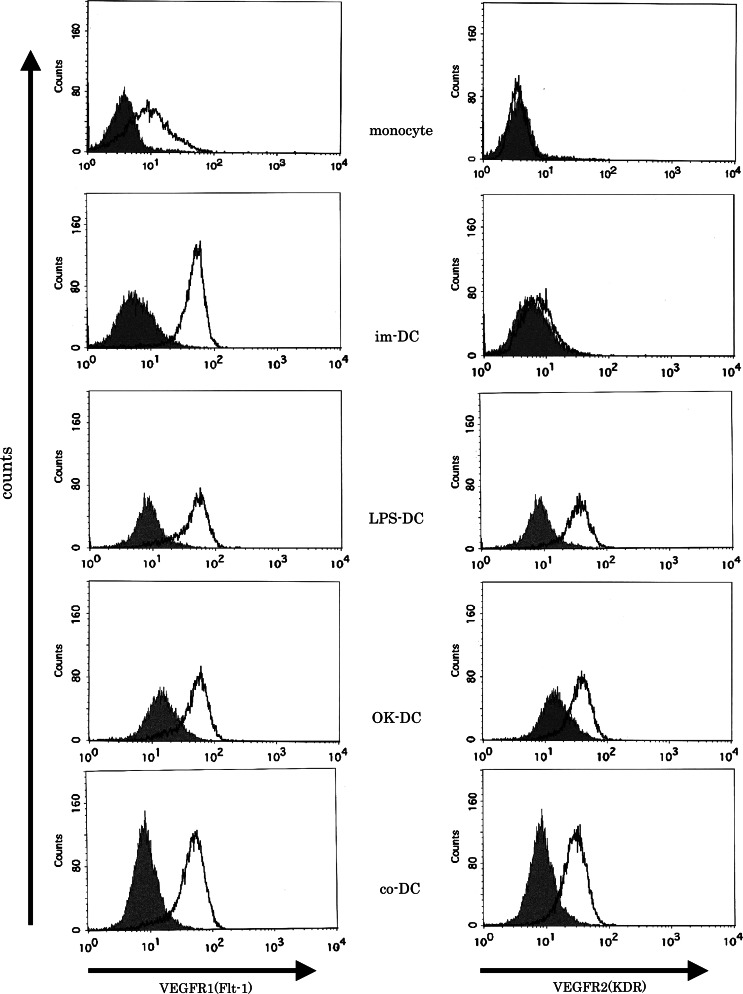

The expression of VEGF R1 (Flt-1) and VEGF R2 (Flk-1/KDR) on monocytes, im-DC and mature DCs

We investigated the expression of VEGF R1 and VEGF R2 on monocytes, im-DC and mature DCs using flow cytometry. VEGF R1 was consistently expressed on monocytes, im-DC and mature DCs at various levels, while VEGF R2 was only expressed on mature-DCs, but not on monocytes and im-DC (Fig. 4), in line with previous reports [6, 7, 11, 32, 36–38].

Fig. 4.

The expression of VEGF R1 and VEGF R2 on monocytes, immature DCs and mature DCs. The expression of VEGF R1 and VEGF R2 on monocytes, immature DCs and mature DCs were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative data from five independent experiments is shown. im-DC immature DCs, LPS-DC LPS-matured DCs; OK-DC OK432-matured DCs; co-DC pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail-matured DCs

Since the VEGF-induced functional deficiency of mature DCs was mediated by VEGF R2, the expression of VEGF R2 mRNA was further analyzed with semi-quantitative RT-PCR. VEGF R2 mRNA was faintly expressed on monocytes and im-DC, while VEGF R2 mRNA was abundantly expressed on LPS-, OK- and co-DC (data not shown).

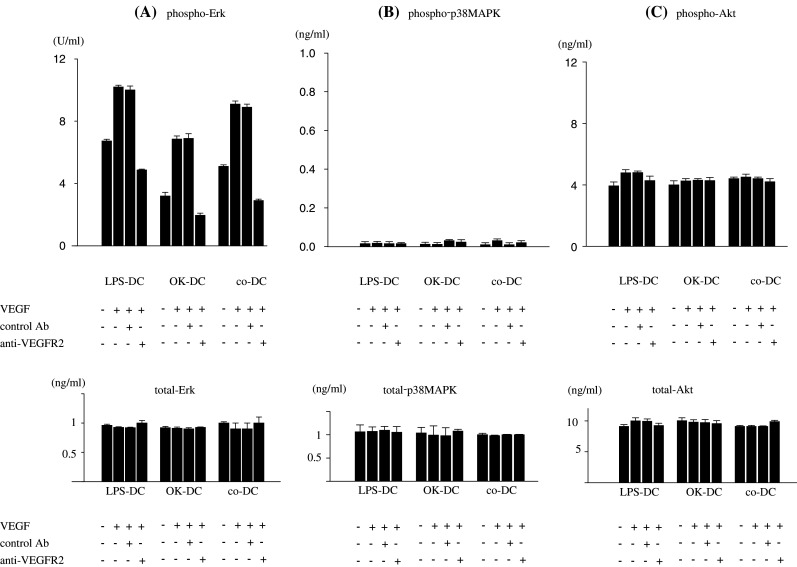

VEGF signal phosphorylated the extracelluar signal regulated kinase (Erk) 1&2 in mature-DCs through the VEGF receptor2 (KDR)

In order to further confirm the VEGF-induced deficiency of mature DCs, the intracellular signaling of DCs induced by VEGF was investigated. It is well known that the binding of VEGF to VEGF R1 or R2 induces the activation of the Erk, p38MAPK and Akt signaling pathway [21, 26]. In the present study, VEGF treatment enhanced the phospho-Erk 1&2 in LPS-, co- and OK-DC (Fig. 5a), while phospho-p38MAPK and -Akt were not induced by VEGF (Fig. 5b and c). The total levels of Erk, p38MAPK and Akt were not altered in any treatment protocol (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Intracellular signaling pathway of VEGF signaling on mature DCs. LPS-matured DCs (LPS-DC), OK432-matured DCs (OK-DC) or pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail-matured DCs (co-DC) were cultured in 2 ml of X-VIVO with or without VEGF (20 ng/ml) at 37°C for 15 min in the combination with anti-human VEGF R2 blocking mAb (mouse IgG) (50 ng/ml) or control Ab (mouse IgG1 isotype control) as a negative control described in Materials and methods. After the incubation, treated mature-DCs were collected and lysed with the lysing solution. The concentration of phospho-Erk and total-Erk (a), phospho-p38 MAPK and total-p38MAPK (b), phospho-Akt and total-Akt (c) were quantified by ELISA. Representative data from three independent experiments is shown

Importantly, the VEGF-induced phosphorylation of Erk 1&2 was inhibited by the anti-VEGF R2 blocking mAb (Fig. 5). These results further support that the VEGF-induced functional deficiency of mature DCs was mainly mediated by VEGF R2.

Discussion

The present study contains several important findings relevant to the effect of VEGF against human mature DCs. First, mature DCs expressed the VEGF R1 (Flt-1) and VEGF R2 (KDR) receptors. Second, VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs evaluated by allo-MLR, and this inhibition was mainly mediated by VEGF R2.

DCs are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and play a central role in the host’s antitumor immunity. The defective function of DCs in cancer-bearing hosts has been reported by many groups [4, 5, 17, 18]. Furthermore, it has been reported that VEGF inhibits the functional maturation of immature-DCs [10, 15, 16, 19, 23, 32] and impairs DC differentiation [1, 16, 20, 31]. Thus, it is important to elucidate the mechanisms of VEGF-induced DC-dysfunction, in order to enhance the antitumor immunity in cancer-bearing hosts.

In the present study, DCs were generated from peripheral blood monocytes and matured with LPS, OK-432 or a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail, as it was reported that im-DC are matured by a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail [9, 22, 39, 40], LPS [34, 38, 39] and OK-432 [13, 29], which is a penicillin-killed and lyophilized preparation of a low-virulence strain of Streptococcus pyogenes [13]. We confirmed that LPS-DC, OK-DC and co-DC showed a mature-DC phenotype, including the up-regulation of co-stimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86), MHC classI/-II and CD83 (maturation marker), in line with previous reports [22, 29, 38].

With regard to the VEGF receptor, VEGF binding sites were initially identified on the vascular endothelial cells and shown to also exist on monocytes [12], which are two different receptors, VEGF R1 (Flt-1) and VEGF R2 (KDR) [6, 12, 21, 37]. It has been reported that VEGF R1 was expressed on monocytes, im-DC and mature DCs [6, 7, 11, 32, 36, 37], while VEGF R2 was expressed on DCs, but not on monocytes [7, 11, 38]. In the present study, we showed that VEGF R1 was expressed on monocytes, im-DC and mature-DCs, while VEGF R2 was abundantly expressed on mature-DCs, but faintly expressed on monocytes and im-DC at both protein and mRNA levels.

Carbone et al. showed that VEGF R1 is the major mediator of VEGF effects on the NF-κB pathway in hemopoietic stem cells and that VEGF affects the early stage of myeloid/DC differentiation [1, 10, 15, 16, 23, 30–32]. Also, Clauss et al. showed that VEGF R1 is biologically active in monocytes / macrophages and VEGF stimulates the migration and chemotaxis of human monocytes [6, 7, 37]. On the other hand, it was reported that VEGF R2 is the major mediator of the mitogenic and angiogenic signal, but VEGF R1 does not mediate an effective mitogenic signal of VEGF in endothelial cells [12]. However, little is known about the effect of VEGF on mature-DCs, in particular, how VEGF utilizes the VEGF receptor on mature DCs. To investigate the effects of VEGF against human mature DCs, we investigated how VEGF affects mature DCs with regards to phenotype, the induction of apoptosis, IL-12(p70) production and the antigen-presenting function evaluated by allo-MLR. As a novel and important finding, VEGF inhibited the ability of mature-DCs to stimulate allogeneic T cells. Furthermore, this VEGF-induced DC dysfunction was mainly mediated by VEGF R2. These observations were confirmed by the findings that the VEGF-induced DC dysfunction was recovered by anti-human VEGF neutralizing mAb or anti-human VEGF R2 blocking mAb, and PlGF, VEGF R1-specific ligand, did not have any effect against mature DCs. It has been shown that VEGF R1 is the major mediator that VEGF affects the early stage of myeloid/DC differentiation [10]. The present study showed additional information that VEGF inhibit the function of mature DC through VEGF R2, when DC has the abundant expression of VEGF R2 with maturation stimuli.

The mechanism behind the fact that VEGF inhibits the T cell stimulatory activity of mature DC remains unclear. In the present study, there were no significant changes of DC with regards to phenotype, induction of apoptosis or the production of IL-12 and IL-10 after treatment with VEGF. Since NF-κB plays a pivotal role in DC function, it is possible that NF-κB activity may be involved in the VEGF-induced DC dysfunction described here. Further study will be needed to clarify which molecules could be responsible for the VEGF-induced DC dysfunction.

It has been shown that VEGF signaling is transduced via several intracellular signaling pathways, including Erk, p38MAPK or Akt, leading to increased cell proliferation, survival, permeability and migration of endothelial cells [12, 21, 34]. Furthermore, it was reported that VEGF R2 activation by VEGF induces the activation of the Erk pathways, PI3 kinase/Akt pathways and p38MAPK pathways [12, 21]. Erk has two closely related isoforms, in which Erk 1 is known as MAP (Mitogen-Activated Protein) kinase 1 or p44 MAP kinase, and Erk 2 is known as MAP kinase 2 or p42 MAP kinase. Erk activation is essential for cell proliferation and has been linked to the regulation of differentiation as well as regulation of the cytoskeleton, and provides an integrated response by activating gene transcriptions [33]. Interestingly, it has been shown that the Erk 1&2 signaling pathway negatively regulates the maturation of human monocyte-derived im-DC [34]. In the present study, we evaluated the intracellular signaling pathways involved in VEGF-mediated signal induction in mature-DCs by ELISA. We observed that VEGF enhanced the phosphorylation of Erk 1&2, but not those of p38MAPK and Akt in mature-DCs. Moreover, the VEGF-induced phosphorylation of Erk 1&2 was inhibited by anti-human VEGF R2 blocking mAb. These results further supported that VEGF-signaling in human monocyte-derived mature-DCs interacts with VEGF R2 and is transduced intracellularly. It seems that the Erk 1&2 signaling pathway negatively regulates the function of human monocyte-derived mature-DCs as well as the maturation of im-DC [34, 38, 39].

When immunotherapy using mature DCs against cancer patients is considered, the VEGF-mediated inhibitory effect of mature DCs, described here, is the crucial point to be resolved, since VEGF is known to be produced in most cancer cells. Therefore, blockade of VEGF signaling using a humanized anti-VEGF mAb (AvastinR), which has been approved for therapeutic use with a proven survival benefit in patients with metastatic colon cancers, an anti-human VEGF R2 mAb or small molecule inhibiting VEGF R2 signal transduction [12] may improve the VEGF-induced DC-dysfunction in cancer-bearing hosts, in addition to the anti-angiogenetic effect against the tumor-microenvironment.

In conclusion, VEGF inhibits the function of mature-DCs evaluated by allo-MLR and this inhibition was mainly mediated with VEGF receptor-2.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in Japan.

References

- 1.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166:678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almand B, Resser JR, Lindman B, Nadaf S, Clark JI, Kwon ED, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Clinical significance of defective dendritic cell differentiation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1755–1766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambe K, Mori M, Enjoji M. S-100 protein-positive dendritic cells in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Distribution and relation to the clinical prognosis. Cancer. 1989;63:496–503. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890201)63:3<496::AID-CNCR2820630318>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaux P, Favre N, Martin M, Martin F. Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells are defective in their antigen-presenting function and inducible B7 expression in rats. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:619–624. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970807)72:4<619::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaux P, Moutet M, Faivre J, Martin F, Martin M. Inflammatory cells infiltrating human colorectal carcinomas express HLA class II but not B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules of the T-cell activation. Lab Invest. 1996;74:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clauss M. Functions of the VEGF receptor-1 (FLT-1) in the vasculature. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1998;8:241–245. doi: 10.1016/S1050-1738(98)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clauss M, Weich H, Breier G, Knies U, Rockl W, Waltenberger J, Risau W. The vascular endothelial growth factor receptor Flt-1 mediates biological activities. Implications for a functional role of placenta growth factor in monocyte activation and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17629–17634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connolly DT, Heuvelman DM, Nelson R, Olander JV, Eppley BL, Delfino JJ, Siegel NR, Leimgruber RM, Feder J. Tumor vascular permeability factor stimulates endothelial cell growth and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1470–1478. doi: 10.1172/JCI114322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhodapkar KM, Krasovsky J, Williamson B, Dhodapkar MV. Antitumor monoclonal antibodies enhance cross-presentation ofcCellular antigens and the generation of myeloma-specific killer T cells by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:125–133. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dikov MM, Ohm JE, Ray N, Tchekneva EE, Burlison J, Moghanaki D, Nadaf S, Carbone DP. Differential roles of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1 and 2 in dendritic cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2005;174:215–222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez Pujol B, Lucibello FC, Zuzarte M, Lutjens P, Muller R, Havemann K. Dendritic cells derived from peripheral monocytes express endothelial markers and in the presence of angiogenic growth factors differentiate into endothelial-like cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2001;80:99–110. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujimoto T, Duda RB, Szilvasi A, Chen X, Mai M, O’Donnell MA. Streptococcal preparation OK-432 is a potent inducer of IL-12 and a T helper cell 1 dominant state. J Immunol. 1997;158:5619–5626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukawa T, Watanabe S, Kodama T, Sato Y, Shimosato Y, Suemasu K. T-zone histiocytes in adenocarcinoma of the lung in relation to postoperative prognosis. Cancer. 1985;56:2651–2656. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851201)56:11<2651::AID-CNCR2820561120>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabrilovich D, Ishida T, Oyama T, Ran S, Kravtsov V, Nadaf S, Carbone DP. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits the development of dendritic cells and dramatically affects the differentiation of multiple hematopoietic lineages in vivo. Blood. 1998;92:4150–4166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, Cunningham HT, Meny GM, Nadaf S, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabrilovich DI, Ciernik IF, Carbone DP. Dendritic cells in antitumor immune responses. I. Defective antigen presentation in tumor-bearing hosts. Cell Immunol. 1996;170:101–110. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrilovich DI, Corak J, Ciernik IF, Kavanaugh D, Carbone DP. Decreased antigen presentation by dendritic cells in patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gabrilovich DI, Nadaf S, Corak J, Berzofsky JA, Carbone DP. Dendritic cells in antitumor immune responses. II. Dendritic cells grown from bone marrow precursors, but not mature DC from tumor-bearing mice, are effective antigen carriers in the therapy of established tumors. Cell Immunol. 1996;170:111–119. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrilovich DI, Velders MP, Sotomayor EM, Kast WM. Mechanism of immune dysfunction in cancer mediated by immature Gr-1+ myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5398–5406. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, De Bruijn EA. Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:549–580. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann TK, Meidenbauer N, Muller-Berghaus J, Storkus WJ, Whiteside TL. Proinflammatory cytokines and CD40 ligand enhance cross-presentation and cross-priming capability of human dendritic cells internalizing apoptotic cancer cells. J Immunother. 2001;24:162–171. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishida T, Oyama T, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Defective function of Langerhans cells in tumor-bearing animals is the result of defective maturation from hemopoietic progenitors. J Immunol. 1998;161:4842–4851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaya M, Wada T, Akatsuka T, Kawaguchi S, Nagoya S, Shindoh M, Higashino F, Mezawa F, Okada F, Ishii S. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in untreated osteosarcoma is predictive of pulmonary metastasis and poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:572–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiertscher SM, Luo J, Dubinett SM, Roth MD. Tumors promote altered maturation and early apoptosis of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:1269–1276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo X, Liu L, Tang N, Lu KQ, McCormick TS, Kang K, Cooper KD. Inhibition of monocyte-derived dendritic cell differentiation and interleukin-12 production by complement iC3b via a mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway. Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuda H, Mori M, Tsujitani S, Ohno S, Kuwano H, Sugimachi K. Immunohistochemical evaluation of squamous cell carcinoma antigen and S-100 protein-positive cells in human malignant esophageal tissues. Cancer. 1990;65:2261–2265. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900515)65:10<2261::AID-CNCR2820651017>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyake M, Taki T, Hitomi S, Hakomori S. Correlation of expression of H/Le(y)/Le(b) antigens with survival in patients with carcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:14–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199207023270103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakahara S, Tsunoda T, Baba T, Asabe S, Tahara H. Dendritic cells stimulated with a bacterial product, OK-432, efficiently induce cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific to tumor rejection peptide. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4112–4118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohm JE, Carbone DP. VEGF as a mediator of tumor-associated immunodeficiency. Immunol Res. 2001;23:263–272. doi: 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohm JE, Gabrilovich DI, Sempowski GD, Kisseleva E, Parman KS, Nadaf S, Carbone DP. VEGF inhibits T-cell development and may contribute to tumor-induced immune suppression. Blood. 2003;101:4878–4886. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oyama T, Ran S, Ishida T, Nadaf S, Kerr L, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Vascular endothelial growth factor affects dendritic cell maturation through the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activation in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1224–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pouyssegur J, Volmat V, Lenormand P. Fidelity and spatio-temporal control in MAP kinase (ERKs) signalling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:755–763. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(02)01135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puig-Kroger A, Relloso M, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Zubiaga A, Silva A, Bernabeu C, Corbi AL. Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase signaling pathway negatively regulates the phenotypic and functional maturation of monocyte-derived human dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;98:2175–2182. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.7.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito H, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M, Maeta M, Kaibara N. Relationship between the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and the density of dendritic cells in gastric adenocarcinoma tissue. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1573–1577. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawano A, Iwai S, Sakurai Y, Ito M, Shitara K, Nakahata T, Shibuya M. Flt-1, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1, is a novel cell surface marker for the lineage of monocyte-macrophages in humans. Blood. 2001;97:785–791. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shibuya M. Structure and dual function of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (Flt-1) Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33:409–420. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi A, Kono K, Ichihara F, Sugai H, Fujii H, Matsumoto Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibits maturation of dendritic cells induced by lipopolysaccharide, but not by proinflammatory cytokines. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0466-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waeckerle-Men Y, Scandella E, Uetz-Von Allmen E, Ludewig B, Gillessen S, Merkle HP, Gander B, Groettrup M. Phenotype and functional analysis of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells loaded with biodegradable poly(lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres for immunotherapy. J Immunol Methods. 2004;287:109–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou LJ, Tedder TF. CD14+ blood monocytes can differentiate into functionally mature CD83+ dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2588–2592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]