Significance

Several studies highlight the role of morphogens during craniofacial development. We identified a conserved role for Defective proventriculus, Dve, the Drosophila ortholog of human SATB1, in the positioning of eyes on the head and the interocular distance by regulating Wg (Wingless) transcription and its gradient. Deregulation of the Wg morphogen gradient results in developmental defects like craniofacial abnormalities including hypertelorism in humans. However, the genetic basis of how it is caused is not clear. This study shows that a transcription factor, Dve, has a conserved function in regulating the transcription of Wg and its gradient from a subset of cells in the developing eye–antennal imaginal disc to determine the placement of eyes on the head.

Keywords: Drosophila eye, retinal determination, defective proventriculus, SATB1, Wingless

Abstract

Despite the conservation of genetic machinery involved in eye development, there is a strong diversity in the placement of eyes on the head of animals. Morphogen gradients of signaling molecules are vital to patterning cues. During Drosophila eye development, Wingless (Wg), a ligand of Wnt/Wg signaling, is expressed anterolaterally to form a morphogen gradient to determine the eye- versus head-specific cell fate. The underlying mechanisms that regulate this process are yet to be fully understood. We characterized defective proventriculus (dve) (Drosophila ortholog of human SATB1), a K50 homeodomain transcription factor, as a dorsal eye gene, which regulates Wg signaling to determine eye versus head fate. Across Drosophila species, Dve is expressed in the dorsal head vertex region where it regulates wg transcription. Second, Dve suppresses eye fate by down-regulating retinal determination genes. Third, the dve-expressing dorsal head vertex region is important for Wg-mediated inhibition of retinal cell fate, as eliminating the Dve-expressing cells or preventing Wg transport from these dve-expressing cells leads to a dramatic expansion of the eye field. Together, these findings suggest that Dve regulates Wg expression in the dorsal head vertex, which is critical for determining eye versus head fate. Gain-of-function of SATB1 exhibits an eye fate suppression phenotype similar to Dve. Our data demonstrate a conserved role for Dve/SATB1 in the positioning of eyes on the head and the interocular distance by regulating Wg. This study provides evidence that dysregulation of the Wg morphogen gradient results in developmental defects such as hypertelorism in humans where disproportionate interocular distance and facial anomalies are reported.

During organogenesis, events like cell fate specification and patterning decisions are dependent on an optimal balance of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways. Signaling molecules and their long/short-range distribution affect the cell fate decisions in developing fields. In all multicellular organisms, the cells within the field interpret their position and function with respect to a concentration or gradient of signaling molecules (like morphogens) to determine their developmental fate(s).

Wingless (Wg), a long-range secretory molecule of the Wnt family, generates a morphogen gradient to regulate developmental processes (1). This occurs as 1) “Wnt- or Wg-producing cells” produce and secrete the protein for paracrine signaling, 2) the Wg morphogen is transported to receiving cells and spreads over several cells through the tissue to form a gradient, and 3) these cells respond to Wg in a concentration-dependent manner to activate target genes that regulate pattern formation and determine cell identities (2). The Wg ligand can act as both a short- and long-range signaling molecule to organize or orchestrate the expression of other genes crucial for development. Restricting autonomous, short-, or long-range Wg signaling impacts the expression of its target gene bifid (bi) differently in the eye (3). In the Drosophila eye, the level and distribution of Wg are crucial for various functions such as growth, cell proliferation, patterning, cell death, and suppression of eye fate (4). In humans, dysregulation of morphogen levels affects growth and patterning and results in developmental birth defects (5, 6).

The Drosophila eye develops from larval eye imaginal discs. The early eye primordium undergoes transition from a monolayer epithelium to a three-dimensional organ by delineation of anterior–posterior (AP), dorsal–ventral (DV), and proximal–distal (PD) axes (7). In Drosophila, the eye fate is specified by the expression of eyeless (ey) in the entire eye primordium. The DV axis is the first lineage restriction event, which results in formation of an equator at the boundary of dorsal and ventral compartments. Dorsal eye fate is established by expression of the GATA-1 transcription factor pannier (pnr), which regulates wg and homeodomain genes of the Iroquois complex (7–10). In the Drosophila eye disc, Wg is expressed at the anterolateral margin.Wg negatively regulates photoreceptor differentiation and determines the eye versus head fate (11–14). Loss-of-function (LOF) of wg in the developing eye results in eye enlargements both on dorsal and ventral margins due to generation of ectopic morphogenetic furrows (MF) (13, 14). MF marks a synchronous wave of retinal differentiation in the developing eye (15). In the dorsal eye, spatiotemporal regulation of wg is complex. We have previously shown that Pnr also regulates Wg, although it may not be the direct and sole regulator of Wg in the developing eye (10).

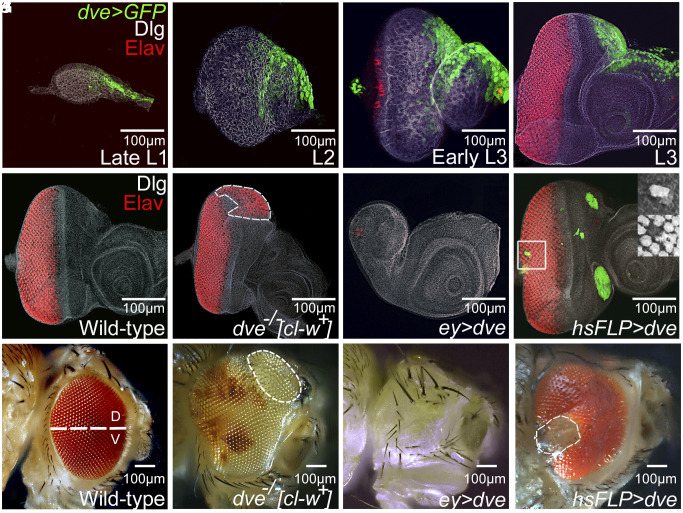

We have identified defective proventriculus (dve) as a DV patterning gene that regulates wg expression in the developing eye. Dve encodes a K50 homeodomain transcription factor, an ortholog of human SATB1 (16, 17), which is required for regulation of gene expression in retinal ganglion cells (18). In the late first-instar eye disc, dve expression begins in a small subgroup of cells (Fig. 1A). Expression of dve remains restricted to the anterodorsal eye disc near the head vertex region in the late second- and early third-instar stages (Fig. 1 B–D) and evolves to a small subset of ~150 to 200 dorsal cells in the third-instar eye imaginal disc as detected by the dve-reporter as well as Dve antibody (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). In the developing eye, LOF of dve results in dorsal eye enlargements along with the loss of ocelli (Fig. 1 G and H and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), whereas gain-of-function (GOF) of dve results in reduced eye size (Fig. 1 I and J). Random “flp-out” GOF (19) clones of dve also suppressed eye fate irrespective of the clone position in the dorsal or ventral domain of the developing eye (Fig. 1 K and L). This suggests that dve suppresses eye development. Therefore, we investigated the effect(s) of dve misexpression on retinal determination (RD) genes.

Fig. 1.

dve, a DV patterning gene is expressed in the dorsal head vertex region of the developing eye. (A–D) The spatiotemporal expression profile of dve was detected using dve Gal4 > UAS-GFP (green) in the developing (A) late L1, (B) L2, (C) early L3, and (D) L3 larval eye imaginal disc. dve expression (green) in the eye–antennal imaginal disc of the (A) late first-instar larva (L1) is initiated in 15 to 20 cells, close to the anterior margin. Note that discs are stained with Disc large (Dlg), a membrane-specific marker (white), and the panneural marker Elav (red) that marks the photoreceptor neurons. (B) In the early second-instar larva (L2), expression is restricted to a group of 30 to 40 cells on the dorsal eye margin, and in (C) early third-instar larva (early L3), expression is seen in the antenna and dorsal head vertex region. Note that the retinal differentiation has just initiated at this stage as seen by a single row of Elav-positive cells on the posterior margin. (D) In the late third-instar larva (late L3), expression is restricted to a group of cells on the dorsal eye margin and the antenna region. Note that dve expression is anterior to the furrow and does not overlap with the differentiated photoreceptor neurons on the dorsal margin. (E) Wild-type third-instar eye imaginal disc, which develops into a (F) compound adult eye. (G and H) LOF of dve, using a cell-lethal approach (20), results in dramatic dorsal eye enlargements as seen in the (G) eye imaginal disc and (H) adult eye. Note that loss of dve in the ventral eye has no effect. The white-dotted line marks the outline of enlargements in the eye imaginal disc and the adult eye. In the adult eye, LOF clones are marked by the absence of mini-white reporter. (I and J) Misexpression of dve (ey > dve) in the ey driver domain of the entire eye imaginal disc using ey-Gal4 driver results in suppression of the eye as evident from loss of Elav (red) expression in the (I) eye imaginal disc and the (J) adult eye. Adults of ey > dve showed no-eye. (K and L) Heat shock flippase–mediated generation of random GOF clones of dve marked by GFP reporter showed suppression of panneural marker Elav expression in the eye imaginal disc. All images/panels will have dorsal (D) up and ventral (V) down.

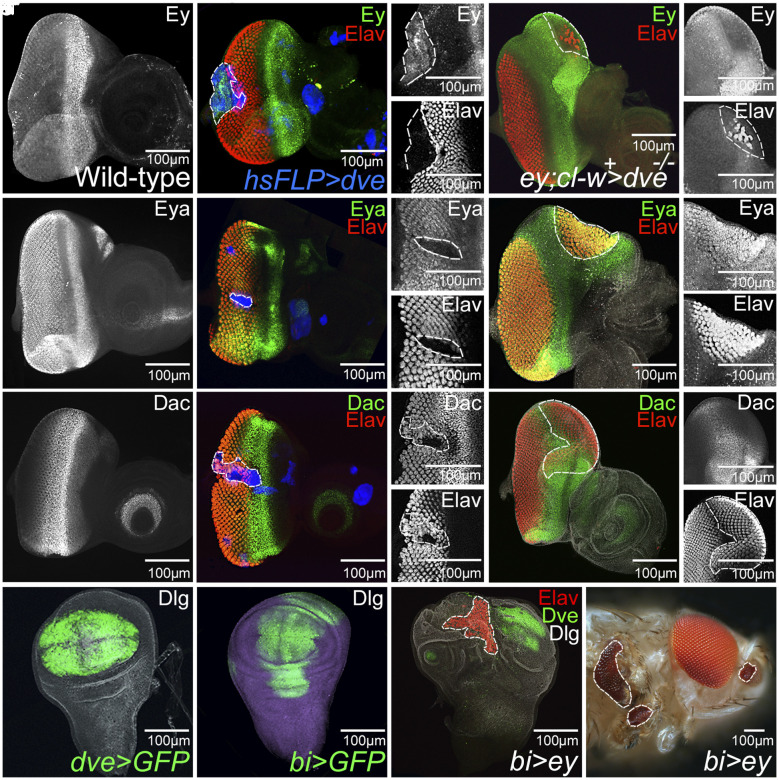

A cascade of highly conserved genes like ey, eyes absent (eya), sine oculis (so), and dachshund (dac) are required for eye field specification and differentiation (21). The eye suppression phenotype of dve GOF results in ectopic expression of the eye specification marker Ey (Fig. 2 B and B’) and suppression of retinal differentiation markers, Eya (Fig. 2 E and E’) and Dac (Fig. 2 H and H’). However, dorsal eye enlargement phenotypes of dve LOF clones showed no effect on Ey expression (Fig. 2 C and C’) but showed ectopic induction of downstream markers, Eya (Fig. 2 F and F’) and Dac (Fig. 2 I and I’). Our data suggest that dve may not affect eye specification but regulates retinal differentiation. We tested whether dve function is required to regulate differentiation by using an ectopic eye assay. Ectopic induction of ey in the wing pouch results in ectopic eyes in the wing disc (22) (Fig. 2 L and M). We used an optomotor blind (omb) or bi-Gal4 driver (12) to target expression of the ey transgene in the wing pouch (Fig. 2 K and L). Ectopic expression of master eye fate regulator, ey, induces retinal differentiation in the wing by repressing Dve expression in the wing pouch region (Fig. 2 J and L), suggesting that dve acts as an antagonist of RD gene function.

Fig. 2.

dve suppresses eye fate by down-regulating expression of the highly conserved RD gene network. (A) Wild-type expression of Ey in the anterior region of the third-instar eye disc. (B) Random GOF clones of dve marked by GFP (blue) exhibit induction of (B, and B’) Ey (green) whereas LOF clones of dve generated by the cell-lethal approach result in downregulation of (C, and C’) Ey. Note that Ey is an eye field specification marker which acts upstream of RD genes eya and dac, and differentiated photoreceptor neurons are marked by ELAV (red). (D) Wild-type expression of Eya, a RD gene, is seen both anterior and posterior to the MF and in the ocelli region of eye disc. (E–E”) GOF clones of dve marked by GFP (blue) exhibit suppression of (E, E’) Eya (green) and suppression of eye fate marked by (E, E”) ELAV (red). (F) LOF clones of dve result in ectopic eye formation along with induction of (F and F’) Eya (green) and Elav (red). (G) Dac expresses posterior to the MF in R1, R6, and R7 photoreceptor as well as anterior to the MF in a narrow band of cells of the wild-type eye imaginal disc. (H–H”) Random GOF clones of dve marked by GFP (blue) exhibit suppression of (H and H’) Dac (green) and ectopic induction of (H and H”) Elav (red) expression. (I–I”) LOF clones of dve results in downregulation of (I and I’) Dac along with dorsal eye enlargement as evident from (I”) ectopic Elav expression. (J and K) Expression domains of Gal4 drivers in the wing-imaginal discs. (J) dve-Gal4 (dve > GFP) and (K) bi-Gal4 (bi > GFP) drive GFP reporter expression (green) in the wing pouch. (L and M) Misexpression of ey in the bi-Gal4 domain induces an ectopic eye in the (L) larval wing-imaginal disc, based on ectopic Elav (red) expression, and (M) wing, leg, and antenna of the adult fly. (L) Note that Dve (green) expression is down-regulated in the wing pouch where ectopic ey induces an ectopic eye.

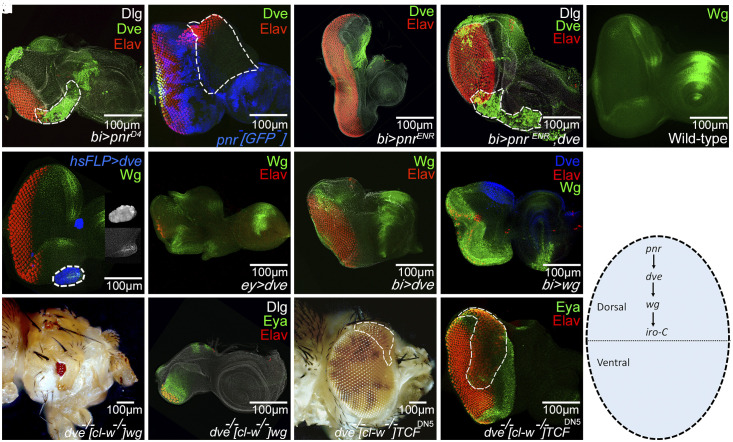

LOF and GOF phenotypes of dve in the eye are similar to another DV patterning gene, pnr (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (10). Even though their expression has partial overlap in the dorsal eye, dve has distinctively unique expression domain in the dorsal eye. The dorsal eye gene pnr is expressed in the dorsal eye margin as well as the peripodial membrane, whereas Dve is expressed in the disc proper in the dorsal head vertex region (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Our genetic epistasis analysis assigns dve, wg, and other dorsal genes to the dorsal gene hierarchy on the basis of expression and phenotypes (Fig. 1). We used bi-Gal4 to drive expression of transgenes on DV margins of the developing eye (12) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). bi-Gal4 can serve as an excellent tool for genetic epistasis experiments for dorsal eye genes as it drives expression both on the dorsal as well as ventral margins of the developing eye. Misexpression of pnr on the DV margin (bi > pnr) of the eye ectopically induces Dve on the ventral margin (Fig. 3A). LOF clones of pnr in the dorsal eye exhibit complete loss of dve expression (Fig. 3B). Additionally, the dorsal eye enlargement phenotype of dominant-negative pnr (pnrENR) misexpression (bi > pnrENR, Fig. 3C) is rescued when dve is coexpressed with pnrENR (bi > dve +pnrENR, Fig. 3D). Thus, GOF of dve masks the phenotype of LOF of upstream pnr, thereby suggesting that dve acts downstream of pnr. Ectopic flp-out clones of dve induce Wg in the eye disc (hsFLP > dve, Fig. 3F), and misexpression of dve in the posterior eye (ey > dve, Fig. 3G) or on the DV boundary (bi > dve, Fig. 3H) can induce ectopic Wg expression and thereby restrict retinal differentiation. Modulation of Wg levels in a dve mutant background can suppress (Fig. 3 J and K) or enhance (Fig. 3 L and M) the dve mutant phenotype of dorsal eye enlargement. The reduced eye phenotype of GOF of wg can mask the dorsal eye enlargement phenotype of dve LOF suggests that dve acts upstream of wg in the dorsal eye (Fig. 3N).

Fig. 3.

In dorsal eye gene hierarchy, dve acts downstream of pnr and upstream of wg. (A) Misexpression of pnr using the bi-Gal4 driver (bi > pnrD4) causes ectopic induction of Dve (green) in the ventral eye (marked by the white-dotted line). The endogenous expression of Dve in the dorsal eye can be seen along with pnr-mediated ectopic Dve expression on the ventral margin. (B) Loss of function of pnr marked by the absence of GFP (blue; white-dotted line marks the boundary of the clone) shows ectopic eye formation as seen by ectopic Elav (red) and loss of endogenous Dve (green) expression. (C) Loss of pnr on DV eye imaginal disc margin by using dominant negative pnr (bi > pnrENR) causes dorsal eye enlargements, which can be suppressed by (D) coexpressing dve (bi > pnrENR+dve) on the DV margins suggesting that dve GOF rescues the pnr LOF phenotype. Therefore, dve acts downstream of pnr. (E) Wild-type Wg expression (green) is restricted to the anterolateral margins of the developing eye imaginal disc. (F) Random GOF clones of dve marked by GFP (blue) in the eye disc cause ectopic induction of Wg (green). The inset shows the magnified view of the clone. (G and H) Misexpression of dve (G) in the entire developing eye using an ey-Gal4 (ey > dve) and (H) on the DV margins using bi-Gal4 resulted in upregulation of the Wg protein level (green) and suppression of eye fate as seen by Elav (red) expression. (I) Misexpression of wg on DV margins using bi-Gal4 (bi > wg) did not induce Dve, suggesting that the dve gene acts upstream of wg. (J–M) In dve LOF clones, generated by a cell-lethal approach, modulating levels of Wg signaling by (J and K) misexpressing Wg in the eye results in highly reduced eye, whereas (L and M) misexpressing dTCFDN5, a dominant negative construct of TCF, results in ectopic dorsal eye enlargements. (N) Schematic representation of genes in the dorsal eye gene hierarchy.

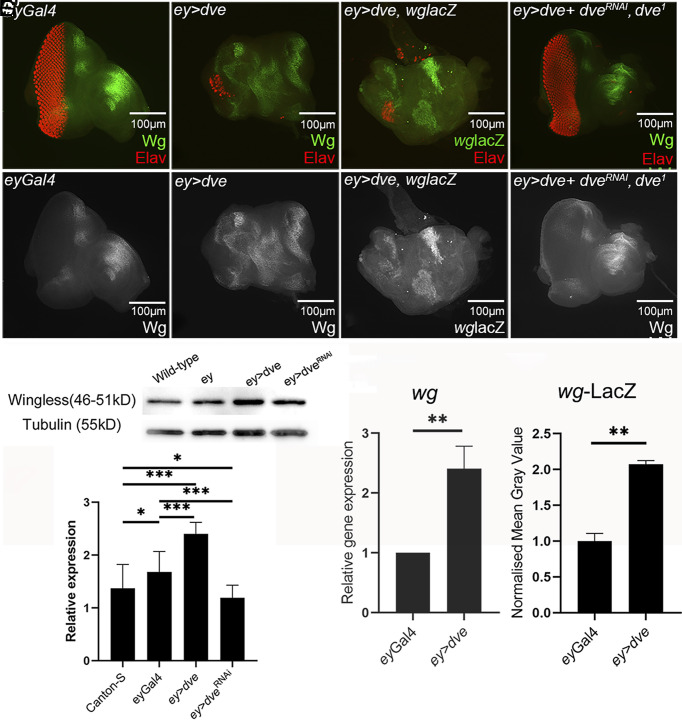

Using a transcriptional readout of wg (wg-lacZ reporter) (23), misexpression of dve in the posterior eye showed (fold change:~2 time, P-value: 0.002) ectopic wg-lacZ induction (ey > dve, Fig. 4 C–C” and G). It suggests that wg is a transcriptional target of Dve. GOF of dve (ey > dve) in the eye exhibits ectopic Wg induction (Fig. 4 B and B'). LOF of dve by the RNAi approach restored the “no-eye” phenotype of ey > dve +dveRNAi (Fig. 4D). Real-time quantitative PCR analysis revealed significant upregulation in wg mRNA (fold change: ~2.4, P-value: 0.009) (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, semiquantitative western blot analysis exhibits a ~two fold increase in Wg protein levels, respectively (Fig. 4 E and E’). Thus, our data suggest that during eye development, the DV patterning gene, dve acts downstream of pnr and upstream of wg and regulates wg expression (Figs. 3 and 4). Earlier, we have shown that Dve is also required for specification of the ocellar region (24). Dve expression in the early third larval instar depends on Orthodenticle (Otd) (24). However, otd mutation does not induce eye enlargement phenotype(s). This difference might be due to the Otd-independent and Pnr-dependent Dve expression induced in late first larval instar (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 4.

Dve induces Wg expression. (A and A’) Wild-type Wg expression in eyGAL4 control eye discs. (Fig. 4 B and B’) GOF of dve in the developing eye, using ey-Gal4 driver (ey > dve) results in upregulation of Wg (green) expression in the posterior margin of the eye disc. (C and C’) In addition, the transcriptional readout of the wg gene using lacZ reporter (green) showed ectopic induction in the posterior eye (C’) resulting in the reduced eye marked by panneural marker Elav (red) expression. (D and D’) LOF of dve by misexpressing dve RNAi in the developing eye, using ey-Gal4 (ey > UAS dveIR, dve[1]), ey domain shows (D) normal eye and head formation as evident from Elav (red) and (D’) Wg expression comparable to the wild type. (A’, B’, C’, and D’) show the individual Wg expression channel. (E and E’) Western blot image and analysis (E) blot shows Wg and tubulin levels in control groups, GOF and LOF of dve. (E’) Semiquantitative analysis shows changes in Wg levels. (F) Real-time qPCR analysis shows significant upregulation of wg upon misexpression of dve (ey > dve) when compared to ey-Gal4 control. (G) Quantitative analyses of wg levels (wg-LacZ) in the eye discs (n = 5, 20×) are represented as normalized mean gray values and show significant difference between dve GOF (ey > dve) and control (ey-Gal4) groups.

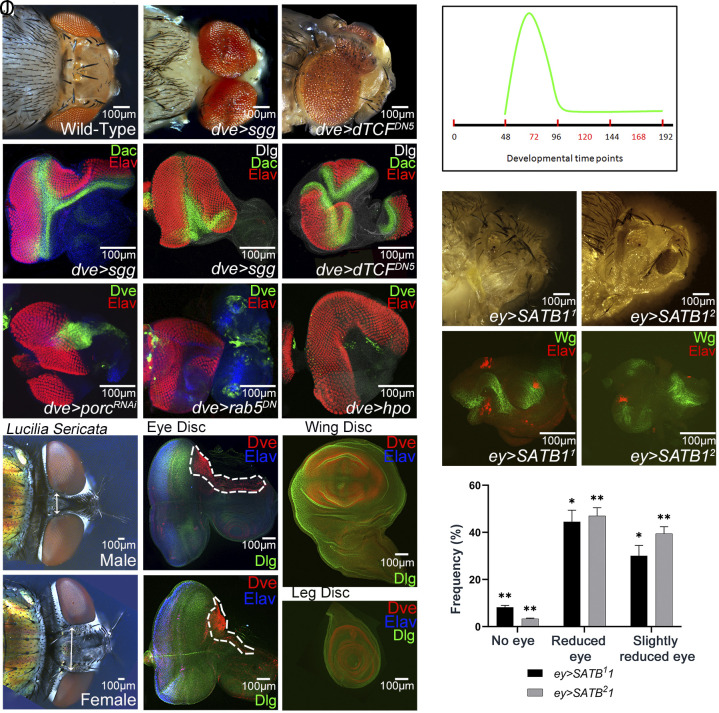

In the developing eye imaginal disc, wg, a negative regulator of eye development (4), plays an important role in regulating MF progression, thereby limiting the size of the eye versus head domains (4, 13). To further investigate its mechanism of action, we tested whether dve can regulate Wg signaling to regulate the eye versus head fate decision. We hypothesize that if wg acts downstream of dve, then blocking Wg signaling in dve-expressing cells should exhibit dorsal eye enlargements and mimic the dve LOF phenotype. Consistent with this hypothesis, misexpression of sgg or dTCFDN5, Wg antagonists in the dve expression domain (dve > sgg and dve > dTCFDN5), resulted in a nonautonomous phenotype of dramatic eye enlargements, where the entire head of the fly transforms into eyes such that even the head cuticle as well as antennae are transformed into eyes (Fig. 5 B and C). Other nonautonomous phenotypes include dorsal eye enlargements extending into the ocelli of the head (dve > sgg, Fig. 5D). In the eye disc, in addition to dorsal eye enlargements, which are caused by head-to-eye-specific fate change in the dorsal head vertex region, we observed nonautonomous phenotypes where an ectopic MF, which presents like a mirror image of the normal MF, is formed. This validates the hypothesis that the cells normally fated to form the head changed to a de novo eye fate, as confirmed by expression of a panneuronal fate marker Elav (dve > sgg, Fig. 5E). In rare cases, three different eye fields were observed in the same disc, which include the i) endogenous eye field, ii) ectopic eye on the dorsal head vertex, and iii) antenna to eye fate transformation (dve > dTCFDN5, Fig. 5F). Since the primordium, which later becomes the eye, antenna, and head, is initially specified to just the eye fate, changes in morphogen levels make the tissue susceptible to fate transformations and changes. Thus, blocking Wg signaling in the dve expression domain of the developing eye disc affects both the head and antennal fields and transforms them into ectopic eyes.

Fig. 5.

dve determines eye versus head fate through a conserved mechanism. (A–C) Dorsal view of adult head from (A) wild-type showing the ocellar region and the spacing of two eyes is compared to adult heads from (B) dve>sgg and (C) dve>dTCFDN in which Wg signaling is blocked. (D–F) Panels show eye discs in which misexpression of (D, E) Shaggy-kinase (dve>sgg) results in the transformation of head cuticle to eye fate. A comparison of D and E shows the range of phenotypes where in (D) ectopic eye enlargements in the dve domain results in the loss of head cuticle on the dorsal margin in the eye disc whereas in (E) a de novo eye field is generated in the anterior portion of the eye disc which results in a duplicated furrow marked by Dac (green) and duplication of the eye field as seen by Elav expression (red). In such discs the entire head forming region of eye disc changes to eye specific fate. (F) Eye disc showing misexpression of dominant negative TCF (dve>dTCFDN) also results in transformation of dorsal head cuticle and antenna to an eye fate and formation of de novo eye field as seen by expression of ELAV (red) that marks differentiated photoreceptor neurons and Dac (green) that marks the MF in the eye disc. (G, H) Blocking Wg transport from the dve expressing cells by (G) misexpressing porcupine-RNAi (dve>porcRNAi) and (H) a dominant negative form of rab5 (dve>rab5DN) shows similar eye enlargement (I) Eliminating dve expressing cells by misexpression of Hippo (dve>GFP+hpo) also resulted in huge enlargements of the eye field. Note that absence of GFP (green) reports the loss of dve expressing cells. (J) Using temperature sensitive Gal80ts allele, Gal4 mediated misexpression of UAS-transgene can be controlled. The graph displays the crucial developmental time point (~48-96 hours AEL) when dve expressing cells are required to delineate the eye and head fate. (K–O) SATB1, a human ortholog of Dve when misexpresssed in the developing eye imaginal disc using two independent SATB1 transgenes (ey>SATB11 ey>SATB21) suppresses (K, M) the eye formation in adults, and shows (L, N) induction of Wg (green) and eye suppression phenotype as marked by reduced Elav expression (red) in the eye discs. (O) Frequency analysis of the two eye suppression phenotypes of reduced eye and No-eye in adults when SATB1 is misexpressed (P–U) Conserved expression of Dve protein seen in Lucilia sericata, commonly known as blowfly, which exhibits sexual dimorphism in placement of eyes on head. (P, Q) The distance between the two eyes, separated by head cuticle, are shown (by double-sided arrow) in (P) male and (Q) female head. Note that the female eyes are more widely spaced than the males. (R, S) The eye imaginal disc from (R) male and (S) female larvae show a broader Dve expression domain in the antenna and dorsal head vertex region marked by white dotted line in female as compared to males. (T, U) Dve (red) expression is also highly conserved in the (T) wing and the (U) leg imaginal disc. (***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05).

These phenotypes also suggest that besides canonical Wg signaling, dve-expressing cells may affect paracrine Wg signaling (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) in the developing eye imaginal disc as well. Therefore, we prevented transport of Wg protein from the dve-expressing cells by down-regulating porcupine (25) (porcRNAi). The rationale was that dve-expressing cells are the site of Wg production from where Wg distribution/transport occurs to generate its morphogen gradient in the developing eye imaginal disc that leads to determination of the eye- versus head-specific fate. If the rationale is true, then blocking Wg transport from dve-expressing cells would result in a similar phenotype of dorsal eye enlargements as seen in dve LOF (Fig. 1 G and H). The dorsal eye enlargements were seen when Wg transport was blocked in dve-expressing cells by downregulation of porcRNAi (dve > porcRNAi, Fig. 5G), or by blocking endocytic transport using Rab5DN (26) (dve > rab5DN, Fig. 5H), or by eliminating the Dve-expressing cells by hippo misexpression (27, 28) that triggers cell death (dve > hpo, Fig. 5I). Next, we tested the role of dve in regulating Wg signaling by killing these cells using ricin (29) (dve > Gal80ts+ricin) in short time windows (developmental time intervals) during development using the Gal80ts TARGET strategy (30). These experiments revealed that dve function during the second larval instar of development (48 to 96 h) critically regulates Wg signaling (Fig. 5J). Thus, during second larval instar of development, DV patterning gene dve functions in determining the eye versus head fate by controlling Wg levels in the eye imaginal disc, which in turn regulates the interocular distance or placement of the eye on the head. In the developing eye, signals are under timely control by upstream gene regulators reiterating the importance of cross talk between patterning genes and signaling pathways (31, 32).

Next, to test whether dve function in regulation of the interocular distance is evolutionarily conserved, we took two approaches: First, we tested transgenic Drosophila that express SATB1, the human ortholog of dve. Misexpression of two independent SATB1 transgenic lines in the eye (ey > SATB11, ey > SATB21) results in eye suppression phenotype(s) similar to the GOF of dve, suggesting that these genes are functionally conserved during eye development (Fig. 5 K and M). GOF of SATB1 exhibits a range of eye suppression phenotypes (Fig. 5O) along with Wg induction (Fig. 5 L and N).

Diffusible signaling molecules are recycled and reused in various developmental processes. The mechanism by which dve regulates Wg signal has fundamental morphological consequences of delineation of eye versus head boundary. A highly conserved dve sequence observed across the Drosophila species (SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6 and Table S1) led us to compare dve expression in the eye- and wing-imaginal discs in other Drosophila species. Notably, Dve expression is conserved in the dorsal head vertex region in eye discs and wing pouch region of wing discs from other Drosophila species along the evolutionary scale (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). To further investigate the dve expression profile, we tested expression of Dve in Lucilia sericata, a fly with a sexually dimorphic trait of the interocular distance (33, 34) between the eyes on the head. The interocular distance is larger in females as compared to males (Fig. 5 P and Q). In the eye imaginal discs from the sexed larvae, we found that Dve expression domain on the dorsal head vertex is broader in females as compared to males (Fig. 5 R and S). Thus, dve expression plays an important role in determining the eye versus head fate and interocular distance in the developing insect eyes. Additionally, Dve expression is also conserved in the wing and leg imaginal discs of L. sericata (Fig. 5 T and U). Furthermore, we found that similar to Homothorax (Hth) (35), dve expression is observed in the extended stalk of the stalk-eyed fly where the eyes are placed on laterally extended stalks. This study only showed that dve expression and sequence are highly conserved in stalk-eyed flies (36). Loss of Wnt signaling has been reported to cause hypertelorism, which affects the interocular distance in patients and implicated in defective craniofacial development (6, 37). Changes in the levels of morphogens like Wnt/Wg are known to impact basic cellular processes like patterning, proliferation, and growth. During organogenesis, WNT signaling gradient plays vital roles in deciding the placement of internal organs in the body cavity; any deviation results in situs inversus where body parts are mislocalized such as the heart is on the right side (38–40). Therefore, such changes in signaling levels can directly impact the interocular distance during eye development and can exhibit phenotypes similar to orbital hypertelorism. Orbital hypertelorism is defined as increased distance between the eye orbits and can also result in abnormal placement of the eye (dystopia) (41, 42). This usually manifests with other developmental deformities of the eye and brain. Several studies have shown the importance of Wnt/Wg gradient and signaling during eye and craniofacial development (6, 41). Signaling and movement of morphogens have significant implications in establishing basic patterning (5, 43), facial morphology, and can cause developmental defects like hypertelorism, facial defects, cleft palate, etc. (6, 37, 44).

In our study, we show that a transcription factor, Dve, the Drosophila ortholog of human SATB1, has a conserved function in regulating the transcription of wg and thereby regulating the Wg morphogen gradient from a subset of cells in the developing eye–antennal imaginal disc to determine the placement of eyes on the head. Even though pnr acts upstream of dve in dorsal gene hierarchy, the role of Dve to regulate the Wg morphogen gradient is unique to dve. This is because pnr LOF or blocking Wg signaling in Pnr expression domain only showed dorsal eye enlargement whereas blocking Wg signaling in Dve-expressing cells changes the entire eye–antennal field to an eye (Fig. 5). In a study in humans, 42 individuals with a rare pathogenic variant in the SATB1 gene (MIM:602075; Gen Bank: NM001131010.4) were reported to show phenotypes of neurodevelopmental delay (97%), epilepsy (61%), facial dysmorphism (67%), and vision defects (55%). Furthermore, a patient with SATB1 E413K missense mutation showed hypertelorism along with other facial dysmorphic features (45). Our results also provide evidence for the role that SATB1 ortholog Dve plays in determining the variation in the interocular distance among different species by regulating wg. These studies using Dve/SATB1 uncover a regulatory mechanism that controls interocular distance during craniofacial development by regulating morphogen signaling by a transcription factor. Future studies are warranted to further dissect out other complex interactions during eye development and growth.

Methods

Fly Stocks.

The stocks used in this study are listed in FlyBase (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu). The fly stocks are ey-Gal4 (23), bifid (bi)-Gal4 (12, 46), UAS-dve(16), UAS-dve-IR dve1(16, 47), FRT42D dve1(48), UAS-pnrD4 (49), UAS-pnrENR (50), y, w; FRT82B pnrvx6/CyO (46), UAS-wg (51), UAS-sggS9A, UAS-dTCFDN(52), eyFLP; FRT82B Ubi-GFP, UAS-porcRNAi (25), UAS-Rab5DN (26), UAS-hpo (27, 28), UAS-ricin (29), UAS-SATB11, UAS-SATB21, dveGal4GFP/CyO; Gal80ts/Tb, and wg-lacZ/CyO (23), a lacZ reporter which serves as the functional readout of the Wg signaling pathway. We used the Gal4/UAS system for targeted misexpression studies (53). All Gal4/UAS crosses were maintained at 25/29 °C. The adult flies from crosses were maintained at 25 °C, while the cultures after egg laying (progeny) were transferred to 25/29 °C for further growth (54, 55). The ey-Gal4 driver line directs expression of responder transgenes in the differentiating retinal precursor cells of the developing Drosophila eye imaginal disc. The bi-Gal4 directs expression in the dorsal and ventral eye and along the A/P axis of the wing. Other organisms used in this study include Drosophila species such as D. melanogaster, D. yakuba, D. ananassae, D. virilis, D. pseudoobscura, and D. willistoni and blow fly, L. sericata.

Genetic Crosses.

The Gal4/UAS system was used to misexpress the gene of interest (53). All crosses were maintained at 18 °C, 25 °C, and 29 °C, unless specified, to sample different induction levels. A temperature-sensitive Gal80ts system (30) was used to restrict the expression of a UAS-transgene of interest spatially and temporally.

Genetic Mosaic Analysis.

The FLP/FRT system of mitotic recombination (19) was used to generate LOF clones of pnr in the eye. eyFLP; FRT82B Ubi-GFP females were crossed to y, w; FRT82B pnrvx6 males. LOF clones (56) of dve in the eye were generated using a cell-lethal approach by crossing virgins of eyFlp; FRT42D, cl-w+/CyO-GFP to males of FRT42D dve1. GOF clones of pnr and dve were generated using the hs-FLP method by crossing y, w, hsFLP122; P(Act > y+ > Gal4) 25 P(UAS-GFPS65T)/CyO (57) flies to UAS-pnrD4 or UAS-dve flies, respectively, and heat shock at 37 °C.

Immunohistochemistry.

Eye–antennal imaginal discs were dissected from wandering third-instar larvae in 1× PBS and stained following standard protocol (54, 58). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-β-GAL (1:100; Cappel); rat anti-Elav (1:100), mouse anti-Wg (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, DSHB), mouse anti-Disc large (1:100; DSHB); rabbit anti-Ey (1:200, a gift from Uwe Walldorf and Patrick Callaerts), mouse anti-Eya (1:100; DSHB), mouse anti-Dac (1:100; DSHB), and anti-Rabbit Dve (1:200). Secondary antibodies (Jackson Laboratories) used consisted of donkey anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Cy3 (1:250), donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Cy3 (1:250), and goat anti-rat IgG conjugated with Cy5 (1:200). The tissues were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Labs), and all the immunofluorescence images were captured using the Olympus FluoView 1000 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope.

Western Blot.

Protein samples were prepared using the adult Drosophila heads from wild-type, ey-Gal4, ey-Gal4 > UAS-dve, and ey-Gal4 > UAS dve-IR dve1 following the standardized protocol (59, 60). The protein samples were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and quantified using Nanodrop. The samples were normalized and loaded in wells of a 10% Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. The primary antibodies used were anti-mouse Wg (1:1,000, 4D4, DSHB) and anti-mouse tubulin (1:12,000, Sigma-Aldrich Corp.), and secondary antibodies horseradish peroxidase–conjugated anti-Mouse IgG-HRP (1:5,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The signal was detected using the supersignal chemiluminescence substrate kit (Pierce Biotechnology, ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL USA), and the images were captured using the LI-COR Odyssey® XF.

Real-Time qPCR (RT-qPCR).

Drosophila eye imaginal discs (n = 80) for ey-Gal4 and ey > dve were collected and homogenized in TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Cat# 15596026) to extract the total RNA (61). The quality and quantity of the RNA were determined using the Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Using the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (GE Healthcare, Cat# 27926101), 1 µg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis. Real-time qPCR was performed using Bio-Rad iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Cat# 1708860) according to the standard protocol (61, 62). Fold change was calculated using the comparative ΔΔCT method (fold change = 2−ΔΔCT). All samples were run in triplicates (n = 3). Statistical significance was determined at 95% confidence (P < 0.05) using Student’s t test.

Primers:

GAPDHFw5′-GGCGGATAAAGTAAATGTGTGC-3′

GAPDHRev5′-AGCTCCTCGTAGACGAACAT-3′

wgFw5′-TCAGGGACGCAAGCATAATAG-3′

wgRev5′-CGAAGGCTCCAGATAGACAAG-3′

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for Drosophila strains and the DSHB for antibodies. We thank Hugo Bellen and Shinya Yamamoto for the gift of fly strains. Confocal microscopy was supported by the core facility at the University of Dayton. A.S. is supported by 1RO1EY032959-01 from the NIH, Schuellein Chair Endowment Fund, and STEM Catalyst Grant from the University of Dayton. M.K.-S. is supported by 1RO1EY032959-01 from the NIH.

Author contributions

M.K.-S. and A.S. designed research; O.R.P., N.G., A.V.C., and A.S. performed research; T.Y., H.N., M.K.-S., and A.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; O.R.P., A.V.C., H.N., M.K.-S., and A.S. analyzed data; and A.S. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Wallingford J. B., Mitchell B., Strange as it may seem: The many links between Wnt signaling, planar cell polarity, and cilia. Genes. Dev. 25, 201–213 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swarup S., Verheyen E. M., Wnt/Wingless signaling in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a007930 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zecca M., Basler K., Struhl G., Direct and long-range action of a wingless morphogen gradient. Cell 87, 833–844 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legent K., Treisman J. E., Wingless signaling in Drosophila eye development. Methods Mol. Biol. 469, 141–161 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cordero D., et al. , Temporal perturbations in sonic hedgehog signaling elicit the spectrum of holoprosencephaly phenotypes. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 485–494 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki A., Sangani D. R., Ansari A., Iwata J., Molecular mechanisms of midfacial developmental defects. Dev. Dyn. 245, 276–293 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogia N., Puli O. R., Raj A., Singh A., “Generation of third dimension: Axial patterning in the developing Drosophila eye” in Molecular Genetics of Axial Patterning, Growth and Disease in the Drosophila Eye, Singh A., Kango-Singh M., Eds. (Springer, Springer New York, 2020), vol. II, pp. 53–95. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh A., Choi K.-W., Initial state of the Drosophila eye before dorsoventral specification is equivalent to ventral. Development 130, 6351 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurel-Zaffran C., Treisman J. E., pannier acts upstream of wingless to direct dorsal eye disc development in Drosophila. Development 127, 1007–1016 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oros S. M., Tare M., Kango-Singh M., Singh A., Dorsal eye selector pannier (pnr) suppresses the eye fate to define dorsal margin of the Drosophila eye. Dev. Biol. 346, 258–271 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baonza A., Freeman M., Control of Drosophila eye specification by Wingless signalling. Development 129, 5313–5322 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tare M., Puli O. R., Moran M. T., Kango-Singh M., Singh A., Domain specific genetic mosaic system in the Drosophila eye. Genesis 51, 68–74 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Treisman J. E., Rubin G. M., wingless inhibits morphogenetic furrow movement in the Drosophila eye disc. Development 121, 3519–3527 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma C., Moses K., Wingless and patched are negative regulators of the morphogenetic furrow and can affect tissue polarity in the developing Drosophila compound eye. Development 121, 2279–2289 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ready D. F., Hanson T. E., Benzer S., Development of the Drosophila retina, a neurocrystalline lattice. Dev. Biol. 53, 217–240 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagoshi H., Hoshi M., Nabeshima Y., Matsuzaki F., A novel homeobox gene mediates the Dpp signal to establish functional specificity within target cells. Genes. Dev. 12, 2724–2734 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuss B., Hoch M., Drosophila endoderm development requires a novel homeobox gene which is a target of Wingless and Dpp signalling. Mech. Dev. 79, 83–97 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng Y. R., et al. , Satb1 regulates contactin 5 to pattern dendrites of a mammalian retinal ganglion cell. Neuron 95, 869–883.e6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu T., Rubin G. M., Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development 117, 1223–1237 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newsome T. P., Asling B., Dickson B. J., Analysis of Drosophila photoreceptor axon guidance in eye-specific mosaics. Development 127, 851–860 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar J. P., My what big eyes you have: How the Drosophila retina grows. Dev. Neurobiol. 71, 1133–1152 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halder G., Callaerts P., Gehring W. J., Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila. Science 267, 1788–1792 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazelett D. J., Bourouis M., Walldorf U., Treisman J. E., decapentaplegic and wingless are regulated by eyes absent and eyegone and interact to direct the pattern of retinal differentiation in the eye disc. Development 125, 3741–3751 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yorimitsu T., Kiritooshi N., Nakagoshi H., Defective proventriculus specifies the ocellar region in the Drosophila head. Dev. Biol. 356, 598–607 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manoukian A. S., Yoffe K. B., Wilder E. L., Perrimon N., The porcupine gene is required for wingless autoregulation in Drosophila. Development 121, 4037–4044 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J., et al. , Thirty-one flavors of Drosophila rab proteins. Genetics 176, 1307–1322 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Udan R. S., Kango-Singh M., Nolo R., Tao C., Halder G., Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 914–920 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verghese S., Waghmare I., Kwon H., Hanes K., Kango-Singh M., Scribble acts in the Drosophila fat-hippo pathway to regulate warts activity. PLoS One 7, e47173 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hidalgo A., Urban J., Brand A. H., Targeted ablation of glia disrupts axon tract formation in the Drosophila CNS. Development 121, 3703–3712 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McGuire S. E., Le P. T., Osborn A. J., Matsumoto K., Davis R. L., Spatiotemporal rescue of memory dysfunction in Drosophila. Science 302, 1765–1768 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Morales J. R., Cavodeassi F., Bovolenta P., Coordinated morphogenetic mechanisms shape the vertebrate eye. Front. Neurosci. 11, 721 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wartlick O., Julicher F., Gonzalez-Gaitan M., Growth control by a moving morphogen gradient during Drosophila eye development. Development 141, 1884–1893 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Land M. F., Nilsson D.-E., Animal Eyes (Oxford University Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sukontason K. L., et al. , Ommatidia of blow fly, house fly, and flesh fly: Implication of their vision efficiency. Parasitol Res. 103, 123–131 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh A., Gogia N., Chang C. Y., Sun Y. H., Proximal fate marker homothorax marks the lateral extension of stalk-eyed fly Cyrtodopsis whitei. Genesis 57, e23309 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carr M., Hurley I., Fowler K., Pomiankowski A., Smith H. K., Expression of defective proventriculus during head capsule development is conserved in Drosophila and stalk-eyed flies (Diopsidae). Dev. Genes. Evol. 215, 402–409 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu B., Chen S., Johnson C., Helms J. A., A ciliopathy with hydrocephalus, isolated craniosynostosis, hypertelorism, and clefting caused by deletion of Kif3a. Reprod. Toxicol. 48, 88–97 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dale R. M., Sisson B. E., Topczewski J., The emerging role of Wnt/PCP signaling in organ formation. Zebrafish 6, 9–14 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lienkamp S., Ganner A., Walz G., Inversin, Wnt signaling and primary cilia. Differentiation 83, S49–S55 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakaya M. A., et al. , Wnt3a links left-right determination with segmentation and anteroposterior axis elongation. Development 132, 5425–5436 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brugmann S. A., et al. , Wnt signaling mediates regional specification in the vertebrate face. Development 134, 3283–3295 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma R. K., Hypertelorism. Ind. J. Plast. Surg. 47, 284–292 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cordero D., Tapadia M., Helms J. A., “Sonic Hedgehog signaling in craniofacial development” in Hedgehog-Gli Signaling in Human Disease, A. Ruiz i Altaba, Ed. (Springer, Boston, MA, 2006), pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Demyer W., Zeman W., Palmer C. G., The face predicts the brain: Diagnostic significance of median facial anomalies for holoprosencephaly (Arhinencephaly). Pediatrics 34, 256–263 (1964). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.den Hoed J., et al. , Mutation-specific pathophysiological mechanisms define different neurodevelopmental disorders associated with SATB1 dysfunction. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 346–356 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heitzler P., Haenlin M., Ramain P., Calleja M., Simpson P., A genetic analysis of pannier, a gene necessary for viability of dorsal tissues and bristle positioning in Drosophila. Genetics 143, 1271–1286 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minami R., et al. , The homeodomain protein defective proventriculus is essential for male accessory gland development to enhance fecundity in Drosophila. PLoS One 7, e32302 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakagoshi H., Shirai T., Nabeshima Y., Matsuzaki F., Refinement of wingless expression by a wingless- and notch-responsive homeodomain protein, defective proventriculus. Dev Biol 249, 44–56 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haenlin M., et al. , Transcriptional activity of pannier is regulated negatively by heterodimerization of the GATA DNA-binding domain with a cofactor encoded by the u-shaped gene of Drosophila. Genes. Dev. 11, 3096–3108 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klinedinst S. L., Bodmer R., Gata factor Pannier is required to establish competence for heart progenitor formation. Development 130, 3027–3038 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azpiazu N., Morata G., Functional and regulatory interactions between Hox and extradenticle genes. Genes. Dev. 12, 261–273 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van de Wetering M., et al. , Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell 88, 789–799 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brand A. H., Perrimon N., Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh A., Kango-Singh M., Sun Y. H., Eye suppression, a novel function of teashirt, requires Wingless signaling. Development 129, 4271–4280 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh A., Shi X., Choi K. W., Lobe and Serrate are required for cell survival during early eye development in Drosophila. Development 133, 4771–4781 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blair S. S., Genetic mosaic techniques for studying Drosophila development. Development 130, 5065–5072 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Struhl G., Basler K., Organizing activity of wingless protein in Drosophila. Cell 72, 527–540 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wittkorn E., Sarkar A., Garcia K., Kango-Singh M., Singh A., The Hippo pathway effector Yki downregulates Wg signaling to promote retinal differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Development 142, 2002–2013 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gogia N., Sarkar A., Singh A., An undergraduate cell biology lab: Western Blotting to detect proteins from Drosophila eye. Dros. Inf. Serv. 100, 218–225 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deshpande P., et al. , N-Acetyltransferase 9 ameliorates Abeta42-mediated neurodegeneration in the Drosophila eye. Cell Death Dis. 14, 478 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehta A. S., Luz-Madrigal A., Li J. L., Panagiotis T. A., Singh A., Total RNA extraction from transgenic flies misexpressing foreign genes to perform Next generation RNA sequencing. protocols. io 1–3 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehta A., Singh A., Real time quantitative PCR to demonstrate gene expression in an undergraduate lab. Dros. Inf. Serv. 100, 5 (2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.