Abstract

Purpose

The mechanism by which bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) mediates antitumor activity has not been clearly established. Specific cytokines in the urine after BCG intravesical instillation therapy may serve as a prognostic factor of treatment response. In this study, various urinary cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-2, IL-6, IL-8. IL-10, IL-12, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were measured.

Materials and methods

In total 20 patients were treated with BCG intravesical instillation therapy for carcinoma in situ of the bladder . At the completion of the first and eighth instillations, spontaneously voided urine specimens were collected before BCG instillation, every 2 h until 12 h, and thereafter until 24 h. All specimens were ultrafiltrated using an ADVANTEC UK-10 membrane. The cytokines were measured using ELISA and RIA techniques.

Results

Significantly higher levels of IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were detected in the eighth instillation as compared to the first instillation (p<0.001). After BCG intravesical instillation therapy, treatment failure occurred in 6 of the 20 patients (30%), including primary failure (persistence of CIS) in 3, and de novo failure (tumor recurrence) in 3 with a median follow-up of 46.9 months. Significantly higher production of IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α was observed in the responder group than in the non-responder group (p<0.05). Multivariate analysis revealed IL-2 as an independent prognostic cytokine of responder status.

Conclusions

This study indicates that urinary IL-2 at the eighth instillation of BCG may serve as a valuable prognostic factor of treatment efficacy as well as tumor recurrence after treatment.

Keywords: BCG, Cytokines, Bladder cancer, IL-2, Prognosis

Introduction

Since the initial report of Morales et al. [21] bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) intravesical instillation therapy has been considered an effective treatment for carcinoma in situ (CIS) of the bladder in some patients . Immunotherapy with BCG has resulted in complete tumor regression in more than 70% of treated patients with CIS [19]. However, serious adverse effects including death have also been reported [20]. To date, we are unable to predict individuals who will not respond to BCG intravesical instillation therapy. If a method was available to discriminate patients who respond to the treatment from those who do not, we could avoid a dangerous challenge to non-responders. Accumulating evidence suggests that cytokines including IL-1α/β, IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α, TNF-β, and IFN-γ are secreted in the urine following instillation of BCG [2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14, 15, 23, 26]. In particular, specific cytokines, such as IL-2 or IL-8, have shown a prognostic value for tumor recurrence, although the clinical relevance of such cytokines is still debated [5, 8, 16, 25, 28, 29]. Therefore, we measured IL- 1β, IL- 2, IL- 6, IL- 8, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, and undertook to identify the most important cytokines for the prediction of antitumor response and/or tumor recurrence after BCG intravesical instillation therapy.

Materials and methods

Patient collective

Between April 1996 and September 2001, 20 patients (11 men and 9 women) who had carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder were treated with BCG intravesical instillation therapy at the Department of Urology, Yamaguchi University Hospital. The mean age with standard deviation was 66.1±8.5 years (range 47–83 years). Of the 20 patients, primary CIS, secondary CIS, and concurrent CIS were noted in 4, 11, and 5 cases, respectively. Of the 11 with secondary CIS, 4 patients had undergone nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract cancer and 7 transurethral resection for superficial bladder cancer. A total of 5 patients had concurrent solitary superficial transitional cell carcinoma that was treated with transurethral resection before the initiation of BCG therapy. Pathological stages were pTa, pT1a, and pT1b in 1, 2, and 2 cases, respectively (Table 1). All patients underwent selected-site mucosal biopsies that were taken from the lateral sites of both ureteral orifices, trigone, retrotrigone, dome, anterior wall, posterior wall, and bladder neck. An additional biopsy specimen was taken from the posterior urethra in males. The pathological diagnosis was made from these specimens according to the WHO criteria. So-called severe dysplasia was also included in the CIS category in this study. As a preliminary experiment, voided urine specimens from 5 healthy volunteers were collected to study if urinary cytokine was expressed in the healthy cohorts. In addition eight patients with acute cystitis were selected as a control group, and voided urine was collected to evaluate the effect of inflammation on cytokine expression. The mean age of the 8 patients with acute cystitis was 67.6±5.7 years (range 56–73 years).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 20 patients

| Detail | Value |

|---|---|

| No. men/No.women | 11/9 |

| Patient age (mean±SD) | 66.1±8.5 years |

| Median follow-up months (range) | 46.9 (6–69) months |

| CIS type | (No. pts.) |

| Primary | 4 |

| Secondary | 11 |

| Bladder cancer | 7 |

| Upper urinary tract cancer | 4 |

| Concurrent | 5 |

| pTa | 1 |

| pT1a | 2 |

| pT1b | 2 |

BCG intravesical instillation therapy

All patients underwent cystoscopic examination to confirm the healing status of the biopsy and/or transurethral resection site 4 weeks after biopsy and/or resection. Thereafter each patient was treated with 8 consecutive weekly instillations of 80 mg BCG (Tokyo 172 strain) suspended in 40 ml physiological saline through a 12 Fr. catheter. As a rule, patients were restricted from voiding for 2 h after instillation. If more than 10 cells/hpf of leukocytes and/or erythrocytes were found in the urinalysis, the BCG instillation was postponed to the next week. At the first and eighth instillations of BCG, all patients were admitted to hospital for 1 day, and total volumes of urine were collected for 24 h.

Urine processing

Spontaneously voided urine specimens were collected before instillation of BCG, and 2–4, 4–6, 6–8, 8–10, 10–12 and 12–24 h thereafter. In the first 10 cases, specimens were immediately centrifuged at 400g and 4°C for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 3,500g and 4°C for 10 min to remove cellular fragments and debris. After adjustment to pH 7.2 with sodium hydroxide, the supernatants were ultrafiltrated using an ADVANTEC UK-10 membrane (Toyo Roshi, Tokyo) which has an exclusion limit of 10 kDa. In another 10 cases, specimens were immediately frozen at −20°C and afterwards thawed at 4°C, followed by centrifugation and ultrafiltration as described above. The mean frozen period was 10.4 months ranging from 1 to 23.9 months. The specimens were stored at −20°C in aliquots until analysis.

Measurement of cytokines

A total of 8 cytokines, namely IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were measured. IL-8, IL-10 and IL-12 were measured using a quantitative sandwich enzyme technique using a Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The minimum measurable limit of each cytokine was 31.2 pg/ml for IL-8, 7.8 pg/ml for IL-10 and IL-12. IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were measured using an ELISA technique, and IL-2 was measured using a radioimmuno assay. The minimum measurable limit of each cytokine was 20 pg/ml for IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and 50 pg/ml for IL-2.

Patient outcome

All patients had selected-site mucosal biopsies 1 month after the last instillation to evaluate the response. "Responder" status was defined as the condition of having both negative CIS on pathology and negative urine cytology. All patients were followed by cystoscopic examinations and cytological evaluations using both voided urine and washing solution during cystoscopic examinations every 3 months during the initial 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. When the cytology turned out to be positive or any abnormality of the bladder mucosa was found in the cystoscopic examination, selected-site mucosal biopsies were done to confirm the pathological diagnosis. "Non-responder" status was defined as persistence of CIS after treatment or histological confirmation of the tumor during the follow-up period. The median follow-up of the responders was 46.9 months (range 6–69 months).

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney U-test was applied to evaluate differences in urinary cytokine values between the first and eighth instillations of BCG, between responders and non-responders, and between the BCG and UTI groups. P-values of less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. To assess the independent prognostic cytokines for the responders, a Cox's proportional hazard model was applied for the multivariate analysis.

Results

Cytokine values in the control and pretreatment

All cytokines except for IL-2 were detected in the urine of the control group. In contrast, no cytokines were detectable in the healthy volunteers or pretreatment patient group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cytokine production in the urine (ng/ml)

| Cytokine | Healthy volunteers | Patient group | Control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-BCG treatment | UTI | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| IL–1β | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.154 | 0.387 |

| IL–2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| IL–6 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.299 | 0.264 |

| IL–8 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.429 | 0.311 |

| IL–10 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| IL–12 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| IFN–γ | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.005 |

| TNF–α | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.006 |

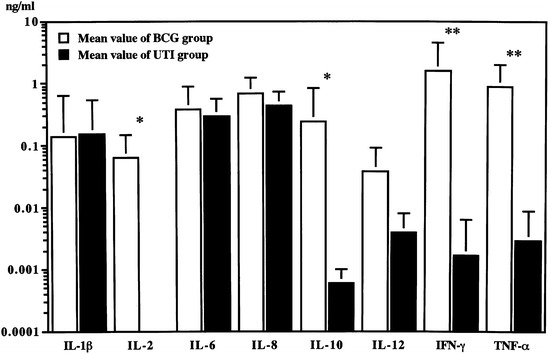

Comparison of peak values of each cytokine between BCG group and control group

Figure 1 shows a comparison of peak values of cytokines in the eighth instillation of BCG and those in the control group. The peak values of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12 did not differ between the BCG and control groups. Significantly higher values of IL-2, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-10 were observed in the BCG group than in the control group.

Fig. 1.

. Comparison of peak values of urinary cytokines between eighth instillation and control group. The urinary IL-2 value was significantly higher than the control group (5.91±9.90 ng/ml vs. 0 ng/ml p<0.01). Bars represent values plus standard deviation (SD), *p<0.01, **p<0.001. Y axis is scaled in logarythmic order

Comparison of each cytokine product between the first and eighth instillation

Table 3 shows the induction of each cytokine during the 24 -hour period after the first and eighth instillation of BCG. Significantly higher levels of IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α were detected in the eighth instillation as compared to the first (p<0.001). The peak value of each cytokine varied, namely 2 h (IL-12), 4 h (IL-2, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) or 6 h (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) after the eighth instillation (data were not shown).

Table 3. .

Cytokine production in the urine of patients during 24 h after instillation of BCG (ng/day)

| 1st Instillation | 8th Instillation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-Value | |

| IL–1β | 2.14 | 3.29 | 23.38 | 61.64 | 0.347 |

| IL–2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.52 | 11.75 | <0.001 |

| IL–6 | 5.62 | 10.63 | 100.04 | 107.31 | <0.001 |

| IL–8 | 22.93 | 26.87 | 222.27 | 144.64 | <0.001 |

| IL–10 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 115.77 | 191.46 | <0.001 |

| IL–12 | 2.17 | 3.88 | 11.12 | 18.90 | 0.185 |

| IFN–γ | 2.80 | 4.42 | 488.27 | 774.17 | <0.001 |

| TNF–α | 0.05 | 0.14 | 134.11 | 179.10 | <0.001 |

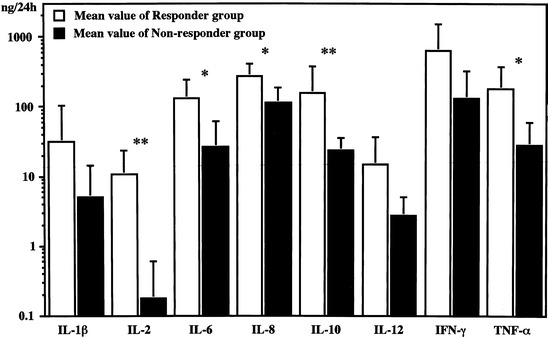

Comparison of each cytokine production between the responder and non-responder groups

After BCG intravesical instillation therapy, treatment failure occurred in 6 out of the 20 patients (30%), including primary failure (persistence of CIS) in 3, and de novo failure (tumor recurrence) in 3 with a median follow-up of 46.9 months. The mean time to recurrence was 12.7 months ranging from 9 to 16 months. Figure 2 depicts a comparison of each cytokine production between the responder and non-responder groups. Significantly higher production of IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α was observed in the former as compared to the latter group. IL-1β, IFN-γ, and IL-12 did not differ between the two groups.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of total amount values of urinary cytokines between responder and non-responder groups at the eight instillation. Urinary IL-2 value in responder group was significantly higher than that in non-responder group (10.6±12.9 ng/24 h vs. 0.18±0.43 ng/24 h, p<0.01). Bars represent values plus standard deviation (SD), *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Y axis is scaled in logarythmic order

Prognostic cytokines for responders.

Table 4 shows the results of the Cox's proportional hazard regression analysis for predicting the response to BCG instillation. IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α were prognostic cytokines by simple regression analysis. Multivariate analysis revealed IL-2 as an independent prognostic cytokine for the responders.

Table 4.

Cox's hazard regression model for the non–responder

| Variable | Risk ratio | 95% CI | P–Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple regression | |||

| IL–2 | 0.368 | 0.029–0.895 | 0.003 |

| IL–6 | 0.983 | 0.951–0.998 | 0.023 |

| IL–8 | 0.988 | 0.975–0.998 | 0.013 |

| IL–10 | 0.957 | 0.892–0.995 | 0.009 |

| TNF–α | 0.983 | 0.951–0.998 | 0.012 |

| Multiple regression | |||

| IL–2 | 0.368 | 0.029–0.895 | 0.003 |

Discussion

We previously reported that much of the cytokine-mediated antitumor activity of BCG was attributable to cytotoxic cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α [18]. Recently, the sequence of events in the immune response cascade after BCG intravesical instillation therapy has been elucidated [1, 22]. Initially, BCG organisms bind to both tumor and normal urothelium via fibronectin. Ratliff et al. showed that this process was a prerequisite for the mediation of the antitumor response [27]. The activated urothelial cells release chemokines such as IL-8 which serve to recruit neutrophils to a local site, proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), followed by up-regulation of adhesion-molecule expression (intracellular adhesion molecule 1; ICAM-1) which promotes effector cell-tumor cell interactions [13]. The activated neutrophils stimulate macrophages, which in turn initiate phagocytosis of infected urothelium, and release IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. The released IL-12 activates both natural killer (NK) cells, leading to the lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells, and immature CD4 positive T lymphocytes (Th0), leading to mature CD4 positive T lymphocytes (Th1). Activated Th1 cells release IL-2 and IFN-γ. These cytokines and activated urothelium induce major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules which are recognized by Th1 cells. The local immunoreaction caused by BCG therapy is characterized by a major infiltration of predominantly CD4 positive T lymphocytes into the bladder wall [24]. CD4 positive T lymphocytes have a licensing ability to the antigen presenting cell (APC) by binding to class II antigens in the presence of a helper epitope. Ikuta et al. reported that hydrophobized polysaccharide-truncated HER2 protein complexes could process the protein to present helper epitopes as well as cytotoxic T cell (CTL)-epitopes on the APC [10]. Cancer cells and BCG complex are likely to enter APC by phagocytosis, leading to the presentation of both helper and CTL-epitope, which are prerequisite for licensing APC to induce CTL. Wang et al. reported that γδ cells, which work as cytotoxic lymphocytes without restriction of MHC class II molecules, produced IL-2 and IFN-γ by BCG activation, and were able to lyse bladder tumor cells in an MHC-unrestricted fashion [30]. We measured various cytokines which take part in the cytokine cascade for the antitumor effect of BCG. Identification of the most important cytokines for the prediction of antitumor response and/or recurrence is a pressing issue. In this study, Cox's proportional hazard regression analysis revealed IL-2 as an independent prognostic cytokine of responder status.

Although IL-2 was not detected after the first BCG intravesical instillation, it was strongly detected after the eighth instillation in this study. This result was consistent with those of other investigations [4, 5, 28]. These findings suggested that IL-2 is produced in the late phase of the cytokine cascade. IL-2 is mainly produced by Th1 cells as well as by macrophages and γδT cells, therefore, it is likely that the success of BCG treatment is due to the preferential induction of Th1 cytokines such as IL-2. This supposition may be supported by the data showing that IL-2 was a strong predictive factor for the response to BCG intravesical instillation therapy [5, 28].

Several investigators have reported IL-8 as an important prognostic factor for tumor recurrence and progression [8, 25, 29]. Our results are partly consistent with this, since IL-8 turned out to be one of the prognostic cytokines by simple regression analysis in this report. The elevation of IL-8 may be one of the random inflammatory cytokines whose production is induced by BCG therapy.

Our results suggest that urinary IL-2 at the eighth intravesical instillation of BCG is a valuable prognostic factor of treatment efficacy as well as progression after treatment. Since urine collected for 24 h was used for cytokine measurement in this study, our results may be more accurate than those of other investigators who used spot urine for cytokine measurement. However, there are some problems that should be overcome before clinical application of this study. Firstly, 1-day hospitalization was needed for the evaluation of the effect. Secondly, the effect was evaluated only from urine after the eighth instillation. Saint et al. used spot urine samples obtained 4, 6, and 8 h after each instillation, and found significant differences in IL-2 concentrations between responders and non-responders at the second instillation of the second course [28]. These results indicate that appropriate spot urine samples may be used for the accurate prediction of the treatment. One may consider the difference of stability of cytokines between immediate processing group (the first 10 cases) and frozen group (another 10 cases). Two factors may affect on the stability of cytokines in this study. One is the influence of coexisting cellular fragments in the stored urine. Reijke et al. reported that a significant difference of cytokine concentration (IL-1β and TNF-α) was observed between frozen urine with immediate centrifugation before freezing and those without [8]. Another is the influence of storage temperature on the specimens. In the preliminary experiments, no significant difference in concentrations was observed for most of the cytokines including IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α, between the immediate processing group and the frozen group (data not shown). Our data may be supported by the report that IL-6 was stable for several years when stored at −20C [17].

A prospective study with the use of spot urine samples on an out-patient basis will clarify this issue, and facilitate the clinical application of these preliminary results.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. K. Takai, M. Tsuchida, T. Wada for collecting urine specimens, and Ms. K. Kurafuji for technical support.

References

- 1.Alexandroff Lancet. 1999;353:1689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07422-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettex-Galland Eur Urol. 1991;19:171. doi: 10.1159/000473608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Böhle J Urol. 1990;144:59. [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1992;34:306. doi: 10.1007/BF01741551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Urol Res. 1997;25:31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;31:182. doi: 10.1007/BF01744734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Cell Immunol. 1992;140:304. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De J Urol. 1996;155:477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischmann Cancer. 1989;64:1447. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891001)64:7<1447::aid-cncr2820640715>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikuta Blood. 2002;99:3717. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson Int J Cancer. 1993;55:921. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1993;36:25. doi: 10.1007/BF01789127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:309. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.4.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1995;40:119. doi: 10.1007/s002620050153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;99:369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb05560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson J Urol. 1998;159:1054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kenis Cytokine. 2002;19:228. doi: 10.1016/S1043-4666(02)91961-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurisu Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1994;39:249. doi: 10.1007/s002620050121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamm Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamm Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;310:335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morales J Urol. 1976;116:180. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58737-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patard Urol Res. 1998;26:155. doi: 10.1007/s002400050039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prescott J Urol. 1990;144:1248. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39713-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prescott J Urol. 1992;147:1636. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabinowitz J Urol. 1997;158:1728. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratliff Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1986;40:375. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(86)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratliff J Urol. 1988;139:410. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saint J Urol. 2001;166:2142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thalmann J Urol. 1997;158:1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Scand J Immunol. 1993;38:239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]