Abstract

Objective

To assess the time to initiation of antenatal care (ANC) and its predictors among pregnant women in Ethiopia.

Design

Retrospective follow-up study using secondary data from the 2019 Ethiopian Mini-Demographic and Health Survey.

Setting and participants

2933 women aged 15–49 years who had ANC visits during their current or most recent pregnancy within the 5 years prior to the survey were included in this study. Women who attended prenatal appointments but whose gestational age was unknown at the first prenatal visit were excluded from the study.

Outcome measures

Participants were interviewed about the gestational age in months at which they made the first ANC visit. Multivariable mixed-effects survival regression was fitted to identify factors associated with the time to initiation of ANC.

Results

In this study, the estimated mean survival time of pregnant women to initiate the first ANC visit in Ethiopia was found to be 6.8 months (95% CI: 6.68, 6.95). Women whose last birth was a caesarean section (adjusted acceleration factor (AAF)=0.75; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.93) and women with higher education (AAF)=0.69; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.95) had a shorter time to initiate ANC early in the first trimester of pregnancy. However, being grand multiparous (AAF=1.31; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.63), being previously in a union (AAF=1.47; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.00), having a home birth (AAF=1.35; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.61) and living in a rural area (AAF=1.25; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.52) were the impediments to early ANC initiation.

Conclusion

Women in this study area sought their initial ANC far later than what the WHO recommended. Therefore, healthcare providers should collaborate with community health workers to provide home-based care in order to encourage prompt ANC among hard-to-reach populations, such as rural residents and those giving birth at home.

Keywords: OBSTETRICS, PUBLIC HEALTH, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS, Pregnant Women, Prenatal diagnosis

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study used a large, nationally representative sample from Ethiopian survey data.

This study evaluated community-level and individual-level factors related to the survival time to initiation of antenatal care (ANC) visit using a robust model.

Many factors that could affect the timing of the first ANC visit were not taken into account in this study because they were not present in the original data.

Social desirability bias is likely to arise because the data were collected through self-reported interviews with participants.

Introduction

A healthy pregnancy for both the mother and child, a smooth transition to a happy labour and delivery experience, and successful parenthood are all aspects of a positive pregnancy experience that women want and need.1 However, the morbidity and mortality rates associated with pregnancy that are preventable are still too high at the outset of the Sustainable Development Goals period. In order to improve a pregnancy’s outcome, antenatal care (ANC) is a crucial time for health promotion, screening and disease prevention.2 For multidisciplinary care providers, the early ANC visit is the best opportunity to intervene with health promotion activities and establish baseline knowledge of the pregnant woman’s pre-existing medical conditions.3

Early detection of modifiable risk factors and pre-existing conditions was made possible by timely prenatal care initiation, which is defined as the first antenatal contact made during the first trimester of pregnancy.4 The 2016 WHO recommendation also suggests an early start of ANC within the first 12 weeks of gestation.2 Women with early ANC initiation are more likely to have a sufficient number of ANC contacts.5 A study from low and middle-income countries (LMICs) has shown that receiving early ANC is associated with a higher likelihood of having more than eight ANC visits.6 According to a Pakistani study, women who had their first ANC check-up within 3 months of being pregnant were more likely to obtain WHO-recommended services during their pregnancy, indicating that the timing of the check-up is a strong predictor of the content of services.7

There has been a significant improvement in the estimated global coverage of early prenatal care visits, going from 40.9% in 1990 to 84.8% in 2013, or a 43.3% increase.4 The estimated coverage of early prenatal care visits in LMICs in 2013 was 24%, compared with 81% in high-income countries.4 Data from these nations’ Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 2012 to 2018 show that this percentage has climbed to 44.3%.5 Yet, this shows that the rate of early initiation of ANC in LMICs is very far from the optimal level.

A woman dies every 2 min due to pregnancy or childbirth, according to United Nations’ estimates.8 The poorest nations and those experiencing conflict continue to have the highest rates of maternal fatalities. With 3.6% of all maternal deaths worldwide in 2020, Ethiopia had the fourth-highest estimated number of maternal deaths, behind the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria and India.8 Timely ANC initiation is essential to lowering maternal morbidity and mortality in countries with high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality.9

The magnitude of timely initiation of ANC visits in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) was 38.0%, ranging from 14.5% in Mozambique to 68.6% in Liberia.10 In Ethiopia, being one of the SSA countries, the problem is even worse. The median time to ANC initiation in the country was found to be 5 months.11 The result from the 2016 Ethiopian DHS (EDHS) revealed only 20% of pregnant women in Ethiopia start their ANC during the first trimester of their pregnancy.12 Other studies in the country reported varying magnitudes of early initiation of ANC; the proportion was found to be 46.8% in Bahir Dar,13 21.71% in Southern Ethiopia,14 40.6% in Debre Markos,15 39.5% in Tselemt District of Tigray Region,16 27.5% in Axum,17 28.8% in Ilu-Ababor18 and 34% in Bench-Sheko Zone.19

Predictors of timing of first ANC follow-up from different literature were residence,10 12 20 household wealth,10 21 educational status of the women,10 11 17 media exposure,10 11 20 occupation of the women,22–24 parity,11 25 26 husband education,20 21 husband occupation,20 distance from health facilities10 26 and maternal age.10 21 27

Despite various studies on identifying risk factors for time to first ANC follow-up conducted in Ethiopia, only a few studies were found to be representative at the national level. Furthermore, almost all of the studies failed to consider community-level factors for the time to initiation of ANC in Ethiopia. Updated and nationally representative information is very crucial for policymakers and other concerned bodies to improve the level of early ANC initiation. Respecting women’s rights and providing them with early prenatal care is the first step in a lifetime of care that will improve both the mother and child’s health.3 Therefore, this study undertook a retrospective analysis based on the 2019 Ethiopian Mini-DHS (EMDHS) dataset, to identify time to initiation of ANC and its predictors in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and area

This study undertook a retrospective analysis based on the 2019 EMDHS dataset. Ethiopia is located in the Horn of Africa and shares a border with Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan and Kenya. It has a population of over 110 million people, putting it the second highest in Africa.28 The 2021 World Bank report indicated that Ethiopia had a gross national income per capita of US$940.29

Data source and sampling procedure

Data from the 2019 EMDHS were used in this study. The data were supplied once the Measure DHS website (http://www.measuredhs.com) was accessed online and the goal of the study was explained.30 The variables included in this study were found in the under-5 children’s file (KR) and individual women’s files (EMDHS 2019). Interviews with permanent residents and guests who had been in their dwellings the day before the survey were done in person with the 2019 EMDHS sample, which had been stratified and selected in two steps.30 A composite of all census enumeration areas (EAs) made for the 2019 Ethiopia Population and Housing Census (PHC), which will be conducted by the Central Statistical Agency, is the 2019 EMDHS sample frame. The whole list of 149 093 EAs prepared for the 2019 PHC is included in the census frame. A geographical area of 131 households on average is called an EA. The location of the EA, the kind of dwelling (rural or urban) and the approximate number of residential households are all included in the sampling frame.30

Study population

All women aged 15–49 years who had ANC during their current or most recent pregnancy within the 5 years prior to the survey were included in this study. Women who attended prenatal appointments but whose gestational age was unknown at the first prenatal visit were excluded from the study. A total of 2933 women aged 15–49 years who had ANC visits during their current or most recent pregnancy were therefore analysed in this study.

Study variables

Outcome of interest

The time in months that pregnant women take to receive the first ANC service is the dependent variable. The event of interest considered as success (event=1) is if women had ANC in the first trimester of pregnancy and otherwise censored (censored=0).

Independent variables

Individual-level factors included women’s education level, marital status, birth interval, number of prenatal care visits, age and exposure to the media.

Community-level factors were residence location, region, educational attainment in the community, ANC coverage in the community and poverty of the community. The only information the EMDHS gathered about the clusters’ characteristics was their region and place of residence. Consequently, by combining our interest in a cluster with the individual traits, more shared community-level data were produced. The percentage of a given variable’s subcategory that we were interested in within a specific cluster was used to calculate the aggregates. Due to the non-normal distribution of the total generated variable value, the national median values were used to group it into categories.

The aggregates were created using the percentage of a variable’s subcategory in a specific cluster. Due to the non-normal distribution of the aggregate value for all newly produced variables, it was divided into two groups (low and high proportions) according to their median values. The percentage of women in the cluster with secondary or higher education is used to gauge the level of education among women in the community. The percentage of women in the cluster’s bottom two household wealth quantiles—the poorer and the poorest—was used to define poverty at the community level. The community’s use of ANC was determined by looking at the proportion of women in a cluster who use it. Residence location and region were used according to their classifications in the EMDHS data collection.

Operational definition

Exposure to mass media was defined as the frequency of watching television and listening to the radio, excluding exposure to magazines and newspapers. Women who were exposed to radio or television at least once a week were classified as exposed, whereas those who were not exposed at all were classified as not exposed.

Community women’s education: the percentage of mothers in the cluster who completed their secondary or tertiary education. The aggregate of secondary or post-secondary education that each mother has completed can be used to determine the general level of education among the women in the cluster. This variable was split into two groups based on the national median value: a low-percentage cluster and a high-percentage cluster.

ANC utilisation was defined as mothers who had had prenatal care at least four times.2

Community antenatal coverage: the percentage of women within the clusters who had four or more prenatal visits from a qualified practitioner before their most recent delivery.

Community poverty status was defined as the percentage of the clusters’ poor or poorest mothers.

Data quality control and assurance

The datasets for the original work were collected by interviewing women face-to-face using structured questionnaires that met the eligibility criteria. The woman’s questionnaire, the household questionnaire and the Health Facility Questionnaire were employed to gather essential information. After the questionnaires were finalised in English, they were translated into Amarigna, Tigrigna and Afaan Oromo. To maintain consistency, the collected data were also back-translated into English. The quality of the dataset has been maintained by testing its completeness. Additionally, interviewers were trained to preserve the original dataset’s quality, and they recorded interviewee responses on tablet computers.

For this study, the data were weighted using sampling weight before any statistical analysis to restore the representativeness of the data and to get a reliable estimate and SE. The weighted results from the analysis were reported in the study. Multicollinearity between independent variables was checked using variance inflation factor (VIF) and the mean VIF was 2.11. The proportional hazard (PH) assumption was tested using scaled Schoenfeld residuals and found to be unsatisfied, with a global test value of 0.0001. The data were also assessed for an interaction factor.

Data management and analysis

STATA V.14 software was used for cleaning, recoding and analysing the data. Descriptive statistics were applied using frequencies and percentages. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve was used to estimate the probability of survival. Survival curves were compared by log-rank test. Univariable survival regression was fitted for explanatory variables and those having p≤0.25 level of significance were considered for the multivariable analysis. Then, the study applied a stepwise backward variable selection procedure to obtain the final reduced model. The PH assumption was tested using scaled Schoenfeld residuals and found to be unsatisfied, with a global test value of 0.0001. A multivariable mixed-effects parametric survival regression model of the Weibull distribution was then fitted. Adjusted acceleration factor (AAF) or time ratio with its 95% CI was applied, and covariates with a p value of <0.05 in the multivariable analysis were considered determinants of the survival time to first ANC visit.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis deals with the analysis of survival data, which is used to measure the time to an event of interest, such as death or failure.31 The Cox proportional hazard model is one of the most widely used regression model types in survival analysis. The Cox model estimates the HR, which is always a non-negative value. The primary attribute of the Cox model is its reliance on the PH assumption, which states that ‘coefficients of the hazard function must remain constant across time for a given covariate’.31

Parametric acceleration failure time model

An acceleration failure time (AFT) model is a parametric model in the statistical field of survival analysis that offers an alternative to the often used PH models. The primary distinction between Cox model and AFT model is that the baseline hazard function is supposed to follow a specific distribution in AFT models. Covariate multiplies the hazard by a constant in a PH model, while it accelerates or decelerates a failure status’s life cycle (initiation, discontinuation, disease, death or recovery) by a constant in an AFT model.32

The AFT model is the one used for adjusting survivor functions for the effects of covariates. The AFT parameterisation expresses the natural logarithm of the survival time, log t, as a linear function of the covariates.31

log(tj) = Xjβ + Zjuj + vj(1)

for j=1,…, M clusters with cluster j consisting of i=1,…, nj observations. The vector xji contains the covariates for the fixed effects, with regression coefficients (fixed effect) β. The vector zji contains the covariates corresponding to the random-effects uj. vji is an observation-level error with density ϕ(·). The distributional form of the error term determines the regression model. Five regression models are implemented in mestreg using the AFT parameterisation: exponential, gamma, loglogistic, lognormal and Weibull. As a result, this study applied a random-effects Weibull model with normally distributed random effects. This model can be described as a shared frailty model with lognormal frailty.

Mixed-effects parametric survival analysis

The EMDHS employed a multistage cluster sampling technique in which data were hierarchical (pregnant women were nested within families and households inside clusters).

Considering the hierarchical nature of EMDHS data, pregnant women who lived within the same cluster may have had similar characteristics compared with those who reside in other clusters of the country. Therefore, a two-stage multivariable mixed-effects parametric survival regression analysis was employed to estimate the effects of individual and community-level predictors on the survival time to first ANC visit. Mixed-effects survival models contain both fixed effects and random effects.

Four models were fitted to identify community and individual-level factors associated with survival time to first ANC visit. The first model (model 1 or the empty model) had no explanatory variables. The second model (model 2) examined the individual-level effect by focusing solely on individual-level factors. The third model (model 3) evaluated solely the community-level variables to examine the effect of community-level characteristics on the survival time to the first ANC visit, independent of other factors.

The fixed-effect sizes of individual and community-level determinants of the survival time to first ANC visit were expressed as AAFs with 95% CI. P<0.05 has been considered as statistically significant. Additionally, the measure of variance (random effects) was reported in terms of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), median acceleration factor (MAF) and proportional change in variance (PCV). Model fitness was checked using Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and Deviance Information Criteria (DIC). The lowest AIC and DIC values declare the best-fit model.31

Patient and public involvement

Women in their reproductive years who had ANC during their current or most recent pregnancy within the 5 years prior to the survey took part in this study and contributed vital data. However, they never participated in conducting the study, designing the protocol or instruments used to gather the study’s data, reporting the findings or distributing them.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Weighted samples of 2924 women were followed for a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 10 months with an average follow-up time of 4 months. In this study, timely initiation of ANC visit in Ethiopia was found to be 42.7% (95% CI: 41.0% to 44.6%). The estimated mean (restricted) survival time of pregnant women to initiate the first ANC visit was 6.8 months (95% CI: 6.68, 6.95). The overall incidence rate was approximately 11 per 100 person-months of observation. The majority (2755, 94.2%) of women were currently married or in a union, and of these, 1030 (37.4%) had initiated ANC visits early in the first trimester of pregnancy. Regarding women’s education, 1283 (43.9%) women had no education, and among these, 404 (31.5%) initiated their ANC visit timely. Access to media was reported by 1259 (43.1%), of whom 582 (46.2%) had started ANC visit within 12 weeks of pregnancy. More than half (114, 58.5%) of the women who gave birth by a caesarean section started their first ANC visit within the first trimester (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of individual and community-level factors of time to ANC initiation among study participants (2924), 2022

| Variables | Categories | Time to ANC initiation | Total N (%) |

|

| Event N (%) |

Censored N (%) |

|||

| Maternal education | Higher Secondary Primary No education |

105 (68.6) 130 (38.8) 452 (39.2) 404 (31.5) |

48 (31.4) 205 (61.2) 701 (60.8) 879 (68.5) |

153 (5.2) 335 (11.5) 1153 (39.4) 1283 (43.9) |

| Wealth index | Rich Middle Poor |

647(48) 182 (31 264 (26.7) |

701(52) 407(69) 723 (73.3) |

1348 (46.1) 589 (20.1) 987 (33.8) |

| Household size (members) | 1–5 6 or more |

692 (43.3) 401 (30.3) |

907 (56.7) 924 (69.7) |

1599 (54.7) 1325 (45.3) |

| Maternal age | <20 years 20–34 years ≥35 years |

48 (31.4) 846 (39.2) 199 (32.4) |

105 (68.6) 1310 (60.8) 416 (67.6) |

153 (5.2) 2156 (73.8) 615 (21) |

| Household head | Female Male |

156 (40.4) 937 (36.9) |

230 (59.6) 1601 (63.1) |

386 (13.2) 2538 (86.8) |

| Place of delivery | Facility Home |

801 (42.4) 292 (28.2) |

1088 (57.6) 743 (71.8) |

1889 (64.6) 1035 (35.4) |

| PNC | No Yes |

881 (36.5) 212 (41.5) |

1532 (63.5) 299 (58.5) |

2413 (82.5) 511 (17.5) |

| Last birth C/S | No Yes |

804 (34.9) 114 (58.5) |

1502 (65.1) 81 (41.5) |

2306 (92.2) 195 (7.8) |

| Birth interval (2220) | ≥36 months <36 months |

478 (37.6) 305 (32.1) |

792 (62.4) 645 (67.9) |

1270 (57.2) 950 (42.8) |

| Ever had a child loss | No Yes |

939 (39.7) 154 (27.7) |

1429 (60.3) 402 (72.3) |

2368(81) 556 (9) |

| Parity | Primipara Multipara Grand multipara |

299 (43.4) 559 (40.8) 235 (27.2) |

390 (56.6) 811 (59.2) 630 (72.8) |

689 (23.6) 1370 (46.8) 865 (29.6) |

| Residence | Urban Rural |

445(51) 647 (31.5) |

427(49) 1405 (68.5) |

872 (29.8) 2052 (70.2) |

| Community ANC utilisation | High Low |

718 (43.3) 375 (29.6) |

937 (56.6) 894 (70.4) |

1655 (56.6) 1269 (43.4) |

| Community women’s education | High Low |

696 (39.7) 397 (33.9) |

1056 (60.3) 775 (66.1) |

1752 (59.9) 1172 (40.1) |

| Community-level poverty | Low High |

740 (46.9) 353 (26.2) |

837 (53.1) 994 (73.8) |

1577 (53.9) 1347 (46.1) |

ANC, antenatal care; C/S, caesarean section; PNC, postnatal care.

Most (2052, 70.2%) of the women were rural residents, and among these, only 647 (31.5%) initiated ANC visit within the recommended time. The proportion of women starting their first ANC visit within the first trimester was higher in Harari (66.7%), Dire Dawa (66.7%) and Addis Ababa (65%), whereas lower in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) (28.8%), Oromia (33.2%) and Somali (33.3%) regional states. More than half (1577, 53.9) of the women were from a community with a low proportion of poor residents, of whom 740 (46.9%) commenced their first ANC visit in the first 3 months of pregnancy. Moreover, 353 (26.2%) women from a community with a high proportion of poor residents commenced their first ANC visit timely (table 1).

Comparison of the different covariates in terms of survival time to first ANC visit

Kaplan-Meier graphs are generated to observe the difference in the survival time to first ANC visits of women for different categorical variables. The log-rank test was carried out to validate the difference between the groups of each categorical variable. The log-rank test result (table 2) shows that there is statistically significant difference in the survival experience of groups among women’s education level (p<0.0001), wealth index (p<0.0001), delivery place (p<0.0001), parity (p<0.0001), media access (p<0.0001), region (p<0.0001), women’s age (p<0.001) and marital status (p<0.2) (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of survival time of individual and community-level factors of time to ANC initiation among study participants (2924), 2022

| Variables | Categories | Time to ANC initiation | Log-rank test | P value | |

| Event observed | Event expected | ||||

| Mother’s education | No education Primary Secondary Higher |

404 452 131 105 |

488 431 126 47 |

114.88 | 0.0001 |

| Household size | <6 members ≥6 members |

692 400 |

585 507 |

54.22 | 0.0001 |

| Ever had a child loss | No Yes |

938 154 |

876 216 |

28.21 | 0.0001 |

| Women’s age | <20 years 20–34 years ≥35 years |

49 845 198 |

57 802 233 |

11.48 | 0.0032 |

| Birth interval | ≥36 months <36 months |

477 305 |

442 340 |

8.49 | 0.0036 |

| PNC | No Yes |

881 211 |

909 183 |

6.82 | 0.0090 |

| Marital status | Currently in union Formerly in union Never in union |

1030 54 8 |

1029 59 4 |

4.53 | 0.1039 |

| Household head | Female Male |

156 936 |

140 952 |

2.68 | 0.1018 |

| Community-level poverty | Low High |

739 353 |

569 523 |

136.88 | 0.0001 |

| Residence | Urban Rural |

445 647 |

310 782 |

105.30 | 0.0001 |

| Community ANC utilisation | High Low |

717 375 |

606 486 |

58.21 | 0.0001 |

| Community women’s education | High Low |

695 397 |

645 447 |

12.27 | 0.0005 |

ANC, antenatal care; PNC, postnatal care.

Random effects and model comparison

As the multilevel mixed-effects Weibull survival regression analysis results described in table 3, model 1 revealed statistically significant variation in the survival time to first ANC visit of women across communities. Nearly one-fifth of the variation in the survival time is attributed to community-level factors (ICC=18.9%). After adjusting the model for individual-level factors (model 2), about 32.4% of the variation in the acceleration of survival time was attributed to the individual-level factors (PCV=32.4%), and 13.6% of the variance in the survival time was attributed to community-level factors (ICC=13.6%). Model 3, which was adjusted for community-level factors, revealed that the community-level factors explained 4.12% of the variability in the acceleration of survival time to the first ANC visit of women (PCV=4.12%), and 13.1% of the variation among the clusters was attributed to community-level factors (ICC=13.1%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Measures of variation and model fit statistics for time to first ANC visit among women in Ethiopia, 2023

| Null model | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Random-effect result | ||||

| Variance | 0.7686926 | 0.519486 | 0.4981052 | 0.4178334 |

| ICC (%) | 18.9 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 11.3 |

| PCV (%) | Reference | 32.4 | 4.12 | 16.1 |

| MAF | 2.31 | 1.99 | 1.96 | 1.85 |

| Model fit statistics | ||||

| Log likelihood | −2343.361 | −2086.979 | −2281.065 | −2010.789 |

| AIC | 4692.722 | 4203.958 | 4594.130 | 4075.578 |

| DIC | 4686.722 | 4173.958 | 4562.130 | 4021.578 |

AIC, Akaike Information Criteria; ANC, antenatal care; DIC, Deviance Information Criteria; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; MAF, median acceleration factor; PCV, proportional change in variance.

The final best-fit model (model 4) was adjusted for both individual and community-level factors simultaneously. In this final model (model 4), as indicated by the PCV, 16.1% of the variation in the survival time across communities was explained by both individual and community-level factors. Including both individual-level and community-level factors reduced the unexplained heterogeneity in the time to first ANC visit between communities from MAF of 2.31 in the null model to the MAF of 1.85 in the final model, which was equal to 0.46. This showed that the survival time to the first ANC visit reduced by 54% when a woman moved from high-risk to low-risk neighbourhoods (table 3).

Based on the AIC and DIC, multilevel mixed-effects Weibull survival model (model 4) was found to be the best model to fit the data with a minimum AIC and DIC values of 4075.578 and 4021.578, respectively (online supplemental table 1).

bmjopen-2023-075965supp001.pdf (84.1KB, pdf)

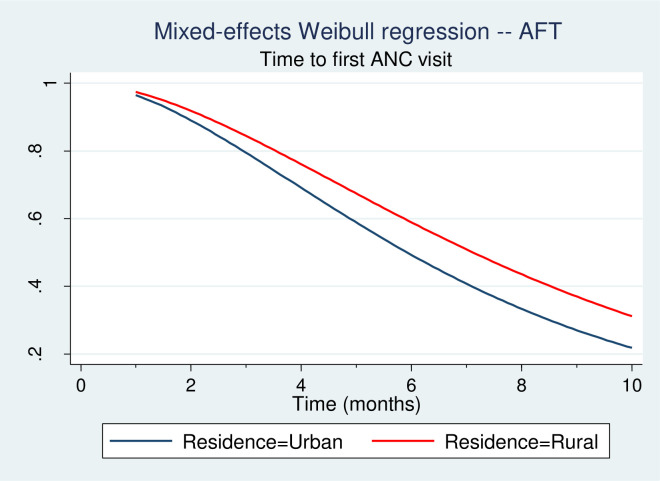

The survival plot in figure 1 shows that the survivor function for rural women is above the survivor function for urban women. This implies that rural women have a greater probability of not initiating an ANC visit at earlier gestational age.

Figure 1.

Mixed-effects AFT Weibull regression of time to first ANC visit by place of residence. AFT, acceleration failure time; ANC, antenatal care.

Interpretation of the multilevel Weibull model results

The results of the multivariable multilevel parametric Weibull survival analysis of predictors of the survival time to first ANC visit are provided in table 4. The place of delivery was found to have a significant effect on the time to ANC initiation. Mothers who delivered at home have a 35% (AAF=1.35; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.61) longer survival time to start their first ANC visit. In other words, mothers who delivered at home were less likely to initiate their first ANC visit within the first trimester of pregnancy compared with women who gave birth at a health facility. Similarly, grand multiparous women have a 31% longer time to start ANC early in the first trimester than primiparous women. The acceleration factor for grand multiparous women was 1.31 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.63).

Table 4.

Mixed-effects Weibull AFT survival regression of time to first ANC visit among women in Ethiopia, 2023

| Variables | Categories | Null model | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

| Place of last birth | Facility | 1 | 1 | ||

| Home | 1.11 (0.98, 1.25) | 1.35 (1.13, 1.61)** | |||

| Parity | Primipara | 1 | 1 | ||

| Multipara | 1.09 (0.96, 1.25) | 1.07 (0.89, 1.28) | |||

| Grand multipara | 1.19 (1.03, 1.40)* | 1.31 (1.04, 1.63)* | |||

| Media access | No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.83 (0.73, 0.94)** | 0.90 (0.76, 1.06) | |||

| Last birth | Vaginal | 1 | 1 | ||

| C/S | 0.86 (0.75, 0.98)* | 0.75 (0.61, 0.93)** | |||

| Educational level | No formal education | 1 | 1 | ||

| Primary | 0.97 (0.87, 1.09) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03) | |||

| Secondary | 1.16 (1.01, 1.34)* | 0.99 (0.75, 1.33) | |||

| Higher | 0.84 (0.70, 0.99)* | 0.69 (0.50, 0.95)* | |||

| Marital status | Currently in union | 1 | 1 | ||

| Formerly in union | 1.12 (0.88, 1.44) | 1.47 (1.07, 2.00)* | |||

| Never in union | 0.64 (0.37, 1.09) | 1.12 (0.37, 3.40) | |||

| PNC | No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.87 (0.75, 1.00) | 0.83 (0.67, 1.02) | |||

| Community ANC | Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) | 0.90 (0.77, 1.05) | |||

| Community education | Low | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 0.95 (0.85, 1.06) | 1.15 (0.99, 1.34) | |||

| Residency | Urban | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 1.15 (1.01, 1.32)* | 1.25 (1.03, 1.52)* | |||

| Region | Addis Ababa | 1 | 1 | ||

| Tigray | 1.20 (0.96, 1.48) | 1.04 (0.80, 1.35) | |||

| Afar | 1.07 (0.85, 1.34) | 0.93 (0.69, 1.24) | |||

| Amhara | 1.03 (0.81, 1.31) | 0.95 (0.72, 1.26) 1.08 (0.81, 1.43) |

|||

| Oromia | 1.37 (1.12, 1.68)** | ||||

| Somalia | 1.03 (0.68, 1.57) | 1.17 (0.81, 1.70) | |||

| Benishangul | 1.21 (0.97, 1.52) | 1.19 (0.89, 1.60) | |||

| SNNPR | 1.50 (1.23, 1.84)*** | 1.46 (1.02, 2.10)* | |||

| Gambella | 1.39 (1.11, 1.73)** | 1.23 (0.92, 1.65) | |||

| Harari | 0.97 (0.79, 1.21) | 0.80 (0.65, 0.99)* | |||

| Dire Dawa | 0.93 (0.76, 1.15) | 0.82 (0.65, 1.05) |

*P<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

1=reference category.

AFT, acceleration failure time; ANC, antenatal care; C/S, caesarean section; PNC, postnatal care; SNNPR, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region.

Women with higher education had a 31% shorter time to start their first ANC visit than those who were not educated (AAF=0.69; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.95). This indicates that women with higher education are more likely to initiate their first ANC visit in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy than women with no formal education. Similarly, women whose last birth was a caesarean section had a 25% shorter time to initiate ANC early in the first trimester as compared with those who delivered vaginally (AAF=0.75; 95% CI: 0.61, 0.93) (table 4).

Women who were formerly married or in a union took 1.47 times longer (AAF=1.47; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.00) to schedule their first ANC visit early in pregnancy. It can be stated that women who had previously been in unions were less likely to begin their ANC visit early in the first 3 months of pregnancy than women who were currently in unions (table 4).

The survival time until the first ANC visit was found to be significantly influenced by one’s place of residence. Compared with women from urban residences, those from rural ones took 1.25 times longer to begin their first ANC visit early in pregnancy (AAF=1.25; 95% CI: 1.03, 1.52). In other words, compared with women who lived in urban areas, women who live in rural areas had a lower likelihood of scheduling their first ANC visit during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. Administrative region was also a significant predictor of time to first ANC visit (table 4).

Discussion

In this study, Ethiopian pregnant women’s time to initiation of ANC and its predictors were evaluated. Pregnant women’s mean survival time to schedule their first ANC check-up was thus 6.8 months (95% CI: 6.68, 6.95). Furthermore, the time to initiation of ANC was significantly associated with factors such as women’s educational attainment, prior caesarean birth, parity, marital status, place of delivery, place of residency and region of residency.

The mean survival time of pregnant women to initiate ANC visits in this study was significantly higher than a study done in India in which the reported median survival time to the first ANC visit was 4 months.33 The finding of this study is also slightly higher than the study finding from Nigeria in which the median survival time for the first ANC check-up was found to be 6 months.34 Moreover, this finding is higher when compared with the recent findings of average of 3.4 gestational months before initiation of ANC visits in Ghana.27 However, late initiation of ANC visits has been previously reported in Ethiopia with a median survival time of 7 months.35

Timely initiation of ANC visits within the first 3 months of pregnancy in Ethiopia was found to be 42.7% (95% CI: 41.0%, 44.6%). This finding is lower than the study conducted in Pakistan which indicated that nearly half of women (48%) received ANC within 3 months of pregnancy.7 This finding is significantly higher than studies done in Tanzania,36 Benin,37 Kenya38 and Nigeria,34 but lower compared with a study from Ghana, where first trimester initiation of ANC visits was reported to be as high as 57%.27 This result is higher than the previous study conducted in Ethiopia that reported timely initiation of ANC visits of 38.6%.35

Women who had higher education had a 31% shortened time to start first ANC visit than those with no formal education. This finding is in agreement with findings of previous studies.11 33 39 A study conducted in India revealed that women with higher education had a 2.8 times shorter time to initiate ANC in the first trimester of pregnancy compared with women having no formal education.33 Similarly, in Nepal, women with higher-level education were significantly more likely to initiate ANC early compared with women who had no education.39 A multicountry analysis of DHS in SSA found that the odds of timely initiation of ANC were higher in mothers who had a higher level of education compared with women who had no formal education.10 A study from Nigeria revealed that women with higher education were more likely to start their first ANC visit early compared with uneducated women.34 A retrospective study from Ethiopia revealed that early initiation of ANC increases as the women’s level of education increases.11

The possible explanation could be women with a higher level of education might be more likely to be employed, financially independent and knowledgeable of the necessity of having ANC follow-up during pregnancy; as a result, they might be more likely to realise the importance of booking their first ANC visit early and timely.40 Additionally, uneducated women might have an limited understanding of ANC services and their importance to their unborn fetus’s well-being and ensure safe delivery.11 It is because education will change the knowledge of when to start ANC awareness of the mothers to start and follow the health services appropriately.18

This study indicated that women who were formerly in a union commenced ANC visits later than mothers who were currently in a union at a 5% level of significance. The findings of this study indicate that having the father of the child present in the woman’s life during pregnancy shortens the time to first ANC attendance and highlights the need to involve male partners in reproductive health issues including maternal healthcare and family planning. This evidence is in line with the studies done in South Africa24 and Rwanda26 in which currently married women were more likely to initiate ANC in the first trimester of pregnancy. This might be due to the fear of social rumours, and hence, lack of confidence in seeking care for unborn child whose father is not formally introduced or in doubt. Another possible explanation can be the workload hanging on the woman’s shoulder only to improve the life of her unborn child as well as herself. Furthermore, women might not know whether they are pregnant, and even if they knew it early, they may not be interested in the pregnancy, so they may be careless with the conception and fail to book an ANC visit early. Women with an unwanted24 and mistimed pregnancies41 have been shown to receive late ANC.

Grand multiparous women had a 31% longer time to start ANC early in the first trimester than primiparous women. This evidence is supported by prior studies.11 33 41 42 A study finding from India has shown that women with a birth order of four and above had a 16% prolonged time to initiate ANC compared with primiparous women.33 In Malawi, women with more than five births were 12% less likely to access ANC services in their first trimester of pregnancy.42 In Nigeria, women with one birth were more likely to initiate ANC in the first trimester compared with women with five and more births.21 In Kenya, women with four and more births were 1.75 times more likely to start their first ANC during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy compared with the primiparous women.41

A survival study from Ethiopia found that women with four and more births had a 20% hazard of delayed initiation of ANC follow-up as compared with those with one parity.11 Another population study from Ethiopia showed that multiparous women had higher odds of delayed initiation of ANC visits when compared with the primiparous women.23 This might be attributable to multiparous women’s increased confidence from previous pregnancies and childbirth experience. Additionally, multiparous women might have poor prior experience with the health system, and constraints of time and resources to access ANC services early.38

This study also showed that women from a rural residency had a prolonged time to start their first ANC visit relative to those who were from an urban residency. In India, urban residents had a 49% probability of initiating ANC early in the first trimester of pregnancy compared with their rural counterparts.33 In SSA, women residing in the rural area were less likely to initiate ANC timely within 12 weeks of gestation.10 In Nigeria, women in urban areas were more likely to make the first ANC visit early in the first trimester of pregnancy.34 A study from Kenya showed that the odds of timely initiation of ANC in the first 3 months of pregnancy were higher in women living in urban areas compared with their rural counterparts.41

A study in Ethiopia using the 2016 EDHS dataset indicated that rural women have prolonged time to start their first ANC visit than urban women.20 In Ethiopia, women from rural residency were 18% less likely to attain ANC early in pregnancy than their urban counterparts.11 Another similar study in Ethiopia showed that rural women were 59% less likely to start their first ANC visit within the first trimester than their urban counterparts.12 This might be because urban women have easier access to transportation and social media, which help them easily obtain information about the significance, timeliness and services offered by healthcare facilities.

Place of delivery was found to be a significant predictor of the survival time to the first ANC visit. Women whose last birth was in their home had a 35% longer survival time to start their first ANC visit compared with those whose last birth was in a health facility. This result is supported by the finding reported from Western Ethiopia in which women whose previous childbirth was institutional delivery were five times more likely to initiate ANC early when compared with women who had a home delivery.43 A study from Mandera County in Kenya reported that women who used skilled delivery services were more likely to have used ANC services more than those who had not used the service.38 A possible explanation might be that mothers who gave birth at health institutions might receive advice and relevant information regarding the importance of early antenatal booking for themselves and their fetuses, which might positively influence women’s attitudes towards early ANC visits.

This study showed that women whose last birth was a caesarean section had a 25% shorter time to start first ANC than those who gave their last birth vaginally. This finding is supported by previous similar studies.36 38 44 A study done in Uganda showed that women who gave birth by a caesarean section were more likely to initiate their first ANC visit in the first trimester of pregnancy.44 According to a study from Tanzania, women with previous or current pregnancy-related complications were more likely to book an ANC visit earlier than others.36 In Kenya, women who had complications during their last pregnancy were two times more likely to receive ANC than those who had no complication.38 This might be due to the fact that women who had complications in their previous pregnancy might have worries about themselves and their fetus’s health which compels them to better use ANC services.

In relation to the country’s administrative region, women from SNNPR had a 46% longer time to start the first ANC compared with women from Addis Ababa. One possible explanation for this could be the variations in the accessibility of medical facilities. The population in the SNNPR is more dispersed, making the accessibility of health facilities difficult, and women from those areas might be less informed about the benefits of ANC. Additionally, women from Harari were found to have a shorter time to commence ANC.

Study limitations and strengths

This study used secondary data that were collected cross-sectionally through self-reported interviews, which are prone to recall errors and social desirability bias. Furthermore, some factors that are probably crucial in determining the timing of the first ANC visit, such as the standard of ANC provided and women’s perceptions of the ANC, were not available for consideration in the existing EMDHS data.

Despite these drawbacks, the current study used a large sample from nationally representative survey data in Ethiopia. The results of the study were representative of all regions. The study also attempted to analyse community-level variables related to the survival time to initiation of ANC visits. Another advantage of the study is its sophisticated statistical design, which allows for greater reliability of the results and allows for the control of confounding factors.

Conclusion

The study indicated that women in the study area sought their initial ANC at a health facility far later than what the WHO recommended. Early ANC initiation in the first trimester of pregnancy was positively associated with independent variables, such as women’s educational attainment, media exposure and history of caesarean delivery. Higher parity, home births, rural settlement, and previously formed but unsuccessful unions had a negative effect on the initiation of ANC services during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Therefore, it is crucial to provide health education with a focus on empowering expectant mothers to timely activate prenatal care, especially for those who give birth at home and for those who reside in remote areas. Healthcare providers should collaborate with community health workers to provide home-based care in order to encourage prompt ANC among hard-to-reach populations, such as rural residents and those giving birth at home. This study also has the implication that policies aiming to decrease pregnancy-related preventable morbidity and mortality through the use of timely ANC must prioritise educating and empowering women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the MEASURE DHS Project for their free access to the original data of the 2019 Mini Demographic and Health Survey of Ethiopia.

Footnotes

@Chigir6

Contributors: BTO and HZA conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, initiated the research, carried out the statistical analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the final manuscript, critically reviewing it. MA and DGT participated in the study’s design, guided the statistical analysis and critically reviewed the manuscript. HIG and TGT were involved in principal supervision, participated in the study’s design and coordination, edited the manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript. BTO bears primary responsibility for the final content, acts as a guarantor to access the data, and makes the final decision to publish. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Ethics review and participant consent were not required for this study because it used secondary data analysis of publicly available survey data from the Measure DHS programme. A written letter of permission was secured from the IRB of Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) programme data archivists to download and use the data for this study from https://www.dhsprogram.com. This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The DHS data were kept confidential, and any identifying information was removed. The data were only used for this particular, authorised research project, and they would not be shared with any researchers.

References

- 1. Tolossa T, Turi E, Fetensa G, et al. Association between pregnancy intention and late initiation of Antenatal care among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 2020;9:191. 10.1186/s13643-020-01449-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on Antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raynes-Greenow C. Gaps and challenges underpinning the first analysis of global coverage of early Antenatal care. The Lancet Global Health 2017;5:e949–50. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30346-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moller AB, Petzold M, Chou D, et al. Early Antenatal care visit: a systematic analysis of regional and global levels and trends of coverage from 1990 to 2013. The Lancet Global Health 2017;5:e977–83. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30325-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jiwani SS, Amouzou-Aguirre A, Carvajal L, et al. Timing and number of Antenatal care contacts in low-and middle-income countries: analysis in the Countdown to 2030 priority countries. J Glob Health 2020;10:010502. 10.7189/jogh.10.010502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Apanga PA, Kumbeni MT. Association between early Antenatal care and Antenatal care contacts across low-and middle-income countries: effect modification by place of residence. Epidemiol Health 2021;43:e2021092. 10.4178/epih.e2021092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agha S, Tappis H. The timing of Antenatal care initiation and the content of care in Sindh, Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:190. 10.1186/s12884-016-0979-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO . UNICEF UNFPA, WORLD BANK GROUP and UNDESA/population division. In: Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2020: estimates. Geneva: WHO, 2023. Available: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal-mortality-2000-2017/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 9. Makate M, Makate C. Journal of epidemiology and global health prenatal care utilization in Zimbabwe: examining the role of community-level factors. JEGH 2017;7:255. 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alem AZ, Yeshaw Y, Liyew AM, et al. Timely initiation of Antenatal care and its associated factors among pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa: A Multicountry analysis of demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE 2022;17:e0262411. 10.1371/journal.pone.0262411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dewau R, Muche A, Fentaw Z, et al. Time to initiation of Antenatal care and its predictors among pregnant women in Ethiopia: Cox-gamma shared frailty model. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0246349. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woldeamanuel BT, Belachew TA. Timing of first Antenatal care visits and number of items of Antenatal care contents received and associated factors in Ethiopia: Multilevel mixed effects analysis. Reprod Health 2021;18:233. 10.1186/s12978-021-01275-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alemu Y, Aragaw A. Early Initiations of first Antenatal care visit and associated factor among mothers who gave birth in the last six months preceding birth in Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda North West Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2018;15:203. 10.1186/s12978-018-0646-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geta MB, Yallew WW. Early initiation of Antenatal care and factors associated with early Antenatal care initiation at health facilities in Southern Ethiopia. Advances in Public Health 2017;2017:1–6. 10.1155/2017/1624245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolde F, Mulaw Z, Zena T, et al. Determinants of late initiation for Antenatal care follow up: the case of northern Ethiopian pregnant women. BMC Res Notes 2018;11:1–7. 10.1186/s13104-018-3938-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weldemariam S, Damte A, Endris K, et al. Late Antenatal care initiation: the case of public health centers in Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2018;11:1–6. 10.1186/s13104-018-3653-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gebresilassie B, Belete T, Tilahun W, et al. Timing of first Antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women in public health institutions of Axum town. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:1–11. 10.1186/s12884-019-2490-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tola W, Negash E, Sileshi T, et al. Late initiation of Antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending Antenatal clinic of Ilu Ababor zone, Southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0246230. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tesfaye M, Dessie Y, Demena M, et al. Late Antenatal care initiation and its contributors among pregnant women at selected public health institutions in Southwest Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 2021;39:264. 10.11604/pamj.2021.39.264.22909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fentaw KD, Fenta SM, Biresaw HB, et al. Time to first Antenatal care visit among pregnant women in Ethiopia: secondary analysis of EDHS 2016; application of AFT shared frailty models. Arch Public Health 2021;79:1–14. 10.1186/s13690-021-00720-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fagbamigbe AF, Olaseinde O, Fagbamigbe OS. Timing of first Antenatal care contact, its associated factors and state-level analysis in Nigeria: a cross-sectional assessment of compliance with the WHO guidelines. BMJ Open 2021;11:e047835. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agaba P, Magadi M, Onukwugha F, et al. Factors associated with the timing and number of Antenatal care visits among unmarried compared to married youth in Uganda between 2006 and 2016. Social Sciences 2021;10:474. 10.3390/socsci10120474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Ekholuenetale M, et al. Timing and adequate attendance of Antenatal care visits among women in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184934. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muhwava LS, Morojele N, London L. Psychosocial factors associated with early initiation and frequency of Antenatal care (ANC) visits in a rural and urban setting in South Africa: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:1–9. 10.1186/s12884-016-0807-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gross K, Alba S, Glass TR, et al. Timing of Antenatal care for adolescent and adult pregnant women in South-Eastern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:16. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Manzi A, Munyaneza F, Mujawase F, et al. Assessing predictors of delayed Antenatal care visits in Rwanda: a secondary analysis of Rwanda demographic and health survey 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:290. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Manyeh AK, Amu A, Williams J, et al. Factors associated with the timing of Antenatal clinic attendance among first-time mothers in rural Southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:47. 10.1186/s12884-020-2738-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. United Nations Department of economic and social affairs PD. world population prospects 2022: summary of results [Internet]. United Nation 2022;1–54. Available: www.un.org/development/ desa/pd/ [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Bank . Ethiopia-GNI-per-capita. n.d. Available: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/ETH/ethiopia/gni-per-capita

- 30. Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) . Ethiopia and ICF. Ethiopia mini demographic and health survey 2019: key indicators. EPHI and ICF; 2019. Available: http://www.ephi.gov.et [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival analysis. In: Survival analysis: A self-learning text. New York, NY: Springer, 2012: 292–318. Available: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-4419-6646-9 [Google Scholar]

- 32. StataCorp . Stata survival analysis reference manual release 17. A Stata Press Publication. College Station; 2021. Available: https://www.stata.com/bookstore/survival-analysis-reference-manual/ [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tripathy A, Mishra PS. Inequality in time to first Antenatal care visits and its predictors among pregnant women in India: an evidence from National family health survey. Sci Rep 2023;13:4706. 10.1038/s41598-023-31902-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fagbamigbe AF, Abel C, Mashabe B, et al. Survival analysis and Prognostic factors of the timing of first Antenatal care visit in Nigeria. Advances in Integrative Medicine 2019;6:110–9. 10.1016/j.aimed.2018.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seid A, Ahmed M. Survival time to first Antenatal care visit and its predictors among women in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2021;16:e0251322. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kisaka L, Leshabari S. Factors associated with first Antenatal care booking among pregnant women at a reproductive health clinic in Tanzania: A cross sectional study. EC Gynaecol 2020;9:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Edgard-Marius O, Charles SJ, Jacques S, et al. Determinants of low Antenatal care services utilization during the first trimester of pregnancy in Southern Benin rural setting. Ujph 2015;3:220–8. 10.13189/ujph.2015.030507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Adow I, Mwanzo I, Agina O, et al. Uptake of Antenatal care services among women of reproductive age in Mandera County, Kenya. Afr J Health Sci 2020;33:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Paudel YR, Jha T, Mehata S. Timing of first Antenatal care (ANC and inequalities in early initiation of ANC in Nepal). Front Public Health 2017;5:242. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tesfu AA, Aweke AM, Gela GB, et al. Factors associated with timely initiation of Antenatal care among pregnant women in Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia: sectional study. Nurs Open 2022;9:1210–7. 10.1002/nop2.1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ochako R, Gichuhi W. Pregnancy Wantedness, frequency and timing of Antenatal care visit among women of childbearing age in Kenya. Reprod Health 2016;13:51. 10.1186/s12978-016-0168-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kuuire VZ, Kangmennaang J, Atuoye KN, et al. Timing and utilisation of Antenatal care service in Nigeria and Malawi. Glob Public Health 2017;12:711–27. 10.1080/17441692.2017.1316413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gelassa FR, Tafasa SM, Kumera D. Determinants of early Antenatal care booking among pregnant mothers attending Antenatal care at public health facilities in the Nole Kaba district, Western Ethiopia: unmatched case-control study. BMJ Open 2023;13:e073228. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bbaale E. Factors influencing timing and frequency of Antenatal care in Uganda. Australas Med J 2011;4:431–8. 10.4066/AMJ.2011.729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-075965supp001.pdf (84.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.