Abstract

Background: Ovarian cancer commonly relapses after remission and new strategies to target microscopic residual diseases are required. One approach is to activate tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells with dendritic cells loaded with tumor cells. In order to enhance their immunogenicity, ovarian tumor cells (SK-OV-3, which express two well-characterized antigens HER-2/neu and MUC-1) were killed by oxidation with hypochlorous acid (HOCl). Results: Treatment for 1 h with 60 μM HOCl was found to induce necrosis in all SK-OV-3 cells. Oxidized, but not live, SK-OV-3 was rapidly taken up by monocyte-derived dendritic cells, and induced partial dendritic cell maturation. Dendritic cells cultured from HLA-A2 healthy volunteers were loaded with oxidized SK-OV-3 (HLA-A2−) and co-cultured with autologous T cells. Responding T cells were tested for specificity after a further round of antigen stimulation. In ELISPOT assays, T cells produced interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in response to the immunizing cellular antigen, and also to peptides coding for MUC-1 and HER-2/neu HLA-A2 restricted epitopes, demonstrating efficient cross-presentation of cell-associated antigens. In contrast, no responses were seen after priming with heat-killed or HCl-killed SK-OV-3, indicating that HOCl oxidation and not cell death/necrosis per se enhanced the immunogenicity of SK-OV-3. Finally, T cells stimulated with oxidized SK-OV-3 showed no cross-reaction to oxidized melanoma cells, nor vice versa, demonstrating that the response was tumor-type specific. Conclusions: Immunization with oxidized ovarian tumor cell lines may represent an improved therapeutic strategy to stimulate a polyclonal anti-tumor cellular immune response and hence extend remission in ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Ovarian carcinoma, Dendritic cells, Hypochlorous acid, HER-2/neu, MUC-1

Introduction

Advanced ovarian carcinoma commonly relapses after remission due to the growth of residual microscopic tumors. New therapeutic strategies are urgently needed to target this disease. Compelling evidence from animal studies [2, 11, 25, 31] and clinical trials [8, 13, 14] have underlined the importance of the immune system in controlling ovarian malignancies. In particular, the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) expressing anti-tumor interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) within advanced ovarian tumors was correlated with a significant prolongation of survival [32]. The identification of overexpressed ovarian tumor-associated antigens—HER-2/neu and MUC-1—and several of their MHC class-I restricted epitopes has given further impetus to the development of tumor immunotherapy for this disease.

Immunotherapy using dendritic cells (DCs) to activate tumor-specific T cells is a potentially powerful approach. DCs are the key antigen-presenting cells of the immune system that initiate, regulate, and activate both helper (Th) and cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses against tumors. Several studies have shown that vaccinating ovarian cancer patients with autologous DCs pulsed with immunodominant HER-2/neu or MUC-1 peptides elicited peptide-specific CD8+ T cell immunity [5, 9, 20]. Immunization with multiple antigens, however, or even with whole ovarian tumor cells may drive a much stronger overall CD4 as well as CD8 immune response, and will diminish the chance of driving the emergence of escape mutations in the tumor cells. Live ovarian tumour cells are poorly immunogenic, and cannot be used as immunogens in vivo. A strategy to kill ovarian tumour cells and at the same time enhance their immunogenicity is therefore required.

Hypochlorous acid (HOCl) is a potent oxidant formed from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and chloride ion (Cl−) in a reaction catalyzed by the neutrophil enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO) during acute inflammation. As well as showing strong microbicidal activity, HOCl has been shown to enhance the immunogenicity of protein antigens by several folds via oxidation in vivo and ex vivo [1, 17, 18]. Proteins oxidized by HOCl were more readily taken up and processed by antigen-presenting cell (APC) and led to enhanced activation of antigen-specific T cells in vitro. Myeloperoxidase activity therefore acts as a link between the innate immune response and the induction of adaptive immunity [16]. This study is the first to explore the link between oxidation and immunity in the context of a tumor model.

The study tests the hypothesis that allogeneic ovarian tumor cells, SK-OV-3, oxidized by HOCl become potent immunogens that are efficiently taken up and cross-presented by DCs to stimulate autologous tumor-specific T cell responses. An in vitro human priming model was used to demonstrate that HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 tumor cells were readily phagocytosed by DCs and induced the expansion and differentiation of T cells that recognized not only the oxidized tumor cells but also the ovarian-associated tumor antigens HER-2/neu and MUC-1. These T cells recognize antigens in the context of the HLA of the stimulating DC and could therefore be of therapeutic value in the ovarian cancer setting.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

The following Abs were used: (a) CD1a (supernatant mouse MoAb NA1/34, IgG2a) was a gift from Professor A. McMichael (John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, UK); (b) CD2 (mouse MoAb MAS 593, IgG2b; Harlan Sera-Lab, Loughbourough, UK); (c) CD3 (supernatant mouse MoAb UCH T1, IgG1); (d) CD14 (supernatant mouse MoAb HB246, IgG2b); (e) HLA-DR (supernatant mouse MoAb L243, IgG2a) were gifts from Professor P.C.L. Beverley (The Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research, Berkshire, UK); (f) CD19 (supernatant mouse MoAb BU12, IgG1); (g) CD86 (supernatant mouse MoAb BU63, IgG1) were gifts from D. Hardie (Birmingham Medical School, Birmingham, UK); (h) CD40 (mouse MoAb 5C3, IgG1; eBioscience, San Diego, CA); (i) CD83 (mouse MoAb HB15e, IgG1; eBioscience, San Diego, CA); (j) HLA-ABC (mouse MoAb W6/32 IgG2a; SeroTec, Kidlington, Oxford, UK); and (k) IgG2a isotype control (Dako A/S). The secondary antibody for flow cytometry was rabbit anti-mouse FITC-conjugated (Dako Cytomation, Denmark) at a 1:20 dilution of a 0.3 mg/ml stock to give a final concentration of 15 μg antibody/106 cells.

Synthetic peptides and HER-2/neu pentamers

The HLA-A*0201-restricted peptides derived from HER-2/neu (E75:KIFGSLAFL, GP2:IISAVVGIL) [10, 23], MUC-1 (M1.1: STAPPVHNV, M1.2: LLLLTVLTV) [4], and melanoma (MART-1: ELAGIGILTV) were purchased from Alpha Diagnostic International (San Antonio, Texas, USA). Purity was >79% as indicated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry. The lyophilized peptides were dissolved in at least 50% dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) plus hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) to a concentration of 1 mM, filter-sterilized with 0.2 μm filter and stored at −80°C. The HLA-A*0201-resticted HER-2/neu (specific for KIFGSLAFL) PE-conjugated pentamer was purchased from ProImmune (Oxford, UK).

Tumor cell lines

The carcinoma ovarian SK-OV-3 (HLA-A3+, A2−, HER-2/neu +, MUC1+) and breast SK-BR-3 (HER-2/neu +, MUC1+) and MDA-231 (HLA-A2+, HER-2/neu +, MUC1+) cell lines were kind gifts from Dr M. O’Hare (Ludwig Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK). The above cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (complete DMEM) (all from Cancer Research, London, UK). Melanoma tumor cell lines MEL-11 (HLA-A2−, MART-1+) and MEL-12 (HLA-A2+, MART-1+) [21] were gifts from Dr L. Lopes (Department of Immunology and Molecular Pathology, UCL, London, UK) and maintained in complete DMEM. All cell lines were tested regularly for mycoplasma and found to be negative.

Western blot

SK-OV-3 ovarian tumor cells were washed twice with HBSS and lysed in sample buffer (0.5 M Tris pH 6.8, 1% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol). The cell lysates were boiled for 3 min at 100°C. A total of 1×106 tumor cells per sample was resolved on 7.5% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, UK). The presence of cellular HER-2/neu and MUC1 glycoproteins were detected by using anti-HER-2/neu (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and HMFG2 anti-MUC-1 monoclonal antibodies (reactive with Asp-Thr-Arg, gift from Dr Joyce Taylor-Papadimitriou, Cancer-Research UK, GKT School of Medicine, London), respectively, and the Amersham Biosciences enhanced chemiluminescence protocol. For positive control, SK-BR-3 breast tumor cell line that highly expressed HER-2/neu and MUC-1 was used. MEL-11 melanoma cell line, that expressed neither of the proteins, was used as negative control.

DC preparation from peripheral blood

Immature monocyte-derived DCs were prepared from 120 ml of fresh whole blood collected from HLA-A2+ and non-HLA-A2+ healthy volunteers after informed consent (project approved by UCL Hospitals Ethics Committee project 03/0241). PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll/Paque (Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway; 400×g, 30 min, brake off) density gradient centrifugation. At least 1×107 PBMCs were cryopreserved in 90% FCS plus 10% DMSO as APCs for T cells restimulation and ELISPOT, while the rest were resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS to allow adhesion to tissue flask. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C/5%CO2, non-adherent cells were gently removed and frozen for future use as a source of T cells. The adherent cells were subsequently cultured in AIM-V (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) (supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin; complete AIM-V) with 100 ng/ml recombinant human granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and 50 ng/ml Interleukin-4 (IL-4) (gifts from Schering-Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, NJ). After 5 days, B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells were removed by using mouse anti-human CD19, CD3, and CD2, respectively. The DCs were >90% pure after 7 days of culture and expressed moderate levels of HLA-DR, HLA-ABC, and CD40, and low levels of CD86, CD83, CD14, and CD19.

Induction and detection of oxidation-dependent necrotic tumor cell death

Different concentrations of HOCl solutions (5–60 μM) were prepared by diluting the stock NaOCl reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) with HBSS (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and added immediately to the tumor cells to give a final cell density of 8×105 per ml. The tumor cell suspensions were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C/5%CO2 with gentle agitation for every 30 min to induce oxidation-dependent tumor cell death. At the end of the treatment, tumor cells were harvested and washed twice with HBSS for further use. Propidium iodide (PI) was added to the cells directly to detect and quantify the percentage of dead cells [24].

PI staining on permeabilized cells was also used to differentiate between apoptosis and necrosis [24]. An equal volume of 70% ice-cold ethanol was added dropwise to the cells (to a final concentration of 35% ethanol) and left on ice for 10 min to allow permeabilization. The cells were then washed twice with HBSS, followed by treatment with RNase and PI as above, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Apoptosis can be detected by the appearance of a sub-G0 peak, representing partially degraded DNA. This method that measures DNA cell content directly has previously been validated by comparison to annexin V/PI staining. It was chosen in preference because oxidation may damage the annexin V binding epitope on the cell surface and hence lead to false negatives.

Phenotypic analysis of DCs exposed to HOCl-oxidized tumor cells

To investigate the effects of HOCl-oxidized tumor cells on DC maturation, tumor cells were treated as described previously and co-cultured with DCs at 1:1 ratio for 24 h at 37°C/5%CO2. After incubation, DCs were harvested and double stained with PE-conjugated anti-HLA-DR and one of the MoAbs for DC maturation markers (CD83, CD86, or CD40). Briefly, DCs from co-cultures were resuspended in cold staining buffer (HBSS, 10% rabbit serum, 0.1% sodium azide) for 15 min incubation on ice. Relevant MoAbs were added and left on ice for further 30 min, followed by two washes with staining buffer and incubation with the FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (30 min on ice). Then the cells were washed twice with staining buffer and incubated with 1% normal mouse serum in HBSS (10 min on ice). PE-conjugated mouse anti-HLA-DR (clone LN3; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was added and left on ice for another 30 min. After that, the cells were washed three times, fixed in 3.8% formaldehyde, and collected the following day on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) and the data analyzed using the CellQuest software.

DC uptake of oxidized tumor cells

To determine tumor uptake by DCs, tumor cells were labeled with 3′ tetra-methyl-indocarbocyanine per chlorate (DiI, Sigma-Aldrich; final concentration 5 μM) in complete RPMI 1640 medium for 30 min at 37°C/5%CO2 before HOCl-oxidation (DiI staining of tumor cells was less efficient after HOCl treatment). After labeling and oxidation, tumor cells were collected and washed twice with HBSS before adding to the DCs at 1:1 ratio. To detect double positive DCs that had phagocytosed tumor cells, the co-cultures were incubated at 37°C/5%CO2 for 4 or 24 h and stained for HLA-DR. Parallel co-cultures were set up at 4°C for 24 h to determine the level of non-specific DiI transfer to DCs. Flow cytometry analysis was then performed.

Induction of necrotic tumor cell death with hydrochloric acid (HCl) and heat

To induce tumor cell necrosis, 1 M HCl solution was prepared by diluting the 10 M stock HCl (Sigma-Aldrich) in isotonic sodium chloride and added to SK-OV-3 cells to give a final cell density of 8×105 per ml. The cell suspension was incubated for 1 min at room temperature and immediately neutralized with 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Sigma-Aldrich). For heat-induce tumor cell death, SK-OV-3 cells were resuspended in AIM-V medium (final cell density of 8×105 per ml) and heated at 56°C for 30 min. At the end of the treatment, tumor cells were harvested and washed twice with HBSS before adding to the DCs.

In vitro priming of T responder cells

A total of 2×106 autologous DCs were pulsed with 2×106 60 μM HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells overnight to allow uptake. In some experiments, 2×106 60 μM HOCl-oxidized MEL-11 tumor cells were used. About 60 μM HOCl was chosen for tumor oxidation because it consistently induced >99% of necrotic SK-OV-3 tumor cell death (as determined by PI staining) and most efficiently upregulated CD40, CD83, and CD86 maturation markers on DCs. In some experiments, DCs were pulsed with either HCl-killed or heat-killed SK-OV-3, or the DCs were pulsed with HER-2/neu (E75) or MUC1 (M1.2) peptides (final concentration of 1 μM). After 24 h of incubation at 37°C/5%CO2, 2×107 autologous T cells (purified by immunomagnetic bead depletion with antibodies to HLA-DR, CD19, CD14 from non-adherent PBMCs) were added to the DC-antigen co-culture and cultured in complete AIM-V medium. After 7 days, viable T cells were purified of necrotic debris by separation on Ficoll Lymphoprep and restimulated with X-ray irradiated autologous PBMCs (20 Grays) pulsed with relevant oxidized, or killed tumor cells, or peptides in AIM-V medium. Then T cells were re-purified by Ficoll Lymphoprep 4 days after restimulation and cultured in fresh medium without antigen for further 3 days. After that, viable T cells were harvested for IFN-γ ELISPOT.

IFN-γ ELISPOT

IFN-γ ELISPOT was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, MultiScreenTM-ImmobilonTM-P Filtration Plate (Millipore, Bedford, USA) were coated with anti-human IFN-γ capture antibody (1-D1K clone; Mabtech) at 2 μg/ml in HBSS (100 μl/well) overnight at 4°C. Under aseptic conditions, the plates were washed three times with HBSS and blocked with AIM-V medium containing 10% human AB serum for 1 h at 37°C/5%CO2. Then two washes were done and the T responder cells were seeded in the wells at 1×105 cells/well. Cryopreserved autologous PBMCs were rapidly thawed, washed, irradiated, and co-cultured with the T responder cells in the presence of antigens (i.e., HOCl oxidized 1×105 SK-OV-3 or MEL-11 per well or 1 μM peptide per well) at 5×104 cells/well. To check for specificity, T responder cells in certain wells were incubated with PBMCs without antigen or in AIM-V medium only to determine the background secretion of IFN-γ. The ELISPOT plate was incubated for 40 h at 37°C/5%CO2. After incubation, the cells were removed by washing with MilliQ water and PBS. The presence of IFN-γ produced by antigen-specific T cells was detected by the sequential addition of biotinylated mouse anti-human IFN-γ (2 h at room temperature), four washes with PBS (Clare Hall Laboratories, Cancer Research UK, London, UK), alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (1 h at room temperature), four further washes with PBS, and substrates for streptavidin. The number of spots corresponding to the IFN-γ producing cells was counted with an automatic plate reader (Autoimmune Diagnostica GmbH, Strassberg, Germany). The results were expressed as IFN-γ spots per 105 T cells.

HER-2/neu pentamer staining

T cells were stimulated with DCs preloaded with 60 μM HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 tumor cells (one tumor cell to one DC) or HER-2/neu (E75) or MUC1 (M1.2) peptides as described earlier. Viable T cells were harvested after 2 weeks and restimulated for a third week with HER-2/neu or MUC1 peptides and IL-2 (5 ng/ml). At the end of third week, viable T cells were obtained by Ficoll Lymphoprep. A total of 5×105 T cells per group were washed once with staining buffer (PBS with 1% FCS and 0.1% sodium azide) and stained with PE-conjugated HER-2/neu pentamer specific for HER-2/neu E75 for 20 min at 37°C. Cells were then counterstained with CD8-FITC (clone LT8; Proimmune, Oxford, UK) for 30 min on ice. After washing twice with PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide, the cells were fixed with 3.8% formaldehyde and analyzed by flow cytometry by appropriately gating on CD8+ cells and excluding CD4+ cells. T cells that were double positive for CD8 and HER-2/neu pentamer were expressed as a percentage of the total number of CD8+ T cells gated.

Statistics

Means for different experimental groups were analyzed from a minimum of three independent experiments (i.e., PBMCs from different individuals). The analysis of significance was carried out using one-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s post hoc modification when appropriate.

Results

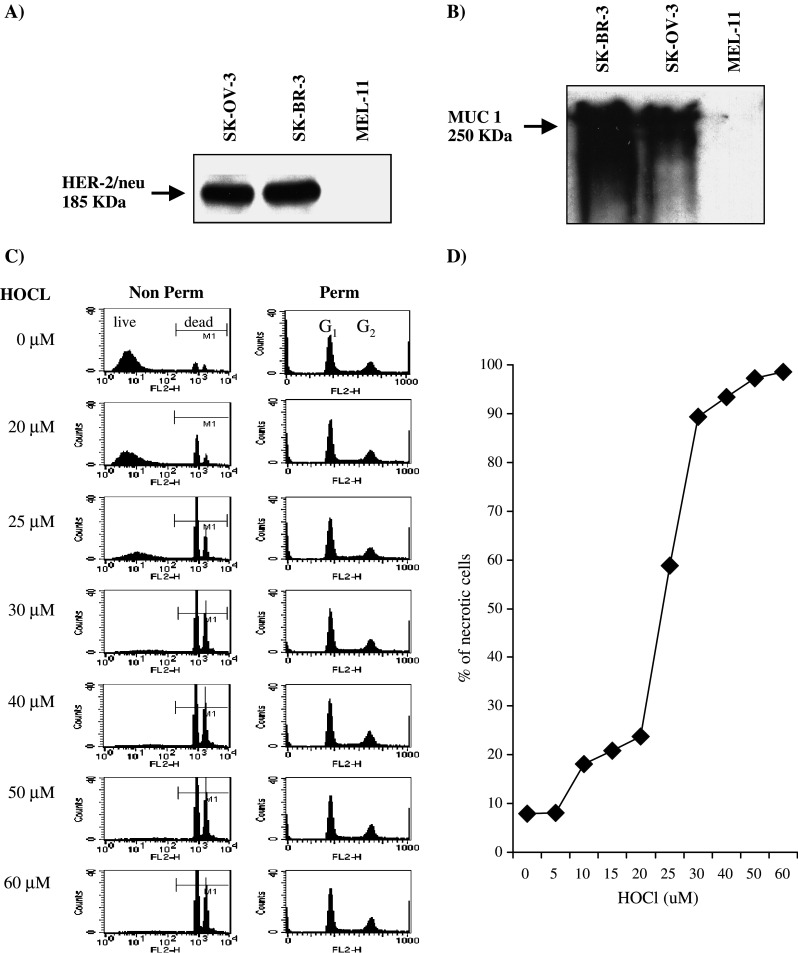

SK-OV-3 ovarian tumor cells express HER-2/neu and MUC-1 antigens

The SK-OV-3 line has been widely studied by both molecular and immunological techniques [21–23] and was therefore chosen as a model source of antigen for these studies. The expression of the two epithelial tumor-associated antigens MUC-1 and HER-2/neu was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1a, b). HER-2/neu (molecular weight approximately 185 KDa) was detected as a single band in both SK-OV-3 and the breast cancer derived line SK-BR-3. MUC-1 glycoproteins were detected as multiple glycosylated variants of approximately 250 KDa in both epithelial lines. Both antigens were absent from the melanoma tumor line MEL-11 and from the myeloid tumor line KG1 (not shown). SK-OV-3 has previously been shown to express HLA-A3; the absence of HLA-A2 was confirmed by flow cytometry (not shown).

Fig. 1.

Expression of HER-2/neu and MUC-1 tumor antigens and dose dependent necrosis of SK-OV-3 cells. a, b 1×106 SK-OV-3, SK-BR-3, and MEL-11 cells were lysed in sample buffer, resolved on 7.5% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The expressions of HER-2/neu and MUC-1 were detected by anti-HER-2/neu and anti-MUC-1 monoclonal antibodies. Note that HER-2/neu appeared as a single band in both SK-OV-3 and SK-BR-3, while MUC-1 glycoproteins were detected as multiple glycosylated variants of approximately 250 KDa in both epithelial lines. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. c, d SK-OV-3 tumor cells were incubated with different concentrations of HOCl as shown for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed and stained with PI as described in Materials and methods either without (non-perm, c left column) or after permeabilization with 70% ethanol (perm, c right column). The percentage of highly PI positive cells (M1 gate) corresponded to percentage of dead cells was plotted against HOCl concentration in d. Data are representative of five independent experiments

HOCl induces cell death of SK-OV-3 cells via necrosis

The sensitivity of SK-OV-3 cells to HOCl oxidation is shown in Fig. 1c and d. Cell survival and cellular DNA content were measured by PI staining of intact and permeabilized cells as described [24]. Treatment of SK-OV-3 cells with increasing concentrations of HOCl resulted in a dose dependent increase in the % unpermeabilized cells which took up PI (gate M1, Fig. 1c left column, quantified in Fig. 1d). Since viable cells are impermeable to PI, the % PI positive cells gives a measure of dead cells. 99% cell death or above was consistently observed at 60 μM HOCl or above, and this concentration was used in all further experiments. Extensive cell fragmentation was observed with 65 μM HOCl or higher (data not shown).

Annexin V/PI staining did not show the presence of apoptotic cells in the HOCl-treated population (not shown). Lack of annexin V staining could have resulted from oxidative damage to the annexin V binding epitope, however. The DNA content of the cells was therefore measured directly [24] (Fig. 1c, right column). PI staining clearly showed the presence of the G1 and G2 peaks, but no sub-G0 staining corresponding to fragmented DNA from cells undergoing apoptosis (cf effects of DNA cross-linking agents on tumor cells, which induce apoptosis and the appearance of a clear sub-G0 peak [24]).

Activation of DC on exposure to oxidized SK-OV-3 cells

Previous studies from our own [24] and other laboratories [7, 27, 30] have suggested that necrotic cells may activate DC. DCs were therefore co-cultured with HOCl-oxidized tumor cells (or LPS as a known DC activator) and the levels of cell surface CD86, CD83, and CD40 measured by flow cytometry (Table 1). Untreated cells had low levels of CD86, no CD83 expression, and intermediate levels of CD40. Increasing HOCl concentration significantly increased mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) for CD86 and CD40 (P<0.05, one-way ANOVA). There was also a small but not statistically significant (P>0.05) increase in the expression of CD83. However, the MFI at all concentrations of HOCl was significantly less than that induced in response to LPS (P<0.01, ANOVA with Dunnett’s modification).

Table 1.

HOCl-treated tumor cells induce partial DC activation

| HOCl (μM) | Percentage of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of untreated DCs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD86 | CD83 | CD40 | |

| 0 | 103.4±15.2 | 133.1±29.5 | 100.6±14.9 |

| 30 | 120.4±20 | 136.1±15.5 | 111.6±11.6 |

| 40 | 165.5±36 | 152.3±13.8 | 121.2±22.6* |

| 50 | 181.9±21.4* | 160.6±14.9 | 131.5±25.3** |

| 60 | 162.3±20.5 | 162.3±21.2 | 129.6±11.6* |

| LPS matured DCs | 394.0±60.2** | 355.4±25.8** | 222.6±32.2** |

SK-OV-3 tumor cells were incubated with HBSS (0 μM) or 30–60 μM HOCl for 1 h at 37°C/5%CO2 and co-cultured with immature DCs at 1:1 ratio for 24 h. Cells were harvested and double-stained for HLA-DR and one of the markers of DC maturation CD86, CD83, or CD40. The MFI for each marker was obtained. Because the absolute MFI values showed individual variation, all values were normalized to mean MFI values of DC cultured in the absence of tumor cells. Table 1 shows the mean ± standard error of the mean for three independent experiments. Asterisk indicate a significant difference from DC alone, calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s modification on the original unnormalized MFI values for each marker

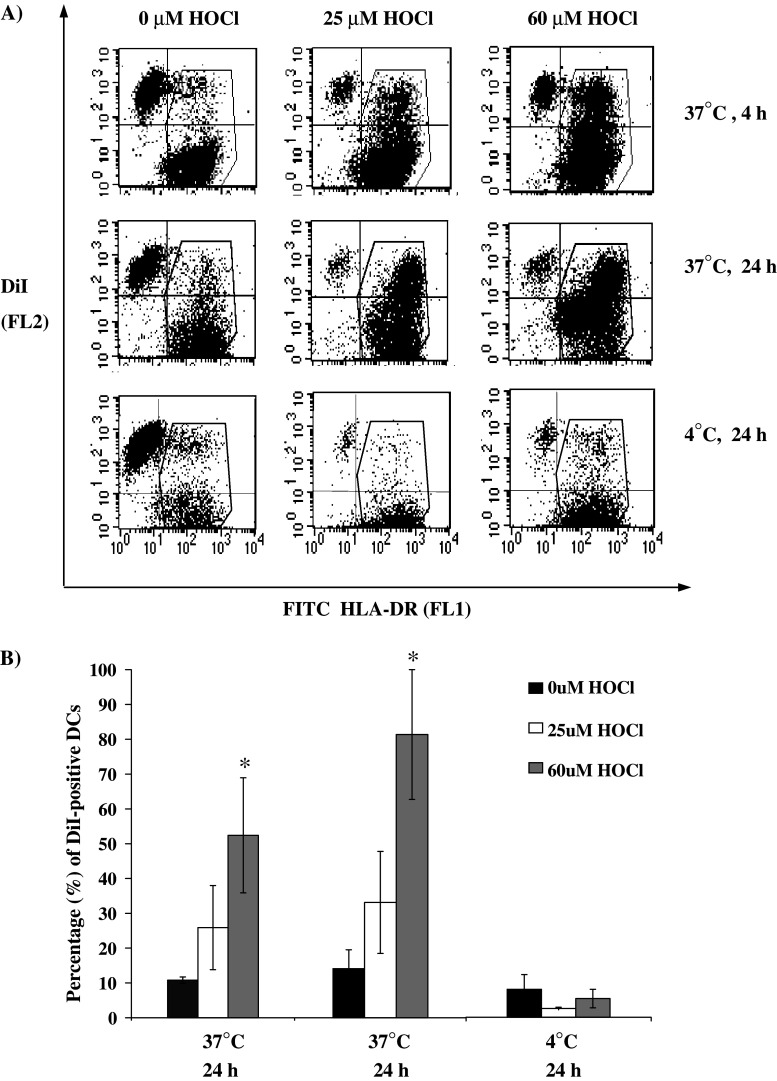

HOCl treatment enhances uptake of SK-OV-3 cells by DC

Uptake of tumor cells is a critical step in the pathway leading to both class I and class II MHC cross-priming. The ability of DC to phagocytose tumor cells was evaluated by flow cytometry, using a method developed previously [24] (Fig. 2). Tumor cells were identified by staining with the membrane dye DiI (FL2, vertical axis) while DCs were identified by the expression of HLA-DR (FL1, horizontal axis). There was little or no uptake of live untreated SK-OV-3 cells even over a 24 h co-culture. In contrast, there was rapid uptake of HOCl-treated cells, with maximum uptake observed at 60 μM HOCl (Fig. 2a, b). Uptake was inhibited at 4°C confirming that SK-OV-3 cells were being taken up by an active process (Fig. 2b). Oxidized tumor cells, while still intact, became rather fragile, and fragmented upon prolonged incubation (note the absence of labeled cells from the upper left quadrant in the 4°C panels).

Fig. 2.

HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells are efficiently phagocytosed by DCs. DiI-labeled SK-OV-3 tumor cells were treated with HBSS, 25 μM HOCl, or 60 μM HOCl for 1 h, washed and co-cultured with DCs at 1:1 ratio for 0, 4, or 24 h at 37 or 4°C. Co-cultures were harvested, stained for HLA-DR, and analyzed by flow cytometry. a Representative flow cytometry profile (one of three experiments). Free residual tumor cells are shown in the top left quadrant, while DCs are found in the right hand quadrants (HLA-DR+). DCs which have taken up SK-OV-3 cells are positive for both HLA-DR and DiI and appeared in the upper right quadrant. b The percentage of DC (DR positive cells) which have taken up DiI under different experimental conditions was plotted against HOCl concentrations, mean ± standard error of the mean for three experiments. The asterisk shows significant difference from 0 HOCl within each group, Student’s paired t test, P<0.05

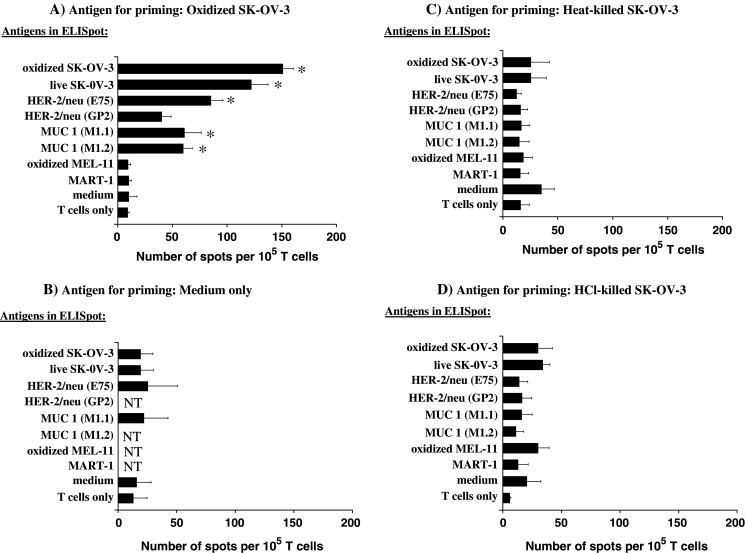

DCs pulsed with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells stimulate T cell responses to tumor cell and to specific tumor antigen epitopes HER-2/neu and MUC-1

DCs prepared from PBMCs of HLA-A2+ healthy volunteers were co-cultured with 60 μM HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells (HLA-A2−, ratio of one DC to one tumor cell) overnight. DCs were then co-cultured with purified autologous T cells (ten T cells to one DC). Viable T cells were harvested after 1 week and restimulated with PBMCs pulsed with oxidized tumor cells for a further 4 days, and then cultured in the absence of antigen stimulation for 3 days as described in Materials and methods. The surviving T cells were tested by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay to assess tumor-specific T cell responses. As shown in Fig. 3a, T cells primed with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells showed a significant (P<0.05) antigen specific recall response to the original immunogen (oxidized SK-OV-3 cells). A response was seen in all seven individuals tested, with a range of 130–220 spots/105 T cells.

Fig. 3.

DCs loaded with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells, but not heat-killed or HCl-killed SK-OV-3, stimulate T cell responses to tumor cells and to specific tumor antigen epitopes HER-2/neu and MUC-1. T cells from HLA-A2+ individuals were stimulated with autologous DCs pulsed with: a 60 μM HOCl-treated SK-OV-3, b complete AIM-V media without antigen, c Heat-killed SK-OV-3 cells, or d HCl-killed SK-OV-3 cells as described in Materials and methods. Viable T cells were harvested after 1 week and restimulated with PBMCs pulsed with the same antigen for another 4 days, and cultured in fresh medium without antigen for three more days. IFN-γ production was measured by ELISPOT. The results are the means ± standard error of the mean for at least three independent experiments (i.e., PBMCs from different individuals). The asterisk indicates those columns differing significantly (P<0.05) from the medium only control (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s modification for multiple comparisons)

T cells primed with oxidized SK-OV-3 gave significant IFNγ responses to live SK-OV-3 cells in the presence of exogenous PBMC (Fig. 3a, second bar). This result indicates that the T cells stimulated by the oxidized SK-OV-3 cells also recognize non-modified antigens, an essential requirement if the cells are to have useful anti-tumor activity in vivo. In contrast, the T cells stimulated by the oxidized SK-OV-3 cells failed to respond to oxidized melanoma cells, indicating that the response showed cell type specificity.

The T cells stimulated with the oxidized SK-OV-3 cells also responded to peptides encoding known HLA-A2 epitopes of HER-2/neu and MUC 1. Since SK-OV-3 cells are HLA-A2−, this response demonstrates that the oxidized SK-OV-3 cells had been taken up and cross-presented by the stimulating DC. The response to E75 HER-2/neu peptide was consistently better than the response to GP2 HER-2/neu peptide (three of three individuals, although the difference in the means did not reach significance; P=0.06), suggesting that a predetermined epitope hierarchy exists within the HER-2/neu antigen. The T cells did not respond significantly to an HLA-A2 melanoma peptide, confirming antigen specificity of the observed response.

T cells primed with DC in the absence of tumor cells failed to show significant recall responses to any of the antigens tested (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, T cells primed with live SK-OV-3 cells (X-ray irradiated in order to prevent proliferation) gave only very weak responses (less than 60 spots/105 cells; data not shown). It was important, however, to determine whether the enhanced immune response seen was due specifically to oxidation by HOCl, or was simply a result of cell necrosis. SK-OV-3 necrosis was therefore induced by two other means, heat treatment (56°C, 30 min) or brief exposure to acid (1 M HCl, 60 s). Under these conditions, SK-OV-3 cells retained cellular integrity but were >99% dead by necrosis (confirmed by trypan blue and PI staining, data not shown). T cells primed using DC loaded with either heat-killed (Fig. 3c) or acid killed (Fig. 3d) SK-OV-3 failed to prime a significant immune response to any antigen tested.

Direct versus indirect presentation of oxidized SK-OV-3 cells

The presence of HLA-A2 restricted HER-2/neu specific cells, suggesting cross-presentation of HLA-A2− SK-OV-3 cells by HLA-A2+ DC, was confirmed by HLA-A2 pentamer staining. T cells were stimulated with autologous DCs pulsed with either 60 μM HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3, HLA-A2 restricted HER-2/neu E75 peptide, or MUC1 M1.2 peptide, and expanded as described in Materials and methods. Viable T cells were harvested and double stained with anti-CD8 antibody and HER-2/neu pentamer specific for HER2/neu E75 peptide bound to HLA-A2. T cells primed with oxidized SK-OV-3 cells, as well as HER-2/neu E75 peptide contained a population of pentamer binding CD8 positive T cells (Fig. 4a, top two panels) while cells primed with MUC1 peptide showed background staining (Fig. 4a, bottom panel). Three individuals were tested in this way, with average CD8/pentamer positive percentages of 1.42% (primed with oxidized SK-OV-3 cells), 0.77% (primed with HER-2/neu E75) and 0.02% (primed with MUC1 M1.2).

Fig. 4.

Cross-priming is necessary for presentation of HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells. a T cells were co-cultured with autologous DCs (ten T cells to one DC) preloaded with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells, HER-2/neu E75 peptide or MUC1 M1.2 peptide as shown. After two further rounds of antigen stimulation (see details in Materials and methods) viable T cells were harvested and double-stained with anti-CD8 FITC and PE-conjugated HER-2/neu pentamer specific for HER-2/neu E75/HLA-A2. The percentage of total CD8+ T cells positive for pentamer is shown on the top right hand corner. Data are one representative out of three independent experiments. b T cells were primed with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells as in Fig. 3 and their IFNγ responses to HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 or HER-2/neu peptide, in the presence or absence of autologous PBMC was evaluated with ELISPOT. The results are the means ± standard error of the mean for at least three independent experiments (i.e., PBMCs from different individuals). The asterisk indicates those columns differing significantly (P<0.05) from the T cell only control (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s modification for multiple comparisons). c T cells were primed with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells as in Fig. 3 and their IFNγ responses to live MDA-231 (HLA-A2+, MUC-1+, HER-2/neu +) or live MEL-12 (HLA-A2+, MUC-1−, HER-2/neu −) in the absence of autologous PBMC was evaluated with ELISPOT. The results are one representative experiment of two

In order to determine whether oxidized SK-OV-3 cells stimulated IFN-γ release by primed T cells directly (i.e., allogeneic direct interaction), or whether T cell stimulation depended exclusively on reprocessing by autologous antigen presenting cells, T cells were cultured with HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 cells in the presence or absence of HLA-A2+ PBMCs as source of antigen presenting cells (Fig. 4b). The response to HOCl-treated cells was not significantly above background in the absence of PBMCs. HOCl treatment therefore seems not only to enhance cross-presentation, but to inhibit direct allogeneic recognition.

In contrast, T cells from an HLA-A2+ individual primed to the oxidized SK-OV-3 cells, responded directly (i.e., in the absence of exogenous PBMC) to live cells of an HLA-A2 expressing MUC-1 and HER-2/neu expressing breast cancer cell line MDA-231 (an HLA-A2+ ovarian line was not available to us) but not to an HLA-A2+ melanoma cell line MEL-12 (Fig. 4c).

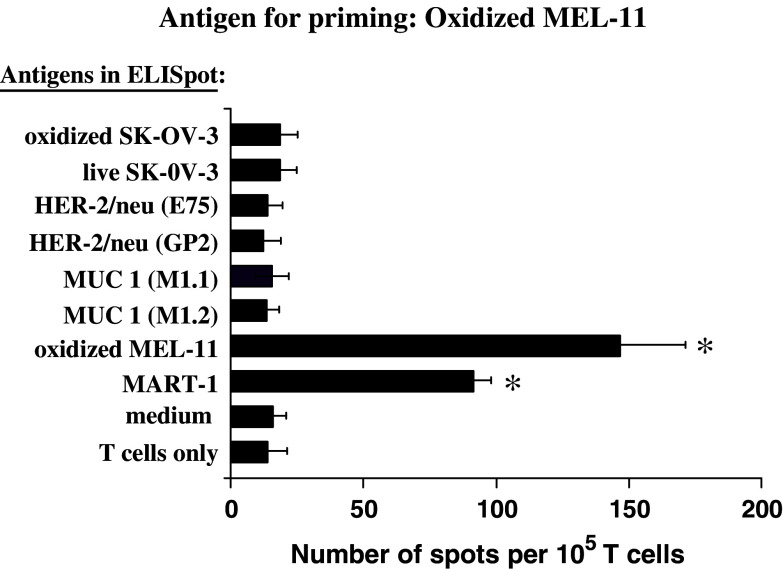

Antigen specific responses to oxidized tumor cells is not restricted to SK-OV-3 cells

The role of HOCl in enhancing tumor-specific T cell responses was tested further using an HLA-A2− melanoma cell line, MEL-11, which expresses the melanoma associated antigen MART-1 (not shown) but neither HER2/neu nor MUC 1 (Fig. 1). T cells primed with DC loaded with HOCl-oxidized MEL-11 cells showed strong responses to MEL-11 cells themselves, as well as to an HLA-A2 restricted peptide derived from MART-1 (Fig. 5). Thus, HOCl-oxidized melanoma cells, like ovarian tumor cells, effectively stimulate antigen specific T cells via cross-priming. MEL-11 stimulated cells, however, failed to respond to oxidized SK-OV-3 cells, or any of the HER-2/neu or MUC 1 peptides (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

HOCl-oxidized MEL-11 cells induce melanoma specific T cells which do not cross-react with SK-OV-3 cells. T cells were primed to oxidized MEL-11 cells as described in Fig. 3. Their IFN-γ production in response to HOCl-oxidized SK-OV-3 or MEL-11 cells, HER-2/neu peptide, MUC-1 peptides, or MART-1 peptides in the presence of autologous PBMC was measured by ELISPOT. The results are the means ± standard error of the mean for at least three independent experiments (i.e., PBMCs from different individuals). The asterisk indicates those columns differing significantly (P<0.05) from the medium only control (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s modification for multiple comparisons)

Discussion

Dendritic cells are key regulators of the immune system and are capable of initiating and inducing tumor-specific cytotoxic and helper T cells. Indeed, DC-based immunotherapy has been vigorously pursued in clinical trials with some success [6, 12, 19, 22, 26, 28, 30]. In the case of ovarian carcinoma, DC have been pulsed with HLA-A2 restricted peptides coding for immunodominant epitopes of either HER-2/neu or MUC-1 proteins [26]. Though the synthesis of large quantities of clinical grade peptides is technically straightforward, there are several limitations of peptide immunogens, including the need for patients with specific HLA haplotype, limited anti-tumor responses, selection of escape variants, and lack of long-lasting memory. An alternative is to use whole ovarian tumor cells that highly express HER-2/neu and MUC-1, together with many as yet undefined TAAs [12]. In this study, we developed a robust ex vivo human cell culture system of loading HLA-A2+ DCs from healthy volunteers with whole allogeneic SK-OV-3 tumor cells, and assessing their potential for generating autologous tumor-specific T cells.

The first key element of this model was that the immunogenicity of the tumor cells was enhanced by treatment with HOCl, a strong oxidizing agent, which induced rapid necrosis of SK-OV-3 tumor cells. Enhancement of anti-tumor immunity thus extends previous observations of enhanced immune responses to protein antigens treated with HOCl [1, 17, 18]. Several studies have suggested that cell necrosis, per se, may enhance immunogenicity, perhaps by exposing heat shock proteins [3, 15, 27]. Importantly, therefore, enhanced imunogenicity to oxidized cells was seen when compared to response to SK-OV-3 cells killed by other means, such as heat or acid treatment. Since HOCl, and the closely related chemical HCl, differ principally in that the former is a strong oxidizing agent, while the latter is not, these results suggest that oxidization is an essential feature of the enhancement in immunogenicity observed. Preliminary studies have shown that other forms of oxidation (e.g., by H2O2) can also improve immunogenicity, and the precise nature of the chemical reactions responsible are being investigated further.

The mechanism for enhanced immunogenicity may be explained, at least in part, by the fact that the oxidized cells were taken up much more efficiently than live cells by DC, and experiments are underway to try and identify the receptor involved in DC uptake. However, HCl-killed or heat-killed tumor cells also showed some enhanced uptake in comparison with live cells (not shown), suggesting that other mechanisms, such as more efficient processing, may also play a role. In addition, oxidized SK-OV-3 tumor cells induced a partial activation of DCs by upregulating the maturation associated markers CD86 and CD40. DC maturation induced by oxidized SK-OV-3 cells was sub-optimal compared to the Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist LPS, however, and additional stimulation of DC (e.g., via CD40 ligation) may further enhance the response.

A second key aspect of this model was the role of cross-presentation versus direct T cell/tumor cell interaction. The detection of responses to well-defined HLA-A2 restricted epitopes of HER-2/neu and MUC-1 clearly demonstrated that oxidized SK-OV-3 cells (which were HLA-A2− and allogeneic to the DC and T cells) were efficiently cross-presented by the DC. The strong peptide-specific responses demonstrated that a major part of the T cell response was to “native” cellular antigens, rather than to new neoepitopes formed by chemical modification with HOCl. The ability of T cells primed to oxidized tumor cells to recognize live tumor targets was confirmed by using an HLA-A2+ expressing breast tumor line, MDA-231, which shared both MUC-1 and Her-2/neu antigen expression with SK-OV-3 (Fig. 4c). Shared antigen expression was essential for recognition, since an HLA-A2 matched melanoma tumor was not recognized.

HOCl oxidation not only promoted cross-presentation, but also seemed to block direct allorecognition, since the T cell IFN-γ response to oxidized cells (Fig. 4b) showed an absolute requirement for antigen presenting cells. Unexpectedly, the T cells primed to oxidized SK-OV-3 also recognized live SK-OV-3 (Fig. 3a), even though these cells were taken up very poorly, and did not express HLA-A2. Direct recognition of SK-OV-3 cells could have occurred, however, either through a shared unknown HLA allele between volunteer and SK-OV-3 (since the volunteers were typed only for the presence of HLA-A2), or via the presence of promiscuous tumor derived peptides able to interact with many different HLA alleles. The dominance of cross-presentation in this model may have important practical consequences, since it may allow the use of generic tumor-derived cell lines as immunogens, in place of patient-derived tumor cells which are more difficult to obtain and inherently more heterogeneous. The HLA of the cell line used as immunogen will in fact be irrelevant, since T cells will be primed to antigens presented in the context of the host MHC on host DCs. Such T cells will therefore be syngeneic to the primary host tumor, and therefore should be able to recognize the primary tumor directly. In this scenario a cell line would simply need to share tumor antigens with the primary tumor (e.g., MUC-1 or HER-2/neu positive tumors for SK-OV-3 priming). The use of such “standardized” cell lines would have major benefits in terms of practical application, since it obviates the need for patient specific tumor tissue collection and preparation. Studies to test this hypothesis, using primary autologous patient-derived tumor cells as targets following in vitro immunization with SK-OV-3 cells are in progress.

The third important observation in this study was the tumor specificity of the response. A persistent concern in the development of tumor immunotherapy is that the immune system will recognize and kill cells other than the tumor and hence cause autoimmune disease. This problem is particularly acute with the use of whole cell immunogens, since all cells share an enormous number of “common” proteins involved in housekeeping cellular metabolic functions, as well as expressing smaller numbers of “tissue specific” proteins. It is, therefore, of importance that in this model the response showed specificity in relation to at least two quite distinct tumor cell types. SK-OV-3 specific T cells did not respond to the melanoma line MEL-11, or indeed a myeloid tumor derived tumor line KG1 (not shown), while conversely, T cells immunized to MEL-11 melanoma cells did not respond to SK-OV-3 cells. Further studies are in progress to identify the breadth of the response to SK-OV-3 cells, in terms of tissue specificity, tumor specificity, and its ability to recognize “normal” tissue.

The ability of innate immunity to drive enhanced adaptive immunity is now a central tenet of immunology. In this study, we seek to manipulate tumor immunity using HOCl, a known microbicidal product of myeloperoxidase activity in neutrophils. Although myeloperoxidase is well-established as playing a role in the effector microbicidal function of neutrophils, its role in linking innate and adaptive immunity has only been recognized more recently [16]. As discussed above, in vivo vaccination of patients with DCs preloaded with oxidized SK-OV-3 may induce therapeutic tumor-specific T cells responses to autologous tumor cells. Cytolysis of tumor cells by tumor-specific T cells will release further tumor antigen, and also release cytokines that drive localized inflammation. A virtuous cycle of further rounds of oxidation and immunological stimulation is thus established.

Acknowledgment

C.L.-L. Chiang is supported by a Cancer Research UK studentship.

References

- 1.Allison ME, Fearon DT. Enhanced immunogenicity of aldehyde-bearing antigens: a possible link between innate and adaptive immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2881–2887. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2881::AID-IMMU2881>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barratt-Boyes SM, Vlad A, Finn OJ. Immunization of chimpanzees with tumor antigen MUC1 mucin tandem repeat peptide elicits both helper and cytotoxic T-cell responses. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1918–1924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu S, Binder RJ, Suto R, Anderson KM, Srivastava PK. Necrotic but not apoptotic cell death releases heat shock proteins, which deliver a partial maturation signal to dendritic cells and activate the NF-kappa B pathway. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1539–1546. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brossart P, Heinrich KS, Stuhler G, Behnke L, Reichardt VL, Stevanovic S, Muhm A, Rammensee HG, Kanz L, Brugger W. Identification of HLA-A2-restricted T-cell epitopes derived from the MUC1 tumor antigen for broadly applicable vaccine therapies. Blood. 1999;93:4309–4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brossart P, Wirths S, Stuhler G, Reichardt VL, Kanz L, Brugger W. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vivo after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96:3102–3108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerundolo V, Hermans IF, Salio M. Dendritic cells: a journey from laboratory to clinic. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:7–10. doi: 10.1038/ni0104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Moyana T, Saxena A, Warrington R, Jia Z, Xiang J. Efficient antitumor immunity derived from maturation of dendritic cells that had phagocytosed apoptotic/necrotic tumor cells. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:539–548. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Disis ML, Schiffman K. Cancer vaccines targeting the HER2/neu oncogenic protein. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:12–20. doi: 10.1016/S0093-7754(01)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disis ML, Gooley TA, Rinn K, Davis D, Piepkorn M, Cheever MA, Knutson KL, Schiffman K. Generation of T-cell immunity to the HER-2/neu protein after active immunization with HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccines. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2624–2632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisk B, Blevins TL, Wharton JT, Ioannides CG. Identification of an immunodominant peptide of HER-2/neu protooncogene recognized by ovarian tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte lines. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2109–2117. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gritzapis AD, Sotiriadou NN, Papamichail M, Baxevanis CN. Generation of human tumor-specific CTLs in HLA-A2.1-transgenic mice using unfractionated peptides from eluates of human primary breast and ovarian tumors. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:1027–1040. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0541-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernando JJ, Park TW, Kubler K, Offergeld R, Schlebusch H, Bauknecht T. Vaccination with autologous tumour antigen-pulsed dendritic cells in advanced gynaecological malignancies: clinical and immunological evaluation of a phase I trial. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s00262-001-0255-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holmberg LA, Sandmaier B. Vaccination as a treatment for breast or ovarian cancer. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3:269–277. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwu P, Freedman RS. The immunotherapy of patients with ovarian cancer. J Immunother. 2002;25:189–201. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200205000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotera Y, Shimizu K, Mule JJ. Comparative analysis of necrotic and apoptotic tumor cells as a source of antigen(s) in dendritic cell-based immunization. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8105–8109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcinkiewicz J. Neutrophil chloramines: missing links between innate and acquired immunity. Immunol Today. 1997;18:577–580. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(97)01161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcinkiewicz J, Chain BM, Olszowska E, Olszowski S, Zgliczynski JM. Enhancement of immunogenic properties of ovalbumin as a result of its chlorination. Int J Biochem. 1991;23:1393–1395. doi: 10.1016/0020-711X(91)90280-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcinkiewicz J, Olszowska E, Olszowski S, Zgliczynski JM. Enhancement of trinitrophenyl-specific humoral response to TNP proteins as the result of carrier chlorination. Immunology. 1992;76:385–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morisaki T, Matsumoto K, Onishi H, Kuroki H, Baba E, Tasaki A, Kubo M, Nakamura M, Inaba S, Yamaguchi K, Tanaka M, Katano M. Dendritic cell-based combined immunotherapy with autologous tumor-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine and activated T cells for cancer patients: rationale, current progress, and perspectives. Hum Cell. 2003;16:175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-0774.2003.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray JL, Gillogly ME, Przepiorka D, Brewer H, Ibrahim NK, Booser DJ, Hortobagyi GN, Kudelka AP, Grabstein KH, Cheever MA, Ioannides CG. Toxicity, immunogenicity, and induction of E75-specific tumor-lytic CTLs by HER-2 peptide E75 (369–377) combined with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in HLA-A2+ patients with metastatic breast and ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3407–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer K, Moore J, Everard M, Harris JD, Rodgers S, Rees RC, Murray AK, Mascari R, Kirkwood J, Riches PG, Fisher C, Thomas JM, Harries M, Johnston SR, Collins MK, Gore ME. Gene therapy with autologous, interleukin 2-secreting tumor cells in patients with malignant melanoma. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:1261–1268. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palucka AK, Dhodapkar MV, Paczesny S, Burkeholder S, Wittkowski KM, Steinman RM, Fay J, Banchereau J. Single injection of CD34+ progenitor-derived dendritic cell vaccine can lead to induction of T-cell immunity in patients with stage IV melanoma. J Immunother. 2003;26:432–439. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peoples GE, Goedegebuure PS, Smith R, Linehan DC, Yoshino I, Eberlein TJ. Breast and ovarian cancer-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize the same HER2/neu-derived peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:432–436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rad AN, Pollara G, Sohaib SM, Chiang C, Chain BM, Katz DR. The differential influence of allogeneic tumor cell death via DNA damage on dendritic cell maturation and antigen presentation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5143–5150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renard V, Sonderbye L, Ebbehoj K, Rasmussen PB, Gregorius K, Gottschalk T, Mouritsen S, Gautam A, Leach DR. HER-2 DNA and protein vaccines containing potent Th cell epitopes induce distinct protective and therapeutic antitumor responses in HER-2 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:1588–1595. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santin AD, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Bossini B, Cane S, Bignotti E, Roman JJ, Cannon MJ, Pecorelli S. Restoration of tumor specific human leukocyte antigens class I-restricted cytotoxicity by dendritic cell stimulation of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:64–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sauter B, Albert ML, Francisco L, Larsson M, Somersan S, Bhardwaj N. Consequences of cell death: exposure to necrotic tumor cells, but not primary tissue cells or apoptotic cells, induces the maturation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells [see comments] J Exp Med. 2000;191:423–434. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuler G, Schuler-Thurner B, Steinman RM. The use of dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:138–147. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(03)00015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaif-Muthana M, McIntyre C, Sisley K, Rennie I, Murray A. Dead or alive: immunogenicity of human melanoma cells when presented by dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6441–6447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov GV, Barnd DL, Eastham S, Galavotti H, Patterson JW, Deacon DH, Hibbitts S, Teates D, Neese PY, Grosh WW, Chianese-Bullock KA, Woodson EM, Wiernasz CJ, Merrill P, Gibson J, Ross M, Engelhard VH. Clinical and immunologic results of a randomized phase II trial of vaccination using four melanoma peptides either administered in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in adjuvant or pulsed on dendritic cells. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4016–4026. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolpoe ME, Lutz ER, Ercolini AM, Murata S, Ivie SE, Garrett ES, Emens LA, Jaffee EM, Reilly RT. HER-2/neu-specific monoclonal antibodies collaborate with HER-2/neu-targeted granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor secreting whole cell vaccination to augment CD8+ T cell effector function and tumor-free survival in Her-2/neu-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:2161–2169. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Conejo-Garcia JR, Katsaros D, Gimotty PA, Massobrio M, Regnani G, Makrigiannakis A, Gray H, Schlienger K, Liebman MN, Rubin SC, Coukos G. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]