Abstract

Functional inactivation of genes critical to immunity may occur by mutation and/or by repression, the latter being potentially reversible with agents that modify chromatin. This study was constructed to determine whether reversal of gene silencing, by altering the acetylation status of chromatin, might lead to an effective tumor vaccine. We show that the expression of selected genes important to tumor immunity, including MHC class II, CD40, and B7-1/2 are altered by treating tumor cells in vitro with a histone deacetylase inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA). Tumor cells treated in vitro with TSA showed delayed onset and rate of tumor growth in 70% of the J558 plasmacytoma and 100% of the B16 melanoma injected animals. Long-term tumor specific immunity was elicited to rechallenge with wild-type cells in approximately 30% in both tumor models. Splenic T cells from immune mice lysed untreated tumor cells, and SCID mice did not manifest immunity, suggesting that T cells may be involved in immunity. We hypothesize that repression of immune genes is involved in the evasion of immunity by tumors and suggest that epigenetically altered cancer cells should be further explored as a strategy for the induction of tumor immunity.

Keywords: Costimulation, Gene regulation, MHC, Tumor immunity, Vaccine

Introduction

Tumor cells often manifest abnormalities in the expression of genes that are critical to the immune response and the “escape” variants have a selective advantage that allows them, over time, to become a major population in the tumor. Escape can occur at the level of antigen presentation and initiation of the immune response, or later at the effector stage. Defects in tumor cells may arise from mutations in specific immune genes, which have been associated with tumor evasion [5]. Although several immune genes are known to be silenced by chromatin [9, 20] there is, as yet, little definitive evidence that epigenetic mechanisms are directly responsible for immune escape. The experiments outlined in this report address this issue. It also seems likely that tumor cells with mutations may accumulate additional epigenetic regulatory defects and develop complex patterns of immune gene expression, some of which are potentially reversible. Several covalent modifications of histone proteins (acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and ADP ribosylation) are responsible for a “histone code” that epigenetically regulates gene expression patterns. Acetylation of histones has been extensively studied and complexes containing histone deacetylases (HDACs) have been found to contribute to gene repression, both globally and by targeting specific genes [11]. Agents, such as trichostain A (TSA), which inhibit HDACs promote the acetylation of histones and are generally associated with enhanced transcription, although exceptions are not infrequent [2].

Plasma cell tumors do not transcribe MHC class II transactivator (CIITA), the “master” regulator of class II, and this is associated with a putative repressor of CIITA [19]. Recent studies suggest that Blimp-1, a zinc-finger DNA-binding protein, recruits a corepressor complex, which may contain HDACs, to the CIITA promoter and this may be responsible for the failure of the tumors to express class II [13, 25]. Since deacetylase inhibitors up-regulate class II on tumors that are constitutively negative for these antigens [9], we considered the possibility that tumor cells might become antigen-presenting cells (APCs) after TSA treatment. Although the role of tumor cells as APCs has been controversial, evidence for direct presentation in the MHC class II pathway has been reported for class II–negative tumor cells transfected with class II and B7-1 [14] and the tumor cells may present novel antigenic epitopes not presented by host APCs [15]. Therefore, with appropriate costimulation, class II on tumor cells may directly activate naïve CD4+ T cells, which play an important role in the antitumor response [6, 12, 21, 24]. We demonstrate here that MHC class II and costimulatory molecules, CD40 and B7-1/2, can be induced on a plasma cell tumor by TSA and that expression is dose dependent. The J558 plasmacytoma epigenetically altered in vitro showed reduced tumorigenicity and, importantly, elicited cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and immunity to rechallenge with untreated tumor cells. Similar data showing long-term immunity following vaccination with TSA-treated B16 melanoma cells is presented. Although the detailed mechanisms responsible for the generation of immunity are yet to be defined, it is clear that altering the status of chromatin acetylation of tumor cells is effective in reducing tumorigenicity and eliciting immunogenicity in both of these tumor models.

Materials and methods

Cells, mice, and reagents

Mouse plasmacytoma J558, melanoma B16 (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), mammary carcinoma 4T1 (Suzanne Ostrand-Rosenberg, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, USA), and plasmacytoma–B cell hybridoma 1H6T3 (Ray Kelleher, Roswell Park Cancer Institute [RPCI], Buffalo, NY, USA) cells were maintained in culture as specified. C57BL/6, BALB/c, and C.B.17-SCID mice, 6- to 8-weeks old, were purchased and maintained in the Department of Laboratory Animal Resources at RPCI. Principles of laboratory animal care (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1986) were followed, and all work was carried out under RPCI IACUC approval. Stock and working dilutions of TSA (Wako Biochemical, Richmond, VA, USA) were prepared in ethanol. l-Phenylalanine mustard (LPAM) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in ethanol with 10% hydrochloric acid.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was conducted by published methods [23] on a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). R-Phycoerythrin-conjugated antimouse I-Ad, CD40, CD80, CD86 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) mAbs were used in these experiments. Annexin V–FITC (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) staining allowed quantitation of annexin V–positive (an+) apoptotic and annexin V–negative (an−) nonapoptotic cell populations. Since apoptotic cells are known to have higher nonspecific antibody binding than viable cells, isotype controls matched to each mAb were used with each treatment to correct for staining variability between antibodies of different isotype. Forward scatter versus side scatter gating was set to include all nonaggregated cells but to exclude any apoptotic fragments. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Tumorigenesis assay

Treated or untreated J558 (4×106 live cells) suspended in 100 μl of PBS, were injected s.c. in the ventrolateral aspect of the trunk of the syngeneic mouse (5–10 mice/group). Cells were treated for 24 h in culture media and subsequently washed twice with PBS before injection. This tumor-challenge dose is 400-fold higher than the minimum number of cells required to generate tumor in 100% of mice. Preparations of treated cells were studied by flow cytometry, for the expression of MHC and costimulatory molecules as well as levels of apoptosis prior to use to ensure consistency between experiments. Tumors were measured every 3 days, and mice were euthanized when tumor diameter reached 2 cm. After 60 days, tumor-free animals were rechallenged s.c. in the opposite side of the trunk with 4×106 untreated J558 and observed for another 60 days. Immune mice (after rechallenge) were used to determine specificity by injecting either 1H6T3 (1×106) cells s.c. in the ventrolateral aspect of the trunk or 4T1 (1×105) cells into the mammary fat pad of the female mice. For B16 tumorigenesis, 1×105 treated or untreated live cells were injected s.c. in the ventrolateral aspect of the trunk of syngeneic mice. After 40 days, tumor-free mice were rechallenged s.c. on the opposite side with 1×105 untreated B16 and observed for another 60 days.

Cytotoxicity assay

Tumor-free mice, 40 days after immunization with 25-nM TSA-treated J558, were challenged with untreated J558. Spleens isolated from groups of three immune (15 days after rechallenge) or normal mice were disrupted, and the suspension was purified over nylon wool. To obtain effector CTLs, purified splenic T cells (5×105) were cultured with TSA-treated and irradiated (40 Gy) J558 cells (2.5×105) in RPMI 1640 w/10% FBS, 1 mM 2-ME and 10 U/ml of IL-2 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). After 4 days, viable T cells were isolated from the cultures using Ficoll-Paque centrifugation, and the level of anti-J558 cytotoxicity exhibited in vitro was determined utilizing a standard 4.5-h 51Cr-release assay [4].

Results

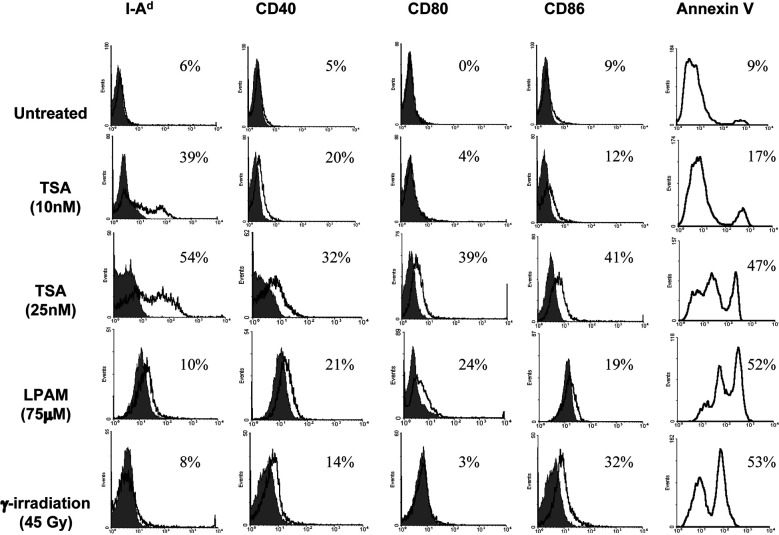

The J558 plasmacytoma was selected for study since this is a well-established murine tumor model in which several mechanisms of tumor escape have been proposed [26]. J558 cells were treated with different concentrations of TSA (5–100 nM) for 24 h and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. Figure 1 shows the percentage of positive cells after various treatments and demonstrates that a low concentration of TSA (10 nM) with ~10% an+ cells elicited MHC class II expression but low levels of CD40 and no B7-1/2. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that at this concentration histones in MHC class II locus were acetylated (data not shown). Treatment of J558 with 25 nM TSA, a condition that produced ~50% an+ cells, further enhanced MHC class II expression with significant levels of CD40, B7-1 and B7-2 antigens (30–40%, see Fig. 1) on the cell surface. A high concentration of TSA (75 nM and above) induced low levels of both MHC class II and costimulatory molecules and resulted in ~90% an+ cells (data not shown). Since TSA induces a concentration-dependent apoptotic response, which could be important in antitumor immunity, we compared the gene expression patterns produced by TSA with two other apoptosis-inducing agents (LPAM and γ-irradiation). We first titrated J558 cells with each of these agents over a wide range of doses measuring viability by trypan blue exclusion and apoptosis by annexin V staining (data not shown). The doses of LPAM (75 μM) and γ-irradiation (45 Gy), shown in Fig. 1, were selected since they produced ~50% an+ cells 24 h after treatment which is similar to 25 nM TSA which gave maximum levels of MHC class II. LPAM elicited CD40 and B7-1/2 but no class II. γ-Irradiation elicited low levels of B7-2 and CD40 but no B7-1 or class II.

Fig. 1.

Expression of MHC class II, CD40, and B7-1/2 on J558 after treatment with TSA, LPAM, or γ-irradiation. J558 cells were stained with PE–anti-I-Ad, CD40, CD80, CD86 mAb, specific isotype controls, and annexin V–FITC, after treatment with TSA (10 nM and 25 nM for 24 h), LPAM (75 μM for 24 h) or γ-irradiation (45 Gy followed by 24-h culture). Flow cytometric analyses were performed to assay expression of the indicated surface markers. Isotype controls are shown as shaded peaks, and heavy lines represent expression determined by specific antibody staining. The gated cell population includes both apoptotic and viable cells. Each histogram presents events on the linear y-axis and FL2 fluorescence intensity on the logarithmic x-axis, except for the annexin V plots, which present FL1. Values indicated in the histogram are the percentage of cells positive for the respective mAb

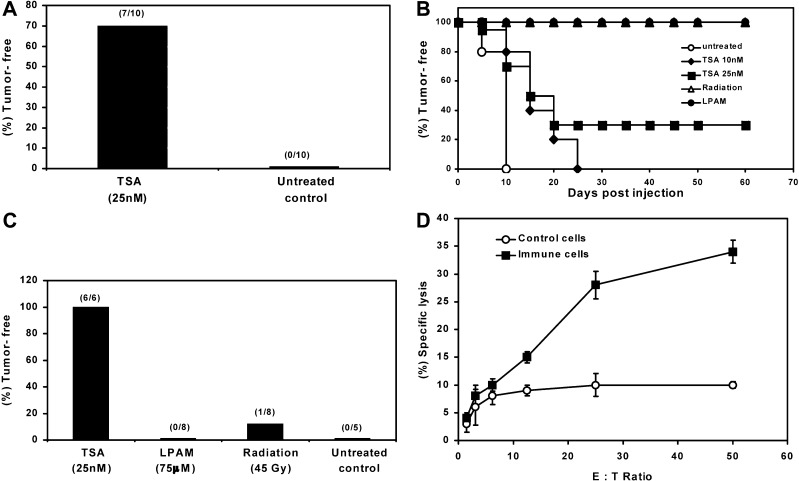

To determine whether TSA-treated tumor cells show altered tumorigenicity, we inoculated groups of syngeneic mice with untreated cells or J558 cells treated with several concentrations of TSA (5–75 nM for 24 h). As shown in Table 1, nearly all (98% of 62) control mice developed tumors after s.c. injection of 4×106 cells. TSA treatment at a dose of 5 nM had no effect on class II or costimulatory molecule expression and 100% of the mice developed tumors. If J558 cells were treated with 10 nM TSA, conditions that resulted in moderate levels of MHC class II and low CD40 but no detectable B7-1/2 expression, the tumor incidence and growth rate were indistinguishable from controls. However, as shown in Fig. 2A, 70% of mice injected with 25 nM TSA-treated J558 cells were tumor-free after 10 days by which time 100% of controls had developed tumors and, as illustrated in Fig. 2B, 30% of the mice showed lasting (~2 months) immunity. To compare TSA with other apoptosis-inducing agents, we used LPAM (75 μM) or γ-irradiation (45 Gy) treated J558 cells containing approximately 50% apoptotic cells and observed tumor growth. Figure 2B demonstrates that tumorigenesis with J558 cells treated with LPAM or γ-irradiation is totally inhibited.

Table 1.

Tumorigenesis of J558 plasmacytoma after treatment with TSA, LPAM, or γ-irradiation. J558 cells (4×106), untreated or treated with different concentrations of TSA (for 24 h), LPAM (75 μM for 24 h) or γ-irradiation (45 Gy followed by 24 h culture), were inoculated in syngeneic mice.The total number of mice used per treatment group is shown in parentheses

| Treatment | Number of mice developed tumor (total mice) | Tumor-free mice after 60 days, percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 61 (62) | <2 |

| 5 nM TSA | 5 (5) | 0 |

| 10 nM TSA | 10 (10) | 0 |

| 25 nM TSA | 26 (35) | 26 |

| 75 μM LPAM | 0 (8) | 100 |

| 45 Gy | 0 (10) | 100 |

Fig. 2A–D.

Reduced tumorigenicity and durable immunity generation by J558 cells treated with TSA. A Tumor-free survival at day 10 after s.c. inoculation of TSA (25 nM) treated or untreated J558 cells. The number of tumor-free mice compared with total numbers used in each treatment group is shown in parentheses. B Kaplan-Meier plot of syngeneic mice (10 mice/group) vaccinated with TSA-treated (10 nM and 25 nM for 24 h), LPAM-treated (75 μM for 24 h), or γ-irradiated (45 Gy followed by 24 h culture) J558 cells and observed for 60 days to record tumor-free survival. C Tumor-free mice, after vaccination with J558 cells treated with TSA, LPAM, or γ-irradiation, were rechallenged with untreated J558 cells s.c. in the opposite side of the trunk and observed subsequently for another 60 days. Data are percentages of tumor-free mice after tumor challenge. D Antitumor CTL response elicited by splenic T cells of TSA-treated J558 immune mice. Splenic T cells isolated from immune or naïve mice were stimulated in vitro with irradiated J558 and analyzed in triplicate for cytotoxic activity using 51Cr-labeled untreated J558 as target. Data are representative of three independent experiments

The above data raise the issue of whether the treatment employed altered tumor cells so that they became capable of antigen presentation thereby generating lasting immunity to the wild-type tumors. To determine the level of immunity generation, we rechallenged all the tumor-free mice after 60 days with untreated J558. The data in Fig. 2C demonstrate that the level of durable immunity generated by J558 treated with LPAM or γ-irradiation was poor (0–12% tumor-free) in comparison to mice vaccinated with 25-nM TSA-treated J558 (100% tumor-free). In similar experiments, J558 cells treated with a high TSA dose (75 nM for 24 h), containing ~90% an+ cells, demonstrated 50% tumor-free mice after vaccination and immunity in 50% mice after rechallenge (data not shown). These results suggest that tumorigenesis and the generation of immunity by preparations containing similar numbers of apoptotic cells may vary depending on the apoptosis-inducing agent.

As an indication of whether immunity played a role in the rejection of TSA-treated tumors, we injected untreated or TSA (25 nM) treated J558 cells s.c. into SCID mice and monitored tumorigenesis. All mice challenged with TSA-treated (13 mice) or untreated cells (9 mice) developed tumors, and tumor growth rates were very similar in SCID and immunocompetent mice. This suggests that T and/or B cells are involved in tumor immunity and that NK cells by themselves are not effective in rejecting J558 tumors.

To determine whether CTLs were elicited in immune mice, we isolated splenic T cells from control and TSA-treated J558-vaccinated mice that remained tumor-free after rechallenge and assessed their ability to lyse untreated J558 cells. As shown in Fig. 2D, T cells derived from immune mice displayed substantial anti-J558 lytic activity compared with T cells derived from normal mice. This assay has been repeated three times with T cells derived from immune mice showing an average of 33% killing, while control T cells showed an average of 4% killing at E/T ratio 50:1. Thus, as a consequence of TSA-treated J558 tumor inoculation, T-cell–enriched preparations with anti-J558 cytotoxicity toward untreated J558 targets can be cultured from the spleens of immune mice.

The cytotoxicity studies, together with the altered tumorigenicity and enhanced immunogenicity after TSA-treated tumor cell vaccination, suggest that the epigenetically altered J558 cells elicit tumor immunity. This thesis is further strengthened by the finding that 100% of J558-immune mice developed tumors when rechallenged with either of two unrelated syngeneic (H-2d) tumors, 1H6T3 or 4T1 (data not shown). Thus, immunity appears to be tumor specific.

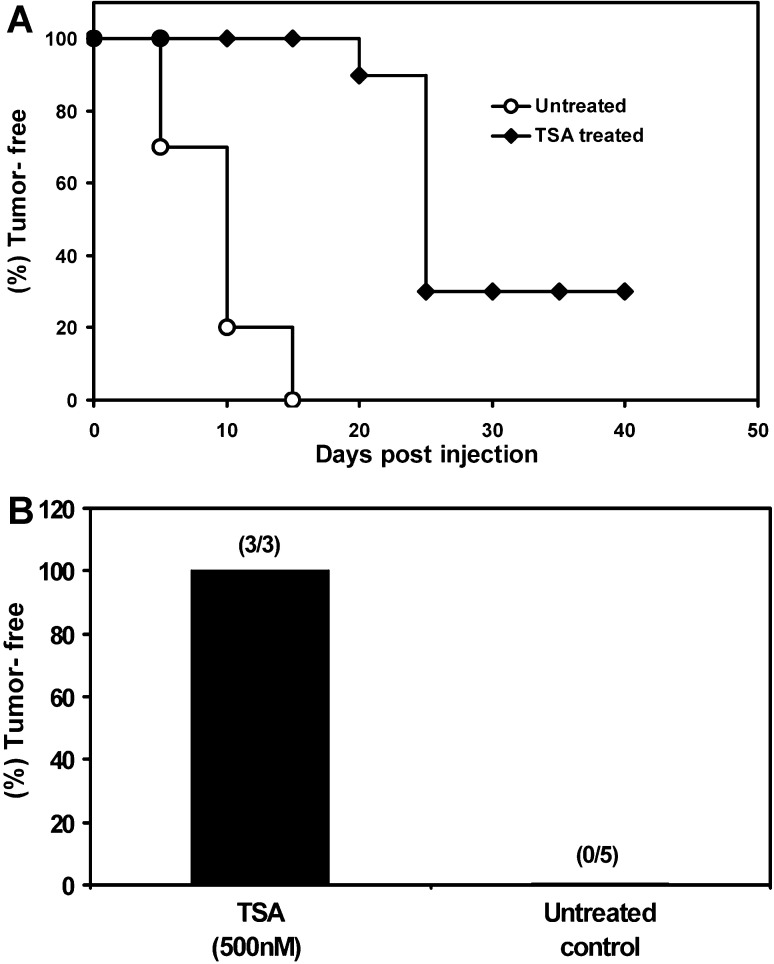

To extend this approach to another tumor, we vaccinated a group of 10 syngeneic mice with TSA-treated nonimmunogenic B16 melanoma cells (H-2b haplotype) and determined tumorigenicity and immunity generation. As shown in Fig. 3A, 100% of mice injected with 500 nM TSA-treated (24 h) J558 cells were tumor-free after 15 days by which time all of the controls had developed tumors and 30% of the mice showed lasting immunity. When tumor-free mice were rechallenged with wild-type B16, as shown in Fig. 3B, all the TSA-treated B16-vaccinated mice (3 out of 3) remained tumor-free over 60 days. These data suggest that the epigenetically altered tumor cell vaccination strategy may be applicable to different malignant tumors.

Fig. 3A,B.

Epigenetically altered B16 melanoma cells generate immunity. A Kaplan-Meier plot of syngeneic mice (10 mice/group) inoculated s.c. with TSA-treated (500 nM for 24 h) or untreated B16 cells in the ventrolateral aspect of the trunk and observed for 40 days to record tumor-free survival. B Tumor-free mice, after vaccination with TSA-treated B16, were rechallenged with untreated B16 in the opposite side of the trunk and observed for another 60 days. The number of tumor-free mice compared with total numbers used in each group is shown in parentheses

Discussion

A straightforward explanation of the immunity shown here to be generated by TSA-treated cells is that they acquire the display of immune molecules necessary to become effective APCs. In our studies, the association of immunity with enhanced class II and costimulatory molecule expression and the presentation of antigen and class II peptides by TSA-treated J558 cells (Chou S-D et al., manuscript submitted) is consistent with direct class II presentation which has been suggested in other tumor models [14, 15]. Since histone deacetylase inhibitors affect the expression of many genes, our studies must be considered correlative, and direct presentation in vivo was not demonstrated. However, in the J558 model, tumor rejection has been reported to be dependent upon expression of B7 on J558 cells and the elicitation of CD8+ CTLs in the tumor bed [16]. These conclusions are based on extensive experiments utilizing B7-1–transfected cells and are consistent with studies on certain other tumor types transfected with B7 [4]. J558 expresses class I and, once costimulatory molecules are available, direct activation of CD8+ T cells could potentially occur. The failure of the 5 nM and 10 nM TSA-treated tumor cells to induce immunity via the class I pathway might result from insufficient costimulation. This could however be a significant pathway with the 25 nM TSA-treated J558 vaccine although the lack of immunity in the LPAM and γ-irradiation groups having class I and costimulatory factors suggests that other factors such as class II expression may be involved. An important issue still to be resolved is whether the presence of apoptotic cells in the 25 nM TSA preparations, that induce optimal immunity, contributed to the enhanced immunity. The induction of immunity by apoptotic tumor cells has been related to their ability to induce inflammation and to mature DCs, perhaps owing to the presence of necrotic cells and heat shock proteins in many apoptotic cell preparations [1, 7, 17]. In addition to the possible conversion of tumor cells to APCs, mentioned above, the combination of replicating antigen-producing live cells with an apoptotic adjuvant-like effect could explain the superiority of the 25 nM TSA-treated cells. Consistent with a role for apoptotic cells in synergizing with live cells in eliciting immunity is the report of the enhancement of DC vaccine potency by the addition of apoptosis-promoting agents [3]. It would be expected that both viable and apoptotic cells would contain tumor antigen for cross-presentation; however since the amount of tumor antigen may be critical in eliciting immunity [22], an additional possibility is that TSA up-regulates an endogenous tumor antigen and thus enhances cross-presentation. The role of NK cells in the J558 model was not definitively assessed; although the similar growth rates and outcomes of challenge with TSA-treated or untreated tumor cells in SCID mice suggest that NK cells are not sufficient for immunity.

Certain chemotherapeutic drugs, when given systemically in combination with whole cell cancer vaccines, have been reported to augment the efficacy of the vaccine [8]. While several different mechanisms may mediate these drug/vaccine synergies, one possibility is that certain drugs given systemically may change the spectrum of immune genes on tumor cells as shown in vitro with TSA. In this regard, apoptotic cells induced by different drugs have been found to differ in their gene expression patterns (Magner WJ et al., manuscript submitted). Thus, epigenetic vaccines, as demonstrated here, could provide a set of immune enhancers that would be best augmented by specific drugs given systemically. Recently, several deacetylase inhibitors including SAHA, depsipeptide (FR901228), and MS-275 have been introduced into clinical trials on the basis of their ability to induce differentiation and apoptosis of tumor cells [10, 18]. It will be of interest to determine if the systemic administration of deacetylase inhibitors also alters expression of immune genes and/or tumor antigens in the several tumors being investigated.

The data presented demonstrate that immunity can be elicited in both murine plasmacytoma and melanoma tumor models by epigenetically altered tumor cells. Future studies are necessary to determine whether this approach is applicable to other tumors and to optimize the agents and methods employed in the epigenetic vaccine protocols. These data suggest the possibility that tumors treated with agents that alter chromatin in vitro, could be used, perhaps in combination with other strategies, to create effective epigenetically designed vaccines. If such vaccines can be developed, they would have the advantage of being histocompatible with the host and applicable without prior knowledge of the tumor antigens involved.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elizabeth A. Repasky and Protul Shrikant for critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- CIITA

MHC class II transactivator

- CTLs

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- HDACs

histone deacetylases

- LPAM

L-phenylalanine mustard

- TSA

trichostatin A

Footnotes

This work was supported by grant HD 17013 from the National Institutes of Health, and utilized core facilities supported in part by RPCI’s NCI Cancer Support Grant CA16056.

References

- 1.Basu Int Immunol. 2000;12:1539. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250477697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Candido Cancer Res. 2001;61:228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen J Exp Med. 1994;179:523. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicklin Mol Med Today. 1999;5:178. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01451-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inaba J Exp Med. 1998;188:2163. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machiels Cancer Res. 2001;61:3689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magner J Immunol. 2000;165:7017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:194. doi: 10.1038/35106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narlikar Cell. 2002;108:475. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostrand-Rosenberg Immunol Rev. 1999;170:101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piskurich Nature Immunol. 2000;1:526. doi: 10.1038/82788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pulaski Cancer Res. 1998;58:1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qi J Immunol. 2000;165:5451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramarathinam J Exp Med. 1994;179:1205. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Restifo Curr Opin Immunol. 2000;12:597. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(00)00148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosato Cancer Res. 2003;63:3637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silacci J Exp Med. 1994;180:1329. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smale Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soos Glia. 2001;36:391. doi: 10.1002/glia.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiotto Immunity. 2002;17:737. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart CC, Stewart SJ (1997) Immunophenotyping. In: Robinson JP, Darzynkiewiez Z, Dean P, Dressler L, Rabinovitch P, Stewart C, Tanke H, Wheeless L (eds) Current protocols in cytometry. Wiley, New York, p 6.2.1

- 24.Toes J Exp Med. 1999;189:753. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2592. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.7.2592-2603.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Cancer Res. 1999;59:3461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]