SUMMARY

The HIV-1 Nef accessory factor enhances the viral life cycle in vivo, promotes immune escape of HIV-infected cells, and represents an attractive antiretroviral drug target. However, Nef lacks enzymatic activity and an active site, complicating traditional occupancy-based drug development. Here we describe the development of proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) for the targeted degradation of Nef. Nef-binding compounds, based on an existing hydroxypyrazole core, were coupled to ligands for ubiquitin E3 ligases via flexible linkers. The resulting bivalent PROTACs induced formation of a ternary complex between Nef and the Cereblon E3 ubiquitin ligase thalidomide-binding domain in vitro and triggered Nef degradation in a T cell expression system. Nef-directed PROTACs efficiently rescued Nef-mediated MHC-I and CD4 downregulation in T cells and suppressed HIV-1 replication in donor PBMCs. Targeted degradation is anticipated to reverse all HIV-1 Nef functions and may help restore adaptive immune responses against HIV-1 reservoir cells in vivo.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

While HIV-1 Nef supports viral pathogenesis, pharmacological suppression is difficult because Nef lacks biochemical or enzymatic activity. Emert-Sedlak et al. describe PROTACs that trigger Nef degradation and restore cell-surface immune receptor expression. Targeted degradation may reverse all Nef functions and enhance immune responses to HIV-infected cells.

INTRODUCTION

The nef genes of the primate lentiviruses HIV-1, HIV-2 and SIV encode unique membrane-associated proteins with key roles in viral replication, persistence, and AIDS progression. HIV-1 Nef is expressed at high levels soon after infection and interacts with diverse host cell proteins to enhance viral infectivity and promote immune escape. Some of the best-studied Nef partner proteins include the endocytic adaptor proteins AP-1 and AP-2 which are required for downregulation of MHC-I, CD4 and other viral receptors 1,2 as well as the SERINC5 restriction factor.3-5 Nef also binds and activates non-receptor protein-tyrosine kinases and regulators of the actin cytoskeleton to promote viral transcription and release.6,7

Non-human primate studies provided some of the first evidence that Nef is essential for viral pathogenesis and the development of AIDS. Nef-defective SIV replicates poorly in rhesus macaques, resulting in low viral loads and delayed disease onset.8 These studies mirror reports of individuals infected with Nef-defective HIV-1 in which viral loads remain low in the absence of antiretroviral therapy.9,10 Similar observations have been made in HIV-1 infected humanized immune system mice, in which immunodeficient animals are reconstituted with human CD4+ T cells and other host cell targets for HIV-1.11 In these animals, wild-type HIV-1 infection results in plasma viremia and depletion of CD4+ T cells while Nef-defective HIV-1 replicates poorly and does not cause CD4+ T cell loss.12,13 These animal model and HIV patient data establish a central role for Nef in HIV-1 pathogenesis and support the development of Nef antagonists as new therapeutic approach against HIV/AIDS.14,15

Several studies have reported drug discovery efforts targeting HIV-1 Nef.14,15 One approach involved high-throughput screening of chemical libraries for inhibitors of Nef-dependent activation of a protein kinase partner, the Src-family kinase, Hck.16 This screen identified a unique Nef-binding compound based on a hydroxypyrazole core that inhibited Nef-dependent enhancement of HIV-1 infectivity, replication, and partially reversed Nef-mediated MHC-I downregulation.16,17 Nef is well-known to inhibit cell-surface display of MHC-I in complex with HIV-1 antigenic peptides thereby preventing detection by cytotoxic T lymphocytes.1 In this way, Nef interferes with clearance of the virus from the infected host, and may contribute to establishment and maintenance of the persistent viral reservoir.18,19 The original hydroxypyrazole Nef inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening as well as first-generation analogs 20 based on this structure restored MHC-I to the surface of latently HIV-infected CD4+ T cells in vitro.17 Moreover, when inhibitor-treated cells were co-cultured with autologous CD8+ T cells expanded in the presence of HIV-1 antigenic peptides, the CD8+ T cells became activated and displayed CTL responses against the infected CD4+ target cells.17 This proof-of-concept study strongly suggests that Nef inhibitors may enhance CTL-mediated responses in vivo to help clear the latent viral reservoir.

In more recent work, our team synthesized an extensive series of hydroxypyrazoles that bind tightly to Nef by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and are active against multiple Nef functions in vitro.21 However, Nef lacks an active site, complicating medicinal chemistry optimization due to the lack of correlation between Nef binding affinity in vitro and antiretroviral activity in cell-based systems. In addition, these occupancy-based Nef inhibitors showed relatively modest efficacy in terms of cell-surface MHC-I rescue.21 This observation may reflect a stoichiometric inhibitor requirement to prevent Nef association with the C-terminal tail of MHC-I and the AP-1 endocytic adaptor protein responsible for its downregulation.22 In the present study, we addressed these limitations by repurposing existing Nef-binding compounds as bivalent Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) for the targeted degradation of Nef as illustrated in Figure 1. A major advantage of the PROTAC approach is that it requires only a selective binder of the target protein (Nef in this case) and not a functional inhibitor per se.23,24 We synthesized a library of Nef-directed PROTAC candidates that join existing hydroxypyrazole Nef-binding compounds to ligands for the Cereblon (CRBN) and Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) components of ubiquitin E3 ligases. Using orthogonal cell-based assays for Nef ubiquitylation, degradation, and function, we identified promising Nef-directed PROTACs which target the CRBN E3 ligase pathway. These compounds induce Nef degradation and efficiently reverse Nef-mediated MHC-I and CD4 downregulation. Nef PROTACs also demonstrate potent antiretroviral activity in HIV-infected primary cells, supporting further development for testing in the context of HIV-1 reservoir reduction in vivo. More broadly, these results encourage the development of PROTACs against viral proteins which are intrinsically difficult to target with traditional occupancy-based approaches.25,26

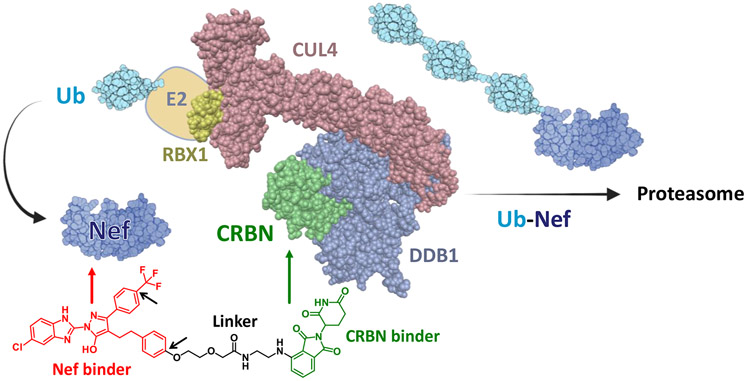

Figure 1. Targeted degradation of HIV-1 Nef by a CRBN-based PROTAC.

The Cereblon (CRBN) ubiquitin E3 ligase complex (left) is a large multiprotein structure composed of RING-box protein 1 (RBX1), Cullin4 (CUL4), DNA damage binding protein 1 (DDB1), CRBN and an E2 subunit conjugated to ubiquitin (Ub). Heterobifunctional Nef PROTACs promote formation of a ternary complex between the HIV-1 Nef protein using existing hydroxypyrazole Nef-binding compounds (red) and the CRBN E3 complex via a CRBN ligand (exemplified by thalidomide, green). Ternary complex formation induces polyubiquitination of Nef and subsequent proteasomal degradation. The Nef PROTAC shown is analog FC-13182; favored positions for linker attachment on the Nef-binding moiety are indicated by the short black arrows. This model was produced using BioRender and structural coordinates for ubiquitin (PDB 1D3Z, NMR), HIV-1 Nef (PDB: 6B72, crystal) and an E3 ligase complex (PDB: 2HYE, crystal).

RESULTS

Synthesis of PROTACs targeting HIV-1 Nef

To create Nef-directed PROTACs, we first attached prototypical PEG linkers to various positions on previously developed Nef-binding compounds.21 Screening of these probe compounds for Nef binding by SPR indicated that the para positions of the two phenyl rings tolerate linker attachment without substantial loss in binding affinity (arrows in Figure 1). We then coupled ligands for ubiquitin E3 ligase components (CRBN or VHL) with linkers of varying lengths and chemistries attached to these two para positions. A total of 102 unique Nef-directed PROTACs were synthesized, with 77 analogs linked to CRBN ligands (thalidomide and lenalidomide) and 25 linked to VHL ligands. Details of the synthetic procedures and analytical characterization of precursors and active analogs are provided in the methods section, and SPR data for the nine probe compounds are summarized in Table S1. NMR and mass spectra for active analogs and select precursors are shown in Data file S1.

Assessment of PROTAC induction of Nef ubiquitylation by NanoBRET Assay

Candidate Nef-directed PROTACs were first screened for induction of Nef ubiquitylation in a cell-based NanoBRET assay (Promega; Figure 2A). This assay consists of two key components: 1) HIV-1 Nef fused via its C-terminus to the small luciferase protein, nano-Luc (Nef-nLuc), and 2) Ubiquitin fused to the self-labeling fluorescent protein known as the Halo-Tag (Ub-Halo).27 The Halo-Tag is a modified bacterial haloalkane dehalogenase that forms a covalent adduct in the presence of a chloroalkane coupled to a fluorogenic acceptor (NanoBRET 618 in this case). Nef-nLuc and Ub-Halo were co-expressed in 293T cells for 18 hours, followed by addition of each PROTAC analog plus the Ub-Halo ligand. Twenty-four hours later, the nano-Luc substrate was added, and the donor (nLuc; 460 nm) and acceptor (HaloTag; 618 nm) signals were recorded. Proximity of Nef-nLuc and Ub-Halo resulting from successful ubiquitylation of Nef results in a BRET signal. Each PROTAC was assayed in quadruplicate, and the resulting data were corrected for background and expressed as 618 nm to 460 nm fluorescence ratios (BRET signal for Ub incorporation normalized to Nef-nLuc levels). BRET ratios were then normalized to the DMSO control wells and used to calculate z-scores based on the normalized ratios for all analogs tested (Figure 2B). All PROTACs were also assayed in quadruplicate in control assays with the Halo-Tag alone. Control assays produced BRET ratios significantly lower than those observed in the presence of Ub-Halo, demonstrating the dependence of the readout on Nef ubiquitylation. Overall, this analysis identified eleven PROTACs that increased Nef ubiquitylation by at least 1.5 standard deviations above the mean (z-score > 1.5). These analogs were advanced to orthogonal assays for induction of Nef degradation and inhibition of Nef function. Analog FC-13887 (z-score = 1.3) was also carried forward due to its activity in the receptor rescue assay described below. Eleven of the 12 active analogs targeted CRBN in this assay, while only a single VHL-based PROTAC showed significant activity (FC-14373). NanoBRET assay data for the twelve active Nef PROTAC analogs, including the negative controls, are summarized in the Supplemental Information, Figure S1.

Figure 2. NanoBRET assay for PROTAC-mediated ubiquitination of HIV-1 Nef.

A) Assay principle. Nef is fused to nano-Luciferase (Nef-nLuc) and co-expressed with a ubiquitin-Halo tag fusion protein (Ub-Halo) in 293T cells. PROTACs promote ligation of Ub-Halo to Nef-nLuc, which is detected by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) to the Halo Tag. This model was produced using BioRender and the crystal coordinates for Nef (PDB: 6B72), NanoLuc (PDB: 5IBO) and HaloTag (PDB: 5Y2X). B) Assessment of candidate Nef PROTACs in the NanoBRET assay. Each compound was assayed in quadruplicate and the average 618 nm to 460 nm fluorescence ratios (BRET signal for Ub incorporation normalized to Nef-nLuc levels) were normalized to the DMSO control and are presented as z-scores ± SD (error bars smaller than data points). PROTACs with z-scores ≥ 1.5 (numbered red points) along with analog FC-13887 were advanced to orthogonal assays for Nef degradation and inhibition of Nef function. z-score = (x - μ)/σ, where x = each individual value, μ = mean value, and σ = the standard deviation.

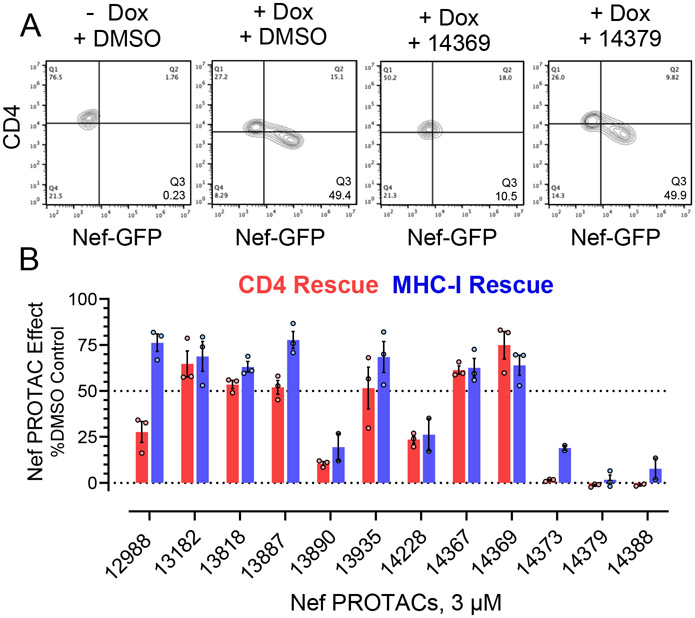

T cell-based assay for PROTAC-induced Nef degradation and cell surface receptor downregulation

For these experiments, the T cell line CEM-T4 was stably transduced with a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible expression vector for a Nef-eGFP (enhanced GFP) fusion protein. In the presence of Dox, Nef-eGFP is expressed leading to downregulation of CD4 and MHC-I from the cell surface which are quantified by flow cytometry (Figure 3A). CEM/Nef-eGFP cells were incubated with each of the active PROTACs from the Nef-Ub NanoBRET screen at a final concentration of 3 μM or DMSO as control, and Nef expression was induced by the addition of Dox. After 24 h, treated cells were analyzed for reversal of cell-surface CD4 and MHC-I downregulation. Six of the 12 Nef PROTACs tested restored cell-surface CD4 expression by more than 50% while seven PROTACs restored cell-surface MHC-I by 50% or more as well (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Nef PROTAC treatment restores cell surface CD4 and MHC-I expression in T cells.

The human T cell line CEM-T4 was engineered to express a Nef-eGFP fusion protein under the control of a doxycycline (Dox) inducible promoter. In the absence of Dox, these cells express endogenous CD4 and MHC-I on their surface; addition of Dox induces Nef-eGFP expression which leads to receptor downregulation. A) Representative flow cytometry result with Nef PROTACs FC-14369 (active) and FC-14379 (inactive). B) Active Nef PROTACs from the NanoBRET ubiquitination assay were screened for cell surface receptor rescue in triplicate. Bar height indicates the mean value ± SE; individual data points are also shown. The structures of the analogs with little to no activity in this assay (FC-13890, FC-14373, FC-14379, FC-14388) are shown in the Supplemental Information, Figure S2.

To determine whether PROTAC-mediated rescue of cell-surface receptor expression was due to degradation of the Nef protein, we also calculated levels of Nef-eGFP in each treated cell population by flow cytometry. PROTACs that restored cell surface receptor expression also induced significant loss of Nef-eGFP in the cell population, with values for percent loss ranging from 15% to more than 50% (Figure 4A). Rescue of cell surface CD4 expression showed a significant linear correlation with Nef-eGFP loss, with the degree of cell surface receptor rescue induced by each PROTAC tracking with the extent of Nef-eGFP reduction (Figure 4B). On the other hand, rescue of cell-surface MHC-I expression showed a non-linear correlation with Nef-eGFP loss, with the activity of the most active compounds plateauing at around 75% of control. The non-linear correlation of MHC-I downregulation with Nef degradation may reflect the use of a pan-HLA antibody for flow cytometry in this experiment. Nef induces selective downregulation of the major Class I HLA isotypes A and B but not C.28 The most active PROTACs may therefore cause nearly complete rescue of HLA-A and HLA-B, with the residual staining cell reflecting surface MHC-I molecules that are not affected by Nef. As an independent measure of PROTAC-mediated loss of Nef expression, we also performed quantitative immunoblot analysis of PROTAC-treated CEM cell lysates using antibodies specific for Nef as well as Actin as a normalizing control (Figure 4C). This experiment confirmed PROTAC-dependent loss of Nef protein expression, with values decreasing from 65% to more than 95% relative to the DMSO-treated control (Figure 4D). These results provide independent evidence that the PROTACs induce Nef degradation, thereby restoring cell-surface expression of receptors essential for immune system recognition of HIV-infected cells.

Figure 4. Assessment of PROTAC-mediated Nef protein loss.

A) Flow cytometry of Nef-eGFP protein loss. CEM/Nef-eGFP cells were treated with doxycycline to induce expression of Nef-eGFP under conditions that result in a moderate level of positive cells by flow cytometry (see Figure 3A). Triplicate cultures of cells were treated with the Nef PROTAC analogs indicated at a final concentration of 3 μM, and 24 h later the percent of cells showing loss of Nef-eGFP protein expression were calculated relative to the DMSO controls and are presented as the mean value ± SE; individual data points are also shown. B) Correlation analysis of cell-surface CD4 rescue vs. Nef-eGFP protein loss (red data points, left) and MHC-I rescue vs. Nef-eGFP protein loss (blue data points, right). CD4 rescue was best-fit by linear regression, while MHC-I rescue showed a plateau effect. C) Immunoblot analysis. Cells expressing Nef-eGFP were treated as in part A with the eight active PROTACs, and lysates were prepared 48 h later for immunoblot analysis with Nef and Actin antibodies. A representative blot is shown. D) Immunoblot analysis was performed in duplicate, and band intensities were quantified by LI-COR infrared imaging and used to calculate Nef to Actin protein expression ratios. The bar graph shows the mean value for each ratio along with the individual values. The structures of the analogs with little to no activity in this assay (FC-13890, FC-14373, FC-14379, FC-14388) are shown in the Supplemental Information, Figure S2.

Structures of the eight most active Nef PROTACs are presented in Figure 5. Six analogs use thalidomide as the CRBN-targeting moiety while the other two are based on lenalidomide. In five analogs, the CRBN-recruiter is attached to the phenyl group of the Nef ligand analog via the para position (position ‘x’) while three used the para position of the phenylethyl group (position ‘y’). A wide range of linker lengths was tolerated, ranging from just three atoms (FC-14367) to more than 20 (FC-14228). These observations suggest multiple starting points for the synthesis of analogs with optimized physicochemical and pharmacological properties for further development. The structures of the analogs with little to no activity in the receptor downregulation and degradation assays (FC-13890, FC-14373, FC-14379, FC-14388) are shown in the Supplemental Information, Figure S2.

Figure 5. Structures of active Nef PROTACs.

The Nef-targeting moiety (red, upper left) provides two positions on the phenyl rings for linker attachment (x and y). CRBN ligands included analogs of thalidomide (green, center) and lenalidomide (blue, right) that were attached to the isoindoline ring at positions 4 and 5. Linker compositions are shown below adjacent to each analog number. The complete structure of FC-14367 is also provided.

The most active Nef PROTAC, FC-14369, was also tested in a concentration-response experiment to estimate the DC50 value in the immunoblot assay (PROTAC concentration that produces 50% degradation of the target protein; Figure S3). Following 48-hour PROTAC treatment of Dox-induced CEM/Nef-eGFP cells, the Nef to actin band intensity ratios were calculated from lysate immunoblots and non-linear regression analysis yielded a DC50 value of 160 nM. The structurally related inactive analog, FC-14368, served as a negative control. Cell viability assays performed in parallel yielded a CC50 value of approximately 3.0 μM, indicating that targeted degradation of Nef occurs without cytotoxicity.

PROTACs based on thalidomide and related CRBN-targeting compounds are known to induce degradation of neo-substrates, including IKZF1 (Ikaros) and related transcription factors.29,30 To explore this possibility for Nef degraders, we tested the effect of the most active PROTAC, FC-14369, on the protein level of IKZF1 in the CEM/Nef-eGFP T cell model following induction of Nef expression with doxycycline. We found that FC-14369 treatment reduced the expression of IKZF1, which is likely due to the thalidomide component of the PROTAC. Treatment with a structurally similar analog, FC-14368, which does not induce Nef degradation, also resulted in reduction of IZKF1, supporting this idea (Figure S3). Interestingly, IKZF1 degradation by thalidomide analogs has been linked to HIV latency reversal,31 which may represent an unanticipated benefit of CRBN-targeted degraders of Nef.

We also compared four previous occupancy-based Nef inhibitors with active PROTAC FC-14369 in the inducible CEM/Nef-GFP T cell system under identical experimental conditions. Nef-eGFP expression was induced with Dox as before, followed by treatment with each inhibitor at 3.0 μM. FC-14369 rescued cell surface expression of both CD4 and MHC-I by about 70%, with a parallel loss in Nef expression, consistent with results presented above. The occupancy-based inhibitors (JZ-96, FC-7943, FC-7976, FC-8517) restored cell surface MHC-I expression by 48-60% but were less effective against CD4 with rescue values ranging from 18% to 37% (Figure S4). Interestingly, these Nef-binding compounds also induced partial loss of Nef-eGFP expression that tracked closely with the extent of CD4 rescue. Binding of the hydroxypyrazole moiety may contribute to Nef protein loss by altering the conformation of Nef to induce an unfolded protein response or by acting as a molecular glue.

Assessment of direct PROTAC binding to Nef and CRBN by SPR

To confirm interaction of each bivalent PROTAC analog with both Nef and CRBN, we used our established SPR assay for small molecule-protein interactions.21 Eight recombinant Nef proteins representative of multiple M-group HIV-1 variants, SIV Nef mac239, and the thalidomide-binding domain of CRBN were expressed in bacteria and purified to homogeneity. The recombinant proteins were immobilized on a carboxymethyl dextran hydrogel biosensor chip, and solubilized PROTACs were injected over a range of concentrations in triplicate. Following a dissociation phase, the resulting sensorgrams were fitted with a 1:1 Langmuir binding model and KD values were calculated from the rate constants and the relationship, KD = kd/ka. Representative SPR sensorgrams for active Nef PROTACs FC-12988 and FC-13182 are shown in Figure 6A to illustrate differences in the binding kinetics. While both PROTACs bound to the CRBN thalidomide-binding domain to a similar extent, FC-12988 associated more slowly than FC-13182 and showed a comparatively slow dissociation phase. The reverse was true with HIV-1 Nef (NL4-3 variant), in which FC-12988 showed more rapid association and release compared to FC-13182. These kinetic differences may in part reflect the alternative points of linker attachment on the Nef-binding moiety. The shape of the PROTAC sensorgrams with HIV-1 Nef closely resemble those reported previously for structurally related Nef-binding components alone.21 However, the extent of binding (RU value) was higher at each PROTAC concentration, which likely reflects the higher formula weight of the PROTACs. Regardless, both compounds effectively induced Nef degradation and restored CD4 and MHC-I expression to the surface of T cells.

Figure 6. Representative SPR sensorgrams for Nef PROTACs.

The thalidomide-binding domain of Cereblon (CRBN-TBD) and full-length Nef (NL4-3 variant) were expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity. A) Each protein was immobilized on one channel of a carboxymethyl dextran biosensor chip, and the two Nef PROTAC analogs FC-12988 and FC-13182 (structures at top; Nef-binding moiety in red, CRBN-binding ligands thalidomide and lenalidomide are shown in green and blue, respectively) were injected over the range of concentrations shown in the upper left sensorgram. Protein-ligand interaction was followed for 90 s, followed by a 180 s dissociation phase. The resulting data were fit to a 1:1 Langmuir binding model, and KD values were calculated from the resulting association and dissociation rate constants (KD values are summarized in Table S2). Each concentration was tested in triplicate, and individual traces are shown with the data shown in color and the fitted curves superimposed in black. RU, SPR response units. Arrows indicate the point of injection and the switch to wash buffer for dissociation. B) Comparison of SPR profiles for interaction of active PROTAC analog FC-14369 with NefNL4-3 vs. inactive analog FC-13906. The inactive analog dissociates rapidly from Nef while the active analog remains bound. Additional examples are provided in Figure S5.

The kinetics of PROTAC binding to Nef by SPR provides possible insight regarding active vs. inactive analogs in terms of Nef ubiquitylation as observed in the NanoBRET assay. Inactive PROTACs often show rapid dissociation from Nef compared to active analogs despite similar linker length and point of attachment to the Nef-binding moiety. For example, active PROTAC FC-14369 shows the delayed dissociation characteristic of other active analogs (Figure 6B). On the other hand, inactive analog FC-13906, which is identical to FC-14369 except for a single carbon for oxygen substitution in the linker, shows very rapid dissociation from Nef, yielding a KD value in the 40 μM range as opposed to 6.5 nM for FC-14369 (Figures 6B and S5). Similarly, active PROTAC FC-13887 differs from its inactive analog, FC-14087, by replacement of the nitrogen atom coupling the linker to thalidomide with oxygen. Again, the result is rapid dissociation from Nef and a >100-fold increase in the KD value. Four additional paired examples are provided in Figure S5 that demonstrate similar findings. Altogether, these comparisons demonstrate that deceptively subtle changes in linker length or chemistry can have a major impact on Nef interaction kinetics in vitro and may in turn have predictive value for induction of stable ternary complexes and Nef ubiquitylation in cells.

The eight most active PROTACs from the CEM T cell assay bound to all Nef variants tested as well as the CRBN thalidomide-binding domain (Table S2), suggesting that PROTACs based on the hydroxypyrazole Nef-targeting moiety will be widely active against M-group HIV-1 variants responsible for the pandemic. Overall, of the 72 interactions tested with diverse Nef proteins (eight PROTACs vs. nine Nef variants), 57 (79%) yielded KD values in the nM range. All eight PROTACs interacted with SIV Nefmac239 in the nanomolar range, suggesting that these analogs may enable exploration of the effects of targeted Nef degradation in SIV/Rhesus macaque models of HIV-1 latency (see Discussion). The F1 variant of Nef showed the lowest overall binding affinity, with just two of eight analogs yielding KD values below 1 μM. That said, 2 analogs (FC-14367 and FC-14369) bound to all eight M-group HIV-1 Nef variants as well as SIV Nef with KD values below 1 μM. All analogs bound to the thalidomide binding domain of Cereblon with KD values in the nM range as well. While these results suggest that PROTAC analogs can be designed to meet the challenges of HIV-1 Nef diversity, the issue of acquired drug resistance will require future investigation. The PROTAC approach may be more effective in this regard, given the event-based (as opposed to occupancy-based) mechanism of action and reduced requirement for on-target potency. Control SPR data show that the thalidomide analogs used for PROTAC synthesis bind to HIV-1 and SIV Nef proteins with very low potency (10-70 μM range; Table S3).

Active Nef PROTACs stabilize ternary Nef-CRBN complexes in vitro

Targeted protein degradation requires PROTAC-mediated formation of a ternary complex between the protein target, the bivalent PROTAC ligand, and the E3 ligase. To model this mechanism in vitro, we incubated recombinant Nef (NL4-3 variant) and the CRBN thalidomide-binding domain in the presence and absence of the active Nef PROTAC analogs, FC-12988, FC-13818, and FC-13887 (Figure S6). In the absence of the PROTAC, Nef and CRBN co-eluted from a size-exclusion column; note that the retention volumes of the individual proteins are the same, so the mixture elutes as a single peak (Figure S6A). When preincubated in the presence of the PROTACs, however, new peaks of smaller retention volumes (higher molecular weights) were observed, and the height of these peaks increased in proportion to the concentration of the PROTAC added to the mixture (Figure S6B-D). These results provide evidence that active Nef PROTACs induce ternary complexes of Nef with CRBN and are consistent with the results from the NanoBRET and CEM-T4 assays.

PROTACs block Nef-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 replication in donor PBMCs

HIV-1 Nef is well known to enhance viral replication in donor PBMCs in vitro and is essential for high viral loads in vivo (see Introduction). Our previous studies have shown that the hydroxypyrazole Nef-binding compounds used to create the PROTACs possess significant antiretroviral activity.21 To determine whether antiretroviral activity is retained by the Nef PROTACs, we tested the most active analogs in HIV-infected PBMCs from normal donors. PBMCs were infected with wild-type and Nef-defective HIV-1NL4-3 under conditions where the presence of Nef enhanced replication by 3.3-fold consistent with prior work (Figure 7A).21 Cultures infected with wild-type HIV-1 were incubated with each PROTAC at a final concentration of 1 μM, and the extent of replication was assessed using a p24 Gag AlphaLISA assay 4 days later. All eight PROTACs showed antiviral activity, with six of eight analogs completely suppressing Nef-dependent enhancement of viral replication (Figure 7A). To assess cytotoxicity, uninfected PBMCs were incubated with each Nef PROTAC at 1 μM for 4 days, followed by assessment of viability with the CellTiter-Blue Assay. PBMCs treated with seven of the eight PROTACs showed viability of 90% or more compared to the DMSO control (Figure 7B). The one exception was FC-13818, which reduced viability by 20%; this observation may partially explain why this analog reduced HIV-1 replication below the level of the ΔNef mutant.

Figure 7. PROTACs inhibit Nef-dependent enhancement of HIV-1 replication in primary cells.

A) Donor PBMCs were infected with wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 (DMSO control), a Nef-defective mutant (ΔNef), or wild-type virus in the presence of the Nef PROTACs shown at a final concentration of 1 μM. Input virus was 2,500 pg HIV p24 Gag per well. Replication was assayed by p24 Gag AlphaLISA 4 days later. Six independent determinations were assayed for each condition, and the highest and lowest p24 values were removed. Each bar indicates the mean ± SE of the remaining values with the individual data points shown. The dotted line indicates the mean value for the ΔNef control. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test between the DMSO control and ΔNef as well as each PROTAC treatment group; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. B) Viability of uninfected PBMCs was determined with each PROTAC at 1 μM after 4 days using the Cell Titer Blue assay (n = 6 wells/condition). The dotted line indicates 100% viability based on the DMSO control.

To explore the mechanism of viral suppression, we also tested the effect of one of the most active Nef PROTACs, FC-14369, in an HIV-1 infectivity assay. This assay is based on the TZM-bl reporter cell line, in which the HIV-1 LTR drives expression of a luciferase reporter gene32 in a manner dependent on Nef expression.23 TZM-bl cells were infected with HIV-1NL4-3 in presence of a range of FC-14369 concentrations, and infectivity was assessed as luciferase activity 48 hours later. FC-14369 inhibited HIV-1 infectivity in this system with an IC50 value of about 250 nM without cytotoxicity (Figure S7). The structurally related analog FC-14368, which does not induce Nef ubiquitylation, was inactive in this assay. Suppression of infectivity by targeting Nef may reverse Nef-dependent downregulation of the SERINC5 restriction factor from the cell membrane, thereby permitting incorporation into budding virions to prevent spreading infection.33 Downregulation of SERINC5 by Nef occurs via an AP-2-dependent endolysosomal pathway like CD4, which is also sensitive to Nef PROTACs as shown above.34

DISCUSSION

In this report, we present the synthesis and characterization of CRBN-based PROTACs that induce HIV-1 Nef proteolytic degradation via ubiquitination. Targeted degradation of Nef resulted in robust recovery of cell-surface MHC-I and CD4 expression in a T cell system while potently suppressing Nef-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 replication in primary cells. Nef is well known to interact with diverse host cell proteins to enhance the viral life cycle, promote immune escape, and support viral persistence.1,6,19 Nef lacks an active site and uses multiple structural motifs to recruit cellular signaling partners, complicating traditional occupancy-based antiretroviral drug development. The PROTAC approach detailed here may circumvent this issue, as targeted degradation is likely to antagonize all Nef functions while limiting side effects from non-specific activities.

The active Nef PROTACs share a Nef-targeting moiety based on a hydroxypyrazole core joined to a benzimidazole substituent (Figure 5). Previous studies of these Nef antagonists showed low nanomolar inhibition of HIV-1 replication in primary cells,21 an effect likely attributed to interference with Nef-activated kinases linked to viral transcription.6 Our findings that these same Nef antagonists, in the context of the PROTACs described here, induce degradation of Nef in T cells provides strong evidence for their direct interaction with Nef in a cellular context. This observation is also consistent with the ability of these PROTAC analogs to bind directly to recombinant Nef by SPR and to induce formation of ternary complexes with the CRBN thalidomide-binding domain in vitro (Figures 6 and 7). Importantly, Nef PROTACs based on the hydroxypyrazole targeting moiety bound to a diverse panel of HIV-1 Nef variants as well as SIV Nef (Table S2), suggesting that they will be broadly active against multiple HIV-1 strains through a shared structure feature within Nef. Alignment of the folded cores of HIV-1 and SIV Nef proteins previously determined by X-ray crystallography reveals strong structural homology in this region, along with multiple exposed lysine residues for ubiquitin attachment. This observation suggests that some of the PROTACs described here may be suitable for testing in non-human primate models of SIV latency.

Using a cell based NanoBRET assay, we compared the ability of ~100 PROTAC analogs to induce Nef ubiquitylation. Eight of the top 12 analogs identified in this screen were subsequently shown to induce Nef degradation in T cells and displayed antiretroviral activity in PBMCs. The most active analogs used thalidomide or lenalidomide as the E3 ligase targeting moiety, despite the presence of VHL ligands in 25 of the analogs used in the screen. The preference for CRBN-based degradation may result from better spatial compatibility between CRBN and Nef within the E3 ligase ternary complex. Interestingly, the NanoBRET assay also identified several analogs with z-scores significantly lower than zero, suggesting that some PROTACs may protect Nef from ubiquitylation. Ubiquitylation of both HIV-1 and SIV Nef proteins has been previously reported,35 raising the possibility that some PROTACs may assemble non-productive ternary complexes that interfere with endogenous ubiquitylation and turnover. The NanoBRET assay provided an expedient way of initially ranking the compounds for their ability to enhance Nef ubiquitylation, thereby identifying the most promising analogs for further testing in the more labor-intensive flow cytometry and HIV replication assays. However, this assay does not distinguish between mono- vs. polyubiquitylation required for proteosomal targeting, nor does it identify specific lysine sites for extension of the polyubiquitin chain. Differences in these factors may explain why some analogs that scored as positive in the NanoBRET assay were subsequently found to be inactive in the T cell assay.

All eight active Nef PROTACs reported here used thalidomide analogs to recruit the Cereblon E3 ligase to the ternary complex. Multiple PROTACs are in clinical trials for cancer therapy which use thalidomide analogs as the E3 targeting moiety, despite the known teratogenic properties of thalidomide as a stand-alone drug.36 Newer thalidomide analogs and linker designs are being developed to reduce the targeting of neosubstrates.29,37,38 These encouraging results suggest that Nef-directed PROTACs can be synthesized to remove the potential for thalidomide-associated toxicities.

Targeted degradation of Nef may reduce HIV-1 pathogenesis and help to shrink or eliminate persistent viral reservoirs. HIV-1 gene expression, including Nef, persists in people living with HIV even in the presence of suppressive ART.39-41 Continued production and release of Nef and other HIV-encoded proteins from latent reservoir cells, including cells with defective proviruses,42 may contribute to HIV-associated co-morbidities involving the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Furthermore, a significant correlation has shown between the ability of patient-derived Nef alleles to downregulate MHC-I in vitro and reservoir size in vivo, with enhanced MHC-I downregulation activity associated with larger viral reservoirs.18 Our results show Nef PROTACs efficiently restore cell-surface CD4 and MHC-I expression in T cells (Figures 3 and 4), suggesting that targeted degradation is likely to reverse AP-1 and AP-2 mediated endocytosis of all cell surface receptors and restriction factors mediated by Nef. Future studies will explore the effect of Nef PROTACs on overall antiretroviral immune responses using cell-based and in vivo models. Furthermore, Nef PROTACs inhibit Nef-dependent enhancement of HIV-1 replication in primary cells with limited cytotoxicity (Figure 7), supporting the therapeutic potential of these Nef PROTACs.

Duette et al. recently reported that Nef expression is required for persistence of intact HIV-1 proviruses in effector memory T cells, a predominant reservoir cell type.19 Cell-surface expression of the immune checkpoint receptor, PD-1, is also associated with persistence of viral reservoirs in vitro and in vivo, including in the SIV/macaque model of AIDS. Keytruda (pembrolizumab) and other immune checkpoint blocking antibodies have been shown to induce latency reversal in people living with HIV43,44 and in SIV-infected non-human primates 45 in the presence of suppressive ART. Importantly, Muthumani et al. have shown that Nef is both sufficient and necessary for HIV-induced cell-surface expression of PD-1.46 Taken together, these findings support a role for Nef in establishment and maintenance of the latent HIV-1 reservoir, through mechanisms involving immune escape through MHC-I downregulation, upregulation of PD-1 and possibly other immune checkpoint molecules. Targeted degradation using PROTACs is anticipated to reverse all Nef functions, potentially promoting latency reversal, restoration of adaptive immunity, suppression of viral replication and ultimately reservoir reduction.

Limitations of the Study

Several lines of evidence presented here support PROTAC-mediated degradation of HIV-1 Nef in cells through a mechanism that likely involves polyubiquitylation and proteosomal degradation. The NanoBRET assay demonstrated enhanced ubiquitylation of Nef following PROTAC treatment, Nef expression levels were significantly reduced in PROTAC-treated T cells, and active PROTACs exhibited sustained binding to purified Nef and Cereblon proteins by SPR and formed ternary complexes in vitro. However, more work is required to explore the effect of PROTAC treatment on the kinetics of Nef protein turnover in the context of HIV-infected primary cells as well as reversal of Nef-mediated phenotypic effects. While several Nef PROTACs show complete inhibition of Nef-mediated enhancement of HIV-1 replication in PBMCs (Figure 7), demonstration of Nef protein loss and concomitant cell-surface receptor rescue in this context is an important goal for future work.

SIGNIFICANCE

Here we describe the synthesis and evaluation of heterobifunctional PROTAC molecules that induce the targeted degradation of the HIV-1 Nef virulence factor. Nef plays essential roles in the pathogenesis and persistence of HIV-1, and pharmacological suppression of Nef function not only inhibits viral replication but has the potential to restore the immune response to eliminate viral reservoirs. The PROTACs described here are based on previous Nef-binding compounds which display antiretroviral activity and trigger adaptive immune responses to HIV+ CD4 T cells in vitro. However, medicinal chemistry advancement of ‘occupancy based’ Nef inhibitors has been difficult because Nef lacks a singular enzymatic or biochemical activity. Instead, Nef functions by interacting with multiple host cell signaling partners through diverse structural motifs to boost viral replication and allow infected cells to hide from the immune system. The targeted degraders described here effectively block these diverse Nef functions, including downregulation of CD4 and MHC-I, which involve distinct Nef structural motifs and endolysosomal pathways. Nef PROTACs also demonstrated potent antiretroviral activity in HIV-infected primary cells. These molecules may have clinical utility in restoring immune recognition of viral reservoir cells and preventing viral rebound following traditional antiretroviral drug withdrawal. While pharmaceutical interest in PROTACs has exploded in the anticancer drug development space,36 fewer examples exist for infectious diseases,26 especially for viral accessory proteins like Nef which are generally considered undruggable. Targeted degradation of the HIV-1 Nef protein demonstrates the broader potential of antimicrobials based on PROTACs, expanding the landscape of microbial proteins for therapeutic exploitation.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Thomas E. Smithgall (tsmithga@pitt.edu).

Materials availability

PROTAC molecules described in this study will be provided upon request with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement and subject to availability.

Other unique reagents including the CEM/Nef-eGFP cell line and recombinant Nef proteins will be provided upon request with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement and subject to availability.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Recombinant DNA and protein expression

Routine subcloning and recombinant protein expression were performed in E. coli strains DH5α and Rosetta 2 (DE3) pLysS, respectively.

Human cell lines and primary cells

NanoBRET assays were performed in 293T cells which are of human female embryonic kidney origin. HIV-1 infectivity assays were performed in the TZM-bl reporter cell line which was generated from the HeLa human female cervical cancer cell line. Both cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The inducible Nef expression system was created in the human female lymphoblastoid cell line, CEM-T4. These cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Cell lines were obtained from the ATCC or the HIV Reagent Program and are authenticated by the provider. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purchased (Miltenyi) and originally obtained from an anonymous donor (female; 52 years).

HIV-1 strain

Viral infectivity and replication assays were performed with the B-subtype HIV-1 strain, NL4-3.

METHOD DETAILS

Synthetic chemistry: General experimental methods

Starting reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and were used without further purification unless otherwise specified. Normal phase column chromatography was carried out in the indicated solvent system using pre-packed silica gel cartridges on the Isco CombiFlash Companion® or Isco CombiFlash Rf® system. Preparative reverse phase HPLC (“Prep HPLC”) was performed on a Phenomenex LUNA 5 μm C18(2) 100 Å 150 x 21.2 mm column or a Waters SunFire® Prep C18 OBD™ 10 μm 150 x 30 mm column with a 12 min mobile phase gradient of 10% acetonitrile/water to 90% acetonitrile/water with 0.1% TFA as buffer using 214 and 254 nm as detection wavelengths. Injection and fraction collection were performed with a Gilson 215 liquid handling apparatus using Unipoint software.

LRMS data were determined with a Waters Alliance 2695 HPLC/MS using a Phenomenex Luna 3 μm C18(2) 100 Å, 75 x 4.6 mm column with a 2996 diode array detector operating from 210–400 nm; the solvent system was 5–95% acetonitrile in water (with 0.1% TFA) over nine minutes using a linear gradient, and retention times (tR) are in minutes. Mass spectrometry was performed on a Waters ZQ instrument using electrospray in positive ion mode. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained at the University of Notre Dame Mass Spectrometry & Proteomics Facility on a Bruker Daltonics microTOF II instrument using electrospray ionization in positive mode.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 spectrometer operating at 299.985 MHz for 1H NMR, at 282.243 MHz for 19F NMR and at 75.439 MHz for 13C NMR. Spectra were taken in the indicated solvent at ambient temperature, and the chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm, δ) relative to the lock of the solvent used. Resonance patterns are recorded with the following notations: br (broad), s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), and m (multiplet).

Synthesis of CRBN binding intermediates

2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]oxy}acetic acid (3, CAS Registry number (Regno): 2229976-16-1)

This compound was prepared by a modification of the procedure described in US patent application 2019/0336503.

tert-butyl 2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]oxy}acetate (2, CAS Regno: 2229976-15-0).

To a stirred solution of 3-(4-hydroxy-1-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-2-yl)piperidine-2,6-di-one (1, CAS Regno: 1061604-41-8, 926 mg, 3.6 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (0.64 mL, 3.6 mmol) in dry DMF (10 mL) was added t-butyl bromoacetate (0.5 mL, 3.4 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 2 d and purified directly by prep HPLC to give 2 as an oil. Yield: 380 mg (28%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.52 - 7.39 (m, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.21 - 7.08 (m, 1H), 5.10 (dd, J = 5.1, 13.0 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 4.48 - 4.13 (m, 2H), 3.03 - 2.75 (m, 1H), 2.63-2.33 (m, 2H), 2.14 - 1.88 (m, 1H), 1.40 (s, 9H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 3.90 min, m/z: 375 [M + H]+, 319 [M – C4H8 + H]+.

2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]oxy}acetic acid (3, CAS Regno: 2229976-16-1).

A solution of 2 (380 mg, 1.0 mmol) in 2:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (9 mL) was stirred at rt for 1 d and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from aq MeCN to give 3 as an off-white solid. Yield: 289 mg (90%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.52 – 7.40 (m, 1H), 7.32 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 5.10 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (s, 2H), 4.45 – 4.15 (m, 2H), 3.02 – 2.78 (m, 1H), 2.64-2.20 (m, 2H), 2.10 – 1.86 (m, 1H).

4-[(2-Aminoethyl)amino]-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (6, CAS Regno: 1957235-66-3)

This compound was prepared by a modification of the procedure described in Ishoey et al.47

tert-Butyl N-(2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]amino}ethyl)carbamate (5, CAS Regno: 1957235-57-2).

A mixture of 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4-fluoro-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (4, CAS Regno: 835616-60-9, 1.75 g, 6.3 mmol), tert-butyl N-(2-aminoethyl)carbamate (CAS Regno: 57260-73-8, 1.06 g, 6.6 mmol), i-Pr2NEt (2.3 mL, 12.7 mmol) and dry DMF (30 mL) was stirred in a 90°C oil bath for 2 d. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (150 mL) and washed with water (2 x 50 mL) and brine (50 mL). The combined aqueous washes were back extracted with EtOAc (50 mL). The combined EtOAc layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to leave a black oil (4.11 g). Prep HPLC gave 5 as a yellow solid. Yield: 850 mg (32%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.64 – 7.42 (m, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.04 – 6.93 (m, 2H), 6.68 (br s, 1H), 5.01 (dd, J = 5.5, 12.5 Hz, 1H), 3.38-3.21 (m, 2H), 3.14-3.01 (m, 2H), 2.92 – 2.68 (m, 1H), 2.59-2.32 (m, 2H), 2.11 – 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.32 (s, 9H); LRMS tR 3.98 min, m/z: 439 [M+Na]+, 417 [M+H]+, 317 [M-C4H8CO2+H]+.

4-[(2-Aminoethyl)amino]-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (6, CAS Regno: 1957235-66-3).

A solution of 5 (850 mg, 2.0 mmol) in 2:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (30 mL) was stirred at rt for 0.5 h.

The mixture was concentrated, and the residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give 6 as its HCl salt. Yield: 745 mg (quant); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.62 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 5.16 - 5.01 (m, 1H), 3.68 (s, 2H), 3.26 - 3.10 (m, 2H), 2.95 - 2.59 (m, 3H), 2.23 - 2.00 (m, 1H). LRMS (ESI+) tR 2.25 min, m/z: 317 [M+H]+.

4-[(2-aminoethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (8, CAS Regno: 2154342-43-3)

This compound was prepared by a modification of the procedure described in Ishoey et al.47

tert-butyl N-(2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl](methyl)amino}ethyl)carbamate (7, CAS Regno: 2154342-12-6)

A mixture of 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4-fluoro-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (4, CAS Regno: 835616-60-9, 750 mg, 2.7 mmol), tert-butyl N-[2-(methylamino)ethyl]carbamate (500 mg, 2.9 mmol), i-Pr2NEt (1 mL, 5.5 mmol) and DMF (10 mL) was stirred at 70 °C for 20 h. The mixture was cooled to rt, diluted with EtOAc (90 mL), washed with water (2 x 20 mL) and brine (20 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a yellow oil (1.58 g). Prep HPLC gave 7 as a yellow solid. Yield: 480 mg (41%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.82 - 7.67 (m, 1H), 7.46 - 7.30 (m, 2H), 6.94 - 6.79 (m, 1H), 5.32 - 5.17 (m, 1H), 3.81 - 3.57 (m, 2H), 3.35 - 3.22 (m, 2H), 3.12 - 2.93 (m, 1H), 2.81 - 2.60 (m, 2H), 2.24 - 2.02 (m, 1H), 1.42 (s, 9H).

4-[(2-aminoethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (8, CAS Regno: 2154342-43-3).

A solution of 7 (480 mg, 1.1 mmol) in 2:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (30 mL) was stirred at rt for 0.5 h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from a mixture of MeCN and 5% aq HCl to give the HCl salt of 8 as a yellow solid. Yield: 419 mg (quant); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.80 - 7.66 (m, 1H), 7.53 - 7.35 (m, 2H), 5.20-5.10 (m, 1H), 3.65-3.57 (m, 2H), 3.41 - 3.30 (m, 2H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 2.94 - 2.58 (m, 3H), 2.21 - 2.06 (m, 1H).

4-({2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl}amino)-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (11, CAS Regno: 2093416-32-9)

This compound was prepared by a modification of the procedure described in Ishoey et al.47

tert-butyl N-{2-[2-(2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]amino}ethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl}carbamate (10, CAS Regno: 2097509-40-3).

A solution of 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4-fluoro-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (4, CAS Regno: 835616-60-9, 420 mg, 1.5 mmol), tert-butyl N-{2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl}carbamate (9, CAS Regno: 153086-78-3, 396 mg, 1.6 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (0.55 mL, 3.0 mmol) in DMF (10 mL) was stirred at 70 °C for 4 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (90 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (2 x 15 mL) and brine (15 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a green oil (910 mg) which was purified by prep HPLC to give 10 as a yellow solid. Yield: 230 mg (30%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.62 - 7.49 (m, 1H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.81 - 6.67 (m, 1H), 6.65 - 6.55 (m, 1H), 5.10 - 4.98 (m, 1H), 3.67 - 3.41 (m, 10H), 3.39-3.32 (m, 2H), 3.11 - 2.97 (m, 2H), 2.95 - 2.74 (m, 1H), 2.65 - 2.36 (m, 2H), 2.08 - 1.92 (m, 1H), 1.34 (s, 9H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 4.13 min, m/z: 505 [M+H]+, 405 [M-C4H8CO2+H]+.

4-({2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl}amino)-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (11, CAS Regno: 2093416-32-9).

A solution of 10 (230 mg, 0.46 mmol) in 3:2 CH2Cl2/TFA (5 mL) was stirred at rt for 0.5 h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from a mixture of MeCN and 5% aq HCl to give the HCl salt of 11 as a greenish yellow solid. Yield: 114 mg (57%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.06 (br s, 2H), 7.65 - 7.50 (m, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.00 - 5.21 (m, 2H), 5.12-5.00 (m, 1H), 3.70 - 3.52 (m, 8H), 3.50-3.40 (m, 2H), 2.99-2.80 (m, 2H), 2.66 - 2.37 (m, 1H), 2.10 - 1.90 (m, 1H).

2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-5-{4-[(piperidin-4-yl)methyl]piperazin-1-yl}-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (17, CAS Regno: 2229725-28-2)

tert-butyl 4-[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-5-yl]piperazine-1-carboxylate (14, CAS Regno: 2222114-64-7).

To a stirred solution of 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-5-fluoro-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (12, CAS Regno: 835616-61-0, 800 mg, 2.9 mmol) and tert-butyl piperazine-1-carboxylate (13, CAS Regno: 57260-71-6, 560 mg, 3.5 mmol) in DMSO (10 mL) was added i-Pr2NEt (1.1 mL, 6.1 mmol). The mixture was stirred at 90 °C for 3 h, cooled to rt and purified by prep HPLC to give 14 as a yellow solid. Yield: 410 mg (32%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.74 - 7.64 (m, 1H), 7.33 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 5.06 (dd, J = 5.5, 12.5 Hz, 1H), 3.45 (s, 8H), 2.99 - 2.75 (m, 1H), 2.63 - 2.51 (m, 2H), 2.08 - 1.89 (m, 1H), 1.41 (s, 9H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 4.28 min, m/z: 387[M-C4H8 + H]+, 343 [M-C4H8CO2+H]+.

2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-5-(piperazin-1-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione. (15, CAS Regno: 2154342-61-5).

To a stirred solution of 14 (410 mg, 0.93 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (6 mL) was added TFA (2 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for 1h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give the bis HCl salt of 15 as a yellow solid. Yield: 450 mg, (quantitative); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 2.23 min, m/z: 343 [M + H]+.

tert-butyl 4-({4-[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-5-yl]piperazin-1-yl}methyl) piperidine-1-carboxylate (16).

To a stirred mixture of the bis HCl salt of 15 (450 mg, 1.1 mmol), tert-butyl 4-formylpiperidine-1-carboxylate (460 mg, 2.1 mmol), NaOAc (270 mg, 3.3 mmol) and dry DCE (10 mL) was added MgSO4 (150 mg). The mixture was stirred under N2 for 0.5 h and NaBH(OAc)3 (689 mg, 3.3 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred overnight at rt, diluted with water (10 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure to remove DCE. The residue was diluted with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (20 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (2 x 80 mL). The combined EtOAc layer was concentrated to leave a yellow solid (680 mg) which was HPLC purified to give the TFA salt of 16. Yield: 320 mg (45%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.81 - 7.71 (m, 1H), 7.54 - 7.45 (m, 1H), 7.41 - 7.24 (m, 1H), 5.17 - 4.98 (m, 1H), 4.31 - 4.09 (m, 2H), 4.03 - 3.80 (m, 2H), 3.65-3.05 (m, 10H), 2.95-2.40 (m, 4H), 2.10 - 1.89 (m, 2H), 1.82 - 1.62 (m, 2H), 1.38 (s, 9H), 1.17 - 0.93 (m, 1H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 3.25 min, m/z: 540 [M+H]+, 484 [M-C4H8+H]+, 440[M-C4H8CO2+H]+.

2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-5-{4-[(piperidin-4-yl)methyl]piperazin-1-yl}-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindole-1,3-dione (17, CAS Regno: 2229725-28-2).

A solution of the TFA salt of 16 (320 mg, 0.49 mmol) in 3:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (6 mL) was stirred at rt for 1h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give the bis HCl salt of 17 as a solid. Yield: 306 mg (quant); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 2.16 min, m/z: 440 [M+H]+.

Synthesis of Nef binding intermediates

2-(4-{2-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl}phenoxy)acetic acid (25)

tert-Butyl 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)phenoxy]acetate (19).

To a stirred mixture 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)phenol (18, CAS Regno: 501-94-0, 4.97 g, 36.0 mmol), K2CO3 (5.47 g, 39.6 mmol) and DMF (50 mL) was added t-butyl bromoacetate (CAS Regno: 5292-43-3, 5.3 mL, 36.0 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt for 1 d, diluted with water (150 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (4 x 50 mL). The combined EtOAc layer was washed with water (25 mL) and brine (25 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a viscous oil (13.20 g) which was purified by chromatography on an 80 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-70% EtOAc in hexanes gradient to provide 19 as a colorless oil. Yield: 7.28 g (80%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.13 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.49 (s, 2H), 3.89 - 3.69 (m, 2H), 2.87 - 2.65 (m, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H).

tert-butyl 2-{4-[2-(methanesulfonyloxy)ethyl]phenoxy}acetate (20).

To a stirred, ice-cold solution of 19 (7.28 g, 28.9 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (15.5 mL, 86.6 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (150 mL) was added methanesulfonyl chloride (5.6 mL, 72.2 mmol). The ice bath was allowed to melt, and the mixture was stirred overnight at rt. The mixture was concentrated, and the residue was taken up in EtOAc (150 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (2 x 50 mL) and brine (50 mL). The EtOAc layer was filtered through Celite. The filtrate was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to leave 20 as a dark red oil which was used without further purification. Yield: 9.72 g (quant); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.11 (m, 2H), 6.88 - 6.76 (m, 2H), 4.47 (s, 2H), 4.40 - 4.28 (m, 2H), 3.02 - 2.91 (m, 2H), 2.81 (s, 3H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

Methyl 4-{4-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]phenyl}-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl]butanoate (22).

A mixture of 20 (6.84 g, 20.7 mmol), methyl 3-oxo-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]propanoate (21, CAS Regno: 212755-76-5, 5.00 g, 20.3 mmol), K2CO3 (2.81 g, 20.3 mmol), Kl (3.37 g, 20.3 mmol) and DMF (50 mL) was stirred at 70 °C for 6 h. The mixture was cooled, diluted with EtOAc (350 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (50 mL), water (50 mL) and brine (50 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a dark brown oil (12.06 g) which was chromatographed on a 120 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-25% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, to provide a ~3:1 mixture of 22 and the O-alkylation product methyl (2)-3-(2-{4-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]phenyl}ethoxy)-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]prop-2-enoate as a pale yellow oil. Yield: 4.89 g (50%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.99 - 7.88 (m, 2H), 7.78 - 7.65 (m, 2H), 7.11 - 7.02 (m, 2H), 6.88 - 6.74 (m, 2H), 4.54 - 4.44 (s, 2H), 3.64 (s, 3H), 3.12 - 2.94 (m, 1H), 2.70 - 2.54 (m, 2H), 2.45 - 2.16 (m, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H).

tert-Butyl 2-(4-{2-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl} phenoxy)acetate (24).

A mixture of ~3:1 22/methyl (2)-3-(2-{4-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]phenyl}ethoxy)-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]prop-2-enoate (1.50 g, 3.1 mmol), 5-chloro-2-hydrazinyl-1H-1,3-benzodiazole (23, CAS Regno: 99122-11-9, 685 mg, 3.8 mmol), HOAc (3 mL) and EtOH (12 mL) was heated in the microwave at 130 °C for 3 h. Prep HPLC gave 24. Yield: 260 mg (13%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.86-7.72 (s, 2H), 7.68 - 7.55 (m, 4H), 7.36 - 7.30 (m, 1H), 6.99 - 6.93 (m, 2H), 6.72 - 6.65 (m, 2H), 4.49 (s, 2H), 2.92 - 2.65 (m, 4H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

2-(4-{2-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl}phenoxy)acetic acid (25).

A solution of 24 (260 mg, 0.42 mmol) in 1:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (6 mL) was stirred at rt for 1h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give 25. Yield: 220 mg (94%); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 5.18 min, m/z: 557 [M+H]+.

2-[2-(4-{2-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl}phenoxy)ethoxy]acetic acid (32)

tert-butyl 2-[2-(methanesulfonyloxy)ethoxy]acetate (27).

To a solution of tert-butyl 2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)acetate (26, CAS Regno: 287174-32-7, 2.06 g, 11.7 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (4.2 mL, 23.4 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (40 mL) was added methanesulfonyl chloride (1.4 mL, 17.3 mmol). The ice bath was allowed to melt, and the mixture was stirred at rt for 6 h. Additional i-Pr2NEt (4.2 mL, 23.4 mmol) and methanesulfonyl chloride (1.4 mL, 17.3 mmol) were added and the mixture was stirred at rt for 18 h. The mixture was concentrated. The residue was taken up in EtOAc (80 mL) and 5% aq HCl (30 mL). The layers were separated and the EtOAc layer was washed with 5% aq HCl (30 mL) and brine (20 mL). The combined aqueous layer was back extracted with EtOAc (20 mL). The combined EtOAc layer was washed with brine (10 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to leave 27 as a brown oil. Yield: (3.33 g, quant); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.39 - 4.23 (m, 2H), 3.93 (s, 2H), 3.80 - 3.63 (m, 2H), 3.00 (s, 3H), 1.44 (s, 5H).

tert-Butyl 2-{2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)phenoxy]ethoxy}acetate (28).

A mixture of 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)phenol (18, 1.80 g, 13.0 mmol), Cs2CO3 (4.67 g, 14.3 mmol) and DMF (30 mL) was stirred at rt for 15 min and a solution of 27 (3.33 g, 13.0 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at rt for 1 d. Potassium iodide (2.17 g, 13.1 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 1 d. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (175 mL) and washed with water (2 x 30 mL), 1 M aq NaOH (30 mL) and brine (30 mL). The water and aq NaOH washes were combined and back extracted with EtOAc. The combined EtOAc layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure to leave an oil (4.61 g). Chromatography on an 80 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-70% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, afforded 28 as an oil. Yield: 950 mg (25%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.20 - 7.04 (m, 2H), 6.93 - 6.77 (m, 2H), 4.18 - 4.11 (m, 2H), 4.09 (s, 2H), 3.95 - 3.86 (m, 2H), 3.85 - 3.76 (m, 2H), 2.83 - 2.74 (m, 2H), 1.47 (s, 9H).

tert-Butyl 2-(2-{4-[2-(methanesulfonyloxy)ethyl]phenoxy}ethoxy)acetate (29).

To a solution of 28 (950 mg, 3.2 mmol) and i-Pr2NEt (1.8 mL, 9.7 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (30 mL) was added methanesulfonyl chloride (0.60 mL, 7.7 mmol). The ice bath was allowed to melt, and the mixture was stirred at rt for 6 h and concentrated. The residue was taken up in EtOAc (90 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (2 x 20 mL) and brine (20 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of 29 as a brown oil which was used without further purification. Yield: 1.14 g (95%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.18 - 7.08 (m, 2H), 6.92 - 6.81 (m, 2H), 4.37 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 4.20 - 4.10 (m, 2H), 4.05 (s, 2H), 3.97 - 3.85 (m, 2H), 2.98 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.83 (s, 3H), 1.48 (s, 9H).

Methyl 4-(4-{2-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]ethoxy}phenyl)-2-[4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl] butanoate (30).

A mixture of methyl 3-oxo-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]propanoate (21, 750 mg, 3.0 mmol), 29 (1.14 g, 3.0 mmol), powdered K2CO3 (420 mg, 3.0 mmol), Kl (500 mg, 3.0 mmol) and dry DMF (12 mL) was stirred in a 70 °C oil bath under N2 for 8 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (90 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (2 x 20 mL) and brine (20 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a mobile oil (1.93 g) which was purified by chromatography on an 80 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-30% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, to give a 2:1 mixture of 30/O-alkylation product methyl 3-[2-(4-{2-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]ethoxy}phenyl)ethoxy]-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]prop-2-enoate as an oil. Yield: 730 mg (45%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) Shift = 8.00 - 7.88 (m, 2H), 7.79 - 7.64 (m, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.84 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.22 - 4.11 (m, 2H), 4.08 (s, 2H), 3.94 - 3.87 (m, 2H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 3.07 - 2.95 (m, 1H), 2.67 - 2.54 (m, 2H), 2.39 - 2.18 (m, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H). O-alkylation byproduct resonances are not reported.

tert-Butyl 2-[2-(4-{2-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl} phenoxy)ethoxy]acetate (31).

A mixture of crude 30 (730 mg, 1.4 mmol), 23 (178 mg, 0.97 mmol), HOAc (1 mL) and MeOH (3 mL) was heated in the microwave at 130 °C for 3 h. Prep HPLC afforded 31 as a solid. Yield: 132 mg, 14%; 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) Shift = 7.82 - 7.55 (m, 6H), 7.45 - 7.34 (m, 1H), 6.98 - 6.88 (m, 2H), 6.75 - 6.65 (m, 2H), 4.08 (s, 2H), 4.07 - 3.99 (m, 2H), 3.87 - 3.81 (m, 2H), 2.92 - 2.83 (m, 2H), 2.78 - 2.68 (m, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H); LRMS (ESI+) tR 6.33 min, m/z: 657 [M+H]+, 601 [M-C4H8+H]+.

2-[2-(4-{2-[1-(5-Chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl}phenoxy) ethoxy]acetic acid (32).

To a stirred solution of 31 (128 mg, 0.19 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (3 mL) was added CF3CO2H (3 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for 0.5 h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give 32 as a tan solid. Yield: 114 mg (92%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.91 - 7.73 (m, 4H), 7.63 - 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.26 (dd, J = 2.2, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 6.77 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.07 (s, 2H), 4.04 - 3.98 (m, 2H), 3.79 - 3.70 (m, 2H), 2.84 - 2.64 (m, 4H); LRMS (ESI+) tR 5.28 min, m/z: 623 [M+Na]+, 601 [M+H]+.

1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-3-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-5-ol (36)

Compounds 34 and 35 were prepared following procedures similar to those in Shi et al.21 tert-Butyl 4-{3-ethoxy-2-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-3-oxopropanoyl}piperidine-1-carboxylate (34). A mixture of tert-butyl 4-(3-ethoxy-3-oxopropanoyl)piperidine-1-carboxylate (33, 3.72 g, 12.4 mmol), 1-(2-bromoethyl)-4-fluorobenzene (CAS Regno: 332-42-3, 2.91 g, 14.3 mmol), K2CO3 (1.89 g, 13.7 mmol), KI (2.27 g, 13.7 mmol) and DMF (30 mL) was stirred at 70 °C for 8 h. The mixture was diluted with EtOAc (175 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (30 mL), water (2 x 30 mL) and brine (30 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a brown oil (6.85 g). Chromatography on an 80 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-40% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, gave crude 34 as a pale yellow oil which was used without further purification. Yield: 3.59 g (68%); 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 7.20-7.03 (m, 2H), 7.01-6.85 (m, 2H), 4.25-3.93 (m, 6H), 3.60-3.52 (m, 1H), 2.80-2.45 (m, 6H), 2.20-2.05 (m, 1H), 1.88-1.45 (m, 2H), 1.40 (s, 9H), 1.18-1.27 (m, 3H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 5.73 min, m/z: 322 [M + Na]+.

tert-butyl 4-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-5-hydroxy-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]piperidine-1-carboxylate (35).

A mixture of 34 (1.70 g, 4.0 mmol), 5-chloro-2-hydrazinyl-1H-1,3-benzodiazole (23, 920 mg, 5.0 mmol), HOAc (3 mL) and EtOH (12 mL) was heated in the microwave at 130 °C for 3 h. Prep HPLC gave 35 as solid. Yield: 1.02 g (58%); 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 7.52-7.63 (m, 2H), 7.31 (dd, J = 8.6, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.14-7.23 (m, 2H), 6.93-7.05 (m, 2H), 4.10 (br d, J = 13.3 Hz, 2H), 2.62-2.90 (m, 6H), 2.42-2.58 (m, 1H), 1.70-1.48 (m, 4H), 1.46 (s, 9H); 19F NMR (CD3OD) δ: −77.45, −119.47; LRMS (ESI+) tR 5.72 min, m/z: 540 [M+H]+,440 [M-C4H8CO2+H]+; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M+H]+ calcd 540.2172; found 540.217.

1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-3-(piperidin-4-yl)-1H-pyrazol-5-ol (36).

A solution of 35 (1.02 g, 1.90 mmol) in 3:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (8 mL) was stirred at rt for 1.5 h and concentrated.

The residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give the HCl salt of 36 as a grey solid. Yield: 829 mg (quant); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 3.90 min, m/z: 440 [M+H]+.

2-{2-[2-(3-{4-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-5-hydroxy-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]phenyl} propoxy) ethoxy]ethoxy}acetic acid (45)

tert-butyl 2-{2-[2-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}acetate (38).

To a stirred, ice-cold suspension of 60% NaH in oil (700 mg, 17.3 mmol) in dry THF (20 mL) was added dropwise over 5 min a solution of 2-[2-(prop-2-yn-1-yloxy)ethoxy]ethan-1-ol (37, 1.78 g, 12.3 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for 1h, recooled in an ice bath and treated with t-butyl bromoacetate (3.65 mL, 24.7 mmol) dropwise over 3 min. The mixture was allowed to warm to rt and stirred for 18 h. The mixture was poured into ice-cold 5% aq HCl (50 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (2 x 40 mL). The combined organic layer was washed with brine (15 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to leave a yellow oil (5.30 g). Chromatography on silica gel, eluted with an ethyl acetate hexane gradient, gave 38 as a colorless oil. Yield: 1.08 g (86%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.18 (s, 2H), 3.96 (d, J = 0.9 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (br. s., 8H), 2.44 - 2.32 (m, 1H), 1.42 (s, 9H).

Methyl 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-iodobenzoyl)butanoate (41).

An oven-dried flask, equipped with a stir bar was charged with methyl 4-iodobenzoate (39, 4.77 g, 18.2 mmol), methyl 4-(4-fluorophenyl)butanoate (40, 2.98 g, 15.2 mmol) and 60% NaH in oil (1.30 g, 31.9 mmol). The flask was sealed with a septum and dry THF (30 mL) was introduced by syringe., followed by MeOH (2 drops). The mixture was stirred at 70 °C under N2 for 8 h, cooled to rt and poured into ice-cold 2.5% aq HCl. The mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 x 35 mL). The combined EtOAc layer was washed with brine (15 mL), dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to leave a wet solid (7.85 g). Chromatography on an 80 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-25% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, afforded 41 as a colorless oil. Yield: 3.77 g (58%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.88 - 7.75 (m, 2H), 7.63 - 7.54 (m, 2H), 7.18 - 7.07 (m, 2H), 6.96 (s, 2H), 4.21 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 2.70 - 2.54 (m, 2H), 2.41 - 2.16 (m, 2H).

Methyl 2-{4-[3-(2-{2-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]ethoxy}ethoxy)prop-1-yn-1-yl]benzoyl}-4-(4-fluorophenyl)butanoate (42).

A flask was charged with 41 (900 mg, 2.1 mmol), 38 (819 mg, 2.2 mmol), CuI (41 mg, 0.21 mmol), Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (150 mg, 0.21 mmol) and sealed with a septum. The flask was evacuated/refilled with N2 (3x), and dry CH2Cl2 (10 mL) and Et3N (2.5 mL) were added via syringe. The flask was evacuated/refilled with N2 (3x), stirred at rt for 2 d and concentrated. The residue was taken up in EtOAc (100 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (2 x 10 mL) and brine (10 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left a brown oil (1.84 g) which was chromatographed on a 40 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-60% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, to provide 42 as an oil. Yield: 760 mg (64%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.86-7.78 (m, 2H), 7.55 - 7.46 (m, 2H), 7.15 - 7.05 (m, 2H), 7.03 - 6.87 (m, 2H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 4.31 - 4.20 (m, 1H), 4.03 (s, 2H), 3.80-3.64 (m, 11H), 2.74 - 2.57 (m, 2H), 2.42 - 2.17 (m, 2H), 1.42 (s, 9H).

Methyl 2-{4-[3-(2-{2-[2-(tert-butoxy)-2-oxoethoxy]ethoxy}ethoxy)propyl]benzoyl}-4-(4-fluorophenyl)butanoate (43).

A solution of 42 (760 mg, 1.4 mmol) in MeOH (20 mL) was stirred with 10% Pd on C (cat. qty.) under H2 (1 atm, balloon) at rt for 4 h. The flask was flushed with N2 and the mixture was filtered through Celite. The filtrate was concentrated to leave a brown oil (730 mg) which was purified by chromatography on a 24 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-70% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, to give 43 as a brown oil. Yield: 460 mg (60%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.86 - 7.76 (m, 2H), 7.35-7.24 (m, 2H), 7.18 - 7.07 (m, 2H), 7.01 - 6.89 (m, 2H), 4.33 - 4.20 (m, 1H), 4.02 (s, 2H), 3.77-3.62 (m, 9H), 3.62 - 3.55 (m, 2H), 3.51 - 3.38 (m, 2H), 2.80 - 2.69 (m, 2H), 2.67 - 2.58 (m, 2H), 2.37 - 2.21 (m, 2H), 1.98 - 1.83 (m, 2H), 1.46 (s, 9H).

tert-butyl 2-{2-[2-(3-{4-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-5-hydroxy-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]phenyl}propoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}acetate (44).

A mixture of 43 (460 mg, 0.82 mmol), 5-chloro-2-hydrazinyl-1H-1,3-benzodiazole (23, 188 mg, 1.03 mmol), HOAc (0.5 mL) and MeOH (1.5 mL) was heated in the microwave at 130 °C for 3 h. Prep HPLC gave 44 as a solid. Yield: 190 mg (33%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.62 - 7.47 (m, 2H), 7.47 - 7.39 (m, 2H), 7.34 - 7.22 (m, 3H), 7.10 - 6.98 (m, 2H), 6.91 - 6.78 (m, 2H), 4.0 (s, 2H), 3.71 - 3.61 (m, 6H), 3.60 - 3.53 (m, 2H), 3.49 - 3.41 (m, 2H), 2.81 - 2.64 (m, 6H), 1.95 - 1.77 (m, 2H), 1.44 (s, 9H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 6.15 min, m/z: 693 [M+H]+, 637 [M-C4H8+H]+.

2-{2-[2-(3-{4-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-5-hydroxy-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]phenyl}propoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}acetic acid (45).

A solution of 44 (165 mg, 0.24 mmol) in 1:1 CH2Cl2/TFA (6 mL) was stirred at rt for 3 h and concentrated. The residue was lyophilized from MeCN/5% aq HCl to give 45 as a tan solid. Yield: 136 mg (90%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.64 - 7.53 (m, 3H), 7.50 - 7.43 (m, 1H), 7.37 - 7.29 (m, 3H), 7.13 - 7.03 (m, 2H), 6.94 - 6.83 (m, 2H), 4.14 (s, 2H), 3.78 - 3.56 (m, 8H), 3.55 - 3.45 (m, 2H), 2.93 - 2.67 (m, 6H), 2.02 - 1.82 (m, 2H).

3-[4-({2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}methyl)phenyl]-1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-1H-pyrazol-5-ol (53)

2-{2-[2-azidoethoxy]ethoxy}ethan-1-ol (47).

A mixture of 2-[2-(2-chloroethoxy)ethoxy]ethan-1-ol (46, 3.75 g, 22.2 mmol), NaN3 (3.60 g, 55.5 mmol) and water (15 mL) was stirred at 80 °C for 1 d, cooled to rt, diluted with 1 M aq NaOH (5 mL, 5.0 mmol) and extracted with ether (3 x 35 mL). The combined ether layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated to leave 47 as a colorless oil. Yield: 2.50 g (64%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.75 - 3.63 (m, 8H), 3.62-3.56 (m, 2H), 3.42-3.35 (m, 2H).

Methyl 4-({2-[2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}methyl)benzoate (49).

To a stirred solution of 47 (1.26 g, 7.2 mmol) and methyl 4-(bromomethyl)benzoate (48, 1.57 g, 6.9 mmol) in dry THF (10 mL) was added 60% NaH in oil (330 mg, 8.3 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt for 5 d, diluted with EtOAc (90 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (20 mL), satd aq NaHCO3 (20 mL) and brine (20 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left an oil (2.40 g) which was chromatographed on a 40 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-80% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, to give 49 as a colorless oil. Yield: 810 mg (36%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.01 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 3.72-3.60 (m, 10H), 3.43 - 3.31 (m, 2H).

Methyl 2-[4-({2-[2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}methyl)benzoyl]-4-(4-fluorophenyl)butanoate (51).

To a mixture of 49 (810 mg, 2.5 mmol) and methyl 4-(4-fluorophenyl)butanoate (50, CAS Regno: 20637-05-2, 280 mg, 1.4 mmol) was added 60% NaH in oil (285 mg, 7.1 mmol), followed by dry THF (5 mL) and MeOH (1 drop). The mixture was heated at reflux under N2 for 5 h, diluted with EtOAc (90 mL), washed with 5% aq HCl (15 mL) and brine (15 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. Removal of the solvent left an oil (1.08 g) which was purified by chromatography on a 40 g silica cartridge, eluted with a 0-100% EtOAc in hexanes gradient, to provide 51. Yield: 170 mg (24%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.92 - 7.80 (m, 2H), 7.48 - 7.35 (m, 2H), 7.11 (dd, J = 5.5, 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.03 - 6.85 (m, 2H), 4.63 (s, 2H), 4.34 - 4.21 (m, 1H), 3.78 - 3.61 (m, 13H), 3.47 - 3.29 (m, 2H), 2.68-2.60 (m, 2H), 2.40 - 2.19 (m, 2H).

3-[4-({2-[2-(2-azidoethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}methyl)phenyl]-1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl] 1H-pyrazol-5-ol (52).

A mixture of 51 (170 mg, 0.35 mmol), 5-chloro-2-hydrazinyl-1H-1,3-benzodiazole (23, 67 mg, 0.37 mmol), TsOH.H2O (14 mg, 0.07 mmol) and MeOH (4 mL) was stirred at 70 °C under N2 for 3 d. Prep HPLC gave 52 as a tan solid. Yield: 94 mg (43%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.64 - 7.35 (m, 6H), 7.32 - 7.19 (m, 1H), 7.05 (dd, J = 5.5, 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.94 - 6.79 (m, 2H), 4.58 (s, 2H), 3.77 - 3.56 (m, 10H), 3.43 - 3.20 (m, 2H), 2.78 (s, 4H); LRMS (ESI+) tR 5.43 min, m/z: 620 [M+H]+.

3-[4-({2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}methyl)phenyl]-1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-1H-pyrazol-5-ol (53).

To a stirred solution of 52 (86 mg, 0.14 mmol) in dry THF (3 mL) was added 1 M Me3P in THF (0.42 mL, 0.42 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt under N2 for 2 h and water (0.3 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at rt for 2 d and 1M aq NaOH (0.5 mL, 0.5 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred at rt for 3 h, diluted with HOAc (1 mL) and purified by prep HPLC to give the TFA salt of 53 as a white solid. Yield: 76 mg (77%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.65 - 7.38 (m, 6H), 7.35 - 7.23 (m, 1H), 7.14 - 7.00 (m, 2H), 6.95 - 6.77 (m, 2H), 4.61 (s, 2H), 3.80 - 3.59 (m, 12H), 3.18 - 3.06 (m, 2H), 2.81 (s, 4H); LRMS (ESI+) tR = 4.23 min, m/z: 594 [M+H]+.

Synthesis of active Nef PROTACs

N-(2-{2-[2-({4-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-5-hydroxy-1H-pyrazol- 3-yl]phenyl}methoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}ethyl)-2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]oxy}acetamide (FC-12988)

To a stirred mixture of 3 (53 mg, 0.17 mmol), the HCl salt of 53 (55 mg, 82 μmol), i-Pr2NEt (80 μL, 0.45 mmol), dry CH2Cl2 (1 mL) and dry DMF (1 mL) was added solid HATU (63 mg, 0.17 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt under N2 for 2 h and concentrated under reduced pressure to remove CH2Cl2. The residue was purified by prep HPLC, followed by lyophilization from MeCN/5% aq HCl, to give FC-12988 as an off-white solid. Yield: 33 mg (43%); 1H NMR (300MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.80 - 7.66 (m, 2H), 7.63 - 7.30 (m, 7H), 7.15 - 6.99 (m, 3H), 6.89 (s, 2H), 5.12 (dd, J = 5.1, 13.4 Hz, 1H), 4.63 - 4.61 (m, 2H), 4.59 - 4.57 (m, 2H), 4.47 - 4.43 (m, 2H), 3.69 - 3.66 (m, 4H), 3.63 - 3.56 (m, 6H), 3.50 - 3.43 (m, 2H), 2.96 - 2.82 (m, 3H), 2.80 - 2.65 (m, 3H), 2.51 - 2.29 (m, 1H), 2.19 - 1.99 (m, 1H); 19F NMR (282MHz, CD3OD) Shift = −77.79, −119.84; LRMS (ESI+) tR = 4.33 min, m/z: 894 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M+H]+ calcd 894.302408; found: 894.304560.

2-[2-(4-{2-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-5-hydroxy-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]ethyl}phenoxy)ethoxy]-N-(2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]amino}ethyl)acetamide (FC-13182)

To a stirred solution of 6 (14.5 mg, 41 μmol), 32 (26 mg, 41 μmol), HOBt.H2O (7 mg, 45 μmol) and i-Pr2NEt (40 μL, 0.22 mmol) in dry DMF (1 mL) was added EDC.HCl (16 mg, 84 μmol). The mixture was stirred overnight at rt and purified by prep HPLC to give the TFA salt of FC-13182 as a yellow solid. Yield: 23 mg (50%); 1H NMR (300MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.03 - 7.95 (m, 1H), 7.89 - 7.76 (m, 4H), 7.62 - 7.48 (m, 3H), 7.25 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.06 - 6.96 (m, 3H), 6.82-6.63 (m, 3H), 5.07 - 4.96 (m, 1H), 4.04 (br s, 2H), 3.92 (s, 2H), 3.78 - 3.69 (m, 2H), 3.42 - 3.22 (m, 4H), 2.95 - 2.77 (m, 1H), 2.76-2.63 (m, 4H), 2.61 - 2.54 (m, 1H), 2.44 - 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.04 - 1.91 (m, 1H); 19F NMR (282MHz, DMSO-d6) δ −61.09, −74.88; LRMS (ESI+) tR 5.38 min, m/z 899 [M+H]+; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M+H]+ calcd 899.2526; found: 899.2529.

2-{2-[2-(3-{4-[1-(5-chloro-1H-1,3-benzodiazol-2-yl)-4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)ethyl]-5-hydroxy-1H-pyrazol-3-yl]phenyl}propoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy}-N-(2-{[2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-4-yl]amino}ethyl)acetamide (FC-13818)