Abstract

Sequence analysis of the Lymantria dispar multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (LdMNPV) genome identified an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a 548-amino-acid (62-kDa) protein that showed 35% amino acid sequence identity with vaccinia virus ATP-dependent DNA ligase. Ligase homologs have not been reported from other baculoviruses. The ligase ORF was cloned and expressed as an N-terminal histidine-tagged fusion protein. Incubation of the purified protein with [α-32P]ATP resulted in formation of a covalent enzyme-adenylate intermediate which ran as a 62-kDa labeled band on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Loss of the radiolabeled band occurred upon incubation of the intermediate with pyrophosphate, poly(dA) · poly(dT)12–18, or poly(rA) · poly(dT)12–18, characteristics of a DNA ligase II or III. The protein was able to ligate a double-stranded synthetic DNA substrate containing a single nick and inefficiently ligated a 1-nucleotide (nt) gap but did not ligate a 2-nt gap. It was able to ligate short, complementary overhangs but not blunt-ended double-stranded DNA. In a transient DNA replication assay employing six plasmids containing the LdMNPV homologs of the essential baculovirus replication genes, a plasmid containing the DNA ligase gene was neither essential nor stimulatory. All of these results are consistent with the activity of type III DNA ligases, which have been implicated in DNA repair and recombination.

The Lymantria dispar multinucleocapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (LdMNPV) is a natural pathogen of the gypsy moth, a major insect pest in the northeastern United States and eastern Canada. It is a member of a diverse family of insect viruses, the Baculoviridae, which contain large, circular, supercoiled DNA genomes. Recently, the entire 161-kb LdMNPV genome has been sequenced and found to encode approximately 170 open reading frames (ORFs), many of which have no reported homologs in other well-characterized baculoviruses (25).

Analysis of the LdMNPV genome revealed an ORF encoding a protein with a high degree of homology with the ATP-dependent DNA ligases. Such ligase homologs are not present in the genomes of the Autographa californica nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV) or the Orgyia pseudotsugata nucleopolyhedrovirus (OpMNPV). The ATP-dependent DNA ligases belong to a superfamily of covalent nucleotidyltransferases which include both the ATP-dependent polynucleotide ligases and the GTP-dependent mRNA capping enzymes. The members of this superfamily are characterized structurally by a set of six short motifs conserved in sequence, order, and spacing (41). The DNA ligases catalyze the formation of phosphodiester bonds at single-strand breaks in double-stranded DNA (27, 29). This ligation step plays an essential role in DNA replication, DNA repair, and genetic recombination. Escherichia coli contains an essential DNA ligase which uses NAD+, rather than ATP, as a coenzyme (24). Both Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Drosophila melanogaster cells have been found to contain two distinct DNA ligases, while mammalian cells contain at least four, each encoded by separate genes (38, 45, 48, 49). ATP-dependent DNA ligase genes have been identified in animal viruses including vaccinia virus, fowlpox virus, and African swine fever virus, as well as in Paramecium bursaria Chlorella virus 1 (PBCV-1) and the T-even and T-odd bacteriophages (17, 28, 29). DNA ligase I is present at higher levels in rapidly dividing cells than in nonproliferating cells. Its main function appears to be the joining of Okazaki fragments during DNA synthesis (35, 46). On the other hand, DNA ligase II is more plentiful in nonproliferating cells and is induced by DNA-damaging agents, suggesting that it plays a role in DNA repair (7, 10). Mammalian cells also contain a DNA ligase III and a more recently described DNA ligase IV (45, 48). DNA ligases III and IV have been implicated in both DNA repair and recombination (16, 19, 39, 48).

In this report, we describe studies of the sequence and enzymatic activity of the LdMNPV ligase-like protein. Although it is likely that a DNA ligase is involved in baculovirus DNA replication, it is not among the six baculovirus-encoded genes shown to be essential for transient DNA replication in both AcMNPV and OpMNPV (1, 2, 23). Using plasmids containing homologs of the genes shown to be essential in other baculoviruses for transient DNA replication, we found that the DNA ligase homolog did not stimulate transient DNA replication, suggesting that its role may be in DNA repair or recombination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture cells.

The L. dispar (Ld652Y) cell line was propagated at 27°C in TNMFH medium (44) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin G (50 μg/ml; Whittaker Bioproducts), and amphotericin B (Fungizone; 500 ng/ml; Flow Gibco-BRL) as previously described (36).

Construction of cosmids and plasmids.

LdMNPV cosmids and the plasmid clone pDB112 were supplied by Jim Slavicek. The cosmids were constructed with partial PstI or ClaI digests of DNA from the LdMNPV clonal isolate Cl 5-6 cloned into the cosmid vector pHC79 (42). The pDB112 subclone of cosmid A contains the 9.5-kb BglII F fragment cloned into the BamHI site of pUC18 (see Fig. 1). A subclone of BglII F, containing the ligase ORF (nucleotides [nt] 21745 to 23391), was constructed by digesting pDB112 with HindIII and EcoRI and cloning the resulting 1.8-kb fragment into the HindIII-EcoRI sites of pBluescript KS(−) [pBKS(−)] (Stratagene, Inc.). In this clone, designated pLdlig, the bacterial T3 promoter of pBKS(−) is within 60 bp of the translational start site for the ligase gene. In order to allow further subcloning, PCR was used to introduce an NcoI site at the ATG of the ligase ORF and a HindIII site at the 3′ end, 144 bp downstream of the translation stop codon. The sequence of the 5′ primer was 5′-GCTTGTAACCATGGAGAACC-3′, and that of the 3′ primer was 5′-AGGAATTCAAGCTTCGCGCCAT-3′. With DNA from the pLdlig clone as a template, PCR was performed according to the GeneAmp PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) protocol. The sample was PCR amplified with one cycle of 5 min at 95°C and 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C followed by one cycle of 6 min at 72°C in a PTC-200 DNA Engine (MJ Research, Inc.). The resulting 1.8-kb PCR product was digested with HindIII and then partially digested with NcoI since the ligase ORF contains an internal NcoI site. The 1.8-kb fragment containing the entire ORF was gel purified and subcloned into two different NcoI-HindIII-cut expression vectors. One of these vectors, which has been previously described (13), contains seven histidine codons upstream of and in frame with the ATG of an NcoI site. The resulting seven-histidne N-terminal fusion construct was designated pHTlig. The other vector, which contains the AcMNPV ie-1 gene promoter upstream of an NcoI site, has been previously described (33). The clone resulting from insertion of the ligase ORF downstream of the ie-1 gene promoter in this vector was designated pExplig. DNA sequencing was done on the cloned PCR products to confirm that no mistakes were introduced during amplification and cloning.

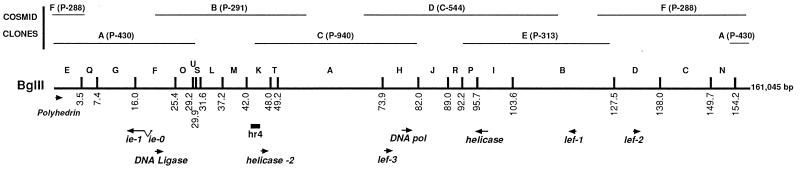

FIG. 1.

Location and orientation on the LdMNPV genome of genes implicated in DNA replication and repair. Each BglII site on the map is designated by a nucleotide number (in kilobases), and the locations of the cosmid clones are shown at the top. The polyhedrin gene, included for orientation, and the replication genes are shown below.

Plasmids containing the homologs of the six essential replication genes (see Fig. 1) were constructed as follows. The SstI-D fragment (nt 117145 to 119891) from cosmid E containing lef-1 (nt 118724 to 119428), an EcoRI-SacI fragment (nt 132200 to 134734) from cosmid F containing lef-2 (nt 132917 to 133567), and the SstI-F fragment (nt 74366 to 77076) from cosmid C containing lef-3 (nt 74856 to 75980) were subcloned into pBluescribe(−) to form plef-1, plef-2, and plef-3, respectively. Two SstI fragments spanning nt 77272 to 82938 containing portions of the DNA polymerase gene (nt 78389 to 81433) were ligated and cloned into SstI-cut pBluescribe(−) to make pDNApol. A 7.1-kb HindIII-H fragment (nt 91796 to 98839) of cosmid D containing the helicase gene (map unit 93899 to 97555) was subcloned into pBKS(−) to make phel. A clone, phel-2 (nt 46985 to 48677), containing a helicase-like ORF (nt 47126 to 48508) was constructed by cutting the 11.5-kb BamHI-G fragment with BamHI and EcoRV and cloning the resulting 2.8-kb fragment into pBKS(−). This clone was then cut with BamHI and SphI, blunted with T4 polymerase (37), and religated to give a 1.7-kb insert. Construction of pLdie-0, which contains the spliced LdMNPV ie-0 ORF under the control of the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter, and the reporter plasmid, pLdhr4, which contains the hr4 region, an in vitro origin of replication in LdMNPV, has been previously described (32, 33). Plasmids were propagated in E. coli DH5α and purified on Qiagen columns (Qiagen, Inc.).

Protein expression and purification.

In vitro transcription and translation (TnT) reactions were performed with a rabbit reticulocyte lysate TnT system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. TnT reaction mixtures were labeled with [35S]methionine (New England Nuclear). The N-terminal seven-His-tagged fusion construct of ligase, pHTlig, was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Novagen) followed by purification on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen).

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (37). Gels were either fixed and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (Bio-Rad) or dried and subjected to autoradiography. Quantitative analysis of gel bands was done with the Personal Densitometer SI and ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics, Inc.).

Ligase substrates.

The homopolymer oligonucleotide substrates, poly(dA) · poly(dT)12–18[oligo(dT) · poly(dA)] and poly(rA) · poly(dT)12–18 [oligo(dT) · poly(rA)], were purchased from Pharmacia. Ligase substrates consisting of a 36-bp duplex DNA containing a centrally placed nick, a 1-nt gap, or a 2-nt gap were synthesized and annealed as described by Ho et al. (17). Briefly, a 36-mer acceptor strand with the sequence 5′-TGTAGTCACTATCGGAATAAGGGCGACACGGATATG-3′ was annealed to a 5′-end-labeled 18-mer donor strand with the complementary sequence 5′-ATTCCGATAGTGACTACA-3′ and one of three complementary acceptor 18-mer strands. The acceptor strand 5′-CATATCCGTGTCGCCCTT-3′ introduces a nick in the DNA duplex, while acceptor strands 5′-ACATATCCGTGTCGCCCT-3′ and 5′-AACATATCCGTGTCGCCC-3′ introduce a 1-nt and a 2-nt gap, respectively (see Fig. 5a). The 18-mer donor strand was 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP with T4 polynucleotide kinase as previously described (5). The labeled oligonucleotide was purified away from unincorporated label on a TE Micro Select-D, G-25 spin column (5 Prime→3-Prime, Inc.). The labeled donor 18-mer, complementary 36-mer, and acceptor 18-mer, in 2 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3)–0.25 M KCl, at a molar ratio of 1:3:6, were annealed by heating at 65°C for 2 min and slow cooling to room temperature. For other experiments, complementary sticky or blunt-ended substrates were produced by linearization of pBKS(−) with either HindIII or SmaI, respectively.

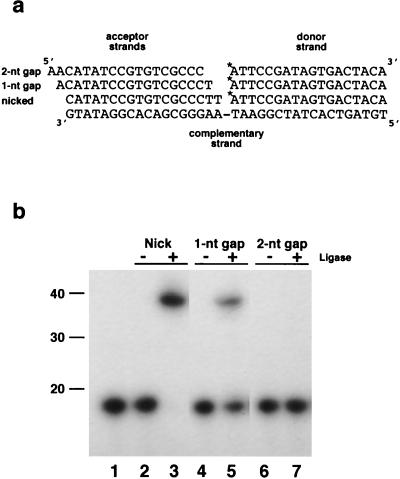

FIG. 5.

Ligation activity of LdMNPV ligase on three synthetic double-stranded DNA substrates. (a) The end-labeled (indicated by the asterisk) donor 18-mer and the three acceptor 18-mers are shown relative to the 36-mer complementary strand (adapted from the work of Ho et al. [17]). Duplex substrates were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. (b) A standard reaction mixture (20 μl) containing unlabeled ATP and 0.9 pmol of 32P-labeled DNA substrate, containing either a nick, a 1-nt gap, or a 2-nt gap, with or without 50 ng of ligase was incubated at 20°C for 30 min and subjected to electrophoresis on a 12.5% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel. The results shown are as follows: lane 1, 32P-5′-end-labeled 18-mer donor strand; lanes 2 and 3, nicked substrate without (lane 2) or with (lane 3) ligase; lanes 4 and 5, 1-nt-gap substrate without (lane 4) or with (lane 5) ligase; lanes 6 and 7, 2-nt-gap substrate without (lane 6) or with (lane 7) ligase. The locations of the 10-bp-ladder (Gibco BRL) size standards are indicated on the left in base pairs.

Formation of ligase-AMP complex.

A standard reaction mixture (40 μl) containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 0.5 μCi of [α-32P]ATP, and ligase was incubated for 15 min at room temperature (30). Analysis of the radiolabeled enzyme-adenylate intermediate (ligase-AMP) was performed by incubating 10-μl aliquots of this mixture with either 10 nmol of sodium pyrophosphate or 0.8 μg of each of the homopolymer oligonucleotide substrates at room temperature for 1 h. Reactions were terminated by addition of 10 μl of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer (37), resolved on SDS–10% PAGE gels, dried, and analyzed by autoradiography.

Ligation assays.

Ligation reactions (20 μl) were initiated by addition of enzyme to reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 50 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 1 mM ATP) containing 0.9 pmol of 32P-labeled DNA substrate, reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and reactions were stopped by addition of 1 μl of 0.5 M EDTA–5 μl of formamide. The reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis on 12.5% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gels, followed by exposure to X-ray film.

Ligation of DNA molecules with complementary sticky or blunt ends was performed by incubation of restriction enzyme-cleaved pBKS(−) with ligase in reaction buffer (described above) for various periods of time. The resulting products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of ethidium bromide.

Plasmid replication assay.

DNA replication assays were performed as previously described (33). Briefly, total DNA was collected from uninfected Ld652Y cells 72 h after transfection with cosmids and plasmids. A DpnI-based assay was then used to detect replication of the reporter plasmid, pLdhr4. Samples were digested with DpnI (34) and with PstI, which linearizes the reporter plasmid, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis and Southern blotting. Detection of bands was accomplished by a chemiluminescence method using fluorescein-labeled pBKS(−), polyclonal antifluorescein antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, and a nucleic acid chemiluminescent substrate according to the manufacturer’s instructions (NEN Research Products, Boston, Mass.).

DNA sequence analysis.

Sequence reactions were performed with the Taq Dye-Deoxy Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.) as previously described (33). The nucleotide sequences and predicted protein sequences were analyzed with the GCG suite of sequence analysis programs (11), version 9-UNIX (1996). Database searches were done with the BLAST protocol (3).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence numbers reported in this paper will appear in the GSDB, DDBJ, EMBL, and NCBI nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AF081810.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of the ligase-like fusion protein.

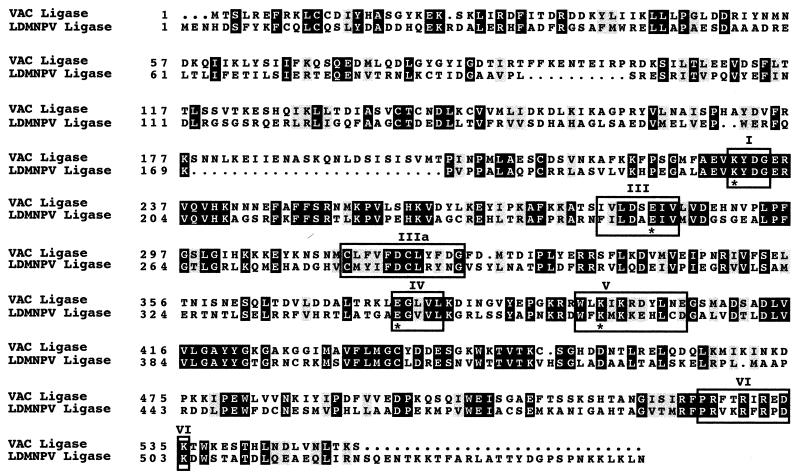

Sequence analysis of the entire 161,045-bp LdMNPV genome (25) led to the identification of an ORF located just upstream of the ie-0 ORF at nt 21745 to 23391 (Fig. 1), which is 35% identical, at the amino acid level, to vaccinia virus DNA ligase III. It shows a similar degree of homology to several mammalian DNA ligase III proteins, including human and mouse proteins. However, at 548 amino acids (aa) in length, it is much closer in size to vaccinia virus (552 aa) than to either human (862 aa) or mouse alpha (1,015 aa) and beta (956 aa) DNA ligases III. The predicted protein product of the LdMNPV ligase-like gene contains six motifs which are conserved in both order and spacing in the cellular and viral ATP-dependent DNA ligases (Fig. 2) (41). In addition, it also contains four residues, at aa 198, 250, 345, and 365 (Fig. 2, asterisks), which have been found to be essential for activity of vaccinia virus DNA ligase, including the reactive lysine (aa 198) that is located in the active site (Fig. 2, motif I) (40). We undertook a series of experiments to determine if the product of this ORF is indeed an active ligase. Initially, we subcloned the ligase ORF into pBKS(−) so that the ATG was within 60 bp of the T3 promoter. In vitro TnT reactions with this pLdlig clone as a template yielded a product of approximately 62 kDa, the size estimated from the predicted amino acid sequence (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of vaccinia virus (VAC) and LdMNPV DNA ligases. The six conserved sequence motifs comprising the catalytic domain are boxed and designated I, III, IIIa, IV, V, and VI. Identical amino acids are indicated by white letters within black boxes, and similar amino acids are denoted by shaded boxes. Dots indicate gaps. Amino acid numbers are indicated on the left. Asterisks designate the amino acids in the vaccinia virus DNA ligase that have been determined to be essential for activity of the enzyme (40). The vaccinia virus sequence accession no. is U94848.

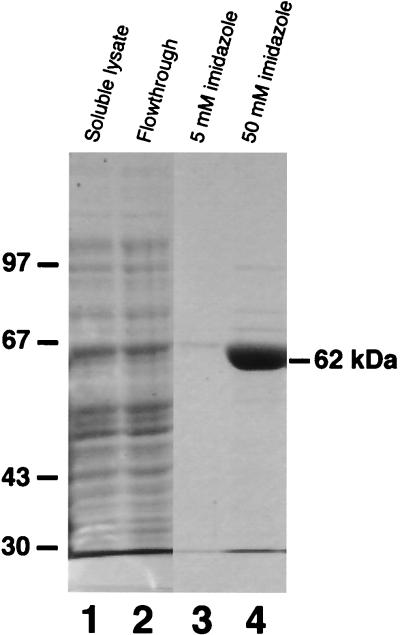

In order to allow production of the putative ligase protein in a bacterial expression system, PCR was used to amplify the ORF contained in pLdlig and to introduce an NcoI site at the ATG. The resulting product was then cloned into an expression vector in frame with seven upstream histidine codons to produce pHTlig. Following expression of this plasmid in bacterial cells, SDS-PAGE analysis of collected fractions during the subsequent purification steps showed that a band at about 62 kDa was concentrated by the Ni-NTA resin and eluted upon application of 50 mM imidazole (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 4).

FIG. 3.

Expression and purification of the LdMNPV recombinant ligase. After expression of the DNA ligase gene in bacterial cells, cell lysates were applied to the Ni-NTA resin, washed four times, and eluted with 5 and 50 mM imidazole. SDS-PAGE analysis of the collected protein fractions includes the following: lane 1, soluble cell lysate; lane 2, Ni-NTA resin flowthrough; lane 3, 5 mM imidazole eluate; and lane 4, 50 mM imidazole eluate. The gel was fixed and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The sizes in kilodaltons of the marker proteins electrophoresed with the samples are indicated on the left.

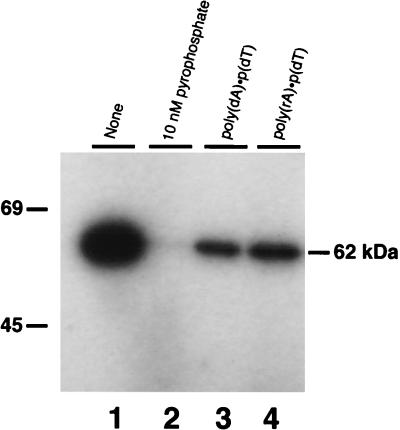

Formation and properties of a protein-adenylate intermediate.

The first step in DNA ligation involves interaction of the enzyme with ATP, resulting in the formation of a covalent ligase-adenylate intermediate, in which the reactive lysine (Fig. 2, aa 198) in the active site is covalently linked to AMP. To determine if the purified, bacterially expressed His-tagged protein has this activity, the 50 mM imidazole elution fraction was incubated with [α-32P]ATP. This resulted in the formation of a labeled protein which migrated at 62 kDa in SDS-PAGE gels (Fig. 4, lane 1). The first preelution wash fraction did not yield any labeled bands, indicating that the 62-kDa band was not attributable to nonspecifically bound E. coli ligase (data not shown). This result is as expected, since the E. coli ligase uses NAD+ as a coenzyme, rather than ATP, and so would not be active in this assay. Removal of the AMP group from the ligase intermediate occurs in the presence of pyrophosphate, which causes a reversal of the reaction and regeneration of ATP. Incubating the AMP-His-tagged protein intermediate with pyrophosphate resulted in the release of the [α-32P]AMP and consequent disappearance of the labeled band (Fig. 4, lane 2). In addition, incubation of the intermediate with the polynucleotide substrates oligo(dT) · poly(dA) or oligo(dT) · poly(rA) also resulted in the release of labeled AMP. These substrates consist of a 12- to 18-nt dT oligomer primer annealed with a long poly(dA) or poly(rA) oligonucleotide template forming nicked DNAs which may serve as acceptors for the adenylate group. The labeled band was reduced by 71.6% after incubation with oligo(dT) · poly(dA) and by 63.2% following incubation with oligo(dT) · poly(rA) (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4). These results indicate that the His-tagged protein can react with [α-32P]ATP to form a protein-adenylate complex and that this reaction is reversed upon incubation of the intermediate with pyrophosphate. In the presence of oligo(dT) · poly(dA) or oligo(dT) · poly(rA), the label also is released from the protein, indicating transfer of the AMP group to both these substrates. All of these results are characteristic of ligase-adenylate intermediates.

FIG. 4.

Formation and reactivity of the enzyme-adenylate complex. A standard reaction mixture (40 μl) containing [α-32P]ATP and 100 ng of recombinant ligase was incubated at 20°C for 15 min. Aliquots (10 μl) of this enzyme-adenylate intermediate were then incubated for 1 h longer with various substrates as follows: lane 1, no addition; lane 2, 10 nmol of sodium pyrophosphate; lane 3, 0.8 μg of poly(dA) · poly(dT)12–18 and lane 4, 0.8 μg of poly(rA) · poly(dT)12–18. Samples were resolved on an SDS–10% PAGE gel, dried, and subjected to autoradiography. The sizes in kilodaltons of prestained marker proteins included on the gel are indicated on the left.

Ligation of DNA substrates.

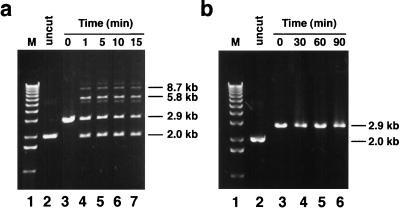

In the next step of the ligation reaction, the AMP group covalently bound to the enzyme is transferred to the 5′-phosphoryl residue present at a single strand break in double-stranded DNA. This DNA-AMP complex is also a covalent intermediate but is much less stable than the enzyme-adenylate intermediate. The pyrophosphate bond formed between the phosphoryl group and AMP provides the energy needed for the enzyme catalyzation of phosphodiester bond formation, resulting in sealing of the DNA break and release of the AMP. DNA ligases can seal single-strand nicks in DNA but join 1- and 2-nt gaps much less efficiently, if at all. In order to assay the ligation ability of the purified fusion protein, we utilized three synthetic duplex DNA substrates as described by Ho et al. (17). These substrates consisted of a 36-mer complementary strand annealed with a 5′-end-labeled 18-mer donor strand and one of three 18-mer acceptor strands such that the resulting duplex contains either a single-strand nick or a 1- or 2-nt gap. Each of these substrates was incubated with various concentrations of the purified fusion protein in the presence of unlabeled ATP. The His-tagged protein was able to seal a single nick in a synthetic duplex DNA as evidenced by the appearance of a labeled 36-mer product (Fig. 5; compare lanes 2 and 3). The fusion protein was also able to seal a nick in the absence of added ATP (data not shown), indicating that some of the protein already exists in the adenylated state, an observation that has been made with other ligase proteins (17).

The recombinant protein was able to seal a 1-nt gap, but less efficiently than a nick, with only a portion of the substrate converted to labeled 36-mer (Fig. 5; compare lanes 4 and 5 to lanes 2 and 3). This repair of 1-nt gaps was not seen at a lower protein concentration (5 ng), which was still adequate for sealing nicks (data not shown). At much higher protein concentrations (500 ng), a small amount of the less stable, slower-migrating DNA-adenylate intermediate was detected (data not shown). Like other ligases that have been described previously, the His-tagged protein was incapable of sealing DNA single-strand breaks across a 2-nt gap (Fig. 5, lanes 6 and 7).

The ability of the His-tagged ligase to join DNA molecules with complementary sticky or blunt ends was assayed by using plasmid DNA cut with either HindIII, which generates sticky ends, or SmaI, which produces blunt ends. The enzyme ligated DNA molecules with short complementary overhangs (Fig. 6a, lanes 4 to 7). Most of the ligation that occurred was complete within 5 min after addition of enzyme (Fig. 6a, lanes 4 and 5). The ligation reaction produced a religated single molecule that migrated as a 2.0-kb band, as well as double and triple end-to-end ligated molecules of 5.8 and 8.7 kb, respectively (Fig. 6a, lanes 4 to 7). Uncut, supercoiled plasmid (Fig. 6, lane 2) migrates at the same size as the 2.0-kb single religated molecules due to relaxation of the supercoils caused by ethidium bromide intercalation. A small amount of ligation product larger than 8.7 kb was also present. A residual amount of the 2.9-kb linear plasmid DNA was present throughout the incubation period (Fig. 6a, lanes 4 to 7). Increasing the amount of ligase to 1.2 μg and extending the incubation time to 2 h did not result in further conversion of this unligated DNA to ligated forms (data not shown). Incubating blunt-ended DNA molecules with 1.2 μg of ligase for up to 1.5 h did not yield any detectable ligation products (Fig. 6b, lanes 3 to 6).

FIG. 6.

Ligation of plasmid molecules containing short complementary or blunt ends by LdMNPV DNA ligase. (a) HindIII-cut pBKS(−), containing short complementary overhangs, was incubated without or with 100 ng of ligase for various times as indicated: lane 1, 1-kb ladder (Gibco BRL); lane 2, uncut plasmid; lane 3, no ligase; lane 4, 1 min; lane 5, 5 min; lane 6, 10 min; lane 7, 15 min. (b) SmaI-cut blunt-ended pBKS(−) was incubated without or with 1.2 μg of LdMNPV ligase for various times and resolved on an agarose gel as described above. The results are as follows: lane 1, 1-kb ladder; lane 2, uncut plasmid; lane 3, no ligase; lane 4, 30 min; lane 5, 60 min; lane 6, 90 min. DNA was electrophoresed through a 0.8% agarose gel in the presence of ethidium bromide. The sizes in kilobases of the resulting DNA molecules are indicated on the right of each panel.

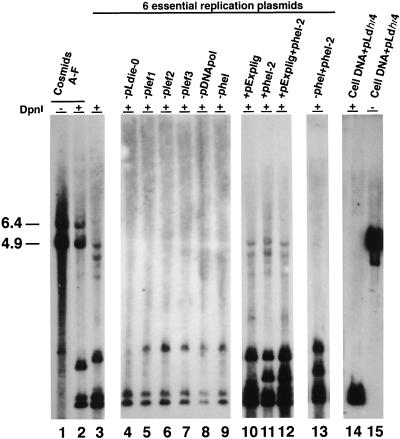

The influence of the LdMNPV ligase on transient DNA replication.

Replication of double-stranded DNA requires the participation of a ligase which joins the Okazaki fragments on the lagging DNA strand. However, a ligase was not among the six genes required for transient AcMNPV and OpMNPV DNA replication (1, 2, 23), suggesting that the ligase is supplied by the host cells in these systems. To determine if the LdMNPV-encoded DNA ligase is involved in viral DNA replication, we identified and cloned the LdMNPV homologs (Fig. 1) of the essential baculovirus replication genes (DNA polymerase, p143-helicase, lef-1, lef-2, lef-3, and ie-1).

The six overlapping cosmids (Fig. 1) representing the entire LdMNPV genome can support replication of an origin-containing plasmid, pLdhr4, in such a transient assay (33). Identification and subcloning of the LdMNPV homologs of the six essential replication genes allowed us to determine if these genes could support transient DNA replication. The six cosmids or various combinations of plasmids were cotransfected with the pLdhr4 reporter plasmid into Ld652Y cells, and the replication of the reporter was assessed by a DpnI-based assay (31, 34). The results of these experiments are shown in Fig. 7. As previously reported, cotransfection of all six cosmids (A to F) supported replication of the reporter, seen as the 4.9-kb DpnI-resistant band in lane 2 (33). In addition, a 6.4-kb DpnI-resistant band which is due to replication of the cosmid vector, pHC79, is also seen (33). Replacing the cosmids with the six plasmids containing the replication gene homologs also supported replication of the origin-containing reporter plasmid (Fig. 7, lane 3). Omitting each of the replication gene homologs, individually, abolished replication (Fig. 7, lanes 4 to 9). These results suggest that the replication gene homologs identified in the LdMNPV genome are essential for transient DNA replication.

FIG. 7.

Transient replication assay using the LdMNPV cosmids or the plasmids containing the six essential replication genes, DNA ligase, and helicase-2. The cosmids or combinations of clones cotransfected along with the LdMNPV hr4-containing reporter plasmid, pLdhr4, into uninfected Ld652Y cells are shown above each lane and include the following: lanes 1 and 2, cosmids A to F without (lane 1) and with (lane 2) DpnI; lane 3, plasmids containing the six essential replication genes; lanes 4 to 9, omission of each essential replication gene as indicated above the individual lanes; lanes 10 to 12, the six essential replication genes plus ligase (lane 10), helicase-2 (lane 11), or both (lane 12); lane 13, substitution of helicase-2 for helicase; and lanes 14 and 15, DpnI digestion controls consisting of uninfected Ld652Y cell DNA mixed with 0.003 μg of the pLdhr4 reporter plasmid DNA and digested with (lane 14) or without (lane 15) DpnI. The sizes (in kilobases) of the linearized pLdhr4 reporter plasmid and pHC79 cosmid vector are indicated to the left of the blot.

To determine if the DNA ligase gene affected transient replication, a plasmid, pExplig, containing the ligase ORF under the control of the AcMNPV ie-1 promoter to ensure expression of the protein in L. dispar cells, was cotransfected with the six essential replication genes in a transient replication assay. The ligase gene product did not appear to stimulate replication of the reporter plasmid above the levels seen with the six essential genes alone (Fig. 7; compare lane 10 to lane 3). To confirm that the LdMNPV ligase protein is expressed under the conditions of this experiment, an extract of pExplig-transfected L. dispar cells was incubated with [α-32P]ATP and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A labeled band of 62 kDa was present in transfected, but not in control, cell extracts, indicating that the LdMNPV ligase is expressed and active in cells transfected with the pExplig plasmid (data not shown). One other labeled band, of approximately 100 kDa, which was present in both transfected and control cell extracts, is presumably due to the host cell ligase (data not shown).

In addition to DNA ligase, our survey of the LdMNPV genome identified an ORF (helicase-2) with homology to the petite integration frequency 1 (PIF1) gene in S. cerevisiae which might also affect replication (Fig. 1). PIF1 is a 5′-to-3′ helicase which is involved in repair and recombination of mitochondrial DNA (15, 26). This suggested the possibility that this gene might be acting in conjunction with the ligase gene to influence DNA replication. Therefore, a plasmid, phel-2, containing the PIF1 homolog and its 5′ and 3′ flanking regions, was constructed (Fig. 1). Cotransfection of this plasmid together with the six essential genes did not result in stimulation of replication (Fig. 7; compare lanes 11 and 3). Cotransfection of both phel-2 and pExplig along with the six replication genes also did not stimulate an increase in transient replication above that seen with the six replication genes alone (Fig. 7; compare lanes 12 and 3). In addition, we tested the ability of the hel-2 gene to substitute for the essential helicase replication gene. No replication was observed when phel was replaced with phel-2 (Fig. 7; compare lanes 3, 9, and 13). The controls show that pLdhr4 plasmid DNA mixed with uninfected Ld652Y cell DNA and treated with (Fig. 7, lane 14) and without (Fig. 7, lane 15) DpnI is completely digested under the experimental conditions used. Additional controls showed that the probe did not hybridize with uninfected cell DNA and that the reporter plasmid did not replicate in the absence of the essential replication genes (data not shown). These data suggest that neither the LdMNPV DNA ligase nor the gene with features of a helicase is involved in transient DNA replication.

DISCUSSION

Sequence analysis of the entire LdMNPV genome identified a gene encoding a protein with significant homology to a variety of DNA ligases. Ligase homologs are not present in AcMNPV or OpMNPV. The DNA ligases belong to a superfamily of covalent nucleotidyltransferases which include the polynucleotide ligases and the mRNA capping enzymes. These proteins show a wide variation in size, ranging from 298 aa for PBCV-1 DNA ligase, the smallest described thus far, to 900 to 1,000 aa for some of the mammalian DNA ligases (17, 48). However, these proteins all contain a catalytic domain which includes six motifs that are conserved in both sequence and spacing (Fig. 2) (41). The LdMNPV DNA ligase gene product contains these six motifs with spacing identical to that of vaccinia virus DNA ligase, except for the distance between motifs IIIa and IV, where the LdMNPV ligase contains an additional amino acid. The motifs themselves are also conserved, including the residues which have been found to be essential for enzyme activity in vaccinia virus (Fig. 2). The active site itself contains a presumptive reactive lysine residue in the sequence E-KYDG-R which is common to these enzymes from a wide range of organisms including bacteriophages, yeasts, and humans (29). In the ligase proteins, large portions of the regions N terminal and C terminal to the catalytic domain can be deleted without a subsequent loss in enzymatic activity. Since the PBCV-1 DNA ligase contains only 26 aa upstream of the lysine in motif I at the N terminus and no amino acids downstream of motif VI at the C terminus, it has been suggested that it might represent the catalytic core of the nucleotidyltransferase superfamily (18). Thus, the DNA ligases have significant homology in the catalytic domain but often show much less homology in both sequence and length of the N and C termini (Fig. 2).

BLAST searches of the database with LdMNPV ligase produced the most optimal alignments with homologs from mammals and members of the family Poxviridae. This may reflect a paucity of insect ligases in the database, or it could also suggest that the LdMNPV ligase was acquired from a poxvirus. This acquisition might have occurred via genetic exchange with members of the Entomopoxvirinae, a subfamily of poxviruses that infect insects. In particular, genus B of the entomopoxviruses (EPVs) infects members of the Lepidoptera, as do baculoviruses. It is, therefore, possible that LdMNPV may have acquired the DNA ligase gene either directly or indirectly from an EPV. Thus far, a DNA ligase gene has not been identified in EPV, but complete sequence data is not yet available for Amsacta moorei EPV, the most-studied member of this family (29a).

At least four distinct DNA ligases have been described for mammalian cells, with a fifth having been recently identified in human cells (20, 45, 48). These enzymes can be distinguished by differences in their catalytic properties, which have also been exploited to purify them from one another (45). DNA ligase I is active on the synthetic substrate poly(dA) · poly(dT)12–18 but not on poly(rA) · poly(dT)12–18. On the other hand, DNA ligases II and III are active on both these substrates. Our experimental results with the purified, recombinant LdMNPV DNA ligase demonstrate that it can covalently bind AMP and that this reaction is reversed by the addition of pyrophosphate (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2). In addition, the radiolabeled AMP is released upon incubation of the ligase-adenylate intermediate with the synthetic substrates poly(dA) · poly(dT)12–18 and poly(rA) · poly(dT)12–18, implying that ligation of the poly(dT)12–18 oligomer is occurring (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4). It was also able to efficiently repair single-strand nicks in synthetic duplex DNA (Fig. 5) and ligate HindIII-cut plasmid DNA (Fig. 6a); however, it was unable to ligate blunt-ended DNA (Fig. 6b). Collectively, these are characteristics of type III DNA ligases (12). Therefore, these results indicate that the LdMNPV ligase gene homolog does encode an active protein that behaves like an ATP-dependent DNA ligase and suggest that it is a type III ligase.

The type I DNA ligases have been implicated in DNA replication based on a variety of observations, including the fact that they are greatly increased in proliferating cells compared to nonproliferating cells. In addition, substitution experiments have shown that a cDNA containing human DNA ligase I can compensate for a defective S. cerevisiae DNA ligase (4, 29). The main function of DNA ligase I appears to be the joining of Okazaki fragments during lagging-strand DNA synthesis (24, 46). On the other hand, DNA ligases II and III are more plentiful in nonproliferating cells than in dividing cells and are implicated in DNA repair and genetic recombination (6, 7, 10, 19). Replication by vaccinia virus deletion mutants lacking the DNA ligase gene was indistinguishable from wild-type virus replication (9, 22). Experiments using plasmids containing the homologs of the six essential baculovirus replication genes, DNA polymerase, helicase, ie-0, lef-1, lef-2, and lef-3, indicate that they are required and sufficient for transient replication of a reporter plasmid (Fig. 7, lanes 1 to 9). These results suggest that, as is the case with vaccinia virus, the LdMNPV DNA ligase gene is also not an essential replication gene. The LdMNPV genome contains an ORF (helicase-2) with homology to a yeast 5′-to-3′ DNA helicase, PIF1, which is required for both repair and recombination of mitochondrial DNA (15, 26). Clones containing the ligase and helicase-2 ORFs were tested both individually and together for their effect on DNA replication. No effect was observed in any of these experiments (Fig. 7, lanes 10 to 12). The fact that LdMNPV has maintained a well-conserved, active DNA ligase suggests that this protein may be important to the virus life cycle. Since our results indicate that the ligase does not appear to play a direct role in DNA replication in a tissue culture-based assay, it is possible that it functions in repair of UV or other environmentally induced DNA damage and perhaps in genetic recombination. The vaccinia virus ligase has been implicated in DNA repair, since mutant viruses lacking the ligase gene show increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents (9, 21). In somatic cells, DNA ligase III has been shown to function in both DNA repair and recombination (6, 8, 19). The PIF1 helicase-like ORF could also play a role in these processes in LdMNPV.

The fact that LdMNPV has acquired and conserved two genes, DNA ligase and a PIF1-like helicase, which are not present in the related viruses, AcMNPV and OpMNPV, presents the possibility that these genes may play a unique role in the life cycle of this virus. Although the specific function of DNA ligase III is not known, it appears that it may primarily be involved in sealing DNA strand breaks resulting from meiotic recombination in germ cells or DNA damage in somatic cells (8). The PIF1 gene is required for repair of mitochondrial DNA and is also required in a recombination system which depends on recognition of palindromic sequences (14, 15, 43, 47). The LdMNPV genome has 13 homologous regions, consisting of repeated sequences, containing both direct repeats and imperfect palindromes, located throughout the genome (32, 25), raising the possibility that the proteins encoded by the DNA ligase and PIF1 genes may participate in recombination involving these sequences. Recombination could be a mechanism for the production of viable genomes from multiple copies of damaged genomes entering the cell by infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank James Slavicek for the LdMNPV cosmids and the pDB112 plasmid. We also thank Christian Gross, Dale Mosbaugh, and Douglas Leisy for helpful suggestions and criticisms of the manuscript.

This project was supported by grants from the United States Department of Agriculture (95-37302-1920) and the National Science Foundation (9630769-MCB).

Footnotes

Technical report no. 11403 from the Oregon State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahrens C, Rohrmann G F. Replication of Orgyia pseudotsugata baculovirus DNA: Ie-1 and lef-2 are essential and ie-2, p34 and op-iap are stimulatory genes. Virology. 1995;212:650–662. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrens C A, Leisy D J, Rohrmann G F. Baculovirus DNA replication. In: De Pamphilis M, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 855–872. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes D E, Johnston L H, Kodama K, Tomkinson A E, Lasko D D, Lindahl T. Human DNA ligase I cDNA: cloning and functional expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6679–6683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blissard G W, Rohrmann G F. Location, sequence, transcriptional mapping, and temporal expression of the gp64 envelope glycoprotein gene of the Orgyia pseudotsugata multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1989;170:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caldecott K W, McKeown J D, Tucker J D, Ljungquist S, Thompson L H. An interaction between the mammalian DNA repair protein XRCC1 and DNA ligase III. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:68–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan J Y, Thompson L H, Becker F F. DNA ligase activities appear normal in the CHO mutant EM9. Mutat Res. 1984;131:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(84)90027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, Tomkinson A E, Ramos W, Mackey Z B, Danehower S, Walter C A, Schultz R A, Besterman J M, Husain I. Mammalian DNA ligase III: molecular cloning, chromosomal localization, and expression in spermatocytes undergoing meiotic recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5412–5422. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colinas R J, Goebel S J, Davis S W, Johnson G P, Norton E K, Paoletti E. A DNA ligase gene in the copenhagen strain of vaccinia virus is nonessential for viral replication and recombination. Virology. 1990;179:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creissen D, Shall S. Regulation of DNA ligase activity by poly(ADP-ribose) Nature (London) 1982;296:271–272. doi: 10.1038/296271a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elder R H, Montecucco A, Ciarrocchi G, Rossignol J M. Rat liver DNA ligases. Catalytic properties of a novel form of DNA ligase. Eur J Biochem. 1992;203:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb19826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans J T, Rohrmann G F. The baculovirus single-stranded DNA binding protein, LEF-3, forms a homotrimer in solution. J Virol. 1997;71:3574–3579. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3574-3579.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foury F, Kolodynski J. PIF mutation blocks recombination between mitochondrial rho+ and rho− genomes having tandemly arrayed repeat units in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:5345–5349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.17.5345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foury F, Lahaye A. Cloning and sequencing of the PIF gene involved in repair and recombination of yeast mitochondrial DNA. EMBO J. 1987;6:1441–1449. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grawunder U, Wilm M, Wu X, Kulesza P, Wilson T E, Mann M, Leiber M R. Activity of DNA ligase IV stimulated by complex formation with XRCC4 protein in mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;388:492–495. doi: 10.1038/41358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho C K, Van Etten J L, Shuman S. Characterization of an ATP-dependent DNA ligase encoded by Chlorella virus PBCV-1. J Virol. 1997;71:1931–1937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1931-1937.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho S N, Hund H D, Morton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jessberger R, Podust V, Hubscher U, Berg P. A mammalian protein complex that repairs double-strand breaks and deletions by recombination. J Biol Chem. 1993;265:15070–15079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson A P, Fairman M P. The identification and purification of a novel mammalian DNA ligase. Mutat Res. 1997;383:205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(97)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerr S M, Johnston L H, Odell M, Duncan S A, Law K M, Smith G L. Vaccinia virus DNA ligase complements Saccharomyces cerevisiae cdc9, localizes in cytoplasmic factories and affects virulence and virus sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. EMBO J. 1991;10:4343–4350. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerr S M, Smith G L. Vaccinia virus DNA ligase is nonessential for virus replication: recovery of plasmids from virus-infected cells. Virology. 1991;180:625–632. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90076-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kool M, Ahrens C H, Vlak J M, Rohrmann G F. Replication of baculovirus DNA. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2103–2118. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman & Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuzio, J., M. N. Pearson, S. H. Harwood, C. J. Funk, J. T. Evans, J. M. Slavicek, and G. F. Rohrmann. Sequence and analysis of the genome of a baculovirus pathogenic for Lymantria dispar. Virology, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Lahaye A, Stahl H, Thines S D, Foury F. PIF1: a DNA helicase in yeast mitochondria. EMBO J. 1991;10:997–1007. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lehman I R. DNA ligase: structure, mechanism, and function. Science. 1974;186:790–797. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4166.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Y, Passarelli A L, Miller L K. Identification, sequence, and transcriptional mapping of lef-3, a baculovirus gene involved in late and very late gene expression. J Virol. 1993;67:5260–5268. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5260-5268.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindahl T, Barnes D E. Mammalian DNA ligases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:251–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a.Moyer, R. W. Personal communication.

- 30.Nash R, Lindahl T. DNA ligases. In: De Pamphilis M, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 575–586. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearson M N, Bjornson R M, Ahrens C, Rohrmann G F. Identification and characterization of a putative origin of DNA replication in the genome of a baculovirus pathogenic for Orgyia pseudotsugata. Virology. 1993;197:715–725. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson M N, Rohrmann G F. Lymantria dispar nuclear polyhedrosis virus homologous regions: characterization of their ability to function as replication origins. J Virol. 1995;69:213–221. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.213-221.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson M N, Rohrmann G F. Splicing is required for transactivation by the immediate early gene 1 of the Lymantria dispar multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus. Virology. 1997;235:153–165. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peden K W C, Pipas J M, Pearson-White S, Nathans D. Isolation of mutants of an animal virus in bacteria. Science. 1980;209:1392–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.6251547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prigent C, Satoh M S, Daly G, Barnes D E, Lindahl T. Aberrant DNA repair and DNA replication due to an inherited enzymatic defect in human DNA ligase I. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:310–317. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quant-Russell R L, Pearson M N, Rohrmann G F, Beaudreau G S. Characterization of baculovirus p10 synthesis using monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1987;160:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schar P, Herrmann G, Daly G, Lindahl T. A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1912–1924. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.15.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sekiguchi J, Shuman S. Nick sensing by vaccinia virus DNA ligase requires a 5′ phosphate at the nick and occupancy of the adenylate binding site on the enzyme. J Virol. 1997;71:9679–9684. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9679-9684.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shuman S, Ru X M. Mutational analysis of vaccinia DNA ligase defines residues essential for covalent catalysis. Virology. 1995;211:73–83. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shuman S, Schwer B. RNA capping enzyme and DNA ligase: a superfamily of covalent nucleotidyl transferases. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:405–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17030405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slavicek J M. Temporal analysis and spatial mapping of Lymantria dispar nuclear polyhedrosis virus transcripts and in vitro translation products. Virus Res. 1991;20:223–236. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(91)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sobell H M. Molecular mechanism for genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:2483–2487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.9.2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Summers M D, Smith G E. A manual of methods for baculovirus vectors and insect cell culture procedures. 1987. Tex. Agric. Exp. Stn. Bull. 1555. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomkinson A E, Roberts E, Daly G, Totty N F, Lindahl T. Three distinct DNA ligases in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21728–21735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waga S, Bauer G, Stillman B. Reconstitution of complete SV40 DNA replication with purified replication factors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10923–10934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner R E, Radman M. A mechanism for initiation of genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:3619–3622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei Y, Robins P, Carter K, Caldecott K, Pappin D J C, Yu G, Wang R, Shell B K, Nash R A, Schar P, Barnes D E, Haseltine W A, Lindahl T. Molecular cloning and expression of human cDNAs encoding a novel DNA ligase IV and DNA ligase III, an enzyme active in DNA repair and recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3206–3216. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.6.3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilson T E, Grawunder U, Lieber M R. Yeast DNA ligase IV mediates non-homologous DNA end joining. Nature (London) 1997;388:495–498. doi: 10.1038/41365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]