Abstract

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules have been considered as a good target molecule for use in immunotherapy, because of the high expression in some lymphoma and leukaemia cells and, also, because of their restricted expression on human cells (monocytes, dendritic, B lymphocytes, thymic epithelial cells, and some cytokine-activated cells, such as T lymphocytes). We have obtained a human IgM monoclonal antibody directed against human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II molecules, using transgenic mice carrying human Ig genes. The antibody BH1 (IgM/κ isotype) recognises HLA-class II on the surface of tumour cells from patients suffering from haematological malignancies, such as chronic and acute lymphocytic leukaemias, non-Hodgkin lymphomas and myeloid leukaemias. Interestingly, functional studies revealed that BH1 mAb recognises and kills very efficiently tumour cells from several leukaemia patients in the presence of human serum as a source of complement. These results suggest that this human IgM monoclonal antibody against HLA-class II could be considered as a potential agent in the treatment of several malignancies.

Keywords: HLA class II, Human monoclonal antibodies, Immunotherapy, Leukaemia

Introduction

Although murine mAbs are relatively easy to produce [19], and some chimeric mouse–human or humanized mouse–human anti-human mAbs are now available [1, 5], there are severe restrictions on their therapeutic use in humans, due to their immunogenicity [9, 13] and the resulting reduction in their efficacy and safety. These limitations could be overcome by the use of fully human mAbs [4, 29, 37], which would allow their repeated administration without immunogenic and/or allergic response. The development of transgenic mouse strains, engineered with unrearranged human Ig genes, appears to be a good solution for the generation of specific human mAbs [8, 21, 28].

The human class II molecules (DR, DP, DQ) of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in humans are, under normal conditions, selectively expressed on immune cells, including B lymphocytes, activated T lymphocytes, monocytes and dendritic cells. Moreover, the class II molecules of the human leukocyte antigen system (HLA) are expressed on many human B and myeloid leukaemias, as well as on B cell lymphomas, at high surface densities [23].

Recently, some murine anti-HLA class II mAbs have been modified by molecular biology techniques to develop either humanized or chimeric antibodies. Thus, Hu1D10 (humanized) and CHLym-1 (chimeric human–mouse) mAbs antibodies are currently being evaluated for the treatment of human B cell lymphomas, although the clinical application of antibodies could still be restricted by their potential immunogenicity in humans. Indeed, it has been shown that Hu1D10 could cause severe type-1 hypersensitivity reactions and clinical symptoms including increased heart rate, dyspnoea, vomiting and urticaria [33]. More recently, two fully human anti-HLA class II antibodies termed 1D09C3 [26] and HD8 [35] have been generated by the screening of a human combinatorial antibody library, and by the use of a transchromosome mouse that bears human immunoglobulin genes, respectively. Both antibodies have an intrinsic tumoricidal activity in vitro in cell lines, therefore they are promising immunotherapeutic agents.

Here, we report the generation of a new human monoclonal antibody called BH1. This human mAb, a human IgM/κ, was obtained from a transgenic BAB κ, λ mouse that carries human transgenes for μ heavy, and κ and λ light chains, in an inactivated endogenous IgH and Igκ background [2, 28]. This mAb specifically recognises human HLA-class II molecules on the surface of human monocytes, B lymphocytes, tumour B cell lines (Hmy, Raji and Daudi) and tumour cells from patients suffering from haematological malignancies. It is demonstrated that BH1 shows tumoricidal effect on human leukaemia cells from patients suffering from several disorders, killing those cells in the presence of complement. Competitive assays using BH1 and other anti-HLA class II mAbs (Q2/70 and CHLym-1) indicate that both BH1 and Q2/70 mAbs recognise the same HLA class II antigenic epitope, not shared by the chimeric CHLym-1 mAb.

Although most of the mAbs being used as therapeutic agents in haematological malignancies are of IgG isotype [1, 11, 18], the value of IgM mAbs in human therapy should also be considered, due to their high efficacy in complement activation and lower level of entry into normal tissues. The results of this study support the development of a promising potential therapeutic use for human IgM mAbs, and BH1 can be a suitable in vivo candidate in antibody therapy for the removal or possible eradication of tumour cells.

Materials and methods

Experiments reported here were approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Vigo and the Xunta de Galicia (Spain), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Transgenic mice

BAB κ, λ mice [22, 28] were provided by Dr Marianne Brüggeman (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, England) and maintained under filtered air in-flow cabinets and fed with irradiated food and autoclaved water at the Animal Facility of the University of Vigo.

Cell lines

The human tumour cell lines used in this study were: Hmy, Raji and Daudi (HLA class II positive B cell lines, [12, 15, 31]), Jurkat (T cell line); U937 (histiocytic lymphoma cell line); K562 (erythroleukaemia); RPMI 8266; MM1R and M144 (myeloma cells), PC3 (prostate carcinoma); Colo205 (colon carcinoma); MCF7 (breast carcinoma); and ME180 (cervical carcinoma). All cells were cultured in DMEM or RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, Scotland) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated foetal calf serum (FCS) (PAA, Linz, Austria), penicillin (100 U/mL) and glutamine (2 mM) (Gibco) at 37 C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Human cell samples

Heparinized whole blood from healthy donors was used for the analysis of several blood cell populations (lymphocytes, granulocytes, erythrocytes, monocytes and platelets). Blood was diluted with PBS 1×, and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (huPBMC) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-PaqueTM solution (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). In activation assays, huPBMC were activated for 48 h in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL of PHA (lectin from Phaseolus vulgaris) (Sigma). For the analysis of granulocytes, distillated water was added to whole blood to eliminate erythrocytes. Platelets were obtained by centrifugation of diluted blood at 40g for 5 min, and supernatant was collected. Erythrocytes were obtained by centrifugation of diluted blood at 231g for 5 min, and cellular pellet was obtained. The Immunology and Haematology Units of the Hospital Meixoeiro of Vigo provided peripheral blood and/or bone marrow from leukaemia patients. Bone marrow cells were obtained by aspiration for diagnostic purposes, and mononuclear cells were isolated as described above. Cellular suspensions were also obtained from tumour lymph nodes (lymphomas), or from normal lymph nodes from patients without tumour pathology, who were undergoing surgery.

Immunization, cell fusion and screening

Transgenic mice were immunized twice (3 weeks interval) with 5–10 × 106 viable Hmy cells by intraperitoneal injection in the presence of complete and incomplete Freund Adjuvant (CFA, Gibco Laboratories, Detroit, Michigan, USA), respectively. Mouse sera were tested 2 weeks later for the production of human IgM antibodies by ELISA and by indirect immunofluorescence (see below). Three or five days before fusion, mice were intravenously boosted with 5 × 106 viable Hmy cells. The spleen was removed and splenocytes were fused to NSO mouse myeloma cells using PEG 1500 (Sigma). The hybridomas generated were screened for secretion of HuIgM antibody by ELISA [22] or by flow cytometry against target cells.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out using different target cells. The 3 × 105 cells were incubated at 4 C for 30 min with medium alone, neat or concentrated hybridoma supernatants and washed twice with PBS. Cells were stained with FITC-rabbit anti-HuIgM Abs (Dako) at 4 C for 20 min. The stained cells were washed twice with PBS and the cellular fluorescence was measured using a XL-MCL Flow Cytometer (Coulter Electronic, Hialeah, FL). The isotype of the secreted BH1 mAb was determined using FITC-rabbit anti-human λ, anti-human κ light chain (Dako) or FITC goat anti-mouse λ light chain (Caltag, Burlingame, CA) For two-colour staining studies, cells were incubated with PE or FITC-conjugated mouse anti-HLA-DR mAb (Immunotech, Beckman Culter, Inc. Fullerton, CA, USA), washed twice with PBS and incubated with BH1 followed by FITC or PE-rabbit anti-HuIgM Ab as second stage reagent, respectively. In some cases, cells were also studied using a mouse anti-HLA class II Q2/70 mAb (kindly provided by Dr Charo de Pablo, Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Madrid) [32], and human BH1 mAb, followed by incubation with the corresponding PE, FITC- anti-mouse Igs or anti-human IgM, respectively. The analysis of different cell populations was undertaken using forward and size scatter with the mAbs directed against the specific surface markers CD7, CD20, CD14, CD13, CD41 (Immunotech, Beckman Culter, CA) for T and B cells, monocytes, granulocytes, and platelets, respectively, and Ery-1 (CBG, Spain) for erythrocytes. A human IgM mAb (hAIM-29) against human CD69 molecule [24] was used as isotype control.

Competitive assay

A competitive cell binding assay was carried out to assess the reactivity and specificity of BH1 against HLA class II molecules. Raji and Hmy cells were incubated with a constant amount of BH1 (60 ng) and varying quantities of supernatants containing mouse Q2/70 [32] or chimeric mouse–human IgG CHLym-1 [17] (kindly provided by Dr Charo de Pablo and Dr Alan Epstein, respectively), at 4 C for 45 min. After washing, cells were incubated with FITC or PE-rabbit anti-HuIgM Abs as second-stage reagents. Cell staining was analysed using a XL-MCL Flow Cytometer.

Western blot analysis and immunoprecipitation

In 1 mL of lysis buffer (250 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA pH 8.0 and 0.1–1% NP-40), 107 cells were incubated at 4 C for 30 min, in the presence of protease inhibitors (Complete-mini, Roche Diagnostics, USA). Samples were cleared by centrifugation at 11g for 10 min. The amount of protein in the supernatants was measured by the Bradford Colorimetric method. For immunoblots, 10 μg of lysates were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred using a Trans-blot Semi-dry (BioRad Laboratories, Cambridge, MA) onto PVDF membrane (Hybond-P, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, England). The membranes were incubated with neat or concentrated hybridoma supernatant containing BH1 mAb, followed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase rabbit anti-human IgM Abs (Dako). 5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate dipotassium/nitrotetrazolium blue chloride (BCIP/NBT, Sigma) was used as substrate to visualise specific protein. For immunoprecipitation, the mouse anti-HLA-class II Q2/70 mAb was coupled to Protein G (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein G-Q2/70 was incubated with Hmy and Jurkat lysates, washed several times and the resulting samples were applied on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membrane and incubated with BH1 as described above.

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) assay

The ability of BH1 to kill different cells was determined by CDC assay and analysed by flow cytometry. Leukaemia cells from patients were incubated for 30 min at 4 C with medium alone (as negative control), BA5 as isotype control (a human IgM mAb produced in our laboratory that recognises B cells isolated from normal huPBMC and some tumoral B cells) [22, 34], BH1, or with anti-HLA-class II CHLym-1 and Q2/70 mAbs. Cells were washed twice and incubated at 37 C for 30 min with rabbit complement (diluted 1:2 in medium) (Dade Behring, Marhurg, Germany), human complement (Sigma), or with human serum as a source of complement. Cell viability was tested by adding propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma) and death cells were analysed by flow cytometry for PI staining.

Results

A human monoclonal antibody (BH1) recognises HLA class II molecules

We have previously shown that high affinity human mAbs directed against human antigens can be obtained from transgenic BABκ and BABκ,λ mice [22, 24, 34]. Transgenic BABκ,λ mice were immunized with human tumour B cells in order to obtain monoclonal antibodies directed against human B cells, which could be used in human therapy against B cell leukaemias. Spleen cells from transgenic mice were fused efficiently with the NSO myeloma cells, allowing the isolation of hybridomas secreting specific human IgM (HuIgM) directed against B cells. One of these hybridomas, which secretes BH1, a human monoclonal IgM/κ, was used to perform additional studies.

The human mAb BH1 specifically recognises human B lymphocytes and monocytes (Table 1), but not T cells, granulocytes, erythrocytes or platelets from peripheral blood. In addition, it does not stain normal bone marrow cells or T cells from non-tumour lymphoid nodes (Table 1). Moreover, BH1 only stained the B cell lines Hmy, Daudi and Raji. Other tumour cells tested of different origin (Jurkat, U937, K562, RPMI 8266, MM1R, M144, PC3, Colo205, MCF7 and ME180) were not recognised by the BH1 mAb (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recognition of normal and tumour human cells by human BH1 mAb

| Tumour cell lines | %a | Δ MFIb | Normal cells | %a | Δ MFIb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haematopoietic | Peripheral blood | ||||

| HMY | 98.6 ± 1.5 | 831.1 ± 43.4 | Lymphocytes B | 97.4 ± 0.1 | 75.9 ± 8.7 |

| DAUDI | 97.2 ± 2.4 | 67.5 ± 1.5 | Lymphocytes T | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 1.1 |

| RAJI | 99.9 ± 0.7 | 501.4 ± 9.4 | Monocytes | 88.4 ± 3.5 | 39.3 ± 6.1 |

| JURKAT | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 2.7 | Granulocytes | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 0.1 ± 0.2 |

| U937 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 2.8 | Erytrocytes | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| K562 | 1.9 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 0.6 | Platelets | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| RPMI8266 | 18.7 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 0.3 | |||

| MM1R | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | |||

| M144 | 17.1 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | |||

| (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 4) | (n = 4) | ||

| Non-haematopoietic | Lymph nodes c | ||||

| PC3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | Lymphocytes B | 92.6 ± 5.5 | 86.2 ± 6.9 |

| Colo205 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | Lymphocytes T | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.7 |

| MCF7 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | |||

| ME180 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | (n = 3) | (n = 3) | |

| Bone marrow mononuclear cells c | 6.6 ± 5.3 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | |||

| (n = 3) | (n = 3) | (n = 10) | (n = 10) | ||

aPercentage (%) of cells recognised by BH1. The results are expressed as Mean ± sd obtained from n independent experiments

bMean fluorescence intensity (ΔMFI) calculated as: MFI(BH1 + secondary antibody) − MFI(secondary antibody). It is expressed as the Mean ± SD obtained from n independent experiments

cNon-tumour samples obtained from lymph nodes or bone marrow

Several methods were used to characterise the antigen recognised by BH1. First, we analysed whether it could be expressed on human PHA-activated PBMC. The analysis of the staining showed that the antigen recognised by BH1 mAb was expressed in human CD7+ lymphocytes only after activation (Fig. 1a), indicating that it recognises a marker expressed on activated T lymphocytes. As a positive control of cell activation, the staining of HLA class II with a commercial anti-HLA-DR mAb and Q2/70, a different mouse anti-HLA class II mAb, were also included, and interestingly, the staining showed a linear pattern in both cases, which strongly suggests a co-recognition by both monoclonal antibodies (BH1 and anti-HLA class II) of the same molecule (Fig. 1a). The same double immunofluorescence analysis was carried out on Hmy, a HLA class II positive B cell line (Fig. 1b), and a perfect correlation in the staining with both Abs was also observed. In contrast, the anti-CD20 mAb, which also recognises Hmy cells, did not show a pattern of co-staining with the commercial anti-HLA-DR mAb (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Two-colour staining using PHA-activated PBMC as target cells (a) or the Hmy cell line (b). Cells were incubated with directly conjugated (PE or FITC) anti-HLA-DR, anti-CD7, and anti-CD20 mAbs, and with mouse Q2/70 or BH1 mAbs (followed by FITC-rabbit anti-mouse IgG and PE-rabbit anti-human IgM antibodies, respectively)

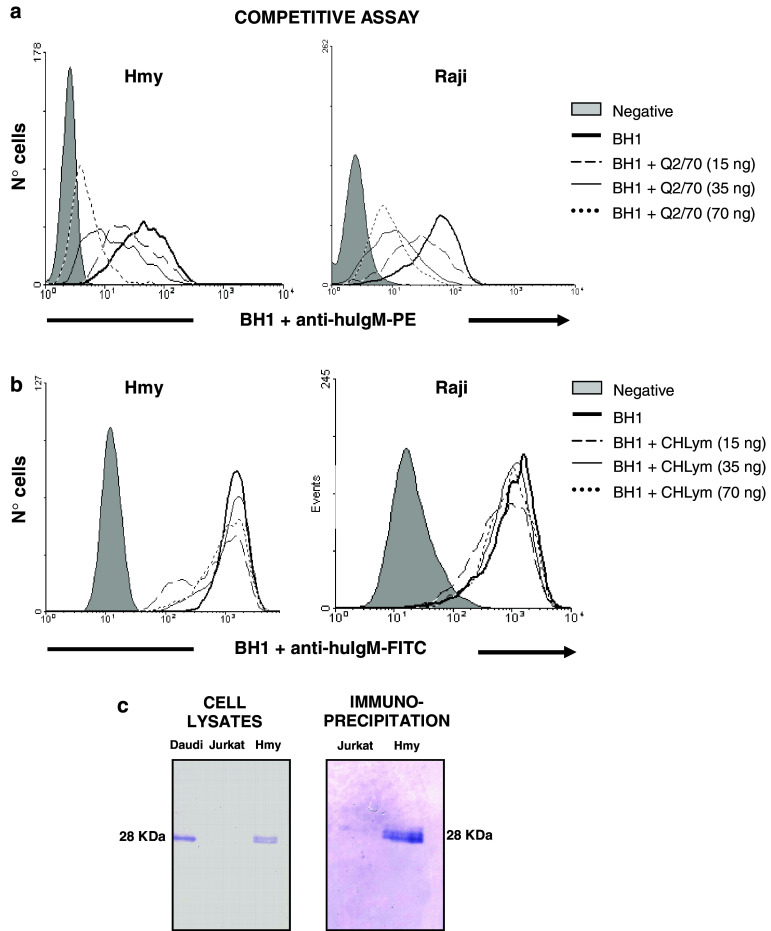

The confirmation that BH1 recognises HLA class II molecules was undertaken by a competitive binding assay using BH1 and other anti-HLA-class II molecules mAbs. Hmy or Raji cells were incubated in the presence of a constant amount of BH1 and varying amounts of Q2/70 or CHLym-1. As shown in Fig. 2a, while Q2/70 competes with BH1, this does not happen for CHLym-1 (Fig. 2b). Increasing amounts of Q2/70 decrease the staining of cells to the BH1 mAb, indicating that both antibodies recognise the same antigenic epitope.

Fig. 2.

Competitive assay. Hmy and Raji cells were incubated with a low amount of BH1 mAb and increasing quantities of mouse Q2/70 (a) or chimeric CHLym-1 mAbs (b). BH1 mAb was detected with PE or FITC conjugated anti-human IgM Abs. c BH1 mAb recognises a protein of 28 KDa on Hmy and Daudi lysates (both B cell lines), but not on Jurkat (T cell line) in Western blot analysis (left blot). Immunoprecipitation of HLA- class II antigen using the protein G-Q2/70 mAb, stained with BH1 mAb followed by alkaline phosphatase rabbit anti-human IgM Abs (right blot)

Furthermore, Western blot analysis of cell lysates showed that BH1 binds a protein of 28 KDa, which corresponds to the expected molecular weight for the HLA class II-beta chain, on Hmy and Daudi (both B cell lines), but not on Jurkat cells (Fig. 2c). BH1 was able to stain the same band when the HLA class II antigen was immunoprecipitated with Protein G-Q2/70 mAb (Fig. 2c). All these results confirm that BH1 recognises HLA class II antigen.

BH1 mAb recognises and kills cells of human haematological disorders

Malignant cells from the peripheral blood, bone marrow or lymph nodes of 80 patients suffering from different haematological malignancies were tested to demonstrate the specificity of BH1 against malignant cells. Table 2 shows the summary of the patients analysed and the level of recognition of BH1 to tumour cells. Over 86% of the chronic lymphocytic leukaemias (CLL), 30 out of 35, were recognised by the mAb BH1. Tumour cells from four patients included in the study with acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL) were also stained. Moreover, 60% of the total samples analysed including acute- (AML) and chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) were stained by BH1 mAb, and 80% of the non-Hodgkin lymphoma tested, 12 out of 15 cases. In all cases of positive recognition, tumour cells were HLA-DR+, which was further confirmed by staining with commercial anti-HLA-DR mAbs (data not shown). Myeloma (M) cells were not recognised by the BH1 mAb in any of the 3 cases tested, showing similar results to those with the myeloma cell lines (Table 1). However, some myeloma cell lines were stained in low expression with the commercial anti-HLA-DR+, but not with our mAb BH1 (data not shown).

Table 2.

Recognition of tumour cells by human BH1 mAb from 80 patients suffering from different haematological malignancies

| CR/n a | % of cells recognisedb | ΔMFIc | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBL | Bone marrow | Lymph nodes | PBL | Bone marrow | Lymph nodes | ||

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) | 30/35 | 74.9 ± 1.7 (n = 25) | 84.3 ± 5.7 (n = 5) | 32.7 ± 32.9 (n = 25) | 39.8 ± 41.6 (n = 5) | ||

| Acute lymphocytic leukaemia (ALL) | 4/4 | 67.7 ± 15.1 (n = 4) | 11.1 ± 3.5 (n = 4) | ||||

| Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) | 7/13 | 32.9 ± 26.6 (n = 3) | 55.4 ± 26.6 (n = 4) | 23.5 ± 51.1 (n = 3) | 18.7 ± 20.8 (n = 4) | ||

| Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) | 7/10 | 55 ± 14.8 (n = 5) | 21.1 ± 2.2 (n = 2) | 14.3 ± 7.6 (n = 5) | 3.9 ± 2.9 (n = 2) | ||

| Myeloma (ML) | 0/3 | 5.3 ± 2.6 (n = 3) | 7.4 ± 10.8 (n = 3) | ||||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) | 12/15 | 34.2 (n = 1) | 60.5 ± 1.6 (n = 3) | 64.1 ± 8.8 (n = 8) | 19.8 (n = 1) | 56.2 ± 27.5 (n = 3) | 32.1 ± 54.9 (n = 8) |

| Total | 60/80 | ||||||

aCR/n, number of cases recognised by BH1/number of cases tested (n)

bPercentage (%) of cells recognised by BH1. The result is expressed as the Mean ± SD

cMean fluorescence Intensity (ΔMFI) obtained as MFI(BH1 + secondary antibody) − MFI(secondary antibody). The result is expressed as the Mean ± SD

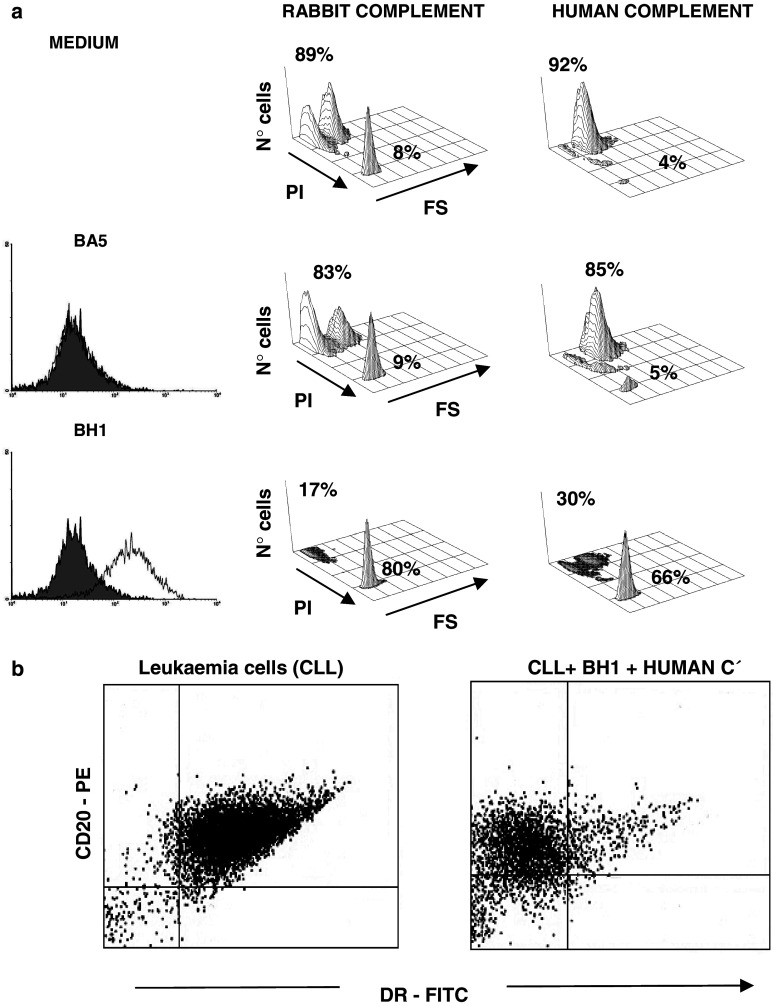

Complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) assays were performed with samples from patients with lymphoproliferative disorders in the presence of BH1 mAb, and rabbit or human complement. The BH1 mAb recognised 15 out of 18 of the leukaemia samples tested. In those cases of positive staining, BH1 was able to induce cell death in the presence of rabbit complement in all cases (percentage of death was variable ranging from 48 to 99%, depending on the tumour DR expression). Interestingly, BH1 also killed tumour cells in the presence of human serum as a source of complement in a similar way (an example is shown in Fig. 3a). To confirm that death cells correspond to tumour HLA-DR+cells, leukaemia cells were stained with anti-CD20 and anti-HLA-DR before and after incubation with BH1 and complement. Figure 3b shows how BH1 mAb is able to kill almost all tumour CD20+ HLA-DR+ cells of a patient suffering from CLL, in the presence of human serum, in only 30 min. These results show that the BH1 is able to activate human complement and induce a very efficient killing of human leukaemia cells.

Fig. 3.

a Target cells were incubated with rabbit (left) or human complement (right) in the presence of medium, BA5 (an isotypic Ab control) or BH1 mAb. The viability of the cells was tested by the incorporation of propidium iodide (PI) by FACS analysis. b Leukaemia cells from a patient suffering from CLL were analysed by flow cytometry with anti-CD20 PE and anti-HLA DR FITC mAbs, before (left) and after (right) incubation with BH1 mAb and human serum as a source of complement

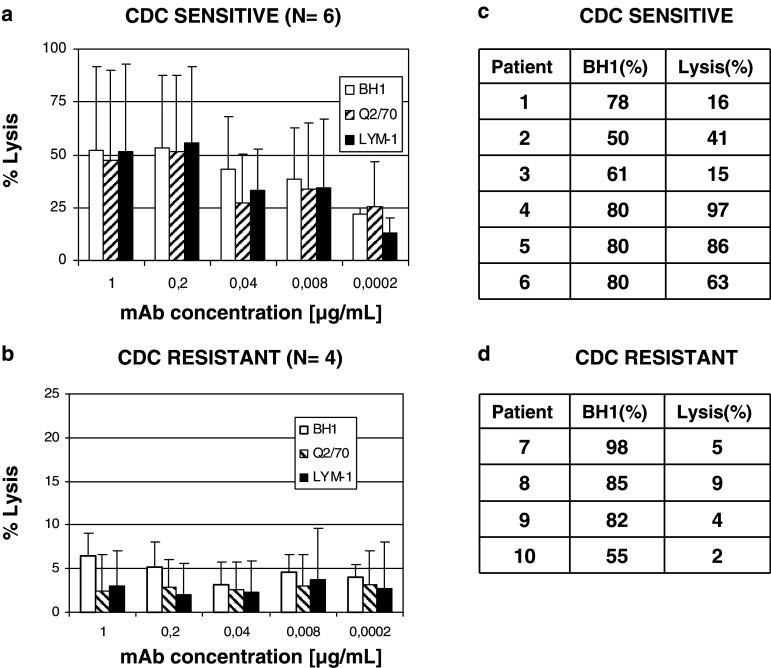

A dose–response curve was produced comparing BH1 with the other HLA class II mAbs (mouse Q2/70 and the chimeric human–mouse CHLym-1), in their ability to induce cell death in the presence of human complement. Samples from ten patients suffering from CLL were included in this study, using limiting concentrations (ranging from 1 to 2 × 10−4 μg/mL) of antibodies (Fig. 4). Commercial human complement was used instead of serum, to try to avoid the differences that could be attributed to complement activity in human serum.

Fig. 4.

Dose–response in complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) assays. CLL samples of 10 patients were incubated with different amounts of anti-HLA class II (BH1, Q2/70 and ChLym1) mAbs and commercial human complement. Patients were grouped according to their sensitivity to complement-mediated lysis in sensitive (a) and resistant (b). The results are indicated as the mean and standard deviations. Percentage of recognition and CDC lysis induced by BH1 (0.2 μg/mL) on sensitive (c) and resistant patients (d)

The results showed a large variation in the percentage of cell lysis between samples, independently of their HLA class II expression levels. Thus, patients were classified into two groups, according to their CDC susceptibility: CDC sensitive (Fig. 4a) and CDC resistant (Fig. 4b). For CDC sensitive samples, the mean of cell lysis was over 50% (using 1 or 0.2 μg/mL of antibody), while CDC resistant samples showed a mean of 6% of cell lysis. Interestingly, all CDC-resistant samples were from patients being treated by chemotherapy at the time of study, although there were still tumoral cells (HLA-DR+) in peripheral blood.

Despite these differences between samples, the percentage of cell lysis induced by BH1, Q2/70 and CHLym-1 was very similar at all concentrations tested (Fig. 4). As expected, cell death was strongly dependent on antibody concentration, and lower Ab concentrations, induced lower levels of death.

Discussion

Antibodies and immunoconjugates are gaining a significant and expanding role in cancer therapy. The HLA-class II molecule is an emerging therapeutic target in haematological malignancies and several anti-HLA class II mAbs have been developed, such as CHLym-1 (chimeric) [11] and Hu1D10 (Apolizumab, a humanized mAb) [13, 25], although some adverse effects have been reported for the humanized mAb Hu1D10 [33].

BABκ,λ transgenic mice were used in this study to generate BH1, a human IgM mAb. Using several approaches, we demonstrate that BH1 is directed against HLA-class II molecules. The competition assay indicates that BH1 recognises a shared epitope with the Q2/70 mAb, which has been shown to interact with the beta chain of both HLA class II DR and DQ molecules [27]. We also show that BH1 recognises and kills primary leukaemia target cells in the presence of complement, suggesting that this antibody could provide an effective therapy in some tumour haematological processes (mainly lymphocytic, also some myeloid leukaemias).

Very recently, two additional human IgG anti-HLA-DR antibodies (1D09C3 and HD8) have also been generated [6, 7, 35], which show tumoricidal activity, although their efficacy in human patients has still to be confirmed. It is reasonable to think that no immune responses would be generated against either of these human antibodies or against our BH1 mAb, bearing in mind that all are fully human.

Human immunotherapy generally uses mouse, chimeric or humanized antibodies, mainly of the IgG isotype [16, 20, 36] due to their specificity and higher level of tumour penetration, although other isotypes (IgM and IgA) have also been considered [3, 10]. The efficacy of these anti-tumour antibodies usually depends on their capacity of activating immunological effector mechanisms, such as complement activation and, sometimes, they are not very effective because human cells produce specific complement-inhibitory factors, which confer resistance to their own serum complement. To avoid this resistance, some mAbs must be used in combination. For example, the anti-CD20 mAb is used together with antibodies to block some of the complement-inhibitory factors (e.g. CD55 or CD59 molecules) [14, 36, 38]. This increases the efficacy of the therapy, but also its cost and the possibility of secondary effects. In this sense, BH1 could have some advantages compared to IgG because the IgM isotype is a very good complement activator. Furthermore, no allotypic differences have been described in the IgM isotype, in contrast to IgG antibodies [30], although its influence on antibody immunogenicity could be very low. Additionally, due to the high molecular weight of IgM, a minor level of entry into normal tissues should be expected, probably with lower secondary effects. If necessary, the isotype of the BH1 mAb could always be changed to IgG.

The present study shows that BH1 is able to kill tumour cells not only in the presence of rabbit complement, but also with human complement. Its ability to activate CDC was almost identical to other anti- HLA class II mAbs (Q2/70 and CH Lym-1), all of them showing a dose-dependent effect (Fig. 4). However, a large variation in killing has been found. In the presence of BH1 and rabbit complement, where 15 patient samples were analysed, cell lysis ranged from 49% to nearly 100%, and death was found in all samples tested. Yet, for human complement, two different groups can be distinguished: sensitive or resistant (Fig. 4).

These differences in CDC susceptibility could be due to several factors, such as a variable production of complement-inhibitory molecules, the presence of complement-resistant cell clones in some patients (indeed, all resistant samples were from patients being treated by chemotherapy) or by other undetermined factors [14, 36, 38]. Although few samples were included in this CDC study, and many more in vitro and in vivo trials are needed, the results indicate that an early introduction of antibodies in therapy could be the best choice. This could also be true for other mAbs.

It is worth pointing out that BH1 was not able to bind to all HLA-class II+ cells tested, especially some myeloma cell lines. A similar situation has been described with other anti-HLA class II mAbs, such as Hu1D10 and CHLym-1, which failed to recognise all HLA class II positive cells tested [35]. The HLA class II is extremely polymorphic due to its highly variable β-chain (more than 500 different HLA-DRβ alleles have been identified) and, probably, BH1 and the other human mAbs can bind to some polymorphic variants, but not to all of them. This evidence shows that, to avoid treatment failures, it is essential to test the antibodies against tumour target cells before starting the immunotherapy process, and that a variety of anti-HLA-class II human mAbs is necessary to cover different alleles. Thus, our human BH1 mAb could be a good candidate as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of different HLA-class II positive leukaemias and other malignancies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Marianne Brüggemann for supplying the transgenic mice used in this work; Angel Torreiro for assistance with maintenance of the mice; Charo de Pablo (Clínica Puerta de Hierro, Madrid) and Professor Alan Epstein (University of Southern California, USA) for providing antibodies Q2/70 and CHLym-1, respectively; and Darío Alves, Cristian Sánchez, Daniel Pérez, Elina Garet, Silvia Lorenzo and Marisa Abad for technical help. The contributions of B. D. and I. S. include the generation and characterisation of monoclonal antibodies, analysis of peripheral blood cells and complement lysis. S. M. performed most of the flow cytometry studies in different populations and supervised the complement lysis and analysis in leukaemia patients. F. G. and A. G. supervised the work undertaken by B. D., I. S. and S. M. in the Hospital and in the University, respectively. This study was supported by the Xunta de Galicia, the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Red del FIS G03/136) and the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Nanobiomed, Consolider-Ingenio2010).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Belén Díaz, Irene Sanjuan and Susana Magadán share authorship; Francisco Gambón and África González–Fernández share leadership.

References

- 1.Adams GP, Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brüggemann M, Caskey HM, Teale C, Waldmann H, Williams GT, Surani MA, Neuberger MS. A repertoire of monoclonal antibodies with human heavy chains from transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86(17):6709–6713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brüggemann M, Teale C, Clark M, Bindon C, Waldmann H. A matched set of rat/mouse chimeric antibodies identification and biological properties of rat H chain constant regions mu, gamma 1, gamma 2a, gamma 2b, gamma 2c, epsilon, and alpha. J Immunol. 1989;142:3145–3150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgess T, Coxon A, Meyer S, Sun J, Rex K, Tsuruda T, Chen Q, Ho SY, Li L, Kaufman S, McDorman K, Cattley RC, Sun J, Elliott G, Zhang K, Feng X, Jia XC, Green L, Radinsky R, Kendall R. Fully human monoclonal antibodies to hepatocyte growth factor with therapeutic potential against hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met-dependent human tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1721–1729. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlo-Stella C, Di Nicola M, Turco MC, Cleris L, Lavazza C, Longoni P, Milanesi M, Magni M, Ammirante M, Leone A, Nagy Z, Gioffre WR, Formelli F, Gianni AM. The anti-human leukocyte antigen-DR monoclonal antibody 1D09C3 activates the mitochondrial cell death pathway and exerts a potent antitumor activity in lymphoma-bearing nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1799–1808. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlo-Stella C, Guidetti A, Di Nicola M, Longoni P, Cleris L, Lavazza C, Milanesi M, Milani R, Carrabba M, Farina L, Formelli F, Gianni AM, Corradini P. CD52 antigen expressed by malignant plasma cells can be targeted by alemtuzumab in vivo in NOD/SCID mice. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlo-Stella C, Guidetti A, Di Nicola M, Lavazza C, Cleris L, Sia D, Longoni P, Milanesi M, Magni M, Nagy Z, Corradini P, Carbone A, Formelli F, Gianni AM. IFN-gamma enhances the antimyeloma activity of the fully human anti-human leukocyte antigen-DR monoclonal antibody 1D09C3. Cancer Res.1. 2007;67(7):3269–3275. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis CG, Jia XC, Feng X, Haak-Frendscho M. Production of human antibodies from transgenic mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;248:191–200. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-666-5:191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dechant M, Bruenke J, Valerius T. HLA class II antibodies in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:465–475. doi: 10.1016/S0093-7754(03)00252-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dechant M, Vidarsson G, Stockmeyer B, Repp R, Glennie MJ, Gramatzki M, van de Winkel JG, Valerius T. Chimeric IgA antibodies against HLA class II effectively trigger lymphoma cell killing. Blood. 2002;100:4574–4580. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denardo GL, Tobin E, Chan K, Bradt BM, Denardo SJ. Direct antilymphoma effects on human lymphoma cells of monotherapy and combination therapy with CD20 and HLA-DR antibodies and 90Y-labeled HLA-DR antibodies. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7075s–7079s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM, Zajac B, Henle G, Henle W. Morphological and virological investigations on cultured Burkitt tumor lymphoblasts (strain Raji) J Natl Cancer Inst. 1966;37(4):547–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilliland LK, Walsh LA, Frewin MR, Wise MP, Tone M, Hale G, Kioussis D, Waldmann H. Elimination of the immunogenicity of therapeutic antibodies. J Immunol. 1999;162:3663–3671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golay J, Zaffaroni L, Vaccari T, Lazzari M, Borleri GM, Bernasconi S, Tedesco F, Rambaldi A, Introna M. Biologic response of B lymphoma cells to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in vitro: CD55 and CD59 regulate complement-mediated cell lysis. Blood. 2000;95:3900–3908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haan KM, Kwok WW, Longnecker R, Speck P. Epstein-Barr virus entry utilizing HLA-DP or HLA-DQ as a coreceptor. J Virol. 2000;74(5):2451–2454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.5.2451-2454.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hale G, Cobbold S, Novitzky N, Bunjes D, Willemze R, Prentice HG, Milligan D, MacKinnon S, Waldmann H. CAMPATH-1 antibodies in stem-cell transplantation. Cytotherapy. 2001;3:145–164. doi: 10.1080/146532401753173981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu P, Glasky MS, Yun A, Alauddin MM, Hornick JL, Khawli LA, Epstein AL. A human–mouse chimeric Lym-1 monoclonal antibody with specificity for human lymphomas expressed in a baculovirus system. Hum Antibodies Hybridomas. 1995;6(2):57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isaacs JD, Wing MG, Greenwood JD, Hazleman BL, Hale G, Waldmann H. A therapeutic human IgG4 monoclonal antibody that depletes target cells in humans. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;106:427–433. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köhler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu C, DeNardo G, Tobin E, DeNardo S. Antilymphoma effects of anti-HLA-DR and CD20 monoclonal antibodies (Lym-1 and Rituximab) on human lymphoma cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2004;19:545–561. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2004.19.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lonberg N. Human antibodies from transgenic animals. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1117–1125. doi: 10.1038/nbt1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magadán S, Valladares M, Suárez E, Sanjuán I, Molina A, Ayling C, Davies SL, Zou X, Williams GT, Neuberger MS, Brüggemann M, Gambón F, Díaz-Espada F, González-Fernández A. Production of antigen-specific human monoclonal antibodies: comparison of mice carrying IgH/kappa or IgH/kappa/lambda transloci. Biotechniques. 2002;33:680. doi: 10.2144/02333dd04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mavromatis B, Cheson BD. Monoclonal antibody therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1874–1881. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molina A, Valladares M, Magadán S, Sancho D, Viedma F, Sanjuán I, Gambón F, Sánchez-Madrid F, González-Fernández A. The use of transgenic mice for the production of a human monoclonal antibody specific for human CD69 antigen. J Immunol Methods. 2003;282:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mone AP, Huang P, Pelicano H, Cheney CM, Green JM, Tso JY, Johnson AJ, Jefferson S, Lin TS, Byrd JC. Hu1D10 induces apoptosis concurrent with activation of the AKT survival pathway in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2004;103:1846–1854. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagy ZA, Hubner B, Lohning C, Rauchenberger R, Reiffert S, Thomassen-Wolf E, Zahn S, Leyer S, Schier EM, Zahradnik A, Brunner C, Lobenwein K, Rattel B, Stanglmaier M, Hallek M, Wing M, Anderson S, Dunn M, Kretzschmar T, Tesar M. Fully human, HLA-DR-specific monoclonal antibodies efficiently induce programmed death of malignant lymphoid cells. Nat Med. 2002;8:801–807. doi: 10.1038/nm736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flomenberg N, Knowles RW, Williams D, Horibe K, Rosenkrantz K, Dupont B. T lymphocyte clones detecting novel supertypic HLA class II allospecificities. Berlin: Springer; 1985. pp. 270–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson IC, Zou X, Popov AV, Cook GP, Corps EM, Humphries S, Ayling C, Goyenechea B, Xian J, Taussig MJ, Neuberger MS, Brüggemann M. Antibody repertoires of four- and five-feature translocus mice carrying human immunoglobulin heavy chain and kappa and lambda light chain yeast artificial chromosomes. J Immunol. 1999;163:6898–6906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostendorf T, van Roeyen CR, Peterson JD, Kunter U, Eitner F, Hamad AJ, Chan G, Jia XC, Macaluso J, Gazit-Bornstein G, Keyt BA, Lichenstein HS, LaRochelle WJ, Floege J. A fully human monoclonal antibody (CR002) identifies PDGF-D as a novel mediator of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2237–2247. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000083393.00959.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oxelius VA, Aurivillius M, Carlsson AM, Musil K. Serum Gm allotype development during childhood. Scand J Immunol. 1999;50:440–446. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouleau M, Namikawa R, Antonenko S, Carballido-Perrig N, Roncarolo MG. Antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells mediate human fetal pancreas allograft rejection in SCID-hu mice. J Immunol. 1996;157(12):5710–5720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quaranta V, Indiveri F, Glassy MC, Ng A, Russo C, Molinaro GA, Pellegrino MA, Ferrone S. Serological, functional, and immunochemical characterization of a monoclonal antibody (MoAb Q2/70) to human Ia-like antigens. Hum Immunol. 1980;1:211–223. doi: 10.1016/0198-8859(80)90016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi JD, Bullock C, Hall WC, Wescott V, Wang H, Levitt DJ, Klingbeil CK. In vivo pharmacodynamic effects of Hu1D10 (remitogen), a humanized antibody reactive against a polymorphic determinant of HLA-DR expressed on B cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:1303–1312. doi: 10.1080/10428190290026376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suárez E, Magadán S, Sanjuán I, Valladares M, Molina A, Gambón F, Díaz-Espada F, González-Fernández A. Rearrangement of only one human IGHV gene is sufficient to generate a wide repertoire of antigen specific antibody responses in transgenic mice. Mol Immunol. 2006;43:1827–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tawara T, Hasegawa K, Sugiura Y, Tahara T, Ishida I, Kataoka S. Fully human antibody exhibits pan-human leukocyte antigen-DR recognition and high in vitro/vivo efficacy against human leukocyte antigen-DR-positive lymphomas. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:921–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treon SP, Mitsiades C, Mitsiades N, Young G, Doss D, Schlossman R, Anderson KC. Tumor cell expression of CD59 is associated with resistance to CD20 serotherapy in patients with B-cell malignancies. J Immunother. 2001;24:263–271. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang XD, Jia XC, Corvalan JR, Wang P, Davis CG. Development of ABX-EGF, a fully human anti-EGF receptor monoclonal antibody, for cancer therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;38:17–23. doi: 10.1016/S1040-8428(00)00134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ziller F, Macor P, Bulla R, Sblattero D, Marzari R, Tedesco F. Controlling complement resistance in cancer by using human monoclonal antibodies that neutralize complement-regulatory proteins CD55 and CD59. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2175–2183. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]