Abstract

The maintenance of peripheral tolerance is largely based on thymus-derived CD4+CD25+ naturally occurring regulatory T cells (Tregs). While on the one hand being indispensable for the perpetuation of tolerance to self-antigens, the immune suppressive properties of Tregs contribute to cancer pathogenesis and progression. Thus, modulation of Treg function represents a promising strategy to support tumor eradication in immunotherapy of cancer. Here, we discuss potential therapeutic applications of our observation that Tregs contain high concentrations of the second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which is transferred from Tregs via gap junctions to suppress the function of T cells and dendritic cells.

Keywords: Regulatory T cells, Dendritic cells, cAMP, Gap junctions, Immune regulation

Introduction

The limited efficacy of chemo- or radiotherapy against neoplasias necessitates the development of complementary therapeutic strategies for treatment. Tumor immunotherapy represents a promising approach as it harnesses the potential of the host immune system to recognize and eradicate transformed cells. Examples for successful immunotherapies are the applications of antibodies specific for target structures on the surface of tumor cells such as Rituximab targeting CD20-expressing lymphomas or trastuzumab against the tumor antigen HER2.

T cell-based immunotherapy, on the other hand, still suffers from a striking discrepancy between the induction of tumor-specific immune responses in experimental settings and therapeutic immunity in clinically relevant conditions. There is broad evidence of the basic ability of T cells to eradicate tumors from various rodent models. Beyond this, the clinical efficacy of T cell therapies in humans is also evident, i.e. by the clearance of tumor cells following donor lymphocyte infusions after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [1]. Toward the mechanisms of recognition of such tumor-specific T cells, a variety of tumor-associated antigens and T cell epitopes have been identified in the past. Nevertheless, their successful application for the induction of objective clinical responses remains a rare event. The reasons for this failure may be due to the fact that tumors have developed immunosuppressive mechanisms to avoid their eradication by the immune system of the host. Mechanisms contributing to the establishment of immune privilege include the downregulation of components of the antigen processing and presentation machinery, the establishment of an unfavorable chemokine/cytokine tumor micro-milieu and the activation of pathways leading to T cell tolerance. The family of regulatory T cells (Tregs) represents one key component of the latter mechanisms. Tregs were shown to inhibit autoimmune diseases by preventing auto-aggressive T cell responses [2]. In this context, Tregs obviously misunderstand developing tumor cells as “self” and consequently inhibit their destruction by T effector cells. Tregs inhibit T cell responses by cell contact-dependent and -independent mechanisms. This review will summarize feature of Tregs recently discovered in our group and will discuss their implications on T cell-based immunotherapies.

Sakaguchi and colleagues [3] described the contribution of Tregs to tumor growth back in 1999. They were able to show that the elimination of “CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory cells” caused regression of transplanted tumors in a CD8+ T cell-dependent manner. This experiment extended the involvement of Tregs in the control of autoimmune diseases to the inhibition of tumor-specific immune responses mediated by cytotoxic T cell responses after depletion of Tregs. Subsequent observations in experimental model systems showed the depletion or functional inactivation of Treg cells by anti-CD25 and/or anti-CD152 mAb [4] or chemotherapeutic agents [5], and did not only allow the spontaneous generation of effective tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells, but also boosted specific T cell responses induced by vaccination leading to enhanced protection against tumors. In the consecutive clinical work up, the occurrence of elevated Treg frequencies in the blood or tumor tissues of patients has been widely described and is associated with tumor progression at numerous occasions. In an extensive study, Curiel et al. [6] reported an inverse correlation of tumor infiltrating Tregs and survival of patients with ovarian carcinoma. Furthermore, the presence of Tregs could be attributed to high levels of CCL22 produced in the tumor tissue and attracting CCR4-expressing Tregs able to inhibit the proliferation of tumor-specific effector T cells in vitro. Thus, the presence of Treg cells at the tumor site might be a major reason why tumor-specific T cells are unable to eradicate their targets despite the fact that they are detectable and functional systemically [7]. These observations might provide one explanation why immunotherapies targeting T cell activation against established tumors have only little success so far.

Another mechanism to overcome the suppressive features of Tregs might be the optimized stimulation of professional antigen presenting cells. This approach, successfully applied by Busch, Fehleisen and Coley more than a century ago despite the complete lack of knowledge about adaptive immunity and immunosuppression, has been revisited by many groups since the identification of TLRs and their ligands. As an example demonstrated, the co-administration of a TLR ligand bypassed Treg-mediated tolerance of tumor-specific T cells in vivo [8]. This has been validated in a more systematic approach by Warger et al. [9] showing that DC activation by TLR ligand combinations overruled the Treg-mediated suppression of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation in vitro. Thereafter, a detailed analysis of the immunosuppressive features of Tregs has been aided by the development of mice allowing the specific elimination of Tregs expressing the diphtheria toxin receptor under the control of the FoxP3 promotor [10]. Treg depletion resulted in the development of autoimmune-like syndromes and contributed to the maintenance of tolerogenic DC phenotype in a IL-10-independent but CTLA4-dependent manner. However, the exact mechanism(s) by which Tregs execute immunosuppression is (are) still elusive. Therefore, the detailed understanding of mechanisms and regulatory network that Tregs are involved in will provide a major advancement in the design of efficient T cell-based immunotherapies.

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is a key component of Treg-mediated suppression

Incipiently, Thornton et al. [11] were able to show in vitro that Treg-mediated suppression of co-cultured conventional CD4+ T cells was not cytokine-mediated, but strictly dependent on cell contact between Tregs and the responder cells. However, up to the present, no membrane bound molecules exclusively expressed by Tregs could be identified, mediating this suppression. Eventually, our own analyses revealed that the suppression of conventional CD4+ T cells by Tregs is substantially based on a transfer of cyclic AMP via gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) [12]. Recently, this finding was further corroborated by Ring et al. [13] showing that GJIC between Tregs and DC in vivo is essential for the suppression of CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, the FoxP3-dependent gene Drosophila Disabled-2 (Dab2) seems to be decisively involved in the suppressive properties of Tregs. Targeted gene ablation of Dab2 not only prevents gap junction formation between Tregs and their responder cells but concomitantly abrogates their suppressive properties [14].

Initially, we performed differential DNA-Microarray analyses comparing the transcriptome of Tregs with CD4+ T cells, Th1 and Th2 cells. One of the most intriguing result of this approach was that the cAMP-cleaving enzyme Phosphodiesterase 3b (PDE3b) is hardly expressed in Tregs when compared to conventional CD4+ T cells. In line with this result, the measurement of cAMP by specific ELISA documented a 20-fold higher intracellular cAMP concentration in Tregs compared to conventional CD4+ T cells—a finding that was recently reconfirmed by Huang et al. [15]. In this report, the authors convincingly show that FoxP3 restricts the expression of the miRNA 142-3p—a microRNA directly targeting the cAMP generating enzyme adenylyl cyclase 9 (ADCY9) mRNA. Interestingly, our further analyses revealed that Tregs harbor high amounts of cAMP in their cytosol. Upon cell contact with Tregs, the amount of intracellular cAMP dramatically rises in the suppressed CD4+ T cells. Moreover, the usage of a cAMP-specific antagonist that blocks the cAMP-mediated activation of the Protein kinase A (PKA) showed that the rising of cAMP in the suppressed CD4+ T cells is decisively involved in the suppressive properties of Tregs. In 1968, Sutherland and co-workers [16] were the first to show a physiological relevance of cAMP, coining the phrase “second messenger” for cAMP. Further analyses proved that cAMP is a potent inhibitor of T cell proliferation and differentiation [17]. Interestingly, the inhibitory capacity of cAMP relies on its ability to shut off Interleukin-2 (IL-2) expression by CD4+ T cells, a capability that was strictly attributed to Tregs [11]. Recently, Bodor and co-workers [18] were able to show that a transcription factor, solely induced by cAMP and termed ICER (inducible cAMP early repressor), is highly expressed in murine Tregs. Furthermore, our own analyses revealed that the expression of this transcriptional repressor is also induced in suppressed CD4+ T cells upon contact with Tregs [12]. Since ICER is capable to bind to NFAT/AP1 sites within the IL-2 promoter [19], it may be concluded that ICER is decisively involved in the inhibition of IL-2 mRNA expression in Tregs as well as in suppressed CD4+ T cells upon contact with Tregs.

Tregs and conventional CD4+ T cells communicate via gap junctions

Still, the question did arise whether and how cAMP can be intercellularly transferred from Tregs to other T cells. Interestingly, it was shown that cAMP is able to trespass from one cell to the other via small channels between cells, termed gap junctions [20]. To test the assumption that cAMP passes over from Tregs to conventional CD4+ T cells during cell contact, we conducted experiments in which the ability of Tregs and conventional CD4+ T cells to communicate via gap junctions was tested. Indeed, these experiments proved that Tregs perform GJIC with co-cultured conventional CD4+ T cells. To further corroborate these findings, GJIC was inhibited using synthetic peptides that mimic connexins and that have been described to specifically interfere with GJIC. One of the most potent synthetic inhibitory peptide is termed GAP27 [21]. This peptide features a sequence identical to a portion of an extracellular loop of Cx43 and therefore interferes with GJIC. The addition of GAP27 to Treg CD4+ T cell co-cultures not only reduced GJIC but also simultaneously abrogated the transfer of cAMP and the suppression of co-cultured CD4+ T cells, underlining the importance of GJIC for cAMP-mediated suppression of conventional CD4+ T cells by Tregs.

In fact, GJIC was not only visualized in vitro but also in vivo by transfer of the vital dye calcein from adoptively transferred Tregs to endogenous CD4+ T cells in a T cell receptor transgenic mouse model. Notably, calcein-transfer from Tregs to CD4+ T cells was only detectable in the draining lymph nodes while in the non-draining lymph nodes despite the presence of calcein-loaded Tregs no transfer to CD4+ T cells was detectable [12]. Obviously, only activated CD4+ T cells and Tregs are qualified to interact with each other by GJIC. To further analyze the suppressed CD4+ T cells ex vivo, endogenous calcein-positive CD4+ T cells from draining lymph nodes—which obviously performed GJIC with Tregs in vivo—were purified by FACS-based cell sorting. Assessment of IL-2 mRNA expression and cytosolic cAMP concentration revealed that indeed calcein-high CD4+ T cells not only harbor high amounts of cAMP but additionally are suppressed in their ability to express IL-2. This oppositional behavior of cAMP content and IL-2 expression clearly indicates that an elevated level of cAMP leads to the inhibition of IL-2 expression and clearly demonstrates that the transfer of cAMP from Tregs to responder cells is crucial for Treg-mediated suppression.

Another explanation for the elevated levels of cAMP in suppressed CD4+ T cells could possibly be given by an adenosine-dependent rising due to A2AReceptor triggering. In this context, Deaglio et al. [22] were able to show that Tregs express the 5′-ectonucleotidases CD73 and the ATPase/ADPase CD39, which crucially contribute to the extracellular generation of adenosine. Therefore, Tregs could potentially involve the adenosinergic pathway in their suppressive action. A detailed view of this interesting mechanism which synergizes with the activation of HIF1α has been presented recently [23].

cAMP and IL-10 coordinately contribute to Treg-mediated suppression of dendritic cells (DCs)

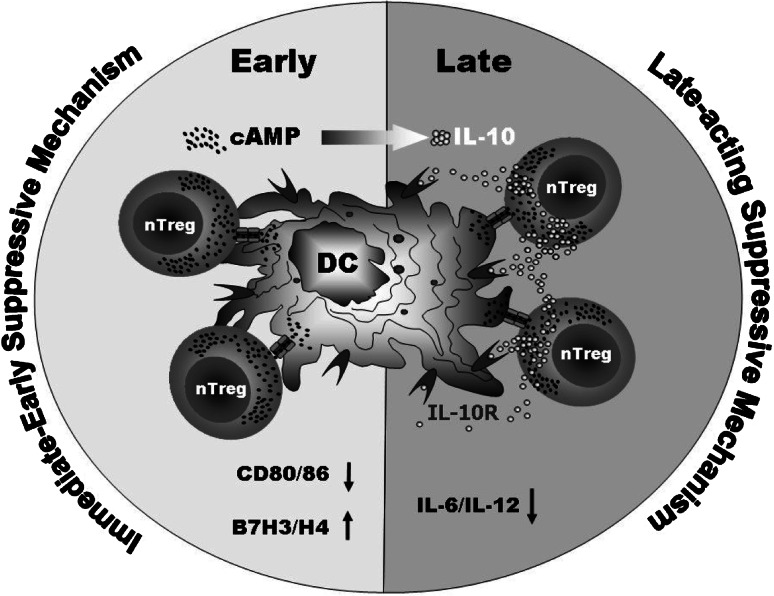

The suppression of conventional T cells by Tregs on a cell to cell basis in vitro is well documented. However, in vivo an intimate interaction of Tregs with DCs was demonstrated using 2-photon-LM [24, 25]. Interestingly, both DCs and T cells are sensitive to cAMP-mediated inhibition. In this context, it was shown that cAMP-elevating agents or cAMP itself are/is able to considerably counteract TLR-mediated activation of DCs [26–28]. Moreover, by inducing IL-10 expression cAMP induces a tolerogenic phenotype upon DC activation [29–31]. Our detailed analyses revealed that Tregs suppress DC by an early transfer of cAMP followed later on by Treg-generated IL-10 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bi-phasic model of Treg-mediated suppression of the co-stimulating function of DCs

Elevation of the cytosolic cAMP levels in DCs by Tregs instantly abrogates the co-stimulatory potency of DCs by impairing the expression of CD80/86 co-stimulators and promoting the upregulation of B7H3/H4 co-suppressors. Moreover, this cAMP-dependent inhibition is subsequently strengthened and further intensified by Treg-derived IL-10 that inhibits cytokine production (IL-6, IL-12) by DCs. Therefore, Tregs use at least two immune suppressive molecules (cAMP, IL-10) in order to inhibit DCs at multiple levels ultimately leading to an inert and suppressive DC phenotype.

Treg-generated cAMP is a major suppressive mechanism of these T cells. Hence, cAMP itself or the catabolism of cAMP represents promising targets for novel immune intervention strategies. Especially, PDE inhibitors that prevent rapid degradation of cAMP should be valuable tools for the improvement of Treg-mediated suppression. Therefore, we analyzed inhibitors of the T cell-specific PDE4 (e.g. Rolipram) in vitro and in vivo [32]. Application of Rolipram in vitro led to an increased concentration of cAMP in Tregs as well as in co-cultured Th2 cells. This further resulted in an increased suppressive capacity of Tregs as indicated by a much stronger inhibition of the Th2-derived cytokine production. In addition, Rolipram was tested in a preclinical model of asthma by transferring OVA-specific Th2 cells alone or in combination with OVA-specific Tregs in T cell-deficient mice. Subsequently, such mice developed severe asthma symptoms when challenged with nebulised OVA. These symptoms were only marginally reduced in the presence of co-transferred Tregs. However, co-administration of Rolipram prevented the appearance of asthma symptoms after co-transfer of Th2 cells and Tregs. If Rolipram was applied in the absence of Tregs, it had no ameliorating effect on Th2-induced asthma. Thus, the Rolipram-mediated increase of the concentration of cAMP in Tregs and suppressed Th2 cells decisively contributes to the strongly enhanced suppressive capacity of the transferred Tregs. This assumption could be confirmed by the reanalysis of transferred lung-resident Tregs and Th2 cells which both harbored strongly elevated concentrations of cAMP ex vivo when the respective mice had been treated with Rolipram. In summary, these data indicate that PDE4 inhibitors can strongly improve the suppressive potency of Tregs by preventing an immediate degradation of cAMP.

Perspectives

Therapeutic intervention strategies based on the modulation of cAMP are already established in the clinics. In this context, PDE inhibitors have been brought in the focus of attention. For instance, highly selective PDE4 inhibitors such as Roflumilast, Cilomilast or Piclamilast have been developed for the treatment of allergic diseases such as Asthma or COPD [33]. Notably, there is growing evidence that cAMP-elevating agents such as the Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) or the PDE inhibitor Pentoxiphyllin have the capability to ameliorate autoimmune diseases by elevating the cAMP content in auto-aggressive CD4+ T cells [34, 35].

Beyond the control of T cell activation in autoimmunity, the modulation of Treg activity may shape anti-tumor T cell responses discriminating between the recognition of host and tumor tissues [36]. The pharmacologic modulation of cAMP levels can induce alloantigen-specific tolerance while allowing other T cell responses in experimental graft versus host disease [37]. Interestingly, in patients with colorectal cancer, Tregs suppress tumor-specific T cell responses by PGE(2) synthesis and cAMP formation which can be reverted by COX-2 inhibition [38]. Along these lines, it was recently observed that the neurotransmitter dopamine was able to reduce the suppressive activity of human Tregs via dopamine type 1 (D1-R and D5-R) receptors [39]. Since the different members of the dopamine receptor family have been shown to modulate the activity of adenylyl cyclase [40], the immunomodulatory activity of different dopamine receptor agonists and antagonists might be in part explainable by influencing the concentration of cAMP in cells of the immune system. Thus, the modulation of cAMP levels may be a promising way to shape adaptive immune responses and new therapeutic strategies to treat cancer, allergic and autoimmune diseases should be developed which directly target cAMP metabolism in cells participating in adaptive immune responses.

Acknowledgments

The work discussed in this review was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant KFO183 to MR and HS, SFB/TR 52 to TB and ES and by the Forschungszentrum Immunologie of the government of the Rhineland Palatinate to HS.

Footnotes

T. Bopp and M. Radsak contributed equally.

E. Schmitt and H. Schild are joint senior authors.

This paper is a Focussed Research Review based on a presentation given at the Seventh Annual Meeting of the Association for Immunotherapy of Cancer (CIMT), held in Mainz, Germany, 3–5 June 2009.

References

- 1.Kolb HJ, Schattenberg A, Goldman JM, Hertenstein B, Jacobsen N, Arcese W, Ljungman P, Ferrant A, Verdonck L, Niederwieser D, van Rhee F, Mittermueller J, de Witte T, Holler E, Ansari H. Graft-versus-leukemia effect of donor lymphocyte transfusions in marrow grafted patients. Blood. 1995;86:2041–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi S, Fujita T, Nakayama E. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, Schumacher TN, Wildenberg ME, Allison JP, Toes RE, Offringa R, Melief CJ. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25(+) regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ercolini AM, Ladle BH, Manning EA, Pfannenstiel LW, Armstrong TD, Machiels JP, Bieler JG, Emens LA, Reilly RT, Jaffee EM. Recruitment of latent pools of high-avidity CD8(+) T cells to the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1591–1602. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, Alvarez X, Cheng P, Mottram P, Evdemon-Hogan M, Conejo-Garcia JR, Zhang L, Burow M, Zhu Y, Wei S, Kryczek I, Daniel B, Gordon A, Myers L, Lackner A, Disis ML, Knutson KL, Chen L, Zou W. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10:942–949. doi: 10.1038/nm1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu P, Lee Y, Liu W, Krausz T, Chong A, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Intratumor depletion of CD4+ cells unmasks tumor immunogenicity leading to the rejection of late-stage tumors. J Exp Med. 2005;201:779–791. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang Y, Huang CT, Huang X, Pardoll DM. Persistent Toll-like receptor signals are required for reversal of regulatory T cell-mediated CD8 tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:508–515. doi: 10.1038/ni1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warger T, Osterloh P, Rechtsteiner G, Fassbender M, Heib V, Schmid B, Schmitt E, Schild H, Radsak MP. Synergistic activation of dendritic cells by combined Toll-like receptor ligation induces superior CTL responses in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:544–550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahl K, Loddenkemper C, Drouin C, Freyer J, Arnason J, Eberl G, Hamann A, Wagner H, Huehn J, Sparwasser T. Selective depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induces a scurfy-like disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204:57–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells suppress polyclonal T cell activation in vitro by inhibiting interleukin 2 production. J Exp Med. 1998;188:287–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bopp T, Becker C, Klein M, Klein-Hessling S, Palmetshofer A, Serfling E, Heib V, Becker M, Kubach J, Schmitt S, Stoll S, Schild H, Staege MS, Stassen M, Jonuleit H, Schmitt E. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate is a key component of regulatory T cell-mediated suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1303–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ring S, Karakhanova S, Johnson T, Enk AH, Mahnke K. Gap junctions between regulatory T cells and dendritic cells prevent sensitization of CD8(+) T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain N, Nguyen H, Friedline RH, Malhotra N, Brehm M, Koyanagi M, Bix M, Cooper JA, Chambers CA, Kang J. Cutting edge: Dab2 is a FOXP3 target gene required for regulatory T cell function. J Immunol. 2009;183:4192–4196. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang B, Zhao J, Lei Z, Shen S, Li D, Shen GX, Zhang GM, Feng ZH. miR-142–3p restricts cAMP production in CD4+CD25− T cells and CD4+CD25+ TREG cells by targeting AC9 mRNA. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:180–185. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robison GA, Butcher RW, Sutherland EW. Cyclic AMP. Annu Rev Biochem. 1968;37:149–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.37.070168.001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kammer GM. The adenylate cyclase-cAMP-protein kinase A pathway and regulation of the immune response. Immunol Today. 1988;9:222–229. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodor J, Fehervari Z, Diamond B, Sakaguchi S. ICER/CREM-mediated transcriptional attenuation of IL-2 and its role in suppression by regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:884–895. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodor J, Habener JF. Role of transcriptional repressor ICER in cyclic AMP-mediated attenuation of cytokine gene expression in human thymocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9544–9551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedner P, Niessen H, Odermatt B, Kretz M, Willecke K, Harz H. Selective permeability of different connexin channels to the second messenger cyclic AMP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6673–6681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans WH, Boitano S. Connexin mimetic peptides: specific inhibitors of gap-junctional intercellular communication. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:606–612. doi: 10.1042/BST0290606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, Friedman D, Usheva A, Erat A, Chen JF, Enjyoji K, Linden J, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK, Strom TB, Robson SC. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sitkovsky MV. T regulatory cells: hypoxia-adenosinergic suppression and re-direction of the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Q, Adams JY, Tooley AJ, Bi M, Fife BT, Serra P, Santamaria P, Locksley RM, Krummel MF, Bluestone JA. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tadokoro CE, Shakhar G, Shen S, Ding Y, Lino AC, Maraver A, Lafaille JJ, Dustin ML. Regulatory T cells inhibit stable contacts between CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2006;203:505–511. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozegbe P, Foey AD, Ahmed S, Williams RO. Impact of cAMP on the T-cell response to type II collagen. Immunology. 2004;111:35–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galgani M, De Rosa V, De Simone S, Leonardi A, D’Oro U, Napolitani G, Masci AM, Zappacosta S, Racioppi L. Cyclic AMP modulates the functional plasticity of immature dendritic cells by inhibiting Src-like kinases through protein kinase A-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32507–32514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403355200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kambayashi T, Wallin RP, Ljunggren HG. cAMP-elevating agents suppress dendritic cell function. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:903–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eigler A, Siegmund B, Emmerich U, Baumann KH, Hartmann G, Endres S. Anti-inflammatory activities of cAMP-elevating agents: enhancement of IL-10 synthesis and concurrent suppression of TNF production. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:101–107. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujita S, Seino K, Sato K, Sato Y, Eizumi K, Yamashita N, Taniguchi M. Regulatory dendritic cells act as regulators of acute lethal systemic inflammatory response. Blood. 2006;107:3656–3664. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hammad H, Kool M, Soullie T, Narumiya S, Trottein F, Hoogsteden HC, Lambrecht BN. Activation of the D prostanoid 1 receptor suppresses asthma by modulation of lung dendritic cell function and induction of regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:357–367. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bopp T, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Klein M, Ullrich N, Stassen M, Schild H, Buhl R, Schmitt E, Taube C. Inhibition of cAMP degradation improves regulatory T cell-mediated suppression. J Immunol. 2009;182:4017–4024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baumer W, Hoppmann J, Rundfeldt C, Kietzmann M. Highly selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors for the treatment of allergic skin diseases and psoriasis. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007;6:17–26. doi: 10.2174/187152807780077318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delgado M, Abad C, Martinez C, Leceta J, Gomariz RP. Vasoactive intestinal peptide prevents experimental arthritis by downregulating both autoimmune and inflammatory components of the disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:563–568. doi: 10.1038/87887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aricha R, Feferman T, Souroujon MC, Fuchs S. Overexpression of phosphodiesterases in experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis: suppression of disease by a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. FASEB J. 2006;20:374–376. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4909fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Drago K, Fathman CG, Strober S, Negrin RS. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Shaughnessy MJ, Chen ZM, Gramaglia I, Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Vogtenhuber C, Palmer E, Grader-Beck T, Boussiotis VA, Blazar BR. Elevation of intracellular cyclic AMP in alloreactive CD4(+) T Cells induces alloantigen-specific tolerance that can prevent GVHD lethality in vivo. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2007;13:530–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.01.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yaqub S, Henjum K, Mahic M, Jahnsen FL, Aandahl EM, Bjornbeth BA, Tasken K. Regulatory T cells in colorectal cancer patients suppress anti-tumor immune activity in a COX-2 dependent manner. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57:813–821. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kipnis J, Cardon M, Avidan H, Lewitus GM, Mordechay S, Rolls A, Shani Y, Schwartz M. Dopamine, through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway, downregulates CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell activity: implications for neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6133–6143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0600-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neve KA, Seamans JK, Trantham-Davidson H. Dopamine receptor signaling. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2004;24:165–205. doi: 10.1081/RRS-200029981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]