Abstract

The treatment of myeloid leukaemia has progressed in recent years with the advent of donor leukocyte infusions (DLI), haemopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) and targeted therapies. However, relapse has a high associated morbidity rate and a method for removing diseased cells in first remission, when a minimal residual disease state is achieved and tumour load is low, has the potential to extend remission times and prevent relapse especially when used in combination with conventional treatments. Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) are heterogeneous diseases which lack one common molecular target while chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) patients have experienced prolonged remissions through the use of targeted therapies which remove BCR-ABL+ cells effectively in early chronic phase. However, escape mutants have arisen and this therapy has little effectivity in the late chronic phase. Here we review the immune therapies which are close to or in clinical trials for the myeloid leukaemias and describe their potential advantages and disadvantages.

Keywords: Myeloid leukaemia, Immunotherapy, Tumour associated antigens, Cancer-testis antigens, SEREX, cDNA microarray

Introduction

Donor leukocyte infusion (DLI) [61] provides proof of principal that cancer immunotherapy can work in leukaemia in the allogeneic setting. DLIs are administered to patients who have had a transplant and are showing signs of relapse. The administration of immune cells to the periphery seems to boost the graft versus leukaemia (GvL) effect, and particularly for CML patients, has elicited good response rates. However, this therapy is only effective for a small group of patients who are eligible for transplant. It has not been as successful for the treatment of AML and is rarely used in MDS. Additional therapies are required to prevent relapse, or extend remission, for myeloid leukaemias and should be used to complement existing therapies such as chemotherapy, DLI and targeted therapies.

Recent advances in proteomics have aided the identification of tumour antigens in myeloid leukaemia and the progress of a number of ongoing immunotherapy clinical trials have provided objective responses in older and refractory patients, with few other treatment options. MDS predominantly affects the elderly and has until recently had few therapies other than supportive care (reviewed in [50]). Approximately 40% of patients transform from MDS to AML and this is believed to be the natural progress of the disease for all surviving patients. In the last 5 years reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) HSC transplant regimens have been used to treat a range of haematological malignancies and have been shown to be safe and effective in patients with low tumour burdens (reviewed in [70]). For patients who are not eligible for RIC HSC or for whom this treatment fails, immunotherapy is an, as yet, little investigated but potentially very promising therapy, due to the low tumour burden associated with this disease.

Acute myeloid leukaemia also describes a very heterogeneous group of diseases, the diagnosis of which are based primarily on morphological and cytochemical criteria, and classified most recently by the WHO system which takes into account additional clinically relevant factors such as genetics and immunophenotype (reviewed in [78]). Five year survival for the under 60 age group, who are most likely to be eligible for HSCT is 50%, while survival rates for the over 60 age group are approximately 11% at this time point [43]. Major improvements in HSCT (reviewed in [47]) continue to enhance survival rates although these are only available to patients under 60 years of age, based on health and donor availability grounds, while the median age for AML is 63.

Chronic myeloid leukaemia is characterised by the Philadelphia chromosome which results from the t(9;22) translocation and leads to the production of the BCR-ABL protein. This confers a failure of the blast cells to die, in addition to an increased proliferation rate and growth factor independence, which leads to a fatal outgrowth of the diseased cells. To date the most effective treatment for CML has been allogeneic HSCT. However, the recent development of small molecule therapies, such as imatinib, which exquisitely targets the BCR-ABL protein product have the potential to be curative (reviewed in [38, 80]). Despite promising results with imatinib in the early chronic phase of disease, treatment at the later stages, when the disease is most likely to progress to blast crisis (the AML-like stage of disease), still lacks an effective therapy.

In this review we discuss the latest developments in antigen identification, some of the modes of immunotherapy being studied and early stage clinical trials which are proving very promising. Wherever, possible human studies are described and where not available murine studies are described and identified as such.

Immune inhibitory effects of myeloid cells

Like all cancer cells, myeloid leukaemia cells evade the immune system through a system of “immune” and “tumour editing” (reviewed in [11]). In addition supernatant from AML myeloblasts have been shown to secrete inhibitory factors which prevent peripheral T cell activation [5]. Similar effects of myeloid cells in other cancers have also been observed (reviewed in [71]). In the following sections we detail the ways in which immunotherapy can be used to overcome this immune inhibition and induce anti-leukaemic effects.

Whole cell therapies

Whole cell vaccines offer the opportunity to treat patients with autologous cells which have been genetically modified to induce an immune response. These transferred genes confer elevated MHC, co-stimulatory molecule, antigen or cytokine expression and in doing so, have been shown in vitro to induce effective T cell responses. However, for the myeloid leukaemias one of the main difficulties associated with physical methods of gene transfer, such as electroporation and lipofection, have been low gene transfer frequencies and high cell death rates. Viral vectors such as retrovirus and adenovirus have poor transduction rates in primary leukaemic blast cells. Retroviruses need to infect cycling cells to access the nucleus, when its membrane dissolves during mitosis, and blast cells rarely cycle ex vivo. Adenoviruses require the CAR receptor for infection and primary AML cells infrequently express it. In contrast lentiviral vectors have been shown to infect primary AML cells with high transduction efficiencies and have high levels of associated transgene expression ([10, 37] and reviewed in [11, 14]). Chan et al. [10] and Koya et al. [37] both showed that autologous and allogeneic T cells could respond to genetically modified AML cells which expressed B7-1 and/or IL-2 or GM-CSF, respectively. Chan et al. [10] also showed that T cells stimulated with these modified AML cells could then proliferate in response to unmodified AML blasts, but not remission bone marrow. Of note, N. Hardwick, W. Ingram, L. Chan and F. Farzaneh, submitted, have now shown that allogeneic effector cells (from healthy donor or AML patients) stimulated with IL-2/B7.1 modified AML blasts can induce the lysis of unmodified AML blasts and that these effector cells had higher lytic activity than cells stimulated with AML cells expressing B7.1 or IL-2 alone. One of the major limitations associated with whole cell vaccines has been the difficulty in expanding AML cells ex vivo. However, most AML patients have very high blast numbers at presentation and the highly efficient gene transfer rates achieved using lentiviral vectors make this less of an issue. A clinical trial is now starting at King’s College Hospital in which AML patients in first remission post-HSCT will receive irradiated autologous tumour cells, modified to express B7-1 and IL-2 (detailed in [11]). It is hoped that these modified tumour cells will stimulate allogeneic T cells from the graft and induce tumour killing.

Concerns regarding whole cell vaccines include the requirement to genetically modify cancer cells to express transgene(s), potential changes in leukaemia associated antigen (LAA) expression caused by ex vivo culture and the need to assure patients and clinical trial regulatory bodies of the total inviability of these cells before their return to patients. In addition autologous whole cell vaccines need to be made for each individual. However, whole cell vaccines benefit from circumventing the need to identify individual tumour antigens and in diseases as heterogenous as AML and MDS this is truly advantageous.

Cytogenetic rearrangements and leukaemia specific antigens

Until recently most antigens in leukaemias were found through methods which originally identified mutated genes or chromosomal translocations, whose products were later shown to be effective antigenic targets when presented on MHC [57, 59]. For example acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) is characterised by the t(15;17) translocation which leads to production of the chimeric PML-RARα protein. Treatment of APL with the differentiation agent all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) has been one of the most effective therapies used to treat any single subgroup of AML (a detailed review of targeted immunotherapies for AML is available in [65]). Recently, Padua et al. [57] showed that in a mouse model of APL they could use a DNA vaccine containing the PML-RARα oncogene and tetanus fragment C (FrC) sequences to cause increased survival times when used alone or in combination with ATRA. A phase I clinical trial is being initiated based on these data.

However, across all subgroups of AML and MDS, no one translocation occurs very frequently, APL accounts for 7–10% of all AMLs and the t(15;17) translocation is one of the most frequent cytogenetic rearrangements in AML. In contrast in CML, the BCR-ABL protein derived from the t(9;22) translocation is found in more than 95% of patients at diagnosis. Small molecule therapy of CML with imatinib mesylate/Glivec (reviewed in [38, 80]) has led to the effective extension of the chronic phase of the disease for many patients. However, some patients are resistant to the drug from the outset of treatment and others develop resistance with treatment. Both forms of resistance are caused by the existence of BCR-ABL+ cells which express mutated forms of BCR-ABL protein. Targeted therapies against these escape mutants are being assessed and include small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors of native and mutant BCR-ABL, Abl and SRC/ABL.

The breakpoint regions of the BCR-ABL translocation provides cancer specific antigens whose products can be targeted for immunotherapy [15]. In two studies T cells from CML patients were shown to be able to respond against the peptide identified and lyse autologous CML cells, while tetramer staining demonstrated the presence of circulating BCR-ABL specific T cells [7, 59]. Phase I and II clinical trials using a mixture of five b3a2 derived peptides and the immunological adjuvant QS-21, led to peptide specific T cell responses but no signs of tumour regressions. More recently Bocchia et al. [4] used a vaccine against the BCR-ABL breakpoint alongside conventional treatments of either imatinib or interferon alpha to treat CML patients with stable residual disease. They showed that most patients vaccinated with CML100VAX had an anti-tumour response and that most vaccinated patients had a consistent reduction in their cytogenetic disease.

Adoptive immunotherapy for the myeloid leukaemias

The use of DLI has had beneficial effects in some AML patients [36] believed to be due to the GvL effects aided by leukaemia-derived dendritic cells (DCs) in the recipient. This belief has been supported by the improved GvL response seen in patients concurrently treated with cytokines. A number of groups have been expanding bone marrow blast or monocyte derived DCs from leukaemia patients for clinical trials for the adoptive therapy of AML (reviewed in [64]). These derivative professional antigen presenting cells (APCs) present at least some of the same LAAs as the ‘parental’ leukaemic cells [40] and enhance anti-leukaemia responses in vivo. Although monocyte and blast derived DCs cannot be generated from all AML and MDS patients (variation also depends on subclass), when achieved these DC have been shown to be functionally active and may themselves be used for adoptive therapies or to prime T cells [39]. Leukaemia-reactive cytotoxic T-cells (CTLs) have been expanded ex vivo in response to autologous AML cells which have been differentiated into DCs. These CTLs show cytolytic activity against autologous leukaemia blasts but not other AML cell lines or autologous monocytes and the response was shown to be MHC class-I restricted. In addition, the use of DCs to stimulate T cells from healthy donors or patients to respond against AML cells have been performed using various techniques to generate DCs which present LAAs. These include the pulsing of DCs with leukaemic cells that have been irradiated, lysed or made to apoptose, or the DCs have been fused with AML cells or loaded with RNA or peptides from specific LAAs (reviewed in [18]).

Schirrmann and Pecher [69] modified a human natural killer (NK) cell line, YT, through the gene transfer of a humanised chimeric immunoglobulin T cell receptor targeting CD33. YT cells could then specifically lyse the human AML cell line KG1. Potentially this could be provide an unlimited resource for the immunotherapy of AML, as NK cells do not have the host MHC specificity requirements that CTLs do, while the CD33 modification of the NK cells would make them specific for CD33 expressing cells.

Recent studies have shown the potential of T cell receptor (TCR) modified T cells in terms of conferring long-term patient survival. Clinical responses (partial responses) were shown in two patients treated with these modified cells with melanoma [51] in a trial involving 17 patients. This shows the feasibility and more importantly the safety of this treatment for patients but also raises the issue of the clinical response being limited. Xue et al. [84] has modified the TCR in mouse models of leukaemia and shown that T cells modified to express a WT1 specific T cell receptor could kill WT-1 positive BV173 leukaemia cell line cells in nude mice. Tsuji et al. [76] generated TCR gene-modified Tc1 cells which showed cytotoxicity and IFNγ production in response to freshly isolated leukemia cells expressing both WT1 and HLA-A24. Marijt et al. [46] showed that the haemopoiesis restricted minor histocompatability antigens HA-1 and HA-2 may serve as target tumour antigens for alloreactive T cells following DLIs. They showed the emergence of HA-1- and HA-2-specific T cells, 5–7 weeks following DLI which were associated with GvL reactivity and resulted in a durable remission. A more comprehensive review of tumour specific T cell therapies is available elsewhere [52].

Antibody therapy of myeloid leukaemia

Some surface antigens with disease specific expression are very effective targets for antibody (Ab)-based therapies. CD33 has been targeted by Ab therapies for the treatment of AML (reviewed in [53]), the most promising results having been obtained with a humanised IgG4 anti-CD33 Ab conjugate known as Mylotarg™. As a single agent this product has been able to induce remissions in patients with relapsed AML and shown promising results in combination with standard chemotherapy for the treatment of newly diagnosed AML. The humanised HuM195 Ab against CD33 has shown no anti-leukaemic effect against relapsed or refractory leukaemia, probably due to the large amount of CD33 being expressed on cells in those patients. However, this Ab can remove residual leukaemic cells, detectable by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, in patients in remission with APL. A humanised Ab (IMCEB10) targeting FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) [41] has recently been described as having anti-FLT3 effects on leukaemic cell lines in vitro and in xenograft models. Other Abs are being examined for their possible targeting as a treatment for AML including anti-PML and anti-CD44 for APL. In the clinic Abs which are conjugated to high dose β-emitters can aid bone marrow clearance prior to transplantation, while α-emitters can selectively kill leukaemic cells while potentially leaving surrounding normal cells intact (reviewed in [53]).

In the myeloid leukaemias, the targeting of the cytokine tumour necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), as well as agonistic antibodies that bind to the TRAIL receptors, death receptor 4 (DR4) and DR5, are undergoing preclinical and early clinical evaluations as a therapeutic agents for a number of malignancies including MDS and AML (reviewed in [34]). TRAIL has been suggested to play a role in MDS-associated apoptosis, while TRAIL has been shown to induce apoptosis in AML blasts and inhibit the growth of AML blast colonies in vitro (reviewed in [34]). DR4 and DR5 overexpression has been found in the vast majority of AML samples making this a promising target for anti-TRAIL receptor therapies.

Deciphering the leukaemic immunome

Two modes of identifying tumour antigens as targets for immunotherapy exist. Reverse immunology whereby immunogenic peptides which bind to specific haplotypes are predicted using mathematical programs such as SYFPEITHI (http://www.syfpeithi.de/), PraProC (http://www.paproc.de/) or BIMAS (http://www.bimas.dcrt.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/). When the dissociation half life from the MHC of interest are predicted to be high enough, usually determined using at least two of the web based available programs, and if the peptide is shown to be specific to the antigen of interest through NCBI blast searches (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/), then the peptide is ordered and tested for immunogenicity in T2 binding assays, MLRs, IFNγ ELISAs and ELIspot for granzyme B or IFNγ [19, 60]. In contrast direct immunology predicts immunogenicity based on primary data such as elution from MHC molecules using mass spectrometry [15, 35]. Both types of immunology have been used to define immunogenic epitopes in the myeloid leukaemias, examples cited.

Several techniques have rapidly advanced our knowledge of the leukaemic immunome (a collective term for the antigens recognized by the immune system) in the last decade. In 1995, Sahin et al. [66] devised the serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries (SEREX) technique. SEREX has few limitations with regards to patient material and has been shown to be effective in the identification of more than 2,000 tumour antigens in a range of malignancies (http://www2.licr.org/CancerImmunomeDB/) (reviewed in [31]). These SEREX-defined antigens have been shown to be able to stimulate simultaneous CD4+, CD8+ and Ab responses against SEREX-defined tumour antigens in patients [16, 32]. SEREX has also been used to identify a number of known and novel antigens in AML [13, 21, 22, 25] (Table 1) and CML [22, 25].

Table 1.

Antigens identified as possible targets for the immunotherapy of AML

| Antigen | Expression | Specificity of expression | Technique(s) identified by | Immunotherapeutic use for AML |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAGE | 27% AMLs at presentation [23] | CT Ag |

CTL recognition RT-PCR [23] |

NK |

| BCL-2 | Overexpressed on many CAs, Elevated expression on AML | TAA | Cytogenetics | CTLs in AML patients and not normal donors [2] |

| CD33 | 80% AML blasts but not pluripotent stem cells | LAA | Indirect immuno-fluoresence |

Peptide vaccine [3] Modified NK [69] Ab therapy [53]a |

| FLT3 | Gene most frequently mutated in AML [14]a | LAA | Well known role in physiological haemopoiesis | Ab therapy [41] |

| G250 | RCC, 51% AML [23] | TAA |

CTL responses in RCC RT-PCR [23] |

NK |

| HAGE | 23% of AMLs at presentation [1] | CT Ag |

Representation difference analysis RT-PCR [1] |

Peptide stimulation of T cellsb |

| hTERT | 28% AML [23] | TAA |

Identified as a catalytic subunit of telomerase RT-PCR [23] |

NK |

| MAGE-A1 | Testis, melanoma 8% AML [1] | CT Ag [14] |

T cell responses SEREX RT-PCR [1] |

NK |

| MAZ | 44% AMLs, 8% normal donors [21] | LAA |

Library cloning SEREX [21] |

NK |

| MLAA-2 (RHAMM-like protein) | Serological responses in 61% AML patients, not normal donors [13] | LAA | SEREX [13] | NK |

| MPP11 | 37% AML, no normal donors [22] | CT Ag |

Physical mapping of a deletion site RT-PCR [23] SEREX [22] |

NK |

| Oncofetal antigen-immature laminin receptor (OFA-iLRP) | Preferential expression in fetal tissue and many types of CA Normal BM low, most leukaemias high | LAA |

Biochemical studies Immunological studies |

Stimulation of OFA-iLRP specific CTLs with OFA-iLRP+ DCs and AML cell lysis [73] |

| PASD1 | 30% AML, 16% CML [25], DLBCL | CT Ag | SEREX [25] | MRNA electroporated DCs stimulate normal donor autologous T cells [25] |

| PML-RARα | Leukaemic blasts of APL | Disease specific | Cytogenetics | DNA vaccine [57]c |

| PRAME | High expression on subsets of AML | LAA |

CTL recognition |

PRAME+ cells susceptible to CTL lysis [49]a |

| Proteinase 3 | Normal promyelocytes, myelocytes, metamyelocytes, band forms, neutrophils (polymorphonuclear), AML M2, M3, 50% M4, 15% M5 | LAA | Originally described in microbiological organisms |

Spontaneous T cells in humans [77]a |

| RAGE-1 | 21% AML at presentation [27] | TAA | Microarray [27] | CTL and T cell responses shown against peptides in RCC |

| RHAMM | Tumour restricted 70% AML by RT-PCR [23] | LAA | Molecular cloning RT-PCR [23] SEREX [21, 25] | RHAMM stimulated CD8+ T cell responses against RHAMM pulsed T2 cells [20] |

| SYCP1/ SCP1 | 5.7% of AMLs [40] | CT Ag | Biologically active peptides—effect on porcine spinal cord RT-PCR [42] Microarray [27] | NK |

| SLLP1 | 22% of AMLs [82] | CT Ag | Biochemical isolation RT-PCR [82] | NK |

| SPAN-Xb/ CTP11 | Testis, MM, CLL, 1 of 2 AML, 2 of 7 CML [81] | CT Ag | RT-PCR [81] Microarray [27] | NK |

| Survivin | AML, CML, variety liquid and solid tumours | TAA | NK | T cell and Ab responses against epitopes lead to AML [72] |

| TRAIL | Overexpressed in AML [34]a | TAA | RT-PCR [34]a | Agonistic Ab [34]a |

| WT-1 | Overexpressed on 60-70% adult AML cells [17] | LAA | Cytogenetics RT-PCR [17] Spontaneous T cells in humans [55] | Peptide vaccines [45, 55, 68] |

CA cancer; RCC renal cell carcinoma; MM multiple myeloma; CLL chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NK not known; CT Ag Cancer-testis antigen; TAA tumour associated antigen

aReview

bKnights, University of Tuebingen, Germany, Personal communication

cMouse model

Microarray analyses of gene expression has provided a powerful tool to characterise the molecular mechanisms underlying many cancers including leukaemia. With regards to AML, cDNA microarray analysis has allowed the identification of genes that are differentially expressed in leukaemic blasts, as compared to normal haemopoietic lineages, which can then indicate prognosis, show the gene expression effects of varying treatment regimes and identify the genes involved in the processes underlying disease (reviewed in [6]). Recently, microarray was used to identify LAAs, and predominantly cancer specific antigens, which were expressed in AML cells but not equivalent normal donor cells [27], including RAGE-1 expression which was found in 21% of the 124 AML samples analysed.

Gene expression profiling has provided diagnostic, disease sub-classification, prognostic and therapeutic information about a variety of diseases, including leukaemias. There are of the order of 30,000 protein-encoding genes in a human cell but because of alternative splicing, RNA editing, post-translational modifications and specific proteolysis the corresponding cell may contain >3 × 106 proteins. Therefore, as much as two orders of magnitude more information on a given cell is potentially available by proteomic analysis, over that provided by the analysis of gene expression. A proteomic study was carried out using two dimensional gel electrophoresis on CD133+ progenitor cell fractions from patients with various leukaemic disorders. Ten potential biomarkers were identified which included nuclear protein associated with mitotic apparatus (NuMA), heat shock proteins and redox regulators [56]. Many other proteomic techniques are beginning to be applied to the identification of cellular and serum biomarkers (reviewed in [44]). Such studies are in their infancy but have the potential to identify proteins and post-translationally modified forms of proteins associated with cancers which may include some novel targets for immunotherapy.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) analysis provides a rapid way in which regions of DNA within the genome with an abnormal gain or loss can be identified, enabling the detection of oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes, respectively, which are involved in the pathogenesis of a particular disease. Currently, the International Haplotype Mapping Project [30] and Perlegen Sciences [28] public databases contain more than two million verified SNP markers. A recent study which examined chromosomal copy number changes showed that 12 of the 64 AML patients with a normal karyotype had a uniparental disomy within chromosomes 9, 11, 13, 19 and 21 [63]. This may allow further sub-classification of this group of AML patients and has the potential to identify genes that are abnormally expressed in AML cells and as such have the potential to be targets for immunotherapy.

Cancer-testis (CT) antigens provide attractive targets for cancer specific immunotherapy due to their expression in immunologically protected sites such as the testes or placenta, and cancer cells (reviewed in [67]). Their absence or much lower levels of expression in normal cell counterparts, HSC in the case of CML, AML and MDS, reduce concerns regarding the induction of autoimmunity during therapy. Historically the identification of CT antigen gene expression in haematological malignancies has been limited [8, 9, 42, 81, 82]. However the expression of CT antigens such as HAGE, BAGE, PASD1 and RAGE-1 have more recently been found in less than or equal to 33% of all samples at presentation [1, 23, 25, 27]. In the absence of any frequently expressed leukaemia specific target then LAAs such as Wilm’s Tumour-1 (WT-1), preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma (PRAME) and proteinase 3 [17, 49, 55, 68] with an associated absence of or lower expression in normal counterpart cells are proving to be clinically promising alternatives in the more universal treatment of AML, CML and MDS.

DNA and peptide vaccines

The targeting of specific antigens in the myeloid leukaemias has predominantly involved the use of DNA or peptide vaccines. DNA vaccines have been shown to induce CD8+ T cells and B cell responses that can lyse tumours presenting the target antigen. They work by direct and cross-priming as their products are presented on both MHC class I and class II molecules. The benefits of DNA vaccines are that they are well tolerated, stable, can be repeatedly administered to the patient, they are easily manufactured on a large scale and are relatively cheap. The downsides are that the required toxicology experiments can negate some of the cheapness of manufacture, DNA vaccines can have low transfection efficiency, low injection dose:mass and poor immunogenicity. Some of these limitations can be circumvented with the use of adjuvants to overcome tolerance and the tumours’ immunosuppressive effects.

Peptide vaccines are also cost effective, easily manufactured under GMP, and can enter the clinic quite rapidly (less than 2 years). They have a good safety profile and have been shown to be well tolerated by over 5,000 patients worldwide. However there have been few dramatic effects with them in terms of tumour regressions, probably because peptides alone are poor immunogens. Again adjuvants (such as CpG adjuvants which use oligodeoxynucleotides with CpGs) can be used to provide danger signals. Single antigen vaccinations in mice have been shown to be less effective than multi-epitope vaccinations (reviewed in [58]) and multiple treatments, utilising different immunotherapeutic strategies, may be the most effective way to generate anti-tumour immune responses and target escape variants. Antigen based vaccines have the potential to simplify vaccine production, provide a source of more generally applicable vaccines and allow the user more control over the amount of administered antigen, which would then be hoped to have an associated improved efficacy.

Immunotherapy clinical trials targeting LAAs

Potential LAA targets for immunotherapy include

CD33, a cell surface glycoprotein which has expression largely restricted to the myeloid/monocytic lineage and is expressed on 80% of AML blasts but lacks expression on pluripotent stem cells. Bae et al. [3] identified an immunodominant heteroclitic epitope that is a promising candidate for use in future immunotherapy and Ab therapies (see next section) targeting this antigen.

Oncofetal antigen-immature laminin receptor (OFA-iLRP) is preferentially expressed on fetal tissues and in many types of cancer including haemopoietic malignancies. Siegel et al. [73] showed that OFA-iLRP presenting DCs could induce OFA-iLRP specific CTLs to lyse OFA-iLRP+ leukaemia cell lines and primary AML cells but not normal donor cells.

BCL-2 is overexpressed in many cancers and plays a pivotol role in preventing apoptotic cell death. This would mean that it’s down regulation by immune escape variants would only allow cells without a BCL-2 associated growth advantage to survive, making this an attractive target for immunotherapy. Andersen et al. [2] demonstrated spontaneous CTL-reactivity against BCL-2 in patients with AML and not normal healthy donors suggesting that the immune system can mount a response against BCL-2; and that vaccines to expand and direct this response may be effective against tumour cells which overexpress BCL-2.

Preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma (PRAME) was originally identified as an antigen in human melanoma due to its recognition by patient CTLs (reviewed in [49]). High expression of PRAME has been demonstrated in subsets of AML, and PRAME positive leukemia cell lines and patient samples have been shown to be susceptible to lysis by PRAME-specific CTLs.

The receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility (RHAMM), HLA-A2 restricted epitopes have been used to pre-sensitise CD8+ T cells from AML patients which then respond to peptide pulsed T2 cells [20]. In contrast, CD8+ T cells from similarly treated normal healthy donors, less frequently respond to the same peptide pulsed T2 cells, suggesting this may also make a promising candidate for future immunotherapy treatments. Similarly HLA-A2 restricted epitopes from the inhibitors of apoptosis gene family member, Survivin, have also been shown to induce tumour lysis, but not attack HLA-A2 negative tumour cells or normal haemopoietic progenitor cells [72].

LAA targets being used in immunotherapy clinical trials

Wilms’ tumour (WT-1) is overexpressed in most types of adult leukaemia including AML and has been shown to play a role in leukaemogenesis [17]. In murine models of AML, immunisation with MHC class I binding peptides induced WT-1 peptide specific CTLs that specifically lysed tumour cells. In humans 3 of 18 patients with AML were shown to have WT-1 specific antibodies in their sera while WT-1 and proteinase-3 specific CD8+ T cells have been shown to occur spontaneously in AML patients [68]. A phase I clinical trial has recently been described in which 14 AML and MDS patient were injected with a natural 9-mer WT-1 peptide or the modified form, which had previously shown to induce much stronger CTL activity [55]. Immunological responses were found in nine of the 13 evaluable leukaemia patients, and a clear correlation between clinical and immunological responses was found. Six out of 11 AML patients showed increased frequencies of WT-1 IFN-γ positive cells after vaccination. Recently Mailander et al. [45] described the induction of complete remission in a patient vaccinated with WT-1 peptide.

A single Proteinase 3 peptide epitope (called PR1) is being used in phase I/II clinical trials on AML, CML and MDS patients in combination with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant and GM-CSF [62]. To date 20 of 33 patients showed a measurable T cell immune responses using PR1/HLA-A2 tetramers and six of the patients had clinical responses with durable molecular remissions, follow-up periods being 1–4 years. The use of WT-1 and PR1 as targets for myeloid leukaemia immunotherapy are reviewed in detail elsewhere [77].

Measurement of immune responses in clinical trials

Assessments of the effectivity of immunotherapy clinical trials include the measurement of T cell responses by virtue of their proliferation, cytokine secretion and ability to kill specific targets. The proliferation of responding T cells can be measured by [3H-methyl]-thymidine incorporation in replicating DNA using mixed lymphocyte assays and by CFSE cellular dye loss with progressive cell cycles using flow cytometry. Secretion of cytokines such as IL-2, IL-4 and IFN-γ can indicate the stimulation of specific CD4+ subsets called TH0, TH1 and TH2 (Fig. 1). Cytokine secretion by responding T cells can be measured using biological assays in which cytokine dependent cell lines have their levels of [3H-methyl]-thymidine incorporation measured following incubation with T cell supernatants. In addition ELISAs, CBA beads or ELIspot assays can be used to measure T cell secretion. However, all these techniques are limited by sample size and only CTL assays measure the functionality of T cell responses. Conversely Granzyme B and IFN-γ ELIspots use relatively few cells but measure killing potential and indicate which T cells are present and responsive without indicating killing efficiency.

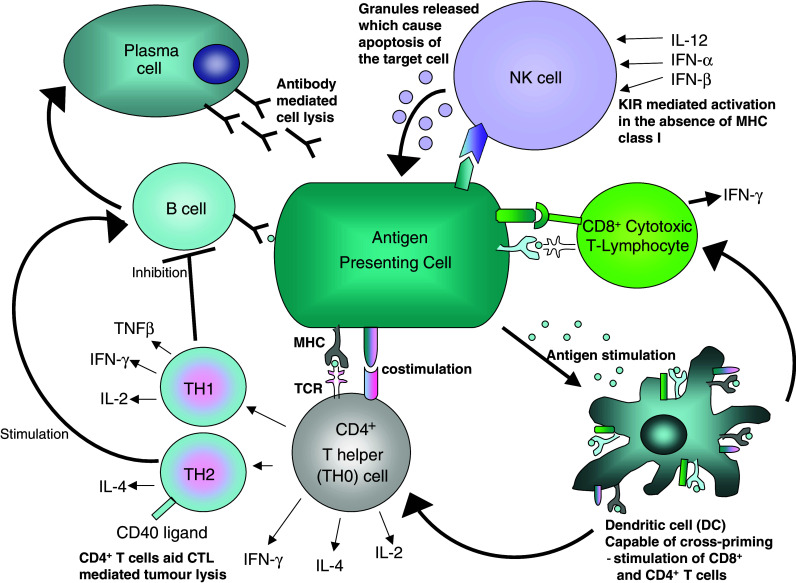

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatical representation of the cellular components of the immune system. Almost all cellular components of a normal immune response have been manipulated to enhance anti-tumour effects in immunotherapy. APCs such as tumour cells can be genetically manipulated to express elevated levels of MHC, antigen, costimulatory molcules and/or cytokines. These modified tumour cells can stimulate T cells (CTL and TH), B cells, DC and/or NK responses. Stimulated TH cells secrete cytokines which can further enhance CTL, TH, B-cell, DC and/or NK responses. Antigen presentation can be ‘upregulated’ through peptide vaccinations, in response to directly stimulated T cells or indirectly through the use of mature of DCs to present peptide to T cells. Administration of Abs can cause antibody mediated cell lysis and target cells which express the appropriate antigen. DCs can also be used in immunotherapy by their feeding with apoptotic tumour cells or by their pulsing with peptide or electroporation with tumour RNA. Adoptive therapy involves the replacement of these ‘primed’ mature DCs back into patients. DCs have also be fused with tumour cells to lead to the presentation of tumour antigens to T cells. NK cell lines, and stimulated T cells can also be used in adoptive therapy. In a normal immune response the type and extent of the immune response depends on ‘context’, the environment in which the immune response is primed and can be directed by how it is maintained

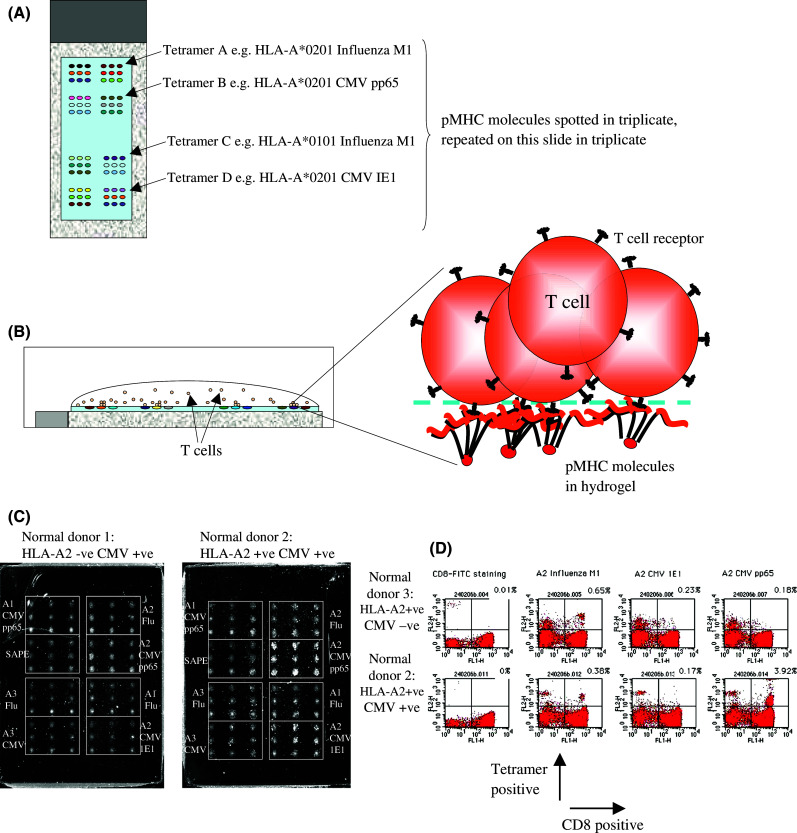

Peptide-MHC (pMHC) molecules, in which single MHC molecules bind specific peptides, can be tetramerised using biotin, and detected by virtue of streptavadin-FITC. Tetramers are then used to detect specific T cell populations (reviewed in [83]). This allows the quantitation of individual T cell populations by flow cytometry which can be purified using anti-PE by virtue of the bound tetramers and the T cell clones can be used for further analysis. Again cell numbers are often small and may require further expansion. Lipophilically dye-labeled T cells may also be incubated with pMHC arrays [12, 74] in which tetramers are spotted onto hydrogel slides and purified T cells incubated with a panel of pMHC molecules (Fig. 2). Bound T cells are observed by confocal microscopy. B-cell responses can be measured by virtue of secreted antibodies against known antigens in ELISA assays.

Fig. 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the peptide-MHC (pMHC) array method. Tetramers of pMHC molecules are a spotted onto hydrogel slides in triplicate at two sites. b Purified CD8+ T cells from patients or normal donors are incubated at 106 cells/ml for 20 mins at 37°C. c Unbound cells are washed off and visualized using a confocal microscope. All normal donor CD8+ T cells were isolated from peripheral blood. Normal donor 1 sample was found to be HLA-A2 negative and CMV sero-positive. This sample failed to bind any spots on the pMHC array at any notable level. In contrast Normal donor 2 sample was HLA-A2 positive had CMV pp65 and influenza M1 reactive T cells. d Normal donor 2 and 3 samples were stained with 1 μg pMHC per 105 cells. HLA-A2 positive, antigen positive T cells were identified using flow cytometry in the upper right quandrant of the dot plots, CD8+ cells were found in the upper and lower right hand quandrants of the dot plot. The sensitivity of flow cytometry and pMHC array were similar, although the pMHC array used tiny amounts of pMHC (1 ng/spot) and allowed the simultaneous identification of a number of specific T cell populations. However, pMHC arrays do not allow quantitation of the specific T cell population unlike flow cytometry

In vivo patient clinical responses are indicated by reduction of the tumour mass and/or decrease in the number and size of micrometasteses, objective clinical responses, and most importantly, but rarely seen in phase I and II clinical trials, increased survival times.

Future directions

An increasing number of LAAs have been identified which may be useful as targets for the immunotherapy of myeloid leukaemia. Despite advances in the field, HSC transplant remains one of the most promising treatments for AML patients under 60 years of age but has a high associated treatment-mortality rate (around 25%). However, targeted therapies (reviewed elsewhere [33, 38, 80]) and immunotherapy (reviewed here) offer promising options for patients in combination with conventional treatments to consolidate remission. The list of LAAs is rapidly growing primarily due to the early advent of techniques such as T cell cloning and more recently the SEREX technique. The large scale analysis of gene expression offered by microarray, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) and serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) and proteomic strategies such as 2-D gel electrophoresis have allowed the rapid expansion of our understanding of the leukaemic immunome. Microarray offers the opportunity to discover the pathway effects of treatment in responders compared with non-responders [54, 75, 79]. This would allow the prediction of response to treatment with the potential to influence personalized treatments in the future. In addition these LAAs can provide markers of disease stage [26], minimal residual disease state [29, 48] and can help predict survival [24].

Work by colleagues has shown the potential use of target antigens, through immunogenic epitope identification, ex vivo assays of T cells responses and Phase I/II clinical trials. There is an increasing interest in the use of modified peptides to enhance T cell responses against the inherently low immunogenicity of class I and II binding epitopes found in tumour associated antigens. To date, in the myeloid leukaemias these have included WT1 [60] and CD33 [3]. However, concerns about the ability of these modified peptides to induce immune response against wild type processed and presented LAAs will have to be addressed on a peptide by peptide basis.

The pMHC tetramer array [12, 74] offers the chance to investigate T cell populations in patients with disease course, conventional treatment and more interestingly with immunotherapy. This technique has the potential, through the follow-up of patients as they undergo treatments, to show the wax and wane of specific T cell populations. In addition it has the potential to allow clinicians to choose immunotherapy treatments based on existing and changing T cell populations.

There appears to be a huge potential for LAAs to be used in the treatment of diseases such as AML and an, as yet, unexplored use in the immunotherapy of MDS. Still no globally applicable LAA has been found for MDS and AML, and no singly successful immunotherapy treatment for myeloid leukaemia, perhaps due to the heterogeneic nature of MDS and AML and the efficacy of BCR-ABL targeted therapies in the early stages of CML. However, as immunotherapy continues to be evaluated for cancer it offers further insights into the pathogenesis of these diseases and improvements continue to follow, making these immunotherapeutic strategies more effective and more globally applicable to patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Nigel Westwood, Dr. Shahram Kordasti and Dr. Wendy Ingram for their critical review of the manuscript. B.G. is funded by the Leukaemia Research Fund.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- AML

acute myeloid leukaemia

- APC

antigen presenting cells

- APL

acute promyelocytic leukaemia

- ATRA

all trans-retinoic acid

- CML

chronic myeloid leukaemia

- CT

cancer-testis

- CTL

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

- DC

dendritic cell

- DLI

donor leukocyte infusion

- FLT3

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3

- GvL

graft versus leukaemia

- HSCT

haemopoietic stem cell transplant

- LAA

leukaemia associated antigen

- MDS

myelodysplastic syndrome

- NK

natural killer

- OFA-iLRP

Oncofetal antigen-immature laminin receptor

- pMHC

peptide-MHC

- PRAME

preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma

- RHAMM

receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility

- RIC

reduced intensity conditioning

- SEREX

serological analysis of recombinant cDNA expression libraries

- SNPs

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TCR

T cell receptor

- TRAIL

tumour necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- WT-1

Wilm’s Tumour-1

References

- 1.Adams SP, Sahota SS, Mijovic A, Czepulkowski B, Padua RA, Mufti GJ, Guinn BA. Frequent expression of HAGE in presentation chronic myeloid leukaemias. Leukemia. 2002;16:2238–2242. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen MH, Svane IM, Kvistborg P, Nielsen OJ, Balslev E, Reker S, Becker JC, Straten PT. Immunogenicity of Bcl-2 in patients with cancer. Blood. 2005;105:728–734. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bae J, Martinson JA, Klingemann HG. Heteroclitic CD33 peptide with enhanced anti-acute myeloid leukemic immunogenicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7043–7052. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bocchia M, Gentili S, Abruzzese E, Fanelli A, Iuliano F, Tabilio A, Amabile M, Forconi F, Gozzetti A, Raspadori D, Amadori S, Lauria F. Effect of a p210 multipeptide vaccine associated with imatinib or interferon in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia and persistent residual disease: a multicentre observational trial. Lancet. 2005;365:657–662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17945-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buggins AG, Milojkovic D, Arno MJ, Lea NC, Mufti GJ, Thomas NS, Hirst WJ. Microenvironment produced by acute myeloid leukemia cells prevents T cell activation and proliferation by inhibition of NF-kappaB, c-Myc, and pRb pathways. J Immunol. 2001;167:6021–6030. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullinger L, Valk PJ. Gene expression profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6296–6305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cathcart K, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Korontsvit T, Schwartz J, Zakhaleva V, Papadopoulos EB, Scheinberg DA. A multivalent bcr-abl fusion peptide vaccination trial in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2004;103:1037–1042. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambost H, Brasseur F, Coulie P, de Plaen E, Stoppa AM, Baume D, Mannoni P, Boon T, Maraninchi D, Olive D. A tumour-associated antigen expression in human haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 1993;84:524–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambost H, van Baren N, Brasseur F, Olive D. MAGE-A genes are not expressed in human leukemias. Leukemia. 2001;15:1769–1771. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan L, Hardwick N, Darling D, Galea-Lauri J, Gaken J, Devereux S, Kemeny M, Mufti G, Farzaneh F. IL-2/B7.1 (CD80) fusagene transduction of AML blasts by a self-inactivating lentiviral vector stimulates T cell responses in vitro: a strategy to generate whole cell vaccines for AML. Mol Ther. 2005;11:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan L, Hardwick NR, Guinn BA, Darling D, Gaken J, Galea-Lauri J, Ho AY, Mufti GJ, Farzaneh F. An immune edited tumour versus a tumour edited immune system: prospects for immune therapy of acute myeloid leukaemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1017–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0129-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen DS, Soen Y, Stuge TB, Lee PP, Weber JS, Brown PO, Davis MM. Marked differences in human melanoma antigen-specific T cell responsiveness after vaccination using a functional microarray. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen G, Zhang W, Cao X, Li F, Liu X, Yao L. Serological identification of immunogenic antigens in acute monocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2005;29:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheuk AT, Chan L, Czepulkowski B, Berger SA, Yagita H, Okumura K, Farzaneh F, Mufti GJ, Guinn BA. Development of a whole cell vaccine for acute myeloid leukaemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:68–75. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0674-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark RE, Dodi IA, Hill SC, Lill JR, Aubert G, Macintyre AR, Rojas J, Bourdon A, Bonner PL, Wang L, Christmas SE, Travers PJ, Creaser CS, Rees RC, Madrigal JA. Direct evidence that leukemic cells present HLA-associated immunogenic peptides derived from the BCR-ABL b3a2 fusion protein. Blood. 2001;98:2887–2893. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.10.2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis ID, Chen W, Jackson H, Parente P, Shackleton M, Hopkins W, Chen Q, Dimopoulos N, Luke T, Murphy R, Scott AM, Maraskovsky E, McArthur G, MacGregor D, Sturrock S, Tai TY, Green S, Cuthbertson A, Maher D, Miloradovic L, Mitchell SV, Ritter G, Jungbluth AA, Chen YT, Gnjatic S, Hoffman EW, Old LJ, Cebon JS. Recombinant NY-ESO-1 protein with ISCOMATRIX adjuvant induces broad integrated antibody and CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell responses in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10697–10702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403572101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaiger A, Reese V, Disis ML, Cheever MA. Immunity to WT1 in the animal model and in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2000;96:1480–1489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galea-Lauri J. Immunological weapons against acute myeloid leukaemia. Immunology. 2002;107:20–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gannage M, Abel M, Michallet AS, Delluc S, Lambert M, Giraudier S, Kratzer R, Niedermann G, Saveanu L, Guilhot F, Camoin L, Varet B, Buzyn A, Caillat-Zucman S. Ex vivo characterization of multiepitopic tumor-specific CD8 T cells in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: implications for vaccine development and adoptive cellular immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2005;174:8210–8218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greiner J, Li L, Ringhoffer M, Barth TF, Giannopoulos K, Guillaume P, Ritter G, Wiesneth M, Dohner H, Schmitt M. Identification and characterization of epitopes of the receptor for hyaluronic acid-mediated motility (RHAMM/CD168) recognized by CD8+ T cells of HLA-A2-positive patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106:938–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greiner J, Ringhoffer M, Simikopinko O, Szmaragowska A, Huebsch S, Maurer U, Bergmann L, Schmitt M. Simultaneous expression of different immunogenic antigens in acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:1413–1422. doi: 10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greiner J, Ringhoffer M, Taniguchi M, Hauser T, Schmitt A, Dohner H, Schmitt M. Characterization of several leukemia-associated antigens inducing humoral immune responses in acute and chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:224–231. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greiner J, Ringhoffer M, Taniguchi M, Li L, Schmitt A, Shiku H, Dohner H, Schmitt M. mRNA expression of leukemia-associated antigens in patients with acute myeloid leukemia for the development of specific immunotherapies. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:704–711. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greiner J, Schmitt M, Li L, Giannopoulos K, Bosch K, Schmitt A, Dohner K, Schlenk RF, Pollack JR, Dohner H, Bullinger L (2006) Expression of tumor-associated antigens in acute myeloid leukemia: implications for specific immunotherapeutic approaches. Blood. DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-01-023127 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Guinn BA, Bland EA, Lodi U, Liggins AP, Tobal K, Petters S, Wells JW, Banham AH, Mufti GJ. Humoral detection of leukaemia-associated antigens in presentation acute myeloid leukaemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guinn BA, Gilkes AF, Mufti GJ, Burnett AK, Mills KI. The tumour antigens RAGE-1 and MGEA6 are expressed more frequently in the less lineage restricted subgroups of presentation acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:238–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guinn BA, Gilkes AF, Woodward E, Westwood NB, Mufti GJ, Linch D, Burnett AK, Mills KI. Microarray analysis of tumour antigen expression in presentation acute myeloid leukaemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:703–713. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinds DA, Stuve LL, Nilsen GB, Halperin E, Eskin E, Ballinger DG, Frazer KA, Cox DR. Whole-genome patterns of common DNA variation in three human populations. Science. 2005;307:1072–1079. doi: 10.1126/science.1105436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inoue K, Sugiyama H, Ogawa H, Nakagawa M, Yamagami T, Miwa H, Kita K, Hiraoka A, Masaoka T, Nasu K. WT1 as a new prognostic factor and a new marker for the detection of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia. Blood. 1994;84:3071–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The International HapMap Project Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jager D, Taverna C, Zippelius A, Knuth A. Identification of tumor antigens as potential target antigens for immunotherapy by serological expression cloning. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:144–147. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jager E, Nagata Y, Gnjatic S, Wada H, Stockert E, Karbach J, Dunbar PR, Lee SY, Jungbluth A, Jager D, Arand M, Ritter G, Cerundolo V, Dupont B, Chen YT, Old LJ, Knuth A. Monitoring CD8 T cell responses to NY-ESO-1: correlation of humoral and cellular immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.John AM, Thomas NS, Mufti GJ, Padua RA. Targeted therapies in myeloid leukemia. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:41–62. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaufmann SH, Steensma DP. On the TRAIL of a new therapy for leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:2195–2202. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knights AJ, Weinzierl AO, Flad T, Guinn BA, Mueller L, Mufti GJ, Stevanovic S, Pawelec G. A novel MHC-associated proteinase 3 peptide isolated from primary chronic myeloid leukaemia cells further supports the significance of this antigen for the immunotherapy of myeloid leukaemias. Leukemia. 2006;20:1067–1072. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolb HJ, Rank A, Chen X, Woiciechowsky A, Roskrow M, Schmid C, Tischer J, Ledderose G. In-vivo generation of leukaemia-derived dendritic cells. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2004;17:439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koya RC, Kasahara N, Pullarkat V, Levine AM, Stripecke R. Transduction of acute myeloid leukemia cells with third generation self-inactivating lentiviral vectors expressing CD80 and GM-CSF: effects on proliferation, differentiation, and stimulation of allogeneic and autologous anti-leukemia immune responses. Leukemia. 2002;16:1645–1654. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krause DS, Van Etten RA. Tyrosine kinases as targets for cancer therapy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:172–187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra044389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kufner S, Fleischer RP, Kroell T, Schmid C, Zitzelsberger H, Salih H, de Valle F, Treder W, Schmetzer HM. Serum-free generation and quantification of functionally active Leukemia-derived DC is possible from malignant blasts in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:953–970. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0657-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L, Reinhardt P, Schmitt A, Barth TF, Greiner J, Ringhoffer M, Dohner H, Wiesneth M, Schmitt M. Dendritic cells generated from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) blasts maintain the expression of immunogenic leukemia associated antigens. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:685–693. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0631-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Li H, Wang MN, Lu D, Bassi R, Wu Y, Zhang H, Balderes P, Ludwig DL, Pytowski B, Kussie P, Piloto O, Small D, Bohlen P, Witte L, Zhu Z, Hicklin DJ. Suppression of leukemia expressing wild-type or ITD-mutant FLT3 receptor by a fully human anti-FLT3 neutralizing antibody. Blood. 2004;104:1137–1144. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim SH, Austin S, Owen-Jones E, Robinson L. Expression of testicular genes in haematological malignancies. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:1162–1164. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1051–1062. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909303411407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ludwig JA, Weinstein JN. Biomarkers in cancer staging, prognosis and treatment selection. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:845–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mailander V, Scheibenbogen C, Thiel E, Letsch A, Blau IW, Keilholz U. Complete remission in a patient with recurrent acute myeloid leukemia induced by vaccination with WT1 peptide in the absence of hematological or renal toxicity. Leukemia. 2004;18:165–166. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marijt WA, Heemskerk MH, Kloosterboer FM, Goulmy E, Kester MG, van der Hoorn MA, van Luxemburg-Heys SA, Hoogeboom M, Mutis T, Drijfhout JW, van Rood JJ, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Hematopoiesis-restricted minor histocompatibility antigens HA-1- or HA-2-specific T cells can induce complete remissions of relapsed leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2742–2747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530192100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathews V, DiPersio JF. Stem cell transplantation in acute myelogenous leukemia in first remission: what are the options? Curr Hematol Rep. 2004;3:235–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsushita M, Ikeda H, Kizaki M, Okamoto S, Ogasawara M, Ikeda Y, Kawakami Y. Quantitative monitoring of the PRAME gene for the detection of minimal residual disease in leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;112:916–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsushita M, Yamazaki R, Ikeda H, Kawakami Y. Preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma (PRAME) in the development of diagnostic and therapeutic methods for hematological malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:439–444. doi: 10.1080/1042819021000035725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meletis J, Viniou N, Terpos E. Novel agents for the management of myelodysplastic syndromes. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12:RA194–RA206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morris E, Hart D, Gao L, Tsallios A, Xue SA, Stauss H. Generation of tumor-specific T-cell therapies. Blood Rev. 2006;20:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mulford DA, Jurcic JG. Antibody-based treatment of acute myeloid leukaemia. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:95–105. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohno R, Nakamura Y. Prediction of response to imatinib by cDNA microarray analysis. Semin Hematol. 2003;40:42–49. doi: 10.1053/shem.2003.50041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oka Y, Tsuboi A, Taguchi T, Osaki T, Kyo T, Nakajima H, Elisseeva OA, Oji Y, Kawakami M, Ikegame K, Hosen N, Yoshihara S, Wu F, Fujiki F, Murakami M, Masuda T, Nishida S, Shirakata T, Nakatsuka S, Sasaki A, Udaka K, Dohy H, Aozasa K, Noguchi S, Kawase I, Sugiyama H. Induction of WT1 (Wilms’ tumor gene)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by WT1 peptide vaccine and the resultant cancer regression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13885–13890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405884101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ota J, Yamashita Y, Okawa K, Kisanuki H, Fujiwara S, Ishikawa M, Lim Choi Y, Ueno S, Ohki R, Koinuma K, Wada T, Compton D, Kadoya T, Mano H. Proteomic analysis of hematopoietic stem cell-like fractions in leukemic disorders. Oncogene. 2003;22:5720–5728. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Padua RA, Larghero J, Robin M, le Pogam C, Schlageter MH, Muszlak S, Fric J, West R, Rousselot P, Phan TH, Mudde L, Teisserenc H, Carpentier AF, Kogan S, Degos L, Pla M, Bishop JM, Stevenson F, Charron D, Chomienne C. PML-RARA-targeted DNA vaccine induces protective immunity in a mouse model of leukemia. Nat Med. 2003;9:1413–1417. doi: 10.1038/nm949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmowski MJ, Choi EM, Hermans IF, Gilbert SC, Chen JL, Gileadi U, Salio M, Van Pel A, Man S, Bonin E, Liljestrom P, Dunbar PR, Cerundolo V. Competition between CTL narrows the immune response induced by prime-boost vaccination protocols. J Immunol. 2002;168:4391–4398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinilla-Ibarz J, Cathcart K, Korontsvit T, Soignet S, Bocchia M, Caggiano J, Lai L, Jimenez J, Kolitz J, Scheinberg DA. Vaccination of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia with bcr-abl oncogene breakpoint fusion peptides generates specific immune responses. Blood. 2000;95:1781–1787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinilla-Ibarz J, May RJ, Korontsvit T, Gomez M, Kappel B, Zakhaleva V, Zhang RH, Scheinberg DA. Improved human T-cell responses against synthetic HLA-0201 analog peptides derived from the WT1 oncoprotein. Leukemia. 2006;20:2025–2033. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Porter DL, Antin JH. Donor leukocyte infusions in myeloid malignancies: new strategies. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2006;19:737–755. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qazilbash MH, Wieder E, Rios R, Sijie L, Kant S, Giralt S, Estey EH, Thall P, de Lima M, Couriel D, et al. Vaccination wth the PR1 leukaemia-associated antigen can induce complete remission in patients with myeloid leukaemia. Blood. 2004;104:259. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raghavan M, Lillington DM, Skoulakis S, Debernardi S, Chaplin T, Foot NJ, Lister TA, Young BD. Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism analysis reveals frequent partial uniparental disomy due to somatic recombination in acute myeloid leukemias. Cancer Res. 2005;65:375–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reichardt VL, Brossart P. Current status of vaccination therapy for leukemias. Curr Hematol Rep. 2005;4:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robin M, Schlageter MH, Chomienne C, Padua RA. Targeted immunotherapy in acute myeloblastic leukemia: from animals to humans. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:933–943. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0678-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sahin U, Tureci O, Schmitt H, Cochlovius B, Johannes T, Schmits R, Stenner F, Luo G, Schobert I, Pfreundschuh M. Human neoplasms elicit multiple specific immune responses in the autologous host. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11810–11813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scanlan MJ, Simpson AJ, Old LJ. The cancer/testis genes: review, standardization, and commentary. Cancer Immun. 2004;4:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scheibenbogen C, Letsch A, Thiel E, Schmittel A, Mailaender V, Baerwolf S, Nagorsen D, Keilholz U. CD8 T-cell responses to Wilms tumor gene product WT1 and proteinase 3 in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:2132–2137. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schirrmann T, Pecher G. Specific targeting of CD33(+) leukemia cells by a natural killer cell line modified with a chimeric receptor. Leuk Res. 2005;29:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scott BL, Deeg HJ. Hemopoietic cell transplantation for the myelodysplastic syndromes. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2005;53:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Siegel S, Steinmann J, Schmitz N, Stuhlmann R, Dreger P, Zeis M. Identification of a survivin-derived peptide that induces HLA-A*0201-restricted antileukemia cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Leukemia. 2004;18:2046–2047. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Siegel S, Wagner A, Kabelitz D, Marget M, Coggin J, Jr, Barsoum A, Rohrer J, Schmitz N, Zeis M. Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses against the oncofetal antigen-immature laminin receptor for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2003;102:4416–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soen Y, Chen DS, Kraft DL, Davis MM, Brown PO. Detection and characterization of cellular immune responses using peptide-MHC microarrays. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E65. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tagliafico E, Tenedini E, Manfredini R, Grande A, Ferrari F, Roncaglia E, Bicciato S, Zini R, Salati S, Bianchi E, Gemelli C, Montanari M, Vignudelli T, Zanocco-Marani T, Parenti S, Paolucci P, Martinelli G, Piccaluga PP, Baccarani M, Specchia G, Torelli U, Ferrari S. Identification of a molecular signature predictive of sensitivity to differentiation induction in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2006;20:1751–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsuji T, Yasukawa M, Matsuzaki J, Ohkuri T, Chamoto K, Wakita D, Azuma T, Niiya H, Miyoshi H, Kuzushima K, Oka Y, Sugiyama H, Ikeda H, Nishimura T. Generation of tumor-specific, HLA class I-restricted human Th1 and Tc1 cells by cell engineering with tumor peptide-specific T-cell receptor genes. Blood. 2005;106:470–476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Van Driessche A, Gao L, Stauss HJ, Ponsaerts P, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN, Van Tendeloo VF. Antigen-specific cellular immunotherapy of leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1863–1871. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100:2292–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Villuendas R, Steegmann JL, Pollan M, Tracey L, Granda A, Fernandez-Ruiz E, Casado LF, Martinez J, Martinez P, Lombardia L, Villalon L, Odriozola J, Piris MA. Identification of genes involved in imatinib resistance in CML: a gene-expression profiling approach. Leukemia. 2006;20:1047–1054. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Walz C, Sattler M. Novel targeted therapies to overcome imatinib mesylate resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;57:145–164. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Liu H, Salati E, Chiriva-Internati M, Lim SH. Gene expression and immunologic consequence of SPAN-Xb in myeloma and other hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2003;101:955–960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Mandal A, Zhang J, Giles FJ, Herr JC, Lim SH. The spermatozoa protein, SLLP1, is a novel cancer-testis antigen in hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6544–6550. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Whiteside TL, Gooding W. Immune monitoring of human gene therapy trials: potential application to leukemia and lymphoma. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003;31:63–71. doi: 10.1016/S1079-9796(03)00064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xue SA, Gao L, Hart D, Gillmore R, Qasim W, Thrasher A, Apperley J, Engels B, Uckert W, Morris E, Stauss H. Elimination of human leukemia cells in NOD/SCID mice by WT1-TCR gene-transduced human T cells. Blood. 2005;106:3062–3067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]