Abstract

Hepadnaviruses are DNA viruses that replicate through reverse transcription of an RNA pregenome. Viral DNA synthesis takes place inside viral nucleocapsids, formed by core protein dimers. Previous studies have identified carboxy-terminal truncations of the core protein that affect viral DNA maturation. Here, we describe the effect of small amino-terminal insertions into the duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) core protein on viral DNA replication. All insertion mutants formed replication-competent nucleocapsids. Elongation of viral DNA, however, appeared to be incomplete. Increasing the number of additional amino acids and introducing negatively charged residues further reduced the observed size of mature viral DNA species. Mutant core proteins did not inhibit the viral polymerase. Instead, viral DNA synthesis destabilized mutant nucleocapsids, rendering mature viral DNA selectively sensitive to nuclease action. Interestingly, the phenotype of two previously described carboxy-terminal DHBV core protein deletion mutants was found to be based on the same mechanism. These data suggest that (i) the amino- as well as the carboxy-terminal portion of the DHBV core protein plays a critical role in nucleocapsid stabilization, and (ii) the hepadnavirus polymerase can perform partial second-strand DNA synthesis in the absence of intact viral nucleocapsids.

Hepadnaviruses are small enveloped DNA viruses with a narrow host range and a relative tropism for the liver. The most extensively studied members of this viral family include the hepatitis B virus (HBV), the woodchuck hepatitis virus, and the duck hepatitis B virus (DHBV) (7, 17, 25). Hepadnaviruses have a unique replication strategy that involves reverse transcription of a pregenomic RNA intermediate (21, 26). During virus assembly, pregenomic viral RNA and the viral polymerase protein are copackaged into an icosahedral capsid shell, which is formed by core protein dimers. Within the nucleocapsid, the viral polymerase converts viral RNA into minus-strand DNA. Minus-strand DNA is the template for synthesis of complementary plus-strand DNA. Since elongation starts close to the 5′ end of minus-strand DNA and switches to the 3′ end of the template, a noncovalently closed-circular DNA molecule is generated (9, 11, 19, 22).

The HBV core protein consists of 183 amino acids. It is able to self-assemble via dimeric intermediates into spherical shells (32). Recently the molecular structure of the HBV nucleocapsid has been resolved by cryoelectron microscopy (3, 5, 6). The DHBV core protein consists of 262 residues and forms nucleocapsids of a three-dimensional structure similar to that of HBV (14). The carboxy-terminal region of hepadnaviral core proteins is strikingly rich in arginine residues. This region has been shown to play an essential role in both packaging of pregenomic RNA and viral DNA maturation (1, 2, 8, 10, 18, 20, 31). The amino-terminal region of the HBV core protein is believed to be an integral part of the particle assembly domain, since mutants bearing small N-terminal deletions fail to form nucleocapsids (15).

Here we report that small N-terminal insertions into the DHBV core protein appear to affect viral DNA maturation similar to the previously described phenotype of C-terminally truncated DHBV core proteins (31). This effect, however, is not due to incomplete plus-strand DNA elongation. Rather, second-strand DNA elongation progressively destabilizes mutant nucleocapsids formed by N-terminally extended or C-terminally truncated core proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs.

Wild-type DHBV core protein was expressed from plasmid pTC-Dcore, in which transcription of the core open reading frame (ORF) is driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter. The core protein mutants analyzed in this study are derived from the expression vector N64, which contains 64 amino acids of the bacterial LacZ protein at the N terminus of the core reading frame. Both plasmids have been described in detail previously (28, 29). Clone 25N and clone 6N were constructed by removing the 123-bp EcoRV-PvuI fragment or the 174-bp EcoRV-Ban31 fragment from expression vector N64. Mutants containing shorter insertions were constructed by ligating PCR-generated fragments into the EcoRV and NsiI restriction site of plasmid pTC-Dcore. Clone 17N is a mutant which carries the coding sequence of the myc epitope. This mutant was constructed by ligating a double-stranded oligonucleotide into the NotI restriction site of the vector sequence and the XbaI site at the N terminus of the core ORF. The construct pST75ClaSph− is a head-to-tail dimer coding for all elements necessary for DHBV replication except for the viral core protein (28).

Transfection, purification of viral DNA, and Southern blot analysis.

The chicken hepatoma cell line LMH was transfected by the calcium phosphate method (4, 13). In a typical cotransfection experiment, 10 μg of core expression plasmid and 10 μg of core-deficient DHBV head-to-tail dimer construct were transfected into a 10-cm-diameter dish containing 5 ml of culture medium. Three days after transfection, the cells were trypsinized and resuspended in 500 μl of an isotonic buffer (140 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0]) containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40. Cell nuclei were removed by centrifugation for 5 min at 1,000 × g, and the supernatants were cleared from cell debris by centrifugation for another 5 min at 14,000 × g. To remove plasmid DNA, the lysates were treated with 50 U of micrococcal nuclease (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 for 2 h at 37°C. After proteinase K digestion, viral DNA was purified by adsorption to silica columns (QuiaAmp tissue kit; Quiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. RNase A digestion was included to remove cellular as well as viral RNA. In some experiments, purified DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme DpnI. This enzyme selectively cleaves transfected methylated DNA, but does not affect newly synthesized viral DNA. Nucleic acids were separated by electrophoresis through 1% agarose gels, transferred onto nylon membranes (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England), and hybridized with a DHBV-specific, 32P-labeled DNA probe.

Endogenous polymerase assay.

Viral core particles were purified from cytoplasmic extracts by immunoprecipitation with a polyclonal rabbit antibody directed against DHBV core protein (a kind gift from H.-J. Schlicht). The precipitate was incubated with 10 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol), dATP, dGTP, and dTTP (final concentration, 10 μM each) in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NH4Cl, 40 mM MgCl2, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 0.3% β-mercaptoethanol for 2 h at 37°C. Nonlabeled dCTP was added to a final concentration of 10 μM, and the samples were incubated for another 12 h at 37°C. Subsequently, some aliquots were treated with micrococcal nuclease. Viral DNA was purified as described above, separated on a 1% agarose gel, transferred to a blotting membrane, and analyzed by autoradiography.

RESULTS

DHBV core proteins bearing small N-terminal insertions allow for nucleocapsid formation and synthesis of apparently immature viral DNA.

A series of DHBV core protein mutants were constructed that contained short N-terminal insertions at position 2 or 3 of the core ORF (Fig. 1). Expression of the respective gene products was verified by Western blot analysis (data not shown). The modified core proteins were tested for their ability to support viral replication in a transcomplementation assay. LMH cells were cotransfected with expression vectors coding for the respective modified core proteins and a head-to-tail dimer construct of the DHBV genome, which is deficient for core protein synthesis. A standard protocol involving treatment of cytoplasmic extracts with micrococcal nuclease to remove contaminating plasmid DNA before purification of DNA and Southern blotting was used.

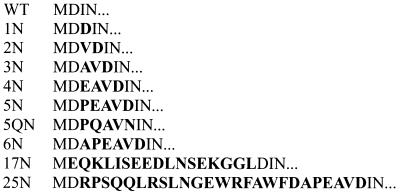

FIG. 1.

Nomenclature and amino acid sequences of mutant DHBV core proteins. WT, wild-type core protein; 1N to 25N, mutated core proteins. Insertions are depicted in boldface letters.

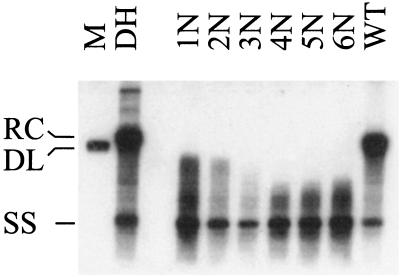

As shown in Fig. 2, all mutants supported the production of replicative intermediates. Hence, these mutants allow for the formation of viral nucleocapsids. In this experimental setting, minus-strand DNA and nascent plus-strand DNA were detectable (Fig. 2). The presence of partially elongated plus-strand DNA was confirmed by hybridization with strand-specific, 32P-labeled oligodeoxyribonucleotides (data not shown). Surprisingly, relaxed-circular DNA, a hallmark of DHBV replication in naturally infected as well as transfected cells, was totally absent in the mutant nucleocapsids.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of viral DNA generated in mutant nucleocapsids. Nucleocapsid-associated viral DNA was isolated from cotransfected LMH cells after treatment with micrococcal nuclease. DH, viral DNA isolated from infected primary duck hepatocytes; 1N to 6N, modified core proteins (for nomenclature, see Fig. 1); WT, wild-type core protein; RC, relaxed-circular DNA; DL, double-stranded linear DNA; SS, single-stranded DNA; M, 3.0-kbp linear DHBV monomer.

The apparent defect in viral DNA maturation correlates with the size and negative charge of the insertion.

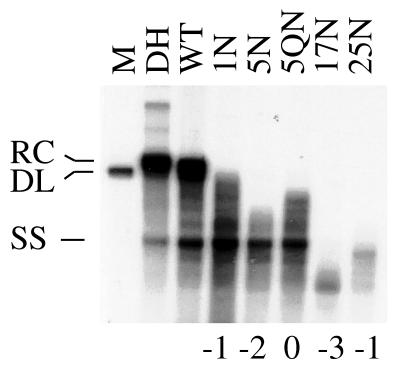

To evaluate a potential size effect of the insertions on DNA maturation, mutants bearing 1, 5, 17, or 25 additional residues were analyzed as described above. As shown in Fig. 3, the single-residue mutant allowed plus-strand DNA elongation to proceed close to relaxed-circular DNA. In contrast, plus-strand DNA synthesis was more severely affected by the 5N mutant and was virtually absent in the case of the 17N and 25N mutants. Thus, the apparent defect in DNA maturation correlates with the size of the respective insertion.

FIG. 3.

Apparent effect of size and charge of N-terminal insertions on viral DNA maturation. Results from Southern blot analysis are presented. Cytoplasmic extracts were treated with micrococcal nuclease prior to isolation of nucleocapsid-associated DNA. For nomenclature, see Fig. 1. The net charge of the respective insertion is indicated at the bottom. RC, relaxed-circular DNA; DL, double-stranded linear DNA; SS, single-stranded DNA; M, 3.0-kbp linear DHBV monomer.

Next, the potential influence of the insertion’s charge was analyzed. All of the insertion mutants tested in the previous experiments contain glutamic and aspartic acid residues. To determine whether acidic amino acids are essential to inhibit viral DNA maturation, a five-residue mutant was created in which glutamic acid and aspartic acid were substituted by glutamine and asparagine (mutant 5QN). While deficient for synthesis of relaxed-circular DNA, this mutant produced more mature plus-strand DNA than its original counterpart (Fig. 3, lanes 5N and 5QN). Thus, the overall negative charge of the insertion seems to contribute to the observed effect. This notion also explains why the effect of the 17N mutant, which carries three additional negative charges, is more pronounced than that of mutant 25N, which adds only one additional negative charge to the core protein.

Maturation of viral DNA induces destabilization of mutant core particles.

We addressed the issue of why relaxed-circular DNA was missing in all mutant core particles tested. One possible explanation would be an inhibition of the viral polymerase by the additional N-terminal residues. To test this hypothesis, endogenous polymerase assays were performed. In this cell-free assay system, viral core particles are purified, and viral polymerase activity is then determined by incorporation of labeled and nonlabeled deoxynucleoside triphosphates.

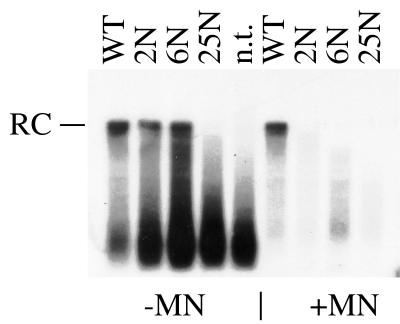

Surprisingly, mutants 2N and 6N were able to generate relaxed-circular DNA under these experimental conditions (Fig. 4, left panel). These findings demonstrate that the respective mutants did not inhibit the viral polymerase. Rather, both mutants allowed for complete DNA maturation in a cell-free system, while a strikingly different result was obtained by Southern blot analysis of transfected cells (Fig. 2 and 3).

FIG. 4.

Endogenous polymerase activity in mutant nucleocapsids. Core particles were prepared from cotransfected LMH cells and incubated with radiolabeled nucleotides. Aliquots were processed directly (−MN) or after incubation with micrococcal nuclease (+MN). n.t., nontransfected LMH cells. For the nomenclature of the respective mutants, see Fig. 1. RC, relaxed-circular DNA.

To account for the divergent results obtained in the respective assay systems, the potential role of nuclease digestion was evaluated. In contrast to the standard Southern blot protocol used in the previous experiments (Fig. 2 and 3), our endogenous polymerase assay did not include micrococcal nuclease treatment. We therefore tested whether the relaxed-circular DNA generated by the mutants in the endogenous polymerase assay was sensitive to nuclease. To this end, the samples were treated with micrococcal nuclease prior to preparation of viral DNA. Indeed, full-length DHBV DNA generated by mutants 2N and 6N disappeared upon treatment with micrococcal nuclease (Fig. 4, right panel).

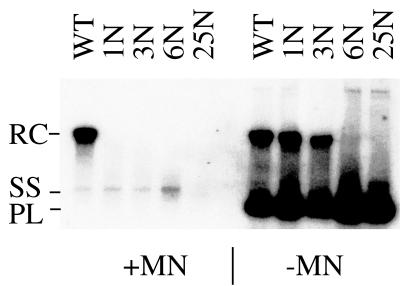

Conversely, omission of nuclease digestion in the Southern blotting protocol revealed the presence of relaxed-circular DNA in the case of mutants 1N and 3N (Fig. 5, right panel) as well as 2N (data not shown). In the same cytoplasmic extracts, both plasmid and relaxed-circular DNA disappeared when the cytoplasm was incubated with micrococcal nuclease (Fig. 5, left panel), thus confirming our previous results.

FIG. 5.

Effect of micrococcal nuclease digestion on the phenotype of N-terminally extended DHBV core proteins. Results from Southern blot analysis are presented. +MN, cytoplasmic extracts from cotransfected LMH cells treated with micrococcal nuclease prior to extraction of nucleocapsid-associated viral DNA. −MN, omission of micrococcal nuclease treatment. Instead of micrococcal nuclease, purified DNA samples were treated with the restriction enzyme DpnI, which selectively cuts methylated, transfected plasmid DNA but not the nonmethylated viral DNA. For the nomenclature of the respective mutants, see Fig. 1. WT, wild-type core protein; RC, relaxed-circular DNA; SS, single-stranded DNA; PL, DpnI fragment of transfected plasmid DNA.

Taken together, these data indicate that the synthesis of relaxed-circular DNA destabilizes nucleocapsids formed by core protein mutants that carry small N-terminal insertions. In the case of mutant 6N, relaxed-circular DNA was clearly visible in the endogenous polymerase assay but hardly detectable by Southern blotting. Mutant 25N failed to produce relaxed-circular DNA in both assays (Fig. 4 and 5, respectively). Earlier nucleocapsid destabilization or additional size effects on viral DNA synthesis might account for these observations.

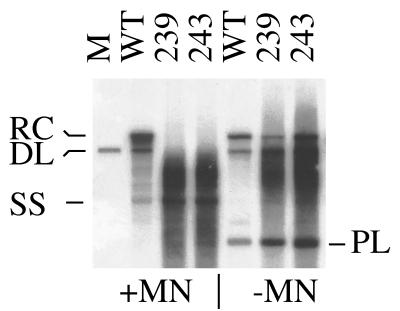

C-terminally truncated DHBV core proteins allow for the formation of fully mature, but nuclease-sensitive viral DNA.

A previous study of carboxy-terminally truncated DHBV core proteins has described effects on DNA maturation (31) strikingly similar to the phenotypes of our N-terminal insertion mutants. We tested the possibility that these effects are also due to nucleocapsid disintegration. Two previously characterized class II mutants (31), lacking about half of the arginine-rich C terminus, were analyzed by Southern blotting. Indeed, omission of nuclease treatment in the DNA purification protocol revealed the presence of relaxed-circular and double-stranded linear DNA (Fig. 6, right panel). Conversely, inclusion of the nuclease treatment step selectively destroyed fully mature viral DNA, yielding immature DNA intermediates as published before (31) (Fig. 6, left panel).

FIG. 6.

Effect of micrococcal nuclease digestion on the phenotype of C-terminally truncated DHBV core proteins. Results from Southern blot analysis are presented. For methods, see the legend to Fig. 5. +MN, treatment with micrococcal nuclease, but no DpnI digestion. −MN, no micrococcal nuclease treatment, but digestion with DpnI. WT, wild-type DHBV core protein; 239 and 243, C-terminally truncated core mutants according to Yu and Summers (31); RC, relaxed-circular DNA; DL, double-stranded linear DNA; SS, single-stranded DNA. Single-stranded DNA was visible on the right panel (−MN) upon longer exposure (not shown). PL, DpnI fragment of transfected plasmid DNA. M, 3.0-kbp linear DHBV monomer.

DISCUSSION

Here we have shown that mutant DHBV core proteins carrying small insertions at the amino terminus generate nucleocapsids, which support early steps of DNA synthesis but are destabilized upon formation of relaxed-circular DNA, rendering this DNA species sensitive to nuclease action. Increasing the number of added residues and introducing negative charges yields more pronounced defects of DNA maturation, possibly as a result of earlier nucleocapsid destabilization. Posttranslational modifications of mutant core proteins, such as phosphorylation, might contribute to this process. The concept of nucleocapsid disintegration would also explain our observation that plus strands of discrete sizes did not accumulate to a detectable level. Rather, mature forms of viral DNA were virtually absent after nuclease digestion. Our data are in agreement with previous studies mapping a domain that is essential for nucleocapsid formation to the N terminus of the HBV core protein (15). Extending this concept, we have identified mutations that still support nucleocapsid formation but affect the stability of particles harboring nascent DNA.

In addition, our data shed new light on the long-standing concept that the arginine-rich C-terminal domain of the DHBV core protein is specifically required for DNA maturation. It has been suggested that viral DNA elongation might be inhibited in nucleocapsids consisting of C-terminally truncated core proteins (31). In contrast, our results indicate that the phenotype of two of these mutants is mediated by premature capsid disintegration similar to that of the N-terminal-insertion mutants. The fact that nuclease treatment was used to remove plasmid DNA prior to extraction of nucleocapsid-associated viral DNA in the respective study (31) provides an explanation of why fully mature DNA forms have not been observed earlier. It will be interesting to investigate whether similar observations in the HBV system (1, 18) are due to the same mechanism. Other reports have proposed that modifications of the C-terminal domain could play an important role in viral uncoating (12, 24). Our data are compatible with this notion and suggest that viral DNA maturation might represent another important driving force in hepadnaviral nucleocapsid disassembly.

The precise mechanism of mutant nucleocapsid disintegration is unclear at present. Electron cryomicroscopy studies have shown that HBV core protein mutants bearing a C-terminal truncation (6) or a small N-terminal elongation (3a) generate wild-type like nucleocapsids in bacteria. By analogy, it seems reasonable to assume that a correct DHBV core structure is made first. Second-strand DNA elongation might then trigger structural changes that destabilize mutant nucleocapsids either directly or via an enhanced sensitivity to proteases. It remains to be elucidated, however, whether mutant capsids completely disrupt and become physically separate from the DNA-polymerase complex or whether mutant core proteins remain attached to the complex.

The observation that nuclease-sensitive mature viral DNA can be produced in our experimental system also has implications for the activity of the hepadnavirus polymerase. While partial minus-strand DNA synthesis has been accomplished with the HBV and DHBV polymerases, respectively, in the absence of core proteins (16, 23, 27, 30), it is generally believed that priming of second-strand DNA synthesis and elongation of plus-strand DNA can take place only within intact nucleocapsids. We provide evidence that second-strand elongation can at least partially be completed even in the absence of intact nucleocapsids. In this process, cellular polymerases seem to be dispensable, since plus-strand DNA was elongated in both transfected cells as well as in the endogenous polymerase assay.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (We 1365/2-1).

We thank H.-J. Schlicht for providing antibodies against DHBV core protein, J. Summers for providing expression vectors coding for C-terminally truncated DHBV core mutants, B. Böttcher for sharing unpublished results, and M. Nassal for helpful discussions. The expert technical assistance of Christine Möcklin is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beames B, Lanford R E. Carboxy-terminal truncations of the HBV core protein affect capsid formation and the apparent size of encapsidated HBV RNA. Virology. 1993;194:597–607. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birnbaum F, Nassal M. Hepatitis B virus nucleocapsid assembly: primary structure requirements in the core protein. J Virol. 1990;64:3319–3330. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3319-3330.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Böttcher B, Wynne S A, Crowther R A. Determination of the fold of the core protein of hepatitis B virus by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 1997;386:88–91. doi: 10.1038/386088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Böttcher, B. Unpublished data.

- 4.Condreay L D, Aldrich C E, Coates L, Mason W S, Wu T-T. Efficient duck hepatitis B virus production by an avian liver tumor cell line. J Virol. 1990;64:3249–3258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3249-3258.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conway J F, Cheng N, Zlotnick A, Wingfield P T, Stahl S J, Steven A C. Visualization of a 4-helix bundle in the hepatitis B virus capsid by cryo-electron microscopy. Nature. 1997;386:91–94. doi: 10.1038/386091a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowther R A, Kiselev N A, Böttcher B, Berriman J A, Borisova G P, Ose V, Pumpens P. Three-dimensional structure of hepatitis B virus core particles determined by electron cryomicroscopy. Cell. 1994;77:943–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dane D S, Cameron C H, Briggs M. Virus-like particles in serum of patients with Australia-antigen-associated hepatitis. Lancet. 1970;i:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)90926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallina A, Bonelli F, Zentilin L, Rindi G, Muttini M, Milanesi G. A recombinant hepatitis B core antigen polypeptide with the protamine-like domain deleted self-assembles into capsid particles but fails to bind nucleic acids. J Virol. 1989;63:4645–4652. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.11.4645-4652.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganem D, Varmus H E. The molecular biology of hepatitis B viruses. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:651–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.003251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatton T, Zhou S, Standring D N. RNA- and DNA-binding activities in hepatitis B virus capsid protein: a model for their roles in viral replication. J Virol. 1992;66:5232–5241. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5232-5241.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havert M B, Loeb D D. cis-Acting sequences in addition to donor and acceptor sites are required for template switching during synthesis of plus-strand DNA for duck hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 1997;71:5336–5344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5336-5344.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kann, M., X. Lu, and W. H. Gerlich. 1995. Recent studies on replication of hepatitis B virus. J. Hepatol. 22(Suppl. 1):9–13. [PubMed]

- 13.Kawaguchi T, Nomura K, Hirayama Y, Kitagawa T. Establishment and characterization of a chicken hepatocellular carcinoma cell line, LMH. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4460–4464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenney J M, von Bonsdorff C H, Nassal M, Fuller S D. Evolutionary conservation in the hepatitis B virus core structure: comparison of human and duck cores. Structure. 1995;3:1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khudyakov Y E, Kalinina T I, Neplyueva V S, Gazina E V, Kadoshnikov Y P, Bogdanova S L, Smirnov V D. The effect of the structure of the terminal regions of the hepatitis B virus gene C polypeptide on the formation of core antigen (HBcAg) particles. Biomed Sci. 1991;2:257–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanford R E, Notvall L, Beames B. Nucleotide priming and reverse transcriptase activity of hepatitis B virus polymerase expressed in insect cells. J Virol. 1995;69:4431–4439. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4431-4439.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mason W S, Seal G, Summers J. Virus of Pekin ducks with structural and biological relatedness to human hepatitis B virus. J Virol. 1980;36:829–836. doi: 10.1128/jvi.36.3.829-836.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nassal M. The arginine-rich domain of the hepatitis B virus core protein is required for pregenome encapsidation and productive viral positive-strand DNA synthesis but not for virus assembly. J Virol. 1992;66:4107–4116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4107-4116.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nassal M, Schaller H. Hepatitis B virus replication. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:221–228. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90136-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlicht H-J, Bartenschlager R, Schaller H. The duck hepatitis B virus core protein contains a highly phosphorylated C terminus that is essential for replication but not for RNA packaging. J Virol. 1989;63:2995–3000. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.7.2995-3000.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeger C, Ganem D, Varmus H E. Biochemical and genetic evidence for the hepatitis B virus replication strategy. Science. 1986;232:477–484. doi: 10.1126/science.3961490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seeger C, Hu J. Why are hepadnaviruses DNA and not RNA viruses? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:447–450. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)01141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seifer M, Standring D N. Recombinant human hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase is active in the absence of the nucleocapsid or the viral replication origin, DR1. J Virol. 1993;67:4513–4520. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4513-4520.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seifer M, Standring D N. A protease-sensitive hinge linking the two domains of the hepatitis B virus core protein is exposed on the viral capsid surface. J Virol. 1994;68:5548–5555. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5548-5555.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Summers J, Smolec J M, Snyder R. A virus similar to human hepatitis B virus associated with hepatitis and hepatoma in woodchucks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4533–4537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summers J, Mason W S. Replication of the genome of a hepatitis B-like virus by reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. Cell. 1982;29:403–415. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tavis J E, Ganem D. Expression of functional hepatitis B virus polymerase in yeast reveals it to be the sole viral protein required for correct initiation of reverse transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4107–4111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Weizsäcker F, Wieland S, Blum H E. Identification of two separable modules in the duck hepatitis B virus core protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2704–2707. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2704-2707.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Weizsäcker F, Wieland S, Blum H E. Inhibition of viral replication by genetically engineered mutants of the duck hepatitis B virus core protein. Hepatology. 1996;24:294–299. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang G H, Seeger C. The reverse transcriptase of hepatitis B virus acts as a protein primer for viral DNA synthesis. Cell. 1992;71:663–670. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu M, Summers J. A domain of the hepadnavirus capsid protein is specifically required for DNA maturation and virus assembly. J Virol. 1991;65:2511–2517. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2511-2517.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou S, Standring D N. Hepatitis B virus capsid particles are assembled from core-protein dimer precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10046–10050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]