Abstract

Production of phytocannabinoids remains an area of active scientific interest due to growing use of cannabis by the public and the underexplored therapeutic potential of the over 100 minor cannabinoids. While phytocannabinoids are biosynthesized by Cannabis sativa and other select plants and fungi, structural analogs and stereoisomers can only be accessed synthetically or through heterologous expression. To date, the bioproduction of cannabinoids has required eukaryotic hosts like yeast since key, native oxidative cyclization enzymes do not express well in bacterial hosts. Here, we report that two marine bacterial flavoenzymes, Clz9 and Tcz9, perform oxidative cyclization reactions on phytocannabinoid precursors to efficiently generate cannabichromene scaffolds. Furthermore, Clz9 and Tcz9 express robustly in bacteria and display significant tolerance to organic solvent and high substrate loading, thereby enabling fermentative production of cannabichromenic acid in Escherichia coli and indicating their potential for biocatalyst development.

Keywords: berberine-bridge enzyme, biocatalysis, biotransformation, cannabinoids, natural products

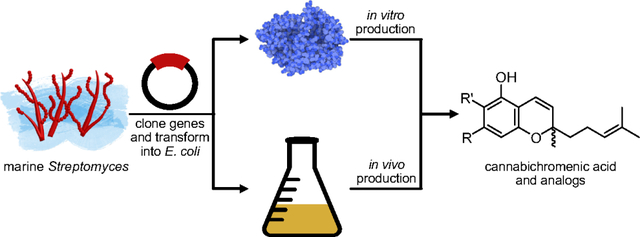

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

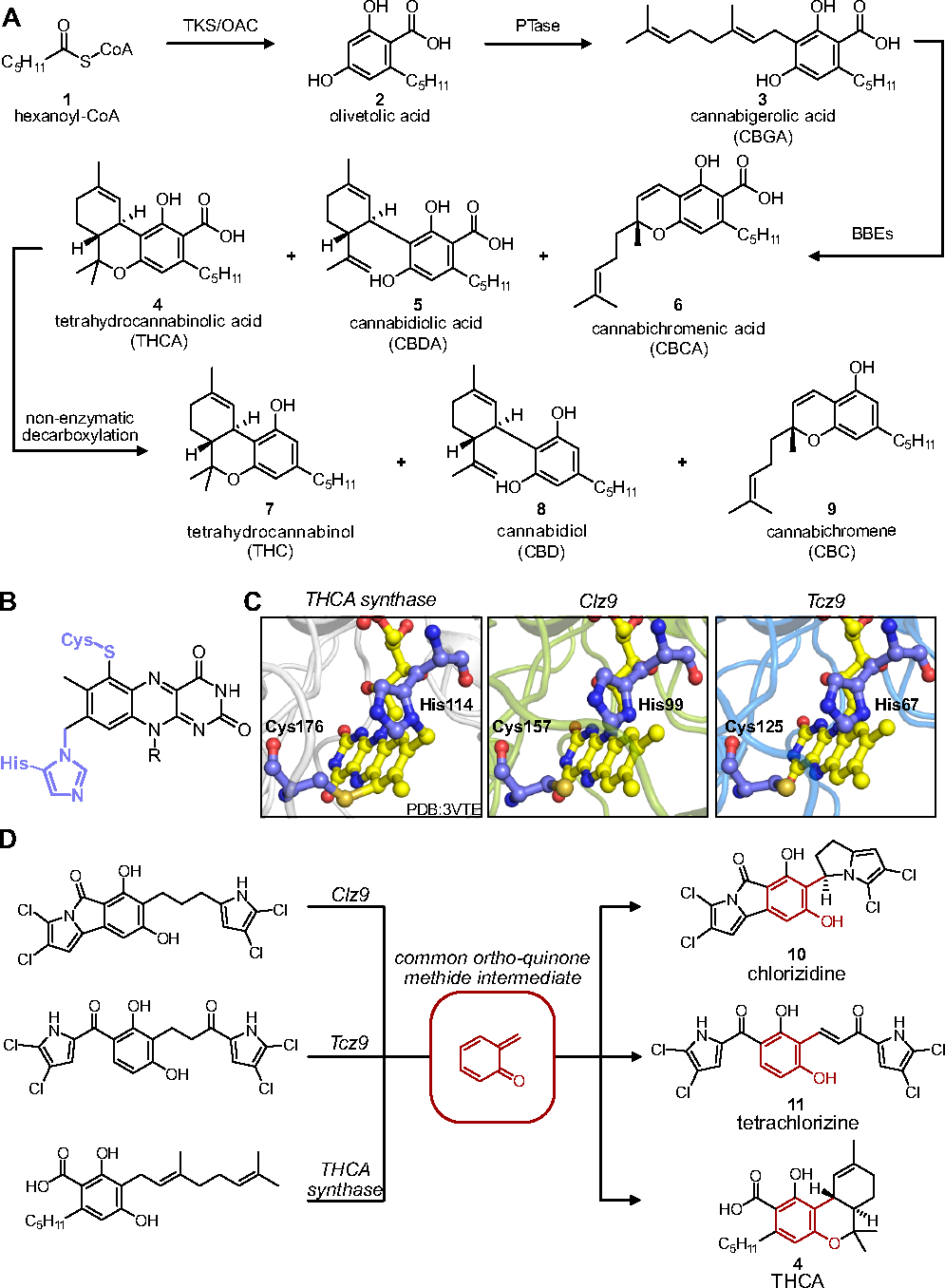

Humans have used Cannabis sativa therapeutically for centuries in large part because it produces hundreds of natural products like flavonoids, terpenes, and phytocannabinoids.1–5 Of these, phytocannabinoids have in particular garnered scientific interest for decades, leading to discovery of the endocannabinoid system and FDA-approved treatments for nausea, pain management, and some rare juvenile forms of epilepsy.6–11 Phytocannabinoids from C. sativa are biosynthesized from fatty acid oxidation byproducts (hexanoyl-CoA, 1) that are stitched together and cyclized to form resorcinol intermediates like olivetolic acid (2).12 Prenylation to cannabigerolic acid (CBGA, 3) followed by oxidative cyclization produce the iconic cannabinoids initially in their carboxylated forms, namely tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA, 4), cannabidiolic acid (CBDA, 5), and cannabichromenic acid (CBCA, 6) (Figure 1A). The bulk of scientific research in the phytocannabinoid field has focused on the decarboxylated forms of two cyclization isomers, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, 7) and cannabidiol (CBD, 8), due to their broad therapeutic properties.13 Minor cannabinoids, such as cannabichromene (CBC, 9), remain less well studied despite preliminary reports on intriguing bioactivity.14–15 The structure-activity relationship (SAR) of CBC and other minor cannabinoids is even less well understood, with only a few reports on substituents that modulate activity.16–17 Thus, the development of new, unified methods for generating CBC and related analogs would provide material for more rigorous biological evaluation.

Figure 1.

(A) Phytocannabinoid biosynthesis. TKS = tetraketide synthase, OAC = olivetolic acid cyclase, PTase = prenyltransferases, BBEs = BBE-like enzyme family synthases (B) Bicovalent flavin cofactor attachment. (C) Key conserved residues between phytocannabinoid producing and recently identified bacterial BBE-like enzymes. (D) Common ortho-quinone methide intermediate produced en route to product formation.

Current routes to access material include isolation from native producers, chemical synthesis, and heterologous production in non-native hosts. Chemical isolation can be laborious, especially for minor cannabinoids which are produced in low quantities, and only furnishes native chemical species, precluding access to designer analogs for SAR testing. Chemical synthesis can provide access to both minor cannabinoids and analogs, though stereocontrol requires expensive iridium catalysts or enantiopure starting materials (e.g. R-(+)-limonene-derived p-menthadienol), and sometimes high step counts.18–19 Stereoselective production can also be achieved using enzymes to catalyze cyclization. Plant enzymes that produce THCA (4) and relevant analogs have been expressed in yeast to recombinantly produce cannabinoids, albeit at low titers of ~8 mg THCA per liter produced after strain optimization.20–23 A major bottleneck for production has been the low catalytic activity and poor expression of the C. sativa oxidative cyclization enzymes, even in yeast. These problematic enzymes belong to the Berberine-bridge type enzymes (BBE-like enzyme) family, characterized structurally by their vanillyl alcohol-oxidase (VAO) beta-sheet fold, and bi-covalent attachment to the flavin cofactor by conserved cysteine and histidine residues (Figure 1B).24–27

We recently identified two new BBE-like enzymes from marine bacteria that express functionally in Escherichia coli with high catalytic activity (Figure 1C).28–29 Importantly, these two flavoproteins, Clz9 and Tcz9, are thought to produce similar ortho-quinone methide intermediates en route to product formation (namely chlorizidine (10) and tetrachlorizine (11), respectively) as the native cannabinoid cyclization enzymes, like THCA synthase (Figure 1D).30 Here, we report the ability of bacterial BBE-like enzymes to perform phytocannabinoid-forming cyclization reactions, providing biocatalytic access to cannabichromene scaffolds.

Results and Discussion

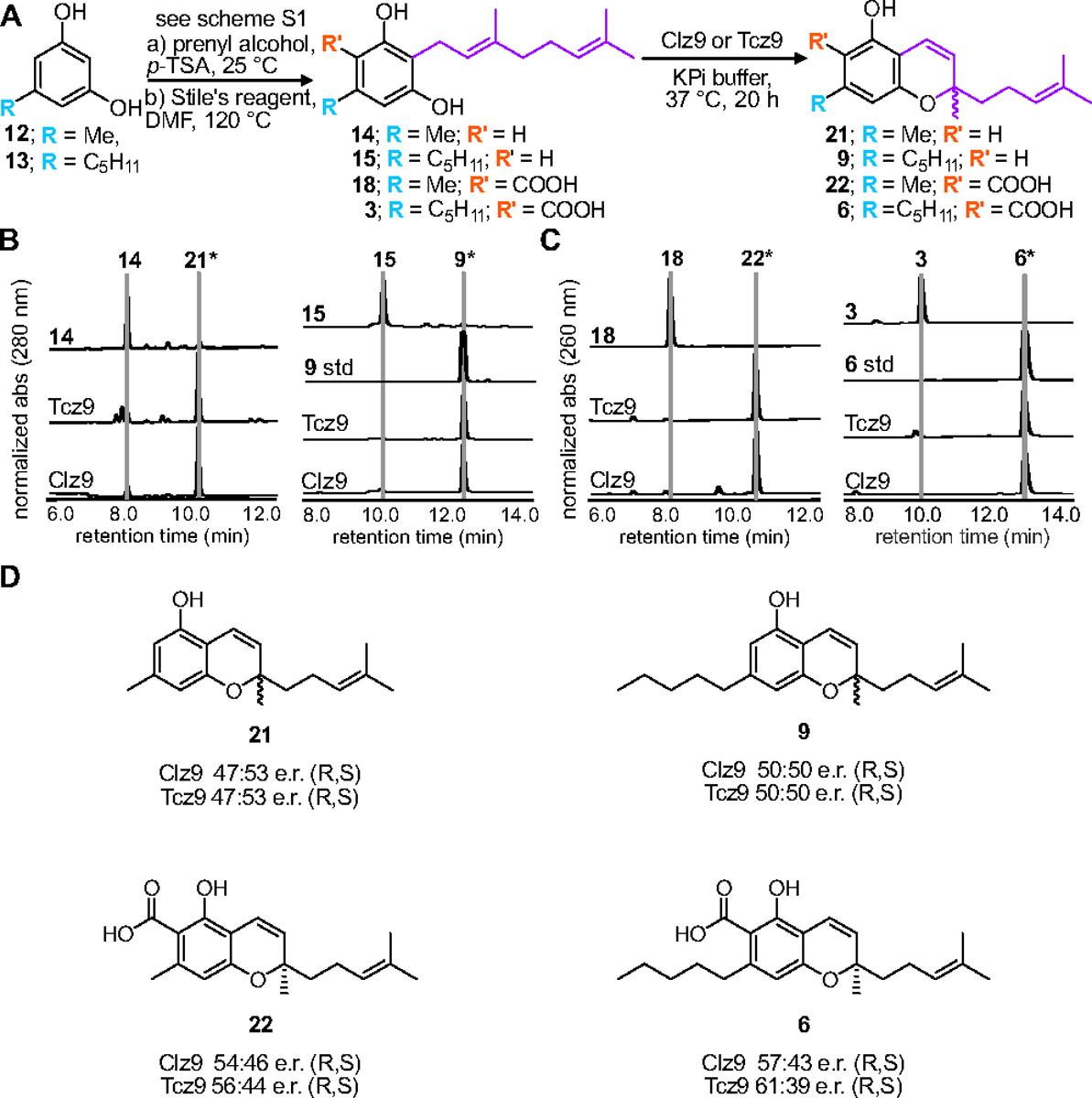

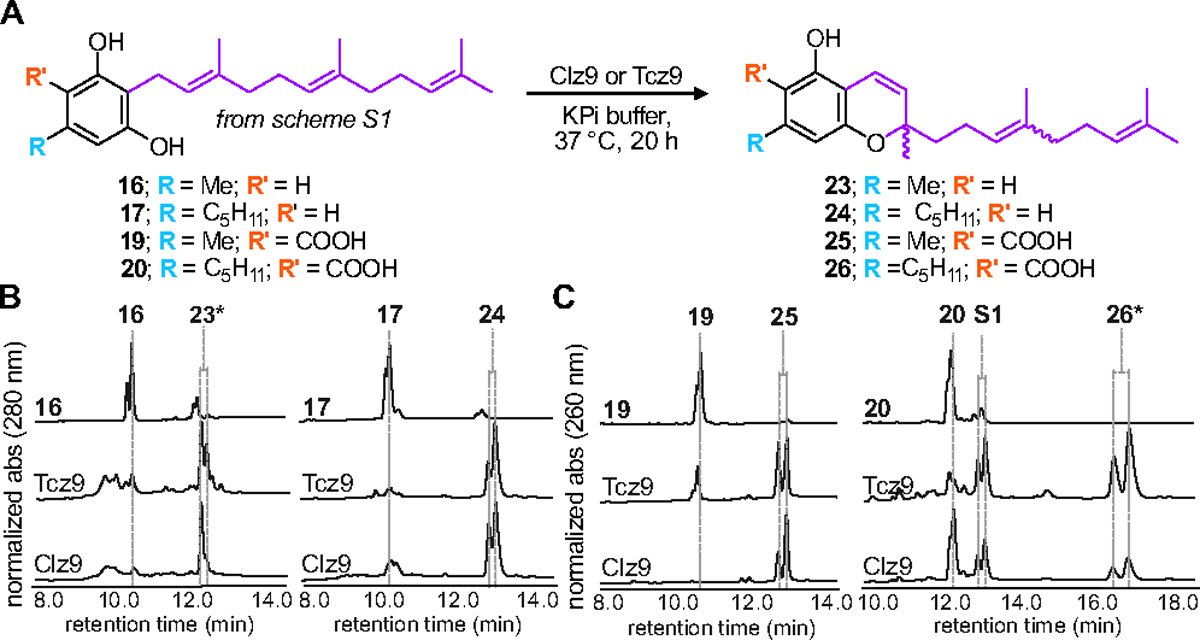

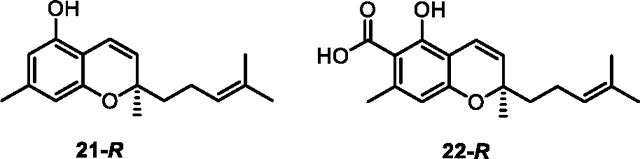

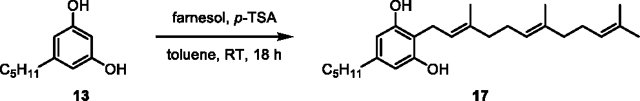

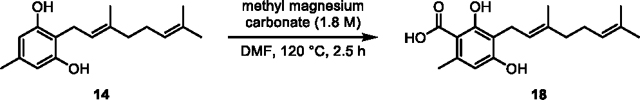

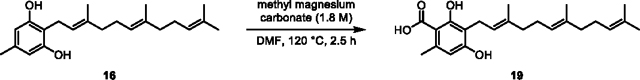

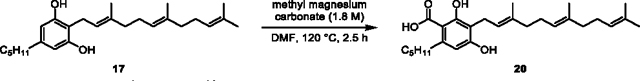

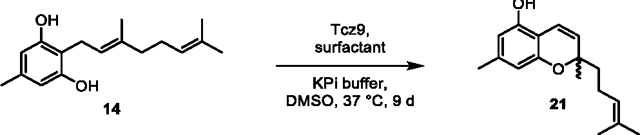

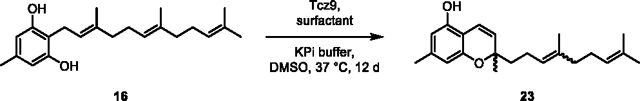

First, we sought to determine the activity of recombinant Clz9 and Tcz9 when assayed against a panel of synthetic resorcinol precursors based on plant cannabinoid substrates. The C-5 alkyl position of olivetol (13) has been previously identified as a position that modulates bioactivity.16, 31–34 We thus prenylated commercially available 5-methyl and 5-pentyl resorcinols 12 (ornicol) and 13, respectively, via EAS chemistry using catalytic acid and prenyl alcohols to afford a series of compounds with either geranyl or farnesyl isoprene chains at the C-2 position (14–17).35 These products were then carboxylated with methyl magnesium carbonate to produce compounds 3, 18–20 (Scheme S1).12 As the native substrate in C. sativa, CBGA (3), contains a geranyl side chain, we first tested the enzymatic activity with both acid (3 and 18) and non-acid (14 and 15) geranyl side-chain precursors (Figure 2A–C, Figures S1–S4). We observed that both bacterial enzymes were able to cyclize all combinations of alkyl side chain and presence/absence of the carboxylic acid unit as observed by LC-MS measurements and NMR confirmation of purified products. While the bioconversation of CBGA (3) to CBCA (6) has been observed in plants, non-enzymatic decarboxylation is then required to yield the non-acid products (i.e. THC 7 vs THCA 4).36 In contrast, Clz9 and Tcz9 directly produced the decarboxylated chromene scaffolds from corresponding non-acid substrates, a reaction that has not yet been observed with a plant enzyme. When compared to an analytical standard of CBC (9), we found that CBG (15) was fully converted to CBC. Importantly, non-acid products typically display different biological activity from acid-containing products, underscoring the importance for direct access to these materials.37–38 Clz9 and Tcz9 also efficiently processed the C-5-methyl-containing 14 and 15 to the natural products cannabiorcichromenic acid (22) and corresponding non-acid form (21) found naturally in the plant Rhododrendon anthopogonoides and the fungus Cylindrocarpon olidum (Figure 2B).39–40 The tolerance of Clz9 and Tcz9 to varying alkyl chain length and presence or absence of the carboxylate suggests inherent promiscuity and underscores potential for generation of structurally diverse cannabichromene product libraries.

Figure 2.

Clz9 and Tcz9 generate cannabichromene products. (A) Scheme for conversion of geranyl side chain substrates to products. Reaction conditions: a) geraniol or farnesol (1.8 equivs), p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA, 0.05 equivs), toluene or chloroform, 25 °C, 18 h. b) methyl magnesium carbonate (1.8 M solution, 10 equivs), DMF, 120 °C, 2.5 h. (B) LC-MS traces showing absorbance at 280 nm for products produced from non-acid substrates 14 and 15. (C) LC-MS traces showing absorbance at 260 nm for product produced from acid-bearing substrates 3 and 18. *Indicates full NMR characterization. (D) Clz9 and Tcz9 have limited stereoselectivity. Enantiomeric ratios were determined by peak height from analytical scale reactions analyzed with chiral chromatography. Absolute configuration was determined with CD spectroscopy.

We then explored whether other members of the BBE-like enzyme family with soluble expression in E. coli could have latent cannabinoid cyclase activity. Though only 159 members of the 38,636 enzymes within the BBE-like enzyme family (PFAM 08031) have been biochemically validated, a handful catalyze oxidative cyclization reactions like those observed in native cannabinoid synthases.25 We employed a bioinformatics-guided methodology to identify candidate enzymes using a Sequence Similarity Network (SSN, Figure S5). The application of SSNs has proven effective in identifying functional analogs within other oxidative enzymes like P450s41 and flavin-dependent halogenases42–43 in addition to other enzyme families.44–45 Using BBE-like enzymes known to mediate oxidative cyclization of 3 (THCA synthase, CBDA synthase, CBCA synthase, Clz9 and Tcz9), we curated a list of homologous proteins based on percent identity and conserved active site residues (Figure S6).12 For a more comprehensive investigation of oxidative cyclization activity within the family, the enterocin favorskiiase BBE-like flavoprotein EncM46 and a homolog of it were also included. Further selection refinements were made using the predicted solubility in E. coli with the Lorschmidt Laboratories SoluProt v1.047 webtool. In tandem, we used the automated Lorschmidt Laboratories EnzymeMiner v1.048 webtool to mine BBE-like sequences for other homologs with potential activity. The sequence for THCA synthase was input along with the identity of key residues crucial for THCA synthase activity to refine the search parameters (Figure S6A). In total, 18 proteins were selected for biochemical evaluation with CBGA (3) as a substrate.

Of the 18 enzymes tested, only one showed any kind of cyclization activity with 3 in bacterial lysate assays (Figure S7). This member, YgaK, was most similar to Clz9 and Tcz9, with a sequence similarity of 58% (to Clz9) and 57% (to Tcz9). YgaK is found in the bacterium Phytohabitans suffuscus in a similarly organized biosynthetic gene cluster to chloridizine A and tetrachlorizine. While the native substrate for this enzyme has not yet been established, the phytocannabinoid product produced by YgaK was cannabichromene. We further expressed and purified the 18 enzymes to test activity with 3 in in vitro enzyme assays. YgaK showed comparable activity to Clz9 and Tcz9, though protein yields were lower than those obtained from Clz9 and Tcz9. We further found that several other enzymes had low activity not detected in lysate assays, including EncM and a more distant homolog of Clz9 and Tcz9. The rest of the enzymes had no activity with 3 (Figure S8). Further studies expanding the search area, and a more comprehensive understanding of the specific active site residue contributions to cannabinoid cyclization will likely be necessary to discover more BBE’s with latent cannabinoid cyclase activity. Therefore, we moved forward with further characterization of only Clz9 and Tcz9.

To determine the biocatalytic potential of Clz9 and Tcz9, we studied their tolerance to DMSO and substrate loading. Tcz9 was found to be remarkably stable in DMSO, capable of >50% conversion even in the presence of 40% DMSO, while Clz9 activity dropped by about half in as little as 20% DMSO (Figure S9). Because resorcinol substrates are highly insoluble in aqueous solutions, especially non-acid substrates such as 14 and 15, the tolerance to DMSO is significant for biocatalytic production of cannabinoids. We also observed that both enzymes were moderately tolerant to high substrate loading, observing conversion even at 0.1 mole percent enzyme. Because Tcz9 displayed higher tolerance to both DMSO and substrate concentration, we employed it to generate larger quantities of 6, 9, and 21–22 for isolation and characterization. After 7 d, or at >90% conversion to product, reactions were acidified to pH 2, extracted with ethyl acetate, and residue purified by chromatography. Products were purified with normal phase flash chromatography, and structurally characterized by NMR. As we suspected, all products were CBC and CBCA analogs, and enzymatically produced CBC and CBCA had spectral data matching that already reported in the literature.

Native CBCA synthase has modest stereoselectivity for the R enantiomer of CBCA, producing a scalemic mixture that differs depending on Cannabis strain.49 We tested selectivity of Clz9 and Tcz9 using chiral chromatography, and found they had low to no e.r., but that e.r. differed depending on substrate (Figure 2D, Figure S10). While the e.r. of both 21 and 9 were nearly 1:1, a slight preference for the R enantiomer emerged with the presence of the carboxylic acid. This suggests that the carboxylated substrates may bind differently, or more effectively to the active site than the non-acid substrates. This hypothesis is supported by the corresponding pentyl side-chain substrates. When enzymes were incubated with 15, the mixture produced was racemic.. However, when incubated with 3, Tcz9 displayed an e.r. of 1.6:1 while Clz9 had an e.r. of 1.3:1. We further purified enantiomers to definitively assign their stereochemistry via comparison of experimental CD spectra to ECD calculations (Figure S11). While Clz9 and Tcz9 do not exhibit high stereoselectivity, with selectivity lower than what is typically observed from the plant CBCA synthase, the native substrates for Clz9 and Tcz9 are structurally diverse from cannabinoid precursors. Enzyme engineering and computationally assisted repacking of the active site to enforce stereoselectivity more stringently are the next steps to improve desirable activity.

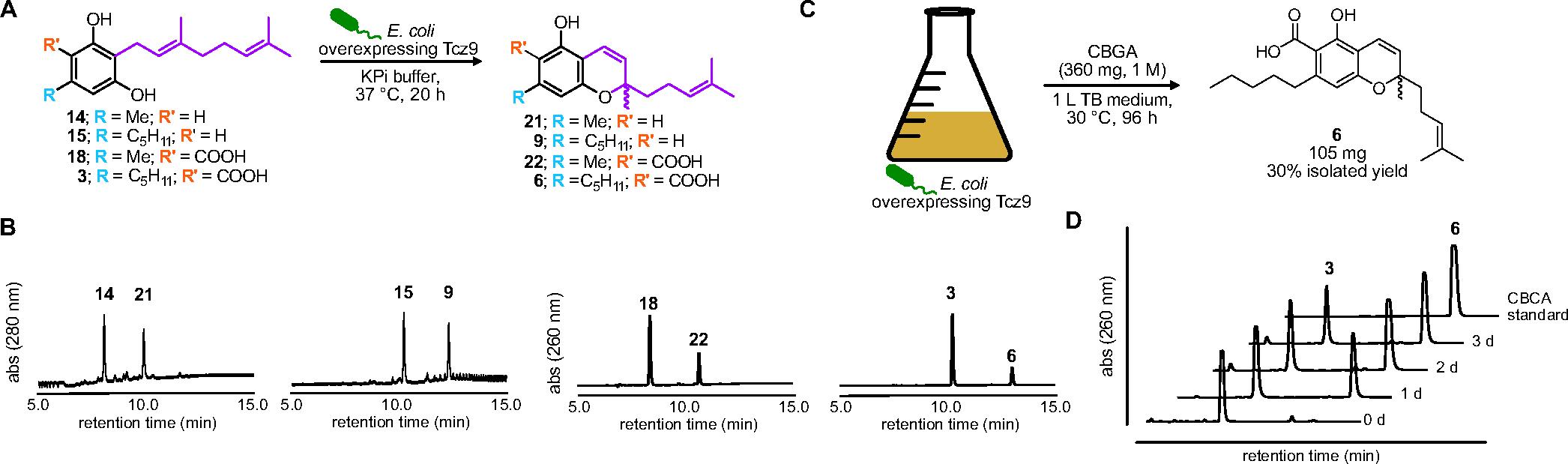

We next investigated whether Tcz9 could be used for fermentative production of cannabinoids in Escherichia coli, a feat that has not yet been accomplished. Synthetic precursors were fed to bacteria overexpressing Tcz9 and were converted to the same products as we earlier measured with purified enzyme on analytical scale (Figure 3). At larger scale (1 mol/L), CBCA (6) was purified from E. coli overexpressing Tcz9 with a final isolated yield of 30% along with the re-isolation of substrate CBGA (3) at 26% recovery. This initial demonstration for cannabinoid production with wild type enzymes in bacteria sets the stage for fermentative production in conjunction with upstream enzymes already optimized for bacterial expression.50–51

Figure 3.

Clz9 and Tcz9 are capable of in vivo cannabinoid production (A) In vivo enzyme reactions. (B) LC-MS traces showing absorbance at 260 nm or 280 nm for predicted products. Both acid and non-acid compounds can be converted to CBC and CBCA-like products in vivo. (C) Scale up fermentative production of CBCA from CBGA at 1 M (360 mg) scale. (D) Absorbance at 260 nm showing conversion of CBGA to CBCA over 3 d in vivo.

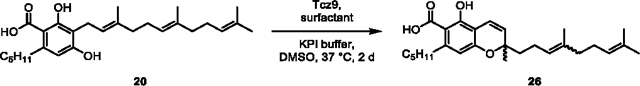

We also challenged both Clz9 and Tcz9 with larger substrates containing farnesyl side chains. Some plants, like Rhododendron, use farnesyl sidechain containing precursors to produce biologically relevant products.12 The potent anti-HIV natural product daurichromenic acid (DCA, 25) is biosynthesized through cyclization of grifolic acid (18) to a cannabichromene-containing product.52 DCA and analogs have also been produced heterologously in fungi.53 While the geranyl side-chain substrates each showed conversion to one product (Figure 2), we observed that the farnesyl containing substrates generated two products (Figure 4, Figures S12–S15). Notably, 19 had >99% conversion to daurichromenic acid (25) by Clz9, highlighting the immediate utility of these enzymes for production of biologically relevant molecules. Two substrates, 17 and 20, were selected as models to determine the identity of the two products produced. Purification required normal phase flash chromatography followed by reversed phase chromatography to separate the two products completely. 2D NMR analysis revealed that the two products were the E/Z isomers of the alkene in the prenyl chain. Interestingly, although a mixture of E/Z isomers were present in substrates used for assays, Clz9 and Tcz9 displayed different preferences in production of E/Z isomer products, potentially due to higher specificity for one starting material isomer over another. We also found that on analytical scale, substrate 20 yielded a second set of products (S1, Figure 4C) with a mass corresponding to a hydroxylated product (+16 amu, Figure S16). Upon scale up, however, we did not observe production of this product and so were unable to fully characterize it (Figure S17). We hypothesize benzylic hydroxylation occurs during catalysis (Scheme S2). The elongated nature of 20 could result in poor binding to the reactive ortho-quinone methide intermediate, allowing water access for hydroxylation chemistry.

Figure 4.

Clz9 and Tcz9 are capable of processing farnesyl-bearing substrates. (A) Scheme for conversion of acid and non-acid containing farnesyl substrates. (B) LC-MS traces showing absorbance at 280 nm for products produced from non-acid substrates. (C) LC-MS traces showing absorbance at 260 nm for product produced from acid-bearing substrates. The additional set of product peaks in the incubation with 20 at RT ~12.8 min (S1) are discussed in Figure S15–16. *Indicates full NMR characterization.

In summary, we discovered that bacterial BBE-like flavoenzymes Clz9 and Tcz9 can perform cannabinoid cyclization chemistry to produce cannabichromene scaffolds. These biocatalysts join a growing number of unusual flavoenzymes from marine bacteria.54 This reactivity is, thus far, unique to marine bacterial flavoenzymes Clz9, Tcz9, EncM, and closely related sequences. Machine-learning and bioinformatics approaches to identify other potential cannabinoid cyclases could not, at present, effectively predict this reactivity, underscoring the need for further exploration of BBE-like enzyme biochemistry, and specific active site features necessary for cannabinoid cyclase activity. The unique ability of Clz9 and Tcz9 to catalyze cyclization of non-carboxylic acid bearing substrates sets the stage for direct production of the most biologically relevant phytocannabinoid products – the desirable decarboxylated congeners. Though the current stereoselectivity of cannabichromene formation is poor, differences in the selectivity based on substrate and enzyme identity suggest active site restructuring to enforce conformation will enable highly selective catalysis. To this end, further studies are focusing on engineering Clz9 and Tcz9 for stereoselective production of cannabichromene and other cyclization isomers found natively in plants.

Methods

General Biological Methods

General considerations.

DNA sequences were codon-optimized for Escherichia coli and ordered from Twist Bioscience and subcloned into a pQE vector using primers and methods in the general cloning methods section below. Codon-optimized nucleotide sequences and amino acid sequences for Clz9, Tcz9 and YgaK can be found in the Supporting Information. All water used for preparation of bacteria growth media and protein purification buffers was purified from a Milli-Q purification system. All growth media was autoclaved for at least 45 minutes before use. All buffers were vacuum filtered with 0.2 μm nylon filters (Millipore Sigma). All centrifugation steps for protein purification were performed using a Beckman Coulter Avanti JXN-26 centrifuge using either the J-8.1 or J18 rotors. Cells were lysed by sonication with a QSonica Q500 ultrasonic processor. Protein samples were analyzed with Tris SDS-PAGE gels (BioRad) and Quick Coomassie stain (Anatrace). All purification steps were performed at room temperature unless otherwise indicated. Luria Broth (LB, Fisher Scientific) was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was supplemented with either Ampicillin (100 μM, “LB Amp”) or Kanamycin (50 μM, “LB Kan”). Terrific Broth (TB, Fisher Scientific) was also prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions.

General cloning methods.

Polymerase chain reactions (PCR) methods were performed to amplify the Clz9 and Tcz9 genes purchased from Twist Biosciences. Amplification was performed using the following primers:

5-TCGCATCACCATCACCATCACGGATCCATGGTTACCGCAGATCCGAGCAG-3’ and 5’-CTGAGCCTTTCGTTTTATTTGATGCCTCTAGATTAACGCAGCTGACGTGCGGCA-3’ for clz9 and 5’-GGATCGCATCACCATCACCATCACGGATCCATGGCAACCCCGAGCGCATTTA-3’ and 5’-TCGACTGAGCCTTTCGTTTTATTTGATGCCTCTAGATTAATCCAGCGGACCATCCAGCAG-3’ for tcz9

All PCR reactions were performed in an Eppendorf Mastercycler thermocycler using the following conditions: 1) 95 °C for 5 min, 2) 95 °C for 30 s, 3) 65 °C for 30 s, 4) 72 °C for 1 min, repeat steps 2–4 twenty times, then 72 °C for 5 min, and hold at 12 °C until retrieved from thermocycler. Reactions were analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis and bands corresponding to appropriate DNA size were cut out and incubated at 50 °C overnight with Agarose Dissolving Buffer (Zymo Research). Melted agarose segments were purified the next day using a Zymo Research Gel Purification Kit. Linearized pQE vectors were generated via PCR amplification using the following primers:

5’-TAATCTAGAGGCATCAAATAAAACGAAAGGCTCAG-3’ and 5’-GGATCCGTGATGGTGATGGTGATG-3’

The same method as above was used with a modification to the time held at 72 °C in step 4; for vector amplification this time was increased to 5 min. An aliquot (10 μL) was analyzed via gel electrophoresis, and if a band appeared at the appropriate size, DpnI (1.0 μL) was added to each 50 μL reaction and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. Then, Buffer PB (Qiagen, treated as 2x stock) was added to combined reactions in an Eppendorf tube and DNA purified on a silica gel spin column. DNA was washed with 100% EtOH and Plasmid Wash Buffer (Zymo) before elution with Milli-Q H2O. DNA concentrations were recorded using a NanoDrop1000.

Linearized vectors were combined with amplified inserts by Gibson assembly (50 °C for 60 min, 10 μL total reaction volume). The entire reaction was directly transformed into TOP10 Escherichia coli chemically competent cells. Colonies were screened using colony PCR to check for presence of genes of interest, and those containing diagnostic bands were expanded overnight in 5 mL LB broth supplements with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and plasmid DNA was extracted from colonies using a Zymo Research Plasmid Mini-prep Kit. Sequencing analysis confirmed successful plasmid generation (Genewiz).

Protein expression and purification.

The pQE-Tcz9/Clz9 plasmids were transformed into chemically competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells. The transformants were plated on agar plates containing ampicillin. Cells were expanded in LB Amp at 37 °C overnight. The overnight culture (25 mL) was used to inoculate 1 L Terrific Broth (TB) precultures incubated at 37 °C, 200 rpm overnight. The precultures were used to inoculate 1 L TB media supplemented with 0.4% glycerol and 100 μM Ampicillin in 2.4 L Fernbach flasks and incubated at 37 °C to mid-log phase (O.D.~0.8). The culture was then induced with isopropyl βD-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.5 mM final concentration), and incubated at 30 °C for 16–18 h. The cells were harvested at 4 °C by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 25 mL of lysis buffer (200 mM Tris Base, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, pH 7.8). The cells were sonicated using a QSonica Q500 ultrasonic processor and centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C. Enzymes were purified from clarified supernatants using a 5 mL HisTrap FF column (Cytiva). HisTrap columns were prepared by flowing 10x column volumes of MilliQ H2O, followed by 10x column volumes of lysis buffer by a peristaltic pump at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. Next, clarified lysate (approx. ~50 mL) was flowed through, followed by 10x column volumes of wash buffer (20 mM Tris Base, 200 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, pH 7.8) at a flow rate of 2.5 mL/min. Lastly, 5x column volumes elution buffer (20 mM Tris Base, 200 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 7.8) was flowed through (2.5 mL/min) and flow through was collected in 2 mL Eppendorf tubes. Fractions were tested with Bradford Assay (BioRad) for presence of protein. Fractions also appeared yellow, which aided in determining which fractions to test for presence of protein. Fractions containing protein were pooled and concentrated to 2.5 mL using 30 kDa Amicon centrifugal molecular weight cutoff filters. Concentrated proteins were desalted using PD-10 desalting columns (Cytiva) equilibrated with storage buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate, 10% glycerol, pH 7.8) following the manufacturer’s directions. Yields were determined by standard Bradford Assay. Average yields from Clz9 purification were ~24 mg/L and for Tcz9 ~20 mg/L. For YgaK, the average yield for purification was ~2 mg/L.

General analytical methods

General considerations.

Reversed phase separations and chiral chromatography was carried out using an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity series HPLC equipped with a degasser, quaternary pump, autosamplers, diode array, and fraction collector. For semi-preparative separations, a Kinetex 5 μm C18 100 Å, 250 × 10.0 mm column was used. For chiral analytical scale assays, as well as chiral purifications, a Diacel 5 μm ChiralPak® AD-H 250 × 4.6 mm column was used. For analytical scale reactions analyzed using LC-MS, an Agilent Technologies 1260 Infinity series HPLC equipped with a degasser, binary pump, autosampler, and diode array detector coupled to a 6530 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF MS equipped with a Kinetex 5 μm C18 100 Å, 150 × 4.6 mm column was used. Solvents used were HPLC grade or mass spectrometry grade respectively, and for all separations solvent A was water + 0.1% formic acid (FA) and solvent B was acetonitrile + 0.1% FA. Data was analyzed using MassHunter Workstation software version B.05.01 for high resolution LC-MS analysis and OpenLab CDS for single quadrupole LC-MS analysis, and traces were exported to Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism 6 for figures. For HPLC data, data was analyzed using OpenLab CDS software and exported to Microsoft Excel and Graphpad Prism 6 for figures. For purifications, fractions were checked by LC-MS and compounds pooled and dried using a Buchi rotary evaporator and a ThermoFisher SPD140DDA SpeedVac™ Vacuum concentrator.

High Resolution Analytical LC-MS Method:

0.750 mL/min flow rate, equilibration at 50% solvent B for 2 min followed by a linear 8-minute gradient to 100% solvent B. Hold at 100% solvent B until 17 minutes, followed by a linear 1-minute gradient back to 50% solvent B, and held there for 2 minutes to end the method.

Single Quadrupole Analytical LC-MS Method:

0.5 mL/min flow rate, equilibration at 60% solvent B for 0.5 min, followed by a linear 4-minute gradient to 95% solvent B. Hold 95% solvent B for 1.5 min, followed by a 1 min post-run to re-equilibrate back to 60% solvent B.

Semi-Preparative HPLC Method:

2mL/min flow rate, equilibration at 50% solvent B for 2 min followed by a linear 10-minute gradient to 100% solvent B. Hold at 100% B until 28 min, followed by a 2-minute post-run to re-equilibrate back to 50% solvent B.

Chiral purification method for 21 and 9:

1mL/min flow rate, equilibration at 60% solvent B for 1 min followed by a linear 5-minute gradient to 75% solvent B. Hold at 75% B for 5 min, followed by a 2-minute linear gradient to 95% solvent B then hold at 95% solvent B for 13 minutes. A 5-minute post-run to re-equilibrate back to 60% solvent B finishes the method.

Chiral purification method for 22 and 6:

1mL/min flow rate, equilibration at 60% solvent B for 1 min followed by a linear 5-minute gradient to 75% solvent B. Hold at 75% B for 5 min, followed by a 2-minute linear gradient to 95% solvent B then hold at 95% solvent B for 8 minutes. A 5-minute post-run to re-equilibrate back to 60% solvent B finishes the method.

Analytical scale enzyme assays for LC-MS analysis.

100 μL reactions comprised of 20 μM Tcz9 or Clz9, 1 μL of 20 mM stock substrate (200 μM final concentration, 1% DMSO final concentration) and potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5) were incubated at 37 °C for 20–24 h. The reaction was quenched by 100 μL methanol and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 2 min prior to filtering with 0.2 μm centrifugal filter. 10 μL of the filtered sample was injected and analyzed via high resolution LC-MS and analyzed using the methods described above. For assays with >200 μM final concentration of substrate, workup included dilution with additional methanol before filtering to ensure final concentration of substrate in all samples for LC-MS analysis was 100 μM.

Chiral chromatography.

100 μL reactions comprised of 40 μM Tcz9 or Clz9, 5 μL of 20 mM stock substrate (1 mM final concentration, 5% DMSO final concentration) and potassium phosphate buffer were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 100 μL methanol and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 2 min prior to filtering with 0.2 μm centrifugal filter. 20 μL of the filtered sample was injected onto the HPLC and analyzed using the methods as described above. Chiral chromatographic separations were performed by dissolving purified products in HPLC grade methanol and filtering with 0.2 μm centrifugal filter before injection. Injection volumes of 20–50 μL were used depending on peak separation. The same methods were used for purification as for analytical chromatography. Peaks were collected in elution order and fractions were pooled and collected for CD spectroscopy analysis.

In vivo analytical scale reactions.

5 ml starters of Tcz9 or Clz9 in LB Amp were left at 37°C overnight and then 400 μL was used to inoculate 5 ml LB Amp and incubated at 37 °C to mid-log phase (O.D.~0.8). The culture was then induced with IPTG (0.5 mM final concentration) and incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h. The cells were harvested at 4 °C by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 10 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 500 μL of potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5), and 100 μL were used per reaction along with 1 μL of 20 mM stock substrate (200 μM final concentration, 1% DMSO final concentration). The reaction was incubated at 37°C overnight. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 100 μL methanol and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 2 min prior to filtering with 0.2 μm centrifugal filter. 10 μL of the filtered sample was injected onto the LC-MS and analyzed using the methods as described above.

Enzyme screening workflow.

1 mL starters of the 18 enzymes listed in Figure S6 in LB Kan, and Tcz9 and Clz9 in 1 mL of LB Amp were incubated overnight at 37 °C. The next day, 400 μL was inoculated in 5 mL of TB Kan or TB Amp and incubated at 200 rpm and 37 °C until O.D. ~0.8. Cells were induced with IPTG (250 μM final concentration) and incubated at 200 rpm and 30 °C overnight. Cells were harvested at 4 °C by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (200 μL, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 0.5 mg/mL polymyxin B, and 1 μg/mL DNAse) and incubated at 200 rpm and 30 °C for 1 h. Lysate was clarified at 5000 rpm for 10 min, and clarified supernatant (100 μL) was plated in a 96-well polypropylene plate containing 3 (200 μM final concentration, 1% DMSO final concentration). The reactions were incubated at 200 rpm and 37 °C overnight. Reactions were dried using a ThermoFisher SPD140DDA SpeedVac™ Vacuum concentrator, and residue resuspended in HPLC grade MeOH (100 μL) and filtered using a 0.2 μm PTFE filter plate and a Waters 96-well plate vacuum adapter with an Agilent brand 96-well polypropylene plate underneath to catch the flow through. Samples were injected onto an Aglient single quadrupole UPLC-MS iQ using the Single Quadrupole Analytical LC-MS method described above.

General Chemical Methods

Computational methods.

Using an energy window of 21.0 kJ/mol, conformer searches were conducted for model compounds 21-R and 22-R within Schrödinger Macromodel software using the Monte Carlo Minimum method (MCMM) and the OPLS3 forcefield. Each of the resultant conformational ensembles (21-R and 22-R, 59 and 150 conformers respectively) underwent density functional theory (DFT) geometry optimization (GO) calculations. The first GO at the B3LYP/6–31g (d) level of theory with empirical dispersion in the gas phase, followed by a second GO at the B3LYP/6–311G(d) level of theory using Gaussian 1655 incorporating the polarizable continuum model (PCM)56 for methanol. Duplicate and high-energy conformers (above 3.0 kcal/mol) were filtered from each DFT geometry optimized conformational set with electronic transition and rotational strength calculations performed using the time-dependent density functional (TDDFT) method at the CAM-B3LYP/6–311++G(d,p) level of theory and the PCM solvent effect in methanol. Boltzmann-weighted UV and ECD spectra were generated using the freely available SpecDis software (version 1.71).57 Experimental and calculated UV and ECD data was matched for comparative ECD analyses using gaussian band shapes and sigma gamma values (eV); 0.28 for enantiomers 6-R and S, 9-R and S, 21-R and S, and 22-R and S, while UV correction of +12 for 6-R and S, +10 for 9-R and S, +10 for 21-R and S, and +10 for 22-R and S were also applied. Automation processes with the high-performance computing cluster (HPC) were carried out with modified Python scripts based upon the appended Willoughby protocol58 using a Windows 10 PC.

UV-Vis spectroscopy.

UV-Vis spectra were collected for each of the eight enantiomers purified on an Agilent Technologies Cary 60 UV-vis spectrophotometer. Molecules were dissolved in HPLC grade methanol to a starting concentration of 1 mg/mL and diluted as needed to ensure peaks appearing at 280–400 nm were between 0.1–1 AU on the spectrometer. A quartz cuvette with pathlength 10 mm was used for data collection, and data was collected in 2 nm increments.

CD Spectroscopy.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy was acquired on an Aviv model 215 CD spectrometer at molecule concentrations of 100–10 μg/mL, optimizing for signal while keeping dynode at values <500. Spectra were collected in HPLC grade methanol using a quartz cuvette with a pathlength of 1 mm. Data were collected every 1 nm, and 10–15 scans were performed for each molecule, including the blank. Experimental CD data (6-R and S, 9-R and S, 21-R and S, and 22-R and S) was smoothed using the freely available Spectragryph59 software and plotted against time dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) calculated ECD spectra for model compounds 21-R and 22-R.

General synthetic methods.

Unless stated otherwise, reactions were conducted in oven-dried glassware under an atmosphere of argon using anhydrous solvents. All reagents were obtained from MilliporeSigma, Fisher Scientific, or Alfa Aesar and were used without further purification. Flash column chromatography was performed in normal phase using a Teledyne ISCO CombiFlash® Rf+ Lumen™ system. NMR spectra were obtained on a 500 MHz JEOL NMR spectrometer with either a 3.0 mm or 5.0 mm probe. Data for 1H NMR spectra are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ ppm), multiplicity, coupling constant (Hz), and integration. Data for 13C NMR spectra are reported in terms of chemical shift. NMR data analysis was performed using MestreNova.

General procedure for prenylation.

(14) This procedure was adapted from literature precedent.36 To a 200 mL round bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was added 12 (1.04 g, 5.8 mmol, 1 equiv.) and chloroform (60 mL) and the mixture was stirred until all 12 dissolved (30 min). Geraniol (1.8 mL, 10 mmol, 1.8 equiv.) and p-toluenesulfonic acid (0.048 g, 0.27 mmol, 0.05 equiv.) were added to the flask, which was then capped and stirred overnight at room temperature. Upon addition of the p-toluenesulfonic acid, the color changed from clear to pale yellow to dark orange. After 18 h stirring, the solution was concentrated in vacuo. The resulting thick brown oil was purified by flash chromatography (SiO2 EtOAc in hexanes) to afford 14 as a pale-yellow oil (0.66 g, 46% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.24 (s, 1H), 5.25 (t, J = 6.8, 1H), 5.05 (t, J = 6.2, 1H) 3.38 (d, J = 7, 2H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.10 (t, J = 6.5, 2H), 2.07–2.03 (m, 2H), 1.82 (s, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.4, 139.3, 138.0, 132.5, 124.2, 122.2, 110.9, 109.5, 40.2, 31.4, 26.9, 26.2, 22.6, 21.5, 18.2, 16.7.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C17H23O2 [M – H]−: 259.1698; found 259.1783.

(15) Prepared according to the general procedure for prenylation, using 13 (0.516 g, 2.9 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), chloroform (30 mL), geraniol (0.90 mL, 5.0 mmol, 1.8 equiv.), and p-toluenesulfonic acid (0.037 g, 0.215 mmol, 0.05 equiv.) to give 15 as a white solid (0.19 g, 21% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.28 (s, 2H), 5.67 (s, 2H), 5.31 (t, J = 6.3, 1H), 5.09 (m, 1H), 3.43 (d, J = 6.8, 2H), 2.45 (t, J = 7.5, 2H), 2.16–2.05 (m, 4H), 1.83 (s, 3H), 1.71 (s, 3H), 1.62 (s, 3H), 1.32 (br s, 6H), 0.91 (t, J = 6.1, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.3, 143.0, 139.1, 132.4, 124.3, 122.3, 111.3, 108.8, 40.1, 36.0, 32.0, 31.2, 26.8, 26.1, 23.0, 22.7, 18.1, 16.6, 14.5.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C21H31O2 [M – H]−: 315.2324; found 315.2395.

(16) Prepared according to general procedure for prenylation, using 12 (0.508 g, 4.0 mmol, 1 equiv.), chloroform (30 mL), farnesol (1.25 mL, 5.0 mmol, 1.3 mmol), and p-toluenesulfonic acid (0.030 g, 0.17 mmol, 0.04 equiv.) to give 16 as a pale-orange oil (0.39 g, 29% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.22 (s, 2H), 5.21 (t, J = 7.0, 1H), 5.13–5.05 (m, 2H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 3.38 (d, J = 6.9, 2H), 2.21 (s, 3H), 2.12–2.01 (m, 8H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.3, 139.3, 137.9, 136.0, 131.7, 124.8, 124.1, 122.2, 111.0, 109.5, 40.1, 32.4, 27.0, 26.8, 26.2, 23.8, 23.6, 21.5, 18.1, 16.7.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C22H31O2 [M – H]−: 327.2324; found 327.2390.

(17) Prepared according to general procedure for prenylation, using olivetol (0.20 g, 1.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), toluene (10 mL), farnesol (0.50 mL, 2.0 mmol, 1,8 equiv.), and p-toluenesulfonic acid (0.012 g, 0.070 mmol, 0.063 equiv.) to give 17 as a pale-orange oil (0.15 g, 35% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.24 (s, 2H), 5.37 (s, 2H), 5.28 (t, J = 6.5, 1H), 5.15–5.04 (m, 2H), 3.40 (d, J = 6.8, 2H), 2.43 (t, J = 7.6, 2H), 2.14–1.96 (m, 12H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.99 (s, 6H), 1.30 (s, 5H), 0.88 (t, J = 6.4, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.0, 142.7, 138.9, 135.7, 131.4, 124.5, 123.7, 122.0, 110.8, 108.4, 39.8, 39.7, 35.6, 31.6, 30.9, 26.8, 26.5, 25.8, 22.7, 22.4, 17.8, 16.3, 16.1, 14.2

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C26H39O2 [M – H]−: 383.2950; found 383.2909.

General procedure for carboxylation.

(18) This procedure was adapted from literature precedent.36 An oven-dried 20 mL flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with 14 (0.32 g, 1.2 mmol, 1 equiv.) dissolved in anhydrous DMF (5 mL) and methyl magnesium carbonate solution (1.8 M, 7.0 mL, 12.4 mmol, 10 equiv.). The flask was stirred with heating at 120 °C for 2.5 h or until TLC showed full conversion. The reaction was cooled to room temperature and 2 M HCl was added to reach pH ~2, and the resulting solution was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with saturated brine solution (5 × 10 mL). The organic phase was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting brown liquid was dissolved in toluene (2 × 50 mL) and concentrated in vacuo. The resulting brown residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain 18 as a dingy orange solid (0.14 g, 38% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.90 (s, 1H), 6.27 (s, 1H), 5.27 (t, J = 7.1, 1H), 5.05 (tt, J = 6.7, 1.3, 1H), 3.43 (d, J = 7.1, 2H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.13–2.03 (m, 4H), 1.81 (s, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.6, 164.1, 161.0, 143.0, 139.5, 132.5, 124.3, 121.8, 112.3, 112.0, 104.3, 40.2, 26.8, 26.2, 24.7, 22.5, 18.2, 16.7.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for [M – H]−: 303.1560; found 303.1578.

(3) Prepared according to general procedure for carboxylation, using 15 (0.19 g, 0.60 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), DMF (3 mL), and methyl magnesium carbonate solution (1.8 M, 3 mL, 6.0 mmol, 10.0 equiv.) to give 3 as a pale yellow solid (0.080 g, 37% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.91 (s, 1H), 6.28 (s, 1H), 5.28 (t, J = 7.4, 1H), 5.06 (tt, J = 6.7, 1.3, 1H), 3.44 (d, J = 7.1, 2H), 2.89 (t, J = 7.8, 2H), 2.13–2.04 (m, 4H), 1.82 (s, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.38–1.30 (m, 5H, 0.90 (t, J = 7.0, 5H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.6, 164.1, 161.0, 148.0, 139.6, 132.5, 124.2, 121.8, 112.0, 111.8, 103.6, 40.20, 37.05, 32.5, 32.0, 26.8, 26.2, 23.0, 22.6, 18.2, 16.7, 14.6.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C22H31O4 [M – H]−: 359.2222; found 359.2216.

(19) Prepared according to general procedure for carboxylation, using 16 (0.15 g, 0.45 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), DMF (2.5 mL), and methyl magnesium carbonate solution (1.8 M, 2.5 mL, 4.5 mmol, 10.0 equiv.) to give 19 as a light purple solid (0.067 g, 40% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.88 (s, 1H), 6.26 (s, 1H), 5.27 (t, J = 6.4, 1H), 5.12–5.05 (m, 2H), 3.42 (d, J = 7.0, 2H), 2.52 (s, 3H), 2.13–1.99 (m, 8H), 1.82 (s, 3H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.25 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.8, 163.7, 160.5, 142.5, 139.3, 135.7, 131.4, 124.5, 123.6, 121.3, 111.9, 111.5, 103.8, 39.8, 39.7, 26.8, 26.4, 25.8, 24.3, 22.1, 17.8, 16.3, 16.1

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C23H31O4 [M – H]−: 371.2222; found 371.2236.

(20) Prepared according to general procedure for carboxylation, using 17 (0.15 g, 0.40 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), DMF (2.2 mL), and methyl magnesium carbonate solution (1.8 M, 2.2 mL, 4.0 mmol, 10.0 equiv.) to give 20 as a deep red oil (0.054 g, 40% yield).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.93 (s, 1H), 6.28 (s, 1H), 5.29 (t, J = 6.7, 1H), 5.13–5.05 (m, 2H), 3.44 (d, J =7.1, 2H), 2.86 (t, J = 7.5, 2H), 2.15–2.00 (m, 8H), 1.86 (s, 3H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 4H), 1.26 (s, 3H), 0.90–0.80 (m, 5H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.6, 164.1, 160.9, 147.9, 139.2, 139.2, 136.0, 131.7, 124.9, 122.0, 121.9, 112.1, 103.7, 40.2, 40.1, 37.0, 32.5, 31.9, 27.1, 26.8, 26.7, 26.2, 23.0, 18.2, 16.7, 16.5, 14.5.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C27H39O4 [M – H]−: 427.2848; found 427.2967.

Enzymatic transformations

(21) To a 125 mL autoclaved Erlenmeyer flask was added 14 (0.0547 g) dissolved in DMSO (5 mL) and potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, 45 mL). Next, Tcz9 (200 μM stock, 1.5 mL) was added to the flask to a final concentration of 6 μM along with D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 surfactant (0.502 g, 1% w/v) to facilitate substrate solubility. The flask was shaken (200 rpm) at 37 °C until conversion appeared >95% by LC-MS (9 d), and then the reaction was acidified with HCl (2 M) until it reached pH ~2, and EtOAc (50 mL) was added. The flask was shaken (100 rpm) to extract at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 × g and the organic layer taken, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain 21 (10.7 mg, 20% yield) as a purple oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.62 (d, J = 10, 1H), 6.24 (s, 1H), 6.11 (s, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 10, 1H), 5.10 (tt, J = 7.2, 1.4, 1H), 4.88 (s, 1H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.15–2.07 (m, 2H), 1.75–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.58 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.6, 151.5, 140.0, 132.1, 127.6, 124.7, 117.2, 110.3, 108.8, 107.2, 78.7, 41.5, 26.7, 26.2, 23.3, 22.0, 18.1.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C17H21O2 [M – H]−: 257.1542; found 257.1537.

(22) To a 125 mL autoclaved Erlenmeyer flask was added 18 (0.0497 g) dissolved in DMSO (2 mL) and potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, 20 mL). Next, Tcz9 (200 μM stock, 2 mL) was added to the flask to a final concentration of 20 μM. The flask was shaken (200 rpm) at 37 °C until conversion appeared >95% by LC-MS (4 d), and then the reaction was acidified with HCl (2 M) until it reached pH ~2, and EtOAc (50 mL) was added. The flask was shaken (100 rpm) to extract at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 × g and the organic layer taken, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain 22 (22 mg, 44% yield) as a light purple solid.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.73 (d, J = 10.1, 1H), 6.23 (s, 1H), 5.48 (d, J = 10.1, 1H), 5.09 (t, J = 7, 1H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 2.09 (q, J = 7.5, 2H), 1.79–1.72 (m, 2H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.57, (s, 3H), 1.40 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.9, 160.8, 159.1, 144.5, 132.0, 126.4, 124.0, 116.8, 112.3, 107.2, 103.7, 80.2, 41.8, 27.3, 25.8, 24.6, 22.8, 17.8.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C18H21O4 [M – H]−: 301.1439; found 301.1359.

(9 and 6) To a 125 mL autoclaved Erlenmeyer flask was added 3 (0.0597 g) dissolved in DMSO (5 mL) and potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, 45 mL). Next, Tcz9 (100 μM stock, 4 mL) was added to the flask to a final concentration of 8 μM. The flask was shaken (200 rpm) at 37 °C until conversion appeared >95% by LC-MS (3 d), and then the reaction was acidified with HCl (2 M) until it reached pH ~2, and EtOAc (50 mL) was added. The flask was shaken (100 rpm) to extract at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 × g and the organic layer taken, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain 6 (39.1 mg, 66% yield) as an off white solid and 3 (4.3 mg) as a light brown residue.

Characterization data for 6:

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.73 (s, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 10.1, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 10.1, 1H), 5.09 (t, J = 8.2, 1H), 2.89 (t, J = 7.4, 2H), 2.10 (q, J = 7.5, 2H), 1.83–1.71 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.58 (s, 6H), 1.43 (s, 3H), 1.35 (s, 4H), 0.91 (t, J = 6.5, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 176.7, 161.2, 159.5, 150.0, 132.4, 126.8, 124.3, 117.2, 112.0, 107.6,103.4, 80.5, 42.2, 37.3, 32.5, 31.8, 27.7, 26.2, 23.2, 23.0, 18.1, 14.5.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C22H29O4 [M – H]−: 357.2065; found 357.2037.

Characterization data for 9:

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.62 (d, J = 10.0, 1H), 6.26 (s, 1H), 6.12 (s, 1H), 5.50 (d, J = 10.0, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 7.2, 1H), 4.71 (br s, 1H), 2.44 (t, J = 7.8, 2H), 2.15–2.02 (m, 3H), 1.66 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 5H), 1.38 (s, 3H), 1.32–1.28 (m, 5H), 0.88 (t, J = 6.8, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.5, 151.5, 145.2, 132.1, 127.7, 124.7, 117.2, 109.6, 108.2, 107.4,78.6, 41.5, 36.4, 32.0, 31.1, 26.7, 26.2, 23.2, 23.0, 18.1, 14.5.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C21H29O2 [M – H]−: 313.2167; found 313.2205.

(23) To a 125 mL autoclaved Erlenmeyer flask was added 16 (0.0620 g) dissolved in DMSO (15 mL) and potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, 35 mL). Next, Tcz9 (200 μM stock, 1.5 mL) was added to the flask to a final concentration of 6 μM along with D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 surfactant (0.9557 g, 1% w/v) to facilitate substrate solubility. The flask was shaken (200 rpm) at 37 °C until conversion stalled (at 50% conversion) by LC-MS (12 d), and then the reaction was acidified with HCl (2 M) until it reached pH ~2, and EtOAc (50 mL) was added. The flask was shaken (100 rpm) to extract at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 × g and the organic layer taken, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was first purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain crude 21 as a mixture with the surfactant. Further purification was carried out via semi-preparative HPLC to yield separate E and Z isomers (0.0047 g, 8% yield; E = 0.003 g, Z = 0.0017 g).

E isomer data

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.61 (d, J = 10.0, 1H), 6.24 (s, 1H), 6.11 (s, 1H), 5.49 (d, J = 10.0, 1H), 5.09 (qnt, J = 7.1, 2H), 4.73 (s, 1H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.15–2.07 (m, 2H), 2.06–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.98–1.92 (m, 2H), 1.79–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 3H), 1.58 (s, 6H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ154.3, 151.2, 139.7, 135.4, 131.5, 127.4, 124.5, 124.2, 116.9, 110.0, 108.4, 78.4, 41.3, 39.9, 29.9 26.9, 26.5, 25.9, 22.8, 21.7, 17.9, 16.1, 14.3.

Z isomer data

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.60 (d, J = 10.0, 1H), 6.23 (s, 1H), 6.11 (s, 1H), 5.48 (d, J = 10.0, 1H), 5.10 (q, J = 6.7, 2H), 4.71 (s, 1H), 2.20 (s, 3H), 2.13–2.06 (m, 2H), 2.01 (s, 4H), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.60 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 3H), 1.37 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 154.3, 151.2, 139.7, 135.6, 131.7, 127.4, 125.0, 124.5, 116.9, 110.0, 108.4, 78.3, 41.5, 32.0, 29.9, 26.7, 26.4, 25.9, 23.5, 22.8, 21.7, 17.8.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C22H29O4 [M – H]−: 325.2165; found 325.2159.

(26) To a 125 mL autoclaved Erlenmeyer flask was added 20 (0.0376 g) dissolved in DMSO (5 mL) and potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, 45 mL). Next, Tcz9 (200 μM stock, 2 mL) was added to the flask to a final concentration of 8 μM. The flask was shaken (200 rpm) at 37 °C until conversion appeared >95% by LC-MS (2 d), and then the reaction was acidified with HCl (2 M) until it reached pH ~2, and EtOAc (50 mL) was added. The flask was shaken (100 rpm) to extract at room temperature for 1 h. The mixture was then centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 × g and the organic layer taken, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain 26 (0.0209 g, 56% yield) as a mixture of E/Z isomers as a bright orange oil.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 11.79 (s, 1H), 6.73 (d, J = 10.1, 1H), 6.24 (d, J = 3.4, 1H), 5.48 (overlapping doublets, J = 10.1, 10.1, 1H), 5.13–5.05 (m, 2H), 2.88 (t, J = 7.8, 2H), 2.15–2.07 (m, 2H), 2.06–2.00 (m, 2H), 1.99–1.91 (m, 2H), 1.8– 1.70 (m, 2H), 1.67 (s, 5H), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.57 (s, 3H), 1.41 (d, J = 3.7, 2H), 1.37–1.32 (m, 5H), 1.25 (s, 4H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.6, 160.8, 159.1, 149.5, 135.7, 135.6, 131.7, 131.5, 126.5, 126.4, 123.8, 116.9, 111.6, 107.2, 103.1, 80.2, 80.1, 42.1, 41.8, 39.8, 36.9, 32.1, 32.5, 29.8, 27.3, 26.8, 25.8, 23.5, 22.6, 17.8, 17.8, 16.1, 14.2.

HRMS (ES-) m/z calc’d for C27H37O4 [M – H]−: 425.2692; found 425.2628.

In vivo production of CBCA.

To a 1 L flask of autoclaved TB was added 40 mL preculture of BL21 DE E. coli cells transformed with a pQE vector containing wild type Tcz9. Culture was grown with shaking (200 rpm) at 30 °C until OD=0.8 and induced with 1 M IPTG (500 μL, 0.5 mM final concentration). Additionally, riboflavin (100 mg) suspended in 1 mL MilliQ H2O and CBGA (0.3577 g, gift from Amyris®) dissolved in 20 mL DMSO were added to the culture at the same time as induction. The culture was shaken (200 rpm) at 30 °C for 4 d. Each day, a 1 mL aliquot of the culture was taken, extracted with CH2Cl2, dried, resuspended in MeOH and filtered for LC-MS analysis to check conversion to CBCA. After 4 d, when the conversion appeared to stall, the entire culture was extracted with 800 mL EtOAc with shaking (100 rpm) for 2 h. The mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 × g, and the organic layer was taken, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue (0.8351 g) was purified by flash column chromatography (SiO2, EtOAc in hexanes) to obtain 3 (97 mg, 26% recovery) as an off-white solid, 6 (9.6 mg) as a brown oil and 9 (105 mg, 30% yield) as an off white tacky solid. 1H and 13C NMR matched reported values as well as tabulated values listed above.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding was generously provided by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (1R01-AT012641) to B.S.M. and the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences (1F32-GM150232–01) to A.C.L. We thank Amyris for providing CBG and CBGA substrates. We also thank Brendan Duggan and Anthony Mrse for NMR assistance, Alexander Hoffnagle for CD assistance, and members of the Moore lab for insightful discussions and advice.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BBE-like enzyme family

Berberine-bridge type enzymes

- CBC

cannabichromene

- CBCA

cannabichromenic acid

- CBD

cannabidol

- CBDA

cannabidiolic acid

- CBG

cannabigerol

- CBGA

cannabigerolic acid

- CD

circular dichroism

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- LC-MS

liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- THC

tetrahydrocannabinol

- THCA

tetrahydrocannabinolic acid

- VAO

vanillyl alcohol-oxidase

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org. General procedures, experimental details, supplemental figures, and NMR spectra (PDF)

REFERENCES

- 1.Russo EB; Jiang H-E; Li X; Sutton A; Carboni A; del Bianco F; Mandolino G; Potter DJ; Zhao Y-X; Bera S; Zhang Y-B; Lü E-G; Ferguson DK; Hueber F; Zhao L-C; Liu C-J; Wang Y-F; Li C-S, Phytochemical and genetic analyses of ancient Cannabis from central Asia. J. Exp. Biol. 2008, 59 (15), 4171–4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maule WJ, Medical uses of marijuana (Cannabis sativa): Fact or fallacy? Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2015, 72 (2), 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charitos IA; Gagliano-Candela R; Santacroce L; Bottalico L, The cannabis spread throughout the continents and its therapeutic use in history. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 21 (3), 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rella JG, Recreational Cannabis use: Pleasures and pitfalls. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2015, 82 (11), 765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samuel P, History of medical Cannabis. J. Pain Manag. 2016, 9 (4), 387. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda LA; Lolait SJ; Brownstein MJ; Young AC; Bonner TI, Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned cDNA. Nature 1990, 346 (6284), 561–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devane WA; Hanuš L; Breuer A; Pertwee RG; Stevenson LA; Griffin G; Gibson D; Mandelbaum A; Etinger A; Mechoulam R, Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 1992, 258 (5090), 1946–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abu-Sawwa R; Stehling C, Epidiolex (cannabidiol) primer: Frequently asked questions for patients and caregivers. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 25 (1), 75–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badowski ME, A review of oral cannabinoids and medical marijuana for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: A focus on pharmacokinetic variability and pharmacodynamics. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2017, 80 (3), 441–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todaro B, Cannabinoids in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2012, 10 (4), 487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perucca E, Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy: Hard evidence at last? J. Epilepsy Res. 2017, 7 (2), 61–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gülck T; Møller BL, Phytocannabinoids: Origins and biosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25 (10), 985–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson PB, Phytocannabinoid pharmacology: Medicinal properties of Cannabis sativa constituents aside from the “big two”. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84 (1), 142–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinjyo N; Di Marzo V, The effect of cannabichromene on adult neural stem/progenitor cells. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 63 (5), 432–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollastro F; Caprioglio D; Del Prete D; Rogati F; Minassi A; Taglialatela-Scafati O; Munoz E; Appendino G, Cannabichromene. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13 (9), 1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prandi C; Blangetti M; Namdar D; Koltai H, Structure-activity relationship of cannabis derived compounds for the treatment of neuronal activity-related diseases. Molecules 2018, 23 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Appendino G; Gibbons S; Giana A; Pagani A; Grassi G; Stavri M; Smith E; Rahman MM, Antibacterial cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: A structure−activity study. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71 (8), 1427–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen G-N; Jordan EN; Kayser O, Synthetic strategies for rare cannabinoids derived from Cannabis sativa. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85 (6), 1555–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anand R; Cham PS; Gannedi V; Sharma S; Kumar M; Singh R; Vishwakarma RA; Singh PP, Stereoselective synthesis of nonpsychotic natural cannabidiol and its unnatural/terpenyl/tail-modified analogues. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87 (7), 4489–4498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Favero GR; de Melo Pereira GV; de Carvalho JC; de Carvalho Neto DP; Soccol CR, Converting sugars into cannabinoids: the state-of-the-art of heterologous production in microorganisms. Fermentation 2022, 8 (2). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas F; Schmidt C; Kayser O, Bioengineering studies and pathway modeling of the heterologous biosynthesis of tetrahydrocannabinolic acid in yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104 (22), 9551–9563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zirpel B; Stehle F; Kayser O, Production of δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid from cannabigerolic acid by whole cells of Pichia (komagataella) pastoris expressing δ9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid synthase from Cannabis sativa. Biotechnol Lett 2015, 37 (9), 1869–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo X; Reiter MA; D’Espaux L; Wong J; Denby CM; Lechner A; Zhang Y; Grzybowski AT; Harth S; Lin W; Lee H; Yu C; Shin J; Deng K; Benites VT; Wang G; Baidoo EEK; Chen Y; Dev I; Petzold CJ; Keasling JD, Complete biosynthesis of cannabinoids and their unnatural analogues in yeast. Nature 2019, 567 (7746), 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkler A; Motz K; Riedl S; Puhl M; Macheroux P; Gruber K, Structural and mechanistic studies reveal the functional role of bicovalent flavinylation in berberine bridge enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284 (30), 19993–20001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daniel B; Konrad B; Toplak M; Lahham M; Messenlehner J; Winkler A; Macheroux P, The family of berberine bridge enzyme-like enzymes: A treasure-trove of oxidative reactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 632, 88–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leferink NGH; Heuts DPHM; Fraaije MW; van Berkel WJH, The growing VAO flavoprotein family. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 474 (2), 292–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattevi A; Fraaije MW; Mozzarelli A; Olivi L; Coda A; van Berkel WJH, Crystal structures and inhibitor binding in the octameric flavoenzyme vanillyl-alcohol oxidase: The shape of the active-site cavity controls substrate specificity. Structure 1997, 5 (7), 907–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mantovani SM; Moore BS, Flavin-linked oxidase catalyzes pyrrolizine formation of dichloropyrrole-containing polyketide extender unit in chlorizidine A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135 (48), 18032–18035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purdy TN; Kim MC; Cullum R; Fenical W; Moore BS, Discovery and biosynthesis of tetrachlorizine reveals enzymatic benzylic dehydrogenation via an ortho-quinone methide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (10), 3682–3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purdy TN; Moore BS; Lukowski AL, Harnessing ortho-quinone methides in natural product biosynthesis and biocatalysis. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85 (3), 688–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Razdan RK, Structure-activity relationships in cannabinoids. Pharmacol. Rev. 1986, 38 (2), 75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bow EW; Rimoldi JM, The structure–function relationships of classical cannabinoids: CB1/CB2 modulation. Perspect. Medicinal Chem. 2016, 8, PMC.S32171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinelli F; Capparelli E; Abate C; Colabufo NA; Contino M, Perspectives of cannabinoid type 2 receptor (CB2R) ligands in neurodegenerative disorders: Structure–affinity relationship (SAFIR) and structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60 (24), 9913–9931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zirpel B; Kayser O; Stehle F, Elucidation of structure-function relationship of THCA and CBDA synthase from Cannabis sativa. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 284, 17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taura F; Morimoto S; Shoyama Y, Purification and characterization of cannabidiolic-acid synthase from Cannabis sativa: Biochemical analysis of a novel enzyme that catalyzes the oxidocyclization of Cannabigerolic acid to Cannabidiolic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271 (29), 17411–17416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoyama Y; Tamada T; Kurihara K; Takeuchi A; Taura F; Arai S; Blaber M; Shoyama Y; Morimoto S; Kuroki R, Structure and function of Δ1-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid (THCA) synthase, the enzyme controlling the psychoactivity of Cannabis sativa. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 423 (1), 96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno-Sanz G, Can you pass the acid test? Critical review and novel therapeutic perspectives of δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1 (1), 124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verhoeckx KCM; Korthout HAAJ; van Meeteren-Kreikamp AP; Ehlert KA; Wang M; van der Greef J; Rodenburg RJT; Witkamp RF, Unheated Cannabis sativa extracts and its major compound thc-acid have potential immune-modulating properties not mediated by CB1 and CB2 receptor coupled pathways. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006, 6 (4), 656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwata N; Kitanaka S, New cannabinoid-like chromane and chromene derivatives from Rhododendron anthopogonoides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59 (11), 1409–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quaghebeur K; Coosemans J; Toppet S; Compernolle F, Cannabiorci- and 8-chlorocannabiorcichromenic acid as fungal antagonists from Cylindrocarpon olidum. Phytochemistry 1994, 37 (1), 159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zetzsche LE; Yazarians JA; Chakrabarty S; Hinze ME; Murray LAM; Lukowski AL; Joyce LA; Narayan ARH, Biocatalytic oxidative cross-coupling reactions for biaryl bond formation. Nature 2022, 603 (7899), 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher BF; Snodgrass HM; Jones KA; Andorfer MC; Lewis JC, Site-selective C–H halogenation using flavin-dependent halogenases identified via family-wide activity profiling. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5 (11), 1844–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukowski AL; Hubert FM; Ngo T-E; Avalon NE; Gerwick WH; Moore BS, Enzymatic halogenation of terminal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (34), 18716–18721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tararina MA; Allen KN, Bioinformatic analysis of the flavin-dependent amine oxidase superfamily: Adaptations for substrate specificity and catalytic diversity. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432 (10), 3269–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeoung J-H; Dobbek H, ATP-dependent substrate reduction at an [Fe8S9] double-cubane cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115 (12), 2994–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teufel R; Miyanaga A; Michaudel Q; Stull F; Louie G; Noel JP; Baran PS; Palfey B; Moore BS, Flavin-mediated dual oxidation controls an enzymatic favorskii-type rearrangement. Nature 2013, 503 (7477), 552–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hon J; Marusiak M; Martinek T; Kunka A; Zendulka J; Bednar D; Damborsky J, Soluprot: Prediction of soluble protein expression in Escherichia coli. Bioinformatics 2021, 37 (1), 23–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hon J; Borko S; Stourac J; Prokop Z; Zendulka J; Bednar D; Martinek T; Damborsky J, Enzymeminer: Automated mining of soluble enzymes with diverse structures, catalytic properties and stabilities. Nuc. Acids Res. 2020, 48 (W1), W104–W109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calcaterra A; Cianfoni G; Tortora C; Manetto S; Grassi G; Botta B; Gasparrini F; Mazzoccanti G; Appendino G, Natural cannabichromene (CBC) shows distinct scalemicity grades and enantiomeric dominance in Cannabis sativa strains. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86 (4), 909–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan Z; Clomburg JM; Gonzalez R, Synthetic pathway for the production of olivetolic acid in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 2018, 7 (8), 1886–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qian S; Clomburg JM; Gonzalez R, Engineering Escherichia coli as a platform for the in vivo synthesis of prenylated aromatics. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116 (5), 1116–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taura F; Iijima M; Lee J-B; Hashimoto T; Asakawa Y; Kurosaki F, Daurichromenic acid-producing oxidocyclase in the young leaves of Rhododendron dauricum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9 (9), 1329–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okada M; Saito K; Wong CP; Li C; Wang D; Iijima M; Taura F; Kurosaki F; Awakawa T; Abe I, Combinatorial biosynthesis of (+)-daurichromenic acid and its halogenated analogue. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (12), 3183–3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teufel R; Agarwal V; Moore BS, Unusual flavoenzyme catalysis in marine bacteria. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 31, 31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomasi J; Mennucci B; Cammi R, Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models Chem. Rev. 2005, 105 (8), 2999–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Petersson GA; Nakatsuji H; Li X; Caricato M; Marenich AV; Bloino J; Janesko BG; Gomperts R; Mennucci B; Hratchian HP; Ortiz JV; Izmaylov AF; Sonnenberg JL; Williams-Young D; Ding F; Lipparini F; Egidi F; Goings J; Peng B; Petrone A; Henderson T; Ranasinghe D; Zakrzewski VG; Gao J; Rega N; Zheng G; Liang W; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Throssell K; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark MJ; Heyd JJ; Brothers EN; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Keith TA; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell AP; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Millam JM; Klene M; Adamo C; Cammi R; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Farkas O; Foresman JB; Fox DJ Gaussian 16, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruhn T; Schaumloffel A; Hemberger Y; Bringmann G, SpecDis: quantifying the comparison of calculated and experimental electronic circular dichroism spectra. Chirality 2013, 25, 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willoughby PH; Jansma MJ; Hoye TR, A guide to small-molecule structure assignment through computation of (1H and 13C) NMR chemical shifts. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9 (3), 643–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Menges F. (2023). Spectragryph (1.2.16). http://www.ef-femm2.de/spectragryph/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.