Abstract

Background:

Titin truncation variants (TTNtvs) are the most common genetic lesion identified in individuals with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a disease with high morbidity and mortality. TTNtvs reduce normal TTN protein levels, produce truncated proteins, and impair sarcomere content and function; but therapeutics targeting TTNtvs have been elusive secondary to TTN’s immense size, the rarity of specific TTNtvs, and incomplete knowledge of TTNtv pathogenicity.

Methods:

We adapted CRISPR activation using dCas9-VPR to functionally interrogate TTNtv pathogenicity and develop a therapeutic in human cardiomyocytes (CMs) and 3-dimensional cardiac microtissues (CMTs) engineered from induced pluripotent stem cell models harboring a DCM-associated TTNtv. We performed guide RNA screening with custom TTN reporter assays, agarose gel electrophoresis to quantify TTN protein levels and isoforms, and RNA-sequencing to identify molecular consequences of TTN activation. CM epigenetic assays were also utilized to nominate DNA regulatory elements to enable CM-specific TTN activation.

Results:

CRISPR activation of TTN using single gRNAs targeting either the TTN promoter or regulatory elements in spatial proximity to the TTN promoter through 3-dimensional chromatin interactions rescued TTN protein deficits disturbed by TTNtvs. Increasing TTN protein levels normalized sarcomere content and contractile function despite increasing truncated TTN protein. In addition to TTN transcripts, CRISPR activation also increased levels of myofibril assembly- and sarcomere-related transcripts.

Conclusions:

TTN CRISPR activation rescued TTNtv-related functional deficits despite increasing truncated TTN levels, which provides evidence to support haploinsufficiency as a relevant genetic mechanism underlying heterozygous TTNtvs. CRISPR activation could be developed as a therapeutic to treat a large proportion of TTNtvs.

Keywords: Titin, Titin truncation variants, dilated cardiomyopathy, CRISPRa, iPS-CM

Introduction

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a morbid condition occurring in 1:250 individuals with inadequate treatments1. DCM is diagnosed when both the cardiac left ventricle is dilated, and contractile function is reduced2. There is a growing evidence base supporting a genetic basis for a large proportion of individuals with DCM3, particularly for inheritance of heterozygous titin (TTN) variants that result in premature TTN protein truncations (TTNtvs; inclusive of reading frameshifting insertions and deletions, premature termination codons and splice site mutations) that occur in up to ~20% of DCM individuals4,5. Similar TTNtvs also increase the risk for other cardiomyopathy types such as peripartum cardiomyopathy6 and acute myocarditis7. Currently, there remain key knowledge gaps regarding how TTNtvs cause these cardiomyopathies that could impact the clinic. In particular, the field neither understands the molecular genetic mechanisms underlying TTNtvs, nor how to target TTN with therapeutics.

Currently, the two leading hypotheses underlying TTNtv pathogenicity include haploinsufficiency and dominant negative/poison-peptide (Fig. 1A). The haploinsufficiency hypothesis purports that the single wildtype TTN allele produces insufficient normal TTN protein levels, while the dominant negative hypothesis implicates a deleterious gain-of-function such as by toxic truncated TTN protein aggregation or through disturbance of normal TTN function by competitive sarcomere integration of truncated TTN poison peptides. Previous studies have utilized different experimental methodologies to support either haploinsufficiency8,9 or the dominant negative model4,5,10, or the likely contribution of both mechanisms11.

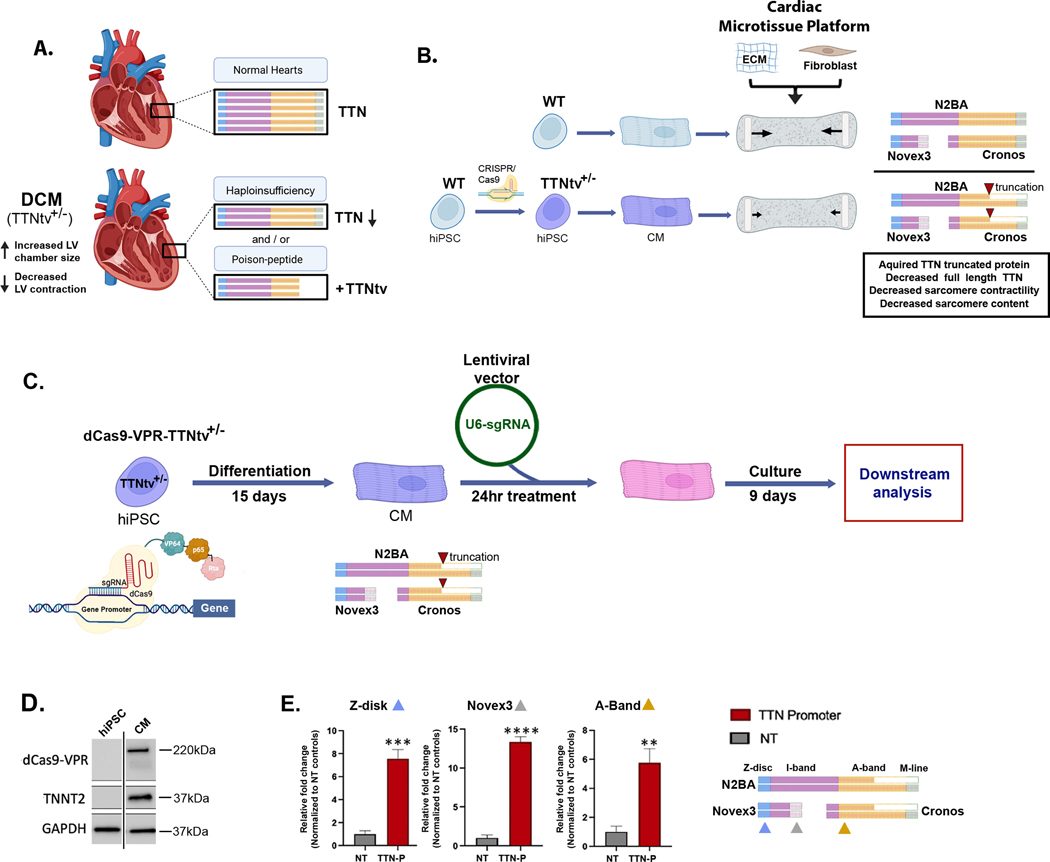

Figure 1. Developing CRISPR transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) to reverse TTNtv-related pathophysiology and molecular consequences.

(A) TTNtvs cause dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a disorder defined by changes in left ventricular (LV) contraction and size, in association with reduced TTN protein quantities and lengths suggesting haploinsufficiency and/or poison peptide mechanisms, respectively.

(B) Human iPS-differentiated cardiomyocytes (CMs) CRISPR-engineered to contain an isogenic heterozygous (+/−) truncation variant at proline residue 22582 exhibit diminished contractile function (arrow length proportion to contractile function) in microtissues and changes in TTN protein levels and lengths recapitulating phenotypic consequences observed in DCM human hearts11. Abundant TTN protein isoforms expressed in CMs are N2BA, Novex3 and Cronos, which variably express exons encoding Z-disk, I-band, A-band and M-line residues.

(C) General overview of CRISPRa in TTNtv+/− CMs that utilizes a nuclease dead Cas9 fused to VP64, p65 and Rta (dCas9-VPR) targeted to gene promoters by single guide RNAs to enable transcriptional activation. These dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs have dCas9-VPR knocked into the TNNT2 locus to provide a method for CM-specific dCas9-VPR expression and following transduction with lentiviral vectors encoding single gRNAs targeted to gene promoters, can be utilized to study the functional consequences of CRISPRa in a DCM context.

(D) Immunoblot from iPSC and iPS-CM lysates probed for antibodies to dCas9-VPR, TNNT2, and GAPDH demonstrating CM-specific expression of cleaved dCas9-VPR and cleaved TNNT2 with GAPDH as loading controls.

(E) Quantitative PCR analysis of TTN mRNA levels using domain-specific primers (see arrow heads for Z-disk (blue), Novex3 (gray) and A-band (yellow) sites) after lentiviral transduction of a gRNA targeting the TTN N2BA promoter (TTN-P) or non-targeting (NT) controls in dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs demonstrates transcriptional activation of splice isoforms encompassing Z-disk, Novex3 and A-band TTN transcripts.

Data are mean ± SD; significance for comparison was assessed by Students T-test with Welch correction and defined by P≤0.01 (**), P≤0.001 (***), and P≤0.001 (****).

Studying TTN has been challenging owing to its immense size of ~3–4 MDa spanning four structural domains from the sarcomere Z-disc to M-line (Fig. S1A), and its molecular complexity including 363 exons (“Meta” transcript ENST00000589042) that are variably spliced resulting in multiple isoforms12. Recently, biomimetic 3-dimensional TTNtv cardiac microtissue (CMT) models composed of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (CMs) have been developed that exhibit DCM phenotypes including diminished contractile function and sarcomere content resembling features observed in TTNtv humans (Fig. 1B)8,11,13. Moreover, TTN protein analyses from TTNtv CM samples have demonstrated molecular consequences of TTNtvs including reduced normal TTN protein levels and production of abundant truncated TTN proteins. Precise knowledge of how these changes in TTN quantities and lengths cause cardiomyopathy remains incompletely understood, but truncated TTN protein has been recently shown to integrate into the sarcomere and impair its assembly11. Similar TTNtv-induced changes in TTN quantities and lengths have been observed by recent in vivo studies of human cardiac specimens obtained from DCM individuals9,14, thus providing additional validation for the utility of TTNtv CM and CMT models for assessing disease mechanisms and treatment responses. Despite these TTNtv disease models, developing therapeutic approaches for TTNtvs continues to be challenging secondary to both TTN’s immense size precluding most gene replacement methods, and the rarity of individual TTNtvs that limit the feasibility of direct TTNtv correction strategies such as with CRISPR nucleases as recently reported11.

Here, we developed CRISPR transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) in heterozygous TTNtv CM and CMT models to establish the feasibility and therapeutic efficacy of increasing TTN levels in a DCM model, and to functionally interrogate TTNtv pathophysiology and genetic mechanisms. CRISPRa utilizes an RNA-guided Cas9 that is ‘nuclease dead’ (dCas9), such that it does not cleave DNA, and has been reprogrammed to function as a transcriptional activator by fusion to three transcriptional activation domains; VP64, p65, and Rta, generating dCas9-VPR. When specifically guided to endogenous gene promoters by a guide RNA (gRNA), dCas9-VPR has been shown to exhibit the capacity for activating mRNA levels by up to >1000x in cell lines and >100x in vivo15,16. In our study, we performed a gRNA screen by targeting the TTN promoter in dCas9-VPR expressing TTNtv CMs, and identified gRNAs and experimental conditions to increase TTN protein levels to normal levels. We determined TTN protein levels and isoforms using custom TTN reporter assays and vertical agarose gel electrophoresis (VAGE)17 followed by western blotting (VAGE WB). We measured CM sarcomere content enabled by microcontact printing technology and confocal imaging, and transcriptomes by RNA-sequencing and computational analyses. Finally, we performed 3-dimensional chromatin assays to reveal TTN enhancer elements to enable cell-type specific TTN CRISPRa.

Methods

No animals were used in this study. All human studies were approved by an institutional review committee and all subjects gave informed consent. Statistical tests and sample sizes are provided in each figure legend. Expanded Methods are provided in the Supplemental Materials. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

See Supplemental Materials for expanded methods.

Results

Introducing CRISPR transcriptional activators into TTNtv CMs

To determine the feasibility and functional consequences of TTN transcriptional activation, we studied a human iPSC model harboring a heterozygous (+/−) DCM-associated TTNtv reported previously11. The TTNtv is a single nucleotide deletion variant engineered using CRISPR technology that results in premature TTN truncation within the A-band structural domain (frameshift after proline-22582; exon 276 in ENST00000591111). We studied an A-band TTNtv because of its high DCM pathogenicity10. For transcriptional activation, we adapted CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) using a programmable nuclease-dead Cas9 derived from S. pyogenes fused to a tripartite activator complex composed of VP64, p65 and Rta (dCas9-VPR; Fig. 1C and sequence provided in Table S2)18. Previous work has established that dCas9-VPR directed to gene promoters using single guide RNAs (gRNAs; sequence provided in Table S1) enables strong transcriptional activation in vitro18 and in vivo19. Because TTN is a myocyte-specific factor, we prioritized an approach to express dCas9-VPR exclusively in CMs under the control of the cardiomyocyte-specific troponin T2 (TNNT2) promoter20 (Fig. S1B). Using CRISPR and a homology-directed repair template (Fig. S1C), we knocked-in the coding region of dCas9-VPR proximal to the TNNT2 stop codon and linked via a T2A peptide that induces ribosome skipping to separate troponin T2 and dCas9-VPR proteins during translation21 (Fig. S1B), as we have done previously in CMs22. This CRISPRa iPSC model generated in TTNtvA+/− background is referred to as dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/−.

To study CRISPRa functionality in CMs differentiated from dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− iPSCs, we used an established directed differentiation protocol using sequential Wnt modulation23 followed by metabolic CM enrichment24. As predicted given the CM specificity of the endogenous TNNT2 promoter20; dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs, but not parental iPSCs, expressed dCas9-VPR and troponin T2 at the expected molecular weights (Fig. 1D). We next generated a lentivirus encoding a U6 promoter driven gRNA that is both designed to bind to the ASCL1 promoter and has been studied in other cell lines18, but not in CMs that do not normally express ASCL1. Nine days following lentiviral transduction of the ASC1L gRNA or a non-targeting (NT) control gRNA into dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs, quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of polyadenylated transcripts demonstrated a ~15x increase in ASCL1 mRNA levels relative to NT controls (Fig. S1D). Thus, dCas9-VPR expressed from the modified TNNT2 locus and directed to CM-inactive gene promoters like ASCL1 activates transcription.

As TTN mRNA is extremely large (TTN N2BA mRNA size = 104kb; NM_001256850) and levels are high in CMs, we next tested whether dCas9-VPR designed to bind to TTN promoter could increase TTN transcript levels above baseline levels in CMs. We made a lentivirus to deliver a single gRNA targeting the TTN promoter (‘TTN-P’ is also denoted as ‘TTN-182’ because the distance from the center of the gRNA spacer sequence to the TTN transcriptional start site (TSS) is 182 nucleotides) or an NT gRNA control, and then transduced dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs. Polyadenylated TTN mRNA transcripts were quantified using qPCR by primers recognizing transcript sequences encoding Z-disc, Novex3, and A-band residues as these regions are differentially included across TTN splice isoforms. We observed that TTN transcripts encoding Z-disk residues were activated ~8x, Novex3 residues by ~13x and A-band residues by ~6x relative to NT gRNA controls (Fig. 1E). We did not test Cronos-specific transcripts due to its alternative promoter site located near the I-/A-band junction25. In summary, these results demonstrate that CRISPRa can activate genes like TTN that are extremely large and expressed at high levels in CMs, as well as ASCL1 that is not expressed in CMs.

TTN CRISPRa targeting the TTN promoter normalizes TTN levels.

As TTNtvs reduce full length TTN (‘FL’ is defined here as N2BA TTN at the expected molecular weight of ~3700 kDa) by ~50% in CMs8,11 we hypothesized that increasing FL TTN by ~2x could restore functional deficits if the predominant genetic mechanism were haploinsufficiency. To assess whether TTN CRISPRa could achieve ~2x increase in FL TTN protein in CMs, we first developed an assay to quantify FL TTN protein in dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs. To do this, we engineered a fluorescent TTN protein reporter by fusing tdTomato to the carboxyl-terminus of the single normal TTN allele (TTN-tdTomato; Fig. S2A) with CRISPR-facilitated homology-directed repair using a plasmid DNA template (Fig. S2B) as described previously11. Using flow cytometry analysis of TTN-tdTomato CMs, we could quantify single CM TTN protein levels inclusive of isoforms expressing M-line residues (i.e., N2BA, N2B and Cronos) by proxy of tdTomato signal intensity (Fig. S2C). Using lentiviral transduction, we screened 18 single gRNAs with spacer motifs centered +88 to −524 nucleotides relative to the TTN N2BA TSS (Fig. 2A; Table S3) that also overlapped CM open chromatin as assessed by ATAC-seq (Fig. 2B). Nine days after transduction, we observed increased TTN-tdTomato signal up to 2x compared to NT controls (Fig. 2C). We also assessed the lentiviral dosage- and time-dependence of TTN activation by testing TTN-tdTomato levels at low MOI (5) and high MOI (10), as well as 9- and 12-days post transduction with TTN-124 gRNA. TTN-124 dosage- and time-dependently activated TTN-tdTomato intensity to up to ~2.5x control levels (Fig. S2D and 2D). Taken together, these results reveal multiple single gRNAs that increase TTN levels to normal and above normal levels in dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs.

Figure 2: TTN promoter gRNA screening in TTN reporter CMs to enable TTN transcriptional activation.

(A) TTN promoter single gRNA nomenclature reflects the distance between the TTN TSS to the middle of the gRNA protospacer.

(B) ATAC-seq peak analysis of TTN N2BA promoter from four CM samples. N2BA transcript is NM_001256850) and coordinates are shown above the peaks.

(C) Employing a TTN-tdTomato fluorescent reporter, single gRNAs targeting the TTN promoter normalized to non-targeting (NT) controls were screened as an indicator of TTN protein levels following TTN transcriptional activation.

(D) Studying TTN-tdTomato reporter activity at 9 and 12 days post lentiviral transduction with TTN-124 gRNA normalized to NT reveals time-dependent and progressive enhancement of TTN protein levels up to ~2.5x.

(E) VAGE immunoblot results obtained from CM lysates probed for TTN protein isoforms using an Anti-Z TTN antibody demonstrates that TTN promoter activation increases the protein levels of N2BA, truncated N2BA (N2BAtv) and Novex3 TTN isoforms. Prior to VAGE, replicates were normalized to actinin levels.

(F) Quantification of VAGE immunoblot results from (E) using TTN-P normalized to NT gRNA.

(G) VAGE immunoblot results obtained from CM lysates probed for TTN protein isoforms using an Anti-M TTN antibody demonstrates that TTN promoter activation increases the protein levels of N2BA, but not Cronos that utilizes a distinct promoter. Prior to VAGE, replicates were normalized to actinin levels.

(H) Quantification of VAGE immunoblot results from (G) using TTN-P normalized to NT gRNA.

(I) Model of CRISPR transcriptional activation targeting the TTN promoter to increase TTN mRNA transcripts and TTN protein isoform levels including N2BA, N2BAtv and Novex3.

Data are mean±SD; significance for pairwise comparison was assessed by Students T-test with Welch correction and defined by P≤0.01 (**), and P≤0.001 (****). Multiple comparisons in Fig. 2C were assessed by Brown-Forsythe one-way ANOVA test with consecutive Dunnett’s correction, defined by P<0.05 (*), P≤0.01 (**), P≤0.001 (***), and P≤0.001 (****). Two-way ANOVA followed by Fishers Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was performed for Fig. 2D and defined by P<0.05 (*), P≤0.01 (**), P≤0.001 (***), and P≤0.001 (****)

To confirm TTN-tdTomato screening results and determine isoform-specific effects of TTN CRISPRa, we quantified TTN proteins using vertical agarose gel electrophoresis (VAGE)17 followed by western blotting (VAGE WB) using antibodies recognizing Z-band and M-line TTN epitopes as done previously11. After first normalizing lysates to total actinin levels (Fig. S2E), we observed between 2–3x increases in N2BA, truncated TTN and Novex3 isoforms relative to NT controls (Fig. 2E, F), while Cronos TTN was not increased (Fig. 2G, H). This pattern of TTN isoform activation could likely be explained by the shared TSS among N2BA, truncated TTN and Novex3 isoforms; while Cronos TTN is regulated by a distinct promoter located within the TTN gene near nucleotides encoding residues at the I-/A-band junction as previously reported25. Taken together, these results demonstrate that TTN CRISPRa applied to dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs normalizes N2BA TTN protein to levels described in wildtype CMs, but also increased expression of truncated TTN and Novex3 (Fig. 2I).

Truncated TTN has been previously observed to misfold and aggregate in vivo9, and increasing TTN levels particularly truncated TTN could be toxic. To screen for toxicity, we examined the activation status of the unfolded protein response (UPR)26,27, which has been previously implicated in cardiomyopathy pathogenesis28,29. To test for UPR activation after targeting the promoter region (TTN-P) of TTN through CRISPRa in dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs, we quantified protein levels of UPR factors30 including ATF6α, phosphorylated EIF2α and IRE1α using immunoblotting lysates (Fig. S2F, G). TTN CRISPRa samples relative to controls showed no change in the levels of these UPR markers. Taken together, these results demonstrate that TTN CRISPRa using dCas9-VPR and single gRNAs directed to the TTN N2BA promoter increase TTN mRNA and protein levels without evidence for UPR activation despite increasing truncated TTN levels.

TTN CRISPRa increases sarcomere and myofibril assembly transcripts

To evaluate the molecular consequences of TTN CRISPRa at the transcriptomic level beyond direct effects on TTN transcripts, we employed RNA sequencing and computational analyses from samples obtained from biological triplicates of TTN-P and NT control CMs. Principal component analysis of samples demonstrated the distinct separation of TTN-P from NT biological replicates (Fig. 3A). Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis (cutoffs = Padj<0.01 and log2FC ≥1 or ≤−1) demonstrated 1,357 downregulated (Table S6) and 576 upregulated (Table S7) transcripts, while most transcripts were unchanged (Fig. 3B). Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis of the significantly downregulated (Fig. 3C, D) and upregulated (Fig. 3D, E) transcripts revealed changes in biological processes, pathways, and components. We observed that GO terms involved in “contractile fiber”, “muscle structure development” and “circulatory system development” were enriched in the upregulated gene sets (Fig. 3E). Plotting fold change heat maps of complete gene sets within GO terms including “cardiac myofibril assembly”, cardiac muscle contraction”, “sarcomere organization”, sarcomere “M-line”, “I-band/Z-disk” and “A-band” (Fig 3F, Table S8) illustrated the generalized upregulation of these factors after TTN CRISPRa. GO term enrichment analysis of the downregulated transcripts revealed functions in “ion transport” and “intrinsic component of plasma membrane” (Fig. 3C). To summarize RNA-sequencing results, TTN CRISPRa not only increases TTN transcript levels, but also numerous factors implicated in sarcomere assembly, structure and organization.

Figure 3: Transcriptomic consequences of TTN transcriptional activation.

(A) Principal component analysis plot of RNA sequencing data obtained from biological CM triplicates treated with TTN-P or NT gRNA as controls.

(B) Pie chart summarizes differential gene expression (DGE) analysis following TTN transcriptional activation. DGE parameters included a false discovery rate-adjusted P value (Padj) cutoff <0.05, which identified a total of 8219 genes. Of these, 7.01% were upregulated (Log2 fold change (FC) ≥1) and 16.52% were downregulated (Log2 FC≤−1), while most were unchanged.

(C-E) Volcano plot and Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis of the downregulated (blue; Log2FC ≤ −1, Padj<0.05; Table S6) and the upregulated (red; Log2FC ≥ 1, Padj<0.05,; Table S7) gene transcripts upon TTN transcriptional activation using TTN-P relative to NT gRNA controls.

(F) Fold change heat maps of all gene transcripts within GO terms related to sarcomere structure and function reveals generalized upregulation (Table S8 for gene lists) including factors involved in cardiac myofibril assembly (GO: 0055003), cardiac muscle contraction (GO: 0060048), sarcomere organization (GO: 0045214), M-line (GO: 0031430), I-band (GO: 0031674), Z-disk (GO: 0030018), and A-band (GO: 0031672).

TTN CRISPRa leveraging TTN regulatory elements to enable CM-specific activation

Transcriptional activation of inactive genes could have adverse consequences particularly for genes encoding extremely large proteins like TTN that are prone to misfolding31 and aggregation9. To minimize this, we sought to develop a CM-specific approach for TTN transcriptional activation because dCas9 has pioneering capacity32 to bind and activate transcription from inactive promoters. To enable CM-specific TTN CRISPRa, we hypothesized that TTN regulatory elements like enhancers that are in spatial proximity to the TTN N2BA promoter through CM-specific 3-dimensional (3D) chromatin looping33 could function as landing pads for dCas9-VPR. To identify candidate TTN DNA regulatory elements, we utilized a combination of epigenetic assays including Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq)34, histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) chromatin immunoprecipitation with DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq)35 and RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) Chromatin Interaction Analysis by Paired-End Tag Sequencing (ChIA-PET)36. We utilized ATAC-seq for enhancer fine mapping, as well as ChIP-seq and ChIA-PET to identify active chromatin in 3D physical proximity to the TTN N2BA promoter. Three TTN DNA regulatory elements (denoted as E1-E3 Fig. 4A, S3A-C) looped to the TTN N2BA promoter in CMs but not parental iPSCs (Fig. 4A), and overlapped H3K27ac peaks. To test if dCas9-VPR programmed to bind to E1-E3 using single gRNAs could activate FL TTN protein levels in CMs (Fig. 4B), we designed single gRNAs that are predicted to recognize DNA sequences within 250 base pairs from the center of E1-E3 elements (Fig. S3A-C; Table S4). dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs were transduced with lentiviruses delivering E1-E3 single gRNAs, and TTN-tdTomato signal intensity was measured by flow cytometry. We observed activation of TTN-tdTomato intensity with E1-E3 gRNAs (Fig. 4C), which we confirmed by VAGE-WB analyses. To additionally confirm the specificity of TTN activation by enhancer element targeting, we also designed and screened a single gRNA targeting control (TC) that recognized a region upstream of the TTN N2BA promoter, but neither looped to the N2BA promoter nor overlapped with an H3K27ac peak. The TC gRNA treatment did not activate TTN levels (Fig. 4C). Similar to TTN N2BA promoter gRNAs (Fig. 2E, F), E1-E3 single gRNAs increased expression of N2BA TTN, truncated TTN as well as Novex3 (Fig. 4D), after normalizing to the total actinin levels (Fig. S3D). We also attempted to activate TTN in iPS cells through targeting enhancer sequences identified in iPS-CMs; however, this failed to activate TTN expression levels above controls as assayed via qPCR (Fig. S3E).Taken together, these results demonstrate that CRISPRa directed to three CM-specific TTN DNA regulatory elements can activate TTN protein through CM-specific 3d chromatin interactions (Fig. 4E), thus enabling CM-specific TTN activation.

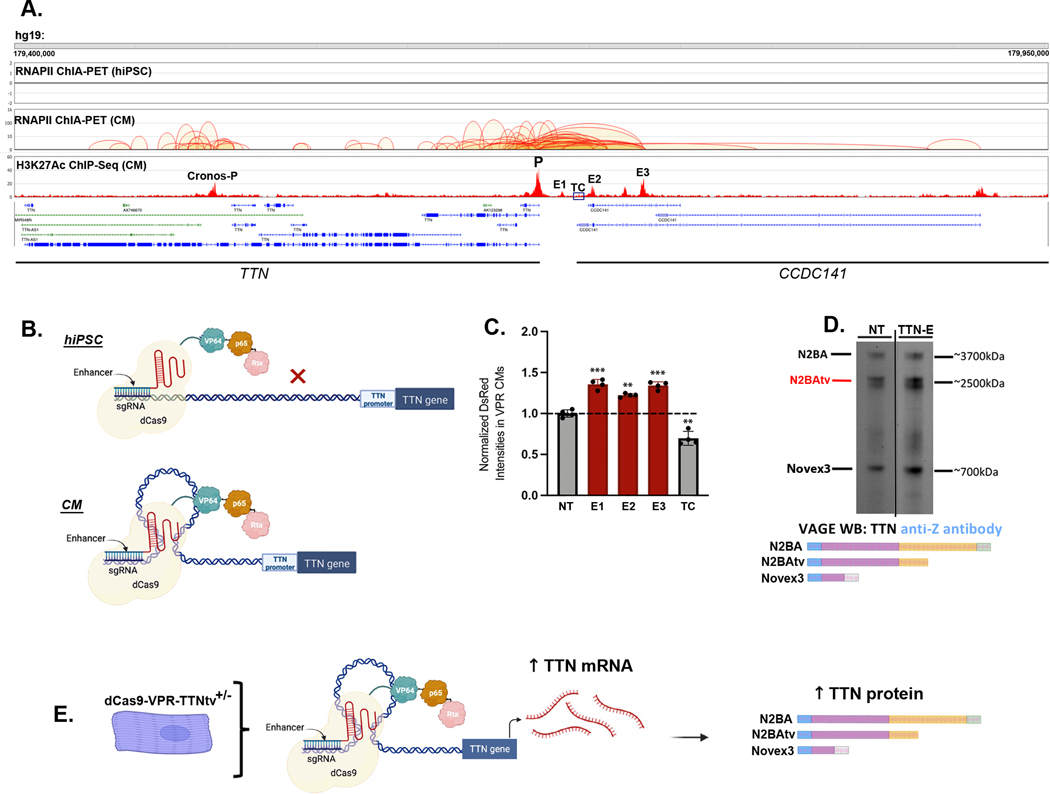

Figure 4: TTN transcriptional activation through targeting TTN regulatory elements.

(A) TTN enhancer elements (E1-E3) are localized upstream of the TTN transcriptional start site (TSS) in CMs, and physically interact with the TTN TSS as demonstrated by DNA-DNA looping revealed by RNAPII ChIA-PET in CMs, but not human iPSCs (note that no looping is evident to the TTN TSS in iPSCs). E1-E3 are also characterized by H3K27ac peaks using ChIP-seq in CMs. Targeting control (TC) was chosen as a control as it demonstrated neither DNA-DNA looping nor H3K27ac peaks in CMs.

(B) Model depicting how CM-specific DNA-DNA contacts may enable dCas9-VPR to physically access the TTN TSS and provide TTN transcriptional activation exclusively in CMs, but not iPSCs and likely other cell types.

(C) Employing a TTN-tdTomato fluorescent reporter, single gRNAs targeting E1-E3 elements and normalized to non-targeting (NT) controls were screened as an indicator of TTN protein levels following TTN transcriptional activation.

(D) VAGE immunoblot of TTN protein isoforms probed with Anti-Z TTN antibodies demonstrates an increase in protein levels of N2BA, N2BAtv and Novex3 TTN isoforms after TTN enhancer element activation.

(E) Model of CRISPR transcriptional activation targeting TTN regulatory elements to increase TTN mRNA transcripts and TTN protein isoform levels including N2BA, N2BAtv and Novex3.

Data are mean±SD; significance for multiple comparisons were assessed by Brown-Forsythe one-way ANOVA test with consecutive Dunnett’s correction, defined by P≤0.01 (**) and P≤0.001 (***).

TTN CRISPRa restores sarcomere content and contractility deficits

As reductions in sarcomere content and contractility are functional consequences of TTNtvs in CMs8,11,13, we next sought to study how TTN CRISPRa influenced these functional parameters. To determine sarcomere content, we transduced dCas9-VPR-TTNtv+/− CMs with TTN-P or NT gRNAs, and replated CMs onto 2000 μm fibronectin rectangles (7:1 aspect ratio) as described previously to optimize sarcomere organization and maturity37,38. Micropatterned CMs were next fixed and immunostained with an anti-sarcomere antibody (anti-TTN). CM sarcomere area was quantified using confocal microscopy and a custom ImageJ script (Fig. 5A). We observed that TTN CRISPRa using TTN-P gRNA increased average CM sarcomere area relative to NT gRNA controls (Fig. 5B), as well as average CM surface area (Fig. 5C). To gain insights into the functional parameters, we quantified contractility after TTN CRISPRa using custom biomimetic 3-dimensional CMTs (Fig. 5D) as described previously11,39. We observed that TTN CRISPRa using TTN-P gRNA increased CMT twitch force relative to NT gRNA controls (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5: TTN transcriptional activation restores TTNtv-induced sarcomere content and contractility deficits.

(A) Representative confocal images of CMs after TTN transcriptional activation using a TTN-P or NT gRNA as control. The sarcomere was stained using Anti-Z TTN antibody with DAPI co-stain for DNA. Note that CMs were patterned with fibronectin PDMS stamps to control cell shape and promote maturation.

(B) Quantification of sarcomere content per cell after TTN transcriptional activation.

(C) Quantification of CM surface area after TTN transcriptional activation.

(D) General overview of a 3-dimensional cardiac microtissue (CMT) assay to enable contractility (twitch force) measurements within a biomimetic context. CMTs are composed of CMs, human cardiac fibroblasts and an extracellular matrix (ECM) slurry, and twitch force is measured using cantilever displacement analysis at 1 Hz pacing. White arrows denote direction of cantilever displacement with twitch.

(E) TTN transcriptional activation using TTN-P increased CMT twitch force relative to NT gRNA as a control.

(F) Model to summarize that CRISPRa using dCas9-VPR targeted to TTN regulatory elements or promoters using single gRNAs restores changes in contractile function, sarcomere content and protein defects. As increasing TTN protein levels restores TTNtv-related dysfunction despite increasing truncated TTN protein levels, haploinsufficiency may be the predominant genetic mechanism for TTNtvs.

Data are mean±SD; significance for pairwise comparison was assessed by Students T-test with Welch correction and defined by P<0.05 (*) and P≤0.01 (**).

To study diastolic parameters after TTN CRISPR activation, we quantified resting tension and observed a significant increase with TTN CRISPRa (Fig. S3F), complementing twitch force measurements. In addition, TTN CRISPRa resulted in decreased systolic time (Fig. S3G), whereas diastolic time (Fig. S3H) and shortening velocity (Fig. S3I) were increased. Taken together, we conclude that TTN activation in TTNtv+/− CMTs led to both an increase in systolic and diastolic force production.”

It has been reported that the phosphorylation of TTN can lead to changes in its stiffness40. To gain insights into the overall phosphorylation status of TTN, we used the Pro-Q Diamond Phosphoprotein Gel Stain and observed a proportional increase in phosphorylation status with CRISPRa (Fig. S3J-K). We conclude that overall changes in TTN phosphorylation are concordant with changes in TTN levels. Taken together, we determined that TTN CRISPRa rescues sarcomere content and CMT contractility deficits secondary to a DCM-associated TTNtv (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, these functional improvements support the model that haploinsufficiency is the predominant genetic mechanism underlying TTNtvs, and TTN CRISPRa and likely other methods to augment TTN protein levels could be a therapeutic for other DCM-associated TTN variants.

Discussion

The principal finding of our study is that TTN transcriptional activation rescues functional deficits secondary to a heterozygous DCM-associated TTNtv. Thus, normal contractile function depends on the precise regulation of TTN levels and demonstrates haploinsufficiency of the wildtype TTN allele as a relevant genetic mechanism underlying TTNtvs. In addition, this study nominates CRISPRa and other methods to increase TTN levels as therapeutic candidates that could be applicable to a large proportion of DCM individuals who carry pathogenic TTN variants that diminish TTN protein levels.

Here, we employed human CM and biomimetic 3-dimensional CMT models harboring a pathogenic TTNtv that resembles the most common inheritable risk factor for DCM10 as well as a growing list of other cardiomyopathies defined by reduced contractile function6,7. Our experiments were motivated by recent engineering of dCas9-VPR as a strong transcriptional activator in human cells18,19, and previous work demonstrating reductions in TTN protein levels across DCM-associated TTNtvs both in vitro and in vivo9,11. Rather than pursuing TTN gene replacement strategies that are not currently feasible due to TTN’s immense size or exon skipping that could disrupt normal TTN functions41, we employed CRISPRa leveraging the endogenous TTN locus to increase TTN protein levels by treating DCM models with a Cas9-based transcriptional activator paired with single gRNAs that could be packaged into contemporary gene delivery vectors42. While TTN activation also enhanced truncated TTN levels given the current inability to specifically activate the wildtype TTN allele, we observed reversal of the major phenotypic consequences of TTNtvs including diminished contractile function and sarcomere content. This result is consistent with a previous study in which we observed that while TTNtvs produce truncated TTN proteins, contractile function did not return to normal levels after truncated TTN ablation, therefore suggesting alternative or combinatorial mechanisms11. We also speculate that truncated TTN activation could exhibit less toxicity in vivo, as truncated TTN in the human and mouse heart has been shown to be less abundant relative to wildtype TTN14,43 unlike the ~1:1 ratio we observe in CMs (Fig. 2). In addition, we could not identify changes in UPR activation status after truncated TTN activation, which is consistent with previous results demonstrating no changes between untreated TTNtv and control models11. In summary, while we observed no cytotoxicity with TTN activation, future studies will be essential to comprehensively determine the safety of TTN transcriptional activation and to identify more precise methods, such as allele specific TTN activation.

To characterize the molecular and structural consequences of TTN activation, we employed RNA sequencing and sarcomere quantification, respectively. In addition to TTN mRNA levels, TTN transcriptional activation also resulted in increased levels of numerous other transcripts involved in sarcomere structure and assembly processes. Given that TTN-directed gRNAs have spacer sequences that do not match promoter sequences upstream of these other transcripts, it is likely that increasing TTN levels only indirectly regulates transcript abundance such as through changes in mechanotransduction signaling. Moreover, TTN is a known binding partner for several signaling factors including ERK44 and calmodulin45 that may mediate the observed transcriptomic changes with TTN activation. In parallel with activation of sarcomere transcripts, we also observed increased sarcomere content suggesting that TTN levels are a determinant of sarcomere content in part through transcriptomic mechanisms. RNA sequencing also provided an unbiased assessment of cytotoxicity, as gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed transcripts did not reveal cytotoxicity terms.

For improving the specificity of TTN transcriptional activation with a goal to minimize the potential of adverse consequences of TTN expression in non-CM cell types, we leveraged epigenetic assays to identify TTN regulatory elements in CMs. Because 3-dimensional enhancer-promoter interactions can bring cell type-specific enhancer sequences into close physical proximity to promoters, we tested whether dCas9-VPR could be programmed to bind to CM-specific TTN regulatory elements, and to subsequently recruit RNA polymerase II to the TTN promoter to increase TTN mRNA and protein levels. To do this, we utilized epigenetic assays including ChIA-PET using antibodies to RNA polymerase II to identify CM-specific TTN enhancer-promoter interactions (Fig. 4A). Relative to iPSCs that exhibited no looping to the TTN promoter, we observed CM-specific looping to at least three regulatory elements that were also decorated with H3K27ac, a marker of active enhancers35. We confirmed robust TTN protein activation using single gRNAs recognizing sequences overlapping these three regulatory elements, therefore providing a blueprint to achieve CM-specific TTN transcriptional activation. Beyond improving the cell type specificity of TTN transcriptional activation, future studies will be essential to develop allele specific TTN transcriptional activation approaches such as leveraging genetic polymorphisms in TTN regulatory elements that could be used to design single gRNAs specifically recognizing the wildtype TTN allele. Through specifically activating the wildtype TTN allele, toxicity related to truncated TTN activation would be expected to be minimized.

As somatic cardiomyocyte genome activation using CRISPRa could provide a transformative treatment for DCM individuals harboring a large proportion of TTNtvs that diminish TTN levels through haploinsufficiency, there are important limitations including challenges with CRISPRa delivery to cardiac tissue and the requirement for persistent expression to continuously activate TTN levels. Other recent methods could be employed to activate TTN such as Prime Editing46 or Base Editing47 to either insert new enhancer elements or generate activating missense mutations in existing TTN regulatory elements, respectively. Our study has notable limitations including the use of human iPSC-derived CMs that are not as mature as adult human cardiomyocytes48. To improve maturation, we utilized biomimetic CMT assays that exhibit improved sarcomere expression39 relative to previous models8, and microcontact printing to control CM shape to improve sarcomere maturation38. Nonetheless, maturation differences could impact the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, this study has been performed in heterozygous P22582fs models in which we observe that haploinsufficiency is the dominant TTNtv mechanism since overcoming reduced TTN levels reverses functional deficits. Other TTN mutations particularly missense mutations could cause DCM through other mechanisms such as poison-peptide/dominant negative. Despite these limitations, CM and CMT models can provide a powerful tool to reveal the pathophysiology and therapeutic targets for DCM-associated TTN variants.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is New?

We engineered human cardiomyocyte models to enable CRISPR transcriptional activation in a Titin truncation (TTNtv) mutation model of dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).

Human cardiomyocyte and microtissue assays revealed that TTN transcriptional activation using dCas9-VPR and custom guide RNAs reversed TTN haploinsufficiency; as well as contractility, transcriptomic and sarcomere content deficits.

We developed a genome editing therapeutic using CRISPR technology to restore TTN protein levels that could be applicable to a large proportion of DCM individuals.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Inheritance of TTNtvs are a prevalent cause of DCM.

Some TTNtvs increase DCM risk through a haploinsufficiency mechanism.

A CRISPR therapeutic enables reversal of TTNtv-related haploinsufficiency and could be developed to treat a large proportion of DCM individuals.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tiffany Prosio (The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine) for expertise in flow cytometry studies and Qianru Yu (The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine) for technical assistance with confocal imaging studies. Artwork was assisted by BioRender.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (U01HL156349, HL165220 and HL142787 to J.T.H.; R35GM119465 to J.C., and R01HL141086 to M.J.G) and Washington University Institute of Materials Science and Engineering (to M.J.G.).

Disclosures

J. Travis Hinson receives sponsored research unrelated to this work from Kate Therapeutics and Tevard Biosciences, and serves on the scientific advisory board of Kate Therapeutics. Dr. Hinson has previously received unrelated consulting fees from Alnylam and BioMarin.

Footnotes

All other authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the work presented here.

References

- 1.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: the complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:531–547. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershberger RE, Jordan E. Dilated Cardiomyopathy Overview. In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, eds. GeneReviews((R)). Seattle (WA); 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Japp AG, Gulati A, Cook SA, Cowie MR, Prasad SK. The Diagnosis and Evaluation of Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2996–3010. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AM, Ware JS, Herman DS, Schafer S, Baksi J, Bick AG, Buchan RJ, Walsh R, John S, Wilkinson S, et al. Integrated allelic, transcriptional, and phenomic dissection of the cardiac effects of titin truncations in health and disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:270ra276. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herman DS, Lam L, Taylor MR, Wang L, Teekakirikul P, Christodoulou D, Conner L, DePalma SR, McDonough B, Sparks E, et al. Truncations of titin causing dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:619–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goli R, Li J, Brandimarto J, Levine LD, Riis V, McAfee Q, DePalma S, Haghighi A, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, et al. Genetic and Phenotypic Landscape of Peripartum Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021;143:1852–1862. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lota AS, Hazebroek MR, Theotokis P, Wassall R, Salmi S, Halliday BP, Tayal U, Verdonschot J, Meena D, Owen R, et al. Genetic Architecture of Acute Myocarditis and the Overlap With Inherited Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2022;146:1123–1134. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.058457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinson JT, Chopra A, Nafissi N, Polacheck WJ, Benson CC, Swist S, Gorham J, Yang L, Schafer S, Sheng CC, et al. HEART DISEASE. Titin mutations in iPS cells define sarcomere insufficiency as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. Science. 2015;349:982–986. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fomin A, Gartner A, Cyganek L, Tiburcy M, Tuleta I, Wellers L, Folsche L, Hobbach AJ, von Frieling-Salewsky M, Unger A, et al. Truncated titin proteins and titin haploinsufficiency are targets for functional recovery in human cardiomyopathy due to TTN mutations. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabd3079. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd3079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schafer S, de Marvao A, Adami E, Fiedler LR, Ng B, Khin E, Rackham OJ, van Heesch S, Pua CJ, Kui M, et al. Titin-truncating variants affect heart function in disease cohorts and the general population. Nat Genet. 2017;49:46–53. doi: 10.1038/ng.3719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano R, Ghahremani S, Zimmerman T, Legere N, Thakar K, Ladha FA, Pettinato AM, Hinson JT. Reading Frame Repair of TTN Truncation Variants Restores Titin Quantity and Functions. Circulation. 2022;145:194–205. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hinson JT. Molecular genetic mechanisms of dilated cardiomyopathy. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2022;76:101959. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2022.101959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chopra A, Kutys ML, Zhang K, Polacheck WJ, Sheng CC, Luu RJ, Eyckmans J, Hinson JT, Seidman JG, Seidman CE, et al. Force Generation via beta-Cardiac Myosin, Titin, and alpha-Actinin Drives Cardiac Sarcomere Assembly from Cell-Matrix Adhesions. Dev Cell. 2018;44:87–96 e85. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAfee Q, Chen CY, Yang Y, Caporizzo MA, Morley M, Babu A, Jeong S, Brandimarto J, Bedi KC Jr., Flam E, et al. Truncated titin proteins in dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabd7287. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abd7287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou H, Liu J, Zhou C, Gao N, Rao Z, Li H, Hu X, Li C, Yao X, Shen X, et al. In vivo simultaneous transcriptional activation of multiple genes in the brain using CRISPR-dCas9-activator transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:440–446. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0060-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gemberling MP, Siklenka K, Rodriguez E, Tonn-Eisinger KR, Barrera A, Liu F, Kantor A, Li L, Cigliola V, Hazlett MF, et al. Transgenic mice for in vivo epigenome editing with CRISPR-based systems. Nat Methods. 2021;18:965–974. doi: 10.1038/s41592-021-01207-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warren CM, Krzesinski PR, Greaser ML. Vertical agarose gel electrophoresis and electroblotting of high-molecular-weight proteins. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:1695–1702. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chavez A, Scheiman J, Vora S, Pruitt BW, Tuttle M, E PRI, Lin S, Kiani S, Guzman CD, Wiegand DJ, et al. Highly efficient Cas9-mediated transcriptional programming. Nat Methods. 2015;12:326–328. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoger E, Carroll KJ, Iyer LM, McAnally JR, Tan W, Liu N, Noack C, Shomroni O, Salinas G, Gross J, et al. CRISPR-Mediated Activation of Endogenous Gene Expression in the Postnatal Heart. Circ Res. 2020;126:6–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farza H, Townsend PJ, Carrier L, Barton PJ, Mesnard L, Bahrend E, Forissier JF, Fiszman M, Yacoub MH, Schwartz K. Genomic organisation, alternative splicing and polymorphisms of the human cardiac troponin T gene. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1247–1253. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donnelly MLL, Luke G, Mehrotra A, Li X, Hughes LE, Gani D, Ryan MD. Analysis of the aphthovirus 2A/2B polyprotein ‘cleavage’ mechanism indicates not a proteolytic reaction, but a novel translational effect: a putative ribosomal ‘skip’. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1013–1025. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettinato AM, Yoo D, VanOudenhove J, Chen YS, Cohn R, Ladha FA, Yang X, Thakar K, Romano R, Legere N, et al. Sarcomere function activates a p53-dependent DNA damage response that promotes polyploidization and limits in vivo cell engraftment. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109088. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, Zhu K, Hazeltine LB, Bao X, Hsiao C, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:162–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tohyama S, Hattori F, Sano M, Hishiki T, Nagahata Y, Matsuura T, Hashimoto H, Suzuki T, Yamashita H, Satoh Y, et al. Distinct metabolic flow enables large-scale purification of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zou J, Tran D, Baalbaki M, Tang LF, Poon A, Pelonero A, Titus EW, Yuan C, Shi C, Patchava S, et al. An internal promoter underlies the difference in disease severity between N- and C-terminal truncation mutations of Titin in zebrafish. Elife. 2015;4:e09406. doi: 10.7554/eLife.09406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glembotski CC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;101:975–984. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feyen DAM, Perea-Gil I, Maas RGC, Harakalova M, Gavidia AA, Arthur Ataam J, Wu TH, Vink A, Pei J, Vadgama N, et al. Unfolded Protein Response as a Compensatory Mechanism and Potential Therapeutic Target in PLN R14del Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021;144:382–392. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang S, Binder P, Fang Q, Wang Z, Xiao W, Liu W, Wang X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the heart: insights into mechanisms and drug targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:1293–1304. doi: 10.1111/bph.13888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oslowski CM, Urano F. Measuring ER stress and the unfolded protein response using mammalian tissue culture system. Methods Enzymol. 2011;490:71–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385114-7.00004-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borgia MB, Borgia A, Best RB, Steward A, Nettels D, Wunderlich B, Schuler B, Clarke J. Single-molecule fluorescence reveals sequence-specific misfolding in multidomain proteins. Nature. 2011;474:662–665. doi: 10.1038/nature10099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barkal AA, Srinivasan S, Hashimoto T, Gifford DK, Sherwood RI. Cas9 Functionally Opens Chromatin. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fullwood MJ, Wei CL, Liu ET, Ruan Y. Next-generation DNA sequencing of paired-end tags (PET) for transcriptome and genome analyses. Genome Res. 2009;19:521–532. doi: 10.1101/gr.074906.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. ATAC-seq: A Method for Assaying Chromatin Accessibility Genome-Wide. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2015;109:21 29 21–21 29 29. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2129s109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Frampton GM, Sharp PA, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21931–21936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li G, Fullwood MJ, Xu H, Mulawadi FH, Velkov S, Vega V, Ariyaratne PN, Mohamed YB, Ooi HS, Tennakoon C, et al. ChIA-PET tool for comprehensive chromatin interaction analysis with paired-end tag sequencing. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clippinger SR, Cloonan PE, Greenberg L, Ernst M, Stump WT, Greenberg MJ. Disrupted mechanobiology links the molecular and cellular phenotypes in familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:17831–17840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1910962116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro AJ, Ang YS, Fu JD, Rivas RN, Mohamed TM, Higgs GC, Srivastava D, Pruitt BL. Contractility of single cardiomyocytes differentiated from pluripotent stem cells depends on physiological shape and substrate stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:12705–12710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508073112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohn R, Thakar K, Lowe A, Ladha FA, Pettinato AM, Romano R, Meredith E, Chen YS, Atamanuk K, Huey BD, et al. A Contraction Stress Model of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy due to Sarcomere Mutations. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;12:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loescher CM, Hobbach AJ, Linke WA. Titin (TTN): from molecule to modifications, mechanics, and medical significance. Cardiovasc Res. 2022;118:2903–2918. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvab328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gramlich M, Pane LS, Zhou Q, Chen Z, Murgia M, Schotterl S, Goedel A, Metzger K, Brade T, Parrotta E, et al. Antisense-mediated exon skipping: a therapeutic strategy for titin-based dilated cardiomyopathy. EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:562–576. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matharu N, Rattanasopha S, Tamura S, Maliskova L, Wang Y, Bernard A, Hardin A, Eckalbar WL, Vaisse C, Ahituv N. CRISPR-mediated activation of a promoter or enhancer rescues obesity caused by haploinsufficiency. Science. 2019;363. doi: 10.1126/science.aau0629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gramlich M, Michely B, Krohne C, Heuser A, Erdmann B, Klaassen S, Hudson B, Magarin M, Kirchner F, Todiras M, et al. Stress-induced dilated cardiomyopathy in a knock-in mouse model mimicking human titin-based disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chuderland D, Seger R. Protein-protein interactions in the regulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Mol Biotechnol. 2005;29:57–74. doi: 10.1385/MB:29:1:57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gautel M, Castiglione Morelli MA, Pfuhl M, Motta A, Pastore A. A calmodulin-binding sequence in the C-terminus of human cardiac titin kinase. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:752–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, Chen PJ, Wilson C, Newby GA, Raguram A, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. 2019;576:149–157. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaudelli NM, Komor AC, Rees HA, Packer MS, Badran AH, Bryson DI, Liu DR. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017;551:464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karbassi E, Fenix A, Marchiano S, Muraoka N, Nakamura K, Yang X, Murry CE. Cardiomyocyte maturation: advances in knowledge and implications for regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:341–359. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0331-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinson JT, Chopra A, Lowe A, Sheng CC, Gupta RM, Kuppusamy R, O’Sullivan J, Rowe G, Wakimoto H, Gorham J, Burke MA, Zhang K, Musunuru K, Gerszten RE, Wu SM, Chen CS, Seidman JG and Seidman CE. Integrative Analysis of PRKAG2 Cardiomyopathy iPS and Microtissue Models Identifies AMPK as a Regulator of Metabolism, Survival, and Fibrosis. Cell Rep. 2016;17:3292–3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng R, Manring H, Papoutsidakis N, Albertelli T, Tsai N, See CJ, Li X, Park J, Stevens TL, Bobbili PJ, Riaz M, Ren Y, Stoddard CE, Janssen PM, Bunch TJ, Hall SP, Lo YC, Jacoby DL, Qyang Y, Wright N, Ackermann MA and Campbell SG. Patient mutations linked to arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy enhance calpain-mediated desmoplakin degradation. JCI Insight. 2019;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.