Abstract

Background:

The sequelae of stoke, including the loss and recovery of function, are strongly linked to the mechanisms of neuroplasticity. Rehabilitation and non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) paradigms have shown promise in modulating corticomotor neuroplasticity to promote functional recovery in individuals post-stroke. However, an important limitation to these approaches is that while stroke recovery depends on the mechanisms of neuroplasticity, those mechanisms may themselves be altered by a stroke.

Objective:

Compare Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)-based assessments of efficacy of mechanism of neuroplasticity between individuals post-stroke and age-matched controls.

Methods:

Thirty-two participants (16 post-stroke, 16 control) underwent an assessment of mechanisms of neuroplasticity, measured by the change in amplitude of motor evoked potentials elicited by single-pulse TMS 10–20 minutes following intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS), and dual-task effect (DTE) reflecting cognitive-motor interference (CMI). In stroke participants, we further collected: time since stroke, stroke type, location, and Stroke Impact Scale 16 (SIS-16).

Results:

Although there was no between-group difference in the efficacy of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity mechanism (p=0.61, η2=.01), the stroke group did not exhibit the expected facilitation to TMS-iTBS (p=.60, η2=.04) that was shown in the control group (p=.016, η2=.18). Sub-cohort analysis showed a trend toward a difference between those in the late-stage post-stroke and the control group (p=0.07, η2=.12). Within the post-stroke group, we found significant relationships between TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity and time since stroke onset, physical function (SIS-16), and CMI (all rs >|.53| and p-values<0.05).

Conclusions:

In this proof-of-principle study, our findings suggested altered mechanisms of neuroplasticity in post-stroke patients which were dependent on time since stroke and related to motor function. TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity assessment and its relationship with clinical functional measures suggest that TMS may be a useful tool to study post-stroke recovery. Due to insufficient statistical power and high variability of the data, generalization of the findings will require replication of the results in a larger, better-characterized cohort.

Keywords: Mechanism of neuroplasticity, Transcranial magnetic stimulation, iTBS, Functional capacity, Motor function, Stroke

1. Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of adult-onset disability, affecting ~80 million individuals worldwide (Johnson et al., 2019). Motor deficits are present in ~80% of individuals in the acute stage, and ~40% in the chronic stage (Cramer et al., 1997). Personalized rehabilitation interventions (e.g., physical and occupational therapy) represent the gold-standard for promoting motor recovery post-stroke (Johnson et al., 2019). However, more than half of individuals who recover from a stroke continue to sustain significant impairments that greatly affect their activities of daily life (Benjamin et al., 2017). Thus, there is a clear need to optimize existing rehabilitation interventions and seek novel therapeutic approaches. Neuromodulatory interventions using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), either in isolation or combined with conventional rehabilitation interventions, have emerged as a promising strategy to mitigate functional impairments post-stroke (French et al., 2007; Hao et al., 2013; Pollock et al., 2014). These proof-of-principle studies highlight the strong potential of neuromodulation as an adjunctive therapy, but also the challenges to integrating these approaches in mainstream clinical care. Specifically, the outcomes of these interventions are highly variable due in part to heterogeneity in etiology, severity, and clinical presentation of stroke as well as lack of standardized interventions and the incomplete understanding of mechanisms of functional gains post-stroke (Plow et al., 2016).

Neuroplasticity is central to motor functional recovery after a stroke. Neuroplasticity can be defined as a change in neural structure and function in response to experience, event or stimuli. Importantly, neuroplasticity has been suggested as the main mechanism responsible for functional recovery that occurs both spontaneously and also as a result of rehabilitation and neuromodulation interventions (Cramer, 2008; Hara, 2015). However, an important limitation to these approaches is that the intrinsic mechanisms of neuroplasticity may be altered by a stroke. Thus, evaluating the efficacy of neuroplastic mechanisms in individuals with stroke could help account for some of the variability in outcomes after existing rehabilitation therapies, and serve as a prognostic indicator of monitor response.

The efficacy of neuroplastic mechanisms can be assessed noninvasively in the motor cortex by evaluating the brain’s response to single-pulse-TMS following a neuromodulatory protocol such as intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) (Huang et al., 2005). Stimulation of motor cortex with iTBS can induce a potentiation of MEP responses, and the extent of iTBS-induced modulation of MEPs from baseline has been demonstrated to represent cortical neuroplastic mechanisms (Oberman, 2010; Pascual-Leone et al., 2011; Suppa et al., 2016; Wischnewski & Schutter, 2015). Corticomotor reactivity can be measured as the average amplitude of motor evoked potentials (MEPs) elicited by single-pulse TMS. The modulation of MEPs by iTBS has been shown to be NMDA receptor-dependent and to resemble synaptic mechanisms of long-term potentiation (LTP) (Huang et al., 2005, 2007). Importantly, the modulation of MEPs by TMS-iTBS does not represent a direct measure of neuroplasticity. Neither LTP-like response is a paradigm to assess synaptic neuroplasticity. The TMS-iTBS assess the underlying “mechanisms of neuroplasticity” as a substrate of LTP-like response. This TMS-iTBS approach has been used to demonstrate how the efficacy of neuroplastic mechanisms may decline with age (Freitas et al., 2011) and may be impacted in neuropsychiatric conditions, including traumatic brain injury (Tremblay et al., 2015) and type-2 diabetes mellitus (Fried et al., 2016).

We aimed to compare TMS-based assessments of the efficacy of mechanism of neuroplasticity in individuals after a stroke and a control group matched by age, gender and physical activity level. We hypothesized that mechanisms of neuroplasticity, as assessed by TMS-iTBS would vary in the course of stroke recovery, and likely to be affect by sequalae components of stroke including the time since stroke and functional status. Thus, as a first approximation, in a cross-sectional study, we predicted that iTBS-induced modulation of MEPs would be blunted in individuals post-stroke when compared to a control group matched by age, gender and physical activity level. Further, within the stroke group, we hypothesized that TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity would be related with the time since stroke and functional and clinical post-stroke outcomes. Thus, we predicted that greater (more normal) TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity response would be correlated with less time since stroke onset and greater functional capacity, such as higher scores on physical function (e.g., hand function and mobility) and better dual-task performance (e.g., ability to perform two concurrent tasks, such as walking while performing a mental task).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional, case-control study, and collected neurophysiologic and behavioral data from thirty-two individuals who participated in research at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine between May 2015 to October 2019. We included 16 post-stroke patients who were recruited in the Miami AHA-Bugher Clinical study (Table 1 shows the description of stroke cases) (Koch et al., 2020). Inclusion criteria specific to this analysis were adults: 1) aged >18 years with a history of recent stroke (<1.5 years since stroke onset); 2) with modified Rankin Scale <4 at hospital discharge 3) who were ambulatory (ability to walk ≥10 meters); and 4) sedentary prior to stroke onset (defined as <75 minutes of vigorous or 150 minutes of moderate activity per week). Additional TMS-specific inclusion criteria included voluntary hand activation on at least one upper extremity and no contraindications to TMS (Rossi et al., 2021b). The control group consisted of 16 individuals with no prior history of stroke, who were group matched to the stroke group by age, gender and physical activity level, and were cognitively unimpaired (MoCA score ≥ 24); and had no history of neurologic or psychiatric conditions. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation and all forms and procedures were approved by the local institutional review board. Study data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Table 1.

Description of the stroke cases.

| ID | Age, years | Gender | MoCA | mRS | Time since stroke onset, days | Stroke location | Stroke origin | SIS-16 | NIHSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| 01 | 24 | Female | 26 | 1 | 111 | Cortical | I | 71 | 1 |

| 02 | 64 | Male | 20 | 1 | 282 | Cortical | I | 79 | 0 |

| 03 | 75 | Male | 22 | 1 | 341 | Cortical | I | 70 | 2 |

| 04 | 67 | Female | 20 | 2 | 125 | Subcortical | I | 56 | 4 |

| 05 | 63 | Female | 28 | 3 | 32 | Subcortical | I | 46 | 2 |

| 06 | 46 | Male | 22 | 3 | 167 | Cortical | I | 64 | - |

| 07 | 59 | Male | 11 | 3 | 146 | Subcortical | I | 76 | 2 |

| 08 | 55 | Male | 24 | 2 | 26 | Cortical | I | 59 | 1 |

| 09 | 54 | Female | 17 | 1 | 86 | Subcortical | I | 72 | 1 |

| 10 | 68 | Male | 23 | 1 | 140 | Subcortical | I | 75 | 1 |

| 11 | 57 | Female | 28 | 2 | 264 | Subcortical | I | 76 | 1 |

| 12 | 53 | Male | 24 | 3 | 45 | Subcortical | I | 58 | 7 |

| 13 | 60 | Female | 20 | 3 | 261 | Subcortical | I | 55 | 5 |

| 14 | 40 | Male | 22 | 2 | 520 | Subcortical | ICH | 60 | 3 |

| 15 | 51 | Female | 27 | 1 | 66 | Subcortical | I | 69 | 1 |

| 16 | 82 | Male | 20 | 3 | 58 | Subcortical | ICH | 32 | 3 |

Abbreviations: MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS=modified Rankin Scale; SIS-16=Stroke Impact Scale; NIHSS=The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; I=ischemic; ICH=intracerebral hemorrhage.

2.2. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Assessment

2.2.1. Participant and TMS setup

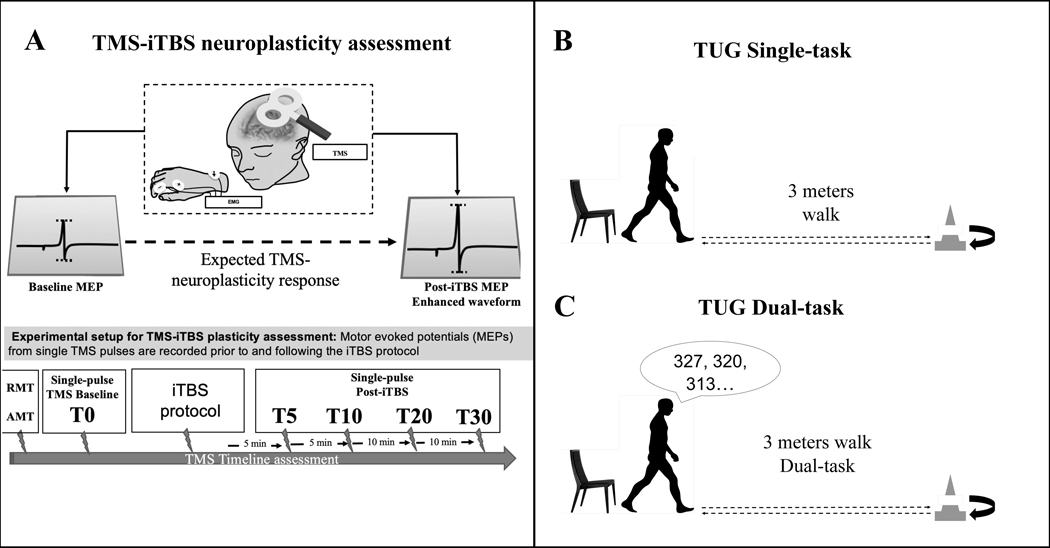

All participants completed assessments of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity mechanisms, and functional performance (TUG single and dual-task) (Figure 1). All study parameters followed the current guidelines for the safe application of TMS recommended by the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (Rossi et al., 2021a). TMS targeted the hand representation of primary motor cortex in the dominant hemisphere (control) or the contralesionally hemisphere (post-stroke). TMS procedures were otherwise consistent for all participants. Participants were seated in a chair with their upper extremities resting on a pillow in a neutral position. TMS was targeted to the hand representation of the primary motor cortex in the dominant hemisphere (healthy participants) or the contralesionally hemisphere (post-stroke participants). TMS pulses were delivered using a static-cooled handheld MagPro MCF-B65 figure-of-eight coil (outer diameter: 75 mm/3.0 in) connected to a MagPro X100 stimulator (MagVenture A/S, Farum, Denmark). The TMS coil was held tangentially to the participant’s head, with the handle oriented 45° relative to their mid-sagittal axis to induce a biphasic (anterior-posterior—posterior-anterior) intracranial current. MEPs were recorded using surface electrodes applied to the first dorsal interosseous (FDI) in a belly-tendon montage with a ground electrode on the ulnar styloid process. Electrodes were connected to a PowerLab 4/25T data acquisition device (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). EMG data epochs (100 ms pre-trigger to 500 ms post-trigger) were digitized at 1 kHz and amplified with a range of ±10 mV (band-pass filter 0.3–1000 Hz), and peak-to-peak MEP amplitude of the non-rectified signal was calculated on individual waveforms using LabChart 8 software (ADInstruments).

Figure 1. TMS and TUG Assessment.

Notes: A. TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity assessment.

B. TUG Single-task.

C. TUG Dual-task assessment.

2.2.2. Single-pulse TMS procedures

Single TMS pulses were applied to identify the motor ‘hotspot’—the coil position that consistently elicited the largest MEPs with a visible contraction of the FDI—and determines motor thresholds. We recorded the resting motor threshold (RMT) corresponded to the minimum intensity to elicit MEPs of at least 50 microvolts, and the active motor threshold of (AMT) under active contraction of 10–20% maximum voluntary activation (5/10 MEPs of at least 200 microvolts). Live EMG was monitored in order to maintain hand relaxation throughout the experiment. An inter-pulse interval was automatically randomized (jitter 5–6 seconds) to avoid train effects.

2.2.3. TMS-iTBS procedures

The assessment of mechanisms of neuroplasticity was performed using TMS-iTBS (Figure 1A). We defined the metric of cortical neuroplasticity mechanisms as the iTBS-induced modulation of MEPs from baseline levels (Oberman, 2010; Pascual-Leone et al., 2011; Suppa et al., 2016; Wischnewski & Schutter, 2015). Parameters of baseline corticomotor reactivity (single-pulse TMS), iTBS and variance-normalization procedures used in this study have been reported in detail (Chang et al., 2016; Gomes-Osman et al., 2017). In summary, cortical reactivity was defined as the average amplitude of MEPs elicited with single-pulse TMS delivered at 120% of resting motor threshold. The iTBS protocol was delivered in bursts of trains of 3 pulses at 50 Hz and inter-burst intervals of 200 ms for a total of 2 seconds each train. Each train of pulses was delivered every 8 seconds for a total of 192 seconds, and a total of 600 pulses. The intensity of pulse was delivered at 80% of individuals AMT. TMS-iTBS data were acquired from three sets of 30 pulses before iTBS (Baseline) and at 5, 10, 20 and 30 minutes post-iTBS (Post5, Post10, Post20, Post30). To reduce the influence of extreme values, individual MEPs were log10-transformed, averaged across each timepoint (Baseline, Post5, Post10, Post20, Post30), and back-transformed into geometric means. All subsequent analyses were performed using these values.

2.3. Timed Up and Go (TUG) Assessment

The TUG performance was assessed in all participants to (1) assess functional mobility during walking (TUG single task, Figure 1B) (Hafsteinsdóttir et al., 2014) and (2) during walking while performing a cognitive task (TUG dual-task, Figure 1C) (Ohzuno & Usuda, 2019). For this assessment, participants were instructed to rise from chair on command, walk 3 meters at a self-selected pace, walk back to the chair and sit down. In the dual-task condition, participants were given a 3-digit number at the beginning of the trial and were instructed to perform serial 7 subtractions during the test. For the TUG, the time taken to complete the task was computed as a measure of functional mobility. For the TUG dual-task, a dual-task effect (DTE) was computed as the percent change of the TUG dual-task from the TUG single task (Kelly et al., 2010). “Dual-task” refers to a behavioral paradigm where a participant has to complete two tasks simultaneously—in this example, ambulating and serial subtraction—that compete for cognitive resources such as attention and executive functions. The “dual-task cost” refers to the decrement in one ability from adding the second competing one reflecting cognitive-motor interference. Typically, this cost is measured from the standpoint of walking (or TUG) speed as the dependent variable and the cognitive load (task vs. no task) as the independent variable. The TUG-DTE values were inverted so that higher scores represent better performance (less cost).

2.4. Clinical and performance measures for post-stroke participants

We obtained the following information from the AHA-Bugher study: time since stroke onset, stroke type, location and severity, physical function, and cognitive status. Global cognitive status was measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Smith et al., 2007). Physical function status was measured with the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS-16) (Duncan et al., 2003). The SIS-16 consists of 16 items assessing 4 physical domains (strength, hand function, mobility, and daily and instrumental activities), wherein higher scores indicate better performance.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro (v.15.0, SAS Institute Inc, USA) using a two-tailed 95% confidence interval (ɑ=.05) and assuming data normality and homoscedasticity. Within-group differences were assessed by entering average MEP amplitudes (mV) for each time point into separate random-effects linear models with the within-subject factor Time (Baseline, Post5, Post10, Post20, Post30). Pairwise comparisons of post-iTBS time point to baseline were performed using Student’s t-tests. Between-group differences were assessed using post-iTBS timepoints expressed as the percent change (%∆) from baseline and entered into mixed-effects linear models between-subjects factor Group (stroke, control), the within-subject factor Time (Post5, Post10, Post20, Post30), and the interaction of Group*Time. Following this procedure, we split out stroke patients in two sub-groups: early stroke (≤ 150 days), and late stroke (>150 days). Then, we performed an additional exploratory sub-cohort mixed-effects analysis to assess if post-iTBS timepoints differed between either subgroup compared to the controls.

To test the behavioral correlates and mechanisms of neuroplasticity, and aimed to reduce the risk of Type-I error inflation, we defined a priori a specific time window within the post-iTBS time period, specifically measuring the 10–20 minutes post-iTBS as our neuroplasticity measure (%∆ MEPs at Post10–20), which corresponds to the peak effect of iTBS in healthy adults (Wischnewski & Schutter, 2015). This post-iTBS time window also demonstrates the highest test-retest reliability in older clinical populations (Fried et al., 2017). We calculated the Spearman-rank correlation coefficient (rs) between Post10–20%∆ and: time since stroke (days), SIS-16 (#/80), TUG (seconds) and TUG-DTE (%∆). In order to compare correlations between-groups, we transformed r to z scores to keep in a normal distribution using the Fisher z-transformation test. Given the exploratory nature of these analyses, individual p-values were not corrected for multiple comparisons and should be interpreted accordingly.

Our sample of 16 participants per group provided 80% power to detect Cohen’s d≥ 1.02 between-group effect. Within each group, this sample provided 80% power to detect a correlation of |r|≥ .60.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristic and outcome measures

Table 2 displays demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcome measures. All subjects tolerated TMS-iTBS and no adverse events were reported.

Table 2.

Demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcome measures.

| Mean ± SD | Stroke Group (n= 16) | Control Group (n= 16) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 57 ± 13.7 | 55 ± 10.9 |

| Gender, n(%) | ||

| female | 7 (43.7) | 8( 50) |

| Physical activity | ||

| IPAQ METs per/week | 454 ± 573.3 | 473 ± 394.9 |

|

| ||

| Global cognition | ||

| MoCA | 22.1 ± 4.5 | 25.8 ± 1.7 |

|

| ||

| Stroke characteristics | ||

| Stroke Disability (mRS), n (%) | - | |

| Not significant | 6 (37.5) | |

| Slight | 4 (25.0) | |

| Moderate | 6 (37.5) | |

| Time since stroke onset, days | 167 ± 140 | |

| Location, n (%) | ||

| Cortical | 5 (31.3) | |

| Subcortical | 11 (68.7) | |

| Type, n(%) | ||

| Ischemic | 14 (87.5) | |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 2 (12.5) | |

| Severity | ||

| NIHSS | 2.2 ± 1.9 | |

| minor (0–4), n (%) | 12 (80) | |

| moderate (≥5), n (%) | 3 (20) | |

|

| ||

| Functional performance | ||

| SIS-16 | 63.6 ± 13.0 | - |

| TUG, seconds | ||

| Single-Task | 16.7 ± 10.2 | 9.7 ± 1.9 |

| Dual-Task | 21.7 ± 12.8 | 10.9 ± 2.0 |

| TUG-DTE, % | −24.5 ± 14.5 | −14.6 ± 21.7 |

Abbreviations: IPAQ = International Physical Activity Questionnaire; METs=Metabolic Equivalents; MoCA=Montreal Cognitive Assessment; mRS= modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS= National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SIS-16-Stroke Impact Scale 16; TUG=Timed up and Go; DTE = Dual-task Effect.

3.2. TMS outcomes

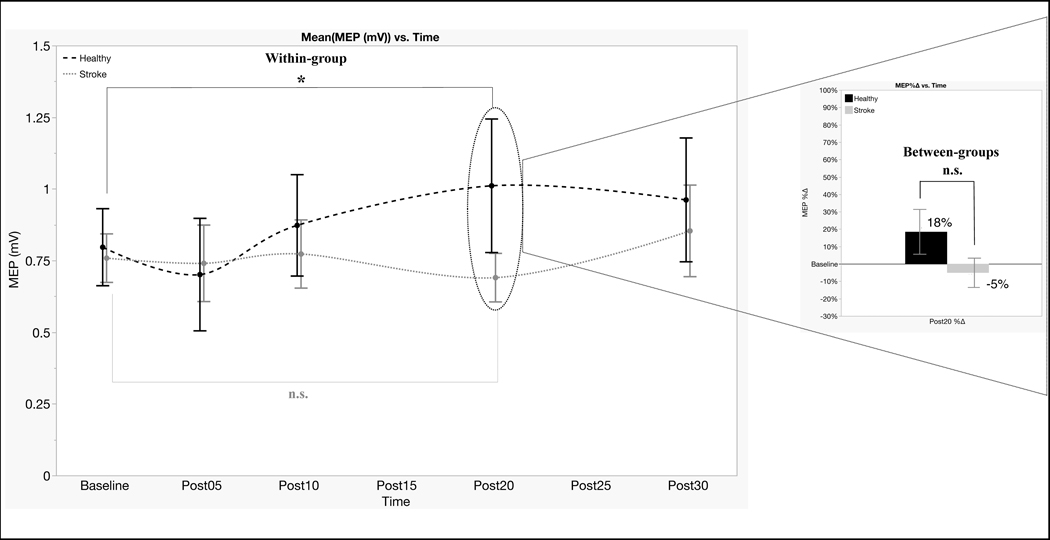

T-tests yielded no group difference for RMT, AMT and baseline MEPs (all t-values ≤ 0.54 and p-values ≥ 0.59). These results indicate that post-stroke and control groups did not differ in corticomotor reactivity or the corticospinal response to TMS. Concerning the effects of TMS-iTBS within-group, the random-effects models indicated MEPs varied significantly by Time in the control group (F4,59= 3.33, p= .016, η2= .18), but not in the stroke group (F4,60= .70, p= .60, η2= .04). This indicated that MEPs amplitudes were significantly potentiated by TMS-iTBS in the healthy group, but not in the stroke group. Planned pairwise comparisons showed that the effect in the control group was driven by significant changes at Post20 (t= 2.54, p= .014, Figure 2).

Figure 2. TMS-iTBS induced modulation of MEPs.

Notes. MEPs varied significantly by Time in the healthy control group (black large dotted line) driven by significant changes at Post20, but not in the stroke group (gray short dotted line). Statistical difference was not found between stroke and control groups (bar chart).

* = significant difference between baseline and Post20 in the control group

n.s. = non-significant changes

Concerning the between-group comparison of TMS-iTBS responses, the mixed-effect linear model showed no effect of Group (F1,30=.26, p= 0.61, η2= .01) and no Group*Time interaction (F3,89= 1.25, p= 0.30, η2= .04), but there was an overall effect of Time (F3,89= 2.74, p= 0.04, η2= .08). This indicated that mechanisms of neuroplasticity after stroke were not different from healthy individuals (no main effect of group), and there were no differences between the groups at any of the time points (no Group*Time interaction effect). However, TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity was significantly different between time-points across the groups (main effect of time), indicating that TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity was significantly different between time points. See Table 3 for detailed information on TMS baseline and post TMS-iTBS data.

Table 3.

TMS baseline and post TMS-iTBS data.

| TMS | Stroke patients (n=16) | Control participants (n=16) | Statistical Analysis | df | F/t | p-value | |η2| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Motor threshold (%) | |||||||

| RMT | 55.1±8.3 | 54.4±12.2 | T-test | 30 | −.17 | .87 | .03 |

| AMT | 42.1±8.2 | 43.8±9.9 | 30 | .54 | .59 | .02 | |

|

| |||||||

| Baseline MEPs (mV) | |||||||

| Post0 | 0.76±0.34 | 0.79±0.54 | T-test | 30 | .24 | .81 | .03 |

|

| |||||||

| Post-iTBS MEPs (mV) | Stroke Random-effects model | 4,60 | .70 | .60 | .04 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Control Random-effects model | 4,59 | 3.33 | .016 | .18 | |||

| Post5 | 0.74±0.54 | 0.70±0.76 | Control Planned t-test | 15 | −.59 | .55 | .02 |

| Post10 | 0.77±0.48 | 0.87±0.71 | 15 | .90 | .37 | .05 | |

| Post20 | 0.69±0.34 | 1.01±0.93 | 15 | 2.54 | .014 | .30 | |

| Post30 | 0.85±0.64 | 0.96±0.86 | 15 | 1.95 | .055 | .20 | |

|

| |||||||

| Post-iTBS MEPs (%Δ) | Mixed-effect linear model | ||||||

| Post5 | −1.4±45.0 | −15.0±37.0 | |||||

| Post10 | 4.5±49.0 | 10.0±41.0 | Group | 1,30 | .26 | .61 | .01 |

| Post20 | −5.0±34.0 | 18.0±52.0 | Time | 3,89 | 2.74 | .04 | .08 |

| Post30 | 14.0±61.0 | 25.0±73.0 | Group*Time | 3,89 | 1.25 | .30 | .04 |

Abbreviations: TMS = Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation; RMT = Resting Motor Threshold; AMT = Active Motor Thresholds; MEPs = Motor Evoked Potentials; iTBS = Intermittent Theta-Burst Stimulation; mV = millivolts; %Δ = percent change

3.3. TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity and functional capacity associations

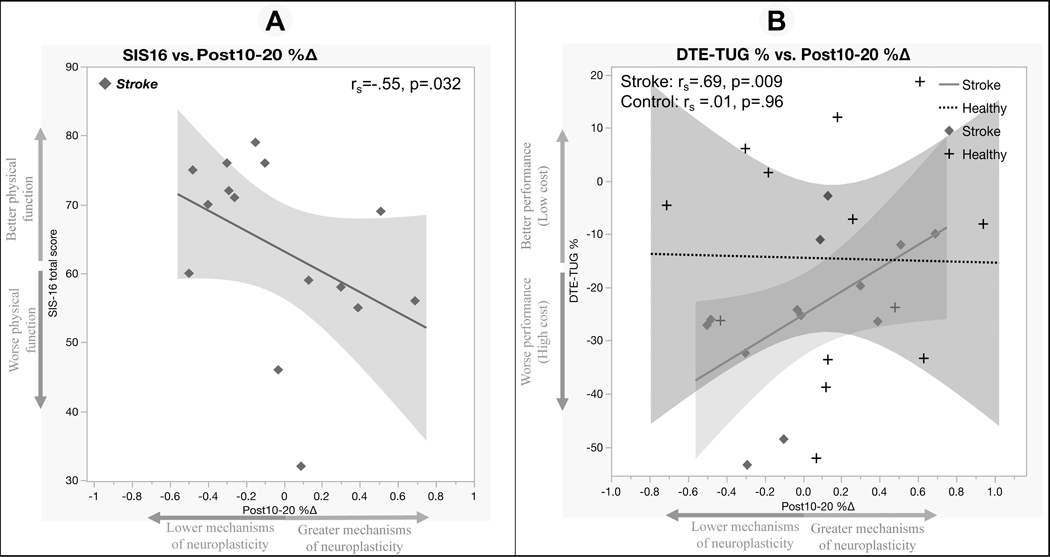

Within the stroke group, Spearman correlations showed that greater Post10–20%∆ was significantly associated with lower SIS-16 scores (rs= −.55, p= .032, Figure 3A) By contrast, there was a significant positive relationship between TUG-DTE and Post10–20%∆ (rs= .69, p= .009, Figure 3B) in the stroke group, but not in the control (rs= .01, p= .96). The Fisher r-to-z transformation test showed that the correlation of TUG-DTE and Post10–20%∆ was significantly different between groups (z = 2.14, p = .03). Together, these results indicated that cortical motor neuroplasticity is relevant for both physical function and dual-task abilities in individuals post-stroke. Those with greater efficacy of mechanisms of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity demonstrated worse physical function and better cognitive-motor interference.

Figure 3. Relationships between TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity and functional/clinical post-stroke outcomes.

Notes. A. Greater mechanisms of neuroplasticity was significantly associated with lower (SIS-16) physical function.

B. Better (TUG-DTE) functional performance was positively associated with mechanisms of neuroplasticity.

3.4. TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity and time since stroke association

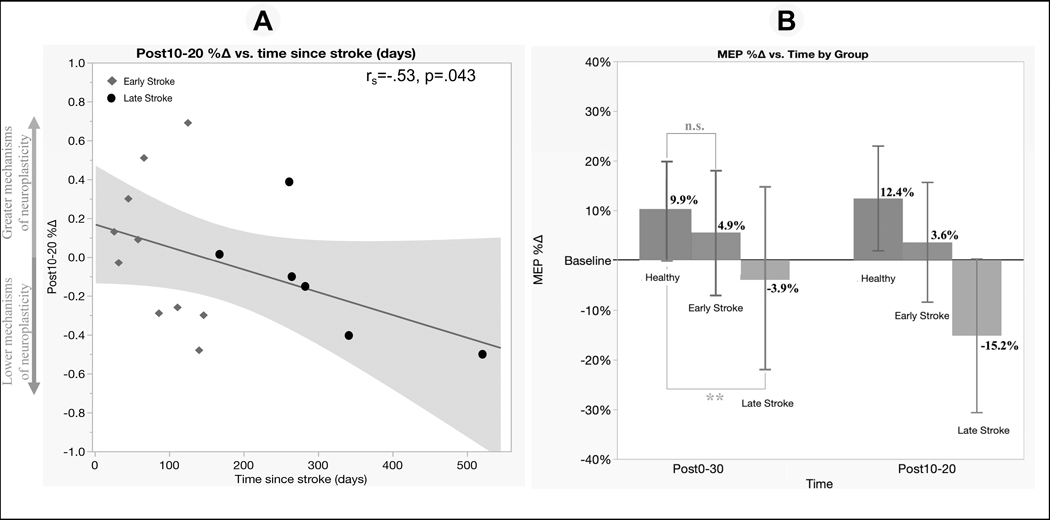

Within the stroke group, Spearman correlation revealed an association between longer time since stroke onset and lower Post10–20%∆ (rs= −.53, p= .043, Figure 4A). This result indicated that those in the earlier stages post-stroke demonstrated greater efficacy of mechanisms of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity.

Figure 4. Correlation and sub-cohort mixed-effect analysis of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity and time since stroke onset.

Notes. A. Within the stroke group, a longer time since stroke was negatively associated with the efficacy of mechanisms of neuroplasticity.

B. ** = significant trend Group*Time interaction effect between the late stroke group and healthy controls; n.s. = non-significant effect between the early stroke group and healthy controls

3.5. Sub-cohort analysis of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity and time since stroke onset

Sub-cohort mixed-effect analysis of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity did not show a significant Group*Time interaction effect between the early stroke group and controls (F3,71= .68, p= 0.57, η2= .03), but there was a trend toward a difference in the mechanism of neuroplasticity between those in the late-stage post-stroke and control groups (F3,56= 2.45, p= 0.07, η2= .12, Figure 4B). This analysis suggests that mechanisms of neuroplasticity were not different between those in the early stage post-stroke and controls, but there appeared to be a trend toward a “diminished” or “hypoactive” state of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity in individuals in the late stage after stroke onset, when compared to controls individuals at different time-points. The largest differences occurred at Post10–20%∆, where the control group increased 12.4% and the late-stage stroke group decreased by 15.2% (Figure 4B). Alternatively, this exploratory analysis with only 16 individuals should be interpreted with caution as it can be affected by lack of statistical power and TMS artifacts in this population.

4. Discussion

In this study, we assessed TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity mechanisms within and between 32 post-stroke patients and a control group matched by age, gender and physical activity level. The present findings partially supported our hypothesis that the efficacy of the mechanisms of neuroplasticity may vary in the course of post-stroke recovery. We demonstrated that the stroke group did not show the expected facilitatory response to TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity as did the control group. Interestingly, however, we found no group-level differences in TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity. This may have been due to the masking of subtle differences by high inter-individual variability and insufficient statistical power to detect smaller group differences in this proof-of-principle study. Sub-cohort analysis revealed insights into the variability of neuroplasticity mechanisms by demonstrating that in the early post-stroke period, the TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity response was not different from healthy controls, but appeared to be hypoactive in those in the late post-stroke period.

Further, our results showed that TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity was correlated with behavioral functional and clinical post-stroke outcomes. Specifically, patients with earlier time from stroke onset, and those with worse physical function, had greater efficacy of mechanisms of TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity. These preliminary findings of “diminished” or “hypoactive” mechanisms of neuroplasticity between early and late-stage stroke are not being interpreted as a negative clinical outcome. Evidence demonstrates that mechanisms of neuroplasticity are central to motor functional recovery post-stroke and have been demonstrated to be spontaneously dynamic (Pellicciari et al., 2018). For example, studies highlight a period of robust efficacy of mechanisms of neuroplasticity in a time-limited window shortly after stroke, when greatest functional gains occur (known as the “critical-period”) (Murphy & Corbett, 2009). This process is believed to be driven by an intrinsic need to reorganize cortical circuits post-injury, which would eventually ‘down regulate’ and ‘stabilize’ throughout the functional recovery period. Alterations in neuroplasticity mechanisms in the course of post-stroke recovery has also been reported in humans (Pellicciari et al., 2018). Against the backdrop of such existing evidence, a future hypothesis that can be generated from the interpretation of our findings could capture such changes in underlying neuroplasticity mechanisms by utilizing non-invasive brain stimulation as we have used in this study.

Furthermore, we found that mechanisms of neuroplasticity, as assessed by TMS-iTBS had a seemingly differential relationship with dual-task abilities, wherein greater neuroplasticity was associated with better dual-task performance. This positive relationship between plasticity and TUG-DTE might seem an expected response. However, one explanation can be the dynamic course of neuroplasticity in the period of recovery in stroke, as well as the specific requirements of the dual-task assessment. Our results demonstrate that the period of greatest mechanisms of neuroplasticity is the early period post-stroke, when functional ability is at its lowest. The dual-task assessment requires the individual to perform two discrete tasks simultaneously. Goal one is to walk as fast as you can (TUG-single-task) and goal two is to walk while performing a serial 7 subtractions cognitive task (TUG-dual-task). If an individual has limited attentional resources, meaning less cognitive and or physical capacity, there is going to be a tradeoff cost (Ohzuno & Usuda, 2019). The addition of the secondary task may result in cognitive-motor interference, leading to a degradation in performance of each individual task (Woollacott & Shumway-Cook, 2002). In this assessment, the ‘score’ measures how much the addition of a cognitive task impairs one’s walking speed, rather than how accurately a cognitive task is performed while one is walking. As a result, there can be the appearance of little or no ‘cost’ early after stroke, only because the individual is, more often than not, relearning how to walk, and thus, needing to shift in attentional resources and timing of response to prioritize walking (for safety) (Klapp et al., 2019; Sigman & Dehaene, 2006). In this case, if the mental task does not increase the walking time (regardless of the actual performance on the mental task), this is interpreted as little or no ‘cost’. Later in the stage of recovery post-stroke, increased functional ability may enable one to achieve greater walking distances, but also to be more engaged in the dual-task performance (with many more responses), but any ‘slowing down’ in walking is interpreted as ‘higher cost’. Future studies addressing these specific nuances of postural control and dual-task behavior post-stroke are warranted.

4.1. Clinical implications and limitations

The current study demonstrated that TMS-iTBS assessment is a safe procedure to evaluate corticomotor reactivity and efficacy of mechanisms of neuroplasticity in individuals post-stroke. We further show that these assessments may help inform on functionally relevant changes in the brains over to course of the sequelae of stroke. However, in light of the following limitations, our conclusions should be treated as speculative and not generalizable. TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity induced measures of corticospinal excitability should be interpreted with caution given the high variability of the data and the generally modest statistical power achieved. It is also important to interpret these results in the context of “mechanism of neuroplasticity” and not “neuroplasticity” by itself. The term “neuroplasticity” as it is used in the context of rehabilitation usually refers to induced plasticity changes in neural structure and/or function in response to adaptative response of the nervous system recovery and rehabilitation, and in counterpart, the TMS-iTBS paradigm was designed and applied to represents activity-dependent changes in neural functions that modulate subsequent synaptic plasticity such as long-term potentiation (LTP).

We acknowledge that evaluating the mechanisms of LTP-like plasticity in the motor cortex is limited in scope and that our results may not extend to non-motor regions. We chose the motor cortex for three important and inter-related reasons: First, motor deficits are the most common lasting impact of stroke and the single largest cause of stroke-related costs to individual and societies. Second, while there is no doubt that other domains can be impacted, such as language and visuospatial attention (Fried et al., 2016), the motor cortex is relatively simpler and more stereotyped in its organization, providing an optimal testing bench to investigate the impact of stroke on the mechanisms of plasticity. Third, with the corticospinal output giving a ready and reliable response to a single TMS pulse, both the mechanisms of cortical excitability and their noninvasive neuromodulation with repetitive TMS have been more extensively studied and thus the mechanisms are better understood. Futures studies combining TMS with concurrent EEG may be able to extend these findings to non-motor brain networks more closely linked to specific cognitive functions and pathologies.

In the early stage after stroke, several pathophysiological factors (e.g., loss of cortical-motoneurons and altered membrane excitability) can lead to difficulty in reliably eliciting MEPs from the affected hemisphere (Byblow et al., 2015; Stinear et al., 2012). Consequently, we chose to target the stimulation to the contralesional hemisphere out of a combination of cautionary (minimizing risks inherent of TMS) and practical concerns. Moreover, the results should be interpreted in the context of the bilateral motor network that may vary in the course of post-stroke recovery. We cannot rule out the possible differences in the hemispheres and cannot compare our results to sham TMS stimulation. These areas should be addressed in future studies.

4.2. Conclusion

TMS-iTBS may be a useful approach to investigate mechanisms of neuroplasticity that are relevant for functional recovery after stroke. Our findings suggest that mechanisms of neuroplasticity, as assessed by TMS-iTBS varied in the time course of stroke recovery. We found that post-stroke patients did not show the same pattern of facilitation following TMS-iTBS as compared with healthy controls, which was dependent on two main outcomes: time since stroke and functional status. In the early stroke stage, the efficacy of mechanisms of neuroplasticity was no different than healthy controls, but in the late stage, they appeared to be diminished or hypoactive. Within the stroke group, stroke patients with better dual-task performance, and those with worse physical function (strength, hand function, mobility, and daily/instrumental activities), had greater responses on the TMS-iTBS neuroplasticity assessment. Due to study limitations, generalization of the findings will require replication of the results in a larger, better-characterized cohort. Group differences were masked by high inter-individual variability and future longitudinal studies in larger samples are needed.

Sources of funding

JGO was supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number KL2TR002737.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

Dr. A. Pascual-Leone is a co-founder of Linus Health and TI Solutions AG; serves on the scientific advisory boards for Starlab Neuroscience, Magstim Inc., and MedRhythms; and is listed as an inventor on several issued and pending patents on the real-time integration of noninvasive brain stimulation with electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging. Dr. J. Gomes-Osman works as Director of Interventional Therapy at Linus Health.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

References

- Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, … Muntner P. (2017). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 135(10), e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byblow WD, Stinear CM, Barber PA, Petoe MA, & Ackerley SJ. (2015). Proportional recovery after stroke depends on corticomotor integrity. Annals of Neurology, 78(6), 848–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WH, Fried PJ, Saxena S, Jannati A, Gomes-Osman J, Kim YH, & Pascual-Leone A. (2016). Optimal number of pulses as outcome measures of neuronavigated transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clinical Neurophysiology, 127(8), 2892–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC. (2008). Repairing the human brain after stroke: I. Mechanisms of spontaneous recovery. Annals of Neurology, 63(3), 272–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Nelles G, Benson RR, Kaplan JD, Parker RA, Kwong KK, Kennedy DN, Finklestein SP, & Rosen BR. (1997). A functional MRI study of subjects recovered from hemiparetic stroke. Stroke, 28(12), 2518–2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PW, Lai SM, Bode RK, Perera S, & DeRosa J. (2003). Stroke impact scale-16: A brief assessment of physical function. Neurology, 60(2), 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas C, Perez J, Knobel M, Tormos JM, Oberman L, Eldaief M, Bashir S, Vernet M, Peña-Gómez C, & Pascual-Leone A. (2011). Changes in Cortical Plasticity Across the Lifespan. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 3(APR), 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French B, Thomas LH, Leathley MJ, Sutton CJ, McAdam J, Forster A, Langhorne P, Price CIM, Walker A, & Watkins CL, Connell L, Coupe J, & McMahon N. (2007). Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 4, p. CD006073). John Wiley and Sons Ltd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PJ, Jannati A, Davila-Pérez P, & Pascual-Leone A. (2017). Reproducibility of Single-Pulse, Paired-Pulse, and Intermittent Theta-Burst TMS Measures in Healthy Aging, Type-2 Diabetes, and Alzheimer’s Disease. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9(August), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PJ, Schilberg L, Brem A-K, Saxena S, Wong B, Cypess AM, Horton ES, & Pascual-Leone A. (2016). Humans with Type-2 Diabetes Show Abnormal Long-Term Potentiation-Like Cortical Plasticity Associated with Verbal Learning Deficits. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 55(1), 89–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Osman J, Cabral DF, Hinchman C, Jannati A, Morris TP, & Pascual-Leone A. (2017). The effects of exercise on cognitive function and brain plasticity - a feasibility trial. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 35(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafsteinsdóttir TB, Rensink M, & Schuurmans M. (2014). Clinimetric Properties of the Timed Up and Go Test for Patients With Stroke: A Systematic Review. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 21(3), 197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Z, Wang D, Zeng Y, & Liu M. (2013). Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for improving function after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y. (2015). Brain plasticity and rehabilitation in stroke patients. Journal of Nippon Medical School, 82(1), 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-Z, Chen R-S, Rothwell JC, & Wen H-Y. (2007). The after-effect of human theta burst stimulation is NMDA receptor dependent. Clinical Neurophysiology, 118(5), 1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-Z, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, & Rothwell JC. (2005). Theta Burst Stimulation of the Human Motor Cortex. Neuron, 45(2), 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CO, Nguyen M, Roth GA, Nichols E, Alam T, Abate D, Abd-Allah F, Abdelalim A, Abraha HN, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Adebayo OM, Adeoye AM, Agarwal G, Agrawal S, Aichour AN, Aichour I, Aichour MTE, Alahdab F, Ali R, … Murray CJL. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology, 18(5), 439–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly VE, Janke AA, & Shumway-Cook A. (2010). Effects of instructed focus and task difficulty on concurrent walking and cognitive task performance in healthy young adults. Experimental Brain Research, 207(1–2), 65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klapp ST, Maslovat D, & Jagacinski RJ. (2019). The bottleneck of the psychological refractory period effect involves timing of response initiation rather than response selection. In Psychonomic Bulletin and Review (Vol. 26, Issue 1, pp. 29–47). Springer New York LLC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S, Tiozzo E, Simonetto M, Loewenstein D, Wright CB, Dong C, Bustillo A, Perez-Pinzon M, Dave KR, Gutierrez CM, Lewis JE, Flothmann M, Mendoza-Puccini MC, Junco B, Rodriguez Z, Gomes-Osman J, Rundek T, & Sacco RL. (2020). Randomized Trial of Combined Aerobic, Resistance, and Cognitive Training to Improve Recovery From Stroke: Feasibility and Safety. Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TH, & Corbett D. (2009). Plasticity during stroke recovery: from synapse to behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(12), 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberman L. (2010). Transcranial magnetic stimulation provides means to assess cortical plasticity and excitability in humans with fragile X syndrome and autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 2(JUN). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohzuno T, & Usuda S. (2019). Cognitive-motor interference in post-stroke individuals and healthy adults under different cognitive load and task prioritization conditions. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 31(3), 255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A, Freitas C, Oberman L, Horvath JC, Halko M, Eldaief M, Bashir S, Vernet M, Shafi M, Westover B, Vahabzadeh-Hagh AM, & Rotenberg A. (2011). Characterizing Brain Cortical Plasticity and Network Dynamics Across the Age-Span in Health and Disease with TMS-EEG and TMS-fMRI. Brain Topography, 24(3–4), 302–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicciari MC, Bonnì S, Ponzo V, Cinnera AM, Mancini M, Casula EP, Sallustio F, Paolucci S, Caltagirone C, & Koch G. (2018). Dynamic reorganization of TMS-evoked activity in subcortical stroke patients. NeuroImage, 175(September 2017), 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plow EB, Sankarasubramanian V, Cunningham DA, Potter-Baker K, Varnerin N, Cohen LG, Sterr A, Conforto AB, & Machado AG. (2016). Models to Tailor Brain Stimulation Therapies in Stroke. Neural Plasticity, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock A, Farmer SE, Brady MC, Langhorne P, Mead GE, Mehrholz J, & van Wijck F. (2014). Interventions for improving upper limb function after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Antal A, Bestmann S, Bikson M, Brewer C, Brockmöller J, Carpenter LL, Cincotta M, Chen R, Daskalakis JD, Di Lazzaro V, Fox MD, George MS, Gilbert D, Kimiskidis VK, Koch G, Ilmoniemi RJ, Lefaucheur JP, Leocani L, … Hallett M. (2021a). Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clinical Neurophysiology, 132(1), 269–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Antal A, Bestmann S, Bikson M, Brewer C, Brockmöller J, Carpenter LL, Cincotta M, Chen R, Daskalakis JD, Di Lazzaro V, Fox MD, George MS, Gilbert D, Kimiskidis VK, Koch G, Ilmoniemi RJ, Lefaucheur JP, Leocani L, … Hallett M. (2021b). Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clinical Neurophysiology, 132(1), 269–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman M, & Dehaene S. (2006). Dynamics of the central bottleneck: Dual-task and task uncertainty. PLoS Biology, 4(7), 1227–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Gildeh N, & Holmes C. (2007). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment: Validity and Utility in a Memory Clinic Setting. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 52(5), 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinear CM, Barber PA, Petoe M, Anwar S, & Byblow WD. (2012). The PREP algorithm predicts potential for upper limb recovery after stroke. Brain, 135(8), 2527–2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppa A, Huang Y-Z, Funke K, Ridding MC, Cheeran B, Di Lazzaro V, Ziemann U, & Rothwell JC. (2016). Ten Years of Theta Burst Stimulation in Humans: Established Knowledge, Unknowns and Prospects. Brain Stimulation, 9(3), 323–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi N, & Izumi SI. (2012). Maladaptive plasticity for motor recovery after stroke: Mechanisms and approaches. In Neural Plasticity (Vol. 2012). Hindawi Publishing Corporation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay S, Vernet M, Bashir S, Pascual-Leone A, & Théoret H. (2015). Theta burst stimulation to characterize changes in brain plasticity following mild traumatic brain injury: A proof-of-principle study. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, 33(5), 611–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischnewski M, & Schutter DJLG. (2015). Efficacy and Time Course of Theta Burst Stimulation in Healthy Humans. Brain Stimulation, 8(4), 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woollacott M, & Shumway-Cook A. (2002). Attention and the control of posture and gait: a review of an emerging area of research. Gait & Posture, 16(1), 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.