Abstract

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation represents the only curative approach for many hematological malignancies. During the last years the impact of the conditioning regimen has been re-assessed. With the advent of reduced-intensity conditioning the paradigm has changed from cytoreduction executed by high-dose radio-chemotherapy to immunological surveillance of leukemia by donor cells. Distinct subsets of T cells and NK cells contribute to graft-versus-leukemia reactions. So far, cytotoxic T lymphocytes are the mainstay of allogeneic immunotherapy. Here, we summarise the current knowledge of T cell-mediated graft-versus-leukemia reactions and present results from pre-clinical and clinical studies of T cell-based adoptive immunotherapy. We address the issues of feasibility and specificity of adoptive immunotransfer from a clinical point of view and discuss the prerequisites for successful clinical applications. Finally, the prospects for immunological research that have evolved with the increasing use of reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic stem cell transplantation are highlighted.

Keywords: Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Reduced-intensity conditioning, Graft-versus-leukemia effects, Minor histocompatibility antigens, Tumor antigens

Introduction

In the last decade the paradigm of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has changed. For several years the focus of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) had been to apply sub-lethal doses of chemo- or radiotherapy in order to eliminate leukemia cells based on the observation that increasing the dose of the conditioning regimen reduces the probability of relapse after transplantation [1–4]. The allogeneic graft was considered mainly as a non-contaminated source of hematopoietic stem cells that restores hematopoiesis. The importance of immunologic tumor control exerted by the donor cells, however, had already been recognized in the early 1960s. One of the pioneers in the field of allogeneic HSCT, Professor George Mathé, the founding editor of Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy, hypothesized that residual leukemia cells could be eradicated totally by this immune reaction and that permanent control of otherwise incurable diseases might be achieved by this means [5, 6]. He considered allogeneic HSCT as a non-specific adoptive immunotherapy [7]. Meanwhile, recognition of the importance of graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects in allogeneic HSCT led to the development of reduced-intensity conditioning regimens [8, 9]. These preparative regimens are highly immunosuppressive and enable stable donor stem cell engraftment [10–12]. Due to the minimal cytoreductive capacity of these regimens, the antineoplastic activity of the whole procedure relies on the GVL effect. Here we present recent insight into the kinetics of GVL effects in the setting of reduced-intensity conditioning. We summarise the current knowledge of potential target antigens for T cell-mediated GVL effects and emphasise the prospect of T cell-based adoptive immunotransfer and potential directions for immunologic research.

Evidence for GVL-reactions

Statistical evidence for the existence of GVL effects came from the observation that patients who suffered from graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after allogeneic HSCT had a lower risk of relapse [13]. Further studies demonstrated that the probability of relapse was related to the degree of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) disparity between donor and recipient and to the number of transfered T cells [14]. The observation of long-term disease-free survival after allogeneic, but not after autologous, HSCT in patients with otherwise incurable diseases such as advanced stages of follicular lymphoma, multiple myeloma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), was considered to reflect GVL effects [15, 16]. Additional evidence for GVL effects came from the observation that the transfusion of donor lymphocytes can exert powerful tumor control and re-induce complete remissions in patients with a relapse after allogeneic HSCT without the application of additional chemotherapy [17, 18]. For example, Kolb and colleagues applied donor lymphocyte infusions to patients with relapsed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) after allogeneic HSCT and observed an impressive remission rate [19, 20]. In some of these patients molecular remissions were achieved and a probability of event-free survival of 87% at 3 years was documented [19, 20].

In the recent past, clinical evidence for GVL effects came from the observation of tumor responses in patients after reduced-intensity conditioning, which could not be attributed to the preparative regimen, and which led to the re-evaluation of GVL effects in various malignancies [11, 21–26].

Kinetics of GVL effects

For a long time the assessment of GVL effects after high-dose radio-chemotherapy and allogeneic HSCT was hampered by the interference of delayed effects of the cytoreductive conditioning regimen and the emerging immunological activity of donor effector cells. Until recently, information on the kinetics of GVL effects was restricted to observations made after DLIs. In patients with relapsed CML after allogeneic HSCT, it took a median of 4 months (range, 2.5–11 months) after DLI until a cytogenetic response could be documented [27]. The median time to PCR negativity in 10 patients was 6 months (range, 2.5–15 months). Kolb et al. [28] reported that molecular remissions achieved by DLI in patients with CML occurred up to 1 year after infusion. Anecdotally, a patient with a follicular lymphoma obtained a complete remission as late as 21 months after DLI without any other antitumoral therapy.

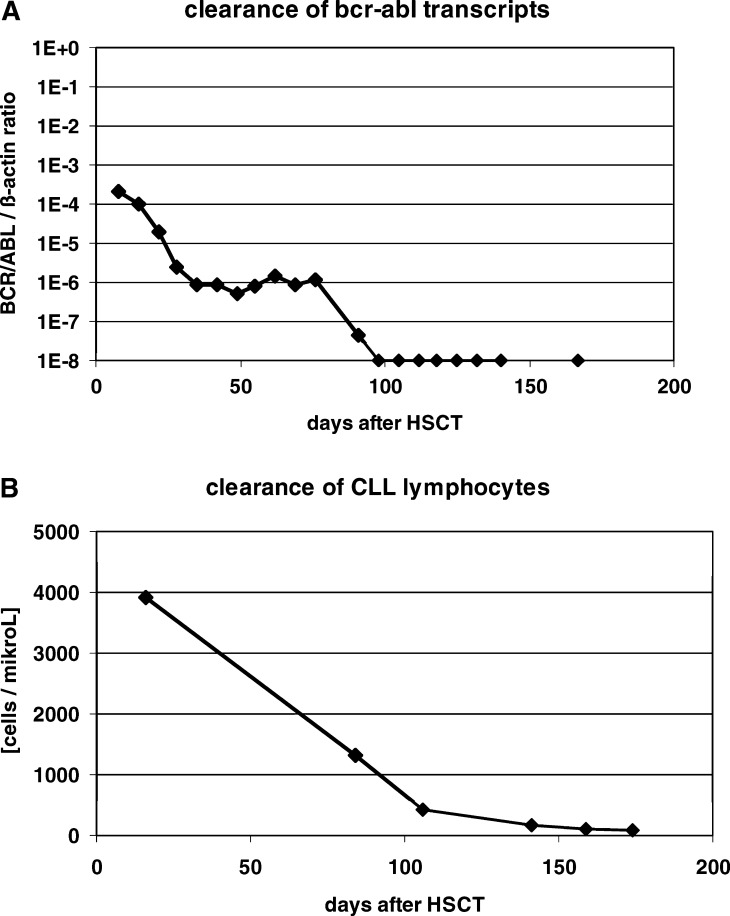

With the advent of reduced-intensity conditioning, the kinetics of leukemia cell clearance in the early phase after allogeneic HSCT could be studied, especially in chronic leukemias. We applied quantitative PCR to monitor the expression of BCR-ABL transcripts in 14 patients with CML after reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic HSCT (Fig. 1a) [29]. The responding patients cleared BCR-ABL transcripts from their peripheral blood after a median of 2 months (range, 1–6 months). Furthermore, a close correlation between the first occurrence of GVHD and the clearance of BCR-ABL positive cells was observed.

Fig. 1.

Elimination of residual disease after reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic HSCT. Panel A shows the course of BCR-ABL transcripts in the peripheral blood, detected by quantitative RT-PCR. The patient was 60 years old and suffered from chronic phase CML refractory to hydroxyurea and interferon alpha. Steroid-refractory GVHD of skin and liver occurred on day 25. Panel B depicts the course of leukemic lymphocytes, characterised by the marker combination CD5+CD19+CD79b-, in a 55-year old patient with chemotherapy-refractory CLL. The patient developed steroid-responsive GVHD of the skin on day 30

In patients with CLL, lymphocytes with the leukemic phenotype as assessed by flow cytometry were cleared from peripheral blood after a median of 4 months (range, 1–14 months) after HSCT (Fig. 1b) [21]. Tumor cell elimination was often a continuous process starting soon after transplantation. Molecular remissions were achieved after a median of 9 months (range, 1–18 months) in these patients. Interesting additional information on the kinetics of tumor cell clearance in CLL came from the comparison of the course of minimal residual disease (MRD), assessed by quantitative PCR using clone-specific primers, after myeloablative conditioning and autologous HSCT versus reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic HSCT [30]. In both groups the MRD level decreased early after HSCT by one log, which may be interpreted as an effect of the conditioning regimen. After allogeneic HSCT, however, a further reduction of the MRD level by 2 logs was observed between day +100 and day +200 while no further decrease was observed in patients who had received an autologous graft.

Similar observations were made in patients with multiple myeloma treated with reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic HSCT [23]. In these patients, the idiotypic protein gradually disappeared over a period of 6 to 12 months in responding patients. An interesting model for the elimination of non-malignant host plasma cells is major ABO blood group incompatible HSCT. Delayed erythroid engraftment in this constellation is caused by isohemagglutinins directed against the donor blood group, which are detectable up to one year after HSCT. The isohemagglutinins are suspected to be produced by host plasma cells that had not been killed by the conditioning treatment. The rate of isohemagglutinin clearance, presumably reflecting the elimination of residual host plasma cells, is dependent on the involved blood group antigens (anti-A is cleared faster that anti-B), and the degree of HLA disparity (faster clearance after unrelated than related HSCT), and correlates with the occurrence of GVHD [31, 32]. (Schetelig, Transfusion, in press)

In summary, there is evidence that the kinetics of tumor cell elimination after DLI and after reduced intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic HSCT are similar in that maximal responses often occur after a remarkable delay of up to 1 year after immunotherapy. However, although maximal responses are achieved late in the course after allogeneic immunotherapy, the fact that leukemia-reactive CTLs can be detected as early as 14 days after transplantation and that an early and continuous decline in the MRD level is observed in responding patients may indicate that donor cells already have the capacity to exert anti-tumor effects soon after transplantation [33].

Prerequisites for effective GVL reactions

The content of marrow blasts is one of the most important factors determining the outcome of allogeneic immunotherapy. This is especially true for CML, where the response rate for patients with CML in transformation or blast crisis drops to 12–36%, compared to 80% in chronic phase CML [20]. In patients with AML, event-free survival after reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic HSCT is highly significantly associated with the percentage of marrow blasts prior to HSCT [34]. It has been hypothesised that in this situation the proliferation of the leukemic blasts outpaces the expansion of tumor-specific CTLs. However, this hypothesis could not be substantiated with immunological data, so that other factors, such as immune escape or resistence to T cell-mediated killing of the blasts, may also be important in this context. As a consequence, in clinical practice allografting in acute leukemia is more or less regarded as a complementing therapy in a status of MRD achieved by conventional chemotherapy. The main function of allogeneic HSCT in acute leukemia is therefore the eradication of residual disease.

In chronic leukemias or low grade lymphoma, in contrast, allogeneic HSCT can be applied to patients with untreated or refractory disease with the goal being to induce remissions [35,21]. In this setting, the question of the necessity of tumor debulking arises. Generally, the perception is that tumor debulking facilitates GVL effects, although there is no formal proof for this hypothesis. In viral infection, it has been demonstrated that excessive antigen challenge leads to TCR downregulation followed by selective deletion of virus-specific CTLs [36]. Experimental data derived from clinical trials further demonstrated that in vivo silencing of CTLs can occur in the immunosuppressive milieu of a tumor [37]. In multiple myeloma it has been demonstrated that idiotype-specific CTLs become anergized if the serum concentration of the respective idiotypic immunoglobulin exceeds certain levels [38, 39]. Additional evidence that the “target-effector cell” relation plays a role, comes from the observation that after reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic HSCT the T cell-dose is correlated inversely with the rate of relapse [40]. The marrow cell dose affects the relapse rate in syngeneic BMT, too, supporting the hypothesis that GVL activity is related to the “target-effector cell” ratio [41]. On the other hand, in day-to-day clinical practice molecular remissions can be induced in patients with a relapse of CML and 100% Philadelphia chromosome positive hematopoiesis by the application of as few as 1×107 donor CD3 cells/kg [42]. In patients with chemotherapy-refractory CLL, successful HSCT after reduced-intensity conditioning has been performed even in full-blown leukemia [21]. These observations argue against the hypothesis that tumor debulking is generally necessary as a precondition for successful immunotherapy. Disease-specific factors conferring protection from T cell-mediated killing as well as host-specific factors determining the capability of in vivo expansion of the transferred T cells might therefore be of equal or greater importance.

Another important question is whether priming with chemotherapy or IFN-α before allogeneic immunotherapy can improve the outcome not only by contributing additional cytoreduction but by enhancing GVL effects. For example, in patients with recurrent AML after allogeneic HSCT, the application of chemotherapy increases the complete remission rate after DLI from 25% to 54% [20, 43, 44]. These clinical observations are substantiated by experimental data obtained in a mouse model, which demonstrate that the application of cytarabine induced the expression of B7-1 and B7-2, two important costimulatory molecules, on AML blasts [45]. Accordingly, the leukemic cells exposed to cytarabine in vivo were more susceptible to specific CTL-mediated killing in this model. In a similar line, IFN-α is able to restore a loss of HLA class I expression and increase the expression of costimulatory molecules in acute leukemia blasts [46]. Altogether, these data fit into a concept in which optimal stimulation of the allogeneic immune response requires ligand recognition in the context of heightened expression of costimulatory molecules, adhesion molecules and HLA-molecules on antigen-presenting cells, providing a “danger signal” to the effector cells. In conclusion, some evidence exists that chemotherapy is a beneficial adjunct to sensitise leukemia cells to the effects of allogeneic immunotherapy.

However, it has to be noted that the upregulation of costimulatory molecules and removal of peripheral T cell tolerance may not only lead to a broad and potent immune reaction against the tumor but may also initiate autoimmunity and GVHD [47, 48]. GVHD itself, driven by major and minor histocompatibility antigenic differences and mediated indirectly by cytokine secretion, presumably contributes to a proinflammatory microenvironment, which might broadly decrease the threshold of TCR activation and drive the expansion of high-affinity self-antigen-specific T cells. Therefore, although GVHD is not mandatory for a GVL effect, it is closely related to it.

Different susceptibility to GVL effects

Surprisingly, the response rates after DLI appear to be higher in patients with myeloid, compared to lymphoid, malignancies [20, 21, 28, 49]. This phenomenon may in part be attributable to an intrinsic resistance of lymphoid blasts to GVL effects.

In general, a number of potential mechanisms have been described by which tumor cells may escape from GVL effects. For example, downregulation and thus ineffective presentation of tumor antigens have been reported for melanoma cells after adoptive immunotherapy [50], which may be the consequence of an altered proteosomal cleavage of proteins [51]. Likewise, HLA class I molecules can be downregulated or even lost, as shown for patients with AML or ALL [46, 52]. Death receptors on the cell surface like CD95 can be downregulated [53, 54]. The lower susceptibility to DLI of chronic lymphoid compared to myeloid leukemia may be partly explained by differences in the expression of death-inducing tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptors, which are found at high levels in most CML cell lines, but only at comparably low levels on the surface of B-CLL cells [55, 56]. A lack of costimulatory molecules crucial for effective T cell-mediated killing (such as B7-1, B7-2 or ICAM-1) has been described for myeloid blasts [53, 54, 57, 58].

Alternatively, the effector cells themselves may be affected. Blunted activation responses of anergic tumor-antigen specific T cells, characterised by decreased secretion of IL-2 or TNF alpha have been described in patients with melanoma [37]. Conversely, antigen-presenting cells derived from the leukemic clone could play a beneficial role. It has been shown that AML and CML blasts have the potential to differentiate into antigen-presenting cells [59–62]. These professional malignant antigen-presenting cells could initiate and maintain leukemia-specific immune reactions in CML highly efficiently. The precise changes conferring resistance or susceptibility to GVL effects are, however, not understood.

Effector cells in GVL reactions

Although the term graft-versus-leukemia reaction suggests specific killing of leukemia cells exerted by donor cells, there is to date no conclusive evidence that GVL reactions are specific. In contrast, it seems more likely that GVL reactions are part of a generalized immune response against the host. Distinct subsets of donor cells including natural killer (NK) cells and T cells contribute to GVL effects. Most T cells exert GVL effects in an antigen-specific, human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted manner, while NK cells kill as a consequence of activating and inhibitory signals delivered by a variety of receptors, including killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors, C-type lectins, and natural cytotoxicity receptors. The relative contribution of NK cells to GVL effects has been increasingly recognized in the past years and has been recently reviewed in this journal [63]. We therefore focus here on an overview of T cell-mediated GVL effects.

Potential target antigens for T cell-mediated GVL reactions

Considerable effort has been made in the last decade to identify target antigens capable of inducing T cell responses directed against tumor cells. GVL effects can occur in the absence of GVHD, indicating that some of those antigens are expressed exclusively or predominantly by the malignant cell. Identification of those antigens could be exploited to augment GVL effects by ex vivo generated antigen-specific CTLs. Two categories of antigens are potential targets: polymorphic minor histocompatibility antigens (mHAgs) and tumor antigens of various specificity—i.e. differentiation antigens that are expressed both on the tumor and the cell of origin, or mutated proteins expressed exclusively on the cancer and not on normal tissues.

Minor histocompatibility antigens

The analysis of a graft failure in a female patient with aplastic anaemia who received a graft from her HLA-identical brother led Goulmy et al. in 1976 to the idea of graft failure mediated by an H-Y antigen presented by the HLA-A2 molecule [64, 65]. In an inverse situation of a male patient with a graft from his HLA-identical sister, who suffered from severe GVHD, the same group found strong cell-mediated lympholysis with HLA-A2-restricted specificity and assumed that a minor histocompatibility antigen (mHAg) played an important role in the development of GVHD [66]. Later on, the contribution of mHAgs to GVL effects was recognized.

Generation of mHAgs

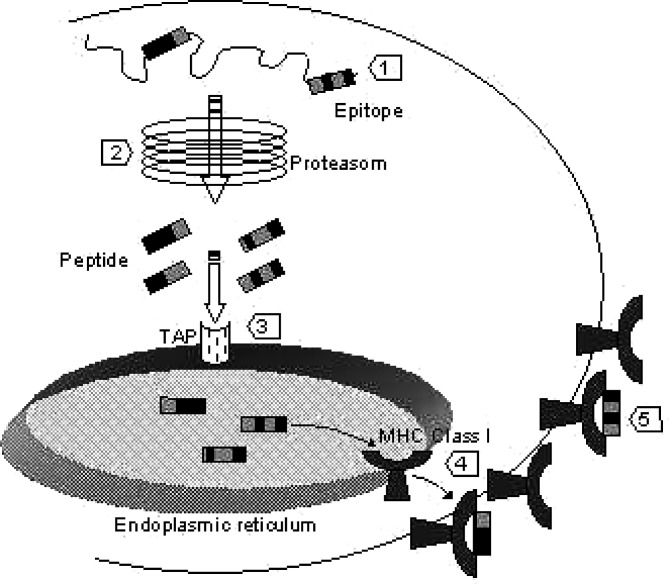

Host mHAgs elicit antigen-specific donor T cell-mediated immune reactions against host cells if the donor does not express the respective antigen and vice versa. Minor histocompatibility antigens are highly immunogenic peptides derived from cellular proteins, which are presented in an HLA-restricted manner. The genetic polymorphism between donor and host accounts for pairs of peptide antigens, the mHAg and it’s negative counterpart (Table 1). The negative allelic peptides may result from modified proteosomal processing, impaired binding to the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) or to the MHC molecule, and from interrupted T cell receptor (TCR) binding to the MHC-peptide-complex (Fig. 2) [67–75]. The variety of modifications giving rise to mHAgs explains that even in HLA-identical siblings mHAgs can differ substantially.

Table 1.

Selected minor histoincompatibility antigens

| mHAg | mHAg disparitya [%] | HLA restriction | Encoding gene | Antigenic peptide | Tissue distribution | Association with GVHD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HY | NA | HLA A*0201 | SMCY | FI DSYI CQV | ubiquitous | Yes[33] | [79] |

| HY | NA | HLA B7 | SMCY | SP SVDKA RAEL | Ubiquitous | Yes[33] | [68] |

| HY | NA | HLA A1 | DFFRY | IVD CLEMY | NK | No | [71] |

| HY | NA | HLA B8 | UTY | LPHN HT DL | Hematopoiesisb | NK | [82] |

| HY | NA | HLA B60 | UTY | RESEE ES VSL | Unknown | NK | [76] |

| HY | NA | HLA DQ5 | DBY | HIE NFSD IDMGE | Ubiquitous | Yes | Vogt 2002 |

| HY | NA | HLA DRB3*0301 | NK | VIKVNDTVQI | NK | NK | [75] |

| HA-1 | 11 [86] | HLA-A*0201 | KIAA0223 | VL HDDLLEA | Hematopoiesis | No[89, 84] | [70] |

| HA-2 | 2.5[86] | HLA A*0201 | MYOIG | YIGEVLVS V | Hematopoiesis | NKc | [67] |

| HA-3 | 14[86] | HLA A*0101 | Lbc | V TEPGTAQY | Ubiquitous | No | [75] |

| HA-4 | 1[86] | HLA A2 | NK | NK | NK | NKc | [86] |

| HA-5 | 2[86] | HLA A2 | NK | NK | NK | NKc | [86] |

| HA-8 | 12[74] | HLA A*0201 | KIAA0020 | RTLDKVLE V | Ubiquitous[74] | Yes[74] | [74] |

| HB-1 | NK | HLA B*4403 | HB-1 | EEKRGSL HVW | B-cells | NK | [81] |

ai.e. incidence of the constellation donor mHAg-negative, recipient mHAg-positive in HLA-matched related donor-recipient pairs

bubiquitous protein expression but limited CTL recognition

cinitial results were not confirmed by an extended analysis [89]

NK denotes not known, NA not applicable

variable regions of the mHAg determining antigenicity are underlined

Fig. 2.

Origin of mHAg differences. Genetic polymorphism between host and donor resulting in amino acid changes give rise to mHAgs (1). Several mechanisms of processing, transport and presentation of the antigen may be involved. For example, alternative proteosomal cleavage can produce peptides with different binding affinities or can result in the destruction of peptide antigens. This is suspected to happen to the negative allelic peptide of HA-3 (2) [75]. The negative allelic peptide of HA-8 presumably cannot bind to the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) essential for the translocation of peptides into the endoplasmatic reticulum and therefore is not displayed on the cell surface (3) [74]. The allelic peptide of HA-1 does not bind to the MHC groove and therefore is not presented by HLA-A2 (4) [69, 70]. Finally, the TCR binding region can be modified as in the case of the mHAgs B7-HY and A1-HY (5) [68, 71]

Identification of mHAgs

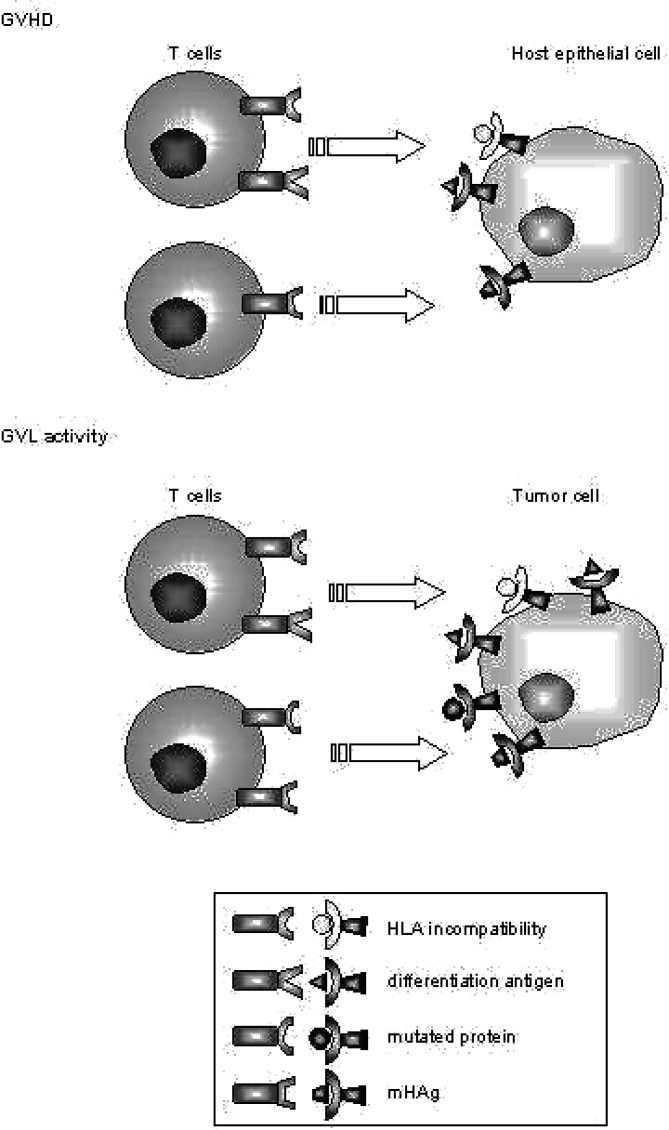

As in matched allogeneic HSCT donor and recipient cells express the same HLA molecules, CTLs that lyse recipient cells but not donor cells are suspected to recognize mHAgs presented by HLA class I molecules. The first mHAg-specific CTL clones were isolated in patients with graft-rejection or severe acute GVHD, both situations in which clonal expansion of CD8+ T cells plays a crucial role [64, 76]. Warren et al. demonstrated that it is possible to isolate recipient-reactive CTL clones with mHAg specificity in standard situations after allogeneic HSCT in a high percentage of donor-recipient pairs [77]. Twelve out of seventeen identified mHAg-specific CTL lines lysed hematopoietic cells but not fibroblasts derived from the same patients. The authors thereby demonstrated that CTLs capable of mediating GVL activity can be isolated from a significant proportion of allogeneic HSCT recipients (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Antigen-specific activity of donor T cells. The cartoon demonstrates the induction of GVH and GVL activity. HLA disparity is a potent stimulus for the induction of GVH reactions. As tumor cells display the host phenotype, they can be eliminated as part of a generalized GVH reaction. Minor histocompatibility antigens initiate immune reactions if the donor and host are mismatched for a mHAg in GVH direction, i.e. the donor is mHAg negative and therefore not tolerant to a mHAg which is presented by HLA molecules of the host. The relative contribution of mHAgs to GVHD or GVL effects depends on their tissue distribution. If, for example, the respective mHAg is presented only on hematopoietic cells a strong GVL activity can be expected as part of a generalized graft versus “host-hematopoiesis” reaction. Tumor antigens which represent differentiation antigens will induce immune reactions depending on their tissue distribution. These antigens represent self-antigens for the donor immune system. Tolerance must be broken so that these antigens initiate GVHD or GVL effects. The optimal target is an immunogenic peptide derived from a mutated protein which is unique to the malignant cell, since these cells induce GVL effects only.

Three methods have been successfully applied for the identification of the peptides defining HLA-restricted mHAgs: in the first approach, high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry were used to directly fractionate and sequence peptides eluted from purified HLA molecules of mHAg-positive cells [78]. The mHAgs HA-1, HA-2 and HA-8 as well as minor H antigens encoded by the Y chromosome were identified with this technically sophisticated method [68, 71, 79]. A second approach employed cDNA expression cloning, in which cDNA libraries of mHAg-positive cells were systematically cotransfected with plasmids encoding the HLA class I-restricting allele into mHAg-negative cells [80]. The mHAg-specific CTL clones were subsequently used to screen the transfectants. This method proved successful for the identification of autosomal mHAgs HB-1 and two sex chromosome-linked mHAgs [76, 81, 82]. Finally, genetic linkage analysis was recently demonstrated by Warren and colleagues to be an alternative method to identify genes encoding mHAgs [83]. For the identification of HA-8, an HLA-A*0201-restricted mHAg, cells from family members of completely genotyped large pedigrees were transfected with a vector encoding an HLA-A*0201 transgene. The transfectants were screened with the mHAg-specific CTL clone. The resulting data were used for pair-wise linkage analysis. Within the chromosomal region, which showed a clustering of marker loci, two genes with single nucleotide polymorphisms producing missense amino acid sequence changes were identified as targets. Peptides derived from proteins spanning the polymorphic regions in these two genes were finally ranked according to their predicted binding affinity to HLA-A*0201 and tested in TCR reconstitution assays [74].

A major goal would be to identify mHAgs, which are selectively expressed on hematopoietic cells or at best only on the tumor cells. Therefore, calculated searches for mHAgs derived from polymorphic tumor antigens would be desirable. HA-3 and HB-1, for example, are selectively expressed on B-lymphoid cells but not on cells of non-hematopoietic tissue [75, 81]. Targets like these theoretically offer the opportunity to direct adoptive immunotherapy against tumor mHAgs in patients with B-cell neoplasms.

Evaluation of the contribution of mHAgs to GVH and GVL-reactions

Pre-clinical evaluation

The extent to which mHAgs contribute to desired GVL effects or potentially life-threatening GVH-reactions largely depends on the tissue distribution of the antigen [84, 85]. Tissue distribution has to be analysed at different levels in vitro. Functional data can be generated by cytotoxicity assays with the mHAg-specific CTL clones [84] [77]. While these assays are close to the in vivo situation, they depend on the availability of tissue from donor and recipient, which is generally limited to easily accessible cells such as hematopoietic cells and fibroblasts. Gene expression analyses can easily be performed with commercially available RNA derived from various human tissues [73, 82]. However, the quantitative level of expression may be an important factor for CTL recognition, as demonstrated for HA-2 and B8-H-Y. For example, mRNA of the encoding gene for HA-2 (MYO1G) is expressed at low levels in fibroblast and keratinocyte cell lines, but HA-2-specific CTLs do not recognize these cells in cytotoxicity assays [73]. Among other reasons, differential peptide display may be explained by tissue-specific or, in the case of the H-Y antigen, sex-specific post-translational processing of the protein. Therefore cytotoxicity assays with the mHAg-specific CTL clones remain the gold standard for the evaluation of mHAgs.

In a very elegant way, GVH activities of mHAg-specific CTLs have been visualized in a skin-explant model [84]. In this model, skin sections from patients typed for HLA and mHAg were incubated with mHAg-specific CTLs. In situ GVH-activity was measured according to pathological classification systems and by interferon (IFN) gamma production. The authors demonstrated that HA-1 and HA-2, which are expressed only in hematopoietic cells, induced no, or little, GVHD, while H-Y-specific CTLs exerted considerable GVH-activity in male skin sections.

Clinical evaluation of mHAg disparity

Insight into the kinetics of mHAg-specific CTLs in GVHD was obtained by staining with tetrameric HLA-peptide complexes [33]. This has been done for the HLA-A2-restricted HA-1, HA-2 and two H-Y mHAgs that bind to HLA-A2 and HLA-B7. As early as 14 days after HSCT, mHAg-specific CTLs were detectable. Mutis et al. [85] demonstrated that the frequency of HA-1- and H-Y-specific CTLs increased significantly during clinically manifest acute or chronic GVHD and decreased after successful GVHD treatment. Marijt et al. [85] extended tetramer analyses of HA-1- and HA-2-specific CTLs to patients who had received DLI and were able to demonstrate that CD8+ T cells with this specificity emerged in the blood five to seven weeks after DLI. Of special importance, the appearance of tetramer-positive cells correlated closely with the occurrence of complete remission and restoration of 100% donor chimerism. Therefore in this study, the occurrence of mHAg-directed effector CTLs may have correlated with the onset of a GVL effect. The role of H-Y-specific CTLs in graft rejection was confirmed by the analyses of Vogt et al. who isolated H-Y-specific cytotoxic T cells from a female HLA B60+ patient with aplastic anaemia who had rejected an HLA-identical male stem cell graft [76]. The CTL clone identified a UTY-derived peptide displayed by the HLA B60 molecule.

Autosomal chromosome-encoded mHAgs

Enormous efforts have been made to evaluate the impact of single mHAgs-disparities on the transplant outcome in terms of GVHD and relapse rate. However, due to their restriction to certain HLA-types and frequency, large cohorts of patients have to be analysed. The story of HA-1, the best studied mHAg, is an example of the obstacles related to the evaluation of the influence of mHAg-disparities on transplant outcome [86–89]. The nonapeptide HA-1 is encoded by the autosomal gene KIAA0223 and presented by HLA A2 [70]. HA-1 is displayed by 69% of HLA-A2- positive individuals. HLA-A2 itself is expressed in about 50% of the Caucasian population. Nevertheless, only about 15% of HLA-A2 sibling transplants expose HA-1-disparity in the GVH direction (Table 1) [88, 89]. In a first analysis of 117 patients dated from 1996, an HA-1 mismatch in GVH-direction was associated with the occurrence of GVHD. HA-1 typing had been performed with HA-1-specific CTL clones demonstrating 13 patients with an HA-1 mismatch. After the identification of the gene encoding HA-1 [70], a second retrospective analysis of 237 HLA-A2-positive sibling transplants was performed at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, using molecular techniques for mHAg typing. The initial observation was confirmed [87]. However, in an extended analysis of 613 HLA-A2-positive patients including 80 HA-1 incompatible patients, the same authors were finally not able to re-confirm their previous results [89]. This example underlines the complexicity and difficulties in studying the role of mHAgs in allogeneic HSCT and highlights the present restrictions on exploiting mHAg disparity therapeutically.

On the other hand the observation that in donor-recipient pairs with an HA-1- and/or HA-2-mismatch in GVH direction up to 33% of the CTL clones generated from patient blood after DLI were specific for HA-1 and HA-2, underlines the role of mHAgs in GVL reactions [90]. It concurs with the idea that mHAgs are expected to elicit stronger immune reactions than self-antigens or tumor antigens since they can be recognized as non-self by the donor immune system. In turn, the fact that 67% of the leukemia-reactive CTL clones were of unknown specificity demonstrates that GVL reactions do not appear to be directed against single potent antigens.

Sex chromosome-encoded mHAgs

In a recently published study of 3238 patients evaluating the influence of donor and recipient sex on the outcome of allogeneic HSCT, a lower relapse rate was found in male recipients with female stem cell donors compared to other sex combinations [91]. This association held true even after controlling for GVHD. The latter observation suggests that minor H antigens encoded or regulated by the Y chromosome are responsible for a selective GVL effect. Earlier Gratwohl et al. [92] had already shown that male recipients with CML in first chronic phase who had received a graft from a female donor had a lower relapse rate than female recipients of female donors. Thus, there is compelling evidence that H-Y antigens contribute to GVL-reactions.

Tumor antigens

The largest group of tumor antigens considered as targets for T cell-mediated GVL effects in hematological malignancies are differentiation antigens and therefore can be considered as self-antigens. Ideally, the respective antigen is overexpressed or cell type-specific. Since these antigens are not exclusively expressed on tumor cells however, they theoretically could also initiate GVHD reactions (Figure 3). Still, directing GVH reactions against tumor antigens would be a further step towards a targeted immunotherapy.

Proteinase 3

The HLA-0201*-restricted 9-mer peptide PR1 is probably one of the best studied tumor-associated antigens. This peptide derives from proteinase 3, a serine protease that is induced at the promyelocyte stage of myeloid differentiation. Proteinase 3 is overexpressed in a variety of myeloid malignancies including CML in blast transformation and AML. Inhibition of proteinase 3 in the HL60 leukemia cell line inhibits cell proliferation and induces differentiation [93]. Patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis exhibit T cells that proliferate in response to purified proteinase 3 suggesting that peptides derived from this protein elicit T cell responses. The peptide PR1 is a deduced peptide epitope in that it was identified through scanning the proteinase 3 sequence for the HLA-A2 binding motif [94]. It was selected from a number of candidate peptides, based on its predicted high binding affinity to the MHC molecule binding motif of HLA-A2. The peptide was synthesized and CTL lines specific for PR1 were generated from healthy donors. These CTL showed HLA-restricted cytotoxicity and colony inhibition of myeloid leukemia cells that overexpress proteinase 3 but not of normal bone marrow cells [95]. Cell killing due to polymorphic differences of PR1 was excluded by sequencing the exons encoding PR1 of donor and target cells. Using a PR1/HLA-A2 tetramer, low frequencies of PR1-specific CTLs were identified in healthy donors [96]. These experiments demonstrated that PR1 is a naturally processed peptide and that CTLs directed against this peptide are present in the TCR repertoire of healthy individuals. Compelling evidence that PR1-specific CTLs participate in the elimination of CML came from the observation that PR1-specific CTLs appeared in the blood of patients who were treated with IFN-α and achieved a cytogenetic response but remained absent in non-responders [97]. Furthermore, six of eight patients with complete remissions of CML after allogeneic HSCT showed detectable levels of PR1-specific CTLs. One patient with a relapse after allogeneic BMT, at a time when no circulating PR1-specific CTLs were detected, received DLI but failed to respond. PR1-specific CTLs remained undetectable after DLI in this patient. In contrast, a second patient who developed PR1-specific CTLs after DLI achieved a complete remission. This observation may be interpreted as an indication that PR1-specific CTLs participate in GVL reactions. However, because PR1/HLA-2 tetramer-negative cells of this patient exhibited lysis of Philadelphia chromosome positive recipient bone marrow as well, non-PR1-specific CTLs likely have also contributed to the elimination of CML.

Rezvani et al. [98] systematically searched with very sensitive assays for PR1-reactive CTLs in healthy persons and patients with CML. Low frequencies of antigen-specific T cells were identified in healthy donors and displayed an immune phenotype of memory T cells. Higher frequencies were identified after allogeneic HSCT in patients with CML. Molldrem et al. demonstrated that the TCR-repertoire in healthy persons contains high and low-avidity PR1-specific T cells [99]. Patients with untreated CML had no high-avidity PR1-specific T cells whereas low-avidity PR1-specific T cells could readily be expanded. Interestingly, in those patients who achieved a cytogenetic remission with IFN-α treatment, high-avidity PR1-specific T cells re-appeared in the circulation. High-avidity PR1-specific T cells killed CML cells twofold more effectively and therefore were suspected to play an important role in disease control. On the other hand, high-avidity PR1-specific T cells underwent apoptosis when exposed to overexpressed proteinase 3 antigen. The authors concluded that CML might cause immunologic tolerance towards the leukemic clone by selective deletion of high-avidity effector cells. Although the authors could not provide conclusive evidence that PR1-specific immune reactions indeed contribute to successful immunotherapy of patients with CML, their data suggest that the issue of the avidity of ex vivo-expanded lymphocytes and mechanisms of tolerance induction have to be addressed in adoptive immunotherapy.

WT1 and survivin

Other potential tumor antigens have been evaluated in preclinical models. HLA-restricted CTLs against naturally processed Wilms tumor protein (WT1) were isolated by Ohminami et al. [98, 100–102] and shown to lyse leukemia cell lines in a specific way. Furthermore, WT1 peptide vaccination elicited WT1-specific CTLs and exhibited clinical activity in patients with AML [103]. Another promising candidate target is Survivin, an anti-apoptotic protein overexpressed in a wide variety of highly proliferating malignancies [104, 105]. Survivin-specific CTLs were able to protect mice against lymphoma challenge and to specifically lyse CLL cells as well as a variety of haematological cell lines derived from B-NHL, B-ALL or multiple myeloma [106–109]. Although these proteins may prove to be promising targets, no data from clinical studies evaluating adoptive immunotherapy are yet available.

Idiotype

Structures of the idiotypic immunoglobulin from malignant B cells are further interesting tumor antigens in B-cell lymphoma. Most of the current knowledge about the immunoglobulin idiotype as a potential target for GVL reactions stems from its evaluation for vaccination strategies done by Ronald Levy and Lerry Kwak [110–112]. Vaccination with immunoglobulin protein conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) induced tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells immune responses in patients with follicular lymphoma [113]. Pre- and post-vaccination cytotoxicity assays demonstrated that these responses were vaccine-induced. Residual molecular disease disappeared in 8 out of 11 patients. These experiments have been extended to the setting of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in patients with multiple myeloma. Lerry Kwak et al. [114–116] immunised a single healthy sibling donor before bone marrow donation with myeloma immunoglobulin conjugated to KLH from the plasma of the recipient. After myeloablative conditioning and bone marrow transplantation, a lymphoproliferative response was detected and the recovery of a CD4+ T cell line of donor origin with unique specificity for myeloma idiotype proved that the idiotype-specific T-cell response had been successfully transferred to the recipient. Since then, five additional donor-recipient pairs have been treated [117]. Two patients died from transplantation-related complications while the remaining three patients were alive in continuous complete remission 3.5–5 years after allogeneic HSCT. Independently, the transfer of myeloma idiotype-specific immunity via DLI after donor immunisation with conjugated purified myeloma protein has been described in a patient with a relapse after allogeneic HSCT. Interestingly, the patient achieved a complete remission without GVHD after lymphocyte infusion [118]. The exact antigenic structures that mediated these immune responses are unknown. There is indirect evidence that peptides derived from the complementarity-determining region are less immunogenic than peptides from the framework region [119]. Despite reduced specificity of such an approach, targeting peptides from the framework region could therefore harbor better prospects of success. Furthermore it could be realised at lower cost, since peptides derived from the framework regions are shared among individuals. This would be especially interesting for patients with B-CLL who exhibit a skewed usage of Ig genes in which 48% of the leukemic clones express the V(H)3 gene, followed by V(H)1 (27%) and V(H)4 (20%) [120].

BCR-ABL

CML is characterized by the Philadelphia chromosome, which represents a reciprocal translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22 t(9;22)(q34;q11). The molecular consequence is a chimeric fusion gene, which is translated into a 210-kd or 190 kd protein with tyrosine kinase activity, inducing transformation of the malignant clone. The junctional region of p210 and p190 contains a unique sequence of amino acids. Peptides spanning this junctional region therefore represent antigens that are exclusively expressed by tumor cells exhibiting this translocation. Immune responses against the BCR-ABL peptide could therefore mediate highly specific anti-tumor effects without setting the patients at risk of GVHD (Fig. 3). As early as in 1992, Chen et al. [121] demonstrated T cell immunity to the joining region of the p210 BCR-ABL protein in a mouse model. Bocchia et al. were the first to demonstrate binding of peptides spanning the b3a2 breakpoint to HLA-class I molecules (A3, A11, B8) and showed that specific CTLs derived from healthy donors killed PBMC pulsed with these peptides in an HLA-restricted manner [122, 123]. Later on, a 9-mer peptide spanning the breakpoint region that had not been predicted to fit the HLA-A2 binding motif was identified in a thermostabilization assay [124]. CTLs generated from healthy donors recognized HLA-matched target cells pulsed with synthetic peptides derived from each of the antigens [124]. Furthermore, these CTLs recognized HLA-matched tumor cells carrying the same translocation, implying that the BCR-ABL fusion protein is naturally processed and efficiently presented on the cell surface. Applying mass spectrometry, Clark et al. [125] were able to elute and identify the HLA-A3.1-restricted peptide KQSSKALQR from HLA-A3-positive CML cells. In addition, recognition of b3a2 fusion peptides by CD4+ T helper cells has been shown [126, 127]. Furthermore, even peptides derived from the corresponding fusion product ABL-BCR elicit T cell responses [128]. Taken together, there is compelling evidence that peptides spanning the breakpoint region of BCR-ABL are presented on the cell surface and that these antigens initiate immune responses.

Surprisingly, in one series high frequencies of BCR-ABLb3a2 -specific CTLs were found in 5 out of 21 CML patients. However, only some of the BCR-ABLb3a2 -specific CTLs were able to kill autologous CML cells or HLA-matched EBV-transformed cells pulsed with BCR-ABL peptide. These data are in line with the observation that BCR-ABLb3a2 -specific CTLs can be isolated from untreated patients and might reflect peripheral tolerance. Possible mechanisms of peripheral tolerance are ignorance, anergy, TCR down-regulation, suppression of autoreactive T cells by regulatory T cells or selective deletion of high avidity CTLs as discussed above for PR1-specific CTLs [129]. Which of these mechanisms is predominantly responsible for the suspected tolerance of BCR-ABL-specific CTLs, however, is unknown. Nevertheless, the fact that individuals coexpressing HLA-A3 and HLA-B8 are underrepresented among patients with CML who received an allogeneic HSCT, indicates that T cell immunity indeed may play a protective role against the development of CML [130]. One possible explanation for this observation could be that the effective presentation of BCR-ABL breakpoint peptides induces a protective immune response in these individuals.

Adoptive immunotransfer

Reconstitution of EBV- or CMV-specific immunity

The feasibility of adoptive immunotransfer has been demonstrated for the reconstitution of EBV- and CMV-specific immunity [131, 132]. In one trial patients considered to be at high risk for EBV-induced lymphoma received ex vivo expanded antigen-specific CTLs after marking them with a neomycin resistance gene. After infusion of these cells, a rise of up to 4 logs of EBV-specific CTLs in the peripheral blood was observed, demonstrating in vivo expansion of the transfused cells [133]. The viral DNA levels decreased 2–4 logs. None of the patients developed EBV-associated lymphoma. In addition, the application of EBV-specific CTLs induced complete remissions in patients with EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease [132]. Long-term persistence and functionality of the CTLs was shown. In one patient, a 2-year-old boy, EBV-specific CTLs were detectable for a period of 14 weeks after immunotherapy. In the following months, the marker DNA dropped below the limit of detection, until 19 months after immunotherapy when a 500-fold rise in the EBV-DNA level was noted and subsequently the gene marker became detectable again in the peripheral blood [134]. Long-term follow up analyses showed that the neomycin resistance gene could be detected up to 6 years after infusion [135]. No GVHD occurred after the application of these EBV-specific CTLs. The reconstitution of CMV-specific immunity has been demonstrated similarly [131, 136].

Adoptive immunotransfer of CTLs with unknown antigen-specificity

Unfortunately, the application of adoptive immunotherapy as anti-tumor therapy has not been as successful as it has been for the treatment of EBV or CMV infections. Ex vivo expansion of leukemia-reactive CTLs appears to be promising in situations where the leukemic cell can be differentiated in vitro into a professional antigen-presenting cell. Choudhury et al. [59–61] were the first to demonstrate in patients with CML that bone marrow cells with the translocation t(9;22) can be differentiated into antigen-presenting cells in vitro and that these malignant dendritic cells were potent stimulators for CTL lines. Autologous CTLs generated with this approach displayed vigorous cytotoxic activity against CML cells but low reactivity against MHC-matched normal bone marrow cells. Falkenburg et al. [137] reported in 1999 the first successful application of this strategy in a single patient with relapsed CML after allogeneic HSCT, who achieved a molecular remission after the application of leukemia-reactive CTLs. More recently, this approach proved to be also effective for leukemic lymphocytes from patients with CLL and for cells from follicular lymphoma after activation with CD40 ligand [138–140]. Hoogendoorn et al. used this approach with cells from patients with CLL and from HLA class I matched donors. The authors generated leukemia-reactive CD8+ CTL lines that specifically killed B-CLL cells but not EBV-transformed donor B cells [141]. In another promising approach, Muller et al. transfected monocytes-derived dendritic cells with tumor-derived RNA isolated from autologous B-CLL cells and showed that they induced leukemia-specific CTL lines and proliferative T cell responses [142]. Specific MHC class I-restricted cytotoxic activity against the autologous leukemic B cells was demonstrated whereas non-malignant B cells were spared. However, data from clinical trials are still lacking.

Adoptive immunotransfer of CTLs with defined anti-tumor specificity

The feasibility of generating sufficient numbers of mHAgs-specific CTLs ex vivo, which efficiently lyse AML or ALL blasts in vitro and exhibit in vivo activity in animal models, has been demonstrated [143, 144]. Bonnet et al. [145] reported that mHAg-specific CD8+ CTL clones protect NOD/SCID mice against leukemic challenge [145]. Fontaine et al. [146] demonstrated that mice that had been immunized with the mHAg, B6dom1, resisted leukemic challenge with leukemic cells presenting the B6dom1 -peptide. The authors extended this model to an allogeneic transplant setting after myeloablative irradiation. B6dom1 -negative recipient mice that received bone-marrow cells and splenocytes from B6dom1 -negative donor mice, immunized with B6dom1 -peptide, survived B6dom1 -positive leukemic challenge. In the same setting B6dom1 -positive mice that received donor cells from B6dom1 -positive mice, immunized in the same way, died. These experiments clearly demonstrated that CTLs primed against a single MHC class I-restricted mHAg (B6dom1) can produce a curative anti-leukemic response. This and other experiments demonstrate that in mice, targeted immunotherapy against selected mHAgs works highly efficiently.

Clinical trials

Data on clinical trials using antigen-specific CTLs are still rare. Marijt et al. [85] reported clinical data on three patients with HA-1- and/or HA-2-positive malignancies (CML and multiple myeloma) who suffered from relapse after allogeneic HSCT and received DLI from their HA-1- and/or HA-2-negative donors. Strikingly, all three patients achieved complete remissions subsequent to the emergence of HA-1- and HA-2-specific CD8+ T cells five to seven weeks after DLI. Tetramer-positive HA-1- and HA-2–specific CTLs generated from the patients blood after DLI specifically recognized HA-1- and HA-2- expressing malignant progenitor cells of the recipient in vitro. Although the temporal association between the emergence of HA-1- and HA-2-specific CTLs and the occurrence of remissions is striking, it is possible that the remission was induced by CTLs with other specificity because a standard DLI contains T cells with a broad TCR repertoire. The only clinical trials so far using antigen-specific CTL clones have been performed in patients with metastatic melanoma [50]. Yee et al. treated 10 patients with ex vivo- selected and expanded autologous T cell clones specific for MART1/Melan A or gp100 together with IL-2. They demonstrated migration of the transfused lymphocytes to the tumor sites and three out of 10 patients had minor or mixed responses lasting for up to 21 months. In tumor samples taken before and after immunotherapy, a selective loss of the targeted antigens in the latter biopsy was remarkable. One conclusion of the authors therefore was, that effective immunotherapy should target multiple antigens. Rosenberg’s group recently published updated and extended data of a clinical trial addressing the efficacy of adoptive transfer of ex vivo-expanded tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and high-dose interleukin-2 therapy to patients with metastatic melanoma after immunosuppressive conditioning in the autologous setting [147]. They observed autoimmunity represented by vitiligo and uveitis and objective clinical responses in 18 out of 35 patients, including 4 patients with complete remissions. The cells capable of mediating tumor regression consisted of a heterogenous lymphocyte population with high avidity for tumor antigens, for example the non-mutated differentiation antigens MART-1 and gp100 as demonstrated by cytokine secretion assays. Several characteristics of this clinical trial could explain the excellent results [48]: First, the application of immunosuppressive chemotherapy, which may have resulted in the destruction of regulatory cells or the abrogation of other tolerogenic mechanisms; Second, the application of both CD4+ and CD8+ cells, in which CD4+ T cells may have supported the documented expansion and persistence of tumor-reactive CD8+ cells; Third, the fact that the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes exposed a broad reactivity against various tumor antigens. Although these data derive from an autologous adoptive immunotherapy approach of a solid tumor, it seems to be important to note that the modulation of the adoptive immunotransfer setting by using a preparative regimen similarly used in allogeneic HSCT resulted in autoimmunity and in tumor responses. Currently, our group is conducting a clinical study in patients with high-risk CML on the safety and efficacy of the application of ex vivo-expanded peptide-specific T cells after T cell-depleted HSCT. The rationale of this study is to provide additional CML-specific T cell immunity in a situation where patients are at high risk of relapse but at a low risk of GVHD. To date, no reports exist in the literature where a successful application of ex vivo-generated antigen-specific CTLs in haematologic diseases has been described.

Conclusions

For more than two decades, the principal goal in the field of allogeneic HSCT was to segregate beneficial GVL effects from potentially life-threatening GVHD. Yet, evidence from immunologic research and from clinical observations indicates that powerful GVL effects are related to a status of “heightened immunity,” which is associated with a loss of anti-tumor specificity and the occurrence of GVHD. This dilemma cannot be resolved. However, the optimal balance of effectivity on one hand and of anti-tumor specificity on the other hand still has to be determined. Progress has been made in the characterisation of the preconditions for successful stem cell engraftment and of potential effector cells for GVL effects and their targets. Allogeneic HSCT after reduced-intensity conditioning now offers an excellent framework for immunologic research of GVL effects. In this setting, the clearance of tumor cells is exerted almost exclusively by immunologic mechanisms and the differential impact of CTLs directed against various types of antigens can be studied “online” in relation to the kinetic of tumor cell clearance or the occurrence of GVHD. There is a reasonable chance that a better understanding of GVL effects will lead to more specific adoptive immunotherapy as projected by pioneers of allogeneic HSCT like Prof George Mathé. The “proof of principle” of successful specific adoptive immunotherapy has been provided by the examples of reconstitution of CMV and EBV-specific immunity. Yet, the optimal target antigens and conditions have to be defined for more specific adoptive anti-tumor immunotherapy in the setting of allogeneic HSCT.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank K. A. Kreuzer and U. Oelschlägel who provided data on the clearance of BCR-ABL transcripts and leukemic lymphocytes in CLL after allogeneic HSCT, respectively. We also are grateful to S. Reimer for skilful technical assistance.

References

- 1.Clift RA, Buckner CD, Appelbaum FR, Bearman SI, Petersen FB, Fisher LD, Anasetti C, Beatty P, Bensinger WI, Doney K, et al. Allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first remission: a randomized trial of two irradiation regimens. Blood. 1990;76:1867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clift RA, Buckner CD, Appelbaum FR, Bryant E, Bearman SI, Petersen FB, Fisher LD, Anasetti C, Beatty P, Bensinger WI, et al. Allogeneic marrow transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the chronic phase: a randomized trial of two irradiation regimens. Blood. 1991;77:1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blume KG, Long GD, Negrin RS, Chao NJ, Kusnierz-Glaz C, Amylon MD. Role of etoposide (VP-16) in preparatory regimens for patients with leukemia or lymphoma undergoing allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1994;14(Suppl 4):S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch MH, Petersen FB, Appelbaum FR, Bensinger WI, Clift RA, Storb R, Sanders JE, Hansen JA, Buckner CD. Phase II study of busulfan, cyclophosphamide and fractionated total body irradiation as a preparatory regimen for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in patients with advanced myeloid malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathe G, Amiel JL, Schwarzenberg L, Cattan A, Schneider M. Adoptive immunotherapy of acute leukemia: experimental and clinical results. Cancer Res. 1965;25:1525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathe G, Amiel JL, Schwarzenberg L, Cattan A, Schneider M, Devries MJ, Tubiana M, Lalanne C, Binet JL, Papiernik M, Seman G, Matsukura M, Mery AM, Schwarzmann V, Flaisler A. Successful Allogenic Bone Marrow Transplantation in Man: Chimerism, Induced Specific Tolerance and Possible Anti-Leukemic Effects. Blood. 1965;25:179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathe G. Immunotherapy in leukemia. Experimental and clinical approaches. Ser Haematol. 1972;5:66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bortin MM, Truitt RL, Rimm AA, Bach FH. Graft-versus-leukaemia reactivity induced by alloimmunisation without augmentation of graft-versus-host reactivity. Nature. 1979;281:490. doi: 10.1038/281490a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss L, Morecki S, Vitetta ES, Slavin S. Suppression and elimination of BCL1 leukemia by allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Immunol. 1983;130:2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slavin S, Nagler A, Naparstek E, Kapelushnik Y, Aker M, Cividalli G, Varadi G, Kirschbaum M, Ackerstein A, Samuel S, Amar A, Brautbar C, Ben Tal O, Eldor A, Or R. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91:756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Champlin R, Khouri I, Shimoni A, Gajewski J, Kornblau S, Molldrem J, Ueno N, Giralt S, Anderlini P. Harnessing graft-versus-malignancy: non-myeloablative preparative regimens for allogeneic haematopoietic transplantation, an evolving strategy for adoptive immunotherapy. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, Sandmaier BM, Molina AJ, Maloney DG, Chauncey TR, Gooley TA, Hegenbart U, Nash RA, Radich J, Wagner JL, Minor S, Appelbaum FR, Bensinger WI, Bryant E, Flowers ME, Georges GE, Grumet FC, Kiem HP, Torok Storb B, Yu C, Blume KG, Storb RF. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood. 2001;97:3390. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.11.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiden PL, Flournoy N, Thomas ED, Prentice R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Storb R. Antileukemic effect of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of allogeneic-marrow grafts. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1068. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905103001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, Goldman JM, Kersey J, Kolb HJ, Rimm AA, Ringden O, Rozman C, Speck B, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75:555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Besien K, Champlin IK, McCarthy P. Allogeneic transplantation for low-grade lymphoma: long-term follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:702. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michallet M, Michallet AS, Le QH, Bandini G, Rowlings PA, Deeg HJ, Gahrton G, Montserrat E, Nicolini F, Rozman C, Gratwohl A, Niederwieser D, Bredeson CN, Horowitz MM (2003) Conventional HLA-identical sibling bone marrow transplantation is able to cure chronic lymphocytic leukemia. A study from the EBMT and IBMTR Registries. American Society of Hematology, San Diego: Blood.

- 17.Kolb HJ, Schattenberg A, Goldman JM, Hertenstein B, Jacobsen N, Arcese W, Ljungman P, Ferrant A, Verdonck L, Niederwieser D, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia effect of donor lymphocyte transfusions in marrow grafted patients. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Working Party Chronic Leukemia. Blood. 1995;86:2041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slavin S, Naparstek E, Nagler A, Ackerstein A, Samuel S, Kapelushnik J, Brautbar C, Or R. Allogeneic cell therapy with donor peripheral blood cells and recombinant human interleukin-2 to treat leukemia relapse after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1996;87:2195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peggs KS, Mackinnon S. Cellular therapy: donor lymphocyte infusion. Curr Opin Hematol. 2001;8:349. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolb HJ, Schmid C, Barrett AJ, Schendel DJ. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions in allogeneic chimeras. Blood. 2004;103:767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schetelig J, Thiede C, Bornhauser M, Schwerdtfeger R, Kiehl M, Beyer J, Sayer HG, Kroger N, Hensel M, Scheffold C, Held TK, Hoffken K, Ho AD, Kienast J, Neubauer A, Zander AR, Fauser AA, Ehninger G, Siegert W. Evidence of a graft-versus-leukemia effect in chronic lymphocytic leukemia after reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic stem-cell transplantation: the Cooperative German Transplant Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroger N, Schwerdtfeger R, Kiehl M, Sayer HG, Renges H, Zabelina T, Fehse B, Togel F, Wittkowsky G, Kuse R, Zander AR. Autologous stem cell transplantation followed by a dose-reduced allograft induces high complete remission rate in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100:755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maloney DG, Molina AJ, Sahebi F, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Sandmaier BM, Bensinger W, Storer B, Hegenbart U, Somlo G, Chauncey T, Bruno B, Appelbaum FR, Blume KG, Forman SJ, McSweeney P, Storb R. Allografting with nonmyeloablative conditioning following cytoreductive autografts for the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102:3447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khouri IF, Saliba RM, Giralt SA, Lee MS, Okoroji GJ, Hagemeister FB, Korbling M, Younes A, Ippoliti C, Gajewski JL, McLaughlin P, Anderlini P, Donato ML, Cabanillas FF, Champlin RE. Nonablative allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation as adoptive immunotherapy for indolent lymphoma: low incidence of toxicity, acute graft-versus-host disease, and treatment-related mortality. Blood. 2001;98:3595. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.13.3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faulkner RD, Craddock C, Byrne JL, Mahendra P, Haynes AP, Prentice HG, Potter M, Pagliuca A, Ho A, Devereux S, McQuaker G, Mufti G, Yin JL, Russell NH. BEAM-alemtuzumab reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for lymphoproliferative diseases: GVHD, toxicity, and survival in 65 patients. Blood. 2004;103:428. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold R, Massenkeil G, Bornhauser M, Ehninger G, Beelen DW, Fauser AA, Hegenbart U, Hertenstein B, Ho AD, Knauf W, Kolb HJ, Kolbe K, Sayer HG, Schwerdtfeger R, Wandt H, Hoelzer D. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation in adults with high-risk ALL may be effective in early but not in advanced disease. Leukemia. 2002;16:2423. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rhee F, Lin F, Cullis JO, Spencer A, Cross NC, Chase A, Garicochea B, Bungey J, Barrett J, Goldman JM. Relapse of chronic myeloid leukemia after allogeneic bone marrow transplant: the case for giving donor leukocyte transfusions before the onset of hematologic relapse. Blood. 1994;83:3377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marks DI, Lush R, Cavenagh J, Milligan DW, Schey S, Parker A, Clark FJ, Hunt L, Yin J, Fuller S, Vandenberghe E, Marsh J, Littlewood T, Smith GM, Culligan D, Hunter A, Chopra R, Davies A, Towlson K, Williams CD. The toxicity and efficacy of donor lymphocyte infusions given after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:3108. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreuzer KA, Schmidt CA, Schetelig J, Held TK, Thiede C, Ehninger G, Siegert W. Kinetics of stem cell engraftment and clearance of leukaemia cells after allogeneic stem cell transplantation with reduced intensity conditioning in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Eur J Haematol. 2002;69:7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2002.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritgen Blood. 2004;104:2600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mielcarek M, Leisenring W, Torok-Storb B, Storb R. Graft-versus-host disease and donor-directed hemagglutinin titers after ABO-mismatched related and unrelated marrow allografts: evidence for a graft-versus-plasma cell effect. Blood. 2000;96:1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JH, Choi SJ, Kim S, Seol M, Kwon SW, Park CJ, Chi HS, Lee JS, Kim WK, Lee KH. Changes of isoagglutinin titres after ABO-incompatible allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:702. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutis T, Gillespie G, Schrama E, Falkenburg JH, Moss P, Goulmy E. Tetrameric HLA class I-minor histocompatibility antigen peptide complexes demonstrate minor histocompatibility antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in patients with graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 1999;5:839. doi: 10.1038/10563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sayer HG, Kroger M, Beyer J, Kiehl M, Klein SA, Schaefer-Eckart K, Schwerdtfeger R, Siegert W, Runde V, Theuser C, Martin H, Schetelig J, Beelen DW, Fauser A, Kienast J, Hoffken K, Ehninger G, Bornhauser M. Reduced intensity conditioning for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: disease status by marrow blasts is the strongest prognostic factor. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;31:1089. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bornhauser M, Kiehl M, Siegert W, Schetelig J, Hertenstein B, Martin H, Schwerdtfeger R, Sayer HG, Runde V, Kroger N, Theuser C, Ehninger G. Dose-reduced conditioning for allografting in 44 patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia: a retrospective analysis. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:119. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallimore A, Glithero A, Godkin A, Tissot AC, Pluckthun A, Elliott T, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R. Induction and exhaustion of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes visualized using soluble tetrameric major histocompatibility complex class I-peptide complexes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1383. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee PP, Yee C, Savage PA, Fong L, Brockstedt D, Weber JS, Johnson D, Swetter S, Thompson J, Greenberg PD, Roederer M, Davis MM. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat Med. 1999;5:677. doi: 10.1038/9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corthay A, Lundin KU, Munthe LA, Froyland M, Gedde-Dahl T, Dembic Z, Bogen B. Immunotherapy in multiple myeloma: Id-specific strategies suggested by studies in animal models. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:759. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0504-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bogen B. Peripheral T cell tolerance as a tumor escape mechanism: deletion of CD4+ T cells specific for a monoclonal immunoglobulin idiotype secreted by a plasmacytoma. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2671. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao Blood. 2005;105:2300. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barrett AJ, Ringden O, Zhang MJ, Bashey A, Cahn JY, Cairo MS, Gale RP, Gratwohl A, Locatelli F, Martino R, Schultz KR, Tiberghien P. Effect of nucleated marrow cell dose on relapse and survival in identical twin bone marrow transplants for leukemia. Blood. 2000;95:3323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mackinnon S, Papadopoulos EB, Carabasi MH, Reich L, Collins NH, Boulad F, Castro-Malaspina H, Childs BH, Gillio AP, Kernan NA, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy evaluating escalating doses of donor leukocytes for relapse of chronic myeloid leukemia after bone marrow transplantation: separation of graft-versus-leukemia responses from graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1995;86:1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posthuma EF, Marijt EW, Barge RM, van Soest RA, Baas IO, Starrenburg CW, van Zelderen-Bhola SL, Fibbe WE, Smit WM, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Alpha-interferon with very-low-dose donor lymphocyte infusion for hematologic or cytogenetic relapse of chronic myeloid leukemia induces rapid and durable complete remissions and is associated with acceptable graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2004;10:204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmid C, Schleuning M, Aschan J, Ringden O, Hahn J, Holler E, Hegenbart U, Niederwieser D, Dugas M, Ledderose G, Kolb HJ. Low-dose ARAC, donor cells, and GM-CSF for treatment of recurrent acute myeloid leukemia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2004;18:1430. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vereecque R, Saudemont A, Quesnel B. Cytosine arabinoside induces costimulatory molecule expression in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2004;18:1223. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brouwer RE, van der Heiden P, Schreuder GM, Mulder A, Datema G, Anholts JD, Willemze R, Claas FH, Falkenburg JH. Loss or downregulation of HLA class I expression at the allelic level in acute leukemia is infrequent but functionally relevant, and can be restored by interferon. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:200. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderton SM, Wraith DC. Selection and fine-tuning of the autoimmune T-cell repertoire. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:487. doi: 10.1038/nri842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, Yang JC, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Sherry R, Restifo NP, Hubicki AM, Robinson MR, Raffeld M, Duray P, Seipp CA, Rogers-Freezer L, Morton KE, Mavroukakis SA, White DE, Rosenberg SA. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bethge WA, Hegenbart U, Stuart MJ, Storer BE, Maris MB, Flowers ME, Maloney DG, Chauncey T, Bruno B, Agura E, Forman SJ, Blume KG, Niederwieser D, Storb R, Sandmaier BM. Adoptive immunotherapy with donor lymphocyte infusions after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation following nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood. 2004;103:790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yee C, Thompson JA, Byrd D, Riddell SR, Roche P, Celis E, Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy using antigen-specific CD8+ T cell clones for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: in vivo persistence, migration, and antitumor effect of transferred T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242600099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ossendorp F, Eggers M, Neisig A, Ruppert T, Groettrup M, Sijts A, Mengede E, Kloetzel PM, Neefjes J, Koszinowski U, Melief C. A single residue exchange within a viral CTL epitope alters proteasome-mediated degradation resulting in lack of antigen presentation. Immunity. 1996;5:115. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaklamanis L, Gatter KC, Hill AB, Mortensen N, Harris AL, Krausa P, McMichael A, Bodmer JG, Bodmer WF. Loss of HLA class-I alleles, heavy chains and beta 2-microglobulin in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:379. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dermime S, Mavroudis D, Jiang YZ, Hensel N, Molldrem J, Barrett AJ. Immune escape from a graft-versus-leukemia effect may play a role in the relapse of myeloid leukemias following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:989. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brouwer RE, Hoefnagel J, BorgervanDer Burg B, Jedema I, Zwinderman KH, Starrenburg IC, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Barge RM, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Expression of co-stimulatory and adhesion molecules and chemokine or apoptosis receptors on acute myeloid leukaemia: high CD40 and CD11a expression correlates with poor prognosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;115:298. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacFarlane M, Harper N, Snowden RT, Dyer MJ, Barnett GA, Pringle JH, Cohen GM. Mechanisms of resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in primary B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Oncogene. 2002;21:6809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uno K, Inukai T, Kayagaki N, Goi K, Sato H, Nemoto A, Takahashi K, Kagami K, Yamaguchi N, Yagita H, Okumura K, Koyama-Okazaki T, Suzuki T, Sugita K, Nakazawa S. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) frequently induces apoptosis in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia cells. Blood. 2003;101:3658. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirano N, Takahashi T, Ohtake S, Hirashima K, Emi N, Saito K, Hirano M, Shinohara K, Takeuchi M, Taketazu F, Tsunoda S, Ogura M, Omine M, Saito T, Yazaki Y, Ueda R, Hirai H. Expression of costimulatory molecules in human leukemias. Leukemia. 1996;10:1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trentin L, Perin A, Siviero M, Piazza F, Facco M, Gurrieri C, Galvan S, Adami F, Agostini C, Pizzolo G, Zambello R, Semenzato G. B7 costimulatory molecules from malignant cells in patients with b-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders trigger t-cell proliferation. Cancer. 2000;89:1259. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000915)89:6<1259::AID-CNCR10>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choudhury A, Gajewski JL, Liang JC, Popat U, Claxton DF, Kliche KO, Andreeff M, Champlin RE. Use of leukemic dendritic cells for the generation of antileukemic cellular cytotoxicity against Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 1997;89:1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smit WM, Rijnbeek M, van Bergen CA, de Paus RA, Vervenne HA, van de Keur M, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. Generation of dendritic cells expressing bcr-abl from CD34-positive chronic myeloid leukemia precursor cells. Hum Immunol. 1997;53:216. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(96)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eibl B, Ebner S, Duba C, Bock G, Romani N, Erdel M, Gachter A, Niederwieser D, Schuler G. Dendritic cells generated from blood precursors of chronic myelogenous leukemia patients carry the Philadelphia translocation and can induce a CML-specific primary cytotoxic T-cell response. Gene Chromosome Canc. 1997;20:215. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2264(199711)20:3<215::AID-GCC1>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrison BD, Adams JA, Briggs M, Brereton ML, Yin JA. Stimulation of autologous proliferative and cytotoxic T-cell responses by “leukemic dendritic cells” derived from blast cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;97:2764. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.9.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Voutsadakis IA. NK cells in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2003;52:525. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0378-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goulmy E, Termijtelen A, Bradley BA, van Rood JJ. Alloimmunity to human H-Y. Lancet. 1976;2:1206. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)91727-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Voogt PJ, Fibbe WE, Marijt WA, Goulmy E, Veenhof WF, Hamilton M, Brand A, Zwann FE, Willemze R, van Rood JJ, et al. Rejection of bone-marrow graft by recipient-derived cytotoxic T lymphocytes against minor histocompatibility antigens. Lancet. 1990;335:131. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90003-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goulmy E, Gratama JW, Blokland E, Zwaan FE, van Rood JJ. A minor transplantation antigen detected by MHC-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes during graft-versus-host disease. Nature. 1983;302:159. doi: 10.1038/302159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.den Haan JM, Sherman NE, Blokland E, Huczko E, Koning F, Drijfhout JW, Skipper J, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH, et al. Identification of a graft versus host disease-associated human minor histocompatibility antigen. Science. 1995;268:1476. doi: 10.1126/science.7539551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang W, Meadows LR, den Haan JM, Sherman NE, Chen Y, Blokland E, Shabanowitz J, Agulnik AI, Hendrickson RC, Bishop CE, et al. Human H-Y: a male-specific histocompatibility antigen derived from the SMCY protein. Science. 1995;269:1588. doi: 10.1126/science.7667640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Skipper JC, Hendrickson RC, Gulden PH, Brichard V, Van Pel A, Chen Y, Shabanowitz J, Wolfel T, Slingluff CL, Jr., Boon T, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH. An HLA-A2-restricted tyrosinase antigen on melanoma cells results from posttranslational modification and suggests a novel pathway for processing of membrane proteins. J Exp Med. 1996;183:527. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.den Haan JM, Meadows LM, Wang W, Pool J, Blokland E, Bishop TL, Reinhardus C, Shabanowitz J, Offringa R, Hunt DF, Engelhard VH, Goulmy E. The minor histocompatibility antigen HA-1: a diallelic gene with a single amino acid polymorphism. Science. 1998;279:1054. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5353.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]