Abstract

All people have a fingerprint that is unique to them and persistent throughout life. Similarly, we propose that people have a gaitprint, a persistent walking pattern that contains unique information about an individual. To provide evidence of a unique gaitprint, we aimed to identify individuals based on basic spatiotemporal variables. 81 adults were recruited to walk overground on an indoor track at their own pace for four minutes wearing inertial measurement units. A total of 18 trials per participant were completed between two days, one week apart. Four methods of pattern analysis, a) Euclidean distance, b) cosine similarity, c) random forest, and d) support vector machine, were applied to our basic spatiotemporal variables such as step and stride lengths to accurately identify people. Our best accuracy (98.63%) was achieved by random forest, followed by support vector machine (98.40%), and the top 10 most similar trials from cosine similarity (98.40%). Our results clearly demonstrate a persistent walking pattern with sufficient information about the individual to make them identifiable, suggesting the existence of a gaitprint.

Keywords: Biometrics, Gait Recognition, Variability, Random Forests, Support Vector Machines, Inertial Measurement Units

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

People have a Gaitprint – a persistent and identifiable walking pattern.

-

•

Uniqueness of gait kinematics demonstrated 98.63% accuracy in 81 adults.

-

•

Multi-day identification is accurate at 95.47%.

1. Introduction

An interesting passage in 1897 recounts the ability for a train dispatcher to recognize each of his 40–50 men after hearing a few words rapidly emitted by telegraph [1]. Seemingly “every operator develops a distinctive style of sending [telegraphs] so that he can be recognized readily by those who work with him constantly” [1]. The train dispatcher’s words capture, in essence, the idea that the way people move their bodies provides subtle clues about a person’s identity. Walking is a fundamental movement of the human body and is ubiquitous in daily life. Walking generally entails the same process, such as moving the center of mass over the support leg; however, there is considerable variety in the way that any given person solves this task. The uniqueness implied by that description supports the idea that each person might possess a “gaitprint” in the same way each person has an enduring fingerprint observable across the lifespan. Indeed, one can reliably identify friends and family with limited visual - in the extreme, only auditory - information. For example, in the classic ‘point light walker’ paradigm, reflective markers that are placed on anatomical landmarks of a participant are video recorded during walking [2], [3], [4]. Otherwise, the room is completely dark such that, when played, the video displays a series of floating white dots on a black background. Days or months later, the same collection of participants are able to recognize each other, and naïve participants can recognize changes in the behavior of an unknown person’s actions [2], [3], [4]. Anecdotally, people can also identify others based purely on the sounds of their stepping patterns from the variance in their cadence. This ability appears to be supported by literature [5], [6]. Despite those indirect results, the actual question as to whether people exhibit a unique gaitprint remains unanswered. In this manuscript, we contend that the key to discovering a gaitprint rests on the examination of the variability in human movement. Based on that contention, the purpose of this paper is to capitalize on the fundamentals of human movement, and its variability, to produce evidence for unique gaitprints, a collection of gait features that can reliably identify an individual [7]. We hypothesize that principled gait features including movement variability can uncover a unique gaitprint for each person [8]. To probe this hypothesis, we draw from numerous methods to accurately identify individuals with quantitative descriptions of lower-body kinematics [2], [9]. We combine simple pattern recognition techniques with detailed, multi-day measurements of gait features to identify each individual's gaitprint.

1.1. Human movement and the gaitprint

Many human movements, like walking, entail many repetitive cycles. Despite the cyclic nature of gait, there is considerable variability from one stride to the next. Some steps are short; some are long. Some steps are slow; some are fast. The variability across cycles was conventionally interpreted as a representation of uncontrolled noise and/or error to be removed [8]. However, a large amount of research has revealed that the variability underlying human movement and signals is not merely uncontrolled noise nor error [8], [10], [11], [12]. Based on these findings, here we propose a novel hypothesis that the variability observed over repetitive gait cycles is fundamental to the unique strategies people employ to walk about the world. That is, variability reflects the unique walking solutions learned over the course of development. Hence, variability encapsulates the developmental history of an individual and is the source of features that ultimately allow identification from gait features.

More formally, we define a gaitprint as a set of kinematic and kinetic features measured during locomotion that uniquely identify an individual. As an analogy, a fingerprint contains ridges with swirls and arches of varying widths that ultimately lead to changes in ridge placement, orientation, or bifurcations [7]. Microclimates within the womb detail the makeup of a fetus’ fingerprint within an environment that will never be the same [7]. Much like the ridges of finger pads providing meaningful information about the person, a certain set of gait characteristics including kinematics and spatiotemporal variables directly influence gait. Distinct joint trajectories, stride lengths, and other parameters, are the ‘ridges’ of gait that provide distinct information about walkers. These ‘ridges’ ultimately form a toolbox from which we can selectively use gait features to distinguish between people using pattern recognition.

1.2. Gait as a biometric

The use of gait features for biometrics – identification based on bodily motion and features – is not new [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]. There are many technologies that have been brought to bear in identification by gait; most commonly, silhouette-based technologies. This method takes a video of a person walking and creates a silhouette around them to separate their movement from the background environment. The silhouette’s size, shape, or three dimensional overlays of the person’s anthropometrics can be compared between people for identification purposes [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. Alternatively, radar, acoustics, foot pressure, and ground reaction forces have all been used to identify people based on their gait [5], [6], [13], [15], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31]. However, a common aspect of the noted methods is that rarely do these approaches take into consideration the aspects of gait that are relevant from a biomechanical standpoint. To extract biomechanically meaningful variables, two of the most precise methods for measuring gait are optical motion capture systems or body worn inertial measurement units. In the former, small markers are placed on the body and tracked via infrared cameras in a fixed measurement volume which severely limits the ability to obtain walking typical of everyday activity. In the latter, small sensors are placed on the body that directly measure physical quantities (e.g., acceleration) in virtually any environment. Directly monitored gait kinematics, or their estimations, have led to a range of identification success with accuracy ranging between 42 to 100%, on par with radar or silhouettes [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. Silhouette, radar, and kinematics-based identification each serve their own purpose, each with strengths and weaknesses. For example, silhouette and radar can be used in many locations, do not require new or expensive equipment, and can identify individuals without their knowledge. Kinematics identification, however, may require special equipment applied to the participant but benefits from directly measuring the movement of the individual. Our team’s approach focused on circumventing issues that trouble other methods of person identification, such as silhouette and radar, by focusing pattern recognition on a simple framework of fundamental biomechanical gait features. By providing further evidence that gait kinematics contain information used for identification, those insights can be more effectively applied to silhouette or other remote observational methods (e.g., computer vision, radar, etc).

1.3. Advantages

The present work may be distinguished not by the specific technology or algorithms involved, but the use of meaningful features of gait. We focus on basic lower body gait descriptors that are computationally efficient and easily described to a lay person, unlike other, more abstract means of pattern recognition [33], [40]. For example, stride lengths and widths can be easily recognized in real time and are intuitive to interpret and describe. The straightforward measurement of preferred overground walking focuses attention on the readily available gait features that are the basis of all gait recognition studies. Observations in an environment that is representative of day-to-day life (curvilinear walking paths with variable lighting, noise, and foot traffic) rather than a sterile laboratory with treadmills that are known to affect gait, is also a benefit [41], [42], [43]. Those advantages serve as the foundation for the pattern recognition study reported here. The strength of our approach is that intrinsic kinematics-based information used for identification can be applied to other identification methods, such as computer vision or radar, assuming gait is captured in adequate detail [15], [25], [27], [28], [44]. That is, if the specific gait features capable of capturing a gaitprint are known, any means of acquisition may be used for person identification.

1.4. Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to determine if gait is unique to each person. Overall, we hypothesize that the way each person walks reveals subtle information about their identity.

2. Methods

2.1. Data acquisition

Twenty-six young adults between the ages 19–35 (12 female, 24.5 ± 2.1 years old, 174.5 ± 7.0 cm tall, weighing 72.3 ± 15.6 kg), 28 middle-aged adults between the ages 36–55 (24 female, 46.4 ± 6.1 years old, 170.5 ± 7.4 cm tall, weighing 80.9 ± 14.6 kg), and 27 older adults greater than 55 years old (12 female, 64.3 ± 6.2 years old, 172.2 ± 9.3 cm tall, weighing 80.6 ± 15.9 kg) were sampled from the NONAN GaitPrint dataset [45]. Each participant came into the lab twice, spread one week apart, to complete 9 walking trials per session. Participants were given a short, optional break after every 3 trials. Each trial (n = 1458 total) involved 4-minutes of overground walking at a self-selected pace on a 200-meter indoor track. All participants and trials began at the same starting point and were walked along the outermost lane of the track. All 18 trials were walked clockwise (n = 846 total) or counterclockwise (n = 612 total) depending on the day of the week, due to facility rules. All participants completed their second session 7 days following their first session. All participants returned for the second session wearing the same shoes worn during their first session. All notes or data that deviated from our protocol can be found in the supplementary material.

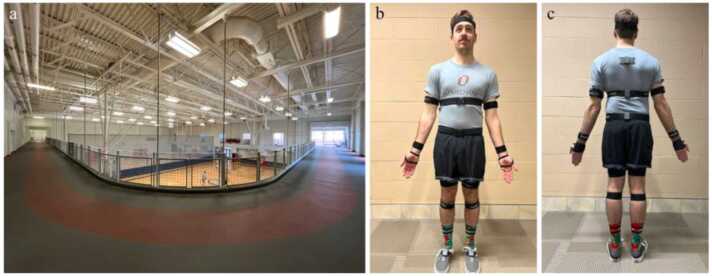

Kinematic data was collected by 16 Noraxon Ultium Motion inertial measurement units (IMUs) recording at 200 Hz (Fig. 1) placed on the extremities, trunk, and head of each participant. Sensor calibrations were completed before each trial along the same section of the indoor track. A total of 74 variables were calculated including bilateral spatiotemporal variables consisting of distance traveled, average speed, cadence, stride and step lengths, widths, and times, supplemented by the percentage of stance, swing, and support phases (see Supplementary Material for code and Supplementary Figures for all variables). Bilateral lower body joint angles (hip, knee, ankle) were used to calculate their mean and standard deviations of peak flexion, extension, range of motion, and velocity. All spatiotemporal calculations were completed in Matlab version R2023b and the following data handling and identification models were completed using Rstudio version 4.3.1 [46], [47], [48], [49].

Fig. 1.

(a) Indoor track where overground walking data was collected. (b&c) Anterior and posterior views of the Noraxon IMU setup.

2.2. Data handling

We used three methods to split our data into galleries and probes (Fig. 2). Split 1 (70/30) included a random 70%/30% split of all trials to be placed in the gallery and probe, respectively. That meant a total of 1020 walking trials were used as the gallery for the remaining 438 probe trials. Split 2 (referred to henceforth as Day 1) used all trials from day 1 as the gallery set, and the day 2 trials were used as the probe. That is, 729 trials were used as the reference for the remaining 729 probe trials. Split 3 (now referred to as Trial 1) used the very first trial from day 1 as the gallery set, and the remaining 17 trials per participant were used as the probe. A total of 81 walking trials were used as the gallery for the remaining 1377 probe trials. For clarity, galleries and probes contained the same participant but did not share the participant’s same trials. For example, the random selection in 70/30 permits the opportunity for a participant to have a random selection of their 1–17 trials in the gallery, with the remaining trial(s) placed in the probe. For Day 1, the first 9 trials of the participant were placed in the gallery, and the remaining 9 trials were placed in the probe. For Trial 1, only the participant’s first trial was categorized into the gallery, and their remaining 17 trials were used in the probe. All participant data, including height, weight, anthropometrics, trial details, as well as kinematic features, can be found in the supplementary material. Kinematic time series for the young adults are also published elsewhere, and the data from the middle and older adults soon to follow [45].

Fig. 2.

Visualization of the amount of data split into a probe and gallery for three split methods. 70/30 data is split as 70% gallery and 30% probe. Day 1 data is split as 50% gallery and probe. Trial 1 data is split as 5.56% gallery and 94.44% probe.

2.3. Identification methods

Gait identification was performed using 4 common methods found in the literature: Euclidean distance (ED), cosine similarity (CS), random forest (RF), and support vector machine (SVM) classifiers [13], [17], [22], [50], [51], [52], [53]. ED, CS, RF, and SVM can further be divided into two categories, distance-based identification (DBI) and machine-based identification (MBI). Both DBI and MBI methods used all 74 kinematic variables segmented by our three methods of splitting trials into galleries and probes. We also present DBI accuracy as Rank 1, Rank 5, and Rank 10 (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Each rank represents the most similar, as well as a pool of the 5 and 10 most similar comparisons, to make a true or false decision about the correct attribution of each probe trial to a gallery trial, respectively. Regarding MBI, when applying RF and SVM, we used public R packages including random Forest, stats, and e1071, along with custom functions found in our supplementary material [52], [53], [54]. Our two MBI methods only contain Rank 1 accuracy.

Table 1.

Correct identification accuracy (%) per data split for Euclidean distance (ED), cosine similarity (CS) random forest (RF) and support vector machine learning (SVM).

| Split | ED Rank 1 | ED Rank 5 | ED Rank 10 | CS Rank 1 | CS Rank 5 | CS Rank 10 | RF | SVM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70/30 | 91.55 | 94.75 | 96.35 | 95.66 | 97.49 | 98.40 | 98.63 | 98.40 |

| Day 1 | 74.07 | 87.79 | 91.49 | 80.25 | 91.91 | 95.47 | 91.08 | 92.59 |

| Trial 1 | 42.99 | 60.35 | 67.90 | 58.17 | 74.80 | 84.02 | 70.66 | 65.94 |

Fig. 3.

Identification accuracy per data split for Euclidean distance (ED), cosine similarity (CS) random forest (RF) and support vector machine learning (SVM). Dashed horizontal line clarifies 90% accuracy.

The two DBI methods were chosen based on their computational efficiency and simplicity. To use ED for identification, each walking trial was considered a vector of numbers with each cell representing a numeric value for one of the 74 kinematic variables. ED between the vector of a probe trial and the vector of each gallery trial, individually, was then calculated. If the closest ED between the probe and any galleries were from the same participant, that result was considered a correct Rank 1 identification. If one the five closest ED were from the same participant, that was considered a correct Rank 5 identification, and one of the ten closest ED was considered correct for Rank 10. CS followed a similar procedure to ED, except the cosine similarity between the vector of a probe trial and the vector of each gallery trial, individually, was calculated. If the highest CS (closest to 1 on a scale of −1 to 1) between the probe and any gallery were from the same participant, that result was considered a correct Rank 1 identification. Rank 5 and Rank 10 identifications follow the same procedure as ED. Summarized, ED was calculated simply as the L2 norm between two vectors (kinematic variables) and CS was calculated as the normalized dot product between two vectors (kinematic variables).

The two MBI methods were chosen because they represent two common, yet effective, machine learning algorithms. The two chosen methods are more interpretable than many machine learning methods, providing insight into individual feature importance. The RF classifier constructs multiple decision trees based on subsets of the data and features and then combines their outputs to identify unique gait patterns. Each tree in the forest votes for a particular classification (i.e., person), and the most popular classification is chosen as the outcome. In the current context, this method analyzes variability in gait features with its collective decision-making process to pinpoint individual gaitprints. The RF input arguments were kept simple by using one permutation of 500 trees, with replacement, using one-third of the number of predictors to split each node. Similarly, the SVM classifier identifies individuals by finding the optimal separation between different gaitprints in a multidimensional space of gait variables. SVM transforms the original gait variables into a higher-dimensional space to make the separation of gait patterns discernible. This separation is achieved through a decision boundary (i.e., a hyperplane) that best divides the data points of individuals, based on their unique gait characteristics. SVM’s input arguments were also simple and involved C-Classification with a linear kernel using data scaled to zero mean and unit variance. Specific input arguments for RF and SVM can be found in the supplementary material, and neither algorithm was specifically tuned to improve performance.

2.4. Three sets of identification

We performed identification using different strategies with two aims: (1) to determine if our set of kinematic variables could be used for person identification, and (2) to understand the relative contribution of individual gait features for person identification. First, we took each of the three data splits (70/30, Day 1, Trial 1) and attempted to identify all participants using our four methods (ED, CS, SVM, RF). Second, we extracted SVM weights (Supplementary Figures 1–3) and RF importance values (Supplementary Figures 4–6) from the modeling efforts above. We then pursued two additional modeling strategies, an “add one on” (AOO) approach and a ”leave one out” (LOO) approach. In AOO, we took the most important variable (according to the SVM weights or the RF importance depending on the data distribution) and tried to identify participants with that single variable. We then added the second most important variable attempted identification with those two variables. This process repeated until we included the 74th gait feature which was the least important. In LOO, we removed one gait feature (i.e., Cadence), calculated the identification accuracy with the remaining 73 gait features, then put it back. Then, we removed a different gait feature (i.e., Step Time), calculated the identification accuracy with the remaining 73 gait features, then put it back. We repeated this process until 74 identifications were made, one for each removed gait feature. Positive percent changes in identification accuracy () were interpreted as an improvement in identification accuracy when a variable was excluded and negative percent changes were interpreted as a decline in identification accuracy.

3. Results

3.1. Identification accuracy

Overall, subject identification was remarkably accurate considering the intended simplicity of our approach (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Out of the 24 identification combinations noted in Table 1, only 5 were below 70% accuracy, 6 were between 70–90% accuracy, and 13 were above 90% accuracy. Of the 13 results resting above 90% accuracy, 3 reached at least 98% accuracy. Unsurprisingly, accuracy decreased as the size of our gallery trials decreased, more so when using DBI compared to MBI. In terms of the 70/30 split, the best approaches were RF, followed by SVM, CS Rank 1, and ED Rank 1. In terms of the Day 1 split, the best approaches were SVM, RF, CS Rank 1, and ED Rank 1. In terms of the smallest gallery from Trial 1, the best approaches were RF, SVM, CS Rank 1, and ED Rank 1. ED Rank 1 always had the worst performance compared to all other DBI and MBI approaches.

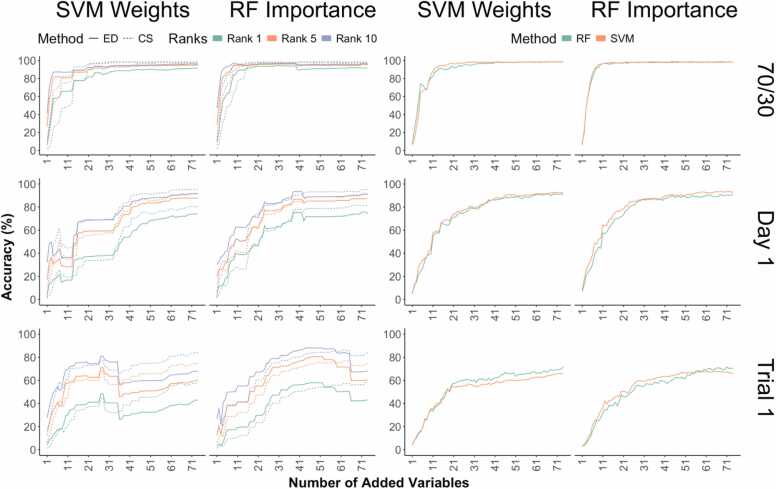

3.2. AOO

AOO results can be found in Fig. 4 and Table 2. Overall, ED appears more efficient than CS along with SVM being more efficient than RF. Interestingly, SVM was best when using RF importance, and RF was best using SVM weights, rather using than their own rankings of importance. Unexpectedly, neither SVM nor RF reached 80% accuracy from identifications trained on only the first trial.

Fig. 4.

Identification accuracy results from the AOO identifications using Euclidean distance (ED), cosine similarity (CS) random forest (RF) and support vector machine learning (SVM). The x-axis represents the number of variables used for the identification accuracy specified on the y-axis. Row one contains the results from the 70/30 data split, row two contains the results from the Day 1 data split, and row three contains the results from the Trial one split. Column one shows the results for the distance-based methods colored by rank and line type specified by ED or CS. Column two shows the results for the machine-based methods colored by RF or SVM. Column one and two are subdivided into AOO using either the SVM weights or RF importance. The order of SVM weights and RF importance can be found in Supplementary Figures 1–6.

Table 2.

AOO identification accuracies. Column one outlines the data distributions and column two outlines the grouping of the identification method as distance-based (DBI) or machine-based (MBI). Column three indicates if the 74 features were included in the order of the greatest to least important SVM weights or RF importance. Column four designates the most efficient identification method according to the least amount of features in column five, and its respective accuracy in column six. The asterisks in Trial 1 indicate the inability for RF and SVM to reach greater than 80% accuracy with less than all 74 features.

| Distribution | Method Group | AOO Order | Method | # Features | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70/30 | DBI | SVM Weights | ED Rank 10 | 3 | 81.05 |

| DBI |

RF Importance |

ED Rank 10 |

3 |

85.39 |

|

| MBI | SVM Weights | RF | 10 | 80.82 | |

| MBI | RF Importance | SVM | 6 | 85.39 | |

| Day 1 | DBI | SVM Weights | CS Rank 10 | 37 | 81.21 |

| DBI |

RF Importance |

ED Rank 10 |

24 |

84.64 |

|

| MBI | SVM Weights | SVM | 29 | 80.93 | |

| MBI | RF Importance | SVM | 22 | 81.07 | |

| Trial 1 | DBI | SVM Weights | ED Rank 10 | 27 | 81.05 |

| DBI |

RF Importance |

ED Rank 10 |

32 |

81.69 |

|

| MBI* | N/A* | RF* | * 74 | * 70.66 | |

| MBI* | N/A* | SVM* | * 74 | * 65.94 | |

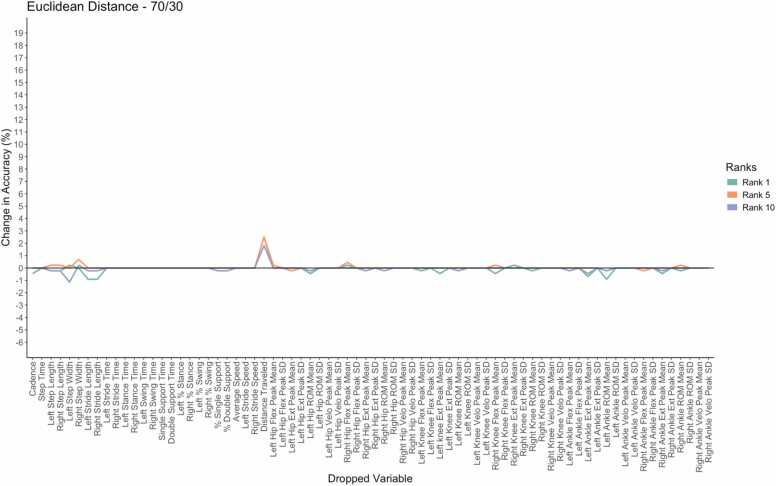

3.3. LOO

LOO identification results can be found in Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7 and Supplementary Figures 7–12. The LOO results themselves are largely unremarkable because all changes in accuracy were within ± 4% except for Day 1 and Trial 1 Distance Traveled. However, the average change in accuracy (average of the 74 LOO accuracies for each distribution and identification method), largely shows a slight decrease in accuracy when individual gait features are removed (Table 3). In general, the DBI methods better handle the loss of a single gait feature compared to the MBI methods. Furthermore, the greatest average change in accuracy was RF Day 1 and the smallest average change in accuracy was 70/30 CS Rank 5.

Fig. 5.

LOO identification accuracies with the x-axis showing the currently dropped variable and identification accuracy using the remaining 73 variables on the y-axis for ED within the 70/30 split. Positive changes in accuracy are improvements and negative changes are declines in accuracy. Each line is colored by rank and the solid black line represents no change in accuracy.

Fig. 6.

LOO identification accuracies with the x-axis showing the currently dropped variable and identification accuracy using the remaining 73 variables on the y-axis for CS within the 70/30 split. Positive changes in accuracy are improvements and negative changes are declines in accuracy. Each line is colored by rank and the solid black line represents no change in accuracy.

Fig. 7.

LOO identification accuracies with the x-axis showing the currently dropped variable and identification accuracy using the remaining 73 variables on the y-axis for RF and SVM within the 70/30 split. Positive changes in accuracy are improvements and negative changes are declines in accuracy. Each line is colored by RF or SVM and the solid black line represents no change in accuracy.

Table 3.

Change in accuracy relative to the complete feature set. Column one outlines the data distribution, column two outlines the identification method and its corresponding mean ± standard deviation accuracy in column three. The table is ordered from the greatest to least average magnitude using column three.

| Distribution | Method | Change in Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 70/30 | RF | -0.09 ± 0.26 |

| ED Rank 1 | -0.07 ± 0.38 | |

| CS Rank 10 | -0.06 ± 0.12 | |

| ED Rank 5 | 0.05 ± 0.32 | |

| ED Rank 10 | -0.03 ± 0.27 | |

| CS Rank 1 | -0.02 ± 0.22 | |

| SVM | -0.01 ± 0.11 | |

| CS Rank 5 | 0.00 ± 0.20 | |

| Day 1 | RF | -0.62 ± 0.59 |

| SVM | 0.12 ± 0.27 | |

| CS Rank 10 | -0.11 ± 0.26 | |

| CS Rank 1 | 0.07 ± 0.67 | |

| ED Rank 10 | -0.06 ± 0.55 | |

| ED Rank 1 | 0.05 ± 1.01 | |

| CS Rank 5 | -0.05 ± 0.33 | |

| ED Rank 5 | 0.04 ± 0.63 | |

| Trial 1 | SVM | 0.20 ± 0.41 |

| RF | -0.18 ± 0.90 | |

| CS Rank 10 | -0.14 ± 0.79 | |

| CS Rank 1 | -0.14 ± 0.77 | |

| ED Rank 10 | 0.07 ± 2.14 | |

| ED Rank 5 | 0.03 ± 1.74 | |

| ED Rank 1 | -0.02 ± 1.79 | |

| CS Rank 5 | 0.01 ± 1.01 | |

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that relatively simple methods of data identification combined with basic gait descriptors effectively distinguish between individuals. We applied DBI and MBI pattern recognition to spatiotemporal characteristics derived from 81 adults walking on an indoor track wearing IMUs. Cosine similarity was the better of the two DBI methods reaching 98.40% accuracy when using Rank 10. Furthermore, our results showed near-perfect accuracy (98.63%) when using RF trained on 70% of the data and probed with the remaining 30%. As we reduced the size of our gallery set, identification accuracy decreased, but MBI approaches proved more robust in handling such reductions.

4.1. Comparisons to previous literature

Our study's results are consistent with, or surpass, previous literature focusing on identifying individuals based on walking features. We outperformed silhouette-based identification in some cases [19], [22], [55], [56], [57], [58]. We also observed robust identification across days, which can plague silhouette identification due to changes in clothing [19], [59]. Furthermore, one paper collected gait data four times over two months and achieved a best Rank 1 performance of 63%, a value lower than all our Day 1 metrics [22]. Five out of eight of our methods were also better than their best top 5% performance (88%) as well [22].

A more appropriate comparison to previous literature includes our ability to exceed the expected accuracy of at least 70% compared to studies using similar kinematic variables [32], [34], [35], [36], [37], [39]. For example, one study applied joint angle trajectories with ED on two datasets to reach 73% and 42% accuracy [34]. The former result is surpassed by ED Rank 1 at the 70/30 (91.55%) and Day 1 split (74.07%), and the latter is surpassed by Trial 1 (42.99%). Another study used 41 lower body features to achieve 88.78% accuracy using SVM, only higher than our SVM Trial 1 (65.94%) but not Day 1 (92.59%) or 70/30 (98.40%) [32]. Comparatively, our use of SVM achieved accuracies greater than 88.78% with as little as 7 variables (70/30; 90.87%). Admittedly, the initial set of gait features was quite large because we used roughly 19 trials (essentially one participant) for every gait feature. The ability to reach 90 + % accuracy using as little as 7 gait features indicates room for optimization because less important variables are already excluded for good performance. The LOO results also suggest that many gait features may be omitted without degrading accuracy. Using so many gait features per participant is useful for identifying a gaitprint but wasteful if the goal is to execute many computationally efficient identifications. However, there is a possibility that our performance was inflated like two other studies using more complex data manipulations, and many more variables, to reach an accuracy of at least 99.5% [33], [40]. Although, given our high accuracy with only small subsets of gait features, that does not seem likely. Furthermore, we emphasize that our model is more generalizable compared to other kinematics-based methods because we use an intuitive approach that remains grounded on direct kinematic measurements and potentially quicker to compute through basic gait features. That is not to say, however, that other methods are less capable, like silhouette identification, that reach 99% accuracy even under multiple constraints [60]. Therefore, the intuitiveness of this paper lends itself to support the peculiar ability to recognize friends and family by their gait at a far enough distance where facial features, clothing, or clear vision may be unreliable.

As anticipated, identification becomes more challenging with a smaller gallery. Nevertheless, even with less than 6% of our data used for gallery (Trial 1), we achieved over 80% accuracy using, which is remarkable. Splitting our data in half (Day 1), all but one method was at least 80% accurate. Additionally, our findings showed excellent accuracy (over 90%) when using a gallery from the first day's data (Day 1) and probing on the second day, addressing the challenges of multi-day identification [19], [22]. However, it is worth noting that our study investigated gait with a 7-day gap, while other studies spanned months or even one year, potentially allowing for more significant natural gait changes [19], [22], [61]. Inter-day identification suggests that gait is inherently variable but still contains consistent characteristics or a unique “gaitprint”. However, the existence of unique gaitprints can only be certain if thousands of research participants are sampled repeatedly throughout their lifetime.

4.2. Limitations and future directions

Consistent with the limitations of other identification methods that require a designated space for equipping participants and capturing data (i.e., fingerprinting), the burden still lies upon the participant to come into the lab to wear equipment that is typically not available to the public. We hope, however, that the development of markerless motion capture, or video-based algorithms implemented into cellphones, can be used to provide detailed accounts of the entire body like those studied here. Advancements in markerless motion capture technology that can calculate reliable and accurate gait kinematics will permit highly accurate, yet surreptitious, person identification based on how we walk [62]. Coupled with the present study’s ability to accurately detect individuals based on gait, we will then be able to knock out two main problems of gait identification. The first issue is quantifying gait in a natural environment without instrumentation and the second issue is the currently worked on challenge of extracting gait kinematics due to the limitations of videography [13], [39], [63]. Once those two issues are remedied, researchers may then employ our biomechanical approach, focused on directly measuring gait kinematics, with confidence that people can be identified based on their gait patterns, without having to consider equipment error. The eventual implementation of identification algorithms and equipment in the commercial setting will make gait identification a more common aspect of daily life.

There are many other ways which someone might attempt to modify their gait. For instance, one vulnerability of gait identification is spoofing or deception [15]. There is no doubt that gait can be changed due to observation, to avoid falling, to be humorous, or to avoid identification. In addition, few studies report varying levels of success when trying to impersonate other people’s gait patterns [64], [65], [66]. However, the impersonator must know they are being monitored and may find it difficult to copy another person’s gait over extended periods. Gait impersonation appears realistic if the requirement is to replicate distinct walking styles that require extended stride lengths or widths. But the replication of joint velocities and accelerations would be a necessary, more challenging task. Perhaps screen- or play-actors will find it easier to impersonate someone else’s gait; but, further evidence is needed to support or refute gait identification as a security measure [64], [65], [66]. Furthermore, changes to behavior can occur from the simple act of observation causing participants to walk atypically (i.e., the Hawthorne effect) [67], [68]. Regardless, the robustness of our method to each of those potential threats to identification will need to be rigorously tested for our method to gain full utility in applied settings such as security.

Future studies in gait identification aim to achieve perfect identification accuracy by further refining the motion capture and kinematic-based perspective. While this paper focused on linear measures (capturing the central tendency and the magnitude of variation) of angular and spatiotemporal gait features as proof of concept, there could be room for improvement by incorporating additional variables into the identification parameters. Further refinement may also be achieved by swapping out, or selecting, the most predictive gait characteristics for identification. For example, our modeling efforts showed that reasonable accuracy could be maintained with less than 10 gait features. A feature set of 10 variables may also be further leveraged for identification by tuning the hyperparameters of each classification method. Parameter sweeps can be conducted for each algorithm, and each algorithm’s input arguments, to maximize efficiency and accuracy. Incorporating those features with other modeling approaches, and their optimized forms, is an exciting area for future research in which we are currently engaged.

We are also exploring the value of incorporating nonlinear time series measures (capturing the temporal structure of variation) as additional gait features, considering the importance of movement variability. However, some nonlinear analysis methods require a large number of strides for accurate results, which are not feasible in stationary camera settings where the pedestrian may walk in and out of the capture space. Nonetheless, related work from our lab provided evidence supporting the replacement of certain nonlinear analyses with reliable results using as few as 64 data points [69]. While this reduction still represents a significant number of strides depending on the identification space and population, we anticipate that nonlinear analyses will become useful predictors for identifying individuals in the near future [70]. Specifically, the structure of trial-to-trial variability may indicate individual uniqueness and provide insights into subtle coordination changes that reveal a person's identity. Our future capitalization on more nuanced measures of gait variability, rather than standard deviations, is expected to improve identification accuracy. The importance of nonlinear identifiers is supported by literature demonstrating their usefulness when investigating gait in different populations [8], [71], [72], [73]. Furthermore, a wider range of machine learning classifiers is being investigated, and the importance of variables in machine learning outcomes is being studied at present.

4.3. Significance

Our results suggested that a person's identity is indeed linked to gait patterns during overground walking. Our predictions ultimately rested on the primacy of movement variability in forming unique gaitprints. Consistent with that idea, variability measures were consistently among the most important parameters for MBI. Even at the most basic level of measurable variability, person identification has been strengthened. In addition, the method outlined here is computationally efficient. Because we chose easily conceptualized gait descriptors instead of complex transformations of our data, our 74 variables were quickly calculated and were ready for use in DBI and MBI applications. An efficient research team should be able to execute a quick pipeline (i.e., equip the participant with IMUs, calibrate the sensors, collect a short walking trial, export the data, apply automated scripts) for registration within 10–15 min.

In addition, our approach stands out from several others by virtue of a few secondary topics that are worth mentioning. First, the use of IMUs eliminated the challenges of camera viewpoint, clothing type, lens distortions, or shadows that could hinder identification performance. Second, our study benefited from a less constrained walking path. While many gait identification studies focused on capturing a few strides along a short, straight path or treadmill, we collected data from overground walking on an indoor track, encompassing different distances, curves, walking speeds, and number of strides [22], [31], [32], [33], [34], [39], [50], [61], [74]. Our basic spatiotemporal variables can also be visually described without difficulty, highlighting the observable differences that make two or more individuals distinguishable based on gait metrics.

Many researchers already hold terabytes of data waiting to be put to good use in more practical applications using inspiration from our approach. We suggest that our approach may assist other research teams to hone in on the subtle cues that may be used for security, indicate disease or disability, change in performance, or individuality itself. Gait identification may be used as a smart entry system, housed within a hallway that allows access through a restricted door opened by a particular group of individuals’ gait, rather than their fingerprint, iris scan, or keycard entry. Gait, or other unique movements, may be used to indicate a lack of performance, or the existence of individuality, in tasks such as communicating through telegraphic language, or the kinematics of typing, texting, swimming, running, or driving [1], [38]. Finally, the prediction of disease and disability later in life is an important practical application. Many clinical populations can be described by a single, visually distinct feature, like Trendelenburg gait. Throughout life, chronic, debilitating restrictions to functional capacity, are often not as noticeable due to incremental changes over many years. Future directions for gait identification should, and will, significantly impact healthcare by finding subtle gait features used for primary prevention to support excellent health, similar to gait speed or variability [75], [76], [77], [78].

5. Conclusion

Our study provided evidence that gait, and its variability, can serve as a distinguishing feature in humans. With four simple identification algorithms, we presented an easily understandable method for differentiating between individuals. We achieved near-perfect identification accuracy in some cases, but also observed deteriorating accuracy as our gallery size decreased. Future work will make use of nonlinear methods and more sophisticated modeling techniques to maximize accuracy in identifying people based on kinematic features. Moreover, while our findings support the existence of Gaitprints, there is still much more exciting work to be done before we can definitively claim that Gaitprints are an enduring property of the human motor control system. We are excited to engage in this work ourselves and look forward to developments from the larger body of literature.

Ethics Statement

Approval of all ethical and experimental procedures and protocols was granted by the University of Nebraska Medical Center IRB#0762–21-EP.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grant 2124918, National Institutes of Health Grant P20GM109090 and R01NS114282, University of Nebraska Collaboration Initiative, the Center for Research in Human Movement Variability at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, NASA EPSCoR, and IARPA.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nick Stergiou: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Aaron D Likens: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Tyler M Wiles: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Seung Kyeom Kim: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Joel H. Sommerfeld, Marilena Kalaitzi Manifrenti, Alli Grunkemeyer, Kolby J. Brink, Anaelle E. Charles, Mehrnoush Haghighatnejad, Narges Shakerian, and Taylor J. Wilson for their help with data collections. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their in-depth review.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2024.04.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

Supplementary material.

.

References

- 1.Bryan W.L., Harter N. Studies in the physiology and psychology of the telegraphic language. Psychol Rev. 1897;4:27–53. doi: 10.1037/h0073806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutting J.E., Kozlowski L.T. Recognizing friends by their walk: Gait perception without familiarity cues. Bull Psychon Soc. 1977;9:353–356. doi: 10.3758/BF03337021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson G. Visual Motion Perception. Sci Am. 1975;232:76–88. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0675-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troje N.F., Westhoff C., Lavrov M. Person identification from biological motion: Effects of structural and kinematic cues. Percept Psychophys. 2005;67:667–675. doi: 10.3758/BF03193523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bours P., Evensen A. 2017 International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology (ICCST) IEEE,; Madrid: 2017. The Shakespeare experiment: Preliminary results for the recognition of a person based on the sound of walking; pp. 1–6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umair Bin Altaf M., Butko T., Juang B.-H. Acoustic Gaits: Gait Analysis With Footstep Sounds. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2015;62:2001–2011. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2015.2410142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain A.K., Prabhakar S., Pankanti S. On the similarity of identical twin fingerprints. Pattern Recognit. 2002;35:2653–2663. doi: 10.1016/S0031-3203(01)00218-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stergiou N., Decker L.M. Human movement variability, nonlinear dynamics, and pathology: Is there a connection? Hum Mov Sci. 2011;30:869–888. doi: 10.1016/j.humov.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nixon M.S., Tan T., Chellappa R. Human identification based on gait. New York; London: Springer; 2006.

- 10.Van Orden G.C., Kloos H., Wallot S. Philosophy of Complex Systems. Elsevier,; 2011. Living in the Pink: Intentionality, Wellbeing, and Complexity; pp. 629–672. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eke A., Herman P., Kocsis L., Kozak L.R. Fractal characterization of complexity in temporal physiological signals. Physiol Meas. 2002;23:R1–R38. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/23/1/201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eke A., Hermán P., Bassingthwaighte J., Raymond G., Percival D., Cannon M., et al. Physiological time series: distinguishing fractal noises from motions. Pflug Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2000;439:403–415. doi: 10.1007/s004249900135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connor P., Ross A. Biometric recognition by gait: A survey of modalities and features. Comput Vis Image Underst. 2018;167:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cviu.2018.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibelli D., Obertová Z., Ritz-Timme S., Gabriel P., Arent T., Ratnayake M., et al. The identification of living persons on images: A literature review. Leg Med. 2016;19:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan C., Wang L., Phoha V.V., editors. A Survey on Gait Recognition. ACM Comput Surv 2019;51:1–35. https://doi.org/10.1145/3230633.

- 16.Makihara Y., Matovski D.S., Nixon M.S., Carter J.N., Yagi Y. In: Wiley Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering. 1st ed.., Webster J.G., editor. Wiley; 2015. Gait Recognition: Databases, Representations, and Applications; pp. 1–15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul M., Haque S.M.E., Chakraborty S. Human detection in surveillance videos and its applications - a review. EURASIP J Adv Signal Process. 2013;2013:176. doi: 10.1186/1687-6180-2013-176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J., She M., Nahavandi S., Kouzani A. 2010 International Conference on Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications, Sydney. IEEE,; Australia: 2010. A Review of Vision-Based Gait Recognition Methods for Human Identification; pp. 320–327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins R.T., Gross R., Jianbo Shi Silhouette-based human identification from body shape and gait. Proceedings of Fifth IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face Gesture Recognition, Washington, DC, USA: IEEE; 2002, p. 366–71. https://doi.org/10.1109/AFGR.2002.1004181.

- 20.Han J., Bhanu B. Individual recognition using gait energy image. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2006;28:316–322. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2006.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiqi Yu, Daoliang Tan, Tan Tieniu. 18th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR’06) IEEE,; Hong Kong, China: 2006. A Framework for Evaluating the Effect of View Angle, Clothing and Carrying Condition on Gait Recognition; pp. 441–444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee L., Grimson W.E.L. Proceedings of Fifth IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face Gesture Recognition. IEEE,; Washington, DC, USA: 2002. Gait analysis for recognition and classification; pp. 155–162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakkar N., Farid H. 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Nashville, TN. IEEE,; USA: 2021. On the Feasibility of 3D Model-Based Forensic Height and Weight Estimation; pp. 953–961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thakkar N., Pavlakos G., Farid H. Vol. 2022. IEEE,; New Orleans, LA, USA: 2022. The Reliability of Forensic Body-Shape Identification; pp. 44–52. (IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW)). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garreau G., Andreou C.M., Andreou A.G., Georgiou J., Dura-Bernal S., Wennekers T., et al. 2011 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), San Diego, CA. IEEE,; USA: 2011. Gait-based person and gender recognition using micro-doppler signatures; pp. 444–447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang Y., Wang Q., Yang Y., Hou C., He Y., Xu J. Person identification with limited training data using radar micro‐Doppler signatures. Micro Opt Tech Lett. 2020;62:1060–1068. doi: 10.1002/mop.32125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandersmissen B., Knudde N., Jalalvand A., Couckuyt I., Bourdoux A., De Neve W., et al. Indoor Person Identification Using a Low-Power FMCW Radar. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens. 2018;56:3941–3952. doi: 10.1109/TGRS.2018.2816812. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao P., Xia W., Ye M., Zhang J., Zhou J. Radar‐ID: human identification based on radar micro‐Doppler signatures using deep convolutional neural networks. IET Radar, Sonar. 2018;12:729–734. doi: 10.1049/iet-rsn.2017.0511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vera Rodriguez R., Evans N., Lewis R., Favre B., Mason J.S. An Experimental Study On The Feasibility Of Footsteps As A Biometric 2007. https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.40356.

- 30.Orr R.J., Abowd G.D. Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM,; The Hague The Netherlands: 2000. The smart floor: a mechanism for natural user identification and tracking. CHI ’00; pp. 275–276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moustakidis S.P., Theocharis J.B., Giakas G. 2009 17th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation, Thessaloniki. IEEE,; Greece: 2009. Feature extraction based on a fuzzy complementary criterion for gait recognition using GRF signals; pp. 1456–1461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dikovski B., Madjarov G., Gjorgjevikj D. 2014 37th International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO) IEEE,; Opatija, Croatia: 2014. Evaluation of different feature sets for gait recognition using skeletal data from Kinect; pp. 1304–1308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park G., Lee K.M., Koo S. Uniqueness of gait kinematics in a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-94815-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanawongsuwan R., Bobick A. Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. CVPR 2001, vol. 2, Kauai, HI. IEEE Comput. Soc,; USA: 2001. Gait recognition from time-normalized joint-angle trajectories in the walking plane. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Świtoński A., Polański A., Wojciechowski K.W. Human identification based on the reduced kinematic data of the gait. 2011 7th Int Symp Image Signal Process Anal (ISPA) 2011:650–655. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Świtoński A., Polański A., Wojciechowski K. In: Advances Concepts for Intelligent Vision Systems - 13th International Conference, ACIVS 2011, Ghent, Belgium, August 22-25, 2011. Proceedings, vol. 6915. Blanc-Talon J., Kleihorst R., Philips W., Popescu D., Scheunders P., editors. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2011. Human Identification Based on Gait Paths; pp. 531–542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar P., Mukherjee S., Saini R., Kaushik P., Roy P.P., Dogra D.P. Multimodal Gait Recognition With Inertial Sensor Data and Video Using Evolutionary Algorithm. IEEE Trans Fuzzy Syst. 2019;27:956–965. doi: 10.1109/TFUZZ.2018.2870590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weich C., M. Vieten M. The Gaitprint: Identifying Individuals by Their Running Style. Sensors. 2020;20:3810. doi: 10.3390/s20143810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goffredo M., Bouchrika I., Carter J.N., Nixon M.S. Self-Calibrating View-Invariant Gait Biometrics. IEEE Trans Syst, Man, Cyber B. 2010;40:997–1008. doi: 10.1109/TSMCB.2009.2031091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koffman L., Zhang Y., Harezlak J., Crainiceanu C., Leroux A. Fingerprinting walking using wrist-worn accelerometers. Gait Posture. 2023;103:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2023.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hollman J.H., Watkins M.K., Imhoff A.C., Braun C.E., Akervik K.A., Ness D.K. A comparison of variability in spatiotemporal gait parameters between treadmill and overground walking conditions. Gait Posture. 2016;43:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S.J., Hidler J. Biomechanics of overground vs. treadmill walking in healthy individuals. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01380.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindsay T.R., Noakes T.D., McGregor S.J. Effect of treadmill versus overground running on the structure of variability of stride timing. Percept Mot Skills. 2014;118:331–346. doi: 10.2466/30.26.PMS.118k18w8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seifert A.-K., Grimmer M., Zoubir A.M. Doppler radar for the extraction of biomechanical parameters in gait analysis. IEEE J Biomed Health Inf. 2021;25:547–558. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2020.2994471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiles T.M., Mangalam M., Sommerfeld J.H., Kim S.K., Brink K.J., Charles A.E., et al. NONAN GaitPrint: An IMU gait database of healthy young adults. Sci Data. 2023;10:867. doi: 10.1038/s41597-023-02704-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MATLAB. MATLAB 2023.

- 47.Rstudio. R.: A language and environment for statistical computing 2022.

- 48.Eddelbuettel D., Sanderson C. RcppArmadillo: Accelerating R with high-performance C++ linear algebra. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2014;71:1054–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2013.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eddelbuettel D., Francois R., Bates D., Ni B., Sanderson C. RcppArmadillo: “Rcpp” Integration for the “Armadillo” Templated Linear Algebra Library 2023.

- 50.Ariyanto G., Nixon M.S. 2011 International Joint Conference on Biometrics (IJCB), Washington, DC. IEEE,; USA: 2011. Model-based 3D gait biometrics; pp. 1–7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hinchliffe C., Rehman R.Z.U., Branco D., Jackson D., Ahmaniemi T., Guerreiro T., et al. Identification of Fatigue and Sleepiness in Immune and Neurodegenerative Disorders from Measures of Real-World Gait Variability 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1010933404324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang C.-C., Lin C.-J. LIBSVM: A library for support vector machines. ACM Trans Intell Syst Technol. 2011;2 27:1-27:27. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chambers J.M., Hastie T., editors. Statistical models in S. Pacific Grove, Calif: Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software; 1992.

- 55.Zhang Y., Huang Y., Wang L., Yu S. A comprehensive study on gait biometrics using a joint CNN-based method. Pattern Recognit. 2019;93:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.patcog.2019.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kale A., Sundaresan A., Rajagopalan A.N., Cuntoor N.P., Roy-Chowdhury A.K., Kruger V., et al. Identification of Humans Using Gait. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13:1163–1173. doi: 10.1109/TIP.2004.832865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phillips P.J., Sarkar S., Robledo I., Grother P., Bowyer K. Object recognition supported by user interaction for service robots, vol. 1, Quebec City, Que. IEEE Comput. Soc,; Canada: 2002. The gait identification challenge problem: data sets and baseline algorithm; pp. 385–388. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bashir K., Tao Xiang, Shaogang Gong. Gait recognition using gait entropy image. 3rd International Conference on Imaging for Crime Detection and Prevention (ICDP 2009), London, UK: IET; 2009, p. P2–P2. https://doi.org/10.1049/ic.2009.0230.

- 59.Dantcheva A., Velardo C., D’Angelo A., Dugelay J.-L. Bag of soft biometrics for person identification: New trends and challenges. Multimed Tools Appl. 2011;51:739–777. doi: 10.1007/s11042-010-0635-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin B., Zhang S., Yu X. Gait Recognition via Effective Global-Local Feature Representation and Local Temporal Aggregation 2021.

- 61.Horst F., Mildner M., Schöllhorn W.I. One-year persistence of individual gait patterns identified in a follow-up study – A call for individualised diagnose and therapy. Gait Posture. 2017;58:476–480. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stenum J., Rossi C., Roemmich R.T. Two-dimensional video-based analysis of human gait using pose estimation. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seely R.D., Goffredo M., Carter J.N., Nixon M.S. In: Handbook of Remote Biometrics. Tistarelli M., Li S.Z., Chellappa R., editors. Springer London; London: 2009. View Invariant Gait Recognition; pp. 61–81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muaaz M., Mayrhofer R. Smartphone-Based Gait Recognition: From Authentication to Imitation. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2017;16:3209–3221. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2017.2686855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gafurov D. 2007 First IEEE International Conference on Biometrics: Theory, Applications, and Systems, Crystal City, VA. IEEE,; USA: 2007. Security Analysis of Impostor Attempts with Respect to Gender in Gait Biometrics; pp. 1–6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar R., Phoha V.V., Jain A. Vol. 2015. IEEE,; USA: 2015. Treadmill attack on gait-based authentication systems; pp. 1–7. (IEEE 7th International Conference on Biometrics Theory, Applications and Systems (BTAS), Arlington, VA). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jeon J., Kwon S., Lee Y., Hong J., Yu J., Kim J., et al. Influence of the Hawthorne effect on spatiotemporal parameters, kinematics, ground reaction force, and the symmetry of the dominant and nondominant lower limbs during gait. J Biomech. 2023;152 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2023.111555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Farhan S., Avalos M.A., Rosenblatt N.J. Variability of Spatiotemporal Gait Kinematics During Treadmill Walking: Is There a Hawthorne Effect? J Appl Biomech. 2023:1–6. doi: 10.1123/jab.2022-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Likens A.D., Mangalam M., Wong A.Y., Charles A.C., Mills C. Better than DFA? A Bayesian Method for Estimating the Hurst Exponent in Behavioral Sciences. ArXiv. 2023 arXiv:2301.11262v1. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buzzi U.H., Stergiou N., Kurz M.J., Hageman P.A., Heidel J. Nonlinear dynamics indicates aging affects variability during gait. Clin Biomech. 2003;18:435–443. doi: 10.1016/S0268-0033(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Azizi T. On the fractal geometry of gait dynamics in different neuro-degenerative diseases. Phys Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1016/j.phmed.2022.100050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dingwell J.B., Cusumano J.P. Nonlinear time series analysis of normal and pathological human walking. Chaos. 2000;10:848. doi: 10.1063/1.1324008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stergiou N., Harbourne R.T., Cavanaugh J.T. Optimal Movement Variability: A New Theoretical Perspective for Neurologic Physical Therapy. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2006;30:120–129. doi: 10.1097/01.NPT.0000281949.48193.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu Y., Zhang J., Wang C., Wang L. Multiple HOG templates for gait recognition. Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR2012), Japan: 2012, p. 2930–3.

- 75.Afilalo J., Eisenberg M.J., Morin J.-F., Bergman H., Monette J., Noiseux N., et al. Gait speed as an incremental predictor of mortality and major morbidity in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1668–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Artaud F., Singh‐Manoux A., Dugravot A., Tzourio C., Elbaz A. Decline in fast gait speed as a predictor of disability in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1129–1136. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perera S., Patel K.V., Rosano C., Rubin S.M., Satterfield S., Harris T., et al. Gait speed predicts incident disability: a pooled analysis. Gerona. 2016;71:63–71. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brach J.S., Studenski S.A., Perera S., VanSwearingen J.M., Newman A.B. Gait variability and the risk of incident mobility disability in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:983–988. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.9.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.

Supplementary material.