Abstract

We describe the modification of tumour cells to enhance their capacity to act as antigen presenting cells with particular focus on the use of costimulatory molecules to do so. We have been involved in the genetic modification of tumour cells to prepare a whole cell vaccine for nearly a decade and we have a particular interest in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). AML is an aggressive and difficult to treat disease, especially, for patients for whom haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplant is not an option. AML patients who have a suitable donor and meet HSC transplant fitness requirements, have a 5-year survival of 50%; however, for patients with no suitable donor or for who age is a factor, the prognosis is much worse. It is particularly poor prognosis patients, who are not eligible for HSC transplant, who are likely to benefit most from immunotherapy. It would be hoped that immunotherapy would be used to clear residual tumour cells in these patients in the first remission following standard chemotherapy treatments and this will extend the remission and reduce the risk of a second relapse associated with disease progression and poor mortality rates. In this symposia report, we will focus on whole cell vaccines as an immunotherapeutic option with particular reference to their use in the treatment of AML. We will aim to provide a brief overview of the latest data from our group and considerations for the use of this treatment modality in clinical trials for AML.

Keywords: Costimulatory molecules, Acute myeloid leukaemia, Whole cell vaccines, 4-1BB ligand, Immunotherapy, Tumour immunity

Introduction

Tumours are able to escape immune surveillance by virtue of the downregulation of immune markers such as costimulatory molecules, major histocompatability complex (MHC), cytokines and through poor peptide presentation. Immune surveillance itself selects for these characteristics, leading to escape variants. Eventually, tumour cells outgrow their environment and invade surrounding tissues causing organ damage and eventually, death. Despite the features which allow the tumour to escape immune surveillance, tumours were shown to elicit measurable, albeit weak, immunogenic responses in vitro and in vivo [7, 14, 19]. It was possible to isolate patient T cells that recognise a particular tumour, however these T cells were often anergic and unable to mediate tumour destruction. This may be due, in part, to the secretion of immunosuppressive factors by the tumour cells [6]. Various studies, which have involved the modification of tumour cells to create whole cell vaccines for the cancer therapy, have utilised the re-introduction of MHC, costimulatory molecules, cytokines, tumour-associated antigens, adhesion molecules and chemokines or the preparation of tumour-dendritic cell fusions (reviewed in [23]).

Acute myeloid leukaemia

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) is a malignant clonal disorder of immature haematopoietic cells (reviewed in [45]). AML is not heritable and the cause for most patients with de novo AML is largely unknown with no documented exposure to carcinogens. Until recently, the diagnosis of AML has been based primarily on the FAB system in which morphological criteria were used to classify AML into subtypes from M0 through to M7 [3]. This was superseded by the WHO classification system which takes into account further factors of clinical relevance such as genetic and immunophenotypic characteristics (reviewed in [5]) and newly defines AML as patients with 20% or more myeloblasts in the bone marrow rather than the previous 30% cutoff. This means that a new group of patients previously classified as having myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) are now included in the AML group. AML is a highly heterogeneous disease (reviewed most recently in [46]) as reflected by the increasingly complex subclassifications which acknowledge cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities in the diseased cells of patients. These additional abnormalities have implications for predicting patient survival and response to novel therapeutic strategies. For most AML patients, one of the most effective treatments to date has been bone marrow and haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplants which have increased in effectiveness through improved mobilisation and stem cell selection techniques [18]. However, for patients who do not have an eligible donor or for whom age excludes them from transplant, immunotherapy offers a very promising treatment option.

Upregulation of costimulatory molecules to produce a whole cell vaccine

Normal T cell activation through antigen presentation on MHC requires a second signal usually provided through costimulatory receptors. Although costimulation is mainly provided through CD28-B7 signals, other costimulatory and adhesion molecules appear to amplify and diversify the response [61]. To date, the role of B7-1 and B7-2 in the provision of costimulation has been the most widely studied and appears to be the predominant pathway for the delivery of costimulatory signals [42]. The efficacy of other costimulatory molecules, particularly those which are members of the TNFR/TNF ligand family (reviewed in [12]), including 4-1BB/4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL) (also reviewed in [9, 13]), CD27/CD70 (also reviewed in [13]) and OX40/OX40L (also reviewed in [13, 62]) were shown to play important roles in the amplification of the immune response.

B7-1 and B7-2 are type I transmembrane glycoproteins expressed on the surface of antigen presenting cells (APCs). They share only 25% sequence similarity [21], yet both bind to the CD28 receptor on T cells, providing the positive signal necessary to induce T-cell proliferation. Both molecules bind more avidly to the CTLA4 receptor (on T cells) and this secondary binding limits the T cell response. Both B7-1 and B7-2 ligands bind CTLA-4 with 100- to 1,000-fold higher affinity than they do to CD28, and B7-1 has about tenfold higher affinity for both receptors compared with B7-2 [28, 44]. Although the overlapping function of B7-1 and B7-2 is to costimulate T cells, they have different roles in T helper (Th)1 or Th2 development. B7-1 preferentially induces IL-2 release and Th1 differentiation while B7-2 plays an essential role in inducing IL-4 secretion and Th2 responses [22, 38]. Another functional difference between B7-1 and B7-2 is that their engagement delivers distinct transmembrane signals to B cells. B7-1 mAb crosslinking results in blocking both B cell proliferation and the production of IgG1 and IgG2a Ab isotypes [33, 55]. Conversely, crosslinking of B7-2 with anti-B7-2 mAb enhances B cell proliferation and the production of murine IgG1 and IgG2a isotypes [35, 42, 55]. The distinct signals transmitted to APCs by B7-1 and B7-2 may be due to differences in their cytoplasmic tails and/or to the structure and potential oligomerization state of their extracellular regions, which would control the organization of the associated intracellular signalling complexes.

CD28 and CTLA-4 share about 30% sequence identity, and are expressed on the surface of T cells [4, 42]. Upon binding to their ligand, B7-1 or B7-2, CD28 delivers a positive signal which enhances T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion and prevents the induction of T cell anergy [43, 56]. The response-limiting signal is provided through the concurrent binding of the CTLA-4 receptor. The binding of B7-1 or B7-2 by the CTLA-4 receptor down-regulates the response maintaining T cell homeostasis and self-tolerance [57, 59, 60].

Use of 4-1BBL to enhance anti-tumour responses in murine models of cancers

In AML, few studies have examined the ability of B7-1 to costimulate T cell responses in direct comparison to B7-2 [15] and none have investigated the role of 4-1BBL costimulation in this disease. The role of 4-1BB:4-1BBL interaction in the provision of costimulation has become increasingly apparent [9, 32, 54, 61]. 4-1BB is an inducible molecule expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [58]. In mice, 4-1BB is known to be activation induced on splenocytes and on both helper and cytolytic T cells through studies of its analogue [39, 51]. The expression takes several hours, slowly increases and peaks at 60 h and declines again by 110 h [26, 52, 58]. Like its receptor, 4-1BBL is inducible on T cells [51]. Stimulation of the 4-1BB signalling pathway, through the use of monoclonal antibodies, has been shown to lead to an elevated level of proliferation of CD8+ compared with CD4+ T cells [54].

4-1BBL:4-1BB signalling was shown to induce anti-tumour T cell immune responses and cause tumour cell clearance even in the absence of CD28 signalling [31]. This exemplifies the role 4-1BBL appears to play when CD28 signalling is limiting and 4-1BB:4-1BBL is thought to extend and amplify T cell immune responses when CD28 levels begin to drop. 4-1BBL has been shown to play a role in the augmentation of suboptimal CTL cell responses and in skin allograft rejection again demonstrating it’s role as an enhancer of responses when the signals provided by B7-1 and B7-2 are suboptimal [17, 40]. 4-1BB:4-1BBL appears to be a sustainer of responses subsequent to CD28 costimulation [58].

A number of studies which have investigated the capacity of 4-1BBL to enhance anti-tumour immunogenicity in models of malignancy have indicated that 4-1BBL:4-1BB signalling is very effective in the production of long-term systemic anti-tumour responses [29, 48, 49]. We and others have shown that 4-1BBL is highly effective in enhancing anti-tumour immune responses mediated through CD28 in lymphomas [29] and solid tumours [48, 49]. We have previously shown that the up regulation of 4-1BBL by transfection can enhance tumour immunogenicity to a greater extent than either B7-1 or B7-2 alone [29] and we and others have shown that 4-1BBL is effective at enhancing primary T cell responses even in the absence of CD28 [16, 31, 53] however for protective immunity, CD28:B7 signalling was necessary [31]. Antibody blocking in the CTL assays demonstrated that both 4-1BB:4-1BBL and B7:CD28 signalling were requisite for anti-tumour responses ex vivo, and that B7:CD28 responses involved both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells while 4-1BB:4-1BBL responses could be mediated solely by CD8+ T cells [29].

Shuford et al. [54] have also shown that anti-4-1BB costimulation markedly enhanced interferon-γ production by CD8+ T cells and that anti-4-1BB mediated proliferation of CD8+ T cells appears to be IL-2 independent. The results of these studies suggest that the regulatory signals delivered by the 4-1BB receptor play an important role in the regulation of cytotoxic T cells in cellular immune responses to antigen. Lee et al. [41], showed that 4-1BB promotes the survival of CD8+ T lymphocytes by increasing expression of anti-apoptotic genes bcl-X L and bfl-l via 4-1BB-mediated NF-κB activation preventing activation induced cell death (AICD). Reduced apoptosis observed after costimulation in the presence of accessory cells correlated with increased levels of Bcl-X(L) in CD8+ T cells, while Bcl-2 expression remained unchanged suggesting that 4-1BB enhanced expansion, survival and effector functions of newly primed CD8+ T cells, acting at least in part, directly on these cells. As 4-1BB triggering could be protracted from the TCR signal, 4-1BB agonists may function through these mechanisms to enhance or rescue sub-optimal immune responses [41]. Finally, all these data suggest that 4-1BB:4-1BBL signalling supports Th1 development.

4-1BBL in a murine model of AML

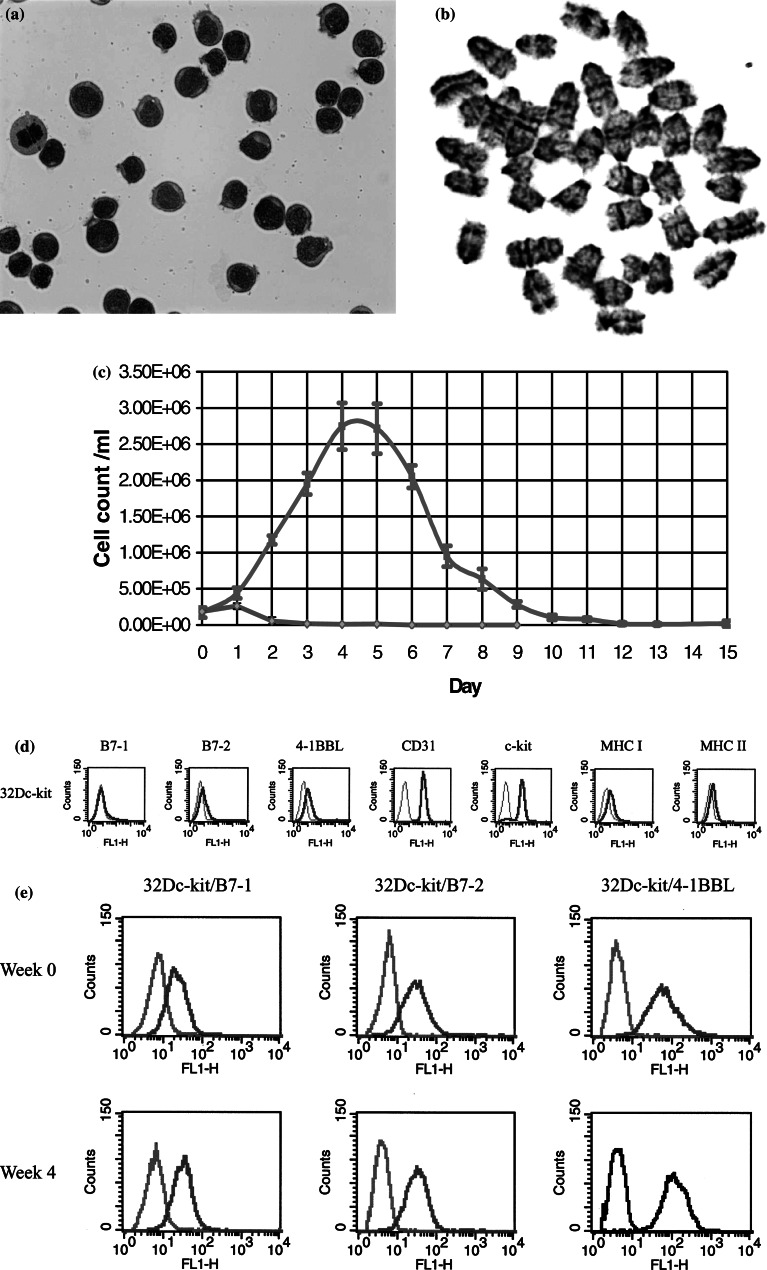

We have used the 32Dc-kit cell line as a murine model of AML [24]. The 32D cell line is a non-tumourigenic myeloid cell line which is IL-3 dependent [27] (Fig. 1). Our own experiments injecting these cells into sub-lethally irradiated [30] and non-irradiated mice have led to no signs of disease over extended periods of up to 250 days. 32D was previously modified by various oncogenes such as BCR-ABL [30], FLT3-ITD [50] and fes [37] and examined for the effects of transgene expression on tumourigenicity, cell doubling time and IL-3 factor dependence. The 32Dc-kit was made through the transduction of a retroviral vector expressing the wild type murine c-kit gene in the 32D cell line [24]. When injected into mice, c-kit ligand, also known as steel factor, in the circulation is thought to stimulate the 32Dc-kit cells to proliferate continuously, leading to the development of a leukaemia-like disease in mice. Hu et al. [34] showed that intravenous injection of one million 32Dc-kit cells into its syngeneic host, led to the development of a leukaemia-like disease following a greater than 150-day follow-up period. However, the survival time could be shortened to 56 days through the sub-lethal irradiation (900cGy) of the mice prior to 32Dc-kit injection. The role of irradiation is thought to create more space for the engrafting cells to grow; however, irradiation is also immunosuppressive. In our studies of AML-like disease in mice, it would have been inappropriate to irradiate our mice due to the unknown effects of irradiation on the recovering immune system. Gommerman et al. [25] injected five million 32Dc-kit cells into their mice, and after 6–7 weeks, found 32Dc-kit cells in the spleen and bone marrow, suggesting that this was a reliable indicator for the eventual development of lethal leukaemia. However, we found that in our studies, 2.5×106 32Dc-kit cells injected into synegeneic C3H/HeN mice took up to 150 days to lead to an overt leukaemia phenotype.

Fig. 1.

Characterisation of the 32Dc-kit cells as a model of murine AML and costimulatory molecule expression following electropration with each transgene. a 32Dc-kit cells were examined following Giemsa staining and shown to have the morphology of blast-like cells; b G-banding analysis of the 32Dc-kit cells indicated the presence of acrocentric chromosomes typical of mouse cells; c cell counts following trypan blue exclusion indicated that the 32Dc-kit cells were IL-3 dependent (green line) and had a doubling time of just over 24 h; d FACS analysis showed that the 32Dc-kit cells expressed the myeloid marker CD31, MHC class I and II, surface c-kit and some 4-1BBL; e weekly FACS analysis indicated that the expression of the B7-1, B7-2 and 4-1BBL transgenes were stable in the transfected 32Dc-kit cells

We produced a number of cell line variants expressing either B7-1, B7-2 or 4-1BBL in the pcDNA3.1/Zeo (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) vector. As a control for any effects of the vector, we also produced a vector-only control. We then injected mice with either 2.5×106 cells (modified or parental; n=8 per group) or more recently, 5×106 cells (modified or parental; n=8 per group) in serum-free media. We are following each group and observing for signs of leukaemia. It is of note that to date none of the modified tumour cells, except vector alone, have led to tumour development in the mice injected with 2.5×106 cells. Cells from the spleen and bone marrow from mice which developed signs of disease were replaced into culture and were resistant to neomycin, the selectable marker for the c-kit expressing plasmid. FACS analysis also indicated that the levels of surface c-kit expression was similar to that found on the parental 32Dc-kit cells. The tumourigenicity experiments are now being repeated and mice surviving the initial tumourigenicity study have recently been challenged with 5×106 unmodified parental tumour cells. Mixed lymphocyte reactions showed only significant cytokine release (using the CBA kit, BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK) from naïve T cells incubated with 4-1BBL expressing 32Dc-kit cells but not those expressing either B7-1 or B7-2 alone. These cytokines were IL-2, IFNγ and TNFα (with no IL-4 or IL-5 production) and are suggestive of a Th1 response.

Development of a human whole cell vaccine

We have obtained human B7-1 subcloned into the lentiviral vector called HR’SINctwSV [8] and subcloned human B7-2 and 4-1BBL cDNAs in the same backbone of vector. The SIN-lentiviral backbone (HR’SINctwSV) was designed especially for myeloid cells and has been shown to result in high levels of transgene expression in AML blasts [8]. Important vector features contributing to this efficiency are the presence of factors that enhance nuclear import [20, 64] and RNA stability [65], as well as the use of a myeloid efficient promoter derived from spleen focus forming virus long terminal repeats [2]. Enhanced lentiviral vector derived transgene expression in hematopoietic cells was observed by the incorporation of these elements individually and in combination [1, 63].

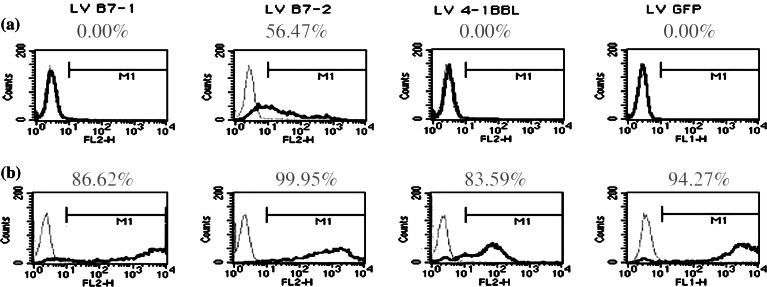

We used the HR’SINctwSV vector ± transgene to transduce four human AML cell lines U937, P39, NB4 and HL60. U937 is a monoblastoid cell line, P39/Tsugane cells have a myelomonocytoid nature and were derived from an AML patient whose disease had transformed from MDS, while both NB4 and HL60 are promyelocytic cell lines. Each vector led to consistently high levels of expression of each of the costimulatory molecules at MOIs as low as 10 (Fig. 2). We then incubated purified allogeneic normal donor T cells (South Thames Regional Blood Transfusion Service, London, UK) with each of the cell lines and investigated T cell responses by virtue of [methyl-3H]-thymidine uptake. Like human AML cells [11], the AML cell lines we used all expressed B7-2 but generally did not express B7-1 or 4-1BBL. We found that T cell responses to each of the modified cell lines, using vector control and unmodified cells as controls, varied. We were aware that MHC mismatch was an issue between allogeneic normal donor T cells and the cell lines, as none of the normal donors were typed before receipt. This was a major limitation of our study and to control for it, we concurrently incubated the naïve normal donor T cells with unmodified cell line, cell line modified with vector alone and cell line modified with vector expressing the costimulatory molecule, to determine the contribution of MHC-mismatch to the T cell response observed. As expected, there was some variation depending on the normal donor used although there was also a consistency in terms of which transgene led to the best T cell response. We found that not one single costimulatory molecule induced the best T cell response against all the cell lines and it was the cell line itself which dictated which of the costimulatory molecules was the most effective when assessing multiple different normal donor samples of unknown haplotype. We found that the results we obtained were reproducible in independent experiments and that the contribution of the most effective costimulatory molecule was discernable from that of the MHC mismatch response and significantly exceeded it. We used FACS analyses to investigate the pre-modified tumour cell costimulatory molecule expression in the cell lines to see if this gave any indication of which costimulatory molecule, when used to modify the cell line, would be the most effective at eliciting a T cell response. Previous investigators [10, 47] had suggested that it was the immunogenicity of a cell line which dictated whether B7-1 or B7-2 was the most effective at converting mouse tumour cells into a whole cell vaccine. It would be impossible to test the immunogenicity of human cell lines on the same criteria used for mouse cell lines that an immunogenic cell line is one which when irradiated and injected into mice leads to immunity in the mice against later live cell challenge. We looked to see if pre-existing costimulatory molecule expression affected which costimulatory molecule best enhanced tumour immunogenicity and found no obvious pre-disposing expression using four AML cell lines. We are now examining ex vivo T cell responses in samples taken from AML patients in remission against autologous AML tumour cells taken at disease presentation. This would circumvent the problems of mismatch and provide an ex vivo model of the capacity of patient T cells to respond to modified autologous tumour cells as recently described by our colleagues [8]. However, acquisition of these paired samples is time consuming, often taking 3–4 months between disease presentation and achievement of first remission and AML cells taken at disease presentation can be very fragile when defrosted and transduced.

Fig. 2.

Costimulatory molecule transgene expression on the human AML cell line, P39, (a) prior to and (b) following lentiviral transduction with the B7-1, B7-2 or 4-1BBL costimulatory molecules. Transductions with LV/GFP, LV/B7-1, LV/B7-2 and LV/4-1BBL were performed at an MOI of ten and FACs analysis performed for surface transgene expression. Following transductions [7], 106 cells were stained with 1 μg Ab for 30 min at 4°C, washed and then analysed using the FACScalibur. P39, like most primary human AML cells, expressed some B7-2 but no B7-1 [10] or 4-1BBL and following transduction at an MOI of ten surface expression of each of the transgenes was significantly increased

Specificity of the immune response against tumour cells-autoimmunity and specificity

The use of whole cell vaccines has raised concerns regarding the induction of autoimmunity. This is due to the largely unknown nature of the tumour cell being modified. The benefits of using tumour cells as a whole cell vaccine are that the tumour antigen(s) do not need to be defined and that any antigen which is inappropriately or overexpressed should be recognised as a tumour antigen in the presence of immune markers otherwise deregulated or inadequately expressed on the unmodified tumour cell. Animal models (often mouse) have indicated that despite the large number of tumour antigens likely to be expressed on the tumour cell, alongside normal ‘self’ proteins, that to date autoimmunity has not been reported in immunocompetent mice injected with modified tumour cells. However, autoimmunity is an issue that needs to be considered, especially in the light of the problems experienced in some clinical trials on humans. However, it is possible that for the vast majority of patients the benefits of immunotherapy (especially for poor prognosis patients with few other treatment options) may outweigh the relatively small risk of inducing autoimmunity.

In our A20 mouse model of B-cell lymphoma, we showed that the mice which had been injected with A20 cells modified to express B7-2 or 4-1BBL were able to reject these cells [29]. These mice were also able to reject a later systemic challenge of unmodified parental A20 cells injected into the opposite flank. We did find that all of the tumour cells (modified and unmodified) could form tumours in immuno-compromised BALB/c nu/nu mice showing that the modified tumour cells were in fact still tumourigenic but were being removed by the T cells in the immunocompetent BALB/c mice. Approximately, 25% of the immunocompetent BALB/c mice did form tumours following injection with the A20/B7-2 cells. FACs analysis of these cells showed that they had lost B7-2 expression suggesting that in the absence of drug selection in culture some of the modified cells lost their transgene expression and reverted to the wild type phenotype. CTL analysis on splenocytes from mice injected with A20/B7-2 or A20/4-1BBL which had also survived challenge showed good CTL responses against A20 and the syngeneic K46J cell line in chromium release assays, suggesting these two cell lines shared some of the same tumour antigens. K46J is also a B-cell lymphoma cell line which was developed at the same time as A20 by the same technique [36]. However, there was no CTL activity by the splenocytes from A20/B7-2 or A20/4-1BBL surviving mice against the scid thymoma cell line ST-D2 or the C57BL/6 lymphoma cell line EL4. Similar studies on tumour cells from mice which had succumbed to leukaemia following injection with the 32Dc-kit modified cell lines and CTLs are now being performed.

Future directions

We are currently repeating tumourigenicity and challenging experiments on mice using our 32Dc-kit model with costimulatory molecule transgene expression and controls. We are extending our human studies to include primary cells. We are hoping to type normal donor samples prior to allogeneic MLRs to determine the contribution of the mismatch to the T cell response and where possible, we will try to minimise the MHC mismatch. We will perform allogeneic and autologous MLRs on AML patient samples which we have modified using the lentiviral vector to express one of the costimulatory molecules and see if there is a consistent costimulatory molecule which provides the best T-cell activation. Ideally, we would like to determine whether the use of a cytokine in combination with the ‘best option’ costimulatory molecule further and consistently enhances T cell responses against modified and in CTLs unmodified autologous tumour cells.

Acknowledgements

Lucas Chan and Barbara-ann Guinn are funded by Leukaemia Research Fund.

Abbreviations

- AML

Acute myeloid leukaemia

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- MHC

Major histocompatability complex

- APC

Antigen presenting cells

- HSC

Haematopoietic stem cell

- 4-1BBL

4-1BB ligand

- Th

T helper

- s.c

Sub-cutaneous

Footnotes

This article is a symposium paper from the conference “Progress in Vaccination against Cancer 2004 (PIVAC 4)”, held in Freudenstadt-Lauterbad, Black Forest, Germany, on 22–25 September 2004

References

- 1.Barry SC, Harder B, Brzezinski M, Flint LY, Seppen J, Osborne WR. Lentivirus vectors encoding both central polypurine tract and posttranscriptional regulatory element provide enhanced transduction and transgene expression. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1103–1108. doi: 10.1089/104303401750214311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum C, Hegewisch-Becker S, Eckert HG, Stocking C, Ostertag W. Novel retroviral vectors for efficient expression of the multidrug resistance (mdr-1) gene in early hematopoietic cells. J Virol. 1995;69:7541–7547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7541-7547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, Sultan C. Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group. Br J Haematol. 1976;33:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunet JF, Denizot F, Luciani MF, Roux-Dosseto M, Suzan M, Mattei MG, Golstein P. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily—CTLA-4. Nature. 1987;328:267–270. doi: 10.1038/328267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunning RD. Classification of acute leukemias. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2003;20:142–153. doi: 10.1016/S0740-2570(03)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buggins AG, Lea N, Gaken J, Darling D, Farzaneh F, Mufti GJ, Hirst WJ. Effect of costimulation and the microenvironment on antigen presentation by leukemic cells. Blood. 1999;94:3479–3490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnet M. Cancer—a biological approach. III. Viruses associated with neoplastic conditions. Br Med J. 1957;1:841–847. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5023.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan L, Hardwick N, Darling D, Galea-Lauri J, Gäken J, Devereux S, Kemeny M, Mufti GJ, Farzaneh F. IL-2/B7.1 fusagene transduction of AML blasts by a self-inactivating lentiviral vector stimulates T-cell responses in vitro: a strategy to generate whole cell vaccines for AML. Mol Ther. 2004;11:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, McGowan P, Ashe S, Johnston J, Li Y, Hellstrom I, Hellstrom KE. Tumour immunogenicity determines the effect of B7 costimulation on T-cell mediated immunity. J Exp Med. 1994;179:523. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheuk AT, Mufti GJ, Guinn BA. Role of 4-1BB:4-1BB ligand in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:215–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello RT, Mallet F, Sainty D, Maraninchi D, Gastaut JA, Olive D. Regulation of CD80/B7-1 and CD86/B7-2 molecule expression in human primary acute myeloid leukemia and their role in allogenic immune recognition. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:90–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<90::AID-IMMU90>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croft M. Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:609–620. doi: 10.1038/nri1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croft M. Costimulation of T cells by OX40, 4-1BB, and CD27. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:265–273. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00025-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBenedette MA, Chu NR, Pollok KE, Hurtado J, Wade WF, Kwon BS, Watts TH. Role of 4-1BB ligand in costimulation of T lymphocyte growth and its upregulation on M12 B lymphomas by cAMP. J Exp Med. 1995;181:985–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeBenedette MA, Wen T, Bachmann MF, Ohashi PS, Barber BH, Stocking KL, Peschon JJ, Watts TH. Analysis of 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL)-deficient mice and of mice lacking both 4-1BBL and CD28 reveals a role for 4-1BBL in skin allograft rejection and in the cytotoxic T cell response to influenza virus. J Immunol. 1999;163:4833–4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:991–998. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunussi-Joannopoulos K, Dranoff G, Weinstein HJ, Ferrara JL, Bierer BE, Croop JM. Gene immunotherapy in murine acute myeloid leukemia: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor tumor cell vaccines elicit more potent antitumor immunity compared with B7 family and other cytokine vaccines. Blood. 1998;91:222–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estey EH. Treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia. Oncology (Huntingt) 2002;16:343–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foley EJ. Antigenic properties of methylcholanthrene-induced tumors in mice of the strain of origin. Cancer Res. 1953;13:835–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Follenzi A, Ailles LE, Bakovic S, Geuna M, Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat Genet. 2000;25:217–222. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman GJ, Freedman AS, Segil JM, Lee G, Whitman JF, Nadler LM. B7, a new member of the Ig superfamily with unique expression on activated and neoplastic B cells. J Immunol. 1989;143:2714–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman GJ, Boussiotis VA, Anumanthan A, Bernstein GM, Ke XY, Rennert PD, Gray GS, Gribben JG, Nadler LM. B7-1 and B7-2 do not deliver identical costimulatory signals, since B7-2 but not B7-1 preferentially costimulates the initial production of IL-4. Immunity. 1995;2:523–532. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galea-Lauri J. Immunological weapons against acute myeloid leukaemia. Immunology. 2002;107:20–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gommerman JL, Berger SA. Protection from apoptosis by steel factor but not interleukin-3 is reversed through blockade of calcium influx. Blood. 1998;91:1891–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gommerman JL, Sittaro D, Klebasz NZ, Williams DA, Berger SA. Differential stimulation of c-kit mutants by membrane-bound and soluble steel factor correlates with leukemic potential. Blood. 2000;96:3734–3742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwin RG, Din WS, Davis-Smith T, Anderson DM, Gimpel SD, Sato TA, Maliszewski CR, Brannan CI, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Farrah T, Armitage RJ, Fanslow WC, Smith CA. Molecular cloning of a ligand for the inducible T cell gene 4-1BB: a member of an emerging family of cytokines with homology to tumor necrosis factor. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2631–2641. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberger JS, Sakakeeny MA, Humphries RK, Eaves CJ, Eckner RJ. Demonstration of permanent factor-dependent multipotential (erythroid/neutrophil/basophil) hematopoietic progenitor cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2931–2935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.10.2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene JL, Leytze GM, Emswiler J, Peach R, Bajorath J, Cosand W, Linsley PS. Covalent dimerization of CD28/CTLA-4 and oligomerization of CD80/CD86 regulate T cell costimulatory interactions. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26762–26771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guinn BA, DeBenedette MA, Watts TH, Berinstein NL. 4-1BBL cooperates with B7-1 and B7-2 in converting a B cell lymphoma cell line into a long-lasting antitumor vaccine. J Immunol. 1999;162:5003–5010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guinn BA, Evely RS, Walsh V, Gilkes AF, Burnett AK, Mills KI. An in vivo and in vitro comparison of the effects of b2-a2 and b3-a2 p210BCR-ABL splice variants on murine 32D cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;37:393–404. doi: 10.3109/10428190009089440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guinn BA, Bertram EM, DeBenedette MA, Berinstein NL, Watts TH. 4-1BBL enhances anti-tumor responses in the presence or absence of CD28 but CD28 is required for protective immunity against parental tumors. Cell Immunol. 2001;210:56–65. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirokawa M, Kuroki J, Kitabayashi A, Miura AB. Transmembrane signaling through CD80 (B7-1) induces growth arrest and cell spreading of human B lymphocytes accompanied by protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Immunol Lett. 1996;50:95–98. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(96)02526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu Q, Trevisan M, Xu Y, Dong W, Berger SA, Lyman SD, Minden MD. c-KIT expression enhances the leukemogenic potential of 32D cells. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2530–2538. doi: 10.1172/JCI117954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurtado JC, Kim SH, Pollok KE, Lee ZH, Kwon BS. Potential role of 4-1BB in T cell activation. Comparison with the costimulatory molecule CD28. J Immunol. 1995;155:3360–3367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeannin P, Delneste Y, Lecoanet-Henchoz S, Gauchat JF, Ellis J, Bonnefoy JY. CD86 (B7-2) on human B cells. A functional role in proliferation and selective differentiation into IgE- and IgG4-producing cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15613–15619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim KJ, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C, Merwin RM, Sachs DH, Asofsky R. Establishment and characterization of BALB/c lymphoma cell lines with B cell properties. J Immunol. 1979;122:549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim J, Ogata Y, Feldman RA. Fes tyrosine kinase promotes survival and terminal granulocyte differentiation of factor-dependent myeloid progenitors (32D) and activates lineage-specific transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14978–14984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuchroo VK, Das MP, Brown JA, Ranger AM, Zamvil SS, Sobel RA, Weiner HL, Nabavi N, Glimcher LH. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell. 1995;80:707–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon BS, Kestler DP, Eshhar Z, Oh KO, Wakulchik M. Expression characteristics of two potential T cell mediator genes. Cell Immunol. 1989;121:414–422. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laderach D, Movassagh M, Johnson A, Mittler RS, Galy A. 4-1BB co-stimulation enhances human CD8(+) T cell priming by augmenting the proliferation and survival of effector CD8(+) T cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1155–1167. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee HW, Park SJ, Choi BK, Kim HH, Nam KO, Kwon BS. 4-1BB promotes the survival of CD8+ T lymphocytes by increasing expression of Bcl-xL and Bfl-1. J Immunol. 2002;169:4882–4888. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lenschow DJ, Walunas TL, Bluestone JA. CD28/B7 system of T cell costimulation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:233–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Linsley PS, Brady W, Grosmaire L, Aruffo A, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. Binding of the B cell activation antigen B7 to CD28 costimulates T cell proliferation and interleukin 2 mRNA accumulation. J Exp Med. 1991;173:721–730. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linsley PS, Greene JL, Brady W, Bajorath J, Ledbetter JA, Peach R. Human B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) bind with similar avidities but distinct kinetics to CD28 and CTLA-4 receptors. Immunity. 1994;1:793–801. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(94)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowenberg B, Burnett AK. Acute myeloid leukaemia in adults. In: Degos L, Linch DC, Lowenberg B, editors. Textbook of malignant haematology. London: Martin Dunitz Ltd; 1999. pp. 743–769. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marcucci G, Mrozek K, Bloomfield C. Molecular heterogeneity and prognostic biomarkers in adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics. Curr Opin Hematol. 2005;12:68–75. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000149608.29685.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matulonis U, Dosiou C, Freeman G, Lamont C, Mauch P, Nadler LM, Griffin JD. B7-1 is superior to B7-2 costimulation in the induction and maintenance of T-cell mediated antileukemia immunity: further evidence that B7-1 and B7-2 are functionally distinct. J Immunol. 1996;156:1126–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melero I, Shuford WW, Newby SA, Aruffo A, Ledbetter JA, Hellstrom KE, Mittler RS, Chen L. Monoclonal antibodies against the 4-1BB T-cell activation molecule eradicate established tumors. Nat Med. 1997;3:682–685. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melero I, Bach N, Hellstrom KE, Aruffo A, Mittler RS, Chen L. Amplification of tumor immunity by gene transfer of the co-stimulatory 4-1BB ligand: synergy with the CD28 co-stimulatory pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1116–1121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<1116::AID-IMMU1116>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minami Y, Yamamoto K, Kiyoi H, Ueda R, Saito H, Naoe T. Different antiapoptotic pathways between wild-type and mutated FLT3: insights into therapeutic targets in leukemia. Blood. 2003;102:2969–2975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pollok KE, Kim YJ, Zhou Z, Hurtado J, Kim KK, Pickard RT, Kwon BS. Inducible T cell antigen 4-1BB. Analysis of expression and function. J Immunol. 1993;150:771–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pollok KE, Kim YJ, Hurtado J, Zhou Z, Kim KK, Kwon BS. 4-1BB T-cell antigen binds to mature B cells and macrophages, and costimulates anti-mu-primed splenic B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:367–374. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shahinian A, Pfeffer K, Lee KP, Kundig TM, Kishihara K, Wakeham A, Kawai K, Ohashi PS, Thompson CB, Mak TW. Differential T cell costimulatory requirements in CD28-deficient mice. Science. 1993;261:609–612. doi: 10.1126/science.7688139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shuford WW, Klussman K, Tritchler DD, Loo DT, Chalupny J, Siadak AW, Brown TJ, Emswiler J, Raecho H, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Ledbetter JA, Aruffo A, Mittler RS. 4-1BB costimulatory signals preferentially induce CD8+ T cell proliferation and lead to the amplification in vivo of cytotoxic T cell responses. J Exp Med. 1997;186:47–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suvas S, Singh V, Sahdev S, Vohra H, Agrewala JN. Distinct role of CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the activation of B cell and B cell lymphoma. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7766–7775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson CB, Lindsten T, Ledbetter JA, Kunkel SL, Young HA, Emerson SG, Leiden JM, June CH. CD28 activation pathway regulates the production of multiple T-cell-derived lymphokines/cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1333–1337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vinay DS, Kwon BS. Role of 4-1BB in immune responses. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:481–489. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, Thompson CB, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, Thompson CB, Griesser H, Mak TW. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watts TH, DeBenedette MA. T cell co-stimulatory molecules other than CD28. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(99)80046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weinberg AD, Evans DE, Thalhofer C, Shi T, Prell RA. The generation of T cell memory: a review describing the molecular and cellular events following OX40 (CD134) engagement. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:962–972. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yam PY, Li S, Wu J, Hu J, Zsis JA, Yee JK. Design of HIV vectors for efficient gene delivery into human hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2002;5:479–484. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zennou V, Petit C, Guetard D, Nerhbass U, Montagnier L, Charneau P. HIV-1 genome nuclear import is mediated by a central DNA flap. Cell. 2000;101:173–185. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zufferey R, Donello JE, Trono D, Hope TJ. Woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element enhances expression of transgenes delivered by retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1999;73:2886–2892. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2886-2892.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]