Abstract

Despite the significant efforts to enhance immune reactivity against malignancies the clinical effect of anti-tumor vaccines and cancer immunotherapy is still below expectations. Understanding of the possible causes of such poor clinical outcome has become very important for improvement of the existing cancer treatment modalities. In particular, the critical role of HLA class I antigens in the success of T cell based immunotherapy has led to a growing interest in investigating the expression and function of these molecules in metastatic cancer progression and, especially in response to immunotherapy. In this report, we illustrate that two types of metastatic lesions are commonly generated in response to immunotherapy according to the pattern of HLA class I expression. We found that metastatic lesions, that progress after immunotherapy have low level of HLA class I antigens, while the regressing lesions demonstrate significant upregulation of these molecules. Presumably, immunotherapy changes tumor microenvironment and creates an additional immune selection pressure on tumor cells. As a result, two subtypes of metastatic lesions arise from pre-existing malignant cells: (a) regressors, with upregulated HLA class I expression after therapy, and (b) progressors with resistance to immunotherapy and with low level of HLA class I. Tumor cells with reversible defects (soft lesions) respond to therapy by upregulation of HLA class I expression and regress, while tumor cells with structural irreversible defects (hard lesions) demonstrate resistance to immunostimulation, fail to upregulate HLA class I antigens and eventually progress. These two types of metastases appear independently of type of the immunotherapy used, either non-specific immunomodulators (cytokines or BCG) or autologous tumor vaccination. Similarly, we also detected two types of metastatic colonies in a mouse fibrosarcoma model after in vitro treatment with IFN-γ. One type of metastases characterized by upregulation of all MHC class I antigens and another type with partial IFN-γ resistance, namely with lack of expression of Ld-MHC class I molecule. Our observations may shed new light on the understanding of the mechanisms of tumor escape and might have implications for improvement of the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: HLA class I, Metastatic melanoma, Cancer immunotherapy

Introduction

Poor clinical outcome of current protocols of cancer immunotherapy

Cancer still remains to be a leading cause of death in humans with rare tumor regression in response to treatment. It is characterized by metastatic spread in different organs and tissues that actually causes lethal outcome in patients. Usually primary tumors without metastases are removed surgically, while patients with metastatic cancer spread are treated with immunomodulating therapy along with conventional chemotherapy. For many years clinicians used non-specific systemic immunomodulators of anti-tumor immunity, such as BCG [1], IL-2 [2], or IFNs [3] aimed to activate different branches of immune system to fight malignancy. Currently, new immunotherapy protocols are adopted based on the knowledge that T cell mediated response against tumor antigens complexed with HLA class I molecules is a key factor of anti-tumor immune reaction. Identification of various types of tumor associated antigens that are shared by different types of tumor and can be recognized by cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) prompted basic and clinical investigator to develop new peptide-based vaccines aimed to boost specific anti-tumor T cell responses [4]. Most of these vaccines use peptides restricted to by a specific HLA class I allele. Vaccines based on DCs pulsed with tumor-specific peptides or transduced with tumor antigens have also been tested with various degrees of success [5, 6].

Various reports during the past decade indicate that various types of immunomodulators, specific or non-specific, in the majority of clinical trials do not lead to expected clinical improvement in cancer patients. Only in some cases immunotherapy leads to a partial tumor regression or to incomplete elimination of secondary metastases [7, 8]. Paradoxically, immunization-induced CTLs frequently are able to recognize or even eliminate autologous or HLA-matched tumor cells in vitro, but in most of the cases cannot lead to a complete metastatic regression in vivo [9–11]. Thus, the effect of peptide-based immunization is mostly limited to stimulation of anti-tumor cellular immune responses that scarcely lead to a clinical tumor regression. Survival of the patients only slightly improved during the past 20 years. According to Rosenberg et al. [12] cancer immunotherapy demonstrated only 3–4% of overall objective response rate.

It has become obvious that immune-mediated cancer rejection is a complex biological phenomenon that has to be studied more extensively from both sides—the tumor microenvironment and the host immune system. It is established that tumor sites are infiltrated by tumor-specific lymphocytes (TILs) [13]. Nevertheless, tumor growth progresses in these conditions suggesting the role of tumor microenvironment. Emerging evidence suggests that patients’ responsiveness to immunotherapy is influenced by various factors that regulate preexisting immune status and the microenvironment of the primary tumor and of secondary metastatic lesions [14]. Given the low number of cancer patients achieving significant benefit from specific or non-specific immunotherapy, considerable recent effort has focused on identifying predictors of therapeutic response and key molecular mechanisms involved in tumor escape from treatment. Currently, an active intense investigation is ongoing to improve strategies of cancer vaccination and to enhance clinical efficacy of immunization-induced T cell responses [15]. These efforts could be successful if tumor antigens and HLA class I molecules that are necessary for antigen-presentation to CTL would have been normally expressed on malignant cells. It has been described that these molecules are frequently lost or downregulated on tumor cells during cancer progression due to structural or regulatory defects [16, 17].

HLA class I altered expression on cancer cells represents one of the important mechanisms of tumor escape from the immune response that eventually leads to accumulation of new variants with low immunogenicity and high capability for metastatic progression [18–20]. Cancer cells escape from immunosurveillance through the outgrowth of poorly immunogenic tumor cell variants, which emerge due to a growth advantages created by a combination of certain features of tumor cells and the factors of tumor environment [21]. Total or partial loss of HLA class I expression has been described in almost all types of cancer and in some cases it has been associated with poor clinical prognosis [17, 21, 22]. Interestingly, it has been recently reported that patients with HLA class I positive bladder cancer had longer recurrence-free survival after BCG therapy than those with negative expression in 5-year-follow-up [23]. Cells that are highly immunogenic and express high levels of MHC class I are eliminated by CTLs. Malignant cells with total MHC class I loss are susceptible to NK cell lysis because of inactivation of KIRs. However, frequently a complex balance between activating and inhibiting signals in NK cells leads to failure of natural cytotoxic reactions against malignant cells. Another immunoselection route might be provided by the partial loss of HLA class I antigens that allows tumor cells to escape both CTL and NK attack. For instance, a recent study of colorectal cancer showed that a high level of HLA I expression or total loss of HLA class I was associated with similar disease-specific survival times, possibly due to T cell reactivity or NK cell-mediated clearance of class I-positive and -negative tumor cells, respectively. However, tumors with intermediate HLA class I expression were reported to be associated with a poor prognosis, suggesting that these tumors may avoid both NK- and T cell-mediated immune surveillance [24].

It has been known for many years that changes in MHC class I profile affects the metastatic capacity. In particular, several reports from Dr. Feldman′s group published in the 1980s indicate that high and low metastatic phenotypes in a mouse tumor mode are associated with defined MHC class I expression [25, 26]. It has been also demonstrated in various types of cancer that metastatic lesions are less sensitive to CTL killing than a primary tumor indicating that during tumor progression metastatic cancer cells may acquire various characteristics that help to evade CTL mediated destruction [7]. Metastatic progression has been demonstrated to correlate with HLA class I downregulation in breast carcinoma [27]. Decreased expression of HLA heavy chain and beta2-microglobulin mRNA was found in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma [28]. Therefore, it is much more complicated to treat metastatic disease that localized cancer. Thus, the complex nature of tumor metastasis necessitates a comprehensive approach to achieve successful immune intervention. There have been various reports demonstrating that different metastases in the same patient have various mechanisms that underlie the generation of tumor escape variants and the existing immunophenotypes of metastatic lesions [29, 30]. However, there is not sufficient data on a correlation between HLA expression and advancement of metastatic lesions, as well as changes in this expression in response to immunotherapy, since it is not always possible to obtain primary tumor and several metastatic samples from cancer patients during immunotherapy.

In this report based on analysis of metastases in cancer patients and from animal studies we classified metastatic lesions that develop under immunotherapy regimen in two groups: progressing with reduced HLA class I expression and regressing with normal expression of class I antigens.

Identification of two types of metastatic melanoma lesions based on different HLA class I expression: implications for cancer immunotherapy

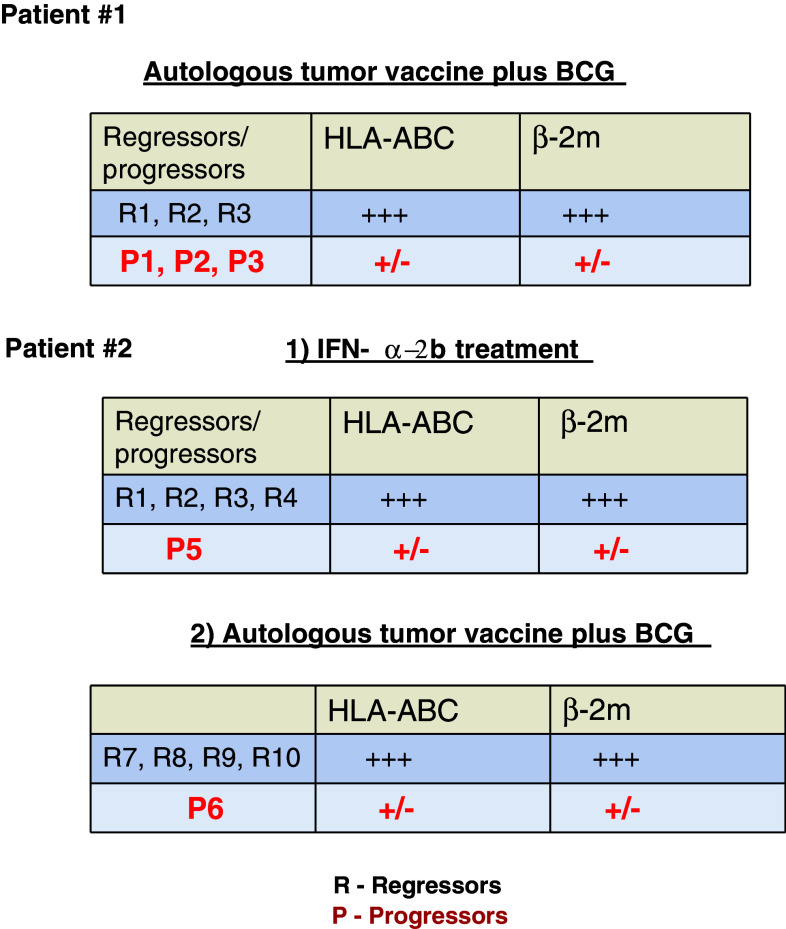

Recently, we have observed an interesting association of HLA class I expression and metastatic progression in two melanoma patients, whose subcutaneous metastases responded differently to autologous tumor cell vaccination [31, 32]. In both patients, we were able to obtain and analyze both progressing and regressing metastatic lesions for HLA class I expression using immunohistochemistry, tissue microdissection, LOH analysis, and other molecular techniques. Figure 1 summarizes the immunohistochemical characteristics of the HLA class I expression in the studied metastatic lesions from both patients. In the first patient we analyzed three progressing (P1, P2, P3) and three regressing (R1, R2, R3) metastases obtained after treatment with autologous tumor vaccine combined with BCG. We observed that the progressing lesions have low transcription and protein expression levels of HLA class I heavy chain and beta2-microglobulin, and demonstrate higher frequency of LOH in chromosome 15 [31]. Malignant cells with such irreversible structural genetic defects in HLA class I are not likely to respond to immunotherapy aimed at enhancing anti-tumor T cell immune response and will generate a progressing type of metastases. In regressing lesions the expression level of class I molecules was significantly higher. LOH at chromosome 6 was detected in all six studied metastases, suggesting that this defect may also be found in the primary tumor, contributing to the mechanism of tumor escape and metastatic progression. Real-time quantitative PCR of the samples obtained from microdissected tumor showed lower mRNA levels of HLA-ABC heavy chain and β2 m in progressing metastases than in regressing ones, confirming the immunohistological findings.

Fig. 1.

HLA class I expression in progressing/regressing metastases after immunotherapy of two melanoma patients

In a second patient (Patient #2) we analyzed ten metastases: five after treatment with IFN-α-2b (four regressing ones, R1, R2, R3, R4; and one progressing one, P5) and five after autologous vaccine (M-VAX) plus BCG (four regressing ones, R7,R8,R9,R10; and one progressor, P6). We observed once again a positive correlation between low HLA class I expression and metastatic progression independently of the type of therapy used. Accordingly, after immunotherapy metastatic lesions can be classified in two types: regressors with high expression of HLA class I molecules and progressors with low class I expression. We favor an idea that immunotherapy leads to modulation of HLA class I expression on different tumor cells subsets and leads to emergence of different responders to treatment based on preexisting “soft” or “hard” HLA alterations. It is expected that malignant cells with irreversible “hard” genetic defects in HLA class I genes will not respond to immune modulation by upregulation of HLA class I molecules.

Melanoma is characterized by diversity of malignant cells in many ways. It has been shown that metastases also differ and respond differently to treatment. Thus, the treatment leads to regression of some metastases. There are some factors that make cancer cells susceptible in a subpopulation with specific characteristics. Based on our observations we think that these characteristics include HLA class I expression and its modulation in response to cytokine stimuli.

We cannot totally exclude a possibility that progression and regression of certain metastatic lesion happened independently of the therapy. However, we believe that immunotherapy put an additional immunoselective pressure leading to emergence of highly proliferating metastatic cells with preexisting defect in HLA class I expression. From our animal studies we obtained evidence supporting our hypothesis.

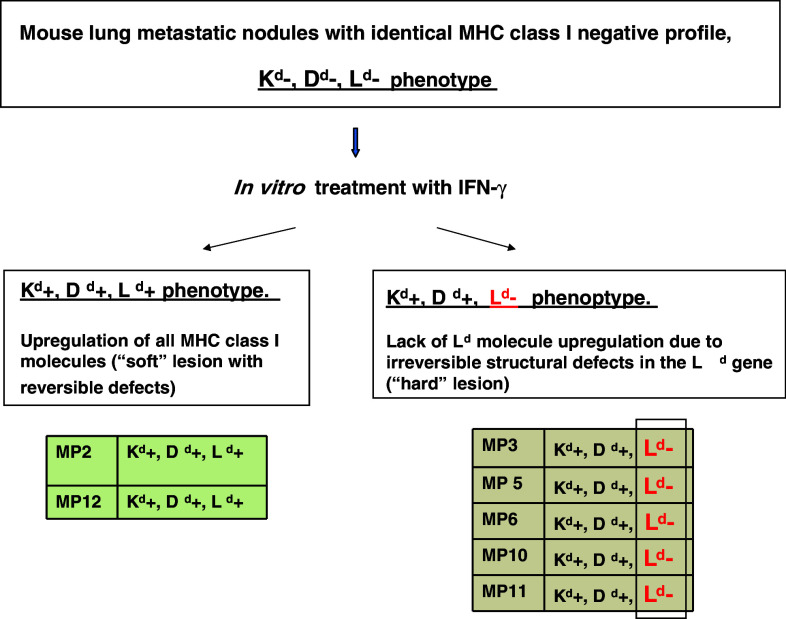

Two types of metastases found in a mouse fibrosarcoma model

Earlier, we also identified two H-2 metastatic phenotypes in a murine cancer model [33]. Briefly, one H-2-class I-negative fibrosarcoma tumor clone generated H-2 class I-negative spontaneous lung metastases in immunocompetent BALB/c mice [34–36]. Cell lines from these metastatic nodes with apparently identical MHC class I expression pattern generated two distinct and reproducible H-2 phenotypes after in vitro IFN-γ treatment. The first (17%) was similar to that of the B9 tumor clone from which they derived and was characterized by the cell surface expression of Kd, Dd or Ld molecules. The second type of MHC expression profile was present in 83% of the colonies and was characterized by absence of expression of Ld class I molecule after IFN-γ treatment (Fig. 2). Therefore, vitro incubation of the metastatic clones with IFN-γ revealed a presence of non-responder cells to cytokine stimulation. We believe that the second type of metastatic clone with “hard” lesion in MHC Ld gene would eventually give rise to a progressor type of metastatic lesion. This altered phenotype was highly reproducible and repeated in different metastases from different animals and in different experiments, suggesting that MHC genetic alterations observed in a given metastasis are non-random and can be predicted [33]. The loss of expression of the Ld antigen was originated as a consequence of two independent events: at first a deletion of a large fragment of one chromosome 17 telomeric to Dd genes that had been found in the primary tumor and in all the metastatic clones, and secondly a new deletion involving only the Ld gene of the other chromosome 17 that had been detected in metastatic clones with no Ld expression. For details see reference [33].

Fig. 2.

Two types of mouse metastatic clones generated after in vitro IFN-γ treatment: one with up-regulated cell surface expression of Kd, Dd and Ld molecules (Kd+, Dd+, Ld+) a, and second one with the absence of Ld expression (Ld −) b. The lack of IFN-γ inducibility is due to the existence of an underlying structural irreversible defect in the Ld gene

Discussion and conclusions

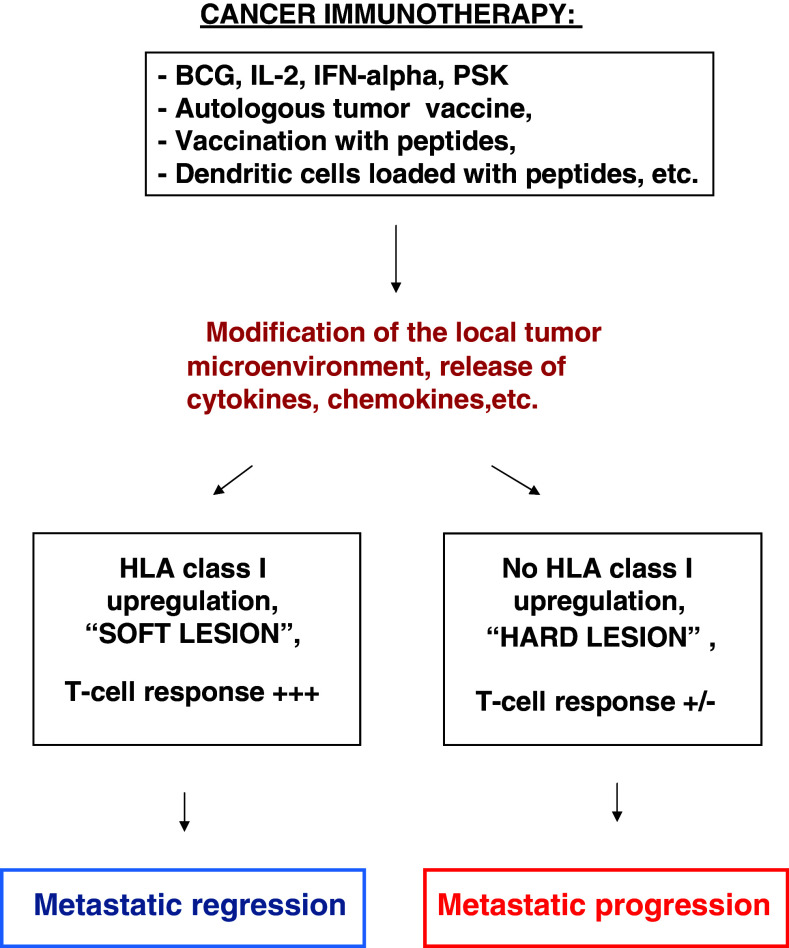

Based on the data obtained from our animal experiments and clinical cases, we have identified two types of metastases according to the expression pattern of HLA class I antigens: progressing metastatic lesions with low HLA class I level and regressing ones with upregulated expression of these antigens. Our observations suggest that no matter what type of immunotherapy is administered, specific immunization or systemic immune stimulation, the outcome should be expected the same, namely, a modification of tumor microenvironment of each metastatic lesion leading to a release of immunostimulating cytokines. Depending on the preexisting HLA class I expression level and presence of reversible (“soft”) or irreversible (“hard”) alterations in the HLA class I system, its expression will be either upregulated by the cytokines leading to regression of metastatic nodule, or remained unchanged due to resistance to cytokine treatment which will stimulate progression of metastases with irreversible HLA class I alterations (Fig. 3). In some cases additional structural defects in molecules involved in MHC class I transcriptional activation could limit the response of metastases to immunotherapy. For example, STAT-1 protein, that plays an important role in IFN-γ-mediated HLA class I upregulation could be absent or not phosphorilated, or have irreversible structural defects [37, 38]. Our data could at least partially explain why despite the constant improvement of existing protocols of cancer immunotherapy the clinical efficacy remains to be low. Among other possible explanations could be a loss of tumor antigens that would lead to the lack of recruitment of tumor specific CD8+ cells to the site of metastatic lesion [39] or induction of a T cell anergy in these cells. An extrinsic mechanism could be the induction of strong local Treg response that would inhibit IFN-γ production by tumor specific CD8+ cells thereby leading to failure in HLA class I upregulation and to inhibition of the downstream effector processes that cause tumor regression [40].

Fig. 3.

Proposed mechanism of immunotherapy-mediated generation of progressing and regressing metastases

Metastatic melanoma consists of a heterogeneous population of cells with respect to gene and protein expression, including HLA class I antigens that may be of importance to disease progression [30, 41, 42]. Even if tumor specific antigen is present and CTL response is activated by vaccination, absence or low level of HLA class I allele necessary for presentation prevents tumor elimination.

Interestingly, in many cases peptide-based vaccination produces mixed responses in the same melanoma patients: regression of some malignant lesions and progression of others. Melanoma patients vaccinated with MAGE-3 peptides, or with autologous DC pulsed with MAGE-3 peptides, or with ALVAC virus encoding MAGE antigens demonstrated a mixed clinical response to treatment, with some metastases regressing while others progressing [8, 43, 44]. Currently, there is no clear explanation for this diversity of responses. Interestingly, in some patients this treatment triggers a strong activation of T cells against non-vaccine tumor peptide, or epitope spreading. Both vaccine-specific and new CTLs were detected at tumor sites even in progressing lesions suggesting that their activity was not sufficient for killing of the metastatic cells [45, and Dr. D. Godelaine, personal communication]. One possible explanation of the inability of CTLs to destroy tumor cells is failure of HLA class I upregulation on metastatic cells in response to immunomodulation. It is believed that in case of epitope spreading the recognition of an antigen on a target cell by T cells generates conditions such as cytokine release and target cell destruction, which in turn, facilitates the presentation of additional antigens of the target cells. Similar phenomenon of T cell response shifting has been previously described in other reports on melanoma patients [46]. We believe that our observations support the idea that cytokine release at the tumor site may lead to upregulation of HLA class I expression necessary for presentation of newly released tumor antigens or of peptides that previously lacked appropriate HLA class I allele for adequate presentation to T cells. However, such HLA upregulation would not be possible if malignant cells contain irreversible structural alterations in HLA class I genes or demonstrate resistance to cytokine-mediated upregulation due to defects in signal transduction pathways.

Therefore, taken together, these data supports our working hypothesis that the mixed response to immunotherapy in melanoma patients is predetermined by the presence of irreversible “hard” structural defects in HLA class I expression, which would give rise to progressing lesions.

Hence, to optimize cancer immunotherapy strategies evasion from newly developed immunoresistant tumor phenotypes needed to be considered. Monitoring HLA class I expression in metastatic lesions during course of cancer immunotherapy may help to identify immunoresistant lesions and predict, or even improve, the clinical outcome of treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS), Red Genomica del Cancer (RETIC RD 06/0020), Plan Andaluz de Investigacion (Group CTS-143), Consejeria Andaluz de Salud (SAS), Proyecto de Excelencia de Consejeria de Innovacion (CTS-695), Proyecto de investigacion I+D (SAF 2007-63262) in Spain; and from the Integrated European Cancer Immunotherapy project (OJ2004/C158, 518234).

Footnotes

This article is a symposium paper from the conference “Progress in vaccination against cancer 2007 (PIVAC 7)”, held in Stockholm, Sweden, on 10–11 September 2007.

References

- 1.Herr HW, Laudone VP, Badalament RA, Oettgen HF, Sogani PC, Freedman BD, Melamed MR, Whitemore WF., Jr Bacillus Calmette–Guérin therapy alters the progression of superficial bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6(9):1450–1455. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.9.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, Weber JS, Parkinson DR, Seipp CA, Einhorn JH, White DE. Treatment of 283 consecutive patients with metastatic melanoma or renal cell cancer using high-dose bolus interleukin. JAMA. 1994;271(12):907–913. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.12.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atzpodien J, Korfer A, Palmer PA, Franks CR, Poliwoda H, Kirchner H. Treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer patients with recombinant subcutaneous human interleukin-2 and interferon-alpha. Ann Oncol. 1990;1(5):377–378. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a057779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Bruggen P, Traversari C, Chomez P, Lurquin C, De Palen E, Van den Eynde B, Knuth A, Boon T. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science. 1991;254(5038):1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1840703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esche C, Shurin MR, Lotze MT. The use of dendritic cells for cancer vaccination. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 1999;1:72–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godelaine D, Carrasco J, Lucas S, Karanikas V, Schuler-Thurner B, Coulie PG, Schuler G, Boon T, Pel A. Polyclonal CTL responses observed in melanoma patients vaccinated with dendritic cells pulsed with a MAGE-3.A1 peptide. J Immunol. 2003;171(9):4893–4897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:175–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruit WH, van Ojik HH, Brichard VG, Escudier B, Dorval T, Patel P, van Baren N, Avril MF, Piperno S, Khammari A, Stas M, Ritter G, Lethe B, Godelaine D, Brasseur F, Zhang Y, van der Bruggen P, Boon T, Eggermont AM, Marchand M. Phase 1/2 study of subcutaneous and intradermal immunization with a recombinant MAGE-3 protein in patients with detectable metastatic melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(4):596–604. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg SA, Sherry RM, Morton KE, Scharfman WJ, Yang JC, Topalian SL, Royal RE, Kammula U, Restifo NP, Hughes MS, Schwartzentruber D, Berman DM, Schwarz SL, Ngo LT, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Steinberg SM. Tumor progression can occur despite the induction of very high levels of self/tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in patients with melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;175(9):6169–6176. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anichini A, Vegetti C, Mortarini R. The paradox of T-cell-mediated antitumor immunity in spite of poor clinical outcome in human melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53(10):855–864. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0526-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang E, Phan GQ, Marincola FM. T-cell-directed cancer vaccines: the melanoma model. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2001;1(2):277–290. doi: 10.1517/14712598.1.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):909–915. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlechnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoue F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pages F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313(5795):1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang E, Miller LD, Ohnmacht GA, Mosellin S, Perez-Diez A, Petersen D, Zhao Y, Simon R, Powell JI, Asaki E, Alexander HR, Duray PH, Herlyn M, Restifo NP, Liu ET, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM. Prospective molecular profiling of melanoma metastases suggests classifiers of immune responsiveness. Cancer Res. 2002;62(13):3581–3586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berzofsky JA, Terabe M, Oh S, Belyakov IM, Ahlers JD, Janik JE, Morris JC. Progress on new vaccine strategies for the immunotherapy and prevention of cancer. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(11):1515–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI21926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F, Cabrera T, Perez-Villar JJ, Lopez-Botet M, Duggan-Keen M, Stern P. Implications for immunosurveillance of altered HLA class I phenotypes in human tumours. Immunol Today. 1997;18(2):89–95. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(96)10075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aptsiauri N, Cabrera T, Garcia-Lora A, Lopez-Nevot MA, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. MHC class I antigens and immune surveillance in transformed cells. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;256:139–189. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)56005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrido F, Cabrera T, Concha A, Glew S, Ruiz-Cabello F, Stern PL. Natural history of HLA expression during tumour development. Immunol Today. 1993;14:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90264-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CC, Ferrone S. Immune selective pressure and HLA class I antigen defects in malignant lesions. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(2):227–236. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0183-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrido F, Algarra I. MHC antigens and tumor escape from immune surveillance. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;83:117–158. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(01)83005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seliger B, Cabrera T, Garrido F, Ferrone S. HLA class I antigen abnormalities and immune escape by malignant cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12(1):3–13. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolland P, Deen S, Scott I, Durrant L, Splendlove I. Human leukocyte antigen class I antigen expression is an independent prognostic factor in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(12):3591–3596. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamura H, Torigoe T, Honma I, Sato E, Asanuma H, Hirohashi Y, Sato N, Tsukamoto T. Effect of human leukocyte antigen class I expression of tumor cells on outcome of intravesical instillation of bacillus calmette–guerin immunotherapy for bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4641–4644. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson NF, Ramage JM, Madjd Z, Splendlove I, Ellis IO, Scholefield JH, Durrant LG. Immunosurveillance is active in colorectal cancer as downregulation but not complete loss of MHC class I expression correlates with a poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(1):6–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Baetselier P, Katzav S, Gorelik E, Feldman M, Segal S. Differential expression of H-2 gene products in tumour cells in associated with their metastatogenic properties. Nature. 1980;288(5787):179–181. doi: 10.1038/288179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenbach L, Hollander N, Greenfield L, Yakor H, Segal S, Feldman M. The differential expression of H-2 K versus H-2D antigens, distinguishing high-metastatic from low-metastatic clones, is correlated with the immunogenic properties of the tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 1984;34(4):567–573. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910340421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saio M, Teicher M, Campbell G, Feiner H, Delgado Y, Frey AB. Immunocytochemical demonstration of down regulation of HLA class-I molecule expression in human metastatic breast carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21(3):243–249. doi: 10.1023/B:CLIN.0000037707.07428.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero JM, Aptsiauri N, Vazquez F, Cozar JM, Canton J, Cabrera T, Tallada M, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. Analysis of the expression of HLA class I, proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in primary tumors from patients with localized and metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Tissue Antigens. 2006;68(4):303–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2006.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendez R, Ruiz-Cabello F, Rodriguez T, Del Campo A, Paschen A, Schedendorf D, Garrido F. Identification of different tumor escape mechanisms in several metastases from a melanoma patient undergoing immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(1):88–94. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang CC, Campoli M, Restifo NP, Wang X, Ferrone S. Immune selection of hot-spot beta 2-microglobulin gene mutations, HLA-A2 allospecificity loss, and antigen-processing machinery component down-regulation in melanoma cells derived from recurrent metastases following immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2005;174(3):1462–1471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cabrera T, Lara E, Romero JM, Maleno I, Real LM, Ruiz-Cabello F, Valero P, Camacho FM, Garrido F. HLA class I expression in metastatic melanoma correlates with tumor development during autologous vaccination. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56(5):709–717. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0226-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carretero R, Romero JM, Ruiz-Cabello F, Maleno I, Rodríguez F, Camacho FM, Real LM, Garrido F, Cabrera T (2008) Analysis of HLA class I expression in progressing and regressing metastatic melanoma lesions after immunotherapy. Immunogenetics (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Garcia-Lora A, Algarra I, Gaforio JJ, Ruiz-Cabello F, Garrido F. Immunoselection by T lymphocytes generates repeated MHC class I-deficient metastatic tumor variants. Int J Cancer. 2001;91(1):109–119. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010101)91:1<109::AID-IJC1017>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrido A, Perez M, Delgado C, Garrido ML, Rojano J, Algarra I, Garrido F. Influence of class I H-2 gene expression on local tumor growth. Description of a model obtained from clones derived from a solid BALB/c tumor. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1986;3(2):98–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez M, Algarra I, Ljunggren HG, Mialdea MJ, Gaforio JJ, Klein G, Karre K, Garrido F. A weakly tumorigenic phenotype with high MHC class-I expression is associated with high metastatic potential after surgical removal of the primary murine fibrosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 1990;46(2):258–261. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Algarra I, Gaforio JJ, Garrido A, Mialdea MJ, Perez M, Garrido F. Heterogeneity of MHC-class-I antigens in clones of methylcholanthrene-induced tumors. Implications for local growth and metastasis. Int J Cancer (suppl) 1991;6:73–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez T, Mendez R, Del Campo A, Jiménez P, Aptsiauri N, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. Distinct mechanisms of loss of IFN-gamma mediated HLA class I inducibility in two melanoma cell lines. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abril E, Mendez R, Garcia A, Serrano A, Cabrera T, Garrido F, Ruiz-Cabello F. Characterization of a gastric tumor cell line defective in MHC class I inducibility by both alpha- and gamma-interferon. Tissue Antigens. 1996;47(5):391–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khong HT, Wang QJ, Rosenberg SA. Identification of multiple antigens recognized by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from a single patient: tumor escape by antigen loss and loss of MHC expression. J Immunother. 2004;27(3):184–190. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200405000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. Immunoregulatory T cells in tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(2):157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vries TJ, Fourkour A, Wobbes T, Verkroost G, Ruiter DJ, Muijen GN. Heterogeneous expression of immunotherapy candidate proteins gp100, MART-1, and tyrosinase in human melanoma cell lines and in human melanocytic lesions. Cancer Res. 1997;57(15):3223–3229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bittner M, Metzer P, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Seftor E, Hendrix M, Radmacher M, Simon R, Yakini Z, Ben-dor A, Sampas N, Dougherty E, Wang E, Marincola F, Gooden C, Lueders J, Glatfelter A, Pollock P, Carpten J, Gillanders E, Leja D, Dietrich K, Beaudry C, Berens M, Alberts D, Sondak V. Molecular classification of cutaneous malignant melanoma by gene expression profiling. Nature. 2000;406(6795):536–540. doi: 10.1038/35020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thurner B, Haendle I, Roder C, Dieckmann D, Keikavoussi P, Jonuleit H, Bender A, Maczek C, Schreiner D, von den Driesch P, Brocker EB, Steinman RM, Enk A, Kampgen E, Schuler G. Vaccination with mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J Exp Med. 1999;190(11):1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Baren N, Bonnet MC, Dreno B, Khammari A, Dorval T, Piperno-Neumann S, Lienard D, Speiser D, Marchand M, Brichard VG, Escudier B, Negries S, Dietrich PY, Maraninchi D, Osanto S, Meyer RG, Ritter G, Maingeon P, Tarlaglia J, van der Bruggen P, Coulie PG, Boon T. Tumoral and immunologic response after vaccination of melanoma patients with an ALVAC virus encoding MAGE antigens recognized by T cells. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(35):9008–9021. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lurquin C, Lethe B, De Plaen E, Corbiere V, Theate I, van Baren N, Coulie PG, Boon T. Contrasting frequencies of antitumor and anti-vaccine T cells in metastases of a melanoma patient vaccinated with a MAGE tumor antigen. J Exp Med. 2005;201(2):249–257. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamshikov GV, Mullins DW, Chang CC, Ogino T, Thompson L, Presley J, Galavotti H, Aquila W, Deacon D, Ross W, Patterson JW, Engelhard VH, Ferrone S, Slingluff CL., Jr Sequential immune escape and shifting of T cell responses in a long-term survivor of melanoma. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):6863–6871. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]