Abstract

There is increasing clinical and experimental evidence that inflammation and cancer are causally linked. Much progress has been made in understanding how inflammatory cells contribute to cancer development; however, it is still largely unknown which molecular mechanisms are responsible for initiation and maintenance of chronic inflammation associated with developing neoplasms. This review will discuss how the adaptive and innate immune systems interact during physiological and chronic inflammation, with a focus on studies revealing new insights into the role of adaptive immune cells as important regulators of chronic inflammation-associated carcinogenesis. We will speculate on whether current knowledge about the dysregulated interplay between adaptive and innate immunity during chronic inflammatory disorders might be useful in understanding and targeting the underlying mechanisms of chronic inflammation-associated neoplastic progression.

Keywords: Cancer, Inflammation, Adaptive immune system, Innate immune system, Premalignant, Antibody

Introduction

Cancer arises as a consequence of accumulating genetic alterations that are necessary, but not sufficient for malignant progression [1]. Numerous host cells, such as inflammatory cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts, are recruited to and activated in the microenvironment of a developing tumor. Subsequent reciprocal interactions between these responding “normal” host cells, their mediators and genetically altered “initiated” cells are indispensable for carcinogenesis. Clinical and experimental data indicate a strong promoting role for innate immune cells in neoplastic progression [2]. Innate immune cells contribute to early neoplastic development and potentiate tumorigenesis by producing a myriad of soluble growth factors, cytokines and chemokines as well as various types of extracellular or cell-associated proteinases, especially matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [3–8]. Although there is a growing understanding of the mechanisms by which innate immune cells potentiate tumor development, the initiating events causing chronic inflammation in the tumor microenvironment are still poorly understood.

Over the last decade, much progress has been made in delineating the mechanisms underlying pathogenesis of autoimmune disease; these studies have revealed that dysregulated mobilization of the adaptive immune system is one of the initial events resulting in excessive stimulation of tissue-damaging innate immune responses [9–14]. In this review, we discuss the different pathways via which the innate and adaptive immune systems are connected, and how aberrant activation of adaptive and innate immunity can lead to the development of chronic inflammatory diseases. We will discuss whether knowledge obtained from the autoimmune field might be applicable to inflammation-associated carcinogenesis. We will focus on our recent data supporting the concept that the adaptive immune system functionally contributes to inflammation-associated carcinogenesis and will discuss potential therapeutic implications.

Comparison of innate and adaptive immunity

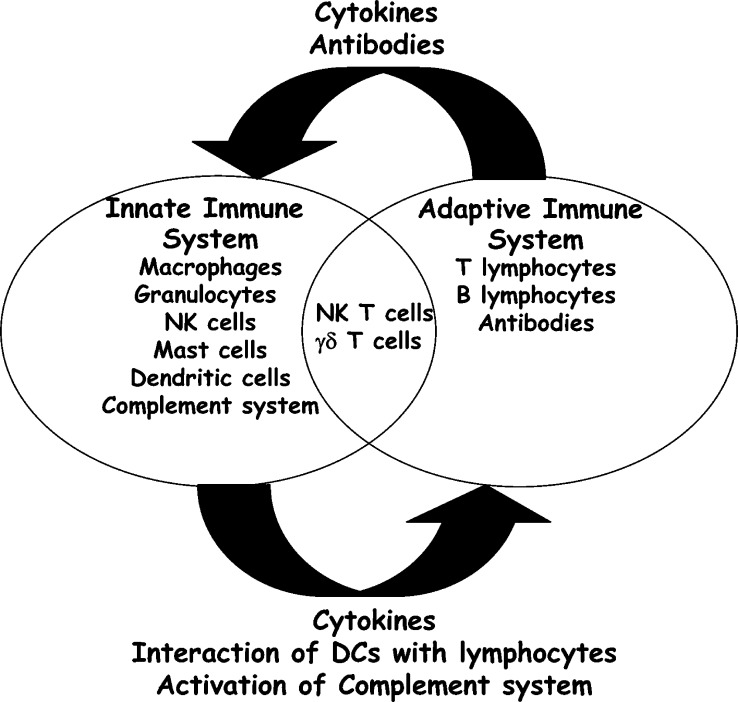

The immune system is composed of a large variety of cells and mediators that interact in a complex and dynamic network to ensure protection against all foreign pathogens possibly encountered during life-time, while simultaneously maintaining self-tolerance. The immune system can be divided into two subsets, the innate immune system, also referred to as the first line of immune defense against infection, and the adaptive immune system (Fig. 1). Innate immune cells, e.g., granulocytes (neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils), dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, natural killer cells (NK cells) and mast cells, express germline encoded pattern-recognition Toll-like receptors (TLRs) with which they recognize conserved molecular patterns, e.g., lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoteichoic acid (LTA), mannans, unmethylated CpG DNA motifs and glycans, found on microbes but not in self-tissue [15]. Activation of TLRs triggers a cascade of intracellular events, including activation of NF-κB signaling pathways, resulting in increased production of proinflammatory mediators, increased nitric oxide synthesis and increased antigen presentation, thus, further enhancing recruitment and activation of additional leukocytes [15]. In addition, activation of the complement system, represented by a complex network of more than 30 serum proteins and cell surface receptors, is a central event during innate immune defense after pathogenic tissue assault [16–18]. Activation of the complement system by pathogens and immune complexes results in lysis of foreign cells and bacteria, opsoniziation and uptake of complement-coated antigens by phagocytosis, recruitment of innate immune cells via engagement of complement receptors and clearance of immune complexes [17, 18]. These different pathways of innate immune cell activation not only form the first line of immune defense against invading pathogens, but are also involved in activation and modulation of more specific adaptive immune responses [19, 20].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the interplay between innate and adaptive immunity. The immune system can be divided into two subsets, the innate immune system, also referred to as the first line of immune defense against infection, and the adaptive immune system. The innate immune system consists of macrophages, granulocytes (neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils), natural killer cells (NK cells), mast cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and soluble factors, e.g., complement components. The adaptive immune system consists of T and B lymphocytes and antibodies. NK T cells and γδ T cells are present at the intersection between adaptive and innate immunity. Crosstalk between the two branches of the immune system is mediated by complex interactions between cells of both immune subsets and their soluble factors. The innate immune system regulates adaptive immune responses by the production of cytokines, interaction between DCs and lymphocytes, and activation of the complement system. The adaptive immune system modulates innate immune responses by cytokine and antibody production

In contrast to innate immune cells that express germ-line encoded receptors, adaptive immune cells, e.g., B and T lymphocytes, express highly diverse, somatically generated, antigen-specific receptors. T cell receptors (TCRs) and B cell receptors (BCRs) are generated by random rearrangement of the T cell receptor and Immunoglobulin (Ig) gene segments, respectively, allowing generation of extremely diverse T and B lymphocyte repertoires that provide organisms with a flexible and broader repertoire of responses to pathogens as compared to the innate immune system [21, 22]. Mature B lymphocytes can undergo additional processes upon initial activation resulting in modifications in their capacity to recognize antigens, i.e., somatic hypermutation of Ig genes, Ig affinity maturation and Ig class switching (isotype switching) [23]. The two major T lymphocyte subsets, e.g., CD4+ T cells (helper T cells) and CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic T cells), are activated upon interaction of their TCRs with nonself antigens presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and I, respectively, in combination with simultaneous interactions with costimulatory molecules [24]. Fully activated T lymphocytes subsequently exert various effector functions such as cytokine production, B cell help (CD4+ T cells) and cytotoxic killing of cells expressing the antigen of specificity (CD8+ T cells). On the other hand, B lymphocytes recognize soluble antigens, require additional signals derived from helper T cells for full activation and subsequently exert their effector function by secreting antibodies with the same antigen specificity as the BCR [23, 24]. As individual B and T lymphocytes are antigenically committed to a specific unique antigen, clonal expansion of antigen-specific lymphocytes is required upon antigen recognition to obtain a sufficient number of antigen-specific T and/or B lymphocytes to counteract infection [23, 25]. Therefore, the kinetics of primary adaptive immune responses are slower than innate immune responses; however, during a primary adaptive immune response, a subset of lymphocytes differentiates into long-lived memory cells resulting in heightened states of immune reactivity to subsequent exposure with the same antigen [25].

Crosstalk between adaptive and innate immunity

Although the adaptive and innate immune systems are well-defined separate defense systems, each comprised of unique cell populations and different in their antigen specificity and response kinetics, they are tightly connected (Fig. 1). Tissue homeostasis and efficient protection against pathogens can only be achieved by extensive interactions between both arms of the immune system since dysregulation of the interplay can have serious consequences for an organisms’ well-being. Crosstalk between the two branches of the immune system is mediated by complex interactions between cells of both immune subsets, and their soluble factors. During acute inflammatory reactions, e.g., pathogen exposure, the innate immune system activates and regulates the adaptive immune system; however, this scenario can be reversed during chronic inflammatory conditions in which dysregulated adaptive immune responses can mediate chronic innate immune responses culminating in tissue damage.

Crosstalk between adaptive and innate immunity during acute immune responses

In response to pathogens or “danger signals,” resident innate immune cells immediately alert the immune system by producing a large array of cytokines [19]. Cytokines are the major factors of immune defense regulating crosstalk between the diverse players of the immune system. Cytokines produced by innate immune cells during acute immune responses include, but are not limited to, type I interferon (IFN), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IFN-γ, interleukin (IL)-12, −15 and −18, that promote differentiation and activation of immature DCs, B and T lymphocytes, and thus represent key players in the communication between innate and adaptive immune cells [19, 26, 27]. It is beyond the scope of this report to discuss the complex pleiotropy and apparent redundancy of cytokine actions in detail; however, it is important to recognize the central role of cytokine-regulated pathways in mobilizing both innate and adaptive immune systems during acute tissue assault by pathogens as illustrated by increased susceptibility to bacterial infections of patients with cytokine or cytokine receptor deficiencies [28].

Besides the presence of a proinflammatory cytokine repertoire, activation of naive T lymphocytes requires direct contact with innate, professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [29]. DCs are the most potent type of APCs and play a crucial role in crosstalk between innate and adaptive immunity [27]. DCs are widely dispersed throughout the body and act as sentinel cells that constitutively monitor their microenvironment for danger signals [30]. Maturation and activation of DCs is largely driven by the local cytokine milieu and pathogenic antigens. Upon initial activation, DCs undergo maturation during which they process acquired antigens and migrate to secondary lymphoid organs where they present processed antigens in MHC class I and II molecules to naïve CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes, respectively [24]. For effective T cell priming, additional interactions of naïve T cells with costimulatory molecules, e.g., CD80, CD86, OX40L, CD40 and 4-1BBL, expressed on mature DCs are required [31]; thus, DCs are indispensable players at the intersection of innate and adaptive immunity.

Cells and soluble mediators of the innate immune system also regulate humoral immune responses. B lymphocytes have the capacity to recognize soluble foreign antigens; however, they are more efficiently primed by antigens presented by DCs [23]. Cross-linking of BCRs by foreign antigens, combined with signals derived from cytokines from activated T helper cells and innate immune cells, are important steps in the induction of efficient humoral immunity. The complement system also play an important role in shaping humoral immune responses [20]. Studies in various complement deficient mice have demonstrated the importance of the complement system during B cell differentiation and activation, as these mice have altered B lymphocyte repertoires and impaired humoral responses towards foreign and self-antigens [20]. Taken together, during acute tissue damage, e.g., pathogenic tissue assault, adaptive immune responses are dependent on and shaped by innate immune responses; however, under certain pathological circumstances, this scenario is reversed and the adaptive immune system can actually induce over stimulation of innate immune responses [10–14].

Crosstalk between adaptive and innate immunity during chronic inflammation

Mechanistic studies of physiologic inflammatory disorders have revealed that dysregulated interactions between adaptive and innate immunity can result in excessive activation of the immune system and chronic inflammation culminating in tissue damage [10–14]. Various inflammatory cell populations participate in ongoing inflammatory reactions, but in particular, strong evidence for a critical role of B lymphocytes in disease pathogenesis has been reported. Deposition of autoantibodies or immune complexes in tissues affected by autoimmune disease, such as in bullous pemphigoid (skin) and in joints with rheumatoid arthritis, is a common and well-described phenomenon [32, 33]. Only recently, however, have data revealed that antibody-deposits are not merely secondary consequences of tissue changes, but frequently play a central role in regulating disease pathogenesis [10–14]. Accumulation of antibodies in afflicted tissues can trigger a cascade of inflammation and chronic activation of innate immune cells via activation of the complement system and/or via activation of Fc receptors (FcRs), resulting in tissue damage. Activation of the antibody-dependent classical complement pathway results in the formation of antigen-antibody-complement complexes and formation and release of anaphylatoxins, e.g., C3a and C5a, potent proinflammatory factors that induce the recruitment and the activation of innate immune cells via cross-linking of complement receptors [16]. Direct evidence for the importance of the antibody-mediated complement-dependent pathway in regulating chronic inflammation and autoimmunity has been underscored by the studies utilizing complement-depleted and complement component C3- or C5-deficient mice [10, 34, 35]. These studies have revealed that failure to activate the complement cascade completely or partially protects mice from various antibody-mediated inflammatory pathologies including experimental airway hyperresponsiveness [34], subepidermal blistering disease [35] and arthritis [10]. Thus, complement activation plays a central role in regulating inflammatory disease pathogenesis by connecting the (dysregulated) humoral immune system with the innate immune system, culminating in tissue damage.

Direct interaction of antibodies with antibody binding surface receptors, e.g., IgG Fc receptors (FcγRs) I, -II, and –III, expressed on inflammatory cells triggers various cellular responses, including phagocytosis, antigen-presentation, secretion of proinflammatory mediators and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity [36, 37]. Analyses of FcRγ-deficient mice revealed complete or partial resistance to experimental (auto-) antibody-dependent inflammation and tissue damage, such as arthritis [10], Arthus reaction [38], vasculitis [39] and glomerulonephritis [40] underscoring the importance of FcRs in the crosstalk between humoral and innate immunity.

Compelling evidence for a critical role of B lymphocytes in some human autoimmune diseases comes from clinical studies showing beneficial therapeutic effect of specific pharmaceutical interventions targeting B lymphocytes [9]. Recent clinical trials indicate that B lymphocyte depletion is therapeutic and well tolerated in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [41], chronic idiopathic thrombocytoempenia [42], autoimmune hemolytic anemia [43] and systemic lupus erythomatosus (SLE) [44]. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that chronic inflammation and tissue damage often arise as a consequence of humoral immunity-mediated excessive stimulation of innate immune cells.

Interplay between adaptive and innate immunity regulates carcinogenesis

Inflammation and cancer

Over the past decade, accumulating clinical and experimental studies have indicated a causal link between inflammation and cancer [2]. Infiltration of leukocytes into the neoplastic microenvironment is a common feature of many epithelial malignancies. Whereas infiltration of tumors with T lymphocytes is beneficial for cancer patients [45–48], extensive analysis of human tumor samples has revealed that abundance of innate immune cells, in particular, mast cells and macrophages, correlates with angiogenesis and poor prognosis [49–53]. The significance of inflammation associated with cancer development is further underscored by the realization that chronic inflammatory conditions predispose humans to certain cancers. For example, inflammatory bowel disease has been associated with colon cancer, chronic pancreatitis with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and hepatitis with hepatocellular carcinoma [54]. Moreover, long-term usage of anti-inflammatory drugs significantly reduces the risk of various malignancies [55, 56]. These clinical data indicate that inflammation can contribute to carcinogenesis; however, mechanistic pathways mediating the interplay between inflammation and cancer are not revealed by these clinical observations.

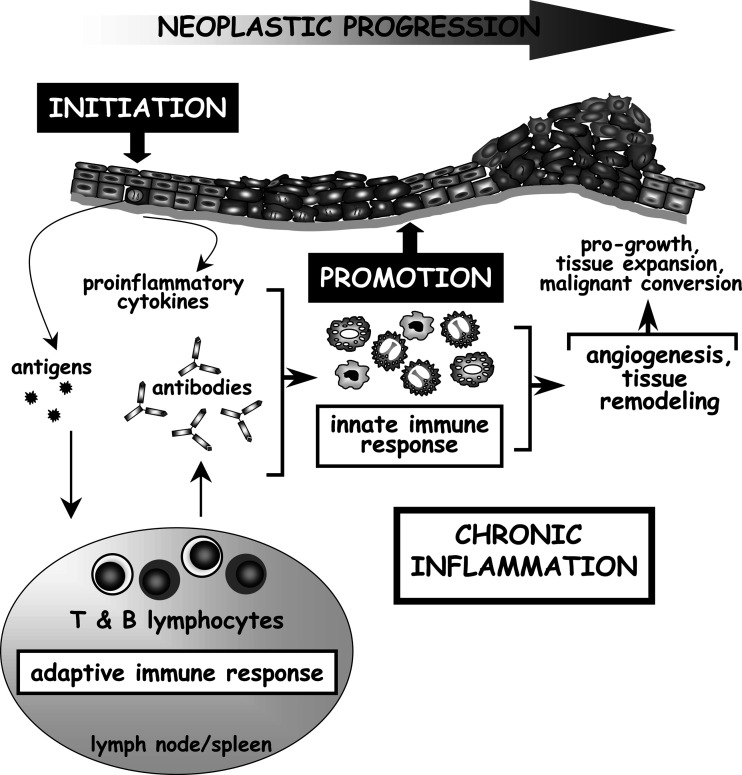

The availability of a growing number of de novo carcinogenesis mouse models has allowed us to take the first step towards understanding the complex mechanisms behind the causal link between chronic inflammation and premalignant progression, tumor growth and metastasis formation [2–5, 7, 55, 57]. Utilizing a transgenic mouse model of multistage epithelial carcinogenesis in which the early region genes of the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) are expressed as transgenes under the control of the human keratin 14 (K14) promotor [58, 59], e.g., K14-HPV16 mice, we have reported that despite transgenic oncogene expression in the basal keratinocytes, absence of mast cells or inability to recruit innate immune cells to premalignant skin is sufficient to attenuate neoplastic progression [3, 104]. Other groups have described similar tumor-promoting roles for innate immune cells downstream of oncogene expression [60, 61]. As an example, secretion of the proinflammatory chemokine CXCL-8 by xenografted tumor cells is required for RasV12-dependent tumor-associated inflammation, onset of tumor vascularization and tumor growth [61]. Antibody-mediated depletion of granulocytes attenuated angiogenesis of RasV12-expressing tumors, suggesting that the ability of neoplastic cells to recruit inflammatory cells facilitates tumor outgrowth [61]. Several groups have reported that immature myeloid suppressor GR1+ CD11b+ cells accumulate in peripheral blood of cancer patients [62, 63] as well as in tumors and lymphoid organs of tumor-bearing animals [8, 64]. Myeloid suppressor cells were initially identified as cells that indirectly enhance tumorigenesis by suppressing tumor-specific adaptive immune responses [63–65]. It has recently been reported that myeloid suppressor cells can also directly promote tumor growth by contributing to angiogenesis at the tumor site [8]. Taken together, these studies support the concept that oncogene expression in “initiated” cells is not sufficient for full neoplastic progression; inflammation is required for “promotion” of neoplastic events downstream of oncogene expression (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Model of the potential role of the adaptive immune system in the enhancement of chronic inflammation-associated epithelial tumorigenesis. Antigens present in early neoplastic lesions are transported to lymphoid organs by dendritic cells and trigger adaptive immune responses. Subsequent dysregulated interactions between adaptive and innate immunity can result in excessive activation of the innate immune system, resulting in chronic inflammatory states in the neoplastic microenvironment. Activated innate immune cells promote tumor development via several mechanisms. Inflammatory cells are capable of modulating expression of genes within neoplastic cells, e.g., NF-κB, that regulate cell cycle and survival. Inflammatory cells regulate angiogenesis by the production of proangiogenic mediators, such as VEGF-A in neoplastic tissues. In addition, infiltrating inflammatory cells indirectly contribute to tumor development by the production of extracellular proteases, e.g., MMPs. MMPs regulate neoplastic progression by remodeling ECM components as well as non-ECM substrates such as cytokines, growth factors, cell–cell and cell-matrix adhesion molecules, and thus contribute to angiogenesis, inflammation and proliferation.

What are the downstream inflammatory cell-derived mediators that enhance carcinogenesis? Recently, two groups studying mouse models of inflammation-associated cancer have implicated activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), a proinflammatory transcription factor that regulates cell survival, proliferation and growth arrest, constitutes a link between inflammation and cancer [5, 7, 66]. Greten and colleagues [5] reported that specific deletion of IKKβ–a key intermediary of NF-κB–in myeloid cells decreased tumor growth in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer through reduced production of tumor-promoting paracrine factors [5]. Using a mouse model of inflammation-associated hepatocarcinogenesis, Pikarsky and colleagues [7] reported that inflammatory cells present in the neoplastic microenvironment control hepatocyte NF-κB activation via production of TNFα [7]. Thus, inflammatory cells are capable of modulating expression of genes within neoplastic cells that favor proliferation and survival by paracrine regulation of NF-κB.

Besides directly influencing proliferation and survival of neoplastic cells, tumor-infiltrating inflammatory cells also regulate tumorigenesis by contributing to angiogenesis, as experimental reduction in the extent of infiltration of inflammatory cells during neoplastic progression in mouse carcinogenesis models often correlates with attenuated angiogenesis and reduced tumor growth [3, 61, 104]. One mechanism by which inflammatory cells regulate angiogenesis is by means of the production of proangiogenic mediators, such as vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) in neoplastic tissues [67, 68]. In addition, a recent study reported that myeloid immune suppressor Gr+ CD11b+ cells have the potential to differentiate into endothelial cells and to directly incorporate into tumor endothelium in tumor-bearing animals [8].

Tumor-infiltrating inflammatory cells also indirectly contribute to tumor development by production of extracellular proteases [4, 6, 8, 69, 70]. MMPs represent a large family of proteolytic enzymes that play key roles in cancer progression [70, 71]. MMPs regulate tumor development by remodeling ECM components as well as non-ECM substrates such as cytokines, growth factors, cell–cell and cell-matrix adhesion molecules, and thus contribute to angiogenesis, inflammation and proliferation [70, 71]. Several mechanistic studies have reported that inflammatory cell-derived MMPs functionally contribute to neoplastic progression [4, 6, 8, 70]. For example, we previously reported that tumor incidence and growth in the K14-HPV16 mouse model of de novo epithelial carcinogenesis was reduced in the absence of MMP-9 [4]. Characteristics of neoplastic development were restored by the reconstitution of MMP-9-deficient/K14-HPV16 mice with wild-type bone marrow–derived cells, indicating that inflammatory cells functionally contribute to de novo carcinogenesis at least in part by their deposition of MMP-9 into the neoplastic microenvironment [4, 72]. These data indicate that ECM remodeling and/or increased bioavailability of growth factors that are normally sequestered within the ECM is regulated by inflammatory cells present in the tumor microenvironment, and thus inflammatory cells can create an environment permissive for tumor growth.

Although it is clear that chronic inflammation fosters tumor development, it is still largely unknown as to which mechanisms mediate initiation and sustainment of chronic inflammation associated with carcinogenesis. Understanding the pathways by which inflammatory cells are triggered to migrate and accumulate in (pre)malignant tissues might provide therapeutic opportunities for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Based on the striking similarities of tissue-damaging inflammatory events occurring during autoimmune- and other chronic inflammatory diseases, and inflammation-associated tumorigenesis, recent advances in understanding the underlying mechanisms of autoimmune disorders might aid in unraveling mechanisms of tumor-promoting chronic inflammation. Given the critical role of the adaptive immune system in recruitment and activation of innate immune cells during pathologic tissue remodeling, we hypothesized that similar pathways might be involved during inflammation-associated de novo carcinogenesis.

Link between adaptive and innate immunity potentiating cancer

Current dogma suggests that the adaptive immune system protects organisms from nascent tumors, a process referred to as immune surveillance [73, 74]. Immune surveillance protects individuals against certain pathogen-associated cancers, either by protecting against chronic pathogen infections or by preventing viral re-activation [75]. The importance of immune surveillance in protecting against viral-induced malignancy is underscored by the increased incidence of HPV16-related cervical and squamous carcinomas, Herpesvirus 8-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma and Epstein-Barr virus-related non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in immunocompromised patients [75–78]. The role of immune surveillance in protecting humans against non-viral-associated malignancies is less clear, and difficult to assess because of the shortened life spans of immune-compromised patients. Whereas the incidence of certain subsets of tumors, such as melanoma and lung carcinoma, appears to be increased [77, 79], the incidence of other common epithelial malignancies of nonviral origin does not appear to be higher in immune-compromised patients; it has even been reported that the incidence of various non-pathogen-related cancers in immune suppressed individuals is decreased [75, 80–82].

Several epidemiological studies have shown that patients with autoimmune disease, in particular, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, celiac disease and inflammation-induced pulmonary fibrosis, are predisposed to certain types of nonhematogenous malignancies, e.g., lung carcinoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer and cervical atypia [83–89], suggesting that an altered balance between innate and adaptive immunity might contribute to cancer development. However, these data may be confounded by long-term usage of NSAID in patients with autoimmune disease. For instance, several studies reported reduced incidence of colorectal cancer in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [87–91], consistent with reports showing that use of NSAID reduces the risk of colorectal cancer [55, 56].

Based on the observed importance of the adaptive immune system in initiating and/or maintaining the innate immune response during pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases [10–14], it would be anticipated that adaptive immunity may also play a promoting role in inflammation-associated cancer development. The earliest reports revealing a potential tumor-enhancing effect of adaptive immunity demonstrated that passive transfer of tumor-specific antibodies could enhance in vivo outgrowth of transplanted tumor cells or chemically induced tumors [92–94]. In addition, absence of B lymphocytes was reported to protect against transplanted and chemically induced tumors [95, 96]. Recently, availability of de novo carcinogenesis mouse models has allowed more accurate analysis of a possible tumor-enhancing role of the adaptive immune system. For example, active immunization of mice carrying a mutant ras oncogene resulted in the activation of humoral immune responses and enhanced papilloma formation upon chemical promotion [97, 98]; however, this study did not provide a mechanistic explanation. Studies by Barbera-Guillem and colleagues have reported that antitumor humoral immune responses potentiate in vivo growth and invasion of injected murine and human tumor cell lines via recruitment and activation of granulocytes and macrophages [67, 99]. Whether these observations are unique for tumor transplantation settings where premalignant progression is circumvented, or whether de novo carcinogenesis follows similar scenarios was not addressed.

To functionally assess whether the adaptive immune system exerts a regulatory role during de novo carcinogenesis, we intercrossed K14-HPV16 mice with Recombination-Activating Gene-1 homozygous null (RAG-1−/−) mice deficient for mature B and T lymphocytes and found that genetic deletion of adaptive immune cells resulted in failure to initiate and/or sustain leukocyte infiltration during premalignancy [104]. As a consequence, necessary parameters for full malignancy, e.g., chronic inflammation, tissue remodeling, angiogenesis and epithelial hyperproliferation were significantly reduced, culminating in attenuated premalignant progression to carcinoma [104]. Genetic elimination of CD4+ and/or CD8+ T lymphocytes did not affect chronic inflammation or alter characteristics of premalignant progression in K14-HPV16 mice. Since premalignant skin of K14-HPV16 mice is also characterized by abundant deposition of antibodies, we hypothesized that initiation of tumor-promoting chronic inflammation was mediated by a B cell-dependent process [104]. To address this, we adoptively transferred B lymphocytes or serum isolated from K14-HPV16 mice into K14-HPV16/RAG-1−/− mice and found that chronic inflammation in neoplastic skin as well as hallmarks of premalignant progression were restored [104]. Taken together, these data suggest that B lymphocytes play a crucial role in the onset of chronic inflammation associated with premalignant progression, thus potentiating neoplastic cascades downstream of oncogene expression (Fig. 2). However, B lymphocytes do not infiltrate premalignant skin in K14-HPV16 mice, instead, antibody deposits are found in dermal compartments of premalignant skin coinciding with infiltrating inflammatory cells [100, 104], suggesting that B lymphocytes exert their effect via production of antibodies that subsequently home to premalignant skin and activate resident inflammatory cells. As complement deficiency in K14-HVP16 mice did not affect chronic inflammation associated with premalignant skin or neoplastic progression [100], we anticipate that antibodies present in neoplastic skin trigger resident innate immune cells via cross-linking of FcRs resulting in rapid degranulation and release of pro-inflammatory mediators that further enhance the cascade of activation and recruitment of innate immune cells. Taken together, these data suggest that, whereas the adaptive immune system is indispensable for protection against viral-induced malignancies, it can instead potentiate development of chronic inflammation-associated malignancy. Therefore, inhibition of B lymphocyte activation and/or activation of innate immune cells may represent a viable approach to prevent and/or inhibit cancer development associated with chronic inflammation.

Clinical implications

Our data implicating B lymphocyte activation as one of the earliest critical events during premalignant progression downstream of oncogene expression [104] suggest that specific pharmacological interventions targeting B lymphocytes may represent viable cancer chemopreventative strategies. Approaches to target B lymphocytes have been developed and clinically validated in patients with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and other diseases presumed to be mediated by B lymphocytes [9]. Depletion of B lymphocytes using rituximab, a chimeric mouse/human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has been effectively applied in the clinic for the treatment of patients with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [101]. In addition, results from recent clinical trials indicate that depletion of B lymphocytes can be beneficial and well tolerated in patients with various autoimmune disorders [9, 41–44]. We hypothesize that B lymphocyte depletion may also be a viable approach to prevent progression of inflammation-associated premalignant lesions to malignant states. The first step in accomplishing this will be to determine which human malignancies develop in a B lymphocyte–dependent manner. Since inhibition of immediate downstream effects of B cell activation might be accompanied by fewer adverse side effects than the deletion of the complete B cell repertoire; elucidation of these pathways may provide important therapeutic targets. For example, chronic antibody-mediated destruction of platelets in patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura occurs in an FcR-dependent manner, and experimental clinical studies indicate that not only B lymphocyte depletion [42], but also treatment with FcR blocking antibodies could have therapeutic beneficial effects [102]. Taken together, knowledge concerning new therapeutic modalities obtained from experimental and clinical studies in the context of autoimmune disease might help to develop combinatorial pharmacological intervention strategies targeting malignancy-promoting chronic inflammation in patients predisposed to cancer development.

Numerous studies reporting a tumor-enhancing effect of humoral immunity [67, 92–94, 97–99] and our data implicating B lymphocytes as enhancers of premalignant progression by promoting chronic inflammation in the neoplastic microenvironment suggest that passive transfer antibody therapies and active immunotherapeutical approaches in patients predisposed to malignancy may actually enhance neoplastic risk. It is important to realize that antibody-based therapy has demonstrated efficacy in cancer patients with solid tumors and hematapoietic malignancies [103]; however, it may have disparate outcomes when antibody responses are induced in patients with premalignant disease or in cancer-predisposed patients, thus, emphasizing the importance for understanding the role that B lymphocytes and humoral immunity play during human carcinogenesis.

Conclusions

Despite compelling data indicating a functional link between inflammation and cancer, pathways regulating initiation and maintenance of chronic inflammation during cancer development remain poorly described. Increased understanding of the mechanisms underlying initiation of tumor-promoting chronic inflammation will further the development of approaches designed to block critical early events during neoplastic progression downstream of oncogene expression. Recent mechanistic studies of inflammatory autoimmune disorders have revealed that dysregulated interactions between adaptive and innate immunity can result in excessive activation of the immune system, resulting in chronic inflammatory states, culminating in tissue damage. We are now beginning to understand that aberrant interactions between adaptive immunity, and in particular, B lymphocytes with innate immunity may also be critically involved during the early stages of neoplastic progression. The use of recently developed, effective, well-tolerated clinical approaches to deplete B lymphocytes and inhibition of pathways downstream of B lymphocyte activation might, therefore, not only be applicable to the treatment of patients with autoimmune disorders, but also to the treatment of patients with premalignant disease.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Drs. Alexandra Eichten and Stephen Robinson for valuable suggestions. KEdV is a fellow of the Dutch Cancer Society. LMC is supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases, Department of Army, Breast Cancer Center of Excellence and National Institutes of Health, Center for Proteolytic Pathways.

Footnotes

This article is a symposium paper from the conference “Tumor Escape and its Determinants”, held in Salzburg, Austria, on 10–13 October 2004

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coussens LM, Raymond WW, Bergers G, Laig-Webster M, Behrendtsen O, Werb Z, Caughey GH, Hanahan D. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1382. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coussens LM, Tinkle CL, Hanahan D, Werb Z. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 2000;103:481. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiratsuka S, Nakamura K, Iwai S, Murakami M, Itoh T, Kijima H, Shipley JM, Senior RM, Shibuya M. MMP9 induction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 is involved in lung-specific metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:289. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(02)00153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, Kasem S, Gutkovich-Pyest E, Urieli-Shoval S, Galun E, Ben-Neriah Y. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, Debusk LM, Fukuda K, Fingleton B, Green-Jarvis B, Shyr Y, Matrisian LM, Carbone DP, Lin PC. Expansion of myeloid immune suppressor Gr+CD11b+ cells in tumor-bearing host directly promotes tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:409. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorman C, Leandro M, Isenberg D. B cell depletion in autoimmune disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(Suppl 4):S17. doi: 10.1186/ar1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji H, Ohmura K, Mahmood U, Lee DM, Hofhuis FM, Boackle SA, Takahashi K, Holers VM, Walport M, Gerard C, Ezekowitz A, Carroll MC, Brenner M, Weissleder R, Verbeek JS, Duchatelle V, Degott C, Benoist C, Mathis D. Arthritis critically dependent on innate immune system players. Immunity. 2002;16:157. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korganow AS, Ji H, Mangialaio S, Duchatelle V, Pelanda R, Martin T, Degott C, Kikutani H, Rajewsky K, Pasquali JL, Benoist C, Mathis D. From systemic T cell self-reactivity to organ-specific autoimmune disease via immunoglobulins. Immunity. 1999;10:451. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80045-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Z, Diaz LA, Troy JL, Taylor AF, Emery DJ, Fairley JA, Giudice GJ. A passive transfer model of the organ-specific autoimmune disease, bullous pemphigoid, using antibodies generated against the hemidesmosomal antigen, BP180. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2480. doi: 10.1172/JCI116856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto I, Staub A, Benoist C, Mathis D. Arthritis provoked by linked T and B cell recognition of a glycolytic enzyme. Science. 1999;286:1732. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trouw LA, Groeneveld TW, Seelen MA, Duijs JM, Bajema IM, Prins FA, Kishore U, Salant DJ, Verbeek JS, van Kooten C, Daha MR. Anti-C1q autoantibodies deposit in glomeruli but are only pathogenic in combination with glomerular C1q-containing immune complexes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:679. doi: 10.1172/JCI200421075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sahu A, Lambris JD. Structure and biology of complement protein C3, a connecting link between innate and acquired immunity. Immunol Rev. 2001;180:35. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2001.1800103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walport MJ. Complement. First of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1058. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walport MJ. Complement. Second of two parts. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1140. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belardelli F, Ferrantini M. Cytokines as a link between innate and adaptive antitumor immunity. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:201. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carroll MC. The complement system in regulation of adaptive immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:981. doi: 10.1038/ni1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire. Nature. 1999;402:255. doi: 10.1038/46218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonegawa S. Somatic generation of antibody diversity. Nature. 1983;302:575. doi: 10.1038/302575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McHeyzer-Williams MG. B cells as effectors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:354. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(03)00046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janeway CA, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M. Immunobiology. New York: Garland; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprent J, Surh CD. T cell memory. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:551. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100101.151926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dranoff G. Cytokines in cancer pathogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:11. doi: 10.1038/nrc1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granucci F, Zanoni I, Feau S, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Dendritic cell regulation of immune responses: a new role for interleukin 2 at the intersection of innate and adaptive immunity. Embo J. 2003;22:2546. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ottenhoff TH, Kumararatne D, Casanova JL. Novel human immunodeficiencies reveal the essential role of type-I cytokines in immunity to intracellular bacteria. Immunol Today. 1998;19:491. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(98)01321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427:154. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foti M, Granucci F, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. A central role for tissue-resident dendritic cells in innate responses. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:650. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroczek RA, Mages HW, Hutloff A. Emerging paradigms of T-cell co-stimulation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:321. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alahlafi AM, Wordsworth P, Wojnarowska F. The lupus band: do the autoantibodies target collagen VII. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:504. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wipke BT, Wang Z, Nagengast W, Reichert DE, Allen PM. Staging the initiation of autoantibody-induced arthritis: a critical role for immune complexes. J Immunol. 2004;172:7694. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humbles AA, Lu B, Nilsson CA, Lilly C, Israel E, Fujiwara Y, Gerard NP, Gerard C. A role for the C3a anaphylatoxin receptor in the effector phase of asthma. Nature. 2000;406:998. doi: 10.1038/35023175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z, Giudice GJ, Swartz SJ, Fairley JA, Till GO, Troy JL, Diaz LA. The role of complement in experimental bullous pemphigoid. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1539. doi: 10.1172/JCI117826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogarth PM. Fc receptors are major mediators of antibody based inflammation in autoimmunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:798. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(02)00409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sylvestre DL, Ravetch JV. A dominant role for mast cell Fc receptors in the Arthus reaction. Immunity. 1996;5:387. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80264-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe N, Akikusa B, Park SY, Ohno H, Fossati L, Vecchietti G, Gessner JE, Schmidt RE, Verbeek JS, Ryffel B, Iwamoto I, Izui S, Saito T. Mast cells induce autoantibody-mediated vasculitis syndrome through tumor necrosis factor production upon triggering Fcgamma receptors. Blood. 1999;94:3855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clynes R, Dumitru C, Ravetch JV. Uncoupling of immune complex formation and kidney damage in autoimmune glomerulonephritis. Science. 1998;279:1052. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards JC, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J, Filipowicz-Sosnowska A, Emery P, Close DR, Stevens RM, Shaw T. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stasi R, Pagano A, Stipa E, Amadori S. Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment for adults with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2001;98:952. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.4.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quartier P, Brethon B, Philippet P, Landman-Parker J, Le Deist F, Fischer A. Treatment of childhood autoimmune haemolytic anaemia with rituximab. Lancet. 2001;358:1511. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Looney RJ, Anolik JH, Campbell D, Felgar RE, Young F, Arend LJ, Sloand JA, Rosenblatt J, Sanz I. B cell depletion as a novel treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase I/II dose-escalation trial of rituximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2580. doi: 10.1002/art.20430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Funada Y, Noguchi T, Kikuchi R, Takeno S, Uchida Y, Gabbert HE. Prognostic significance of CD8+ T cell and macrophage peritumoral infiltration in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakakubo Y, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, Hida Y, Oshikiri T, Suzuoki M, Hiraoka K, Itoh T, Kondo S, Katoh H. Clinical significance of immune cell infiltration within gallbladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1736. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oshikiri T, Miyamoto M, Shichinohe T, Suzuoki M, Hiraoka K, Nakakubo Y, Shinohara T, Itoh T, Kondo S, Katoh H. Prognostic value of intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocyte in extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma as essential immune response. J Surg Oncol. 2003;84:224. doi: 10.1002/jso.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wakabayashi O, Yamazaki K, Oizumi S, Hommura F, Kinoshita I, Ogura S, Dosaka-Akita H, Nishimura M. CD4(+) T cells in cancer stroma, not CD8(+) T cells in cancer cell nests, are associated with favorable prognosis in human non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01392.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benitez-Bribiesca L, Wong A, Utrera D, Castellanos E. The role of mast cell tryptase in neoangiogenesis of premalignant and malignant lesions of the uterine cervix. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:1061. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bingle L, Brown NJ, Lewis CE. The role of tumour-associated macrophages in tumour progression: implications for new anticancer therapies. J Pathol. 2002;196:254. doi: 10.1002/path.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imada A, Shijubo N, Kojima H, Abe S. Mast cells correlate with angiogenesis and poor outcome in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:1087. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.01517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin EY, Pollard JW. Macrophages: modulators of breast cancer progression. Novartis Found Symp. 2004;256:158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takanami I, Takeuchi K, Naruke M. Mast cell density is associated with angiogenesis and poor prognosis in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:2686. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000615)88:12<2686::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shacter E, Weitzman SA. Chronic inflammation and cancer. Oncology. 2002;16:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clevers H. At the crossroads of inflammation and cancer. Cell. 2004;118:671. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turini ME, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2: a therapeutic target. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow. Lancet. 2001;357:539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arbeit JM, Munger K, Howley PM, Hanahan D. Progressive squamous epithelial neoplasia in K14-human papillomavirus type 16 transgenic mice. J Virol. 1994;68:4358. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4358-4368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coussens LM, Hanahan D, Arbeit JM. Genetic predisposition and parameters of malignant progression in K14- HPV16 transgenic mice. Am J Path. 1996;149:1899. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sparmann A, Bar-Sagi D. Ras-induced interleukin-8 expression plays a critical role in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:447. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166:678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Serafini P, De Santo C, Marigo I, Cingarlini S, Dolcetti L, Gallina G, Zanovello P, Bronte V. Derangement of immune responses by myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:64. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Immature myeloid cells and cancer-associated immune suppression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:293. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gabrilovich DI, Velders MP, Sotomayor EM, Kast WM. Mechanism of immune dysfunction in cancer mediated by immature Gr-1+ myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Balkwill F, Coussens LM. Cancer: an inflammatory link. Nature. 2004;431:405. doi: 10.1038/431405a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barbera-Guillem E, Nyhus JK, Wolford CC, Friece CR, Sampsel JW. Vascular endothelial growth factor secretion by tumor-infiltrating macrophages essentially supports tumor angiogenesis, and IgG immune complexes potentiate the process. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Esposito I, Menicagli M, Funel N, Bergmann F, Boggi U, Mosca F, Bevilacqua G, Campani D. Inflammatory cells contribute to the generation of an angiogenic phenotype in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:630. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.014498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, Vu TH, Itoh T, Tamaki K, Tanzawa K, Thorpe P, Itohara S, Werb Z, Hanahan D. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.de Visser KE, Coussens LM (2004) Inflammation and matrix metalloproteinases: implications for cancer development. In: Morgan DW, Forssmann UJ, Nakada MT (eds) Cancer and inflammation. Birkhauser, Basel, p 71

- 71.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:161. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Kempen LCL, Rhee JS, Dehne K, Lee J, Edwards DR, Coussens LM. Epithelial carcinogenesis: dynamic interplay between neoplastic cells and their microenvironment. Differentiation. 2002;70:501. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21:137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pardoll DM. Does the immune system see tumors as foreign or self. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:807. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boshoff C, Weiss R. AIDS-related malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:373. doi: 10.1038/nrc797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Birkeland SA, Storm HH, Lamm LU, Barlow L, Blohme I, Forsberg B, Eklund B, Fjeldborg O, Friedberg M, Frodin L, et al. Cancer risk after renal transplantation in the Nordic countries, 1964–1986. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:183. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Penn I. Posttransplant malignancies. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:1260. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(98)01987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pham SM, Kormos RL, Landreneau RJ, Kawai A, Gonzalez-Cancel I, Hardesty RL, Hattler BG, Griffith BP. Solid tumors after heart transplantation: lethality of lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1623. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fung JJ, Jain A, Kwak EJ, Kusne S, Dvorchik I, Eghtesad B. De novo malignancies after liver transplantation: a major cause of late death. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:S109. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gallagher B, Wang Z, Schymura MJ, Kahn A, Fordyce EJ. Cancer incidence in New York State acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:544. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stewart T, Tsai SC, Grayson H, Henderson R, Opelz G. Incidence of de-novo breast cancer in women chronically immunosuppressed after organ transplantation. Lancet. 1995;346:796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alaedini A, Green PH. Narrative review: celiac disease: understanding a complex autoimmune disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:289. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-4-200502150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nived O, Bengtsson A, Jonsen A, Sturfelt G, Olsson H. Malignancies during follow-up in an epidemiologically defined systemic lupus erythematosus inception cohort in southern Sweden. Lupus. 2001;10:500. doi: 10.1191/096120301678416079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Blumenfeld Z, Lorber M, Yoffe N, Scharf Y. Systemic lupus erythematosus: predisposition for uterine cervical dysplasia. Lupus. 1994;3:59. doi: 10.1177/096120339400300112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Artinian V, Kvale PA. Cancer and interstitial lung disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:425. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200409000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mellemkjaer L, Linet MS, Gridley G, Frisch M, Moller H, Olsen JH. Rheumatoid arthritis and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32:1753. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Thomas E, Brewster DH, Black RJ, Macfarlane GJ. Risk of malignancy among patients with rheumatic conditions. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:497. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001101)88:3<497::AID-IJC27>3.3.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomas E, Symmons DP, Brewster DH, Black RJ, Macfarlane GJ. National study of cause-specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile chronic arthritis, and other rheumatic conditions: a 20 year followup study. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cibere J, Sibley J, Haga M. Rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of malignancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1580. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gridley G, McLaughlin JK, Ekbom A, Klareskog L, Adami HO, Hacker DG, Hoover R, Fraumeni JF., Jr Incidence of cancer among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:307. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Agassy-Cahalon L, Yaakubowicz M, Witz IP, Smorodinsky NI. The immune system during the precancer period: naturally-occurring tumor reactive monoclonal antibodies and urethane carcinogenesis. Immunol Lett. 1988;18:181. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(88)90017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kaliss N. Immunological enhancement of tumor homografts in mice: a review. Cancer Res. 1958;18:992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Snell GD. Incompatibility reactions to tumor homotransplants with particular reference to the role of the tumor; a review. Cancer Res. 1957;17:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brodt P, Gordon J. Natural resistance mechanisms may play a role in protection against chemical carcinogenesis. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1982;13:125. doi: 10.1007/BF00205312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Monach PA, Schreiber H, Rowley DA. CD4+ and B lymphocytes in transplantation immunity. II. Augmented rejection of tumor allografts by mice lacking B cells. Transplantation. 1993;55:1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Schreiber H, Wu TH, Nachman J, Rowley DA. Immunological enhancement of primary tumor development and its prevention. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:351. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Siegel CT, Schreiber K, Meredith SC, Beck-Engeser GB, Lancki DW, Lazarski CA, Fu YX, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. Enhanced growth of primary tumors in cancer-prone mice after immunization against the mutant region of an inherited oncoprotein. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1945. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barbera-Guillem E, May KF, Jr, Nyhus JK, Nelson MB. Promotion of tumor invasion by cooperation of granulocytes and macrophages activated by anti-tumor antibodies. Neoplasia. 1999;1:453. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. Early neoplastic progression is complement independent. Neoplasia. 2004;6:768. doi: 10.1593/neo.04250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.McLaughlin P, White CA, Grillo-Lopez AJ, Maloney DG. Clinical status and optimal use of rituximab for B-cell lymphomas. Oncology (Huntingt) 1998;12:1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bussel JB. Fc receptor blockade and immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Hematol. 2000;37:261. doi: 10.1053/shem.2000.8957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.von Mehren M, Adams GP, Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy for cancer. Annu Rev Med. 2003;54:343. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM (2005) De novo carcinogenesis promoted by chronic inflammation is B lymphocyte-dependent. Cancer Cell in press [DOI] [PubMed]