Summary

Despite the rapid and sustained antidepressant effects of ketamine and its metabolites, their underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms are not fully understood. Here, we demonstrate that the sustained antidepressant-like behavioral effects of (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine (HNK) in repeatedly stressed animal models involve neurobiological changes in the anterior paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (aPVT). Mechanistically, (2S,6S)-HNK induces mRNA expression of extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, and subsequently enhances GABAA receptor-mediated tonic currents, leading to the nuclear export of histone demethylase KDM6 and its replacement by histone methyltransferase EZH2. This process increases H3K27me3 levels, which in turn suppresses the transcription of genes associated with G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Thus, our findings shed light on the comprehensive cellular and molecular mechanisms in aPVT underlying the sustained antidepressant behavioral effects of ketamine metabolites. The present study may support the development of potentially effective next-generation pharmacotherapies to promote sustained remission of stress-related psychiatric disorders.

eTOC blurb

Kawatake-Kuno, Li, Inaba et al. considered a midline thalamic structure, the aPVT, a crucial brain region involved in the sustained antidepressant-like effects of the ketamine metabolite (2S,6S)-HNK. Moreover, they uncover the mechanisms whereby this drug drives its antidepressant-like effects via modulation of GABAergic inhibition-mediated epigenetic regulations in the aPVT.

Introduction

A single sub-anesthetic dose of ketamine produces rapid and sustained antidepressant effects in both humans and animals 1-4. Accumulating research has focused on elucidating the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant actions of ketamine to develop novel pharmacotherapies, which would mimic ketamine’s antidepressant actions without undesirable effects 5-9; yet the mechanistic basis for the observed behavioral responses to these compounds remains to be fully understood.

Ketamine is decomposed into several types of metabolites 10. Among them, (2S,6S;2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine (HNK) is the major metabolite in the brain 10; the HNK enantiomer (2R,6R)-HNK has attracted much attention as a potential antidepressant agent with less undesirable side effects than ketamine [(R,S)-ketamine]. (2R,6R)-HNK has been shown to increase the activity of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-iso-xazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors and to directly bind to the brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptor TrkB; however, these effects were negligible for the (2S,6S)-HNK enantiomer 10,11, regardless of its potential antidepressant activity 10,12. Thus, (2R,6R)-HNK and (2S,6S)-HNK could have different mechanisms of action.

Because depression is a highly heterogeneous syndrome, recent research has focused on data-driven biological subtypes or biotypes to generate more effective treatments based on a deeper understanding of its biological basis 13-17. However, understanding which patients will respond to and tolerate a chosen antidepressant drug –or not– is still one of the biggest challenges in treating depression. Thus, identifying the mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of various ketamine metabolites may assist in the development of next-generation depression subtype-specific pharmacotherapy.

In this study, we examined the effectiveness of (2R,6R)-HNK and (2S,6S)-HNK in repeatedly stressed animal models and uncover the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved. Our findings highlight previously missing brain regions and molecular pathways as potential therapeutic targets to promote sustained remission of stress-related psychiatric disorders.

Results

(2S,6S)-HNK elicits a rapid and sustained antidepressant behavioral effect in stressful situations

We compared the effects of the ketamine metabolites (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK on a repeated tail-suspension test (rTST) model. In this model, we subjected C57BL/6J (B6) mice to tail-suspension stress (6 min per day) for 5 consecutive days (Figures S1A-S1B). The increased immobility time following the induction phase was maintained for ≥7 days (Figure S1B), enabling us to investigate not only acute but also sustained antidepressant drug effects. (2S,6S)-HNK, but not (2R,6R)-HNK, significantly reduced the immobility time by 30 min after a single injection (20 mg/kg) (Figures 1A and 1B); this effect was maintained over 3 days (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1. (2S,6S)-HNK has rapid and sustained antidepressant effects without ketamine-related side effects.

(A) Experimental design for rTST model.

(B–D) Immobility time of the rTST-exposed B6 mice 30 min, 24 h, and 3 days after drug treatment. n = 12 per group.

(E) Experimental design for CSDS model.

(F–H) Representative heatmaps (F), time spent in the target zone of the SIT in nonstressed (NS) and CSDS-exposed resilient (RES) and susceptible (SUS) mice before (G) and after (H) drug treatment. n = 10 per group.

(I) Experimental design for smSDS model.

(J and K) Time spent in the target zone of the SIT (J) and sucrose preference in the SPT (K) in NS and smSDS-exposed mice receiving (2R,6R)-HNK, (2S,6S)-HNK, or saline. n = 14–15 per group.

(L) Experimental design for sustained behavioral effects of smSDS-exposed BALB mice receiving (2S,6S)-HNK.

(M) Time spent in the target zone of the SIT in NS and smSDS-exposed mice receiving (2S,6S)-HNK or saline. n = 15–16 per group.

(N) Locomotor activity in the OFT was shown.

(O) Locomotor activity during 30 min of OFT after drug treatment. n = 8–12 per group.

(P) Latency to fall in the rotarod test. n = 11–12 per group.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

Moreover, we investigated the antidepressant-like effects of (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK in the chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) model, which is a well-validated paradigm for inducing long-lasting social interaction deficits and anhedonic states in mice 18 (Figures 1E-1G). We found that (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK increased the social interaction (SI) ratio of the social interaction test (SIT) in susceptible (SUS) mice, defined by a SI ratio < 1.0 in SIT 18 (Figure 1H). In the sucrose preference test (SPT) (Figure S1C), which is used as an indicator of rodent anhedonia, we defined SPT-SUS mice if their sucrose preference (z-score) was <−1.0 (SPT-1) (Figure S1D). We found that (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK reduced the anhedonic state of SUS mice after 24 h (SPT-2) (Figure S1E). The behavioral effect of (2S,6S)-HNK but not (2R,6R)-HNK was maintained for 3 days (SPT-3) (Figure S1F).

Gene–environment (GxE) interactions underlie depression pathophysiology 19-21. BALB/c (BALB) strain could serve as a GxE animal model of depression 22-26. Therefore, we subjected this mouse strain to subchronic and mild social defeat stress (smSDS), an abbreviated form of CSDS 25,26; then, we conducted SIT at 24 h and SPT at 3 days after treatment with (2R,6R)-HNK, (2S,6S)-HNK, or saline (Figure 1I). smSDS-exposed mice receiving (2S,6S)-HNK but not (2R,6R)-HNK showed antidepressant-like behaviors (Figures 1J and 1K). We also found that the rapid antidepressant-like effect of (2S,6S)-HNK (30 min after drug treatment) in SIT was maintained for up to 28 days (Figures 1L and 1M). Similarly, the antidepressant-like effect of (2S,6S)-HNK in SPT was maintained for ≥14 days (Figures S1G and S1H).

In contrast to the repeated stress condition, we did not find any significant behavioral effects of (2S,6S)-HNK on the immobility time of an acute TST (aTST) model in which B6 mice were not exposed to any physiological or psychological stressors before drug treatment (Figures S1I-S1K). However, (2R,6R)-HNK treatment resulted in a significantly shorter immobility time than saline-treated mice (Figures S1I-S1K). Overall, these behavioral data suggest that the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of each HNK could depend on the brain and/or emotional states of the animal models used (Figure S1L).

In rodent models, hyperlocomotion and motor incoordination are considered important indicators of the psychoactive effects of ketamine 10. A single dose of (R,S)-ketamine (20 mg/kg) significantly increased the distance traveled in the open field test and induced motor incoordination in the rotarod test, whereas both (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK at the same dose (20 mg/kg) had no effects (Figures 1N -1P). These data are in agreement with a previous report showing that ketamine metabolites are less prone to induce undesirable side effects than ketamine 10.

Brain-wide Fos mapping identifies aPVT as being stimulated by (2S,6S)-HNK

To identify the brain regions that respond to (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK, we quantified Fos expression as a proxy for neural activity in 27 selected brain regions 90 min after (2S,6S)-HNK or (2R,6R)-HNK treatment in the rTST model (Figure 2A). We found three different patterns of Fos immunoreactivity: (i) brain regions with Fos immunoreactivity levels commonly upregulated by (2S,6S)-HNK and (2R,6R)-HNK (i.e., IL, PL, Acbsh, MeA, and CeA); (ii) brain regions with Fos immunoreactivity levels upregulated by (2S,6S)-HNK but not (2R,6R)-HNK [i.e., bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), aPVT, and vCA3]; and (iii) brain regions with Fos immunoreactivity levels upregulated by (2R,6R)-HNK but not (2S,6S)-HNK (i.e., aCC, dCA1, BLA, MHb, RSG, and RSD) (Figures 2B-2D, Figure S2A). Among them, the anterior part of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (aPVT) showed significantly higher Fos immunoreactivity, specifically with (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures 2B and S2A). We then sought to identify putative brain networks underlying the antidepressant effects of HNK by generating a correlation matrix (Figures 2E and 2F) and a network connectivity graph (Figures 2G-2H) from Fos data. Notably, our unbiased analysis identified a strong positive correlation between aPVT and the BNST or the nucleus accumbens shell (Acbsh) in mice receiving (2S,6S)-HNK but not (2R,6R)-HNK (Figures 2G and 2H). Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated neural circuit mapping revealed that aPVT glutamatergic neurons innervate many brain regions, including Acbsh, BNST, IL, BLA, CeA, dHPC, and vHPC (Figure 2I), which were stimulated by (2S,6S)-HNK or (2R,6R)-HNK (Figures 2B-2D). These data suggest that the aPVT could be an upstream brain region involved in regulation of the behaviors observed in HNK-treated mice.

Figure 2. Brain-wide Fos mapping identifies the aPVT as a specific brain area responsible for (2S,6S)-HNK but not (2R,6R)-HNK effects.

(A) Experimental design of Fos quantification.

(B) Quantification of Fos immunostaining in B6 mice receiving (2R,6R)-HNK, (2S,6S)-HNK, or saline. n = 8 per group.

(C and D) Brain-wide Fos levels of mice receiving (2R,6R)-HNK (C) and (2S,6S)-HNK (D) compared with saline controls (z-score).

(E and F) Inter-regional correlations for brain-wide Fos immunoreactivity in mice receiving (2R,6R)-HNK (E) and (2S,6S)-HNK (F).

(G and H) Most robust (top 2%) inter-regional correlations.

(I) Representative images showing aPVT projections to multiple brain regions.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

We also found that smSDS-exposed BALB mice showed reduced Fos levels in both aPVT and pPVT; this reduction was reversed by treatment with (2S,6S)-HNK but not (2R,6R)-HNK in only aPVT (Figures S2B-S2E). In addition, (2S,6S)-HNK-induced Fos expression was transient (~4 h) (Figures S2F-S2H). Moreover, (2S,6S)-HNK-mediated Fos immunoreactivity was observed in CaMKII2α-positive glutamatergic neurons of the aPVT in both rTST-exposed B6 and smSDS-exposed BALB models (Figures S2I and S2J). These results suggest that the transient activation of aPVT glutamatergic neurons may be relevant to the antidepressant-like effects of (2S,6S)-HNK.

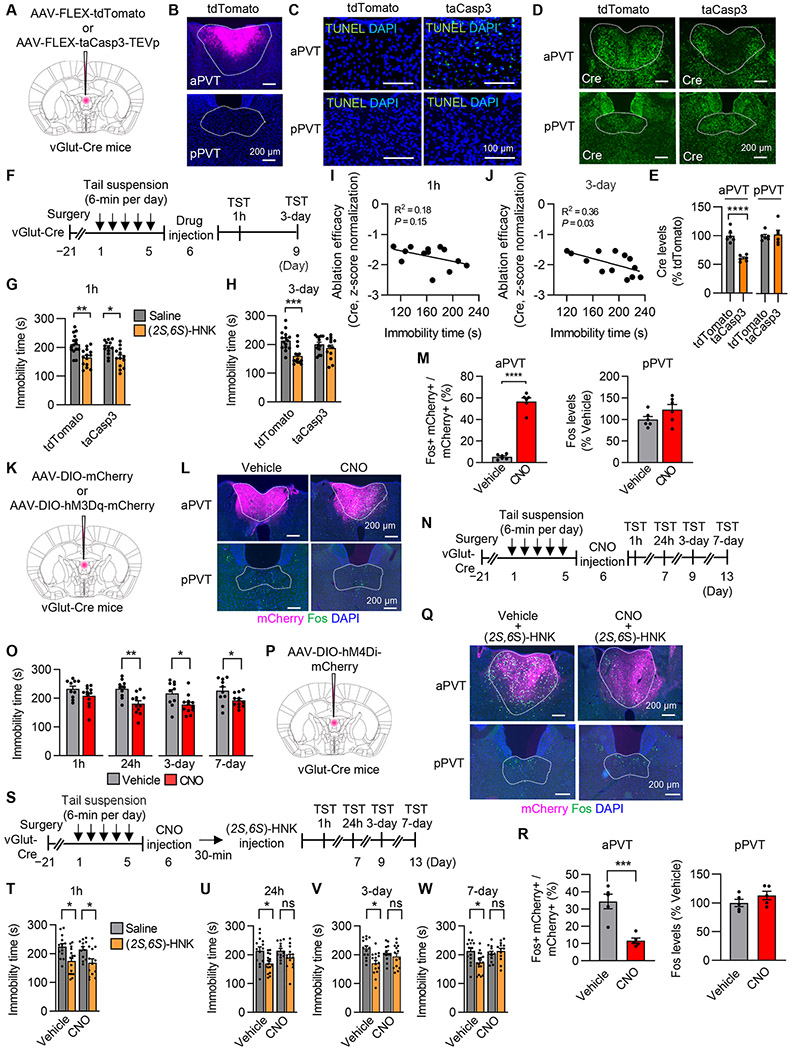

aPVT glutamatergic neurons are required for the sustained antidepressant effects of (2S,6S)-HNK

We investigated whether aPVT can explain the rapid and/or sustained antidepressant-like effects of (2S,6S)-HNK using the rTST (Figures S3A-S3C) and smSDS models (Figures S3D-S3H). We found that intra-aPVT infusion of (2S,6S)-HNK exerted sustained (24 h~7 days), but not rapid (1 h) antidepressant effects in both stress models. Next, we conducted a loss-of-function study using a genetic approach to selectively ablate aPVT glutamatergic neurons. We injected Cre-dependent AAVs encoding a modified procaspase 3 and TEV protease (AAV-FLEX-taCasp3-TEVp) 27 into the aPVT of vGlut-Cre mice (B6 genetic background) to selectively target aPVT glutamatergic neurons (Figures 3A-3E). Then, mice were injected with (2S,6S)-HNK following the rTST induction phase, and 1 h and 3 days later, TST was performed again (Figure 3F). We found that mice lacking aPVT glutamatergic neurons showed reduced immobility time 1 h after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment as did nonablation control mice (Figure 3G). However, this effect disappeared 3 days after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment, as nonablation control mice still exhibited reduced immobility time (Figure 3H). There was a significant inverse correlation between the immobility time and Cre expression (indicator of ablation efficacy) at 3 days, but not 1 h after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures 3I and 3J), indicating that (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained antidepressant effects depend on aPVT glutamatergic neuron function. We also confirmed that ablation of aPVT glutamatergic neurons in smSDS model (Figures S4A-S4C) suppressed (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained but not rapid antidepressant-like behavioral effects (Figures S4D-S4F).

Figure 3. aPVT glutamatergic neurons are necessary for the sustained, but not rapid, antidepressant effects of (2S,6S)-HNK.

(A) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(B) Representative image showing tdTomato expression in the PVT. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(C) TUNEL staining in coronal sections of the PVT. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D and E) Representative image (D) and quantification (E) showing Cre expression (indicator of ablation efficacy) in the PVT. Scale bar, 200 μm. n = 6 per group.

(F) Experimental design for aPVT ablation.

(G and H) Immobility time of the rTST 1 h (G) and 3 days (H) after (2S,6S)-HNK injection. n = 13–15 per group.

(I and J) Correlation of aPVT neuronal ablation efficacy (Cre expression levels) with the immobility time of the TST at 1 h (I) and 3 days (J) after (2S,6S)-HNK injection.

(K) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(L) Representative image showing hM3Dq-mCherry and Fos expression in the aPVT and pPVT. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(M) Quantification of Fos expression in the aPVT and pPVT 90 min after injection of CNO or vehicle in hM3Dq mice.

(N) Experimental design for hM3Dq-DREADD.

(O) Immobility time of rTST hM3Dq mice 1 h, 24 h, 3 and 7 days after CNO or vehicle treatment. n = 10–12 per group.

(P) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(Q) Representative image showing hM4Di-mCherry and Fos expression in the aPVT and pPVT of hM4Di mice 90 min after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(R) Quantification of Fos expression in the aPVT and pPVT 90 min after injection of CNO or vehicle in hM4Di mice.

(S) Experimental design for hM4Di-DREADD.

(T–W) Immobility time of rTST-exposed hM4Di mice 1 h (T), 24 h (U), 3 days (V), and 7 days (W) after (2S,6S)-HNK injection. n = 12–16 per group.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

(2S,6S)-HNK-induced aPVT glutamatergic neuron activity is required for sustained antidepressant-like effects

Next, we examined whether transient activation of aPVT glutamatergic neurons is sufficient for rapid and/or sustained antidepressant-like effects. To this end, aPVT neurons in rTST-exposed vGlut-Cre mice receiving AAV-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry were activated, and their immobility time was assessed 1 h, 24 h, 3 days, and 7 days after the administration of clozapine N-oxide (CNO) (Figures 3K-3O). We confirmed increased neuronal activity in aPVT by measuring Fos immunoreactivity after 90 min of CNO treatment (Figures 3L and 3M). rTST-exposed mice expressing hM3Dq-mCherry showed significantly less immobility time at 24 h, 3 days, and 7 days, but not at 1 h, after CNO treatment compared with vehicle-treated controls (Figure 3O). rTST-exposed mice expressing control mCherry did not show any significant effects of CNO on the immobility time at any time point (Figure S4G).

We investigated whether the transient activation of aPVT glutamatergic neurons in response to (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figure 2B) is necessary for rapid and/or sustained antidepressant-like effects. To this end, aPVT neurons in rTST-exposed vGlut-Cre mice receiving AAV-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry were suppressed, and their immobility time was assessed at the same time points after (2S,6S)-HNK administration as before (Figures 3P-3W). Immunohistochemistry revealed suppression of (2S,6S)-HNK-induced Fos expression in aPVT by CNO pretreatment (Figures 3Q and 3R). Pretreatment with CNO prevented the (2S,6S)-HNK-induced reduction of immobility time at 24 h, 3, and 7 days, but not at 1 h (Figures 3T-3W). We also confirmed that hM4Di-mediated suppression of (2S,6S)-HNK-induced transient activation of aPVT glutamatergic neurons abolished the improved effects on SI and sucrose preference in the smSDS model (Figures S4H-S4N). Taken together, these results suggest that the transient activation of aPVT glutamatergic neurons following (2S,6S)-HNK treatment is necessary for the long-lasting, but not acute, antidepressant-like behavioral effects of this drug.

Transient transcription and translation within aPVT are necessary for sustained antidepressant-like behavioral effects of (2S,6S)-HNK

We hypothesized the involvement of activity-dependent transcription and translation following (2S,6S)-HNK treatment within aPVT in sustained antidepressant-like behaviors. We tested rTST-exposed mice infused with the RNA polymerase inhibitor actinomycin D (ActD) in the aPVT 30 min before (2S,6S)-HNK injection (i.p.) at 1 h, 24 h, 3 and 7 days later in the TST (Figures S5A-S5F). ActD preinfusion abolished the sustained but not rapid antidepressant-like behavioral effect of (2S,6S)-HNK on immobility time (Figures S5C-S5F). Similarly, we observed that preinfusion of the protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin (ANI) into aPVT prevented the sustained but not rapid antidepressant-like behavioral effect of (2S,6S)-HNK on immobility time (Figures S5G-S5J). These results indicate that (2S,6S)-HNK-initiated transient transcription and translation within aPVT is required for its sustained antidepressant-like behavioral effects.

RNA-seq reveals key molecular signatures of (2S,6S)-HNK treatment in aPVT

To address how (2S,6S)-HNK elicits its sustained antidepressant-like behaviors, we performed RNA-seq to compare genome-wide transcriptional changes in the aPVT of smSDS-exposed BALB mice 7 days after (2S,6S)-HNK or saline treatment (Figure 4A). We found three main gene categories: (1) 506 genes regulated by smSDS (as a result of stress exposure), (2) 1607 genes regulated by (2S,6S)-HNK under repeated stress (as a result of (2S,6S)-HNK response), and (3) 385 genes regulated reciprocally by smSDS and (2S,6S)-HNK treatment, which may be associated with both stress pathophysiology and antidepressant-like action (Figure 4B). Gene Ontology (GO) and ENCODE Transcription Binding Sites analyses on Enrichr 28 (Figures 4C-4F and Figures S6A-S6H) and a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis in Metascape 29 (Figures 4G-4I) revealed several key aspects. First, ENCODE predicted the potential involvement of SUZ12/EZH2-mediated transcription regulation in both smSDS exposure and (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figure 4C). Second, PPI indicated enrichment for functions related to GPCR signaling in smSDS exposure and (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures 4G-4I). Finally, GO and PPI analyses showed enrichment for functions related to GABAA receptor activity in (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures 4E and 4I).

Figure 4. RNA sequencing reveals the dynamic molecular processes underlying (2S,6S)-HNK’s effects.

(A) Heatmap showing expression levels of all differentially expressed genes in NS-Saline, smSDS-Saline, and smSDS-(2S,6S)-HNK. n = 3 per group. R: replicate.

(B) Venn diagram depicting the overlapping genes.

(C–F) Significant (p-value or adj.p-value <0.05) enrichment of transcription factor binding (ENCODE) and Top 5 GO terms (Molecular Function) identified by Enrichr.

(G–I) Protein-protein interaction network analysis for the three highlighted MCODE components identified in Metascape.

(J) Proposed RNA-seq data-driven model of the molecular mechanisms underlying the sustained antidepressant effects produced by (2S,6S)-HNK.

We selected 26 RNA-seq-driven genes reciprocally regulated by smSDS exposure and (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures S6I) or upregulated by (2S,6S)-HNK (Figure S6J) for the validation. A quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis revealed significant changes in the expression of 17 genes under smSDS exposure and/or (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures S6I and S6J). Among these genes, we further selected eight genes: Gng8, Tac1, Cckbr, and Gnb3 for GPCR signaling and Gabra1, Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd for GABAA receptor activity, and quantified their mRNA levels in smSDS-exposed mice 1 h, 6 h, 24 h, 3 and 7 days after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. We found that (2S,6S)-HNK treatment normalized the smSDS-induced mRNA levels of Gng8, Tac1, Cckbr, and Gnb3 at 24 h, 3, and 7 days, but not at 1 or 6 h (Figure S6K). In addition, (2S,6S)-HNK treatment significantly increased Gabra1, Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd mRNA levels at 6 h, 24 h, 3, and 7 days, but not at 1 h (Figure S6L). Thus, (2S,6S)-HNK increases the expression of genes related to GABAA receptor activity (~6 h) before downregulating that of genes related to GPCR signaling (~24 h).

RNA-seq data predicted the SUZ12/EZH2 as an upstream regulator for transcriptional regulation associated with the antidepressant effects of (2S,6S)-HNK. SUZ12 and EZH2 are core subunits of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which catalyzes the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me3), silencing target genes 30. Conversely, histone demethylase KDM6 (known as JMJD3) is a specific H3K27me3 histone demethylase that promotes target gene activation 31,32. Therefore, we hypothesized that (2S,6S)-HNK treatment normalized smSDS-induced activation of gene transcription related to GPCR signaling by exchanging KDM6 with SUZ12/EZH2 to increase H3K27me3 levels, thereby repressing the transcription of these genes (Figure 4J).

EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 in the aPVT drives antidepressant-like behavioral effects

To test this hypothesis, we quantified H3K27me3 levels in aPVT neurons of smSDS-exposed mice 7 days after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. We found that smSDS-exposed mice exhibited significantly lower H3K27me3 levels; however, (2S,6S)-HNK treatment normalized them (Figures 5A and 5B). Then, we developed an aPVT-specific focal knockdown of EZH2 expression using AAV-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 system in BALB mice (Figure 5C), which decreased EZH2 protein (Figures 5D and 5E) and H3K27me3 levels (Figures S7A and S7B). We evaluated their behavior by SIT and SPT (Figure 5F); EZH2 knockdown mice showed significantly less SI and sucrose preference (Figures 5G-5H). Moreover, the increased depression-like behaviors in the SIT and SPT in EZH2 knockdown mice were not ameliorated by (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures 5I and 5J). The rTST model was used to validate the effect of loss-of-function EZH2 on (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant effects (Figure S7C-S7E). We found that (2S,6S)-HNK treatment had rapid (1 h), but not sustained (24 h and 3 days) antidepressant effects in rTST-exposed EZH2 knockdown mice (Figures S7F-S7H).

Figure 5. EZh2-mediated H3K27me3 upregulation in the aPVT drives antidepressant-like behaviors.

(A) Representative image showing H3K27me3 and NeuN expression in smSDS-exposed BALB mice 7 days after (2S,6S)-HNK or saline treatment. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B) Cumulative distribution of immunofluorescent signals for H3K27me3 in aPVT cells. n = 27,702-29,440 cells from 6 mice per group.

(C) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(D) Representative image showing saCas9-HA and Ezh2 expression. Scale bar, 200 and 100 μm for low and high magnification images.

(E) Quantification of Ezh2 signals in HA-positive and HA-negative aPVT cells of mice expressing sgControl and sgEzh2.

(F) Experimental design for Ezh2 knockdown.

(G–J) Time spent in target zone of the SIT-1 (G) and sucrose preference of the SPT-1 (H) and in SIT-2 (I) and SPT-2 (J) after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. n = 16–21 (G and H) and n = 10–11 (I and J) per group.

(K) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(L) Experimental design for spatiotemporal overexpression of Ezh2-WT or its constitutive active mutant Ezh2-Y641F.

(M) Representative image showing HA/tdTomato and H3K27me3 expression in mice expressing tdTomato, wildtype Ezh2, or Ezh2-Y641F. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(N) Quantification of H3K27me3 immunostaining in mice expressing tdTomato, Ezh2-WT, or Ezh2-Y641F in the aPVT. n = 8 per group.

(O and P) Time spent in target zone of the SIT (O) and sucrose preference of the SPT (P) in smSDS-exposed mice overexpressing tdTomato, wildtype Ezh2, or Ezh2-Y641F in the aPVT. n = 14–16 per group.

*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

We next investigated the effects of a gain-of-function EZH2 mutation on antidepressant-like behaviors. BALB mice were microinjected with AAV-Camk2a-CreERT2 together with a Cre-inducible AAV-expressing wildtype EZH2 (EZH2-WT), a constitutively active EZH2 mutant (EZH2-Y641F) 33,34, or nucleus-localized tdTomato (NLS-tdTomato, as a control) into the aPVT and exposed to smSDS. Then, mice received 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), an active metabolite of tamoxifen, three times every other day to induce transgene expression, and their behaviors were tested by SIT and SPT (Figures 5K-5P). We detected increased H3K27me3 levels by overexpressing EZH2-Y641F (Figures 5M, 5N, and S7I). Behaviorally, smSDS mice expressing NLS-tdTomato showed significantly less SI and sucrose preference than nonstressed controls, whereas smSDS-induced depression-like behaviors were prevented by the overexpression of EZH2-Y-641F but not of EZH2-WT (Figures 5O and 5P). Despite the lack of effects of EZH2-WT overexpression, this may be due to weak histone-methylating activity of Ezh233 and because other members of the PRC2 complex, including EED, SUZ12, AEBP2, and RbAp48, may be required for full activity. These results suggest essential roles of EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 in depression-like behaviors and (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained antidepressant-like behavioral effects.

KDM6-mediated H3K27me3 demethylation increases depression-like behavior

Next, we investigated the role of KDM6-mediated demethylation of H3K27me3 in depression-like behavior. GSK-J4 is a cell-permeable prodrug for GSK-J1 comprising a potent inhibitor of KDM6A/B that preserves H3K27me3 35. In the rTST model, we found that GSK-J4 treatment (10 mg/kg i.p.) significantly reduced the immobility time 24 h after drug injection; this effect was maintained ≥7 days (Figures S8A and S8B). We also used GSK-J4 in the smSDS model (Figure S8C), finding reversal in the deficit in SI by smSDS exposure (SIT-1) (Figure S8D) 24 h after GSK-J4 treatment (SIT-2) (Figure S8E), which was maintained at 3 days after treatment (SIT-3) (Figure S8F).

To characterize the role of aPVT KDM6 in depression-like behavior, BALB mice were microinjected with AAV-Camk2a-CreERT2 together with Cre-inducible AAV-expressing microRNAs (miRs) targeting Kdm6a and Kdm6b (AAV-miR-KDM6) or control miRNAs (AAV-miR-Scramble) into aPVT (Figure 6A) and exposed to smSDS. Then, they received 4-OHT three times every other day to induce miR expression, and their behaviors were tested by SIT (Figure 6B). We confirmed successful aPVT KDM6A and KDM6B knockdown at the protein level (Figures 6C and 6D) and the prevention of smSDS-mediated demethylation of H3K27me3 in mice expressing miR-KDM6 (Figures 6E-6F). There were no effects of KDM6 knockdown on total histone H3 levels (Figure 6G). Behaviorally, mice expressing scramble miRNAs showed significantly less SI following smSDS exposure (Figure 6H), which was improved by aPVT-specific KDM6 knockdown (Figure 6H), suggesting that KDM6-mediated H3K27me3 demethylation confers depression-like behavior.

Figure 6. KDM6B-mediated H3K27me3 regulation is critical for depression-like behaviors and the behavioral response to (2S,6S)-HNK.

(A) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(B) Experimental design for spatiotemporal KDM6 knockdown in BALB mice.

(C) Representative image showing GFP and KDM6A or KDM6B expression in the aPVT of mice. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(D) Quantification of KDM6A and KDM6B immunostaining in the aPVT of mice expressing miR-KDM6 or miR-Scramble. n = 5–6 per group.

(E) Representative image showing GFP, H3K27me3, and Histone H3 expression in the aPVT of mice expressing miR-KDM6 or miR-Scramble. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(F and G) Cumulative distribution (left) and mean value (right) of immunofluorescent signals for H3K27me3 (F) and Histone H3 (G) in GFP-positive neurons. n = 6 mice per group.

(H) Time spent in target zone of the SIT. n = 12–13 per group.

(I) Schematic of AAV microinjection into the aPVT of BALB mice.

(J) Experimental design. BALB mice were tested by SIT (SIT-1) and SPT (SPT-1). Mice injected with AAV-KDM6B-CT-WT were treated with (2S, 6S)-HNK and tested gain with SIT (SIT-2) and SPT (SPT-2).

(K) Representative image showing GFP/HA and H3K27me3 levels in the aPVT of mice expressing GFP, KDM6B-CT-WT, or KDM6B-CT-H1388A. Scale bar, 200 μm. High magnification images are shown in Figure S8G.

(L) Quantification of H3K27me3 levels in the aPVT of mice expressing GFP, KDM6B-CT-WT, or KDM6B-CT-H1388A.

(M–P) Time spent in target zone of the SIT-1 (M) and sucrose preference of the SPT-1 (N) and in SIT-2 (O) and SPT-2 (P) after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. n = 14–19 (M and N) and n = 9–10 (O and P) per group.

(Q) Experimental design for KDM6B nuclear localization in smSDS mice receiving (2S, 6S)-HNK or saline.

(R) Representative image showing KDM6B and NeuN expression in the aPVT. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(S) Quantification of KDM6B signals in the cytoplasm and nucleus of NeuN-positive neurons in the aPVT. n = 8 per group.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

To further determine whether the demethylase activity of KDM6 in aPVT glutamatergic neurons is required for depression-like behavior, BALB mice were microinjected with AAVs expressing a nucleus-localized C-terminal WT KDM6B truncate (AAV-NLS-HA-KDM6B-CT-WT), which mimics the function of the full-length KDM6B protein 36,37, the catalytically inactive mutant H1388A 38 (AAV-NLS-KDM6B-CT-H1388A), or nucleus-localized EGFP (AAV-NLS-EGFP), under the control of a CaMKIIα promoter. The animals were then tested before (SIT-1 and SPT-1) and after (SIT-2 and SPT-2) treatment with (2S,6S)-HNK (Figures 6I and 6J). Mice expressing NLS-KDM6B-CT-WT, but not NLS-KDM6B-CT-H1388A, exhibited decreased H3K27me3 signals in the aPVT (Figures 6K, 6L, S8G) and less SI and sucrose preference (Figures 6M and 6N) than mice expressing GFP. In addition, mice expressing NLS-KDM6B-CT-WT did not respond to (2S,6S)-HNK in the SIT and SPT (Figures 6O and 6P). In the rTST model (Figures S8H-S8J), mice expressing NLS-KDM6B-CT-WT showed rapid, but not sustained, antidepressant-like behavioral effects, whereas those expressing NLS-KDM6B-CT-H1388A showed both rapid and sustained effects (Figures S8K-S8M). These results suggest that KDM6-mediated demethylation of H3K27me3 results in depression-like behaviors and prevents (2S,6S)-HNK’s actions on behaviors.

(2S,6S)-HNK treatment promotes nuclear export of KDM6B

To determine whether repeated stress and/or (2S,6S)-HNK treatment could affect the subcellular localization of KDM6 and/or EZH2, smSDS-exposed BALB mice were injected with (2S,6S)-HNK once; at 3 days, KDM6B and EZH2 immunoreactivities in the cytoplasm and nucleus (NeuN was used as marker for neuronal nuclei) were measured (Figures 6Q-6S, S8N, S8O). We found that in aPVT neurons, smSDS exposure decreased cytoplasmic and increased nuclear localization of KDM6, whereas (2S,6S)-HNK treatment promoted cytoplasmic localization of KDM6B (Figures 6R-6S). We did not find any obvious changes in the nuclear localization of EZH2 by smSDS exposure or (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures S8N and S8O). Thus, these results support our hypothesis that (2S,6S)-HNK exerts its antidepressant-like effects by exchanging KDM6 with EZH2 to regulate H3K27me3 levels and subsequent target gene expression (Figure 4J).

GNB3 is associated with depression-like behaviors and (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained antidepressant effect

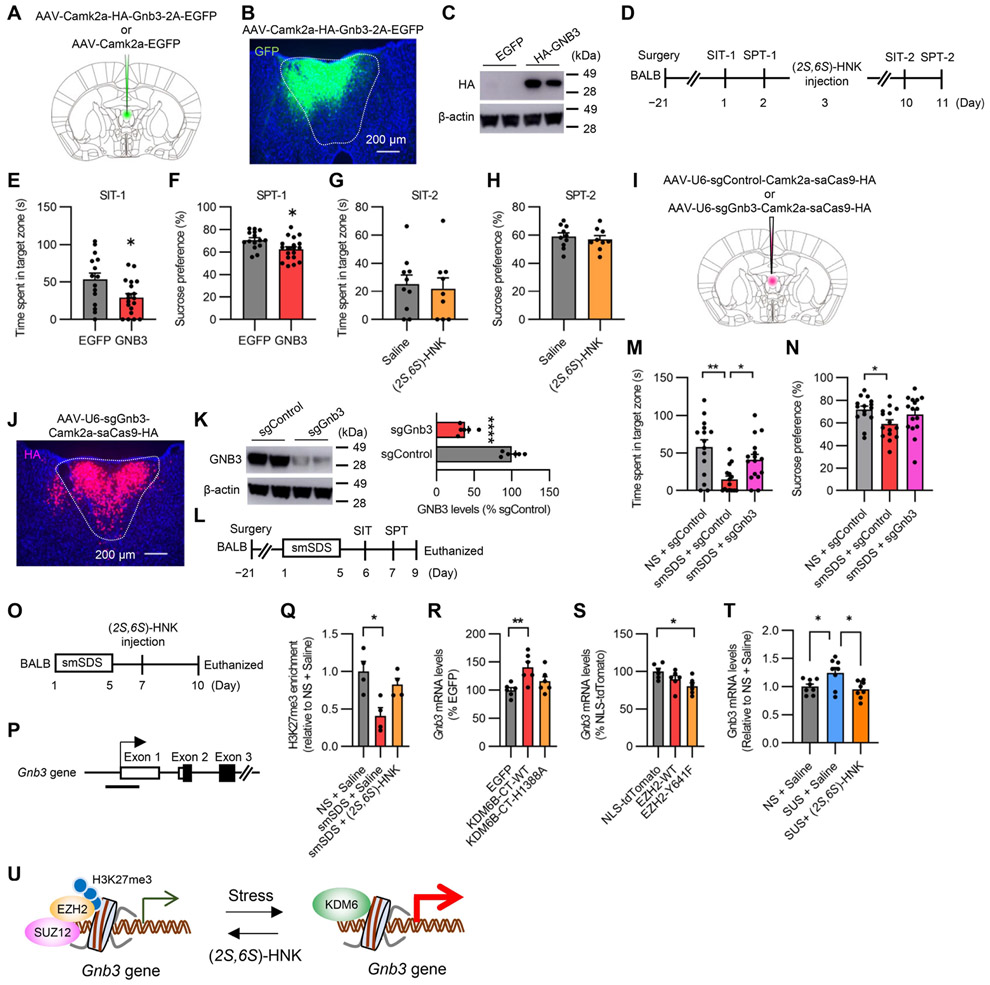

Next, we focused on the Gnb3 gene, encoding G protein beta3, as a modulator of the GPCR signaling (Figures 4G and S6I) because of its potential involvement in clinical depression 39,40. BALB mice were microinjected with AAVs expressing GNB3 and EGFP into the aPVT and tested by SIT and SPT before (SIT-1 and SPT-1) and after (SIT-2 and SPT-2) treatment with (2S,6S)-HNK (Figures 7A-7D). aPVT-specific GNB3 overexpression caused significantly shorter SI time in the SIT and lower sucrose preference in the SPT (Figures 7E and 7F). These behavioral deficits were not rescued by (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figures 7G and 7H). We next investigated the effects of aPVT-specific focal knockdown of GNB3 expression by AAV-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 (Figures 7I-7L). smSDS-exposed GNB3 knockdown mice (smSDS + sgGnb3) did not show decreased SI or sucrose preference, compared to nonstressed control mice (NS + sgControl) (Figures 7M and 7N). These gain- and loss-of-function studies suggest the involvement of GNB3-mediated GPCR signaling in depression and (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant-like actions.

Figure 7. GNB3 regulates behavioral responses to (2S,6S)-HNK and stress.

(A) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(B) Representative image showing GFP expression in the aPVT of mice injected with AAV-HA-Gnb3. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(C) Western blotting showing successful HA-Gnb3 protein overexpression in mice injected with AAV-HA-GNB3.

(D) Experimental design.

(E–H) Time spent in target zone of the SIT-1 (E) and sucrose preference of the SPT-1 (F) and in SIT-2 (G) and SPT-2 (H) after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. n = 15–19 (E and F) and n = 9–10 (G and H) per group.

(I) Schematic of AAV microinjection.

(J) Representative image showing saCas9-HA expression in the aPVT of mice injected with AAV-sgGnb3. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(K) Western blotting showing successful GNB3 protein knockdown in mice injected with AAV-sgGnb3.

(L) Experimental design for Gnb3 knockdown in BALB mice.

(M) Time spent in target zone of the SIT in smSDS mice injected with either AAV-sgControl or AAV-sgGnb3. n = 15–16 per group.

(N) Sucrose preference of the SPT in smSDS mice injected with either AAV-sgControl or AAV-sgGnb3. n = 15–16 per group.

(O) Experimental design for ChIP assay in BALB mice.

(P) Primer set against putative SUZ12/EZH2 binding sites (ENCODE) on the Gnb3 gene indicated by a black bar.

(Q) Levels of H3K27me3 occupancy on the Gnb3 promoter in the aPVT of smSDS-exposed BALB mice or nonstressed (NS) conditions. n = 4 per group.

(R) Levels of Gnb3 mRNA in the aPVT of BALB mice expressing EGFP, KDM6B-CT-WT, or KDM6B-CT-H1388A as shown in Figure 6I. n = 6 per group.

(S) Levels of Gnb3 mRNA in the aPVT of BALB mice expressing Ezh2-WT, Ezh2-Y641F, or NLS-tdTomato as shown in Figure 5K. n = 6 per group.

(T) qPCR quantification of Gnb3 expression in nonstressed and CSDS-exposed susceptible B6 mice seven days after the treatment with (2S,6S)-HNK or saline. n = 8 in each group.

(U) Proposed model for how psychosocial stress and (2S, 6S)-HNK regulate Gnb3 gene expression via KDM6- and Ezh2-dependent epigenetic mechanisms, respectively.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

To investigate whether Gnb3 expression is associated with H3K27me3 levels, we measured H3K27me3 levels at the Gnb3 gene in the aPVT of smSDS-exposed and nonstressed mice injected with (2S,6S)-HNK or saline using a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP assay) (Figures 7O and 7P). smSDS exposure significantly decreased H3K27me3 levels on the Gnb3 gene; this effect was abolished by (2S,6S)-HNK treatment (Figure 7Q). qPCR revealed that the overexpression of KDM6B-CT-WT, but not KDM6B-CT-H1388A, increased Gnb3 mRNA levels in aPVT (Figure 7R); conversely, EZH2 activation reduced Gnb3 mRNA levels (Figure 7S). In addition to BALB mice, CSDS-exposed susceptible B6 mice showed increased Gnb3 mRNA levels, which were normalized by (2S,6S)-HNK (Figure 7T). Together, these results suggest that Gnb3 is a target gene for KDM6B and EZH2 required for (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant-like actions (Figure 7U).

(2S,6S)-HNK inhibits the reactivation of aPVT cells that previously responded to stress

Our behavioral data showed that (2S,6S)-HNK had antidepressant-like effects in repeatedly stressed mice (Figure S1L), but not in naive mice (Figure S1I-S1K), indicating the possibility of the modulatory effects of (2S,6S)-HNK on the modulation of aPVT cells that previously responded to stress. Therefore, we applied genetic targeted recombination in active populations (TRAP) 41,42 to label stress-activated cells in FosTRAP2 mice (Figure 8A and STAR Methods). Immunostaining with GFP (TRAPed cells) and Fos allowed us to determine the proportion of aPVT neurons TRAPed during a tail suspension stress (TSS) of the rTST model that were reactivated during a later TST (negative valence) or chocolate consumption (positive valence) 43 (Event-2). We found that (2S,6S)-HNK treatment significantly decreased the number of TSS-activated, but not chocolate-activated, Fos+ cells (Event-2) in rTST-exposed mice (Event-1; Figures 8B and 8D), without affecting the number of TRAPed GFP-positive cells (Figures 8B and 8C). Similarly, TSS-activated but not chocolate-activated TRAP/Fos double-positive cell counts during Event 2 were significantly decreased in rTST-exposed mice receiving (2S,6S)-HNK (Figure 8E). These results suggest a specific integration of (2S,6S)-HNK-responding cells into the negative valence-associated population within aPVT, which may be associated with antidepressant-like behaviors.

Figure 8. Extrasynaptic GABAARs are requited for (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant-like effects.

(A) Schematic of fosTRAP2 labeling.

(B) Double immunofluorescence staining of GFP and Fos in the aPVT.

(C–E) Quantification of TRAP-GFP labeled cells (C), Fos+ cells (D), and TRAP-labeled cells with Fos- and TRAP-double labeling (Fos+GFP+/GFP+) (E) in the aPVT. n = 8 per group.

(F) Ribo-tag strategy.

(G and H) qPCR quantification of Gabra1, Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd expression in the aPVT of GFP-positive TRAPed cells (relative to saline) (D) and GFP-negative non-TRAPed cells (E). n = 5 pooled samples; each sample was pooled from four mice (n = 20 per group).

(I) Representative traces of the membrane current.

(J) Holding current changes before and after TTX+PTX application. n = 7–8 neurons per group.

(K) Schematic of AAV microinjection into the aPVT of BALB mice.

(L) Representative image showing mCherry expression in the aPVT of BALB mice expressing miR-a4/b2/d. Scale bar, 200 μm.

(M) Experimental design for the Gabra4/Gabrb2/Gabrd knockdown in BALB mice.

(N) Quantification of Gabra1, Gabra4, Gabrb2, Gabrb3, Gabrd, and Gabrg mRNA in the aPVT. n = 6 per group.

(O) Time spent in target zone of the SIT. n = 15–16 per group.

(P) Sucrose preference of the SPT. n = 15–16 per group.

(Q) Proposed model whereby (2S,6S)-HNK drives the sustained antidepressant effects (see Discussion).

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Bar graphs show the mean ± SEM.

(2S,6S)-HNK increases GABAA receptor gene transcription in aPVT cells that previously responded to stress

As mentioned earlier, RNA-seq data revealed the potential role of GABAA receptors signaling in (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant effects. Therefore, we hypothesized that the suppression of reactivation of aPVT cells that previously responded to stress by (2S,6S)-HNK (Figures 8A-8E) could be due to increased GABAAR-mediated inhibitory effects. Therefore, we used the Ribo-tag technique, which enables quantification of translated mRNAs in a target cell population 44. We used the same mice as in Figure 8A, which express EGFP-L10a in stress-activated cells and euthanized them at 7 days after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment to purify mRNAs from GFP-positive TRAPed cells and GFP-negative non-TRAPed cells (Figure 8F). qPCR revealed that the TRAPed fraction (GFP-positive cells) had higher GFP and Slc17a6 (a marker for glutamatergic neurons) expression than the non-TRAPed fraction (GFP-negative cells) (Figures S9), indicating the successful immunoprecipitation of cell-specific RNA from RiboTag-expressing cells. We found significantly upregulated Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd expression by (2S,6S)-HNK in TRAPed cells (Figure 8G), but not in the GFP-negative non-TRAPed cells (Figure 8H). These data suggest that (2S,6S)-HNK increases α4β2δ GABAAR signaling by targeting specific, stress-responsive cells to elicit antidepressant-like behaviors.

(2S,6S)-HNK increases tonic GABAergic inhibition and inhibits smSDS-induced reduction of inhibitory synaptic drive

We investigated the role of α4βδ GABAARs in smSDS-induced KDM6B subcellular localization. We assessed the effects of α4βδ subtype-selective agonist Gaboxadol 45,46 on the subcellular localization of KDM6B in the smSDS model (Figures S10A-S10C). Gaboxadol treatment significantly increased cytoplasmic KDM6B and decreased KDM6B within the nucleus. Accordingly, Gaboxadol treatment significantly reduced Gnb3 expression in the smSDS model (Figure S10D).

In the thalamus, α4βδ GABAARs are expressed peri- or extra-synaptically and mediate a tonic conductance 47,48, which indicates the possible involvement of GABAAR-mediated tonic inhibition in (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained antidepressant effects. Therefore, we assessed the effect of (2S,6S)-HNK on tonic GABAAR-mediated currents by measuring the change in the baseline holding current produced by blocking GABAARs with the GABAAR antagonist, picrotoxin (PTX). Following bath application of the voltage-gated sodium channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX), we observed a tonic GABAergic current, which was increased by subsequent PTX application (Figure 8I). We observed a significantly greater holding current in smSDS-exposed mice receiving (2S,6S)-HNK than in smSDS-exposed mice receiving saline; however, smSDS-exposed mice receiving (2R,6R)-HNK were not significantly different from controls (Figures 8J). These results suggest that (2S,6S)-HNK enhances GABAARs-mediated tonic inhibition.

Furthermore, we measured the excitability, action potential waveform parameters, and membrane properties of aPVT neurons and found no significant effect of smSDS, (2S,6S)-HNK, or (2R,6R)-HNK (Figures S11A-S11P). Post hoc morphological reconstruction revealed fewer dendritic branches of aPVT neurons in smSDS-exposed mice (Figures S11Q-S11U), and the effect was inhibited by HNKs.

Next, we investigated the effect of (2S,6S)-HNK on inhibitory transmission in aPVT 3 days after drug injection (Figures S12A-S12C). We observed a significant reduction in spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current (sIPSC) and miniature IPSC (mIPSC) frequencies in smSDS-exposed mice compared with nonstressed mice (Figure S12C). These IPSC reductions were not observed after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. In contrast, there were no significant effects of smSDS exposure or (2S,6S)-HNK treatment on spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) or miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) (Figures S12D-S12F). Thus, (2S,6S)-HNK normalized smSDS-induced reduction of inhibitory synaptic drive onto aPVT neurons.

We examined the number of inhibitory synapses on aPVT glutamatergic neurons using fibronectin intrabodies generated with mRNA display (FingR) against the inhibitory synaptic protein gephyrin (gephyrin-FingR-GFP), which labels inhibitory synapses without disrupting endogenous proteins and synaptic physiology 44,45. Gephyrin-FingR-GFP signals were significantly higher in (2S,6S)-HNK-treated mice than in saline-treated mice (Figures S12G-S12K), suggesting that (2S,6S)-HNK treatment increases the number of inhibitory synapses on aPVT glutamatergic neurons.

α4βδ GABAARs are required for (2S,6S)-HNK antidepressant-like effects

Finally, we knocked down Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd (which encode the GABAAR α4, β2, and δ subunit, respectively) specifically in aPVT glutamatergic neurons of BALB genetic background mice, and subjected them to smSDS (Figures 8K-8N). We evaluated their antidepressant-like behaviors 3 days (SIT) and 4 days (SPT) after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment and euthanized them 6 days after drug treatment. Although (2S,6S)-HNK treatment significantly increased SI time and sucrose preference in mice expressing control shRNAs, the antidepressant-like behavioral effects of (2S,6S)-HNK were abolished in mice expressing triple-knockdown shRNAs (Figures 8O, 8P). Furthermore, (2S,6S)-HNK treatment did not induce KDM6B nuclear export (Figures S13A and S13B) or reduce Gnb3 mRNA expression in triple-knockdown mice (Figures S13C and S13D). These results suggest that α4βδ GABAARs are critical for (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant action.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered temporal molecular mechanisms underlying the sustained antidepressant effects of (2S,6S)-HNK, and proposed the following concepts: i) (2S,6S)-HNK transiently increases aPVT neuronal activity, which induces the transcriptional activation of Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd genes during the early phase (at 6 h); ii) (2S,6S)-HNK-mediated induction of GABAARs increases tonic inhibition of aPVT glutamatergic neurons during the late phase (>3 days); iii) (2S,6S)-HNK-mediated enhancement of GABAergic inhibitory signaling inhibits the reactivation of previously responsive cells to repeated stress; iv) activation of extrasynaptic GABAARs promotes KDM6 nuclear export, which is replaced by EZH2; and v) EZH2 increases H3K27me3 at Gnb3 to repress its transcription (Figure 8Q). Thus, this study provides a comprehensive understanding of the previously undetermined molecular mechanisms by which (2S,6S)-HNK conveys antidepressant-like behaviors.

Similar to our results, (2S,6S)-HNK, but not (2R,6R)-HNK, has antidepressant-like effects in mice under a chronic corticosterone treatment12. In contrast, (2R,6R)-HNK has stronger antidepressant effects than (2S,6S)-HNK in acute stress models (e.g., learned helplessness, forced swim test) 10, which is in agreement with our data showing that (2R,6R)-HNK was also effective in the acute TST model (Figure S1I-S1K). A recent preclinical study indicated that despite the two distinct changes in neural network activities (Electome Factors) observed in CSDS-exposed susceptible mice, ketamine affects only one, but not both, Electome Factor activity49. Taken together, the antidepressant-like behavioral effects of HNKs may depend on the brain and/or emotional states of the animal models used.

To evaluate the sustained antidepressant-like efficacy of HNKs, we measured SI and SP for the SDS model and immobility time for the rTST model, as these behavioral deficits were persistently observed after repeated stress exposure. However, depression is a highly heterogeneous syndrome13-16; therefore, it would be necessary to further characterize the efficacy of ketamine metabolites on behavioral and physiological responses using multiple paradigms in different animal models of depression. This approach will elucidate for which behavioral manifestations and/or behavioral phenotypes in stressed models (2S,6S)-HNK or (2R,6R)-HNK may be effective and aid in the development of depression subtype-specific pharmacotherapies. Note that a recent classification of clinical depression based on functional connectivity indicated that patients with biotype 4, which exhibits hyperconnectivity in the thalamus and frontostriatal networks, are associated with severe anhedonia and anxiety symptoms 13. Taken together, (2S,6S)-HNK may promote remission from certain subtypes of stress-related psychiatric disorders that exhibit aPVT dysfunction and/or severe anhedonic and anxiety states.

Accumulating evidence demonstrates the roles of PVT in emotion and behavioral regulations, including reward-seeking 50-53, saliency 54, food intake 55,56, fear memory 57,58, sleep and wakefulness 59,60, social behavior 61, stress response 62, avoidance behavior 63, and anxiety- and depression-related behaviors 64-66. Similar to effect of (2S,6S)-HNK on antidepressant behaviors among animal models, PVT-mediated modulation of reward-seeking depends on the emotional state of the animal 50. In addition, in line with previous report showing that PVT recruitment serves to integrate fear circuits at the late time point (>24h) required for long-term maintenance of fear memory 57, aPVT is involved in (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained (>24h), but not rapid, antidepressant-like behaviors. Moreover, we found strong functional connectivity of Fos expression between the aPVT and BNST or nucleus accumbens following (2S,6S)-HNK treatment. These brain regions are associated with chronic stress-induced SI deficits and anhedonia 18,22,67,68. Together, our data suggest that the aPVT is a key node for regulating social and hedonic behaviors.

Although smSDS-exposed BALB mice exhibited reduced baseline Fos levels in the aPVT and pPVT, (2S,6S)-HNK treatment normalized Fos expression levels only in the aPVT (Figure S2). The cell types in the aPVT and pPVT differ transcriptionally, anatomically, and functionally 50,60,69,70. Most pPVT cells express Drd2 (encoding dopamine D2 receptors, D2Rs), whereas aPVT has fewer Drd2-positive cells60,71. Since D2R inhibits adenylyl cyclase as it is coupled to the Gi/o protein, leading to neuronal inhibition 72. Therefore, there is a possibility that although aPVT neurons are transiently activated by (2S,6S)-HNK, Drd2-positive pPVT cells may be inhibited, thus showing no Fos response (Figure 2A-2D).

The mPFC, hippocampus, and lateral habenula (LHb) are well-known brain areas involved in ketamine’s rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects 3,4,9,10,73-78. mPFC neurons innervate the PVT 52,60,61,79 and aPVT neurons project to the mPFC and hippocampus (Figure 2I) 60,80. Another report has shown that the locus coeruleus is a key brain area for the modulation of the inhibitory tone of the PVT, which controls stress responsivity 81. These raise a question of how aPVT neurons integrate mPFC-, hippocampus-, and/or locus coeruleus-mediated circuitry responsible for (2S,6S)-HNK’s sustained antidepressant-like behavioral effects. Although we did not address how (2S,6S)-HNK transiently stimulates aPVT neurons in this study, a previous report suggested that (2S,6S)-HNK does not affect NMDAR and AMPAR function 10. Future in-depth analyses of the circuit-level mechanisms underlying the modulation of aPVT function and its role in sustained antidepression-like behaviors are needed.

The PVT is the target of diverse inhibitory inputs; thus, despite the absence of local interneurons, GABAergic inhibition may play a prominent role in the modulation of PVT function 81. Our data suggest the involvement of extrasynaptic GABAARs in (2S,6S)-HNK’s antidepressant-like effects. In addition, smSDS exposure reduced the frequency of s/mIPSCs and the number of dendritic arbors, suggesting suppression of the release probability of GABAergic synapses at the single synapse level or a decrease in the number of sites by smSDS. These data are consistent with numerous studies indicating that chronic stress induces changes in the inhibitory system that could lead to abnormal behaviors and dendritic reorganization 82. However, further research is needed to address whether (2S,6S)-HNK-mediated enhancement of synaptic inhibitory drive affects extrasynaptic GABAAR function or whether presynaptic and extrasynaptic functions occur independently.

Limitations of the study

Several lines of evidence have found sex differences in response to traditional antidepressants and in depression pathophysiology 20,83,84. Although a systematic review did not find significant sex differences in the therapeutic effects of ketamine in clinical depression 85, future animal studies with female mice are required to generalize our findings. We described the key role of tonic inhibitory currents by (2S,6S)-HNK in the late phase (>3 days), but the detailed molecular mechanisms controlling the transcription machinery for Gabra4, Gabrb2, and Gabrd during the early phase (6h) after (2S,6S)-HNK treatment need to be investigated in the future.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Shusaku Uchida (uchida@med.nagoya-cu.ac.jp).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

The accession number for the raw and processed RNA-seq data reported in this paper is GSE233226.

Lists of DEGs from RNA-seq were deposited on Mendeley at: https://doi.org/10.17632/vdjrhx6j8s.1.

Custom MATLAB codes for the analyses in this study are available from the lead contact upon individual request.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Animals

7- to 8-week-old male C57BL/6J (B6) and BALB/c (BALB) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory Japan, and vGluT2-IRES-Cre mice (vGlut-Cre; JAX stock #016963), Cre-dependent GFP reporter mice (EGFP-L10a; JAX stock #024750), and Fos-2A-iCreER mice (FosTRAP2, JAX stock #030323) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. FosTRAP2 mice were crossed with transgenic mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)–tagged ribosomal protein L10a (EGFP-L10a). Retired breeder CD1 male mice (3- to 5-month-old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory Japan and used as aggressors in the social defeat stress procedure and the SIT. FosTRAP2 mice, which express iCreERT2 under the control of an activity-dependent c-Fos promoter, were bred with GFP-L10a reporter mice; the resulting bitransgenic mice were injected with fast-acting tamoxifen (4-OHT) 43 30 min after being submitted to tail-suspension stress (Event-1) to drive Cre-dependent recombination and induce the expression of a reporter gene (GFP-L10a). This procedure was repeated for five consecutive days (rTST model; Figure 8A). Seven days after the last rTST session, the mice received (2S,6S)-HNK or saline; after 3 days, the mice were subjected again to TST (negative valence), received chocolate consumption (positive valence) 43, or remained in their home cage (Event-2). Ninety minutes after Event 2, the mice were euthanized. For the TRAP study, mice in all groups received a chocolate (1 g of milk chocolate) 1 h before the rTST paradigm for habituation, and mice in the chocolate groups (Event-2) received an additional 0.5 g of chocolate. All experimental mice were housed under controlled temperatures and 12 h light/dark cycles with mouse chow and water ad libitum. The experimental animals except for CD1 mice were 8- to 10-week-old at the time of the experiment. 5- to 8-month-old CD1 mice were used for social defeat stress paradigm. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Kyoto University, and performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Animal Care and Use of Kyoto University.

Methods details

Drug injection

For the systemic administration of (R,S)-ketamine (KET, Daiichi Sankyo Propharma Co., Ltd.; Tokyo, Japan), (2S,6S)-HNK (Sigma-Aldrich, SML1875), and (2R,6R)-HNK (Sigma-Aldrich, SML1873), the drugs were dissolved in 0.9% saline at a concentration of 2 mg/mL and administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) (20 mg/kg).

For intra-aPVT injection, (2S,6S)-HNK was dissolved in 0.9% saline at a concentration of 20 μg/mL just before injection. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and a stainless-steel guide cannula (26 gauge, Plastics One) was implanted into the aPVT (bregma, −0.3 mm anteroposterior, AP; 0 mm mediolateral, ML; −2.7 mm dorsoventral, DV). Seven days after surgery, mice were injected with the compound using a microliter syringe (10 μL, Hamilton) connected by polyethylene tubing to an internal cannula (33 gauge, Plastics One) that projected 1 mm below the guide cannula. The compounds were infused (0.5 μL/hemisphere) at a rate of 0.1 μL/min. After the experiments, we confirmed the location of the injection sites by injecting 0.5 μL of Chicago Sky Blue solution bilaterally, followed by histological analysis of coronal brain slices. Mice that did not receive adequate injection in aPVT were excluded from further analysis.

For the systemic administration of CNO (Toronto Research Chemicals, #C587520), the compound was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted in 0.9% saline to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL or 0.3 mg/mL CNO in 0.5% DMSO solution. The applied doses were 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg for chemogenetic activation (hM3Dq) and inhibition (hM4Di) experiments, respectively.

For the intra-aPVT injection of ANI (FujiFilm Wako Chemicals #013-16863), the compound was dissolved in HCl and diluted with artificial cerebrospinal fluid. A small amount of NaOH was added to raise the pH to approximately 7.4 at a final concentration of 100 μg/μL, and infused into the mouse aPVT (0.5 μL) via a stainless-steel guide cannula as described above.

For intra-aPVT injection of ActD (Tocris #1229), the compound was dissolved in saline at a final concentration of 4 μg/μL and infused into the mouse aPVT (0.5 μL) via a stainless-steel guide cannula as described above.

For the systemic administration of GSK-J4 (Sigma-Aldrich, SML0701), the compound was dissolved in DMSO at a final concentration of 200 mg/mL; this stock solution was stored at −20°C until use. This stock solution was then diluted 1:100 with saline before injection. The final injectable solution contained 2 mg/mL GSK-J4 and 1% DMSO in saline and was administered i.p. (20 mg/kg).

For the systemic administration of Gaboxadol (Tocris #0807), the compound was dissolved in 0.9% saline at a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and administered i.p. (5 mg/kg).

For the systemic administration of 4-OHT (Sigma, Cat# H6278), the compound was dissolved in DMSO at 80 mg/mL by shaking for 5–10 min; this stock solution was stored at −20°C until use. The stock solution was first diluted 1:10 with saline containing 4% Tween 80 and then diluted 1:1 again with 0.9% saline. The final injectable solution contained 4 mg/mL 4-OHT, 2% Tween 80, and 5% DMSO in saline. For TRAPing of activated neural cells, 4-OHT solutions were injected intraperitoneally 30 min after tail-suspension stress. We prepared an aqueous solution of 4-OHT instead of an oily one for slower drug release, to facilitate transient 4-OHT delivery, and reduce the background recombinase 43. Given that the 4-OHT concentration in the mouse brain was highest at 60 min after a single intraperitoneal injection of 4-OHT dissolved in this aqueous solution 43 and that greater Fos expression was observed at 90 min after the tail-suspension stress (Figure 2B), we injected 4-OHT at 30 min after the tail-suspension stress.

Chronic social defeat stress

B6 and vGlut-Cre males were exposed to the CSDS paradigm as previously reported 25,79. On the first day of stress, the experimental mouse was placed in the home cage of the dominant CD1 mouse for 10 min/day. During this time, the experimental mouse was physically attacked by the CD1 aggressor. Following the physical encounter, the mice were separated by a perforated Plexiglas divider; thereafter, the mice remained in continuous sensory contact with the CD1 aggressor for the next 24 h. This session was repeated for 10 consecutive days, and the experimental mice were exposed to a new unfamiliar CD1 aggressor each day. In the nonstressed control group, two experimental mice were introduced in the same social defeat cage but separated by a clear perforated Plexiglas divider for the length of the stress period and rotated daily in a similar manner without being exposed to the CD1 aggressor.

Subchronic and mild social defeat stress

smSDS25,79 is a modified version of CSDS. In this paradigm, a BALB mouse was introduced into the home cage of a dominant CD1 male mouse for 5 min and physically defeated daily over five consecutive days, while the other procedures were the same as those in the CSDS test described above.

Behavioral tests

All behavioral experiments were conducted between 9:00 and 15:00 and performed in a blinded fashion.

Repeated tail-suspension test.

Mice were individually suspended by their tails with a plastic clip 45 cm above the floor in three-walled rectangular compartments. Mouse movements were video recorded, and the duration of immobility (all four limbs stopped struggling or only slight body movement) was manually measured for 6 min. This procedure was repeated for five consecutive days as an induction phase (Figure S1A), and then TST was conducted again as a test phase following drug treatment (indicated time points are shown in each experimental schedule).

Social interaction test.

SIT consists of two sessions: (1) empty session and (2) target session. First, the test mice, subjected to smSDS, were placed in an open arena (42 cm width × 42 cm depth × 42 cm height) with an empty wire cage (10 cm width × 6.5 cm depth × 42 cm height) followed by 3 min to explore the arena. In the target session, a novel CD1 mouse enclosed in a wire cage was placed in the arena, and the procedure was repeated. An empty session and a target session were performed alternatively. Time spent in an area surrounding the wire cage (interaction zone, 24 cm × 14 cm) and in the corner zones (9 cm × 9 cm) opposite the interaction zone was measured automatically using an ANY-maze tracking system (Stoeling). The results are shown as the time spent in the target zone (smSDS model) or as the SI ratio (CSDS model), calculated by dividing the time spent in the target zone in the presence of a CD1 mouse by that spent in the target zone in the absence of the social target.

Sucrose preference test.

Mice were exposed to 1.5% sucrose solution for 24 h to avoid neophobia, followed by water deprivation for 16 h before SPT. Thereafter, mice had ad libitum access for 4 h to two bottles, one containing tap water and another containing a 1.5% sucrose solution. The positions of the water and sucrose bottles (left or right) were switched every 2 h. Each bottle was weighed before and after the test, and the weight difference was considered to indicate the mouse intake from each bottle. The preference for the sucrose solution was expressed as the percentage of sucrose intake relative to the total intake (sum of water and sucrose intakes).

Rotarod test.

The experiment comprised two phases: training (day 1–4) and test phase (day 5). On each training day, five trials (trial time: 3 min) were conducted with an inter-trial interval of 2 min. Mice were individually placed on the rotarod apparatus (Rotarod Treadmill 370, Bio-Medica) and the rotor (3 cm in diameter) was accelerated from 5 to 20 rpm over a period of 3 min. The latency to fall was recorded for each trial. On the test day, mice received intraperitoneal injections of drug or saline and were tested in the rotating rod 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min after injection using the same procedure as in the training days.

Open field test.

Mice were placed individually in the center of an open field apparatus (42 cm width × 42 cm depth × 42 cm height) and allowed 5 min to freely explore. The percentage of time spent in the center area was measured automatically using the ANY-maze video-tracking system (Stoeling).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal administration of Avertin (250 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with cold 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) dissolved in 0.1 M PB. Brains were postfixed for 24 h in 4% PFA at 4°C and cryoprotect for 3 days in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C. The frozen brains were cut into 20 μm coronal sections using a cryostat (Leica) and stored at −20°C in a cryoprotectant solution containing 30% ethylene glycol (v/v), 30% glycerol (v/v), and 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4). Free-floating sections were washed three times in 1 × PBS and blocked in blocking solution (3% normal goat serum, 3% bovine serum albumin, and 0.3% TritonX-100 in PBS) for 1 h. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking in primary antibodies against Fos (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #2250), CaMKIIα (1:5000, Abcam, #ab22609), Cre (1:1000, BioLegend, #908001), H3K27me3 (1:2000, Abcam, #ab6002), NeuN (1:2000, Millipore, #MAB377), HA (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #3724 or 1:1000, Sigma #11867423001), Ezh2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #5246), GFP (1:1000, Nacalai tesque, Inc., #04404-84), RFP (1:1000, Rockland, #200-301-379), Total Histone H3 (1:1000, Abcam, #ab1791), KDM6A (1:500, Abcam, #ab36938), or KDM6B (1:500, Abcam, #ab38113). Sections were washed three times in 1X PBS and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor dyes in blocking solution for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes in 1X PBS, the sections were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs). For antibodies against H4K27me3, Histone H3, Ezh2, KDM6A, and KDM6B, we have adapted antigen retrieval procedures. All images were acquired using a BZ-X800 fluorescence microscope (Keyence) and analyzed using the BZ-X800 analyzer software (Keyence).

For quantification, bilateral cell counts were averaged for 3–4 brain slices per mouse of the IL/PL (bregma 1.98 mm to 1.54 mm), aCC/Acbc/Acbsh/CPu (bregma 1.1 mm to 0.74 mm), LPO/MPA/BNST/VP (bregma 0.26 mm to 0.02 mm), aPVT (bregma −0.22 mm to −0.58 mm), pPVT (bregma −1.7 mm to −2.18 mm), RSG/RSD/LHb/MHb/CeA/BLA/MeA/LH/dCA1/dCA3/dDG (bregma −1.34 mm to −1.94 mm), vCA1/vCA3/vDG (bregma −2.92 mm to −3.28 mm), and VTA (bregma −2.92 mm to −3.16 mm), and the images were background subtracted and thresholded using the Max Entropy function with ImageJ (NIH). Colocalization analysis was performed using CellProfiler software (Broad Institute) 86. To generate an inter-regional Fos correlation matrix, Fos immunoreactive cells were quantified across 27 brain regions (n = 8 per group). Raw count data were averaged for saline-treated animals and subsequently normalized to the saline, (2S,6S)-HNK, and (2R,6R)-HNK data. Averaging and normalization were performed for the 27 brain regions. Then, nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficients were computed for the normalized data set for pairwise comparisons of Fos levels among the 27 brain regions analyzed.

Synaptic density quantification

Image processing and analysis of Gephyrin-GFP clusters were performed using ImageJ software. We divided the number of Gephyrin-GFP clusters by dendrite length to quantify the gephyrin cluster density. To detect Gephyrin-GFP clusters, we first measured the intensity of a background free of Gephyrin-GFP clusters. Clusters with average intensities >2x the values of nearby background regions were selected as gephyrin clusters. Only clusters >0.28 μm2 and dendrites longer than 0.5 μm were considered for analysis.

TUNNEL staining

Apoptotic cells induced by taCasp3-TEVp were detected using a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated uridine 5′-triphosphate-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit (In Situ Cell Death Detection, Merck) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After TUNEL staining, the sections were counterstained with DAPI. Images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope (Keyence BZ-X800).

AAV-mediated gene transfer

The AAV vector plasmids pAAV-EF1a-FLEX-taCasp3-TEVp (a gift from Nirao Shah & Jim Wells, Addgene plasmid #45580)27, pAAV-Camk2a-Cre (a gift from James M. Wilson, Addgene plasmid #105558), pAAV-Syn-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry (a gift from Bryan Roth, Addgene plasmid #44361)87, pAAV-Syn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry (a gift from Bryan Roth, Addgene plasmid #44362)87, pAAV-Syn-DIO-mCherry (a gift from Bryan Roth, Addgene plasmid #50459), and pAAV-EF1A-DIO-gephyrin. FingR-eGFP-CCR5TC (a gift from Xue Han, Addgene plasmid #126217)88 were obtained from Addgene. The AAV vector plasmids pAAV-EF1a-FLEX-tdTomato, pAAV-Camk2a-CreERT2, pAAV-U6-sgControl-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-SaCas9-HA, pAAV-U6-sgEzh2-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-SaCas9-HA, pAAV-Ef1a-Flex-Ezh2-WT-3xHA, pAAV-Ef1a-Flex-Ezh2-Y641F-3xHA, pAAV-EF1a-FLEX-nls-tdTomato, pAAV-EF1a-Flex-EGFP-miKDM6a-miKDM6b, pAAV-EF1a-Flex-EGFP-miScramble1-miScramble2, pAAV-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-NLS-GFP, pAAV-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-NLS-HA-mKDM6B-CT-WT (KDM6B-CT-WT, aa 1144-1682), pAAV-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-NLS-HA-mKDM6B-CT-H1388A, pAAV-Camk2a-HA-Gnb3-2A-EGFP, pAAV-U6-sgGnb3-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-SaCas9-HA, and pAAV-Camk2a-mCherry-shRNA1-shRNA2-shRNA3 were constructed and obtained from VectorBuilder Japan (Kanagawa, Japan). The genomic titer of each virus was determined using qPCR. AAV5-EF1a-FLEX-taCasp3-TEVp (titer: 1.2 x 1013 vector genome (vg)/mL), AAV5-EF1a-FLEX-tdTomato (titer: 1.5 x 1013 vg/mL), and AAV8-Camk2p-EGFP (titer: 6.7 x 1013 vg/mL) were packaged and purified in the Laboratory of Vector Biolabs (Malvern, PA). AAV9-U6-sgControl-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-SaCas9-HA (titer: 7.4 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV9-U6-sgEzh2-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-SaCas9-HA (titer: 8.4 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV9-Camk2a-CreERT2 (titer: 3.8 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Ef1a-Flex-Ezh2-WT-3xHA (titer: 2.4 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Ef1a-Flex-Ezh2-Y641F-3xHA (titer: 1.6 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-EF1a-FLEX-nls-tdTomato (titer: 1.5 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-EF1a-Flex-EGFP-miKDM6a-miKDM6b (titer: 4.3 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-EF1a-Flex-EGFP-miScramble1-miScramble2 (titer: 7.1 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-NLS-GFP (titer: 7.5 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-NLS-HA-mKDM6B-CT-WT (titer: 5.6 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-NLS-HA-mKDM6B-CT-H1388A (titer: 9.7 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Camk2a-HA-Gnb3-2A-EGFP (titer: 4.7 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-U6-sgGnb3-Camk2a (0.4 kb)-SaCas9-HA (titer: 7.2 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Camk2a-mCherry-shGabra4-shGabrb2-shGabrd (titer: 5.2 x 1013 vg/mL), AAV8-Camk2a-mCherry-shRNA1-shRNA2-shRNA3 (titer: 3.6 x 1013 vg/mL), and AAV8-EF1A-DIO-gephyrin. FingR-eGFP-CCR5TC (titer: 3.0 x 1013 vg/mL) were packaged and purified in the Laboratory of VectorBuilder. AAV5-Camk2a-Cre (titer: 1.5 x 1013 vg/mL, Addgene #105558-AAV5), AAV5-Syn-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry (titer: 2.7 x 1013 vg/mL, Addgene #44361-AAV5), AAV5-Syn-DIO-hM4Di-mCherry, (titer: 2.5 x 1013 vg/mL, Addgene #44362-AAV5), and AAV5-Syn-DIO-mCherry (titer: 2.3 x 1013 vg/mL, Addgene #50459-AAV5) were obtained from Addgene.

For AAV injection, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and head-fixed in a stereotaxic apparatus (KOPF). AAV vectors (0.5 μL/hemisphere) were delivered into the aPVT area (bregma, AP: −0.3, ML: 0 mm, DV: −3.7 mm 89) using a glass micropipette and an air pressure injection system (BJ-110, BEX, Japan). The mice were allowed to recover for ≥3 weeks after surgery. At the end of the experiments, mice were euthanized and tissues and/or coronal brain sections were prepared for biochemical and histological analyses as well as to confirm transgene expression. Animals were excluded from the analyses in case of failed AAV-mediated gene transfer in the target regions. Illustrations of AAV-driven transgene expression (in the cell soma or nucleus) and taCasp3-mediated cell ablation efficacy (Cre deficiency) in the PVT are summarized in Mendeley dataset Figure S14.

RNA extraction

Mice were rapidly decapitated, and brain tissue were flash-frozen and stored at –80°C until processing. Specific brain regions were punched out from brain tissue sections (aPVT bregma, AP: −0.3 mm to −0.8 mm). Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Direct-zol RNA Microprep (Zymo research). All RNA samples had A260/A280 values of 1.93–2.02 as measured using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantitative PCR

A total of 100 ng of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). cDNA was stored at −80°C until use. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. PCR cycling conditions were 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C. The quantification of target molecules was performed using the relative quantification method, which calculates the ratio between the amount of each target molecule and a reference molecule in the same sample. Gapdh and b-actin genes served as internal controls. The primer sequences used for qPCR are shown in the Supplemental Information (Mendeley Table S1).

RNA sequencing

RNA-seq was performed as previously reported 25,90. Total RNA integrity was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technology); all samples had RIN values ≥8.1. cDNA libraries were constructed using the SMART-Seq™ v4 Ultra™ Low Input RNA kit (Takara-Bio) and TruSeq RNA Sample Prep kit v2 (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) with a configuration of 2 × 100 bp configuration (Macrogen). Then, sequencing adaptors, low-quality reads, and bases were trimmed using the Trimmomatic-0.38 tool 91. The sequence reads were aligned to the reference mouse genome (mm10) using HISAT2 version 2.1.0 92. After read mapping, StringTie 93 was used for transcript assembly, and the expression profile was calculated for each sample and transcript/gene as the read count. The read counts allocated to each gene and transcript (UCSC version 2013.3.6) were quantified using the Trimmed Mean of the M-value method 94 implemented in the EdgeR package. Differentially expressed genes (DEG) analyses were performed using the Limma–Voom method 95,96. DEG sets were selected when genes were 1.3-fold up/downregulated and the Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P-value (FDR P) for comparisons between the two groups was <0.05. The list of DEGs is provided in Mendeley Tables S2–S4 (https://doi.org/10.17632/vdjrhx6j8s.1). GO analysis at the Molecular Function, Biological Process, and Cellular Component levels and enrichment analysis were performed using the Enrichr platform 28. PPI network analysis was conducted using the Metascape platform 29. The raw sequencing data were deposited in GEO (GSE233226).

ChIP assay

A ChIP assay was performed using the SimpleChIP Enzymatic Chromatin IP kit with magnetic beads according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Cell Signaling) with minor modifications. Dissected aPVT tissues were immediately snap frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until further use. The pooled dissected samples from 8–10 mice were used as one ChIP sample, and a total of four ChIP samples per experimental group were analyzed (n = 36–40 mice per group). Pooled tissues were placed in 1% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature to crosslink the protein–DNA complexes, and fixation was quenched by adding glycine at a final concentration of 0.125 M. The purified nuclear samples were treated with micrococcal nuclease to digest DNA to an average length of 150–900 bp, sonicated to disrupt the nuclear membrane, and finally incubated overnight at 4°C with the antibody against H3K27me3 (Abcam, #ab192985). All assays included normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) but no-antibody immunoprecipitations to control for the specificity of each antibody. Chromatin–antibody complexes were collected with ChIP Grade Protein G Magnetic Beads (Cell Signaling) and sequentially washed with low-salt (3 times) and high-salt (one time) buffers. The antibody-bound chromatin was eluted in 1x ChIP elution buffer (Cell Signaling), followed by reverse cross-linking and protease K treatment. DNA was purified using the DNA purification spin columns in the kit. The purified DNA samples were subjected to qPCR analyses with the Gnb3 promoter-specific primer pair 5′-CCAGTAATCCTCACGGCTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGACCAGAGAAGAGCAGCAC-3′ (reverse) using Gapdh sequences to control for specificity of histone acetylation and transcription. Real-time PCR ChIP data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method and normalized to the input as described previously. The relative ratios of H3K27me3 occupancy on Gnb3 genomic regions between experimental groups are indicated in the figures as previously reported 22.

GFP immunoprecipitation for Ribo-tag

Immunoaffinity purification of ribosomal RNA from aPVT was performed as described previously 90, with minor modifications. For immunoprecipitation, Protein G Dynabeads (Thermo Fischer Scientific) were directly coupled to an anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, ab290) in a total volume of 200 μL of PBST for 30 min at room temperature before being added to the homogenates. Homogenates were prepared as follows: aPVT tissues were rapidly removed and weighed before Dounce homogenization in 1 mL of ice-cold IP buffer [50 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 1% NP-40; 100 mM KCl; 12 mM MgCl2; 0.5 mM DTT; 100 μg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma); 1 mg/mL sodium heparin (Sigma); 1x HALT protease inhibitor EDTA-free (Thermo Fischer Scientific); 0.2 U/μL RNasin (Promega)]. Samples were then centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and the cleared lysate (50 μL) was stored as “Input” control. Supernatants were then added directly to the antibody-coupled Protein G Dynabeads and rotated for 2 h at 4°C. After incubation, beads were magnetically separated and the unbound nuclei were collected in a fresh microcentrifuge tube as the negative fraction (GFP− cell population). Beads (GFP+ cell population) were washed three times with a wash buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 12 mM MgCl2, 300 mM KCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, and 100 μg/mL cycloheximide. To prepare RNA, 500 μL of TRIzol (Thermo Fischer Scientific) was immediately added to the IP fraction and input samples. Total RNA was purified using Direct-zol RNA Microprep (Zymo research), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blot