Abstract

The identification and validation of new cancer-specific T cell epitopes continues to be a major area of research interest. Nevertheless, challenges remain to develop strategies that can easily discover and validate epitopes expressed in primary cancer cells. Regarded as targets for T cells, peptides presented in the context of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) are recognized by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). These mAbs are of special importance as they lend themselves to the detection of epitopes expressed in primary tumor cells. Here, we use an approach that has been successfully utilized in two different infectious disease applications (WNV and influenza). A direct peptide-epitope discovery strategy involving mass spectrometric analysis led to the identification of peptide YLLPAIVHI in the context of MHC A*02 allele (YLL/A2) from human breast carcinoma cell lines. We then generated and characterized an anti-YLL/A2 mAb designated as RL6A TCRm. Subsequently, the TCRm mAb was used to directly validate YLL/A2 epitope expression in human breast cancer tissue, but not in normal control breast tissue. Moreover, mice implanted with human breast cancer cells grew tumors, yet when treated with RL6A TCRm showed a marked reduction in tumor size. These data demonstrate for the first time a coordinated direct discovery and validation strategy that identified a peptide/MHC complex on primary tumor cells for antibody targeting and provide a novel approach to cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: T cell epitope discovery, Human leukocyte antigens, Major histocompatibility complex, Peptide, T cell receptor mimics, Monoclonal antibody, P68 RNA helicase/dead box protein, Mass spectrometry, Orthotopic model, Therapeutic effect

Introduction

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are able to recognize antigenic determinants of diverse chemical composition with high affinity and specificity making them good candidates for therapeutic development and active targeting. As such, mAb made against tumor markers have been successfully exploited as cancer therapeutics [1–7]. Yet, for all of these successes only a limited number of relevant targets have been identified that are accessible for antibody targeting and induction of antitumor responses. Efforts continue to be made to develop new technologies for the identification of novel targets for antibody generation.

A potential class of surface markers not yet explored for antibody targeting is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) or human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system. MHC (HLA) class I molecules are an attractive target as they are constitutively expressed on the surface of all nucleated cells in the body. The MHC class I molecules load peptide fragments derived from degraded cellular proteins, many of which are localized in intracellular compartments, for transport and eventual presentation on the cell surface [8, 9]. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) survey the peptides presented by class I MHC and are thought to target the cells displaying disease-specific peptides [10, 11]. Thus, MHC class I molecules loaded with specific peptides can be used to distinguish diseased from healthy cells [12].

Several different strategies are currently in use to discover new peptide/MHC class I epitopes. These include (1) an indirect classical strategy that relies on the expression profiling of uniquely expressed tumor-associated antigens (TAA) by tumor cells and (2) a direct strategy involving biochemical processes that relies on directly eluting peptides from MHC molecules expressed on the surface of tumor cells and then performing mass spectrometric analysis [13]. In expression profiling the TAA is examined for peptides that might be processed and bind to a particular HLA allele [14–17]. The limitation of this strategy is the imperfection of the predictive algorithms used to identify the peptides. The direct discovery strategy provides specific information regarding the number of epitopes that uniquely decorate a cancer cell [18]. However, this approach is limited by the minute amounts of peptide available for analysis and is further complicated by the impurities of the peptide sample that includes peptides simultaneously eluted from up to six different HLA class I molecules. We have recently reported on a more robust system that allows for the direct identification of peptides [19–21]. However, this system uses tumor cell lines for peptide identification and it remains to be determined whether the peptides expressed by cell lines are truly representative of those found in primary tumor cells. Further, it is not possible for T cells and mass spectrometric analysis to directly validate the expression of discovered epitopes in primary tumor tissue. However, antibodies specific for peptide/MHC molecules could be used to directly validate epitope expression in primary tumor cells and might also have therapeutic applications.

The utilization of antibodies to recognize MHC-restricted peptide targets on the surface of cancer cells have several significant benefits. First, anti-peptide/MHC mAbs could be used to directly validate epitope expression in fresh tissue. Second, these mAbs might lead to the detection of novel biomarkers for cancer diagnosis. Finally, it might be possible to markedly expand the repertoire of therapeutic mAbs if it were shown that these molecules had antitumor properties. In recent years, antibodies have been described for the direct detection and visualization of specific peptide–MHC complexes (T cell epitopes) on the surface of cells [22, 23]. Several groups including our laboratory have consistently been able to generate anti-peptide/MHC mAbs that we designate as TCRm [24, 25]. TCRm reagents would presumably be well suited for directly defining tumor peptide-epitopes expressed in primary tumor cells. This could lead to new targets for cancer diagnosis and therapeutic intervention.

Here, we demonstrate the successful integration of two technologies that were used to directly identify the YLLPAIHVI peptide from RNA helicase p68 protein present in the context of HLA-A2 from human breast carcinoma cell lines and then use the RL6A TCRm to directly validate expression in primary human breast tissue. Finally, we show the potential therapeutic application of the RL6A mAb to inhibit tumor growth in an orthotopic breast cancer model.

Materials and methods

Identification of YLLPAIHVI p68 peptide

We have previously reported on the strategy for peptide-epitope discovery [19–21, 25, 26]. In brief, in the present experiments human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 and BT-20 were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were transfected with plasmid constructs expressing soluble HLA-A*0201 (sHLA) in the expression vector pcDNA3.1. Stable transfectants were established by selection in G418 Sulfate (CELLGRO-Mediatech, Lawrence, KS). Resistant colonies were subcloned by single cell sorting (Influx Sorter, Cytopeia, Seattle, WA), grown to near confluency and sHLA production screened by ELISA with the highest sHLA-secreting subclones used for epitope-identification experiments.

Successfully transfected cancer cell lines that produce >40 ng/ml of sHLA-A*0201 protein in flasks were grown in bioreactors (Toray, Tokyo, Japan) in a CP2500 Cell Pharm (Biovest International, Minneapolis, MN). Cell growth was maintained for 8–12 weeks in DMEM/F12K (Caisson Laboratories, North Logan, UT) under optimal pH, oxygen and glucose. sHLA-A*0201 molecules were purified from harvested pools by affinity chromatography using anti-HLA W6/32 monoclonal antibody (HB95, ATCC) that was linked to CnBr-activated Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). sHLA–peptide complexes were eluted with 0.2 N acetic acid, after which fractions containing sHLA were brought up to 10% acetic acid and heated at 76°C for 10 min to dissociate endogenous peptides from sHLA heavy chains and β2-microglobulin. Eluted peptides were then separated from MHC heavy and light chains by ultrafiltration in a stirred cell with a 3 kDa molecular weight cutoff cellulose membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and flash frozen prior to lyophilization. A harvest of 20–30 mg of sHLA complex provided 250–500 μg of free isolated peptides representing the endogenously bound class I peptides. The eluted peptides were desalted and fractionated by reverse-phase HPLC using a standard gradient of acetonitrile.

Mass spectrometric analysis

Each peptide fraction obtained from the HPLC was mapped by mass spectrometry. Initial ion scans were performed on a QStar Elite mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) equipped with a NanoSpray nano-ESI ionization source, with windows of 300–1,200 atomic mass units (amu), and later, locked into 15 amu increments and visually compared between three different cancer cell lines. Identified ions corresponding to the presence of specific peptides were then subjected to tandem mass spectroscopy (MS/MS) to obtain peptide sequences. Comparison of peptides in the mass spectrometric maps indicated peptide epitopes, including their number and relative abundance, consistently found in cancer cell lines.

An ion with an m/z of 519.82 was identified as shared in the MS ion maps and was selected for MS/MS analysis. A sequence of YLLPAIVHI was assigned to this ion. The MS/MS spectra obtained were compared with the spectra of synthetic p68 peptide (YLLPAIVHIaa128–136). The synthetic peptide contained the identical amino acid sequence corresponding to the putative p68 peptide found, when subjected to MS/MS under identical conditions as the naturally occurring peptide and overlaid to confirm sequence identity, confirming the endogenous p68 peptide sequence. Fragmentation patterns generated from MS/MS were interpreted with the aid of web-based applications BioExplorer, MASCOT, Protein Prospector and BLAST, to identify the p68 protein origin [20].

Cell lines and human PBLs

The human tumor cell lines SW620 (colorectal), SKOV-3-A2 (ovarian), the human monocytic cell line THP-1 and T2 cells, a human B lymphoblast cell line deficient in TAP 1 and 2 proteins [27] were obtained from the ATCC. The breast cancer cell line 1520 was a kind gift from Dr. Soldano Ferrone, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. Human PBMCs from anonymous donors were obtained from separation cones of discarded apheresis units from the Coffee Memorial Blood Center (Amarillo, TX) after platelet harvest. Monocytes were isolated and used to generate immature dendritic cells (iDC).

Antibodies and synthetic peptide

Polyclonal antibody goat anti-mouse IgG heavy chain–phycoerythrin (PE) was purchased from Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Isotype control antibodies, mouse IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b, were purchased from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL). The BB7.2 (anti-HLA-A2.1 mAb) expressing mouse hybridoma cell line was purchased from the ATCC. Peptide p68 RNA helicase YLLPAIVHI (residues 128–136, designated as YLL 128); peptides TLAYLIFLL and KLMSPKLYV from CD19; peptide LLGRNSFEV from p53 tumor suppressor protein; peptide VLMTEDIKL from eIF4G protein; peptide ILDQKINEV from ornithine decarboxylase protein; and peptide KIFGSLAFL from Her2/neu protein were synthesized at the University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, Oklahoma City, OK, using a solid-phase method and purified by HPLC to greater than 90%.

Generation of HLA-A2 monomer and tetramers

HLA-A2 extracellular domain containing a C-terminus BirA sequence and β2m were produced as inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli and refolded essentially as described previously [28]. After refolding, the peptide–HLA-A2 mixture was concentrated and properly folded monomer complexes were isolated from contaminants on a Superdex 75 sizing column (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Piscataway, NJ). Monomer concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and then biotinylated using biotin ligase (Avidity, Boulder, CO). After a second purification on the Superdex 75 sizing column, biotin-labeled monomer was then used to generate tetramer complexes by addition of streptavidin that were used in tetramer blocking assays or used in plasmon surface resonance studies.

Generation of RL6A TCRm

TCRm antibodies were generated as described previously [24, 25]. Briefly, female BALB/c mice were immunized with a solution containing 50 μg of purified YLL peptide/HLA-A2 complex and Quil-A adjuvant (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 14-day intervals. Hybridoma supernatants were screened by ELISA followed by confirmation analysis using peptide-pulsed T2 cells.

ELISA

ELISA assays were performed using Maxisorb 96-well plates (Nunc, Rochester, NY). Assays to evaluate binding specificity of the TCRm antibodies were done on plates coated with 100 ng/well HLA/peptide tetramer. Bound antibodies were detected with peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) followed by the addition of ABTS (Pierce). Reactions were quenched with 1% SDS. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm on a Victor II plate reader (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA). The SBA Clonotyping System/HRP and mouse immunoglobulin panel from Southern Biotech were used to estimate the concentration of RL6A (isotype IgG2a) in the supernatant of FBS-containing medium. The assay was run according to manufacturer’s directions and RL6A signal was compared with that of an IgG2a standard supplied by the manufacturer. Development, quenching and analysis of the plates were performed as described above for the TCRms.

Cell staining

T2 is a mutant cell line that lacks transporter-associated protein (TAP) 1 and 2 which allows for efficient loading of exogenous peptides. The T2 cells were pulsed with the peptides at 20 μg/ml for 4 h in AIM-V with the exception of the peptide-titration experiments in which the peptide concentration was varied as indicated. Cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS + 0.5% FBS + 2 mM EDTA) and then stained with 25 and 50 ng/ml of RL6A TCRm, BB7.2 or isotype control antibody for 15–30 min in 100 μl FACS buffer. Cells were then washed with 2 ml FACS buffer and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of FACS buffer containing 2 μl of either of two goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (FITC or PE labeled). After incubating for 15–30 min at room temperature, the wash was repeated and cells were resuspended in 0.25 ml FACS buffer, analyzed on a FACS Canto II instrument and evaluated using FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). Tumor cell lines were stained and evaluated in the same manner as the T2 cells, after being released from plates and washed in FACS buffer.

Plasmon surface resonance

Experiments were performed using SensiQ (ICx Nomadics, Oklahoma City, OK) biomolecular interaction analysis optimized for doing surface plasmon resonance. Briefly, Protein A was coupled to SensiQ sensors using EDC/NHS chemistry and then soluble RL6A TCRm was captured by passing a solution of the TCRm (3.125 nM) over sensor at a rate of 1 ml/min to achieve 1.578 response units (RUs). The sensor was washed with HBS-TE buffer and then six concentrations (10–311 nM) of soluble YLL peptide/HLA-A2 monomer was sequentially run over the sensor and the amount of captured monomer was used to calculate the binding affinity constant and half-life of dissociation using Q-DAT analysis software (ICx Nomadics).

Staining of human cells and lines

Tumor cells (3 × 105) were washed and re-suspended in (0.1 ml) FACS buffer followed by primary incubation with RL6A TCRm at concentrations of 25 and 50 ng/ml. Isotype control antibodies (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b) were used at either 25 or 50 ng/ml to stain cells and the pan-HLA-A2 antibody, BB7.2 was used at 500 ng/ml. Cells were stained for 40 min protected from the light followed by addition of 2 ml FACS buffer to each tube and then centrifuged at 1,000 RPM for 10 min. The cell pellets were re-suspended in 0.1 ml of FACS buffer and then incubated with goat anti-mouse Ig 1:200 dilution of concentrated antibody solution (FITC or PE labeled) for 15 min protected from the light. After incubation, the cells were washed and re-suspended in 0.25 ml FACS buffer. Cells were run on FACS Canto II and analyzed using FlowJo analysis software.

Western blot analysis

Denaturing gel electrophoresis was performed with 20–50 μg of total cellular protein from cell lysates per lane and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for the detection of proteins from which peptides were identified. Commercially available anti-p68 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) for protein detection.

Human tissue procurement

The institutional review board at Hendrick Medical Center (Abilene, TX) gave approval for patient consent collection of normal and breast cancer tissue.

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor samples from each patient were placed on Cryomould, covered in OCT media, flash frozen using isopentane and dry ice and stored at −80°C until used. Tissue sections were made at 5-μm size, fixed using 5% methanol and stained with RL6A, IgG2a, BB7.2, IgG2b at 0.5 μg/ml for 1 h in diluent containing 2.5% BSA to prevent non-specific staining of tissue. Detection of primary antibody binding was determined using goat anti-mouse Ig–horseradish peroxidase (Vector Labs) that in the presence of substrate DAB provides an indicator system (formation of brown precipitate) to visualize the location of antigen/antibody binding using light microscopy. Hematoxylin QS was used as a nuclear counterstain (Vector Labs). Hematoxylin and eosin stains (Sigma) were used to assess cell morphology and tumor cell presence in tissue. Tissue sections were analyzed using light microscopy (Nikon Eclipse TE 2000, inverted, deconvolution microscope with Simple PCI Suite software, Nikon, Melville, NY).

Tetramer competition assay

In several studies, tissue staining was performed in the presence of soluble peptide/HLA-A2 tetramer to confirm specific binding of the RL6A TCRm to YLL peptide/HLA-A2 target expressed on tumor cells in tissue. Prior to the staining, RL6A TCRm and the BB7.2 mAbs at 1 μg/ml were each mixed with soluble YLL peptide/A2, KIFS peptide/A2 or ILD peptide/A2 tetramers (10 μg/ml). After 1 h, tissue was rinsed with PBS and stained with secondary antibody-peroxidase conjugate for 30 min (described above). Hematoxylin was used as a nuclear counterstain.

In vivo models

The IACUC committee at TTUHSC approved all animal studies. Athymic nude mice (Crl:NU-Foxn1nu) were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and housed under sterile conditions in barrier cages. Mice were subcutaneously injected with 5 × 106 freshly harvested MDA-MB-231 cells at 97% viability in Matrigel in the right mammary pad of mice. Matrigel provides essential nutrients for tumor cells to implant more efficiently and thus promote more rapid tumor growth. After 5 weeks, palpable tumors were detected (≥50 mm3) and mice received 5 weekly i.p. injections with either 100 μg of an isotype IgG2a control antibody (n = 5) or 100 μg of RL6A TCRm (n = 5). The RL6A TCRm and isotype control antibodies were injected into mice using a diluent of filtered sterile phosphate buffered solution. This dosage regimen followed the prophylactic and therapeutic settings for RL4B [29].

Tumor volume was measured twice weekly. Tumor volumes were calculated by assuming a spherical shape and using the following formula: volume = L × (b 2)/2 (L = longest diameter, b = shortest diameter) where the mean tumor diameter was measured in two dimensions.

Results

Direct discovery of a peptide derived from the p68 helicase protein that is common to breast tumor cell lines

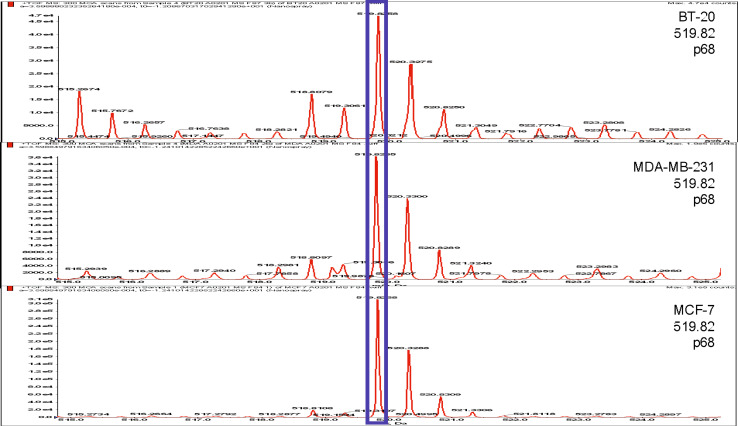

The breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 and BT-20 were transfected with the sHLA-A*0201 (HLA-A2) construct. Peptides were purified from 25 mg of harvested sHLA-A2 produced by each cell line. Comparative mapping of sHLA-A2-derived peptides was performed and the p68 RNA helicase peptide YLLPAIVHI, located at amino acid residues 128–136 of the protein and designated as the YLL peptide, was found to be expressed by the three breast carcinoma cell lines (Fig. 1). For confirmation purposes, the p68 peptide-containing fraction of each cell line was compared with synthetic p68 peptide. These data demonstrate that the YLLPAIHVI peptide is indeed loaded into the HLA-A2 peptide-binding pocket in the three human breast carcinoma cell lines investigated. Further, the peak that is prominent in the three breast cancer cell lines is minimal in the non-tumorigenic (control) mammary epithelial cell line; this, therefore, seemed like a good candidate for an over expressed peptide.

Fig. 1.

Direct discovery of p68 peptide YLLPAIVHI expressed by breast cancer cells. Ion map displaying the peptides eluted from soluble HLA-A2 complexes in three breast adenocarcinoma cell lines. Peptides were first separated by HPLC (see “Materials and methods”). In the ion map, the ion peak at 519.82 amu, highlighted with a blue box, represents the YLLPAIVHI peptide common to all three breast cancer cell lines and was identified as originating from p68

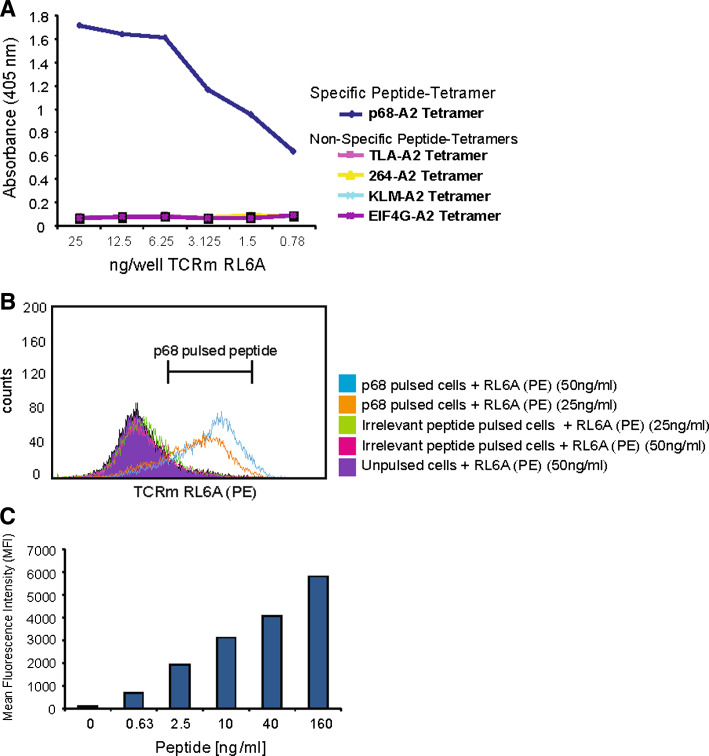

RL6A TCRm is specific for the YLL-peptide/HLA2 complex

The RL6A TCRm mAb was generated as previously described [25, 26]. To establish that the RL6A TCRm mAb isolated in the initial screening was HLA-A2 restricted and peptide-specific, a series of assays were performed to characterize its binding specificity. The first assessment used refolded peptide/HLA-A2 molecules immobilized at 1 μg/ml in wells of 96-well plate as targets for testing the RL6A TCRm in ELISA. Figure 2a shows the results of ELISA analysis of purified RL6A TCRm binding to refolded tetramer of HLA-A2/β2m loaded with YLL-peptide compared with four other HLA-A2 tetramer complexes loaded with irrelevant peptides, TLAYLIFLL, LLGRNSFEV, KLMSPKLYV and VLMTEDIKL. Significant reactivity above the background was observed for all dilutions of RL6A TCRm (ranging from 25 to 0.78 ng/well) in wells containing YLL/A2 tetramer illustrating the fine recognition specificity of the RL6A TCRm. To confirm that each well was coated the HLA-A2 conformation-specific antibody BB7.2 was used (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the binding specificity for RL6A TCRm. a Purified RL6A TCRm was used to probe wells coated with HLA-A2 tetramer refolded with the peptides indicated (CD19, TLAYLIFLL; p53 tumor suppressor protein, LLGRNSFEV; CD19, KLMSPKLYV; eIF4G, VLMTEDIKL and DEAD Box RNA helicase p68; YLLPAIVHI). Bound mAb was detected with a goat anti-mouse IgG–peroxidase conjugate and developed using ABTS substrate. b Purified RL6A TCRm (25 and 50 ng/ml) was used to stain 5 × 105 T2 cells pulsed with the irrelevant peptide (LLGRNSFEV) or specific peptide (YLLPAIVHI) or no peptide. After washing, cells were probed with a goat anti-mouse IgG–PE, washed and analyzed by flow cytometry. Counts are mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). c T2 cells were pulsed with varying levels of YLL peptide (0–160 ng/ml) and stained with 50 ng/ml RL6A TCRm followed by a secondary goat anti-mouse IgG. MFI values are shown for the various peptide concentrations

To further establish the binding specificity of RL6A TCRm for the YLL/A2 complex on the cell surface, T2 cells were either used unpulsed or pulsed with the specific peptide YLLPAIVHI or an irrelevant peptide (LLGRNSFEV) at 20 μM concentration. RL6A TCRm was used to stain cells at 25 and 50 ng/ml, respectively and the results of the study are shown in Fig. 2b. The RL6A TCRm did not stain unpulsed T2 cells or T2 cells pulsed with irrelevant peptide indicating that like the ELISA assay results RL6A TCRm binding was not due to the recognition of the heavy chain of HLA, the β2m protein or the peptide alone. Instead, the RL6A TCRm showed a strong binding signal for T2 cells pulsed only with the specific peptide (Fig. 2b) and that the signal was more intense with 50 ng/ml of TCRm. In total, RL6A TCRm did not stain T2 cells pulsed with 30 different irrelevant peptides (data not shown). These data demonstrate that RL6A TCRm is specific for the YLL peptide only in the context of HLA-A2. This point will be further expanded below.

Next, we examined the relationship between target density and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (Fig. 2c). Here, T2 cells were pulsed with decreasing concentrations of the YLLPAIVHI peptide ranging from 160 to 0.63 ng/ml followed by staining with 50 ng/ml of RL6A TCRm. The results show that RL6A TCRm staining intensity decreased in parallel with decreasing concentrations of peptide (160 ng/ml of peptide resulted in MFI >5,000; 0.63 ng/ml of peptide resulted in MFI <1,000) indicating a dependence of RL6A TCRm staining intensity on target density.

Experiments were then performed that were aimed at characterizing the binding kinetics for the RL6A TCRm. To this end, surface plasmon resonance was employed to examine the binding affinity (K D), the rates of association and dissociation and the half-life of dissociation for RL6A TCRm binding to the YLL peptide/HLA-A2 complex. The TCRm exhibited strong binding affinity (K D = 4.2 × 10−10 M) for cognate peptide/HLA-A2 complex displaying a rapid on rate (1.438 × 105) and a noticeably slow off rate (6.0 × 10−5). Further, TCRm binding to cognate peptide/HLA-A2 was characterized by a half-life of dissociation (t 1/2) of greater than 190 min. These data indicate the RL6A TCRm is endowed with favorable binding characteristics for cognate peptide/HLA-A2 complex supporting its application as a unique tumor-targeting agent.

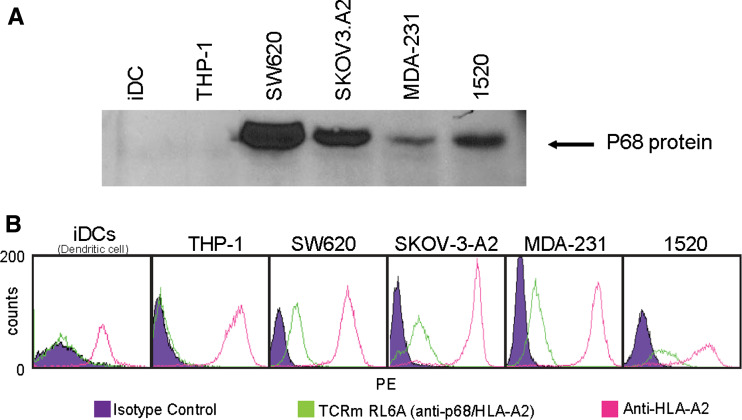

RL6A TCRm detects endogenous YLL peptide-HLA-A2 presented on human tumor cell lines

The ability of RL6A TCRm antibody to detect endogenously processed peptide in the context of the HLA-A2 molecule was evaluated by immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometric analysis using a panel of HLA-A2-positive human tumor cell lines that included MDA-MB-231 (breast), 1520 (breast), SW620 (colorectal) and SKOV-3-A2 (ovarian). In addition, THP-1 cells (a human monocytic cell line) and human iDCs (normal iDCs) were used and are HLA-A2 positive. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the cellular expression status for p68 protein. All cancer cell lines (MDA-MB-231, 1520, SW620 and SKOV-3-A2) were shown to express p68 protein, however; expression was not detected in THP-1 cells and human iDCs (Fig. 3a). The anti-HLA-A2-specific antibody, BB7.2 confirmed that the four tumor cell lines and THP-1 cells and iDCs indeed expressed HLA-A2 (Fig. 3b, pink line). Next, specific YLL/A2 epitope expression was evaluated by staining cells with the RL6A TCRm at 50 ng/ml (Fig. 3b). Only MDA-MB-231, 1520, SW620 and SKOV-3-A2 cells, which expressed both the p68 protein and HLA-A2 antigen, were positive when stained with the RL6A TCRm. In contrast, p68-negative cells, THP-1 cells and iDCs were not stained with RL6A TCRm. In addition, BT20 cells (human breast cancer cell line), used for the initial discovery of YLLPAIVHI peptide, but lacking surface expression of HLA-A2 were not stained with RL6A TCRm (data not shown). Collectively, these studies further support the conclusion that RL6A TCRm is highly specific for the YLL peptide/HLA-A2 complex.

Fig. 3.

Detection of endogenous YLLpeptide/HLA-A2 complexes by flow cytometry and immunofluorescent staining. a Western blot analysis of protein samples from cell lysates. After protein transfer, nylon membranes containing proteins were probed with an antibody specific for p68 protein. b Cell staining was performed using 50 ng/ml of isotype control, RL6A TCRm or BB7.2 antibodies on human immature DCs (iDCs), THP-1 (human monocyte cell line) and four human tumor cell lines, SW620, SKOV-3-A2, MDA-MB-231 and 1520. Antibody binding was detected using goat-anti-mouse IgG–PE conjugate. Isotype control antibody (IgG2a and IgG2b) staining is represented by the purple filled peak and represents background staining level. RL6A TCRm cell staining is indicated with green line and staining with BB7.2 mAb is shown in pink line

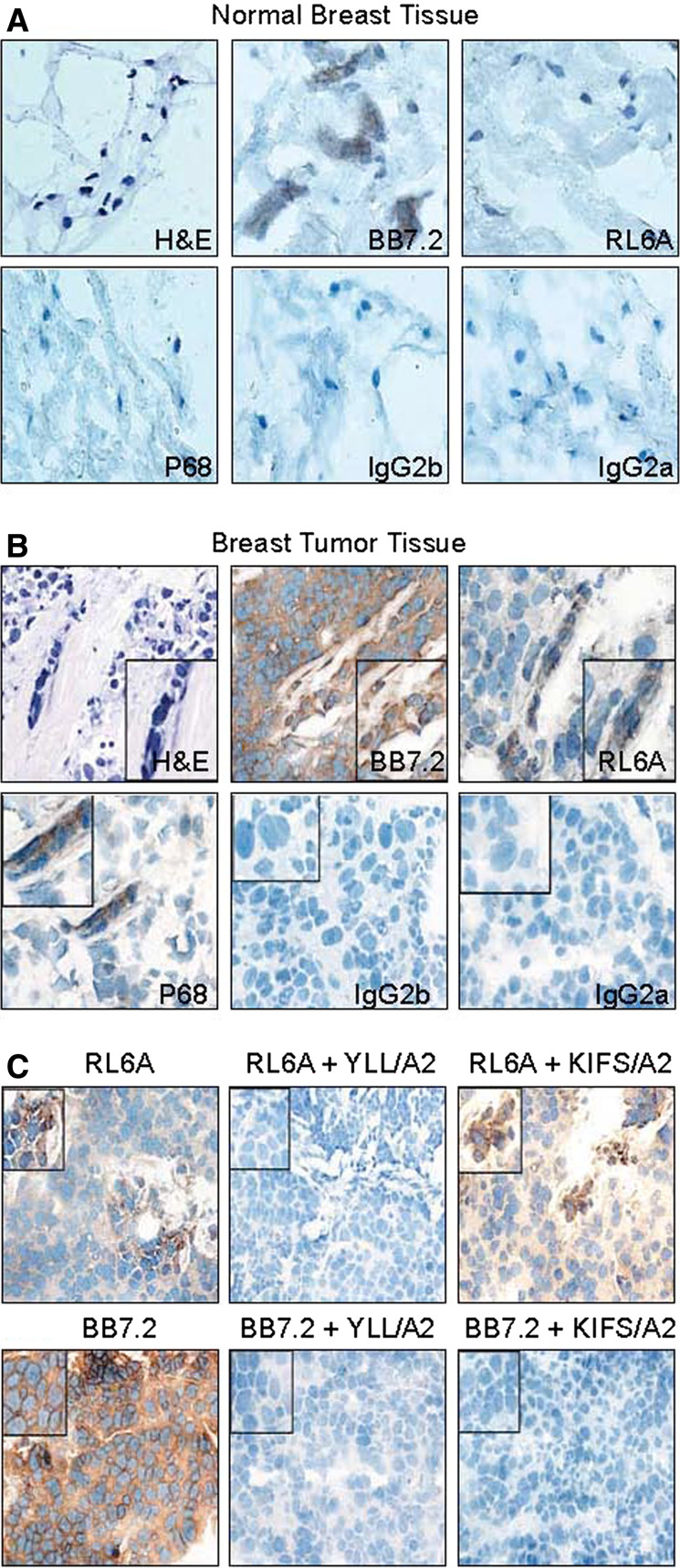

RL6A TCRm stains primary human breast tumor tissue validating the peptide-epitope discovery technology

To further validate our peptide-epitope discovery technology, it was important to demonstrate RL6A TCRm binding to epitopes on tumor cells in fresh human breast cancer tissue. A potential limitation of using human breast cancer cell lines grown in long-term culture to discover peptide epitopes is the relevance of these targets to primary breast tumor cells. To begin to address the clinical relevance of YLL/A2 epitope expression in human primary breast tumor cells, tissue was collected under an IRB protocol, flash frozen, cut into sections (5 μm thick) and stained with either isotype control antibodies, anti-HLA-A2 antibody (BB7.2 mAb) or RL6A TCRm antibody. The results are shown in Fig. 4 and demonstrate that RL6A TCRm does not stain cells in normal breast tissue (Fig. 4a), but does stain cells (shown by brown precipitate around cells) present in primary breast tumor tissue (Fig. 4b) indicating that the YLL/A2 epitope is uniquely expressed in primary tumor cells. Further, we show by H&E staining that tumor cells are present in tumor tissue and are stained using the anti-p68 mAb indicating the expression of p68 antigen (Fig. 4b). In contrast, cells in normal tissue were not stained with the anti-p68 mAb (Fig. 4a). We have examined tissue from HLA-A2-positive patients (n = 15) and all showed strong reactivity with RL6A TCRm (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

RL6A TCRm detects the YLL peptide/HLA-A2 epitope in human breast tumor tissue. Immunohistochemistry staining was performed using a normal human breast tissue and b human breast tumor tissue from the same donor. RL6A TCRm, BB7.2 and isotype control antibodies were used at 0.5 μg/ml concentration and detected using a secondary goat-anti-mouse-IgG–HRP conjugate. Chromagen substrate DAB precipitation indicates BB7.2 and TCRm binding to cells. c Competitive blocking of RL6A TCRm staining of human breast tumor tissue. RL6A was used to stain tissue alone at 0.5 μg/ml or mixed with 10 μg/ml of specific (YLL peptide/A2) or irrelevant (KIFS peptide/A2) tetramer. Tumor tissue staining with BB7.2 mAb (0.5 μg/ml) was completely blocked with 10 μg/ml of YLL peptide/A2 and KIFS peptide/A2 tetramer

To further confirm the specificity of RL6A TCRm, competitive binding assays were performed. Breast tumor tissue sections were stained with RL6A TCRm alone or in the presence of specific (YLL/A2) or irrelevant (KIFS/A2) tetramer. The findings shown in Fig. 4c demonstrate that RL6A TCRm staining was inhibited only in the presence of the YLL/A2 tetramer providing validation for the expression of the YLL/A2 epitope on primary breast cancer cells. As expected, BB7.2 mAb staining of tumor tissue sections was completely blocked with both peptide/A2 tetramers (Fig. 4c). In addition, we have examined tumor tissue from HLA-A2-negative breast cancer patients (n = 3) and shown that RL6A TCRm does not stain, indicating the specificity of the TCRm is for YLL peptide in the context of HLA-A2 (data not shown). These studies further validate our peptide-epitope direct discovery technology and indicate YLL/A2 epitope expression on primary breast cancer cells. Moreover, these findings suggest overexpressed tumor peptides by primary breast tumor cells can be discovered using cultured tumor cell lines. Finally, these data indicate that TCRm are useful reagents for validation and detection of specific peptide/HLA complexes expressed on tumor tissue.

In vivo effectiveness of RL6A TCRm using an orthotopic breast cancer model

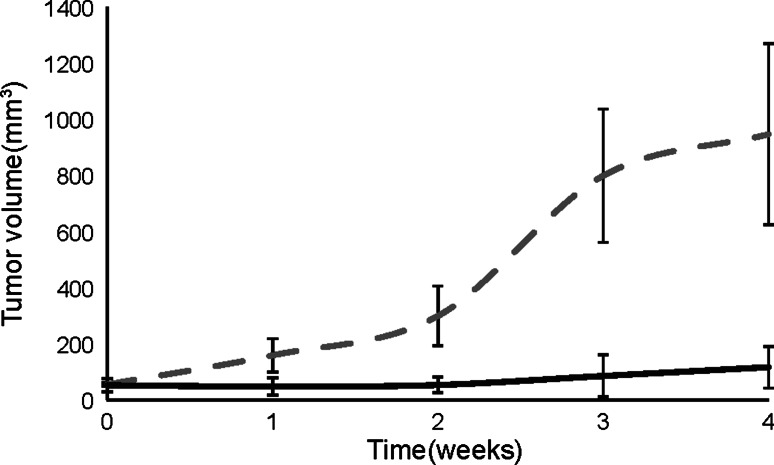

To address the therapeutic effectiveness of RL6A TCRm, we used an orthotopic breast cancer model involving athymic nude mice implanted with MDA-MB-231 tumor cells. Tumors grew until they reached palpable sizes or tumor volumes of approximately 50 mm3. Mice were treated with five weekly i.p. injections of 100 μg or ~3.0 mg/kg with isotype control antibody or RL6A TCRm. After a 5-week course of treatment, mice (n = 5) receiving weekly injections with isotype control antibody had developed tumors with mean volumes greater than 900 mm3 with tumor size observed in two mice growing to larger than 1,200 mm3. In contrast, mice treated with RL6A TCRm (n = 5) had tumors that had only grown to a mean tumor volume of 117 mm3 by week 4 after treatment with RL6A TCRm. In fact, by week 4, tumor volume was no longer measureable in two mice suggesting tumor had been completed eradicated. Mice treated with RL6A TCRm were followed for two additional weeks and still did not show signs of tumor growth demonstrating RL6A’s potent anti-tumor activity significantly impedes tumor progression and may delay relapse of tumor growth (Fig. 5). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that TCRm targeting of specific peptide/MHC complexes have potent anti-tumor effects that can significantly inhibit tumor growth and reduce tumor size in a mouse model.

Fig. 5.

RL6A TCRm inhibits tumor growth in an orthotopic breast cancer model. Athymic nude mice were implanted with 5 × 106 MDA-MB-231 tumor cells in the right mammary fat pad. Tumor cells mixed with Matrigel were implanted and allowed to grow until mean tumor volume reached >50 mm3. Mice then received a 100 μg i.p. injection with either IgG2a isotype control antibody dashed line (n = 5), or RL6A TCRm solid line (n = 5) on day 0 followed by weekly i.p. injections with 100 μg of antibody for 4 weeks. Tumor size was measured twice weekly using calipers and tumor volumes determined using the standard formula volume = L × (b 2)/2 (L = longest diameter, b = shortest diameter) where the mean tumor diameter was measured in two dimensions. Data are plotted as mean tumor volume + SEM. Study is representative of three independent studies

Discussion

We show here the direct validation of a novel T cell epitope being expressed in primary human breast tumor cells using a TCRm mAb. Furthermore, the same mAb was then used to inhibit growth of human breast tumors in an orthotopic model. These findings are important as they (1) corroborate an innovative approach to T cell epitope discovery for tumor associated or specific peptide/HLA complexes, (2) provide a direct means for validating T cell epitope expression in human tumor tissue using mAbs and (3) demonstrate the anti-tumor properties of TCRm mAbs through binding to peptide/MHC complexes.

To date, several hundred human TAAs have been described [30]. The discovery of tumor associated/specific T cell epitopes has relied primarily on indirect strategies that make use of gene and protein expression profiling combined with predictive algorithms and in vitro peptide-binding assays [31]. The experience with tumor antigens is that <50% of predicated peptide epitopes can actually be used to generate CTL that kill tumors in vitro [31, 32]. Moreover, a direct association has not been established between expression and peptide-epitope presentation by MHC molecules [24]. Alternatively, discovery of peptide epitopes using direct strategies has identified unique and specific peptides [18]. However, a number of factors including amounts of peptide that can be recovered from the elution phase, the complexity of the tissue samples (malignant and healthy cells) used to elute and isolate peptides, the quality of peptide preparations and the sensitivity limits of the instrumentation hamper direct discovery strategies. A major advance for direct discovery is the development of technology that relies on the production of large amounts of soluble HLA/peptide complexes that until recently had been limited to the identification of peptides for infectious agents [20, 33, 34]. Here, stable breast tumor cell transfectants expressing high concentrations of sHLA were used to discover the p68 peptide YLLPAIHVI presented in the context of HLA-A*0201; a strategy recently used by our group to discover other breast cancer peptide/HLA-A2 epitopes [19]. A potential limitation for this strategy was that we might not discover peptides expressed in primary tumor cells using cultured tumor cell lines because long-term cultured tumor cells may lose attributes common to the primary tumor cells. Another concern has been whether long-term cultured cells express different T cell epitopes than primary tumors. Therefore, because the discovery strategy used in this report makes use of tumor cell lines to directly identify peptide epitopes, it was necessary to validate the YLL peptide-epitope on primary breast tumor tissue using the RL6A TCRm. Thus, it was important to establish that the RL6A TCRm, which stained cultured tumor cell lines from which it was originally discovered also stained frozen tissue sections of breast cancer and lymph nodes from patients with metastatic breast cancer.

The target of RL6A TCRm is an RNA helicase protein. These proteins are part of a large family of highly conserved intracellular proteins, the so-called D (Asp) E (Glu) A (Ala) D (Asp) DEAD box family of putative helicases [35]. The p68 RNA helicase belongs to this family of DEAD box proteins and potentially plays a number of critical physiological roles [36–41]. In addition, p68 has been widely implicated in tumor cell growth regulation and tumor development [42]. Overexpression of p68 has been observed in many cancers and post-translational modification by ubiquitination and phosphorylation of p68 has been implicated in tumor development and cell proliferation/transformation [43, 44]. Hunt et al. [18] first discovered the YLLPAIVHI peptide in transformed human B cells. It is conceivable that peptides such as YLLPAIHVI from p68 are readily translocated into the lumen of the ER and loaded into the binding pocket of HLA-A*0201. Our findings with RL6A TCRm staining of p68 antigen-positive human breast tumor tissue and its specific blocking with soluble YLL/A2 tetramer but not control tetramer indicates that p68 YLL peptide/HLA-A2 complexes are expressed on primary tumor cells. In addition, evidence for YLL/A2 expression on cancer cells is supported by the absence of RL6A TCRm staining of normal human breast tissue and tissue from HLA-A2-negative breast cancer patients. Detection of the YLL peptide/HLA-A2 on the surface of tumor cell lines and primary tumor cells with RL6A TCRm supports the view that the YLL peptide/HLA-A2 complex is a putative tumor associated/specific epitope. Thus, these findings validate the discovery strategy of using tumor cell lines and can now be applied to directly identify peptide epitopes expressed in primary and metastatic breast cancer cells to assist in the development of new immunotherapy strategies that include T cell eliciting vaccines, adoptive T cell therapies and TCRm mAbs.

Two distinctly different strategies have been used to generate anti-peptide/MHC antibodies. On the one hand, phage display has been used to generate murine and human Fabs from immunized and non-immunized libraries [45, 46]. On the other hand, our strategy for making antibody to specific peptide/MHC complexes led to the generation of RL6A TCRm, which relied on immunization and classical hybridoma technology [24, 25]. A significant benefit of our approach is that the TCRm antibodies routinely have high-binding affinity and avidity and retain the ability to activate immune effector functions. Furthermore, tumors treated with the RL6A TCRm remained small and did not return even 4 weeks after stopping treatment. This raises the possibility that the TCRm had successfully killed the entire tumor.

In conclusion, we show the ability to directly discover and then validate an epitope on primary human breast tumor tissue using a TCRm mAb. This work is significant because it provides the first evidence for an integrated discovery and validation strategy that can be used for the direct visualization of T cell epitopes in tumor tissue. This strategy has not been employed previously but could ultimately provide significant insight into the peculiarities of peptide-epitope expression in tumor cells. Finally, these results indicate TCRm are promising agents for cancer detection and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. William P. Weidanz for critical discussion of the data. We thank Dr. Stephen Wright and Dr. Piotr Tabaczewski for his assistance with the mouse models and Dr. Kathryn Norton for tissue acquisition.

Conflict of interest statement

Jon A. Weidanz is Chief Scientist and founder of Receptor Logic, Inc., Abilene, Texas, 79601. Study was supported in part by Receptor Logic, Inc.

References

- 1.Weiner LM, Belldegrun AS, Crawford J, Tolcher AW, Lockbaum P, Arends RH, Navale L, Amado RG, Schwab G, Figlin RA. Dose and schedule study of panitumumab monotherapy in patients with advanced solid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:502–508. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halama N, Herrmann C, Jaeger D, Herrmann T. Treatment with cetuximab, bevacizumab and irinotecan in heavily pretreated patients with metastasized colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:4111–4115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, Dong W, Sargent D, Hedrick E, Kozloff M. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5326–5334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabbinavar F, Irl C, Zurlo A, Hurwitz H. Bevacizumab improves the overall and progression-free survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with 5-fluorouracil-based regimens irrespective of baseline risk. Oncology. 2008;75:215–223. doi: 10.1159/000163850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartwright T, Kuefler P, Cohn A, Hyman W, Berger M, Richards D, Vukelja S, Nugent JE, Ruxer RL, Jr, Boehm KA, et al. Results of a phase II trial of cetuximab plus capecitabine/irinotecan as first-line therapy for patients with advanced and/or metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:390–397. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2008.n.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang K, Lu Y, Jin W, Ang KK, Milas L, Fan Z. Sensitization of breast cancer cells to radiation by trastuzumab. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1113–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baselga J, Norton L, Albanell J, Kim YM, Mendelsohn J. Recombinant humanized anti-HER2 antibody (Herceptin) enhances the antitumor activity of paclitaxel and doxorubicin against HER2/neu overexpressing human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2825–2831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shastri N, Schwab S, Serwold T. Producing nature’s gene-chips: the generation of peptides for display by MHC class I molecules. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:463–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brodsky FM, Lem L, Bresnahan PA. Antigen processing and presentation. Tissue Antigens. 1996;47:464–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1996.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander RB, Brady F, Leffell MS, Tsai V, Celis E. Specific T cell recognition of peptides derived from prostate-specific antigen in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 1998;51:150–157. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfel T, Hauer M, Klehmann E, Brichard V, Ackermann B, Knuth A, Boon T, Meyer Zum Buschenfelde KH. Analysis of antigens recognized on human melanoma cells by A2-restricted cytolytic T lymphocytes (CTL) Int J Cancer. 1993;55:237–244. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahl A, Weidanz J, Hildebrand W. Direct class I HLA antigen discovery to distinguish virus-infected and cancerous cells. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2006;3:641–652. doi: 10.1586/14789450.3.6.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler JH, Melief CJ. Identification of T-cell epitopes for cancer immunotherapy. Leukemia. 2007;21:1859–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson J, Waller MJ, Parham P, de Groot N, Bontrop R, Kennedy LJ, Stoehr P, Marsh SG. IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:311–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson J, Marsh SG. HLA informatics: accessing HLA sequences from sequence databases. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;210:3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaramillo A, Majumder K, Manna PP, Fleming TP, Doherty G, Dipersio JF, Mohanakumar T. Identification of HLA-A3-restricted CD8+ T cell epitopes derived from mammaglobin-A, a tumor-associated antigen of human breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2002;102:499–506. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg SA. Development of cancer immunotherapies based on identification of the genes encoding cancer regression antigens. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:1635–1644. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.22.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt DF, Henderson RA, Shabanowitz J, Sakaguchi K, Michel H, Sevilir N, Cox AL, Appella E, Engelhard VH. Characterization of peptides bound to the class I MHC molecule HLA-A2.1 by mass spectrometry. Science. 1992;255:1261–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.1546328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins OE, Vangundy RS, Eckerd AM, Bardet W, Buchli R, Weidanz JA, Hildebrand WH. Identification of breast cancer peptide epitopes presented by HLA-A*0201. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:1445–1457. doi: 10.1021/pr700761w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hickman HD, Luis AD, Buchli R, Few SR, Sathiamurthy M, VanGundy RS, Giberson CF, Hildebrand WH. Toward a definition of self: proteomic evaluation of the class I peptide repertoire. J Immunol. 2004;172:2944–2952. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prilliman KR, Jackson KW, Lindsey M, Wang J, Crawford D, Hildebrand WH. HLA-B15 peptide ligands are preferentially anchored at their C termini. J Immunol. 1999;162:7277–7284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen PS, Stryhn A, Hansen BE, Fugger L, Engberg J, Buus S. A recombinant antibody with the antigen-specific, major histocompatibility complex-restricted specificity of T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1820–1824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong G, Reis e Sousa C, Germain RN. Antigen-unspecific B cells and lymphoid dendritic cells both show extensive surface expression of processed antigen-major histocompatibility complex class II complexes after soluble protein exposure in vivo or in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;186:673–682. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weidanz JA, Nguyen T, Woodburn T, Neethling FA, Chiriva-Internati M, Hildebrand WH, Lustgarten J. Levels of specific peptide–HLA class I complex predicts tumor cell susceptibility to CTL killing. J Immunol. 2006;177:5088–5097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weidanz JA, Piazza P, Hickman-Miller H, Woodburn D, Nguyen T, Wahl A, Neethling F, Chiriva-Internati M, Rinaldo CR, Hildebrand WH. Development and implementation of a direct detection, quantitation and validation system for class I MHC self-peptide epitopes. J Immunol Methods. 2007;318:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prilliman K, Lindsey M, Zuo Y, Jackson KW, Zhang Y, Hildebrand W. Large-scale production of class I bound peptides: assigning a signature to HLA-B*1501. Immunogenetics. 1997;45:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s002510050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei ML, Cresswell P. HLA-A2 molecules in an antigen-processing mutant cell contain signal sequence-derived peptides. Nature. 1992;356:443–446. doi: 10.1038/356443a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Davis MM. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittman VP, Woodburn D, Nguyen T, Neethling FA, Wright S, Weidanz JA. Antibody targeting to a class I MHC-peptide epitope promotes tumor cell death. J Immunol. 2006;177:4187–4195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novellino L, Castelli C, Parmiani G. A listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells: March 2004 update. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:187–207. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0560-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark CE, Vonderheide RH. Getting to the surface: a link between tumor antigen discovery and natural presentation of peptide–MHC complexes. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5333–5336. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosca PJ, Hobeika AC, Clay TM, Morse MA, Lyerly HK. Direct detection of cellular immune responses to cancer vaccines. Surgery. 2001;129:248–254. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.108609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wahl A, Schafer F, Bardet W, Buchli R, Air GM, Hildebrand WH. HLA class I molecules consistently present internal influenza epitopes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:540–545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811271106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsons R, Lelic A, Hayes L, Carter A, Marshall L, Evelegh C, Drebot M, Andonova M, McMurtrey C, Hildebrand W, et al. The memory T cell response to West Nile virus in symptomatic humans following natural infection is not influenced by age and is dominated by a restricted set of CD8+ T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 2008;181:1563–1572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heinlein UA. Dead box for the living. J Pathol. 1998;184:345–347. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199804)184:4<345::AID-PATH1243>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Endoh H, Maruyama K, Masuhiro Y, Kobayashi Y, Goto M, Tai H, Yanagisawa J, Metzger D, Hashimoto S, Kato S. Purification and identification of p68 RNA helicase acting as a transcriptional coactivator specific for the activation function 1 of human estrogen receptor alpha. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5363–5372. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Rossler OG, Hloch P, Schutz N, Weitzenegger T, Stahl H. Structure and expression of the human p68 RNA helicase gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:932–939. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.4.932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicol SM, Causevic M, Prescott AR, Fuller-Pace FV. The nuclear DEAD box RNA helicase p68 interacts with the nucleolar protein fibrillarin and colocalizes specifically in nascent nucleoli during telophase. Exp Cell Res. 2000;257:272–280. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitamura A, Nishizuka M, Tominaga K, Tsuchiya T, Nishihara T, Imagawa M. Expression of p68 RNA helicase is closely related to the early stage of adipocyte differentiation of mouse 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:435–439. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu ZR. p68 RNA helicase is an essential human splicing factor that acts at the U1 snRNA-5’ splice site duplex. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5443–5450. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5443-5450.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bates GJ, Nicol SM, Wilson BJ, Jacobs AM, Bourdon JC, Wardrop J, Gregory DJ, Lane DP, Perkins ND, Fuller-Pace FV. The DEAD box protein p68: a novel transcriptional coactivator of the p53 tumour suppressor. EMBO J. 2005;24:543–553. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Camats M, Guil S, Kokolo M, Bach-Elias M. P68 RNA helicase (DDX5) alters activity of cis- and trans-acting factors of the alternative splicing of H-Ras. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang L, Lin C, Liu ZR. Phosphorylations of DEAD box p68 RNA helicase are associated with cancer development and cell proliferation. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:355–363. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Causevic M, Hislop RG, Kernohan NM, Carey FA, Kay RA, Steele RJ, Fuller-Pace FV. Overexpression and poly-ubiquitylation of the DEAD-box RNA helicase p68 in colorectal tumours. Oncogene. 2001;20:7734–7743. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denkberg G, Reiter Y. Recombinant antibodies with T-cell receptor-like specificity: novel tools to study MHC class I presentation. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen CJ, Sarig O, Yamano Y, Tomaru U, Jacobson S, Reiter Y. Direct phenotypic analysis of human MHC class I antigen presentation: visualization, quantitation, and in situ detection of human viral epitopes using peptide-specific, MHC-restricted human recombinant antibodies. J Immunol. 2003;170:4349–4361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]