Abstract

Recombinant Semliki Forest virus (rSFV) enables high-level, transient expression of heterologous proteins in vivo, and is believed to be a superior vector for genetic vaccination, compared with the conventional DNA plasmid. Nonetheless, the efficacy of rSFV-based vaccine in eliciting human immune responses has not been tested. We used a Trimera mouse model, consisting of lethally irradiated BALB/c host reconstituted with nonobese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) bone marrow plus human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), to characterize the in vivo immune responses against rSFV-encoded human melanoma antigen MAGE-3. MAGE-3–specific antibody and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity were detected by ELISA and 51Cr-release assay, respectively, and the responses were compared with those induced by a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding the same antigen. The results showed that rSFV vaccine could elicit human MAGE-3–specific antibody and CTL response in the Trimera mice, and the antitumor responses were more potent than those by plasmid DNA vaccination. This is the first report to evaluate human immune responses to an rSFV-based tumor vaccine in the Trimera mouse model. Our data suggest that rSFV vector is better than DNA plasmid in inducing protective immunity, and the Trimera model may serve as a general tool to evaluate the efficacy of tumor vaccines in eliciting human primary immune response in vivo.

Keywords: MAGE-3, Semliki Forest virus, Trimera, Vaccine

Introduction

Nucleic acids encoding vaccine antigens, generally termed genetic vaccines, are attractive candidates in developing cancer vaccines because of their low cost and easy handling. In a number of model systems, genetic vaccines have shown strong immunogenicity and effectiveness in inducing protective immunity [8, 9, 22]. However, concerns over the biosafety of these vaccines have hampered their progress to clinical trial. Potential hazards include, but are not limited to, integration of foreign DNA into the host genome causing cell transformation, and development of anti-DNA antibodies due to the slow clearance of injected DNA from the body [24, 25].

Recently, self-replicating genetic vaccines have been developed using alphavirus Semliki Forest virus (SFV) as a vector, which have shown greater efficacy and safety than the conventional plasmid-based genetic vaccines [13, 20, 43]. Such vaccines are constructed into the genome of this single-stranded RNA virus, which drives its own replication, resulting in high-level transient expression of vaccine genes in transfected cells [14]. In addition, RNA replication of SFV is cytoplasmic, and combined with the modified split-helper system, the risk of chromosomal integration is greatly reduced [26]. Furthermore, because humans do not naturally come into contact with SFVs, SFV vectors are much less susceptible than other vectors using adenoviruses and vaccinia viruses, to the preexisting neutralizing antibodies that could decrease their clinical efficacy [45]. SFV vectors have been demonstrated to be successful in inducing humoral and cell-mediated immunity in several animal models [2, 3, 45, 46]. This strong protective efficiency, together with the above characteristics, makes SFV vectors likely candidates for development as a prototype vaccine vector.

Though SFV-based vaccines were proven to work well in animal models, no human vaccines with SFV vector have been evaluated up to now. Thus, a preclinical model to study the immunogenicity and efficacy of SFV-based vaccine would be helpful for the design of new vaccines to be tested in future clinical studies. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice due to a congenital lack of mature B and T cells can be engrafted with xenogeneic tissues such as human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [6]. These humanized mice (hu-PBL-SCID mice) have initially been developed as a model to evaluate the efficacy of antitumor drugs, as well as vaccinations, against a wide variety of tumors [27, 29]. However, there are severe limitations to this model in studying tumor vaccination. These include the lack of detectable antigen-specific proliferative or cytokine response of T cells recovered from hu-PBL-SCID mice due to limited engraftment of transferred human PBMCs, progressively restricted use of B- and T-cell repertoire, T-cell anergy, and the lack of professional T-cell costimulation in long-term chimera [15, 18, 38]. In 1994, Lubin and his colleagues developed an alternative protocol to generate a human/mouse chimera model, employing the transfer of human PBMCs into lethally irradiated BALB/c mice, together with radioprotection with SCID mouse bone marrow [21]. As these animals contain reconstituting tissues from SCID and humans, the mice were thus called Trimera [31]. With the preserved structures of murine lymphatic organs in lethally irradiated BALB/c mice, the engraftment of transferred human T and B cells reaches its peak within the first 2 or 3 weeks posttransplantation, evidenced by the formation of lymphoid follicles in peritoneum, lymph node, spleen, and so on. The rapid kinetics in structure-facilitated engraftment enables the generation of human antigen-specific B- and T-cell responses by vaccination in vivo [23, 36]. Thus, the Trimera mouse model seems likely to be one of the most suitable models to study new therapeutic vaccination approaches in preclinical trials. In the present study, we used this model to evaluate the efficacy of an SFV-based tumor vaccine targeting MAGE-3 antigen of human melanoma.

Materials and methods

Preparation of Trimera mice

Male nonobese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) and BALB/c (H-2d) mice, 6–10 weeks old at the onset of experiments, were purchased from the Institute of Animal in the Third Military Medical University (Chongqing, China). During the course of experiments, the mice were kept in pathogen-free animal facilities with controlled temperature and humidity, under a 12-h light/dark cycle, and with food and water containing cyprofloxacin (20 μg/ml). All animals were acclimated for at least 1 week before the experiments. Animal care and use were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Dutch Committee of Animal Experiments.

Recipient BALB/c mice received a lethal dose of total body irradiation according to the published methods [5, 21] with some modifications (i.e., day 0, 3.5 Gy; day 3, 9.5 Gy). On day 4–6, 3×106 mixed bone marrow cells (in 0.2 ml PBS) from NOD/SCID mice were transferred into each irradiated recipient by i.v. injection. One day after bone marrow infusion, each recipient mouse was injected (i.p.) with 2×108 human PBMCs (HLA-A2). All mice were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions, fed with sterile food and acid water containing ciprofloxacin (20 μg/ml).

Detection of reconstituted cells by FACS analysis

Leukocytes from peritoneum, spleen, peripheral blood, and lymph nodes were collected from a Ficoll gradient on the 14th day after transplantation of human lymphocytes. The cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry. For each sample, 1×106 cells were incubated with antihuman CD45-FITC, CD3-PerCP, CD4-PE, or CD8-FITC on ice for 30 min and washed with PBS. Cells were assayed with FACScan flow cytometer and data were analyzed with CellQuest software (Coulter).

Cell lines

Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21, from ATCC) were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s (DME) medium containing 100 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml of streptomycin, 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), and 10% tryptosol phosphate broth. LB373-MEL cell line (HLA-A2A11) and LB30-MEL cell line (HLA-A3A11), a generous gift from Dr M. Marchand (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Brussels Branch, Belgium), were cultured in IMDM containing penicillin (200 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml), supplemented with 10% FCS, L-arginine (116 μg/ml), L-asparagine (36 μg/ml), L-glutamine (219 μg/ml), and with the additives present in HITES medium, which are hydrocortisone (10 nM), insulin (5 μg/ml), transferrin (100 μg/ml), 17β-estradiol (10 nM), and sodium selenite (30 nM). All cell lines mentioned above were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere.

Preparation of recombinant plasmids and recombinant SFV

MAGE-3 cDNA was amplified from the LB373-MEL melanoma cell line by RT-PCR using the following primers: sense 5′-CGC TCG AGC CCG CCT GTT GCC CTG ACC A-3′; antisense 5′-GCT CTA GAC ACT ACT AAG AAT GCT GAC TGC TC-3′, which include XhoI and XbaI restriction sites at each end, respectively. Recombinant plasmid pCI-neo/MAGE-3 was constructed by inserting an XhoI/XbaI digested fragment of amplified MAGE-3 cDNA into the XhoI/XbaI digested pCI-neo vector (Promega). To construct pSMART2a/MAGE-3, MAGE-3 cDNA was also amplified from LB373-MEL melanoma cells by RT-PCR with different primers, as following: sense 5′-CCA TCG ATG CCC GCC TGT TGC CCT GAC CA-3′; antisense 5′-CGC CTA GGC ACT ACT AAG AAT GCT GAC TGC TC-3′, which include ClaI and AvrII restriction sites at each end, respectively. After ClaI/AvrII double digestion, MAGE-3 fragment was inserted into plasmid pSMART2a. The accuracy of amplified fragments was verified by sequencing. Endotoxin-free plasmids were produced with the Qiagen Giga plasmid preparation kits following the advice of the manufacture.

Recombinant SFV (rSFV) preparation was performed according to the published methods (see http://vsrp.uhnres.utoronto.ca/Bremner.html for a detailed method), with some modifications. Briefly, transfection of BHK cells (in 0.8 ml DMEM) with plasmids was carried out in a 0.4-cm cuvette (Bio-Rad) using the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser Plus at room temperature. The parameters were set at 960 μF, 0.4 kV, and 2 pulses were given with a delay of 2 sec between pulses. For co-electroporation of two plasmids, pSMART2a/MAGE-3 or pSMART2a/LacZ, and Helper plasmid were added in a 1:1.2 molar ratio (3 μg to 3.6 μg). After 4 h cultivation, the culture supernatant was aspirated, cells were washed with PBS, and 8 ml of IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS was added. Medium containing viral particles was collected 36 h after electroporation and then clarified three times by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. Virus particles were sedimented through a 20% (w/v) sucrose cushion (Beckman SW 28 rotor; 25,000 rpm for 1.5 h at 4°C). The virus pellets were resuspended in TNE buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA), filtered through a 0.22-μm membrane, and aliquots were frozen on dry ice and stored at −70°C until use. Before use, virus particles were activated in vitro with chymotrypsin, which renders them infectious by cleavage of the spike protein. To determine viral titer, BHK-21 cells were infected with serial dilutions of activated virus and monitored for expression of antigen by X-gal staining (for LacZ/SFV) or immunohistochemistry (for MAGE-3/SFV).

Detection of MAGE-3 expression by western blot

BHK-21 cells infected with MAGE-3/SFV or LacZ/SFV, or transfected (DOTAP, Roche) with pCI-neo/MAGE-3, pSMART2a/MAGE-3 or pCI-neo plasmids were lysed in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin. After lysis, cells were then sonicated and heated at 95°C for 5 min, followed by centrifugation to clear cell debris. The supernatants were analyzed by ECL Western blot using human MAGE-3–specific monoclonal antibody (57B), a generous gift from Dr Giulio Spagnoli (Institute of Basel Cancer Research, Swiss).

Vaccination and collection of sera and peritoneal cells

One day after human PBMC (HLA-A2) transfer, Trimera mice were immunized (i.p.) once with 100 μg recombinant plasmids or 106 infectious particles of activated rSFVs. Three weeks later, immunized Trimera mice were bled from the retro-orbital venous plexus to collect sera for antibody titer determination. Peritoneal cells were harvested by washing with 4 ml PBS supplemented with 1% sodium citrate and enriched by Ficoll density centrifugation for cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity assay.

ELISA detection of human IgG

Human IgG levels were assayed with direct ELISA. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates were coated with human MAGE-3 protein, purified with Ni-Sepharose 6B-CL resin (Qiagen, US) from overnight culture of BL21 (DE3) bacteria (Novagen) transformed with pET-16b/MAGE-3 plasmids (provided by Dr Giulio Spagnoli). Plate wells were blocked and washed. After incubation with sera from immunized mice, peroxidase-conjugated goat antihuman IgG was added and incubated for 30 min, and a color reaction was developed with the substrate phenylenediamine-dichloride (0.4 mg/ml) in PBS containing 0.012% hydrogen peroxide. The reaction was stopped within 15 min by adding 50 μl of 4 M H2SO4, and OD490 values were measured on an ELISA reader (Titertek Multiskan).

Cytotoxicity assay

Peritoneal cells from an individual mouse, 1.0×107/culture flask, were restimulated for 5 days in vitro with 10 μM of MAGE-3 CTL epitope peptide (FLWGPRALV, HLA-A2) [41] in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 5×10−5 M β-mercaptoethanol, 4 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 U/ml recombinant IL-2 (Sigma). On day 5, the restimulated cells were used as effectors in a CTL assay according to our previous method [47]. Briefly, 1×106 target LB373-MEL cells (HLA-A2A11) or haplotype control LB30-MEL cells (HLA-A3A11) were labeled with Na51CrO4 in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 plus 10% FCS for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The 51Cr-labeled cells were washed three times and plated in triplicate at a final concentration of 1×104 cells/well in 96-well V-bottom microtiter plates. Various concentrations of the effector cells were then added to the target cells in a total volume of 200 μl, and incubated for 4 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The released 51Cr from lysed target cells was measured by collecting 100 μl of supernatants and counting in an automated gamma counter. Specific cytotoxicity was calculated as the percentage of specific 51Cr release using the following formula:

|

Results

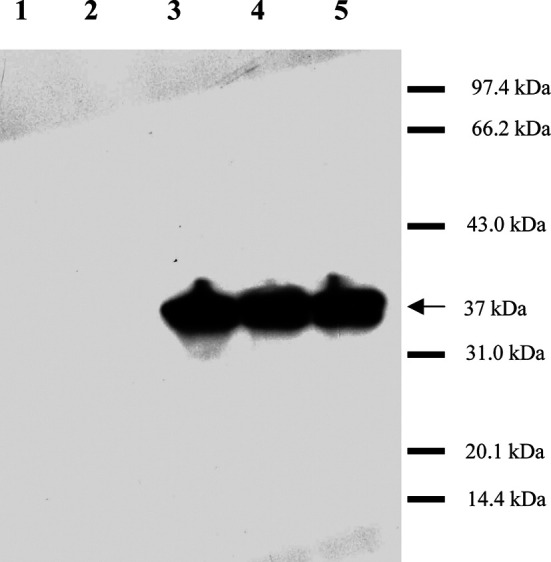

In vitro expression of MAGE-3 in transfected and infected BHK-21 cells

To confirm the expression of the candidate vaccines in mammalian cells, MAGE-3 protein from BHK-21 cells transfected with recombinant plasmids or infected with rSFVs was detected by monoclonal antibody in Western blot. As shown in Fig. 1, specific immunoreactive bands were detected in BHK-21 cells infected with MAGE-3/SFV (lane 3) or transfected with pSMART2a/MAGE-3 and pCI-neo/MAGE-3 (lanes 4 and 5), but not in cells infected with a control virus LacZ/SFV (lane 1) or in cells transfected with the vector pCI-neo (lane 2). These results indicated that infection with recombinant SFV could lead to the expression of MAGE-3 in mammalian cells.

Fig. 1.

MAGE-3 expression in BHK-21 cells. BHK-21 cells were transfected with recombinant plasmids or infected by rSFVs, respectively. After 18 h, harvested cells were lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, followed by sonication and heating at 95°C for 5 min. The processed samples were then separated on a 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel, and MAGE-3 expression was detected by ECL Western blot. Specific immunoreactive bands were identified in BHK-21 cells infected by MAGE-3/SFV (lane 3) or transfected with pSMART2a/MAGE-3 (lane 4) or pCI-neo/MAGE-3 (lane 5), but not in cells infected by a control virus LacZ/SFV (lane 1) or in cells transfected with the plasmid pCI-neo (lane 2). The apparent molecular weight of expressed MAGE-3 protein is indicated in the figure as 37 kDa. The proteins in the molecular weight ladder (Shanghai, China) were rabbit phosphorylase b (97.4 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66.2 kDa), rabbit actin (43.0 kDa), bovine carbonic anhydrase (31.0 kDa), trypsin inhibitor (20.1 kDa), and hen egg white lysozyme (14.4 kDa).

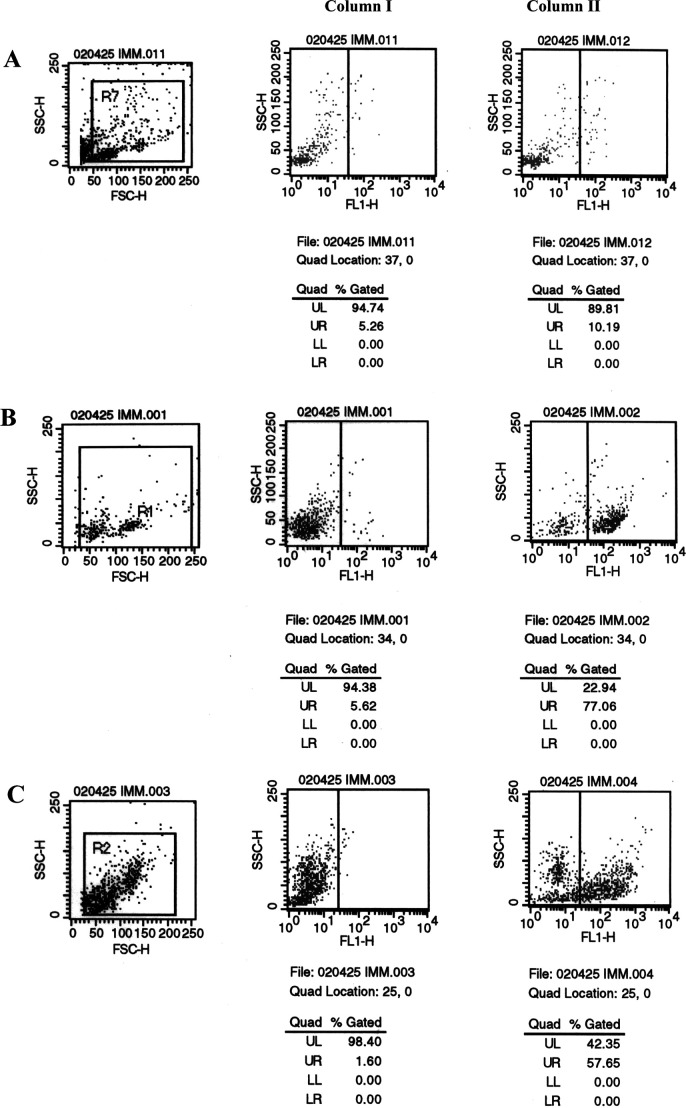

Engraftment of human PBMCs in Trimera mice

The engraftment of human PBMCs in the peritoneum, spleen, peripheral blood, and lymph nodes of Trimera mice has been observed [4, 21, 37]. Successful engraftment can be evaluated by FACS analysis of lymphocyte subpopulations in the Trimera mice. Lubin et al. [21] have shown that maximal levels of engraftment are attained 2–3 weeks after transplantation of human PBMCs into the conditioned recipient BALB/c mice. Thus, we collected cells from peritoneum, spleen, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood for analyzing the presence of human lymphocytes in Trimera mice 2 weeks after reconstitution. In accordance with previous reports, our results showed that engrafted human CD45-positive cells in peritoneum were above 70%, whereas those in spleen and lymph nodes were above 50 and 20%, respectively. In the peripheral blood, the engraftment of human leukocytes was about 5–8% (Fig. 2). These results indicated that human PBMCs have been successfully engrafted in the Trimera mice.

Fig. 2.

Phenotypic characterization of leukocytes from reconstituted Trimera mice. Trimera mice were prepared by lethal split radiation followed by radioprotection with NOD/SCID bone marrow and subsequent transplantation of human PBMCs. Two weeks later, total leukocytes from the peritoneum, spleen, peripheral blood, and lymph nodes of the Trimera mice were harvested for FACS analysis with antihuman CD45-FITC. a Leukocytes from control irradiated BALB/c mice with NOD/SCID BM protection but receiving no human PBMCs. b–e Leukocytes from peritoneum, spleen, peripheral blood, and lymph nodes of Trimera, respectively. Column series I staining control, standard FACS assay procedure with the omission of CD45 antibody.Column series II standard FACS assay with anti-CD45-FITC.

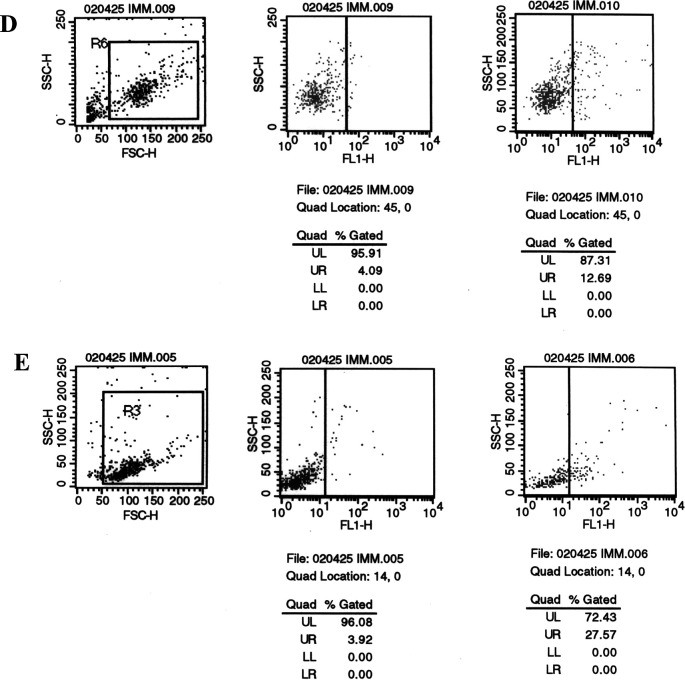

It is well established that T-cell–mediated immune responses play a pivotal role in antitumor immunity elicited by various vaccines. Particularly, killing of target tumor cells is dependent on the CD8-positive cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), and increasing evidence has implicated the importance of CD4-positive T cells in the initiation of antitumor immune responses. Thus, we further determined the subpopulations of engrafted T lymphocytes in the Trimera mice by three-color FACS analysis with CD4-FITC, CD8-PE, and CD3-PECY5. As shown in Fig. 3, in the peritoneum of Trimera mice, engrafted human CD3+ cells were 11.7%, among which the majority were CD3+CD4+ cells (10.9%) with few CD3+CD8+ cells (about 1.1%). Probably due to the homing difficulty, presence of such cells in peripheral blood could hardly be detected. This observation is consistent with the previous reports [21, 40], indicating the cellular basis for the potential human immune responses against tumor to be elicited in the Trimera mice.

Fig. 3.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of human T-cell subsets from the Trimera mice. Reconstitution of irradiated BLAB/c mice with human PBMCs is described in “Materials and methods.” On the day 14 after human PBMC transplantation, leukocytes from the peritoneum (a) and peripheral blood (b) of the Trimera mice were harvested for triple-staining with anti-CD4-FITC, CD8-PE, and CD3-PECY5 in FACS analysis.

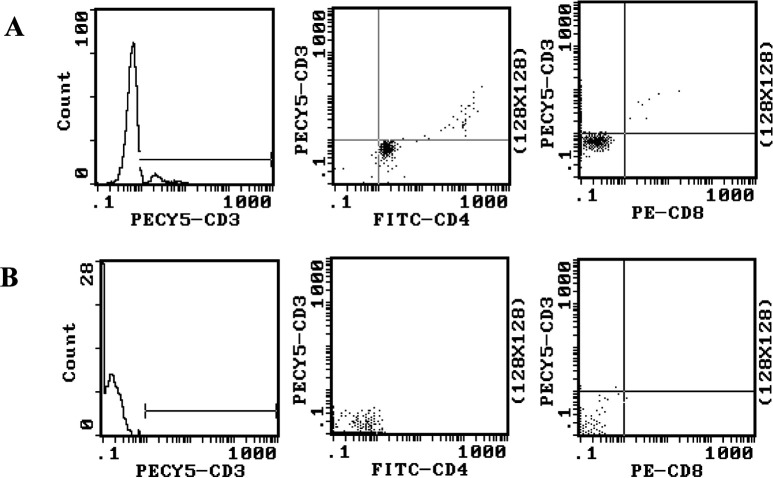

Detection of MAGE-specific antibody

Although the role of antibody in antitumor effect is inconsistent in the literature [7, 30], human anti-sera and mAbs reactive to tumors have been isolated [30]. Thus, we decided to examine the titers of MAGE-3–specific antibody elicited by vaccines against MAGE-3 in the Trimera mice by ELISA 21 days after immunization. Our results showed that immunization with MAGE-3/SFV, pSMART2a/MAGE-3 (based on SFV replicon), and pCI-neo/MAGE-3 (conventional DNA vaccine) could significantly elicit the production of MAGE-3–specific antibody, compared with control groups immunized with LacZ/SFV, pSMART2a, pCI-neo and saline (Fig. 4). Among MAGE-3 vaccines, mice immunized with MAGE-3/SFV produced higher titers of specific antibody (maximum 1:512) than those with pSMART2a/MAGE-3 and pCI-neo/MAGE-3 (maximum 1:256 and 1:128, respectively). Interestingly, about twofold higher titers were induced by SFV replicon-bearing pSMART2a/MAGE-3 plasmid than the conventional DNA plasmid pCI-neo/MAGE-3 under the same conditions, supporting a role of self-replication for higher efficiency of DNA vaccines. However, a strong humoral response to tumor antigens may not correlate to strong resistance of the host to the tumors. Thus, we next determined the CTL responses in vaccine-immunized Trimera mice with 4 h 51Cr-release assay.

Fig. 4.

Antibody production from the Trimera mice inoculated with various vaccines against MAGE-3. On the 21st day after immunization, sera were collected from the Trimera mice (five mice/group), and the titers of MAGE-3–specific antibody were determined with direct ELISA. The sera from the Trimera mice immunized with MAGE-3–targetted vaccines (i.e., MAGE-3/SFV, pSMART2a/MAGE-3, and pCI-neo/MAGE-3) were serially diluted, whereas those from the mice immunized with lacZ/SFV, pCI-neo, pSMART2a and saline were directly used as negative controls. When the ELISA OD490 reading of a serum sample is 2.1-fold higher than the mean value of those from the four negative control groups, the dilution fold of the serum was taken as its antibody titer.

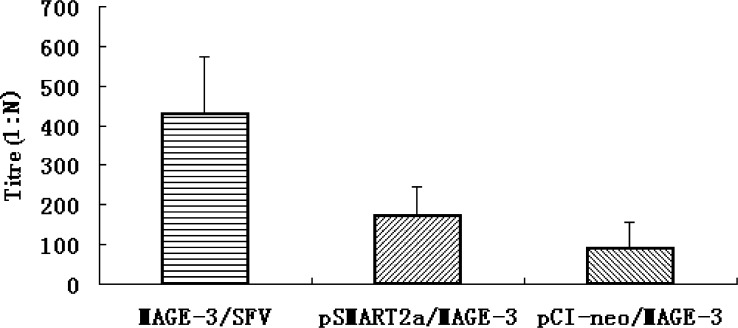

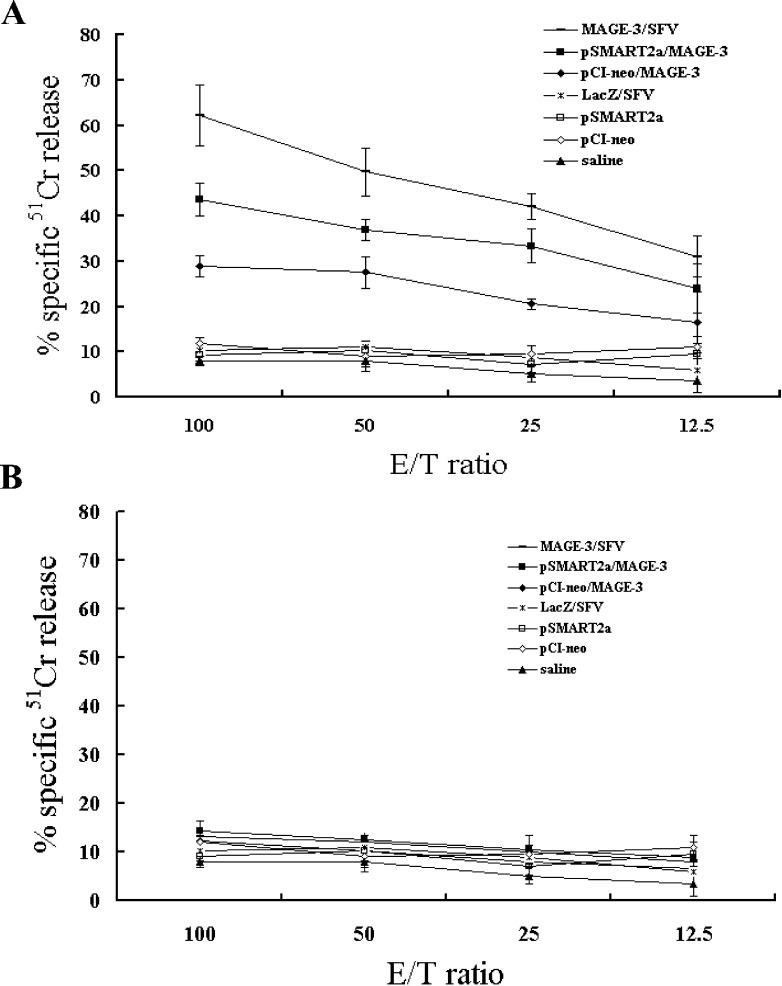

Characterization of MAGE-3-specific CTL activity ex vivo

Peritoneal cells were collected from the Trimera mice 21 days after immunizations and restimulated in vitro with MAGE-3 epitope peptides FLWGPRALV and hIL-2 for 5 days. Of the seven groups, immunizations with MAGE-3/SFV, pSMART2a/MAGE-3, and pCI-neo/MAGE-3 were able to induce MAGE-3–specific CTLs that lysed MAGE-3–expressing LB373-MEL cells, whose HLA haplotype matches with that of the effector cells, at various ratios of effector cells to target cells (E/T). As shown in Fig. 5a, at the E/T ratio of 100:1, approximately 62% of LB373-MEL melanoma cells were lysed by the unfractionated but restimulated peritoneal cells from MAGE-3/SFV–immunized Trimera mice, while only 45% and 30% of LB373-MEL cells were lysed by the peritoneal cells from Trimera mice immunized with pSMART2a/MAGE-3 and pCI-neo/MAGE-3. The high E/T ratio required probably reflects the low percentage of engrafted human T cells, particularly CD8+ T cells, in the Trimera mice. Nonetheless, at the same E/T ratio, no detectable CTL activity was seen over the assay background in the cases of immunization with LacZ/SFV, pSMART2a, pCI-neo, or saline. To determine whether the CTL activity is HLA haplotype restricted, we used MAGE-3–expressing LB30-MEL cells as control target cells, which have a different HLA haplotype (HLA-A3A11). As shown in Fig. 5b, no specific cytotoxicity of effectors could be detected in any experimental group, confirming that the CTL activity in Trimera model was also HLA haplotype restricted. The above results also strongly suggest that compared with conventional DNA vaccines, such as pCI-neo/MAGE-3, MAGE-3/SFV is much better able to stimulate CTL response to specifically kill the tumor cells in this humanized animal model.

Fig. 5.

Specific cytotoxicity against HLA-matched target cells by in vitro restimulated peritoneal cells from vaccinated Trimera. Peritoneal cells collected from the Trimera mice (five mice/group) after 3 weeks of immunizations were restimulated with MAGE-3 epitope peptides and hIL-2 for 5 days in vitro and used as effector cells. LB373-MEL cells (HLA-A2A11) expressing MAGE-3 were used as target cells (a) and LB30-MEL (HLA-A3A11) expressing MAGE-3 were used as haplotype control target cells (b). Four-hour 51Cr-release assays were performed to test the cytotoxic activities against target cells at various E/T ratios.

Disscusion

The human MAGE-3 gene that encodes a tumor antigen was originally discovered in melanoma cells, and has been reported to be expressed in various types of tumors, including lung cancer, breast cancer, esophageal cancer, melanoma, and gastrointestinal carcinoma, but not in normal tissues except testis or placenta [12, 16, 34]. Though testis and placenta can express MAGE-3 gene, these tissue cells do not express MHC class I molecules, thus cannot present MAGE peptides on their surface. Therefore, immunotherapy targeting MAGE-3 could avoid undesired outcomes such as autoimmune pathology. During this decade, there were several reports of successful induction of HLA class I–restricted antitumor CTLs using MAGE-3 peptide-pulsed DC vaccines. Some clinical trials with these vaccines were reported to be effective for certain patients with malignant melanoma [32, 39], bladder cancer [28], and gastrointestinal carcinoma [35]. However, autologous dendritic cells had to be generated ex vivo by laborious protocols to isolate such cells from PBMCs. In addition, they had to be pulsed with various types of MAGE-3 peptides, depending on the patient’s HLA haplotype. Thus, developing a new vaccination strategy, such as genetic vaccination targeting MAGE-3, is of high clinical importance.

Because of the low cost and easiness to manipulate, vaccination with plasmid DNA is an attractive strategy for the development of cancer vaccines. The efficacy of DNA vaccination has been shown in numerous models and is being optimized by many laboratories. On the other hand, alphavirus vectors, particularly those constructed with the replicon of SFV, have shown great potential as gene delivery vehicles for various applications in cancer gene therapy [1, 44]. The rapid production of high-titer recombinant SFV particles with impressive transduction rates in various mammalian cell lines, primary cultures, and in vivo tissues results in high levels of transgene expression [14, 26]. In addition, immunization with replication-deficient SFV vaccines has been efficacious in inducing antibodies and CTLs directly against the encoded foreign antigen [10, 11]. Such deficient SFV lacks the genes coding for viral structural proteins and thus can only undergo a single round of nonproductive replication [10, 11]. Based on these characteristics, tumor vaccine approaches have been taken by injecting SFV vectors as naked RNA molecules [42] or recombinant viron particles [33] for both therapeutic and prophylactic purposes. However, the immunogenicity and efficacy of SFV-based human tumor vaccines in humanized animal models remain to be determined.

To tackle this issue, we used the Trimera mouse model to test the efficacy of SFV-based tumor vaccine against MAGE-3, a CT (cancer-testis) antigen from human melanoma [21, 27, 31]. FACS analysis of leukocytes from the peritoneum, spleen, lymph nodes, and blood of the Trimera mice indicated that the engraftment of human PBMCs was successful. Such a humanized mouse model enabled us to determine the primary humoral and CTL responses of the human immune cells in the Trimera mice immunized with various vaccines. The results showed that vaccines targeting MAGE-3 could elicit MAGE-3–specific antibody and CTL responses endowed by the transferred human PBMCs. It has been shown that both humoral and cellular immunity are required for antitumor activities against existing tumors [17, 19]. As demonstrated in this work, tumor vaccines could activate both arms of adaptive immunity in the Trimera model, so this model can also serve as a general tool to evaluate in vivo primary antitumor immune responses induced by tumor vaccines.

Furthermore, we demonstrated that SFV-mediated MAGE-3 vaccination was more potent than plasmid DNA vaccination, such as immunization with pCI-neo/MAGE-3, in the induction of both antibody production and specific CTL cytotoxicity. In addition, compared with conventional plasmid vaccines (e.g., pCI-neo/MAGE-3), DNA vaccines incorporated with SFV replicon (e.g., pSMART2a/MAGE-3) could also have a stronger capacity of eliciting antitumor humoral and CTL responses. These results suggest that SFV or DNA vaccines equipped with SFV replicon might be more suitable than the conventional DNA vaccines to induce antitumor immunity in the preclinical animal model. Whether it is also true in humans awaits strict well-controlled clinical tests.

Due to the high mortality of the host in the Trimera model (about 50% death rate), testing the long-term in vivo antitumor effect of vaccines becomes difficult. Such high mortality may relate to irradiation-caused illness and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). One way to solve these problems is to reconstitute human hematopoietic stem cells into immune-deficient mice. During the course of hematopoiesis, human immune cells will be “educated” to tolerize the mouse host. In April 2004, Traggiai and colleagues reported transplantation of human cord blood CD34+ cells introhepatically (i.h.) into Rag−/−γc−/− mice that strictly lack T, B, and NK cells [40]. The chimeras successfully de novo developed human B, T, and dendritic cells, formed primary and secondary lymphoid organs, and produced functional immune responses. No death of experimental animals was reported in this study. Furthermore, human CD45+ cells could be detected at least 26 weeks after transplantation of human cells. However, due to the developmental course of human hematopoietic cells in the chimeras, large numbers of human CD45+ cells only appeared 4–5 weeks postreconstitution. Thus, this model will be suitable for evaluating the long-term in vivo antitumor immunity for tumor vaccines, especially the memory responses after rechallenge of tumor cells. On the other hand, the Trimera model will be useful for testing primary immune responses elicited by vaccines, as the transferred PBMCs are mainly mature lymphocytes. It would be desirable in the future to evaluate the SFV-based MAGE-3 vaccines in the tumor-bearing, human immune system reconstituted Rag−/−γc−/− mice to investigate the antitumor efficacy in vivo and further verify the ex vivo antitumor effects obtained from the Trimera model.

Acknowledgements

We heartedly thank Dr David P. DiCiommo and Dr Rod Bremner (Cellular and Molecular Division, Toronto Western Research Institute, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5T 2S8) for providing the rSFV vectors system. This work was supported by National Key Basic Research Program of China (2001CB510001).

Abbrevations

- BM

Bone marrow

- CTL

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- E/T

Effector number/target number

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- hIL-2

Human interleukin-2

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- NOD/SCID

Non-obese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency

- PBL

Peripheral blood lymphocyte

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- SFV

Semliki Forest virus

References

- 1.Asselin-Paturel C, Lassau N, Guinebretiere JM, et al. Transfer of the murine interleukin-12 gene in vivo by a Semliki Forest virus vector induces B16 tumor regression through inhibition of tumor blood vessel formation monitored by Doppler ultrasonography. Gene Ther. 1999;6:606–615. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berglund P, Smerdou C, Fleeton MN, Tubulekas I, Liljestrom P. Enhancing immune responses using suicidal DNA vaccines. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:562–565. doi: 10.1038/nbt0698-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berglund P, Fleeton MN, Smerdou C, Liljestrom P. Immunization with recombinant Semliki Forest virus induces protection against influenza challenge in mice. Vaccine. 1999;17:497–507. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bocher WO, Marcus H, Shakarchy R, et al. Antigen-specific B and T cells in human/mouse radiation chimera following immunization in vivo. Immunology. 1999;96:634–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00704.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bocher WO, Dekel B, Schwerin W, et al. Induction of strong hepatitis B virus (HBV) specific T helper cell and cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses by therapeutic vaccination in the trimera mouse model of chronic HBV infection. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2071–2079. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2071::AID-IMMU2071>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosma GC, Custer RP, Bosma MJ. A severe combined immunodeficiency mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1983;301:527–530. doi: 10.1038/301527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JP, Klitzman JM, Hellstrom I, Nowinski RC, Hellstrom KE. Antibody response of mice to chemically induced tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:955–958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.2.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciernik IF, Berzofsky JA, Carbone DP. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and antitumor immunity with DNA vaccines expressing single T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1996;156:2369–2375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curcio C, Di Carlo E, Clynes R, et al. Nonredundant roles of antibody, cytokines, and perforin in the eradication of established Her-2/neu carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1161–1170. doi: 10.1172/JCI200317426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daemen T, Pries F, Bungener L, et al. Genetic immunization against cervical carcinoma: induction of cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity with a recombinant alphavirus vector expressing human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1859–1866. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daemen T, Riezebos-Brilman A, Bungener L, et al. Eradication of established HPV16-transformed tumours after immunisation with recombinant Semliki Forest virus expressing a fusion protein of E6 and E7. Vaccine. 2003;21:1082–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer C, Gudat F, Stulz P, et al. High expression of MAGE-3 protein in squamous-cell lung carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:1119–1121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970611)71:6<1119::AID-IJC34>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleeton MN, Liljestrom P, Sheahan BJ, Atkins GJ. Recombinant Semliki Forest virus particles expressing louping ill virus antigens induce a better protective response than plasmid-based DNA vaccines or an inactivated whole particle vaccine. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:749–758. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-3-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frolov I, Schlesinger S. Comparison of the effects of Sindbis virus and Sindbis virus replicons on host cell protein synthesis and cytopathogenicity in BHK cells. J Virol. 1994;68:1721–1727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1721-1727.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia S, Dadaglio G, Gougeon ML. Limits of the human-PBL-SCID mice model: severe restriction of the V beta T-cell repertoire of engrafted human T cells. Blood. 1997;89:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaugler B, Van den Eynde EB, van der Bruggen BP, et al. Human gene MAGE-3 codes for an antigen recognized on a melanoma by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:921–930. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes RM. Strategies for cancer gene therapy. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85:28–35. doi: 10.1002/jso.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ifversen P, Martensson C, Danielsson L, et al. Induction of primary antigen-specific immune reponses in SCID-hu-PBL by coupled T-B epitopes. Immunology. 1995;84:111–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroki M, Shibaguchi H, Imakiire T, et al. Immunotherapy and gene therapy of cancer using antibodies or their genes against tumor-associated antigens. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4377–4381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liljestrom P, Garoff H. A new generation of animal cell expression vectors based on the Semliki Forest virus replicon. Biotechnology (N Y) 1991;9:1356–1361. doi: 10.1038/nbt1291-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lubin I, Segall H, Marcus H, et al. Engraftment of human peripheral blood lymphocytes in normal strains of mice. Blood. 1994;83:2368–2381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Y, O’Hagan D, Zhou H, et al. Plasmid DNA encoding human carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) adsorbed onto cationic microparticles induces protective immunity against colon cancer in CEA-transgenic mice. Vaccine. 2003;21:1938–1947. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00821-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus H, David M, Canaan A, et al. Human/mouse radiation chimera are capable of mounting a human primary humoral response. Blood. 1995;86:398–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin T, Parker SE, Hedstrom R, et al. Plasmid DNA malaria vaccine: the potential for genomic integration after intramuscular injection. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:759–768. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mor G, Singla M, Steinberg AD, et al. Do DNA vaccines induce autoimmune disease? Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:293–300. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.3-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris-Downes MM, Phenix KV, Smyth J, et al. Semliki Forest virus-based vaccines: persistence, distribution and pathological analysis in two animal systems. Vaccine. 2001;19:1978–1988. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00428-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB. Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature. 1988;335:256–259. doi: 10.1038/335256a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishiyama T, Tachibana M, Horiguchi Y, et al. Immunotherapy of bladder cancer using autologous dendritic cells pulsed with human lymphocyte antigen-A24-specific MAGE-3 peptide. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nonoyama S, Smith FO, Ochs HD. Specific antibody production to a recall or a neoantigen by SCID mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:3894–3901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Real FX, Mattes MJ, Houghton AN, et al. Class 1 (unique) tumor antigens of human melanoma: identification of a 90,000 dalton cell surface glycoprotein by autologous antibody. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1219–1233. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.4.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reisner Y, Dagan S. The Trimera mouse: generating human monoclonal antibodies and an animal model for human diseases. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:242–246. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(98)01203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds SR, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Shapiro RL, et al. Vaccine-induced CD8+ T-cell responses to MAGE-3 correlate with clinical outcome in patients with melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:657–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roks AJ, Henning RH, Buikema H, et al. Recombinant Semliki Forest virus as a vector system for fast and selective in vivo gene delivery into balloon-injured rat aorta. Gene Ther. 2002;9:95–101. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russo V, Traversari C, Verrecchia A, et al. Expression of the MAGE gene family in primary and metastatic human breast cancer: implications for tumor antigen-specific immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:216–221. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadanaga N, Nagashima H, Mashino K, et al. Dendritic cell vaccination with MAGE peptide is a novel therapeutic approach for gastrointestinal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2277–2284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Segall H, Lubin I, Marcus H, Canaan A, Reisner Y. Generation of primary antigen-specific human cytotoxic T lymphocytes in human/mouse radiation chimera. Blood. 1996;88:721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smyth MJ, Kershaw MH, Trapani JA. Xenospecific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: potent lysis in vitro and in vivo. Transplantation. 1997;63:1171–1178. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV, Schols D, Roncarolo MG, Saxon A. Anti-SCID mouse reactivity shapes the human CD4+ T cell repertoire in hu-PBL-SCID chimeras. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1817–1827. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thurner B, Haendle I, Roder C, et al. Vaccination with mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Traggiai E, Chicha L, Mazzucchelli L, et al. Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice. Science. 2004;304:104–107. doi: 10.1126/science.1093933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Bruggen P, Bastin J, Gajewski T, et al. A peptide encoded by human gene MAGE-3 and presented by HLA-A2 induces cytolytic T lymphocytes that recognize tumor cells expressing MAGE-3. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3038–3043. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vignuzzi M, Gerbaud S, van der Werf S, Escriou N. Naked RNA immunization with replicons derived from poliovirus and Semliki Forest virus genomes for the generation of a cytotoxic T cell response against the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:1737–1747. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-7-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiong C, Levis R, Shen P, et al. Sindbis virus: an efficient, broad host range vector for gene expression in animal cells. Science. 1989;243:1188–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.2922607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamanaka R, Zullo SA, Ramsey J, et al. Induction of therapeutic antitumor antiangiogenesis by intratumoral injection of genetically engineered endostatin-producing Semliki Forest virus. Cancer Gene Ther. 2001;8:796–802. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou X, Berglund P, Rhodes G, et al. Self-replicating Semliki Forest virus RNA as recombinant vaccine. Vaccine. 1994;12:1510–1514. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(94)90074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou X, Berglund P, Zhao H, Liljestrom P, Jondal M. Generation of cytotoxic and humoral immune responses by nonreplicative recombinant Semliki Forest virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3009–3013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu B, Chen Z, Cheng X, et al. Identification of HLA-A*0201-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope from TRAG-3 antigen. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1850–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]